Abstract

To better serve human life with smart and harmonic communication between the real and digital worlds, wearable human–machine interfaces (HMIs) with edge computing capabilities indicate the path to the next revolution of information technology. In this review, we focus on wearable HMIs and highlight several key aspects which are worth investigating. Firstly, we review wearable HMIs powered by commercial-ready technologies, highlighting some limitations. Next, to establish a dual-way interaction for exchanging comprehensive information, sensing and feedback functions on the human body need to be customized based on specific scenarios. Power consumption is another primary issue that is critical to wearable applications due to limited space, one that is possible to be solved by energy harvesting techniques and self-powered data transmission approaches. To further improve the data interpretation with higher intelligence, machine learning (ML)-assisted analysis is preferred for multi-dimensional data. Eventually, with the presence of edge computing systems, those data can be pre-processed locally for downstream applications. Generally, this review offers an overview of the development of intelligent wearable HMIs with edge computing capabilities and self-sustainability, which can greatly enhance the user experience in healthcare, industrial productivity, education, etc.

1. Introduction

Currently, the burgeoning development of the micro-nano fabrication process and of soft material facilitates the miniaturization of sensors, microprocessors, power supply units, and wireless transmission units, which form the foundations of modern wearable systems [1,2,3,4]. Compared with the past decades, the spread of wearable systems and the internet of things (IoTs) has drastically increased the volume of data communication via massively deployed devices [5,6]. Cloud computing is seamlessly integrated into the aforementioned systems to help to process the data. However, due to the rapid growth of the users and the diversification of multi-functional devices, the networks frequently experience a heavy burden caused by redundant data transmissions [7,8,9]. On the other hand, edge computing, which can process the raw data immediately within the device and only sends out the necessary data during external communication, can be a promising solution for wearable systems, featuring low latency, local data processing and better privacy protection. Furthermore, the high mobility of humans urgently requires the assistance of edge computing [10,11]. Meanwhile, the development of a desired edge computing system relies on the cooperation of those individual components which are indicated above [12,13].

For edge computing wearable systems, power consumption control is crucial for extending the working time [14], especially when the system integration level continues to increase. One power-consuming component is the sensor, which is required to capture a multimodal signal (e.g., kinematic, tactile, physiological, etc.) to perform complex tasks [15,16,17]. Common sensors employed in wearable systems include inertial, piezoresistive, capacitive, piezoelectric, and triboelectric, etc. [18,19,20]. Among these sensors, self-powered sensors, such as triboelectric and piezoelectric sensors [21,22], are gaining much interest because their self-sustaining feature can extend the working time of edge computing wearable systems. In addition to self-powered sensors, the study of wearable energy harvesters is also drawing increasing attention [23,24,25,26]. Diverse energies offered by the human body ensure the feasibility of realizing self-sustainable wearable edge computing systems [27,28,29,30]. Moreover, wireless transmission modules usually consume a considerable amount of energy. The solutions of conducting self-powered or low-power wireless transmission are also critical to further boost the operation time.

Powered by edge computing technology, real-time and local data processing decreases the system latency, which is essential for applications like medical monitoring, virtual/augmented reality, etc. Feedback components also benefit from the low processing latency because real-time haptic feedback can significantly enhance the engagement of users, and hence, to achieve higher efficiency and immersive experience [31,32,33,34]. A number of strategies are proposed to replicate real stimuli to human body [35], such as vibration, wire actuators, pneumatic actuators, dielectric elastomer actuators, as well as electroresistive- or thermoelectric-based temperature feedback units [36,37]. With the aid of edge computing capability, the fidelity of the response can also be improved, powered by locally deployed neural networks. The intelligence of the wearable system with edge computing capability is showing tremendous growth [38,39]. Furthermore, since most personal and physiological data are processed locally, the risk of the exposure of sensitive information is minimized, leading to better privacy protection.

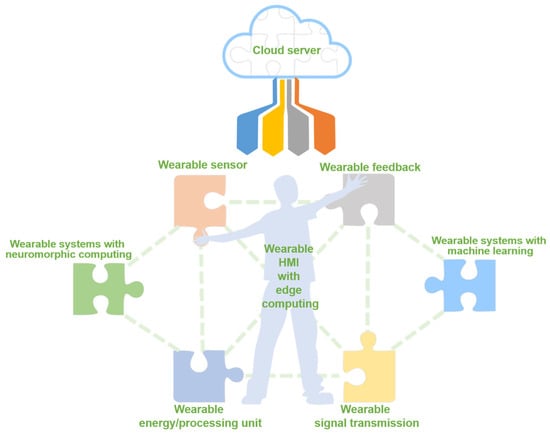

In this review, the typical components of the wearable system are discussed, as shown in Figure 1. Section 2 serves as the baseline of further discussion, where conventional and commercial-ready wearable technologies are introduced. Section 3 describes basic sensing and energy harvesting mechanisms, laying the foundation for self-sustaining edge computing systems. In Section 4 and Section 5, wearable sensing and feedback technologies are introduced. Considering the power consumption issue in wearable edge computing systems, state-of-the-art energy harvesting and self-powered wireless transmission technologies are reviewed in Section 6. Furthermore, ML-assisted advanced data analysis for the wearable system is addressed in Section 7. The development of the edge computing paradigm is introduced in Section 8, highlighting neuromorphic computing technology. Finally, conclusions and perspectives are given, focusing on several key hurdles of wearable edge computing systems.

Figure 1.

Overview of the fundamental components of a wearable human–machine interface (HMI) with edge computing.

2. Commercial-Ready Wearable Sensing Systems

2.1. Vision-Based Wearable Sensing Systems

Thanks to the thriving development of computer vision technologies in recent decades, vision-based wearable sensing systems for human–machine interaction are developing rapidly. For instance, researchers have reported numerous wearable systems [40,41,42,43] to perform motion capture (i.e., to estimate the full-body pose), emotion recognition [44,45,46,47,48,49], facial movement sensing [50,51,52,53,54], etc. Furthermore, hand gesture recognition or even sign language translation is achieved by systems powered by leap motion [55] or AR glasses [56]. Tracking a 3D hand pose is also feasible with wearable devices [57,58]. In addition to hands, the recognition of mouth movement can also facilitate many mobile computing applications. For instance, a smart necklace [59] that can recognize bilingual (English and Chinese) silent speech commands has been presented. Moreover, a complex 3D video conference system [60] can be implemented by Microsoft Azure Kinect cameras, shedding light on the potential of vision-based wearable sensing.

However, there are still two major concerns relating to vision-based sensing. On one hand, in order to capture the complete information of the users, cameras must traditionally be fixed at certain locations and occlusions should be avoided whenever possible. The aforementioned conditions constrain the scenarios where vision-based sensing can apply—typically an indoor, uncrowded environment is preferred. On the other hand, vision-based sensing must take photos of users and store data for analysis, causing potential privacy problems.

One major application of vision-based wearable sensing is full-body pose estimation. A mature commercial motion capture system for full-body pose estimation usually takes an “outside-in” method [61], which means cameras are placed externally and capture the subject (i.e., the user), such as Vicon [62], OptiTrack [63], etc. This type of setting limits the application scenarios: an indoor environment with minimal occlusion and controlled lighting is preferred. To enable outdoor full-body pose estimation, Shiratori et al. [61] implemented a portable motion capture system via the “inside-out” method. In the “inside-out” approach, cameras are mounted on the user and capture the environment. This system, however, requires a static background to estimate the pose and suffers from privacy problems.

EgoCap [40] addressed most of the aforementioned problem with an “inside-in” approach. In this system, a stereo pair of fisheye cameras are attached to a cycling helmet or a head-mounted display (HMD). Thanks to the large field of view (FOV) of the cameras, they can capture the full body of the user. The local skeleton pose is estimated by solving an optimization problem, where the alignment of a projected 3D human model with the human in left and right fisheye views is maximized at each time step. The estimation error is reported to be 7 cm in challenging scenarios. Incorporating machine learning algorithms, EgoCap can estimate the user’s pose even with some severe self-occlusions in the image. However, the two cameras and the wooden rig attached to the helmet/HMD still constrain the movement of the head and makes it difficult to put on the device as well. Additionally, due to the large FOV of the pair of cameras, the problem of privacy is mitigated but not solved.

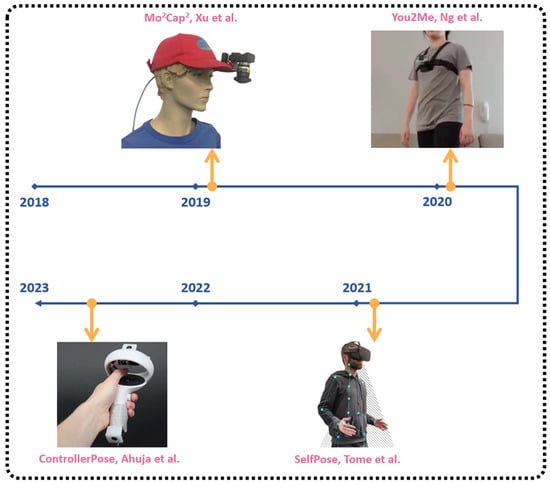

To further improve comfort while wearing, Mo2Cap2 [41], a more lightweight system than EgoCap, has been proposed (Figure 2). This system achieved full-body pose estimation with only one fisheye camera mounted on the brim of a baseball cap. The 3D joint position is estimated by a 2D joint location heatmap and the distance between the camera and each joint. Specifically, their method makes a more accurate estimation on lower body joints with a zoomed-in image only focusing on the lower body. The estimation error is 6.14 cm for indoor scenarios and 8.06 cm for outdoor environment.

