Abstract

Several studies have investigated airborne chemical exposures in university teaching laboratories, where activities are typically structured and supervised. University research laboratories typically involve greater autonomy, the use of more hazardous substances, and less oversight. This industry-embedded study aimed to develop a comprehensive guideline for occupational hygiene and health monitoring (OHHM) tailored to a university context, including both teaching and research laboratories. Guidelines and policies from the Western Australian mining sector and six Australian universities were analysed to identify common elements for a draft OHHM guideline. This draft was reviewed by an industry advisory group (IAG) of five Australian university health and safety managers. Their feedback was analysed and discussed with the Chief Safety Officer at Edith Cowan University (ECU). Following the incorporation of this input and final revisions, the guideline was ratified and implemented across ECU in April 2025. The guide adopts a risk-based occupational hygiene (OH) approach, in which OH monitoring results determine the need for health monitoring (HM). Implementation is supported by central coordination and external OH consultancy. The study presents the resulting guide document, which establishes a replicable framework that may inform similar initiatives in universities internationally (especially those with laboratories).

1. Introduction

Hazardous chemicals are frequently handled in university laboratories, often by students and staff who may lack sufficient experience or training, leading to an increased risk of harmful chemical exposure [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. The potential hazards associated with chemical usage in academic settings underpin the importance of investigating exposure levels to protect health and safety effectively. Several global studies investigating the levels of airborne chemicals in teaching laboratories and working spaces in universities have been conducted [1,2,8,9,10,11]. These studies generally found that while exposure levels in teaching laboratories were often below workplace exposure standards, they varied considerably depending on ventilation, chemical handling practices, and the presence of control measures. Additionally, there is limited research published on the levels of exposure in university research facilities where exposures of students and staff may be higher than those experienced in teaching laboratories [2].

Real-world incidents further highlight the need for improved chemical risk management in academic settings. Many tragic accidents have resulted from the introduction of new laboratory techniques, such as the explosion at a French university in 2006, which killed a chemistry professor, injured a student and destroyed a research building [12]. A retrospective analysis of laboratory injuries at Northwestern University in the United States of America, conducted between 2010 and 2017, found that chemical exposure was the second leading cause of injuries (19%). Despite this, the analysis revealed limited emphasis on mitigating chemical exposure risks or identifying how such injuries might be prevented [5]. These examples highlight systemic gaps in training, procedural oversight, and exposure control measures within higher education institutions.

Exposure to volatile organic compounds (VOCs) often occurs in university settings and may result in serious worker health effects, making biological monitoring an essential health and safety control. Urinary VOC biomarkers from staff (n = 30) at a Brazilian university suggested exposure to toluene, xylene, styrene, ethyl benzene, benzene, and phenyl solvents based on the quantification of hippuric acid, methyl-hippuric acid, mandelic acid, phenylglyoxylic acid and phenol [9]. The most commonly reported symptoms were headaches (58%), followed by cough/throat irritation (33%), dyspnoea (25%), and numbness (25%) [9]. In Germany, a survey of 11 medical university institutes identified 13,764 different chemical substances associated with teaching and research activities, and there was a lack of occupational health surveillance for students and a need for occupational health services for staff members [3]. A Japanese study of chemical exposures in university laboratories led to the implementation of personal exposure monitoring and training of students and staff on the toxicity of various chemicals and the proper use of protective equipment, to minimise risks associated with the chemicals used [2].

Venables and Allender [1] reviewed 58 studies examining occupational health provisions in universities worldwide and concluded that universities are typically large institutions characterised by numerous small-scale hazards that often lack a centralised organisational structure and clear delineation of responsibility for managing occupational health and safety across their campuses. Work involving laboratory research, chemical handling, equipment use, and experimental procedures is often carried out with little training and supervision, and researchers tend to work in new fields where there is little information about risk. It was also found that most universities surveyed had no occupational health services, even though many employees had a high-risk exposure profile [1].

An emerging health concern in academic institutions is the increasing use of three-dimensional (3D) printing technologies. These printers, which create objects by layering materials based on digital designs, are being integrated into various university departments for prototyping, manufacturing, and design purposes. While they offer significant technological benefits, there is growing evidence that 3D printers emit ultrafine particles (UFPs) and VOCs during operation, which may pose health risks to users [13]. Studies have identified emissions, including formaldehyde, acetaldehyde, styrene, toluene, and acetone, substances known to have adverse health effects. The concentration and composition of these emissions can vary based on factors such as the type of filament used, printer settings, duration of printing, and the effectiveness of ventilation systems. Given the potential for exposure to these harmful substances, especially in poorly ventilated or enclosed spaces, it is imperative for institutions to assess and mitigate the associated health risks [13]. An industry-based study conducted in 2025 [14] drew attention to the critical gaps in occupational health and safety knowledge related to additive manufacturing (AM) technologies, including 3D printing. The findings depict significant knowledge deficiencies among AM users, particularly regarding safety training, chemical exposure risks, and emission controls. Their investigation, derived from a comprehensive international survey and focus groups, shows that while AM technology users recognise general operational practices, there is considerable uncertainty about the appropriate management of health risks associated with VOCs, particulate matter (PM), and chemical exposures inherent in various AM processes. These gaps are exacerbated by the rapidly evolving nature of technology and the absence of comprehensive, standardised safety training programmes. Consequently, there is a pronounced need for improved education, systematic risk assessments, and standardised safety protocols to adequately protect individuals involved in AM processes, particularly in educational and research environments [14].

