The Future of Precision Medicine: Targeted Therapies, Personalized Medicine and Formulation Strategies

Abstract

1. Introduction

Benefits of Targeted Therapies and Personalized Medicine

| Drug | Dosage Form | Molecule Type | Indication | Target | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trastuzumab | IV | Large Molecule (mAbs) | Breast cancer | HER2 | 1998 |

| Pertuzumab | IV | Large Molecule (mAbs) | Breast cancer | HER2 | 2012 |

| Margetuximab | IV | Large Molecule (mAbs) | Breast cancer | HER2 | 2020 |

| Tucatinib | Tablet | Small Molecule (kinase inhibitor) | Breast cancer | HER2 | 2020 |

| Lapatinib | Tablet | Small Molecule (kinase inhibitor) | Breast cancer | HER2 | 2007 |

| Everolimus | Tablet | Small Molecule | Breast cancer | mTOR | 2014 |

| Palbociclib | Tablet | Small Molecule | Breast cancer | CDK4/6 | 2015 |

| Neratinib | Tablet | Small Molecule (kinase inhibitor) | Breast cancer | HER2 | 2017 |

| Alpelisib | Tablet | Small Molecule | Breast cancer | PI3K | 2022 |

| Capivasertib | Tablet | Small Molecule | Breast cancer | AKT | 2023 |

| Elacestrant | Tablet | Small Molecule | Breast cancer | ESR1 | 2023 |

| Rucaparib | Tablet | Small Molecule | Prostate cancer | PARP | 2020 |

| Olaparib | Tablet | Small Molecule | Prostate cancer | PARP | 2020 |

| Bevacizumab | IV | Large Molecule (mAbs) | NSCLC | VEGFR | 2018 |

| Sotorasib | Tablet | Small Molecule | NSCLC | KRAS | 2021 |

| Gefitinib | Tablet | Small Molecule (tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor) | NSCLC | EGFR | 2015 |

| Erlotinib | Tablet | Small Molecule (tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor) | NSCLC | EGFR | 2013 |

| Afatinib | Tablet | Small Molecule (tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor) | NSCLC | EGFR | 2013 |

| Dacomitinib | Tablet | Small Molecule (tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor) | NSCLC | EGFR | 2018 |

| Osimertinib | Tablet | Small Molecule (tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor) | NSCLC | EGFR | 2015 |

| Mobocertinib | Capsule | Small Molecule (tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor) | NSCLC | EGFR | 2021 |

| Lazertinib | Tablet | Small Molecule (Kinase Inhibitor) | NSCLC | EGFR | 2024 |

| Amivantamab | IV | Large Molecule (mAbs) | NSCLC | EGFR | 2024 |

| Tepotinib | Tablet | Small Molecule | NSCLC | MET | 2024 |

| Crizotinib | Tablet | Small Molecule | NSCLC | ALK | 2011 |

| Ceritinib | Tablet | Small Molecule | NSCLC | ALK | 2014 |

| Lorlatinib | Tablet | Small Molecule | NSCLC | ROS | 2018 |

| Sotorasib | Tablet | Small Molecule (tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor) | NSCLC | KRAS | 2021 |

| Adagrasib | Tablet | Small Molecule (tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor) | NSCLC | KRAS | 2022 |

| Alectinib | Tablet | Small Molecule | NSCLC | ALK | 2024 |

| Esartinib | Tablet | Small Molecule | NSCLC | ALK | 2024 |

| Tepotinib | Tablet | Small Molecule | NSCLC | c-Met | 2021 |

| Capmatinib | Tablet | Small Molecule | NSCLC | c-Met | 2022 |

| Larotrectinib | Tablet | Small Molecule | NSCLC | TRKA/B/C | 2018 |

| Repotrectinib | Capsule | Small Molecule | NSCLC | TRKA/B/C | 2023 |

| Cetuximab | IV | Large Molecule (mAbs) | CRC | EGFR | 2004 |

| Panitumumab | IV | Large Molecule (mAbs) | CRC | EGFR | 2006 |

| Regorafenib | Tablet | Small Molecule (Multi-Kinase Inhibitor) | CRC | VEGFR-1/2/3 | 2012 |

| Tislelizumab-JSGR | IV | Large Molecule | Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma | PD-L1 | 2024 |

| Tovorafenib | Tablet | Small Molecule | Pediatric low-grade glioma | BRAF fusion/rearrangement/V600 | 2024 |

| Zanidatamab | IV | Large Molecule (mAbs) | Biliary tract cancers | HER2 | High priority review |

| Fruquintinib | Capsule | Small Molecule | CRC | VEGFR1/2/3 | 2023 |

| Olutasidenib | Capsule | Small molecule | Acute myeloid leukemia | isocitrate dehydrogenase-1 (IDH1) | 2022 |

| Pirtobrutinib | Tablet | Small Molecule | Chronic lymphocytic leukemia | BTK | 2023 |

| Quizartinib | Tablet | Small Molecule | Acute myeloid leukemia | FLT3 | 2023 |

| Epcoritamab-BYSP | SC | Large Molecule Bispecific antibody | Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma | CD20, CD3 | 2023 |

| Ritlecitinib | Tablet | Large Molecule Bispecific antibody | Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma | CD20, CD3 | 2023 |

| Asciminib | Tablet | Small Molecule (tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor) | Philadelphia chromosome-positive chronic myeloid leukemia (Ph+ CML) | BCR-ABL1 | 2021 |

| Talquetamab-TGVS | SC | Large Molecule Bispecific antibody | Myeloma | CD3 receptor and G proteincoupled receptor class C group 5 member D (GPRC5D) | 2023 |

| Elranatamab-BCMM | IV | Large Molecule Bispecific antibody | Myeloma | B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA) and CD3 | 2023 |

| Mosunetuzumab-AXGB | IV | Large Molecule Bispecific antibody | Refractory follicular lymphoma | Bispecific CD20 and CD3 | 2022 |

| Dapagliflozin | Tablet | Small Molecule | Diabetes | SGLT2 | 2012 |

| Canagliflozin | Tablet | Small Molecule | Diabetes | SGLT2 | 2013 |

| Bexagliflozin | Tablet | Small Molecule | Diabetes | SGLT2 | 2023 |

| Sotagliflozin | Tablet | Small Molecule | Diabetes | SGLT2 | 2023 |

| Lixisenatide | IV | Large Molecule (Poly peptide) | Diabetes | GLP-1 | 2016 |

| Exenatide | SC | Large Molecule (Poly peptide) | Diabetes | GLP-1 | 2005 |

| Semaglutide | IM | Large Molecule (Poly peptide) | Diabetes | GLP-1 | 2017 |

| Albiglutide | IM | Large Molecule (Poly peptide) | Diabetes | GLP-1 | 2014 |

| Dulaglutide | IM | Large Molecule (Poly peptide) | Diabetes | GLP-1 | 2014 |

| Tirzepatide | SC | Large Molecule (Poly peptide) | Diabetes | GLP-1 | 2022 |

| Sitagliptin | Tablet | Small Molecule | Diabetes | DPP-4 | 2006 |

| Saxagliptin | Tablet | Small Molecule | Diabetes | DPP-4 | 2009 |

| Linagliptin | Tablet | Small Molecule | Diabetes | DPP-4 | 2012 |

| Alogliptin | Tablet | Small Molecule | Diabetes | DPP-4 | 2013 |

| Teplizumab-MZWV | IV | Large molecule (mAbs) | To delay the onset of stage 3 type 1 diabetes | CD3 | 2022 |

| Omalizumab | SC | Large Molecule (mAbs) | Asthma | IgE | 2003 |

| Mepolizumab | SC | Large Molecule (mAbs) | Asthma | IL-5 | 2015 |

| Reslizumab | IV | Large Molecule (mAbs) | Asthma | IL-5 | 2016 |

| Benralizumab | SC | Large Molecule (mAbs) | Asthma | IL-5Rα | 2017 |

| Dupilumab | SC | Large Molecule (mAbs) | Asthma | IL-4Rα | 2017 |

| Tezepelumab | SC | Large Molecule (mAbs) | Asthma | Thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) | 2022 |

| Montelukast | Oral (Tablet) | Small Molecule | Asthma | LTRAs | 1998 |

| Aducanumab-AVWA | IV | Large Molecule (mAbs) | Alzheimer’s disease | Amyloid β | 2021 |

| Lecanemab-IRMB | IV | Large Molecule (mAbs) | Alzheimer’s disease | Amyloid β (Aβ) | 2023 |

| Donanemab-AZBT | IV | Large Molecule (mAbs) | Alzheimer’s disease | Amyloid β | 2024 |