Later, Tome et al. [42] presented SelfPose (Figure 2), which produces even higher joint position estimation accuracy than Mo2Cap2 [41]. The downward-looking camera is installed on the rim of a virtual reality (VR) HMD, adding a small amount of extra weight to the user. To compute the 3D full-body pose, a 2D pose detector is used to predict the heatmap of 2D joint positions, followed by a multi-branch autoencoder to generate 3D joint positions and other auxiliary outputs required in the training phase. The average joint position error is 4.66 cm in an indoor environment and 5.46 cm in an outdoor environment.

Cameras mounted around the head of the user translate into extra moment when the head moves so the user may feel uncomfortable wearing the device for a long time. Thus, some researchers seek to install the camera to other body parts, or even externally, while still obtaining an egocentric view. For instance, Hwang et al. [64] reported a full-body pose estimation system with a single ultra-wide fisheye camera mounted on the chest of the user. The average joint position error is 8.49 cm, slightly larger than that of [40,41,42], with no extra weight added to the head. Moreover, Lim et al. implemented BodyTrak [65] to capture a full-body pose by installing four miniature RGB cameras on a wristband. Employing a four-branch CNN with late fusion, the system estimates the 3D joint position with an average error of 6.34 cm (6.9 cm if using only one camera). Cameras installed on the body of the user inevitably add some extra difficulty to the movement of the user. To address this problem, Ahuja et al. presented ControllerPose [66] with two fisheye cameras mounted on each of two VR controllers (Figure 2). The system fuses the results from 2D joint position estimations and the IMU data from HMD and two controllers to compute the 3D joint positions. As the cameras are not mounted onto the user, the average position error is reported to be 8.59 cm, slightly larger than previous methods.

The previously mentioned “inside-in” method usually requires cameras with an ultra-wide FOV to capture the user. Ng et al. [43] (Figure 2) proposed a full-body pose estimation system with normal forward-looking cameras when the user is interacting with another person (i.e., the interactee). Their system exploits the pose of the interactee, believing it is inherently related to the pose of the user. The system combines the information from the homography, the static scene features and the 2D pose of the interactee and feeds them into a long short-term memory (LSTM) network to compute the 3D pose of the user. The average errors in joint positions are 14.3 cm and 8.6 cm when compared with the ground truths produced by Microsoft Kinect V2 and Panoptic Studio [67], respectively. A comparison between these full-body pose estimation wearable systems is demonstrated in Table 1.

Figure 2.

Vision-based wearable systems for full-body pose estimation. Reproduced with permission [41,42,43,66]. Copyright 2019, IEEE. Copyright 2020, IEEE. Copyright 2020, CVF. Copyright 2022, Association for Computing Machinery.

Table 1.

Comparison of vision-based wearable systems for body pose estimation.

Table 1.

Comparison of vision-based wearable systems for body pose estimation.

| Year | Ref. | Sensors | Sensor Location | Methods | Error Mean ± Std. (cm) | Power Consumption | Keypoint No. | FPS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | [40] | Two fisheye cameras | Helmet or HMD | Three-dimensional generative pose estimation | 7.00 ± 1.00 | ~5 w | 17 | 10–15 |

| 2019 | [41] | One fisheye camera | Baseball cap | Two-dimensional pose estimation + joint depth estimation | 6.14 (indoor) 8.06 (outdoor) | ~2 w | 16 | N.A. |

| 2020 | [43] | One camera (GoPro) | Chest | Homography + two-dimensional pose estimation with LSTM | 14.3 | ~3.5 w | 25 | N.A. |

| 2020 | [42] | One fisheye camera | VR HMD | Two-dimensional pose detection + two-dimensional-to-three-dimensional mapping | 4.66 (indoor) 5.46 (outdoor) | ~3 w | 16 | N.A. |

| 2020 | [64] | One fisheye camera | Chest | Two-dimensional joint heat map + three-dimensional joint position | 8.49 | ~2 w | 15 | N.A. |

| 2022 | [66] | Four fisheye cameras | VR controllers | Two-dimensional pose estimation + three-dimensional joint angle regression | 8.59 ± 5.20 | ~6.5 w | 17 | 7.2 |

| 2022 | [65] | Four cameras | Wrist | Four-branch CNN with late fusion | 6.34 | ~1.5 w | 14 | <5 |

Facial movement sensing is another popular research field for vision-based wearables. There are generally two different research categories here: the first is emotion recognition, which falls into a classification problem based on the facial movement of the user; the second is facial movement reconstruction, which seeks to track the face of the user and is also more challenging.

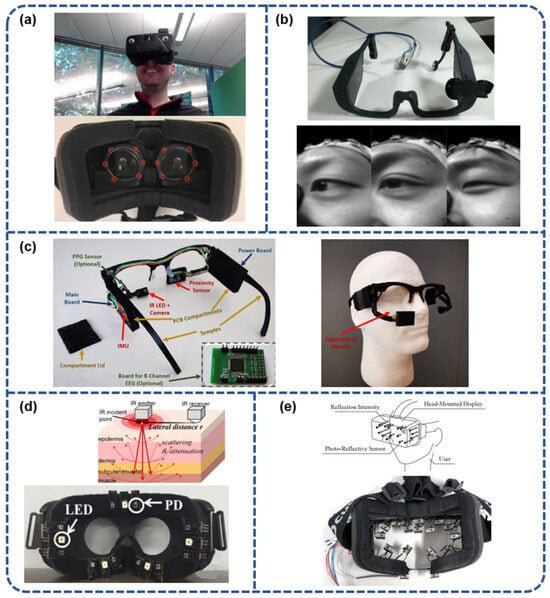

When wearing a VR headset, the user’s eyes are blocked, making it difficult for others to recognize the user’s emotion. This can interfere with the normal social engagement of the user and undermine the experience of using a VR device. To tackle this problem, Hickson et al. proposed Eyemotion [44] (Figure 3a), a system that can recognize the emotion of the user employing IR gaze-tracking cameras integrated in the VR HMD. The system classifies the emotion of the user with a CNN combined with a personalization method, where the raw image of each user is subtracted by the mean image of the user in neutral emotion before it is fed into the network. The system achieves a mean accuracy of 0.74 over five different categories of emotion. Note that the emotion recognition is not performed in real time. Later, Wu et al. [45] presented a wearable system which can classify the emotion of the user in real time. Moreover, all of the computation is undertaken in their embedded system. In their system, an image of the right eye of the user is fed into a CNN-based feature extractor, followed by a personalized classifier for emotion recognition.

Figure 3.

Vision-based wearable devices for facial movement sensing. (a) A VR goggle-based HMI for classifying facial expressions. Reproduced with permission [44]. Copyright 2019, IEEE. (b) A glass-type wearable device achieving emotion recognition via multimodal sensors. Reproduced with permission [46]. Copyright 2021, IEEE. (c) A lightweight, wireless, and low-cost glasses-based wearable platform for emotion sensing and bio-signal acquisition. Reproduced with permission [47]. Copyright 2020, IEEE. (d) A facial expression tracking device based on infrared sensors. Reproduced with permission [50]. Copyright 2016, IEEE. (e) A facial expression tracking head mounted display via photo-reflective sensors. Reproduced with permission [51]. Copyright 2017, IEEE.

Glass-type wearable devices can also be a suitable solution for emotion recognition. For instance, Kwon et al. proposed a glass-type HMI that can perform continuous emotion recognition by multimodal sensors [46] (Figure 3b). Furthermore, Yan et al. [47,49] reported a glass-type HMI with edge computing ability. A lithium battery and a Raspberry Pi are seamlessly fused into the glasses. The system adopts a CNN with regional attention blocks to classify the emotion of the user based on an image focusing on one side of the face. Nie et al. [48] (Figure 3c) also proposed an emotion recognition system built on eyewear. The system employs a CNN to capture the landmarks of the eye and the eyebrow of the user based on the image from an infrared (IR) camera. Then, these landmarks and the movement of the eyebrow detected by an optical-flow-based algorithm are combined to serve as the input to a decision tree, which classifies the emotion of the user. The average accuracy over five different categories of emotion is 0.84. Combined with a proximity sensor and an IMU, the system is capable of detecting the affective state and performing mental health monitoring. However, the computation is not performed in the embedded system only and their emotion classification is undertaken in semi-real time.

With respect to the problem of facial movement tracking, Cha et al. [50] proposed a facial expression tracking system based on infrared sensors (Figure 3d). The system is integrated into a head-mounted display. In addition, Suzuki et al. [51] reported another HMD-based HMI which can not only track facial expressions but also map them onto avatars (Figure 3e). The application of these two works, however, is constrained by the relatively low spatial resolution of the facial tracking. To this end, Thies et al. [52] presented FaceVR, a wearable system that can construct the face with high resolution in real time. The system uses an infrared camera installed in the VR HMD to capture the eye movement of the user and the eye tracking is performed by a classification approach based on random ferns. Note that to track the whole facial expressions, an externally located RGB-D camera is used so the system is not fully portable.

