Abstract

Mitochondria are ancient organelles that have co-evolved with their cellular hosts, developing a mutually beneficial arrangement. In addition to making energy, mitochondria are multifaceted, being involved in heat production, calcium storage, apoptosis, cell signaling, biosynthesis, and aging. Many of these mitochondrial functions decline with age, and are the basis for many diseases of aging. Despite the vast amount of research dedicated to this subject, the relationship between aging mitochondria and immune function is largely absent from the literature. In this review, three main issues facing the aging immune system are discussed: (1) inflamm-aging; (2) susceptibility to infection and (3) declining T-cell function. These issues are re-evaluated using the lens of mitochondrial dysfunction with aging. With the recent expansion of numerous profiling technologies, there has been a resurgence of interest in the role of metabolism in immunity, with mitochondria taking center stage. Building upon this recent accumulation of knowledge in immunometabolism, this review will advance the hypothesis that the decline in immunity and associated pathologies are partially related to the natural progression of mitochondrial dysfunction with aging.

1. Introduction

The ancestry of the mitochondrion originated ~2.5 billion years ago within the bacterial phylum α-Proteobacteria, during the rise of eukaryotes []. The endosymbiotic theory, advanced with microbial evidence by Dr. Lynn Margulis in the 1960s, proposed that one prokaryote engulfed another resulting in a quid pro quo arrangement and survival advantage []. The ability of mitochondria to convert organic molecules from the environment to energy led to the persistence of this pact.

Since most cells contain mitochondria, the clinical effects of mitochondrial dysfunction are potentially multisystemic, and involve organs with large energy requirements []. In addition to making energy, the basis of life, mitochondria are also involved in heat production, calcium storage, apoptosis, cell signaling, biosynthesis, and aging—all important for cell survival and function [,,,]. A decline in mitochondrial function and oxidant production has been connected to normal aging and with the development of a variety of diseases of aging. These topics are explored more thoroughly in other articles in this special edition. While the human immune system undergoes dramatic changes during aging, eventually progressing to immunosenescence [], the role of mitochondrial dysfunction in this process remains largely absent in the literature. Consequently, the purpose of this review is to highlight three important issues in the aging immune system: (1) inflammation with aging; (2) susceptibility to viral infections; (3) impaired T-cell immunity. These clinical phenotypes will be related to our current knowledge on the role of the mitochondria in immune function. As the associations discussed are largely speculative, it is hoped that this review will serve as a stimulus for further investigation into these issues.

2. Is There a Mitochondrial Etiology for “Inflamm-Aging”?

The term “inflamm-aging” (IA) refers to a low-grade, chronic inflammatory state that can be found in the elderly []. IA increases morbidity and mortality in older adults, and nearly all diseases of aging share an inflammatory pathogenesis including Alzheimer’s disease, atherosclerosis, heart disease, type II diabetes, and cancer []. Nevertheless, the precise etiology of IA and its causal role in contributing to adverse health outcomes remain largely unknown.

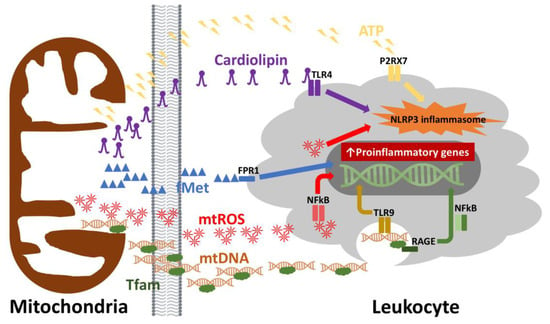

The ability of the innate system to respond to a wide variety of pathogens lies in germline-encoded receptors, whose recognition is based on repetitive molecular signatures. These pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) are present on the cell surface and intracellular compartments. Toll-like receptors (TLRs), retinoic acid-inducible gene I-like receptors (RLRs), nucleotide oligomerization domain-like receptors (NLRs) and cytosolic DNA sensors (cGAS and STING) are prime examples []. Ligands for these receptor systems comprise pathogen associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and damage associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) []. PAMPs are derived from components of microorganisms and are recognized by innate immune cells bearing PRRs. In contrast to PAMPs, DAMPs are endogenous “danger signals” that are released by cells during stress, apoptosis or necrosis. DAMPs can arise from a variety of components normally sequestered to the mitochondria, when upon release, induce inflammation via recognition by the same PRRs that recognize PAMPs [,]. Events downstream of PRR engagement include caspase-1 activation with the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines []. Examples of mitochondrial DAMPs (mtDAMPs) include cardiolipin, n-formyl peptides (e.g., fMet), mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM), adenosine triphosphate (ATP), reactive oxygen species (mtROS), and mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) (Figure 1). From an evolutionary standpoint, select mitochondrial products produce inflammation due to their prokaryotic origins: e.g., cardiolipin (TLR), fMet (formyl peptide receptor 1, FPR1), and mtDNA (TLR, NLR, cGAS) [,,,,,,,]. However, mtDAMPs are not just limited to bacterial mimics. TFAM, a nuclear gene and key regulator of mtDNA transcription and replication, activates immune cells via receptors for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) and TLR9 [,]. Products of oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) can also stimulate innate immune cells. Released from apoptotic or necrotic cells, ATP binds to purigenic receptors initiating inflammation [], while mtROS modifies core immune signaling pathways involving hypoxia inducible factor 1 alpha (HIF1α) and nuclear factor kappa light chain enhancer of activated B-cells (NFkB) [,].

