Confucian and Daoist Cultural Values in Ming-Style Chair Design: A Measurement Scale

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Cultural Values: Confucian, Daoist, and Their Distinctions

2.2. Design Implications of Confucian and Daoist Values in Ming-Style Chairs

2.3. Consumer Decision-Making Influenced by Confucian and Daoist Values

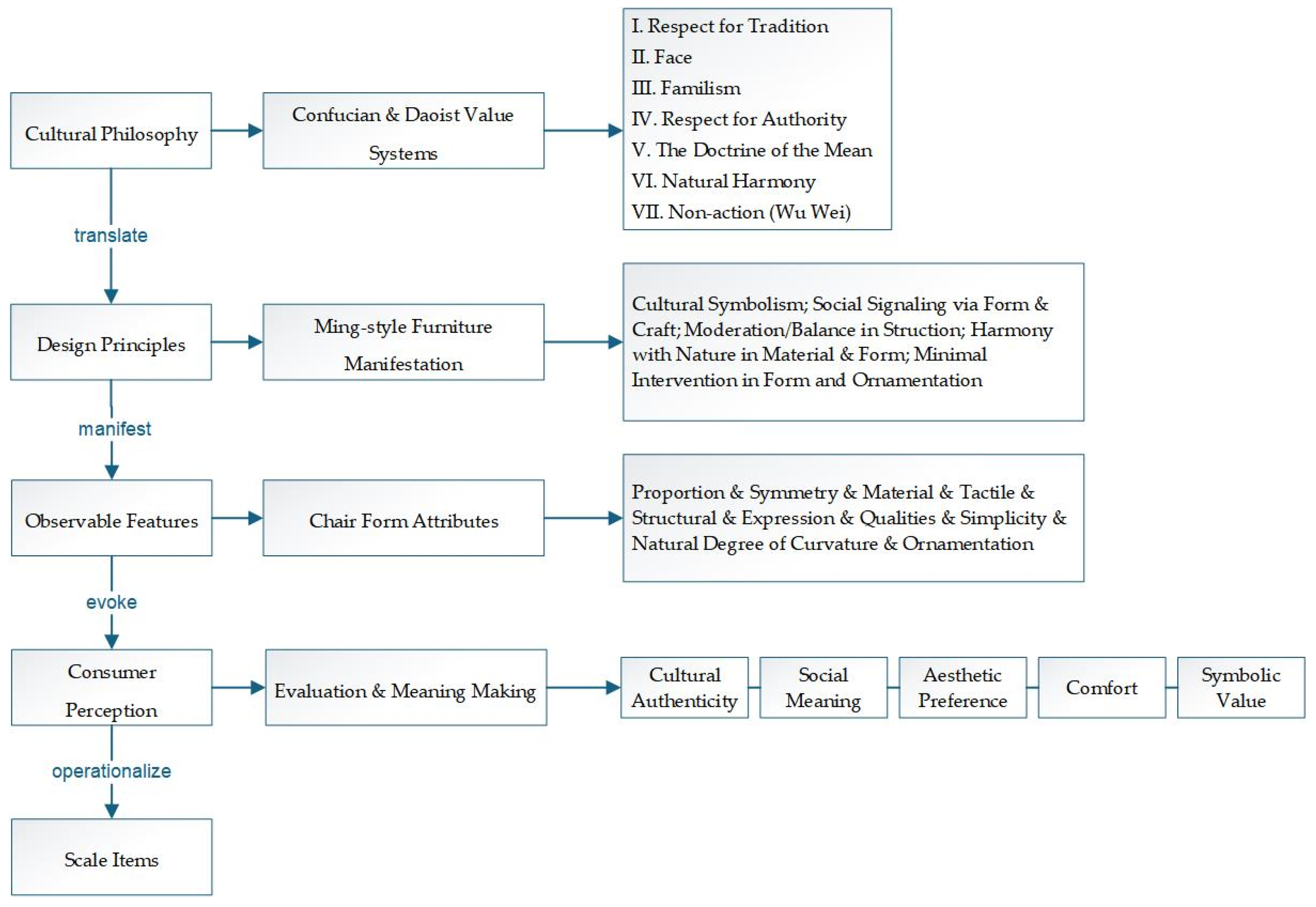

3. Scale Development

3.1. Initial Item Pool Generation

3.2. Exploratory Factor Analysis

3.2.1. Initial Questionnaire Sample

3.2.2. Item Purification

3.3. Confirmatory Factor Analysis and Reliability-Validity Assessment

3.3.1. Formal Sample Collection

3.3.2. Scale Reliability and Validity Analysis

3.3.3. Discriminant Validity

4. Discussion

4.1. Theoretical and Methodological Advancements over Existing Cultural Value Scales

4.2. The Cultural Foundations of Consumer Preferences

4.3. The Evolving Role of Social Status in Furniture Consumption

4.4. Demographic Insights: Understanding the Target Market

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Ming-Style Chair Innovative Design Scale for Confucian and Daoist Values