To track the facial movement, wearing a VR headset is not an ideal solution, as the user’s face is blocked. To achieve facial movement reconstruction without an HMD, Chen et al. proposed C-Face [53] and NeckFace [54], which are able to estimate the feature points on the whole face with cameras installed in earphones/headphones and a necklace/neckband, respectively. The key insight in C-Face and NeckFace is that they exploit the correlation between the contours of the face (also the chin in NeckFace) and the movement of the whole face. In other words, they use deep neural networks to infer the facial movement from the subtle changes in the contours of the face. Moreover, as only the contours of the face are captured, the privacy concerns are mitigated in these systems.

2.2. Non-Vision-Based Commercial-Ready Wearable Sensing Systems

Despite the facile fabrication and satisfying performance of visual sensory wearable systems, the concerns of privacy leakage triggered by these devices are a constant concern for users. Other commercial-ready sensors, such as inertial measurement units (IMUs), are employed as alternatives to visual sensors. The motion information captured by IMUs is less sensitive yet still sufficient to extract key features for downstream tasks. Nowadays, sensing based on IMUs is ubiquitous in daily life: inertial sensors (e.g., accelerometer, gyroscope, magnetometers, etc.) can be found in smartphones, smart watches, wristbands, earphones, etc. The prevalence of IMUs facilitates various fundamental applications, including human–machine interfaces [68,69], sign language translation [70,71,72], sports training [73] and rehabilitation [74]. From the perspective of cost, however, the IMU is relatively expensive and not an ideal choice to form a body area network (BAN). Some low-cost wearable sensing systems based on other commercial-ready sensory technologies are also reported [75].

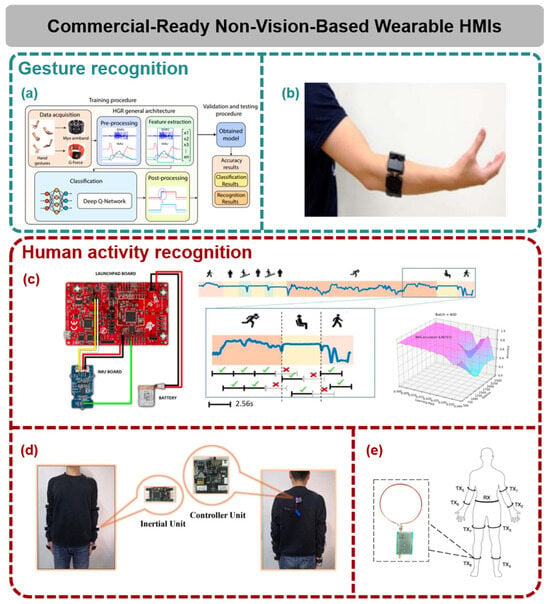

One of the popular research topics in IMU-based wearable sensing is hand gesture recognition. Fang et al. [68] proposed a glove equipped with 18 inertial and magnetic measurement units (IMMUs) to perform motion capture and hand gesture recognition. The data are collected by a microcontroller unit (MCU) and transmitted via a Bluetooth module. An extreme learning machine (ELM) [76] is trained to do the gesture classification, reporting the classification accuracies to be 89.6% and 82.5% for static gestures and dynamic gestures, respectively. Nevertheless, the system exhibits some limitations because of the large number of sensors and wires, making it difficult for the users to move their upper limbs freely. A hand gesture recognition system (Figure 4a) based on smart watches or armbands is introduced by Vásconez et al. [77]. Based on reinforcement learning algorithms, the system achieves good performance with online learning ability. Moreover, a gesture recognizing system based on the Myo armband for training sports referees (Figure 4b) is reported by Pan et al. [73]. The data are collected by an eight-channel surface electromyography sensor and an IMU. To classify the gestures, a cascaded framework is employed. In the first step, large motion gestures and subtle motion gestures are distinguished by a support vector machine (SVM) based on hand-crafted features; in the next step, another SVM based on hand-crafted features and features learned by a deep belief network (DBN) is used to finalize the classification results. The average classification accuracies over 11 participants is 92.2% and 90.2% for large and subtle motion gestures, respectively.

In addition to recognizing basic hand gestures, researchers also seek to recognize and even translate sign languages to help the hearing/speech-impaired people. Hou et al. reported SignSpeaker [70], a sign language translation system utilizing a commercialized smartwatch and a smartphone which runs a text-to-speech (TTS) program to read the translated sentence. The data generated from an accelerometer and a gyroscope are fed into a multi-layer LSTM to learn the semantic representations of sign languages, followed by a classification layer with a connectionist temporal classification (CTC) loss function. The CTC loss function helps to segment the sentence. The reported average word error rate (WER) is 1.04%.

SignSpeaker is based purely on inertial sensors, which are capable of capturing the motion of the hand but unable to recognize the subtle finger movement [78]. To deal with this limitation, Zhang et al. proposed WearSign [71], a multimodal wearable system fusing the signals from inertial sensors and electromyography (EMG) sensors to better track the motion of fingers. A CNN is deployed to exploit both intra-/inter-modality features. Then an encoder–decoder network performs end-to-end learning, outputting translated sentences directly. Thanks to the multimodal sensing ability and a data synthesis approach, the translation accuracy is greatly improved.

In addition to applications in gesture recognition, inertial sensors are also used in human activity recognition (HAR) [79,80,81]. HAR plays an important role in health care, rehabilitation and senior care [82,83,84]. For instance, Bianchi et al. [85] implemented a wearable system for long-term personalized HAR (Figure 4c). The system consists of an inertial sensor (MPU9250) and a controller unit (Cortex-M4), which can transmit the data through Wi-Fi. Combined with a convolutional neural network, the system can recognize nine different human activities with single IMU. In a relatively large dataset containing 15 subjects and 15,616 instances, an overall accuracy of 97% is achieved over 9 different activities.

Figure 4.

Commercial-ready non-vision based wearable HMIs. (a) A hand gesture recognition system based on inertial signals and reinforcement learning. Reproduced with permission [77]. Copyright 2022, MDPI. (b) A Myo armband-based gesture recognition system. Reproduced with permission [73]. Copyright 2022, IEEE. (c) A wearable system for long-term personalized human activity recognition (HAR). Reproduced with permission [85]. Copyright 2019, IEEE. (d) A wearable HAR system based on recurrent neural networks. Reproduced with permission [86]. Copyright 2022, IEEE. (e) A low-cost wearable HAR system based on magnetic induction signals. Reproduced with permission [75]. Copyright 2020, Springer Nature.

Apart from convolutional neural networks, recurrent neural networks are widely used in HAR applications because of their good performance for handling time-series data. Tong et al. [86] reported a wearable system integrated with six IMUs and a bidirectional-gated recurrent unit-inception (Bi-GRU-I) network (Figure 4d), which exhibits good performance on self-collected datasets and other public datasets. The system features a novel deep learning network, the Bi-GRU-I network, which is a combination of a recurrent neural network (RNN) and a convolutional network (CNN). The RNN part, a two-layer bidirectional GRU (Bi-GRU), is responsible for extracting temporal features from the data while the CNN part, three inception modules, is responsible for extracting spatial features. Because of this network structure, the classification performance is enhanced, resulting in an average accuracy of 97.76% in both self-collected and public datasets.

IMU-based wearable systems demonstrate good performance in HAR. Attaching IMUs around the whole human body, however, is often unfeasible due to the cost of IMUs. Therefore, to achieve a wireless body area network (WBAN) [87,88], a low-cost HAR solution is required. To this end, Golestani et al. [75] introduced a wearable HAR system based on magnetic induction signals (Figure 4e). The system encompasses a receiving coil as a belt around the waist of the user and eight transmitting coils fixed at both the upper and lower limbs of the user. When the user moves, the relative position and alignment of the coils change, and the coupling non-propagating magnetic fields created by the coils also change. By measuring the variations in induction signals, the relative movement of the limbs can be measured. Compared with conventional radiating magnetic fields, the non-propagating magnetic fields decay more quickly, and this feature reduces the interference and improves the privacy safety. The most notable advantage of the system lies in the low cost, because cheap coils replace the expensive IMUs. To classify the human activity, a recurrent neural network based on long short-term memory (LSTM) is implemented and an accuracy of 98.9% is reported for the Berkeley Multimodal Human Action Database (MHAD).

In summary, the commercial-ready solutions (vision-based or non-vision-based) for wearable HMI systems illustrate good performance, but power consumption remains a challenging issue, limiting the long-time usage of these devices. Furthermore, these large and rigid commercial-ready sensors make building a miniature-sized and conformal wearable HMI system impossible. Therefore, the development of highly integrated, self-sustaining and flexible HMI systems based on self-powered sensors or energy harvesting technologies is highly desired and investigated, and these will be introduced in the following section.

3. Wearable Sensing and Energy Harvesting Mechanisms

Owing to the features of conformable or intimate contact with human body, wearable systems have the advantages of the continuous and accurate detection of multi-modal information regarding motion status and health conditions [89,90] (Figure 5). Although the research into wearable systems has obtained great achievements in recent decades, devices with an increasing number of sensors and high-performance microprocessors also suffer from concerns around reduced battery power, as the size and the capacity of the battery need to be balanced for comfort. For edge computing devices in particular, to further extend the operation time of the wearable system, researchers have begun to develop energy harvesters against different energy sources from the human body, so that these harvesters can be integrated into the wearable systems to continuously supply power [91,92]. A performance comparison of different wearable energy harvesting mechanisms is demonstrated in Table 2. Interestingly, as the variations of the outputs from the harvesters are observed in response to the fluctuations of the energy sources, e.g., body motions, temperature changes, and sweating, etc., the energy harvesters can be further modified to detect those parameters with self-generated signals, and these are typically known as self-powered sensors [93]. Hence, the power consumption of the sensors can be reduced. Eventually, wearable sensory systems will migrate from the use of conventional sensors with a power supply to sensor fusion technology, in which some sensors are replaced by self-powered sensors.

