Abstract

Background: Self-compassion has emerged as an important protective factor against eating pathology, yet evidence from community-based samples, particularly in Southern Europe, remains scarce. Methods: A total of 335 Greek adults (223 women, 112 men; aged 18–35 years, M = 26.2, SD = 5.1) completed validated measures of eating pathology (EAT-26), self-compassion (SCS), and affect (PANAS). Demographic variables (age, gender, education), BMI, and exercise frequency were also assessed. Correlational, group comparison, and hierarchical regression analyses were conducted. Results: Higher levels of self-compassion were consistently associated with fewer disordered eating symptoms, even after controlling BMI, education, gender, exercise, and affect. Women reported higher levels of disordered eating than men, while no significant gender differences were observed in self-compassion. Age was positively associated with self-compassion, with older adults reporting higher levels compared to younger adults. Positive affect was strongly linked to greater self-compassion, whereas negative affect showed the opposite pattern. Conclusions: Self-compassion emerged as a robust protective factor against disordered eating, independent of demographic and affective variables. Women appeared more vulnerable to disordered eating than men. In contrast, although younger adults tended to report lower self-compassion, no significant gender differences emerged in self-compassion, underscoring its potential as a universal psychological resource for prevention and intervention.

1. Introduction

Eating disorders (EDs), such as anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge-eating disorder, are serious psychiatric conditions associated with high morbidity, mortality, and impaired quality of life (Smink et al., 2012). As recently summarized by Attia and Walsh (2025), the lifetime prevalence of eating disorders is estimated at approximately 2–5% and these conditions are linked to high rates of medical complications, comorbid psychiatric disorders and elevated mortality. Increasingly, disordered eating is understood to exist on a continuum, ranging from normative eating behaviors to subclinical patterns and, at the most severe end, clinical eating disorders. Even mild or subthreshold symptoms can lead to adverse physical, psychological, and social consequences (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). A recent meta-analysis by Qian et al. (2022) found that the pooled lifetime prevalence of eating disorders in general populations was around 1.69%, with significant variation by region and gender. Importantly, many of these cases remain undetected and untreated, highlighting the need to examine both clinical and community populations.

Several theoretical models have been proposed to explain the development and maintenance of disordered eating. According to Rodrigues and Machado (2025), difficulties with emotion regulation represent a transdiagnostic vulnerability across the spectrum of eating disorders. Extending this perspective, Selby et al. (2024) emphasize that dysregulation of positive as well as negative emotions plays a pivotal role in the onset and maintenance of disordered eating behaviours, underscoring the need for theoretical models and interventions that address the full range of emotional processes involved in eating pathology. According to Emotion regulation difficulties and disordered eating in adolescents and young adults: a metaanalysis (Zhou et al., 2025), there is a moderate positive association between difficulties in emotion regulation and disordered eating behaviours in adolescents and young adults, with gender moderating this relationship but body mass index not playing a significant role. Beyond individual processes, the biopsychosocial model emphasizes that biological factors (e.g., body mass index, genetic/epigenetic vulnerabilities), psychological factors (e.g., self-compassion, disrupted emotional regulatory development), and sociocultural influences (e.g., cultural norms and social roles) interact to shape the risk for disordered eating (Cimino et al., 2025; Ricciardelli & McCabe, 2004). Together, these models highlight the importance of examining both vulnerabilities and protective factors in understanding eating pathology.

Research on risk factors consistently highlights body image disturbance and disordered eating behaviors as strong predictors of eating disorder onset. Core features such as drive for thinness, fear of weight gain, and compensatory behaviors often emerge in subclinical forms, increasing vulnerability to clinical disorders (Smolak & Levine, 2015). According to Peschel et al. (2024), patterns of sub-clinical disordered eating behaviours assessed in daily life among adolescents and young adults were prevalent even in individuals without a lifetime eating disorder diagnosis and were strongly associated with multiple established risk factors for clinical eating disorders. Studying these processes in non-clinical samples is therefore essential, both to track prevalence and to identify protective mechanisms that may buffer against risk (Langdon-Daly & Serpell, 2017).

At the same time, it is increasingly recognized that protective factors are not simply the absence of risks but represent distinct variables that reduce the likelihood of pathology through multiple pathways. They may directly hinder the development of disordered eating, mitigate the impact of existing risk factors, or interrupt maladaptive processes that would otherwise escalate (Smolak & Levine, 2015; Tylka, 2011). Consequently, prevention efforts should focus not only on reducing risks but also on actively cultivating protective resources at the individual, family, and community levels. One such factor that has received growing empirical attention is self-compassion, which may serve as a buffer against the development of eating pathology.

A growing body of research in both clinical and non-clinical samples suggests that self-compassion may buffer the association between body image concerns and disordered eating attitudes (Gracias & Stutts, 2024; Morgan-Lowes et al., 2023; Rosales Cadena et al., 2024; Taylor et al., 2015; Wasylkiw et al., 2012). Recent longitudinal studies have confirmed this buffering effect, showing that self-compassion significantly attenuates the relationship between weight and shape concerns and disordered eating behaviors in young adults and adolescents (Pullmer et al., 2019; Stutts & Blomquist, 2018). According to K. D. Neff (2003a), self-compassion comprises three interrelated components: self-kindness or treating oneself with warmth and understanding rather than harsh self-criticism; common humanity, the recognition that difficulties and setbacks are part of the shared human experience; and mindfulness, maintaining balanced awareness of painful thoughts and emotions without over-identification. Together, these components foster a more adaptive stance toward personal difficulties and have been shown to promote healthier emotion regulation and psychological resilience.

