Abstract

Microwave-assisted heating (MWH) has established itself as a transformative and energy-efficient paradigm for advanced materials processing. This review provides a comprehensive overview of the advances achieved at the CNR-SCITEC laboratories in Genoa. In this context, a customized microwave platform has been strategically employed for the synthesis, sintering, foaming, and melting of diverse inorganic, organic, and hybrid systems. The spectrum of materials investigated includes superconducting magnesium diboride (MgB2), hydroxyapatite-based scaffolds, polyethylene components obtained via microwave-assisted rotational molding, cork-based sound-adsorbing composites, recycled expanded polystyrene (rEPS) panels, and polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) piezoelectric films. Across the case studies, MWH demonstrated a superior capacity for reducing energy consumption and processing times while maintaining—or even enhancing—the target functional properties. Furthermore, this work evaluates the technological maturity and emerging market opportunities of microwave-based processing, positioning it as a key and sustainable platform for next-generation materials development.

1. Introduction

In the past decade, microwave-assisted heating (MWH) has emerged as a versatile and energy-efficient paradigm for the synthesis and processing of advanced materials [1,2]. Unlike conventional thermal methods, MWH relies on the direct interaction between electromagnetic radiation and the molecular structure of the material, enabling rapid, volumetric, and selective heating. A distinctive feature of MWH is the dramatic reduction in processing time—often achieving temperatures between 800 and 1600 °C within seconds—which, under specific conditions, can even trigger the formation of a low-temperature plasma plume [3].

The growing relevance of MWH is reflected in the establishment of dedicated scientific forums, such as the Microwave journal, which serves as a pivotal platform for discussing the latest advancements in microwave science and technology [3]. Within this evolving landscape, this comprehensive review explores the innovative MWH methodologies developed at CNR-SCITEC laboratories in Genoa. Our research leverages MWH to improve energy efficiency and environmental sustainability while enhancing the functional performance of diverse material systems.

The experimental activities discussed encompass a broad range of processing strategies, including MW-assisted rotational molding, (rotomolding, RM) of polyethylene (PE) powders, the sintering of hydroxyapatite (HAp)-based scaffolds for biomedical applications, the development of cork-based acoustic composites and recycled expanded polystyrene (rEPS) panels, and the fabrication of piezoelectric polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) films. These techniques span inorganic, organic, and inorganic–organic hybrid categories. The rapid synthesis of the superconducting MgB2 phase is also addressed. Finally, this review evaluates potential future industrial applications and market demands, highlighting the role of MWH as a key for next-generation materials development ([1,2,4] and references therein).

2. Fundamentals of Microwave–Material Interactions

2.1. Microwave–Material Interaction Mechanisms

Microwaves are a form of electromagnetic radiation with frequencies ranging from 300 MHz to 300 GHz [5]. To avoid interference with military and civil communications, the most common frequency used in industrial and domestic microwave ovens is 2.45 GHz. The interaction of microwaves with materials involves several complex physical phenomena due to both the electric and magnetic fields, which are orthogonal to each other, forming the electromagnetic wave. These interactions involve one or more of the following mechanisms, which can act alone or in combination in transforming the absorbed microwave energy into heat within a material [6,7]:

- Conductive heating: In some conductive materials, microwaves can induce electric currents. These currents generate heat due to the electrical resistance of the material. This is common in metals and some semiconductors;

- Ionic polarization heating or ionic conduction: In some ionic materials, microwaves can cause the movement of ions, creating an electric current. The resistance to this current flow generates heat. This mechanism is similar to dielectric heating but involves ions instead of polar molecules. It is particularly effective in materials with high ionic conductivity;

- Dielectric heating: This occurs when microwaves, due to their oscillating electromagnetic nature, interact with polar molecules, such as water. The continuous change in the electric field causes these molecules to oscillate rapidly. The friction between these oscillating molecules generates heat. This principle is widely used in microwave ovens to heat food;

- Dipolar polarization: In materials with permanent dipole moments, microwaves cause the dipoles to align with the alternating electric field. The continuous reorientation of dipoles generates heat through molecular friction. This is a fundamental aspect of dielectric heating, but on its own, it may not be sufficient for significant heating;

- Magnetic heating: Some magnetic materials can heat up when exposed to microwaves due to magnetic losses. This occurs when the magnetic domains within the material oscillate in response to the alternating magnetic field of the microwaves, generating heat;

- Several losses can contribute to this phenomenon: hysteresis, eddy currents, and residual currents. The latter can be due to domain wall resonance and electron spin (also called ferromagnetic resonance);

- Joule heating: This mechanism is like conductive heating but occurs mainly in materials with significant electrical resistance. Microwaves induce currents that, due to the material’s resistance, produce heat. This type of heating can be due to both the electric field as well as the magnetic field when it comes to induced currents.

Based on these mechanisms, electromagnetic radiation can be reflected (in metals), transmitted (quartz, PTFE), or absorbed by materials (Fe2SiO4, Fe3O4, BaTiO3, TiO2, SiC).

Materials can thus be classified into four categories:

- Transparent: Completely transparent materials are rare in practice, as even small impurities can introduce absorption;

- Reflecting or opaque: Even though metals can reflect microwaves, a skin effect with eddy currents can still occur on the external surface layer, causing the metal to heat up. This is why aluminum foil is not allowed in microwave ovens. In fact, a thin metal sheet, due to its large surface area, generates a large amount of heat due to eddy currents. However, its ability to dissipate this heat is limited by its small volume and the conditions of heat exchange with the surrounding environment;

- Absorber: These are materials like water (dipolar polarization) and SiC (ionic conduction) [8];

- Mixed absorber: Advanced materials like composites in which the matrix can be metallic, ceramic, or polymeric.

These interactions enable microwaves to heat materials rapidly and uniformly, making them ideal for various industrial applications, including material processing and synthesis.

2.2. Dipolar Polarization: Interaction with Permanent Dipoles (e.g., Water)

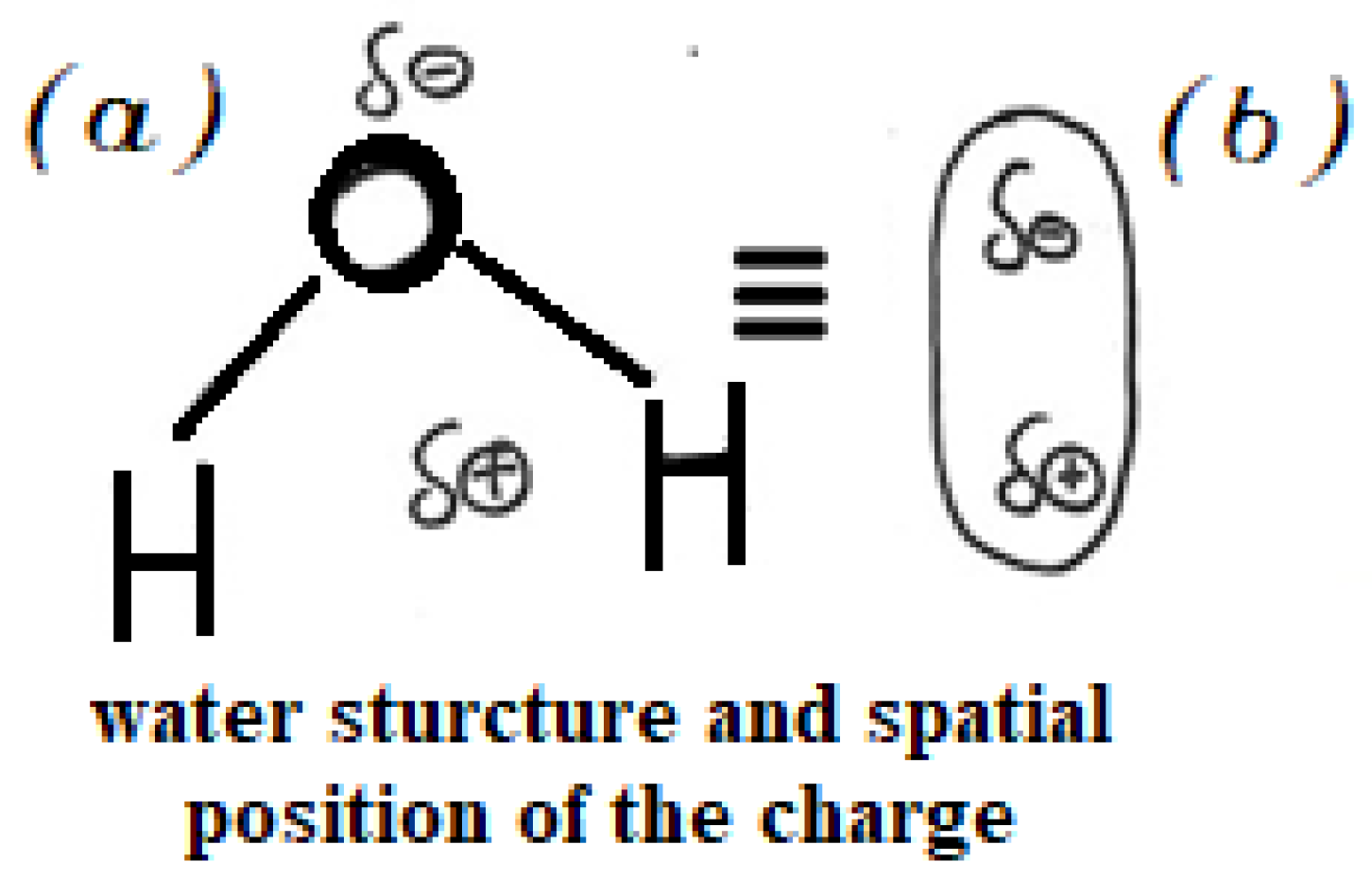

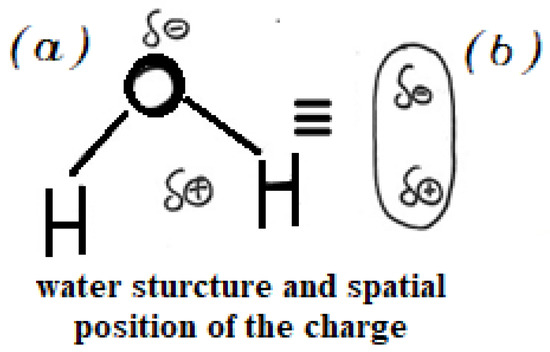

The intensity of the heating depends on several factors, such as material polarizability, electric field frequency, and material conductivity. Due to its strong polar nature (see Figure 1), water is especially prone to dielectric heating. Its high dielectric constant and widespread presence in various materials make it an effective absorber of electromagnetic radiation.

Figure 1.

(a) Spatial arrangement of atoms in the water molecule, showing the separation between the barycenter of positive and negative charges and (b) the corresponding schematic representation.

The high dielectric constant of water arises from the significant charge separation caused by the electronegativity difference between oxygen and hydrogen and molecular geometry. Oxygen (O) carries a partial negative charge (δ−), while each hydrogen (H) carries a partial positive charge (δ’+). The barycentre of the positive charge lies between the two H (δ’+ + δ’+ = δ+), whereas the barycentre of the negative charge lies on O atom. Although the molecule possesses permanent dipole, the overall charge remains zero (δ+ + δ− = 0), so each water molecule remains electrically neutral. Figure 1, two equivalent representations of the distribution of the charge in a molecule of water.

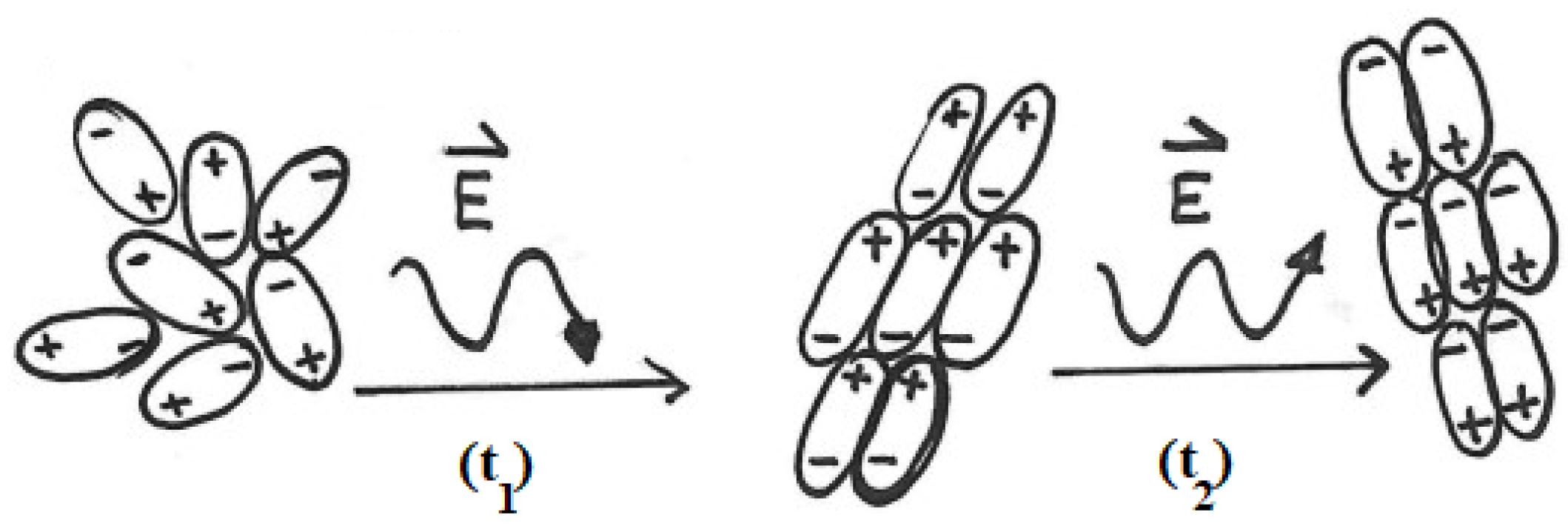

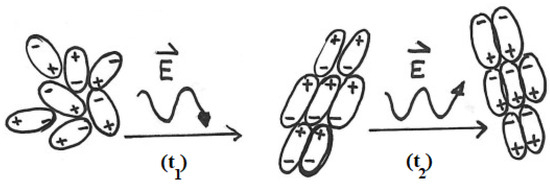

Figure 2: At t0 the water molecules are randomly oriented. When an electric field is applied (t1), the molecules align with the field. Because the field periodically reverses its direction, at time t2, the molecules adopt the opposite orientation with respect to t1. These rapid reorientations generate molecular friction, which explains the efficient heating of water under MW irradiation.

Figure 2.

Some water molecules are initially randomly oriented. At time t1, an electric field is applied, and the molecules align accordingly. Because the field periodically reverses its direction, at time t2, the water molecules adopt the opposite orientation with respect to t1. (The symbol E, the letter E with an overhead arrow, is a standard scientific notation used to represent the electric field vector of the microwave radiation.)

This work considers both active and passive MWH, while largely excluding magnetic loss mechanisms, which are difficult to exploit in practical applications due to Curie temperature limitations. From a heating point of view, magnetic materials are complicated to treat for real applications, also because we must consider that when they are heated over their Curie temperature, they lose their magnetic behavior. Demagnetization also depends on the exposure time, especially for ceramic magnetic materials, such as rTMRs (room temperature magnetic refrigeration materials).

Because the present paper addresses various composites for applications, each component in the composite can interact through different mechanisms previously exposed, such as HAp and Fe2SiO4, for their ionic nature involves the ionic conduction, but the presence of water in water glass (WG) (a water solution of sodium trisilicate, Na2SiO3) or in egg white (EW) involves dielectric conduction and dipolar polarization. When processing cork and egg white, the presence of water makes dielectric and dipolar mechanisms predominant. In the case of the composite obtained by mixing polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) with barium titanate (BaTiO3 or BT), represented as PVDF-BT, the heating is due to the dipolar polarization of PVDF and ionic conduction of BaTiO3.

