Abstract

Lecythidaceae species are known worldwide for their ability to produce edible nuts of high nutritional value, such as Brazil nuts, and are also used in traditional medicine in countries across America, Asia, and Africa. The potential of these species has aroused interest in their chemical composition, nutritional properties, and biological activities, with emphasis on anti-inflammatory and antinociceptive actions. The objective of this review was to summarize data regarding the anti-inflammatory and antinociceptive activities of Lecythidaceae species, identify the most promising bioactive agents, and elucidate their potential mechanisms of action. This integrative review was conducted by comprehensively searching the main electronic databases for scientific articles, with no restriction on publication date, that were available in full. Based on this survey, thirty-four articles were identified, covering twelve Lecythidaceae species with anti-inflammatory and antinociceptive actions evaluated in in vitro and in vivo models and randomized clinical trials. Studies encompass extracts, fractions, nuts, and isolated compounds, among which the extracts and fractions of Barringtonia angusta Kurz, Couroupita guianensis Aubl., Lecythis pisonis Cambess., and Petersianthus macrocarpus (P. Beauv.) Liben demonstrated potent inhibition of inflammatory mediators through suppression of gene expression in vitro and in vivo, acting via blockade of the nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (KN-κB) signaling pathway. This finding highlights a relevant molecular mechanism by which Lecythidaceae species may exert their anti-inflammatory potential and supports further studies focused on isolating active fractions and elucidating possible synergistic effects. Ethnopharmacological and chemical composition data are also presented and discussed within the scope of their biological applications, highlighting the therapeutic potential of Lecythidaceae species and identifying promising candidates for future development of novel anti-inflammatory phytopharmaceuticals.

1. Introduction

The inflammatory process is a complex immune response triggered by tissue injury or pathogen attacks, characterized by coordinated cellular and vascular events that recruit defense cells to the affected site [1]. This response triggers the release of inflammatory mediators, which function to restore tissue structure and function. While acute inflammation develops rapidly and serves as a protective mechanism, its persistence can result in pain and tissue damage, ultimately progressing to chronic inflammation, a condition that is more difficult to treat and is linked to chronic diseases, including cancer and autoimmune and cardiovascular diseases [2,3,4].

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are currently the most commonly used medications in clinical practice. Although effective, prolonged use of NSAIDs is associated with significant adverse effects, including gastrointestinal, renal, cardiovascular, and hematologic complications [3]. These risks limit their use, particularly in elderly patients, individuals with renal failure or cardiovascular complications, and pregnant women [1,3]. This scenario underscores the need for safe and effective therapeutic alternatives capable of modulating the inflammatory response with a lower risk of side effects.

It has been shown that plant-derived secondary metabolites can directly or indirectly interfere with inflammatory pathway molecules and/or mechanisms by modulating these inflammatory mediators [5]. Plants represent a promising source for discovering bioactive compounds with potential for greater efficacy and lower toxicity than conventional drugs. While ethnopharmacology provides invaluable leads for discovering therapeutics, it often does not elucidate the precise pharmacological mechanisms underlying the effects of these agents [6]. Thus, a vast field of study is opened up to understand the cellular and molecular mechanisms behind the therapeutic action of a given bioactive agent. If an agent exerts anti-inflammatory action, it may also help identify new biological targets for the development of safe therapeutic strategies for the treatment of inflammatory disorders [5].

This is the case of the family Lecythidaceae, with species appearing in many places in the world and several reports of its anti-inflammatory, antiarthritic, and analgesic properties, among others. For example, in India and other parts of Asia, various species of this family are used in traditional medicine as antiparasitics, antivenoms, analgesics, anti-inflammatories, and anti-tumor agents, and they are also documented in Ayurvedic literature [5,7,8]. Despite being a family with more than 350 species and around 25 genera spread across the tropical region of the globe, there is still little chemical and biological information about the Lecythidaceae species, especially the species occurring in the American and African continents [9,10].

The purpose of this review is to synthesize data regarding the anti-inflammatory and antinociceptive activities of the species of the family Lecythidaceae, as well as identify the best candidates for the development of anti-inflammatory agents. The identification of mechanisms of action and key compounds is a crucial step towards developing standardized herbal medicines or isolating novel phytopharmaceuticals. To achieve this, we conducted an integrative review following a systematic approach, as detailed in the following section.

2. Materials and Methods

This study is an integrative literature review that aims to gather, analyze, and synthesize evidence from different study designs [11,12]. The methodology was carried out according to the steps defined by Whittemore and Knafl [11]: identification of the problem with the formulation of the research question; search strategy; evaluation of articles using inclusion and exclusion criteria; study selection; data extraction; and presentation. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA 2020) checklist [13] was used as a guide, adapted to the context of integrative reviews [11]. The protocol for this review was registered in the Open Science Framework (OSF) on 19 September 2025, under registration number DOI 10.17605/OSF.IO/X6ESA.

2.1. Formulation of the Research Question

The PICo (Population (P), Phenomenon of Interest (I), and Context (Co)) strategy was adopted to develop the guiding question, according to the model highlighted by Santos, Pimenta, and Nobre [14]. In this work, “P” is the inflammation, “I” is the anti-inflammatory activity and antinociceptive activity, and “Co” is the species of the family Lecythidaceae. Thus, the guiding question was established: “What is the scientific evidence related to the anti-inflammatory and antinociceptive activities of the derivative and components of the species of the Lecythidaceae family?”

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The articles included in this review were subject to the previously defined inclusion criteria, which are as follows: articles available in full, written in English, with studies of anti-inflammatory and/or antinociceptive activities of Lecythidaceae species, and with searches conducted until September 2025. The exclusion criteria were as follows: duplicate articles, theses, dissertations, reviews, book chapters, and articles that did not meet the inclusion criteria and research question.

2.3. Search Strategy

The controlled vocabularies from the Health Sciences Descriptors (DeCS) and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) thesaurus were identified and applied to the following databases: Scopus, Web of Science Core Collection, PubMed/MEDLINE, and ScienceDirect, accessed through the Portal de Periódicos da Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES). The search was conducted until 10 August 2025. To develop the search strategies, controlled and uncontrolled terms (keywords and synonyms) were used in combination with the Boolean operators ‘AND’ and ‘OR’. The final search strategies included the following cross-references: “Lecythidaceae AND Anti-inflammatory” and “Lecythidaceae AND Antinociceptive” for both DeCS and MeSH terms. Table 1 presents the detailed search strategy used for each database.

Table 1.

Search strategy used for each database.

2.4. Study Selection

Initially, the search results were imported and organized using Rayaan reference management software [15], where duplicate studies identified across databases were removed. The first selection step consisted of evaluating the title, keywords, and abstract. Next, the full text of the preselected studies was analyzed. All screening steps were conducted by two independent researchers, and any discrepancies were resolved by a third reviewer [16].

2.5. Data Extraction and Presentation

A standardized data extraction form was used to summarize the following information from each included article: species studied, plant part used (botanical material), administration model, type of bioassay, experimental model, key findings (activity/results), and reference. Subsequently, the articles selected through the inclusion and exclusion criteria were evaluated and classified according to their methodological rigor, considering the characteristics of each study, using integrative review assessment tools. The scientific evidence was summarized, outlined, and presented in Section 3 of this review [11].

3. Results and Discussion

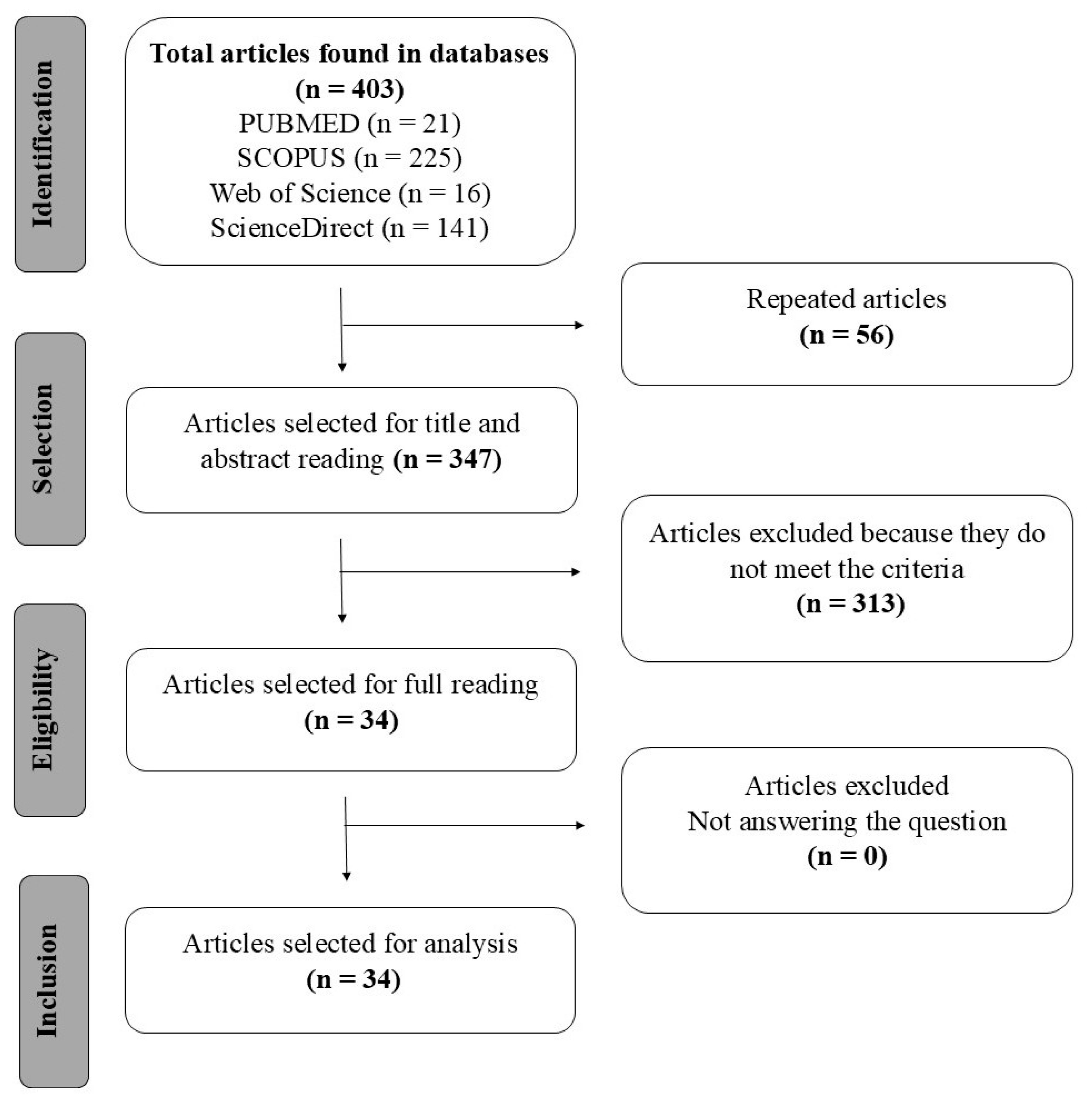

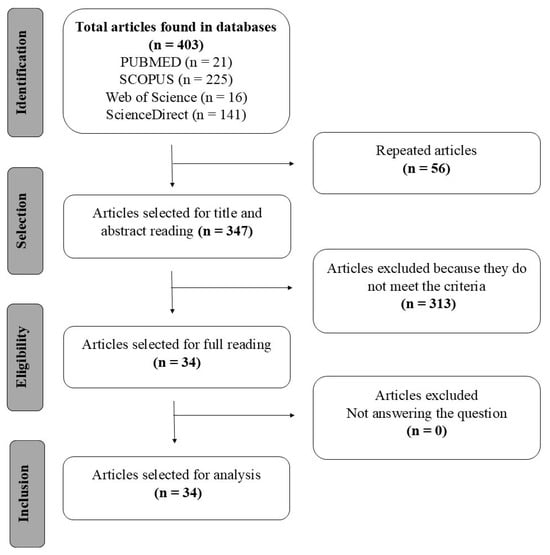

The systematic search identified 403 primary studies in the databases Scopus, PubMed/MEDLINE, Web of Science Core Collection, and ScienceDirect, in which 56 were duplicates, and the remaining 347 were analyzed by reading the title and abstract, resulting in only 34 articles that met the criteria. The selection process of the articles is represented in the flowchart shown in Figure 1, as recommended by the PRISMA methodology [13].

Figure 1.

Flowchart according to PRISMA for selection of articles [17].

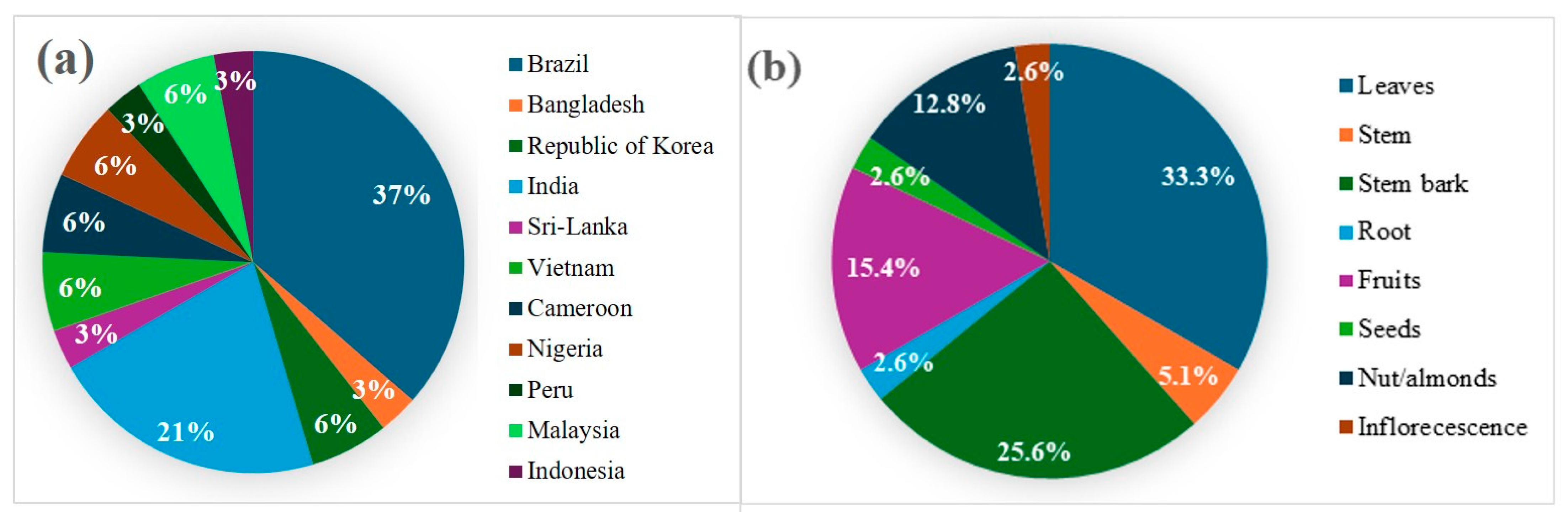

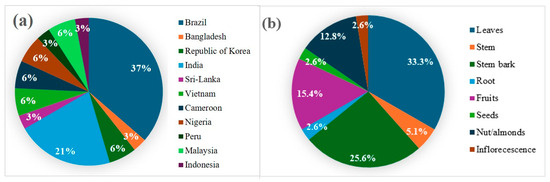

The thirty-four scientific studies compiled in this review include twelve species evaluated for anti-inflammatory and/or antinociceptive actions. As shown in Figure 2a, Brazil was the origin of the largest proportion of studies (37%), followed by India (21%). Research on the Lecythidaceae family has been conducted across South America, Africa, and Asia, indicating that extracts, fractions, or isolated compounds demonstrated anti-inflammatory or antinociceptive activity in 94% of the included studies. Only two studies reported results showing a reduction in inflammatory symptoms based on the wound-healing assay.

