Abstract

In recent years, requests for animal-assisted interventions (AAI) from medical institutions and welfare facilities have increased. Dogs are the most commonly used animals in AAI. Dogs that pass the “therapy dog” aptitude test can work in AAI. In previous research, we identified the Canine Behavior Assessment and Research Questionnaire (C-BARQ) factors common among dogs that passed the aptitude test. Using these factors, we developed the TC-BARQ, a screening questionnaire for therapy dogs that included 51 C-BARQ surveys. In this study, we conducted TC-BARQ screenings and compared the characteristics of dogs that passed and failed the aptitude test. We collected TC-BARQ data points from aptitude test examinees of the local AAI Dog Association. Each dog is identified by its breed, sex, neutering status, and whether it lives with another dog at home. For each question, we identified factors that differed between dogs that passed and those that failed. As a result, differences emerged in the presence of family dogs, particularly in behaviors related to aggression toward strangers and other dogs, as well as excitability toward people and situations. Continued surveillance is essential, but this study provides important information on selecting “therapy dogs”.

1. Introduction

Humans have long valued dogs, and interactions with them have been shown to have positive psychological and physical benefits for people [1]. Recently, this effect has been scientifically confirmed in various animals, increasing awareness of animal-assisted therapy [1]. Interactions with dogs, in particular, play a role in improving the quality of life (QOL) for individuals in medical and welfare settings, such as hospitals and nursing homes. Although different animals, including horses and dolphins, have been used in animal-assisted interventions, dogs have become the most common in recent years [2,3,4]. The reported benefits of animal-assisted intervention include reductions in depressive symptoms [2,5] and increased motivation to engage with society [4,6,7]. To support these benefits, many hospitals and facilities have introduced therapy dog visits. As demand increases, the number of therapy dogs now exceeds the available supply. Animal-assisted intervention can be divided into three types based on approach [8]. The first is animal-assisted therapy (AAT), the second is animal-assisted education (AAE), and the third is animal-assisted activities (AAA). Most animal-assisted interventions in Japan are of the AAA type, with AAT being uncommon.

In Japan, the adoption of AAI in hospitals and elderly care facilities remains limited [9]. One reason for this is that, in Japan, it is customary to take off one’s shoes before entering a home, and bringing barefoot dogs into homes has yet to become a common practice. Furthermore, Japanese people have strict hygiene standards and are reluctant to allow unwashed dogs into places where cleanliness is particularly important, such as hospitals. Second, because therapy dogs are not covered by health insurance, sufficient funding is not available when the dog handlers participate in AAI. Meanwhile, research by Suzuki and Sakuramoto [10] estimated that increasing the use of therapy dogs in Japanese hospitals could result in medical cost savings of more than 100 billion yen. Therefore, if national and local governments could support therapy dog activities, demand is likely to increase significantly. However, since there is no government agency overseeing therapy dogs in Japan, each therapy dog organization operates independently, modeled after animal-assisted interventions in the United States and other countries. Therefore, it is difficult to accurately determine the number of therapy dogs and handlers active in Japan. According to internet searches and interviews, the total number of therapy dogs operated by eight well-known organizations in Japan is approximately 500. Therefore, at the very least, it is estimated that there are fewer than 600 active therapy dogs. It is estimated that approximately 6.8 million dogs are kept in Japanese households [11]. In other words, there is still room for increasing the use of therapy dogs, and to popularize this approach, it is urgent to introduce more efficient methods for finding suitable dogs.

Although there are no legal qualifications for therapy dogs in Japan, certified dogs and their handlers are actively involved in the field. For example, the Hokkaido Volunteer Dog Association requires that dogs pass the “Therapy Dog Aptitude Test” [12]. This test is designed to ensure safe and stress-free interactions for both people and animals. The association conducts aptitude tests that evaluate a dog’s reactions to physical contact with other dogs or people, loud noises, and the appearance of a wheelchair, as well as its obedience to commands such as sitting and walking beside its owner. If a dog barks, engages in dangerous behavior, or urinates or defecates during the test, it is immediately disqualified. While passing these tests is considered a sign of a therapy dog, the specific personality traits that are important remain unclear.