In Australia, a large survey of 33 universities focusing on the institutional response to risks in university laboratories was conducted. It found that the amount of occupational health and safety training provided to students and staff varied greatly, and content was infrequently assessed. Furthermore, it was reported that chemical risks and airborne exposures amongst university staff and students were not regularly assessed [15]. A subsequent study [16] evaluated VOC levels indoors as compared to outdoors in a large university in Melbourne and reported that formaldehyde, toluene, p-xylene, m-xylene, o-xylene and benzene were up to an order of magnitude higher indoors when compared with outdoors. In Western Australia, the state where ECU is located, a Curtin University study assessed indoor air quality in 15 laboratories. VOCs, ultra-fine particles (UFP)s and different size fractions of particulate matter, less than 10 micron in diameter (PM10) and less than 2.5 micron in diameter (PM2.5) were assessed during the semester and over the semester break and the respiratory health of tutors and technicians was also evaluated by administering a questionnaire. Participants who reported symptoms of coughing and trouble breathing had been employed in a laboratory environment for longer (p = 0.007 and p = 0.005, respectively) than their asymptomatic peers, and those who reported respiratory problems were exposed to higher levels of VOCs and PM10 compared to participants who did not report respiratory symptoms. It was found that significantly higher exposures for total VOCs, PM10, PM2.5 and UFPs were measured during the semester compared to the semester break. The results from this study suggest that further investigation into the relationship between indoor air quality in university laboratories and the adverse health effects amongst their occupants is necessary, and it was concluded that staff who spend more time in these laboratories are at a greater risk of developing adverse health effects [11].

Universities are generally large organisations, with a wide range of hazards that usually occur on a small scale and intermittently in a teaching environment. However, research environments involve exposures that are of longer duration, and staff and students also work in new fields where hazards are not well quantified. Universities often operate in a siloed fashion and lack centralised organisational structures regarding the management of work health and safety (WHS) issues, and work is often conducted with little training and supervision [16]. Chemical exposures among both students and staff are known risks in most universities, with common solvents including various alcohols, ketones, and chlorinated compounds [2]. There is a lack of focus in most universities on the management of chemical exposures [5]. Training is a crucial aspect of risk management that is often poorly implemented and managed. It is important that students and staff have adequate knowledge regarding the toxicity of the chemicals being used and that adequate control measures are in place, such as fume cupboards and protective equipment [2]. Younger staff are significantly more likely to be aware of the hazards associated with chemicals [10].

There is a lack of published research on health monitoring among university staff and students, and a significant gap in knowledge related to exposures in academic laboratories, particularly those assessed through personal monitoring. Without a robust occupational hygiene programme, universities are unable to adequately assess risks for staff and students, determine the need for health monitoring, or implement appropriate control measures and PPE. This study aimed to develop an industry best-practice guide for the management of chemical exposure assessment and health monitoring in universities. Specifically, it presents the development and validation of a risk-based occupational hygiene and health monitoring (OHHM) guide tailored to the university context. The guide integrates best practices from the industry and leading Australian universities, incorporates expert feedback through an industry advisory group, and establishes a replicable framework that can be adopted or adapted by other institutions to improve laboratory safety governance and chemical risk management.

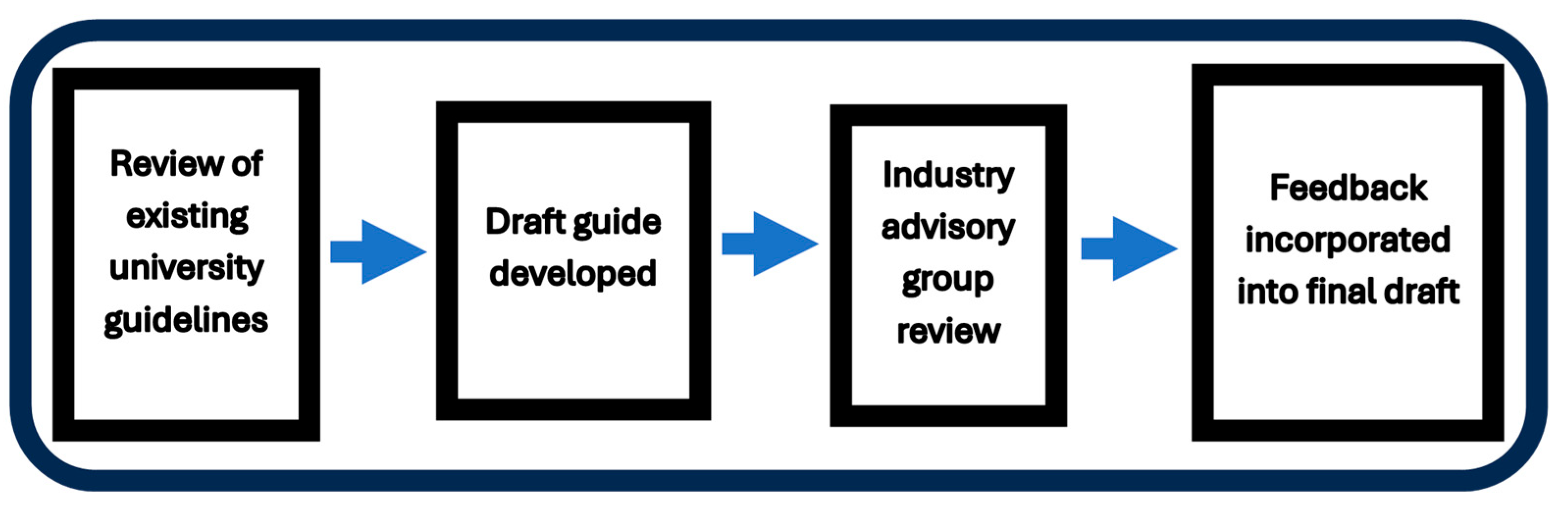

The development of the university-specific OHHM guide was conducted following four phases, as depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Development of a university occupational hygiene and health monitoring guide.

Although university laboratory environments differ substantially from mining operations, the Western Australian mining regulator’s OHHM guide was selected as a benchmark because it represents one of the most mature, regulator-endorsed occupational hygiene systems in Australia and has been refined over several decades. The structured, risk-based methodology detailed in the guide is transferable to other complex environments involving diverse hazards and variable exposure scenarios, such as universities.

2. Methods

2.1. Review of Existing OHHM Guidelines and Development of the First Draft

The Department of Energy, Mines Industry Regulation and Safety (DEMIRS), which is the State Government regulator for the mining sector in Western Australia, has developed and evaluated refined occupational health and hygiene guidelines for the mining sector over an extended period. Therefore, the latest version of the DEMIRS guide was initially reviewed as an example of industry best practice [17]. Subsequently, a list of all Australian universities (n = 42) was obtained from an Australian Federal Government website [18], and policy searches were conducted on each individual university website to locate occupational health and safety (OHS) policies. Only six university guidelines were identified that specifically addressed OHHM.

The seven OHHM-related guidelines listed in Table 1 were summarised using a table format to capture key features of each guide. For a more detailed analysis, refer to the Supplementary Material Tables S1–S7.

Table 1.

University/industry documents reviewed for occupational hygiene and health monitoring protocols.

Common themes were identified, and these were incorporated into the first draft of the university’s OHHM guide. Other university guidelines and policy documents in use by ECU provided a template to ensure that the guide followed the university’s corporate formatting style. The document was reviewed by the ECU Chief Safety Officer.

2.2. Industry Advisory Group

The first draft of the ECU guide was circulated amongst peers and supervisors at the university for refinement before being sent to an Industry Advisory Group (IAG). Eighteen managers of occupational health and safety/WHS at Australian universities were invited to review the draft document and to provide feedback and suggestions for improvement. Despite several follow-up attempts, only four universities provided feedback; two were regional institutions, and two were larger metropolitan universities.

2.3. Final Draft

The feedback obtained from the IAG was robust and constructive. Overlapping themes and suggestions were identified and used to revise the initial draft of the guide. The revised draft was subsequently reviewed by the ECU Chief Safety Officer to ensure alignment with institutional procedures and legislative requirements. After incorporating this feedback, the final version of the guide was ratified in April 2025 and distributed to operational units across the university for implementation.

3. Results and Discussion

It was found that six (14%) of all Australian universities (n = 42) had developed OHHM guidance material. A total of 14 (33%) universities refer to their legal obligations to provide occupational hygiene or health monitoring, but do not provide specific guidelines on how this should be achieved. Almost half of the universities (n = 20) had no guidance documentation for occupational health and hygiene monitoring. The next section provides a brief summary of the reviewed guideline documents that led to the identification of common themes that were used in the development of the ECU guide.

3.1. Summary of Reviewed Documents

The Australian Catholic University had the most comprehensive and robust health and air monitoring procedure. Their guideline is a mature and well-designed procedural document that provides detail on how the programmes are to be developed and executed [19]. James Cook University also has a mature and well-developed procedure specifically aimed at occupational hygiene management of health hazards. However, it excludes health monitoring [20].

