Abstract

Parvovirus B19 is a DNA virus. Most parvoviruses infect animals; Parvovirus B19 infects humans. Parvovirus B19 is mainly transmitted through respiratory droplets during close contact, but additional routes such as transmission through contaminated blood products and vertical transmission from mother to fetus have also been documented. Infections occur throughout the year, with a seasonal increase between late winter and early summer. Clinical symptoms depend on age, and on patients’ immune status. Healthy, immunocompetent individuals experience asymptomatic or mild infections including a febrile rash; serious complications rarely appear, such as rheumatoid-like arthritis or acute myocarditis. Clusters of myocarditis cases following Parvovirus B19 infections appeared in a daycare in Thessaloniki in 2024. To molecularly and phylogenetically characterize Parvovirus B19 strains detected during a pediatric outbreak associated with elevated troponin levels and myocarditis in Northern Greece, and to compare these strains with isolates from adult cases with mild symptoms in order to explore potential associations between viral genetic variability and cardiac involvement. MinION sequencing protocol was performed for nine whole blood samples, seven belonging to children with myocarditis, and two to adults presenting mild symptoms. Statistical analysis was performed with QualiMap 2.3 and relevant tools. Phylogenetic analysis identified distinct viral groups originating from the samples investigated. A distinct branch was formed by the reference genome and the ones of the adults’ samples, while samples from children with myocarditis provided discrete branches differing from the reference one. The findings demonstrate a clear association between Parvovirus B19 infection and myocarditis in the pediatric cases analyzed. The detected viral strains, including variants identified in several samples, support the role of Parvovirus B19 as a contributing factor in post-infectious cardiac involvement. Although these results reinforce the clinical relevance of Parvovirus B19 in childhood myocarditis, expanding the sample size would allow for a more robust characterization of circulating strains and confirmation of the observed patterns.

1. Introduction

Parvovirus B19 belongs to the Parvoviridae family. It is an icosahedral, non-enveloped virus with a diameter of 23 nm. The virus has a single-stranded linear DNA genome of 5.6 kb (5596 nt) that replicates using two identical inverted terminal regions (ITR). As with all viruses, parvovirus encodes some of the proteins that are necessary for infection and replication in the host cell. The most important are the nonstructural protein (NS1) and the two capsid proteins (VP1 and VP2) that are encoded by open reading frames ORF1, and ORF3. The capsid proteins (VP1 and VP2) are encoded by ORF1, and the nonstructural protein (NS1) by ORF3. In addition, ORF1 and ORF2 encode a small unknown protein (7.5 kb) and another unknown protein (11 kb), respectively [1].

The gene encoding the NS1 protein is located between bases 616 and 2631 and is responsible for causing cell death through host cell apoptosis. In contrast, the capsid proteins are responsible for the viral capsid construction and the viral attachment to the host cell receptors. They are divided into minor and major; the difference between the two proteins is determined by approximately 227 amino acids (aa) at the amino-terminal end of the VP1 protein (https://www.uniprot.org/, accessed on 4 January 2025). The minor protein (VP1) encoding gene is located in bases 2624–4969 and bases 3305–4969 (VP2). The proteins of unknown function are encoded by genes located in bases 2084–2308 (7.5 kb) and 4890–5174 (11 kb) (GenBank: AY386330.1).

Most parvoviruses mainly infect animals, cats, and dogs, with Parvovirus B19 being the only one infecting humans. The virus mostly affects children aged 4–10; by the age of 20 years, 50% of the population have specific antibodies. Infections caused by Parvovirus B19 occur throughout the year (endemic), with a seasonal increase in late winter, spring and early summer. The clinical symptoms depend on age, as well as on patients’ immune and hematological status. Most often patients infected by Parvovirus B19 are asymptomatic. Otherwise, symptoms are usually mild and may include fever, headache, and cough. However, more serious complications can appear, such as rheumatoid-like arthritis, acute myocarditis, or acute hepatitis. Several studies have correlated Parvovirus B19 infection with myocarditis probably resulting in dilated cardiomyopathy. Although numerous studies have detected Parvovirus B19 DNA in myocardial tissue of patients with myocarditis and dilated cardiomyopathy, the clinical significance of this finding remains debated. Several investigations have reported a high prevalence of Parvovirus B19 genomes in endomyocardial biopsies from both symptomatic patients and asymptomatic individuals, suggesting viral persistence without a direct pathogenic effect. In contrast, other studies have demonstrated active viral replication, endothelial dysfunction, and inflammatory responses associated with Parvovirus B19 infection, supporting a potential role in myocardial injury. These contradictory findings highlight the ongoing uncertainty regarding the pathogenic relevance of Parvovirus B19 and underscore the need for molecular and phylogenetic studies during well-documented clinical outbreaks [2]. Myocarditis is an infection of the heart muscle, usually because of cardiotropic viral infections. The pathogenetic mechanism of the disease is often obscure, as etiologies vary. Cases of myocarditis have been related to the presence of Parvovirus B19, both in children and adults.