Sakurama et al. [13] used a dog personality assessment tool called the C-BARQ (Canine Behavioral Assessment Questionnaire) to identify the characteristics of dogs that pass therapy dog tests. The C-BARQ was developed in 2003 by a team of researchers from the University of Pennsylvania, led by Dr. Serpell, and has been used extensively in behavioral studies as an indicator of canine personality [14]. It consists of 101 items divided into 13 categories: stranger-directed aggression, owner-directed aggression, dog-directed aggression/fear, trainability, chasing, stranger-directed fear, nonsocial fear, dog-directed fear, separation-related behavior, touch sensitivity, excitability, attachment/attention-seeking, and energy level. The C-BARQ, widely used as an online tool for owners to evaluate their dog’s personality, has also been applied internationally in therapy dog assessments [15,16]. In a 2020 study, Sakurama et al. conducted two C-BARQ surveys on dogs that passed the Therapy Dog Aptitude Test administered by the Hokkaido Volunteer Dog Association, identifying 14 factors related to therapy dog suitability. These factors included (1) trainability and obedience, (2) separation-related anxiety behaviors, (3) separation-related physiological reactions, (4) aggression towards people, (5) fear or anxiety towards strangers, dogs, or unfamiliar situations, (6) territorial aggression, (7) hyperactivity, (8) aggression towards approaching unknown dogs, (9) resource guarding-related aggression, (10) abnormal behaviors, (11) excitability, (12) attachment behaviors to family members, (13) vigilant aggression towards family dogs, and (14) resource guarding-related aggression toward family dogs. Sakurama et al. [13] also rated the suitability of 14 canine personality traits for therapy dogs on a four-point scale (Low, Mild, Moderate, High). They indicated that “High” levels are desirable for trainability and obedience, “Mild to Moderate” for attachment behavior to family members, “Mild” for excitability, and “Low” for all other traits.

The Hokkaido Volunteer Dog Association’s aptitude test is only held twice a year, and most dog owners are unfamiliar with it. To encourage more dogs to become therapy dogs, we need to increase the number of participants in our testing program. A pre-therapy dog aptitude test, such as a questionnaire that owners can easily complete at home, would be helpful. Although the C-BARQ has shown potential as a valuable tool to identify dogs with the right traits for therapy work, the questionnaire still involves many questions, making it less practical as a quick screening tool. In this study, we developed the TC-BARQ (C-BARQ for therapy dogs) based on the personality traits required for therapy dogs, as identified by Sakurama et al. [13]. Furthermore, we compared the differences in personality traits between dogs that passed and failed using TC-BARQ to find the key traits of therapy dogs.

2. Materials and Methods

With support from the Hokkaido Volunteer Dog Association (Hokkaido, Japan), a survey was carried out focusing on dogs that had passed the Therapy Dog Aptitude Test. Founded in 1996, the Hokkaido Volunteer Dog Association is a nonprofit organization that provides AAA services at medical facilities and welfare centers throughout Hokkaido (URL: www.volunteer-dog.com). Among the 100 dogs taking the aptitude test, 69 passed, and 31 failed. The breeds with the most examinees were Labrador Retriever, Toy Poodle, and Golden Retriever (Table A1). Other breeds included mixed breed, Beagle, Shih Tzu, Shiba Inu, Samoyed, Tibetan Terrier, Border Collie, Chihuahua, Papillon, French Bulldog, Shetland Sheepdog, Cavalier King Charles Spaniel, Boston Terrier, Miniature Dachshund, Pekingese, Maltese, Bichon Frise, Bernese Mountain Dog, Brussels Griffon, Miniature Schnauzer, Great Pyrenees, totaling 24 breeds in addition to the three most common ones. The average age of the dogs taking the exam was 5.6 ± 3.6 years (mean ± SD). Among the dogs taking the exam, 60 had experience working as therapy dogs, while 40 had no such experience. Among dogs with therapy experience, 53 passed and seven failed. Among dogs without experience, 16 passed and 24 failed.

