Abstract

Background/Objectives: People with MS continue to experience relapses despite the use of disease-modifying therapies. This has motivated growing interest in the potential of non-pharmacological factors to reduce relapse risk. However, previous studies have been heterogeneous, and current clinical guidelines lack clarity on which measures should be incorporated into routine care. We aim to conduct an umbrella review of systematic reviews with meta-analyses to determine the current evidence on non-pharmacological exposures associated with relapse risk in MS. Methods: We searched PubMed, Embase and Cochrane to identify systematic reviews with meta-analyses that evaluated the association between non-pharmacological exposures and relapse risk. We included observational studies that reported on relapses as an outcome. The effect sizes (relative risk [RR] or standardized mean difference [SMD]) and certainty of evidence were assessed using components of the GRADE framework. Results: We screened 3366 articles and identified 11 systematic reviews for inclusion. Protective factors were breastfeeding (RR 0.63, high certainty), pregnancy (SMD −0.52, moderate certainty), menopause (SMD −0.5, low certainty), autumn months (RR 0.97, moderate certainty) and increasing levels of vitamin D (RR 0.9, low certainty). Risk factors were early postpartum period (RR 1.87, moderate certainty) and stress (d = 0.53, moderate certainty). Influenza vaccination (low certainty), COVID-19 infection (low certainty), and vitamin D levels above 50 nmol/L (low certainty) were not statistically associated with relapse risk. Conclusions: Our umbrella review highlights the need for more robust studies to strengthen the certainty of evidence on non-pharmacological exposures and relapse risk in people with MS. Current findings support promoting breastfeeding, careful disease management throughout the pregnancy–postpartum period, and the implementation of stress mitigation strategies.

1. Introduction

Multiple sclerosis is an inflammatory disease of the central nervous system characterized by gliotic scarring in areas of chronic demyelinated plaques [1]. Relapses are defined as acute or subacute episodes of new or increasing neurologic dysfunction followed by full or partial recovery [2]. Disability in the course of MS may be driven by the occurrence of relapses (relapse-associated worsening) as well as by progression independent of relapse activity (PIRA) [3]. Relapses are key drivers of disability accumulation, particularly in the early years of the disease [3]. Current treatments aim to control inflammatory activity, but a curative approach is still not available for MS. Therefore, relapse control remains a central goal in both clinical practice and research.

However, clinical relapses still occur even in patients receiving high-efficacy treatments [4,5], and this is one of the reasons for switching therapies [6,7]. Moreover, patients frequently seek evidence-based, non-pharmacological strategies to reduce relapse risk, yet the recommendations provided in routine clinical practice remain highly heterogeneous [8]. Over the past decades, an increasing number of systematic reviews and meta-analyses have evaluated relapse risk across diverse exposures, resulting in a fragmented evidence base that has not yet been comprehensively appraised [9].

This background creates a timely rationale for conducting an umbrella review of systematic reviews. Our goal was to identify which exposures have high-quality evidence of increasing or decreasing relapse risk, in order to guide patient education and improve relapse prevention.

2. Methods

We conducted an umbrella review of non-pharmacological exposures as risk factors for multiple sclerosis (MS) relapse. This study complies with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) reporting guideline, adapted for umbrella reviews. The umbrella review was registered retrospectively in Open Science Framework at https://osf.io/69f43/ (accessed on 26 November 2025). A systematic search of PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane databases was performed from inception to 20 March 2025, to identify systematic reviews and meta-analyses of observational studies involving patients with MS that evaluated the association between various exposures and the occurrence of MS relapses. Search terms included: Pubmed ((“systematic review” ) OR (meta-analysis )) AND (“multiple sclerosis” ) AND ((activity ) OR (relapse ) OR (recurrence )); Embase ((‘systematic review’ ) OR (meta-analysis )) AND (‘multiple sclerosis’ ) AND ((activity ) OR (relapse ) OR (recurrence )); and Cochrane ((“systematic review” ) OR (meta-analysis )) AND (“multiple sclerosis” ) AND ((activity ) OR (relapse ) OR (recurrence )). No filters were used. The inclusion criteria were systematic reviews with meta-analyses of observational studies that analyzed non-pharmacological risk factors for MS relapses. We excluded: meta-analyses that included disease-modifying drugs as exposures, umbrella reviews, meta-analyses investigating only genetic risk factors, meta-analyses assessing MS incidence or disease progression without relapses, meta-analyses of interventional studies, meta-analyses without quantitative synthesis, and meta-analyses of studies lacking a comparative control group.