Figure 2.

(a) Countries of origin of the studies. (b) Plant material studied in the anti-inflammatory and antinociceptive assays.

Leaves were the most frequently investigated plant material (33.3%), followed by stem bark (25.6%) and fruits (15.4%), as shown in Figure 2b. The study of Lecythidaceae nuts, such as Brazil nuts, is driven by their rich content of bioactive compounds linked to anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activities. Leaves and stem bark of species belonging to this family are also reported to possess medicinal properties, but only about 10% of within the family have been subjected to chemical and biological studies.

We identified that the extraction methods were performed using alcoholic solvents, such as ethanol and methanol, in addition to less frequently used solvents like water. Subsequently, fractionation was typically achieved through adsorption or partition chromatography, beginning with nonpolar solvents and progressing in order of increasing polarity. This process generated multiple fractions enriched with bioactive compounds exhibiting distinct physicochemical properties according to their solubility. Only four studies were conducted using isolated compounds, and one involved a mixture of triterpenes.

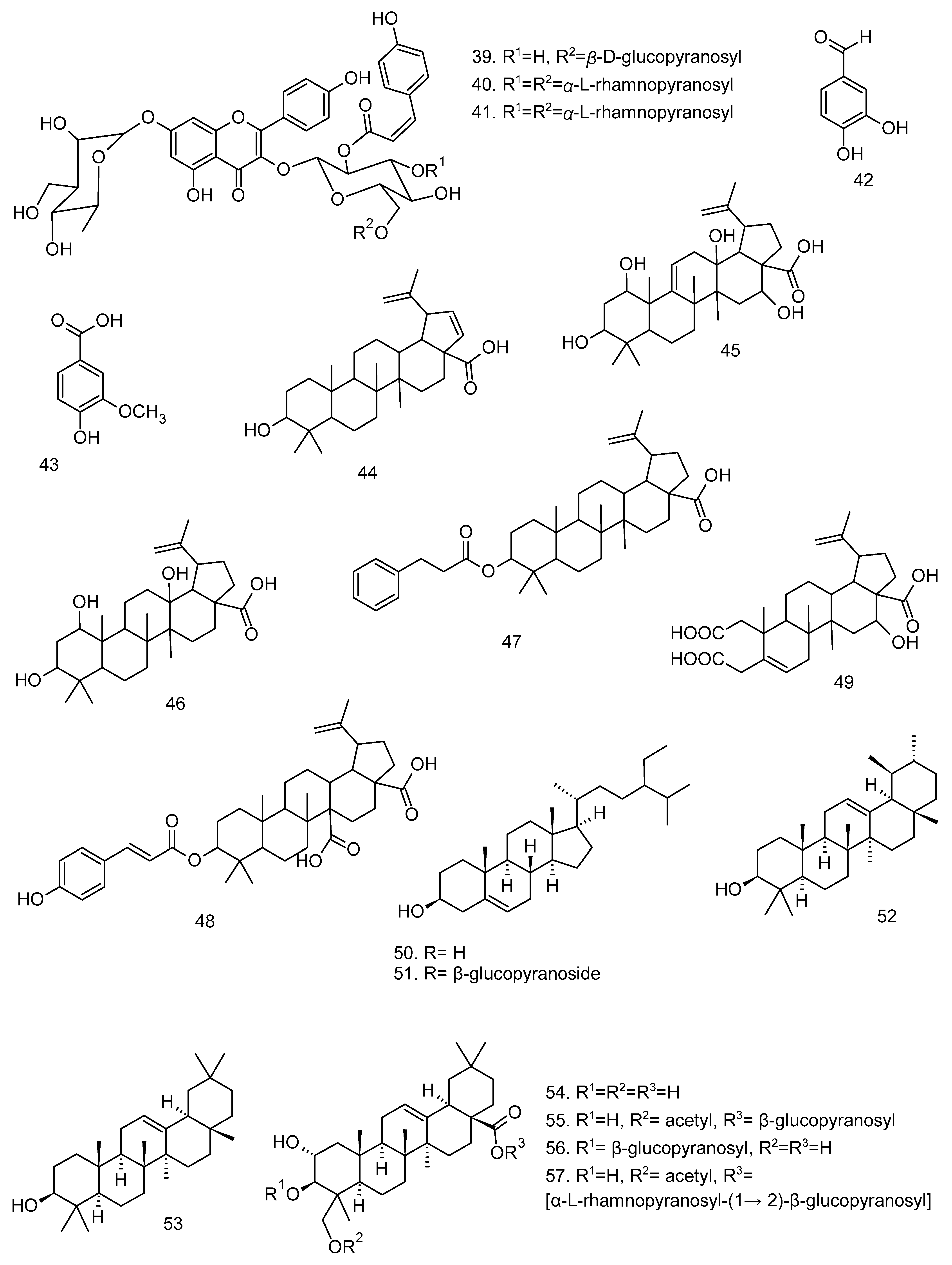

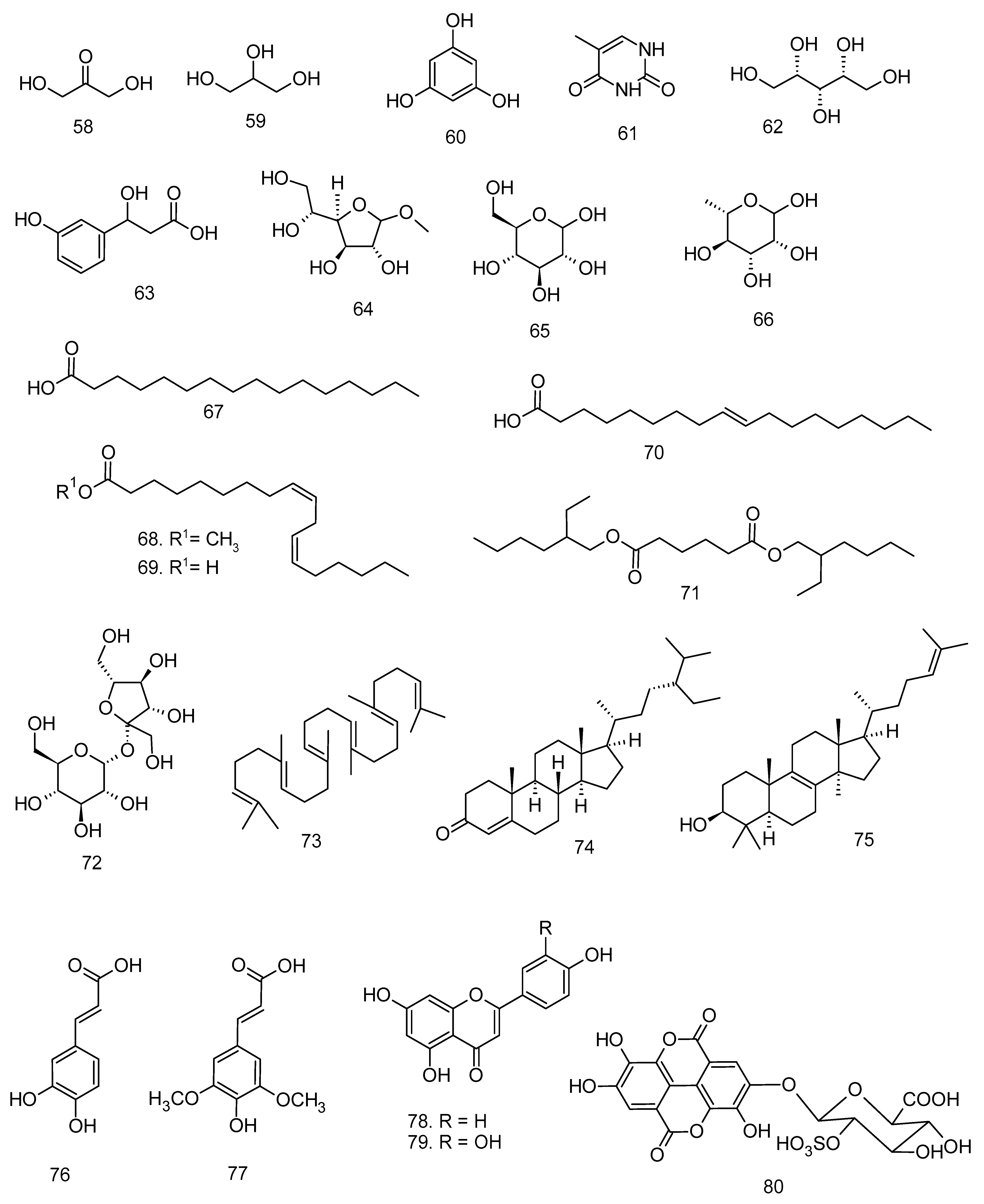

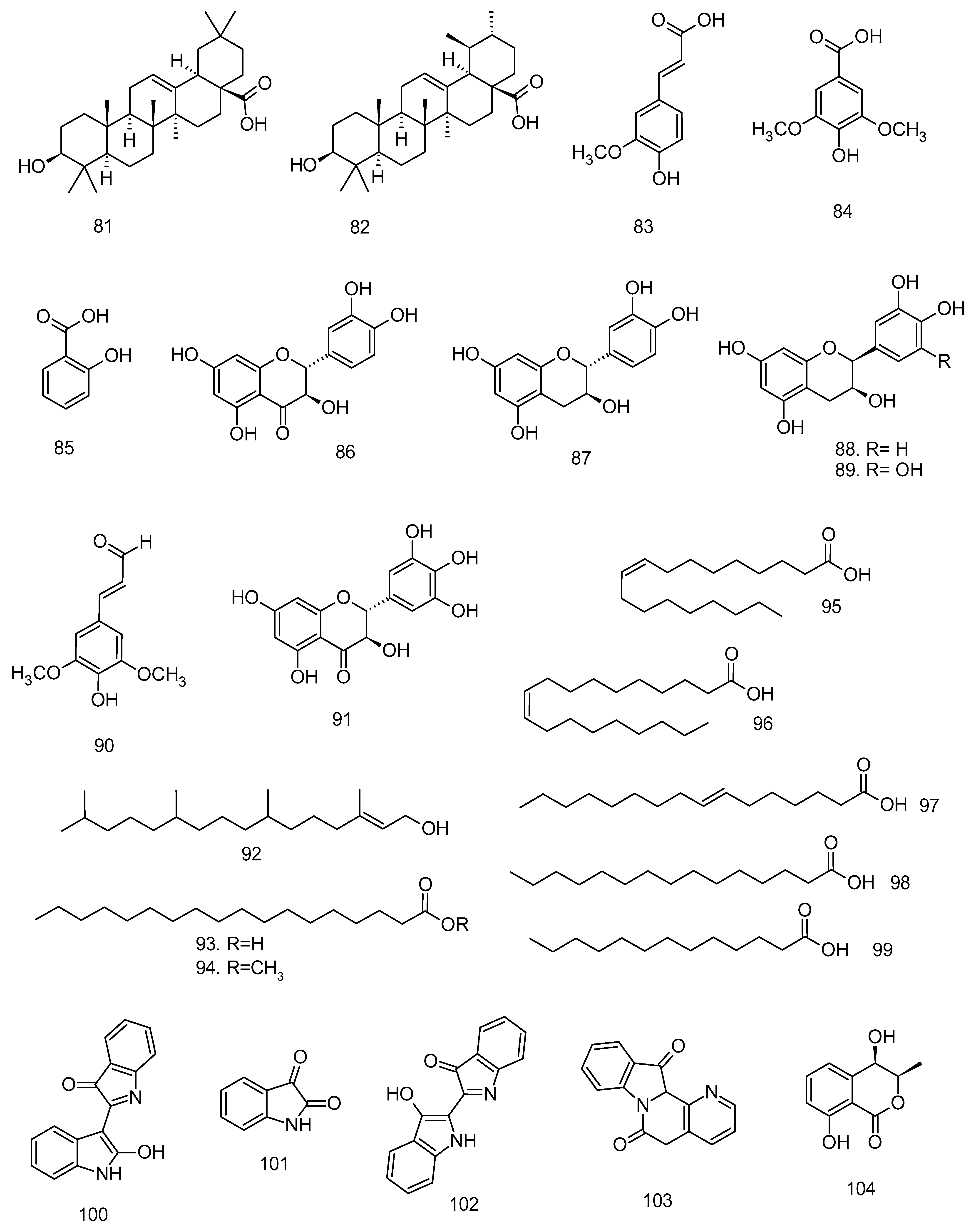

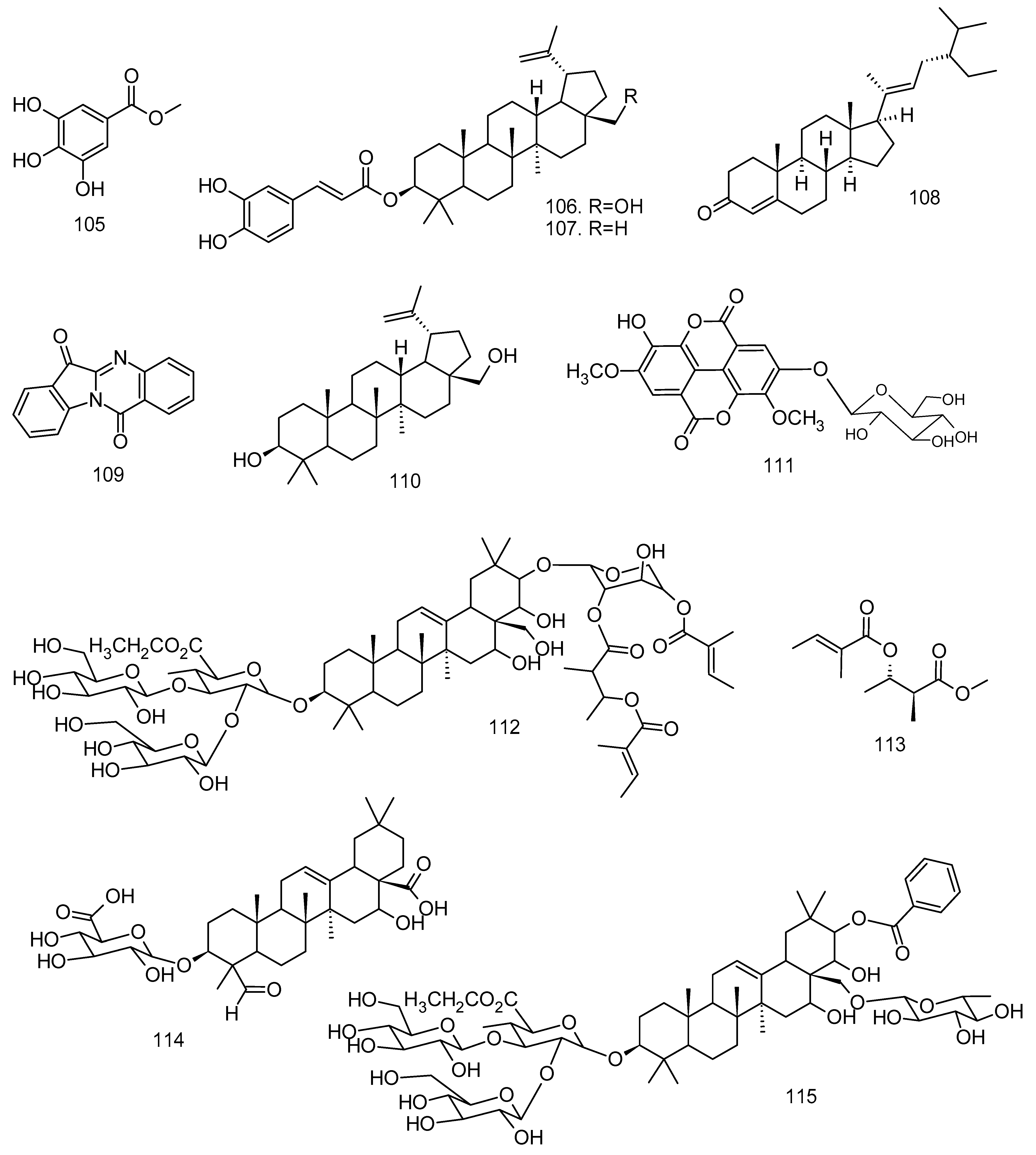

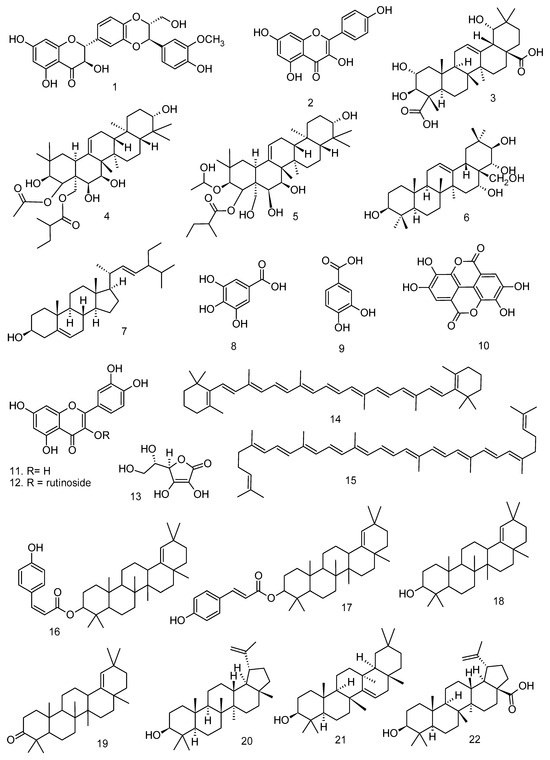

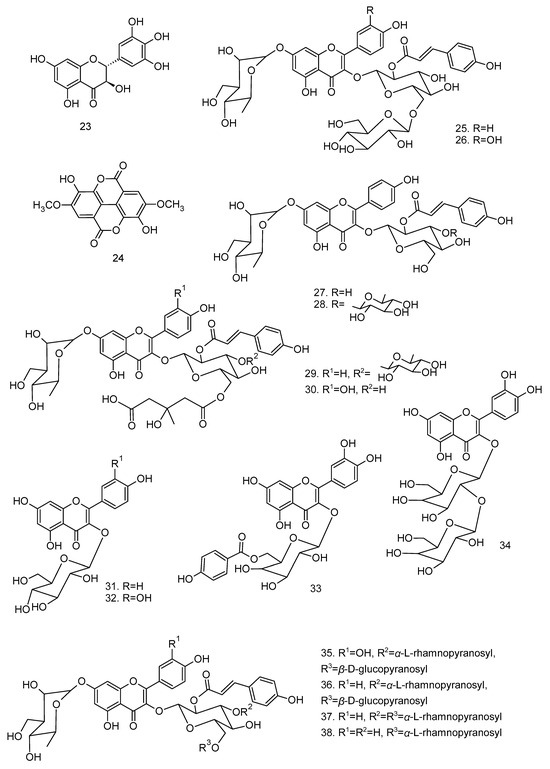

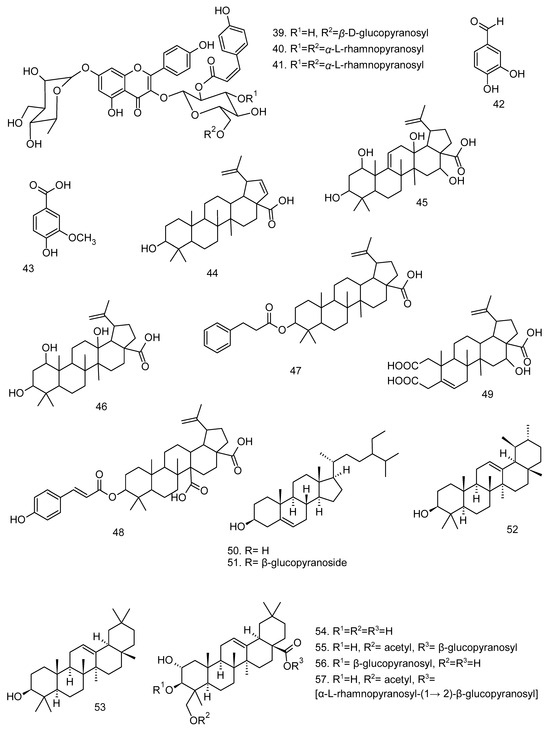

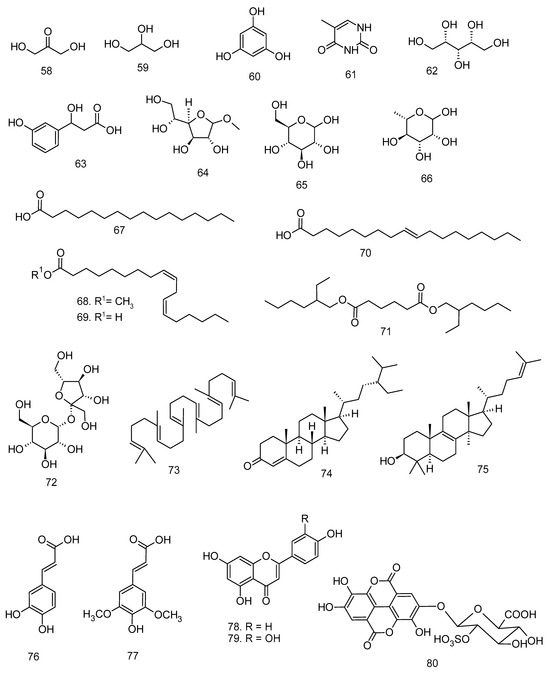

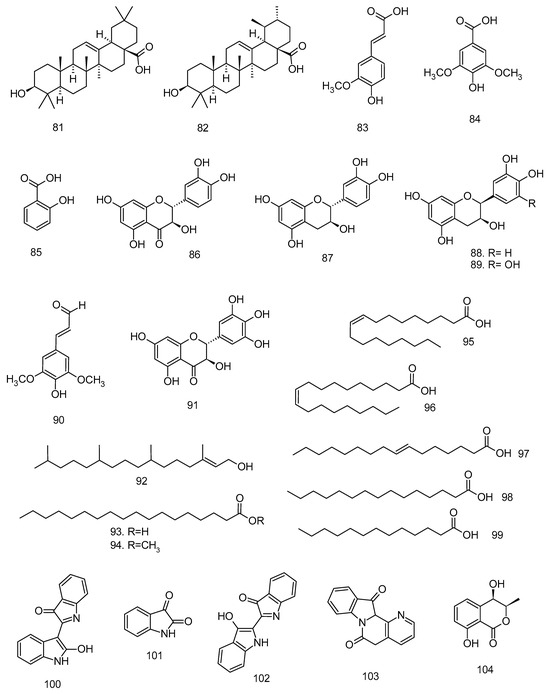

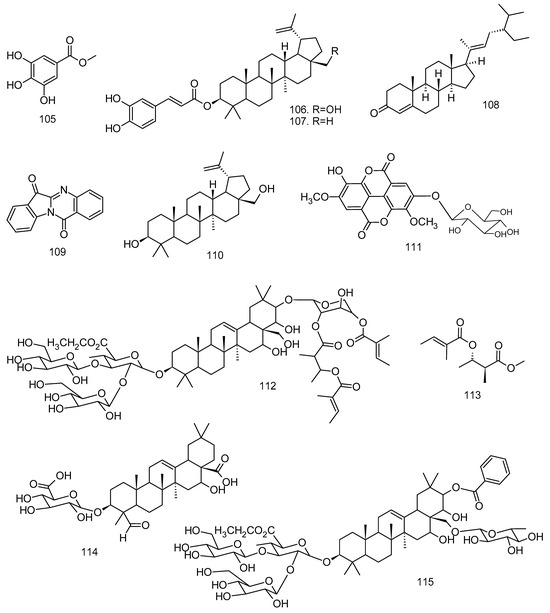

All articles were classified at the same level of evidence on anti-inflammatory and antinociceptive activity in experimental studies, involving extracts, fractions, and/or components isolated from some part of the plant, in addition to the use of nuts in natural form or flour. Only two studies used products, a gel formulation with extract and a silver nanoparticle and extract. The information compiled in this review is presented in Table 2, and the structures of the compounds reported in this table and text are represented in Figure 3.

Table 2.

Anti-inflammatory activity of species of the family Lecythidaceae in different experimental models.

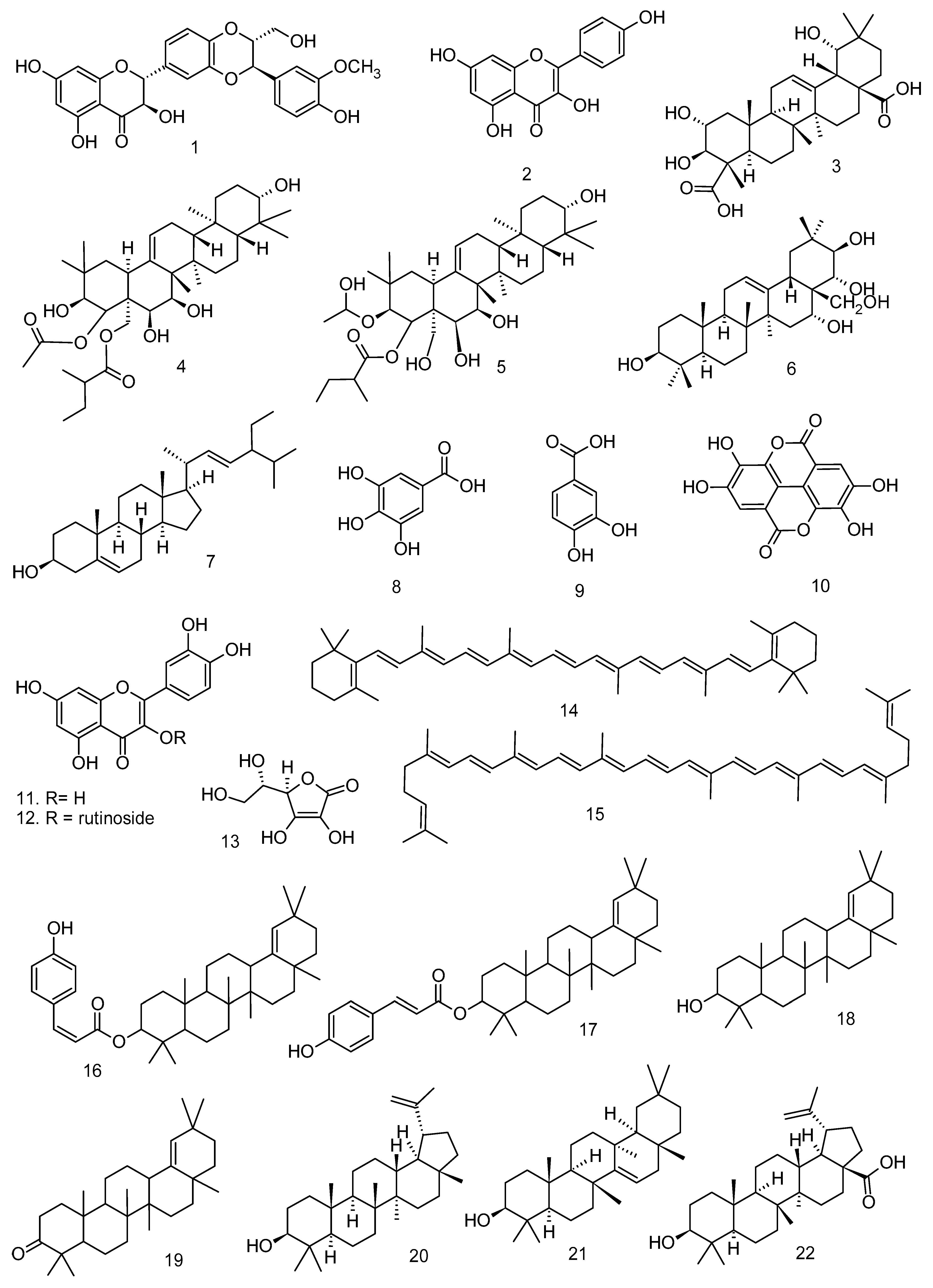

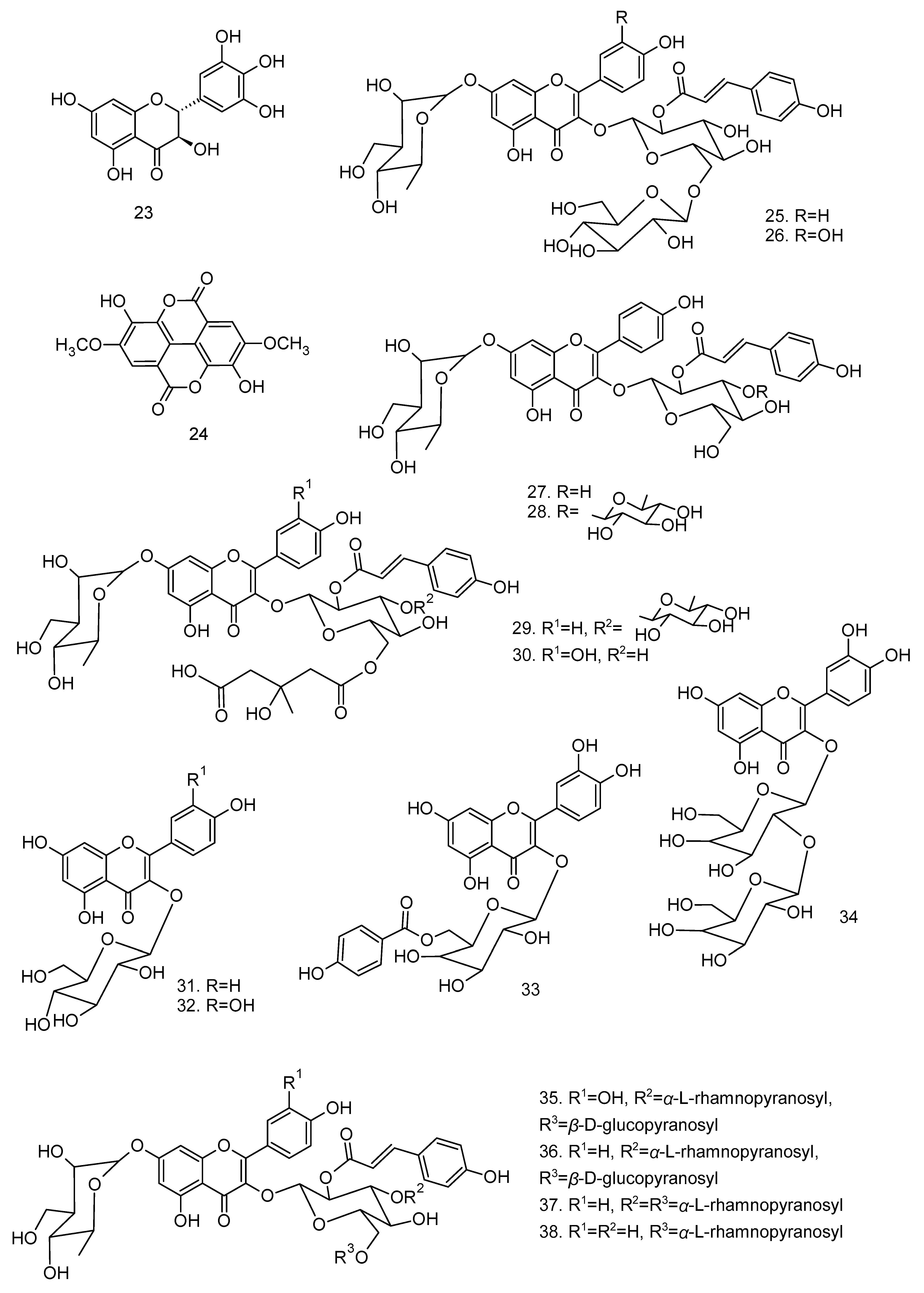

Figure 3.