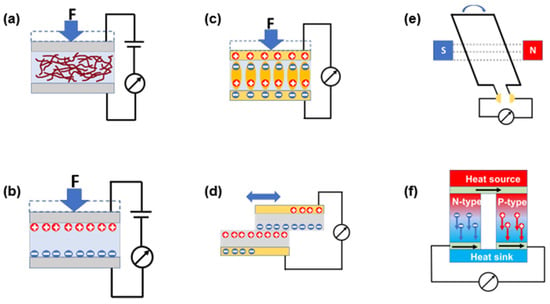

Figure 5.

Working mechanisms of common wearable sensors and energy harvesters. (a) Piezoresistive. (b) Capacitive. (c) Piezoelectric. (d) Triboelectric. (e) Electromagnetic. (f) Thermoelectric.

3.1. Sensors with Power Supply

For wearable HMIs, the mature sensing technologies available on the market are piezoresistive and capacitive sensors [94]. The piezoresistive effect converts the mechanical force or deformation into the variation of resistance via the changing of the carrier mobility or the conduction path. Piezoresistive sensors generally possess good sensitivity and working ranges, as well as simple readout circuits, but still show the weaknesses of hysteresis and temperature creep. While, for capacitive sensors, they determine the mechanical stimulus through the response of the capacitance, as the parameters of the dielectric layer between two electrodes can be altered. Capacitive sensors offer good sensitivity and frequency response, with no temperature influence. However, a signal-to-noise ratio issue is frequently encountered.

By leveraging the MEMS fabrication process, silicon-based piezoresistive or capacitive designs are studied for developing inertial sensors or micro tactile sensors with extreme high sensitivities and multi-directional sensing capabilities. Meanwhile, thin film and soft material techniques enable e-skin-like sensors for monitoring body motion and interactive events.

3.2. Sensors and Energy Harvesters with Self-Generated Signals

The daily activity of the human body is a natural mechanical energy source that contains energy ranging from a few watts to a few tens of watts corresponding to the different body parts. To retrieve these energies, a few mechanical energy harvesting mechanisms are utilized, including the piezoelectric effect [95,96,97], the triboelectric effect [98,99], and the electromagnetic effect [100,101]. The piezoelectric effect relies on the polarization of the dipole moment of the piezoelectric materials under applied force or deformation to collect electric charges [27]. However, materials with high piezoelectric coefficients are usually ceramic, which is less preferable for a wearable system. On the other hand, the triboelectric effect is defined as the charge transfer during the mechanical interaction of two surfaces with different electronegativities [102]. Unlike the limited piezoelectric materials, the wide choices of triboelectric material reveal its own superiority in developing wearable energy harvesters [103,104]. But the vulnerability of the output signal to environmental influences, such as humidity, electromagnetic interference, etc., is a major problem that needs to be concerned.

As mentioned earlier, the outputs from the piezoelectric and triboelectric effects all show a good correlation to the intensity of the mechanical stimulus. By the proper design of the sensory structure, both of the two effects can be applied to detect various motions, such as pressing, bending, walking, rotating, vibration, etc., without consuming power on the sensor itself [105,106].

In addition, the general performance of the piezoelectric (PENG)- and triboelectric (TENG)-based energy harvesters/nanogenerators at the current stage still lack enough output power within the limited space of the wearable system. Alternatively, electromagnetic energy harvesters with a much higher power density act as another popular option for powering a wearable edge computing system. Electromagnetic generators rely on Faraday’s law of electromagnetic induction. In wearable systems, electromagnetic generators typically consist of a movable magnet–coil pair, where relative motion (usually caused by body movements) between them produces an alternating current output. Compared with piezoelectric and triboelectric harvesters, electromagnetic generators generally deliver higher power density and efficiency. However, their integration in flexible and miniaturized platforms is restricted by the bulky magnetic and coil components and by a limited output under small-scale deformation.

In addition to mechanical energy, the human body can also be a good source of thermal and moisture-related energy that can be harvested through pyroelectric and moisture–electric mechanisms. The pyroelectric effect originates from materials possessing a spontaneous polarization that varies with temperature fluctuation (ΔT), thereby generating an electric current or voltage during thermal cycling [107]. When the temperature changes, the alteration of dipole alignment in the pyroelectric material leads to a net flow of charges across the electrodes. This mechanism has been further optimized through thermodynamic cycles such as the Olsen cycle to enhance conversion efficiency [108]. On the other hand, moisture electricity generators exploit gradients of humidity, potentially converting the Gibbs free energy change to electricity [109]. With asymmetric hydrophilicity, the asymmetrical distribution of mobile ions or protons establishes an internal electric field, generating a continuous current [110]. These two mechanisms serve a complementary role to the mechanical energy harvesters: temperature variations or breathing moisture can also contribute to energy generation. However, the two mechanisms also suffer from some challenges, such as low power density for pyroelectric generators and humidity gradient maintenance for moisture electricity generators.

3.3. Other Energy Harvesters

Except for mechanical energy, there are other types of energy sources which may be possible to be harvested [100,111]. The thermoelectric effect, which involves using the temperature difference between a heat source and a heat sink to generate electricity [112], is applied, as the human body has a relatively stable temperature of about 37 °C. Although the output power may not be sufficient, the operation time is more continuous than that of a mechanical energy harvester, meaning that the accumulated energy stored in the battery can still be acceptable [113].

Table 2.

Comparison of wearable energy harvesting mechanisms.

Table 2.

Comparison of wearable energy harvesting mechanisms.

| Power Density | Working Range | Operation Condition | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Triboelectric | 58.82 W/m2 | A few Hz | Power backpack for energy harvesting [114] |

| 107 mW/m2 | 0.5–3 Hz | Cardiac monitoring via implantable triboelectric nanogenerator [115] | |

| 0.52 mW/cm2 | 4 Hz | Skin-touch-actuated textile-based triboelectric nanogenerator with black phosphorus [116] | |

| Piezoelectric | 159.4 W/cm3 | 25 Hz | Piezoelectric energy harvester with frequency up-conversion [117] |

| 11 mW/cm3 | 0.33–3 Hz | Nanogenerator based on ZnO nanowire array [118] | |

| Electromagnetic | 730 μW/cm3 | 6 Hz | Human motion energy harvester [119] |

| 79.9 W/m2 | 2 Hz | Rotational pendulum-based electromagnetic/triboelectric hybrid generator for human motion applications [120] | |

| Thermoelectric | 1.2 mW cm−2 | 50 K temperature difference | Inorganic flexible thermoelectric power generator [121] |

4. Wearable Sensing Applications

Based on the sensing mechanisms mentioned in the previous section, a number of innovations in structure design and material developments have been brought into the research field of wearable sensing applications [122,123,124]. As a result, various sensors with their own superiorities (Table 3), such as high sensitivity, wide sensing range, fast response, low hysteresis, multi-modal sensing, low power consumption, etc., are presented frequently to help to explore every information from the human body in a more convenient manner [125,126]. For edge computing wearable systems, sensors with low power consumption (or even self-powered sensors) are especially beneficial, as the operation time of the devices can be greatly extended with such sensors.

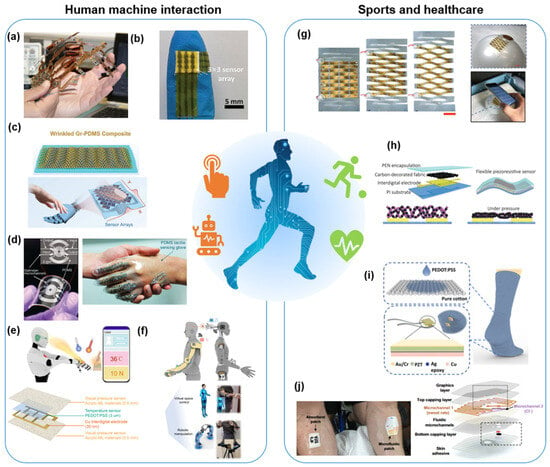

4.1. Sensors for Human–Machine Interaction

Inertial sensor-based HMIs are widely adopted in different commercial products. Those accelerometers and gyroscopes can accurately capture the orientation and the motional information. With the aid of additional algorithms, more information related to physical interactions can be detected. Meanwhile, these inertial sensors are usually integrated with other sensors for comprehensive sensing. In Figure 6a, the presented glove uses a combination of 20 bending sensors, 16 tri-axial accelerometers, and 11 force sensors on a flexible PCB to capture the hand motions without the requirement of calibration [127].

Recently, the development of a new material has introduced a new kind of flexible iontronic tactile sensor by utilizing a highly conductive polymer thin film decorated with microspheres (Figure 6b) [128]. This ultrasensitive tactile sensor can detect dynamic micromotions, such as touching sandpapers with different surface textures. By designing a smart glove with a sensor array, it successfully demonstrates fast and accurate Braille recognition.

For most tactile sensors, cross interference among different mechanical deformations is one of the main concerns. Several solutions are addressed to isolate the interferences, including reference sensors, strain relief structures, compensation units, etc. Based on wafer-scale stretchable graphene film and patterning techniques, a semitransparent stretchable TENG is prepared as self-powered tactile sensor array with a strain-insensitive characteristic, as depicted in Figure 6c [129]. An 8 × 8 stretchable tactile sensor array is fabricated to map the distribution and intensity of the applied pressure without the influence of strain. Moreover, the temperature fluctuation also affects the piezoresistive-based sensors, especially for liquid metal-based sensors [130]. To solve this problem, a microfluidic tactile sensor based on a diaphragm pressure sensor with an embedded Galinstan microchannel design is then reported (Figure 6d) [131]. With a design of four primary sets of sensing grids, including two tangential sensing grids and two radial sensing grids, the proposed sensor not only shows high sensitivity, linearity, low limit of detection, high resolution, etc., but also possesses temperature self-compensation at 20–50 °C by using an embedded equivalent Wheatstone bridge circuit. Similarly, an interference-free bimodal tactile sensor for pressure and temperature sensing is presented in Figure 6e. The variations of resistance and luminescence caused by the thermoresistive effect and the piezo/tribophotonic effect enable the sensing of pressure and temperature independently and without any crosstalk. It also allows the wireless transmission of pressure and temperature data via mobile phone [132]. These sensors, handling cross interference of different signals, pave the way for multimodal sensing on wearable edge computing devices. The powerful onboard processers can analyze the latent features of multimodal signals and perform complex downstream tasks (e.g., human activity recognition, emotion recognition, etc.) powered by neural networks.

By considering wearability, the abovementioned sensors are often designed on a flexible or stretchable substrate, and detect the information at a specific part [133]. To establish a whole-body sensory network, more platforms, such as exoskeleton, can be considered. In the meantime, the different body parts usually have their own motion patterns, which require different sensing mechanisms or designs. In Figure 6f, a triboelectric bi-directional (TBD) sensor, which can be universally applied on different parts of the customized exoskeleton for capturing the motions of the entire upper limbs is reported [134]. With a facile switch and a basic grating structure, it realizes bidirectional sensing for both rotational and linear motions, the single type of pulse-like signal greatly simplifies the back-end signal processing. The good consistency between the exoskeleton and the structure of the human body allows further kinetic analysis for other physical parameters, such as displacement, velocity, and force, etc. All the TBD sensors in the exoskeleton are self-powered, which greatly increases the possible operation time of the device.

4.2. Sensors for Healthcare and Sports Monitoring

Healthcare and sports-related monitoring are key reasons behind the popularity of wearable systems [135,136,137]. With the help of diversified wearable devices, such as wrist bands, watches, glasses, sleeves, and insoles, etc., the continuous monitoring of the body conditions is now becoming increasingly convenient [19,138,139]. Edge computing technology fits in the task of healthcare and sports monitoring, as the local processing of the data can decrease the system latency and achieve real-time monitoring and notification. To further boost the functionality and sustainability, more studies are required [140]. As shown in Figure 6g, an integrated stretchable device for continuous health monitoring is composed of a kirigami-based stretchable and self-powered sensing component, and a near-field communication (NFC) data transmission module. The as-fabricated devices can be mounted on different surfaces without mechanical irritation, and can hence measure the surface strain of a deforming balloon and pig heart. In terms of other types of energy harvester, a perspiration-powered electronic skin (PPES) that harvests energy from human sweat through lactate biofuel cells (BFCs) is developed [141], which can achieve the continuous self-powered health monitoring with both multiplexed sensing and wireless data transmission [142]. It shows a great capability for noninvasive metabolic monitoring and a human–machine interface of assistive robotic control.

Conventional heart rate and blood pressure monitoring of the wearable devices utilizes a photoplethysmogram (PPG) sensor that consists of an LED and a photo detector. Alternatively, this function can be performed by applying piezoresistive sensors [143,144]. A proposed device has a fast response when capturing the precise pulse waveform. Compared with PPG-based devices which consume 10–100 mW of power, this piezoresistive-based patch requires much lower power consumption of 3 nW (Figure 6h). Such ultralow power consumption directly benefits on board edge analytics, making continuous health monitoring possible.

Clothes are the important platforms for a wearable system. Various fabrication processes are utilized [145], including weaving, knitting, etc. The manner of functionalizing the fabric or textile can further improve the level of integration [146,147,148]. In Figure 6i, by using the conductive polymer coated cotton sock, a smart sock with walking pattern recognition and motion tracking functions based on the output of fabric-based TENG can be fabricated [149]. The multi-segmental pattern of the coating can even realize the gait analysis. The fusion of PZT chip-based PENGs with the TENG sock enables the qualitative detection of the variation of sweat levels due to the output response of TENG against the sweat absorbed by the sock. In terms of sweat analysis, a wearable microfluidic patch technology is introduced in Figure 6j [150]. The roll-to-roll processed microfluidic channels with hydrophobic materials can guide sweat via natural pressure associated with eccrine sweat excretion. The colorimetric sensors with a smartphone image processing platform can measure regional sweating rate and sweat.

Optical sensors have emerged as an alternative solution to health monitoring to avoid some drawbacks of electrical sensors [151]. Among these, optical fiber-based wearable sensing systems have gained strong interest [152]. A highly flexible and intelligent wearable device based on a wavy shaped polymer optical microfiber is reported in [153]. The device can perform cardiorespiratory and behavioral monitoring of the user. Powered by neural networks, voice-based word recognition is also achieved. Furthermore, optical sensors can also be used to perform sweat sensing, with analytical methods transducing chemical information into optical signals [154]. A skin-interfaced, wearable sensing system that can detect the concentrations of vitamin C, calcium, zinc and iron in sweat is introduced [155]. The sweat is collected and stored with passive microvalves, microchannels and microreservoirs. The concentration of the nutrients is determined by colorimetry.

In addition to physical sensors, electrochemical sensors also play an important role in wearable healthcare and sports monitoring. As a promising approach for non-invasive health monitoring, electrochemical sensor-based wearable sweat sensing systems have been intensively investigated [156,157,158,159,160]. For instance, a fully in-ear flexible wearable system, which can be attached to an earphone, is proposed [157]. With multimodal electrochemical and electrophysiological sensors, the device can monitor the lactate concentration via the ear’s exocrine sweat glands and the brain states via multiple electrophysiological signals. Apart from lactate, other important biomarkers can also be tracked by wearable systems. A fingertip biosensing system is introduced in [160]. The energy is generated by enzymatic biofuel cells, which are fueled by lactate, and is stored in AgCl-Zn batteries. With flexible and compact design, the device can monitor glucose, vitamin C, lactate and levodopa.

Figure 6.

Wearable sensing applications for human–machine interaction, sports and healthcare. (a) Data glove with inertial sensor integrated on flexible print circuit board. Reproduced with permission [127]. Copyright 2013, IEEE. (b) Flexible capacitive iontronic tactile sensor for ultrasensitive pressure detection. Reproduced with permission [128]. Copyright 2022, Wiley-VCH. (c) Strain-insensitive self-powered tactile sensor arrays based on a graphene elastomer. Reproduced with permission [129]. Copyright 2022, Wiley-VCH. (d) Wearable microfluidic pressure sensor. Reproduced with permission [131]. Copyright 2017, Wiley-VCH. (e) Bimodal tactile sensor with tactile and temperature sensing information. Reproduced with permission [132]. Copyright 2022, American Chemical Society. (f) Exoskeleton manipulator using bidirectional triboelectric sensors. Reproduced with permission [134]. Copyright 2021, Springer Nature. (g) Stretchable piezoelectric sensing systems for health monitoring. Reproduced with permission [142]. Copyright 2019, Wiley-VCH. (h) Piezoresistive sensor patch enabling ultralow power cuffless blood pressure measurement. Reproduced with permission [144]. Copyright 2016, Wiley-VCH. (i) Smart sock using piezoelectric and triboelectric hybrid mechanism for healthcare. Reproduced with permission [149]. Copyright 2019, American Chemical Society. (j) Skin-interfaced microfluidic system with personalized sweat analytics. Reproduced with permission [150]. Copyright 2020, American Association for the Advancement of Science.

Table 3.

Comparison of performances among different sensing mechanisms.

Table 3.