In the middle of March 2024, the National Public Health Organization of Greece was notified by hospitals in the regional unit of Thessaloniki about a series of cases involving elevated troponin levels in children attending a local daycare–kindergarten. An epidemiological investigation revealed that from March to April 2024, 11 out of 24 children aged 3–5 years from two classes of the daycare–kindergarten presented increased troponin levels. Among these children, one developed acute myocarditis and sadly passed away, another presented with myopericarditis, two had small pericardial fluid collections with normal heart contractility, and the remaining children were asymptomatic with normal cardiac function. Laboratory testing indicated that 7 out of the 11 children with elevated troponin had evidence of recent parvovirus infection (IgM positive samples) and two were IgG positive, which was consistent with a history of parvovirus clinical diagnosis among many of the children of the daycare–kindergarten. Further analysis of clinical samples (using Film Array respiratory panel and stool testing) found co-infection with rhinovirus/enterovirus in six out of nine children with parvovirus. In addition to the outbreak, it is worth noting that from March to April 2024, four more children aged 2 years were admitted to a hospital in Thessaloniki with parvovirus infection and elevated troponin levels. Among these, two children developed myocarditis, with one unfortunate death.

The mechanisms by which human Parvovirus B19 contributes to cardiac complications such as myocarditis are complex and not yet fully elucidated. Current evidence suggests that the virus exhibits tropism for endothelial cells and cardiomyocytes through the globoside (P antigen) receptor, leading to direct cellular injury. Viral replication and expression of the non-structural protein NS1 have been shown to induce apoptosis and endothelial dysfunction, which may result in microvascular damage within the myocardium. In addition to direct cytopathic effects, immune-mediated mechanisms appear to play a significant role. The VP1 unique region (VP1u) has been implicated in the activation of pro-inflammatory pathways, promoting the release of cytokines such as interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor-α, thereby amplifying myocardial inflammation. Persistent viral DNA within cardiac tissue may further sustain chronic inflammatory responses, contributing to myocardial injury and, in some cases, progression to dilated cardiomyopathy [3]. The aim was to genetically characterize the Parvovirus B19 strains that circulated in the pediatric population of Northern Greece during the March–April 2024 outbreak, and to compare these strains with previously identified variants to explain the observed differences in clinical symptomatology.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Extraction of DNA, Amplification with PCR and Sequencing

DNA extraction was performed with a spin column procedure (QIAamp DNA Mini Kit™, QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany), from 200 μL of an EDTA blood sample. All samples were tested with the Parvovirus B19 PCR Kit 1.0 (RealStar®, Altona Diagnostics, Hamburg, Germany) in order to determine positivity and viral load.

2.2. Nested PCR

Nested PCR was employed in order to increase the sensitivity of viral DNA detection, as the initial sample concentration was extremely low. By using two successive rounds of amplification, this method enhances specificity and maximizes the yield of the target sequence, allowing reliable identification of Parvovirus B19 in low-titer clinical specimens.

A total of 10 μL of extracted DNA was used as a template in nested PCRs. Each sample was amplified by 8 different pairs of primers (Eurofins Genomics, Ebersberg, Germany [4] for two-round PCR amplification. The two rounds included 40 cycles each and consisted of initial denaturation at 95 °C for 6 min, 95 °C for 30 s, 55 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 30 s. The device in use was a PTC-200 Peltier Thermal Cycler (MJ RESEARCH, Waltham, MA, USA). The Nested PCR products were then analyzed using 1.5% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide and visualized in a UV-illumination device.

2.3. Library Preparation and MinION Sequencing Protocol

An NEB Ultra II DNA Library Prep Kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA, Cat.Number: E7645L) was used for the whole genome libraries. Overall, the protocol consisted of DNA extraction from blood samples, followed by nested PCR, electrophoresis in 1.5% agarose gel, and fragmentation of the samples. The ends of the fragments were then enzyme-treated in order to create a dA- tail. Those tails will help the ligation between the native barcode and adapter. For native barcode ligation, each sample had its own barcode. Then, samples were pooled. The adapters’ ligated fragments were then cleaned up using the AMPure XP bead (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA, Cat.Number: A63882). The final library was measured with Qubit High Sensitivity reagent (Thermo Fischer Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The final concentration was 10 ng/μL [5].