2.3. Non-Polar or Weakly Polar Material: Polyethylene and Similar Polymers

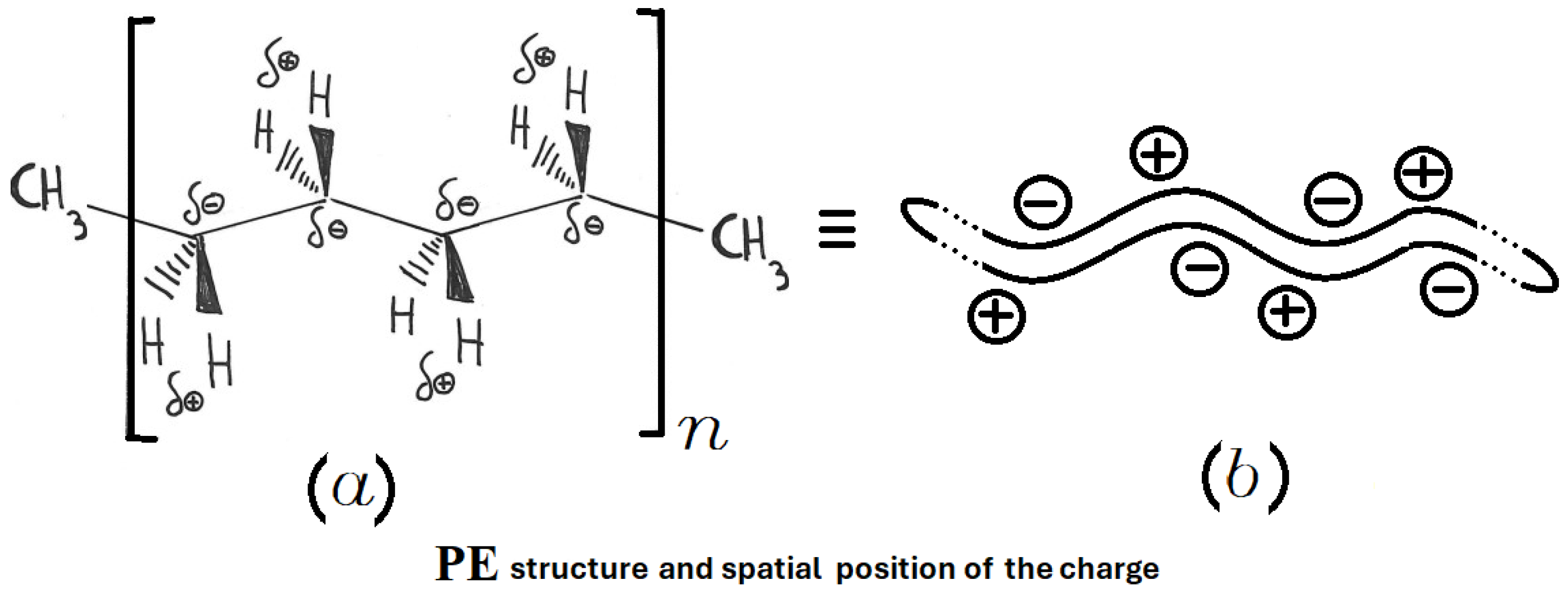

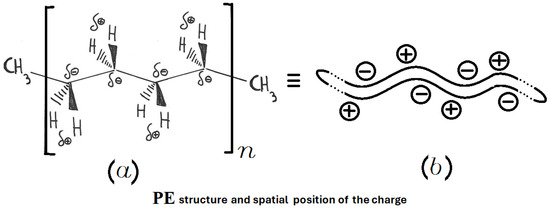

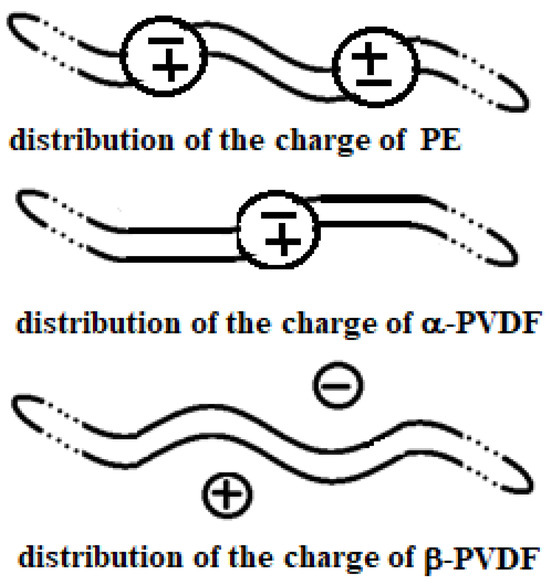

Active heating refers to the direct heating of the material placed in the MW oven, while passive heating involves transferring heat to the material from another material that absorbs the microwaves and transforms them into heat, which is then released by conduction to the end user. Being a non-polar covalent polymer composed of repeating –CH2– units, polyethylene is heated only in the passive mode. The structure of PE is shown in Figure 3, considering both final sides represented by CH3– and a long repetition, defined by the value of n, of –CH2–CH2–CH2–CH2–. Here, the four carbon atoms are not represented with C in each corner of the main structure for better readability. The overlap between the centers of positive and negative charge renders PE effectively transparent to microwaves. This overlap is shown in the upper structure of Figure 4.

Figure 3.

Structure of PE: (a) spatial arrangements of atoms and corresponding charge distribution; (b) simplified schematic representation of the PE macromolecule.

Figure 4.

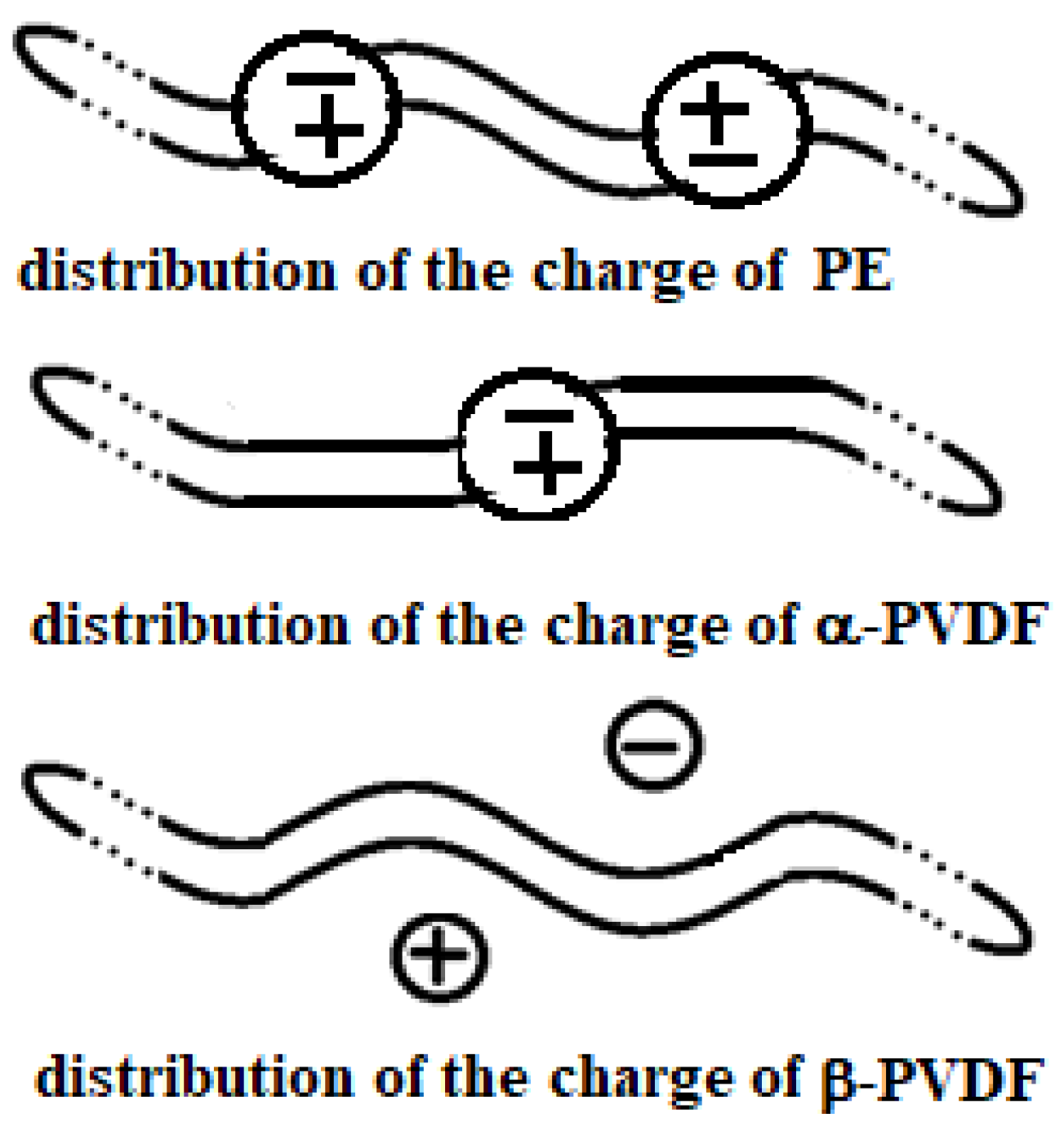

Actual charge distribution in the three structures (from top to bottom): PE, α-PVDF, and β-PVDF.

To heat the PE, it is necessary to cover the molds containing the PE with materials capable of absorbing and converting the microwave energy into heat.

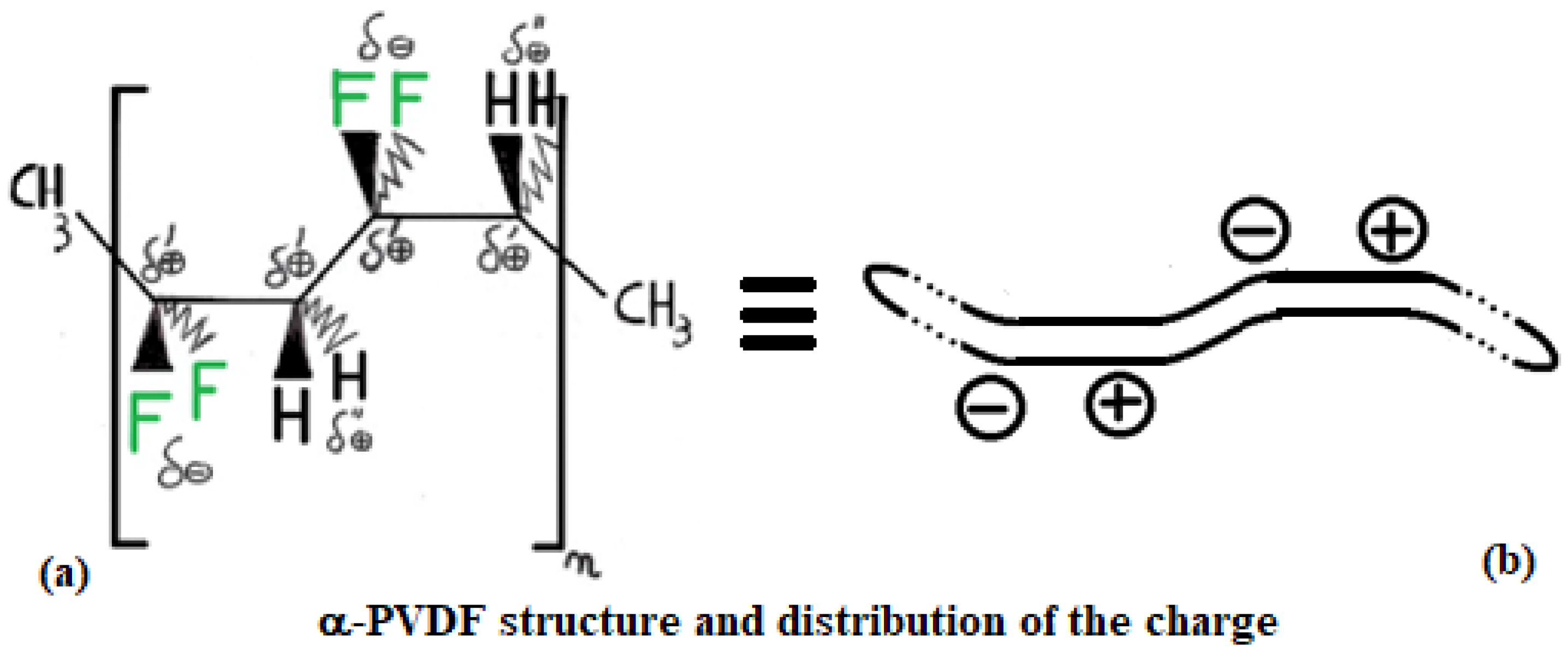

2.4. Intermediate Case: Polar Polymers with Isotropic Structure (e.g., PVDF)

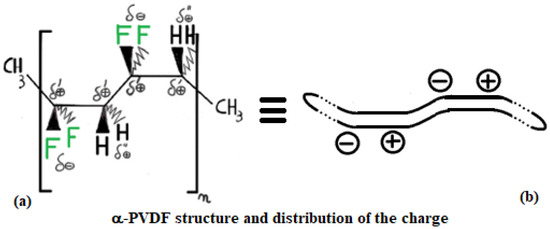

PVDF exhibits multiple polymorphic structures (α, β, γ, δ, ε) [9], and in contrast to PE, it can respond very well to microwaves, having an active role in the heating process [10]. Its structure type depends on the condition in which its solid crystal structure forms after a melting process. Its backbone is made up of alternating –CH2– and –CF2–, represented for α and β structures in Figure 5 and Figure 6 by repeating n times the unit (–CH2–CF2–CH2–CF2–). β-PVDF shows the strongest dipole character, while α-PVDF shows no polar character. The first is characterized by a neat separation of charges, while the second is not, as graphically summarized in Figure 4. The remaining γ, δ, and ε structures represent intermediate situations with less dipole character than β and more than α. The MW response of PVDF depends on the solidification parameters and preparation procedures applied, which determine the final amount of crystalline phase (generally between 35 and 70%) relative to the amorphous phase. Generally, in the crystalline phase, the three phases α, β, and γ are always present, with percentages depending on the process adopted for material processing. A detailed discussion of these aspects, including the relevant literature references, is provided in Section 3.6.

Figure 5.

Structure of α-PVDF: (a) spatial arrangement of atoms in space and corresponding charge distribution; (b) simplified schematic representation of the PVDF macromolecule.

Figure 6.

Structure of β-PVDF: (a) spatial arrangement of atoms in space and corresponding charge distribution; (b) simplified representation of the PVDF macromolecule.

3. Microwave-Assisted Techniques for the Preparation of Advanced Materials

In the following subsections, we report on the various products prepared at CNR- SCITEC laboratories in Genoa (Italy) using the MW-assisted heating. This technique has been employed to sinter, synthesize, geopolymerize, or simply heat and manufacture different compounds or composites.

MW-assisted rotomolding has recently emerged as a promising alternative to conventional heating due to its selective and volumetric energy deposition. At the SCITEC laboratory, we explored this approach at both laboratory and industrial scales, as reported in the two following subparagraphs.