Based on the temperament factors for therapy-qualified dogs identified by Sakurama et al. [13], questionnaire items were selected from the C-BARQ (Canine Behavioral Assessment and Research Questionnaires). The selected items were temporarily called TC-BARQ. The survey was conducted four times—once in April and September 2023, and again in April and September 2024—focusing on 100 dogs. This included both dogs taking the test for the first time and dogs taking it to continue participating in therapy activities. Owners rated each of the 51 TC-BARQ questions on a 5-point scale from 0 to 4. In addition to the TC-BARQ ratings, information such as the dog’s name, sex, neutered/spayed status, and breed was also collected.

Data from 100 dogs, collected through a questionnaire, were analyzed to compare dogs that passed and failed in terms of neuter status, presence of cohabiting dogs, and responses to each questionnaire item. Fisher’s exact test was used to examine whether the sex of the dog and its neutering status had any effect on its ability to pass the aptitude test. The Chi-square test was used to examine whether the presence or absence of family dogs was related to whether the dog passed or failed the therapy dog aptitude test. The Mann–Whitney U test was also used to examine whether there was a difference in TC-BARQ scores depending on whether the dog passed or failed the therapy dog aptitude test. The Holm procedure was used to adjust p-values. A p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The statistical analyses were conducted using R version 4.3.1 (The R Foundation, Vienna, Austria).

The questionnaire responses obtained from the Hokkaido Volunteer Dog Association, which cooperated in this study, were collected from all dog owners who took the aptitude test. Furthermore, all respondents completed the questionnaire except for the not-applicable items, and no exclusions were made. The statistical analysis was conducted using the data excluding not-applicable answers. The association’s aptitude test is conducted only twice a year, and the number of examinees has been declining in recent years. Consequently, securing a sufficiently large sample size currently requires a considerable amount of time. Given these circumstances, although the sample size is small and the results may be preliminary, we analyzed data from a two-year period. To prevent errors in the results, we subsequently measured and evaluated the post hoc effect size and power. Post hoc effect size calculations for neuter status (Fisher’s exact test) and presence of family dog (chi-square test) were performed with a power of 0.8 and a significance level of 0.05. Post hoc effect size and power calculations were performed for the difference in TC-BARQ question scores between passing and failing dogs. Effect sizes were calculated using Cohen’s function with a significance level of 0.05 and 1 degree of freedom. Power and required sample size were also calculated using an R package (R version 4.3.1).

3. Results

3.1. Neuter Status

The proportion of intact and neutered dogs in the pass and fail groups of the aptitude test is shown in Table 1. The presence or absence of neutering or being intact did not have a statistically significant effect on pass or fail outcomes in either sex (p = 0.34, Fisher’s exact test). Furthermore, with a power level set at 0.8, the effect size was small (w = 0.19) (Table A2).

Table 1.

The number of intact and neutered dogs in the pass and fail groups of the aptitude test.

3.2. Presence of Family Dogs

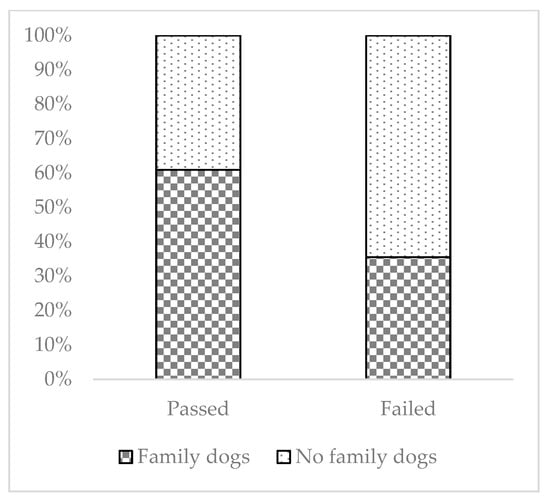

Figure 1 shows the proportion of family dogs among all test dogs, as well as their proportion among both passing and failing dogs. The presence or absence of a cohabiting dog was found to have a statistically significant effect on passing or failing (p = 0.03). However, with power set at 0.8, the effect size was small (w = 0.26) (Table A2).

Figure 1.