Comparison of performances among different sensing mechanisms.

| Materials | Sensitivity | Sensing Range | Response Time | Application | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Piezoresistive | Liquid metal | 0.0835 kPa−1 | 100 Pa–50 kPa | 90 ms | Tactile, bending, and pulse sensor | [131] |

| Carbon | −1.10 kPa−1 | <21 kPa | 29 ms | Tactile sensor array | [161] | |

| Silicon | 10.3 kPa−1 | 0.37–5.9 kPa | 200 ms | Pressure sensors | [162] | |

| Capacitive | Elastomer | 0.55 kPa−1 | <15 kPa | Pressure sensor array | [163] | |

| Air gap | 0.068 fF/mN | <1.7 N | 200 ms | Tactile sensor | [164] | |

| Ionic solution | 29.8 nF/N | <4.2 N | 12 ms | Three-dimensional force sensor | [165] | |

| Triboelectric | Polymer | 2.82 V MPa−1 | 0.3–612.5 kPa | 40 ms | Tactile sensor array | [166] |

| Elastomer | 0.013 kPa−1 | 1.3–70 kPa | Tactile sensor | [167] | ||

| Fabric | 10–160% | Smart clothes | [168] | |||

| Piezoelectric | PVDF | 0.21 V kPa−1 | <1 kPa | 20–40 ms | Mimic somatic cutaneous sensor | [169] |

| PZT | 0.018 kPa−1 | 1–30 kPa | 60 ms | Pulse monitoring | [170] | |

| BaTiO3 | 37.1–257.9 mV N−1 | 5–60 N | Detecting air pressure and human vital signs | [171] |

5. Wearable Feedback Systems

In the real world, the interactive events of humans rely heavily on the perception of the receptors in the skin and the muscle spindles [172]. As a result, the applied forces, the textures, the temperature, etc., can be perceived for better recognition and manipulation (Table 4). Although many current HMIs are equipped only with different sensing units, the existence of feedback components may greatly enrich the awareness of the interactive scene, especially for wearable systems [173,174]. In terms of controlling the robot or virtual character, the comprehensive feedback functions replicate a more realistic sensation compared with pure vision-based monitoring, in order to make a better adjustment [175]. For rehabilitation purposes, the feedback system can act not only as an assistive tool to increase the physical power of the patients, but can also be applied as a stimulator or massager to facilitate the recovery process.

Table 4.

Advantages and disadvantages of different feedback techniques.

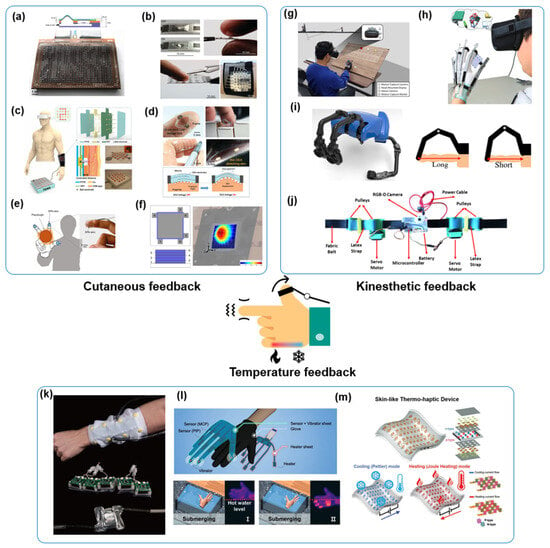

5.1. Cutaneous Feedback

Human skin can sense the shape, texture, and softness of the touched object via mechanoreceptors and can also differentiate vibration and static pressing through fast adapting (FA) and slow adapting (SA) receptors, respectively. Additionally, temperature sensors in our skin can provide even more complex sensations. However, the densities of those receptors are varied throughout the human body.

Except for the frequently used vibrators, pneumatic actuation is one of the most popular feedback techniques. To minimize the number of air inlets and pathways, several switch array techniques are studied to increase the controllable air chambers. A reconfigurable pneumatic haptic array controlled by shape memory polymer (SMP) membrane is shown in Figure 7a [176]. The Young’s modulus of the membrane can be changed by the heater, so that the membrane deforms under varied air pressure to realize the reconfigurable tactile system. As the applied voltages with different potentials created on two electrodes can cause the attraction phenomenon, the electrostatic force-based feedback is also studied. To improve the feedback force, the electrostatic actuator can be hydraulically amplified, as illustrated in Figure 7b [177]. Here, the outer region of the chamber was compressed under electrostatic force, and the central membrane was then expanded under hydraulic pressure. Noticeably, electrical discharge can also be considered a kind of feedback, and TENGs with an output voltage from triboelectrification are thus utilized for discharge feedback, as shown in Figure 7c [178]. The direct contact of the ball electrodes to human skin can lead the TENG discharge to be delivered as electrical discharge feedback.

Another issue regarding the use of cutaneous feedback is the question of how to accurately reconstruct spatial or textural stimuli to the mechanoreceptors in order to perceive the recreated 3D shapes in a single system. Dielectric elastomers can provide mechanical deformation under the applied voltage. To fabricate the actuator with tunable feedback perception, a multi-layer PDMS-based dielectric elastomer actuator (DEA) sandwiched by carbon nanotube electrodes for fingertip cutaneous feedback is demonstrated in Figure 7d [179]. The surface area of the as-fabricated DEA can be modified to cause a feeling of stretching or compression on the skin. Moving forward, a soft pneumatic actuator skin (SPA–skin) is presented as a low-profile soft interface containing a PZT sensor layer, an SPA layer, and a controller with pneumatic system (Figure 7e) [180]. Owing to the integration of the sensing and feedback layer, the local environmental loading conditions can be acquired for tuning the output in coherent feedback, so that the natural texture of an orange peel can be recreated. The high-bandwidth capabilities of feedback enable two-stage actuations, including low-frequency stimulation when approaching the contour shape, and high-frequency vibration when reaching the actual contour of the object.

To further explore the piezoelectric actuator with the flexible and lightweight substrate, while maintaining the amplitude of actuation, the low-cost mass printing approach was reported for large area multilayer piezoelectric actuators with strong haptic sensations. In Figure 7f, the proposed device shows an extremely high deflection, and generates a blocking force of 0.6 N, which is sufficient to generate an indentation on the human skin [181]. This can also be incorporated with audible sound information based on its high sound pressure level, so that a fusion of touch and sound sensation is realized.

5.2. Kinesthetic Feedback

The perception of the kinesthetic feedback is undertaken through the neurosensory pathways of the muscle spindles, to feel the movement or position of body parts. Because of its 3D features, the reconstruction of the motion that is mimicking the pathway becomes a grant challenge.

Tendon-driven actuation is commonly utilized in kinesthetic feedback, as well as in delivering physical assistance to impaired people. With well-designed wire routines and a miniaturized motor, the tendon-driven actuator can offer strong kinesthetic feedback force by a compact package. In Figure 7g, a wearable tendon-driven haptic device is demonstrated to provide multiple kinesthetic feedback in a small form factor for the stiffness rendering of virtual objects [182]. The tendon-locking unit modifies the stiffness of the tendon using a selective locking mechanism based on either a rigid mode or an elastic mode. Additionally, the tension transmission component can transfer the resistive force from the locking unit to finger through the tendon. Interestingly, the previously mentioned electrostatic force can also be applied for offering the blocking force as well. In Figure 7h, a high force density electrostatic clutch is proposed for developing the kinesthetic feedback glove to reflect the virtual events [183]. A conductive textile with a high friction insulation layer forms a clutch that can generate a frictional shear stress of up to 21 N/cm2 at 300 V to initiate the blocking action. To further quantify the feedback performance, a wearable hand system can measure the motional information of each finger during the interaction for recording and evaluating the effectiveness of the kinesthetic feedback, as shown in Figure 7i [184].

In addition, several researchers are also studying the delivery of feedback to other body parts to further improve the experience. A jacket with contraction and extension actuators can be pneumatically actuated to enable kinesthetic motions of the arms [185]. In addition, a wearable haptic guidance system has been developed to help those visually impaired people to navigate a running track (Figure 7j) [186]. With an RGB-D camera and a microprocessor to detect the lanes and calculate the steering angles, the skin can be stretched by a belt via the steering angles for generating the navigation-related haptic feedback sensation around the waist.

5.3. Temperature Feedback

Temperature sensation is an extremely important function of skin, which can help to protect ourselves from the potential hazards. Meanwhile, for human–machine interactions, temperature feedback allows a better perception of the working environment via a replicated immersive feeling. Moreover, it also assists medical rehabilitation via specific stimulations.

Most of the time, temperature and mechanical stimuli are exerted on skin simultaneously during the interaction in real space. Multi-modal feedback is drawing much attention. As depicted in Figure 7k, a sleeve-type soft haptic device is presented with the capabilities of reproducing the feeling of a moving thermal sensation along with pressure stimulation using a single method [187]. The pneumatic and hydraulic systems generate pressure and temperature stimuli, respectively. A microblower in a small sphygmomanometer eliminates the requirement of a large air compressor or complicated tubes. The electroresistive heater is another main technical direction. A multi-modal sensing and feedback glove is developed as illustrated in Figure 7l [188]. The liquid metal is printed into a meandered shape to offer both strain sensing and thermal feedback functions via the power supply.

On the other hand, the electroresistive based units can only act as heaters to give thermal feedback. A wearable ear hook with a Peltier module can provide both hot and cold stimuli on the auricular skin area [189]. By adding multiple Peltier modules, the multi-point auricular thermal patterns can be perceived by the users with an average accuracy of 85.3%. Although the thermoelectric module with the Peltier effect possesses both heating and cooling capabilities, the solution of developing flexibility or even stretchability is still an issue that needs consideration. In Figure 7m, a skin-like thermo-haptic device with thermoelectric units shows a certain flexibility, with a design incorporating Cu serpentine electrodes as interconnectors and thermoelectric-based pellets. This device can create a temperature difference of 15 °C via the heating and cooling process [190].

Figure 7.

