1. Introduction

The escalating global health crisis of cognitive decline and dementia, most notably Alzheimer’s disease (AD), the most common and debilitating form, affects millions of individuals worldwide. These progressive neurodegenerative disorders reduce quality of life and impose growing burdens on families, caregivers, and healthcare systems [

1]. While AD’s pathophysiology has been widely studied, current therapeutic strategies remain limited in their ability to prevent or reverse neurodegeneration. This makes the identification of modifiable risk factors a pressing public health priority.

Benzodiazepines (BZDs), widely prescribed for their anxiolytic, sedative, and muscle relaxant properties, have drawn increased scrutiny for their potential long-term impact on cognition. Their prevalent use—particularly among older adults who are already at increased risk of cognitive decline—raises important clinical and epidemiological concerns. While “Z-drugs” (e.g., zolpidem, zopiclone, and eszopiclone) also act as benzodiazepine receptor agonists at the gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA)A complex, they differ structurally and pharmacokinetically from traditional BZDs; our review focuses primarily on BZDs themselves, given their longer history of use and the larger body of epidemiologic evidence. A potential association between BZD exposure and cognition could represent a modifiable factor, contingent on further clarification of the evidence.

Several systematic and narrative reviews have previously examined this question. Some have reported associations between long-term BZD use and increased dementia risk, often emphasizing factors such as dose, duration, or half-life [

2,

3]. However, these reviews often aggregate studies with divergent methodologies and outcome definitions, and few provide granular analysis of study-level confounding, temporality, or measurement bias. Others have concluded that the evidence remains inconclusive, citing insufficient control for reverse causality, protopathic bias, or baseline cognitive status [

4,

5]. As such, the current state of the literature is marked by inconsistency, with existing reviews providing valuable summaries but limited resolution of the underlying methodological differences that may drive conflicting results.

This systematic review aims to build on prior work by critically evaluating studies of BZD exposure and cognitive outcomes through a design-focused lens. Adhering to PRISMA 2020 guidelines, we conducted a comprehensive search of PubMed and Google Scholar for studies published between 2010 and 2025, including observational studies, randomized controlled trials, and cross-sectional studies. Eligible studies assessed cognitive performance or dementia incidence in community-dwelling adult populations. Rather than advancing a singular conclusion, this review emphasizes the design characteristics that may underlie the field’s heterogeneity, including inclusion/exclusion criteria, operational exposure definitions, outcome measures, follow-up duration, confounder control, and study setting. In doing so, we aim to clarify why this research question remains unresolved, outline methodological challenges that impede interpretation, and suggest directions for future research that can more effectively inform clinical decision-making and BZD prescribing practices in cognitively vulnerable populations.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Protocol

We conducted a systematic review of primary studies that investigated the association between benzodiazepine exposure and subsequent cognitive decline or dementia. The review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 statement [

6]. The protocol was prospectively developed and followed throughout the review. This review has been registered in PROSPERO (CRD420251173919).

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

Inclusion criteria: community-dwelling adults of any age; human observational or interventional studies (cohort, case–control, cross-sectional, or randomized controlled trials); outcomes that included at least one cognitive measure or a diagnosis of dementia or Alzheimer’s disease; and articles published in English between 2010 and 2025. Exclusion criteria: institutionalized populations; outcomes unrelated to cognition such as sleep quality or frailty; non-human or in vitro studies; primary psychiatric diagnoses other than anxiety or insomnia such as bipolar disorder or ADHD; cohorts limited to military, traumatic brain injury, or PTSD; case reports, editorials, letters, protocols, conference abstracts, or non-peer-reviewed literature; or systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

2.3. Search Strategy

We searched PubMed and Google Scholar from 1 January 2010 to 30 April 2025. The search string was: (benzodiazepine* OR BZD OR alprazolam OR lorazepam OR diazepam OR clonazepam) AND (cognitive decline OR cognitive impairment OR cognition OR memory loss OR executive function OR mild cognitive impairment OR MCI OR dementia OR Alzheimer* disease). The last search of all databases was conducted on 1 July 2025. In addition, reference lists of eligible articles were hand-searched to identify additional studies. No filters other than human studies and English language were applied. Articles were reviewed by screening the titles and abstracts, and then full-text analysis was done as a second step.