The University of Melbourne document excludes the word hygiene from the title, and guidance is largely based on the outcomes of health risk assessments, which inform the need to conduct occupational hygiene monitoring. Staff complete a health hazard activity questionnaire that is reviewed by the health and safety systems team, and a decision is made about the need for health monitoring. This approach differs from the norm, where hygiene sampling quantifies the risk and informs the need for health monitoring [21].

The guidelines of the University of New England and those of the University of Wollongong lack detail on process and procedure [22,23].

The OHHM guidance material that has been developed in Western Australia by the State Government regulator for mine health and safety (DEMIRS) over several decades was used as an industry best practice framework for this study. It is a statutory requirement that all mining operations in the State need to develop hygiene and health monitoring plans, and they must also report their monitoring results to the regulator using a sophisticated online reporting system. The DEMIRS OHHM guideline was developed to ensure compliance, and it is detailed, reflecting the complexity, size and scope of mining operations. The guide consists of five main sections, as shown in Figure 2 [17].

Figure 2.

DEMIRS procedure for implementing OHHM programmes in WA mining operations. Reproduced from [17] Government of Western Australia, Department of Mines, Industry Regulation and Safety, 2018, p. 10.

Given the contextual differences between mining operations, steps one (describe operation), two (identify hazards and controls) and three (assess the risk) are extremely complex, and they could effectively be combined into one new category that describes the process of risk characterisation and hazard assessment for application in a university environment.

Step four, “verify controls”, is the part of the guide that deals with both hygiene and health monitoring. This is the component that is lacking across most of the university sector. Occupational hygiene results provide the data needed to make decisions about personal exposures and the need for health monitoring. In contrast to the university sector, the mining sector has a long history of implementing both occupational hygiene and occupational health monitoring and decisions regarding health monitoring are based on the outcomes of hygiene work. If the levels of exposure are unknown, then it is not possible to conduct a well-informed health risk assessment. For application in a university environment, these two components could be separated into two distinct phases, namely “occupational hygiene monitoring” and “health monitoring”, an approach that is reflected in most of the university processes previously discussed. The final stage of the DEMIRS framework is entitled “improvement identified”; this is the section dealing with the interpretation of data and implementation of controls in a cycle of continuous evaluation and improvement. This section for application in a university context could be renamed “evaluation and control”.

The Curtin University guide was based on the DEMIRS guideline, and it follows the same framework. Since universities are not as complex as mining operations, several sections of this very detailed guide could have been combined for use in a university environment [24].

A detailed summary of the reviewed documents is contained in Supplementary Tables S1–S6.

3.2. Analysis of Guidance Documents

To support cross-institutional comparison, a content analysis was conducted focusing on policy intent, implementation processes, and mechanisms for oversight. Key elements from each guideline were grouped under three overarching themes, which are as follows:

- (1)

- Governance and scope

This includes policy, scope, background and context, legislative framework, definitions and delegations or responsibilities.

- (2)

- Process

Providing details on risk-based hygiene and health monitoring, including verification of controls.

- (3)

- Reporting and resources

Provides details around legal obligations and reporting, record keeping, further assistance, and provides links to external resources and version control.

Table S7 in Supplementary Materials presents a summary of how these elements are addressed across the six reviewed university and industry guidelines. The categories were used to consistently capture functionally similar content, even when structured differently across institutions. The numbering shown in the table refers to the original section numbers used within each document and reflects their internal sequence only; it does not indicate priority or importance.

3.3. Development of the ECU OHHM Guide

The University of Wollongong OHHM guide is the only reviewed document that followed a logical naming convention by placing the words “air monitoring” before “health monitoring”. Occupational hygiene results provide the data about personal exposures that are needed to identify where health monitoring may be required, and so this is a more correct way of naming the guidelines. Therefore, the naming convention adopted for ECU was to place the word “hygiene” first, “occupational hygiene and health monitoring”, although the abbreviation generally used is unchanged (OHHM).

All seven of the OHHM procedures reviewed broadly followed the same principles of initially performing a hazardous substances audit, followed by a risk assessment that informs the need for hygiene monitoring. The results of a hygiene program and another risk assessment then led to the development of a health monitoring program, with the exception being the University of Melbourne, where health monitoring is recommended directly. Australian universities, including ECU, already have chemical safety management systems, and Faculties/Schools are discrete management units responsible for implementing their own chemical management systems. The size and scope of operations at universities are relatively large, but not on the scale experienced in the mining sector, and much of the detail in the DEMIRS guide is not relevant in a university context.

The three themes that emerged from the review provided the framework for the development of the draft ECU OHHM guideline.

Theme 1 describes the scope of the guide with reference to relevant Federal and State legislation, followed by the ECU WHS policy framework and where this guide fits into the university governance structure. This section also includes references and links to relevant policy documents and internal processes for chemical management and risk assessment. The section concludes by detailing roles and responsibilities for the implementation of the OHHM programme.

Theme 2 details the process of how the occupational hygiene programme must be developed and refers to sampling methods and requirements for equipment calibration and statistical analysis, as well as links to workplace exposure standards (WESs) and other resources. The development of the health monitoring program is to be informed by the occupational hygiene monitoring program, leading to a fully integrated hygiene and health monitoring procedure. The integrated OHHM guide is structured around four sequential components:

- (1)

- Risk characterisation and hazard assessment;

- (2)

- Development of an occupational hygiene programme;

- (3)

- Implementation of occupational health monitoring;

- (4)

- Evaluation and control.

These components collectively describe the progression from hazard identification through to monitoring outcomes and control effectiveness and form the basis of the framework described below.

Risk characterisation and hazard assessment

A chemical audit using existing ECU systems, such as Riskware and ChemAlert and Safety Data Sheets, will be conducted. Broadly, the audit will include the following steps.

- A detailed process description that will identify activities that are related to teaching and research, stratified as needed for teaching, research, students, as well as technical and academic staff.

- Hazards and current controls.

- Risk characterisation (exposure profiles for groups).

- Allocation of similar exposure groups (SEGs).

- A team-based qualitative risk rating will be assigned to each SEG (low, medium, high, or extreme).

Occupational Hygiene Programme

The occupational hygiene sampling programme will be informed by the outcomes of risk characterisation and hazard assessment, and it will involve a baseline assessment of chemical exposures in many cases. All occupational hygiene monitoring will be undertaken using approved methods as detailed in Australian Standards or by other appropriate agencies such as the National Institute of Occupational Health and Safety (NIOSH), and the United States Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). All sampling equipment must be calibrated, and any external analysis of samples will be completed in National Association of Testing Authorities (NATA) approved laboratories using endorsed testing methodologies.

The number of samples to be collected for exposure assessment will be guided by the number of people exposed, as detailed by the compliance monitoring strategy of Leidel [25]. Exposure data will be analysed using Industrial Hygiene Statistics (IHSTAT) software (AIHA 2023) that compares the sample data to the relevant WES. The geometric standard deviation (GSD) will confirm the validity of SEG classifications prior to further analysis being undertaken (GSD < 3). For exposures associated with chronic health effects, the arithmetic mean and the 95% upper confidence limit (UCL) mean will be assessed. The percentage of predicted WES exceedances will also be determined and should be <5%. For acute health effects, maximum exposures will be assessed by examining the 95th percentile value and the 95% upper tolerance limit (UTL) of the 95th percentile to ensure that the WES is below this value [15]. These statistical decision-making rules are derived from widely used occupational hygiene practice and provide for a conservative, precautionary approach.

A health and hygiene register will be established to document all exposure data and controls. The exposure data will be used to identify areas where additional monitoring will be required and where controls need to be implemented, as well as the frequency of follow-up sampling over the next five years. The frequency of re-assessment will be based on geometric means of the data as recommended by Ogden and colleagues [26].

All occupational hygiene sampling will be conducted by, or under the supervision of a suitably qualified Occupational Hygienist, or where statutory monitoring is required, a Certified Occupational Hygienist (COH), and all methods will be validated standard methods as described by NIOSH [27] and relevant Australian standards. Where samples are sent off for external analysis, only laboratories with NATA accreditation for those methods will be used. All equipment used will be serviced and will have current calibration certification.

Occupational Health Monitoring

The physical presence of chemical agents does not necessarily imply a high risk of exposure, and so the first stage of this process is to conduct a team-based qualitative risk assessment to assess the need for health monitoring. The health monitoring programme will be developed using the occupational exposure data and team-based risk assessments that will consider, in addition to measured exposure levels, aspects such as frequency and duration (time component) of activities leading to chemical exposures. This health monitoring risk assessment will be conducted using the matrix published in the health and hygiene management guide, which can be accessed online [17]. In this matrix, similar exposure groups are assigned to the qualitative risk categories of low, medium, high or unacceptable. This semi-quantitative scoring system combines hazard, exposure levels, frequency and duration, along with an assessment of the effectiveness of existing controls to guide risk-based decision making.

The Safe Work Australia [28] guidelines for health monitoring, for chemicals listed in Appendix A and the associated checklist (Appendix B) of the guideline are to be used to develop the health monitoring programme. The health monitoring program is developed based on the outcomes of the occupational hygiene data and a team-based qualitative risk assessment.

Evaluation and control

Where deemed appropriate, exposure controls are to be developed, implemented and re-evaluated to ensure they are effective in an ongoing cycle of continuous improvement.

Theme 3 details administrative management arrangements and delegations, such as responsibilities for funding of the programme and the maintenance of records.

ECU have a standard format for policy documents and guidelines, and so it was the three theme areas previously identified had to be incorporated into the university guideline template. The following layout was agreed upon in consultation with the ECU Chief Safety Officer.

Section 1 outlines the purpose and intent of the document.

Section 2 defines the organisational scope.

Section 3 provides key definitions.

Section 4 covers the core content of the guide, describing the details of how hygiene and health monitoring will be implemented at the university.

Section 5 specifies accountabilities and responsibilities for the programme.

Section 6 lists related documents, policies, and operational resources.

Sections 7 and 8 provide contact information and the approval history.

3.4. Input from the IAG

The feedback received from the (IAG) was robust, practical, and informed by significant experience managing occupational health and safety in university settings. This consultation process was instrumental in shaping the ECU draft guideline, ensuring that it was both operationally relevant and aligned with sector needs. The key areas of feedback are summarised in Table 2 below.

Table 2.

Reviewer feedback on initial OHHM guide.

Although only four of the invited university health and safety managers participated in the IAG, the perspectives captured do reflect universities that have a good level of occupational hygiene and health monitoring maturity, and their feedback was insightful.

The IAG feedback included recommendations on improving terminology, clarifying responsibilities, aligning the guideline with existing university systems, and ensuring flexibility for varied institutional contexts. The feedback provided a valuable external lens through which the draft could be refined and validated. The involvement of the IAG enhanced the credibility and real-world applicability of the guideline, supporting its broader relevance across the university sector, and this university-specific OHHM guide is transferable to other institutions. In jurisdictions outside of Western Australia, it may need to be adapted for a local context.

The following overlapping themes and suggestions have been extracted from the feedback and were all used to improve the guide.

- Defining Roles and Processes:

Both reviewers 2 and 3 stressed the need to clearly define who conducts risk assessments and health monitoring. They suggested that the process should apply broadly to all staff potentially exposed to various hazards, and that the need for health monitoring should be evaluated on a case-by-case basis. Reviewer 3 emphasised that using historical exposure/air monitoring data could be used to decide if monitoring is necessary, while reviewer 2 discussed how monitoring can be non-statutory and may involve oversight by different professionals.

- Budgeting, Accountability, and Record-Keeping:

Both reviewers 1 and 2 identified the need to clarify responsibilities regarding budgeting, record storage and data privacy, and they noted that these accountabilities could be contained in a supporting policy or procedure. This feedback highlights the importance of clear allocation of responsibilities and management of records.

- Silica Management:

Reviewer 1 recommended including references to respirable silica and its management, which was supported by reviewer 3, who commented by noting the difficulties in detecting crystalline silica. This suggests that it might be overlooked in standard assessments due to its similarity to common materials like silicon dioxide. Together, these points underpin the need for specific attention to silica exposures in the guide.

- Keeping Guidelines Up to Date:

Reviewer 1 suggested consulting information from various jurisdictions (referencing SafeWork NSW) to ensure comprehensive guidance. Reviewer 2 questioned the currency of the regulatory framework and whether it was correctly referenced. The references were subsequently checked and verified to be current.

- Special Cases in Regulation:

While not directly overlapping with others, reviewer 3 raised additional issues, such as radiation monitoring, that may fall outside the typical scope of hazardous chemicals management but are still important. Fortunately, ECU has a committee dedicated to looking at this RBHSC—may be worth noting here.

- Additional Comments:

Reviewer 1 recommended that the plan be reviewed by an Occupational Hygienist, which complements the overall need for expert validation mentioned indirectly by reviewers 2 and 3 when discussing risk assessments and monitoring protocols. Reviewer 3 added details on topics like eye testing for LASER users, noting practical challenges with completion of follow-up testing. Although this is not directly echoed in the other feedback, it aligns with the broader theme of tailoring health monitoring to specific hazards and operational challenges. Input received from the IAG enhanced the clarity and practical operational aspects of the ECU guide by thus ensuring that the document provides clear, broadly applicable guidance that is suitable for assessing all hazard types encountered in university laboratory and research environments.

3.5. Finalisation of the ECU OHHM Guide April 2025

After feedback from the IAG was incorporated into the draft guide, it was provided to the ECU Chief Safety Officer for review. A meeting was held to discuss minor editorial adjustments required to align the document with ECU’s internal processes and institutional context. Following these revisions, the document was formally ratified and circulated to operational units across the university for implementation. To support the rollout, the university engaged an external occupational hygiene consultancy, coordinated centrally by the Office of the Chief Safety Officer. This centralised coordination provides a systems-level implementation framework, ensuring consistent application of the guide across schools and departments. It also allows for structured oversight of exposure assessments, SEG development, and follow-up actions. The final version of the guideline is accessible via a link https://intranet.ecu.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/1115639/Occupational-Hygiene-Monitoring-Guideline.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2025), also accessible in the Supplementary Materials on page 31. It serves as a template that may be adapted by other universities.

A key limitation in developing this guide was the lack of robust, university-specific systems already in place, along with a low response rate from universities invited to provide feedback through the industry advisory group. This limited engagement may reflect that most universities did not yet have such systems established. While the core concepts of risk characterisation, hygiene monitoring, health monitoring and continuous improvement are broadly applicable, further work is needed to test and refine the framework in universities.