| Drug | Dosage Form | Molecule Type | Indication | Receptor/Target | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Datopotamab Deruxtecan-DLNK | IV | Large Molecule (ADC) | Unresectable/metastatic HR+, HER2- breast cancer | TROP2 | 2025 |

| Treosulfan | IV | Small Molecule | Conditioning for stem cell transplant (AML, MDS) | Alkylating agent | 2025 |

| Mirdametinib | Oral tablet | Small Molecule | Neurofibromatosis type 1 (plexiform neurofibromas) | MEK1/2 inhibitor | 2025 |

| Vimseltinib | Oral tablet | Small Molecule | Tenosynovial giant cell tumor | CSF1R | 2025 |

| Durvalumab | IV | Large Molecule (mAbs) | Muscle-invasive bladder cancer | PD-L1 | 2025 |

| Denosumab-BMWO, Biosimilar | SC | Large Molecule (mAbs) | Osteoporosis, cancer-related skeletal events | RANKL | 2025 |

| Denosumab Biosimilar | SC | Large Molecule (mAbs) | Osteoporosis, cancer-related skeletal events | RANKL | 2025 |

| Inebilizumab | IV | Large Molecule (mAbs) | Immunoglobulin G4-related disease | CD19 | 2025 |

| Nitisinone | Oral capsule | Small Molecule | Alkaptonuria | HGA dioxygenase inhibitor | 2025 |

| Atrasentan | Oral tablet | Small Molecule | IgA nephropathy | Endothelin A receptor | 2025 |

| Beremagene Geperpavec | Topical gel | Large Molecule (gene therapy) | Recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa | COL7A1 gene | 2025 |

| Mepolizumab | SC | Large Molecule (mAbs) | Eosinophilic COPD phenotype | IL-5 | 2025 |

| Roflumilast Foam | Topical foam | Small Molecule | Scalp/body psoriasis | PDE4 inhibitor | 2025 |

| Clesrovimab | IM | Large Molecule (mAbs) | RSV prevention in infants | RSV F protein | 2025 |

| Lenacapavir | SC | Small | HIV prevention (PrEP) | HIV capsid protein | 2025 |

| Donanemab-AZBT | IV | Large Molecule (mAbs) | Alzheimer’s disease | Amyloid beta (Aβ); ApoE ε4 status | 2024 |

| Deuruxolitinib | Tablet | Small Molecule | Alopecia areata | JAK1/2; CYP2C9 status | 2024 |

| Lisocabtagene Maraleucel | IV | Large Molecule | Mantle cell lymphoma | CD19 | 2024 |

| Gene Therapy For Metachromatic Leukodystrophy | IV | Large Molecule | Metachromatic leukodystrophy | ARSA gene | 2024 |

| Gene Therapy For Aadc Deficiency | IV | Large Molecule | Aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase deficiency | DDC gene | 2024 |

| Gene Therapy For Hemophilia B | IV | Large Molecule | Hemophilia B (congenital factor IX deficiency) | Factor IX gene | 2024 |

| Repotrectinib | Capsule | Small Molecule | NSCLC | ROS1 | 2023 |

| Pegunigalsidase Alfa-IWX | Injection | Large Molecule (Enzyme) | Fabry disease. | Alpha-galactosidase A, globotriaosylceramide (Gb3) | 2023 |

| Iptacopan | Capsule | Small Molecule | Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. | Factor B, alternative complement pathway | 2023 |

| Sparsentan | Tablet | Small Molecule | Proteinuria associated with primary immunoglobulin A nephropathy. | UPCR | 2023 |

| Leniolisib | Tablets | Small Molecule | Activated phosphoinositide 3-kinase delta (PI3Kδ) syndrome. | PI3Kδ | 2023 |

| Velmanase Alfa-TYCV | Injection | Large Molecule (Enzyme) | Non-central nervous system of alpha-mannosidosis. | Alpha-mannosidase, mannosidase alpha class 2B member 1 | 2023 |

| Lecanemab-IRMB | Injection | Large Molecule (mAbs) | Alzheimer’s disease. | ApoE ϵ4 | 2023 |

| Toripalimab-TPZI | Injection | Large Molecule (PD-1PD-L1 Inhibitors) | Nasopharyngeal carcinoma. | Programmed death receptor-1 (PD-1) | 2023 |

| Elacestrant | Tablets | Small Molecule | Breast cancer. | ESR1, HER2, ER | 2023 |

| Cipaglucosidase Alfa-ATGA | Lyophilized powder for injection | Large Molecule (Enzyme) | Pompe disease | Lysosomal acid alpha-glucosidase (GAA) | 2023 |

| Tofersen | Injection | Large Molecule (Neurologics, Antisense Oligonucleotides) | Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). | SOD1 | 2023 |

| Nedosiran | Injection | Large Molecule (RNAi Agents) | hyperoxaluria type 1. | Hepatic lactate dehydrogenase | 2023 |

| Rozanolixizumab-NOLI | Injection | Large Molecule (Fc Receptor Antagonists) | Generalized myasthenia gravis. | AChR or MuSK Ab | 2023 |

| Palovarotene | Capsules | Small Molecule | Reduction in volume of new heterotopic ossification in fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. | BMP/ALK2 | 2023 |

| Capivasertib | Tablets | Small Molecule | Breast cancer, in combination with fulvestrant. | HR, HER2 biomarkers, PIK3CA/AKT1/PTEN | 2023 |

| Quizartinib | Tablets | Small Molecule | acute myeloid leukemia, | FLT3 internal tandem duplication | 2023 |

| Pozelimab-BBFG | Injection | Large Molecule (Complement Inhibitors) | CHAPLE disease. | Terminal complement protein C5 | 2023 |

| Eplontersen | Injection | Large Molecule (Neurologics, Antisense Oligonucleotides) | Polyneuropathy of hereditary transthyretin-mediated amyloidosis. | Transthyretin | 2023 |

| Zilucoplan | Injection | Large Molecule | Myasthenia gravis. | AChR Ab | 2023 |

| Retifanlimab-DLWR | Injection | Large Molecule (PD-1PD-L1 Inhibitors) | Metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma. | Programmed death receptor-1 (PD-1) | 2023 |

| Omidubicel | Suspension IV | Large Molecule (Hematopoietic Progenitor Cells, Cord Blood) | Hematologic malignancies | 2023 | |

| Beremagene Geperpavec-SVDT | Topical gel | Large Molecule (Dermatologics) | Dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa with mutation(s) in the collagen type VII alpha 1 chain gene. | collagen type VII alpha 1 chain gene. | 2023 |

| Delandistrogene Moxeparvovec-ROKL | Suspension IV | Large Molecule | Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) | DMD gene | 2023 |

| Valoctocogene Roxaparvovec-RVOX | Suspension IV | Large Molecule (Clotting Factors, Gene Therapy) | Hemophilia A | 2023 | |

| Exgamglogene Autotemcel | Suspension IV | Large Molecule (autologous cellular immunotherapy) | Sickle cell disease. | Sickle cell disease, BCL11A gene | 2023 |

| Lovotibeglogene Autotemcel | Suspension IV | Large Molecule (Hematologics, Kinase Inhibitor) | sickle cell disease | Sickle cell disease, β-globin gene | 2023 |

| Abrocitinib | Tablets | Small Molecule | Atopic dermatitis. | Janus kinase 1 (JAK1) | 2022 |

| Tebentafusp-TEBN | IV | Large Molecule (Monoclonal Antibodies) | Uveal melanoma. | Human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-A02:01 | 2022 |

| Mitapivat | Tablets | Large Molecule (Pyruvate Kinase Activators) | Pyruvate kinase deficiency. | Pyruvate kinase (PK) | 2022 |

| Nivolumab And Relatlimab-RMBW | Injection | Large Molecule (PD-1PD-L1 Inhibitors, Monoclonal Antibodies) | Metastatic melanoma. | PD-1, LAG-3 | 2022 |

| Lutetium (177lu) Vipivotide Tetraxetan | Injection | Large Molecule (Radiopharmaceuticals) | Prostate cancer. | Prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) | 2022 |

| Vutrisiran | Injection | Large Molecule (RNAi Agents) | Hereditary transthyretin-mediated amyloidosis. | Transthyretin (TTR) | 2022 |

| Olipudase Alfa | Injection | Large Molecule (Enzymes, Metabolic) | Acid sphingomyelinase deficiency (ASMD). | Acid sphingomyelinase | 2022 |

| Futibatinib | Tablets | Small Molecule | Cholangiocarcinoma. | FGFR2 | 2022 |

| Mirvetuximab Soravtansine-GYNX | IV | Large Molecule (mAbs) | Ovarian cancer | Folate receptor alpha (FRα) | 2022 |

| Olutasidenib | Capsules | Small Molecule | Acute myeloid leukemia. | Isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 (IDH1) | 2022 |

| Adagrasib | Tablets | Small Molecule | NSCLC | KRAS G12C | 2022 |

| Lenacapavir | Tablets and Injection | Large Molecule | Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. | HIV-1 | 2022 |

| Ciltacabtagene Autoleucel | Injection | Large Molecule (CAR-T Cell Therapies) | Refractory multiple myeloma | B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA) | 2022 |

| Betibeglogene Autotemcel | Suspension IV | Large Molecule (Clotting Factors, Gene Therapy) | beta thalassemia | Beta-globin | 2022 |

| Elivaldogene Autotemcel | Suspension IV | Large Molecule (Regenerative Therapy) | active cerebral adrenoleukodystrophy. | Adrenoleukodystrophy protein (ALDP) | 2022 |

| Etranacogene Dezaparvovec-DRLB | Suspension IV | Large Molecule (Clotting Factors, Gene Therapy) | Hemophilia B | Functional variant (R338L) of human factor IX | 2022 |

| Nadofaragene Firadenovec-VNCG | Suspension | Large Molecule (Biological Response Modifiers) | Bacillus Calmette-Guérin-unresponsive bladder cancer | Human interferon alfa-2b (IFNα2b) | 2022 |

| Cabotegravir And Rilpivirine | Injection | Large Molecule (HIV, NNRTIs, HIV, Integrase Inhibitors) | HIV infection | HIV-1 integration (cabotegravir); HIV-1 replication (rilpivirine) | 2021 |

| Tepotinib | Tablets | Small Molecule | NSCLC | MET exon 14 biomarker | 2021 |

| Evinacumab-DGNB | Injection | Large Molecule (Lipid-Lowering Agents) | hypercholesterolemia | Homozygous FH (hoFH) status | 2021 |

| Casimersen | Injection | Large Molecule (Neurologics, Antisense Oligonucleotides) | Duchenne muscular dystrophy | DMD gene exon 45 | 2021 |

| Fosdenopterin | Injection | Small Molecule | Molybdenum cofactor deficiency (MoCD) | MoCD Type A status | 2021 |

| Dostarlimab-GXLY | Injection | Large Molecule (PD-1PD-L1 Inhibitors, Antineoplastics Monoclonal Antibody, Monoclonal Antibodies) | Endometrial cancer | dMMR; PD-L1 | 2021 |

| Amivantamab-VMJW | Injection | Large Molecule (Antineoplastics EGFR Inhibitors, MET Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors) | NSCLC | EGFR exon 20 | 2021 |

| Sotorasib | Tablet | Small Molecule | NSCLC | KRAS G12C | 2021 |

| Infigratinib | Capsules | Small Molecule | Cholangiocarcinoma | FGFR2 | 2021 |

| Odevixibat | Capsules | Small Molecule | pruritus in PFIC | ABCB11 biomarker in PFIC Type 2 patients | 2021 |

| Avalglucosidase alfa-NGPT | Injection | Large Molecule (Enzymes, Metabolic) | Pompe disease | Lysosomal acid alpha-glucosidase (GAA) deficiency biomarker | 2021 |

| Belzutifan | Tablets | Small Molecule | Von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) disease | UGT2B17 and CYP2C19 | 2021 |

| Mobocertinib | Capsules | Small Molecule | NSCLC | EGFR exon 20 | 2021 |

| Avacopan | Capsules | Small Molecule | Adjunct therapy for active severe vasculitis (GPA and MPA) | ANCA | 2021 |

| Asciminib | Tablets | Small Molecule | Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) | Philadelphia chromosome (Ph+) and T315I mutation biomarkers | 2021 |

| Efgartigimod alfa-FCAB | Injection | Large Molecule (Fc Receptor Antagonists) | Generalized myasthenia gravis (gmg) | Anti-acetylcholine receptor (AChR) antibody | 2021 |

| Inclisiran | Injection | Large Molecule (PCSK9 Inhibitors) | Heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia (hefh) or clinical ASCVD | PCSK9 mRNA | 2021 |

| Lisocabtagene Mar Aleucel | Cell suspension for infusion. | Large Molecule (CAR-T Cell Therapies) | Refractory large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL, high-grade B-cell lymphoma, primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma, and follicular lymphoma grade 3B) | CD19 | 2021 |

| Idecabtagene Vicleucel | Cell suspension for intravenous infusion. | Large Molecule (CAR-T Cell Therapies) | Refractory multiple myeloma | BCMA | 2021 |

| Avapritinib | Tablets | Small Molecule | Metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) | PDGFRA exon 18 | 2020 |

| Bempedoic Acid | Tablets | Small Molecule | Familial hypercholesterolemia who require additional lowering of LDL-C | FH biomarker (LOLR, APOB, PCSK9) | 2020 |

| Tucatinib | Tablets | Small Molecule | Metastatic breast cancer | HER2 | 2020 |

| Pemigatinib | Tablets | Small Molecule | Cholangiocarcinoma | FGFR2 | 2020 |

| Sacituzumab Govitecan-HZIY | Injection | Large Molecule (Antineoplastic Topoisomerase Inhibitors) | Metastatic triple-negative breast cancer | ER, PR, HER2 | 2020 |

| Capmatinib | Tablets | Small Molecule | Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) | MET exon 14 | 2020 |

| Selpercatinib | Capsules | Small Molecule | Lung and thyroid cancers | RET fusion | 2020 |

| Inebilizumab-CDON | Injection | Large Molecule (Monoclonal Antibodies) | Neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder | AQP4 | 2020 |

| Fostemsavir | Tablets | Small Molecule | HIV infection | HIV-1 expression levels | 2020 |

| Risdiplam | Oral solution | Small Molecule | Spinal muscular atrophy | SMN2 | 2020 |

| Oliceridine | Injection | Small Molecule | Acute pain | CYP2D6 | 2020 |

| Viltolarsen | Injection | Large Molecule (Neurologics, Antisense Oligonucleotides) | Duchenne muscular dystrophy | DMD gene exon 53 | 2020 |

| Satralizumab-MWGE | Injection | Large Molecule (Monoclonal Antibodies) | Neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder | AQP4 biomarker | 2020 |

| Pralsetinib | Capsules | Small Molecule | Treatment of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) | RET fusion biomarker | 2020 |

| Lonafarnib | Capsules | Small Molecule | Treatment of progeroid laminopathies | LMNA and/or ZMPSTE24 biomarkers | 2020 |

| Lumasiran | Injection | Large Molecule (RNAi Agents) | Treatment of hyperoxaluria type 1 | HAO1 biomarker | 2020 |

| Setmelanotide | Injection | Large Molecule (Melanocortin Agonists) | Treatment of obesity due to pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC) deficiency | POMC, PCSK1, or LEPR biomarkers | 2020 |

| Berotralstat | Capsules | Small Molecule | Treatment of hereditary angioedema types I and II | C1-INH biomarker | 2020 |

| Margetuximab-CMKB | Injection | Large Molecule (Antineoplastics, Anti-HER2) | Treatment of breast cancer | HER2 biomarker | 2020 |