Potentially eligible articles were reviewed in full and independently by two investigators (ST and GDS). Any conflicts were resolved by consensus. Duplicate articles were initially screened and excluded using a semi-automated system via Rayyan online software version 2025 [10] and were manually verified by the authors. For each individual risk factor, we included the most recent study that met the inclusion criteria.

Data extraction was performed by two independent investigators (ST and GDS). In case of discrepancies, the final decision was reached by consensus after review. For each included article, we extracted data on: the specific risk factor, journal and year of publication, number of primary studies included, summary effect size and effect size of the largest included study (with corresponding 95% confidence interval), total number of cases and controls, heterogeneity estimates (I2), publication bias assessment (Egger’s test p-value or funnel plot analysis), and the type of effect size reported (relative risk [RR] or standardized mean difference [SMD]). The certainty of evidence and the presence of biases were assessed using components of the GRADE framework, considering whether associations remained after excluding studies at high risk of bias, the presence of imprecision (confidence intervals excluding 1 and more than 1000 participants), inconsistency (I2 > 50%), and publication bias (Egger’s test). Lack of reporting on these aspects was considered a reason for downgrading the certainty of evidence.

3. Results

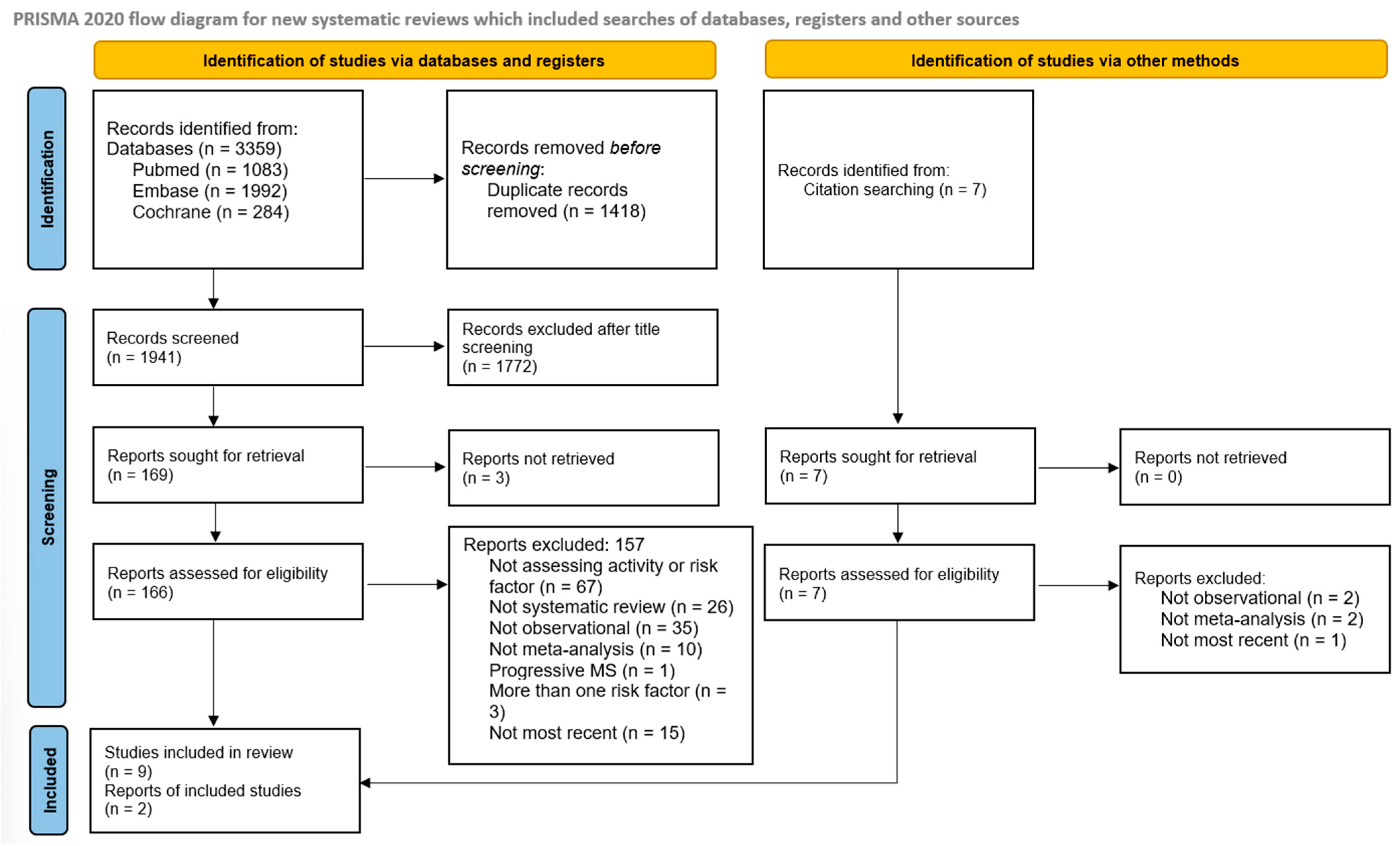

Database searching identified 3359 articles (1992 in Embase, 1083 in PubMed, and 284 in Cochrane), and an additional 7 articles were identified through other citation sources. After removing duplicates and screening titles and abstracts, 176 articles remained for full-text review (Figure 1). Ultimately, 11 systematic reviews were included and are summarized in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of included studies.

Table 1.

Characteristics and bias assessment of the included meta-analyses.