Compounds isolated from Lecythidaceae species with anti-inflammatory activity.

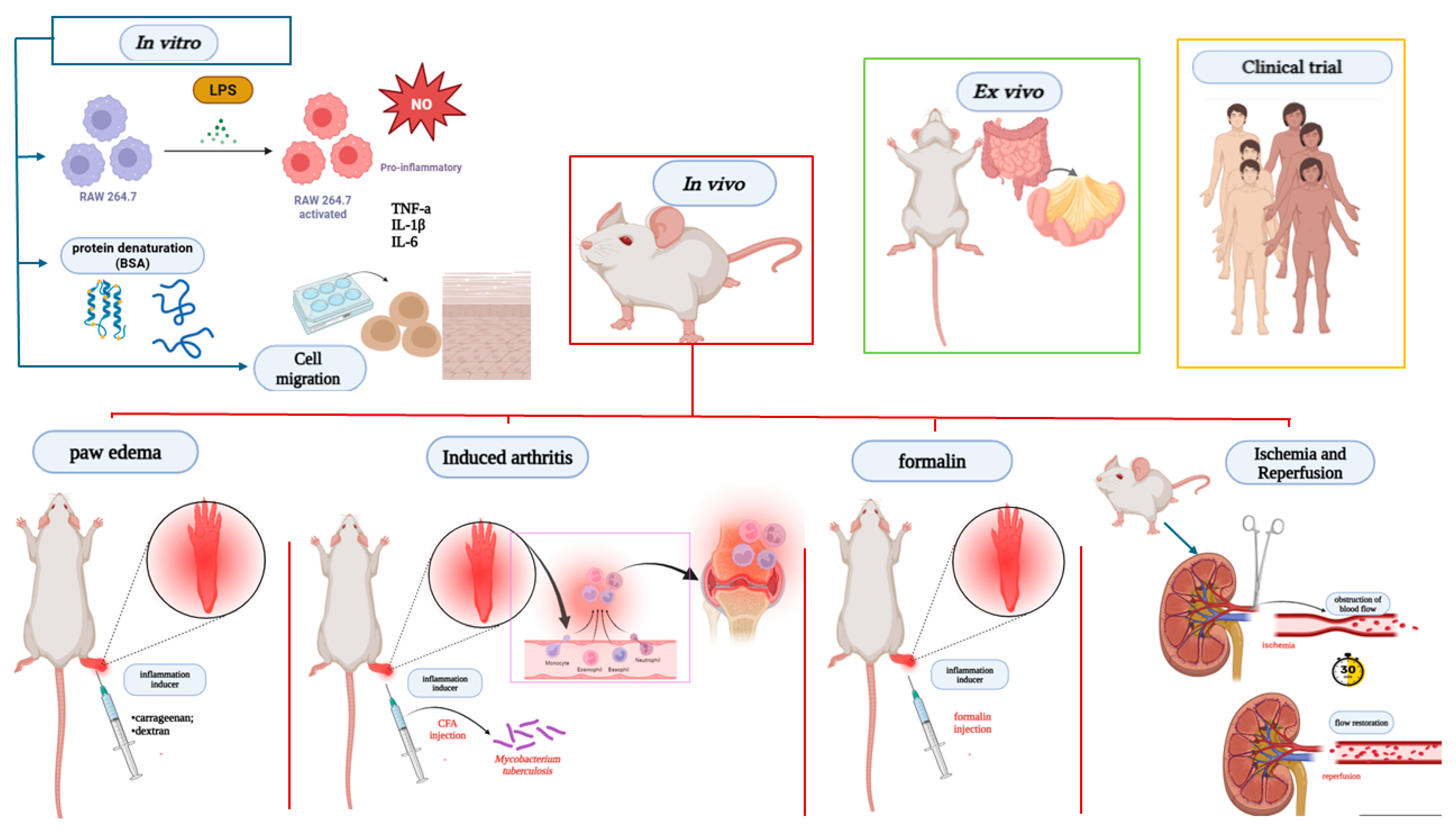

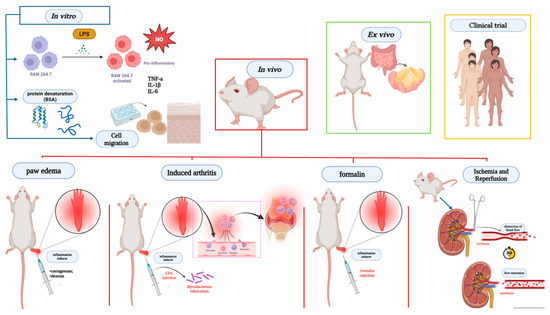

Anti-inflammatory evaluations performed with Lecythidaceae species include studies with clinical trials, in vitro, in vivo, and ex vivo, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Main anti-inflammatory and antinociceptive assays present in studies with Lecythidaceae species. Created in BioRender. Smith, J. (2025). BioRender.com/c248457. In vitro models, the anti-inflammatory potential was assessed by stimulating RAW 264.7 cells with LPS, analyzing the production of mediators such as cytokines and nitric oxide, as well as protein denaturation and cell migration. In vivo assays, the most prevalent models included carrageenan- or dextran-induced paw edema; CFA-induced arthritis using Mycobacterium tuberculosis; formalin-induced inflammation; and inflammation induced by ischemia-reperfusion of renal artery blood flow. BSA: bovine serum albumin denaturation; CFA: complete Freund’s adjuvant-induced arthritis; IL-1β: interleukin-1β; IL-6: interleukin-6; NO: nitric oxide; TNF-α: tumor necrosis factor alpha.

Of the 34 studies analyzed, only two were randomized clinical trials, both with Brazil nuts in different populations: hemodialysis patients and obese women [32,33]. In both studies, supplementation with Brazil nuts had favorable results.

Ten studies with in vitro evaluation verified the anti-inflammatory action of Lecythidaceae samples through the levels of inflammatory markers, with inhibition of nitric oxide production being the most evaluated marker [4,18,19,24,25,29,39,40]. In silico studies were not identified in the search strategy used, but these studies are also relevant for understanding drug activity.

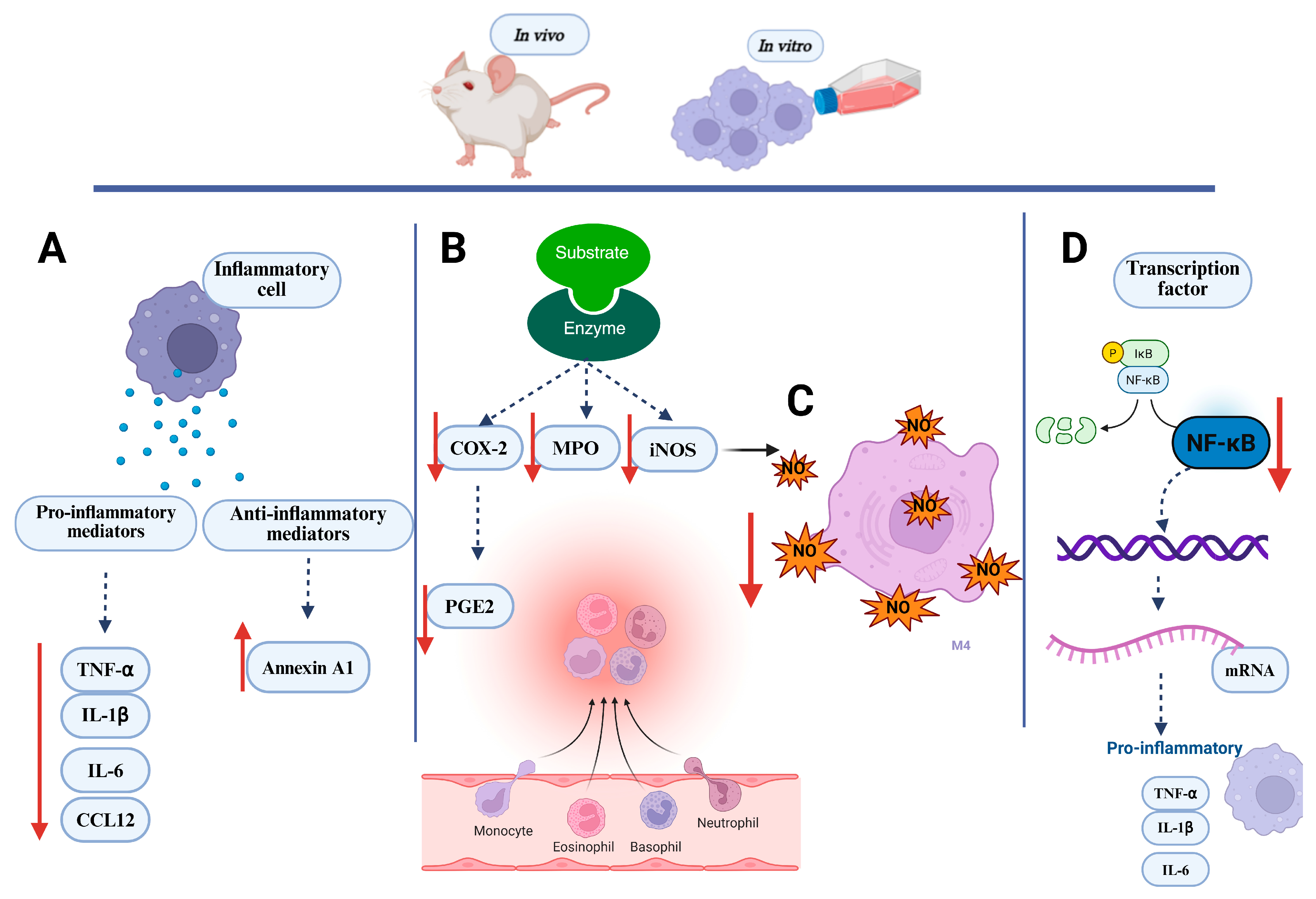

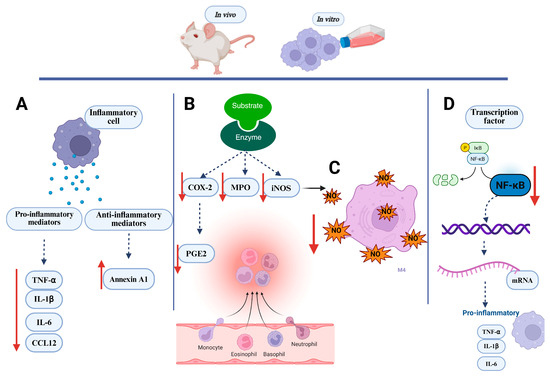

In vivo assays were employed in the majority of the compiled studies (76,4%). Eight studies evaluated antinociceptive activity through an acetic-acid-induced abdominal writhing test, a tail flick test and hot plate test, a formalin test, and capsaicin- and glutamate-induced pain tests [23,25,28,35,37,47]. Anti-inflammatory activity was assessed using acute inflammatory models such as the formalin test, paw edema test (carrageenan, dextran, histamine, and serotonin 5-HT), ear edema test, and ischemia and reperfusion and HCl/EtOH-induced acute gastritis. The chronic inflammation trials included complete Freund’s adjuvant-induced arthritis [7,27] and a cotton pellet granuloma test [2,28]. Some in vivo studies also verified the possible mechanisms of action, which included inhibition of inflammatory markers, such as NO and pro-inflammatory cytokines, as well as induction of anti-inflammatory cytokines [4,5], in addition to action in inhibiting the gene expression of enzymes and cytokines [18,19,30,31,36,43,47]. Figure 5 shows the main action mechanism tests performed with Lecythidaceae species.

Figure 5.

Key inflammatory markers evaluated in in vivo and in vitro assays. (A) Inflammatory cells treated with Lecythidaceae samples showed a reduction in pro-inflammatory mediators and an increase in anti-inflammatory mediators; (B) Lecythidaceae samples reduced the activity of inflammatory enzymes in cell; (C) Lecythidaceae samples reduced nitric oxide production in cells; (D) Lecythidaceae samples suppressed transcription factors in cells. Red arrows indicate an increase or decrease in the respective mediators. Created in BioRender. Smith, J. (2025). BioRender.com/c248457. CCL12: chemokine C-C motif ligand 12; COX-2: cyclooxygenase; IκB: nuclear factor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B cells inhibitor; IL-1β: interleukin-1β; IL-6: interleukin-6; iNOS: nitric oxide synthase; MPO: myeloperoxidase; NF-κB: nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells; NO: nitric oxide; P: phosphate; PGE2: prostaglandin E2; TNF-α: tumor necrosis factor alpha.

The accumulated evidence demonstrates that numerous Lecythidaceae species exhibit potent anti-inflammatory effects in both acute and chronic models of inflammation. However, this analysis highlights a critical need for more focused and sequential research on the most promising candidates, utilizing standardized plant parts and extracts.

Couroupita guianensis Aubl. and Petersianthus macrocarpus (P.Beauv.) Liben underwent further evaluation of their anti-inflammatory activity using the same part of the plant and extractive derivatives in in vitro and in vivo assays. Despite the high bioactive potential of the Barringtonia genus, the best candidates for further studies were the leaves and stems of Barringtonia angusta Kurz and the fruits of B. racemosa (L.) Roxb. Studies with extracts of Barringtonia acutangula (L.) Gaertn. showed promising results in terms of anti-inflammatory and antinociceptive activity, but the results are from different parts of the species and in different models, without clear and objective continuity. Brazil nuts warrant further investigation not only for their nutritional value but also to better elucidate their mechanistically underpinned bioactive properties.

