Abstract

The European catfish (Silurus glanis, Linnaeus 1758), commonly known as the wels catfish, is one of the largest freshwater fish in Europe and an ecologically and economically important species in both natural ecosystems and aquaculture. Its broad native distribution, together with the rapid growth of farming practices, increases concerns about pathogen dissemination and their potential impact on biodiversity, animal health, and potential risks to human healthcare. This review is based on a structured literature search following PRISMA recommendations for narrative reviews and summarizes current knowledge on the main pathogen groups affecting S. glanis—viruses (ranaviruses, alloherpesviruses), bacteria (Aeromonas spp., Edwardsiella spp.), protozoan and metazoan parasites (Ichthyophthirius multifiliis, Thaparocleidus spp., Eustrongylides spp., Contracaecum larvae), and oomycetes (Saprolegnia spp., Branchiomyces spp.). Within the One Health approach, particular attention is given to zoonotic pathogens such as Aeromonas spp., Edwardsiella tarda, and helminths like Eustrongylides and Contracaecum, which may cause risks to human health through contaminated water or consumption of raw or undercooked fish. The review integrates findings from field surveys, regional case studies such as those from the Danube basin, and data from the authors’ doctoral research. Because the wels catfish is increasingly cultivated and serves as an apex predator in natural habitats, its effective disease management is critical for both aquaculture and wild populations, and also for the food chains at all. Strengthened surveillance, health monitoring, and biosecurity measures are essential preventing the introduction and spread of pathogens into new hosts and habitats. Through the underlining of major catfish pathogen groups, this review highlights key challenges within the One Health approach and underscores the need for integrated health monitoring, biosecurity, and environmental management strategies.

1. Introduction

The European catfish (Silurus glanis, Linnaeus 1758) ranks among the largest freshwater species in Europe and plays a key role in both natural ecosystems and aquaculture [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. In recent decades, farming of this species has grown steadily, supported by its rapid growth, broad environmental tolerance, and strong market demand [8]. Yet, with this expansion come serious challenges, particularly the threat of infectious diseases. Reports have documented outbreaks caused by all major groups of pathogens—viruses, bacteria, protozoan and metazoan parasites, as well as oomycetes—with some cases resulting in heavy stock losses [9]. Historically, in traditional low-density polyculture ponds, wels catfish were even considered beneficial because they preyed on weak or diseased fish, thereby helping to reduce the spread of infections among carp [10]. Modern intensive farming systems, however, whether high-density ponds or recirculating aquaculture facilities, create conditions that favor rapid pathogen transmission, making viral and bacterial diseases especially problematic [9].

S. glanis hosts an exceptionally diverse community of parasites, a reflection of both its wide geographic distribution and predatory feeding habits. Surveys across native and introduced ranges have identified numerous taxa, including protozoans, monogeneans, digenean trematodes, cestodes, nematodes, acanthocephalans, crustaceans, and oomycetes [11]. This diversity is not only of academic interest but also of practical concern, since some pathogens directly impact catfish populations while others may carry broader ecological or even public health implications. Certain bacteria and parasites of catfish, for instance, are opportunistic or zoonotic and may infect other animals or humans through water contact or consumption of fish [12].

The One Health approach provides an essential interdisciplinary framework. One Health recognizes that the health of humans, animals, and ecosystems are connected, and the disease prevention and management require collaboration across veterinary, environmental, and public health sectors. International bodies such as the World Health Organization (WHO), Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE or WOAH), and United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) promote the One Health framework through global strategies for zoonotic disease control, antimicrobial resistance mitigation, and ecosystem protection. At the regional level, the European Union (EU) has incorporated One Health principles into regulations governing aquaculture biosecurity, fish welfare, water quality, and trade. National legislations across Europe likewise require monitoring of aquatic animal diseases, responsible antimicrobial use, and environmental risk assessments—all integral components of the One Health concept.

For S. glanis, One Health is especially relevant because pathogen exchange can occur between wild fish, farmed stocks, invertebrate hosts, birds, and even humans in rare zoonotic cases. Managing the health of S. glanis is difficult because the species is exposed to a wide spectrum of pathogens. Its distribution—from natural rivers and lakes such as the Danube and its delta to artificial ponds and recirculating systems—creates multiple opportunities for infection. A thorough understanding of catfish pathogens is therefore critical for three main reasons: (1) Aquaculture—diseases can cause severe losses, and S. glanis often cohabits with other species, facilitating pathogen exchange. (2) Biodiversity—wild catfish may serve as reservoirs of infections that affect other fishes, while stocking or translocation can introduce novel pathogens into naïve ecosystems [13,14]. (3) Public health—although most catfish pathogens are not zoonotic, some bacteria and parasites may infect humans, especially through consumption of raw or undercooked fish, linking this issue to One Health concerns [15,16].

This review highlights the main pathogen groups reported in S. glanis: viruses, bacteria, oomycetes, and parasites (protozoans and helminths). For each, we outline representative species, associated diseases or pathological effects, diagnostic approaches, and implications for aquaculture and biodiversity. Emphasis is placed on recent research—more than 65% of the references are from the last five years (2021–2025)—and on findings from the species’ native range, such as studies from the Danube River, to provide ecological and epidemiological context. To strengthen the systematic approach, a bibliometric analysis of the available literature is included, highlighting: (1) geographic origin of studies, (2) the proportion conducted in natural vs. aquaculture settings, and (3) the number and diversity of pathogens documented in S. glanis. Furthermore, Materials and Methods and Discussion sections enhance scientific rigor and align the manuscript with recommended standards such as PRISMA guidelines [17] for structured reviews. Summary tables of key pathogens are included with a treatment options and corresponding references. By consolidating this information, we aim to support fish health specialists and researchers working in catfish culture and fisheries management, while identifying gaps that merit further study. Understanding the full spectrum of catfish pathogens is essential for effective disease management and for appreciating the role of S. glanis within aquatic health networks.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Search Strategy

A structured literature search was performed following PRISMA recommendations for narrative reviews [17]. Databases consulted included Web of Science, Scopus, PubMed, and Google Scholar, and author’s PhD thesis. Searches covered publications from 1980 to 2025 and used combinations of keywords such as “Silurus glanis”, “European catfish”, “wels catfish”, “pathogens”, “viruses”, “bacteria”, “parasites”, “helminths”, “oomycetes”, “aquaculture diseases”, and “One Health”. Search terms, platforms, and timeframes are summarized in Table 1, Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4. Titles and abstracts were screened independently by both authors using predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. All retrieved records were combined and duplicates were removed. Full texts considered potentially relevant were subsequently reviewed in detail by the same two authors. Disagreements at any stage were resolved through discussion until full consensus was achieved. No automation tools were used during any part of the Literature Search Strategy. In accordance with the Journal’s Recommendations more than 50% of the cited references are within the last 5 years (2021–2025). Findings on key pathogen groups are synthesized in summary tables (Tables 5–9) that include affected tissues, clinical signs, zoonotic potential, treatment, and corresponding references.

Table 1.

Keywords combinations and total number of results in Web of Science.

Table 2.

Keywords combinations and total number of results in Scopus.

Table 3.

Keywords combinations and total number of results in PubMed.

Table 4.

Keywords combinations and total number of results in Google Scholar.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Included sources met at least one of the following criteria: (1) Reported pathogens detected in S. glanis. (2) Described clinical signs, pathology, or epidemiology in wild or farmed catfish. (3) Examined One Health–related aspects such as zoonotic potential, environmental drivers, or biosecurity. (4) Provided molecular characterisation, distribution data, or experimental infection results. (5) Papers were published in peer-reviewed scientific journals. (6) Papers were published within the last five years (2021–2025).

Excluded criteria were: Reason (1) Studies lacking confirmed identification of pathogens. Reason (2) Reports unrelated to fish health or aquaculture. Reason (3) Literature without accessible methodological details. Reason (4) Papers were published in non-peer-reviewed journals. Reason (5) Papers were published before the last five years (2021–2025).

2.3. Compliance with the PRISMA Guidelines

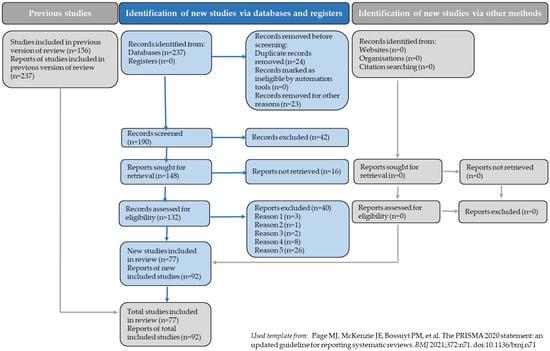

The review process complies fully with the PRISMA guidelines [17]. A completed PRISMA 2020 flow diagram is provided in the manuscript (Figure 1), illustrating all stages of record identification, screening, eligibility assessment, and inclusion. Because the figure reports the full numerical details, these numbers are not repeated here in the text. This review was not registered in a public repository.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram (used template from [17]).