All 11 meta-analyses reported the number of primary studies included. One article (particulate matter) [21] did not specify how many patients and controls were included in the relapse risk analysis. The most commonly reported effect size was the risk ratio (RR), used in seven studies, followed by odds ratio (OR), standardized mean difference (SMD), and Cohen’s d. Most studies calculated random-effect summary effect size, but this information was not described in one article (vaccination) [20]. The p-value was not reported in four studies. Individual data from primary studies were available in seven meta-analyses, allowing us to identify the largest study and its corresponding effect size. Heterogeneity was assessed in 10 studies: nine used the I2 statistic, and one used Cochran’s Q test. Publication bias was identified in four studies. The Egger test p-value was available in three of them: 0.6 in breastfeeding meta-analysis, 0.4 in COVID meta-analysis, and 0.006 in particulate matter. A funnel plot was presented in one study (pregnancy), with no evidence of significant bias.

Maternity-related issues were extensively studied. We found seven meta-analyses evaluating relapse risk during pregnancy, and included the most recent one [12]. Pregnancy was considered a protective factor [SMD = −0.5 (95% CI: −0.67 to −0.38), p < 0.001]. Breastfeeding was assessed in two meta-analyses, and we included the most recent [11]. In this study, breastfeeding was consistently associated with a decreased risk of relapse [OR = 0.63 (95% CI: 0.45 to 0.88), p = 0.006], and the association appeared stronger in studies evaluating exclusive breastfeeding. The postpartum period was evaluated in only one meta-analysis [18], which demonstrated a consistently higher risk of relapses in the first months after delivery, particularly within the first three months [RR = 1.87 (95% CI: 1.4 to 2.5), p < 0.0001], and a reduced risk in the 10–12 months following delivery [RR = 0.81 (95% CI: 0.67 to 0.98), p = 0.03].

Two meta-analyses evaluated the association between menopause and relapse risk, and we included the most recent one [13], which found menopause to be a protective factor [SMD = −0.52 (95% CI: −0.88 to −0.15)].

A large number of meta-analyses investigated vitamin D levels in relation to relapse risk. However, most assessed the effects of vitamin D supplementation, and only one meta-analysis included exclusively observational data [15]. This study reported a 10% reduction in relapse risk per 25 nmol/L increase in serum 25(OH)D levels [RR = 0.90 (95% CI: 0.83 to 0.99)]. However, a categorical analysis comparing levels above 50 nmol/L showed a non-significant protective association [RR = 0.47 (95% CI: 0.19 to 1.17)].