Wearable feedback systems for cutaneous feedback, kinesthetic feedback, and temperature feedback. (a) Large reconfigurable arrays with shape memory feedback units. Reproduced with permission [176]. Copyright 2017, Wiley-VCH. (b) Hydraulically amplified electrostatic actuators for multi-modal feedback. Reproduced with permission [177]. Copyright 2020, Wiley-VCH. (c) Self-powered electro-tactile system for virtual reality. Reproduced with permission [178]. Copyright 2021, American Association for the Advancement of Science. (d) Feel-through feedback unit using a dielectric elastomer actuator. Reproduced with permission [179]. Copyright 2021, Wiley-VCH. (e) Finger touch sensation with soft pneumatic actuator. Reproduced with permission [180]. Copyright 2021, Wiley-VCH. (f) Printed multilayer piezoelectric actuators on paper for touch and sound sensation. Reproduced with permission [181]. Copyright 2022, MDPI. (g) Wearable haptic device for the stiffness rendering of virtual objects. Reproduced with permission [182]. Copyright 2021, MDPI. (h) Textile electrostatic clutch for virtual reality. Reproduced with permission [183]. Copyright 2020, Wiley-VCH. (i) Kinesthetic feedback evaluation system for virtual reality. Reproduced with permission [184]. Copyright 2019, IEEE. (j) Haptic guidance system based on skin stretch around the waist. Reproduced with permission [186]. Copyright 2022, IEEE. (k) Wearable temperature feedback device with fluidic thermal stimulation. Reproduced with permission [187]. Copyright 2021, Association for Computing Machinery. (l) Liquid metal-based multimodal sensor and haptic feedback glove for thermal and tactile sensation. Reproduced with permission [188]. Copyright 2021, Wiley-VCH. (m) Stretchable cooling/heating feedback device for artificial thermal sensation. Reproduced with permission [190]. Copyright 2020, Wiley-VCH.

6. Wireless Power and Signal Transmission and Energy Harvesting

Due to the concern of portability, the size and weight of the energy storage unit are strictly restrained to maintain comfortability. An increasing number of integrated modules further reduces the operation time of the wearable system, though the power density of the battery also increases (Table 5). This situation will become worse when the edge computing capability is introduced, as the computation in the wearable microprocessor will consume much more power. The manner of scavenging the energy from the human body or ambient environment can extend the operation time, or even enable self-sustainability.

Table 5.

Comparison of the typical power consumptions of common components in wearable systems.

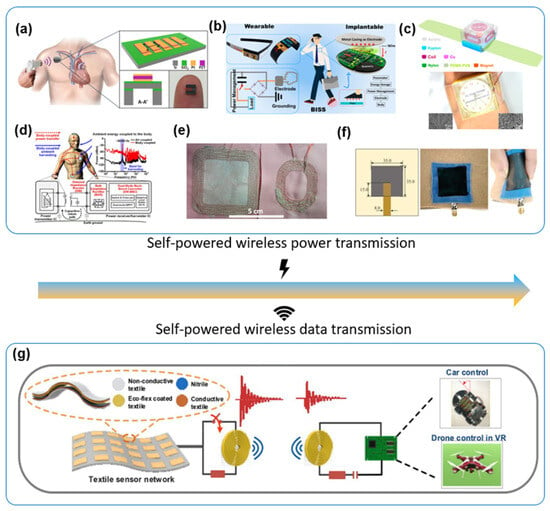

Piezoelectric materials have a relatively high power density and small size based on MEMS fabrication process. Hence, PENG devices are frequently reported for wearable and implantable applications. A broadband ultrasonic PENG (Figure 8a) is demonstrated to power implantable biomedical devices via an input ultrasound probe, while maintaining the broadband frequency response from 250 to 240 kHz [191]. However, those ceramic PENGs are not suitable to make large-size flexible energy harvesters, and the general output power is thus still limited. TENG, with many more material options and design feasibilities, is another potential technique. In Figure 8b, a body-integrated self-powered system (BISS) is then developed to scavenge energy from human motions, through triboelectrification between soles and floor and electrification of the human body [192]. With a piece of an electrode attached to the skin, the human body, as a good conductor, can deliver the power into the other wearable system, such as smart glasses. However, many TENGs still suffer the power density issue. As a complementary solution, a fusion approach with both TENG and EMG mechanisms is utilized to make a self-powered electronic watch (Figure 8c) [193]. The EMG part consists of the magnetic ball with embedded coils which can generate 2.8–4.0 mW power. The arch-shaped TENG made by nylon and PDMS can provide 0.1 mW power. On the other hand, the power transmission throughout the whole body is also preferred, so that the energy harvesters can be separately placed onto the position with rich mechanical energy.

Interestingly, humans are now living in an environment that is full of electromagnetic (EM) waves. To convert those EM waves into electricity, human body-coupled power delivery and ambient energy harvesting chips are proposed with the capability of harvesting ambient EM waves and delivering their power via body medium for full-body power sustainability [194] (Figure 8d). Moreover, the applications of new materials in fabricating smart textiles or e-skin are further increasing the solutions of wireless wearable energy harvesters or transmitters (Figure 8e,f) [195,196].

Wireless signal transmission is one of the most important foundations for a wearable edge computing system. According to the required transmitting range, speed, and data volume, various wireless communication protocols, such as WiFi, Bluetooth, ZigBee, XBee, etc., are adopted in the commercial market. As a major power-consuming unit, many of the wireless units developed strategies to save energy, such as sleep mode, event-based trigger, etc. Together with the wearable energy harvester, the sustainability of the whole system can be improved. In addition, attempts to use a self-powered output as a data transmission signal are also presented.

In order to monitor vital signals in real time, a wearable system includes MXene-enhanced TENGs, pressure sensors, and multifunctional circuitry. The outstanding conductivity and mechanical flexibility of MXene enable conformable energy harvesting the pressure sensing with a low detection limit of ~9 Pa, and a fast response time of ~80 ms [197]. The whole wearable monitoring system is powered by the TENG in order to continuously measure the peaks of the radial artery pulse from the wrist in real time. The capacitance-to-digital converter chip communicates with pressure sensors and LEDs to visualize the valleys and peaks of the output waveforms with the “on” and “off” states, respectively.

By rectifying and converting electric power from the magneto-mechano-triboelectric generator (MMTEG), a self-powered wireless indoor positioning system is proposed with continuous monitoring [198]. The device consists of a magnetic field harvester, power control circuit, storage element, and IoT Bluetooth beacon. The MMTEG device generates an output of a nearly 60 Hz power cable connected to home appliances, with a weak magnetic field.

A hybrid vibration energy harvester made by TENG and EMG is presented in [199], to power an active RFID tag of a wearable system embedded in shoes, so that the automatic long-distance identification for door access can be realized. In the meantime, the fabric-based TENG is also fabricated with a superhydrophobic coating (Figure 8g) [200]. The integration of the diode can significantly enhance the output used in the wireless transmission. The tunable oscillation frequency response offered by the tunable external capacitor achieves a wireless control system via the coils. In addition, an optical media is proposed for wireless communication. By integrating a TENG with a microswitch, an LC resonant circuit, and a coupling inductor, a red laser and a photodetector can act as the transmitter and receiver, respectively, for wireless data communication with identification undertaken by the external capacitors [201].

Figure 8.

Self-powered power and data transmission. (a) Broadband piezoelectric ultrasonic energy harvester for powering implantable biomedical devices. Reproduced with permission [191]. Copyright 2016, Springer Nature. (b) Self-powered body sensory network for wearable and implantable applications. Reproduced with permission [192]. Copyright 2019, American Chemical Society. (c) An electronic watch powered by an electromagnetic–triboelectric nanogenerator. Reproduced with permission [193]. Copyright 2015, American Chemical Society. (d) Human body-coupled power delivery and ambient energy harvesting. Reproduced with permission [194]. Copyright 2020, IEEE. (e) Resonant inductive wireless power transfer glove using embroidered textile coils. Reproduced with permission [195]. Copyright 2020, IEEE. (f) Printed textile-based carbon antenna for wearable energy harvesting. Reproduced with permission [196]. Copyright 2022, IEEE. (g) Short-range self-powered wireless sensor network using triboelectric mechanism. Reproduced with permission [200]. Copyright 2020, Elsevier.

7. Machine Learning-Enabled Intelligent Wearable HMIs

The introduction of ML technology in the current sensory system is reshaping the concept of smart sensors in various fields, ranging from healthcare to industrial and environmental monitoring [202,203,204,205]. The extraction of specific features from the respective dimensions through the massive datasets can realize a more comprehensive interpretation of the raw sensing signals [206]. Diversified ML algorithms are reported for better analyzing the different types of information, such as vision, sound, chemical, and tactile [207]. By understanding whether the ML algorithms are learning the features with the labeled data or unlabeled data, the ML technique can also be categorized into supervised learning and unsupervised learning. For instance, supervised learning is frequently adopted in those wearable HMIs with classification functions. Owing to the edge computing capability, some of the primary ML processing can be undertaken locally to reduce the data volume in wireless communications.