2.4. Bibliometric Summary

Analysis of the literature indicates that approximately 60% of the studies originate from Europe, predominantly Central and Eastern regions—Hungary, Czech Republic, Bulgaria, Germany, etc. Around 25% come from Western Asia—Turkey and Iran, and the remaining 15% come from other regions including China. Roughly 55% of the studies were conducted in wild habitats and 45% in aquaculture ponds. Across all sources, more than 90 pathogens of different taxonomic groups have been recorded in S. glanis, highlighting a rich and complex disease landscape but some of the pathogens were mentioned only once as an incident finding or a susceptible species.

3. Results

3.1. Viral Pathogens

Reports of viral infections in S. glanis are relatively scarce, yet several are known to be highly virulent. An earlier review [18] observed that only a few finfish viruses significantly affect Siluriformes, notably a herpesvirus and two iridoviruses associated with disease in catfish. More recent studies confirm that knowledge of S. glanis virology is still limited. The main documented infections involve alloherpesviruses (family Alloherpesviridae) and ranaviruses (family Iridoviridae), while newer reports also describe papillomaviruses, circoviruses, and rhabdoviruses in this host [19,20,21,22,23].

3.1.1. Alloherpesviruses

Herpesviruses were among the earliest viruses identified in S. glanis. In the 1980s, a herpesvirus infection causing epidermal hyperplasia—commonly known as “fish pox,” with papilloma-like skin lesions—was documented in Hungary [24]. This condition, often referred to as sheatfish herpesvirus disease, typically produces proliferative lesions on the skin and fins. Although generally benign, such lesions can predispose fish to secondary infections. The suspected causative agent, likely an alloherpesvirus, could not be cultured at the time and remained poorly described. Decades later, molecular studies revealed a novel alloherpesvirus in farmed S. glanis displaying widespread carp pox-like skin lesions [22]. Partial sequencing confirmed it as a distinct member of the family Alloherpesviridae [20]. Phylogenetic analysis indicates that while it is related to other fish herpesviruses, it represents a unique lineage in catfish. This emerging virus, proposed as “Silurid herpesvirus,” highlights that S. glanis can harbor its own herpesvirus clade. Clinical cases in adults appear limited to benign skin tumors, but its effects on juvenile survival and latency within populations remain unresolved [25,26]. Ongoing monitoring is important, since new variants could evolve or spread, potentially reducing existing disease resistance in cultured stocks.

3.1.2. Iridoviruses

Systemic infections caused by iridoviruses represent a serious threat to both catfish hatcheries and wild populations. S. glanis is susceptible to certain ranaviruses (Iridoviridae) that induce acute hemorrhagic disease. The first reported outbreak occurred in Germany in 1988, when fry suffered mortality rates approaching 100% [27]. The isolated virus, later termed European sheatfish virus (ESV), proved highly virulent, killing fry within days of exposure through waterborne transmission [28]. Affected fingerlings displayed lethargy, loss of equilibrium, petechial skin hemorrhages, exophthalmia, and severe necrosis of internal organs [29]. Histopathological studies showed that ESV targets endothelial and hematopoietic tissues, leading to edema and hemorrhagic shock [28,30]. Older fish may survive infection but act as carriers, particularly when stressed or co-infected with bacteria [31].

A related ranavirus, European catfish virus (ECV), was detected in wild populations across Europe in the 1990s, with initial cases in France and Italy causing mass mortality in lakes where invasive black bullhead (Ameiurus melas) were abundant [32,33,34]. Although ESV and ECV were initially considered the same, genetic studies later distinguished them: differences in neurofilament protein genes and host range confirmed that they are separate strains [35]. Both belong to the amphibian-like ranavirus clade and are closely related to epizootic hematopoietic necrosis virus (EHNV) from Australia [36]. Full genome sequencing of ESV revealed approximately 136 putative genes and about 88% nucleotide identity to EHNV [36], while ECV is presumed to have a similarly large double-stranded DNA genome. These ranaviruses are now recognized as significant emerging pathogens of European catfish, spreading rapidly in warm-water conditions and causing high juvenile mortality, with the potential to infect other species such as bullheads [9]. Alarmingly, ECV was even identified in ornamental Pangasius shipments imported to South Korea [37]. Given their impact, strict biosecurity and the development of vaccines are strongly recommended to control ranavirus outbreaks in cultured and wild catfish.

3.1.3. Papillomaviruses

In addition to the high-mortality agents such as ranaviruses and herpesviruses, European catfish also harbor other viruses of interest. A recently described example is a papillomavirus named Silurus glanis papillomavirus 1 (SgPV1) [22]. This small circular DNA virus (~5.6 kb) was detected in skin lesions of farmed catfish that closely resembled those caused by herpesvirus infections [22,24]. Genomic analysis showed that SgPV1 is distinct from known mammalian papillomaviruses and has been proposed as the founding member of a new genus (Nunpapillomavirus) within the family Papillomaviridae [22,38]. Infected fish typically develop multiple benign papilloma-like growths on the skin. Although these tumors are non-lethal, they may interfere with respiration or osmoregulation and reduce marketability due to their appearance. The discovery of SgPV1 expands the known host range of papillomaviruses and demonstrates that S. glanis can be co-infected with multiple tumorigenic viruses (e.g., herpes- and papillomaviruses) [39]. Co-infections have already been documented, though the precise role of each virus in lesion formation remains uncertain.

3.1.4. Circoviruses

Circoviruses represent another emerging group of fish pathogens. A circovirus later named Silurus glanis circovirus (CfCV) was first reported in adult European catfish from Lake Balaton, Hungary, around 2011 [40]. Its complete genome (~1.97 kb) was sequenced and found to encode the characteristic replicase (Rep) and capsid (Cap) proteins of circoviruses [40,41,42]. Detection coincided with unexplained summer mortalities in brood-fish, although a direct causal role was not firmly established [40]. Current evidence suggests that circoviruses in fish tend to cause subclinical, persistent infections, with clinical signs appearing mainly under stress or in the presence of coinfections [40]. In S. glanis, CfCV has not yet been linked to specific pathology, but its occurrence highlights the hid-den diversity of the catfish virome and the possibility that apparently healthy populations may still harbor latent viral agents.

3.1.5. Rhabdoviruses

Rhabdoviruses have also been sporadically reported in European catfish. Some studies describe rhabdovirus-like particles resembling vesiculoviruses or novirhabdoviruses in diseased S. glanis showing hemorrhagic symptoms [42,43,44]. However, no catfish-specific rhabdovirus has yet been isolated or fully characterized. It is possible that catfish act as incidental hosts for certain aquatic rhabdoviruses, such as spring viremia of carp virus or pike fry rhabdovirus, particularly in polyculture systems. Further investigation is needed to clarify their role and potential impact on S. glanis.

Overall, beyond ranaviruses and alloherpesviruses, knowledge of viruses in S. glanis remains limited. The evidence so far indicates that other viruses—such as papillomaviruses, circoviruses, and rhabdoviruses—usually cause subacute or chronic effects rather than sudden, large-scale mortality. Nevertheless, their presence contributes to the overall pathogen burden and may interact with environmental stressors or other infections to compromise catfish health. Continuous surveillance is therefore important to track these agents and to understand their potential role in shaping disease dynamics in both farmed and wild populations. A summary of the key viral pathogens identified in S. glanis is presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Key viral pathogens of S. glanis.

3.2. Bacterial Pathogens

Bacterial infections in European catfish most often emerge under conditions of intensive rearing or environmental stress and are typically expressed as ulcerative or septicemic syndromes. Many of the bacteria that affect S. glanis are opportunistic species commonly found in freshwater habitats, but the species is also vulnerable to several well-known fish pathogens. Unlike the North American channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus), which suffers from the host-specific Edwardsiella ictaluri, the European catfish has no endemic bacterium of comparable impact [45]. Instead, outbreaks in S. glanis usually involve generalist pathogens that exploit suboptimal rearing conditions.