Family dog presence and pass rate. Passed dogs: with family dogs n = 42 (61%); without family dogs n = 27 (39%); Failed dogs: with family dogs n = 11 (35%); without family dogs n = 20 (65%).

3.3. Factors Influencing the Suitability of Therapy Dogs

Differences were observed between passing and failing dogs in response to 51 questions from all 100 dogs. Significant differences appeared in the following items: “When off the leash, returns immediately when called” (Factor 1: Trainability and obedience), “When an unfamiliar person passed by the house while the dog was outside or in the yard” (Factor 6: Territorial Aggression), “Immediately before being taken out in a car,” and “When a visitor arrived at the house” (Factor 11: Excitability) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Mann–Whitney U Test for pass/fail differences based on the TC-BARQ 51-Question score.

3.3.1. Factor 1: Trainability and Obedience

Three questions related to trainability and obedience factors were included. A significant difference was observed for “When off the leash, returns immediately when called,” but not for the other two items: “Obeys a stay command immediately” and “Slow to learn new tricks or tasks”. However, the effect size for the question showing a significant difference was small, and the power did not reach 0.8.

3.3.2. Factor 6: Territorial Aggression

There were six questions regarding factors related to territorial aggression. Among these, one question showed a significant difference, while two others were not significant but had p-values below 0.1 (Table 2). The question showing a significant difference, “When strangers walk past the home while the dog is in the yard,” had a power slightly below 0.8 (Table A3). The two questions with p-values below 0.1 involved situations where strangers entered the house, and the power was below 0.8 (Table A4).

3.3.3. Factor 11: Excitability

The excitability section contained six questions. Two of these showed significant differences, three had p-values below 0.1, and one showed no significant difference (Table 2). The question showing no significant difference was about the dog’s reaction to the doorbell ringing. The question with a p-value below 0.1 concerned excitability when interacting with family members. For these two questions, the power was not sufficiently high (Table A4). The two questions showing significant differences appeared to reveal distinctions in situations involving stronger stimuli: excitement when a stranger visits the home and excitement before going out in a car. Of these two, only “excitement when visitors arrive” had a detection power exceeding 0.8 (Table A3). For items showing significant differences or p-values below 0.1, dogs that passed the test had lower average excitability scores than those that failed.

4. Discussion

The study found differences between dogs that passed the therapy dog suitability assessment and those that did not, specifically in three factors and the presence of other dogs in the household.

4.1. Sex and Neuter Status

It has been reported that males tend to be more trainable than females. There have been no previous reports that males are more suitable than females for AAI. Spaying and castration are common in Japan, with reportedly 60% of pet dogs neutered [11]. Of the 100 dogs examined in the present study, 78 were neutered. Although there were more neutered dogs than intact, the results were unaffected by gender or neutering status. While neutering can reduce aggression between dogs, it has been reported to increase anxiety and decrease boldness in both male and female dogs. While these results suggest that neutering is not related to passing or failure in AAI, further verification is needed.

4.2. Impact of Family Dogs

Sakurama et al. [13] also identified having a family dog as a key factor affecting suitability for therapy. This study further confirmed that whether a family has another dog significantly influences outcomes, as there was a significant difference in the presence of dogs living with a family between dogs that passed and those that failed. Previous research using C-BARQ has demonstrated that living with a dog increases calmness [17] and reduces scores related to fear and anxiety [18]. In this study, 61% of the dogs that passed the assessment—more than half—lived with family dogs. This suggests that dogs from multi-dog households may have temperaments that are well-suited for animal-assisted interventions. Further studies will support this result.

4.3. Factors with Significant Differences Between Passed and Failed Dogs

4.3.1. Trainability and Obedience

This factor is essential for conducting therapy activities safely and smoothly. A significant trend was observed only in the question “When off the leash, returns immediately when called” (p = 0.031). Recall refers to the dog stopping its current activity and returning to its owner. Therefore, it is believed that dogs can exercise self-control, preventing inappropriate behaviors when feeling anxious during intervention activities [19]. Additionally, obedience training can be improved based on the owner’s commitment, allowing for some enhancement in obedience. Owners seeking therapy dog suitability assessments are likely already having their dogs undergo obedience training. The power result was not high enough in this question; however, future studies would support this result.