Figure 1.

Mitochondrial damage associated molecular patterns (DAMPs). DAMPs derived from mitochondrial components may be released during cellular injury, apoptosis or necrosis. Once these mitochondrial components are released into the extracellular space, they can lead to the activation of innate and adaptive immune cells. The recognition of mitochondrial DAMPs involves toll-like receptors (TLR), formyl peptide receptors (FPR) and purigenic receptors (P2RX7). By binding their cognate ligands or by direct interaction (i.e., reactive oxygen species, ROS), intracellular signaling pathways such as NFkB and the NLRP3 inflammasome become activated resulting in a proinflammatory response. TLR4 = toll-like receptor 4, TLR9 = toll-like receptor 9, P2RX7 = purigenic receptor, FPR1 = formyl peptide receptor 1, NLRP3 = NLR Family Pyrin Domain Containing 3, fMet = N-formylmethionine, mtROS = mitochondrial reactive oxygen species, mtDNA = mitochondrial DNA, Tfam = transcription factor A, mitochondrial, RAGE = receptors for advanced glycation end-products, NFkB = nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells.

mtDAMPs contribute to a host of inflammatory diseases, including sepsis, systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), ischemic reperfusion injury, and aging []. One of the consequences of failing mitochondria due to aging, beyond mtROS, is the release of mtDNA. Plasma levels of mtDNA increase gradually after the fifth decade of life, correlating with elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines (i.e., TNF-α, IL-6, RANTES, and IL-1ra) []. These data indicate that mtDNA may promote the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines in aging. Because cell stress, senescence and death are a part of the pathophysiology of aging [], designing new therapeutic strategies against circulating mtDNA, or other mtDAMPs, or their cognate receptors (e.g., TLRs or FPR1) may be a viable strategy to approaching IA and its associated conditions.

3. Is Increased Susceptibility to Viral Infections Related to Depressed Mitochondrial Anti-Viral Signaling Pathways?

In general, older adults are more susceptible to a variety of viral infections, especially respiratory viral infections, resulting in high morbidity and mortality. For example, adults over the age of 65 exhibit a vulnerability to influenza A virus (IAV), and account for ≥90% of IAV-related deaths annually [,]. Type I interferons (e.g., IFN-α and IFN-β) are essential cytokines involved in the host antiviral response. Secreted by numerous cell types such as lymphocytes, monocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells, fibroblasts, endothelial cells, osteoblasts and others, type I interferons: (1) limit viral spread by inducing antiviral states in infected and neighboring cells; (2) stimulate antigen presentation and natural killer cell function; and (3) promote antigen-specific T and B cell responses and immunological memory. Interestingly, mitochondria play a major part in innate immune signaling against viruses and the production of type I interferons and will be discussed further.