2.4. Study Selection

One reviewer (AB) independently screened titles and abstracts and then full texts, and compiled a list of included studies. NK and HH reviewed, and any disagreements were resolved by consensus among all three reviewers to minimize bias. The PRISMA flow diagram in

Figure 1 shows that 1010 unique records were screened, 931 were excluded at the title and abstract stage, 79 full texts were assessed, and 62 were excluded with reasons based on the study’s inclusion and exclusion criteria and data extractability. Finally, a total of 17 studies were included in the qualitative synthesis.

2.5. Data Extraction

AB independently extracted the following information from eligible studies: objective, study design, exposure definition, number of participants, demographics, follow-up period, analysis methods, findings, effect size, standard error, outlying confounders, and comorbidities. NK and HH divided the articles between them and independently checked the extracted data. Any discrepancies were resolved through discussion among AB, NK, and HH.

Specifically, we first identified the primary outcomes associated with BZD use in each included study, along with the corresponding test statistics. Outcomes for cohort studies included cognitive decline and/or incident dementia. For cohort studies examining cognitive decline, the primary outcome was whether the rate of decline differed between groups, indicating a significant interaction effect. For studies that did not assess an interaction effect but instead focused on the main effect of the group indicator, we extracted the corresponding test statistics. For incident dementia, the primary outcome was the contrast in hazard ratios or incidence rate ratio between groups. In case–control studies, we examined the odds of incident dementia associated with BZD use, while in cross-sectional studies, the primary outcome was the difference in cognitive performance between groups. This review did not include a quantitative synthesis or meta-analysis; therefore, no assumptions were made regarding missing information required for data imputation.

2.6. Assessment of Risk of Bias

Although we did not apply a formal risk of bias tool to the included studies, we considered key sources of bias, such as control for baseline cognition, adjustment for comorbidities, handling of prodromal symptoms, operational definition of BZD exposure, and follow-up period.

2.7. Classification of Strength of Association

We then classified the strength of association of all studies into no association, moderate association, and strong association with dementia or cognitive decline. A strong association was defined as one supported by a statistically significant p-value (p < 0.05) for the entire study cohort, corresponding to a hazard ratio (HR), odds ratio (OR) or incidence rate ratio (IRR) greater than 1.0 and a 95% confidence interval not crossing 1.0 for Cox proportional hazard, logistic, and Poisson regression models, respectively. A moderate association was defined as significance observed only in subgroup analyses.

2.8. PRISMA 2020 Checklists Not Applicable to This Review

This review did not include a quantitative synthesis or meta-analysis; therefore, methods related to data preparation for synthesis (e.g., handling missing summary statistics or data conversions), statistical pooling, heterogeneity assessment (e.g., subgroup analyses or meta-regression), and sensitivity analyses were not applicable. Similarly, no formal methods were applied to assess risk of bias arising from missing results or reporting biases in a statistical synthesis, nor to evaluate the certainty or confidence in a body of evidence for a particular outcome.

Furthermore, formal assessments of certainty or confidence in the body of evidence were not performed. Instead, the strength and reliability of the evidence were considered qualitatively, taking into account study design, adjustment for confounders, risk of bias, consistency of findings across studies, and applicability to the target population. Study characteristics, outcomes, and methodological limitations were reviewed narratively, and potential sources of bias or inconsistency were discussed descriptively rather than through quantitative methods.

3. Results

Our database searches identified 956 records from PubMed, 1006 from Google Scholar, and 4 from other sources. After removing 956 duplicate records, 1010 unique records were screened by title and abstract. Of these, 931 were excluded. The full text of 79 reports was reviewed, and 62 were excluded for the following reasons: 10 examined non-community-dwelling populations (e.g., nursing home or inpatient samples), 34 focused on outcomes outside of cognition or dementia (e.g., functional status only), 6 were non-human studies misclassified by abstract, 10 lacked extractable or quantifiable data, and 2 were duplicate data sources or overlapping cohorts. Seventeen studies ultimately met the inclusion criteria and were included in the qualitative synthesis. The PRISMA flow diagram illustrating the study selection process is provided in

Figure 1.