Seasonality was also studied. One systematic review with meta-analysis found autumn to be a protective factor against relapse [RR = 0.97 (95% CI: 0.95 to 0.98)], with no significant increase or decrease in relapse risk associated with other seasons [14].

Stress was evaluated in several meta-analyses. The most recent one identified war-related stressors, such as missile attacks, as potential triggers for increased relapse risk, although findings were inconsistent [16]. Two larger studies could be meta-analyzed and indicated a threefold increase in relapse risk associated with missile attacks during wartime [HR = 3.0 (95% CI: 1.56 to 5.81)]. However, this contrasted with a smaller study of 32 patients, which reported a reduction in relapse risk during the war. An additional earlier meta-analysis [17] also evaluated stress in a more general manner and demonstrated a moderate effect size for stressful life events as a risk factor for MS relapse [d = 0.53; 95% CI: 0.40 to 0.65].

Only one meta-analysis evaluated the association between vaccination and relapse risk in MS [20]. It included five studies assessing relapse risk following influenza vaccination and found no statistically significant association [RR = 1.24 (95% CI: 0.89 to 1.72)]. No meta-analyses were found evaluating the risk of relapse following vaccination with BCG, chickenpox, diphtheria, DPT (diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus), hepatitis A, hepatitis B, measles, MMR (measles, mumps, rubella), mumps, pertussis, pneumococcal, polio, rabies, rubella, tetanus, typhoid fever, or yellow fever.

Regarding viral infections, we found only one meta-analysis assessing COVID-19 and relapse risk in MS. It found no significant association between acute COVID-19 infection and relapse occurrence [19]. Meta-regression analysis revealed no significant effects of potential confounders, including sample size, sex ratio, age, disease duration, vaccination status, infection severity, overall DMT use, or specific use of anti-CD20 therapies [19].

Air pollution was assessed in three meta-analyses; we included the most recent one [21], which analyzed the association between exposure to particulate matter and MS risk. However, only a limited number of studies specifically addressed relapse risk, and no statistically significant association was observed.

Other factors analyzed, but lacking adequate observational meta-analyses, included dietary habits, physical activity, smoking, comorbidities, serum homocysteine, vitamin B12, folate levels, contraceptive use and assisted reproductive techniques. Meta-analyses on hormone replacement therapy were excluded due to their interventional design.

Table 2 summarizes the certainty-of-evidence assessment according to selected GRADE components. Only one study (on breastfeeding) was classified as having high certainty. Four studies were classified as moderate certainty, and six studies were rated as having low certainty of evidence, primarily due to small sample sizes.

Table 2.

Summary of the certainty of evidence from the included studies.