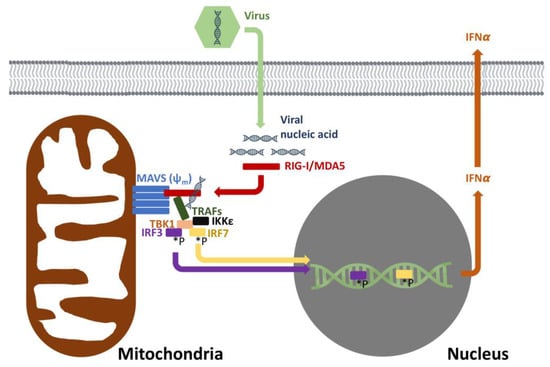

RLRs (e.g., RIG-I and MDA5) are cytosolic receptors that recognize viral RNA. Consequent to binding viral RNA, RIG-I and MDA5 mobilize the mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein (MAVS) [,]. MAVS is a 56 kDa protein which contains an N-terminal caspase recruitment domain (CARD), a proline-rich region and a C-terminal transmembrane domain. Anchored on the outer membrane of the mitochondria, peroxisomes and mitochondrial associated membranes (e.g., endoplasmic reticulum), MAVS assembles into prion-like aggregates following RIG-I or MDA5 binding (Figure 2). MAVS aggregates serve as a scaffold to recruit various TNF receptor associated factors (TRAFs), resulting in phosphorylation and nuclear translocation of interferon regulatory factors (IRFs) []. Downstream of MAVS, IRF3, IRF5 and IRF7 bind to their cognate promoters, leading to the production of type I interferons []. The localization of MAVS to the outer mitochondrial membrane is not coincidental. MAVS activity has been found to be dependent upon intact mitochondrial membrane potential, and by extension OXPHOS function [].

Figure 2.

Mitochondrial antiviral response. The recognition of viral nucleic acids involves mitochondria and intact membrane potential (ψm). RIG-I and MDA5 recognize cytoplasmic viral nucleic acids, leading to the oligomerization of MAVS. MAVS then sets in motion a signaling pathway that eventually leads to the phosphorylation (*P) of IRF3/7 with subsequent induction of IFNα to offer antiviral cellular protection. RIG-I = retinoic acid inducible gene I, MDA5 = melanoma differentiation-associated protein 5, MAVS = mitochondrial antiviral-signaling protein, TRAFs = TNF receptor associated factors, TBK1 = TANK binding kinase 1, IKKε = inhibitor of nuclear factor kappa-B kinase subunit epsilon, IRF 3 = interferon response factor 3, IRF 7 = interferon response factor 7, INFα = interferon alpha.

To date, studies addressing MAVS function during aging and its relationship to waning antiviral immunity are lacking. Decreased mitochondrial membrane potential, mitochondrial dysfunction and declining mitophagy occur in a variety of aging cell types [,], raising the question of whether MAVS dysfunction can occur due to mitochondrial failure with aging. Mitochondrial respiratory capacity is impaired in aging monocytes [] as is phosphorylation of IRF3 and IRF7, suggesting a link with MAVS []. As a result, type I IFN synthesis is significantly lower in dendritic cells and monocytes from aging individuals [,]. In addition to a decline in mitochondrial respiration, oxidative stress, another consequence of aging, may also be involved in this process [].

4. Is Impaired T-Cell Immunity in Aging Related to a Decline in Mitochondrial Function?

Aging-related decline in immune function (i.e., immunosenescence) renders older individuals more vulnerable to infectious diseases and cancer, resulting in increased morbidity and mortality. Besides increased susceptibility to infection, vaccine efficacy is significantly reduced in the elderly, limiting the utility of prophylaxis [,]. Undeniably, profound changes in T-cell function are evident in older individuals, and these changes may be related to a decline in mitochondrial function.

T-cells play a central role in the coordination of adaptive immune responses and cell-mediated immunity. The ability of T-cells to fulfill this role is dependent upon rapid cellular proliferation and differentiation. In response to infection, T-cells proliferate every 4–6 h, generating >1012 cells in one week [,]. This is accompanied by an increase in size, DNA remodeling, up-regulation of transcription factors and effector molecules, and increased expression of surface proteins [,], thus necessitating a large metabolic demand. To accomplish this task, metabolic fuels including fats, sugars and amino acids are actively transported across the cell membrane to feed the increase in energetic demands [,]. Along with this increased transport, T-cells undergo metabolic reprogramming during their transition from a naïve state to activated and differentiated cell types (e.g., effector, regulatory and memory cells).

The diverse roles played by mitochondria in T-cell activation emphasizes the potential mechanisms by which aging-related mitochondrial decline may contribute to immune dysfunction. Following stimulation of the T-cell receptor, T-cells undergo substantial changes in intermediary metabolism including an increase in glycolysis and OXPHOS [,,,,,]. In the presence of oxygen, pyruvate produced via glycolysis is fully oxidized in the mitochondria for energy in many cell types [,]. In T-cells, a significant proportion of glucose is not oxidized, but rather fermented to lactate from pyruvate via lactate dehydrogenase. This is done despite the presence of oxygen, and is termed aerobic glycolysis or Warburg metabolism [,,]. Although Warburg metabolism is viewed as energetically inefficient, the rate of glycolysis is 10–100 times faster than glucose oxidation by the mitochondria, yielding equivalent amounts of ATP []. The additional payoff of Warburg metabolism lies in pathways that are branch points off of glycolysis (e.g., pentose phosphate pathway) which yield reducing equivalents for biosynthesis and nucleotides. Despite this adoption of the Warburg phenotype, OXPHOS is still required for T-cell activation []. ATP derived from the mitochondrial respiration promotes enhanced glycolysis as well as the initiation of proliferation in activated T-cells []. While pyruvate is mostly diverted to lactate rather than acetyl-CoA via pyruvate dehydrogenase, TCA function and the generation of reducing equivalents in highly proliferating cells is still maintained through anapleurosis: glutamine is converted to α-ketoglutarate via glutaminolysis [,]. Bioenergetic studies of aging tissues are consistent with a progressive decline in mitochondrial respiratory function due to a decrease in respiratory complex activity, mitochondrial membrane potential, and impaired mitophagy [,]. As a result, impaired OXPHOS results in reduced ATP production, thus potentially limiting glycolysis, biosynthesis and the attainment of biomass during T-cell activation and proliferation.