References

- Amin, T. Globalization and Cultural Homogenization: A Critical Examination. Kashf J. Multidiscip. Res. 2024, 1, 10–20. [Google Scholar]

- Hiswara, A.; Aziz, A.M.; Pujowati, Y.; Ade, N.; Sari, R. Cultural Preservation in a Globalized World: Strategies for Sustaining Heritage. West Sci. Soc. Humanit. Stud. 2023, 1, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auernhammer, J.; Roth, B.; Verganti, R.; Dell’era, C.; Swan, K.S. The Origin and Evolution of Stanford University’s Design Thinking: From Product Design to Design Thinking in Innovation Management. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2021, 38, 623–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, K. Media as a Catalyst of Cultural Homogenization: A Threat to Diversity of Culture in the Era of Globalization. J. East-West Thought 2024, 14, 218–228. Available online: https://erp.bharati.du.ac.in/smartprof/file_uploads/tmpFile/85/proofOfArticle_1751789012.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Liu, L.; Hongxia, Z. Research on Consumers’ Purchase Intention of Cultural and Creative Products—Metaphor Design Based on Traditional Cultural Symbols. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0301678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Azwan, H.; Mahdzir, A.; Ayn, N.; Sayuti, A. Inheritance and Innovation of Chinese Traditional Furniture Culture from the Contemporary Furniture Design Styles—Focus on Ming Dynasty Chair Furniture. Pak. J. Life Soc. Sci 2025, 23, 2545. Available online: http://TUENGR.COM/V16/16A1E.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Zajda, J.I.; Majhanovich, S. Globalization, Cultural Identity and Nation-Building: The Changing Paradigms; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2021; Available online: https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-94-024-2014-2 (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Xue, G.; Chen, J.; Lin, Z. Cultural Sustainable Development Strategies of Chinese Traditional Furniture: Taking Ming-Style Furniture for Example. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J. The Creation Concept of Ming-Style Furniture; Central Academy of Fine Arts: Beijing, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gan, S.; Halabi, K.N.M. Promoting Contemporary Ming Furniture Design Through Sustainable Development. In Proceedings of the 2023 5th International Conference on Literature, Art and Human Development (ICLAHD 2023); Atlantis Press: Paris, France, 2023; pp. 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, M. From the Perspectives of Scholars and Artisans: A Study on the Forms and Aesthetics of Ming-Style Furniture. Highlights Art Des. 2025, 9, 24–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Liu, M.; Dai, M. Aesthetic Analysis and Innovative Design of Ming and Qing Furniture. Innov. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Res. 2022, 2, 178–187. Available online: https://www.shanghaimuseum.net/mu/frontend/pg/article/id/CI00000291 (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Hu, X.; Chandhasa, R. The Study of Ming and Qing Dynasty Furniture Styles Using Analysis of the Principles of Furniture Design. J. Namib. Stud. Hist. Politics Cult. 2023, 33, 1531–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.; Xia, L.; Yuan, J. On the Impact of Jiangnan Furniture Market on Ming-Style Furniture in Ming Dynasty. Furnit. Inter. Des. 2023, 30, 52–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, X. Seeking the Roots of Craftsmanship: Analysis and Reflection on the Ontology Beauty of Ming-Style Furniture. Art Des. Res. 2022, 3, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J. Study on the Functional Adaptability of Ming-Style Furniture and the “Body & Function” Theory in Its Design. Furnit. Inter. Des. 2022, 29, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Monkhouse, L.; Barnes, B.R.; Hanh Pham, T.S. Measuring Confucian Values Among East Asian Consumers: A Four-Country Study. Asia Pac. Bus. Rev. 2013, 19, 320–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, O.; Varaksina, N.; Hinterhuber, A. The Influence of Cultural Differences on Consumers’ Willingness to Pay More for Sustainable Fashion. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 442, 141024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Gao, L.; Zhang, X.; Wan, Y. Research on Consumer Values under the Chinese Cultural Context—Scale Development and Comparison. Manag. World 2014, 4, 90–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chung, T.; Lai, P.C. Go Sustainability—Willingness to Pay for Eco-Agricultural Innovation: Understanding Chinese Traditional Cultural Values and Label Trust Using a VAB Hierarchy Model. Sustainability 2023, 15, 751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikumori, M.; Maruyama, Y.; Ishii, R. Influencers’ Follower Numbers, Consumers’ Cultural Value Orientation, and Purchase Intention: Evidence from Japan, the United Kingdom, and Singapore. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2025, 37, 350–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, G.; Chen, J. Strategies for Applying Shape Grammar to Wooden Furniture Design: Taking Traditional Chinese Ming-Style Recessed-Leg Table as an Example. BioResources 2024, 19, 1707–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Confucius. The Analects; China Book Company: Beijing, China, 2006.