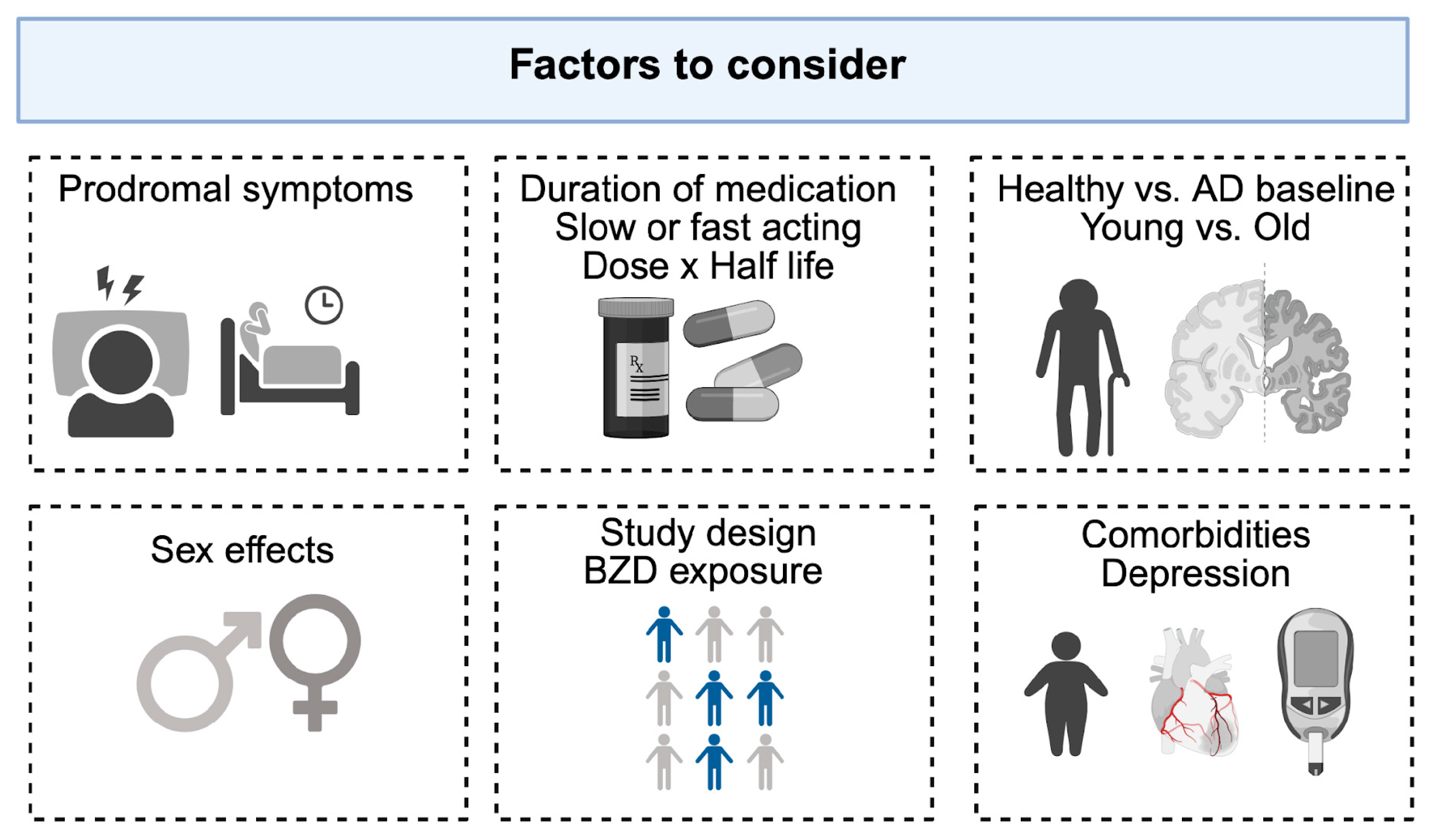

Throughout the review, we observed substantial heterogeneity across studies. Several factors appeared to contribute to these inconsistencies, including study design, operational definitions of exposure, consideration of protopathic bias, sex differences, drug- or dose-specific categories (e.g., long- vs. short-acting, high vs. low dose), and adjustment for concomitant comorbidities. These factors are illustrated in

Figure 2.

3.1. Study Design

Among the 17 included studies, four employed a case–control design [

7,

8,

9,

10]. These studies stratified participants into dementia cases and controls and then compared BZD use. Some case–control studies excluded a certain period of exposures occurring during prodromal phases, thereby attempting to reduce reverse causation bias [

9,

10]. Tapiainen applied a 5-year lag period, while Biétry applied a 2-year lag period. Specifically, Bietry et al. examined the association between benzodiazepine use and dementia risk both with and without adjustment for prodromal symptoms. They found that the initially observed association became non-significant after this adjustment. These findings suggest that accounting for lag time or prodromal symptom onset can substantially attenuate the observed association between benzodiazepine exposure and dementia risk.