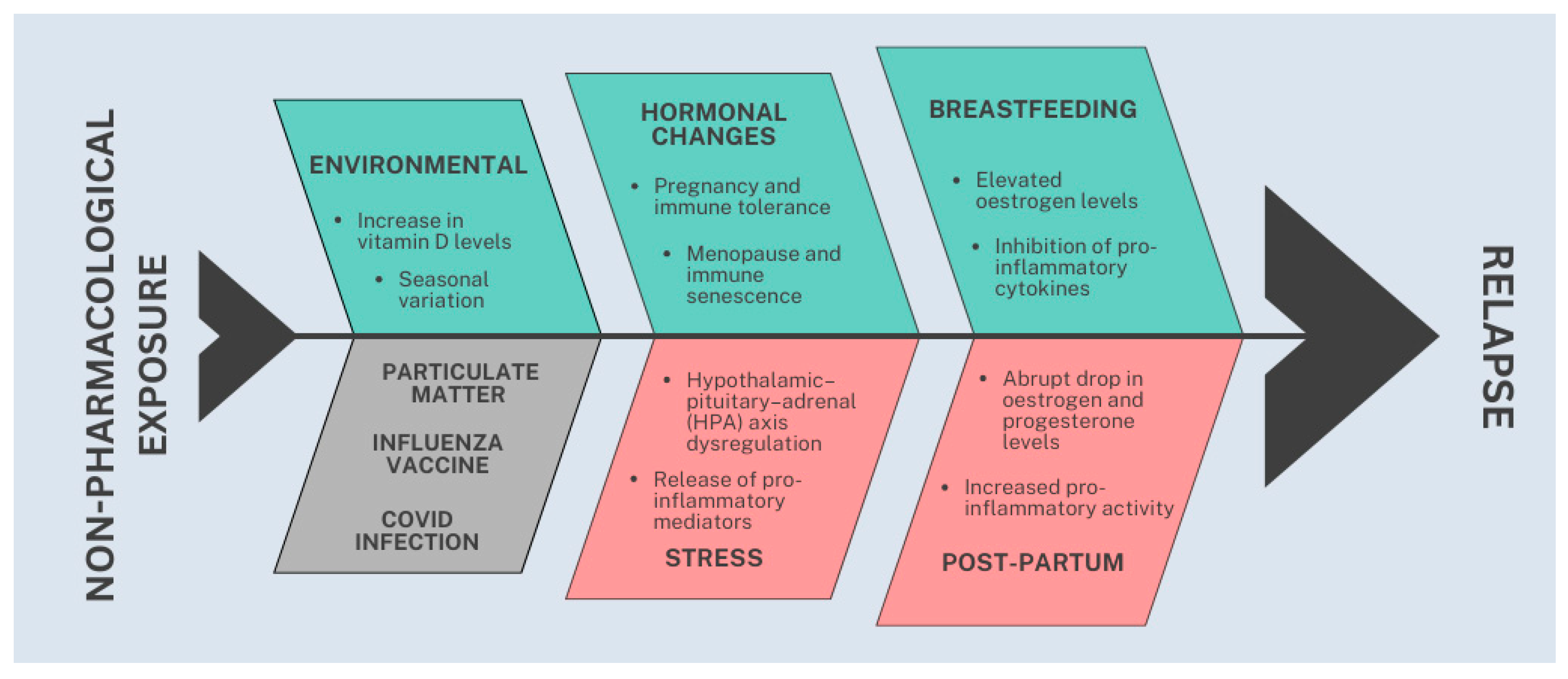

In summary, the identified protective factors were: breastfeeding [RR = 0.63; high certainty], pregnancy [SMD = −0.52; moderate certainty], menopause [SMD = −0.50; low certainty], autumn months [RR = 0.97; moderate certainty], and increasing vitamin D levels [RR = 0.90; low certainty]). The identified risk factors were: early postpartum period [RR = 1.87; moderate certainty], and stress, particularly war-related stress [RR = 3.0; low certainty]. The following factors were not significantly associated with relapse risk: Influenza vaccination (low certainty). COVID-19 infection (low certainty), exposure to particulate matter (low certainty) and vitamin D levels above 50 nmol/L (low certainty). Figure 2 illustrates the pathophysiological model underlying our study.

Figure 2.

Graphic illustration summarizing protective (green, upper section), risk (red, lower and right sections), and neutral (gray, lower and left section) factors associated with relapse risk in MS.

4. Discussion

We found high-certainty evidence supporting breastfeeding as a protective factor against MS relapses. Pregnancy and the autumn season were associated with moderate-certainty evidence for a reduced relapse risk, whereas the postpartum period and stress were identified as risk factors. Menopause showed low-certainty evidence as a protective factor. Additionally, a neutral effect was observed (also with low certainty) for COVID-19 infection, vaccination, vitamin D levels above 50 nmol/L, and exposure to particulate matter.

Breastfeeding has been consistently associated with a reduced risk of relapse [11]. Moreover, exclusive breastfeeding for at least two months appears to be linked to a significantly lower relapse risk compared with women who did not breastfeed exclusively [22]. The immunomodulatory effects of postpartum hormonal changes during exclusive breastfeeding likely play a central role in relapse prevention. These effects include suppression of the pulsatile release of gonadotropin-releasing hormone and luteinizing hormone, which is associated with inhibition of ovarian follicle growth [23]. This association is further supported by previous findings showing a return of relapses following the introduction of supplemental feeding and the resumption of menses in women who had breastfed exclusively for approximately six months [22]. Neurologists should encourage exclusive breastfeeding in women with MS and adjust disease-modifying therapy accordingly.