4.3.2. Territorial Aggression

These factors indicate a tendency to react aggressively to provocation or invasion of personal space or territory [14]. Dogs scoring high on these traits are considered to exhibit intense anxiety or aggression toward people. A notable trend was only observed in the question “When strangers walk past the home while the dog is in the yard” (p = 0.017). Displaying aggression during activities can cause injuries to therapy participants and decrease the dog’s quality of life due to stress related to the activity. Therefore, even if a dog typically does not show aggression, if it reacts aggressively to outsiders invading its personal space, it is deemed unsuitable for therapy work. The power result was almost 0.8, so future studies should support this result.

4.3.3. Excitability

These factors suggest that dogs tend to react strongly to stimulating events such as walks, car rides, or visitors [14]. Dogs with high scores on these traits often find it difficult to control their excitement and can become overly aroused. Significant trends were only seen in the questions “Just before being taken on a car trip” (p = 0.022) and “When visitors arrive at its home” (p = 0.004). The average scores of the dogs that passed were considered “mild”, while the dogs that failed showed “moderate” results in both questions. This arousal might lead to barking or jumping, which can pose a risk of injury to therapy recipients and make them unsuitable as therapy dogs. This is likely because mild activity levels during AAA interactions with people are important, and the dog needs to enjoy these interactions [13].

4.4. Does TC-BARQ Support Aptitude Tests?

This study used TC-BARQ to assess the scores of both qualified and unqualified dogs across 51 questions encompassing 14 factors. An important point is whether the qualified dogs achieved the score levels for the 14 factors deemed suitable for therapy dogs, as indicated by Sakurama et al. [13]. Results showed that some dogs passed even though their scores fell outside the ideal range on 26 questions. This suggests that traits overlooked in the aptitude test may have led to issues in the AAA program. Given this, evaluating a dog’s suitability for AAA may require not only practical aptitude tests but also prior confirmation of the dog’s inherent traits, since the Hokkaido Volunteer Dog Association’s AAA sessions last 30 min each. Because recipients may not always behave ideally toward the dogs, the activity time per person is kept short, and the overall duration remains manageable. Therefore, when dogs participate in AAA, including some safety measures is recommended. Besides practical skills tests, personality assessments like TC-BARQ should also be routinely incorporated into aptitude evaluations.

5. Conclusions

The TC-BARQ includes factors identified by Sakurama et al. [13] based on the C-BARQ scores of dogs that passed the therapy suitability test. Therefore, it is clear that dogs must possess each factor if they are to become therapy dogs. This study examined whether there were differences in scores for these factors between dogs that passed and those that failed. Dogs brought for therapy dog suitability testing are likely to exhibit traits such as high trainability, mild excitability, and low aggression. Thus, the lack of significant differences between passing and failing dogs can be understood in this way. The presence of family dogs may significantly influence a dog’s personality, which is important for therapy dogs. Increasing the sample size and updating results in future research should help to increase the number of suitability test participants and make it easier to identify suitable candidates.

Author Contributions

The idea for the article was conceived by T.K. The experiments were designed by T.K. and M.S. The survey was performed by M.S., M.I., Y.N. and S.K. The data were analyzed by N.E., S.K., S.T. and Y.N. The article was written by N.E., S.K. and S.K. and reviewed by T.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethical Committee of Rakuno Gakuen University, Hokkaido, Japan (VH19B9). The approved date was 16 July 2019.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all owners of the animals who belong to the NPO Hokkaido Volunteer Dog Association involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are not publicly available. Please contact the corresponding author with any enquiries.

Acknowledgments

We thank all members of the NPO Hokkaido Volunteer Dog Association for their cooperation in the survey.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with a minor correction to the Institutional Review Board Statement. This change does not affect the scientific content of the article.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviation is used in this manuscript:

| NPO | Nonprofit organization |

Appendix A

Table A1.

The number of the passed dogs of the aptitude test and all test taker in each dog breed, with their pass rate.

Table A1.