3.1. Microwave-Assisted Rotomolding of Polyethylene on Laboratory Scale

Conventional rotational molding (RM) of polyethylene (PE) is a highly energy-demanding process typically carried out using gas or electrically heated ovens. In our work, we developed MW-active coatings based on silicon carbide (SiC), iron oxide (Fe2O3), and iron silicate (Fe2SiO4) [11,12,13]. When mixed with silicone resin or WG, each filler forms a spreadable paste that can be applied onto a mold surface, enabling efficient microwave heating and significantly improving the overall energy performance of the RM process [11]. Laboratory-scale experiments indicated that a 2:1 ratio between microwave-susceptible inorganic filler and silicone resin produced the most effective coating formulations. These coatings were applied to molds made from materials such as aluminum, stainless steel, and glass. Under MW-assisted RM conditions, the coated molds exhibited faster and more homogeneous heating, rapidly reaching the temperatures required for polymer melting. Although the process is not yet fully optimized, it successfully yielded molded products with quality comparable to those obtained through conventional RM. Physico-chemical analyses (FTIR and DSC) confirmed the absence of polymer degradation under microwave heating. Mechanical testing further demonstrated that the MW-processed performance is comparable to commercially molded counterparts [11].

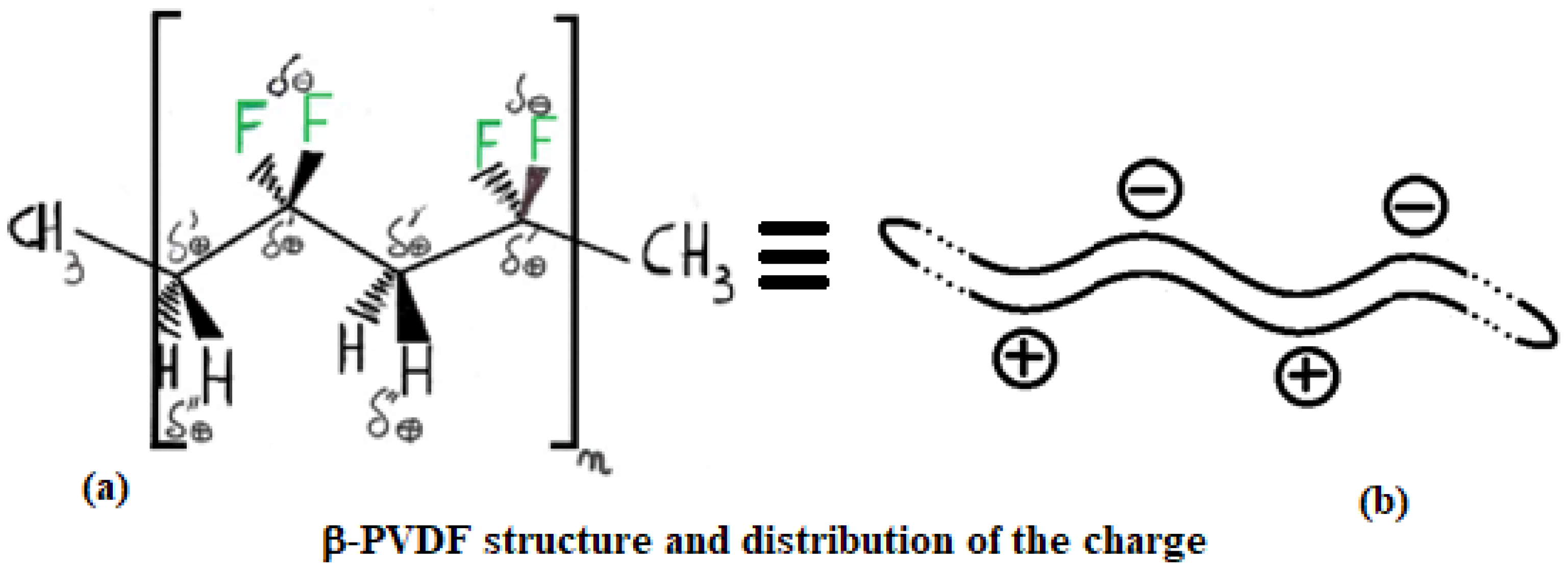

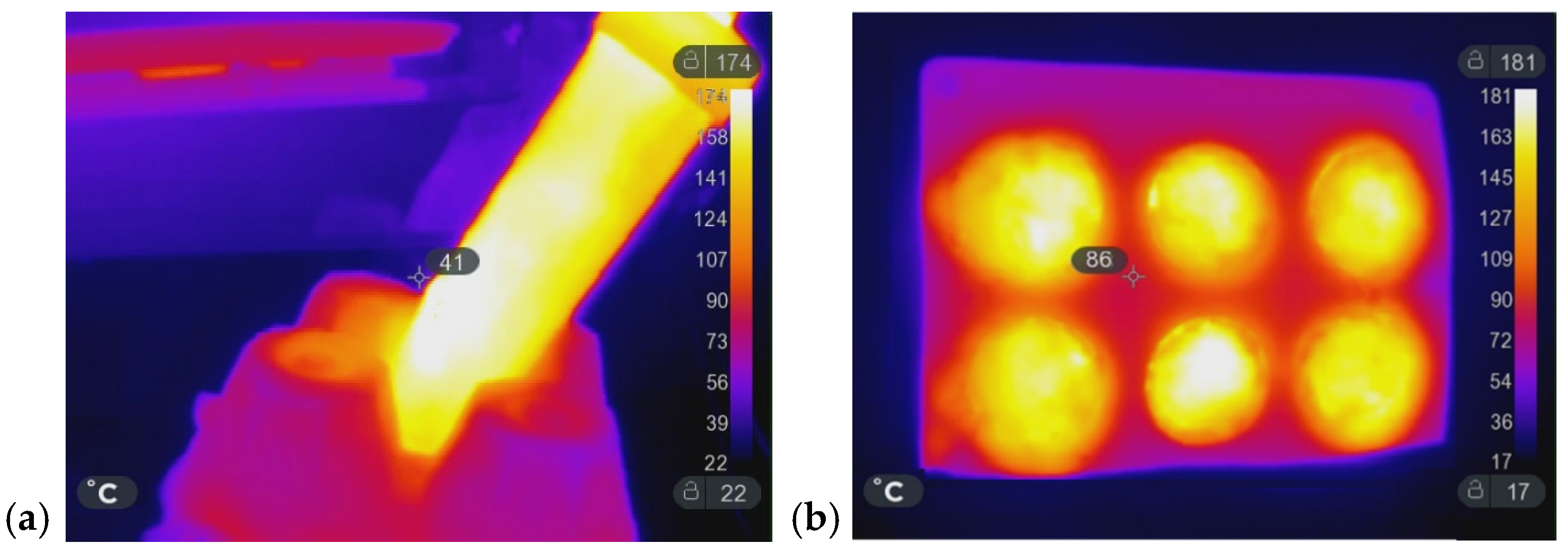

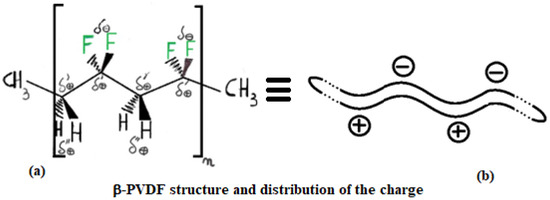

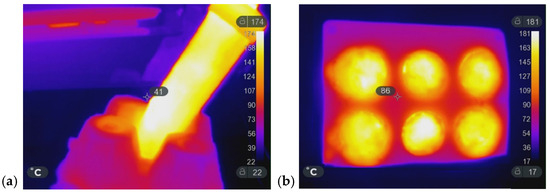

Figure 7a shows the IR image of the laboratory mold used to prepare a demonstrator product, while Figure 7b illustrates the corresponding molded items. As previously discussed, the MW-assisted RM process was successfully applied to a variety of materials in both powder and pellet form, such as recycled PP (Corepla, Milan, Italy), PBE003 (Nature Plast, Mondeville, France, PLA (Mondo, Piedmont, Italy), Mater-Bi (Novamont, Novara, Italy), and LDPE (Polyplast, Vigevano, Italy), including the processing of PVDF powder (Solef 1008 Solvay, Bollate, Italy), which has the highest melting interval. Pellets required longer melting times than powders, resulting in a porous appearance: the beads fused at the surface but did not fully close the interstitial voids. A longer heating time would likely eliminate this effect; however, the experiments were sufficient to demonstrate the feasibility of the process. The positive outcomes obtained at the laboratory scale provided the basis for the subsequent industrial-scale implementation.

Figure 7.

(a) IR image of the lab-scale mold during MW heating; (b) objects prepared by MW-assisted RM using different plastic materials in pellets or powder form. From top-left to bottom: PBE 003 (pellets), recycled PP (pellets), PLA (pellets), PE (powder), PVDF (powder), and Mater-Bi (pellets).

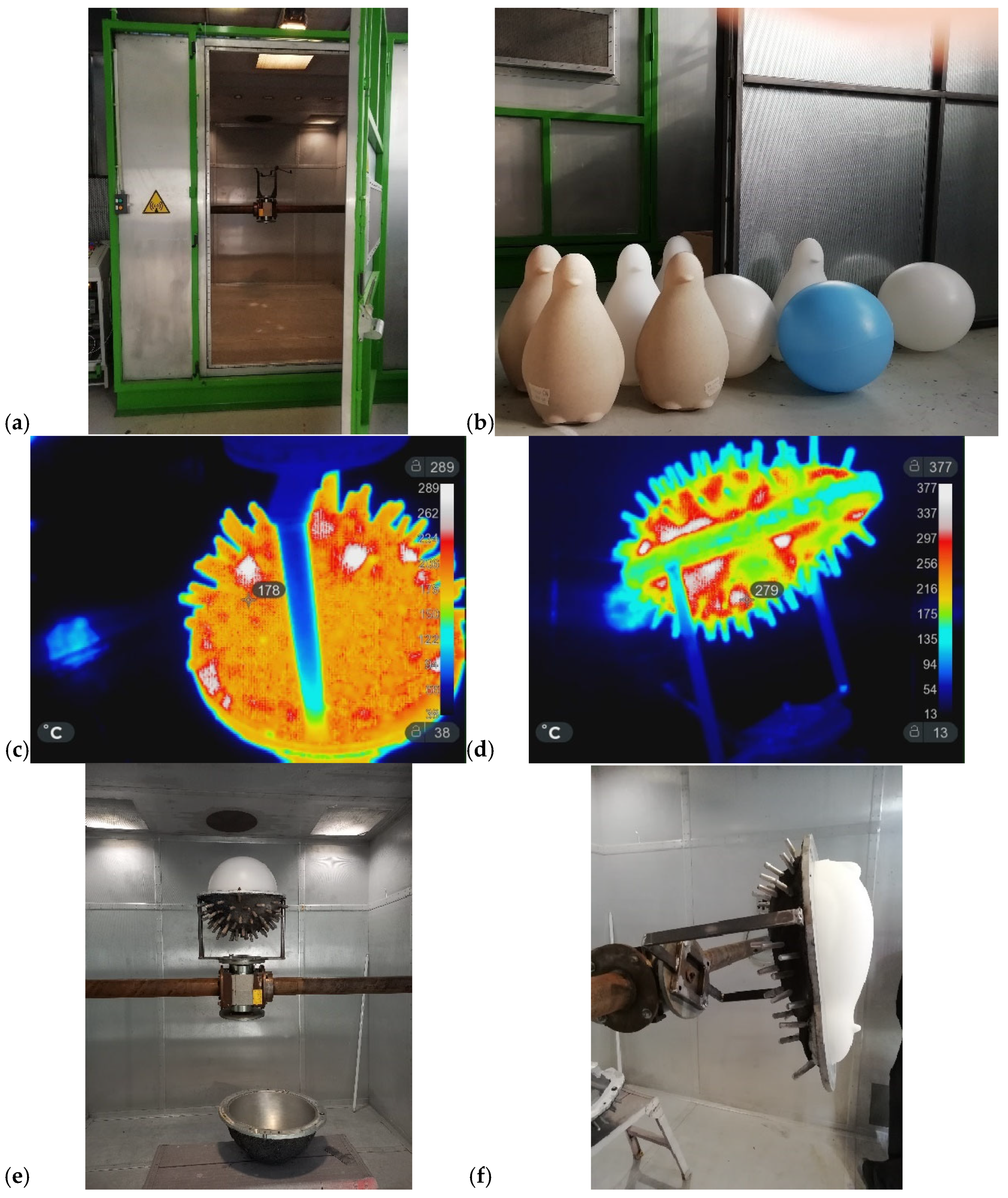

3.2. Industrial Scale-Up of Microwave-Assisted Rotomolding

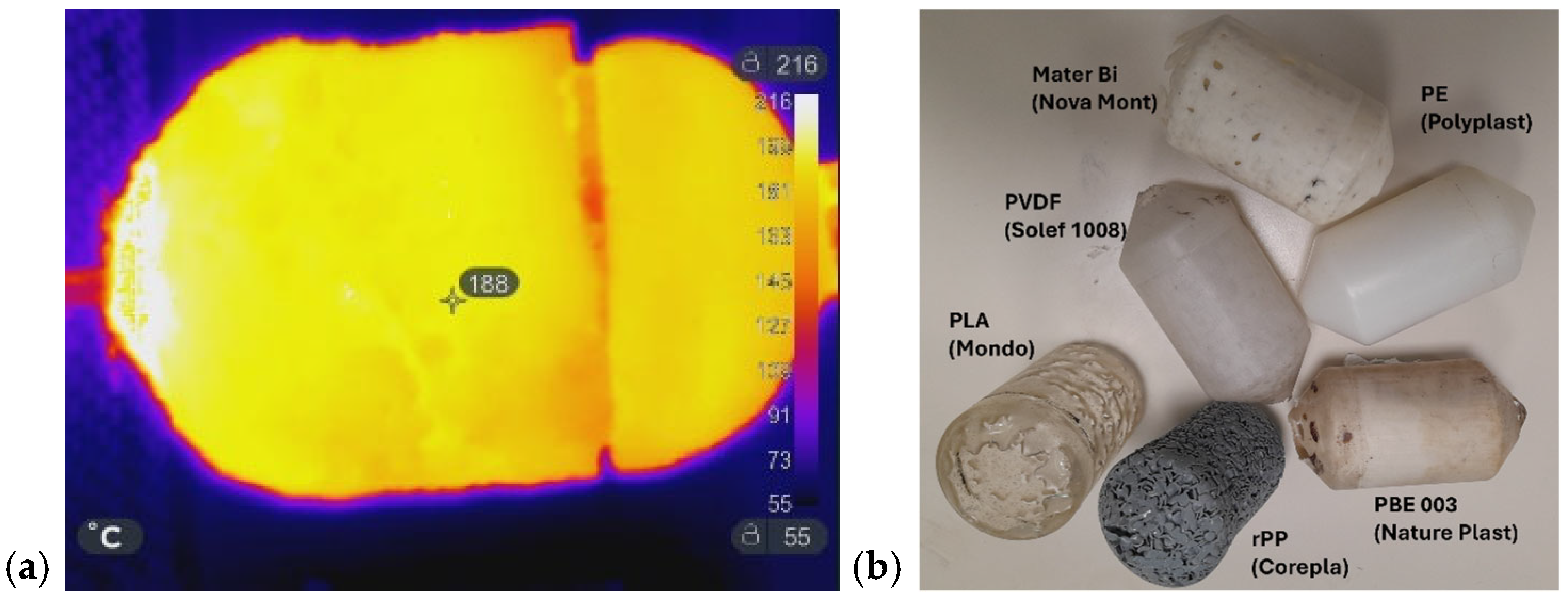

Building on the laboratory-scale results, the ROPEVEMI Project [12] scaled up the MW-assisted RM process to industrial levels. This project demonstrated the feasibility of manufacturing medium- to large-scale hollow PE components using MWH, achieving significant energy savings and a marked reduction in greenhouse gas emissions [11,12,13]. At the industrial site where the molding trials were conducted, the prototype MW oven operated exclusively on energy supplied by a dedicated photovoltaic system. As reported in the literature, similar progress has been achieved in scaling up MW-assisted techniques for the synthesis of graphene nanocomposites, with promising implications for electronics and energy storage applications [14,15]. In this case, as well, the industrial-scale process preserved the high quality of the PE products and demonstrated itself as a sustainable and cost-effective alternative to traditional RM techniques. This study involved the selection of MW-active materials such as Fe2SiO4, SiC, TiO2, Fe2O3, and BaTiO3, which were incorporated into different binding matrices to produce formulations capable of coating RM molds and enabling their efficient heating in a microwave oven [11,12,13]. This work also detailed the design and testing of a prototype MW oven and the subsequent fabrication of PE items using this innovative approach. Notably, the modified molds remained fully compatible with a conventional thermal oven.

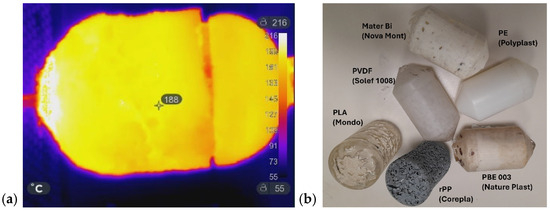

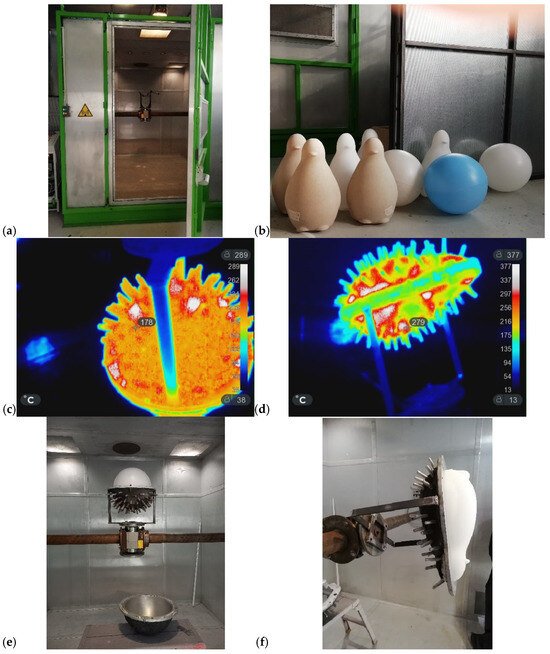

Figure 8 presents the following: (a) the industrial prototype MW oven; (b) PE products manufactured through the MW-assisted RM process; (c) and (d) are IR images of the spheres and penguin molds during the MW heating (MWH); and (e) and (f) are the corresponding finished products during the demolding. In this case, the process parameters consisted of 15 min of heating and 20 min of cooling. Heating was provided by five magnetrons operating at 90% of their nominal 6 kW power. The rotation speeds were set to 3 rpm for the primary axis and 6 rpm for the secondary axis (sample holder). The amount of PE (Plastene powders, Polyplast, Italy) ranged from 1.5 kg to 3 kg. Figure 8f shows the sample holder alone, whereas Figure 8e illustrates it positioned at the center of the principal axis inside the MW oven. The project ROPEVEMI, funded by the Italian Economic Development Ministry, Regione Lombardia and Regione Liguria, was successfully completed in December 2023. The remarkable volume expansion exhibited by water glass under MW heating prompted us to investigate its potential in scaffold preparation, as discussed in the following subsection.

Figure 8.

(a) Front view of the industrial MW-oven prototype; (b) several products produced using the prototype; (c,d) IR images of the sphere and penguin molds during the MWH process; (e,f) the corresponding finished products during the demolding.

3.3. Microwave-Assisted Fabrication of Hydroxyapatite Scaffolds

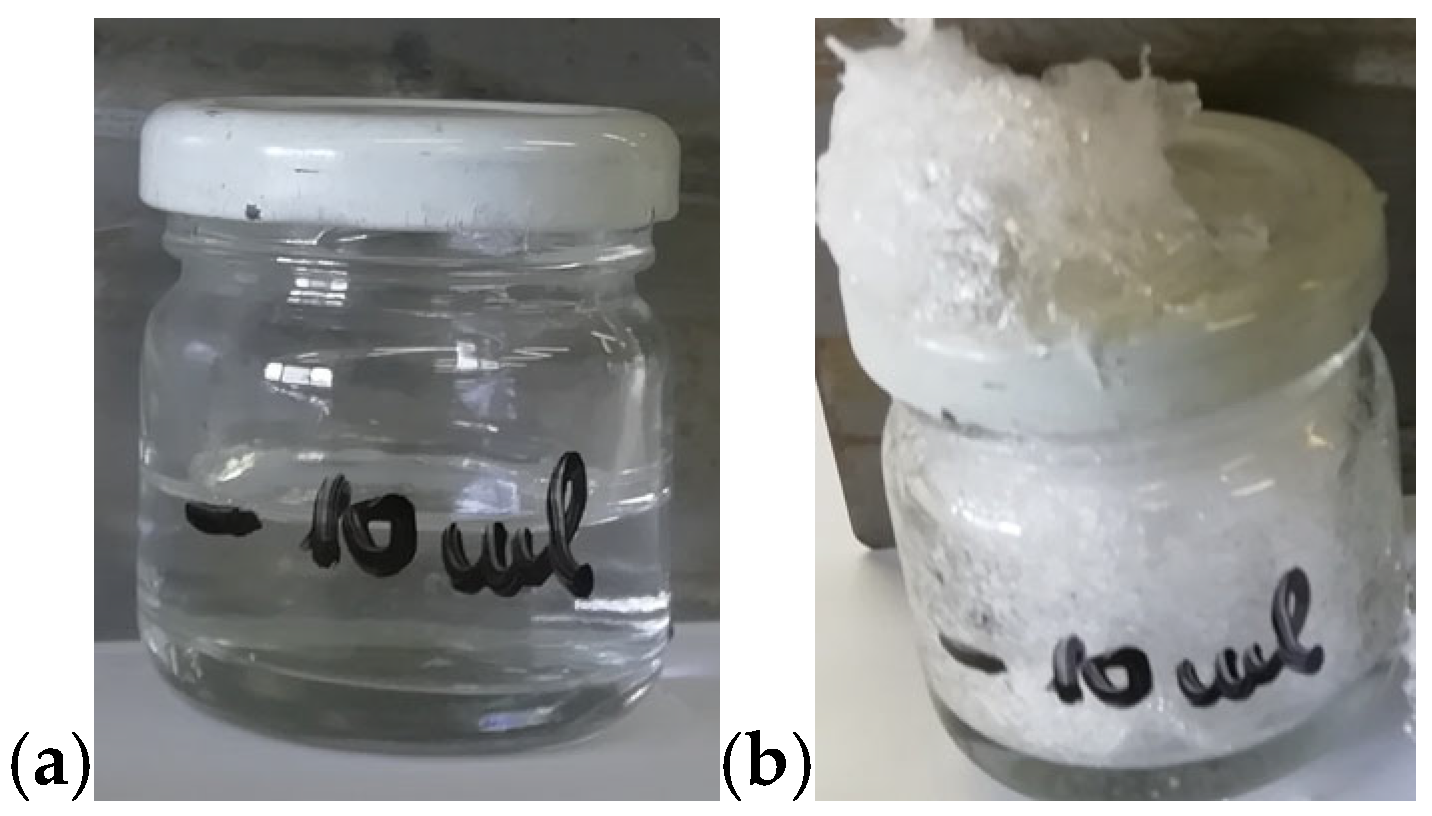

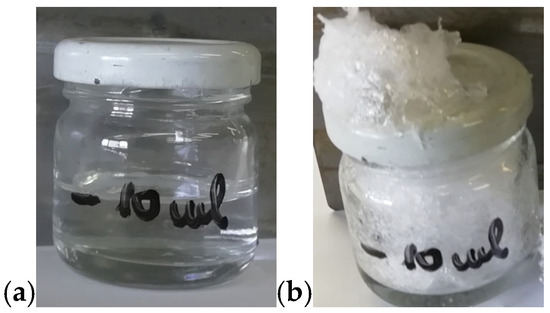

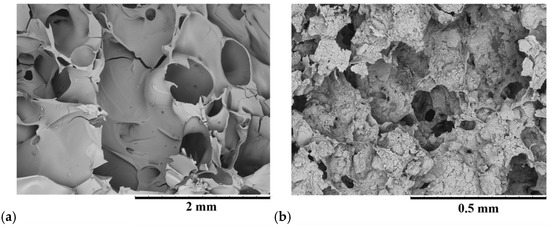

Beyond polymer and composite processing, MW heating can also be leveraged for the rapid fabrication of biocompatible structures. Building on this versatility, we investigated an MW-assisted route for preparing hydroxyapatite-based scaffolds for biomedical applications. In previous projects, PE melting was achieved indirectly by using MW-active materials to absorb the radiation and transfer heat to the polymer powder through conduction via an aluminum mold. In the present work, the water contained in water glass (an aqueous solution of sodium trisilicate, Na2SiO3) is directly heated by MW, thereby activating the geopolymerization of Na2SiO3 with Ca10(PO4)6(OH)2 and egg white protein. Within the field of biomedical engineering, our laboratory developed a rapid and cost-effective method for producing biocompatible scaffolds for bone tissue regeneration using a standard domestic microwave oven. These scaffolds consisted of hydroxyapatite (HAp) and Na2SiO3, which were foamed under microwave irradiation to generate a porous architecture suitable for tissue regeneration [16]. As reported in the literature, MW-assisted techniques have also shown promise in fabricating biocompatible scaffolds from materials such as calcium phosphate and collagen, broadening their potential applications in tissue engineering [17,18]. The idea of employing water glass (WG) for scaffold preparation emerged during the development of the ROPEVEMI project. During the investigation of WG under MW irradiation, we observed a remarkable volume expansion—approximately three to four times its initial volume. Figure 9a shows a 30 mL glass jar with a metal cap containing 10 mL of WG, which was foamed at 700 W for 10 min. Figure 9b displays the expanded WG obtained after MW heating. The metal cap was used to contain WG and limit its expansion; a small hole was drilled to allow vapor release and prevent over-pressurization. This experiment immediately suggested that a simple household MW could be used to produce, within a few minutes, a scaffold suitable for bone cell growth, potentially using plaster molds fabricated with a 3D printer. Potential applications in the medical field range from educational tools for medical students to support for planning orthopedic interventions.

Figure 9.

(a) A 25 mL glass jar with a metal cap containing 10 mL WG before the MW-induced expansion process; (b) the same jar after the expansion under limited-volume conditions. The process was carried out by MWH (2.45 GHz) at 700 W for 10 min.

In the latter case, rapid replicas of human bones could be produced to simulate real-world scenarios, enhancing learning through hands-on experience. For instance, during surgical planning, clinicians could rely on realistic bone replicas with properties closer to actual tissue, rather than conventional plastic or rubber models. Instead of relying on a plastic or rubber replica, they could use a more realistic model with similar characteristics to the actual bone. Moreover, low-cost, patient-specific bone replicas could be fabricated to support regenerative treatments following trauma or surgical procedures.

Figure 10a,b show the IR images of closed and open molds during the heating process. In the presence of water, MW radiation brings the composite to a homogeneous temperature of approximately 180 °C.

Figure 10.

IR image of a sample prepared in (a) a 50 mL Falcon test tube and (b) an open silicone mold.

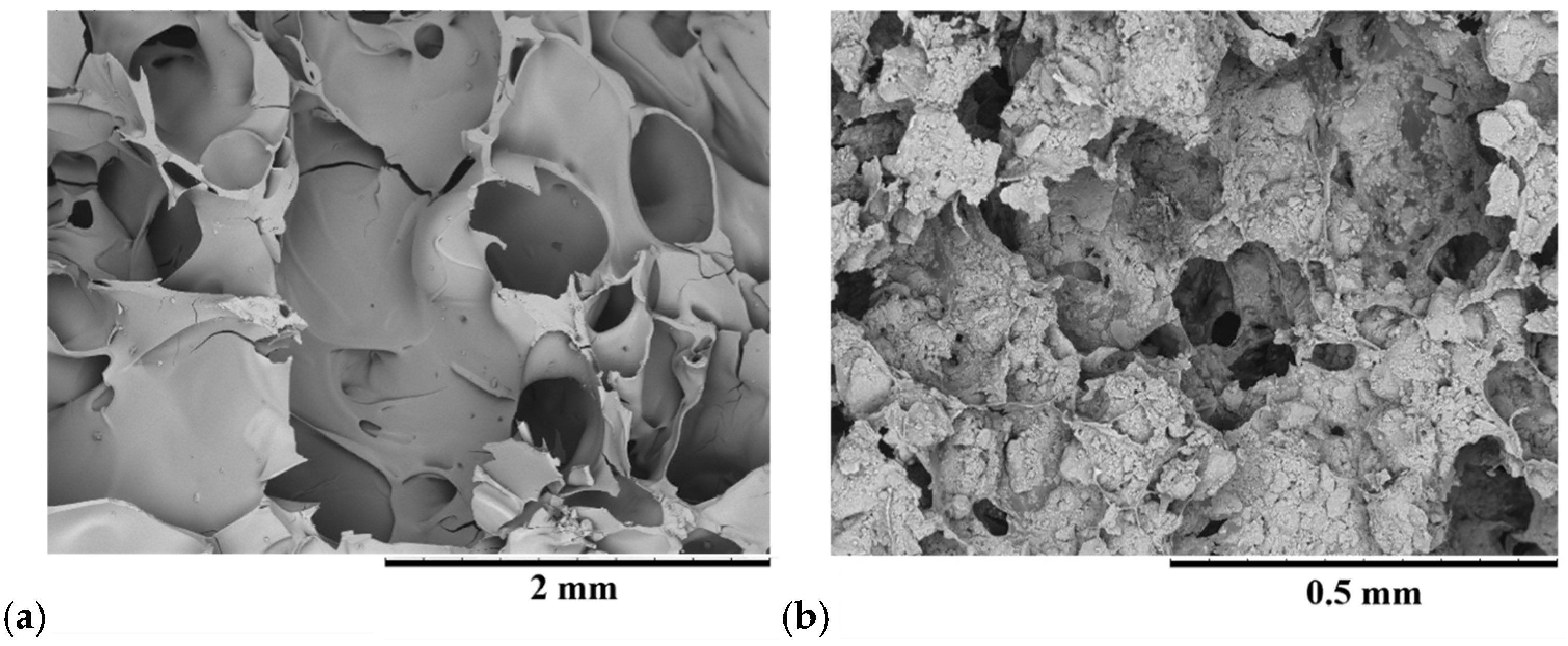

In Figure 11a, the SEM images show the morphology of WG foamed by the MWH process at 700 W for 10 min (more details are reported in [16]). Figure 11b shows the composite obtained with the same process on the mixture between egg white and HAp. In both cases, porous structures useful for cell growth are formed. The dimensions of these porosities can be modulated by adjusting the amount of water in the composite precursors, thus varying the quantities of components such as WG, egg white and HAp, bio-glass, etc., as well as processing parameters (power and time) [19,20]. Different amounts of water produce a bubble structure of 200–400 μm in diameter for WG and 50–100 μm for the egg white-HAp composite, as shown in Figure 11a,b.

Figure 11.

SEM images of (a) WG-HAp and (b) egg white proteins-HAp composites after the MWH process.

Finally, WG and HAp scaffolds showed positive outcomes in in vitro biological tests (qualitative cell viability and cytotoxicity analyses), allowing osteoblast growth [16]. Until now, our composite systems relied primarily on WG as an inorganic binder for materials such as Fe2SiO4 or HAp, as well as materials in the application of a minimal introduction of the organic phase, such as EW. The promising results achieved prompted us to investigate further applications involving alternative organic components, as presented in the next two subsections.