3.1. In Vitro Anti-Inflammatory Activity

Most studies of anti-inflammatory evaluation of Lecythidaceae species have shown significant results (Table 2). Species of the genus Barringtonia have been investigated for their medicinal properties and have promising candidates for the development of phytopharmaceuticals with anti-inflammatory action, such as the species B. angusta, B. racemosa, B. acutangula, and B. pendula (Griff.) Kurz. The methanolic extract from the leaves and stem of the species B. angusta inhibited the transcriptional expression of inflammatory genes (iNOS, COX-2, TNF-α, and IL-1β) and the phosphorylation of inflammatory signaling proteins (Src, IκBα, p50/105, and p65) induced by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) in macrophages, as well as suppressing the transcription of the nuclear factor gene Kappa B (NF-κB) and translocation of the NF-κB protein to the nucleus, in addition to reducing the production of nitric oxide [18]. The authors found that this extract exerted anti-inflammatory action under more than one molecular signaling pathway of the cellular inflammatory response, and this information is relevant for the development of anti-inflammatory drugs of high specificity for the SrC target in NF-κB signaling.

Sequentially, this same B. angusta extract also effectively suppressed COX-2 and CCL12 gene expression in macrophages in a dose-dependent manner. As cytokines and inflammatory genes are upregulated by the activation of transcription factors AP-1 and nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB), the methanolic extract of B. angusta showed inhibitory action of inflammatory responses mediated by macrophages as it acts by blocking the activation of AP-1 signaling, through the expression level of JNK [19]. These results are promising because they were obtained with extracts. Certainly, further studies with isolated fractions or components may reveal information of those responsible for the activity or if there is synergism between the components of the extract.

Another species of this genus, B. racemosa, demonstrated inhibitory action of nitric oxide (NO) production in RAW264.7 cells [24]. The chloroform, hexane, and ethanol extracts from the leaves, at a dose of 200 µg mL−1, were able to inhibit NO production by 73.85%, 60.06%, and 45.60%, respectively. These extracts were also evaluated for their cytotoxicity in vitro, and only the chloroform extract showed no cytotoxic effect at all doses evaluated. However, the study by Behbahani et al. [24] did not present information on the chemical composition of said extract. Kong et al. [8] reports the presence of gallic acid (8), protocatechuic acid (9), ellagic acid (10), quercetin (11), rutin (12), kaempferol (2), ascorbic acid (13), β-carotene (14), and lycopene (15) in the leaves of B. racemosa. The identification of the main components present in the extract or bioactive fraction is important information to understand the biological activity, but their evaluation alone cannot always confer a greater biological activity compared to the extracts and fractions.

In the study by Vien et al. [25], glycosylated flavonoids isolated from Barringtonia acutangula leaves were evaluated in in vitro NO production reduction assays. Of the ten isolated compounds (Barringosides A-F (25–30), kaempferol 3-O-β-D-galactopyranoside (31), quercetin-3-O-β-D-galactopyranoside (32), quercetin 3-O-β-D-(6-p-hydroxybenzoyl) galactopyranoside (33), and quercetin 3-O-α-L-arabinopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-galactopyranoside (34)), only 3-O-β-d-(6-p-hydroxybenzoyl) galopactanoside quercetin showed significant NO inhibitory activity, in relation to that of the positive control [25]. The evaluation of these flavonoids in other biological pathways is necessary to better understand the anti-inflammatory behavior attributed to this species by folk medicine. The leaves of this species showed anti-arthritic activity in vivo [27]. Acylated flavonoid glycosides from B. pendula, barringosides J-O (35–40), were also evaluated in nitric oxide assays in vitro. Moderate inhibitory effects on LPS-induced NO production in RAW264.7 cells were observed only for barringosides M (38) and N (39), with IC50 values of 48.40 and 56.61 μM [29]. Thus, the low expressive result of these flavonoids against NO inhibitory activity should not be understood as the absence of anti-inflammatory activity but the need to evaluate them against other inflammatory signaling pathways.

The fruits of B. racemosa were evaluated in in vitro and in vivo assays and showed promising results. Osman et al. [22] observed moderate inhibition of albumin denaturation and xanthine oxidase enzyme activity by methanol extracts of the pericarp and endosperm of B. racemosa. The study by Shikha et al. [21] identified the lipid antiperoxidation capacity of the ethanol extract of fruit. To date, the fruit of B. racemosa is the part of the species most studied in anti-inflammatory and antinociceptive models. Further studies of the anti-inflammatory activity of B. racemosa fruit may lead to a better understanding of the mechanisms of action and pharmaceutical products containing the extract. In terms of chemical composition, one of the compounds responsible for the anti-inflammatory activity is bartogenic acid (3), isolated from the fruits of this species, which has anti-arthritic properties [7].

The species C. guianensis, which is used as a home remedy to treat pain and inflammation, had its leaf ethanolic extract used in the synthesis of nanoparticles (NPs) of lanthanum oxide (La2O3). Two types of NPs of La2O3 were obtained and evaluated in a bovine serum albumin (BSA) denaturation inhibition assay. Both NPs of lanthanum oxide and C. guianensis extract showed inhibition of BSA denaturation in a dose-dependent manner. The denaturation of proteins in the biological environment leads to the loss of their function and has been characterized as an inflammatory process. NPs of lanthanum oxide and C. guianensis extract need to be better evaluated for anti-inflammatory action, but the proposal stands out for the innovation and antibacterial, antioxidant, anti-diabetes, and anti-cancer activity presented by in vitro studies [39]. C. guianensis bark stem decoction also showed property anti-inflammatory in vitro in wound healing assays by upregulating pro-migratory pathways in human HaCaT keratinocytes and suppressing cutaneous inflammatory damage. The activity was attributed to the novel compound 4-(2′′-O-sulfato-β-D-glucuronopyranosyl)-ellagic acid (80) isolated from the bark extract [40]. Phytochemical studies have revealed new compounds in some species of Lecythidaceae [25,29], but the number of existing studies is insufficient to understand the chemistry of the family, which has species with no studies in the literature.

3.2. Anti-Inflammatory and Antinociceptive Activity In Vivo

In vivo evaluations were found for the ten species compiled in this review. The species studied are from the genera Barringtonia, Bertholletia, Careya, Cariniana, Couroupita, Lecythis, and Petersianthus, a representation of less than one-third of the total of twenty-four genera belonging to the family Lecythidaceae [48]. Models of nociception and acute and chronic inflammation in vivo were identified in 26 articles (Table 2).

Three species of the genus Barringtonia have shown anti-inflammatory and antinociceptive activities in vivo: B. angusta, B. racemosa, and B. acutangula. B. angusta promoted the inhibition of NO production in peritoneal macrophages, as well as in a peritonitis model in rats, with ethanolic extract from leaves and stems (dose 100 mg kg−1), with a reduction in proinflammatory mediators (COX-2 and CCL12 mRNA) and, consequently, inflammatory lesions. In addition, the authors identified in this study that B. angusta extract is capable of blocking the AP-1 signaling pathway, at the JNK expression level, using TAK-1 to inhibit the inflammatory response in macrophages [19]. The same extract (50 mg kg−1 dose) was also able to reduce gastric lesions in the stomachs of treated mice by more than 80% and was not cytotoxic [18]. These studies did not evaluate the chemical composition of the extract, and so far, no information has been published on the components present in this species.

Aqueous extract of B. racemosa stem bark was also bioactive, but at high concentrations. In antinociceptive evaluation, it showed action at the third and fourth hour in a dose-dependent manner with ED50 values of 631.4 and 758.0 mg kg−1, respectively, in a hot plate test. In the formalin test, all doses showed weak activity in the initial and final phases. In the evaluation of the mechanism of action, the authors report that the antinociceptive action of the extract was blocked by naloxone, indicating that antinociception was mediated by an opioid mechanism [23]. The stem bark has presented triterpenes such as olean-18-en-3-β-O-Z-coumaroyl ester (16), olean-18-en-3-β-O-E-coumaroyl ester (17), germanicol (18), germanicone (19), lupeol (20), taraxerol (21), betulinic acid (22) [49], and bartogenic acid (3), as well as the steroid stigmasterol (7), the flavonoid dihydromyticetin (23), and the phenolics 3,3’-dimethoxy ellagic acid (24) and gallic acid (8) [50]. However, the presence of triterpenes and steroids in the aqueous extract is not expected due to their low solubility in water. Phenolic compounds such as gallic and ellagic acid present solubility in water and show inhibitory action of LPS-induced NO, PGE-2, and IL-6 production in vitro [51].

The ethanol extract of B. racemosa fruit exhibited anti-inflammatory and antinociceptive action. A dose of 250 mg kg−1 reduced inflammation by 70% in a carrageenan-induced paw edema model and by 75% in a formalin-induced paw edema model. A 98.1% reduction in nociception was obtained with a dose of 500 mg kg−1 [21]. A gel formulation with 7 ppm of fruit extract reduced signs of inflammation in healing assays, such as lesion area, presence of exudate, and redness [20].

The AcOEt fraction of B. racemosa fruits exhibited anti-inflammatory action in an acute and chronic inflammation model. The fraction exhibited acute dose-dependent anti-inflammatory activity at 5, 10, and 20 mg kg−1 in the carrageenan-, histamine-, and serotonin-induced edema tests, respectively. In chronic inflammation models, the fraction exerted anti-inflammatory activity in mice with induced granuloma, with a dose-dependent effect, while in the oxazolone-induced delayed-type hypersensitivity (DTH) model, the fraction had an inhibitory effect of DTH intensity similar to that of dexamethasone [2].

Notable anti-inflammatory results were also found for bartogenic acid (3), a triterpene isomer of barringtonic acid, isolated from AcOEt fraction of B. racemosa fruits. The compound exhibited protective action against primary and secondary arthritic lesions in rats at doses of 2, 5, and 10 mg kg−1.day−1 in rats. Serum markers of inflammation and arthritis, such as C-reactive protein and rheumatoid factor, were also reduced in arthritic rats treated with bartogenic acid [7]. Four triterpenes, racemosol (4), isoracemosol (5), barringtogenol (6), and bartogenic acid (3), and the steroid estimasterol (7) were reported in B. racemosa fruits [52], being a class of taxonomic markers of the genus. Bartogenic acid has also been isolated from the species B. asiatica Kurz [53], B. acutangula (L.) Gaertn. [54] and B. speciosa Forst [55].

Another species of Barringtonia with an antinociceptive evaluation study is B. acutangula. The methanolic extracts from leaves and seeds of this species exhibited antinociceptive action of 68.6% and 83.3%, respectively, at a dose of 400 mg kg−1, in addition to increasing the latency time in a dose-dependent manner, with action similar to that of the reference drug. However, the antinociceptive action in the tail immersion test was weak for both extracts. They showed no signs of toxicity at a dose of 2000 mg kg−1 [26]. B. acutangula leaves have glycosylated flavonols with a kaempferol and quercetin skeleton, six of which are unpublished, Barrigosides A–F (25–30) [25].

In an anti-inflammatory evaluation, leaves of B. acutangula showed activities. Chloroform extract from leaves was investigated in an in vivo model of arthritis induced by “Complete Freund’s Adjuvant”, using the prophylactic and therapeutic model [27]. In the prophylactic model, the best result was 400 mg kg−1 both for the 7th day, where inflammation was maintained at 60%, and on the 14th day, with inflammation at 43%. In the therapeutic model, the antiarthritic action was verified only on the 21st day, with dose-dependent action (400 mg kg−1 maintained inflammation at 56%) [27].

B. acutangula root was also tested for its antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory activity in vivo [28]. The maximum efficacy of ethanolic extract analgesia (500 mg kg−1) was 91.33% and 13.8% for the hot plate and acetic acid contortion test, respectively. For the acute model, the inhibition of inflammation was 26.82% for the highest dose (reference drug 27.22%). For the chronic model, it was 24.56% for the highest dose (reference drug 29.26%). In both tests, inhibitions were dose-dependent [28]. Extracts from the roots of this species are promising in models of pain and chronic inflammation [27,28]; however, the use of this part of the plant adversely affects the species in its natural habitat, in view of which the use of in vitro root cultivation is proposed for medicinal purposes.

Bertholletia excelsa Bonpl. is perhaps one of the best-known species of this family for being a producer of the nut that is popularly named the Brazil nut, which has been studied for its nutritional properties. In a study conducted by Anselmo et al. [31], the pretreatment action of 75 and 150 mg of Brazil nuts in rats with renal ischemia and reperfusion was evaluated. Prior treatment with nuts attenuated the effects of ischemia and reperfusion in animals. Both dosages reduced nitrotyrosine and iNOS expression, transmigration of macrophages into the kidneys, as well as TBARS levels. There were no effects on TEAC levels in the groups of animals evaluated.

In the continuation of this study, Cury et al. [30] reports that pretreatment with 75 mg of B. excelsa nuts reduced the renal expression of COX-2, TGF-β, vimentin, and caspase-3 after IR, with a protective effect against cell death by apoptosis.

Collectively, these two studies on nuts demonstrated efficacy against several mediators involved in kidney injury and have, in addition, an anti-inflammatory mechanism. Such activities may be related to their chemical composition, which presents phenolic compounds as main components. The main bioactive phenolics identified are hydroxy-benzoic acids and derivatives such as gallic acid (8), protocatechuic acid (9), protocatechuic aldehyde (42), vanillic acid (43), and ellagic acid (10) [56]. These components are known for their antioxidant and also anti-inflammatory properties [51,57,58]. The bioactive properties of B. excelsa nuts may lead to the development of phytofunctional foods.

Only two studies evaluated the species Careya arborea Roxb. regarding its anti-inflammatory action. Begum et al. [4] reports the effects of the methanolic extract from the stem bark of this species on the reduction in carrageenan-induced paw edema, at both doses tested, namely, 100 mg kg−1 (48.87%) and 200 mg kg−1 (65.53%), with a significant result when compared to the reference drug. Both concentrations of the extract also reduced levels of the pro-inflammatory mediators at the site of inflammation, malondialdehyde (MDA), C-reactive protein (CRP), nitric oxide (NO), myeloperoxidase (MPO), tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), and interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β). These results reveal a multi-target action of the extract on different inflammatory mediators, being an anti-inflammatory agent that needs to be further investigated as to its bioactive potential.

In a subsequent study, Begum et al. [5] presents the anti-inflammatory activity of betulinic (22) and coumaroyl-lupendioic acids (48), isolated from the methanolic extract from the stem bark of C. arborea, in carrageenan-induced paw edema tests and effects thereof on the levels of inflammatory mediators. Both betulinic acid (10 mg kg−1 = 40.83% and 20 mg kg−1 = 54.35%) and coumaroyl-lupendioic acid (10 mg kg−1 = 49.19% and 20 mg kg−1 = 68.89%) reduced paw volume in a dose-dependent manner after 5 h of carrageenan injection. Coumaroyl-lupendoic acid showed a more expressive effect on the suppression of carrageenan-induced paw edema than betulinic acid at the same doses, in addition to exhibiting activity similar to that of the reference drugs, indomethacin (10 mg kg−1; 70.63%) and celecoxib (20 mg kg−1; 61.09%). It also showed better inhibitory action of NO, MPO, PGE2, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and COX-2 levels, compared to the control group.