4. Conclusions

The ECU OHHM guide was developed through a structured process that drew on an extensive review of industry best practice guidelines and policies developed by the Western Australian mining regulator. This was supported by an analysis of current guidance materials used by other Australian universities. After consultation with an Industry Advisory Group, the guide was finalised and implemented at ECU in April 2025. The OHHM Guide was designed to be a practical, university-specific framework that can also serve as a model for other Australian universities. This guide is transferable to universities internationally; however, for application outside Australia, it would need to be adapted to align with local regulatory systems, including different workplace exposure standards and institutional governance structures. The limited number of universities that contributed detailed feedback to the IAG means that there are opportunities to conduct further validation and evaluation after implementation before the guide can be regarded as broadly representative of the sector. The guide will be reviewed annually at ECU. In the longer term, universities elsewhere could adopt a similar development process by reviewing existing occupational health and hygiene management guides within their own country and engaging with local experts to create a guide that reflects national standards and institutional needs.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/laboratories3010001/s1. Tables S1–S6: Detailed breakdown of the content and structure of occupational hygiene and health monitoring (OHHM) guidance related documents from six Australian universities. Each table presents thematic content mapping across governance, process, and reporting elements. Table S7: Sections and themes extracted from OHHM guidelines in Australian universities and DEMIRS. Supplementary Document: Finalised Occupational-Hygiene-Monitoring-Guideline.pdf, for ECU, ratified in April 2025.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.O.; Methodology, M.O., K.P., and A.L.; Investigation, M.O., K.P., M.C., and A.L.; Data acquisition, M.O., M.C., and A.L.; Data interpretation, M.O.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, M.O.; Writing—Review and Editing, K.P. and A.L.; Visualisation, M.O.; Supervision, K.P., M.C., and A.L.; Project Administration, M.O., K.P., M.C., and A.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This specific research received no external funding. This research was supported by the Commonwealth through an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Edith Cowan University (protocol code 05569-CATTANI, 29 October 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Written consent was not required as per the conditions of ethics approval 2024-05569-Cattani. Participants were invited via email to voluntarily provide professional feedback on the draft guide.

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the findings of this study are contained within the article and its Supplementary Materials.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Kim Mcclean, Chief Safety Officer at Edith Cowan University, for her support and expert review during the development of the guideline. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT (GPT-4, OpenAI, 2025) to assist with structural editing. All outputs were reviewed and revised by the authors. All final textual and conceptual decisions remain the responsibility of the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AM | Additive manufacturing |

| CDC | Centres for Disease Control and Prevention |

| COH | Certified occupational hygienist |

| DEMIRS | Department of Energy, Mines Industry Regulation and Safety |

| ECU | Edith Cowan University |

| GSD | Geometric standard deviation |

| HM | Health monitoring |

| IAG | Industry advisory group |

| IHSTAT | Industrial Hygiene Statistics |

| NATA | National Association of Testing Authorities |

| NIOSH | National Institute of Occupational Health and Safety |

| OH | Occupational hygiene |

| OHHM | Occupational hygiene and health monitoring |

| OHS | Occupational health and safety |

| PM | Particulate matter |

| RBHS | Radiation, biosafety and biosecurity and chemicals and hazardous substances |

| SEG | Similar exposure group |

| UCL | Upper confidence limit |

| UFPs | Ultrafine particles |

| UTL | Upper tolerance limit |

| VOC | Volatile organic compound |

| WESs | Workplace exposure standards |

| WHS | Work health and safety |

References

- Venables, K.M.; Allender, S. Occupational health needs of universities: A review with an emphasis on the United Kingdom. Occup. Environ. Med. 2006, 63, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takada, S.; Okamoto, S.; Yamada, C.; Ukai, H.; Samoto, H.; Ohashi, F.; Ikeda, M. Chemical exposures in research laboratories in a university. Ind. Health 2008, 46, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rombeck, A.; Schacke, G. Umgang mit Gefahrstoffen und Umsetzung der Gefahrstoffverordnung an Hochschulinstituten aus arbeitsmedizinischer Sicht [Handling of hazardous substances and the implementation of the ordinance governing hazardous substances at university institutes seen in the light of occupational medicine]. Zbl. Arbeitsmed. 2000, 50, 114–127. [Google Scholar]