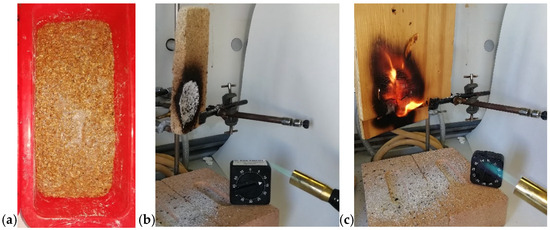

3.4. Microwave-Assisted Heat Treatment in Sustainable Bio-Composite Foams from Cork and Egg Wastes

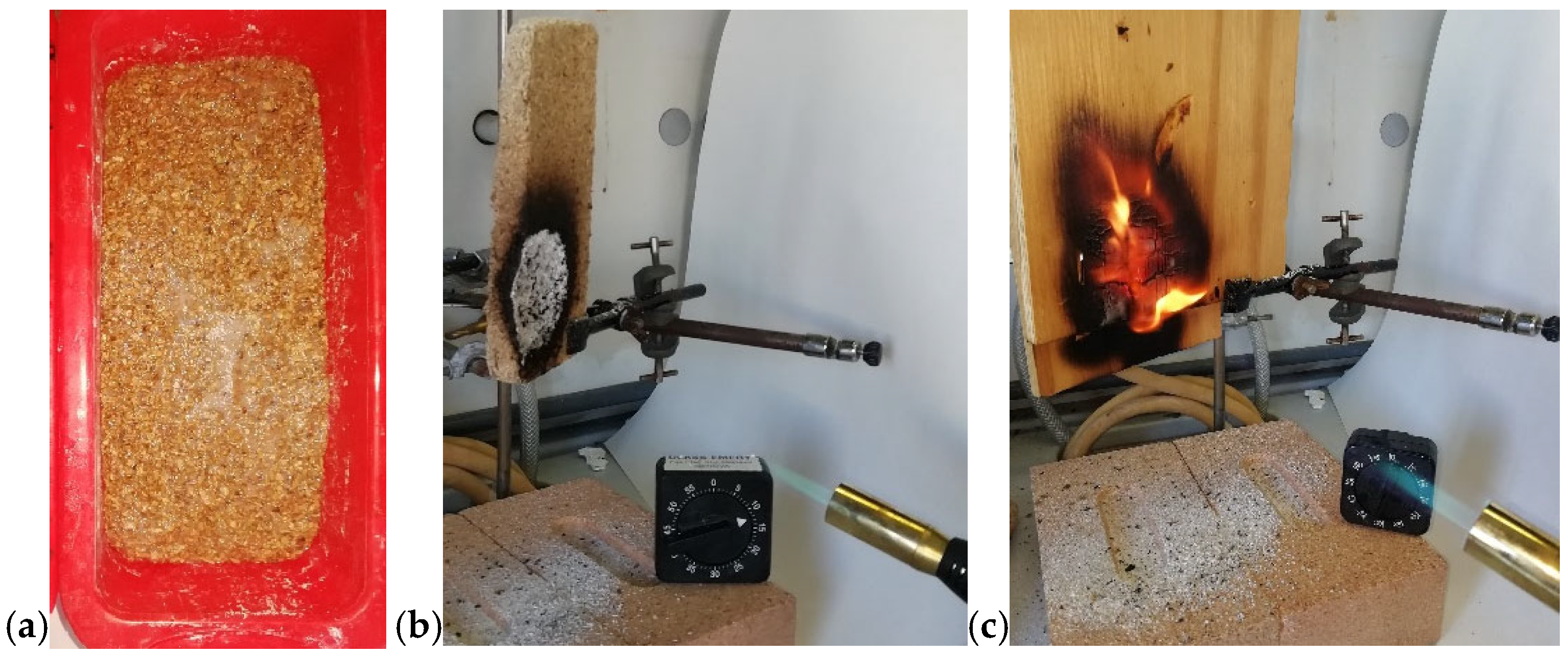

Although cork is a bio-based organic material, its hydrophobic nature and compact structure make it poorly biodegradable, posing challenges for end-of-life management. This limitation motivated the development of an MW-assisted strategy for its reuse. Accordingly, our research explored MW-assisted processes to produce sustainable bio-composite foams from cork-processing waste. In previous work [21], egg white proteins (EWP) were combined with cork granulates and subjected to MW foaming to produce lightweight, fire-resistant thermal insulating panels. In a subsequent study (the authors’ own unpublished data), acoustic insulating panels for partition walls were produced by adding mortar to the pre-foamed EWP-cork composite. The panels can be readily prepared using silicone molds, as shown in Figure 12a, and employed as fire-resistant insulating elements. Figure 12b shows the cork panel after the flame exposure. Unlike the wood panel, which ignites and sustains combustion (Figure 12c), the cork composite forms an oxidized residue—visible as a white powder on the bricks—that likely absorbs heat and detaches from the surface, thereby limiting flame propagation. This behavior enables the panel to withstand direct flame exposure for up to 20 min. This research aligns with the broader trend toward bio-based and recyclable materials, exemplified by the MW-assisted method for producing cellulose nanofibrils for high-performance composites [22]. The following subsection continues our focus on recycling strategies but shifts attention to a synthetic polymer system.

Figure 12.

(a) Silicone mold used for the MW-assisted sintering process of a cork panel; (b) the cork panel; (c) the wood panel exposed to an external flame (visible in the bottom-right corner of each image).

3.5. Microwaves-Assisted Sintering Process of rEPS-Based Geopolymer Composites for Civil Construction Applications

Beyond bio-based waste streams, MWH can also facilitate the valorization of synthetic waste streams. In this context, we investigated the MW-assisted expansion and sintering of virgin and recycled expanded polystyrene (EPS and rEPS) to produce lightweight geopolymer composites for construction applications [23].

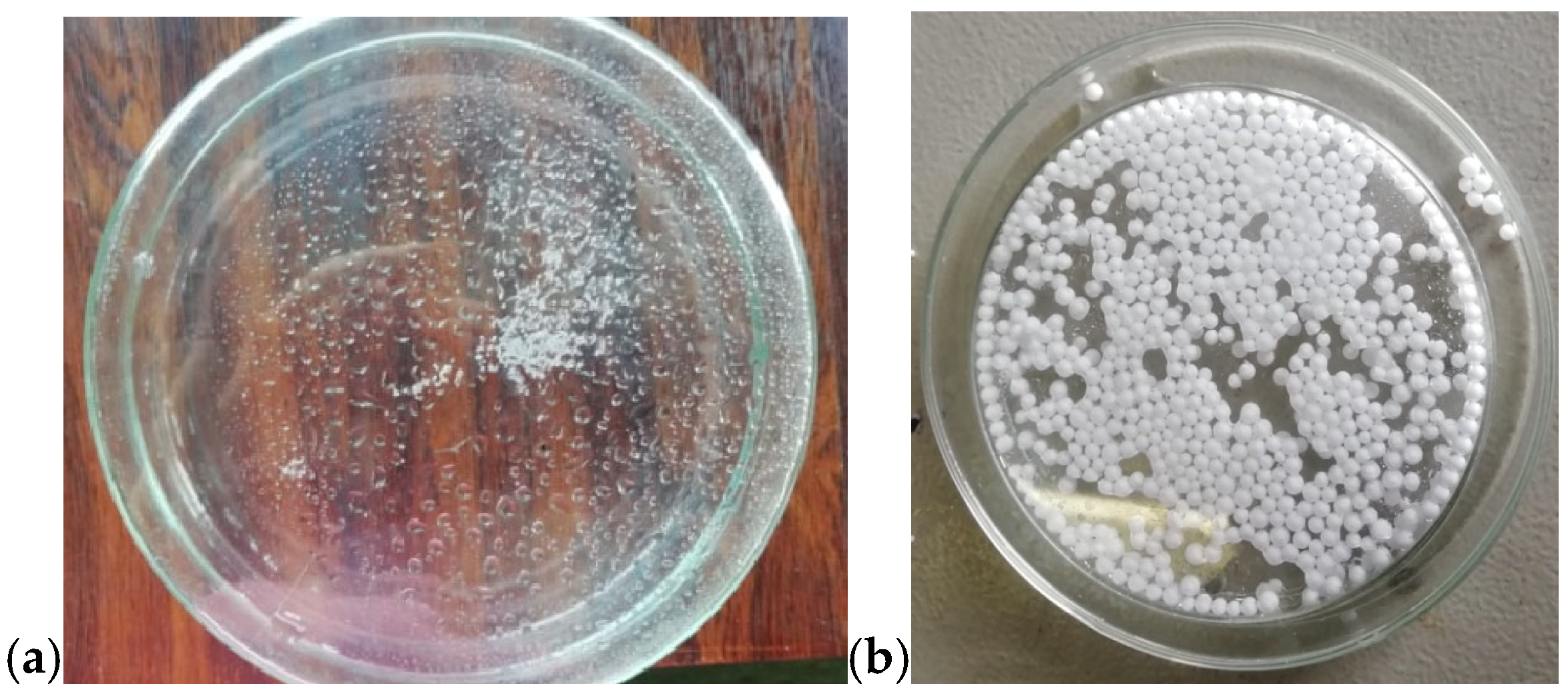

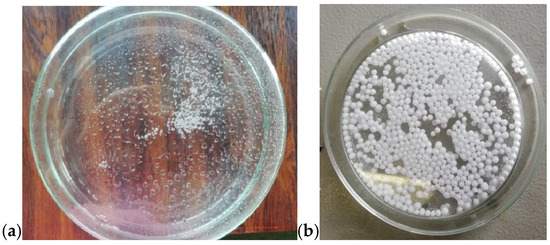

We first assessed the feasibility of expanding the EPS beads with microwave irradiation. As shown in Figure 13a, spraying the beads with water and subjecting them to a ten-minute MW heating at 90 W enabled their expansion, as illustrated in Figure 13b.

Figure 13.

EPS beads (a) before and (b) after the MW-assisted expansion process.

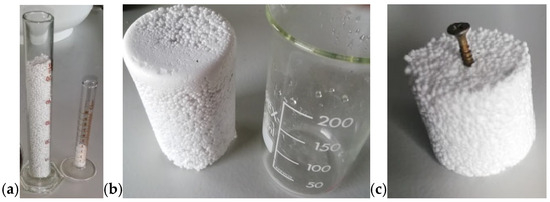

Subsequent tests confirmed that previously expanded beads—typically discarded during production due to defects—could not undergo further expansion, as the pentane blowing agent (bp = 36.1 °C) is fully volatilized during the initial treatment. We therefore evaluated the microwave-induced sintering of virgin and recycled beads. By spraying the 1:4 EPS–rEPS mixture with water and exposing it to microwaves for 10 min at 90 W, both expansion and sintering were achieved, as illustrated in Figure 14b. Figure 14a shows the mixture before and after free expansion, whereas Figure 14b,c depict the artefacts obtained under constrained expansion conditions, which promote bead sintering. Constrained expansion was achieved by placing an appropriate weight on top of the beaker.

Figure 14.

Volume occupied by EPS beads (a) before and (b,c) after the MW-assisted heating.

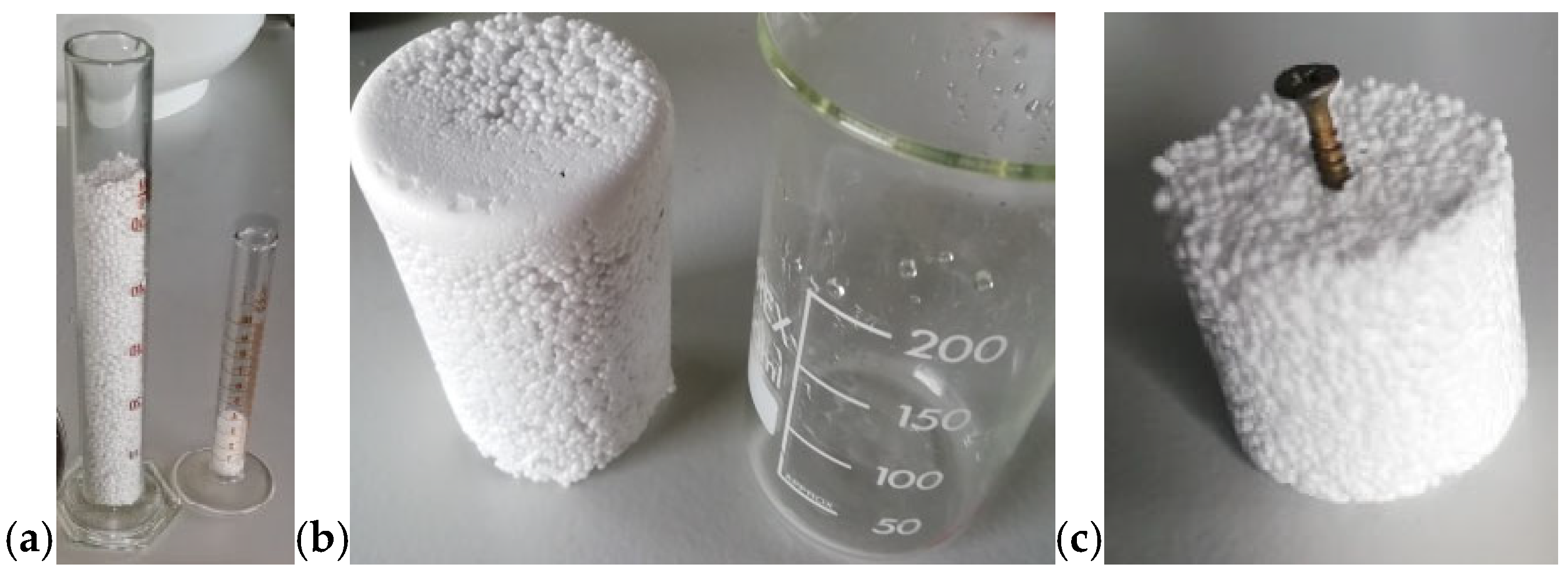

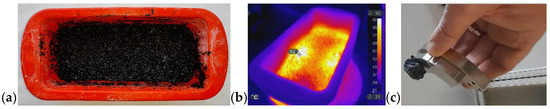

Figure 15a shows the rEPS-WG-Fe2SiO4 composite before MW sintering, while Figure 15b illustrates the process in progress. The temperature was maintained below 100 °C by operating at 90 W for 10 min, thereby preventing rEPS degradation. In addition to acting as an MW-active filler that promotes sintering, Fe2SiO4 also facilitates end-of-life recovery of the composite thanks to its magnetic properties. Because the iron silicate remains adhered to the rEPS particles even after the panel disintegrates during dismantling, a simple magnet can be used to prevent their dispersion into the environment and facilitate recovery and disposal. The project also explored the incorporation of CaCO3 and kaolin alongside WG and Fe2SiO4 to enhance both the mechanical and thermal resistance of the panels. As with the previously described cork panels, these composites also exhibit flame-resistant behavior. It is worth noting that both kaolin and CaCO3 may pose environmental concerns, as their disposal—typically via landfilling—can lead to significant ecological impacts. Kaolin is industrial waste from the ceramic sector, such as tiles, sanitary ware, and others, while calcium carbonate waste comes from the fishing industry and is the main constituent of mollusk shells. These results demonstrate that microwave heating can effectively induce both expansion and sintering in virgin EPS, whereas only sintering is achievable for rEPS. This capability enables its integration into geopolymer matrices and provides a sustainable pathway for its reuse.

Figure 15.