Fluctuations in sex hormone levels across the distinct physiological stages of the female reproductive lifespan (menarche, puberty, pregnancy, postpartum, and menopause) modulate both susceptibility to multiple sclerosis and its subsequent clinical course [24]. Elevated estrogen levels exert a protective, anti-inflammatory effect by inhibiting pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-1, IL-6) and NK cell activity, while promoting anti-inflammatory cytokines (IL-4, IL-10) and the differentiation of regulatory T cells (Tregs) [25].

Pregnancy has been associated with a decrease in MS relapses, a finding supported by longitudinal studies, particularly during the third trimester [26]. High levels of estriol, progesterone, and prolactin during pregnancy are associated with immune tolerance, including an increased number of regulatory T cells (Tregs) [27], which express sex-hormone receptors, leading to reduced inflammation.

Postpartum, on the other hand, is associated with a higher risk of relapse. After childbirth, the abrupt drop in estrogen and progesterone levels leads to a reversal of the immunotolerant state, resulting in increased pro-inflammatory activity [28]. A large prospective study following women with MS through pregnancy and a two-year postpartum period identified a marked increase in relapses during the first three months after delivery [29], followed by a return to relapse rates similar to those in the pre-pregnancy year. Higher disability scores and increased relapse rates during the pre-pregnancy year and pregnancy were associated with a greater risk of postpartum relapses [29].

Menopause is associated with immune senescence, and the decline in sex steroids during this period reduces hormonal modulation of the immune system [24]. Despite the loss of the neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory effects of sex steroids [24], aging of the immune system leads to decreased inflammatory activity, with lower production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and reduced T cell reactivity [30]. As the population ages and more women with MS reach menopause, understanding its impact on disease course is crucial for optimizing perimenopausal management in this group.

Environmental factors such as stress are difficult to study due to their subjective nature and heterogeneous methodologies, and we had difficulty finding a recent meta-analysis that fulfilled the inclusion criteria. Stress, defined as a disruption of homeostasis by intrinsic or extrinsic stimuli (stressors) [31], has limited evidence as a risk factor for MS relapse, as most studies are small and prone to bias [16]. Stress may contribute to relapses via neuroimmunological mechanisms, including hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis dysregulation and neuroimmune activation [32]. It triggers the release of corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) and neurotensin, activating mast cells and microglia, which release pro-inflammatory mediators, disrupt the blood–brain barrier, and facilitate autoreactive T-cell infiltration into the CNS [32,33]. Stress-induced glucocorticoid resistance may further impair HPA-mediated anti-inflammatory responses, amplifying neuroinflammation [32]. These findings support the hypothesis that severe stress can alter inflammatory systems, potentially triggering autoimmune processes and increasing relapse activity in MS [33], but new studies should be addressed to a better comprehension of this influence.

Seasonal variation is another factor demonstrated to be associated with relapse risk, which is lower during autumn [14]. The included study showed a very small protective effect during the autumn months, with statistical significance but probably not clinical relevance, corresponding to a 3% decrease in relapse risk. There are previous studies reporting seasonal and monthly fluctuations in MS relapse risk [34], although the underlying mechanisms remain uncertain. Possible contributors include differences in sun exposure, vitamin D levels, melatonin secretion, and air pollution across seasons, but these remain hypotheses rather than established causal pathways [14]. Preliminary metabolomic studies in MS patients have identified seasonal shifts in metabolic and immune profiles, with more anti-inflammatory signatures in autumn and more pro-inflammatory metabolites in winter [35]. These observations, although indirect, support the idea that seasonal fluctuations in MS activity may reflect complex interactions between environmental exposures, immune regulation, and metabolic responses [35].

We found low-certainty evidence suggesting that higher serum vitamin D levels may be associated with a reduced relapse risk, although the optimal threshold has not been established [15]. The active form of vitamin D, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D, promotes immune tolerance and reduces inflammation by modulating T, B, and innate immune cells involved in MS pathogenesis [36]. Vitamin D also limits CNS inflammation and demyelination by decreasing immune cell trafficking across the blood–brain barrier and suppressing microglial and astrocyte activation [36]. However, the clinical benefit of vitamin D supplementation remains inconsistent [37]. Randomized controlled trials have reported mixed results, although some showed fewer new MRI lesions [37], suggesting a possible benefit for subclinical disease activity. So, the clinical impact of vitamin D supplementation appears limited, except potentially in patients with levels below <30 nmol/L, where there may be some benefit [38].