Of four studies, three [

7,

8,

9] reported higher BZD use among dementia patients than among controls. One study [

11] cross-sectionally compared cognitive outcomes in long-term BZD users to normative data from cognitively healthy controls matched on age, sex, and education and reported significantly lower performance on all cognitive domains among long-term BZD users.

The remaining 12 were cohort studies: seven prospective [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18] and five retrospective [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. Findings from the 12 cohort studies were highly heterogeneous. Some studies reported overall associations in the entire cohort, such as increased risk of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) [

17]. Most studies found associations only in specific contexts—for example, dementia with high cumulative doses [

12], minimal doses [

18], short half life BZDs at high doses in women [

22], and long half life BZDs [

15], a functional decline with concurrent antidepressant use [

13], decreased delayed recall among women only [

19], or lower baseline cognition without accelerated decline [

16,

21]. By contrast, three studies [

14,

20,

23] found no association at all.

As study design varied, the operational definitions of BZD exposure also differed substantially. Some studies classified exposure based on baseline or participants’ prior history of use up to baseline [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16], whereas others classified participants by examining the entire BZD use at baseline and during follow-up, for example, “ever exposed” versus “never exposed” [

19,

21,

22,

23] or incorporating BZD use as a time-varying covariate [

17,

18]. Follow-up durations also differed widely, ranging from 18 months to 10 years; three studies [

20,

21,

23] had mean follow-up periods shorter than five years.

3.2. Differences in Age, Comorbidities, Medications, and Cognition at Baseline

Age at baseline and comorbidities consistently influenced reported associations between BZD exposure and cognitive outcomes. Most large longitudinal cohorts primarily enrolled older adults (mean age > 65 years). The presence of comorbid medical conditions (such as depression, anxiety, or chronic insomnia) was variably addressed among the included articles. Specifically, seven studies [

7,

13,

14,

15,

17,

18,

19] accounted for depression or depressive symptoms while others did not. Two studies [

11,

12] showed limited inclusion such as demographic characteristics, hypertension, or smoking status. We provide the comorbidities included in each study in

Supplementary Table S1. Adjusted analyses generally found no significant association between BZD use and dementia or cognitive decline after accounting for baseline cognition and comorbidities [

12,

14,

18]. One of these studies did report that dementia risk was not increased (HR = 1.06; 95% CI: 0.90–1.25), though high cumulative anxiolytic use was linked to subtle neuroanatomical changes [

12].

In contrast, studies of younger or midlife populations provided different insights. Boeuf-Cazou et al., examining healthy adults aged 32–62 years, found that long-term BZD use was associated with significantly lower delayed recall among women, with no effect in men [

19].

There was also notable heterogeneity in the neuropsychological assessments. Among the six studies that evaluated cognition as an outcome, three [

13,

20,

21] used composite cognitive measures such as the Mini-Mental Status Examination (MMSE) or ADAS-Cog, whereas the remaining three [

11,

16,

19] employed selected domain-specific tests, with or without a composite score. The neuropsychological domains assessed included immediate and delayed free recall, psychomotor speed, and executive function.

Two studies reported that BZD users had lower baseline cognitive scores compared to non-users, but their cognitive trajectories over follow-up did not differ significantly, indicating no accelerated decline [

16,

21]. The authors concluded that the difference in cognitive scores between groups may not be attributable to BZD exposure. Two studies reported that among participants with existing Alzheimer’s disease or MCI, BZD use was linked with other adverse outcomes [

13,

20]. Specifically, Dyer et al. reported increased risk of delirium among BZD-exposed AD patients, while Borda et al. observed functional impairments associated with BZD use, despite minimal differences on cognitive trajectories measured with the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive Subscale (ADAS-Cog).

In addition, several studies [

9,

10,

12,

13] included in our review controlled for concomitant medication use such as antidepressants, whereas others did not differentiate between exclusive benzodiazepine use and polypharmacy. Approaches to handling the use of other medications also varied across studies. Several studies adjusted for concomitant psychotropic medication use in their analyses [

9,

10], while others specifically reported the effects of concurrent benzodiazepine and antidepressant use [

13]. Therefore, a limitation concerns concomitant medication use, as several studies did not isolate the cognitive effects of benzodiazepines from those of other psychotropic or sedative agents, thereby introducing potential confounding from polypharmacy.