Besides engaging in bioenergetics, mitochondria also function in T-cell activation by modulating secondary messengers including calcium (Ca2+) and reactive oxygen species (ROS). In activated T-cells, mitochondria localize to the immune synapse, and where they regulate Ca2+ flux [,]. In response to this calcium flux, ROS production via complex III of the respiratory chain is amplified, leading to nuclear factor of activated T-cells (NFAT) activation and subsequent interleukin-2 (IL-2) production []. Aged T-cells show reduced Ca2+ signaling, which could be partly due to deficits in Ca2+ regulation found in mitochondria of aged cells [,], theoretically yielding perturbations at the immune synapse causing diminished T-cell signaling and activation.

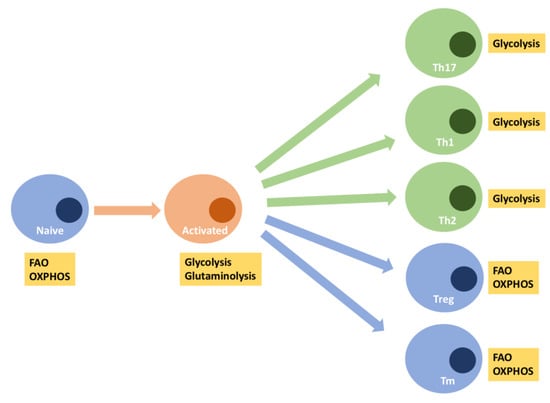

Depending on the cytokine milieu, helper T-cells (Th), marked by the surface expression of CD4, differentiate into various effector subsets comprising T-helper 1 (Th1), T-helper 2 (Th2), T-helper 17 (Th17), regulatory T-cells (Treg). Each of these T-cell subsets are unique in their responsibilities and are identified by their cytokine signatures. Accompanying these functional distinctions are differences in metabolic reprogramming (Figure 3). For example, for T-cells subsets involved in inflammation (e.g., Th1 and Th17), the Warburg metabolism instituted at T-cell activation persists []. Despite this primary use of glycolysis, intact OXPHOS is still necessary for their function []. The effects of mitochondrial dysfunction may be more readily seen in regulatory (Treg) and memory (Tmem) T-cells. Tregs, which serve to modulate the immune system and maintain tolerance, revert back to OXPHOS as their main pathway for generating energy upon differentiation []. Tmem follow a similar metabolic path. Tmem are critical for adaptive immune responses characterized by robust responses to secondary immune challenges. Unlike effector T-cells, Tmem do not undergo extensive proliferation and produce little or no cytokines. As such, the metabolic profile of Tmem are essentially catabolic, relying on OXPHOS and fatty acid oxidation [,]. Therefore, it is not surprising to find that CD8+ cytotoxic memory T-cells have high respiratory capacity and increased mitochondrial mass, which allows them to rapidly reactivate upon re-exposure to their cognate antigens [,]. Given the age-related decline in mitochondrial function as described above, T-cell subsets which are critical for immunosurveillance and the clearance of invading pathogens could be functionally impaired and may partially explain the vulnerability to infection and cancer with aging []. Emerging data also suggest that aging significantly affects Treg frequencies, subsets and function [], potentially leading to the increased incidence of autoimmunity, oftentimes seen with aging []. As noted above, Tmem also rely heavily on OXPHOS. Therefore, aging-related deficiencies in Tmem may also be traced to declining OXPHOS, manifesting as impaired immune memory to novel antigens and suboptimal boosts to existing memory [].

Figure 3.

T-cell activation and differentiation involved metabolic reprogramming. At rest, naïve T-cells primarily use OXPHOS to derive their energy. Following activation, T-cells switch to Warburg metabolism and glutaminolysis to support their proliferative needs. Differentiation into T-helper subsets can involve either the maintenance of the Warburg phenotype (i.e., Th17, Th1, Th2), or the reversion to OXPHOS with FAO (i.e., Treg, Tm) as an important fuel. FAO = mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation, OXPHOS = oxidative phosphorylation, Th17 = T-helper cell 17, Th1 = T-helper cell 1, Th2 = T-helper cell 2, Treg = regulatory T-cells, Tm = memory T-cells.