Self-compassion has been increasingly recognized as a protective factor in the context of body image and disordered eating. By fostering a kinder and more balanced stance toward personal struggles, self-compassion enhances self-regulation and supports adaptive responses to health-related difficulties (Terry & Leary, 2011). Empirical studies confirm its protective role, showing that higher levels of self-compassion are associated with reduced body dissatisfaction and fewer disordered eating symptoms in both community and clinical samples (Braun et al., 2016; Breines et al., 2013; A. Kelly et al., 2014). According to Mey et al. (2025), momentary self-compassion in daily life is associated with more adaptive emotion-regulation strategies (such as acceptance and reappraisal) and partly mediates the link between self-compassion and well-being. Moreover, emerging evidence indicates that self-compassion moderates the relationship between physical–appearance perfectionism and disordered eating, thereby buffering the maladaptive impact of perfectionistic concerns (Bergunde & Dritschel, 2020). However, emerging clinical research suggests that the presence of barriers to self-compassion—such as fear of self-kindness or over-identification with failure—may limit its beneficial effects. For example, Geller et al. (2022) found that these barriers significantly predicted poorer treatment outcomes among inpatients with eating disorders, even beyond baseline self-compassion levels. Beyond its intrapersonal benefits, recent evidence highlights the social and relational dimensions of self-compassion. For instance, Katan and Kelly (2025) found that higher self-compassion was associated with greater feelings of social safeness among individuals with eating disorders, suggesting that self-compassion may not only reduce self-critical tendencies but also foster a sense of connectedness and acceptance within interpersonal contexts.

Importantly, self-compassion has been linked to more effective emotion regulation, helping individuals manage negative affect and cope with distressing experiences (Hwang et al., 2016; Leary et al., 2007). This buffering effect may be explained through self-compassionate cognitive strategies, such as positive cognitive restructuring, which contribute to greater well-being and resilience (A. Allen & Leary, 2010; K. Neff et al., 2007). In addition, prospective evidence suggests that self-compassion, when combined with intuitive eating and positive body image, protects against the future onset of core eating disorder symptoms (Linardon, 2021).

Prior research suggests that self-compassion tends to increase with age and may play a more salient role in psychological well-being among adults relative to younger individuals (A. B. Allen & Leary, 2014; Hwang et al., 2016). Findings in adolescent and young adult samples further indicate robust links between self-compassion and emotional well-being (Bluth et al., 2016). From a lifespan perspective, developmental gains in emotion regulation may partly account for stronger associations between self-compassion and adaptive functioning at later ages. In the present study, we therefore examine whether the association between self-compassion and disordered eating varies by age within our 18–35 cohort.

Although women are generally more exposed to thin-ideal pressures and report higher disordered eating on average, men are also affected by eating pathology, often shaped by muscularity-oriented ideals (Furnham et al., 2002; Smolak & Levine, 2015). Importantly, male presentations may be under-recognized due to stigma and help-seeking barriers, contributing to under-diagnosis and under-treatment (Carlat et al., 1997; Strother et al., 2012). With respect to self-compassion, some studies report lower scores among women, potentially via higher body shame, though findings are mixed across samples (Breines et al., 2013; Homan & Tylka, 2015; K. D. Neff, 2003b). Given these patterns, we test gender differences in disordered eating and explore whether self-compassion differs by gender in a community adult sample including both women and men.

Regular physical activity is widely recognized as beneficial for health and well-being (Kwan & Bryan, 2010). However, in the context of disordered eating, exercise can assume maladaptive forms, functioning as a compensatory strategy and exacerbating eating pathology (Levallius et al., 2017). While moderate exercise is associated with positive affect and healthier attitudes toward food, compulsive or excessive exercise has been linked to greater eating disorder symptomatology and, in extreme cases, increased psychological distress (Magnus et al., 2010; Thome & Espelage, 2004). These findings underscore the need to examine the role of exercise not only as a health-promoting behavior but also as a potential risk marker when co-occurring with disordered eating attitudes.

Cultural norms strongly influence body ideals and eating-related behaviors. In Western societies, thinness has traditionally been associated with attractiveness, self-control, and success, contributing to widespread body dissatisfaction and dieting behaviors (Bordo, 2003; Costarelli et al., 2009). Recent international findings demonstrate that self-compassion can buffer the negative impact of thin-ideal and weight-bias internalisation on eating pathology, underscoring its role within sociocultural frameworks of body image disturbance (Montague et al., 2025).

In Greece, community-based evidence remains limited, with most research focusing on adolescents or female university students (Vlachakis & Vlachakis, 2014). Existing data indicate high levels of body dissatisfaction and disordered eating among young people, with prevalence rates ranging from 16–20% (Bilali et al., 2010). Male populations, however, remain understudied, despite evidence that sociocultural pressures for muscularity may also predispose men to disordered eating (Smolak & Levine, 2015).