Speech recognition and translation are the most popular applications of ML. A sign language recognition and communication system with a comfort textile-based glove can assist the communication between non-signer and signer (Figure 9a) [208]. This glove not only offers the recognition of words, e.g., single gestures, but also enables the translation of sentences, e.g., continuous multiple gestures, with accuracies above 90% via the non-segmentation frame. To reduce the computing power, dimension reduction, such as principal component analysis (PCA) and linear discriminant analysis (LDA), etc., is often used to preprocess the sensory data. To further expand the capability of recognizing new sentences without dataset training, the segmentation method is applied to divide all of the sentence signals into word fragments so that ML can learn them individually. Thus, the ML algorithm can inversely reconstruct and recognize the whole sentence through the established correlation of basic words and sentences. Furthermore, the segmentation approach renders new sentence recognition by recombining the trained word units in new orders. In Figure 9b, a TENG-based sensory floor mat fabricated by screen printing is shown, composed of reference electrode and coding electrodes for position tracking and gait recognition [209]. The ratio of voltage output is used as sensing data, which eliminates the humidity disturbance to the absolute amplitude of triboelectric output voltage. As a scalable smart home application, the recognition of 20 users is undertaken by training the datasets with a 1D convolutional neural network (CNN) mode. The preliminary recognition accuracy can reach above 90%. During the human–machine interactions, the collaboration of the recognition and manipulation functions can greatly improve the efficiency with better intelligence. A smart glove-based HMI is illustrated in Figure 9c [210]. With the triboelectric finger-bending sensors and palm shear sensors, this glove is able to capture the finger and hand motions with multiple degrees of freedom. More importantly, the CNN and SVM algorithms are applied to further analyze multichannel signals during the different interactions to achieve object and gesture recognition. A smart walking stick for assisting the elderly has been developed using a hybridized unit and a rotational unit made by TENGs and EMG, respectively (Figure 9d) [211]. The aluminum is divided into five electrodes in order for the bottom TENG to detect the entire contact process of the stick as the user walks. With the aid of a 1D CNN to analyze the multi-channel outputs from TENGs, the different statuses, such as sit, walk, and fall down, etc., of the different users can be identified through the featured patterns of outputs, and, hence, the obtained real-time status of the user can be projected in the spaces of visional monitoring and immediate assistance. The linear-to-rotary energy harvesting function of TENG and EMG can efficiently harvest the ultralow, under 1 Hz-driven frequency to serve as the power supply for a self-sustainable system with GPS tracking and multifunctional monitoring.

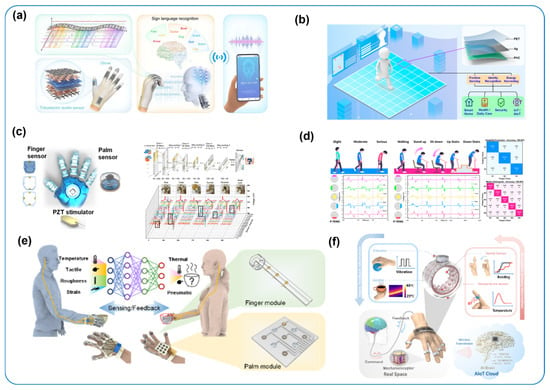

Figure 9.

AI-enabled wearable devices. (a) Sign language recognition using triboelectric smart glove. Reproduced with permission [208]. Copyright 2021, Springer Nature. (b) Floor monitoring system with AI for smart home applications. Reproduced with permission [209]. Copyright 2021, American Chemical Society. (c) Machine learning-enhanced smart glove for virtual/augmented reality applications. Reproduced with permission [210]. Copyright 2020, American Association for the Advancement of Science. (d) Caregiving walking stick for walking status monitoring. Reproduced with permission [211]. Copyright 2021, American Chemical Society. (e) Soft modular glove with AI-enabled augmented haptic feedback. Reproduced with permission [212]. Copyright 2022, American Chemical Society. (f) Augmented tactile-perception and haptic-feedback rings. Reproduced with permission [213]. Copyright 2022, Springer Nature.

On the other hand, most of the current ML-based applications focus simply on the analysis of sensing information. There is almost no research on the fusion of ML-enabled sensing and feedback, due to the spatial inconsistency between two components. A modular soft functionalized by Tactile+ (tactile plus) units is proposed with the ability to provide both sensing and feedback functions from the same unit (Figure 9e) [212]. Specifically, the Tactile+ units on finger modules and the palm module possess triboelectric tactile and strain sensing, pneumatic actuation, triboelectric-based monitoring of pneumatic actuation, temperature sensing, and thermal feedback. In addition to the basic manipulation functions and the ML-assisted object recognition, the recognition data can be applied to initiate the multimodal-augmented haptic feedback via tunable feedback patterns, which indicates a potential direction for the intelligent fusion of sensing and feedback capabilities. For an ML-assisted wearable system, miniaturization is a constant topic in the research field. The augmented tactile-perception and haptic-feedback rings with multimodal sensing and feedback capabilities shown in Figure 9f indicates a possible direction [213]. All of the thermal and tactile sensing and feedback functions are integrated into a minimalist designed ring and driven by a custom IoT module with the potential of edge computing. The voltage integration process of the raw signals realizes both dynamic and static detection by TENG sensors. This type of signal also provides ML-based gesture recognition with a higher accuracy of 99.821%. The self-powered TENG and PENG sensing units further reduce the power consumption for long sustainability. An interactive metaverse platform with cross-space perception capability is demonstrated by projecting objects in the real space into the virtual space, and is simultaneously felt by another virtual reality user in remote real space for a more immersive experience.

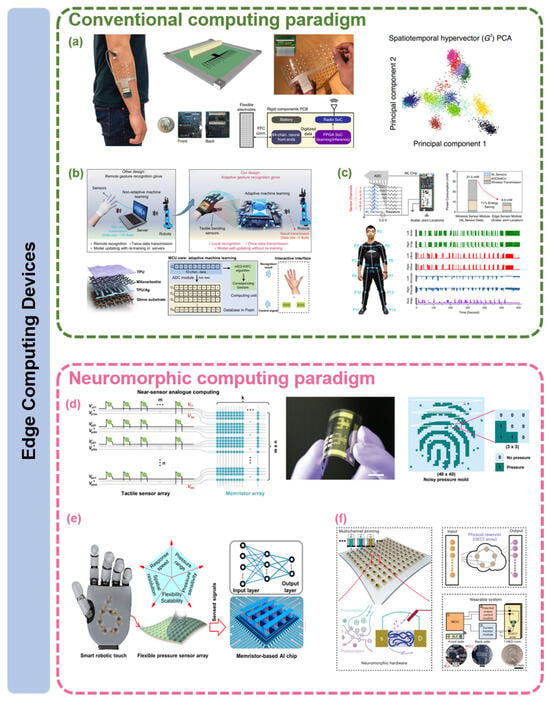

8. Wearable HMIs with Edge Computing

The increasing number of sensing terminals in sensor networks induces a severe problem of redundant data exchange between the sensing terminals and the computing units [214]. To mitigate the problem, a straightforward solution is to incorporate edge computing technology, placing the computing units close to or even inside the sensor itself. With this computing architecture, the excessive data exchange between the wearable system and external computing hardware or cloud computing infrastructure is eliminated. As a result, the energy consumption and latency of the system is reduced [215] and the privacy safety of the user is reinforced [216]. The implementation of edge computing wearable HMI systems encompasses two approaches: on one hand, highly integrated systems based on the conventional von Neumann computing paradigm are built to ensure the computing unit’s proximity to sensing terminals [217,218,219,220]; on the other hand, novel neuromorphic computing paradigms are achieved via artificial sensing neurons like memristors [221,222,223,224,225], memtransistors [226,227] and other innovative devices [228,229,230,231,232].

Many researchers have proposed wearable intelligent sensing HMIs with near-sensor data processing functionality based on the conventional computing paradigm. For instance, Moin et al. [217] have reported a highly integrated, flexible bio-sensing system which can perform real-time gesture recognition locally (i.e., near sensor) via surface electromyography (sEMG) (Figure 10a). A machine learning model is deployed in a miniaturized printed circuit board, reducing the latency and power consumption of the system. The model can adapt to changes in biological conditions (e.g., sweat, fatigue, etc.), as well as changes in forearm position. The high-density sensing unit encompass 4 × 16 electrodes to capture sEMG signal. The sensing unit is interfaced with a custom PCB, which consists mainly of a system-on-a-chip (SoC) field-programmable gate array (FPGA) and a 2.4 GHz radio SoC for data transmission. The system is powered by a lithium-ion battery. The classification of gestures is performed by a simple clustering algorithm, with each cluster centroid representing each gesture. This simple yet efficient algorithm facilitates the local deployment of the model and makes online adaptation possible. The throughput of the system is reported to be 20 predictions per second, illustrating the advantage of edge computing. An accuracy of 97.12% is reported for 13 gestures in 2 participants and an accuracy of 92.87% is preserved for 21 gestures.

Figure 10.

Wearable HMIs with edge computing functionality. (a) A highly integrated, edge computing system for real-time gesture recognition. Reproduced with permission [217]. Copyright 2021, Springer Nature. (b) A textile-based smart glove for local gesture recognition. Reproduced with permission [219]. Copyright 2024, Wiley-VCH. (c) A wearable, near-sensor computing system for full-pose reconstruction. Reproduced with permission [220]. Copyright 2022, Springer Nature. (d) A wearable, neuromorphic computing system based on the memristor array. Reproduced with permission [221]. Copyright 2022, Wiley-VCH. (e) A tactile sensing system with large memristor array for hand-written digits recognition. Reproduced with permission [222]. Copyright 2022, American Chemical Society. (f) A wearable system based on an array of organic electrochemical transistors for electromyography (EMG) signal analysis. Reproduced with permission [229]. Copyright 2024, Springer Nature.