The number of the passed dogs of the aptitude test and all test taker in each dog breed, with their pass rate.

| Number | Dog Breeds | Passed/Tested Head | Pass Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Labrador Retriever | 17/20 | 85 |

| 2 | Toy Poodle | 11/13 | 84.6 |

| 3 | Golden Retriever | 8/10 | 80 |

| 4 | Beagle | 2/5 | 40 |

| 5 | Shih Tzu | 2/5 | 40 |

| 6 | Shiba Inu | 1/4 | 25 |

| 7 | Samoyed | 2/3 | 66.7 |

| 8 | Tibetan Terrier | 2/3 | 66.7 |

| 9 | Border Collie | 2/2 | 100 |

| 10 | Chihuahua | 2/2 | 100 |

| 11 | Papillon | 2/2 | 100 |

| 12 | French Bulldog | 2/2 | 100 |

| 13 | Shetland Sheepdog | 2/2 | 100 |

| 14 | Cavalier King Charles Spaniel | 3/3 | 100 |

| 15 | Boston Terrier | 1/2 | 50 |

| 16 | Miniature Dachshund | 1/3 | 33.3 |

| 17 | Pekingese | 1/2 | 50 |

| 18 | Maltese | 1/2 | 50 |

| 19 | Bichon Frise | 1/1 | 100 |

| 20 | Bernese Mountain Dog | 1/1 | 100 |

| 21 | Brussels Griffon | 0/1 | 0 |

| 22 | Miniature Schnauzer | 0/1 | 0 |

| 23 | Great Pyrenees | 0/2 | 0 |

| 24 | Mix breeds | 4/9 | 44.4 |

Table A2.

Post hoc power analysis of neuter status (Fisher’s exact test) and presence of family dogs (Chi-square test).

Table A2.

Post hoc power analysis of neuter status (Fisher’s exact test) and presence of family dogs (Chi-square test).

| p Value | Effect Size (Effect) | Sample Size | df | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neuter Status | 0.343 | w = 0.1853264 (small) | 317 | 3 |

| Presence of Family Dogs | 0.0327 | w = 0.2602082 (small) | 115 | 1 |

Power = 0.8, Significance level = 0.05, df: degree of freedom.

Table A3.

Post hoc power analysis of TC-BARQ 51-question score, Mann–Whitney U test (p < 0.05).

Table A3.

Post hoc power analysis of TC-BARQ 51-question score, Mann–Whitney U test (p < 0.05).

| p Value | Cohen’s d (Effect) | Power | Sample Size | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Trainability and obedience | ||||

| When off the leash, returns immediately when called. | 0.031 | −0.485 (small) | 0.612 | 67 |

| 6. Territorial aggression | ||||

| When strangers walk past the home while the dog is in the yard. | 0.017 | 0.576 (medium) | 0.76 | 48 |

| 11. Excitability | ||||

| When visitors arrive at its home. | 0.004 | 0.667 (medium) | 0.87 | 36 |

| Just before being taken on a car trip. | 0.022 | 0.497 (small) | 0.634 | 64 |

Sample size: Estimated one-sided sample size, df (degree of freedom) = 1, Significance level = 0.05.

Table A4.

Post hoc power analysis of TC-BARQ 51-question score Mann–Whitney U test (p < 0.1).

Table A4.

Post hoc power analysis of TC-BARQ 51-question score Mann–Whitney U test (p < 0.1).

| p Value | Cohen’s d (Effect) | Power | Sample Size | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6. Territorial aggression | ||||

| Toward unfamiliar persons visiting your home. | 0.078 | 0.394 (small) | 0.445 | 102 |

| When an unfamiliar person approaches the owner or a member of the owner’s family at home. | 0.078 | 0.528 (medium) | 0.685 | 57 |

| 9. Resource guarding-related aggression | ||||

| When food is taken away by a member of the household. | 0.062 | 0.422 (small) | 0.497 | 89 |

| 11. Excitability | ||||

| Just before being taken for a walk. | 0.087 | 0.375 (small) | 0.411 | 112 |

| When you or other members of the household come home after a brief absence. | 0.075 | 0.389 (small) | 0.436 | 104 |

| When playing with you or other members of your household. | 0.086 | 0.377 (small) | 0.415 | 111 |

Sample size: Estimated one-sided sample size, df (degree of freedom) = 1, Significance level = 0.05.