Finally, there was also heterogeneity in the inclusion criteria for baseline cognitive status among cognitively healthy individuals. Teverovsky recruited participants from low-socioeconomic-status communities, including those with age- and education-corrected MMSE scores ≥ 21, while Hofe included cognitively healthy participants with MMSE scores ≥ 26.

3.3. Sex Effect

Of the 17 original manuscripts reviewed, only 2 separated by sex [

11,

19]. One study that analyzed participants by sex found a negative impact in long-term memory, specifically in delayed free recall, among long-term BZD users, but only in women [

19]. In addition, one study reported that many long-term BZD users most frequently showed impaired performance in processing speeds (32.6%) and sustained attention (27.2%), with women demonstrating poorer performance than men [

11].

3.4. Prodromal Symptoms

BZDs are often prescribed for insomnia and anxiety, both of which may be risk factors for dementia. Guo et al. focused on patients with chronic insomnia, finding that BZD exposure density was an independent risk factor for cognitive impairment in middle-aged and older patients, alongside three other significant factors: sleep quality, age, and income level [

8]. Overall, this study does not completely exclude the possibility of reverse causation. Zetsen et al. identified state anxiety as a key modifier of cognitive performance, noting significant cognitive impairment in 20.7% of long-term BZD users, especially in processing speed and attention [

11]. The findings [

8,

10,

11,

18] suggest that underlying psychiatric symptoms, such as anxiety, may influence cognitive trajectories independently of BZD pharmacology, potentially confounding associations between BZD use and cognitive impairment. Reverse causation is a major concern: insomnia, anxiety, and depression may precede dementia and mimic drug effects. Biétry et al. and Gray et al. modeled such protopathic bias using lagged exposure periods and exclusion criteria, which reduced or eliminated observed risk [

10,

18]. In contrast, studies like Sun et al. that did not adjust for reverse causation tended to report higher dementia incidence [

7]. This was echoed by Pariente et al., who reviewed 11 observational studies and noted that while many found statistically significant associations between BZD use and dementia, concerns about protopathic bias, incomplete confounder control (e.g., psychiatric burden and cognitive reserve), and lack of experimental data preclude definitive conclusions.

3.5. Pharmacokinetics, Half-Life Time, Dose, and Duration of Exposure

Of the 17 articles reviewed in the study, three studies investigated the pharmacokinetics of BZD in relation to cognition [

7,

15,

22]. Long-half-life BZDs (e.g., diazepamand clonazepam) were more frequently associated with cognitive impairment and dementia risk than short-acting agents [

7]. Shash et al. reported a 62% increased dementia risk for long-acting BZDs (HR = 1.62, CI = 1.11–2.37) but not for short-acting agents (HR = 1.05, CI = 0.85–1.30) [

15]. Sun et al. similarly found 2.86-fold-higher odds of dementia for clonazepam (OR = 2.86) and 2.6-fold-higher odds of dementia for diazepam (OR = 2.60) compared to controls [

7]. By contrast, short-acting agents demonstrated weaker or null associations. Torres-Bondia et al. found that short-half-life BZDs were associated with dementia risk only at the highest dose exposures [

22], while Guo et al. reported that Z-drugs were associated with preserved or improved attention performance in chronic insomnia patients [

8].

A dose–response relationship was also examined in two studies [

12,

22]. Hofe et al. reported a 33% increased dementia risk with higher cumulative anxiolytic dose (HR = 1.33). Torres-Bondia et al. reported a dose-dependent association for short-half-life BZDs, where only high-dose exposure was linked to dementia risk. The study also showed a dose–response trend for short-to-intermediate-half-life BZDs, where a 21% increased risk of dementia was observed among individuals with exposure categories of 91–180 defined daily doses (DDDs) (HR = 1.21) and a 28% increased risk of dementia among those with exposure > 180 DDDs (HR = 1.28), both compared with individuals exposed to <90 DDD. Interaction analyses indicated that the risk of dementia may depend jointly on BZD half-life and cumulative dose, rather than either factor alone. Torres-Bondia et al. also reported that long-half-life BZDs were associated with a 21% higher dementia risk only at the highest exposure level (>180 DDDs; HR = 1.21), and women demonstrated stronger dose–response effects than men across all exposure groups.