- Du, Y. Fun and Principles: Furniture Design Under the Collaboration of Literati and Craftsmen in the Late Ming Dynasty. Ph.D. Thesis, Nanjing University of the Arts, Nanjing, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Laozi. Dao De Jing (Tao Te Ching); Zhonghua Book Company: Beijing, China, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y. Ming-Style Furniture Research, 2nd ed.; China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, L.H.; Ho, Y.L.; Lin, W.H.E. Confucian and Daoist Work Values: An Exploratory Study of the Chinese Transformational Leadership Behavior. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 113, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, D. The Cognitive Psychotherapy According to Taoism: A Technical Brief Introduction. Chin. Ment. Health J. 1998, 12, 188–190. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, Z. A Study on the Scientific Aspects and Cultural Values of Ming-Style Furniture. Doctoral Dissertation, Nanjing Forestry University, Nanjing, China, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, J. Research on Ming-Style Furniture System. Doctoral Dissertation, Northeast Forestry University, Harbin, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, C.; Zheng, Q. A Study on the Aesthetic Characteristics of Ming-Style Furniture. Furnit. Inter. Des. 2021, 264, 9–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, W. Application of Moulding Type in Modeling of Ming Style Furniture. China Wood Ind. 2001, 15, 17–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y. Research of Space Composition Modality on Chairs of the Ming-Style Chair. Doctoral Dissertation, Northeast Forestry University, Harbin, China, 2010. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbname=CMFD2011&filename=2010242319.nh (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Zhou, L. Study on Form Design of Ming-Style Chair. Doctoral Dissertation, Suzhou University, Suzhou, China, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, X. A Study on the Design of Ming-Style Armchairs. Master’s Thesis, Northeast Forestry University, Harbin, China, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, M. The Research on the Traditional Aesthetic Connotations of the Ming-Style Furniture. Doctoral Dissertation, Northeast Forestry University, Harbin, China, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, T.; Niu, X. Analysis on the Image of Ming-Style Chair Based on Eye Movement Tracking Technique. Packag. Eng. 2018, 39, 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, J.; Wu, Z. The Structural Aesthetics and Cultural Images of Chinese Ming-style Furniture. Furnit. Inter. Des. 2012, 09, 16–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, W. Study on the Artistic Form of Ming-Style Furniture. Doctoral Dissertation, Shenyang Jianzhu University, Shenyang, China, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, G. National Cultures in Four Dimensions: A Research-Based Theory of Cultural Differences Among Nations. Int. Stud. Manag. Organ. 1983, 13, 46–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connection, C.C. Chinese Values and the Search for Culture-Free Dimensions of Culture. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 1987, 18, 43–164. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, G.; Bond, M.H. The Confucius Connection: From Cultural Roots to Economic Growth. Organ. Dyn. 1988, 16, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G.; Minkov, M. Long- versus Short-Term Orientation: New Perspectives. Asia Pac. Bus. Rev. 2010, 16, 493–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.M.; Rasul, T.; Ahmed, S.S.; Ladeira, W.J.; Santini, F.d.O.; Azhar, M.; Khan, M. Cultural Values in Consumer-Centric Research: A Hybrid Review Exploring Trends, Structure, and Future Research Trajectories. Glob. Bus. Organ. Excel. 2025, 0, 1–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G. The Psychology and Behavior of the Chinese People: Indigenous Research; Renmin University of China Press: Beijing, China, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J. A Tentative Research into the Correlation Between College Students’ Confucianism & Taoism Values and Their Mental Health. Doctoral Dissertation, Jilin University, Changchun, China, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y. A Study on the Moderating Effects of the Confucian and Daoist Value on the Relationship Between Life Events and Mental Health. Doctoral Dissertation, Beijing Forestry University, Beijing, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Churchill, G.A. Measure and Construct Validity Studies. J. Mark. Res. 1979, 16, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinkin, T.R. A Review of Scale Development Practices in the Study of Organizations. J. Manag. 1995, 21, 967–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prentice, C.; Han, X.Y.; Li, Y.Q. Customer Empowerment to Co-Create Service Designs and Delivery: Scale Development and Validation. Serv. Mark. Q. 2016, 37, 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yau, O.H.M. Chinese Cultural Values: Their Dimensions and Marketing Implications. Eur. J. Mark. 1988, 22, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M. A Study on the Cultural Values Motivation of Chinese Consumer Purchasing Behavior; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, J. Confucian Traditional Values in the Workplace: Theory, Measurement, and Validity Testing. Nankai Bus. Rev. 2012, 15, 66–79. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, Y.N.; Thyroff, A.; Rapert, M.I.; Park, S.Y.; Lee, H.J. To Be or Not to Be Green: Exploring Individualism and Collectivism as Antecedents of Environmental Behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1052–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennig, A. Daoism in Management. Philos. Manag. 2017, 16, 161–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVellis, R.F.; Thorpe, C.T. Scale Development: Theory and Applications, 5th ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2021; Available online: https://books.google.com.my/books?id=FX0_EAAAQBAJ (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Pan, L.; Zhang, M.; Gursoy, D.; Lu, L. Development and Validation of a Destination Personality Scale for Mainland Chinese Travelers. Tour. Manag. 2017, 59, 338–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Shen, W. Empirical Methods in Organizational and Management Research, 3rd ed.; Peking University Press: Beijing, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson: London, UK, 2009; p. 123. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, H.F. An Index of Factorial Simplicity. Psychometrika 1974, 39, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, G.T.; Wang, W. Development and Validation of a Casino Service Quality Scale: A Holistic Approach. Tour. Manag. 2022, 88, 104419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comrey, A.L. Factor-Analytic Methods of Scale Development in Personality and Clinical Psychology. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1988, 56, 754–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson: London, UK, 2014; pp. 619–620. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J. Study on the Idea of Creation in Ming-style Furniture Design. Packag. Eng. 2018, 39, 214–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reference | Scale Description | Dimensions | Items | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Chinese Culture Connection (1987) [41] | Investigate the universality and uniqueness of cultural values from a Chinese cultural perspective using the Chinese Value Survey (CVS). | Confucian Work Dynamism; Collectivism; Human-heartedness; Moral Discipline; Confucian Work Dynamism: Thrift; Perseverance; Harmony with others; Adaptability; Trustworthiness; Respect for Tradition | 6 items | The sample consists of university students, which may not represent cultural values across different ages and social strata. The universality of cultural dimensions requires further validation. |