(a) Silicone mold containing the rEPS-WG-Fe2SiO4 composite; (b) IR image during the MW-assisted sintering process; (c) the composite adhering to an NdFeB magnet.

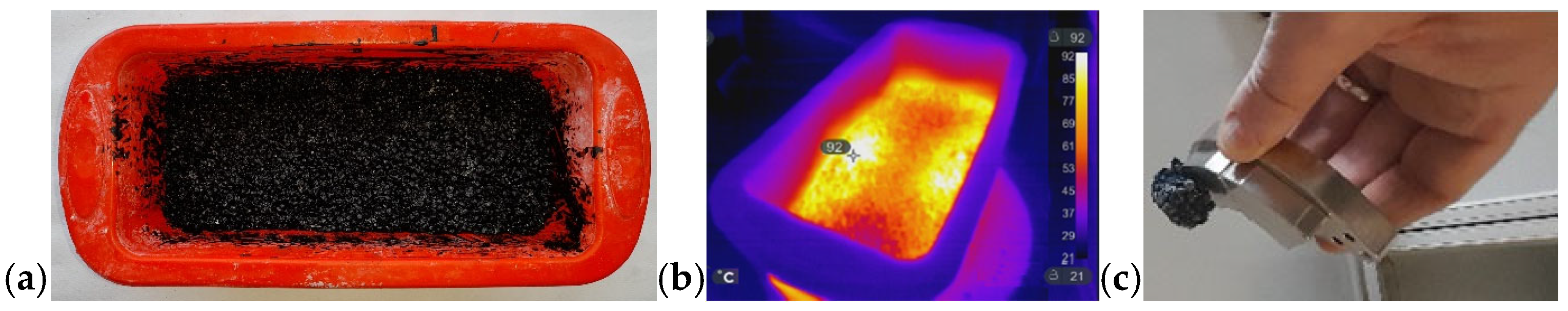

3.6. Microwave-Assisted Preparation of PVDF-BT Piezoelectric Composites

Continuing our focus on organic/inorganic composites, we next examine piezoelectric materials in which polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) acts as the polymer matrix and barium titanate (BT) is dispersed as the inorganic phase. The development of piezoelectric materials for energy storage and energy-harvesting applications—particularly PVDF/BT composites—represented another major research area at the CNR-SCITEC laboratory in Genoa [24,25,26,27,28]. To fabricate these composites, we introduced a solvent-free MW-assisted heating process followed by hot pressing (MWHP). This approach offers clear environmental advantages over conventional solvent-based methods. As reported in the literature, MW-assisted techniques have also been successfully applied to the preparation of other functional materials, such as perovskite oxides for solar cells and catalysts for clean energy applications [29,30,31,32,33].

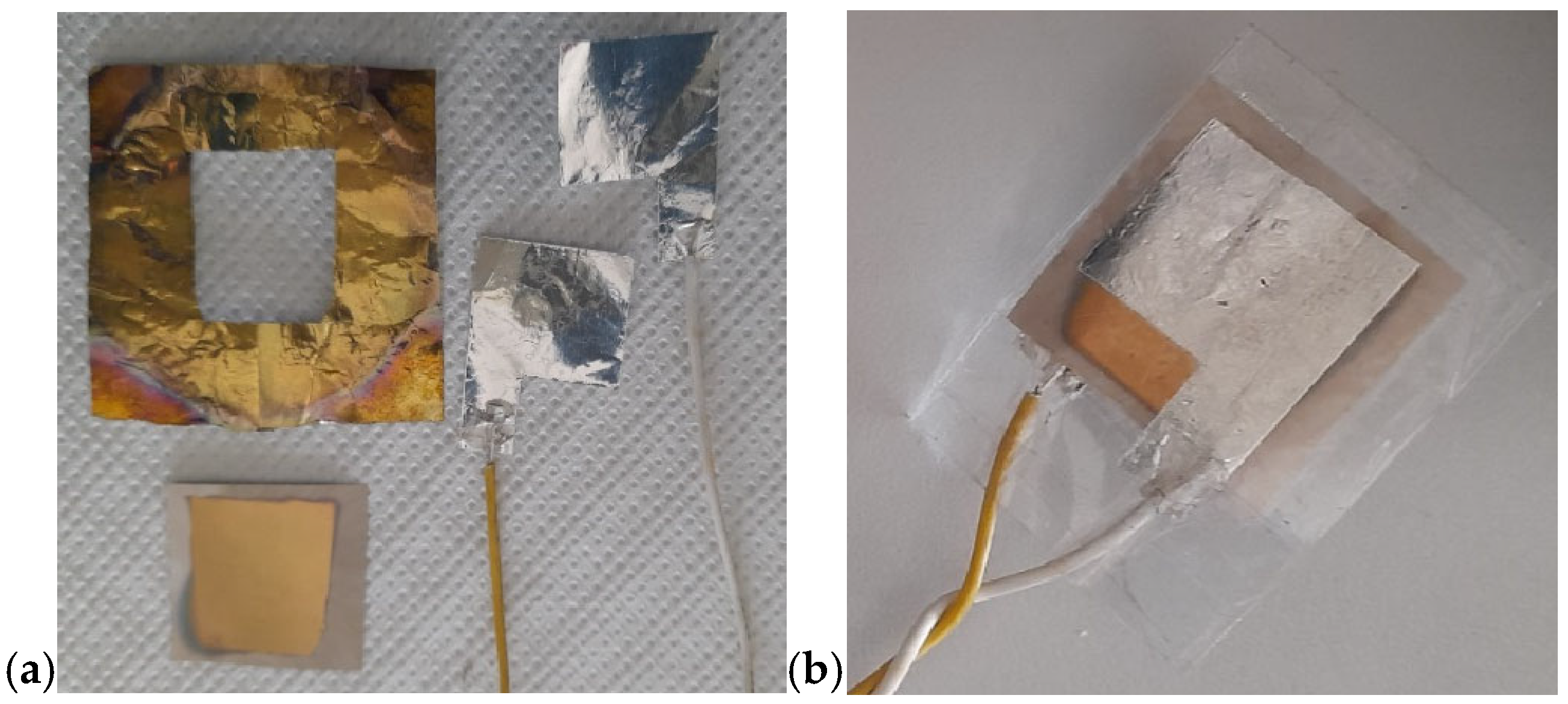

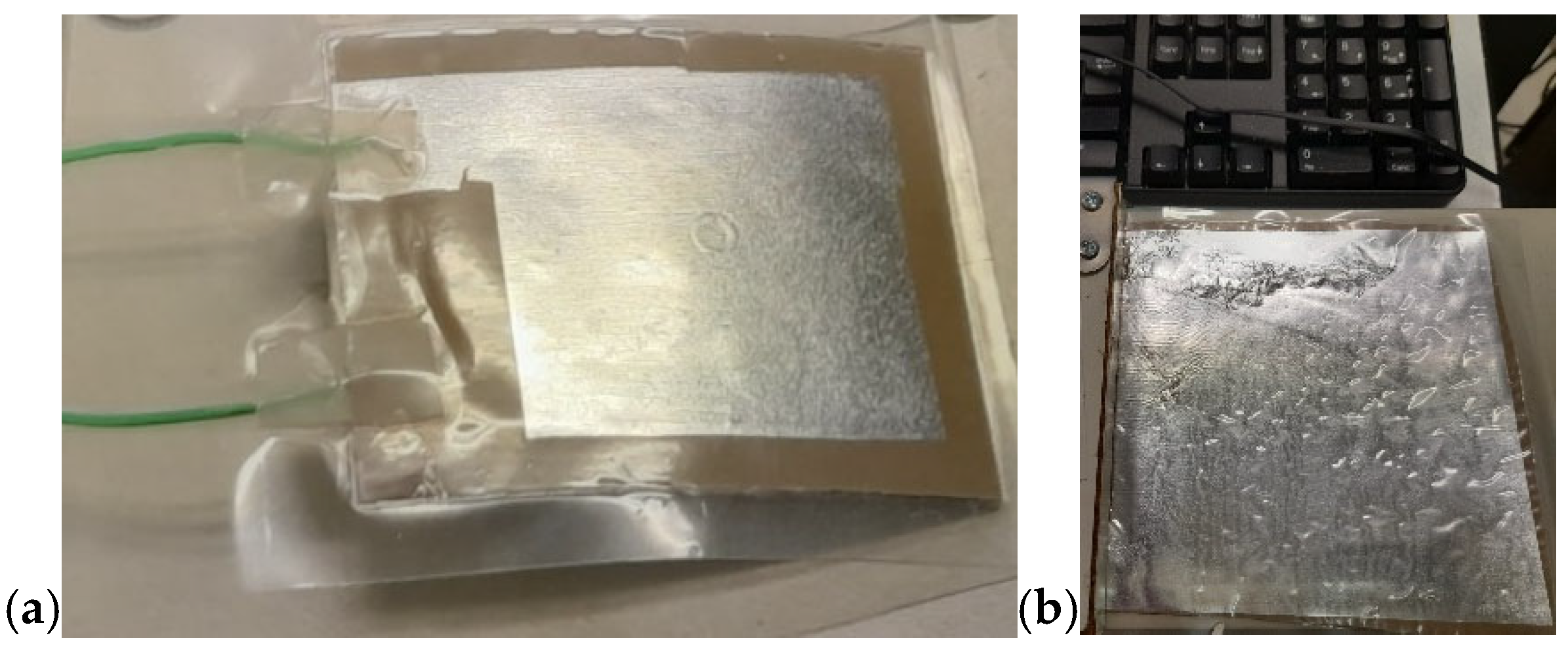

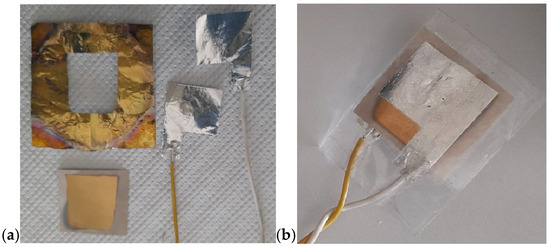

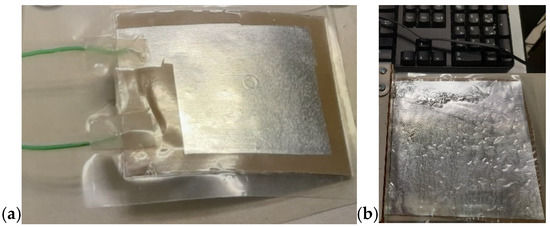

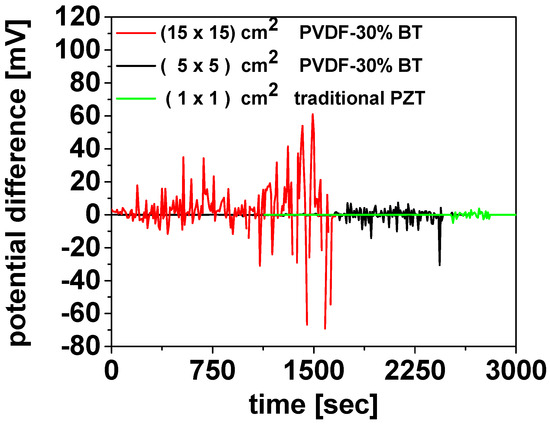

In this project—developed with a focus on environmental protection, human health, energy-saving, and atom economy—we demonstrated the feasibility of obtaining piezoelectric devices based on a composite containing 30 vol.% of BT dispersed in a PVDF matrix, processed via MW-assisted heating. Figure 16 shows the resulting devices. The composite was hot-pressed at 50 bar and 180 °C for 10 min to form a film, which was subsequently coated on both sides with Au by a sputtering process using a suitable mask. Electrical contacts were applied to each aluminum sheet using conductive silver paste. Figure 16a shows the device before assembly, while Figure 16b illustrates it after assembly. To preserve transparency, a transparent adhesive film was used in the assembly process. The final configuration of the device is shown in Figure 17. In this version, the device was assembled without Au sputtering, using only two Al foils as electrodes. Here, the adhesive film was replaced by wrapping the device in a resized A4 pouch and sealing it through a standard hot lamination process. The total thickness is approximately 100 µm, as the device consisted of three composite layers alternated with Al foils acting as electrodes in a parallel configuration. The device shown in Figure 17a measures approximately 5 cm × 5 cm, while the version of the device reported in Figure 17b measures 15 cm × 15 cm. The device in Figure 17b corresponds to a PVDF-BT monolayer. In both configurations, the Al foils were fixed to composite surfaces by hot pressing using a Colling press at 200 bar and 200 °C for 10 min. The devices were tested using a Pico Log TC-08 and exhibited a tribological activity, generating a potential difference of around 10–60 mV despite not having undergone poling.

Figure 16.

PVDF-piezoelectric composite device (a) before and (b) after assembly.

Figure 17.

Final configuration of the device: (a) three PVDF-BT layers alternating with four Al foils, assembled in parallel configuration (5 cm × 5 cm); (b) a single PVDF-BT layer with two Al foils (15 cm × 15 cm).

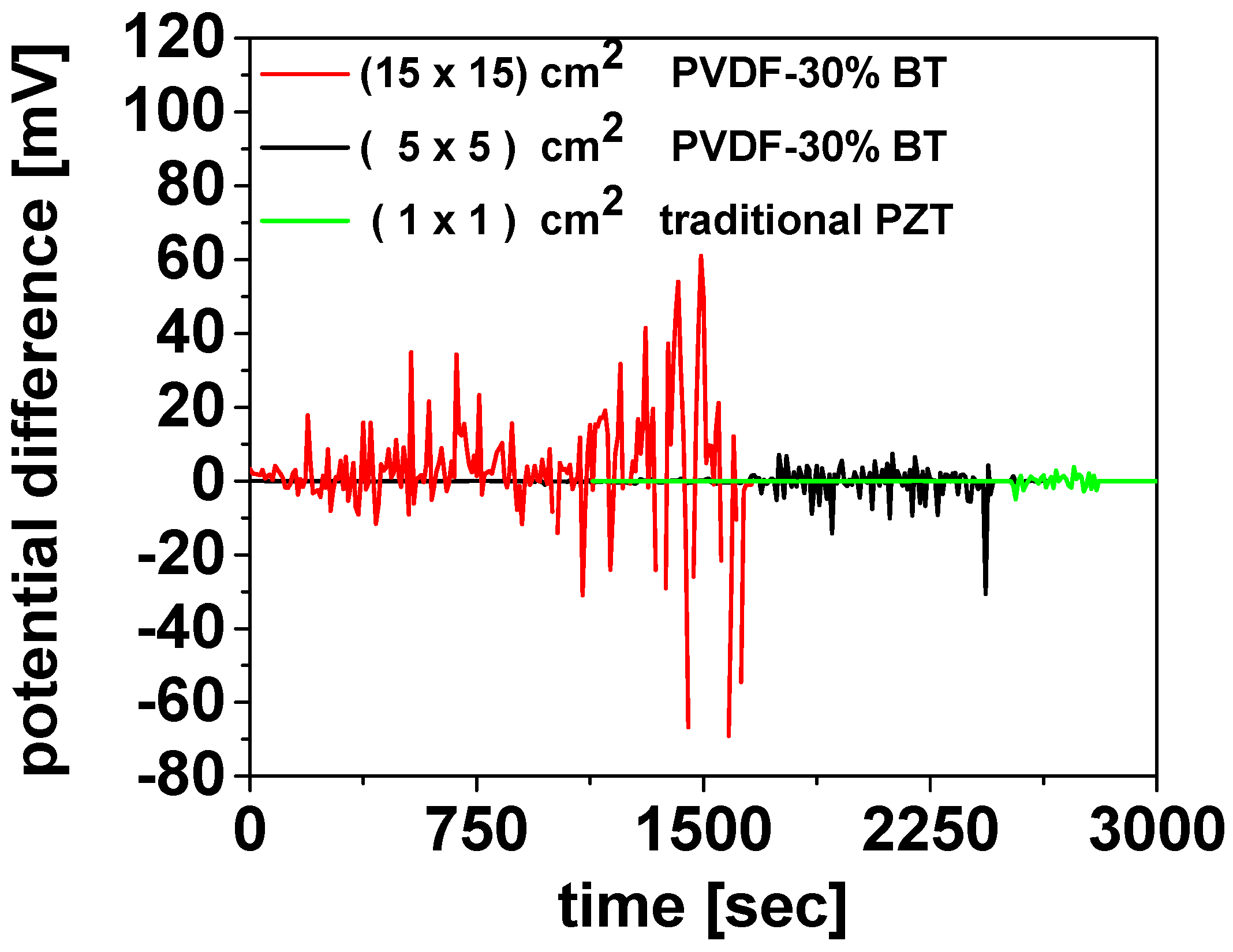

Figure 18 illustrates the electrical response of the piezoelectric devices under mechanical deformation. The voltage signal (mV) was recorded over time using a Pico Log TC-08 set to mV mode. To record the lead titanate zirconate (PZT) signal without saturating the Pico Log TC-08, a voltage divider was used to reduce the output. The resistive voltage divider circuit was assembled using two resistors, R1 and R2, connected in series between the sensor output and ground, where R1~999 R2. The attenuation factor follows Vout = Vin × ((R2)/(R1 + R2)), and consequently, Vout is attenuated by a factor of approximately 1000. Therefore, the maximum intensity signal of the green curve should be multiplied by a factor of 1000; for example, a measured value of 5 mV corresponds to an actual signal of 5 V. With this subsection, the use of WG as a binder for organic–inorganic composites concludes. In the next section, WG is employed again—this time solely as an inorganic binder, as in Section 3.1 and Section 3.2—to enable MW-assisted synthesis of the MgB2 phase.