5. Conclusions

Virtually every country in the world is experiencing the challenges associated with accelerated growth in the aging population. With this graying of the population comes an increased incidence in diseases of aging, many of which have an immune component. As a result, understanding the pathophysiology of diseases of aging is now more important than ever. In this review, three main immune issues prevalent in the aging population were addressed: (1) inflamm-aging; (2) increased vulnerability to infection; and (3) declining T-cell immunity. The role of the mitochondria in inflammation and immunity, combined with the knowledge of a decline in mitochondrial function with aging, has been synthesized in this review in an effort to partially explain the immune phenotype associated with aging. However, further examination of this relationship is needed. As the methods of inquiry into mitochondrial biology continue to expand, so will investigations into the relationship between this ancient organelle and immunity in the aging population.

Funding

This work was supported by the intramural research program of the National Institutes of Health (HG200381-03).

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Martin, W.F.; Garg, S.; Zimorski, V. Endosymbiotic theories for eukaryote origin. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2015, 370, 20140330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, M.W. Mitochondrial evolution. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2012, 4, a011403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vafai, S.B.; Mootha, V.K. Mitochondrial disorders as windows into an ancient organelle. Nature 2012, 491, 374–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antico Arciuch, V.G.; Elguero, M.E.; Poderoso, J.J.; Carreras, M.C. Mitochondrial regulation of cell cycle and proliferation. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2012, 16, 1150–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quintana, A.; Schwindling, C.; Wenning, A.S.; Becherer, U.; Rettig, J.; Schwarz, E.C.; Hoth, M. T cell activation requires mitochondrial translocation to the immunological synapse. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 14418–14423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwindling, C.; Quintana, A.; Krause, E.; Hoth, M. Mitochondria positioning controls local calcium influx in T cells. J. Immunol. 2010, 184, 184–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sena, L.A.; Chandel, N.S. Physiological roles of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species. Mol. Cell 2012, 48, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weyand, C.M.; Goronzy, J.J. Aging of the Immune System. Mechanisms and Therapeutic Targets. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2016, 13 (Suppl. 5), S422–S428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, S.; Zhang, X.; Zheng, S.; Khanabdali, R.; Kalionis, B.; Wu, J.; Wan, W.; Tai, X. An Update on Inflamm-Aging: Mechanisms, Prevention, and Treatment. J. Immunol. Res. 2016, 2016, 8426874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, M.R.; Kaminski, J.J.; Kurt-Jones, E.A.; Fitzgerald, K.A. Pattern recognition receptors and the innate immune response to viral infection. Viruses 2011, 3, 920–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, D.; Kang, R.; Coyne, C.B.; Zeh, H.J.; Lotze, M.T. PAMPs and DAMPs: Signal 0s that spur autophagy and immunity. Immunol. Rev. 2012, 249, 158–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janeway, C.A., Jr.; Medzhitov, R. Innate immune recognition. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2002, 20, 197–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medzhitov, R. Innate immunity: Quo vadis? Nat. Immunol. 2010, 11, 551–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinon, F.; Burns, K.; Tschopp, J. The inflammasome: A molecular platform triggering activation of inflammatory caspases and processing of proIL-beta. Mol. Cell 2002, 10, 417–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenceslau, C.F.; McCarthy, C.G.; Goulopoulou, S.; Szasz, T.; NeSmith, E.G.; Webb, R.C. Mitochondrial-derived N-formyl peptides: Novel links between trauma, vascular collapse and sepsis. Med. Hypotheses 2013, 81, 532–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, L.V.; Hajizadeh, S.; Holme, E.; Jonsson, I.M.; Tarkowski, A. Endogenously oxidized mitochondrial DNA induces in vivo and in vitro inflammatory responses. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2004, 75, 995–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauser, C.J.; Sursal, T.; Rodriguez, E.K.; Appleton, P.T.; Zhang, Q.; Itagaki, K. Mitochondrial damage associated molecular patterns from femoral reamings activate neutrophils through formyl peptide receptors and P44/42 MAP kinase. J. Orthop. Trauma 2010, 24, 534–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Raoof, M.; Chen, Y.; Sumi, Y.; Sursal, T.; Junger, W.; Brohi, K.; Itagaki, K.; Hauser, C.J. Circulating mitochondrial DAMPs cause inflammatory responses to injury. Nature 2010, 464, 104–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Itagaki, K.; Hauser, C.J. Mitochondrial DNA Is Released by Shock and Activates Neutrophils Via P38 Map Kinase. Shock 2010, 34, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer, S.S.; He, Q.; Janczy, J.R.; Elliott, E.I.; Zhong, Z.; Olivier, A.K.; Sadler, J.J.; Knepper-Adrian, V.; Han, R.; Qiao, L.; et al. Mitochondrial cardiolipin is required for Nlrp3 inflammasome activation. Immunity 2013, 39, 311–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toksoy, A.; Sennefelder, H.; Adam, C.; Hofmann, S.; Trautmann, A.; Goebeler, M.; Schmidt, M. Potent NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation by the HIV Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitor Abacavir. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 2805–2814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossen, R.D.; Michael, L.H.; Hawkins, H.K.; Youker, K.; Dreyer, W.J.; Baughn, R.E.; Entman, M.L. Cardiolipin-Protein Complexes and Initiation of Complement Activation after Coronary-Artery Occlusion. Circ. Res. 1994, 75, 546–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaung, W.W.; Wu, R.; Ji, Y.; Dong, W.; Wang, P. Mitochondrial transcription factor A is a proinflammatory mediator in hemorrhagic shock. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2012, 30, 199–203. [Google Scholar]

- Julian, M.W.; Shao, G.; Vangundy, Z.C.; Papenfuss, T.L.; Crouser, E.D. Mitochondrial transcription factor A, an endogenous danger signal, promotes TNFalpha release via RAGE- and TLR9-responsive plasmacytoid dendritic cells. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e72354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer, S.S.; Pulskens, W.P.; Sadler, J.J.; Butter, L.M.; Teske, G.J.; Ulland, T.K.; Eisenbarth, S.C.; Florquin, S.; Flavell, R.A.; Leemans, J.C.; et al. Necrotic cells trigger a sterile inflammatory response through the Nlrp3 inflammasome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 20388–20393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunelle, J.K.; Bell, E.L.; Quesada, N.M.; Vercauteren, K.; Tiranti, V.; Zeviani, M.; Scarpulla, R.C.; Chandel, N.S. Oxygen sensing requires mitochondrial ROS but not oxidative phosphorylation. Cell Metab. 2005, 1, 409–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandel, N.S.; Trzyna, W.C.; McClintock, D.S.; Schumacker, P.T. Role of oxidants in NF-kappa B activation and TNF-alpha gene transcription induced by hypoxia and endotoxin. J. Immunol. 2000, 165, 1013–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakahira, K.; Hisata, S.; Choi, A.M. The Roles of Mitochondrial Damage-Associated Molecular Patterns in Diseases. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2015, 23, 1329–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinti, M.; Cevenini, E.; Nasi, M.; De Biasi, S.; Salvioli, S.; Monti, D.; Benatti, S.; Gibellini, L.; Cotichini, R.; Stazi, M.A.; et al. Circulating mitochondrial DNA increases with age and is a familiar trait: Implications for “inflamm-aging”. Eur. J. Immunol. 2014, 44, 1552–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Childs, B.G.; Durik, M.; Baker, D.J.; van Deursen, J.M. Cellular senescence in aging and age-related disease: From mechanisms to therapy. Nat. Med. 2015, 21, 1424–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, W.W.; Shay, D.K.; Weintraub, E.; Brammer, L.; Cox, N.; Anderson, L.J.; Fukuda, K. Mortality associated with influenza and respiratory syncytial virus in the United States. JAMA 2003, 289, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonsen, L.; Clarke, M.J.; Schonberger, L.B.; Arden, N.H.; Cox, N.J.; Fukuda, K. Pandemic versus epidemic influenza mortality: A pattern of changing age distribution. J. Infect. Dis. 1998, 178, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, H.; Kawai, T.; Kato, H.; Sato, S.; Takahashi, K.; Coban, C.; Yamamoto, M.; Uematsu, S.; Ishii, K.J.; Takeuchi, O.; et al. Essential role of IPS-1 in innate immune responses against RNA viruses. J. Exp. Med. 2006, 203, 1795–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, R.T.; Lacoste, J.; Nakhaei, P.; Sun, Q.; Yang, L.; Paz, S.; Wilkinson, P.; Julkunen, I.; Vitour, D.; Meurs, E.; et al. Dissociation of a MAVS/IPS-1/VISA/Cardif-1KK epsilon molecular complex from the mitochondrial outer membrane by hepatitis C virus NS3-4A proteolytic cleavage. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 6072–6083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.Y.; Gao, C.J. Regulation of MAVS activation through post-translational modifications. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2018, 50, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazear, H.M.; Lancaster, A.; Wilkins, C.; Suthar, M.S.; Huang, A.; Vick, S.C.; Clepper, L.; Thackray, L.; Brassil, M.M.; Virgin, H.W.; et al. IRF-3, IRF-5, and IRF-7 coordinately regulate the type I IFN response in myeloid dendritic cells downstream of MAVS signaling. PLoS Pathog. 2013, 9, e1003118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koshiba, T.; Yasukawa, K.; Yanagi, Y.; Kawabata, S. Mitochondrial Membrane Potential Is Required for MAVS-Mediated Antiviral Signaling. Sci. Signal. 2011, 4, ra7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugrue, M.M.; Tatton, W.G. Mitochondrial membrane potential in aging cells. Neurosignals 2001, 10, 176–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diot, A.; Morten, K.; Poulton, J. Mitophagy plays a central role in mitochondrial ageing. Mamm. Genome 2016, 27, 381–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pence, B.D.; Yarbro, J.R. Aging impairs mitochondrial respiratory capacity in classical monocytes. Exp. Gerontol. 2018, 108, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molony, R.D.; Nguyen, J.T.; Kong, Y.; Montgomery, R.R.; Shaw, A.C.; Iwasaki, A. Aging impairs both primary and secondary RIG-I signaling for interferon induction in human monocytes. Sci. Signal. 2017, 10, eaan2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, F.; Wang, X.; Zhang, L.; Lin, A.; Zhao, H.; Fikrig, E.; Montgomery, R.R. Impaired interferon signaling in dendritic cells from older donors infected in vitro with West Nile virus. J. Infect. Dis. 2011, 203, 1415–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stout-Delgado, H.W.; Yang, X.; Walker, W.E.; Tesar, B.M.; Goldstein, D.R. Aging impairs IFN regulatory factor 7 up-regulation in plasmacytoid dendritic cells during TLR9 activation. J. Immunol. 2008, 181, 6747–6756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, E.A.; Lum, L.G.; L’Hommedieu, G.; Goodwin, J.S. Specific humoral immunity in the elderly: In vivo and in vitro response to vaccination. J. Gerontol. 1993, 48, B231–B236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musher, D.M.; Chapman, A.J.; Goree, A.; Jonsson, S.; Briles, D.; Baughn, R.E. Natural and vaccine-related immunity to Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Infect. Dis. 1986, 154, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badovinac, V.P.; Haring, J.S.; Harty, J.T. Initial T cell receptor transgenic cell precursor frequency dictates critical aspects of the CD8(+) T cell response to infection. Immunity 2007, 26, 827–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, H.; Kim, T.S.; Braciale, T.J. The Cell Cycle Time of CD8(+) T Cells Responding In Vivo Is Controlled by the Type of Antigenic Stimulus. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e15423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, S.M.; Kaech, S.M.; Staron, M.M. The interface between transcriptional and epigenetic control of effector and memory CD8(+) T-cell differentiation. Immunol. Rev. 2014, 261, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Bevan, M.J. CD8(+) T cells: Foot soldiers of the immune system. Immunity 2011, 35, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macintyre, A.N.; Gerriets, V.A.; Nichols, A.G.; Michalek, R.D.; Rudolph, M.C.; Deoliveira, D.; Anderson, S.M.; Abel, E.D.; Chen, B.J.; Hale, L.P.; et al. The Glucose Transporter Glut1 Is Selectively Essential for CD4 T Cell Activation and Effector Function. Cell Metab. 2014, 20, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, L.V.; Rolf, J.; Emslie, E.; Shi, Y.B.; Taylor, P.M.; Cantrell, D.A. Control of amino-acid transport by antigen receptors coordinates the metabolic reprogramming essential for T cell differentiation. Nat. Immunol. 2013, 14, 500–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frauwirth, K.A.; Riley, J.L.; Harris, M.H.; Parry, R.V.; Rathmell, J.C.; Plas, D.R.; Elstrom, R.L.; June, C.H.; Thompson, C.B. The CD28 signaling pathway regulates glucose metabolism. Immunity 2002, 16, 769–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marjanovic, S.; Eriksson, I.; Nelson, B.D. Expression of a new set of glycolytic isozymes in activated human peripheral lymphocytes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1990, 1087, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marjanovic, S.; Wielburski, A.; Nelson, B.D. Effect of phorbol myristate acetate and concanavalin A on the glycolytic enzymes of human peripheral lymphocytes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1988, 970, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Rourke, A.M.; Rider, C.C. Glucose, glutamine and ketone body utilisation by resting and concanavalin A activated rat splenic lymphocytes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1989, 1010, 342–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.N.; Dillon, C.P.; Shi, L.Z.; Milasta, S.; Carter, R.; Finkelstein, D.; McCormick, L.L.; Fitzgerald, P.; Chi, H.B.; Munger, J.; et al. The Transcription Factor Myc Controls Metabolic Reprogramming upon T Lymphocyte Activation. Immunity 2011, 35, 871–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarasenko, T.N.; Pacheco, S.E.; Koenig, M.K.; Gomez-Rodriguez, J.; Kapnick, S.M.; Diaz, F.; Zerfas, P.M.; Barca, E.; Sudderth, J.; DeBerardinis, R.J.; et al. Cytochrome c Oxidase Activity Is a Metabolic Checkpoint that Regulates Cell Fate Decisions During T Cell Activation and Differentiation. Cell Metab. 2017, 25, 1268 e1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.G.; Thompson, C.B. Revving the engine: Signal transduction fuels T cell activation. Immunity 2007, 27, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krebs, H.A. The tricarboxylic acid cycle. Harvey Lect. 1948, Series 44, 165–199. [Google Scholar]