3.2.1. Aeromonas Genus

Among bacterial threats to S. glanis, motile Aeromonas species are considered the most common. Aeromonas hydrophila and related taxa, such as A. veronii, are responsible for motile Aeromonas septicemia (MAS), which is characterized by hemorrhagic skin lesions, abdominal swelling, and septicemia. A severe outbreak of MAS was reported in 2016 at a catfish farm in Tianjin, China, where A. veronii biovar sobria was identified as the causative agent [46]. Diseased fish showed petechial hemorrhages, ascites, and inflamed vent regions, and experimental infections reproduced high mortality with an LD50 of ~1.6 × 106 CFU/mL in zebrafish [46]. Although Aeromonas spp. are opportunistic and tend to proliferate under poor water quality or high organic loads, virulent strains can cause acute epidemics in catfish, especially at higher temperatures. These bacteria also pose a zoonotic risk, as Aeromonas can infect humans, causing gastroenteritis, wound infections, or septicemia [16,47]. Furthermore, the emergence of antibiotic-resistant strains in aquaculture highlights the need for careful antimicrobial use and the exploration of alternatives such as vaccines or probiotics [48].

3.2.2. Edwardsiella Genus

Species of the genus Edwardsiella have occasionally been isolated from S. glanis. Edwardsiella tarda, known to cause emphysematous putrefactive disease in fish, has been recovered from European catfish showing septicemia with hemorrhagic signs [45]. Although infections by E. tarda in S. glanis are relatively uncommon, the bacterium is widely distributed and infects many freshwater fish species [49,50]. By contrast, Edwardsiella ictaluri, the causative agent of enteric septicemia of catfish (ESC) in North American ictalurids, has not yet emerged as a significant pathogen in European catfish aquaculture [51,52]. This absence may reflect both geographic and phylogenetic differences. Nonetheless, the possibility of ESC introduction into S. glanis populations through trade or co-culture cannot be excluded. Given the devastating impact of E. ictaluri on channel catfish farming, continuous monitoring remains essential.

3.2.3. Flavobacterium Genus

Opportunistic bacteria of the genus Flavobacterium are also frequently associated with disease in European catfish. Flavobacterium columnare, the causative agent of columnaris disease, produces characteristic yellowish-brown lesions on the skin and gills [53]. In S. glanis, F. columnaris outbreaks are most common under warm and crowded conditions, where gill tissues often show necrotic patches and a typical “saddleback” lesion may appear along the dorsum [54].

Many bacterial infections in catfish are linked to stress factors such as handling, crowding, or temperature fluctuations, which compromise immune defenses and trigger disease [55]. Mixed bacterial infections are not unusual, making it difficult to identify the primary pathogen. Standard preventive measures—good husbandry practices, adequate nutrition, and minimizing stress—are essential to reduce the risk. Vaccination against bacteria such as Aeromonas or Flavobacterium is under investigation, but no commercial vaccines are yet widely used in S. glanis aquaculture. Table 6 summarizes key bacterial pathogens of S. glanis.

Table 6.

Key bacterial pathogens of S. glanis.

3.3. Parasitic Pathogens

Parasites constitute a significant component of the disease burden in European cat-fish. Owing to its predatory habits and benthic lifestyle, S. glanis can acquire a wide array of parasites through the food chain and environment. Parasite infestations in catfish are particularly relevant in extensive or natural settings, but they can also pose problems in aquaculture (especially for juvenile fish).

3.3.1. Protozoan Parasites

Ichthyophthirius Genus

Ichthyophthirius multifiliis, the causative agent of white spot disease or ichthyophthyriasis, is arguably the most problematic protozoan parasite for S. glanis. Ichthyophthirius is an obligate ectoparasitic ciliate that infects skin and gills of freshwater fish [56]. European catfish are highly susceptible to Ichthyophthirius, particularly in fingerling stages. The parasite forms characteristic white cysts (0.5–1 mm) embedded in the epithelium. The intense irritation caused by Ichthyophthirius often prompts fish to flash or scrape against surfaces. If one observes such behavior in catfish along with white spots on the skin, an ichthyophthyriasis outbreak is likely underway and requires prompt intervention to save the stock. Heavy infestations lead to irritation, excess mucus production, breathing difficulty, and often death if untreated. Historically, outbreaks caused significant fingerling mortalities in wels catfish pond culture [57]. Treatments with novel compounds could be effective, but the ban of some chemicals in aquaculture fish food has made disease control more challenging. Today, prevention via quarantine and environmental management (e.g., avoiding sudden temperature drops that favor parasite reproduction) is key, and some newer therapeutics (like formalin, hydrogen peroxide, or herbal extracts, etc.) are used with varying success [10,58,59,60].

Trichodina Genus

Another common protozoan parasite is Trichodina spp., a genus of disk-shaped peritrichous ciliates. Trichodina are found on the skin and gills of catfish as ectocommensals or mild parasites [61]. In low numbers, it usually does not cause clinical disease, but heavy infestations can irritate the gills, causing respiratory stress and poor growth. Trichodinosis often indicates deteriorating water quality or high organic load, as these ciliates proliferate in such conditions [62]. Under the microscope, Trichodina can be identified by its distinctive circular denticulate ring. In S. glanis hatcheries, routine checks for Trichodina on gill/skin scrapes are recommended, and if they are present, a corrective action, such as improving water quality or applying a mild disinfectant, can prevent more serious issues.

Flagellated Protozoa

Various flagellated protozoa may inhabit the gastrointestinal tract of catfish, though reports are less common. Genera such as Hexamita and Spironucleus (collectively hexamitids) are known to cause intestinal parasitosis in other fishes (e.g., cichlids) and have occasionally been noted in catfish intestines [63]. Ichthyobodo necator (syn. Costia necatrix) is observed on the epithelium of a catfish gill [64]. Clinical hexamitosis in S. glanis would manifest as emaciation and malabsorption, but detailed studies in this host are lacking.

Blood Parasites

Blood parasites have also been documented in S. glanis. Trypanosomes (genus Trypanosoma) are flagellate protozoa transmitted by leeches that infect the blood of many freshwater fish, including S. glanis [65]. These blood parasites rarely cause overt disease in healthy adult catfish, but in young or stressed fish, they might contribute to anemia or lethargy. Similarly, S. glanis may host Trypanoplasma (also known as Cryptobia), another group of blood flagellates [66]. The ecological relevance of these protozoans is notable: they illustrate the catfish’s role as a reservoir for parasites that involve intermediate hosts (leeches) and potentially other vertebrates.

Myxobolus Genus

Another protozoan gill parasite found in S. glanis is the spore-forming Myxobolus pfeifferi [61]. It parasitizes a wide range of fish hosts, causing them the disease known as myxoboliosis. Fish have difficulty in swimming and a slow growth rate. Myxobolus passes through two stages of development in its biological cycle: vegetative and spore. The spore stage represents both a form of resistance and reproduction [67].

S. glanis does not have many host-specific protozoan pathogens, but it could be used as a reservoir host that transmits parasites, which can cause serious losses if not properly managed. Table 7 summarizes key protozoan parasites of S. glanis.

Table 7.

Key protozoan parasites of S. glanis.

3.3.2. Helminths and Other Metazoan Parasites

European catfish harbor a rich assemblage of helminth parasites—worms that infect various organs [68]. Many of them have complex life cycles involving intermediate hosts, reflecting S. glanis’ position as an apex predator that accumulates parasites from the food change, and some can infect humans via raw or undercooked fish.

Monogenean Parasites

Monogenean parasites are among the most important ectoparasites of the European catfish, colonizing the gills, skin, and fins and often causing significant pathological changes. Two species of particular importance are Thaparocleidus siluri and Thaparocleidus vistulensis (formerly genus Dactylogyrus or Ancylodiscoides). These monogeneans are flatworms with a direct life cycle (no intermediate hosts) and attach to gill tissue via hooks, feeding on mucus and blood. Together, these monogeneans represent a significant health concern for European catfish [69]. Thaparocleidus siluri is a gill monogenean specific to European catfish. Surveys of aquaculture systems report it frequently co-occurring with other monogeneans, where it contributes to hyperplasia, mucus hypersecretion, and respiratory impairment, particularly in warm-water or intensive culture environments [70]. Thaparocleidus vistulensis is another major gill parasite of S. glanis. Light infestations may go unnoticed, but the heavy loads cause gill monogenosis, leading to hyperplasia of gill epithelium, anemia, and respiratory distress. Infected gills show pale patches and increased mucus, and fish may exhibit rapid gill movements or gasp at the surface due to hypoxia. Histopathological studies have documented deep anchor penetration into lamellae, causing fusion, clubbing, and intralamellar hemorrhages [57,71]. Experimental work has shown its high fecundity and resilience under varying temperature and light conditions, supporting its capacity to thrive in aquaculture. Monogeneans proliferate in varying light–dark conditions and water at 10–30 °C, and the parasite’s fecundity is optimal at 15 °C, eggs hatched fastest at 30 °C, whereas no hatching occurred at 5 °C and 35 °C [72]. Standardized cohabitation-based sampling methods have been developed to study their life cycle and spatial distribution on gills, typically preferring mid-distal sectors [71]. An outbreak of T. vistulensis in a catfish farm can stunt growth and predispose fish to bacterial gill infections. Control is usually achieved by periodic antiparasitic treatments (e.g., formalin, praziquantel, etc.) and by avoiding the introduction of wild fish that carry these worms. Recent studies have examined the pathology of Thaparocleidus on catfish gills and noted that even moderate infections can provoke inflammation and secondary bacterial invasion [73,74]. Thus, managing monogeneans is an important aspect of catfish health. The Thaparocleidus genus represents a challenge for the aquaculture of European catfish. Although species are not zoonotic, their impact on fish welfare, growth, and susceptibility to other pathogens makes them economically significant. Ongoing studies suggest that routine monitoring, molecular identification, and improved management practices are essential for controlling monogenean infections in catfish farms [73].