The peels of Cariniana domestica (Mart.) Miers fruit revealed antiedematogenic action in an inflammatory model of croton-oil-induced contact dermatitis in vivo; 70% hydroethanolic extract and fractions (1 mg ear−1) reduced edema with maximum inhibition values of 97%, 86% (CH2Cl2), 81% (BuOH), and 95% (AcOEt), respectively. Both the extract (3%; 15 mg ear−1) and the AcOEt fraction (1%; 15 mg ear−1) were used in gel-based formulations and showed satisfactory inhibition of 85% and 82%, respectively. The anti-inflammatory evaluation also extended to the isolated components β-sitosterol (7.5 µg ear−1; 50), lupeol (10 µg ear−1; 20), and stigmasterol (5.7 µg ear−1; 7) that showed antiedematogenic action, 46%, 51%, and 62%, respectively [34]. This study reveals that the formulation did not affect the antiedematogenic action of the extract and that the components β-sitosterol (50), stigmasterol (7), and lupeol (20) are responsible for the activity, with possible synergism in the extract, a condition not evaluated by [34].

Another species of the genus Cariniana that showed anti-inflammatory action was C. rubra Miers in in vivo anti-inflammatory models (carrageenan- and dextran-induced paw edema in rats; carrageenan-induced pleurisy in rats; increased acetic-acid-induced vascular permeability in mice), and antinociceptive (formalin test, hot plate, and acetic-acid-induced licking in mice) and antipyretic agents (yeast-induced pyrexia in rats). The methanolic extract from the stem bark of this species showed a reduction in edemas only at the highest dose (2000 mg kg−1); this dosage also promoted the inhibition of pleuritic exudate and leukocyte migration by 80%, as well as being able to reduce the rectal temperature of the animals in the second and third hour after administration. In the antinociceptive assays, the extract showed moderate action, except for the hot plate test, where the extract showed no analgesic effect [35].

Silva et al. [36] also evaluated the anti-inflammatory activity of the methanolic extract from the stem bark of C. rubra through carrageenan-induced subcutaneous air cavity assays and determination of inflammatory biomarkers (TNF-α, IL-1β, and Annexin-A1). Methanolic extract showed significant anti-inflammatory action by at least increasing annexin-A1 expression (26.9%; AnxA1) in skin tissue, particularly in neutrophils. A reduction in the concentration of TNF-α in the air cavity wash (37.2%) was observed at a dose of 750 mg kg−1, an action similar to 43.2% of the reference drug. The extract also promoted a reduction in polymorphonuclear migration (57.7% and 57.8%) and leukocytes (74.5% and 61.8%) in the air pocket cavity and skin tissue, respectively. The extract was cytotoxic only after 72 h of cell exposure (CHO-k1; IC50 = 19.90 μg kg−1). From the extract of stem bark of C. rubra, three saponins derived from arjunolic acid (54), 3-O-β-glucopyranosyl arjunolic acid (53), 28-β-glucopyranosyl-23-O-acetyl arjunolic acid (55), and 28-O-[α-L-rhamnopyranosyl-(1→ 2)-β-glucopyranosyl]-23-O-acetyl arjunolic acid (57) were isolated [59]. These two studies showed that the stem barks of the species C. rubra are not as active as the stem barks of Careya arborea; however, the models used in the evaluations may be limited to describe the biological action associated with the ethnopharmacological use of this species.

The leaves of the species Couroupita guianensis Aubl. revealed potent antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory action in vivo. For the acetic acid intraperitoneal injection-induced pain model, all fractions showed activity. The hexane fraction had a higher action than morphine, and the butanolic fraction had an equivalent action, both at a dose of 30 mg kg−1. For the tail flick test, the ethyl acetate fraction showed the best result, at a dose of 30 mg kg−1. In the hot plate test, ethyl acetate and butanolic fractions show greater action at a dose of 100 mg kg−1 for a time of 120–150 min. In addition to the analgesic action, the fractions did not exhibit toxicity at the dose of 500 mg kg−1 for 5 days [37].

Pinheiro et al. [38] used in vivo assays to evaluate extract activity and fractions of C. guianensis leaves against inflammatory pain (formalin test) and acute inflammation (carrageenan-induced peritonitis). Oral administration of the ethanolic extract or fractions (at a dose of 10, 30, or 100 mg kg−1) prior to formalin stimulation significantly decreased licking behavior in mice in the neurogenic phase. Ethanolic extract inhibited licking time by 23.5%, 53.8%, and 51.5%, while the hexane fraction decreased by 26%, 40.8%, and 42%, and ethyl acetate decreased by 22.3%, 60.9%, and 66%, at doses of 10, 30, and 100 mg kg−1, respectively. The result was satisfactory in comparison with the positive control groups, where acetylsalicylic acid and morphine reduced the lick time of the first phase by 40.6% and 64.9%, respectively [38].

The chemical composition of the species C. guianensis includes kaempferol (2), quercetin (11), rutin (12), caffeic acid (76), sinapic acid (77), apigenin (78), and luteolin (79) in leaves; alkaloids, indirubin (100), isatin (101), indigo (102), and couroupitine (103) present in fruits [60,61] and cis-4-hydroxymellein (104), methyl gallate (105), betulin-3-β-caffeate (106), lupeol 3-β-caffeate (107), stigmasta-4,22-dien-3-one (108), betulin (110), β-amyrin (52), lupeol (20), stigmasterol (7), and the alkaloid tryptanthrin (109) in the stem bark [62].

The species Lecythis pisonis Cambess., known in Brazil as sapucaia, had its leaves investigated in anti-inflammatory and antinociceptive assays. Leaf ethanol extract (LPEE), fractions in hexane (LPHF), ethyl ether (LPEF), ethyl acetate (LPEAF), and a mixture of triterpenes had their antipruritic, antiedematogenic (carrageenan-induced paw edema model) and motor activities evaluated in vivo and ex vivo [41]. Mice treated with 100 and 200 mg kg−1 LPEE, LPHF, or LPEF showed inhibition of compound 48/80-induced pruritus by 45.82%, 63.24%, 43.34%, 58.28%, 31.96%, and 77.31%, respectively, compared to control groups. LPEF (200 mg kg−1, p.o.) showed the best reducing action of carrageenan-induced edema in all observations (1–6 h), with an inhibition rate of 41.55% to 74.86%. The main metabolites of the ethanolic extract and the active ether fraction were isolated and identified as a mixture of the pentacyclic triterpenes ursolic acid (82) and oleanolic acid (81). This mixture of triterpenes was able to reduce induced itching in animals to 35.84% (25 mg kg−1 dose) and 59.26% (50 mg kg−1 dose).

Subsequently, the ethanolic extract, ethyl ether fraction, and a mixture of triterpenes (ursolic and oleanolic acids) from Lecythis pisonis leaves reduced the number of contortions produced by acetic acid and the lick stimulus induced by formalin and capsaicin in the animals [42]. Glutamate-induced nociception was reduced by ethanol extract and ethyl ether fraction relative to the vehicle, but it was the triterpene mixture that showed the best antinociceptive action of the three samples tested. The authors suggest that the antinociceptive mechanism may involve inhibition of NO production and/or interaction with the glutamatergic system, since reversal of the antinociceptive effect of the fraction was observed by pretreatment with L-arginine [42].

The anti-inflammatory and antioxidant evaluation with L. pisonis nuts showed that the intake of this nut reduced the oxidative stress and inflammatory response produced by a high-fat diet [43]. The intake of sapucaia nuts led to decreased lipid peroxidation in animals fed with a standard diet and a high-fat diet. Decreased MDA concentration and increased superoxide dismutase (sod) enzyme were observed in the brain tissue of the animals. The expression of pro-inflammatory mediators TNF-α and NF-kB (p65) were reduced in both groups treated with sapucaia nuts, while the expression of ZnSOD and HSP-72 genes was increased [43]. The nuts of L. pisonis have presented phenolic components such as vanillic acid, ferulic acid, ellagic acid, catechin, epicatechin, and myricetin [63]. The phenolic profile of Lecythidaceae nuts has been more varied and with higher percentages than other nuts consumed for their flavor and nutritional value, being another favorable point for medicinal and nutritional use [63].

The methanol extract from the bark of N. vogelii showed promising results in in vivo anti-inflammatory and antinociceptive assays. The anti-inflammatory action was high in both tests evaluated (83–91% inhibition of inflammation) for doses of 400 mg kg−1. The antinociceptive activity was 55–62% compared to the reference drug in both tests performed. The authors also identified that the extract acts through inhibition of dopaminergic pathways. No studies on the isolation and identification of compounds present in this species were found. Given the relevant anti-inflammatory results of N. vogelii Hook. & Planch., it is necessary to investigate the compounds present in the bioactive extract.

The stem bark of P. macrocarpus (P. Beauv.) Liben was evaluated for its antinociceptive action by research groups from Cameroon [45] and Nigeria [46]. The methanolic extract of stem barks from Nigeria showed antinociceptive action of 70.53% at the highest dose (1000 mg kg−1) in trials of intraperitoneal administration of acetic acid in mice, while the methanolic extract from Cameroon showed inhibitory action above 70% for lower doses (200–400 mg kg−1). The aqueous and ethyl acetate fractions (200 mg kg−1) obtained from the species collected in Nigeria showed a more satisfactory action, with inhibition above 70%, than the aqueous extract from Cameroon (54% to 400 mg kg−1). The aqueous and ethyl acetate fractions were also able to increase the analgesia time in the hot plate test [46]; similar action was observed for aqueous and methanolic extracts from Cameroon [45].

The methanolic and aqueous extracts from the stem bark showed antinociceptive action in the acetic-acid-induced contortion assays, capsaicin-induced pain, pain induced by intraplantar injection of glutamate, and intraplantar injection of formalin. An antinociceptive action can be understood by the response exerted by both extracts in the second phase of the formalin assay, at a dose of 400 mg kg−1, where the aqueous extracts were inhibited by 82% and the methanolic extracts by 91% compared to morphine at 81% [45]. In the second phase, inflammatory pain results from synaptic signaling with the release of local inflammatory mediators such as prostaglandins and histamine [64]. Saponins and other compounds were isolated from the stem bark from P. macrocarpus petersaponin I (112), petersaponin II (115), prosapogenin (114), barringtogenol C (6), 3,3’-dimethoxy-4-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl-ellagic acid (111), methyl 3-O-tigloyl-nilate (113), and 3,3’-dimethoxy-ellagic acid (24) [65]. Saponins exhibit numerous biological activities, among which the anti-inflammatory action stands out [66]. Recently, saponins of the species Panax ginseng showed inhibitory action of NLRP1 of the inflammasome activation pathway [67].

In addition to these results, aqueous and methanolic stem bark extracts from P. macrocarpus also showed an antinociceptive effect on neuropathic pain in a chronic constriction injury model. The authors associate the mechanism of antinociceptive activity with inhibition of the nitric oxide pathway as well as a reduction in NF-κB and TNF-α gene expression in the brain [47]. Thus, P. macrocarpus stands out in this survey as a candidate for future studies based on stem bark extract.

3.3. Randomized Trials

Randomized studies on anti-inflammatory action were found only for Bertholletia excelsa Bonpl. nuts. Stockler-Pinto et al. [32] conducted a randomized study to verify the effects of daily supplementation of Brazil nuts on lipid profile, oxidative stress, and inflammation in hemodialysis patients. After 3 months of supplementation with B. excelsa nuts, patients had reduced levels of 8-OhdG, 8-isoprostane, IL-6, and TNF-α, while GPx activity and plasma selenium levels were increased (158.1 μg L−1). HDL-c levels in the supplemented patients increased values, while LDL-c levels decreased. There was no significant change for triglyceride levels in patients [32]. Considering the phenolic profile already described for Brazil nuts, its anti-inflammatory effects are attributed to the hydroxybenzoic acids present in nuts [51,57,58].

In a randomized study evaluating the effects of consumption of Brazil nuts with a high concentration of selenium on inflammatory biomarkers in obese women, the consumption of Brazil nuts did not promote significant changes in plasma concentrations of inflammatory biomarkers. The consumption of Brazil nuts promoted an increase in Se-protein and decreased expression of the GPx1 gene in the group supplemented with B. excelsa nuts. Although the study used a Brazil nut with a selenium concentration above the concentration commonly found for this nut, the results found indicate a compensatory anti-inflammatory action due to the increased expression of genes involved in the pro-inflammatory pathway [33].

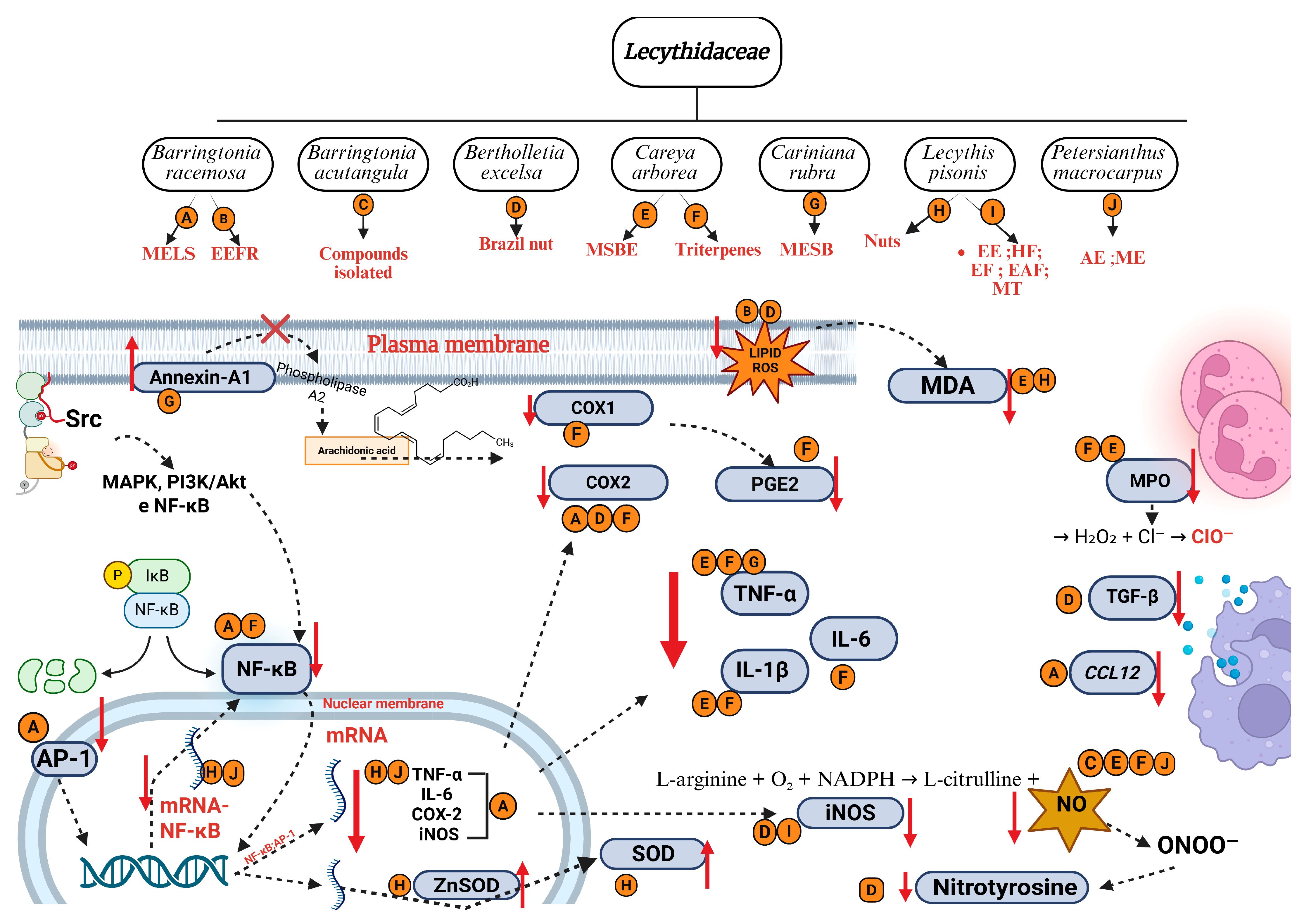

3.4. Action Mechanisms and Inflammatory Pathways

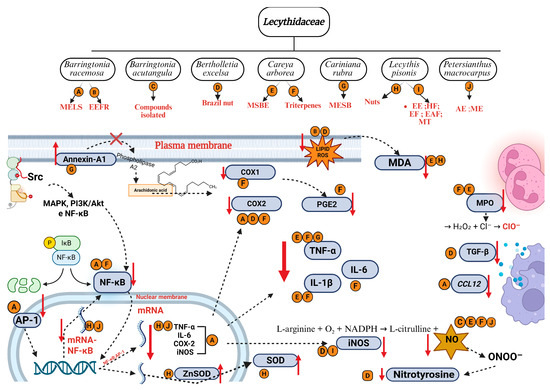

The anti-inflammatory mechanisms investigated in the studies we compiled mainly include inhibition of inflammatory markers (COX-2, IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6, MDA, CRP, NO, MPO, PGE2, and Annexin-A1) and mRNA expression genes (iNOS, COX-2, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10, TNF-α, TGF-β, GPx1, NF-κB, TLR2, TLR4, vimentin, caspase-3, ZnSOD, HSP-72, GAPDH, CXCL3, CXCL9, and CCL12). About 40% of the studies presented some type of investigation of the mechanism of action. Figure 6 presents a diagram with the mechanisms of action of the species investigated.

Figure 6.

Main mechanisms of anti-inflammatory activity of species from Lecythidaceae. Created in BioRender. Smith, J. (2025). BioRender.com/c248457. Red arrows indicate an increase or decrease in the respective mediators. AP-1: activator protein 1; D: Brazil nut; CCL12: chemokine C-C motif ligand 12; Cl−: chloride ion; COX-1: cyclooxygenase 1; COX-2: cyclooxygenase 2; H2O2: oxygen peroxide; IκB: nuclear factor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B cells inhibitor; IL-1β: interleukin-1β; IL-6: interleukin-6; iNOS: nitric oxide synthase; LPEAF: ethyl acetate fraction from Lecythis pisonis; LPEE: ethanol extract from Lecythis pisonis leaves; LPEF: ethyl ether fraction from Lecythis pisonis; LPHF: hexane fraction from Lecythis Pisonis; MAPK: mitogen-activated protein kinases; MDA: malondialdehyde; MPO: myeloperoxidase; mRNA: messenger ribonucleic acid; MT: mixture of triterpenes; NF-κB: nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells; NADPH: nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate reduced; NO: nitric oxide; ONOO−: nitrate ion; O2: oxygen molecule; ClO−: hypochlorite ion; P: phosphate; PGE2: prostaglandin E2; PI3K/Akt: phosphoinositide 3-kinase; SOD: superoxide dismutase; Src: protein-tyrosine kinase; TGF-β: transforming growth factor beta; TNF-α: tumor necrosis factor alpha; Zn: zinc.

The evaluation of nitric oxide production inhibition has been used as an accessible in vitro anti-inflammatory activity method for screening extracts, fractions, and compounds [18,19,24,25,29,47]. NO production is stimulated by various agents such as COX-2, IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, NFκB, lipopolysaccharide, and interferon-γ (IFN-γ), which can induce iNOS activity during inflammation [68]. This fact has been observed in studies with Lecythidaceae species.

NO production was inhibited by the methanolic stem bark extract of P. macrocarpus, which also inhibited the expression of TNF-α, IL-1β, and NF-κB genes [47]. Methanolic stem bark extract from C. arborea also inhibited NO production and other inflammatory markers (MDA, CRP, MPO, TNF-α, and IL-1β) [4]. Methanolic extract from leaves and stems of B. angusta also showed similar results, with inhibition of NO production in vivo and expression of iNOS, COX-2, IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and CCL12 genes [18,19]. The compound Barringoside N (IC50 = 6.61 μM), isolated from B. pendula, was more potent in inhibiting NO production than dexamethasone (IC50 = 14.20 μM), used as a reference drug [27].

Thus, the attenuation of NO production by Lecythidaceae extracts or compounds may not have iNOS as its sole biological target, but also pro-inflammatory biomarkers, in addition to modulation of anti-inflammatory cytokines. For example, annexin-A expression was increased by treatment with methanolic stem bark extract from Cariniana rubra in an in vivo study [36]. In addition, extracts and fractions, being a mixture of compounds, may exhibit action on several pro-inflammatory targets, as observed in studies with Careya arborea and its constituents. Compounds 22 and 48 exerted strong inhibition on different mediators, 22 reduced the expression of NF-κB, and 48 reduced serum TNF-α levels [4,5]. Compound 22 corresponds to betulinic acid, a pentacyclic triterpene isolated from the stem bark of Barringtonia racemosa and Careya arborea. Betulinic acid has been shown to modulate several key inflammatory mediators, including COX-2, ICAM-1, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-12, MCP-1, PGE2, and TNF, thereby exhibiting significant anti-inflammatory potential in experimental models of sepsis, lung injury, and paw edema. These effects are predominantly associated with the regulation of the NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways [69]. However, the other triterpenes isolated from B. racemosa (44–49) warrant further pharmacological investigation, as they represent newly reported constituents in the literature.

The species Barringtonia angusta, Couroupita guianensis, Lecythis pisonis, and Petersianthus macrocarpus exhibited inhibitory action on the expression of proinflammatory cytokine genes (iNOS, COX-2, IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6 mRNA) involved in the activation of the NF-κB and MAPK pathways. A better understanding of the anti-inflammatory mechanism of action of Lecythidaceae species comes from studies with methanolic extract from leaves and stems of B. angusta [18,19]. According to the authors, the anti-inflammatory effect of the extract targets the kinase activity of the Src protein, as in vitro treatment drastically reduced the levels of phosphorylated Src, which are involved in the activation of NF-κB [18]. In addition, this same extract from leaves and stems of B. angusta strongly suppressed JNK phosphorylation in a time-dependent manner. The results of this study confirmed that the extract blocks the AP-1 pathway through the expression level of JNK [19]. Thus, B. angusta extract targets JNK/AP-1 activation and promotes its anti-inflammatory effect in vitro and in vivo [19]. These results are relevant because they present new possibilities for developing therapeutic agents to treat acute and chronic inflammation. There are no nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) on the market that act on other targets of the inflammatory cascade besides cyclooxygenase enzymes.

The species Couroupita guianensis and Lecythis pisonis exhibited quercetin, rutin, and kaempferol among the constituents identified in the bioactive samples. The anti-inflammatory activity of kaempferol has been attributed to its ability to reduce the levels of pro-inflammatory mediators, including IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α, TLR4, MAPK1, and phosphorylated NF-κB p65, as well as to suppress the gene expression of several of these mediators (IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, COX-2, MCP-1, and iNOS mRNA). Additionally, kaempferol is capable of enhancing the expression of anti-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-10 [70]. Rutin, a glycosylated flavonol derived from quercetin, exhibits comparable bioactivity due to its potential bioconversion to quercetin within the gastrointestinal tract [71]. Its anti-inflammatory properties are associated with the suppression of inflammatory markers, including IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, IFN-γ, iNOS, and COX-2, as well as the inhibition of myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity in vivo [72,73].

Quercetin is among the most extensively studied flavonoids regarding anti-inflammatory activity, demonstrating effects even at low doses. In vivo assays have shown that quercetin administered at 10 mg·kg−1 decreases the levels of PGE2, TNF-α, chemokine [C-C motif] ligand 5 (CCL5), CXCL2, and COX-2 mRNA [74]. The downregulation of TNF-α, IL-6, COX-2, and iNOS expression has also been reported at concentrations as low as 5 µM [75]. According to Habtemariam and Belai [71], the anti-inflammatory activity of quercetin and rutin appears to be mediated through interference with intracellular signal transduction pathways, particularly those involving AP-1, NF-κB, and MAPK systems. This evidence is relevant because the presence of these flavonoids in extracts and fractions, even at low concentrations, may contribute to the overall anti-inflammatory potential of the samples. Quercetin has been identified in the leaves of Barringtonia racemosa [22,24], Careya arborea [4], Couroupita guianensis [37], and Lecythis pisonis [43].

Other phenolic compounds of comparable importance, present in L. pisonis and P. macrocarpus, among other species, include gallic and ellagic acids. Gallic acid has been shown to reduce the expression and/or activity of several inflammatory mediators, including IL-1β, IL-6, IL-17, IL-21, IL-23, TNF-α, IFN-γ, iNOS, and COX-2 [76]. Its anti-inflammatory activity has also been associated with the inhibition of NF-κB expression and the downregulation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3), a key component of the JAK-STAT signaling pathway [77].

Ellagic acid, a dimeric derivative of gallic acid, has demonstrated anti-inflammatory activity through multiple mechanisms. Masamune et al. [78] reported that ellagic acid prevents the activation of AP-1 and MAPK, by inhibiting IL-1β, TNF-α, extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK1/2), JNK, and p38, but not NF-κB. However, other studies reveal the inhibition of the NF-κB pathway by the reduction of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and COX-2 [79,80]. Ríos et al. [81] report that the inflammatory targets of ellagic acid may differ depending on the cell type. A similar effect occurs with ursolic acid, a triterpene identified in L. pisonis. Luan et al. [82] discuss the anti-inflammatory activity of ursolic acid and report that this triterpene can act on inflammatory pathways in different ways depending on the cell/tissue type. Oleanolic acid is another triterpene from L. pisonis leaves. This compound exerts its anti-inflammatory activity by inhibiting 5-lipoxygenase and secretory phospholipase A2 activity, down-regulating the proinflammatory signaling effect of the released High-Mobility Group Box 1 (HMGB1) [82]. Another relevant triterpene in Barringtonia species is bartogenic acid, a derivative of ursolic acid which has three hydroxyl groups and two carboxyl groups. These organic functions make bartogenic acid even more polar than ursolic acid, which has only one hydroxyl and one carboxyl group. In an in vivo study, bartogenic acid showed anti-inflammatory action as potent as that of diclofenac [7]. However, more studies are needed to understand the inflammatory pathways targeted by this compound, since triterpenes can modulate different inflammatory mediators.

A comparison with commercial medications helps us understand the importance of searching for new anti-inflammatory drug candidates. NSAIDs inhibit prostanoid biosynthesis through their activity on the cyclooxygenase enzymes (COX) COX-1 and COX-2 isoenzymes [83]. The inhibitory activity of COX-1 by NSAIDs is associated with most of the side effects of these drugs. Inhibition of COX-1 promotes a reduction in gastrointestinal mucosal protection, renal function, and platelet activity [3]. Selective COX-2 inhibitor drugs, called “coxibs,” also have some serious side effects, such as an increased risk of myocardial infarction, stroke, heart failure, renal failure, and hypertension, as well as other thrombotic events [3,84].

Anti-inflammatory evaluation studies with Lecythidaceae species have identified promising results. However, there are limitations that hinder understanding and motivate further investigation. These include the lack of information on the chemical composition of the extracts and bioactive fractions, the difficulties in obtaining their pure compounds in sufficient quantities for evaluation, and the safety of using these samples in in vivo studies.

3.5. Ethnopharmacological Uses

The description of anti-inflammatory properties of medicinal plants by popular knowledge may be inserted in a set of terms that represent physiological symptoms or the response of the immune system. The inflammatory process is a defense mechanism of the body against harmful agents, such as pathogens, toxic compounds, radiation, and cell damage, necessary for homeostasis of the body and which is recognized by symptoms such as redness, fever, swelling, pain, and loss of tissue function [85,86].

From the action of one of these agents, the immune system will initiate a sequence of cellular and molecular events, such as increased vascular permeability, recruitment of leukocytes, and release of pro-inflammatory mediators. Several pathologies arise from inflammatory processes or concomitantly with one, as inflammation can be infectious or non-infectious [86].

Thus, when an ethnopharmacological survey is performed, the terms identified for a medicinal plant may represent the symptoms treated and not necessarily the action against a pathology. For example, fever, sore throat, and colic are symptoms that can have several causes but may be linked to inflammation. Thus, the medicine prepared from a medicinal plant may have a common therapeutic effect for all these symptoms, such as anti-inflammatory action, but will not necessarily be active against the possible pathologies responsible for these symptoms.

Identifying these therapeutic potentials through ethnopharmacological surveys provides a vital foundation for guiding future scientific investigation. For the family Lecythidaceae, reports of medicinal use have been found linked to the anti-inflammatory action of their species in Asia and South America.

Species of the genus Barringtonia have been used traditionally in Indonesia to treat arthralgia, chest pain, and hemorrhoids, such as Barringtonia acutangula (L.) Gaertn., which is also used for cases of psychological disorders and dysmenorrhea, which demonstrated anti-inflammatory activity in systemic inflammatory models [18,26]. However, there are other species of this genus used for the same purposes that have not been investigated so far.

In Malaysia, the use of Barringtonia racemosa fruits has been reported to treat coughs, asthma, and diarrhea, while the seeds are used for colic and ophthalmic problems [24]. This species is also used in traditional Indian medicine, cited in the Ayurvedic literature for the treatment of pain, inflammation, and rheumatism. Another species used in formulations of Ayurvedic medicine is B. acutangula, which is indicated for joint pain, intermittent fever, eye diseases, stomach disorders, diarrhea, coughs, dyspnea, anthelmintic, leprosy, hemiplegia, spleen diseases, and poisoning [7,28,87,88]. In the southern provinces of Vietnam, this same species is abundant and used in folk medicine to treat fever, stomach pain, and diarrhea [25,89].

In India, the tree species Careya arborea is traditionally used in the treatment of inflammation, bronchitis, skin diseases, tumors, dyspepsia, ulcer, toothache, and earache, and as an antidote to snake venom; in these cases, there is always an inflammatory response of the organism resulting from injury, physiological disturbance, or invasion of pathogens. In addition to these medicinal properties, action against worms, diarrhea, dysentery with bloody feces, epileptic seizures, and astringent action are also mentioned [4,90,91].

In South America, species of Lecythidaceae are used as medicine, such as the species Couroupita guianensis Aublet, known in Brazil as “apricot”, “ape nut”, and “Andean almond”, which has been used in the form of infusions or teas obtained from leaves, flowers, and bark to treat hypertension, tumors, inflammatory processes, pain, and rheumatic diseases [10,92].

Couratari rubra Gardner. Ex Miers (synonym Cariniana rubra Miers; Lecythidaceae), popularly known as “red jequitibá”, has been used to treat inflammatory processes in the form of decoctions and infusions of stem barks. This traditional remedy is mainly used to treat oophoritis, sore throat, and venereal diseases [54,93]. In traditional Brazilian medicine, topical uses for C. rubra are also found, such as decoction or infusion of 3% stem bark, which are used to treat hemorrhoids, leukorrhea, and ovarian/uterine inflammations [55,94].