Recent Greek studies emphasize the need to examine protective psychological resources in adult community samples, moving beyond traditional risk-focused approaches (Janicic & Bairaktari, 2013). Self-compassion has increasingly been recognized as one such factor, linked to reduced anxiety, depression, and maladaptive coping strategies (Karakasidou et al., 2021, 2023). Building on this work, the present study extends the investigation of self-compassion into the domain of eating pathology within a Greek community sample. Findings on gender differences in self-compassion are mixed: while some studies have reported lower levels among women (Karakasidou et al., 2020), others did not detect consistent differences (Breines et al., 2013). These demographic patterns underscore the importance of considering age- and gender-related differences when examining self-compassion as a protective factor. Furthermore, recent longitudinal findings by Papadimitriou and Karakasidou (2025) showed that low childhood self-esteem and poor mental health are linked to elevated risk of disordered eating in adulthood, highlighting the enduring impact of early psychological vulnerabilities. Taken together, these findings suggest that demographic factors and developmental antecedents may shape the extent to which individuals benefit from self-compassion in buffering against disordered eating. his perspective aligns with contemporary meta-analytic insights identifying self-compassion and self-criticism as transdiagnostic processes central to eating-disorder vulnerability and recovery (Türk, 2024).

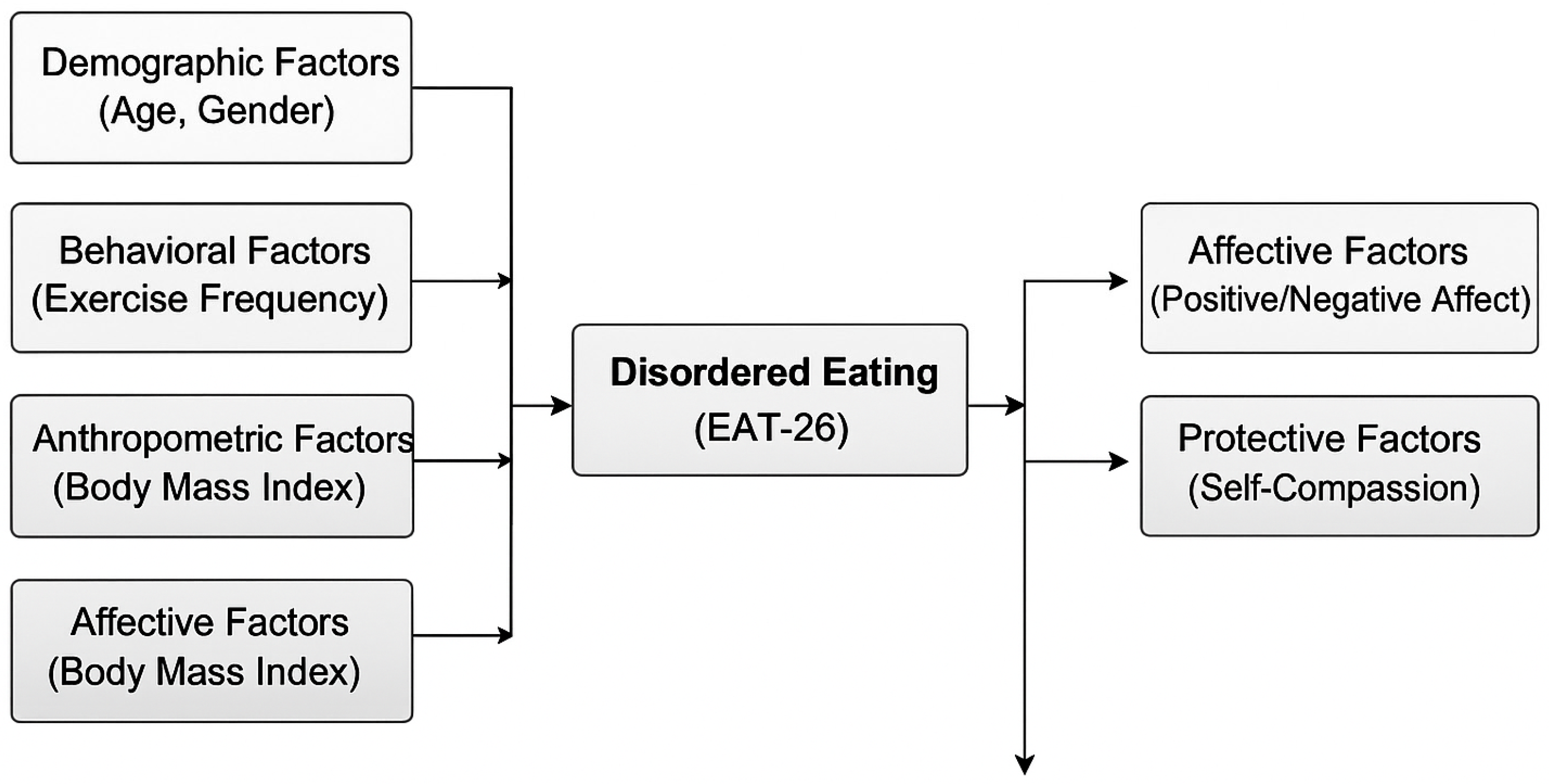

Guided by the biopsychosocial model of disordered eating (Ricciardelli & McCabe, 2004), the present study examined whether self-compassion functions as a protective factor against eating pathology in a Greek community sample of young adults. In addition, it explored the role of demographic (age, gender, education, BMI) and psychosocial factors (positive and negative affect, exercise frequency) in relation to disordered eating.

Based on prior research, we hypothesized that:

Self-compassion would be negatively associated with disordered eating symptoms and would uniquely predict eating pathology beyond BMI, demographic factors, exercise, and affect.

Age differences would emerge, such that the protective role of self-compassion would be stronger among older participants within the 18–35 range.

Gender differences were expected in disordered eating, with women reporting higher symptoms than men. However, no consistent differences were anticipated in self-compassion, given that prior studies have produced mixed findings regarding gender effects.

Affect would be linked to both constructs, with positive affect positively associated with self-compassion and negative affect positively associated with eating pathology.