| Hofstede & Bond (1988) [42] | Explores the relationship between Confucian culture and economic growth, combining IBM research and CVS results. | Confucian Dynamism; Power Distance; Individualism vs. Collectivism; Masculinity vs. Femininity Confucian Dynamism: Thrift; Perseverance; Respect for Tradition; Protecting Face; Harmony | 5 items | The sample mainly consists of students, which may not fully represent broader social groups. |

| Yau (1988) [51] | Analyzes the five main dimensions of Chinese cultural values and their marketing implications using Kluckhohn and Strodtbeck’s cultural value orientation model. | Man-nature Orientation; Man-to-himself Orientation; Relational Orientation; Time Orientation; Personal Activity Orientation; Yuan (Fate); Modesty; Face; Respect for Authority; Past-time Orientation; The Doctrine of the Mean | Not specified | The sample is primarily based on Hong Kong students and consumers, which may not fully represent broader Chinese social groups. |

| Yang (2004) [45] | Confucian Traditional Values Scale | Familism; Modesty and Compliance; Face Relations; Unity and Harmony; Hardship Endurance | 40 items | Self-compiled Daoist Traditional Values Scale and Yang Guosu’s Confucian Traditional Values Questionnaire were used, but no scales related to design fields were involved. |

| Zhang (2009) [46] | First developed a Daoist Values Scale. | Knowledge and Open-mindedness; Going with the Flow; Few Desires; Detachment and Contentment; Reverse Dialectics; Returning to Simplicity | 19 items | Self-compiled Daoist Traditional Values Scale was used. |

| Hofstede & Minkov (2010) [43] | Introduces long-term/short-term orientation as a cultural dimension and examines its relationship with economic growth, school performance, business values, and environmental values. | Long-term/Short-term Orientation (Thrift, National Pride, Serving Others); Confucian Dimension (Persistence, Thrift, Status-based Relationships, Reciprocity, Respect for Tradition, Face Protection, Personal Stability) | Long-term/Short-term Orientation (LTO/STO) (3 items); Confucian Dimension (8 items) | Study did not involve consumer behavior, focusing instead on the relationship between cultural dimensions and economy, education, and environment. |

| Zhang (2010) [52] | Developed three Chinese traditional cultural values measurement models: Confucian, Daoist, and Buddhist Values Scales, and validated their reliability and validity. | Confucian Values Dimensions (Proper Conduct, Dignity Maintenance, Gender Equality, Rights Protection); Daoist Values Dimensions (Reverence for Nature, Going with the Flow); Buddhist Values Dimensions (Fairness and Equality, Belief in Fate) | C-VAL (11 items); T-VAL (8 items); B-VAL (4 items) | Sample only from Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou, which may not fully represent the values of consumers in all regions of China. |

| Wang & Zhang (2012) [53] | Measures Confucian traditional values displayed by employees in the workplace. | Relationship Orientation; Respect for Authority; Tolerance and Altruism; Face Principle | 23 items | Low factor loadings for the authority dimension; validity is relatively low. The cross-cultural applicability of the scale has not been verified. One-time data collection may affect the robustness of the results. |

| Monkhouse et al. (2013) [17] | Developed and validated a scale to measure Confucian values among East Asian consumers. | Face Saving; Humility; Group Orientation; Hierarchy; Reciprocity | 24 items | Study is based on samples from four East Asian cities (Tokyo, Hanoi, Beijing, and Singapore), not covering broader Chinese consumer groups. |

| Cho et al. (2013) [54] | Explores the impact of cultural dimensions (e.g., individualism and collectivism) on environmental behavior and develops a Confucian Collectivism Scale. | Confucian Collectivism Dimensions (Group Behavioral Norms; Group Conformity; Interdependence; Face-saving) | 5 items | Scale validation based on university student samples, which may not fully reflect broader populations (e.g., different age groups or occupational groups). |

| Lin et al. (2013) [27] | Developed and validated scales for Confucian and Daoist work values to study the relationship between traditional Chinese values and transformational leadership behavior. | Confucian Work Values (Benevolence, Righteousness, Propriety, Wisdom, Trustworthiness); Daoist Work Values (Non-action, Naturalness, Softness, Humility) | Confucian Work Values (6 items); Daoist Work Values (6 items) | Study focused on leadership behavior, not consumer values; sample limited to Taiwan region. |

| Pan et al. (2014) [19] | Developed the Chinese Consumer Values Scale (CCVAL). | First-order Factors: 8 factors (Practical Rationality, Doctrine of the Mean, Face Image, Independence, Striving for Progress, Differential Relationship, Reciprocal Relationship, Authority Conformity); Second-order Factors: 3 factors (Philosophy of Life, Self-awareness, Interpersonal Relationship) | 82 items (initial)/39 items (final) | Study based on samples from mainland China, but limited to Shanghai and Beijing, lacking national representativeness. |

| Zhang (2015) [47] | Developed Daoist and Confucian Values Questionnaires. | Confucian Values (Familism, Modesty and Compliance, Face Relations, Unity and Harmony, Hardship Endurance); Daoist Values (Peaceful Mindset, Going with the Flow, Contentment with Humility, Detachment, Dialectical Thinking) | Confucian Values (40 items); Daoist Values (42 items) | Developed the Daoist Values Questionnaire and explored its structural characteristics; compared the impact mechanisms of Daoist and Confucian values on mental health; limited sample size, primarily based on university students, which may not apply to other age groups or occupational groups. |

| Hennig (2017) [55] | Explores the potential application of Daoist and Confucian philosophies in management theory and analyzes their impact on modern management practices. | Confucian Values (Benevolence, Righteousness, Propriety, Wisdom, Trustworthiness); Daoist Values (Natural Harmony, Non-action, Softness, Humility) | Not specified | The article does not provide specific scale items but discusses the application of these philosophical ideas through theoretical discussion and case analysis. |

| Wang et al. (2023) [20] | Focuses on the impact of unique Chinese cultural values, such as Confucian collectivism and Daoism, on green food consumption behavior. | Confucian Collectivism Dimensions (Tradition, Face, Responsibility, Authority); Daoist Dimensions: Nature and Harmony | 7 items: Confucian Collectivism (4 items); Daoist (3 items) | Scale dimensions may be overly simplified or insufficiently comprehensive; item content is too abstract; may not be easily generalized to other cultural contexts. |

| Dimension | Item | References |

|---|---|---|

| I. Respect for Tradition | RT1: Traditional chairs are an important carrier of cultural heritage. | [20,41,42,43] |

| RT2: Chairs that incorporate traditional cultural elements have greater cultural value. | ||

| RT3: Traditional style chairs can evoke cultural identity and appreciation. | ||

| RT4: Chair designs can integrate traditional culture into modern life. | ||

| RT5: Chairs with regional characteristics can evoke a sense of familiarity and warmth. | ||

| RT6: Traditional chairs carry the memory and emotion of history. | ||

| RT7: The carvings and patterns on traditional chairs tell historical stories. | ||

| RT8: Traditional chairs convey a sense of history and culture through classic design. | ||

| II. Face | FC1: Brand chairs can elevate social status. | [17,42,43,51,52,54] |

| FC2: Chair designs in important settings reflect identity and temperament. | ||

| FC3: High-end chairs can showcase a sense of achievement. | ||

| FC4: Custom chair designs can reflect unique tastes and personality. | ||

| FC5: Chairs with distinctive designs attract attention. | ||

| FC6: The quality and details of chairs enhance the style of the home environment. | ||

| FC7: Chairs with exquisite craftsmanship reflect a pursuit of a high-quality lifestyle. | ||

| FC8: Chair designs in public spaces enhance the image and reputation of the venue. | ||

| III. Familism | FM1: Family members’ opinions play a key role in chair selection. | [20,45,47] |

| FM2: Family needs and preferences are prioritized when choosing a chair. | ||

| FM3: Chairs should be suitable for family members of all ages. | ||

| FM4: The multifunctionality of chairs is very important for daily family use. | ||

| FM5: There is a preference for chairs that promote interaction among family members. | ||

| FM6: Chair designs should reflect the warmth and closeness of the family. | ||

| FM7: Chairs should reflect the family’s values and traditions. | ||

| FM8: The safety of chairs is crucial for the health and well-being of family members. | ||

| IV. Respect for Authority | RA1: I prefer well-known chair brands that everyone recognizes. | [17,19,42,52] |

| RA2: I prefer chairs designed by famous designers. | ||

| RA3: If a chair has a unique design, I think the brand is more prestigious. | ||

| RA4: If a chair brand is recommended by experts or authoritative institutions, I trust it more. | ||

| RA5: I pay attention to whether a chair brand has won any famous awards or certifications. | ||

| RA6: If a chair brand is featured in reputable magazines or websites, I am more willing to choose it. | ||

| RA7: I trust chair brands that have cooperated with well-known institutions or large projects. | ||

| RA8: Chairs designed by famous designers have higher collectible value. | ||

| V. The Doctrine of the Mean | DM1: Chair design should balance function and aesthetics. | [19,51] |

| DM2: The size and function of the chair should match the home space. | ||

| DM3: Chair design should be moderate, avoiding excessive complexity or simplicity. | ||

| DM4: Chair design should strike a balance between tradition and modernity. | ||

| DM5: Chair design should emphasize overall harmony, avoiding overemphasis on a single feature. | ||

| DM6: The color scheme of the chair should be balanced, avoiding extremes. | ||

| DM7: Chair design should coordinate with other furniture. | ||

| DM8: Chair design should balance comfort and durability. | ||

| VI. Natural Harmony | NH1: Chair design should balance functionality and aesthetics. | [20,46,51,52,55] |

| NH2: The size and function of the chair should be natural and harmonious. | ||

| NH3: Chair design should maintain moderation, avoiding excessive complexity or simplicity. | ||

| NH4: Chair design should strike a balance between tradition and modernity. | ||

| NH5: Chair design should emphasize overall harmony, avoiding overemphasis on any single feature. | ||

| NH6: The color scheme of the chair should be balanced, avoiding extremes. | ||

| NH7: Chair design should coordinate with other furniture. | ||

| NH8: Chair design should balance comfort and durability. | ||

| VII. Non-action (Wu Wei) | WW1: Chair design should follow natural forms and minimize human intervention. | [17,51,55] |

| WW2: Chair design should respect the characteristics of materials and make full use of their advantages. | ||

| WW3: Chair design should apply natural principles and structures, minimizing unnecessary supports. | ||

| WW4: Chair design should align with user habits and avoid being overly guiding. | ||

| WW5: Chair design should minimize unnecessary decoration, maintaining a natural and minimalist style. | ||

| WW6: Chair design should balance functionality and aesthetics, reflecting ease. | ||

| WW7: Chair design should adapt to different scene requirements, flexible but not forced. | ||

| WW8: Chair design should convey a natural and comfortable lifestyle. |

| Items | Corrected Item-Total Correlation | Cronbach’s Alpha If Item Deleted | Items | Corrected Item-Total Correlation | Cronbach’s Alpha If Item Deleted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RT1 | 0.599 | 0.819 | RA5 | 0.718 | 0.885 |

| RT2 | 0.503 | 0.831 | RA6 | 0.768 | 0.881 |

| RT3 | 0.647 | 0.813 | RA7 | 0.652 | 0.891 |

| RT4 | 0.507 | 0.831 | RA8 | 0.566 | 0.898 |

| RT5 | 0.539 | 0.827 | DM1 | 0.609 | 0.841 |

| RT6 | 0.667 | 0.812 | DM2 | 0.55 | 0.847 |

| RT7 | 0.53 | 0.831 | DM3 | 0.709 | 0.829 |

| RT8 | 0.627 | 0.816 | DM4 | 0.641 | 0.837 |

| FC1 | 0.392 | 0.805 | DM5 | 0.414 | 0.865 |

| FC2 | 0.585 | 0.752 | DM6 | 0.645 | 0.836 |

| FC3 | 0.574 | 0.751 | DM7 | 0.582 | 0.844 |

| FC4 | 0.574 | 0.753 | DM8 | 0.711 | 0.83 |

| FC5 | 0.557 | 0.758 | NH1 | 0.582 | 0.831 |

| FC6 | 0.349 | 0.785 | NH2 | 0.617 | 0.83 |

| FC7 | 0.579 | 0.755 | NH3 | 0.464 | 0.843 |

| FC8 | 0.517 | 0.762 | NH4 | 0.606 | 0.828 |

| FM1 | 0.672 | 0.781 | NH5 | 0.725 | 0.81 |

| FM2 | 0.546 | 0.802 | NH6 | 0.559 | 0.833 |

| FM3 | 0.541 | 0.802 | NH7 | 0.613 | 0.827 |

| FM4 | 0.684 | 0.781 | NH8 | 0.581 | 0.831 |

| FM5 | 0.663 | 0.783 | WW1 | 0.542 | 0.79 |

| FM6 | 0.625 | 0.791 | WW2 | 0.574 | 0.789 |

| FM7 | 0.501 | 0.808 | WW3 | 0.58 | 0.782 |

| FM8 | 0.095 | 0.848 | WW4 | 0.658 | 0.776 |

| RA1 | 0.615 | 0.895 | WW5 | 0.38 | 0.821 |

| RA2 | 0.717 | 0.886 | WW6 | 0.504 | 0.795 |

| RA3 | 0.733 | 0.884 | WW7 | 0.536 | 0.789 |

| RA4 | 0.75 | 0.883 | WW8 | 0.61 | 0.778 |

| Item | Factor Loadings | Cronbach’s Alpha | % of Variance |

|---|---|---|---|

| I. Respect for Tradition | 0.816 | 13.559 | |

| RT1 | 0.694 | ||

| RT2 | 0.53 | ||

| RT3 | 0.723 | ||

| RT4 | 0.553 | ||

| RT5 | 0.546 | ||

| RT6 | 0.64 | ||

| RT7 | 0.65 | ||

| II. Face | 0.695 | 11.8 | |

| FC3 | 0.746 | ||

| FC4 | 0.66 | ||

| FC7 | 0.574 | ||

| III. Familism | 0.842 | 10.232 | |

| FM1 | 0.599 | ||

| FM2 | 0.601 | ||

| FM3 | 0.601 | ||

| FM4 | 0.739 | ||

| FM5 | 0.67 | ||

| FM6 | 0.671 | ||

| IV. Respect for Authority | 0.901 | 9.865 | |

| RA1 | 0.581 | ||

| RA2 | 0.682 | ||

| RA3 | 0.738 | ||

| RA4 | 0.865 | ||

| RA5 | 0.769 | ||

| RA6 | 0.818 | ||

| RA7 | 0.671 | ||

| RA8 | 0.672 | ||

| V. The Doctrine of the Mean | 0.865 | 10.292 | |

| DM1 | 0.611 | ||

| DM2 | 0.687 | ||

| DM3 | 0.672 | ||

| DM4 | 0.622 | ||

| DM6 | 0.649 | ||

| DM7 | 0.671 | ||

| DM8 | 0.789 | ||

| VI. Natural and Wuwei | 0.854 | 8.914 | |

| NH2 | 0.729 | ||

| NH5 | 0.643 | ||

| WW1 | 0.635 | ||

| WW3 | 0.513 | ||

| WW8 | 0.55 |

| Dimension | Category | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 162 | 36.8 |

| Female | 278 | 63.2 | |

| Age Group | 0–20 years | 17 | 3.9 |

| 21–30 years | 229 | 52 | |

| 31–40 years | 153 | 34.8 | |

| 41–50 years | 23 | 5.2 | |

| 51–60 years | 16 | 3.6 | |

| 61 years and above | 2 | 0.5 | |

| Profession | Student | 89 | 20.2 |

| State-owned enterprise | 57 | 13 | |

| Public institution | 51 | 11.6 | |

| Civil servant | 14 | 3.2 | |

| Private enterprise | 201 | 45.7 | |

| Foreign-funded enterprise | 28 | 6.4 | |

| Highest Education Level | Primary school and below | 2 | 0.5 |

| Junior high school | 2 | 0.5 | |

| General high school/Secondary vocational/Technical school | 7 | 1.6 | |

| Associate degree | 18 | 4.1 | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 306 | 69.5 | |

| Master’s degree | 93 | 21.1 | |

| Doctorate | 12 | 2.7 | |

| Understanding of Ming-style chair | Slightly understand | 208 | 47.3 |

| Very well understand | 18 | 4.1 | |

| Understand somewhat | 159 | 36.1 | |

| Do not understand at all | 55 | 12.5 | |

| Usage Experience | Yes | 167 | 38 |

| No | 273 | 62 | |

| Are you a professional engaged in the fields of home furnishing, art, design, or collection? | Yes | 386 | 87.7 |