We did not find a significant association between MS relapses and particulate matter exposure, possibly due to the limited number of studies [21]. While air pollution has been linked to various neurological disorders, its relationship with MS relapse is not well established in the literature. Particulate matter contains toxic compounds that, when inhaled, can enter the bloodstream, causing oxidative stress and systemic inflammation [21,39,40]. This triggers the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines (such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha, interleukin-6, and interleukin-1β), disrupts the blood–brain barrier, and promotes immune cell infiltration into the CNS [41], leading to neuroinflammation and CNS injury [21,42]. These mechanisms may explain the association between particulate matter exposure and MS incidence [21], although its effect on relapse rates remains unclear.

Viral infections and vaccinations show controversial associations with MS relapse risk. Acute COVID-19 infection has not been linked to increased relapse risk in the included meta-analysis [19]. Although systemic infections can trigger inflammatory responses, including cytokine release and T cell activation [43], recent evidence suggests that disease-modifying therapies may attenuate this effect [44], supporting a non-significant increase in relapse risk following systemic infections. Vaccines have not been associated with MS relapses in recent studies [45]. However, further research is needed to better evaluate the effects of specific vaccine subtypes [45].

The limitations of this review are inherent to umbrella analyses, which rely on the quality and consistency of the underlying systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Heterogeneity across studies—due to differences in design, populations, exposures, and outcome measures—poses challenges for data synthesis. Variability in relapse definitions, ranging from symptom duration criteria to protocol-defined exacerbations, and influenced by differences in symptom onset timing and EDSS changes, may affect effect estimates. The certainty of the evidence could not be fully assessed in some of the included meta-analyses due to incomplete reporting of relevant parameters, and this was considered a factor for downgrading the level of certainty.

Additionally, environmental factors such as stress and air pollution require standardized definitions for accurate assessment. Seasonal relapse variations may also differ by latitude, adding further complexity. Standardizing relapse criteria and environmental exposure definitions is essential to improve comparability and enhance understanding of modifiable factors in the management of people with multiple sclerosis. Additionally, some relevant potential risk factors could not be evaluated because we did not find adequate observational meta-analyses, including those on dietary habits, physical activity, smoking, and comorbidities, which is possibly related to the lack of systematic studies addressing these issues. This may also be due to limitations in the search strategy, since other databases were not included and some articles may not have been retrieved. We chose to include only observational studies with a control group to allow estimation of the effect size. However, excluding studies without a control group and excluding interventional studies may have introduced bias related to some potential non-pharmacological risk factors.

5. Conclusions

Our umbrella review underscores the need for high-quality studies to enhance the certainty of evidence regarding the impact of non-pharmacological exposures on relapse risk in MS. Our findings support encouraging breastfeeding when feasible, ensuring vigilant management of disease activity during pregnancy and the postpartum period, and integrating strategies to mitigate stress. These findings provide preliminary guidance for clinical practice but underscore the need for further rigorous research to inform comprehensive, evidence-based recommendations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: S.T. and G.D.S. Methodology: S.T. and G.D.S. Formal analysis: S.T. and G.D.S. Writing—original draft preparation: S.T., S.L.A.-P. and T.I.V.S. Writing—review and editing: S.T., S.L.A.-P., T.A. and G.D.S. Supervision: S.L.A.-P., D.C. and G.D.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available in the referenced articles.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT OpenAI (GPT-5.1) for grammar corrections. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding the content of this publication.