Digenean Trematode Parasites

Digenean trematode parasites of European catfish include Diplostomum and Orientocreadium species, which affect different organs and impact fish health [68]. Diplostomum spathaceum is a trematode widely distributed in freshwater ecosystems. Its metacercariae migrate to the eye lens, causing “eye fluke” disease or diplostomosis, causing cataracts, impaired vision, and behavioral changes. S. glanis can accumulate Diplostomum cysts in its lens or vitreous humor if it inhabits waters with the snail and bird hosts that complete the fluke’s life cycle [75]. While vision is not the primary hunting sense for catfish (which rely more on smell and mechanosensation), severe eye damage can still stress the fish and make them more prone to predation or reduced foraging efficiency. Orientocreadium siluri is another specific species found primarily in the gastrointestinal tract, especially in the mid- and foregut of European catfish in Asia and Eastern Europe [11,68,76].

Cestodean Parasites

Cestodes (tapeworms) are frequently recorded in European catfish. Catfish are definitive hosts for certain tapeworms. One example is Silurotaenia siluri, a specific tapeworm of wels catfish [77,78]. Adult S. siluri live in the catfish intestine, sometimes reaching considerable lengths [68]. They absorb nutrients through their tegument, potentially causing nutritional robbing and mechanical irritation. Proteocephalus osculatus is another cestode often found in S. glanis intestines [78]. Triaenophorus meridionalis and Caryophyllaeus laticeps are other cestodes found in S. glanis intestine [68]. Heavy tapeworm burdens can lead to emaciation or intestinal blockage in severe cases, although mild infections may be asymptomatic. These tapeworms have complex life cycles involving intermediate hosts like copepods (first host) and fish (second host). Thus, their presence in catfish indicates a long ecological chain and a healthy population of intermediate hosts in the ecosystem. Control in aquaculture is rarely needed unless catfish are fed raw fish containing larval cestodes; in such cases, freezing the feed fish can break the cycle.

Nematodean Parasites

Nematodes (roundworms) form a large portion of the catfish parasite fauna. A comprehensive review discusses 21 species of nematodes infecting S. glanis [79]. Common examples include Raphidascaris acus (a gastrointestinal nematode) and larvae of Eustrongylides spp. (a tissue nematode). R. acus adults reside in the catfish intestine, where they attach to the mucosa. They can cause inflammation, granulomas, and occasional perforation of the gut wall when present in high numbers. This nematode is acquired when catfish eat infected intermediate hosts (small fish carrying larvae), and it has been reported widely in Europe and Asia in wels catfish [11,57,79,80]. Perhaps more dramatic are the larvae of Eustrongylides species, specifically Eustrongylides excisus, a large red nematode with a life cycle involving aquatic birds. Catfish can serve as paratenic or second intermediate hosts for their larvae, which typically embed in the body cavity or musculature. These larvae can grow several centimeters long and cause granulomatous inflammation in the tissues where they encyst. In infected S. glanis, one might notice coiled red worms in the visceral cavity during necropsy [11,68,79,81]. While often not causing acute death, E. excisus can weaken the fish and render it unmarketable. Importantly, E. excisus is a zoonotic parasite—humans who consume raw or undercooked fish containing these larvae can develop a serious illness (gastrointestinal or tissue-invasive eustrongylidosis). Although human cases are rare, the presence of E. excisus in food fish like catfish necessitates proper evisceration and cooking. Catfish farmers mitigate this risk by avoiding bird predation in ponds (since fish-eating birds are the definitive hosts shedding E. excisus eggs). Other nematodes recorded in S. glanis include Camallanus lacustris (a common intestinal worm with copepod intermediate host) and Contracaecum larvae (often encysted in viscera, from pelican or cormorant lifecycles). Each of these reflects the complex food web connections of catfish [79,82].

Acanthocephalan Parasites

Acanthocephalan parasites of European catfish include Acanthocephalus lucii and Pomphorhynchus laevis. A. lucii is a widely distributed acanthocephalan species infecting various freshwater fish across Europe, including the wels catfish [83]. Adult worms attach to the fish intestine using a hooked proboscis, embedding into the mucosa and absorbing nutrients through their tegument—often causing mechanical damage, hemorrhages, and reduced growth in heavy infestations [84]. Recent studies highlight the ecological significance of A. lucii as biosentinels for heavy metal pollution. These worms bioaccumulate trace metals (e.g., Cd, Pb, Tl) at concentrations many-fold higher than those in host tissues, making them useful indicators of contamination and possibly even mitigating metal toxicity to their fish hosts by sequestering metals in the intestinal lumen [85,86,87]. P. laevis is another acanthocephalan species infecting various freshwater fish, including the wels catfish [68]. This parasite attaches to the intestinal wall of its host using a retractable proboscis armed with hooks, causing mechanical damage and potentially leading to inflammation and reduced growth in the host [88]. The presence of P. laevis in freshwater fish populations can have ecological implications, particularly in terms of host health and the dynamics of parasite communities [89]. Understanding the distribution and impact of these parasites is crucial for managing fish health and biodiversity in freshwater ecosystems.

Crustacean Parasites

Apart from worms, S. glanis can suffer from crustacean parasites. Two noteworthy examples are the anchor worm Lernaea cyprinacea and the fish louse Argulus foliaceus. Lernaea is a copepod that burrows into the skin, typically on the fins or caudal area, with an erupting worm-like trunk and anchoring hooks. In catfish, heavy Lernaea infestations cause focal ulcers and blood loss. Argulus are disk-like branchiuran crustaceans that clamp onto the skin or gills and feed on blood. They can cause irritation, anemia, and transmit other pathogens. Both Lernaea and Argulus thrive in warm stagnant waters; they have been reported on wild and pond-held S. glanis [11,61]. Treatment involves manual removal or chemical bath treatments (e.g., organophosphates), and prevention is aided by keeping ponds free of invasive small fish, which can carry juvenile stages of these parasites.

The helminth and metazoan parasites of S. glanis are diverse. Table 8 summarizes the key species. From an ecological standpoint, the presence of these parasites indicates S. glanis’ integration into aquatic food nets (serving as definitive or intermediate host). Some parasites (like Diplostomum or Eustrongylides) highlight connections between catfish and avian predators, while others (like Camallanus or Lernaea) tie catfish to invertebrate communities. In aquaculture, parasite management focuses on breaking life cycles (e.g., lining ponds to prevent snail or copepod populations, or fallowing to disrupt parasite transmission). With the trend toward recirculating systems, many of these parasites become less common, but any facility drawing surface water or stocking wild-caught juveniles must remain vigilant for parasite introduction.

Table 8.

Key helminths and other metazoan parasites of S. glanis.

3.3.3. Oomycetes Infections

Oomycete diseases in European catfish are generally opportunistic, arising secondary to other stressors or lesions. Oomycetes can infect catfish, especially when water quality deteriorates or fish are immunocompromised.

Saprolegnia Genus

Saprolegniosis is caused by water molds of the genus Saprolegnia (oomycetes) and typically manifests as whitish, cotton-like patches on the skin or gills of fish. S. parasitica, S. ferax, and S. australis are reported in European catfish [90]. In S. glanis, Saprolegnia spp. often colonizes areas of prior damage—for instance, a net handling injury or a parasite lesion, and can expand into larger patches that compromise the epidermis. While Saprolegnia primarily consumes dead tissue, its growth on live fish can lead to osmotic stress, secondary bacterial invasion, and potentially mortality if extensive. Catfish eggs are also very susceptible to saprolegniasis, which can wipe out incubating eggs in the absence of antifungal treatments. The key to controlling saprolegniosis is prevention: maintaining good water quality and minimizing skin injuries. Once lesions appear, topical treatments (e.g., potassium permanganate or hydrogen peroxide baths) are used. Overall, Saprolegnia is a ubiquitous water mold, and in catfish, its presence is an indicator of underlying stress or trauma that should be addressed.

Branchiomycosis Genus

Branchiomycosis, also known as gill rot, is a more severe and specific condition caused by Branchiomyces spp., which are filamentous oomycetes that invade gill blood vessels. B. sanguinis and B. demigrans are responsible for outbreaks of gill rot in warm-water fish [11]. The European catfish is among the species susceptible to branchiomycosis, particularly in eutrophic ponds during the summer [91]. In S. glanis, branchiomycosis can cause sudden high mortality [92]. The oomyces infects gill tissues, leading to thrombosis of branchial blood vessels and necrosis of gill filaments. Grossly, gills develop irregular patchy discoloration, with maroon to white necrotic areas interspersed with healthy tissue, giving a marbled appearance. Affected catfish may show signs of respiratory distress (gasping, reduced activity), and death can occur quickly due to loss of gill function. Outbreaks are often precipitated by high water temperatures (over 25 °C), organic-rich water, and crowding, which favor the proliferation of Branchiomyces spores in the environment [18]. Because branchiomycosis is acute and difficult to treat (few fungicides can be used in fish food at needed concentrations), emphasis is on prevention: avoiding excessive organic loading, reducing crowding in summer, and removing dead fish promptly (to reduce spore reservoirs). If an outbreak occurs, improving water flow and lowering temperature (if possible) can mitigate losses, and sometimes copper sulfate treatments are applied as a control measure with variable success. Branchiomyces outbreaks in catfish ponds have been recorded in Central and Eastern Europe, occasionally causing severe epizootics with 50–70% mortality in stocked fish (based on field reports) [92].

Oomycetes tend to be secondary invaders in S. glanis; all infections occur after some primary insult (such as parasitic or mechanical skin damage) [18]. Therefore, maintaining overall fish health and promptly treating primary diseases goes a long way in preventing oomycete issues. It is also important to note that some fungal-like infections of catfish might be underdiagnosed; for example, Ichthyophonus (a mesomycetozoea) could potentially infect catfish that consume infected prey, although it is more commonly reported in other predatory fish [93]. No significant Ichthyophonus outbreaks have been reported in S. glanis to date [92]. Lastly, while not a pathogen of catfish per se, molds can produce toxins in feed (mycotoxins) that indirectly affect catfish health; careful feed storage is thus part of good health management. Table 9 summarizes the knowledge about saprolegniosis and branchiomycosis.

Table 9.

Key oomycete pathogens of S. glanis.

4. Discussion

The taxonomic diversity and geographic spread of pathogens affecting S. glanis are shaped by multiple interacting factors. The wide taxonomic range and uneven geographical distribution of pathogens identified in Silurus glanis demonstrate the complexity of host–pathogen–environment interactions in freshwater ecosystems. Integrating these elements into a digitally designed conceptual model enables a comprehensive understanding of disease emergence and supports predictive capabilities relevant to both aquaculture and conservation.

Environmental determinants remain primary drivers of pathogen presence and diversity. Temperature influences nearly all pathogen groups, affecting viral replication, bacterial virulence, and the life cycles of protozoans and helminths. In warmer regions or seasons, infections by Aeromonas spp., Flavobacterium columnare, monogeneans, and oomycetes become more frequent, while thermal instability stimulates the proliferation of ciliates such as Ichthyophthirius multifiliis. Water chemistry, including dissolved oxygen, ammonia levels, and organic load, further modifies host susceptibility and pathogen persistence. These variables often act synergistically: eutrophication not only enhances microbial growth but also favors intermediate hosts that support complex parasite life cycles. Consequently, regional environmental gradients directly shape pathogen community structure.

Host-specific factors contribute an additional layer to this complexity. Age-dependent susceptibility is evident, with juveniles experiencing more severe viral and bacterial infections, while adults accumulate long-lived helminths. Physiological stress, driven by high fish density or poor water quality, suppresses immune function and facilitates co-infections, which frequently alter the clinical course of disease. Behavioral traits, such as the benthic feeding habits of S. glanis, increase exposure to intermediate hosts of acanthocephalans, nematodes, and trematodes. These host properties must therefore be integrated into any predictive model, aiming to capture realistic infection dynamics.

Wild ecosystems also exert significant influence. Parasites relying on multiple hosts, such as Diplostomum (snails and birds), Eustrongylides (oligochaetes and birds), and Pomphorhynchus (amphipods and fish), respond strongly to changes in biodiversity, water flow, and trophic interactions. Geographical differences in bird migration, mollusk distribution, or fish community composition translate into distinct regional disease profiles. As a result, pathogen patterns in S. glanis often reflect broader ecosystem health indicators, making them valuable for ecological monitoring.

Anthropogenic drivers amplify these natural processes. The intensification of aquaculture creates conditions conducive to pathogen transmission and accelerates the spread of infectious agents beyond their native ranges. Fish transport for stocking or trade frequently introduces new pathogens into previously unaffected regions. Insufficient biosecurity, combined with antibiotic misuse, may further promote the establishment of resistant bacterial strains. These human-mediated pathways must be integrated into any digital model that seeks to assess or anticipate pathogen dispersal.

The digital conceptual model, proposed here, synthesizes four fundamental layers: environmental variables, host-related attributes, pathogen traits, and anthropogenic factors. By linking these components, such a model not only visualizes current pathogen distribution but also allows simulations under projected climate conditions, altered aquaculture practices, or changes in wildlife ecology. Predictive outputs may identify high-risk periods or regions, thus supporting targeted surveillance, optimized farm management, and strategic interventions aimed at minimizing disease impact.

Despite considerable progress, several disruptions remain. Molecular characterization of emerging viruses is still limited, and long-term ecological studies on helminth and protozoan communities are insufficient. The role of climate-induced habitat shifts in pathogen emergence warrants further investigation, particularly regarding temperature-sensitive species. Strengthening future research through harmonized diagnostic approaches, expanded geographical sampling, and robust ecological modeling will substantially improve the capacity to manage pathogen risks in S. glanis populations, as well as in the water ecosystems at all.

The integration of ecological, environmental, and anthropogenic factors into a digitally structured framework provides new opportunities for understanding pathogen dynamics. Environmental changes, especially temperature rise, eutrophication, and altered hydrological regimes, promote proliferation of opportunistic pathogens such as Aeromonas, Saprolegnia, monogeneans, etc. A conceptual digital model integrating climatic data, water chemistry, host movement, and pathogen biology can help predict pathogen emergence. Such an approach aligns with One Health principles and offers a solid basis for developing sustainable management strategies that support both aquaculture production and wild ecosystem integrity. A model could incorporate environmental clusters (temperature, dissolved oxygen, nutrient load, etc.); host factors (age, density, stress indicators, etc.); pathogen features (life cycle complexity, intermediate hosts, transmission mode, etc.); anthropogenic impacts (translocations, trade, antibiotic use, etc.). The proposed approach corresponds with the One Health framework and marks connections in fish health in wild and aquaculture aquatic ecosystems, and potential risks to humans.

5. Conclusions

S. glanis, the European catfish, hosts a wide array of pathogens reflecting its role as a top predator and a cultured species. This review has highlighted that major pathogen groups—viruses, bacteria, parasites, and oomycetes—all include members capable of infecting wels catfish (Table 5, Table 6, Table 7, Table 8 and Table 9). The biodiversity of S. glanis pathogens is noteworthy: from large DNA viruses like ranaviruses and herpesviruses, to microscopic ciliates and metazoan worms, the catfish can be considered an entire ecosystem of parasites. Ecologically, these pathogens illustrate the interconnectedness of the aquatic environment. For instance, the life cycles of catfish helminths involve organisms ranging from mollusks to birds, indicating that changes in ecosystem composition (such as the introduction of new species or loss of predators) can influence catfish disease patterns.

From an aquaculture perspective, understanding these host–pathogen relationships is critical for sustainable catfish production. Viral diseases can cause sudden high losses, so biosecurity and possibly selective breeding for resistance are priorities. Bacterial opportunists demand good water quality and stress reduction, along with prudent use of antibiotics to prevent resistance. Parasite management in catfish farming may involve integrated approaches such as periodic antiparasitic treatments, environmental modifications (e.g., snail control to break trematode life cycles), and incorporation of cleaner species or low-density polyculture to reduce parasite burdens (taking a cue from traditional practices where catfish themselves helped control carp diseases). Oomycete issues, being secondary, underscore the importance of overall health management.

Importantly, more than 65% of the papers cited in this review are from the last five years (2021–2025), and 30% of all references are published in 2025, reflecting a growing research focus on catfish pathogens. This includes molecular characterization of newly discovered viruses and parasites, as well as investigations into zoonotic aspects of fish pathogens. The One Health concept is highly relevant to S. glanis diseases: pathogens such as Aeromonas and Edwardsiella, and certain parasites, such as Eustrongylides and Contracaecum, can affect multiple species, including humans. Thus, disease control in catfish aquaculture has benefits beyond just the farm—it helps protect wild fish communities and public health by limiting the spread of infectious agents and antimicrobial resistance genes.

The European catfish faces a broad but manageable spectrum of diseases. Continued research and surveillance are needed to detect emerging pathogens (e.g., novel viruses or drug-resistant bacteria) early. Effective control will rely on a combination of traditional methods (husbandry, hygiene, sound nutrition, etc.) and modern tools (vaccines, probiotics, genetic selection for disease resistance, etc.). Given the ecological versatility of S. glanis, a balanced approach that considers environmental health, fish health, and socio-economic factors will be most successful. Protecting European catfish from its pathogens is not only vital for aquaculture productivity but also for conserving this iconic species’ role in aquatic ecosystems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.M. and G.A.; methodology, K.M. and G.A.; software, K.M. and G.A.; validation, K.M. and G.A.; formal analysis, K.M. and G.A.; investigation, K.M. and G.A.; resources, K.M. and G.A.; data curation, K.M. and G.A.; writing—original draft preparation, K.M. and G.A.; writing—review and editing, K.M. and G.A.; visualization, K.M. and G.A.; supervision, G.A.; project administration, K.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| S. glanis | Silurus glanis |

| ESV | European sheatfish virus |

| ECV | European catfish virus |

| EHNV | Epizootic hematopoietic necrosis virus |

| SgPV1 | Silurus glanis papillomavirus 1 |

| CfCV | Silurus glanis circovirus |

| A. veronii | Aeromonas veronii |

| F. columnare | Flavobacterium columnare |

| S. siluri | Silurotaenia siluri |

| E. excisus | Eustrongylides excisus |

| P. laevis | Pomphorhynchus laevis |

| S. parasitica | Saprolegnia parasitica |

| S. ferax | Saprolegnia ferax |

| S. australis | Saprolegnia australis |

| B. sanguinis | Branchiomyces sanguinis |

| B. demigrans | Branchiomyces demigrans |

| MAS | motile Aeromonas septicemia |

| ESC | enteric septicemia of catfish |

References

- Lindell, N. Habitat Preference and Activity Pattern of European Catfish (Silurus glanis) at Its Northernmost Distribution Area. Ph.D. Thesis, Linköping University, Linköping, Sweden, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Říha, M.; Rabaneda-Bueno, R.; Jarić, I.; Souza, A.T.; Vejřík, L.; Draštík, V.; Blabolil, P.; Holubová, M.; Jůza, T.; Gjelland, O.K.; et al. Seasonal habitat use of three predatory fishes in a freshwater ecosystem. Hydrobiologia 2022, 849, 3351–3371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Encina, L.; Rodríguez-Ruiz, A.; Orduna, C.; Cid, J.R.; Granado-Lorencio, C. Impact of invasive catfish (Silurus glanis) on the fish community of Torrejón reservoir (Central Spain) during a 11-year monitoring study. Biol. Invasions 2024, 26, 745–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajdlová, Z.; Jůza, T.; Blabolil, P.; Draštík, V.; Čech, M. Pelagic distribution and night foraging of early juvenile European catfish (Silurus glanis L.). J. Fish Biol. 2025, 106, 1893–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adakebaike, Z.; Wang, Z.; Anasi, H.; He, J.; Zhai, X.; Shi, C.; Nie, Z. Study on the morphological development timeline and growth model of embryos and larvae of European catfish (Silurus glanis). Animals 2025, 15, 2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegedűs, B.; Bagi, Z.; Kusza, S. Navigating the genetic landscape: Investigating the opportunities and risks of cross-species SNP array application in catfish. Genes 2025, 16, 717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koprucu, K.; Yonar, S.M.; Koprucu, S.; Yonar, M.E. Effect of different stocking densities on growth, oxidative stress, antioxidant enzymes, and hematological and immunological values of European catfish (Silurus glanis L.; 1758). Aquac. Int. 2024, 32, 2957–2973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gisbert, E.; Luz, R.K.; Fernandez, I.; Pradhan, P.K.; Salhi, M.; Mozanzadeh, M.T.; Kumar, A.; Kotzamanis, Y.; Castro-Ruiz, D.; Bessonart, M.; et al. Development, nutrition, and rearing practices of relevant catfish species (Siluriformes) at early stages. Rev. Aquac. 2022, 14, 73–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, M.; Sellyei, B.; Kovács, G.; Székely, C. Viruses infecting the European catfish (Silurus glanis). Viruses 2021, 13, 1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, M.; Abdel-Baki, A.-A.; Dkhil, M.A.; El-Matbouli, M.; Al-Quraishy, S. Antiprotozoal effects of metal nanoparticles against Ichthyophthirius multifiliis. Parasitology 2017, 144, 1802–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roohi, D.J.; Sattari, M.; Asgharnia, M.; Rufchaei, R. Occurrence and intensity of parasites in European catfish, Silurus glanis L., 1758 from the Anzali Wetland, southwest of the Caspian Sea, Iran. Croat. J. Fish. 2014, 72, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauad, J.R.C.; da Silva, M.C.; Araújo, C.M.C.; Silva, R.M.M.F.; Caleman, S.M.D.Q.; Russo, M.R. Zoonotic agents in farmed fish: A systematic review from the interdisciplinary perspective of the One Health concept. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baer, J.; Hüsgen, S.; Fromherz, M.; Geist, J.; Brinker, A. Drivers of the range expansion of the European catfish (Silurus glanis) within its native distribution. J. Fish Biol. 2025, 107, 1030–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rees, A. The Impact of Introduced European Catfish (Silurus glanis L.) in UK Waters: A Three Pond Study. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Hertfordshire, Hatfield, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ziarati, M.; Zorriehzahra, M.J.; Hassantabar, F.; Mehrabi, Z.; Dhawan, M.; Sharun, K.; Shamsi, S. Zoonotic diseases of fish and their prevention and control. Vet. Q. 2022, 42, 95–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, D.; Baron, S.; Travers, A.; Longshaw, M.; Haenen, O. One Health in fish and shellfish. Bull. Eur. Assoc. Fish Pathol. 2025, 45, 124752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boon, J.H.; Huisman, E.A. Viral, bacterial and fungal diseases of Siluroidei, cultured for human consumption. Aquat. Living Resour. 1996, 9, S153–S164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, V.A.; Holmes, E.C. Diversity, evolution, and emergence of fish viruses. J. Virol. 2024, 98, e00118-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarján, Z.L.; Doszpoly, A.; Eszterbauer, E.; Benko, M. Partial genetic characterisation of a novel alloherpesvirus detected by PCR in a farmed Wels catfish (Silurus glanis). Acta Vet. Hung. 2022, 70, 321–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abonyi, F.; Varga, A.; Sellyei, B.; Eszterbauer, E.; Doszpoly, A. Juvenile Wels catfish (Silurus glanis) display age-related mortality to European catfish virus (ECV) under experimental conditions. Viruses 2022, 14, 1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surján, A.; Fónagy, E.; Eszterbauer, E.; Harrach, B.; Doszpoly, A. Complete genome sequence of a novel fish papillomavirus detected in farmed Wels catfish (Silurus glanis). Arch. Virol. 2021, 166, 2603–2606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doszpoly, A. Establishment and partial characterization of three novel permanent cell lines originating from European freshwater fish species. Pathogens 2025, 14, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Békési, L.; Kovacs-Gayer, E.; Ratz, F.; Turkovics, O. Skin infection of the sheatfish (Silurus glanis L.) caused by a herpes virus. In Fish, Pathogens, and Environment in European Polyculture; Akadémiai Kiadó: Budapest, Hungary, 1984; pp. 25–30. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, H.; Zhou, T.; Wang, X.; Yang, Y.; Wu, C.; Liu, S.; Bao, L.; Li, N.; Yuan, Z.; Jin, Y.; et al. Genome-wide association analysis of intra-specific QTL associated with the resistance for enteric septicemia of catfish. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2018, 293, 1365–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abass, N.Y.; Ye, Z.; Alsaqufi, A.; Dunham, R.A. Comparison of growth performance among channel–blue hybrid catfish, ccGH transgenic channel catfish, and channel catfish in a tank culture system. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahne, W.; Schlotfeldt, H.J.; Thomsen, I. Fish viruses: Isolation of an icosahedral cytoplasmic deoxyribovirus from sheatfish (Silurus glanis). J. Vet. Med. Ser. B 1989, 36, 333–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martín, V.; Mavian, C.; Lopez Bueno, A.; de Molina, A.; Díaz, E.; Andrés, G.; Alejo, A. Establishment of a zebrafish infection model for the study of wild-type and recombinant European sheatfish virus. J. Virol. 2015, 89, 10702–10706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leimbach, S.; Schütze, H.; Bergmann, S.M. Susceptibility of European sheatfish Silurus glanis to a panel of ranaviruses. J. Appl. Ichthyol. 2014, 30, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siwicki, A.K.; Pozet, F.; Morand, M.; Volatier, C.; Terech-Majewska, E. Effects of iridovirus-like agent on the cell-mediated immunity in sheatfish (Silurus glanis)–An in vitro study. Virus Res. 1999, 63, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancheva, K.; Danova, S.; Vilhelmova-Ilieva, N.; Dobreva, L.; Kostova, K.; Simeonova, L.; Atanasov, G. Viral pathogens with economic impact in aquaculture. Acta Microbiol. Bulg. 2021, 37, 111–121. [Google Scholar]

- Pozet, F.; Morand, M.; Moussa, A.; Torhy, C.; De Kinkelin, P. Isolation and preliminary characterization of a pathogenic icosahedral deoxyribovirus from the catfish Ictalurus melas. Dis. Aquat. Org. 1992, 14, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovo, G.; Comuzi, M.; Cescia, G.; Giorgetti, G.; Giacometti, P.; Cappellozza, E. Isolamento di un agente virale irido-like da pescegatto (Ictalurus melas) dall’allevamento. Boll. Soc. Ital. Patol. Ittica 1993, 11, 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Bigarré, L.; Cabon, J.; Baud, M.; Pozet, F.; Castric, J. Ranaviruses associated with high mortalities in catfish in France. Bull. Eur. Assoc. Fish Pathol. 2008, 28, 163–168. [Google Scholar]

- Eaton, H.; Metcalf, J.; Penny, E.; Tcherepanov, V.; Upton, C.; Brunetti, C.R. Comparative genomic analysis of the family Iridoviridae: Re-annotating and defining the core set of iridovirus genes. Virol. J. 2007, 4, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marsh, I.B.; Whittington, R.J.; O’Rourke, B.; Hyatt, A.D.; Chisholm, O. Rapid differentiation of Australian, European and American ranaviruses based on variation in major capsid protein gene sequence. Mol. Cell. Probes 2002, 16, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, H.J.; Hur, J.W.; Cho, J.B.; Park, K.H.; Jung, H.J.; Kang, Y.J. Introduction of bacterial and viral pathogens from imported ornamental finfish in South Korea. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2019, 22, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adriaenssens, E.; Dutilh, B.; Harrach, B.; Junglen, S.; Kropinski, A.; Krupovic, M.; Kuhn, J.; Mushegian, A.; Postler, T.; Rubino, L.; et al. Modify the International Code of Virus Classification and Nomenclature (ICVCN) to prospectively mandate a uniform genus-species type virus species naming format. Int. Comm. Taxon. Viruses. Approv. Propos. 2018, 2018.001G. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Doorslaer, K. Revisiting papillomavirus taxonomy: A proposal for updating the current classification in line with evolutionary evidence. Viruses 2022, 14, 2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lőrincz, M.; Dán, Á.; Láng, M.; Csaba, G.; Tóth, G.Á.; Székely, C.; Cságola, A.; Tuboly, T. Novel circovirus in European catfish (Silurus glanis). Arch. Virol. 2012, 157, 1173–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rusiñol, M.; Martínez-Puchol, S.; Ribeiro, D.; Verdaguer, J.; Torrejón, O.; Itarte, M.; Fernandez-Cassi, X. Livestock Aggregated Samples for Monitoring Viruses Infecting Animals and Potentially Zoonotic Viral Pathogens; SSRN Elsevier Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2025; p. 5432750. [Google Scholar]

- Varsani, A.; Abd-Alla, A.M.; Arnberg, N.; Bateman, K.S.; Benkő, M.; Bézier, A.; Biagini, P.; Bojko, J.; Butkovic, A.; Canuti, M.; et al. Summary of taxonomy changes ratified by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) from the Animal DNA Viruses and Retroviruses Subcommittee. J. Gen. Virol. 2025, 106, 002113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fijan, N.; Matasin, Z.; Jeney, Z.; Oláh, J.; Zwillenberg, L.O. Isolation of Rhabdovirus carpio from sheatfish (Silurus glanis). In Fish, Pathogens, and Environment in European Polyculture; Akadémiai Kiadó: Budapest, Hungary, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Békési, L.; Pálfi, V.; Csontos, L.; Kovács-Gayer, É.; Csaba, G.; Horváth, I. Epizootiology of the red disease of silure (Silurus glanis L.) and study of the isolated rhabdovirus. Magy. Allatorv. Lapja 1987, 42, 418–422. [Google Scholar]

- Caruso, D.; Schlumberger, O.; Dahm, C.; Proteau, J.P. Plasma lysozyme levels in sheatfish Silurus glanis (L.) subjected to stress and experimental infection with Edwardsiella tarda. Aquac. Res. 2002, 33, 999–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiucai, H.; Xiaoxue, L.; Aijun, L.; Jingfeng, S.; Yajiao, S. Characterization and pathology of Aeromonas veronii biovar sobria from diseased sheatfish Silurus glanis in China. Isr. J. Aquac.-Bamidgeh 2019, 71. [Google Scholar]

- Miryala, K.R.; Swain, B. Advances and challenges in Aeromonas hydrophila vaccine development: Immunological insights and future perspectives. Vaccines 2025, 13, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayyab, M.; Islam, W.; Waqas, W.; Zhang, Y. Probiotic–vaccine synergy in fish aquaculture: Exploring microbiome-immune interactions for enhanced vaccine efficacy. Biology 2025, 14, 629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okasha, L.A.; Farag, E.A.; Sayed-ElAhl, R.M.; Sherif, A.H. Presence of virulent Edwardsiella tarda in farmed Nile tilapia and striped catfish. BMC Microbiol. 2025, 25, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janda, J.M.; Duman, M. Expanding the spectrum of diseases and disease associations caused by Edwardsiella tarda and related species. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, V.P.; Bastos, J.K.; Harries, M.D.; Page, P.N.; Techen, N.; Meepagala, K.M. Constituents from Brazilian propolis against Edwardsiella ictaluri and Flavobacterium covae, two bacteria affecting channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus). J. Fish Dis. 2025, 48, e14030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Shen, L.; Guo, M.; Wang, B.; Liu, H.; Xiao, K.; Shi, Z.; Ji, W. Blood-brain barrier permeability and brain immunity in yellow catfish (Pelteobagrus fulvidraco) responding to Edwardsiella ictaluri infection. Aquaculture 2025, 599, 742179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Shi, Z.; Han, Q.; Wang, Q.; Wang, B.; Guo, M.; Ji, W.; Shen, L. Expression profiles of NOD1 and NOD2 and pathological changes in gills during Flavobacterium columnare infection in yellow catfish, Tachysurus fulvidraco. J. Fish Biol. 2025, 106, 1766–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Sheng, L.; Yazdi, Z.; Li, X.; Liu, Z.; Canakapalli, S.; Zhou, Y.; Liao, C.; Emami, S.; Kelly, A.M.; et al. The impact of florfenicol treatment on the microbial populations present in the gill, intestine, and skin of channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus). Anim. Microbiome 2025, 7, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Paul, T.; Sarkar, P.; Kumar, K. Management of Fish Diseases; Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.; Tu, X.; Xiao, J.; Hu, J.; Gu, Z. Investigations on white spot disease reveal high genetic diversity of the fish parasite, Ichthyophthirius multifiliis (Fouquet, 1876) in China. Aquaculture 2023, 562, 738804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmet, Ö.Z.E.R. Wild and cultured fish parasites in Türkiye: An updated list of species, hosts, microhabitat and zoogeographical distribution since 2020. Bull. Univ. Agric. Sci. Vet. Med. Cluj-Napoca Vet. Med. 2025, 82, 12–68. [Google Scholar]