2.4. Sequencing Data Analysis

The viral strains were analyzed using a bioinformatics pipeline optimized for Nanopore long-read sequencing data. Raw sequencing reads were first evaluated for their quality using FastQC v0.11.9 (Babraham Bioinformatics, Babahram Institute, Cambridge, UK) followed by quality trimming and adapter removal with fastp 0.23.4 (Shifu Chen, Lab of Bioinformatics, BGI, Shenzhen, China) [6] and porechop 0.2.4 (Ryan Wick, The James Hutton Institute, Dundee, Scotland, UK), respectively. Each gene in the genome of each strain was determined. The high-quality reads were aligned to the reference genome of human Parvovirus B19 isolate J35 (NC_000883.2) using minimap2 2.26-r1175 (Heng Li, Department of Data Sciences, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA, USA) with parameters optimized for Nanopore long reads. The resulting alignment files were checked for quality using QualiMap 2.3 (Centro de Investigación Príncipe Felipe, Valencia, Spain; Max Planck Institute for Infection Biology, Berlin, Germany) [7] and sorted and then indexed using SAMtools 1.17. Variant calling was conducted by Clair3 1.08 (HKU-BAL, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China) [8] using a pre-trained model for ONT data (r.9.4.1), and snpEff 4.3.1 t was used to assess the impact of the high-quality variants. Strain genomes were constructed using bcftools consensus 1.15.1. Multiple sequence alignments were generated using MAFFT v7.526 (Kazutaka Katoh, Bioinformatics Center, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan) with default parameters, which apply the FFT-NS-2 progressive alignment algorithm together with automatic optimization of gap penalties and iterative refinement. Phylogenetic inference was performed in IQ-TREE v2.3.5 under the default maximum-likelihood framework, using the FFT-NS-2 tree-search strategy. The optimal substitution model was automatically selected by ModelFinder. Branch support was evaluated using the default ultrafast bootstrap (UFBoot) with 1000 replicates, along with SH-aLRT testing [9,10,11]. The resulting phylogeny was visualized using iTOL 7.2.2 (GenBank: PX737888-PX737896). All analyses were conducted on a high-performance Linux Ubuntu 20.04.6 64-bit workstation (Intel® Core™ i7-12700K × 20 Intel Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA, NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3090, NVIDIA Corporation, Santa Clara, USA). See Table 1 for details.

Ethical approval was obtained prior to the study from Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. No artificial intelligence tools were used.

3. Results

3.1. Phylogenetic Tree Results

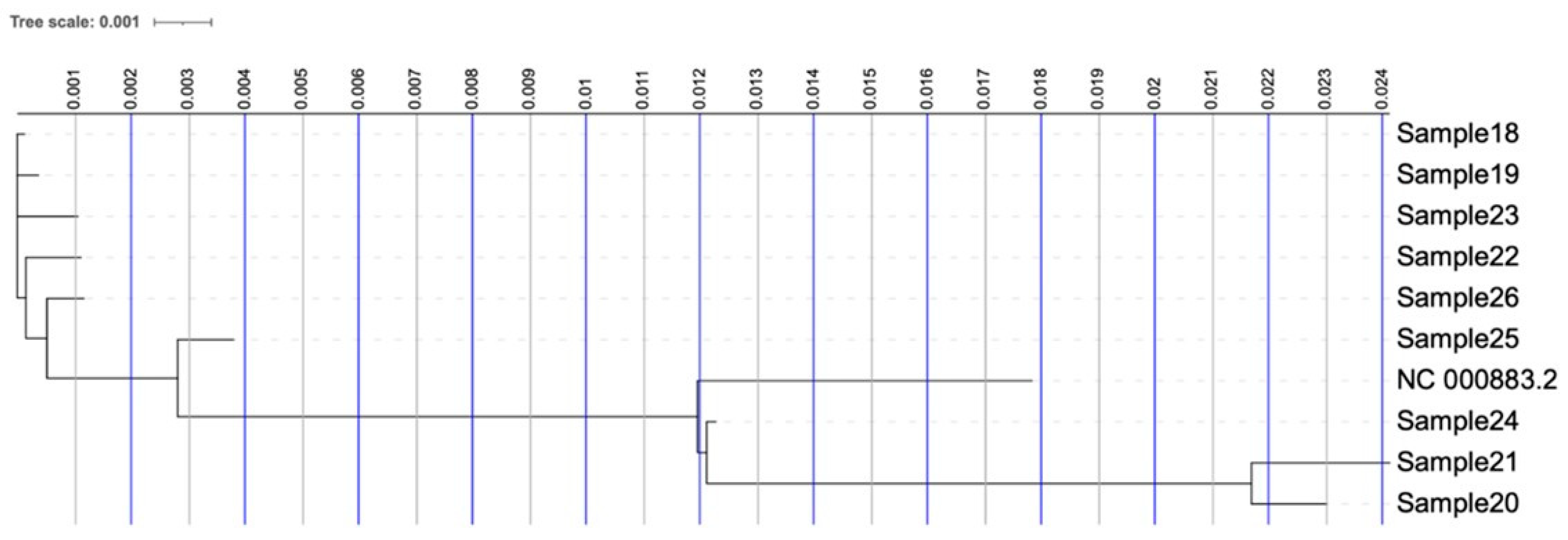

The phylogenetic tree in Figure 1 illustrates the evolutionary relationship of the strains (Table 1) and the reference Human Parvovirus B19 (NC_000883.2). Strains are grouped in two clusters that are both evolutionarily distinguished from the reference Human Parvovirus B19 genome. The strains infected preschool-aged children at the nursery and those identified in patients diagnosed with myocarditis form a distinct phylogenetic clade, which is distant from both the control/adult samples and a case involving an infected child from outside the Thessaloniki region who exhibited no myocarditis symptoms (Sample24).