References

- Frohman, E.M.; Racke, M.K.; Raine, C.S. Multiple sclerosis—The plaque and its pathogenesis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006, 354, 942–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lublin, F.D.; Reingold, S.C.; Cohen, J.A.; Cutter, G.R.; Sørensen, P.S.; Thompson, A.J.; Wolinsky, J.S.; Balcer, L.J.; Banwell, B.; Barkhof, F.; et al. Defining the clinical course of multiple sclerosis: The 2013 revisions. Neurology 2014, 83, 278–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lublin, F.D.; Häring, D.A.; Ganjgahi, H.; Ocampo, A.; Hatami, F.; Čuklina, J.; Aarden, P.; Dahlke, F.; Arnold, D.L.; Wiendl, H.; et al. How patients with multiple sclerosis acquire disability. Brain 2022, 145, 3147–3161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavoille, A.; Rollot, F.; Casey, R.; Kerbrat, A.; Le Page, E.; Bigaut, K.; Mathey, G.; Michel, L.; Ciron, J.; Ruet, A.; et al. Acute Clinical Events Identified as Relapses with Stable Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Multiple Sclerosis. JAMA Neurol. 2024, 81, 814–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosalem, R.A.; Spricigo, M.G.P.; De Oliveira, M.B.; Adoni, T.; Apóstolos-Pereira, S.L.; Callegaro, D.; Silva, G.D. Delayed access and adherence are real-world challenges that compromises effectiveness of natalizumab in multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2025, 103, 106627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon-Nogueira, A.B.; De Holanda, A.C.; Rosalem, R.A.; Santillan, T.I.V.; de Oliveira, M.B.; Apóstolos-Pereira, S.L.; Adoni, T.; Callegaro, D.; Silva, G.D. Fingolimod in multiple sclerosis: Insights into drug survival and discontinuation factors. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2025, 101, 106554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, G.D.; Pipek, L.Z.; Oliveira, M.B.D.; Apóstolos-Pereira, S.L.; Adoni, T.; Lino, A.M.M.; Callegaro, D.; Castro, L.H.M. Could rituximab revolutionize multiple sclerosis treatment in Brazil? The missed opportunity for fewer relapses and lower costs. Lancet Reg. Health-Am. 2025, 49, 101171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobart, J.; Bowen, A.; Pepper, G.; Crofts, H.; Eberhard, L.; Berger, T.; Boyko, A.; Boz, C.; Butzkueven, H.; Celius, E.G.; et al. International consensus on quality standards for brain health-focused care in multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. Houndmills Basingstoke Engl. 2019, 25, 1809–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Tian, Z.; Han, F.; Liang, S.; Gao, Y.; Wu, D. Factors associated with relapses in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Medicine 2020, 99, e20885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krysko, K.M.; Rutatangwa, A.; Graves, J.; Lazar, A.; Waubant, E. Association Between Breastfeeding and Postpartum Multiple Sclerosis Relapses: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Neurol. 2020, 77, 327–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyedmirzaei, H.; Salabat, D.; KamaliZonouzi, S.; Teixeira, A.L.; Rezaei, N. Risk of MS relapse and deterioration after COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2024, 83, 105472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modrego, P.J.; Urrea, M.A.; de Cerio, L.D. The effects of pregnancy on relapse rates, disability and peripartum outcomes in women with multiple sclerosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Comp. Eff. Res. 2021, 10, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahraki, Z.; Rastkar, M.; Rastkar, E.; Mohammadifar, M.; Mohamadi, A.; Ghajarzadeh, M. Impact of menopause on relapse rate and disability level in patients with multiple sclerosis (MS): A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Neurol. 2023, 23, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotfi, F.; Mansourian, M.; Mirmoayyeb, O.; Najdaghi, S.; Shaygannejad, V.; Esmaeil, N. Association of Exposure to Particulate Matters and Multiple Sclerosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Neuroimmunomodulation 2022, 29, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert, C.; Steinberg, L.; Peper, J.; Ramien, C.; Hellwig, K.; Köpke, S.; Solari, A.; Giordano, A.; Gold, S.M.; Friede, T.; et al. Postpartum relapse risk in multiple sclerosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2023, 94, 718–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabizadeh, F.; Valizadeh, P.; Yazdani Tabrizi, M.; Moayyed, K.; Ghomashi, N.; Mirmosayyeb, O. Seasonal and monthly variation in multiple sclerosis relapses: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Neurol. Belg. 2022, 122, 1447–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Drathen, S.; Gold, S.M.; Peper, J.; Rahn, A.C.; Ramien, C.; Magyari, M.; Hansen, H.-C.; Friede, T.; Heesen, C. