Experimentation with Illicit Drugs Strongly Predicts Electronic Cigarette Use: A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

The Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants, Procedures, and Design

2.2. Dependent Variable

2.3. Independent Variables

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

Prevalence and Bivariate Analyses

4. Discussion

Implications, Future Directions and Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EC | E-cigarette |

| PeNSE | Pesquisa Nacional de Saúde do Escolar |

| IBGE | Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística |

| OR | Odds ratios |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| CI | Confidence interval |

References

- Adekeye, O. T., Boltz, M., Jao, Y. L., Branstetter, S., & Exten, C. (2025a). Vaping in the digital age: How social media influences adolescent attitudes and beliefs about e-cigarette use. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Use, 30(1), 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adekeye, O. T., Marquez, F., Abuga, C., Oclaray, T. K., Gonyoe, G., & Mumba, M. N. (2025b). Exploring social media’s influence on adolescents’ curiosity about e-cigarette use: A secondary data analysis. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Use, 30(5), 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azagba, S., Mensah, N. A., Shan, L., & Latham, K. (2020). Bullying victimization and e-cigarette use among middle and high school students. Journal of School Health, 90(7), 545–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baiden, P., Cavazos-Rehg, P., Szlyk, H. S., Onyeaka, H. K., Peoples, J. E., Kasson, E., & Muoghalu, C. (2023). Association between sexual violence victimization and electronic vaping product use among adolescents: Findings from a population-based study. Substance Use & Misuse, 58(5), 637–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, B., & Li, J. (2020). The electronic cigarette epidemic in youth and young adults: A practical review. JAAPA, 33(3), 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camenga, D. R., Fiellin, L. E., Pendergrass, T., Miller, E., Pentz, M. A., & Hieftje, K. (2018). Adolescents’ perceptions of flavored tobacco products, including e-cigarettes: A qualitative study to inform FDA tobacco education efforts through videogames. Addictive Behaviors, 82, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, R., Pierce, J. P., Leas, E. C., White, M. M., Kealey, S., Strong, D. R., Trinidad, D. R., Benmarhnia, T., & Messer, K. (2020). Use of electronic cigarettes to aid long-term smoking cessation in the United States: Prospective evidence from the PATH cohort study. American Journal of Epidemiology, 189(12), 1529–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H. G., Lizhnyak, P. N., & Richter, N. (2023). Mutual pathways between peer and own e-cigarette use among youth in the United States: A cross-lagged model. BMC Public Health, 23, 1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos Maximino, G., Andrade, A. L. M., de Andrade, A. G., & de Oliveira, L. G. (2023). Profile of Brazilian undergraduates who use electronic cigarettes: A cross-sectional study on forbidden use. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 23(1), 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erhabor, J., Yao, Z., Tasdighi, E., Shahawy, O. E., Benjamin, E. J., Bhatnagar, A., & Blaha, M. J. (2025). Association of e-cigarette use, psychological distress, and substance use: Insights from the all of us research program. Addictive Behaviors, 166, 108322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ESPAD Group. (2025). Key findings from the 2024 European school survey project on alcohol and other drugs (ESPAD). European Union Drugs Agency. [Google Scholar]

- Gaddy, M. Y., Vasquez, D., & Brown, L. D. (2022). Predictors of e-cigarette initiation and use among middle school youth in a low-income predominantly Hispanic community. Frontiers in Public Health, 10, 883362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, E., Chokshi, B., Melendez-Torres, G. J., Rios, A., Jelley, M., & Lewis-O’Connor, A. (2024). Effectiveness of trauma-informed care implementation in health care settings: Systematic review of reviews and realist synthesis. The Permanente Journal, 28(1), 135–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, A. L., Cha, S., Jacobs, M. A., Edwards, G., Funsten, A. L., & Papandonatos, G. D. (2025). Adverse childhood experiences are associated with e-cigarette abstinence in a vaping cessation randomized clinical trial among adolescents. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 77(2), 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groom, A. L., Vu, T.-H. T., Landry, R. L., Kesh, A., Hart, J. L., Walker, K. L., Wood, L. A., Robertson, R. M., & Payne, T. J. (2021). The influence of friends on teen vaping: A mixed-methods approach. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(13), 6784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. (2021). PeNSE microdados. Available online: https://www.ibge.gov.br/estatisticas/downloads-estatisticas.html?caminho=pense/2019/microdados/ (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. (2022). Pesquisa nacional de saúde do escolar. IBGE. Available online: https://biblioteca.ibge.gov.br/visualizacao/livros/liv101955.pdf (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- Izquierdo-Condoy, J. S., Ruiz Sosa, K., Salazar-Santoliva, C., Restrepo, N., Olaya-Villareal, G., Castillo-Concha, J. S., Loaiza-Guevara, V., & Ortiz-Prado, E. (2025). E-cigarette use among adolescents in Latin America: A systematic review of prevalence and associated factors. Preventive Medicine Reports, 49, 102952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenssen, B. P., Walley, S. C., Groner, J. A., Rahmandar, M., Boykan, R., Mih, B., Marbin, J. N., & Caldwell, A. L. (2019). E-cigarettes and similar devices. Pediatrics, 143(2), e20183652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J., Lee, S., & Chun, J. (2022). An international systematic review of prevalence, risk, and protective factors associated with young people’s e-cigarette use. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(18), 11570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolokythas, A. (2022). The dangers of e-cigarette use among our youth: A public health issue and our role as health care providers. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology and Oral Radiology, 134(5), 503–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koob, G. F., & Volkow, N. D. (2016). Neurobiology of addiction: A neurocircuitry analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry, 3(8), 760–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, L., Conti, A. A., Hemmati, Z., & Baldacchino, A. M. (2023). The prospective association between the use of e-cigarettes and other psychoactive substances in young people: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 153, 105392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T. T. T. (2023). Key risk factors associated with electronic nicotine delivery systems use among adolescents. JAMA Network Open, 6(10), e2337101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malta, D. C., Oliveira, W. A. D., Prates, E. J. S., Mello, F. C. M. D., Moutinho, C. D. S., & Silva, M. A. I. (2022). Bullying entre adolescentes brasileiros: Evidências das pesquisas nacionais de saúde do escolar, Brasil, 2015 e 2019. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem, 30, e3679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWhirter, J. J., McWhirter, B. T., McWhirter, E. H., & McWhirter, A. C. (2017). At-risk youth: A comprehensive response for counselors, teachers, psychologists, and human service professionals (6th ed.). Cengage Learning. [Google Scholar]

- Meehan, J., Heffron, M., Avoy, H. M., Reynolds, C., Kyne, L., & Cox, D. W. (2024). The adverse effects of vaping in young people. Global Pediatrics, 9, 100190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (US), Office on Smoking and Health. (2016). E-cigarette use among youth and young adults: A report of the Surgeon General. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US). Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538680/ (accessed on 7 June 2025).

- National Health Surveillance Agency (Brazil). (2009). Resolução da Diretoria Colegiada—RDC nº 46, de 28 de agosto de 2009 (Resolution of the Collegiate Board—RDC No. 46, of August 28, 2009). Diário Oficial da União. [Google Scholar]