2. Method

2.1. Participants and Procedure

A total of 335 individuals (223 women, 112 men) aged 18–35 years (M = 26.2, SD = 5.1) participated in the study. Recruitment was conducted via online advertisements and university mailing lists. Eligibility criteria included age between 18 and 35 years and sufficient fluency in Greek. Data collection took place in September 2025. Participants completed an anonymous online survey consisting of demographic questions, validated self-report scales, and items assessing exercise frequency and eating attitudes. Participation was voluntary and uncompensated. All participants provided informed consent prior to beginning the survey.

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Panteion University, Athens, Greece (approval code: 59-3/09/2025) and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

A minimum sample size of 120 participants was estimated through an a priori power analysis (G*Power 3.1), assuming a medium effect size (f2 = 0.15), α = 0.05, and power = 0.80 for regression models with up to seven predictors. The final sample (N = 335) exceeded this requirement, ensuring sufficient statistical power.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Demographics

Demographic variables included age, gender, educational level, height, weight, and exercise frequency.

2.2.2. Anthropometric Data

Height and weight were self-reported for the calculation of Body Mass Index (BMI = kg/m2). Participants were classified as underweight (<18.5), normal (18.5–24.9), overweight (25–29.9), or obese (≥30) according to World Health Organization (1995) criteria. Self-reported height and weight are a reliable method (Spencer et al., 2002; Shapiro & Anderson, 2003).

2.2.3. Eating Attitudes Test (EAT-26)

The EAT-26 is a 26-item self-report questionnaire assessing symptoms and concerns characteristic of disordered eating and attitudes toward body weight. It consists of three subscales: Dieting (13 items), Bulimia and Food Preoccupation (6 items), and Oral Control (7 items).

Responses are given on a 6-point Likert scale with the following options: Always (3), Usually (2), Often (1), Sometimes (0), Rarely (0), Never (0).

For most items, higher scores indicate greater disordered-eating symptomatology. However, items 1, 6, 7, 10, 11, 12, 14, 16, 17, 22, 23, 24, and 25 are reverse-scored according to the original scoring guidelines (Garner et al., 1982). The total score is obtained by summing all item scores, yielding a possible range from 0 to 78. A total score ≥ 20 indicates clinically relevant symptomatology suggestive of elevated risk for an eating disorder. Subscale scores were also computed to explore domain-specific patterns of disordered eating (Dieting, Bulimia, Oral Control). The internal consistency in the present sample was high (Cronbach’s α = 0.90).

The Greek version (Varsou & Trikkas, 1991) has demonstrated good reliability (α = 0.81) and has been validated in previous studies (Costarelli et al., 2009; Yannakoulia et al., 2004).

2.2.4. Self-Compassion Scale (SCS)

The SCS (K. D. Neff, 2003a, 2003b) is a 26-item self-report measure of self-compassion with six subscales: self-kindness, self-judgment, common humanity, isolation, mindfulness, and over-identification. Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = almost never to 5 = almost always). Subscales are combined into a total self-compassion score after reverse-scoring negative subscales. The SCS has demonstrated high reliability in its original form (α = 0.92–0.94; K. D. Neff, 2003b). For the purposes of the present study, the validated Greek version of the SCS (Karakasidou et al., 2017) was used, which has shown good psychometric properties in the Greek population. Because only the total score was used in analyses, the reported Cronbach’s α (0.92) refers to the overall SCS scale in the present sample.

2.2.5. Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS)

The PANAS (Watson et al., 1988) consists of 20 adjectives describing emotions (10 positive, 10 negative). Participants rated how much they experienced each emotion on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = very slightly to 5 = extremely), either at the present moment or during the past week. Positive and negative affect scores were computed separately. The scale has demonstrated high reliability (α = 0.84–0.90). In the present study, Cronbach’s α was 0.86 for PA and 0.88 for NA.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics, Pearson correlations, independent-samples t-tests, and multiple regressions were conducted using the full sample (N = 335). Predictors in the regressions included self-compassion, age, gender, BMI, exercise frequency, and positive and negative affect. All predictors were entered simultaneously. Assumptions of normality, linearity, homoscedasticity, and multicollinearity were examined; all variance inflation factors (VIFs) were below 2.0.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

Descriptive statistics for all study variables are presented in Table 1. The mean age of participants was 26.2 years (SD = 5.1). Inspection of skewness and kurtosis values indicated acceptable normality for most variables, with the exception of BMI and EAT-26, which showed positive skew. Given the large sample size (N = 335) and the robustness of parametric tests to moderate deviations from normality, no transformations were applied. However, medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) are additionally reported for these variables to provide distributional context. All scales demonstrated good to excellent internal consistency (α = 0.86–0.92).

Table 1.

Descriptives for all variables.

3.2. Correlations

Correlations among all study variables are presented in Table 2. Prior to computing correlations, all variables were screened for normality. Although BMI and EAT-26 displayed moderate positive skewness, Pearson’s r was used for consistency with previous research; however, supplementary analyses using Spearman’s ρ yielded a similar pattern of results, confirming the robustness of findings.

Table 2.

Correlation Matrix.

As shown in Table 2, self-compassion was negatively correlated with disordered eating (r = −0.33, p < 0.01) and negative affect (r = −0.49, p < 0.01), and positively correlated with positive affect (r = 0.52, p < 0.01), BMI (r = 0.20, p < 0.05), and age (r = 0.23, p < 0.05). Positive affect was negatively correlated with disordered eating (r = −0.21, p < 0.05) and negative affect (r = −0.28, p < 0.01). BMI correlated negatively with exercise (r = −0.32, p < 0.01) and positively with age (r = 0.21, p < 0.05). Education was negatively correlated with self-compassion (r = −0.22, p < 0.05). No other significant associations emerged.

3.3. Group Differences (Gender, Age)

Independent-samples t-tests revealed that women reported significantly higher disordered eating scores than men, t(333) = 2.85, p = 0.005 (two-tailed). No significant gender differences were observed in self-compassion, t(333) = 1.02, p = 0.31. Pearson’s correlations showed that age was negatively associated with disordered eating (r = −0.23, p = 0.021) and positively associated with self-compassion (r = 0.24, p = 0.017), indicating that older participants reported greater self-compassion and fewer disordered-eating symptoms.

3.4. Regression Analysis

Predictors of Disordered Eating

A multiple regression examined predictors of disordered eating (EAT-26). Predictors entered simultaneously were self-compassion, age, gender (0 = male, 1 = female), BMI, exercise frequency, positive affect, and negative affect. The model was significant, F(7, 327) = 3.90, p = 0.001, R2 = 0.23. Only self-compassion significantly predicted lower disordered eating (B = −0.24, SE = 0.08, β = −0.31, t = −2.98, p = 0.003, 95% CI [−0.40, −0.08]).

Predictors of Self-Compassion

A second regression examined predictors of self-compassion (SCS). Predictors entered simultaneously were disordered eating, age, gender, BMI, education (1 = secondary, 2 = tertiary), exercise, positive affect, and negative affect. The model was significant, F(7, 327) = 10.48, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.44. Significant predictors were education (B = −6.48, SE = 2.85, β = −0.21, t = −2.28, p = 0.025), age (B = 0.67, SE = 0.26, β = 0.24, t = 2.58, p = 0.010), positive affect (B = 1.96, SE = 0.58, β = 0.37, t = 3.39, p = 0.001), and disordered eating (B = −0.57, SE = 0.18, β = −0.33, t = −3.17, p = 0.002). Gender, BMI, and exercise were not significant predictors (ps > 0.05) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Standardized Regression Coefficients Predicting Disordered Eating (EAT-26).

4. Discussion

Consistent with previous findings, higher self-compassion was associated with lower levels of disordered eating. This relationship remained significant when demographic and affective variables were included in the model, suggesting that self-compassion provides unique explanatory value beyond basic individual differences. These findings suggest that self-compassion is closely linked to healthier eating attitudes and lower vulnerability to maladaptive patterns. This aligns with recent evidence that self-compassion moderates the effects of weight and shape concerns disordered eating across both clinical and community populations (Stutts & Blomquist, 2018; Pullmer et al., 2019). Moreover, prospective data confirm that self-compassion, together with intuitive eating and positive body image, protects against the emergence of core eating disorder symptoms (Linardon, 2021). Women in the current study reported higher disordered eating scores than men, while younger participants showed lower self-compassion than older adults, underscoring the importance of demographic correlates in understanding eating-related behaviors. These patterns are consistent with cross-national data showing that younger adults tend to report lower self-compassion and greater susceptibility to sociocultural appearance pressures (Bergunde & Dritschel, 2020), a dynamic that may heighten risk for body dissatisfaction and maladaptive eating behaviors.

These results converge with international research demonstrating the beneficial role of self-compassion in mitigating maladaptive eating attitudes and behaviors (Ferreira et al., 2013; A. C. Kelly & Stephen, 2016) and extend the evidence base to the Greek context, where studies on protective psychological resources remain limited. By focusing on adults and highlighting self-compassion as a potential resilience factor, the study contributes to a more balanced understanding of vulnerability and protection in eating pathology.

No significant gender differences in self-compassion were observed, a finding consistent with previous mixed evidence (Breines et al., 2013; Homan & Tylka, 2015). The positive association between age and self-compassion aligns with prior research suggesting that older individuals tend to adopt more accepting and less self-critical perspectives (K. D. Neff & Vonk, 2009). Taken together, these demographic effects highlight the need to consider developmental trajectories and gender-specific vulnerabilities when examining the protective role of self-compassion against disordered eating.

Theoretically, the findings support models conceptualizing self-compassion as a mechanism for adaptive emotion regulation (K. Neff, 2011). In contexts where cultural ideals emphasize thinness and control, self-compassion may buffer individuals from internalizing unrealistic standards and engaging in self-punishing eating behaviors. This theoretical framing is further supported by meta-analytic and conceptual reviews positioning self-compassion and self-criticism as transdiagnostic processes central to eating-disorder vulnerability and recovery (Türk, 2024). This protective function underscores the importance of integrating self-compassion into preventive and therapeutic frameworks for eating pathology in Greece and beyond (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Biopsychosocial model summarising predictors of disordered eating (EAT-26). Note. Self-compassion is highlighted as a protective factor against disordered eating symptoms.

4.1. Contributions

The present study makes several important contributions to the literature on self-compassion and disordered eating. First, it provides novel empirical evidence from a Greek community sample, a population that has been largely overlooked in research on eating behaviors. Existing studies in Greece have predominantly focused on adolescents or female university students, often emphasizing risk factors such as body dissatisfaction or sociocultural pressures. By shifting attention toward protective psychological resources in adults, the current study broadens the scope of inquiry and underscores the value of examining resilience-oriented variables within diverse cultural contexts.