- Macintyre, A.N.; Rathmell, J.C. Activated lymphocytes as a metabolic model for carcinogenesis. Cancer Metab. 2013, 1, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shestov, A.A.; Liu, X.J.; Ser, Z.; Cluntun, A.A.; Hung, Y.P.; Huang, L.; Kim, D.; Le, A.; Yellen, G.; Albeck, J.G.; et al. Quantitative determinants of aerobic glycolysis identify flux through the enzyme GAPDH as a limiting step. eLife 2014, 3, e03342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Windt, G.J.; O’Sullivan, D.; Everts, B.; Huang, S.C.; Buck, M.D.; Curtis, J.D.; Chang, C.H.; Smith, A.M.; Ai, T.; Faubert, B.; et al. CD8 memory T cells have a bioenergetic advantage that underlies their rapid recall ability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 14336–14341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeBerardinis, R.J.; Mancuso, A.; Daikhin, E.; Nissim, I.; Yudkoff, M.; Wehrli, S.; Thompson, C.B. Beyond aerobic glycolysis: Transformed cells can engage in glutamine metabolism that exceeds the requirement for protein and nucleotide synthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 19345–19350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csibi, A.; Fendt, S.M.; Li, C.; Poulogiannis, G.; Choo, A.Y.; Chapski, D.J.; Jeong, S.M.; Dempsey, J.M.; Parkhitko, A.; Morrison, T.; et al. The mTORC1 pathway stimulates glutamine metabolism and cell proliferation by repressing SIRT4. Cell 2013, 153, 840–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.C.; Wei, Y.H. Mitochondria and aging. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2012, 942, 311–327. [Google Scholar]