- National Health Surveillance Agency (Brazil). (2024). Resolução da Diretoria Colegiada—RDC nº 855, de 19 de abril de 2024 (Resolution of the Collegiate Board—RDC No. 855, of April 19, 2024). Diário Oficial da União. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, M. M. D., Campos, M. O., Andreazzi, M. A. R. D., & Malta, D. C. (2017). Características da Pesquisa Nacional de Saúde do Escolar—PeNSE. Epidemiologia e Serviços de Saúde, 26(3), 605–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park-Lee, E., Jamal, A., Cowan, H., Cullen, K. A., Neff, L. J., & King, B. A. (2024). Notes from the field: E-cigarette and nicotine pouch use among middle and high school students—United States, 2024. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 73(35), 774–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patanavanich, R., Aekplakorn, W., Glantz, S., & Kalayasiri, R. (2021). Use of e-cigarettes and associated factors among youth in Thailand. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention, 22(7), 2199–2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettigrew, S., Santos, J. A., Li, Y., Jun, M., Anderson, C., & Jones, A. (2023). Factors contributing to young people’s susceptibility to e-cigarettes in four countries. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 250, 109944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Portes Ribeiro, L. E., Sorio Flor, L., Lopes, C. A., & Mabotti Costa Leite, F. (2025). Illicit drug use and sociodemographic correlates among adolescents in a Brazilian metropolitan region: A school-based cross-sectional study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(9), 1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salari, N., Rahimi, S., Darvishi, N., Abdolmaleki, A., & Mohammadi, M. (2024). The global prevalence of e-cigarettes in youth: A comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis. Public Health in Practice, 7, 100506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, J. R., Malta, D. C., Fagundes, A. A. d. P., Pavanello, R., Bredt, G. L., & Rocha, M. d. S. (2024). Brazilian society of cardiology position statement on the use of electronic nicotine delivery systems—2024. Arquivos Brasileiros de Cardiologia, 121(2), e20240063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S. H. (2021). Preventing e-cigarette use among high-risk adolescents: A trauma-informed prevention approach. Addictive Behaviors, 115, 106795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, A. L. O. D., & Moreira, J. C. (2019). The ban of electronic cigarettes in Brazil: Success or failure? A proibição dos cigarros eletrônicos no Brasil: Sucesso ou fracasso? Ciencia & Saúde Coletiva, 24(8), 3013–3024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreeramareddy, C. T., Acharya, K., & Manoharan, A. (2022). Electronic cigarettes use and ‘dual use’ among the youth in 75 countries: Estimates from Global Youth Tobacco Surveys (2014–2019). Scientific Reports, 12, 20967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J., Xi, B., Ma, C., Zhao, M., & Bovet, P. (2022). Prevalence of e-cigarette use and its associated factors among youths aged 12 to 16 years in 68 countries and territories: Global youth tobacco survey, 2012–2019. American Journal of Public Health, 112(4), 650–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunday, S., Clancy, L., & Hanafin, J. (2023). The associations of parental smoking, quitting and habitus with teenager e-cigarette, smoking, alcohol and other drug use in GUI cohort ’98. Scientific Reports, 13, 20105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahniyath, U., Begum, S. S., & Unnisa, M. (2024). Vaping trends among adolescents: Understanding the rise of e cigarettes in youth culture. Journal of Advances in Medical and Pharmaceutical Sciences, 26(8), 48–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tercyak, K. P., Phan, L., Gallegos-Carrillo, K., Mays, D., Audrain-McGovern, J., Rehberg, K., Li, Y., Cartujano-Barrera, F., & Cupertino, A. P. (2021). Prevalence and correlates of lifetime e-cigarette use among adolescents attending public schools in a low income community in the US. Addictive Behaviors, 114, 106738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toledo, J. P. C. (2025). Vaping illusions: The hidden risks of e-cigarette use among young Filipinos and adolescents in Latin America. International Journal of Cardiology Cardiovascular Risk and Prevention, 24, 200375. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/40007582 (accessed on 17 May 2025). [CrossRef]

- Vidourek, R. A., King, K. A., Burbage, M., & Okuley, B. (2018). Impact of parenting behaviors on recent alcohol use among African American students. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 35(3), 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2003). WHO framework convention on tobacco control. World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Yockey, R. A., Chaliawala, K., Vidourek, R. A., & King, K. (2023). School factors associated with past 30-day e-cigarette use among Hispanic youth. The Journal of School Nursing, 41(4), 426–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| E-Cigarette Experimentation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | X2 | p | |