Figure 18.

Potential difference measurements as a function of time for the PVDF-30%BT devices compared with a traditional lead titanate zirconate (PZT) device.

3.7. Microwave-Assisted Synthesis of the Superconductive MgB2 Phase

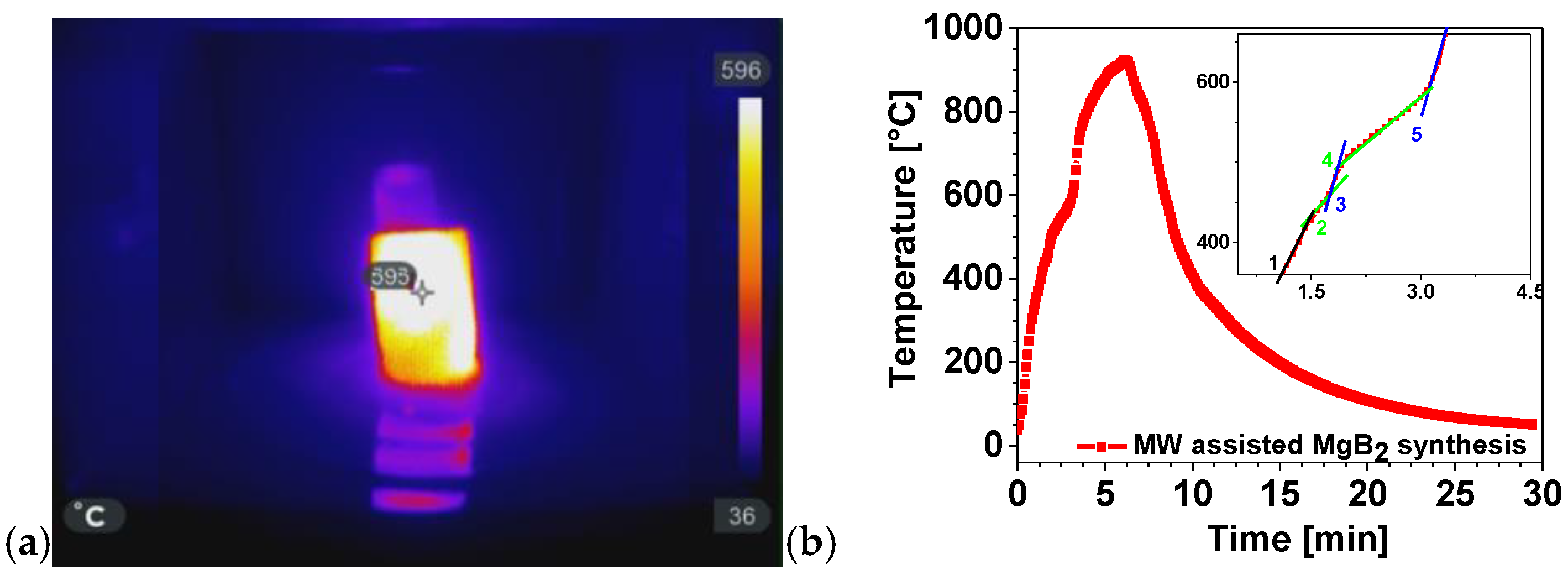

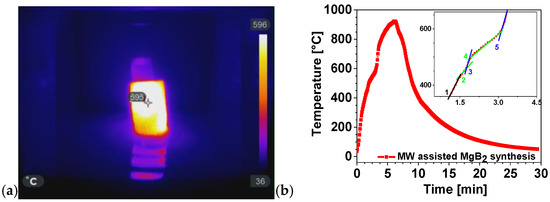

The versatility of MWH extends beyond polymeric and composite systems and can be exploited for the rapid synthesis of functional inorganic materials. In this context, we investigated the MW-assisted formation of magnesium diboride (MgB2), a technologically relevant superconductor, using an indirect (passive) heating approach, as previously discussed in Section 3.1 and Section 3.2. This method enables reaction conditions that are unattainable with conventional thermal techniques. Figure 19a shows the crucible temperature inside the MW oven at minute four, when the thermocouple recorded approximately 600 °C. To monitor the MWH process, the thermocouple was inserted through the opening normally occupied by the motor that rotates the glass. Removing the motor allowed the thermocouple to be positioned in direct contact with the crucible, enabling data acquisition using a Pico Log recorder.

Figure 19.

(a) IR image of the crucible inside the MW oven; (b) thermal profile of the MW-assisted MgB2 synthesis. The inset in panel (b) shows an enlarged view of the curve between minutes 1 and 5.

The thermocouple was not affected by MW radiation because the crucible, positioned above the insertion point, absorbed the MW and shielded the sensor. To capture the IR picture at minute four, the MW oven door was briefly opened. Remarkably, while the surrounding air temperature was approximately 40 °C, the crucible and powders inside reached 600 °C.

Figure 19b presents the temperature profile recorded during the MW-assisted synthesis of magnesium diboride (MgB2). Notably, a temperature of 922.8 °C is obtained in 6.2 min by reacting 4.5 g of diboron (B) with 5.5 g of magnesium (Mg). It is well known that Mg melts endothermically at 650 °C. Several slope variations are observed between minutes 1.5 and 4.5, including reductions in the heating rate (dT/dt) (green segments 2 and 4) and subsequent increase (blue segments 3 and 5). The black segment (1) corresponds to the initial heating stage, during which no significant events occur. Subsequent slope variations arise from the alternation between the endothermic melting of Mg and the exothermic formation of MgB2. Additionally, densification contributes to the process, as improved contact between MgB2 grains enhances heat transfer. Because the formation of MgB2 reaction is exothermic, the positive heat flux causes the temperature to increase until the reaction is finished at t = 6.2 min. Thus, the MW-assisted synthesis is complete in only 6 min.

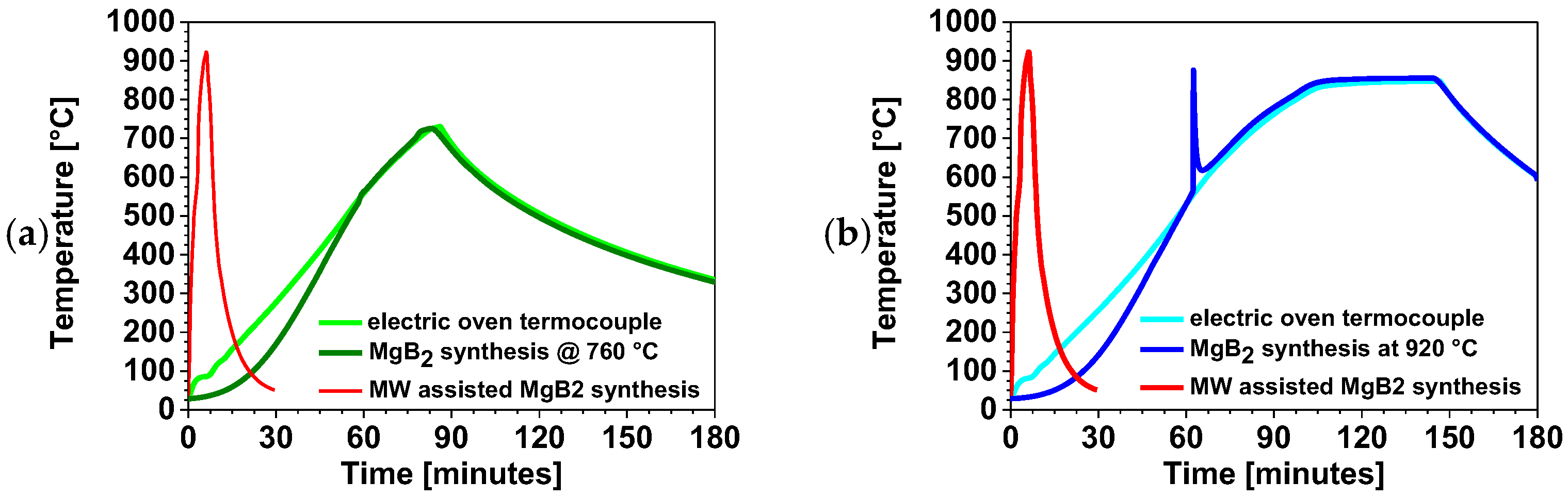

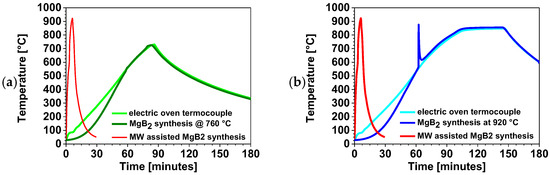

Figure 20 compares the thermal profile of the MW-assisted process with that of conventional MgB2 synthesis performed in an electric furnace [34] at (a) 720 °C and (b) 920 °C, corresponding to the respective reaction setpoint. The red curve represents the thermal profile of MW-assisted MgB2 synthesis. The light-green and cyan curves correspond to the thermocouples placed in empty crucibles and represent the thermal behavior of the electric furnace during the low-temperature synthesis (720 °C) and high-temperature synthesis (920 °C), respectively. The red and blue curves represent the thermal profiles of the synthesis of 10 g of MgB2, obtained by reacting 4.5 g of B and 5.5 g of Mg at nominal temperatures of 720 °C and 920 °C, respectively. The direct comparison in Figure 20 highlights the striking difference between the MW-assisted synthesis and the conventional one. The MW-assisted process is completed within 30 min, whereas the conventional low- and high-temperature syntheses reach only about 100 °C after the same time and remain at 338 °C and 608 °C, respectively, even after 3 h of cooling.

Figure 20.

Thermal profile of MW-assisted MgB2 synthesis compared with the same process carried out in an electrical furnace [34] at a (a) low temperature and (b) high temperature.

Interestingly, this project originated from a feasibility curiosity and was proposed for collaboration with a major producer of MgB2 wire, although the proposal was not pursued. Although MW-assisted MgB2 synthesis has been previously reported [35,36,37], the concept explored here is straightforward: placing the microwave oven inside a glove box would enable MgB2 production under a protective atmosphere, achieving rapid synthesis with low energy consumption and potentially scalable to kilogram quantities.

These preliminary results clearly demonstrate the remarkable efficiency of passive microwave heating for MgB2 synthesis, enabling temperatures above 900 °C and complete reaction within only a few minutes. Compared with conventional furnace processes, which require hours to reach similar conditions, the MW-assisted route represents a highly energy- and time-efficient alternative for producing superconducting powders, as well as other inorganic compounds requiring similarly high-temperature synthesis.

4. Future Developments and Market Demands

In accordance with the current literature ([38,39,40,41,42,43,44] and references therein), the innovative MW-assisted techniques developed at our laboratory have paved the way for the preparation of high-performance functional materials [11,12,13,16,21]. Future research should prioritize the optimization of these processes for a broader range of polymers and complex composite systems, while exploring their integration into high-tech sectors such as automotive, aerospace, and electronics. Moreover, coupling MW-assisted processing with additive manufacturing technologies—specifically 3D printing—could significantly enhance the versatility, precision, and scalability of material fabrication. A particularly promising frontier concerns the deployment of MWH for energy recovery and chemical upcycling of plastic waste. While several Northern European countries currently utilize waste-to-energy plants to convert municipal waste into heat and electricity [45], the combustion process inherently generates H2O and CO2, contributing to greenhouse emissions [46,47].

To mitigate this environmental impact, we propose investigating MW-assisted pyrolysis as a more sustainable alternative. Unlike conventional incineration, pyrolysis interrupts the thermal degradation pathway before final oxidation occurs, enabling the recovery of valuable energy carriers and chemical precursors, such as biochar, bio-oils, syngas (H2 and CO), and a range of hydrocarbons [48,49,50]. As demonstrated for biomass, MW-assisted pyrolysis [51] represents an energy-efficient strategy for managing plastic waste, offering a viable solution in regions where landfilling or incineration remains the primary disposal method [47].

Beyond waste management, MW technologies could revolutionize the decontamination and sterilization of personal protective equipment (PPE)—including medical tools, gowns, and masks. These polymeric items can be sterilized through MW-induced decontamination, thereby reducing the environmental footprint [52,53]. Remarkably, even customized microwave platforms can generate cold plasma under specific conditions, providing an accessible and effective sterilization route [54].

Additionally, MW-assisted extraction offers a superior alternative for recovering essential oils from biomass; by targeting water evaporation—an energy-intensive step-MWH significantly curtails processing time and energy demand [55,56].

Current market trends increasingly favor sustainable low-carbon technologies. The inherent ability of MW-assisted processes to minimize energy consumption and environmental impact positions them as highly attractive solutions for industries aiming to meet stringent regulatory requirements and consumer demand for “greener” products. Continuous R&D efforts will be essential to overcome existing limitations and expand the industrial scalability of MW-assisted processing.