- Sena, L.A.; Li, S.; Jairaman, A.; Prakriya, M.; Ezponda, T.; Hildeman, D.A.; Wang, C.R.; Schumacker, P.T.; Licht, J.D.; Perlman, H.; et al. Mitochondria are required for antigen-specific T cell activation through reactive oxygen species signaling. Immunity 2013, 38, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mather, M.W.; Rottenberg, H. The inhibition of calcium signaling in T lymphocytes from old mice results from enhanced activation of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2002, 123, 707–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murchison, D.; Zawieja, D.C.; Griffith, W.H. Reduced mitochondrial buffering of voltage-gated calcium influx in aged rat basal forebrain neurons. Cell Calcium 2004, 36, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buck, M.D.; O’Sullivan, D.; Klein Geltink, R.I.; Curtis, J.D.; Chang, C.H.; Sanin, D.E.; Qiu, J.; Kretz, O.; Braas, D.; van der Windt, G.J.; et al. Mitochondrial Dynamics Controls T Cell Fate through Metabolic Programming. Cell 2016, 166, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, C.J.; Hammerman, P.S.; Thompson, C.B. Fuel feeds function: Energy metabolism and the T-cell response. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2005, 5, 844–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, I.; Fruman, D.A. Regulation of quiescence in lymphocytes. Trends Immunol. 2003, 24, 380–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Windt, G.J.; Everts, B.; Chang, C.H.; Curtis, J.D.; Freitas, T.C.; Amiel, E.; Pearce, E.J.; Pearce, E.L. Mitochondrial respiratory capacity is a critical regulator of CD8+ T cell memory development. Immunity 2012, 36, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagger, A.; Shimojima, Y.; Goronzy, J.J.; Weyand, C.M. Regulatory T cells and the immune aging process: A mini-review. Gerontology 2014, 60, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadasz, Z.; Haj, T.; Kessel, A.; Toubi, E. Age-related autoimmunity. BMC Med. 2013, 11, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goronzy, J.J.; Weyand, C.M. Successful and Maladaptive T Cell Aging. Immunity 2017, 46, 364–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).