Second, the study contributes to a deeper understanding of the demographic correlations of self-compassion. Consistent with international findings, women in the present sample reported higher levels of disordered eating than men, while older adults demonstrated greater self-compassion. These results replicate and extend earlier evidence (e.g., Karakasidou et al., 2020), highlighting the importance of considering age- and gender-related differences when conceptualizing self-compassion as a buffer against maladaptive eating behaviors. Such findings also emphasize the need to tailor preventive and therapeutic interventions to specific demographic groups who may be more vulnerable to disordered eating.

Third, the study advances the theoretical integration of self-compassion with models of eating pathology. While previous work has primarily examined risk factors such as negative affect or BMI, our findings indicate that self-compassion explains unique variance in disordered eating beyond these variables. This suggests that self-compassion is not merely correlated with but may play a distinct and central role in mitigating maladaptive eating patterns. By documenting this protective function in a non-clinical adult sample, the study strengthens the argument for incorporating self-compassion into theoretical frameworks of eating pathology.

Finally, the study offers important practical implications. The findings support the potential value of self-compassion-based interventions in the prevention and treatment of disordered eating. Interventions such as the Mindful Self-Compassion (MSC) program (K. D. Neff & Germer, 2013) or self-compassion–focused writing and imagery exercises could be adapted for Greek populations and tested for efficacy in reducing body dissatisfaction and maladaptive eating behaviors. More broadly, the study underscores the relevance of culturally sensitive approaches, suggesting that interventions addressing both gender-specific vulnerabilities and age-related strengths may be particularly effective in promoting healthier relationships with food and body image.

4.2. Limitations and Future Directions

Despite its contributions, the study is not without limitations. First, the cross-sectional design precludes causal inferences. Although self-compassion was negatively associated with disordered eating, it cannot be determined whether higher self-compassion reduces vulnerability to disordered eating or whether individuals with fewer eating concerns develop greater self-compassion over time. Longitudinal and experimental designs are needed to clarify the directionality and potential causal mechanisms of these relationships.

Second, the study relied exclusively on self-report measures, which are subject to biases such as social desirability and self-presentation. Future research could benefit from incorporating multi-method assessments, including behavioral tasks, ecological momentary assessment, or qualitative interviews, to provide a more nuanced understanding of how self-compassion relates to eating behaviors in daily life.

Third, the study relied on a convenience community sample, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. Moreover, the sample was relatively young and predominantly female. Although gender and age differences were observed, the study did not include enough older adults or male participants to allow for more fine-grained subgroup analyses. Broader sampling across the lifespan and recruitment of more balanced gender groups would strengthen the external validity of future studies.

Finally, the cultural specificity of the findings should be acknowledged. While the Greek context is valuable due to the scarcity of community-based evidence, cultural norms regarding body ideals and eating behaviors vary significantly across societies. Comparative cross-cultural studies could illuminate whether the protective effects of self-compassion generalize across different sociocultural settings or are moderated by cultural values.

Future research should therefore pursue longitudinal, cross-cultural, and intervention-based designs. Testing the efficacy of self-compassion interventions, such as the Mindful Self-Compassion program (K. D. Neff & Germer, 2013), in reducing disordered eating would be a critical next step. Such studies could also examine whether tailoring interventions by gender and age enhances their effectiveness. Ultimately, integrating self-compassion into preventive and therapeutic frameworks could contribute to more holistic and culturally sensitive approaches to eating pathology.

5. Conclusions

The present study provides novel evidence that higher self-compassion is associated with fewer disordered eating symptoms among Greek adults. By extending research beyond risk-focused perspectives, it highlights the importance of cultivating self-compassion as part of broader well-being and prevention frameworks.

Practically, these findings support the integration of self-compassion-based approaches—such as Mindful Self-Compassion (K. D. Neff & Germer, 2013)—into prevention and psychoeducational programs targeting body image and eating behaviors. Developing culturally sensitive interventions tailored to local norms could enhance their accessibility and impact.