| Age group | 0.557 | 0.455 | ||

| 13–15 | 2337 (55.43%) | 18,036 (56.04%) | ||

| 16–17 | 1879 (44.57%) | 14,149 (43.96%) | ||

| Gender | 107.010 | <0.001 | ||

| Male | 2549 (60.36%) * | 16,787 (51.91%) | ||

| Female | 1674 (39.64%) | 15,551 (48.09%) | ||

| Urban area | 30.831 | <0.001 | ||

| No | 76 (1.79%) | 1100 (3.39%) | ||

| Yes | 4160 (98.21%) * | 31,323 (96.61%) | ||

| Ethnicity | 100.376 | <0.001 | ||

| Indigenous | 93 (2.26%) | 855 (2.69%) | ||

| Asian | 151 (3.66%) | 1163 (3.66%) | ||

| Black | 434 (10.53%) | 3948 (12.42%) | ||

| Caucasian | 1903 (46.17%) * | 12,135 (38.18%) | ||

| Pardo (mixed race) | 1541 (37.38%) | 13,680 (43.04%) | ||

| Public school | 530.546 | <0.001 | ||

| Yes | 1687 (39.83%) | 18,964 (58.49%) | ||

| No | 2549 (60.17%) * | 13,459 (41.51%) | ||

| E-Cigarette Experimentation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | X2 | p | |

| Days got drunk in a month | 539.426 | <0.001 | ||

| 6 or more | 1265 (31.17%) * | 5265 (17.82%) | ||

| 1–5 | 1915 (47.18%) | 13,668 (46.27%) | ||

| Never | 879 (21.66%) | 10,606 (35.91%) | ||

| Problems Drinking | 205.865 | <0.001 | ||

| Yes | 1318 (32.47%) * | 6583 (22.29%) | ||

| No | 2741 (67.53%) | 22,957 (77.71%) | ||

| Parent/Guardians drink | 96.374 | <0.001 | ||

| I do not know | 82 (1.94%) | 769 (2.38%) | ||

| Only one of them | 1309 (30.97%) | 10,373 (32.05%) | ||

| Both | 1917 (45.35%) * | 12,380 (38.25%) | ||

| No one | 919 (21.74%) | 8844 (27.32%) | ||

| Cigarette experimentation | 177.226 | <0.001 | ||

| Yes | 2549 (60.19%) * | 15,977 (49.31%) | ||

| No | 1686 (39.81%) | 16,422 (50.69%) | ||

| Friends consumed alcohol last month | 552.404 | <0.001 | ||

| Yes | 3507 (82.99%) * | 21,010 (64.91%) | ||

| No | 719 (17.01%) | 11,358 (35.09%) | ||

| Use of other drugs | 463.591 | <0.001 | ||

| Yes | 2083 (49.33%) * | 10,535 (32.58%) | ||

| No | 2140 (50.67%) | 21,804 (67.42%) | ||

| Consumed alcohol last month | 776.222 | <0.001 | ||

| Yes | 3181 (78.43%) * | 16,363 (55.42%) | ||

| No | 875 (21.57%) | 13,165 (44.58%) | ||

| Parents/guardian smoke | 4.568 | 0.206 | ||

| I do not know | 85 (2.01%) | 573 (1.77%) | ||

| Both | 201 (4.75%) | 1521 (4.70%) | ||

| Only one of them | 950 (22.43%) | 6894 (21.28%) | ||

| No | 3000 (70.82%) | 23,408 (72.26%) | ||

| Friends smoke | 970.998 | <0.001 | ||

| Yes | 3017 (71.31%) * | 14,845 (45.84%) | ||

| No | 1214 (28.69%) | 17,536 (54.16%) | ||

| Physical abuse at home | 47.563 | <0.001 | ||

| Yes | 1396 (33.22%) * | 9009 (28.10%) | ||

| No | 2806 (66.78%) | 23,047 (71.90%) | ||

| Sexual abuse | 11.443 | <0.001 | ||

| Yes | 494 (11.77%) * | 3231 (10.08%) | ||

| No | 3703 (88.23%) | 28,810 (89.92%) | ||

| Cyberbullying victim | 14.875 | <0.001 | ||

| Yes | 846 (20.02%) * | 5682 (17.61%) | ||

| No | 3379 (79.98%) | 26,592 (82.39%) | ||

| Bullying victim | 7.657 | 0.006 | ||

| Yes | 1877 (44.43%) * | 13,629 (42.19%) | ||

| No | 2348 (55.57%) | 18,676 (57.81%) | ||

| Community violence | 174 | 0.895 | ||

| Yes | 546 (12.99%) | 4193 (13.06%) | ||

| No | 3657 (87.01%) | 27,904 (86.94%) | ||

| β | ORc | p | 95%CI | β | ORa | p | 95%CI | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L | U | L | U | |||||||