Longer duration of BZD use was associated with greater cognitive risk in several studies [

7,

22], whereas short-term use generally showed null or weaker associations [

7,

22]. Sun et al. observed elevated odds of dementia with continuous use, particularly for clonazepam (OR = 2.86) and diazepam (OR = 2.60), while short-term users had minimal risk. Torres-Bondia et al. similarly observed that short-half-life BZDs were only associated with increased dementia risk at high cumulative exposure. In addition, a list of the BZDs reported in the included studies is provided in

Supplementary Table S2.

All studies included are summarized in

Table 1. In

Table 1, associations of all studies re classified into no association (grey), moderate association (yellow), and strong association with dementia or cognitive decline (red). A strong association was defined as one supported by a statistically significant

p-value (

p < 0.05) for the entire study cohort, while a moderate association was defined as significance observed only in specific contexts or subgroup analyses. As a result, six studies show no association, six show a moderate association, and five show a strong association with dementia risk or cognitive impairment. Further details on the characteristics of the included studies are available in the

supplementary Tables S1 and S2.

4. Discussion

Benzodiazepines are widely prescribed for their anxiolytic and sedative effects. Biologically, BZDs take advantage of the inhibitory receptors within the brain. BZDs are positive allosteric modulators of the gamma amino butyric acid (GABA)-A receptor and, when bound, lead to an increase in GABA-activated channel openings, hyperpolarization, and reduced excitability of neurons. Of the 19 subunits on the receptor, the alpha subunit is thought to mediate the anxiolytic and amnestic effects of BZDs and is primarily located within the hippocampus. Therefore, continued activation of this inhibition, especially within memory regions, could lead to poorer cognitive performance. Further research is needed to clarify the role of BZD in memory formation, to decipher how these subunits modulate memory, and to determine whether these memory deficits fade after discontinued use of BZDs. In humans, the mechanisms are even more complicated, and current evidence remains mixed due to heterogeneity in lifestyle, comorbid medical conditions, concurrent medication use, and their interactions.

As a result of this review, the literature remains inconsistent. Among 17 reviewed articles, five reported an association between overall BZD use and increased dementia risk or lower cognitive status [

7,

8,

9,

11,

17], while others found subtle decline in specific contexts or no clear evidence. We attributed the variability in findings primarily to several factors, including study design, baseline cognitive status of participants, subgroup effects (e.g., sex), prodromal symptoms, the half-life of BZD, and adjustment for comorbidities. These aspects are further discussed below.

4.1. Study Design

Of the four studies employing a case–control design [

7,

8,

9,

10], three [

7,

8,

9] reported an association between BZD use and dementia risk. Two of these studies [

9,

10] incorporated a lag period to account for a prodromal period, and Bietry found that an initially observed association became nonsignificant after adjusting for prodromal symptoms. Thus, incorporating a prodromal symptom period is recommended to minimize reverse causation. Twelve studies employed a cohort design, and their findings were more heterogeneous than those from case–control studies. Most prospective studies defined BZD exposure based on baseline or participants’ prior history up to baseline [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18], whereas retrospective cohort designs considered participants’ entire BZD use during the study period [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. Each operational definition of exposure from cohort design carries trade-offs. Baseline-only definitions may misclassify individuals who initiated after baseline as unexposed, yet this approach can reduce bias from prodromal symptoms that precede dementia or cognitive decline. Defining exposure across the entire study period allows a clear comparison between ever-users and never-users but complicates causal inference, since prodromal symptoms may drive both BZD exposure and cognitive decline. Similarly, modeling exposure as a time-varying covariate captures dynamic use patterns but remains vulnerable to reverse causation from prodromal symptoms. Therefore, it is advisable to consider a lag period and exclude exposure data from the few years preceding dementia diagnosis, thereby minimizing protopathic bias [

18].

4.2. Age and Sex Effect

Age and baseline cognitive status appear to consistently modify the relationship between BZD exposure and cognitive outcomes. In younger or cognitively healthy cohorts, BZDs were more often linked to subtle or domain-specific impairments, such as reduced delayed recall in women [

19], rather than overt progression to dementia. By contrast, in older adults, typically with a high burden of preexisting vulnerability or Alzheimer’s disease, BZD use was associated with functional difficulties and heightened risk of delirium, even when longitudinal decline in cognitive measures was minimal [

13,

20]. These observations suggest that BZDs may exacerbate preexisting vulnerabilities rather than acting as a uniform driver of long-term cognitive deterioration.