- Rojas-Martini, M.; Squillante, G.; Espinoza, C. Condiciones de trabajo y salud de una universidad venezolana. Salud Pública Méx. 2002, 44, 413–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gosavi, A.; Schaufele, M.; Blayney, M. A retrospective analysis of compensable injuries in university research laboratories and the possible prevention of future incidents. J. Chem. Health Saf. 2019, 26, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugivhisa, L.L.; Baloyi, K.; Olowoyo, J.O. Adherence to safety practices and risks associated with toxic chemicals in the research and postgraduate laboratories at Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences, Pretoria, South Africa. Afr. J. Sci. Technol. Innov. Dev. 2021, 13, 747–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahab1, N.A.A.; Aqila, N.A.; Isa, N.; Husin, N.I.; Zin, A.M.; Mokhtar, M.; Mukhtar, N.M.A. A systematic review on hazard identification, risk assessment and risk control in academic laboratory. J. Adv. Res. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2021, 24, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, M.; Zakaria, A.; Balkhyour, M. Implementation of Chemical Health Risk Assessment (CHRA) program at chemical laboratories of a university. J. Saf. Stud. 2017, 3, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- De Deus Honório, T.C.; de Oliveira Neto, J.R.; Oliveira, F.N.M.; Salazar, V.C.R.; de Carvalho Cruz, A.; da Cunha, L.C. Occupational exposure evaluation of Brazil university community to the volatile organic compounds. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2020, 191, 113637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papadopoli, R.; Nobile, C.G.A.; Trovato, A.; Pileggi, C.; Pavia, M. Chemical risk and safety awareness, perception, and practices among research laboratories workers in Italy. J. Occup. Med. Toxicol. 2020, 15, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rumchev, K.; Van Den Broeck, V.; Spickett, J. Indoor air quality in university laboratories. Environ. Health 2003, 3, 11–19. [Google Scholar]

- Freemantle, M. Blast Kills French Chemistry Professor; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Baguley, D.A.; Evans, G.S.; Bard, D.; Monks, P.S.; Cordell, R.L. Review of volatile organic compound (VOC) emissions from desktop 3D printers and associated health implications. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kukko, K.; Viitanen, A.K.; Chekurov, S.; Ituarte, I.F. Is the workforce ready? A look at operational health and safety in additive manufacturing. Saf. Sci. 2025, 187, 106842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, V.; Cobbin, D.; Logan, P. Examination of the Occupational Health and Safety Initiatives Available within the Chemistry Departments of Australian Universities. J. Chem. Educ. 1999, 76, 1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, N.B.; Wheeler, A.J.; Paevere, P.J.; Selleck, P.W.; Cheng, M.; Steinemann, A. Indoor volatile organic compounds at an Australian university. Build. Environ. 2018, 135, 344–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Western Australia, Department of Mines, Industry Regulation and Safety. Preparation of a Health and Hygiene Management Plan—Guide. 2018. Available online: https://www.worksafe.wa.gov.au/system/files/documents/2025-04/MSH_G_HHMP.pdf (accessed on 24 August 2024).

- List of Australian Universities|Study Australia. 2025. Available online: https://www.studyaustralia.gov.au/en/plan-your-studies/list-of-australian-universities (accessed on 26 August 2024).

- Australian Catholic University. WHSMS Health and Air Monitoring Procedure/Document/Policy Library. 2020. Available online: https://policy.acu.edu.au/document/view.php?id=176 (accessed on 26 August 2024).

- James Cook University. Occupational Hygiene Management Procedure. 2024. Available online: https://www.jcu.edu.au/policy/university-management/whs-management/whs-pro-012-occupational-hygiene-management-procedure (accessed on 26 August 2024).

- University of Melbourne. Health and Safety Occupational Health Monitoring Guidance. 2024. Available online: https://safety.unimelb.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/4823443/occupational-health-occupational-health-monitoring-guidance.pdf (accessed on 26 August 2024).

- University of New England. WHS OP013 Hazardous Chemicals Procedure/UNE Policy Register. Une.edu.au. 2017. Available online: https://policies.une.edu.au/view.current.php?id=21 (accessed on 26 August 2024).

- University of Wollongong. Air and Health Monitoring Guidelines. 2025. Available online: https://documents.uow.edu.au/content/groups/public/@web/@ohs/documents/doc/uow072426.pdf (accessed on 26 August 2024).

- Curtin University. Health and Hygiene Management Plan. 2022. Available online: https://www.curtin.edu.au/healthandsafety/wp-content/uploads/Health-Hygiene-Management-Plan.pdf (accessed on 26 August 2024).

- Leidel, N.A. Occupational Exposure Sampling Strategy Manual; No. 77-173; US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, Public Health Service, Center for Disease Control, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health: Washington, DC, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Ogden, T.K.; Hirst, A.H.; Hommes, K.; Ingle, J.; van Rooij, J.; Kennedy, A.; Scheffers, T.; van Tongeren, M.; Tielemans, E. 3.8 Reassessment in Testing Compliance with Occupational Exposure Limits for Airborne Substances; British Occupational Hygiene Society: Derby, UK, 2011; pp. 24–25. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). NIOSH Manual of Analytical Methods (NMAM), 5th ed.; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2020. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/nmam/default.html (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Safe Work Australia. Health Monitoring for Persons Conducting a Business or Undertaking: Guide; Safe Work Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2020. Available online: https://www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au/doc/health-monitoring-persons-conducting-business-or-undertaking-guide (accessed on 12 May 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.