Despite the few existing studies addressing the ethnopharmacological uses of Cariniana species, an infusion made with the bark of this species has been reported to be used as an anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial agent [34,95].

4. Conclusions

This integrative review consolidates compelling evidence from in vitro, in vivo, and clinical studies, demonstrating that extracts, fractions, and compounds from the Lecythidaceae family possess significant anti-inflammatory and antinociceptive properties. This robust body of evidence strongly justifies the traditional use of these plants in treating pain and inflammatory conditions. A particularly significant finding is the elucidation of a novel mechanism of action for Barringtonia angusta, which targets the NF-κB and TAK1/AP-1 signaling pathways. This identifies a promising and specific target for the development of new anti-inflammatory therapies. Despite their prominence in traditional medicine systems across Asia and South America, the pharmacological potential of the Lecythidaceae family remains largely untapped. Future research must prioritize bioassay-guided isolation of active constituents, detailed mechanistic studies on key molecular targets, and well-designed clinical trials to fully leverage the therapeutic promise of Lecythidaceae species in developing novel anti-inflammatory agents.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.C.P., T.G.D. and T.F.F.; methodology, A.G.N.F. and M.S.N.; formal analysis, Q.C.F., F.E.A.C.-J. and L.P.B.T.; writing—original draft preparation, E.C.P. and Q.C.F.; writing—review and editing, A.L.F.P. and R.P.D.; visualization, all; project administration, Q.C.F.; funding acquisition, F.E.A.C.-J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES), Brazil, grant number Finance Code 001, Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), Brazil, grant number 441189/2023-7, and Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa e ao Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico do Maranhão (FAPEMA), Brazil, grant number 04886/24.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study were derived from the following resources available in the public domain: PubMed at https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/; Science Direct at https://www.sciencedirect.com/; Periodicos Capes at https://www.periodicos.capes.gov.br/; at Web of Science at https://clarivate.com/academia-government/scientific-and-academic-research/research-discovery-and-referencing/web-of-science/.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Brazilian agencies FAPEMA, CAPES, and CNPq for their financial support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abdulkhaleq, L.A.; Assi, M.A.; Abdullah, R.; Zamri-Saad, M.; Taufiq-Yap, Y.H.; Hezmee, M.N.M. The crucial roles of inflammatory mediators in inflammation: A review. Vet. World. 2018, 11, 627–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, K.R.; Patil, C.R. Anti-inflammatory activity of bartogenic acid containing fraction of fruits of Barringtonia racemosa Roxb. in acute and chronic animal models of inflammation. J. Tradit. Complement. Med. 2017, 7, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batlouni, M. Anti-inflamatórios não esteroides: Efeitos cardiovasculares, cérebro-vasculares e renais [Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: Cardiovascular, cerebrovascular and renal effects]. Arq. Bras. Cardiol. 2010, 94, 556–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begum, R.; Sharma, M.; Pillai, K.K.; Aeri, V.; Sheliya, M.A. Inhibitory effect of Careya arborea on inflammatory biomarkers in carrageenan-induced inflammation. Pharm. Biol. 2015, 53, 437–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begum, R.; Sheliyab, M.A.; Mirc, S.R.; Singhd, E.; Sharmab, M. Inhibition of proinflammatory mediators by coumaroyl lupendioic acid, a new cutan-type triterpene from Careya arborea, on inflammation-induced animal model. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2017, 206, 376–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima-Junior, L.J.A.C.; Costa, G.C.; Reis, A.S.; Bezerra, J.L.; Patrício, F.J.B.; Silva, L.A.; Amaral, F.M.M.; Nascimento, F.R.F. Inhibition of in vitro macrophage infection by Leishmania amazonensis by extract and fractions from Chenopodium ambrosioides L. Ciênc. Saúde 2014, 16, 46–53. Available online: https://periodicoseletronicos.ufma.br/index.php/rcisaude/article/view/3410 (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Patil, K.R.; Patil, C.R.; Jadhav, R.B.; Mahajan, V.K.; Patil, P.R.; Gaikwad, P.S. Anti-Arthritic Activity of Bartogenic Acid Isolated from Fruits of Barringtonia racemosa Roxb. (Lecythidaceae). Evid. Based Complement. Alternat Med. 2011, 2011, 785245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, K.W.; Mat-Junit, S.; Ismail, A.; Aminudin, N.; Abdul-Aziz, A. Polyphenols in Barringtonia racemosa and their protection against oxidation of LDL, serum and haemoglobin. Food Chem. 2014, 146, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, É.L.d.F.; Oliveira, J.P.d.C.; de Araújo, M.R.S.; Rai, M.; Chaves, M.H. Phytochemical profile and ethnopharmacological applications of Lecythidaceae: An overview. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 274, 114049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, D.C.M.; Azevedo, M.M.B.; Silva, D.O.E.; Romanos, M.T.V.; Souto-Padrón, T.C.B.S.; Alviano, C.S.; Alviano, D.S. In vitro anti-MRSA activity of Couroupita guianensis extract and its component Tryptanthrin. Nat. Prod. Res. 2017, 31, 2077–2080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittemore, R.; Knafl, K. The integrative review: Updated methodology. J. Adv. Nurs. 2005, 52, 546–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souza, M.T.; Silva, M.D.; Carvalho, R. Revisão integrativa: O que é e como fazer? Einstein 2010, 8, 102–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, C.M.d.C.; Pimenta, C.A.d.M.; Nobre, M.R. The PICO strategy for the research question construction and evidence search. Rev. Lat. Am. Enfermagem 2007, 15, 508–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelaidi, N.; Dimopoulou, K.; Dimopoulou, D.; Krikri, A.; Siouli, C.; Berikopoulou, M.M.; Zavras, N.; Dimopoulou, A. Entero-Enteric Fistula Following Multiple Magnet Ingestion in Children: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 6235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; The PRISMA Group. Reprint-Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. Phys. Ther. 2009, 89, 873–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, M.; Lee, J.; Kim, H.G.; Kim, J.K.; Kim, H.; Shin, K.K.; Bach, T.T.; Eum, S.M.; Lee, J.S.; Choung, E.S.; et al. Anti-inflammatory effect of Barringtonia angusta methanol extract is mediated by targeting of Src in the NF-κB signalling pathway. Pharm. Biol. 2021, 59, 799–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, A.T.; Kim, M.Y.; Cho, J.Y. TAK1/AP-1-Targeted Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Barringtonia augusta Methanol Extract. Molecules 2021, 26, 3053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitohang, N.A.; Putra, E.D.L.; Kamil, H.; Musman, M. Acceleration of wound healing by topical application of gel formulation of Barringtonia racemosa (L.) Spreng kernel extract. F1000Research 2022, 11, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shikha, P.; Latha, P.G.; Suja, S.R.; Anuja, G.I.; Shyamal, S.; Shine, V.J.; Sini, S.; Krishnakumar, N.M.; Rajasekharan, S. Anti-inflammatory and analgesic activity of Barringtonia racemosa Roxb. Fruits. Indian. J. Nat. Prod. Resour. 2010, 1, 356–361. [Google Scholar]

- Osman, N.I.; Sidik, N.J.; Awal, A.; Adam, N.A.M.; Rezali, N.I. In Vitro xanthine oxidase and albumin denaturation inhibition assay of Barringtonia racemosa L. and total phenolic content analysis for potential anti-inflammatory use in gouty arthritis. J. Intercult. Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 5, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deraniyagala, S.A.; Ratnasooriya, W.D.; Goonasekara, C.L. Antinociceptive effect and toxicological study of the aqueous bark extract of Barringtonia racemosa on rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2003, 86, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behbahani, M.; Ali, A.M.; Muse, R.; Mohd, N.B. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities of leaves of Barringtonia racemosa. J. Med. Plants Res. 2007, 95–102. [Google Scholar]

- Vien, L.T.; Van, Q.T.T.; Hanh, T.T.H.; Huong, P.T.T.; Thuy, N.T.K.; Cuong, N.T.; Dang, N.H.; Thanh, N.V.; Cuong, N.X.; Nam, N.H.; et al. Flavonoid glycosides from Barringtonia acutangula. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2017, 27, 3776–3781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imam, Z.M.; Sultana, S.; Akter, S. Antinociceptive, antidiarrheal, and neuropharmacological activities of Barringtonia acutangula. Pharm. Biol. 2012, 50, 1078–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thirumal, M.; Bharathi, R.V.; Kumudhaveni, B.; Kishore, G. Anti-arthritic activity of the chloroform extract of Barringtonia acutangula (L.) Gaertn. leaves on wister rats. Scholars Research Library. Pharm. Lett. 2013, 5, 374–380. [Google Scholar]

- Quader, S.H.; Islam, S.U.L.; Saifullah, A.; Majumder, F.U.; Hannan, J. Evaluation of the Anti-Nociceptive and Anti-Inflammatory Activities of the Ethanolic Extract of Barringtonia acutangula Linn. (Lecythidaceae) Roots. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Rev. Res. 2013, 20, 24–32. [Google Scholar]

- Vien, L.T.; Hanh, T.T.H.; Quang, T.H.; Thao, D.T.; Cuong, N.T.; Cuong, N.X.; Nam, N.H.; Van Minh, C. Acylated flavonoid glycosides from Barringtonia pendula and their inhibition on lipopolysaccharide-induced nitric oxide production in RAW264.7 cells. Fitoterapia 2023, 171, 105699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cury, M.F.R.; Olivares, E.Q.; Garcia, R.C.; Toledo, G.Q.; Anselmo, N.A.; Paskakulis, L.C.; Botelho, F.F.R.; Carvalho, N.Z.; Silva, A.A.D.; Agren, C.; et al. Inflammation and kidney injury attenuated by prior intake of Brazil nuts in the process of ischemia and reperfusion. J. Bras. Nefrol. 2018, 40, 312–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anselmo, N.A.; Paskakulis, L.C.; Garcias, R.C.; Botelho, F.F.R.; Toledo, G.Q.; Cury, M.F.R.; Carvalho, N.Z.; Mendes, G.E.F.; Iembo, T.; Bizotto, T.S.G.; et al. Prior intake of Brazil nuts attenuates renal injury induced by ischemia and reperfusion. J. Bras. Nefrol. 2018, 40, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockler-Pinto, M.B.; Mafra, D.; Moraes, C.; Lobo, J.; Boaventura, G.T.; Farage, N.E.; Silva, W.S.; Cozzolino, S.F.; Malm, O. Brazil nut (Bertholletia excelsa, H.B.K.) improves oxidative stress and inflammation biomarkers in hemodialysis patients. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2014, 158, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, G.B.S.; Reis, B.Z.; Rogero, M.M.; Vargas-Mendez, E.; Júnior, F.B.; Cercato, C.; Cozzolino, S.M.F. Consumption of Brazil nuts with high selenium levels increased inflammation biomarkers in obese women: A randomized controlled trial. Nutrition 2019, 63–64, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milani, G.B.; Camponogara, C.; Piana, M.; Silva, C.R.; Oliveira, S.M. Cariniana domestica fruit peels present topical anti-inflammatory efficacy in a mouse model of skin inflammation. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2019, 392, 513–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, E.N.; Lima, J.C.; Noldin, V.F.; Cechinel-Filho, V.; Rao, V.S.; Lima, E.F.; Schmeda-Hirschmann, G.; Sousa, P.T., Jr.; Martins, D.T. Anti-inflammatory, antinociceptive, and antipyretic effects of methanol extract of Cariniana rubra stem bark in animal models. An. Acad. Bras. Cienc. 2011, 83, 557–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, D.N.P.B.; Adriana, F.; Martins, D.T.O.; Borges, Q.I.; Lindote, M.V.N.; Zoratti, M.T.R.; Oliveira, R.G.; Torquato, H.F.V.; Gazoni, V.F.; Costa, L.A.M.A.D.; et al. Methanolic extract of Cariniana rubra Gardner ex Miers stem bark negatively regulate the leukocyte migration and TNF-α and up-regulate the annexin-A1 expression. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 270, 113778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinheiro, M.M.; Bessa, S.O.; Fingolo, C.E.; Kuster, R.M.; Matheus, M.E.; Menezes, F.S.; Fernandes, P.D. Antinociceptive activity of fractions from Couroupita guianensis Aubl. leaves. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2010, 127, 407–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, M.M.; Fernandes, S.B.; Fingolo, C.E.; Boylan, F.; Fernandes, P.D. Anti-inflammatory activity of ethanol extract and fractions from Couroupita guianensis Aublet leaves. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2013, 146, 324–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthulakshmi, V.; Dhilip Kumar, C.; Sundrarajan, M. Biological applications of green synthesized lanthanum oxide nanoparticles via Couroupita guianensis abul leaves extract. Anal. Biochem. 2022, 638, 114482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, T.; Pisanti, S.; Martinelli, R.; Celano, R.; Mencherini, T.; Re, T.; Aquino, R.P. Couroupita guianensis bark decoction: From Amazonian medicine to the UHPLC-HRMS chemical profile and its role in inflammation processes and re-epithelialization. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2023, 313, 116579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, L.L.; Gomes, B.S.; Sousa-Neto, B.P.; Oliveira, J.P.; Ferreira, E.L.; Chaves, M.H.; Oliveira, F.A. Effects of Lecythis pisonis Camb. (Lecythidaceae) in a mouse model of pruritus. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2012, 139, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandão, M.S.; Pereira, S.S.; Lima, D.F.; Oliveira, J.P.C.; Ferreira, E.L.F.; Chaves, M.H.; Almeida, F.R.C. Antinociceptive effect of Lecythis pisonis Camb. (Lecythidaceae) in models of acute pain in mice. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2013, 146, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Martins, M.V.; Carvalho, I.M.M.d.; Caetano, M.M.M.; Toledo, R.C.L.; Xavier, A.A.; Queiroz, J.H.d. Neuroprotective effect of Sapucaia nuts (Lecythis pisonis) on rats fed with high-fat diet. Nutr. Hosp. 2016, 33, 424–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikumawoyi, V.O.; Onyemaechi, C.K.; Orolugbagbe, H.O.; Awodele, O.; Agbaje, E.O. Methanol extract of Napoleona vogelii demonstrates anti-nociceptive and anti-inflammatory activities through dopaminergic mechanism and inhibition of inflammatory mediators in rodents. Comp. Clin. Pathol. 2020, 29, 599–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bomba, F.D.; Wandji, B.A.; Piegang, B.N.; Awouafack, M.D.; Sriram, D.; Yogeeswari, P.; Kamanyi, A.; Nguelefack, T.B. Antinociceptive properties of the aqueous and methanol extracts of the stem bark of Petersianthus macrocarpus (P. Beauv.) Liben (Lecythidaceae) in mice. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 174, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orabueze, C.I.; Adesegun, S.A.; Coker, H.A. Analgesic and antioxidant activities of stem bark extract and fractions of Petersianthus macrocarpus. Phcog Res. 2016, 8, 181–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bomba, F.D.T.; Nguelefack, T.B.; Matharasala, G.; Mishra, R.K.; Battu, M.B.; Sriram, D.; Kamanyi, A.; Yogeeswari, P. Antihypernociceptive effects of Petersianthus macrocarpus stem bark on neuropathic pain induced by chronic constriction injury in rats. Inflammopharmacology 2021, 29, 1241–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Flora Online Plant List. 2025. Available online: https://wfoplantlist.org/taxon/wfo-7000000322-2025-06 (accessed on 22 December 2022).