Aging women are prescribed BZDs often at higher rates than men and there is evidence that BZDs have a greater negative impact on women. Of the 17 original manuscripts reviewed, two studies separated by sex [

11,

19]. Although not a prominent focus, sex and gender have a strong impact on BZD use and cognitive changes in two studies. Reasons for greater female impact could be due to the long-term use or high prevalence of anxiety and stress-related disorders in women. Additionally, women are more likely than men to report misusing BZDs to cope with negative feelings [

24]. Biologically, progesterone and allopregnanolone can interact with GABA-A receptors, which could intensify withdrawal [

25]. BZDs are also known to impact the hypothalamic–pituitary axis, leading to hormonal imbalance [

26]. It is important to note that in most studies women were postmenopausal (over 65), which involves a permanent decline in progesterone and less interaction with GABA receptors [

27]. This could reduce natural GABA activity, making BZDs more potent for women during or post menopause. If women are taking hormone replacement therapy, these synthetic hormones can also alter BZD metabolism by increasing BZDs in the body [

28]. Interestingly, BZDs are fat-soluble, and women typically have a higher adipose tissue percentage than men, which could lead to longer duration of drug action and greater effect from the same dose in women [

29]. The sedative effects of BZDs, combined with decreased bone density [

30] (common for postmenopausal women), could increase the risk of falls and fractures. Although women exhibited greater cognitive decline, there were no studies that examined dementia incidence in men and women. This is an open area of research and should be considered a major factor when analyzing BZD and dementia risk. In sum, because BZDs may have a greater impact on women through modulation of GABAergic and inhibitory neurons by sex hormones, sex should be examined as an effect modifier rather than treated solely as a covariate to control for in analyses of BZD use and cognition.

4.3. Prodromal Symptoms

BZD and related drugs have been prescribed more often for the elderly than younger people. Investigating BZDs’ relationship with dementia is challenging among older people because dementia is often preceded by symptoms such as insomnia, anxiety, and depression—conditions commonly treated with BZDs. The presence of this prodromal phase complicates assessment of any causal association. Higher prevalence of dementia among BZD takers may partly reflect reverse causation. However, it is difficult to discern whether high levels of anxiety itself are associated with cognitive deficits, as state anxiety, but not trait anxiety, is also a significant predictor of cognitive performance. Still, this only explains 26.5% of the variance, suggesting that anxiety alone can’t fully explain the cognitive deficits observed [

11]. The chicken and egg question still remains when asking whether BZDs impact cognition and dementia or whether anxiety and insomnia are the root cause. When using lagged exposure periods, the observed BZD risk is reduced or even eliminated [

10]. In the aforementioned studies [

10,

11], only healthy aged patients were included at baseline and only dementia incidence was used as an outcome, which might suggest that BZDs have more of an impact on global cognition rather than dementia incidence.

To disentangle anxiety from BZDs, other studies have examined patients taking BZDs for pain rather than anxiety and mood disorders and measured incident dementia [

31]. Over a five-year period, no significant relationship between BZD use and dementia risk was found [

31]. These results suggest little evidence of a causal relationship between BZD use and dementia risk. One study [

15] examined the extent to which baseline vulnerabilities, insomnia, anxiety, depression, and SES, explain the relationship between benzodiazepines and cognitive outcomes. Shash et al. progressively fitted Cox proportional hazards models, first adjusting for age and sex at Stage I; then for age, sex, body mass index, living status, education, self-perceived health, alcohol consumption, smoking, diabetes, history of hypertension, cardiovascular or cerebrovascular disease, hypercholesterolemia, cranial trauma, and baseline cognitive status at Stage II; and finally for all Stage I and II variables plus depression, anxiety, and insomnia at Stage III. As a result, the hazard ratio for benzodiazepine (BZD) use and incident dementia gradually decreased (Stage II: HR = 1.14, 95% CI 0.94–1.38; Stage III: HR = 1.10, 95% CI 0.90–1.34). We therefore note a noticeable attenuation in the association between BZD use and incident dementia after adjusting for insomnia, anxiety, and depression.

4.4. Pharmacology

Drug-specific factors, including half-life, cumulative dose, and duration of use, further shaped risk profiles. Long-acting BZDs, such as diazepam and clonazepam, were more consistently linked to cognitive impairment and dementia outcomes [

7,

15], whereas short-acting agents appeared to confer weaker or more restricted effects. Several studies reported dose–response relationships, with greater cumulative exposure and longer-half-life compounds associated with higher risk [

22]. Similarly, continuous or long-term use appeared more detrimental than intermittent or short-term prescriptions [

7,

22]. Furthermore, interaction analyses in several studies [

15,

22] indicate that dementia risk depends jointly on benzodiazepine half-life and cumulative dose, with long-acting, high-exposure regimens producing the strongest associations. These effects were more pronounced among women, suggesting potential sex-specific pharmacokinetic vulnerability. Notably, these associations were sensitive to study design, particularly in accounting for prodromal symptoms such as insomnia, anxiety, or depression.

