Abstract

Malassezia spp. has been recognized among neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) patients’ commensals and pathogens, accounting for a significant number of invasive fungal infections. The Random Amplified Polymorphic DNA (RAPD) may be used for Malassezia spp. strains typing from clinical isolates, demonstrating high resolution and specificity. Herein, we propose a retrospective analysis of Malassezia spp. isolates, aiming to investigate their identity and transmission pathways. Moreover, we documented Malassezia spp. prevalence within the University Hospital Policlinico of Catania, Italy. The analysis collected a total number of 16 M. pachydermatis and categorized them into four different clusters, hypothesizing a horizontal transmission. Although the essential role of microbiological sample cultures, our data suggested further environmental surveillance protocols to prevent NICU patients’ colonization due to the Malassezia spp. persistence and adhesion within healthcare surfaces.

1. Introduction

Yeast species are recognized as the most important aetiological agent of fungal infections among critical patients, especially regarding intensive care units (ICU) [1]. ICU patients have significant risk factors, such as prolonged corticosteroid therapies and length of stay, central venous catheters, and exposure to broad-spectrum antibiotics (e.g., third-generation cephalosporins) [1]. These risk factors are emphasized among neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) patients, including parenteral nutrition, prematurity, immunological impairments, and histamine-receptor antagonist administration [2,3].

Moreover, preterm birth (<1500 g), surgery, endotracheal external devices, low birth weight, and gestational age of less than 32 weeks contribute to extensive fungal colonization and potential invasive infections [3].

Literature documented invasive fungal infection epidemiology among NICUs, reporting Candida spp. and Malassezia spp. as the main pathogens [4,5,6,7,8,9]. On one hand, Candida spp. has a consolidated role among the fungal aetiological agents, accounting for well-known morbidity percentages and hospital settings diffusion [4,5,6,7]. On the other hand, Malassezia spp. infection rates and epidemiology may have been underestimated during the past decades. Both these fungal genera usually integrate the human microbiota, occasionally expressing their opportunistic attitude among fragile patients [4,5,6,7,8,9]. Despite their conventional presence within the skin and/or mucosal microbiota, Malassezia spp. and Candida spp. have been identified in the case of bloodstream or deep-seated fungal infections. Some studies revealed that Malassezia spp. invasive infections are sometimes more prevalent (2.1%) than candidaemia episodes (1.4%) within NICU settings [9]. The same scientific data demonstrated the presence of Malassezia spp. on NICU surfaces and healthcare personnel’s hands, along with blood culture isolation [10].

After the first recognition of Malassezia spp. as a fungemia causative yeast (1981) [11], colonization surveillance protocols have been applied to demonstrate this microorganism’s presence within NICU patients reporting parenteral nutrition or external venous devices [12,13]. Consequently, cessation of intravenous lipid nutrition and catheter removal are the best clinical practice in managing Malassezia spp.—invasive infections, together with evidence-based treatments due to underestimated infection rates [14]. Unfortunately, most Malassezia species often require a specific lipid source to grow, contributing to difficult isolation within laboratory diagnostic workflows. According to this assumption, some diagnostic protocols include lipid-enriched culture media (e.g., Dixon agar) or direct molecular investigations on biological samples [15].

Malassezia furfur and Malassezia pachydermatis represent the most common isolated species in the case of systemic infections. Despite M. furfur being commonly reported as a human commensal and pathogen, M. pachydermatis first emerged from animal sources [16]. This species has not colonized neonates since the early weeks after the preterm birth, but its colonization may be related to neonates’ closeness with personnel or relatives reporting animals’ contacts [16].

Molecular methods demonstrated high sensitivity and negative predictive values in diagnosing severe fungal infections caused by different aetiological agents [17,18].

Furthermore, M. pachydermatis’ non-lipid-dependent nature simplifies isolation procedures, allowing molecular assay usage on grown colonies [19]. This species often persists on incubator surfaces and human hands after conventional cleansing protocols [20]. Despite the recent refinement of sequencing analysis techniques, typing methods mainly involved the PCR Random Amplified Polymorphic DNA (PCR-RAPD), a fingerprinting method extensively used to study M. pachydermatis strains’ homologies or differences [21,22].

Herein, we propose a retrospective analysis of Malassezia spp. isolates, aiming to investigate M. pachydermatis identity through PCR-RAPD and demonstrate a potential homogeneous transmission pathway for this species. Another fundamental purpose was to integrate scientific data about Malassezia spp. epidemiology within critical healthcare settings, documenting its prevalence in our hospital.

2. Materials and Methods

A one-year (January 2021–January 2022) retrospective analysis included all the M. pachydermatis strains isolated from NICU patients from the University Hospital Policlinico of Catania. We decided to focus our attention on that specific period because it documented an overall increase in opportunistic infections within our hospital.

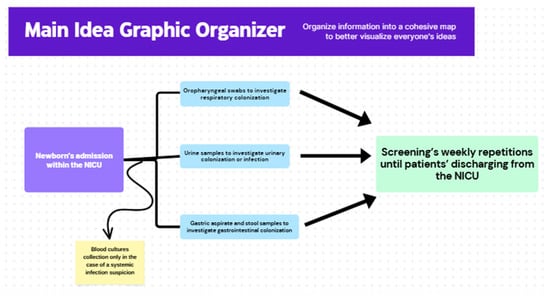

The isolates emerged during a routine surveillance protocol, including urine, oropharyngeal swabs, stool samples, and gastric aspirates. Clinicians implemented gastrointestinal surveillance procedures through gastric aspirates according to previously published scientific data [22]. Despite the invasive attitude of these samples’ collection, they demonstrated a sensitivity higher than rectal swabs and reflected the upper gastrointestinal tract, unlike stool samples [23]. Blood cultures integrated the microbiological diagnostic confirmation only after clinicians’ evaluation of a systemic infection’s clinical suspicion. All these surveillance procedures were applied due to previous Malassezia spp. fungemia cases within preterm newborns. The analysis did not directly involve human beings, focusing only on microbial strains from their clinical isolates. Furthermore, the study did not require supplementary biological samples. We analyzed clinical strains from surveillance specimens after the conventional diagnostic routine. On the premise of these assumptions, an ethical committee statement was not necessary.

Figure 1 describes the applied surveillance protocol furnishing the analyzed clinical isolates.

Figure 1.

Summary of the routine surveillance protocol that furnished clinical samples and M. pachydermatis isolates for experimental analysis.

2.1. Culture and Identification

Although they have a non-lipid-dependent attitude, all the isolates grew on a Malassezia (Dixon’s) Selective Agar (Vakutest Kima, Arzergrande, Italy). All the isolates were identified through mass spectrometry from the colonies’ direct spots. We adopted the MALDI Biotyper® Sirius System (Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA) technology, basing the identification on the MBT IVD Library (June 2021 Doc. No. 5023016).

2.2. Extraction Protocols

The molecular typing included all the identified isolates along with the M. pachydermatis ATCC 14522 control strain. We applied ultra-pure water washing and SET buffer (20 mM Tris pH 8, 30 mM EDTA, 80 mM NaCl) dilution on grown Malassezia spp. cells according to previous documented extraction protocols [24]. The extracted nucleic acid underwent a dilution with 100 µL of 10 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, and 1 mM EDTA containing 20 µg/mL of RNAse A [24]. Finally, an automated extraction protocol through the Nuclisens Easymag (bioMérieux Italia, Bagno a Ripoli, Firenze, Italy) was utilized to obtain the fungal DNA according to the manufacturer’s instructions [25].

2.3. PCR Random Amplified Polymorphic DNA (PCR-RAPD)

The extraction processes gathered a DNA concentration equal to 25 ng. The subsequent amplification phase used the VeritiTM Thermocycler (Applied Biosystems, ThermoScientific, Waltham, MA, USA), which was set according to Williams et al.’s previous investigations [23,24]. We integrated the following primers’ sequences: OPA02: 5′-TGCCGAGCTG-3′; OPA04: 5′-AATCGGGCTG-3′; P3: 5′-GTAGACCCGT-3′ [26]. The amplified genomes were placed into an agarose gel (1.8%) with TBE O.5X (54 g/L Tris Base, 27.5 g of boric acid, and Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid 0.5 mM, with a definitive pH = 8). The same TBE solution was used to perform an electrophoresis (1 h, 100 V). We compared the DNA fragments’ length to a 50 bp marker (New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA, USA). We reproduced 3 times all the PCR cycles to verify the RAPD-PCR reproducibility and ensure a sufficient number in validating the entire process.

The definitive analysis was performed through a transilluminator (Uvitec, Cambridge, UK) and sequence analyzer software (Ailunce HD2, v1.14, Ailunce, Shenzhen, China). The genetic distance between the different samples was evaluated through a binary matrix, indicating 1 for the presence of specific reproducible bands and 0 for their absence. We elaborated a dendrogram using the Jaccard index and Sneath and Sokal’s UPGMA (Unweighted Pair Group Method with Arithmetic Average) method.

3. Results

Among 264 microbiological surveillance samples from 88 NICU patients, 46 (17.4%) positive cultures emerged. Specifically, 36 results (78.2.%) reported Malassezia spp. isolation. Otherwise, only 10 positive cultures (3.8%) revealed Candida spp. Among Candida spp. positive results, we identified five (50%) Candida albicans, four (40%) Candida parapsilosis, and one (10%) Candida glabrata strain. All these isolates represented respiratory or gastrointestinal colonization. As regards Malassezia spp. positive cultures, we identified 20 (55.5%) M. furfur and 16 (44.4%) M. pachydermatis strains. M. furfur reported three blood culture-positive results, while M. pachydermatis did not cause systemic infections.

Focusing on M. pachydermatis isolates, the analysis collected a total of 16 M. pachydermatis isolates from 11 patients (Table 1). Four isolates (1, 2, 3, 4) belonged to patient 1, while two isolates were derived from patient 8 (strains 11, 12) and patient 10 (strains 14, 15). The isolates emerged from urine, stool, and gastric aspirate samples, representing colonization episodes.

Table 1.

Details on patients and biological samples for all the included M. pachydermatis strains.

Specifically, the microscopic examination did not reveal any neutrophils along with the absence of clinical urinary symptoms, while stool and gastric aspirate samples documented a gastrointestinal colonization.

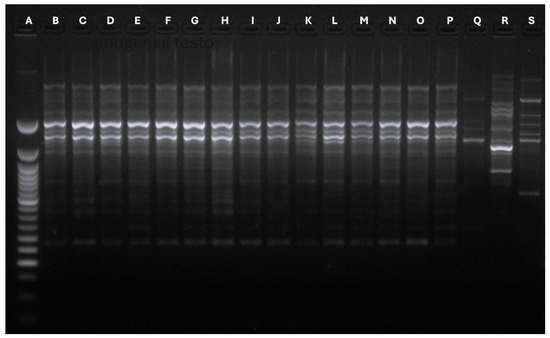

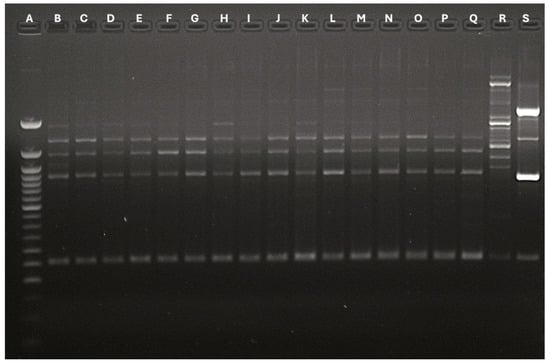

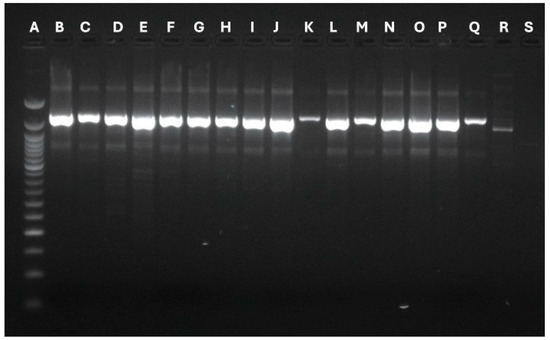

The primer’s usage allowed the revelation of different bands, whose number and type concurred to define polymorphisms and genetic profiles. The OPA02 primer produced a different band number depending on the analyzed strains. Specifically, isolates 16 gathered 2 bands, strains from 1 to 9 obtained 6 bands, and strains from 10 to 15 collected 7 bands. All the isolates belonging to patient 1 (1, 2, 3, 4) demonstrated the same genetic identity. Patients 2 to 7 reported a single M. pachydermatis isolate, which had identical genetic profiles. On the other hand, the single isolate belonging to patient 11 reported a specific polymorphism profile. The OPA04 primer registered two different polymorphisms (5 bands and 6 bands). This analysis identified the same genetic profiles for all the strains belonging to patient 1 and the strains deriving from patient 4. Finally, the P3 primer produced two bands for each strain, identifying a single polymorphism for all the involved microorganisms. Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4 show graphical details about the reported genetic profiles through the different used primers.

Figure 2.

Graphical details about the genetic profiles gathered through the OPA02 primer. A: Ladder 50 bp; B: Strain 1-Stool; C: Strain 2-Urine; D: Strain 3-Urine; E: Strain 4: Stool; F: Strain 5-Stool; G: Strain 6-Stool; H: Strain 7-Stool; I: Strain 8-Stool; J: Strain 9: Urine; K: Strain 10-Urine; L: Strain 11-Stool; M: Strain 12-Gastric aspirate; N: Strain 13: Stool; O: Strain 14: Stool; P: Strain 15-Urine; Q: Strain 16-Urine; R: Malassezia globosa Control strain; S: ATCC Malassezia pachydermatis CD69.

Figure 3.

Graphical details about the genetic profiles gathered through the OPA04 primer. A: Ladder 50 bp; B: Strain 1-Stool; C: Strain 2-Urine; D: Strain 3-Urine; E: Strain 4: Stool; F: Strain 5-Stool; G: Strain 6-Stool; H: Strain 7-Stool; I: Strain 8-Stool; J: Strain 9: Urine; K: Strain 10-Urine; L: Strain 11-Stool; M: Strain 12-Gastric aspirate; N: Strain 13: Stool; O: Strain 14: Stool; P: Strain 15-Urine; Q: Strain 16-Urine; R: Malassezia globosa Control strain; S: ATCC Malassezia pachydermatis CD69.

Figure 4.

Graphical details about the genetic profiles gathered through the P3 primer. A: Ladder 50 bp; B: Strain 1-Stool; C: Strain 2-Urine; D: Strain 3-Urine; E: Strain 4: Stool; F: Strain 5-Stool; G: Strain 6-Stool; H: Strain 7-Stool; I: Strain 8-Stool; J: Strain 9: Urine; K: Strain 10-Urine; L: Strain 11-Stool; M: Strain 12-Gastric aspirate; N: Strain 13: Stool; O: Strain 14: Stool; P: Strain 15-Urine; Q: Strain 16-Urine; R: Malassezia globosa Control strain; S: ATCC Malassezia pachydermatis CD69.

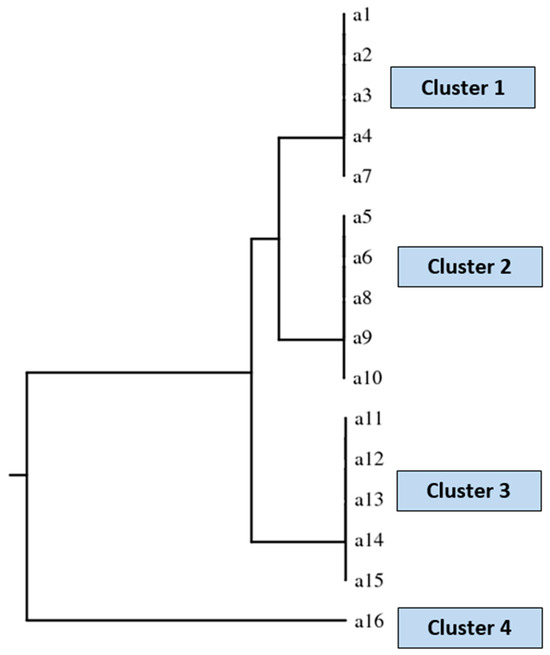

The polymorphism analysis contributed to defining four Malassezia spp. clusters, along with a specific isolation period within the NICU setting. A dendrogram (Figure 5) described four clusters for the analyzed M. pachydermatis strains (Figure 2).

Figure 5.

Dendrogram describing the identified four clusters. Cluster 1 includes strains number 1, 2, 3, 4 (Patient 1), and 7 (Patient 4). Cluster 2 contains strains number 5 (Patient 2), 6 (Patient 3), 8 (Patient 5), 9 (Patient 6), and 10 (Patient 7). Cluster 3 includes strains number 11 and 12 (Patient 8), 13 (Patient 9), and 14 and 15 (Patient 10). Finally, cluster 4 includes strain number 16 (Patient 11).

4. Discussion

The spread of Malassezia spp. in colonization and infection episodes poses a significant healthcare challenge among ICU patients, particularly neonates [24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33]. While M. furfur is frequently isolated, there have been a few documented cases of systemic infections caused by M. pachydermatis in intensive care patients. The limited pathogenic role of M. pachydermatis suggests that these infection cases depend heavily on the patients’ fragile conditions. According to our data, Malassezia spp. was the main colonizing fungal species during the study period. We focused our analysis on M. pachydermatis to investigate its potential modes of transmission within a critical hospital environment.

Previous studies have described various molecular methods for typing Malassezia spp. RAPD-PCR (Random Amplified Polymorphic DNA-Polymerase Chain Reaction) demonstrated a discrete discriminatory power, distinguishing strain groups with low-cost and slow procedures. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) proposed standardized protocols and guaranteed a significant identification power. Unfortunately, this technique requires dedicated personnel, high costs, and prolonged procedures [25]. Furthermore, fingerprinting models represented a historical and functional tool in typing Malassezia spp. strains, furnishing elevated reproducibility rates. This old procedure is regrettably marked by a relevant technical complexity when compared to the RAPD [26]. On the other hand, modern whole-genome sequencing (WGS) techniques revealed the maximum analysis quality, identifying clonal relationships and phylogenetic features at high confidence levels [27]. Moreover, WGS produces wide-spectrum lineage-specific details and may discover new genes or mobile elements related to precise microorganisms’ characteristics [27]. Despite the high precision and specificity in defining Malassezia spp. genome and polymorphisms, the significant lipid content within this yeast’s cell wall can lead to enzyme inhibition during extraction and interfere with DNA purification. Additionally, the genomic complexity can create artifacts due to repetitive sequences and variable regions. These characteristics make it challenging to standardize sequencing methodologies for Malassezia spp. [28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36].

We employed the RAPD method to confirm the genetic identity of all included strains, as it offers more standardized protocols and requires less expertise in a diagnostic laboratory routine. This technology demonstrated significant capabilities for strain discrimination and identification, defining specific clusters based on identified polymorphisms and precise isolation periods within the analyzed hospital ward.

Specifically, four heterogeneous clusters emerged during different isolation periods: cluster 1 included isolates from May 2021 to June 2021; cluster 2 comprised strains from June 2021 to September 2021; cluster 3 contained isolates from October 2021 to November 2021; and cluster 4 included isolates from January 2022.

Despite the separation of clusters, all the isolates were likely transmitted horizontally via healthcare personnel’s hands, which had previous contact with animals. We hypothesized that such transmission may relate to M. pachydermatis’ animal origin, similar to M. furfur, whose colonization in neonates may result from exposure to vaginal mycobiome during natural deliveries. We could not confirm this hypothesis and aim to further investigate Malassezia spp. strains within the same hospital unit in the coming months.

Additionally, the potential role of transmission during breastfeeding and contact with neonates’ relatives may be examined in future studies. Previous data have indicated a potential genomic link between Malassezia spp. isolated from neonates and their mothers during the intensive care recovery period, emphasizing the necessity of maternal care [37].

Regardless of the identified species, our experimental analysis underscores the importance of implementing surveillance strategies in critical neonatal settings. Unfortunately, the study had a limited sample size and included few pathogenic species, necessitating future expansion to involve more patients and isolates of Malassezia spp. Multi-center studies, including prospective analysis, may be planned in the near future to confirm our hypotheses. Similar studies should probably include hand-sampling and environmental surveillance procedures to confirm the primary Malassezia spp. sources.

Despite noted colonization by Malassezia spp., the NICU patients included in this study did not develop any systemic infections, likely due to prompt prophylactic measures and appropriate patient management within the healthcare unit. The isolation of colonizing species has led to increased sanitization of surfaces and healthcare workers’ hands. Furthermore, positive surveillance cultures have led to a systematic and planned distribution of further surveillance procedures through fungal cultures within the NICU.

Systemic infections documented were attributed to M. furfur, prompting considerations for future typing analyses of this species, which demonstrates significant pathogenic relevance in critical human hosts. Furthermore, scientific data indicate M. pachydermatis’ ability to survive on surfaces inside newborn incubators, highlighting the importance of controlling the entire neonatal recovery environment [28,29,34,35,36,37,38,39].

Although microbiological cultures from biological samples play a crucial role, the above-mentioned studies have led to hypotheses concerning the implementation of environmental surveillance protocols to prevent NICU patients’ colonization from personnel contacts or surface adherence.

The colonization of environmental surfaces and human anatomical regions by Malassezia spp. is associated with potential infection cases among patients with prolonged hospital stays.

These considerations may prompt further investigations into the cost-effectiveness of microbiological surveillance. Future analyses could explore economic aspects such as complications from severe fungal infections and the associated costs of prolonged hospitalization.

5. Conclusions

Malassezia spp. revealed surviving and colonizing attitudes within healthcare-related environments, potentially causing severe infections. Consequently, surveillance protocols should always include Malassezia spp. specific isolation conditions. However, this fungal genus requires specific growth conditions and nutritive elements. Our findings underscore that specific infection-control procedures may prevent and contain Malassezia infections, documenting this microorganism’s prevalence and presence within critical settings. Appropriate microbiological media and incubation periods are essential due to the identification difficulties associated with this particular yeast [39]. Once identification workflows for Malassezia spp. are established, microbiological surveillance may become a fundamental strategy in documenting fungal colonization and possible infection outcomes. Punctual surveillance protocols may enrich the overall epidemiological knowledge about specific yeast species, enhancing their potential pathogenic role within critical hospital settings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.T., M.C., C.L.M. and P.M.L.B.; methodology, L.T. and M.C.; investigation, M.C.; data curation, L.T., M.C. and A.M.; writing—original draft preparation, L.T. and M.C.; writing—review and editing, L.T. and M.C.; supervision, P.M.L.B. and G.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

We analyzed clinical strains from surveillance specimens after the conventional diagnostic routine. On the premise of these assumptions, an ethical committee statement was not necessary.

Informed Consent Statement

In compliance with GDPR (EU 2016/679) and Italian Legislative Decree 196/2003 (as amended by Legislative Decree 101/2018), irreversibly anonymized biological samples are not considered personal data, and informed consent is not required.

Data Availability Statement

All the gathered data are included within the manuscript. The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hoenigl, M.; Enoch, D.A.; Wichmann, D.; Wyncoll, D.; Cortegiani, A. Exploring European Consensus About the Remaining Treatment Challenges and Subsequent Opportunities to Improve the Management of Invasive Fungal Infection (IFI) in the Intensive Care Unit. Mycopathologia 2024, 189, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dermitzaki, N.; Baltogianni, M.; Tsekoura, E.; Giapros, V. Invasive Candida Infections in Neonatal Intensive Care Units: Risk Factors and New Insights in Prevention. Pathogens 2024, 13, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Montagna, M.T.; Lovero, G.; De Giglio, O.; Iatta, R.; Caggiano, G.; Montagna, O.; Laforgia, N.; AURORA Project Group. Invasive fungal infections in neonatal intensive care units of Southern Italy: A multicentre regional active surveillance (AURORA project). J. Prev. Med. Hyg. 2010, 51, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Devlin, R.K. Invasive fungal infections caused by Candida and Malassezia species in the neonatal intensive care unit. Adv. Neonatal Care 2006, 6, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horn, D.L.; Neofytos, D.; Anaissie, E.J.; Fishman, J.A.; Steinbach, W.J.; Olyaei, A.J.; Marr, K.A.; Pfaller, M.A.; Chang, C.; Webster, K.M. Epidemiology and outcomes of candidemia in 2019 patients: Data from the prospective antifungal therapy alliance registry. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2009, 48, 1695–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caggiano, G.; Iatta, R.; Laneve, A.; Manca, F.; Montagna, M.T. Observational study on candidaemia at a university hospital in southern Italy from 1998 to 2004. Mycoses 2008, 51, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveri, S.; Trovato, L.; Betta, P.; Romeo, M.G.; Nicoletti, G. Malassezia furfur fungaemia in a neonatal patient detected by lysis-centrifugation blood culture method: First case reported in Italy. Mycoses 2011, 54, e638–e640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teoh, Z.; Mortensen, J.; Schaffzin, J.K. Invasive Malassezia pachydermatis Infection in an 8-Year-Old Child on Lipid Parenteral Nutrition. Case Rep. Infect. Dis. 2022, 2022, 8636582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Jin, F.; Ni, F.; Xu, Y.; Lu, Y.; Xia, W. Clinical data analysis of 86 patients with invasive infections caused by Malassezia furfur from a tertiary medical center and 37 studies. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1079535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iatta, R.; Cafarchia, C.; Cuna, T.; Montagna, O.; Laforgi, N.; Gentile, O.; Rizzo, A.; Boekhout, T.; Otranto, D.; Montagna, M.T. Bloodstream infections by Malassezia and Candida species in critical care patients. Med. Mycol. 2014, 52, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redline, R.W.; Dahms, B.B. Malassezia pulmonary vasculitis in an infant on long-term Intralipid therapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 1981, 305, 1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaitanis, G.; Magiatis, P.; Hantschke, M.; Bassukas, I.D.; Velegraki, A. The Malassezia genus in skin and systemic diseases. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2012, 25, 106–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ahtonen, P.; Lehtonen, O.P.; Kero, P.; Tunnela, E.; Havu, V. Malassezia furfur colonization of neonates in an intensive care unit. Mycoses 1990, 33, 543–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, P.; Chakrabarti, A.; Singhi, S.; Kumar, P.; Honnavar, P.; Rudramurthy, S.M. Skin Colonization by Malassezia spp. in hospitalized neonates and infants in a tertiary care centre in North India. Mycopathologia 2014, 178, 267–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tashiro, M.; Takazono, T.; Izumikawa, K. Invasive Malassezia Infections. Med. Mycol. J. 2023, 64, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gholami, M.; Mokhtari, F.; Mohammadi, R. Identification of Malassezia species using direct PCR- sequencing on clinical samples from patients with pityriasis versicolor and seborrheic dermatitis. Curr. Med. Mycol. 2020, 6, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gupta, A.K.; Boekhout, T.; Theelen, B.; Summerbell, R.; Batra, R. Identification and typing of Malassezia species by amplified fragment length polymorphism and sequence analyses of the internal transcribed spacer and large-subunit regions of ribosomal DNA. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2004, 42, 4253–4260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Trovato, L.; Calvo, M.; Palermo, C.I.; Scalia, G. The Role of Quantitative Real-Time PCR in the Invasive Pulmonary Aspergillosis Diagnosis: A Retrospective Study. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Trovato, L.; Calvo, M.; Palermo, C.I.; Valenti, M.R.; Scalia, G. The Role of the OLM CandID Real-Time PCR in the Invasive Candidiasis Diagnostic Surveillance in Intensive Care Unit Patients. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ilahi, A.; Hadrich, I.; Goudjil, S.; Kongolo, G.; Chazal, C.; Léké, A.; Ayadi, A.; Chouaki, T.; Ranque, S. Molecular epidemiology of a Malassezia pachydermatis neonatal unit outbreak. Med. Mycol. 2018, 56, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duarte, E.R.; Hamdan, J.S. RAPD differentiation of Malassezia spp. from cattle, dogs and humans. Mycoses 2010, 53, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, S.; Qian, Y.; Wang, Q.; Ling, Y.; Hu, Q. Evaluation of the diagnostic value of gastric juice aspirate culture for early-onset sepsis in newborns 28–35 weeks’ gestation. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2020, 98, 115115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, H.J.; Zhang, G.Q.; Zhang, Q.; Shakya, S.; Li, Z.Y. Probiotics Prevent Candida Colonization and Invasive Fungal Sepsis in Preterm Neonates: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Pediatr. Neonatol. 2017, 58, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gandra, R.F.; Simão, R.C.; Matsumoto, F.E.; da Silva, B.C.; Ruiz, L.S.; da Silva, E.G.; Gambale, W.; Paula, C.R. Genotyping by RAPD-PCR analyses of Malassezia furfur strains from pityriasis versicolor and seborrhoeic dermatitis patients. Mycopathologia 2006, 162, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gil-Lamaignere, C.; Roilides, E.; Hacker, J.; Müller, F.M. Molecular typing for fungi—A critical review of the possibilities and limitations of currently and future methods. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2003, 9, 172–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theelen, B.; Silvestri, M.; Guého, E.; van Belkum, A.; Boekhout, T. Identification and typing of Malassezia yeasts using amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP), random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) and denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE). FEMS Yeast Res. 2001, 1, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, G.; Zhao, H.; Li, C.; Rajapakse, M.P.; Wong, W.C.; Xu, J.; Saunders, C.W.; Reeder, N.L.; Reilman, R.A.; Scheynius, A.; et al. Genus-Wide Comparative Genomics of Malassezia Delineates Its Phylogeny, Physiology, and Niche Adaptation on Human Skin. PLoS Genet. 2015, 11, e1005614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hasan, R.; Rahman, M.A.; Kabir, A.H.; Haydar, F.A.; Reza, M.A. RAPD-markers assisted genetic diversity analysis and Bt-Cry1Ac gene identification in eggplant (Solanum melongena L.). Plant Trends 2023, 1, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.G.K.; Kubelik, A.R.; Livak, K.J.; Rafalski, J.A.; Tingey, S.V. DNA polimorphisms amplified by arbitrary primers are useful as genetic markers. Nucleic Acid Res. 1990, 18, 6531–6535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.G.K.; Kubelik, A.R.; Livak, K.J.; Rafalski, J.A.; Tingey, S.V. Genetic Analysis with RAPD Markers, in More Gene Manipulations in Fungi; Academic Press Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1990; pp. 431–439. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Sweih, N.; Ahmad, S.; Joseph, L.; Khan, S.; Khan, Z. Malassezia pachydermatis fungemia in a preterm neonate resistant to fluconazole and flucytosine. Med. Mycol. Case Rep. 2014, 5, 9–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chryssanthou, E.; Broberger, U.; Petrini, B. Malassezia pachydermatis fungaemia in a neonatal intensive care unit. Acta Paediatr. 2001, 90, 323–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, M.; Cho, Y.J.; Lee, Y.W.; Jung, W.H. Whole genome sequencing analysis of the cutaneous pathogenic yeast Malassezia restricta and identification of the major lipase expressed on the scalp of patients with dandruff. Mycoses 2017, 60, 188–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Worasilchai, N.; Permpalung, N.; Chindamporn, A. High-resolution melting analysis: A novel approach for clade differentiation in Pythium insidiosum and pythiosis. Med. Mycol. 2018, 56, 868–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.J.; Miller, H.L.; Watkins, N.; Arduino, M.J.; Ashford, D.A.; Midgley, G.; Aguero, S.M.; Pinto-Powell, R.; von Reyn, C.F.; Edwards, W.; et al. An epidemic of Malassezia pachydermatis in an intensive care nursery associated with colonization of health care workers’ pet dogs. N. Engl. J. Med. 1998, 338, 706–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mpakosi, A.; Cholevas, V.; Meletiadis, J.; Theodoraki, M.; Sokou, R. Neonatal Fungemia by Non-Candida Rare Opportunistic Yeasts: A Systematic Review of Literature. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zomorodian, K.; Naderibeni, M.; Mirhendi, H.; Razavi Nejad, M.; Saneian, S.M.; Mahmoodi, M.; Kharazi, M.; Khodadadi, H.; Pakshir, K.; Motamedi, M. Molecular Identification of Malassezia species isolated from neonates hospitalized in neonatal intensive care units and their mothers. Curr. Med. Mycol. 2021, 7, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Belkum, A.; Boekhout, T.; Bosboom, R. Monitoring spread of Malassezia infections in a neonatal intensive care unit by PCR- mediated genetic typing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1994, 32, 2528–2532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petruccelli, R.; Cosio, T.; Camicia, V.; Fiorilla, C.; Gaziano, R.; D’Agostini, C. Malassezia furfur bloodstream infection: Still a diagnostic challenge in clinical practice. Med. Mycol. Case Rep. 2024, 45, 100657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Hellenic Society for Microbiology. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).