Future research should employ longitudinal and experimental designs to clarify causal pathways and test whether self-compassion training can effectively reduce eating pathology across age and gender groups. Such studies would advance a more comprehensive, culturally attuned understanding of resilience in eating behavior. For example, emerging clinical trials demonstrate that reducing barriers to self-compassion—such as fear of self-kindness or over-identification with failure—can enhance treatment outcomes among individuals with eating disorders (Geller et al., 2022). Moreover, interpersonal mechanisms such as social safeness may mediate self-compassion’s benefits (Katan & Kelly, 2025), warranting inclusion of these constructs in future intervention designs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.K. and A.K.; methodology, E.K.; Resources, E.K. and A.K.; writing—original draft preparation, E.K. and A.K.; writing—review and editing, E.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of PANTEION UNIVERSITY (protocol code 61/25-09-2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Allen, A., & Leary, M. (2010). Self-compassion, stress, and coping. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 4(2), 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, A. B., & Leary, M. R. (2014). Self-compassionate responses to aging. The Gerontologist, 54(2), 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Attia, E., & Walsh, B. T. (2025). Eating disorders: A review. JAMA, 333(14), 1242–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergunde, L., & Dritschel, B. (2020). The shield of self-compassion: A buffer against disordered eating risk from physical appearance perfectionism. PLoS ONE, 15(1), e0227564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilali, A., Galanis, P., Velonakis, E., & Katostaras, T. (2010). Factors associated with abnormal eating attitudes among Greek adolescents. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 42(5), 292–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bluth, K., Campo, R., Futch, W., & Gaylord, S. (2016). Age and gender differences in the associations of self-compassion and emotional well-being in a large adolescent sample. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 46(4), 840–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordo, S. (2003). Unbearable weight: Feminism, western culture, and the body. University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, T., Park, C., & Gorin, A. (2016). Self-compassion, body image, and disordered eating: A review of the literature. Body Image, 17, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breines, J., Toole, A., Tu, C., & Chen, S. (2013). Self-compassion, body image, and self-reported disordered eating. Self and Identity, 13(4), 432–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlat, D., Camargo, C., & Herzog, D. (1997). Eating disorders in males: A report on 135 patients. American Journal of Psychiatry, 154(8), 1127–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimino, S., Bevilacqua, A., & Cerniglia, L. (2025). Recent Developments in Eating Disorders in Children: A Comprehensive Perspective. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(17), 6042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costarelli, V., Demerzi, M., & Stamou, D. (2009). Disordered eating attitudes in relation to body image and emotional intelligence in young women. Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics, 22(3), 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, C., Pinto-Gouveia, J., & Duarte, C. (2013). Self-compassion in the face of shame and body image dissatisfaction: Implications for eating disorders. Eating Behaviors, 14(2), 207–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furnham, A., Badmin, N., & Sneade, I. (2002). Body image dissatisfaction: Gender differences in eating attitudes, self-esteem, and reasons for exercise. The Journal of Psychology, 136(6), 581–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garner, D. M., Olmsted, M. P., Bohr, Y., & Garfinkel, P. E. (1982). The Eating Attitudes Test: Psychometric features and clinical correlates. Psychological Medicine, 12(4), 871–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geller, J., Samson, L., Maiolino, N., Iyar, M. M., Kelly, A. C., & Srikameswaran, S. (2022). Self-compassion and its barriers: Predicting outcomes from inpatient and residential eating disorders treatment. Journal of Eating Disorders, 10(1), 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, D., & Mallery, P. (2024). IBM SPSS statistics 29 step by step: A simple guide and reference. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Gracias, K. R., & Stutts, L. A. (2024). The impact of compassion writing interventions on body dissatisfaction, self-compassion, and fat phobia. Mindfulness, 15(7), 1793–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homan, K., & Tylka, T. (2015). Self-compassion moderates body comparison and appearance self-worth’s inverse relationships with body appreciation. Body Image, 15, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S., Kim, G., Yang, J., & Yang, E. (2016). The moderating effects of age on the relationships of self-compassion, self-esteem, and mental health. Japanese Psychological Research, 58(2), 194–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janicic, A., & Bairaktari, M. (2013). Eating disorders: A report on the case of Greece. Advances in Eating Disorders, 2(1), 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakasidou, E., Pezirkianidis, C., Galanakis, M., & Stalikas, A. (2017). Validity, reliability and factorial structure of the Self Compassion Scale in the Greek population. Journal of Psychology and Psychotherapy, 7, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakasidou, E., Raftopoulou, G., Papadimitriou, A., & Stalikas, A. (2023). Self-compassion and well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic: A study of Greek college students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(6), 4890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakasidou, E., Raftopoulou, G., & Stalikas, A. (2020). Investigating differences in self-compassion levels: Effects of gender and age in a Greek adult sample. Psychology: The Journal of the Hellenic Psychological Society, 25(1), 164–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakasidou, E., Raftopoulou, G., & Stalikas, A. (2021). A self-compassion intervention program for children in Greece. Psychology, 12, 1990–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katan, A., & Kelly, A. C. (2025). Self-compassion promotes social safeness in patients with eating disorders. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. e-pub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, A., Vimalakanthan, K., & Carter, J. (2014). Understanding the roles of self-esteem, self-compassion, and fear of self-compassion in eating disorder pathology: An examination of female students and eating disorder patients. Eating Behaviors, 15(3), 388–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, A. C., & Stephen, E. (2016). A daily diary study of self-compassion, body image, and eating behavior in female college students. Body Image, 17, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwan, B. M., & Bryan, A. D. (2010). Affective response to exercise as a component of exercise motivation: Attitudes, norms, self-efficacy, and temporal stability of intentions. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 11(1), 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langdon-Daly, J., & Serpell, L. (2017). Protective factors against disordered eating in family systems: A systematic review of research. Journal of Eating Disorders, 5(1), 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leary, M., Tate, E., Adams, C., Batts Allen, A., & Hancock, J. (2007). Self-compassion and reactions to unpleasant self-relevant events: The implications of treating oneself kindly. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(5), 887–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levallius, J., Collin, C., & Birgegård, A. (2017). Now you see it, now you don’t: Compulsive exercise in adolescents with an eating disorder. Journal of Eating Disorders, 5(1), 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linardon, J. (2021). Positive body image, intuitive eating, and self-compassion protect against the onset of the core symptoms of eating disorders: A prospective study. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 54, 1967–1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnus, C., Kowalski, K., & McHugh, T. (2010). The role of self-compassion in women’s self-determined motives to exercise and exercise-related outcomes. Self and Identity, 9(4), 363–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mey, L. K., Morello, K., Wenzel, M., Rowland, Z., Kubiak, T., & Tüscher, O. (2025). Emotion Regulation partially mediates the link between self-compassion and well-being in daily life: Differences between overall, positive, and negative self-compassion. Mindfulness. Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montague, G., Eidipour, T., & Grant, S. L. (2025). Thin-ideal internalisation and weight bias internalisation as predictors of eating pathology: The moderating role of self-compassion. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22, 1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan-Lowes, K. L., Thøgersen-Ntoumani, C., Howell, J., Khossousi, V., & Egan, S. J. (2023). Self-compassion and clinical eating disorder symptoms: A systematic review. Clinical Psychologist, 27(3), 269–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, K. (2011). Self-Compassion, self-esteem, and well-being. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 5(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, K., Rude, S., & Kirkpatrick, K. (2007). An examination of self-compassion in relation to positive psychological functioning and personality traits. Journal of Research in Personality, 41(4), 908–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, K. D. (2003a). Self compassion: An alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self and Identity, 2, 85–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, K. D. (2003b). The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self and Identity, 2, 223–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, K. D., & Germer, C. K. (2013). A pilot study and randomized controlled trial of the mindful self-compassion program. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 69(1), 28–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, K. D., & Vonk, R. (2009). Self-compassion versus global self-esteem: Two different ways of relating to oneself. Journal of personality, 77(1), 23–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadimitriou, A., & Karakasidou, E. (2025). The appearance of disordered eating behaviors in adulthood through low self-esteem and mental health in childhood. Future, 3(3), 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peschel, S. K. V., Sigrist, C., Voss, C., Fürtjes, S., Berwanger, J., Ollmann, T. M., Kische, H., Rückert, F., Koenig, J., & Beesdo-Baum, K. (2024). Subclinical patterns of disordered eating behaviors in the daily life of adolescents and young adults from the general population. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 18, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pullmer, R., Coelho, J. S., & Zaitsoff, S. L. (2019). Kindness begins with yourself: The role of self-compassion in adolescent body satisfaction and eating pathology. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 52(7), 809–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J., Wu, Y., Liu, F., Zhu, Y., Jin, H., Zhang, H., Wan, Y., Li, C., & Yu, D. (2022). An update on the prevalence of eating disorders in the general population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eating and Weight Disorders: EWD, 27(2), 415–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricciardelli, L., & McCabe, M. (2004). A biopsychosocial model of disordered eating and the pursuit of muscularity in adolescent boys. Psychological Bulletin, 130(2), 179–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, T. F., & Machado, P. P. P. (2025). Emotion regulation and eating disorders—The current status of research and future directions. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 38(6), 421–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosales Cadena, S., Iyer, A., Webb, T. L., & Millings, A. (2024). Understanding the relationship between self-compassion and body dissatisfaction: A longitudinal study. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 54(9), 1312–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selby, E. A., Bodell, L. P., & Haynos, A. F. (2024). Positive emotion dysregulation in eating disorders and dysregulated eating behaviours. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1437889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, J. R., & Anderson, D. A. (2003). The effects of restraint, gender, and body mass index on the accuracy of self-reported weight. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 34(1), 177–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smink, F., Van Hoeken, D., & Hoek, H. (2012). Epidemiology of eating disorders: Incidence, prevalence and mortality rates. Current Psychiatry Reports, 14(4), 406–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolak, L., & Levine, M. (2015). The Wiley handbook of eating disorders. Wiley Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer, E. A., Appleby, P. N., Davey, G. K., & Key, T. J. (2002). Validity of self-reported height and weight in 4808 EPIC-Oxford participants. Public Health Nutrition, 5(4), 561–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strother, E., Lemberg, R., Stanford, S., & Turberville, D. (2012). Eating disorders in men: Underdiagnosed, undertreated, and misunderstood. Eating Disorders, 20(5), 346–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stutts, L. A., & Blomquist, K. K. (2018). The moderating role of self-compassion on weight and shape concerns and eating pathology. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 51, 879–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, M., Daiss, S., & Krietsch, K. (2015). Associations among self-compassion, mindful eating, eating disorder symptomatology, and body mass index in college students. Translational Issues in Psychological Science, 1(3), 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terry, M., & Leary, M. (2011). Self-compassion, self-regulation, and health. Self and Identity, 10(3), 352–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thome, J., & Espelage, D. L. (2004). Relations among exercise, coping, disordered eating, and psychological health among college students. Eating Behaviors, 5(4), 337–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Türk, F. (2024). How can we further explore the link between self-criticism and self-compassion, and disordered eating? International Journal of Eating Disorders, 57, 1646–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tylka, T. L. (2011). Positive psychology perspectives on body image. In T. F. Cash, & L. Smolak (Eds.), Body image: A handbook of science, practice, and prevention (2nd ed., pp. 56–64). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Varsou, E., & Trikkas, G. (1991, May 15–19). The EDI, EAT-26 and BITE in a Greek population: Preliminary findings. 12th Panhellenic Psychiatric Conference, Volos, Greece. [Google Scholar]

- Vlachakis, D., & Vlachakis, C. (2014). Prevalence of disordered eating attitudes in young adults (No. e538v1). PeerJ PrePrints. [Google Scholar]

- Wasylkiw, L., MacKinnon, A., & MacLellan, A. (2012). Exploring the link between self-compassion and body image in university women. Body Image, 9(2), 236–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(6), 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. (1995). Physical status: The use and interpretation of anthropometry. Report of a WHO expert committee (WHO technical report series No. 854). World Health Organization. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/37003 (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- Yannakoulia, M., Matalas, A., Yiannakouris, N., Papoutsakis, C., Passos, M., & Klimis-Zacas, D. (2004). Disordered eating attitudes: An emerging health problem among Mediterranean adolescents. Eating and Weight Disorders—Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity, 9(2), 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, R., Zhang, L., Liu, Z., & Cao, B. (2025). Emotion regulation difficulties and disordered eating in adolescents and young adults: A meta-analysis. Journal of Eating Disorders, 13, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).