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree of the nine clinical isolates and the reference Human Parvovirus B19 genome (NC_000883.2).

Table 1.

Sample annotation. All clinical samples for Parvovirus B19 PCR testing were obtained from peripheral blood collected under sterile conditions. Serum was separated by centrifugation. All specimens were processed according to standardized laboratory protocols to ensure sample integrity and prevent contamination.

Table 1.

Sample annotation. All clinical samples for Parvovirus B19 PCR testing were obtained from peripheral blood collected under sterile conditions. Serum was separated by centrifugation. All specimens were processed according to standardized laboratory protocols to ensure sample integrity and prevent contamination.

| Sample ID | Age | Clinical Characteristics | Date | Region | Co-Infection |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18 | 6 years old | Isolated elevation of troponin levels (normal cardiac function and without symptoms) | 4 July 2024 | Thessaloniki | |

| 19 | 4 years old | Acute myocarditis | 25 July 2024 | Thessaloniki | Human rhinovirus/enterovirus |

| 20 | 4 years old | Isolated elevation of troponin levels (normal cardiac function and without symptoms) | 4 July 2024 | Thessaloniki | Human rhinovirus/enterovirus |

| 21 | 28 years old | A * | - | Thessaloniki | |

| 22 | 3.5 years old (daycare) | Acute myocarditis | 12 April 2024 | Thessaloniki | Human rhinovirus/enterovirus |

| 23 | 2 years old (daycare) | Acute myocarditis (death) | 22 June 2024 | Thessaloniki | Human rhinovirus/enterovirus |

| 24 | 60 years old | A * | - | Thessaloniki | |

| 25 | 3.5 years old (daycare) | Acute myocarditis | 13 June 2024 | Thessaloniki | Human rhinovirus/enterovirus |

| 26 | 4 years old (daycare) | Acute myocarditis | 6 March 2024 | Thessaloniki | Human rhinovirus/enterovirus |

* Adult controls with mild symptoms.

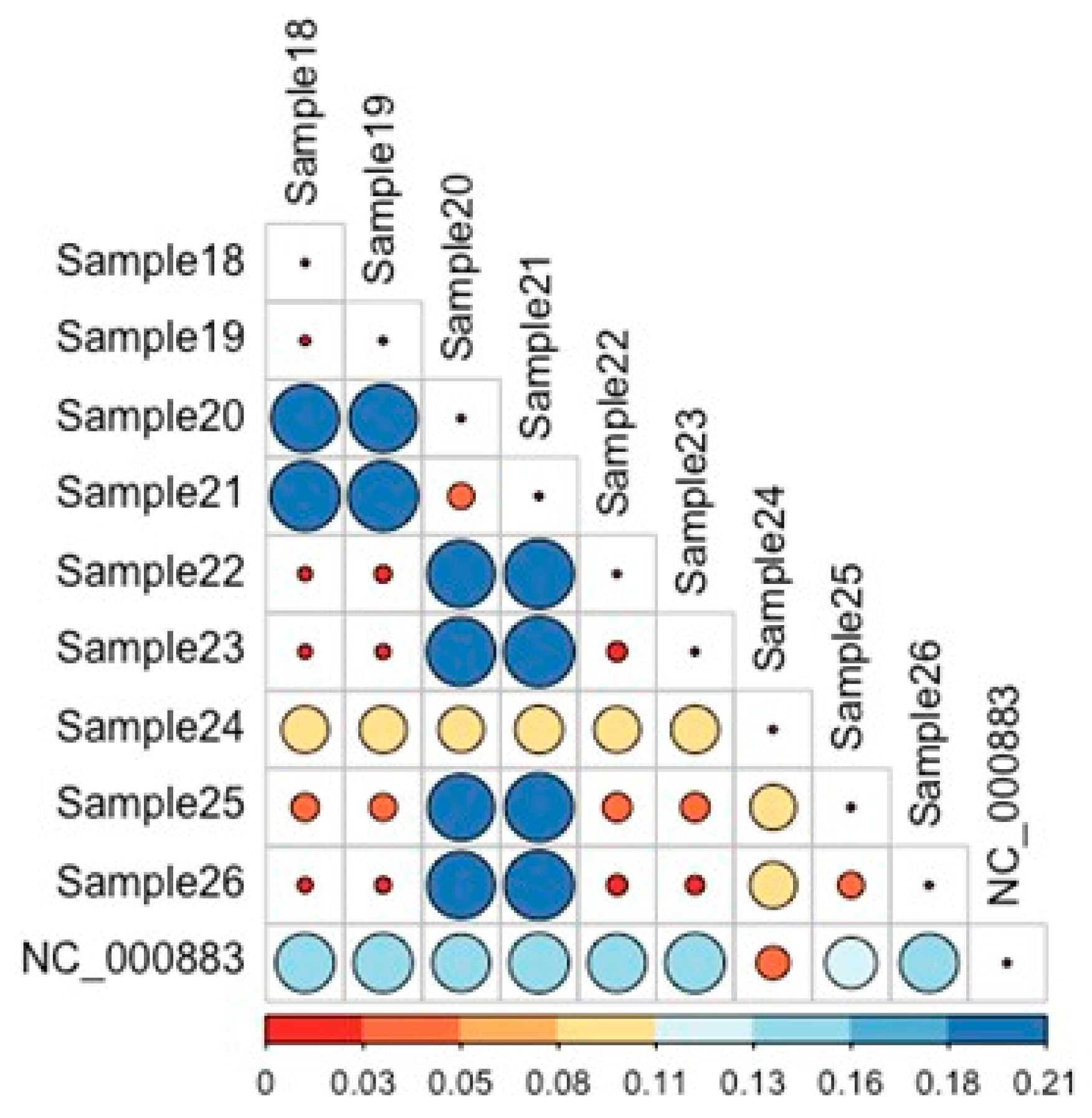

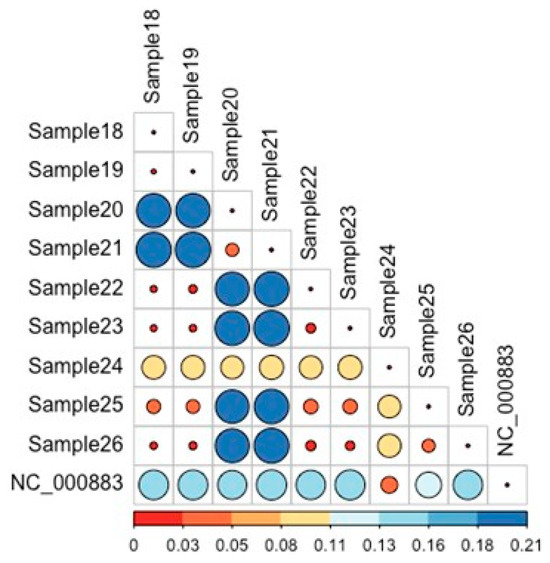

Pairwise Analysis of the Maximum Likelihood

Pairwise analysis of the maximum-likelihood distances shown in Figure 2 corroborates the findings in Figure 1. Sample24 exhibits a consistently larger evolutionary distance to all other strains, and a lower distance to the reference genome among all other isolates. The distance of Sample20 and Sample21, Sample22 and Sample23, Sample25 and Sample26 is lower than other pairwise comparisons.

Figure 2.

Pairwise analysis of maximum-likelihood distances among Parvovirus B19 strains. Bars represent the relative genetic distances calculated between each pair of sequences. Colors indicate the magnitude of genetic divergence, while the corresponding percentage values derived from the pairwise comparison shown to provide a quantitative measure of sequence similarity/dissimilarity. Sample24 consistently demonstrates a greater evolutionary divergence from all other isolates, while maintaining the shortest distance to the reference genome. Additionally, the distances observed between Sample20 and Sample21, Sample22 and Sample23, as well as Sample25 and Sample26, are notably lower than those of the remaining pairwise comparisons, indicating closer genetic relatedness within these sample pairs.

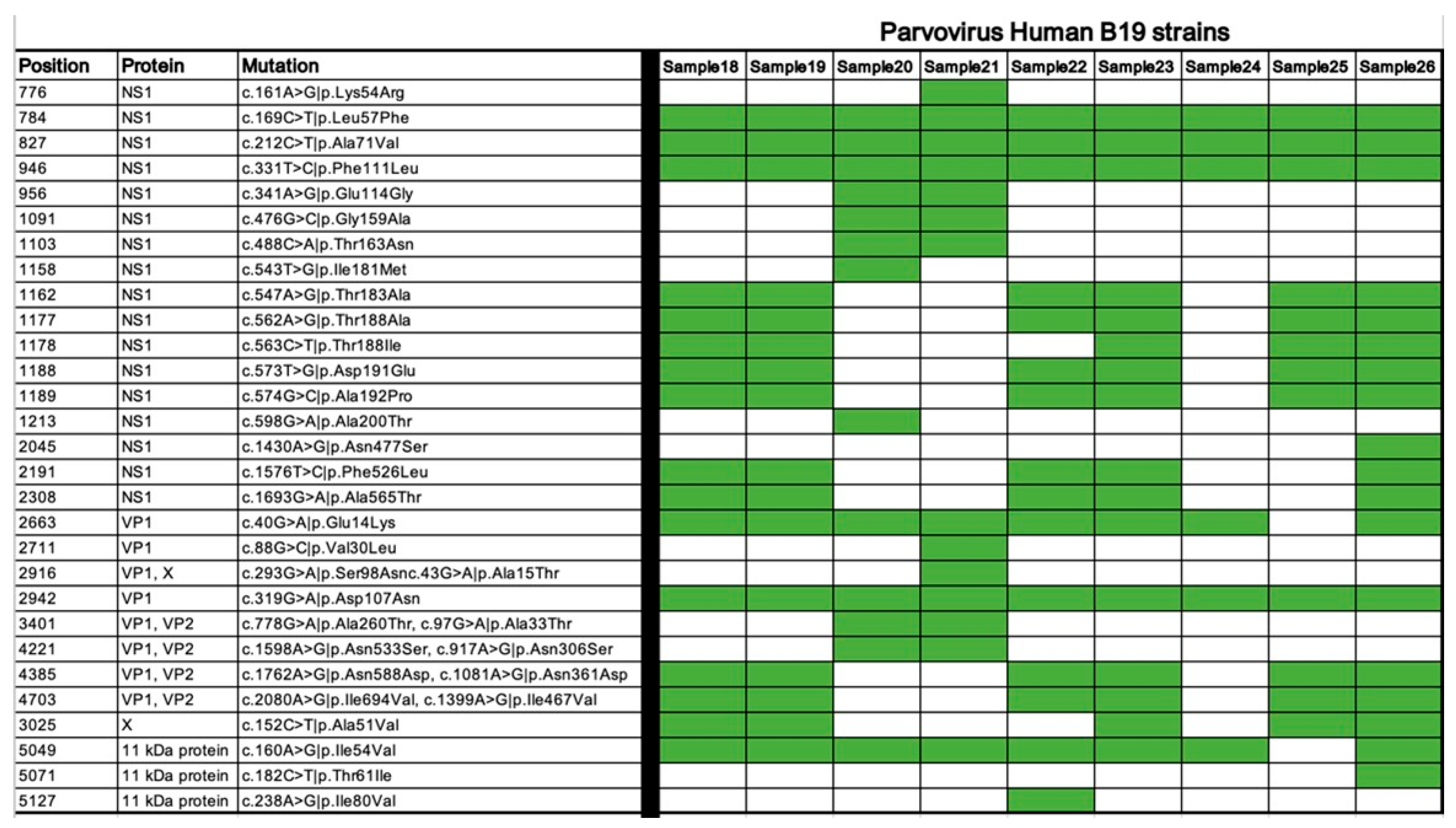

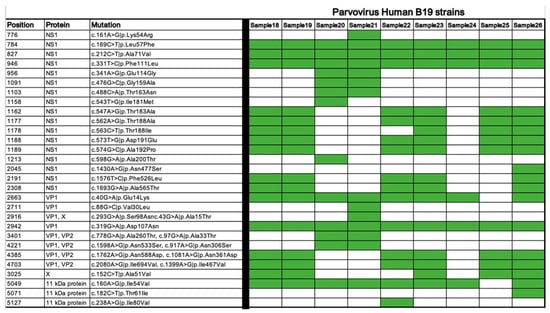

3.2. Results in Figures

As shown in Figure 3, there are some mutual mutations in all samples, but also myocarditis-associated strains harbored missense mutations in NS1 and VP1 regions do not present in non-cardiotropic isolates, suggesting these mutations may alter protein function in a way that enhances viral replication or immune activation.

Figure 3.

Missense coding variants of the Human Parvovirus B19 strains. The presence of the listed mutations in each strain is shown in green.

4. Discussion

The present study investigates the molecular and phylogenetic characteristics of Parvovirus B19 strains associated with a cluster of pediatric myocarditis cases in Thessaloniki, Greece, during the spring of 2024. Our findings are consistent with recent international reports indicating an apparent increase in severe Parvovirus B19-associated cardiac complications among young children, particularly those attending communal childcare settings [12,13].

The analysis of full genome sequences from nine clinical isolates revealed the presence of two genetically distinct clades, with one clade exclusively composed of strains isolated from children with elevated troponin levels and clinical or subclinical myocarditis. These strains were phylogenetically distant from both the reference genome (NC_000883.2) and the strains isolated from asymptomatic adults or children outside the affected region.

These observations are consistent with recent epidemiological data from Italy, where a Parvovirus B19-associated outbreak of pediatric myocarditis occurred in early 2024, affecting children aged 3–5 years [12]. The Italian outbreak, similarly characterized by elevated troponin levels, myopericarditis, and sudden cardiac death, raised concerns about the emergence of virulent Parvovirus B19 strains with increased cardiac tropism. Comparable findings have been reported in Germany and Japan, where variants were disproportionately represented in severe pediatric cardiac presentations [14,15]. Both our Greek cohort and the Italian outbreak exhibited seasonality, geographical clustering, and age-specific vulnerability, suggesting either convergent evolution or a shared lineage of circulating Parvovirus B19 variants with pathogenic potential.