| Friends Smoke (Yes) | 0.095 | 2.262 | <0.001 | 2.078 | 2.464 | 0.100 | 2.297 | <0.001 | 2.112 | 2.499 |

| Public school (Yes) | −0.816 | 0.470 | <0.001 | 0.437 | 0.507 | −0.832 | 0.454 | <0.001 | 0.422 | 0.487 |

| Alcohol Last Month (Yes) | 0.754 | 1.839 | <0.001 | 1.674 | 2.021 | 0.791 | 1.851 | <0.001 | 1.687 | 2.031 |

| Gender (Male) | 0.609 | 1.676 | <0.001 | 1.550 | 1.813 | 0.616 | 1.649 | <0.001 | 1.526 | 1.781 |

| Days Got Drunk (6 or more) | 0.517 | 1.157 | 0.001 | 1.061 | 1.263 | 0.500 | 1.208 | <0.001 | 1.110 | 1.315 |

| Days Got Drunk (Never) | −0.146 | 0.857 | 0.001 | 0.780 | 0.942 | −0.189 | 0.852 | <0.001 | 0.777 | 0.934 |

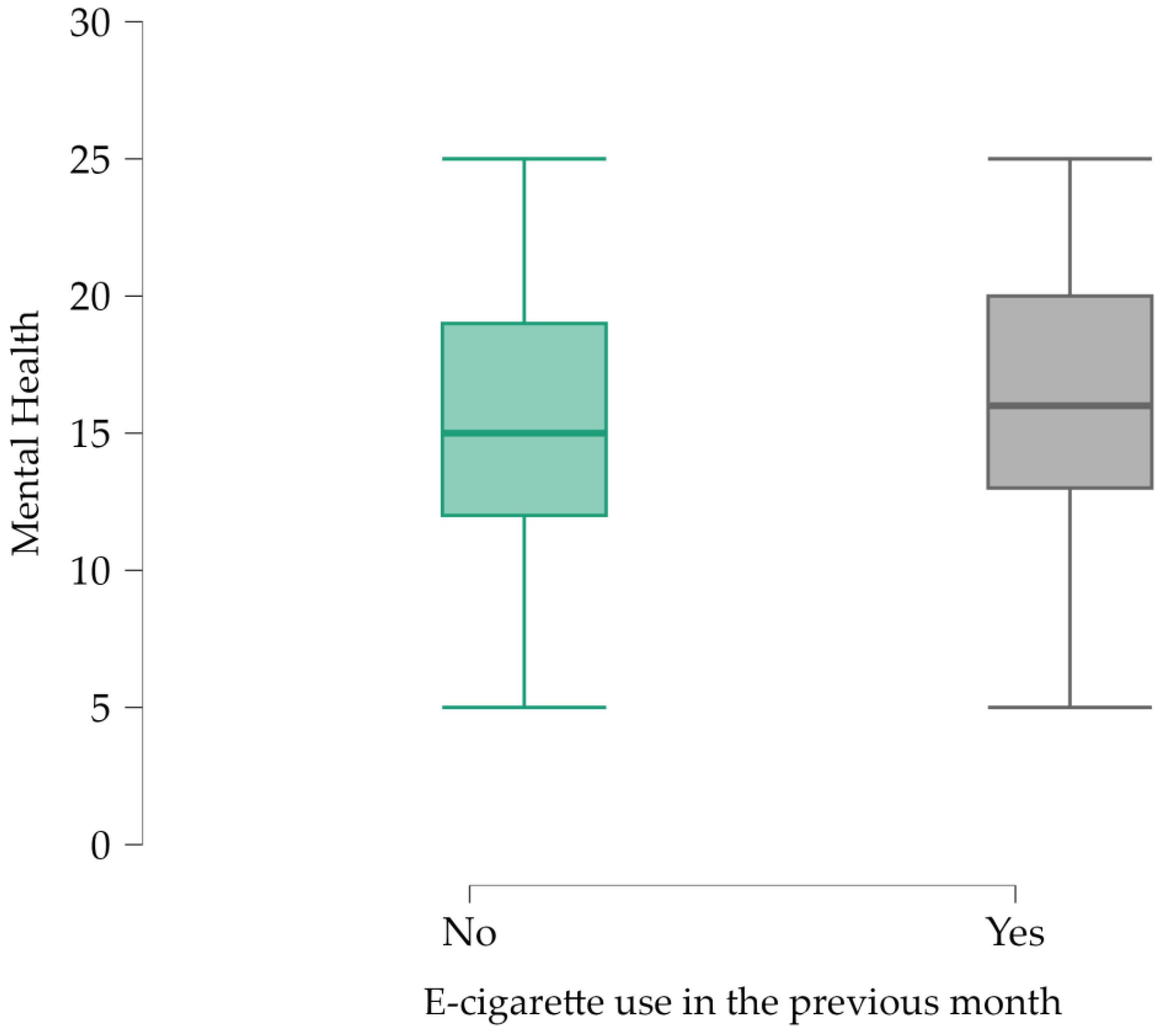

| Mental Health score | 0.154 | 1.021 | <0.001 | 1.012 | 1.030 | 0.160 | 1.022 | <0.001 | 1.013 | 1.031 |

| Other Drugs (Yes) | 0.187 | 1.206 | <0.001 | 1.116 | 1.303 | 0.194 | 1.215 | <0.001 | 1.126 | 1.311 |

| Urban (Yes) | 0.533 | 1.703 | <0.001 | 1.312 | 2.211 | 0.536 | 1.709 | <0.001 | 1.328 | 2.201 |

| Physical Abuse at Home (Yes) | 0.157 | 1.170 | <0.001 | 1.084 | 1.262 | 0.156 | 1.168 | <0.001 | 1.084 | 1.259 |

| Problems Drinking (Yes) | 0.134 | 1.143 | <0.001 | 1.056 | 1.238 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Friends Drank Last Month (Yes) | 0.173 | 1.188 | 0.002 | 1.067 | 1.324 | 0.178 | 1.195 | 0.001 | 1.075 | 1.328 |

| Ethnicity (Black) | −0.130 | 0.878 | 0.228 | 0.710 | 1.085 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Ethnicity (Caucasian) | 0.053 | 1.055 | 0.582 | 0.873 | 1.275 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Ethnicity (Indigenous) | −0.110 | 0.896 | 0.466 | 0.668 | 1.203 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Ethnicity (Pardo or mixed race) | −0.083 | 0.920 | 0.392 | 0.761 | 1.113 | - | - | - | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Welter Wendt, G.; Ribeiro Pinno, B.; Rauber Suzaki, P.A.; do Nascimento Teixeira, I.; Dantas Silva, W.A.; Alckmin-Carvalho, F.; Do Bú, E. Experimentation with Illicit Drugs Strongly Predicts Electronic Cigarette Use: A Cross-Sectional Study. Psychol. Int. 2025, 7, 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/psycholint7040098

Welter Wendt G, Ribeiro Pinno B, Rauber Suzaki PA, do Nascimento Teixeira I, Dantas Silva WA, Alckmin-Carvalho F, Do Bú E. Experimentation with Illicit Drugs Strongly Predicts Electronic Cigarette Use: A Cross-Sectional Study. Psychology International. 2025; 7(4):98. https://doi.org/10.3390/psycholint7040098

Chicago/Turabian StyleWelter Wendt, Guilherme, Bianca Ribeiro Pinno, Paula Andrea Rauber Suzaki, Iara do Nascimento Teixeira, Washington Allysson Dantas Silva, Felipe Alckmin-Carvalho, and Emerson Do Bú. 2025. "Experimentation with Illicit Drugs Strongly Predicts Electronic Cigarette Use: A Cross-Sectional Study" Psychology International 7, no. 4: 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/psycholint7040098

APA StyleWelter Wendt, G., Ribeiro Pinno, B., Rauber Suzaki, P. A., do Nascimento Teixeira, I., Dantas Silva, W. A., Alckmin-Carvalho, F., & Do Bú, E. (2025). Experimentation with Illicit Drugs Strongly Predicts Electronic Cigarette Use: A Cross-Sectional Study. Psychology International, 7(4), 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/psycholint7040098