5. Conclusions

This review has illustrated the fabrication of diverse innovative materials through microwave-assisted heating (MWH), emphasizing the versatility, efficiency, and sustainability of this transformative processing technology. The key findings from the long-term experimental activity at CNR-SCITEC Genova labs are summarized as follows:

- (a)

- Scalable Rotational Molding: The versatility of the MWH enabled the fabrication of polyethylene (PE) objects via laboratory-scale rotomolding, with a successful scale-up to industrial production. By utilizing an MW-active coating (WG and Fe2SiO4), a passive heating mode was established, allowing the polymer to melt via thermal conduction. This approach, validated by the ROPEVEMI Project, demonstrated compatibility with existing industrial infrastructure while significantly reducing energy consumption. Furthermore, the geopolymerization of the coating contributes to CO2 sequestration, enhancing the environmental profile of the process across various polymers, including PP, PVDF, and bioplastics such as Mater-Bi, PLA, and PBE;

- (b)

- Biomedical Scaffold: Bio-based scaffolds composed of water glass, hydroxyapatite, and egg white were successfully synthesized via MWH. In vitro biological analysis confirmed their biocompatibility and supported osteoblast growth, positioning MWH as a rapid and effective tool for tissue engineering applications;

- (c)

- Circular Economy and Waste Valorization: The MW-assisted sintering of rEPS was demonstrated, showing that both unsintered and pre-sintered beads can be effectively processed. The incorporation of inorganic fillers—such as iron silicate, calcium carbonate, and kaolin—not only improved mechanical performance but also enhanced the flame-retardant properties of the resulting composite panels;

- (d)

- Advanced Bio-composites: Sustainable bio-composite foams were produced using MW-transparent molds (Teflon, silicone). By utilizing egg white proteins as a matrix and cork granulates as the dispersed phase, a multimodal cellular structure was achieved. This study revealed that mechanical stiffness and thermal stability could be tuned by adjusting matrix-to-filler ratio and incorporating flame retardant additives such as CaCO3, kaolin, and Al(OH)3;

- (e)

- High-Performance Materials: Finally, MWH proved to be an environmentally friendly and energy-efficient route for producing piezoelectric BT-PVDF composites and the superconducting MgB2 phase. While dielectric performance requires further optimization, the scalability of this approach shows significant promise for energy harvesting and sensing technologies.

In conclusion, the results presented herein highlight the broad applicability of MWH as a “green” alternative to conventional thermal processing. As industrial demand for energy-efficient and sustainable manufacturing continues to rise, MWH is poised to play a pivotal role in the future of materials science, from plasma-based sterilization to the chemical upcycling of plastic waste through MW-assisted pyrolysis.

Funding

This work was supported by the Italian Ministry for Economic Development (MISE) within the framework of the “Accordo Innovazione DM 24/5/2017” call, with contributions from the POR-FESR 2014–2020 funds of Regione Liguria and Regione Lombardia for the research project “ROPEVEMI—Rotomoulding con PE verniciabile assistito da microonde” (Decree no. 1802 of 23/06/2021, project no. F/130066/01-05/X38). Furthermore, this research was supported by the European Union—NextGenerationEU and the Italian Ministry of University and Research (MUR) under the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP), Mission 4, Component 2, Investment 1.5, project “RAISE—Robotics and AI for Socio-economic Empowerment” (Grant No. ECS00000035).

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kumar, R.; Choudhary, H.K.; Pawar, S.P.; Mushtagatte, M.; Sahoo, B. Tailoring Microwave Absorption via Ferromagnetic Resonance and Quarter-Wave Effects in Carbonaceous Ternary FeCoCr Alloy/PVDF Polymer Composites. Microwave 2025, 1, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Wang, C.; Yin, X. A Review of Methods for Improving Microwave Heating Uniformity. Microwave 2025, 1, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, W.; Feng, X. Plasma cleaning under low pressures based on the domestic microwave oven. J. Microw. Power Electromagn. Energy 2021, 55, 128–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C. Microwave-A New Open Access Journal for Microwave Technologies. Microwave 2025, 1, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollmer, M. Physics of the microwave oven. Phys. Educ. 2004, 39, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, R.R.; Sharma, A.K. Microwave–material interaction phenomena: Heating mechanisms, challenges and opportunities in material processing. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2016, 81, 78–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valverde, C.; Rodríguez-García, M.M.; Rojas, E.; Bayon, R. State of the art of the fundamental aspects in the concept of microwave-assisted heating systems. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2024, 156, 107594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kremsner, J.M.; Kappe, C.O. Silicon Carbide Passive Heating Elements in Microwave-Assisted Organic Synthesis. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 71, 4651–4658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z.; Hassankiadeh, N.T.; Zhuang, Y.; Drioli, E.; Lee, Y.M. Crystalline polymorphism in poly(vinylidene fluoride) membranes. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2015, 51, 94–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Liu, Y.; Lv, H.; Shi, H.; Zhou, W.; Liu, Y.; Yu, D.-G. Processes of Electrospun Polyvinylidene Fluoride-Based Nanofibers, Their Piezoelectric Properties, and Several Fantastic Applications. Polymers 2022, 14, 4311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luciano, G.; Vignolo, M.; Brunengo, E.; Utzeri, R.; Stagnaro, P. Study of Microwave-Active Composite Materials to Improve the Polyethylene Rotomolding Process. Polymers 2023, 15, 1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vignolo, M.; Utzeri, R.; Luciano, G.; Buscaglia, M.T.; Bertini, F.; Porta, G.; Stagnaro, P. The ROPEVEMI Project: Industrial scale-up of a microwave-assisted rotational moulding process for sustainable manufacturing of polyethylene. J. Manuf. Proc. 2025, 146, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utzeri, R.; Vignolo, M.; Bertini, F.; Buscaglia, M.T.; Stagnaro, P. Improving Sustainability in Rotational Moulding Polymer Processing by Use of Microwave Heating. In AMPERE 2025; ProScience: Bari, Italy, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, H.; Li, N.; Zheng, M.; Qiu, L.; Zhang, S.; Zheng, J.; Ji, G.; Cao, J. Microwave-assisted synthesis of graphene–SnO2 nanocomposite for rechargeable lithium-ion batteries. Mater. Lett. 2014, 115, 125–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawelski, D.; Plonska-Brzezinska, M.E. Microwave-Assisted Synthesis as a Promising Tool for the Preparation of Materials Containing Defective Carbon Nanostructures: Implications on Properties and Applications. Materials 2023, 16, 6549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luciano, G.; Vignolo, M.; Galante, D.; D’Arrigo, C.; Furlani, F.; Montesi, M.; Panzeri, S. Designing and Manufacturing of Biocompatible Hydroxyapatite and Sodium Trisilicate Scaffolds by Ordinary Domestic Microwave Oven. Compounds 2024, 4, 106–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikder, P.; Ren, Y.; Bhaduri, S.B. Microwave processing of calcium phosphate and magnesium phosphate based orthopedic bioceramics: A state-of-art review. Acta Biomater. 2020, 111, 29–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilyas, K.; Qureshi, S.W.; Afzal, S.; Gul, R.; Yar, M.; Kaleem, M.; Khan, A.S. Microwave-assisted synthesis and evaluation of type 1 collagen–apatite composites for dental tissue regeneration. J. Biomater. Appl. 2018, 33, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Haibel, A.; Görke, O.; Fleck, C. Microwaves speed up producing scaffold foams with designed porosity from water glass. Mater. Des. 2022, 222, 111100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Zhang, X.; Wu, B.; Huang, W. Effects of microwave sintering on the properties of porous hydroxyapatite scaffolds. Ceram. Int. 2013, 39, 2389–2395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luciano, G.; Vignali, A.; Vignolo, M.; Utzeri, R.; Bertini, F.; Iannace, S. Biocomposite Foams with Multimodal Cellular Structures Based on Cork Granulates and Microwave Processed Egg White Proteins. Mater. Adv. Compos. 2023, 16, 3063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.M.; Wang, Y.L.; Ma, M.G.; Zhu, J.F.; Sun, R.C.; Xu, F. Microwave-assisted method for the synthesis of cellulose-based composites and their thermal transformation to Mn2O3. Ind. Crops Prod. 2013, 43, 751–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikary, S.K.; Hashish, D.K. Turning waste expanded polystyrene into lightweight aggregate: Towards sustainable construction industry. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 837, 155852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrovic, M.V.; Craciun, F.; Cordero, F.; Mercadelli, E.; Ilic, N.; Despotovic, Z.; Bobic, J.; Dzunuzovic, A.; Galassi, C.; Stagnaro, P.; et al. Advantages and limitations of active phase silanization in PVDF composites: Focus on electrical properties and energy harvesting potential. Polym. Compos. 2024, 45, 4428–4446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craciun, F.; Cordero, F.; Mercadelli, E.; Ilic, N.; Galassi, C.; Baldisserri, C.; Bobic, J.; Stagnaro, P.; Canu, G.; Buscaglia, M.T.; et al. Flexible composite films with enhanced piezoelectric properties for energy harvesting and wireless ultrasound-powered technology. Compos. Part B Eng. 2023, 263, 110835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrovic, M.V.; Cordero, F.; Mercadelli, E.; Brunengo, E.; Ilic, N.; Galassi, C.; Despotovic, Z.; Bobic, J.; Dzunuzovic, A.; Stagnaro, P.; et al. Flexible lead-free NBT-BT/PVDF composite films by hot pressing for low energy harvesting and storage. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 884, 161071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunengo, E.; Conzatti, L.; Schizzi, I.T.; Buscaglia, M.; Canu, G.; Curecheriu, L.; Costa, C.; Castellano, M.; Mitoseriu, L.; Stagnaro, P.; et al. Improved dielectric properties of poly(vinylidene fluoride)–BaTiO3 composites by solvent-free processing. J. Polym. Sci. 2020, 138, 50049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheorghiu, F.; Stanculescu, R.; Curecheriu, L.; Brunengo, E.; Stagnaro, P.; Tiron, V.; Postolache, P.; Buscaglia, M.T.; Mitoseriu, L. PVDF-ferrite composites with dual magneto-piezoelectric response for electronics applications: Synthesis and functional properties. J. Mater. Sci. 2020, 55, 3926–3939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feria, D.N.; Su, J.-W.; Wu, G.-H.; Zeng, Y.-T.; Lian, J.-T.; Lin, T.-Y. Revealing the enhanced crystalline quality mechanism of perovskites produced by microwave-assisted synthesis: Toward the fabrications in a fully ambient air environment. Mater. Today Sustain. 2023, 24, 100532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Lü, X.; Shu, H.; Xe, J.; Zhang, H. Microwave-assisted synthesis of perovskite ReFeO3 (Re: La, Sm, Eu, Gd) photocatalyst. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2010, 171, 31–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prado-Gonjal, J.; Schmidt, R.; Morán, E. Microwave-Assisted Routes for the Synthesis of Complex Functional Oxides. Inorganics 2015, 3, 101–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canpolat, G. Microwave-assisted sumac-based biocatalyst synthesis for effective hydrogen production. J. Aust. Ceram. Soc. 2024, 60, 681–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuli, V.; Luo, C.; Robinson, B.; Hu, J.; Wang, Y. Microwave-assisted catalytic technology for sustainable production of valuable chemicals from plastic waste with enhanced catalyst reusability. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 489, 151551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vignolo, M.; Romano, G.; Nardelli, D.; Bellingeri, E.; Martinelli, A.; Bitchkov, A.; Bernini, C.; Malagoli, A.; Braccini, V.; Ferdeghini, C. In situ high-energy synchrotron x-ray diffraction investigation of phase formation and sintering in MgB2 tapes. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 2011, 24, 065014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostino, A.; Volpe, P.; Castiglioni, M.; Truccato, M. Microwave Synthesis of MgB2 Superconductor. Mater. Res. Innov. 2004, 8, 75–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, C.; Guo, J.; Fu, G.C.; Yang, L.H.; Chen, H. Rapid preparation of MgB2 superconductor using hybrid microwave synthesis. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 2004, 17, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Q.; Yi, J.; Peng, Y.; Luo, S.; Li, L. Microwave direct synthesis of MgB2 superconductor. Mater. Lett. 2008, 62, 4006–4008. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, K.; Shu, Y.; Li, F.; Peng, G. Bimetallic catalysts as electrocatalytic cathode materials for the oxygen reduction reaction in microbial fuel cell: A review. Green Energy Environ. 2023, 8, 1043–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makul, N.; Rattanadecho, P.; Agrawal, D.K. Applications of microwave energy in cement and concrete—A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 37, 715–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagunas-Chavarría, A.; Navarro-Rojero, M.G.; Salvador, M.D.; Benavente, R.; Catalá-Civera, J.M.; Borrell, A. Effect of Microwave-Assisted Synthesis and Sintering of Lead-Free KNL-NTS Ceramics. Materials 2022, 15, 3773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nemala, S.S.; Ravulapalli, S.; Mallick, S.; Bhargava, P.; Bohm, S.; Bhushan, M.; Thakur, A.K.; Mohapatra, D. Conventional or Microwave Sintering: A Comprehensive Investigation to Achieve Efficient Clean Energy Harvesting. Energies 2020, 13, 6208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubair, M.; Ferrari, R.; Alagha, O.; Mu’azu, N.D.; Blaisi, N.I.; Ateeq, I.S.; Manzar, M.S. Microwave Foaming of Materials: An Emerging Field. Polymers 2020, 12, 2477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mischinenko, V.; Vasilchenko, A.; Lazorenko, G. Effect of Waste Concrete Powder Content and Microwave Heating Parameters on the Properties of Porous Alkali-Activated Materials from Coal Gangue. Materials 2024, 17, 5670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun-fang, X.; Bing, H. Preparation of porous silicon nitride ceramics by microwave sintering and its performance evaluation. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2018, 8, 5984–5995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Interactive Map of Waste-to-Energy Plants. Available online: https://www.cewep.eu/interactive-map/ (accessed on 17 December 2025).

- Nordic Council of Ministers Waste Incineration in the Nordic Countries—A Status Assessment with Regard to Emissions and Recycling. Available online: https://pub.norden.org/temanord2024-524 (accessed on 17 December 2025).

- ESWET European Suppliers of Waste-To-Energy Technology Waste-to-Energy 2050 Clean Technologies for Sustainable Waste Management. Available online: www.eswet.eu (accessed on 17 December 2025).

- Li, J.; Dai, J.; Liu, G.; Zhang, H.; Gao, Z.; Fu, J.; He, Y.; Huang, Y. Biochar from microwave pyrolysis of biomass: A review. Biomass Bioenergy 2016, 94, 228–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohi, S.P.; Krull, E.; Lopez-Capel, E.; Bol, R. Chapter 2—A Review of Biochar and Its Use and Function in Soil. Adv. Agron. 2010, 105, 47–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zama, E.F.; Reid, B.J.; Arp, H.P.H.; Sun, G.-X.; Yuan, H.-Y.; Zhu, Y.-G. Advances in research on the use of biochar in soil for remediation: A review. J. Soil Sediments 2018, 18, 2433–2450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahari, W.A.W.; Kee, S.H.; Foong, S.Y.; Amelia, T.S.M.; Bhubalan, K.; Man, M.; Yang, Y.; Ong, H.C.; Vithanage, M.; Lam, S.S.; et al. Generating alternative fuel and bioplastics from medical plastic waste and waste frying oil using microwave co-pyrolysis combined with microbial fermentation. Renew. Sustain. Energy 2022, 153, 111790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laroussi, M. Cold Plasma in Medicine and Healthcare: The New Frontier in Low Temperature Plasma Applications. Front. Phys. 2020, 8, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, S.; Caiola, A.; Bai, X.; Lalsare, A.D.; Hu, J. Microwave Plasma-Enhanced and Microwave Heated Chemical Reactions. Plasma Chem. Plasma Process. 2020, 40, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamri, A.A.; Ong, M.Y.; Nomanbhay, S.; Show, P.L. Microwave plasma technology for sustainable energy production and the electromagnetic interaction within the plasma system. Environ. Res. 2021, 197, 111204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tigrine-Kordjani, N.; Meklati, B.Y.; Chemat, F. Microwave ‘dry’ distillation as an useful tool for extraction of edible essential oils. Int. J. Aromather. 2006, 16, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micalizzi, G.; Alibrando, F.; Vento, F.; Trovato, E.; Zoccali, M.; Guarnaccia, P.; Dugo, P.; Mondello, L. Development of a Novel Microwave Distillation Technique for the Isolation of Cannabis sativa L. Essential Oil and Gas Chromatography Analyses for the Comprehensive Characterization of Terpenes and Terpenoids, Including Their Enantio-Distribution. Molecules 2021, 26, 1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.