Human Parvovirus B19 infection is distributed worldwide, with numerous studies reporting variable prevalence across continents, age groups, and populations. Seroprevalence studies from Europe and North America indicate that approximately 40–60% of young adults have evidence of past infection, with rates increasing to 70–85% in older age groups. In developing regions of Africa, Asia, and South America, seroprevalence is often higher, reflecting earlier exposure during childhood. Detection of Parvovirus B19 DNA in cases of myocarditis and dilated cardiomyopathy has been reported in multiple countries. In Europe, studies from Germany, Italy, and Sweden have identified Parvovirus B19 as one of the most frequently detected viral genomes in endomyocardial biopsies of both pediatric and adult patients. Similar findings have been reported in Asia, particularly in Japan and China, where Parvovirus B19 DNA has been associated with acute myocarditis and inflammatory cardiomyopathy. Reports from South America and Africa further confirm the global circulation of Parvovirus B19 strains and their involvement in a wide spectrum of clinical manifestations, ranging from mild exanthematous disease to severe cardiac involvement. Differences in reported prevalence and clinical severity among countries may be influenced by variations in circulating viral genotypes, host immune status, age distribution, diagnostic methodologies, and surveillance practices. In this context, the present study adds valuable molecular and phylogenetic data from Greece, a region for which genomic data on circulating Parvovirus B19 strains remain limited, and highlights the importance of international molecular surveillance to better understand the epidemiology and pathogenic potential of this virus [16,17,18,19].

The association between Parvovirus B19 and myocarditis, although long debated, has been increasingly supported by histopathological and molecular studies demonstrating viral replication in myocardial tissues. The virus infects endothelial and myocardial cells, particularly via the globoside (P antigen) receptor, with cytotoxic effects mediated by the NS1 protein [20,21]. VP1u, a domain within the capsid protein, has also been shown to trigger inflammatory responses by upregulating pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α in cardiac endothelial cells [16,20]. In our cohort, myocarditis-associated strains harbored missense mutations in NS1 and VP1 regions not present in non-cardiotropic isolates, suggesting these mutations may alter protein function in a way that enhances viral replication or immune activation.

Interestingly, the adult control samples and one non-myocarditis pediatric sample (Sample24) formed a separate clade, showing greater similarity to the reference genome and fewer amino acid changes. This phylogenetic separation reinforces the hypothesis that specific genotypes or quasi-species of Parvovirus B19 may possess enhanced cardiotropism, particularly in pediatric populations with immature immune systems. Previous genomic analyses by Molenaar-de Backer et al. have shown that virus exists as genetically stable but immunologically diverse variants, with minor sequence changes potentially influencing tissue tropism and immune evasion [21].

Co-infection was a prominent feature in both the Greek and Italian outbreaks. Six of the nine myocarditis cases in our study were co-infected with rhinovirus or enterovirus, echoing earlier findings where viral co-infections exacerbated endothelial permeability and inflammatory responses [22,23]. Prior research has shown that rhinovirus-mediated epithelial barrier disruption and TLR3 activation may potentiate virus entry and replication in cardiac tissues [23]. Moreover, interactions between enteroviruses and Parvovirus B19 have been documented in post-viral myocarditis, supporting a “two-hit” model of viral cardiomyopathy [22].

The clustering of cases in a single daycare center raises the possibility of localized transmission of a more virulent strain, amplified by close-contact environments and host susceptibility factors. Similar transmission dynamics were noted in a 2015 outbreak in Sweden, where a cluster of severe Parvovirus B19-associated complications was observed in preschool-aged children [23].

5. Conclusions

This study provides molecular and phylogenetic characterization of Parvovirus B19 strains circulating in Northern Greece during a pediatric outbreak associated with elevated troponin levels and myocarditis. The clustering of strains isolated from affected children into a distinct phylogenetic clade, compared with adult control samples and the reference genome, supports an association between specific Parvovirus B19 variants and cardiac involvement in young children. Although causality cannot be established and functional validation of the identified mutations is lacking, these findings underline the importance of the genomic surveillance of Parvovirus B19 during outbreaks with severe clinical manifestations. Further studies with larger cohorts are required to clarify the pathogenic mechanisms and to assess the clinical significance of the observed genetic variability.

6. Limitations

This study is limited by its small cohort size and lack of cardiac biopsy specimens, which would allow confirmation of active viral replication in the myocardium. Furthermore, host genetic predisposition and immune response modulation were not evaluated. Future multicenter studies incorporating immunogenetic profiling and functional assays will be essential to define the mechanisms underlying viral cardiotropism and disease severity in pediatric populations. It should be acknowledged as a study limitation that, although mutations in NS1 and VP1 were observed, their potential role in enhancing cardiotropism has not been validated through functional or experimental assays; thus, the pathogenic significance of these sequence variations remains unconfirmed. Due to the limited availability of complete genome sequences, only a subset of strains could be compared. Future studies including additional complete genomes from different countries and continents would allow for more robust phylogenetic analyses. The study did not analyze differences in viral genotypes between children with a single B19V infection and those with co-infections. Therefore, the potential influence of co-infections on the disease phenotype cannot be excluded.

Author Contributions

The authors E.G., I.D., E.L. and M.C. contributed to: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, writing. A.M.: software, visualization. T.G., C.C., D.H., S.V. and D.P.: resources, data curation. C.A.: validation. M.E. and G.G.: writing, supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Aristotle University of Thessaloniki (protocol code 230/2025, approved date: 6 June 2025) for studies involving humans. All participants were informed about the purpose of the research and consented to participate. Anonymity and confidentiality were ensured throughout the process.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are not publicly available due to privacy concerns. They are available upon request from the corresponding author, subject to ethical approval.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| IgM | Immunoglobulin M |

| IgG | Immunoglobulin G |

| NS1 | Non-structural protein 1 |

| VP1 | Capsid protein 1 |

| VP2 | Capsid protein 2 |

| ORF | Open Reading Frame |

References

- Luo, Y.; Qiu, J. Human parvovirus B19: A mechanistic overview of infection and DNA replication. Future Virol. 2015, 10, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Frea, S.; Pidello, S.; Bovolo, V.; Iacovino, C.; Franco, E.; Pinneri, F.; Galluzzo, A.; Volpe, A.; Visconti, M.; Peirone, A.; et al. Prognostic incremental role of right ventricular function in acute decompensation of advanced chronic heart failure. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2016, 18, 564–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bock, C.T.; Klingel, K.; Kandolf, R. Human parvovirus B19-associated myocarditis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 362, 1248–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, H.; Qiu, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, W.; Cui, A.; Li, X. The epidemiological and genetic characteristics of human parvovirus B19 in patients with febrile rash illnesses in China. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 15913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gu, J. fastp: An ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, i884–i890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H. Minimap2: Pairwise alignment for nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, 3094–3100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okonechnikov, K.; Conesa, A.; García-Alcalde, F. Qualimap 2: Advanced multi-sample quality control for high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics 2016, 32, 292–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoh, K.; Standley, D.M. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: Improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013, 30, 772–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minh, B.Q.; Schmidt, H.A.; Chernomor, O.; Schrempf, D.; Woodhams, M.D.; Von Haeseler, A.; Lanfear, R. IQ-TREE 2: New models and efficient methods for phylogenetic inference in the genomic era. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2020, 37, 1530–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letunic, I.; Bork, P. Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) v6: Recent updates to the phylogenetic tree display and annotation tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, W78–W82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). Outbreak of Parvovirus B19-Associated Pediatric Myocarditis in Italy—2024; ECDC: Solna, Sweden, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Bloise, S.; Cocchi, E.; Mambelli, L.; Radice, C.; Marchetti, F. Parvovirus B19 infection in children: A comprehensive review of clinical manifestations and management. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2024, 50, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hoelzle, L.E. Immunopathogenesis of myocarditis: What can we learn from animal models? Cardiol. Young 2020, 30, 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.Y.; Chung, Y.H.; Shi, Y.F.; Tzang, B.S.; Hsu, T.C. The VP1 unique region of human parvovirus B19 and human bocavirus induce lung injury in naïve Balb/c mice. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0202667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ponikowski, P.; Voors, A.A.; Anker, S.D.; Bueno, H.; Cleland, J.G.; Coats, A.J.; Falk, V.; González-Juanatey, J.R.; Harjola, V.P.; Jankowska, E.A.; et al. ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: The Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2016, 18, 891–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, J.; Söderlund-Venermo, M.; Young, N.S. Human Parvoviruses. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2017, 30, 43–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Romero-Cordero, S.; Noguera-Julian, A.; Cardellach, F.; Fortuny, C.; Morén, C. Mitochondrial changes associated with viral infectious diseases in the paediatric population. Rev. Med. Virol. 2021, 31, e2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zakrzewska, K.; Arvia, R.; Bua, G.; Margheri, F.; Gallinella, G. Parvovirus B19: Insights and implication for pathogenesis, prevention and therapy. Asp. Mol. Med. 2023, 1, 100007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjalmarsson, C.; Liljeqvist, J.Å.; Lindh, M.; Karason, K.; Bollano, E.; Oldfors, A.; Andersson, B. Parvovirus B19 in Endomyocardial Biopsy of Patients With Idiopathic Dilated Cardiomyopathy: Foe or Bystander? J. Card. Fail. 2019, 25, 60–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butler, O.; Raisi-Estabragh, Z.; Han, Y.; Frenz, A.K.; Harz, C.; Kelle, S.; Schulz-Menger, J.; Michel, A.; Kim, J. Epidemiology of myocarditis following COVID-19 or influenza and use of diagnostic assessments. Open Heart 2024, 11, e002947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callon, D.; Berri, F.; Lebreil, A.-L.; Fornès, P.; Andreoletti, L. Coinfection of Parvovirus B19 with Influenza A/H1N1 Causes Fulminant Myocarditis and Pneumonia. An Autopsy Case Report. Pathogens 2021, 10, 958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühl, U.; Pauschinger, M.; Noutsias, M.; Seeberg, B.; Bock, T.; Lassner, D.; Poller, W.; Kandolf, R.; Schultheiss, H.-P. High prevalence of viral genomes and multiple viral infections in the myocardium of adults with “idiopathic” left ventricular dysfunction. Circulation 2005, 111, 887–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolfvenstam, T. Human Parvovirus B19: Studies on the Pathogenesis of Infection. Ph.D. Thesis, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden, 2001. Available online: https://openarchive.ki.se/articles/thesis/Human_parvovirus_B19_studies_on_the_pathogenesis_of_infection/26895430?file=48936499 (accessed on 10 January 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Hellenic Society for Microbiology. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.