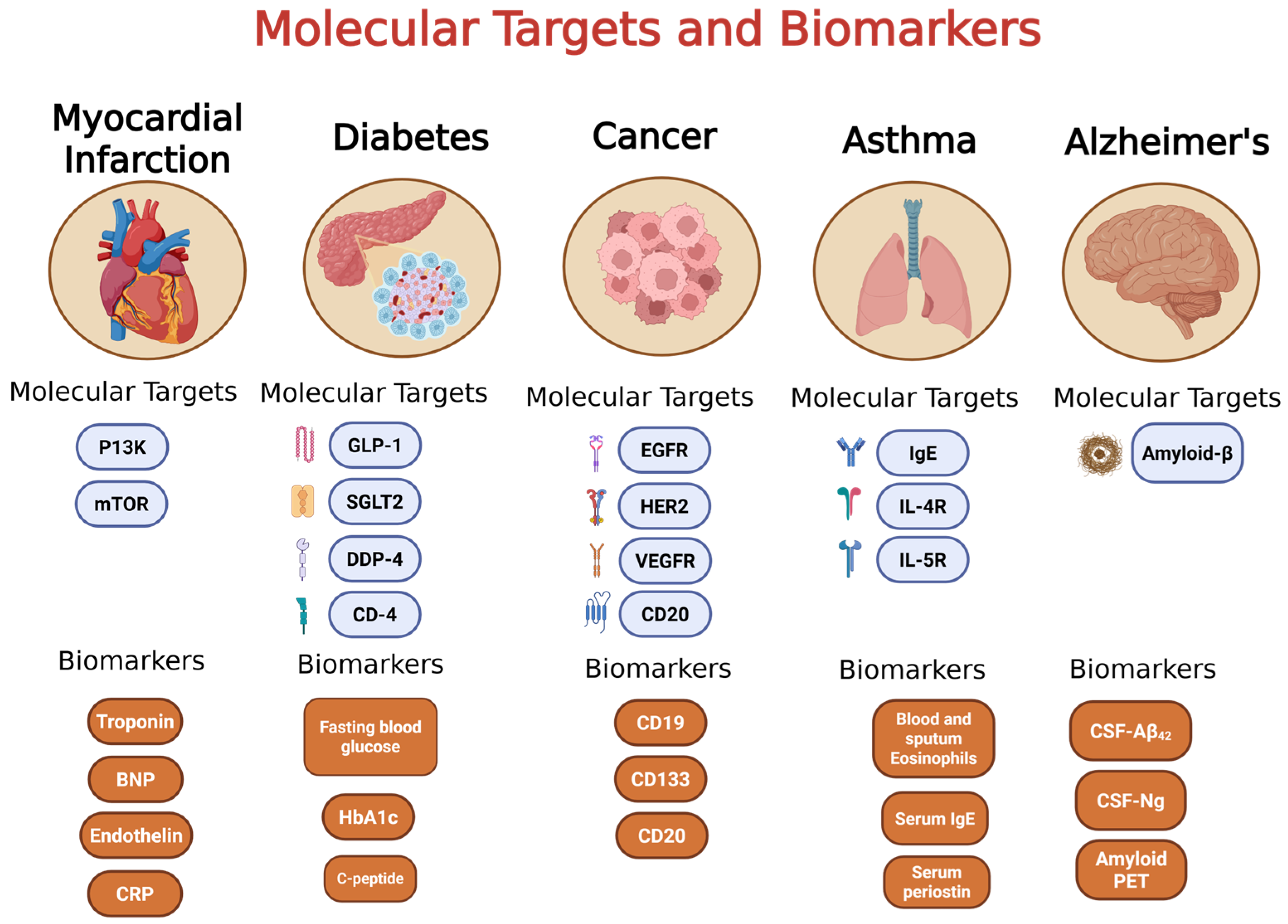

2. Cancer

2.1. Targeted Therapy and Precision Medicine in Cancer

2.2. Types of Targeted Therapies in Cancer

2.2.1. Small Molecule Kinase Inhibitors (SMKIs)

2.2.2. Monoclonal Antibodies (mAbs)

2.3. Nanotechnology in Cancer Treatment

3. Diabetes

3.1. Targeted Therapy and Personalized Medicine in Diabetes

3.1.1. Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists (GLP-1 RAs)

3.1.2. Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) Inhibitors

3.1.3. Dipeptidyl Peptidase-4 (DPP-4) Inhibitors

3.2. Personalized Therapies for Diabetes

4. Asthma

4.1. Targeted Therapy and Personalized Medicine in Asthma

4.1.1. Asthma Endotypes and Phenotypes

4.1.2. Targeted Therapies for T2-High Asthma

4.1.3. Targeted Therapies for T2-Low Asthma

5. Myocardial Infarction

5.1. Targeted Therapies and Personalized Medicine in Myocardial Infarction

5.2. Nanoparticles in Myocardial Infarction

5.2.1. Supramolecular Self-Assembled Nanoparticles

5.2.2. Magnetic Nanoparticles

5.2.3. Nanotheranostics

5.2.4. PLGA-Based Polymeric Nanoparticles

5.2.5. Dendrimers

5.2.6. Apolipoprotein AI (Apo AI) Nanoparticles

5.2.7. Lipid-Based Nanoparticles

6. Alzheimer’s Disease

6.1. Targeted Therapies and Personalized Medicine in Alzheimer’s Disease

6.1.1. Antisense Oligonucleotides

6.1.2. Small Molecules

6.1.3. Antibodies

6.1.4. CRISPR/CAS9 Genome Editing

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Murray, C.J.L. Global Burden of Disease Study 2021 (GBD 2021) Results; Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME): Seattle, WA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, D. One Size No Longer Fits All: The Personalized Medicine Trial Landscape. Available online: https://invivo.citeline.com/IV005051/One-Size-No-Longer-Fits-All-The-Personalized-Medicine-Trial-Landscape (accessed on 11 September 2024).

- Yamamoto, Y.; Kanayama, N.; Nakayama, Y.; Matsushima, N. Current Status, Issues and Future Prospects of Personalized Medicine for Each Disease. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-Y.; Wu, K.-H.; Guo, B.-C.; Lin, W.-Y.; Chang, Y.-J.; Wei, C.-W.; Lin, M.-J.; Wu, H.-P. Personalized Medicine in Severe Asthma: From Biomarkers to Biologics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Personalized Medicine Coalition. PERSONALIZED MEDICINE AT FDA: The Scope & Significance of Progress in 2022; The Personalized Medicine Coalition: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Restrepo, J.C.; Martínez Guevara, D.; Pareja López, A.; Montenegro Palacios, J.F.; Liscano, Y. Identification and Application of Emerging Biomarkers in Treatment of Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: Systematic Review. Cancers 2024, 16, 2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtney Flaherty Biomarker Identification Drives Research and Drug Development in NSCLC and SCLC. Available online: https://www.onclive.com/view/biomarker-identification-drives-research-and-drug-development-in-nsclc-and-sclc (accessed on 11 September 2024).

- Bhullar, K.S.; Lagarón, N.O.; McGowan, E.M.; Parmar, I.; Jha, A.; Hubbard, B.P.; Rupasinghe, H.P.V. Kinase-Targeted Cancer Therapies: Progress, Challenges and Future Directions. Mol. Cancer 2018, 17, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, T. Cytokines and Cytokine Receptors as Targets of Immune-Mediated Inflammatory Diseases—RA as a Role Model. Inflamm. Regen. 2022, 42, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldo, B.A.; Pham, N.H. Targeted Drugs for Cancer Therapy: Small Molecules and Monoclonal Antibodies. In Drug Allergy: Clinical Aspects, Diagnosis, Mechanisms, Structure-Activity Relationships; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 595–644. ISBN 978-3-030-51740-3. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, M.; Li, T.; Niu, M.; Zhang, H.; Wu, Y.; Wu, K.; Dai, Z. Targeting Cytokine and Chemokine Signaling Pathways for Cancer Therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capatina, A.L.; Lagos, D.; Brackenbury, W.J. Targeting Ion Channels for Cancer Treatment: Current Progress and Future Challenges. In Targets of Cancer Diagnosis and Treatment; Reviews of Physiology, Biochemistry and Pharmacology; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 183, pp. 1–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, L.J.; Walker, B.; Irvine, A.E. Proteasome Inhibitors in Cancer Therapy. J. Cell Commun. Signal. 2011, 5, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, H.Y.; Chang, J.-E. Targeted Therapy for Cancers: From Ongoing Clinical Trials to FDA-Approved Drugs. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 13618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Khatib, A.O.; El-Tanani, M.; Al-Obaidi, H. Inhaled Medicines for Targeting Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Wang, W.; Sun, Q. Targeted Drug Approvals in 2023: Breakthroughs by the FDA and NMPA. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullard, A. 2023 FDA Approvals. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2024, 23, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attia, M.F.; Anton, N.; Wallyn, J.; Omran, Z.; Vandamme, T.F. An Overview of Active and Passive Targeting Strategies to Improve the Nanocarriers Efficiency to Tumour Sites. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2019, 71, 1185–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, H.-Y.; Lee, H.-Y. Molecular Targeted Therapy for Anticancer Treatment. Exp. Mol. Med. 2022, 54, 1670–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norsworthy, K.J.; Ko, C.-W.; Lee, J.E.; Liu, J.; John, C.S.; Przepiorka, D.; Farrell, A.T.; Pazdur, R. FDA Approval Summary: Mylotarg for Treatment of Patients with Relapsed or Refractory CD33-Positive Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Oncologist 2018, 23, 1103–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FDA Approves Margetuximab for Metastatic HER2-Positive Breast Cancer. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-margetuximab-metastatic-her2-positive-breast-cancer (accessed on 17 September 2024).

- Artasensi, A.; Pedretti, A.; Vistoli, G.; Fumagalli, L. Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Review of Multi-Target Drugs. Molecules 2020, 25, 1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warshauer, J.T.; Bluestone, J.A.; Anderson, M.S. New Frontiers in the Treatment of Type 1 Diabetes. Cell Metab. 2020, 31, 46–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca-Correa, J.I.; Correa-Rotter, R. Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter 2 Inhibitors Mechanisms of Action: A Review. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 777861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, K.; Chang, J.K.-J.; Chuang, L.-M. Recent Advances in the Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Using New Drug Therapies. Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci. 2024, 40, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FDA. Xolair® (Omalizumab). Highlights of Prescribing Information. 2018. Available online: https://www.gene.com/download/pdf/xolair_prescribing.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- FDA. Nucala® (Mepolizumab). Highlights of Prescribing Information. 2017. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2017/125526s004lbl.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- FDA. Cinqair® (Reslizumab). Highlights of Prescribing Information. 2016. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2016/761033lbl.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- FDA. FasenraTM (Benralizumab). Highlights of Prescribing Information. 2017. Available online: https://www.azpicentral.com/fasenra/fasenra_pi.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- García-Rivero, J.L.; García-Moguel, I. Personalized Medicine in Severe Asthma: Bridging the Gaps. Open Respir. Arch. 2024, 6, 100368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cummings, J.; Salloway, S. Aducanumab: Appropriate Use Recommendations. Alzheimers Dement. 2022, 18, 531–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larkin, H.D. Lecanemab Gains FDA Approval for Early Alzheimer Disease. JAMA 2023, 329, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Personalized Medicine Coalition. Personalized Medicine at FDA: The Scope & Significance of Progress in 2020; The Personalized Medicine Coalition: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- The Personalized Medicine Coalition. Personalized Medicine at FDA: The Scope & Significance of Progress in 2021; The Personalized Medicine Coalition: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- The Personalized Medicine Coalition. PERSONALIZED MEDICINE AT FDA, The Scope & Significance of Progress in 2023; The Personalized Medicine Coalition: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- The Personalized Medicine Coalition. PERSONALIZED MEDICINE AT FDA, The Scope & Significance of Progress in 2024; The Personalized Medicine Coalition: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- WHO Cancer. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/cancer#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- International Agency for Research on Cancer; WHO. New Report on Global Cancer Burden in 2022 by World Region and Human Development Level. Available online: https://www.iarc.who.int/news-events/new-report-on-global-cancer-burden-in-2022-by-world-region-and-human-development-level/ (accessed on 14 September 2024).

- Siegel, R.L.; Giaquinto, A.N.; Jemal, A. Cancer Statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 12–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzyszczyk, P.; Acevedo, A.; Davidoff, E.J.; Timmins, L.M.; Marrero-Berrios, I.; Patel, M.; White, C.; Lowe, C.; Sherba, J.J.; Hartmanshenn, C.; et al. The Growing Role of Precision and Personalized Medicine for Cancer Treatment. Technology 2018, 6, 79–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saini, K.S.; Twelves, C. Determining Lines of Therapy in Patients with Solid Cancers: A Proposed New Systematic and Comprehensive Framework. Br. J. Cancer 2021, 125, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jemal, A.; Thun, M.J.; Ries, L.A.G.; Howe, H.L.; Weir, H.K.; Center, M.M.; Ward, E.; Wu, X.-C.; Eheman, C.; Anderson, R.; et al. Annual Report to the Nation on the Status of Cancer, 1975-2005, Featuring Trends in Lung Cancer, Tobacco Use, and Tobacco Control. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2008, 100, 1672–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Usborne, C.M.; Mullard, A.P. A Review of Systemic Anticancer Therapy in Disease Palliation. Br. Med. Bull. 2017, 125, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lind, M.J. Principles of Systemic Anticancer Therapy. Medicine 2016, 44, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R. Cytotoxic Chemotherapy: Clinical Aspects. Medicine 2016, 44, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, X.; Shen, L. Molecular Targeted Therapy of Cancer: The Progress and Future Prospect. Front. Lab. Med. 2017, 1, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, L.; Li, Y.; Xiong, L.; Wang, W.; Wu, M.; Yuan, T.; Yang, W.; Tian, C.; Miao, Z.; Wang, T.; et al. Small Molecules in Targeted Cancer Therapy: Advances, Challenges, and Future Perspectives. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majeed, H.; Gupta, V. Adverse Effects of Radiation Therapy; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Chemotherapy Side Effects. American Cancer Society. Available online: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/managing-cancer/treatment-types/chemotherapy/chemotherapy-side-effects.html (accessed on 14 September 2024).

- Jain, K.K. Cancer Biomarkers: Current Issues and Future Directions. Curr. Opin. Mol. Ther. 2007, 9, 563–571. [Google Scholar]

- Mateo, J.; Steuten, L.; Aftimos, P.; André, F.; Davies, M.; Garralda, E.; Geissler, J.; Husereau, D.; Martinez-Lopez, I.; Normanno, N.; et al. Delivering Precision Oncology to Patients with Cancer. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 658–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greulich, H.; Chen, T.-H.; Feng, W.; Jänne, P.A.; Alvarez, J.V.; Zappaterra, M.; Bulmer, S.E.; Frank, D.A.; Hahn, W.C.; Sellers, W.R.; et al. Oncogenic Transformation by Inhibitor-Sensitive and -Resistant EGFR Mutants. PLoS Med. 2005, 2, e313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halliday, P.R.; Blakely, C.M.; Bivona, T.G. Emerging Targeted Therapies for the Treatment of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2019, 21, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamalinia, M.; Weiskirchen, R. Advances in Personalized Medicine: Translating Genomic Insights into Targeted Therapies for Cancer Treatment. Ann. Transl. Med. 2025, 13, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Food and Drug Administration. Prescribing Information; US Food and Drug administration: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Blackwell, K.; Gligorov, J.; Jacobs, I.; Twelves, C. The Global Need for a Trastuzumab Biosimilar for Patients with HER2-Positive Breast Cancer. Clin. Breast Cancer 2018, 18, 95–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bethune, G.; Bethune, D.; Ridgway, N.; Xu, Z. Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR) in Lung Cancer: An Overview and Update. J. Thorac. Dis. 2010, 2, 48–51. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Recondo, G.; Facchinetti, F.; Olaussen, K.A.; Besse, B.; Friboulet, L. Making the First Move in EGFR-Driven or ALK-Driven NSCLC: First-Generation or next-Generation TKI? Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 15, 694–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proietti, I.; Skroza, N.; Michelini, S.; Mambrin, A.; Balduzzi, V.; Bernardini, N.; Marchesiello, A.; Tolino, E.; Volpe, S.; Maddalena, P.; et al. BRAF Inhibitors: Molecular Targeting and Immunomodulatory Actions. Cancers 2020, 12, 1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babamohamadi, M.; Mohammadi, N.; Faryadi, E.; Haddadi, M.; Merati, A.; Ghobadinezhad, F.; Amirian, R.; Izadi, Z.; Hadjati, J. Anti-CTLA-4 Nanobody as a Promising Approach in Cancer Immunotherapy. Cell Death Dis. 2024, 15, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Y.; Liu, D.; Li, L. PD-1/PD-L1 Pathway: Current Researches in Cancer. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2020, 10, 727–742. [Google Scholar]

- Manning, G.; Whyte, D.B.; Martinez, R.; Hunter, T.; Sudarsanam, S. The Protein Kinase Complement of the Human Genome. Science 2002, 298, 1912–1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, N.; Singh, A.; Kumar, P.; Kaushik, M. Protein Kinases: Role of Their Dysregulation in Carcinogenesis, Identification and Inhibition. Drug Res. 2023, 73, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roskoski, R. Classification of Small Molecule Protein Kinase Inhibitors Based upon the Structures of Their Drug-Enzyme Complexes. Pharmacol. Res. 2016, 103, 26–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhillon, S. Gefitinib: A Review of Its Use in Adults with Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Target. Oncol. 2015, 10, 153–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Gray, N.S. Rational Design of Inhibitors That Bind to Inactive Kinase Conformations. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2006, 2, 358–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kufareva, I.; Abagyan, R. Type-II Kinase Inhibitor Docking, Screening, and Profiling Using Modified Structures of Active Kinase States. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 51, 7921–7932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Will, Y.; Dykens, J.A.; Nadanaciva, S.; Hirakawa, B.; Jamieson, J.; Marroquin, L.D.; Hynes, J.; Patyna, S.; Jessen, B.A. Effect of the Multitargeted Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors Imatinib, Dasatinib, Sunitinib, and Sorafenib on Mitochondrial Function in Isolated Rat Heart Mitochondria and H9c2 Cells. Toxicol. Sci. 2008, 106, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamba, V.; Ghosh, I. New Directions in Targeting Protein Kinases: Focusing Upon True Allosteric and Bivalent Inhibitors. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2012, 18, 2936–2945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okamoto, K.; Ikemori-Kawada, M.; Jestel, A.; von König, K.; Funahashi, Y.; Matsushima, T.; Tsuruoka, A.; Inoue, A.; Matsui, J. Distinct Binding Mode of Multikinase Inhibitor Lenvatinib Revealed by Biochemical Characterization. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2015, 6, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.-S.; Yang, G.-J.; Cai, Y.; Li, J.-L.; Xu, H.-Y.; Zhang, T.; Zhou, L.-Q.; Wang, Y.-Y.; Wang, J.-L.; Hu, X.-S.; et al. Dacomitinib for Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Patients Harboring Major Uncommon EGFR Alterations: A Dual-Center, Single-Arm, Ambispective Cohort Study in China. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 919652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imai, K.; Takaoka, A. Comparing Antibody and Small-Molecule Therapies for Cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2006, 6, 714–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dancey, J.; Sausville, E.A. Issues and Progress with Protein Kinase Inhibitors for Cancer Treatment. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2003, 2, 296–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Druker, B.J. STI571 (Gleevec) as a Paradigm for Cancer Therapy. Trends Mol. Med. 2002, 8, S14–S18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Druker, B.J. Imatinib as a Paradigm of Targeted Therapies. Adv. Cancer Res. 2004, 91, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.; Zhou, H.; Tan, L.; Siu, K.T.H.; Guan, X.-Y. Exploring Treatment Options in Cancer: Tumor Treatment Strategies. Signal. Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zahavi, D.; Weiner, L. Monoclonal Antibodies in Cancer Therapy. Antibodies 2020, 9, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keating, G.M. Rituximab: A Review of Its Use in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukaemia, Low-Grade or Follicular Lymphoma and Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. Drugs 2010, 70, 1445–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Schmitz, K.R.; Jeffrey, P.D.; Wiltzius, J.J.W.; Kussie, P.; Ferguson, K.M. Structural Basis for Inhibition of the Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor by Cetuximab. Cancer Cell 2005, 7, 301–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, D.; Bassi, R.; Hooper, A.; Prewett, M.; Hicklin, D.J.; Kang, X. Anti-Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Monoclonal Antibody Cetuximab Inhibits EGFR/HER-2 Heterodimerization and Activation. Int. J. Oncol. 2009, 34, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chames, P.; Van Regenmortel, M.; Weiss, E.; Baty, D. Therapeutic Antibodies: Successes, Limitations and Hopes for the Future. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2009, 157, 220–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Nava, C.; Ortuño-Pineda, C.; Illades-Aguiar, B.; Flores-Alfaro, E.; Leyva-Vázquez, M.A.; Parra-Rojas, I.; Del Moral-Hernández, O.; Vences-Velázquez, A.; Cortés-Sarabia, K.; Alarcón-Romero, L.D.C. Mechanisms of Action and Limitations of Monoclonal Antibodies and Single Chain Fragment Variable (scFv) in the Treatment of Cancer. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovacik, M.; Lin, K. Tutorial on Monoclonal Antibody Pharmacokinetics and Its Considerations in Early Development. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2018, 11, 540–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sievers, E.L.; Senter, P.D. Antibody-Drug Conjugates in Cancer Therapy. Annu. Rev. Med. 2013, 64, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.; Li, S.; Han, S.; Shi, C.; Zhang, Y. Antibody Drug Conjugate: The “Biological Missile” for Targeted Cancer Therapy. Signal. Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.H.; Jeong, M.; In, H.; Kim, J.H.; Lin, C.-W.; Han, K.H. Trends in the Development of Antibody-Drug Conjugates for Cancer Therapy. Antibodies 2023, 12, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lukyanov, A.N.; Elbayoumi, T.A.; Chakilam, A.R.; Torchilin, V.P. Tumor-Targeted Liposomes: Doxorubicin-Loaded Long-Circulating Liposomes Modified with Anti-Cancer Antibody. J. Control. Release 2004, 100, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munster, P.; Krop, I.E.; LoRusso, P.; Ma, C.; Siegel, B.A.; Shields, A.F.; Molnár, I.; Wickham, T.J.; Reynolds, J.; Campbell, K.; et al. Safety and Pharmacokinetics of MM-302, a HER2-Targeted Antibody-Liposomal Doxorubicin Conjugate, in Patients with Advanced HER2-Positive Breast Cancer: A Phase 1 Dose-Escalation Study. Br. J. Cancer 2018, 119, 1086–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diabetes. World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/diabetes (accessed on 14 September 2024).

- Demir, S.; Nawroth, P.P.; Herzig, S.; Ekim Üstünel, B. Emerging Targets in Type 2 Diabetes and Diabetic Complications. Adv. Sci. 2021, 8, e2100275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, P.J.; Goodwin Cartwright, B.M.; Gratzl, S.; Brar, R.; Baker, C.; Gluckman, T.J.; Stucky, N.L. Semaglutide vs Tirzepatide for Weight Loss in Adults with Overweight or Obesity. JAMA Intern. Med. 2024, 184, 1056–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulvihill, E.E.; Drucker, D.J. Pharmacology, Physiology, and Mechanisms of Action of Dipeptidyl Peptidase-4 Inhibitors. Endocr. Rev. 2014, 35, 992–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.; Luo, Y.; Hu, S.; Tang, L.; Ouyang, S. Advances in Research on Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Targets and Therapeutic Agents. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 13381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.M.; Jones, H.; Stephens, J.W. Personalized Type 2 Diabetes Management: An Update on Recent Advances and Recommendations. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2022, 15, 281–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugandh, F.; Chandio, M.; Raveena, F.; Kumar, L.; Karishma, F.; Khuwaja, S.; Memon, U.A.; Bai, K.; Kashif, M.; Varrassi, G.; et al. Advances in the Management of Diabetes Mellitus: A Focus on Personalized Medicine. Cureus 2023, 15, e43697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klonoff, D.C. Precision Medicine for Managing Diabetes. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2015, 9, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fireman, P. Understanding Asthma Pathophysiology. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2003, 24, 79–83. [Google Scholar]

- Holgate, S.T.; Wenzel, S.; Postma, D.S.; Weiss, S.T.; Renz, H.; Sly, P.D. Asthma. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2015, 1, 15025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agache, I.; Adcock, I.M.; Baraldi, F.; Chung, K.F.; Eguiluz-Gracia, I.; Johnston, S.L.; Jutel, M.; Nair, P.; Papi, A.; Porsbjerg, C.; et al. Personalized Therapeutic Approaches for Asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2025, 156, 503–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuruvilla, M.E.; Lee, F.E.-H.; Lee, G.B. Understanding Asthma Phenotypes, Endotypes, and Mechanisms of Disease. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2019, 56, 219–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, A.; Kolls, J.K. Neutrophilic Inflammation in Asthma and Association with Disease Severity. Trends Immunol. 2017, 38, 942–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambrecht, B.N.; Hammad, H. The Immunology of Asthma. Nat. Immunol. 2015, 16, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froidure, A.; Mouthuy, J.; Durham, S.R.; Chanez, P.; Sibille, Y.; Pilette, C. Asthma Phenotypes and IgE Responses. Eur. Respir. J. 2016, 47, 304–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelaia, G.; Vatrella, A.; Busceti, M.T.; Gallelli, L.; Terracciano, R.; Maselli, R. Anti-IgE Therapy with Omalizumab for Severe Asthma: Current Concepts and Potential Developments. Curr. Drug Targets 2015, 16, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calhoun, W.J.; Chupp, G.L. The New Era of Add-on Asthma Treatments: Where Do We Stand? Allergy Asthma Clin. Immunol. 2022, 18, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Top 10 Causes of Death in United States of America for Total Aged Total Years. 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/mortality-and-global-health-estimates/ghe-leading-causes-of-death (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- Song, L.; Jia, K.; Yang, F.; Wang, J. Advanced Nanomedicine Approaches for Myocardial Infarction Treatment. Int. J. Nanomed. 2024, 19, 6399–6425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Wang, L.; Wang, S.; Cheng, H.; Xu, L.; Pei, G.; Wang, Y.; Fu, C.; Jiang, Y.; He, C.; et al. Signaling Pathways and Targeted Therapy for Myocardial Infarction. Signal. Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awada, H.K.; Hwang, M.P.; Wang, Y. Towards Comprehensive Cardiac Repair and Regeneration after Myocardial Infarction: Aspects to Consider and Proteins to Deliver. Biomaterials 2016, 82, 94–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobo, D.; Robinson, K.J.; Islam, J.; Thurecht, K.J.; Corrie, S.R. Nanoparticle-Based Medicines: A Review of FDA-Approved Materials and Clinical Trials to Date. Pharm. Res. 2016, 33, 2373–2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicha, I.; Chauvierre, C.; Texier, I.; Cabella, C.; Metselaar, J.M.; Szebeni, J.; Dézsi, L.; Alexiou, C.; Rouzet, F.; Storm, G.; et al. From Design to the Clinic: Practical Guidelines for Translating Cardiovascular Nanomedicine. Cardiovasc. Res. 2018, 114, 1714–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, A.S.-R.; Dinesh, V.; Pang, N.Y.-L.; Dinesh, T.; Pang, K.Y.-L.; Yip, G.W.; Bay, B.H.; Srinivasan, D.K. Precision Medicine in Myocardial Infarction: Nanotheranostic Strategies. Nano Select 2024, 5, 2300127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, T.A.; Hsu, C.-C.; Meeson, A.; Lundy, D.J. Nanocarrier-Based Targeted Therapies for Myocardial Infarction. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Y.; Wang, H.; Weng, X.; Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Shen, J.; Zhao, W.; Xi, Q.; Zhang, H.; Fu, Z. Supramolecular Self-Assembled Nanoparticles for Targeted Therapy of Myocardial Infarction by Enhancing Cardiomyocyte Mitophagy. Aggregate 2024, 5, e563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoso, M.R.; Yang, P.C. Magnetic Nanoparticles for Targeting and Imaging of Stem Cells in Myocardial Infarction. Stem Cells Int. 2016, 2016, 4198790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, P.K.; Lan, F.; Wang, Y.; Wu, J.C. Imaging: Guiding the Clinical Translation of Cardiac Stem Cell Therapy. Circ. Res. 2011, 109, 962–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, J.M.; Dick, A.J.; Raman, V.K.; Thompson, R.B.; Yu, Z.-X.; Hinds, K.A.; Pessanha, B.S.S.; Guttman, M.A.; Varney, T.R.; Martin, B.J.; et al. Serial Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging of Injected Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Circulation 2003, 108, 1009–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Najahi-Missaoui, W.; Arnold, R.D.; Cummings, B.S. Safe Nanoparticles: Are We There Yet? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 22, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farokhzad, O.C.; Langer, R. Nanomedicine: Developing Smarter Therapeutic and Diagnostic Modalities. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2006, 58, 1456–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, X.Y.; Sena-Torralba, A.; Álvarez-Diduk, R.; Muthoosamy, K.; Merkoçi, A. Nanomaterials for Nanotheranostics: Tuning Their Properties According to Disease Needs. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 2585–2627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitragotri, S.; Anderson, D.G.; Chen, X.; Chow, E.K.; Ho, D.; Kabanov, A.V.; Karp, J.M.; Kataoka, K.; Mirkin, C.A.; Petrosko, S.H.; et al. Accelerating the Translation of Nanomaterials in Biomedicine. ACS Nano 2015, 9, 6644–6654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madamsetty, V.S.; Mukherjee, A.; Mukherjee, S. Recent Trends of the Bio-Inspired Nanoparticles in Cancer Theranostics. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saludas, L.; Oliveira, C.C.; Roncal, C.; Ruiz-Villalba, A.; Prósper, F.; Garbayo, E.; Blanco-Prieto, M.J. Extracellular Vesicle-Based Therapeutics for Heart Repair. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma-Chavez, J.A.; Fuentes, K.; Applegate, B.E.; Jo, J.A.; Charoenphol, P. Development and Characterization of PLGA-Based Multistage Delivery System for Enhanced Payload Delivery to Targeted Vascular Endothelium. Macromol. Biosci. 2021, 21, e2000377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, B.; Liu, S.; Hao, R.; Dong, X.; Fu, L.; Han, B. RGD-PEG-PLA Delivers MiR-133 to Infarct Lesions of Acute Myocardial Infarction Model Rats for Cardiac Protection. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Gu, C.; Cabigas, E.B.; Pendergrass, K.D.; Brown, M.E.; Luo, Y.; Davis, M.E. Functionalized Dendrimer-Based Delivery of Angiotensin Type 1 Receptor siRNA for Preserving Cardiac Function Following Infarction. Biomaterials 2013, 34, 3729–3736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margulis, K.; Neofytou, E.A.; Beygui, R.E.; Zare, R.N. Celecoxib Nanoparticles for Therapeutic Angiogenesis. ACS Nano 2015, 9, 9416–9426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yvan-Charvet, L.; Pagler, T.; Gautier, E.L.; Avagyan, S.; Siry, R.L.; Han, S.; Welch, C.L.; Wang, N.; Randolph, G.J.; Snoeck, H.W.; et al. ATP-Binding Cassette Transporters and HDL Suppress Hematopoietic Stem Cell Proliferation. Science 2010, 328, 1689–1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Garg, T.; Goyal, A.K.; Rath, G. Recent Advancements in the Cardiovascular Drug Carriers. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2016, 44, 216–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Al Zaki, A.; Hui, J.Z.; Muzykantov, V.R.; Tsourkas, A. Multifunctional Nanoparticles: Cost versus Benefit of Adding Targeting and Imaging Capabilities. Science 2012, 338, 903–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Board, C.; Kelly, M.S.; Shapiro, M.D.; Dixon, D.L. PCSK9 Inhibitors in Secondary Prevention-An Opportunity for Personalized Therapy. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2020, 75, 410–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FDA Approves New Treatment for a Type of Heart Failure. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20200507031954/http://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-new-treatment-type-heart-failure (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- Cataldi, R.; Sachdev, P.S.; Chowdhary, N.; Seeher, K.; Bentvelzen, A.; Moorthy, V.; Dua, T. A WHO Blueprint for Action to Reshape Dementia Research. Nat. Aging 2023, 3, 469–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Xia, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chen, L. Recent Advances in Alzheimer’s Disease: Mechanisms, Clinical Trials and New Drug Development Strategies. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 2023 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2023, 19, 1598–1695. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Querfurth, H.W.; LaFerla, F.M. Alzheimer’s Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 362, 329–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelnour, C.; Agosta, F.; Bozzali, M.; Fougère, B.; Iwata, A.; Nilforooshan, R.; Takada, L.T.; Viñuela, F.; Traber, M. Perspectives and Challenges in Patient Stratification in Alzheimer’s Disease. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2022, 14, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cummings, J. New Approaches to Symptomatic Treatments for Alzheimer’s Disease. Mol. Neurodegener. 2021, 16, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arafah, A.; Khatoon, S.; Rasool, I.; Khan, A.; Rather, M.A.; Abujabal, K.A.; Faqih, Y.A.H.; Rashid, H.; Rashid, S.M.; Bilal Ahmad, S.; et al. The Future of Precision Medicine in the Cure of Alzheimer’s Disease. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhillon, S. Aducanumab: First Approval. Drugs 2021, 81, 1437–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dyck, C.H.; Swanson, C.J.; Aisen, P.; Bateman, R.J.; Chen, C.; Gee, M.; Kanekiyo, M.; Li, D.; Reyderman, L.; Cohen, S.; et al. Lecanemab in Early Alzheimer’s Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panghal, A.; Flora, S.J.S. Nanotechnology in the Diagnostic and Therapy for Alzheimer’s Disease. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta (BBA) Gen. Subj. 2024, 1868, 130559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griñán-Ferré, C.; Bellver-Sanchis, A.; Guerrero, A.; Pallàs, M. Advancing Personalized Medicine in Neurodegenerative Diseases: The Role of Epigenetics and Pharmacoepigenomics in Pharmacotherapy. Pharmacol. Res. 2024, 205, 107247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Xia, Y.; Gui, Y. Neuronal ApoE4 in Alzheimer’s Disease and Potential Therapeutic Targets. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2023, 15, 1199434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhuri, K.; Bechtold, C.; Quijano, E.; Pham, H.; Gupta, A.; Vikram, A.; Bahal, R. Antisense Oligonucleotides: An Emerging Area in Drug Discovery and Development. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.-T.; Wan, C.; Yang, W.; Cai, Z. Role of Cdk5 in Amyloid-Beta Pathology of Alzheimer’s Disease. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2019, 16, 1206–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Fang, L.; Kool, E.T. RNA Infrastructure Profiling Illuminates Transcriptome Structure in Crowded Spaces. Cell Chem. Biol. 2024, 31, 2156–2167.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampel, H.; Vassar, R.; De Strooper, B.; Hardy, J.; Willem, M.; Singh, N.; Zhou, J.; Yan, R.; Vanmechelen, E.; De Vos, A.; et al. The β-Secretase BACE1 in Alzheimer’s Disease. Biol. Psychiatry 2021, 89, 745–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.K.; Osswald, H.L. BACE1 (β-Secretase) Inhibitors for the Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 6765–6813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, W.; Yang, H.; Yang, J. Small-Molecule Drugs Development for Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 1019412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira-Vieira, T.H.; Guimaraes, I.M.; Silva, F.R.; Ribeiro, F.M. Alzheimer’s Disease: Targeting the Cholinergic System. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2016, 14, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, H.; Uras, G.; Zhang, P.; Xu, S.; Yin, Y.; Liu, J.; Qin, S.; Li, X.; Allen, S.; Bai, R.; et al. Discovery of Novel Tacrine–Pyrimidone Hybrids as Potent Dual AChE/GSK-3 Inhibitors for the Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 64, 7483–7506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abushakra, S.; Porsteinsson, A.P.; Sabbagh, M.; Watson, D.; Power, A.; Liang, E.; MacSweeney, E.; Boada, M.; Flint, S.; McLaine, R.; et al. APOLLOE4 Phase 3 Study of Oral ALZ-801/Valiltramiprosate in APOE Ε4/Ε4 Homozygotes with Early Alzheimer’s Disease: Trial Design and Baseline Characteristics. Alzheimer’s Dement. Transl. Res. Clin. Interv. 2024, 10, e12498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabbagh, M.N.; Chezem, W.R.; Jin, K.; Missling, C.U. Anavex Life Sciences Research Group Blarcamesine in Early Alzheimer Disease Phase 2b/3 Randomized Clinical Trial. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2024, 20, e090729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Dong, M.; Sun, Y.; Duan, X.; Niu, W. Effectiveness and Safety of Monoclonal Antibodies against Amyloid-Beta Vis-à-Vis Placebo in Mild or Moderate Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Neurol. 2023, 14, 1147757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salloway, S.; Sperling, R.; Fox, N.C.; Blennow, K.; Klunk, W.; Raskind, M.; Sabbagh, M.; Honig, L.S.; Porsteinsson, A.P.; Ferris, S.; et al. Two Phase 3 Trials of Bapineuzumab in Mild-to-Moderate Alzheimer’s Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 370, 322–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, M.; Chu, F.; Zhu, F.; Zhu, J. Impact of Anti-Amyloid-β Monoclonal Antibodies on the Pathology and Clinical Profile of Alzheimer’s Disease: A Focus on Aducanumab and Lecanemab. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 870517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, S.; Van Dyck, C.H.; Gee, M.; Doherty, T.; Kanekiyo, M.; Dhadda, S.; Li, D.; Hersch, S.; Irizarry, M.; Kramer, L.D. Lecanemab Clarity AD: Quality-of-Life Results from a Randomized, Double-Blind Phase 3 Trial in Early Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Prev. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2023, 10, 771–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.; Han, M.; Jeon, S.; Kim, Y.; Choi, H.J.; Choi, W.; Kwon, K.; Choi, J.; Lee, E.-H. Aducanumab Delivery via Focused Ultrasound-Induced Transient Blood–Brain Barrier Opening in Vivo. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 17742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezai, A.R.; D’Haese, P.-F.; Finomore, V.; Carpenter, J.; Ranjan, M.; Wilhelmsen, K.; Mehta, R.I.; Wang, P.; Najib, U.; Vieira Ligo Teixeira, C.; et al. Ultrasound Blood–Brain Barrier Opening and Aducanumab in Alzheimer’s Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 390, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauwels, E.K.J.; Boer, G.J. Alzheimer’s Disease: A Suitable Case for Treatment with Precision Medicine? Med. Princ. Pract. 2024, 33, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantinidis, E.; Molisak, A.; Perrin, F.; Streubel-Gallasch, L.; Fayad, S.; Kim, D.Y.; Petri, K.; Aryee, M.J.; Aguilar, X.; György, B.; et al. CRISPR-Cas9 Treatment Partially Restores Amyloid-β 42/40 in Human Fibroblasts with the Alzheimer’s Disease PSEN1 M146L Mutation. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2022, 28, 450–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guyon, A.; Rousseau, J.; Bégin, F.-G.; Bertin, T.; Lamothe, G.; Tremblay, J.P. Base Editing Strategy for Insertion of the A673T Mutation in the APP Gene to Prevent the Development of AD in Vitro. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2021, 24, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Intervention | Therapeutic Strategy | Clinical Trial ID | Molecular Markers/Signal Pathways |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ivabradine | Drug (I(f) Current Inhibitors) | NCT05279651 (Phase III) | PI3K/Akt/mTOR |