4.5. Socioeconomic Status

While most studies did not address the impact of BZDs among socially vulnerable populations, one study [

17] built its cohort from low-socioeconomic-status (SES) communities, where BZD users showed a higher incidence of MCI. Low SES is a known risk factor for multiple health conditions, including cognitive decline in older adults. Further studies are warranted to investigate patterns of BZD prescription and their association with cognitive outcomes among older adults, particularly in-low SES populations.

4.6. Implication of Discontinuation of BZDs on Cognition

Of 17 articles, two studies [

17,

18] included time-varying measures of BZD use over the study period. However, none of the studies examined alteration of cognitive trajectories following discontinuation of BZD use. There is a lack of evidence regarding whether discontinuation attenuates this risk. This gap warrants further investigation in future studies. One study [

19] found that long-term BZD use was associated with impaired delayed free recall among midlife women. Another study [

32] demonstrated that domain-specific cognitive effects are detectable in midlife and can predict later-life MCI or dementia. Based on these findings, an important question arises: do domain-specific cognitive changes observed in midlife BZD users predict later-life MCI or dementia independently of BZD exposure in later life? As discussed earlier, the answer likely depends on whether discontinuation of BZD use restores the long-term cognitive trajectory. This potential effect remains unresolved and warrants further investigation.

4.7. Mediation Mechanism Between BZD and Cognition

While none of the studies included in this review directly examined potential mediation pathways between BZD exposure and cognition, Hofe et al. reported an association between long-term benzodiazepine use and both structural and functional brain changes, including subtle neuroanatomical alterations linked to high cumulative anxiolytic doses. In addition, Dyer et al. identified an increased incidence of delirium among benzodiazepine-exposed patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Together, these findings suggest potential mechanistic pathways that warrant further investigation through neuroimaging and neuropathological studies.

4.8. Strengths and Weaknesses

We selected 17 articles addressing BZD use and cognition, following PRISMA 2020 guidelines. Due to the high level of inconsistency observed across studies, this review does not draw a definitive conclusion regarding the association between BZD use and cognition. However, it highlights several potential factors that may underlie the heterogeneity of findings.

Through detailed comparisons across studies, we identified several methodological and clinical factors contributing to the inconsistencies. These include study design, inclusion of comorbidities and medications, neuropsychological tests applied for assessment of cognitive status, consideration of subgroups, subtypes of BZD drugs, dose and duration.

A limitation of this review is the inclusion of only two databases, which are PubMed and Google Scholar. As a result, some relevant studies indexed exclusively in other databases such as Scopus or Embase may not have been captured, although the inclusion of PubMed and Google Scholar provided broad coverage of clinical and epidemiological literature, partially mitigating this limitation.

Another potential limitation of this review is the restricted search timeframe (2010–2025). Although this window was selected to capture the most recent evidence, it may have excluded earlier research that could provide additional contextual insights. Future reviews incorporating a broader timeframe may yield a more comprehensive synthesis of the literature. Moreover, our review does not capture the holistic impact of BZD use on a person’s life, including effects on physical functionality and basic and instrumental activities of daily living. Furthermore, most of the studies included were based on cognitively healthy individuals at baseline and examined either cognitive change or incident dementia. Given that persistent prescription—often at high BZD doses—has been reported among patients with moderate-to-severe dementia, further research in this population is warranted.

5. Conclusions

Benzodiazepines remain valuable for short-term indications but may carry potential cognitive risks. However, evidence for this link is inconsistent, driven in part by heterogeneity in study design, baseline patient characteristics, and exposure definitions. Our review highlights that cognitive risk reflects an interplay between age, baseline cognition, comorbidities, concomitant medications, SES, and drug properties such as half-life, dose, and duration, with vulnerability often amplifying rather than universally mediating risk. Clinically, these findings support individualized prescribing and cautious use of long-acting agents at higher doses or prolonged durations, especially in vulnerable populations—older adults, women, low SES, and cognitively impaired patients. These populations warrant focused attention in future research.