| No | 54 | 12.3 |

| Model Fit Indices | RMSEA | RMR | GFI | CFI | NFI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Index Requirements | <3.0 | <0.06 | <0.05 | ≥0.90 | ≥0.90 | ≥0.90 |

| Original Model | 1.57 | 0.036 | 0.032 | 0.888 | 0.939 | 0.85 |

| Current Model | 1.203 | 0.022 | 0.021 | 0.991 | 0.951 | 0.95 |

| Dimension | Item | Unstd. | S.E. | Z | P | std. | Cronbach’s α | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RT | RT1: Traditional chairs are an important carrier of cultural heritage. | 1 | 0.776 | 0.824 | 0.824 | 0.61 | |||

| RT6: Traditional chairs carry the memory and emotion of history. | 0.966 | 0.065 | 14.755 | *** | 0.782 | ||||

| RT7: The carvings and patterns on traditional chairs tell historical stories. | 0.973 | 0.066 | 14.779 | *** | 0.785 | ||||

| FC | FC3: High-end chairs can showcase a sense of achievement. | 1 | 0.863 | 0.806 | 0.81 | 0.589 | |||

| FCnew1: Avoiding mass-market designs can maintain face. | 0.878 | 0.062 | 14.14 | *** | 0.742 | ||||

| FCnew2: Choosing expensive chairs beyond one’s financial means is for the sake of maintaining face | 0.701 | 0.052 | 13.401 | *** | 0.686 | ||||

| RA | RA4: If a chair brand is recommended by experts or authoritative institutions, I trust it more. | 1 | 0.744 | 0.747 | 0.782 | 0.544 | |||

| RA6: If a chair brand is featured in reputable magazines or websites, I am more willing to choose it. | 0.986 | 0.078 | 12.584 | *** | 0.729 | ||||

| RA7: I trust chair brands that have cooperated with well-known institutions or large projects. | 0.977 | 0.077 | 12.667 | *** | 0.74 | ||||

| DM | DM1: Chair design should balance function and aesthetics. | 1 | 0.799 | 0.836 | 0.839 | 0.635 | |||

| DM4: Chair design should strike a balance between tradition and modernity. | 1.17 | 0.074 | 15.821 | *** | 0.797 | ||||

| DM7: Chair design should coordinate with other furniture. | 0.998 | 0.063 | 15.786 | *** | 0.794 | ||||

| FM | FM1: Family members’ opinions play a key role in chair selection. | 1 | 0.737 | 0.771 | 0.773 | 0.531 | |||

| FM5: There is a preference for chairs that promote interaction among family members. | 0.995 | 0.083 | 12.003 | *** | 0.718 | ||||

| FM6: Chair designs should reflect the warmth and closeness of the family. | 0.917 | 0.076 | 12.084 | *** | 0.731 | ||||

| NW | NH2: The size and function of the chair should be natural and harmonious. | 1 | 0.696 | 0.749 | 0.756 | 0.508 | |||

| WW3: Chair design should apply natural principles and structures, minimizing unnecessary supports. | 1.256 | 0.109 | 11.554 | *** | 0.732 | ||||

| WW8: Chair design should convey a natural and comfortable lifestyle. | 0.935 | 0.082 | 11.423 | *** | 0.71 |

| Dimension | Mean | SD | NW | FM | DM | RA | FC | RT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NW | 4.26 | 0.618 | 0.713 | |||||

| FM | 4.01 | 0.72 | 0.397 | 0.729 | ||||

| DM | 4.42 | 0.588 | 0.392 | 0.219 | 0.797 | |||

| RA | 3.78 | 0.749 | 0.262 | 0.373 | 0.128 | 0.738 | ||

| FC | 3.65 | 0.835 | 0.142 | 0.149 | 0.115 | 0.451 | 0.767 | |

| RT | 4.41 | 0.572 | 0.405 | 0.264 | 0.214 | 0.197 | 0.159 | 0.781 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Gao, T.; Yusoff, I.S.M.; Che Me, R. Confucian and Daoist Cultural Values in Ming-Style Chair Design: A Measurement Scale. Culture 2026, 2, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/culture2010003

Gao T, Yusoff ISM, Che Me R. Confucian and Daoist Cultural Values in Ming-Style Chair Design: A Measurement Scale. Culture. 2026; 2(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/culture2010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleGao, Ting, Irwan Syah Mohd Yusoff, and Rosalam Che Me. 2026. "Confucian and Daoist Cultural Values in Ming-Style Chair Design: A Measurement Scale" Culture 2, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/culture2010003

APA StyleGao, T., Yusoff, I. S. M., & Che Me, R. (2026). Confucian and Daoist Cultural Values in Ming-Style Chair Design: A Measurement Scale. Culture, 2(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/culture2010003