| Rapamycin/Sirolimus | Drug (Immunosuppressants) | NCT00288210 (Phase IV) | mTOR |

| Losmapimod | Drug (p38 MAPK) | NCT02145468 (Phase III) | MAPK |

| Canakinumab | Drug (Monoclonal Antibodies-Anti-inflammatory) | NCT01327846 (Phase III) | NLRP3/IL-1β |

| Colchicine | Drug (Anti-inflammatory) | NCT04420624 (Phase II, III) | NLRP3/IL-1β |

| Erythropoietin | Drug (Cardioprotective) | NCT00367991 | MAPK, TGF-β, Wnt, Sonic Hedgehog |

| Estradiol | Drug (vasodilation, improved Endothelial function and Anti-atherosclerotic) | NCT00377988 (observational) | RhoA/ROCK |

| Estrogen | Drug (vasodilation, improved Endothelial function and Anti-atherosclerotic) | NCT00005185 (Observational) | RhoA/ROCK |

| Nicorandil | Drug (anti-free radical and neutrophil modulating, vasodilatation) | NCT02449070 (Phase III) | RhoA/ROCK |

| Dexmedetomidine | Drug (anti-inflammatory) | NCT04912518 (NA) | RhoA/ROCK |

| Valsartan | Drug (Angiotensin II receptor blockers-ARBs) | NCT01340326 (Phase IV) | TGF-β/SMADs |

| Sildenafil | Drug (Vasodialtor) | NCT01046838 (Phase IV) | JAK2/STAT3, RhoA/ROCK |

| G-Csf | Drug (Cardioprotective) | NCT00756756 (NA) | JAK2/STAT3, NF-κB |

| Methotrexate | Drug (beneficial effects on vascular homeostasis and blood pressure control) | NCT01741558 (Phase II) | NF-κB |

| Metformin | Drug (Reduces LDL C) | NCT05182970 (Phase III) | TLR4 |

| Melatonin | Drug (reduces mitochondrial dysfunction) | NCT03230630 (observational) | Notch, Hippo/YAP |

| Fasudil | Drug (reduced myocardial infarct size-preclinical) | NCT03753269 (Phase IV) | TGFβ1/TAK1, TGF-β2, TGF-β3, RhoA/ROCK |

| Statin | Drug (anti-inflammatory and antithrombotic, and antioxidant effects) | NCT01205347 (Phase IV) | PI3K/Akt/FOXO3a, TGF-β/SMADs, Sonic Hedgehog, RhoA/ROCK/ERK, PI3K/Akt/Nrf2/HO-1 |

| Hirudin | Drug (antithrombotic) | NCT05847205 (Phase IV) | KEAP1/Nrf2/HO-1 |

| Vegf-A165 Plasmid | Gene Therapy | NCT00620217 (Phase II) | VEGF/PI3K/Akt |

| Adgvvegf121 Cdna | Gene Therapy | NCT01174095 (observational) | VEGF/PI3K/Akt |

| Endocardial Adenovirus Vegf-D Gene Transfer | Gene Therapy | NCT01002430 (Phase I) | VEGF/PI3K/Akt |

| Bicistronic Vegf-A165/Bfgf Plasmid | Gene Therapy | NCT00620217 (Phase II) | VEGF(bFGF)/PI3K/Akt |

| Cd34+ Cell | Cell Therapy | NCT00313339 (Phase I) | PI3K/Akt, Sonic Hedgehog |

| Cd133+ Cell | Cell Therapy | NCT00529932 | PI3K/Akt, Wnt |

| Epcs | Cell Therapy | NCT00936819 (Phase II) | VEGF/PI3K/Akt/eNOS, Dll4/Notch/Hey2, Sonic Hedgehog, Akt/HO-1 |

| Mscs | Cell Therapy | NCT05043610 (Phase III) | PI3K/Akt/mTOR, Wnt/β-catenin, TGF-β/SMADs, Notch, Sonic Hedgehog |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rongala, G.; Rongala, D.S.; Rongala, A.N. The Future of Precision Medicine: Targeted Therapies, Personalized Medicine and Formulation Strategies. J. Pharm. BioTech Ind. 2025, 2, 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpbi2040019

Rongala G, Rongala DS, Rongala AN. The Future of Precision Medicine: Targeted Therapies, Personalized Medicine and Formulation Strategies. Journal of Pharmaceutical and BioTech Industry. 2025; 2(4):19. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpbi2040019

Chicago/Turabian StyleRongala, Gopinath, Druva Sarika Rongala, and Appalaswamy Naidu Rongala. 2025. "The Future of Precision Medicine: Targeted Therapies, Personalized Medicine and Formulation Strategies" Journal of Pharmaceutical and BioTech Industry 2, no. 4: 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpbi2040019

APA StyleRongala, G., Rongala, D. S., & Rongala, A. N. (2025). The Future of Precision Medicine: Targeted Therapies, Personalized Medicine and Formulation Strategies. Journal of Pharmaceutical and BioTech Industry, 2(4), 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpbi2040019