- Marana, M.H.; Al-Jubury, A.; Mathiessen, H.; Buchmann, K. Lipopeptide surfactant killing of Ichthyophthirius multifiliis: Mode of action. Aquac. Rep. 2023, 30, 101562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özil, Ö. Antiparasitic activity of medicinal plants against protozoan fish parasite Ichthyophthirius multifiliis. Isr. J. Aquac.-Bamidgeh 2023, 75, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajiri, W.M.H.W.; Székely, C.; Czeglédi, I.; Buchmann, K.; Sellyei, B. Comparative in vitro effects of novel and conventional parasiticides on Thaparocleidus vistulensis (Siwak, 1932) (Monopisthocotyla) parasitizing European catfish (Silurus glanis). Aquac. Rep. 2025, 43, 102952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul, Y.R. Assessment of the Morphological Investigations of Some Freshwater Fish Parasites in Greater Zab River, North of Iraq. Master’s Thesis, Graduate School of Natural and Applied Sciences, Harran University, Şanlıurfa, Türkiye, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Arapi, E.A.; Cable, J. Survey-based insights into treatments of infectious diseases in freshwater ornamental fish in the UK. Acad. Biol. 2025, 3, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmer, B.D.; Straus, D.L.; Beck, B.H. Spironucleus and Hexamita spp. In Clinical Guide to Fish Medicine; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021; Volume 20, p. 506. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, W. 3.2.1 Ichthyobodiasis. In Fish Health Section—Blue Book; American Fisheries Society: Bethesda, MD, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Mhaisen, F.T. Checklists of blood parasites of fishes of Iraq. Aalb. Acad. J. Pure Sci. 2020, 1, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Barzegar, M.; Raissy, M.; Shamsi, S. Protozoan parasites of Iranian freshwater fishes: Review, composition, classification, and modeling distribution. Pathogens 2023, 12, 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosymbetovich, S.E. Parasitofauna of productive fish: Lower area of the Amudarya River. Am. J. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2025, 5, 26–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atanasov, G. Fauna, Morphology and Biology on the Endohelminths of Fish from Bulgarian Part of the Danube River. Ph.D. Thesis, IEMPAM-BAS, Sofia, Bulgaria, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Mancheva, K.; Karaivanova, E.; Atanasov, G.; Stojanovski, S.; Nedeva, I. Analysis of the influence of the host body size on morphometrical characteristics of Ancylodiscoides siluri and Ancylodiscoides vistulensis. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 2009, 23, 735–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gallina, E.; Strona, G.; Galli, P. Thaparocleidus siluri, monogenoidean parasite of Silurus glanis: A new record from Italy. Parassitologia 2009, 51, 69–70. [Google Scholar]

- Sajiri, W.M.H.W.; Székely, C.; Molnár, K.; Buchmann, K.; Sellyei, B. Pathological effects of Thaparocleidus vistulensis (Siwak, 1932) infection on the gills of Silurus glanis Linnaeus, 1758. Acta Vet. Hung. 2025, 73, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sajiri, W.M.H.W.; Székely, C.; Sellyei, B. Influences of light–dark cycle and water temperature on in vitro egg laying, hatching, and survival rate of Thaparocleidus vistulensis (Dactylogyridea: Ancylodiscoididae). Parasitol. Res. 2025, 124, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bognár, A.; Borkhanuddin, M.H.; Nagase, S.; Sellyei, B. Biopsy-based normalizations of gill monogenean-infected European catfish (Silurus glanis L., 1758) stocks for laboratory-based experiments. PeerJ 2024, 12, e18288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sajiri, W.M.H.W.; Székely, C.; Molnár, K.; Buchmann, K.; Sellyei, B. Reproductive strategies of the parasitic flatworm Thaparocleidus vistulensis (Siwak, 1932) (Platyhelminthes, Monogenea) infecting the European catfish Silurus glanis Linnaeus, 1758. Int. J. Parasitol. Parasites Wildl. 2023, 22, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Normann, V.W. Drivers of Fish Parasite Infracommunities in a High Latitude System—A Dive into Host and Parasite Traits Shaping Parasite Diversity. Master’s Thesis, UiT—The Arctic University of Norway, Tromsø, Norway, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Yakhchali, M.; Tehrani, A.A.; Ghoreishi, M. The occurrence of helminth parasites in the gastrointestinal of catfish (Silurus glanis Linnaeus 1758) from the Zarrine-roud river, Iran. Vet. Res. Forum 2012, 3, 143. [Google Scholar]

- Frolova, T.V.; Izvekov, E.I.; Izvekova, G.I. First insights into the activity of major digestive enzymes in the intestine of the European catfish Silurus glanis and protective anti-enzymatic potential of its gut parasite Silurotaenia siluri. J. Fish Biol. 2023, 103, 985–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnár, K.; Székely, C. Helminth parasites of fishes from the Hungarian section of River Danube. Halászat-Tudomány (Fish. Sci.) 2024, 10, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahimova, N.E. Systematic review of catfish (Silurus glanis L., 1758) parasites within their habitat. Nematoda. Adv. Biol. Earth Sci. 2020, 5, 76–83. [Google Scholar]

- Kurbanova, A. Fish parasitofauna of the Amudarya river delta lakes. BIO Web Conf. 2024, 141, 03010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudlai, O.; Rakauskas, V.; Baker, N.J.; Pantoja, C.; Lisitsyna, O.; Binkienė, R. Helminth parasites of invasive freshwater fish in Lithuania. Animals 2024, 14, 3293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mhaisen, F.T.; Abdul-Ameer, K.N. Checklist of fish hosts of species of Contracaecum Railliet & Henry, 1912 (Nematoda: Ascaridida: Anisakidae) in Iraq. Biol. Appl. Environ. Res. 2021, 5, 281–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirin, D.; Chunchukova, M. Helminths and helminth communities of Silurus glanis (Linnaeus, 1758) from the Tundja river, Bulgaria. Sci. Pap. Ser. D Anim. Sci. 2021, 64, 42–86. [Google Scholar]

- Buchmann, K.; Karami, A.M. Fish acanthocephalans as potential human pathogens. Curr. Clin. Microbiol. Rep. 2024, 11, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soose, L.J.; Krauss, M.; Landripet, M.; Laier, M.; Brack, W.; Hollert, H.; Klimpel, S.; Oehlmann, J.; Jourdan, J. Acanthocephalans as pollutant sinks? Higher pollutant accumulation in parasites may relieve their crustacean host. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 958, 177998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mijošek, T.; Šariri, S.; Kljaković-Gašpić, Z.; Fiket, Ž.; Marijić, V.F. Interrelation between environmental conditions, acanthocephalan infection and metal(loid) accumulation in fish intestine: An in-depth study. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 356, 124358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassanine, R.; Al-Hasawi, Z. Acanthocephalan worms mitigate the harmful impacts of heavy metal pollution on their fish hosts. Fishes 2021, 6, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroe, M.D.; Guriencu, R.C.; Athanosoupolos, L.; Ion, G.; Coman, E.; Mocanu, E.E. Health profile of some freshwater fishes collected from Danube River sector (km 169–197) in relation to water quality indicators. Sci. Pap. Ser. D Anim. Sci. 2022, 65, 654–663. [Google Scholar]

- Esposito, A.; Foata, J.; Quilichini, Y. Parasitic helminths and freshwater fish introduction in Europe: A systematic review of dynamic interactions. Fishes 2023, 8, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eszterbauer, E.; Erdei, N.; Hardy, T.; Kovács, A.; Verebélyi, V.; Hoitsy, G.; Katics, M.; Bernáth, G.; Lang, Z.; Kaján, G.L. Distribution and environmental preferences of Saprolegnia and Leptolegnia (Oomycota) species in fish hatcheries in Hungary. Aquaculture 2025, 596, 741737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, P.; Raju, V.S.; Kuppusamy, G.; Rahman, M.A.; Elumalai, P.; Harikrishnan, R.; Arshad, A.; Arockiaraj, J. Pathogenic fungi affecting fishes through their virulence molecules. Aquaculture 2022, 548, 737553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Summary Report: Regional Workshop on Fish Health Management; FAO: Ankara, Türkiye, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Sahu, A.K.; Kumar, V.; Udgata, S.K.; Das, B.K. Diagnostic techniques for fish fungal diseases. In Laboratory Techniques for Fish Disease Diagnosis; Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2025; pp. 227–258. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Hellenic Society for Microbiology. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).