References

- Rodríguez-Martínez, M.D.C.; De la Plana Maestre, A.; Armenta-Peinado, J.A.; Barbancho, M.Á.; García-Casares, N. Evidence of animal-assisted therapy in neurological diseases in adults: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonioli, C.; Reveley, M.A. Randomised controlled trial of animal facilitated therapy with dolphins in the treatment of depression. BMJ 2005, 331, 1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huber, A.; Klug, S.J.; Abraham, A.; Westenberg, E.; Schmidt, V.; Winkler, A.S. Animal-assisted interventions improve mental, but not cognitive or physiological health outcomes of higher education students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2024, 22, 1597–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward, S.C.; Whalon, K.; Rusnak, K.; Wendell, K.; Paschall, N. The association between therapeutic horseback riding and the social communication and sensory reactions of children with autism. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2013, 43, 2190–2198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, C.; Dossett, K.; Walker, D.L. Equine-assisted therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder among first responders. Psychol. Rep. 2024, 127, 2203–2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hediger, K.; Thommen, S.; Wagner, C.; Gaab, J.; Hund-Georgiadis, M. Effects of animal-assisted therapy on social behaviour in patients with acquired brain injury: A randomised controlled trial. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 5831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Haire, M.E.; McKenzie, S.J.; Beck, A.M.; Slaughter, V. Social behaviors increase in children with autism in the presence of animals compared to toys. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e57010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IAHAIO. The IAHAIO Definitions for Animal Assisted Intervention and Guidelines for Wellness of Animals Involved in AAI. 2018. Available online: https://iahaio.org/iahaio-white-paper-updated-april-2018/ (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Kumasaka, T.; Masu, H.; Kataoka, M. Attitude Survey of Nursing Personnel Working at Hospitals Towards Animal Assisted Intervention: Focus on a Psychiatric Hospital Planning to Introduce Animals. J. Jpn. Assoc. Rural. Med. 2008, 57, 34–49. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, S.; Sakuramoto, M. Healthcare costs reduction through an introduction of Animal Assisted Therapy. Hokkai-Gakuen Organ. Knowl. Ubiquitous Through Gaining Arch. 2013, 13, 9–15. [Google Scholar]

- Japan Pet Food Association. Available online: https://petfood.or.jp/data-chart/ (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Hokkaido Volunteer Dog Association. About the Aptitude Test. Available online: http://www.volunteer-dog.com/therapy/application.html (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Sakurama, M.; Ito, M.; Nakanowataru, Y.; Kooriyama, T. Selection of appropriate dogs to be therapy dogs using the C-BARQ. Animals 2023, 13, 834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, Y.; Serpell, J.A. Development and validation of a questionnaire for measuring behavior and temperament traits in pet dogs. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2003, 223, 1293–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavalli, C.M.; Carballo, F.; Dzik, M.V.; Underwood, S.; Bentosela, M. Are animal-assisted activity dogs different from pet dogs? A comparison of their sociocognitive abilities. J. Vet. Behav. 2018, 23, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullough, A.; Jenkins, M.A.; Ruehrdanz, A.; Gilmer, M.J.; Olson, J.; Pawar, A.; O’Haire, M.E. Physiological and behavioral effects of animal-assisted interventions on therapy dogs in pediatric oncology settings. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2018, 200, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubinyi, E.; Turcsán, B.; Miklósi, Á. Dog and owner demographic characteristics and dog personality trait associations. Behav. Process. 2009, 81, 392–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serpell, J.A.; Duffy, D.L. Aspects of juvenile and adolescent environment predict aggression and fear in 12-month-old guide dogs. Front. Vet. Sci. 2016, 3, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fine, A.H. 10-Incorporating Animal-Assisted Therapy into Psychotherapy: Guidelines and Suggestions for Therapists. In Handbook on Animal-Assisted Therapy: Theoretical Foundations and Guidelines for Practice; Aubrey, H.F., Ed.; Academic Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 169–191. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).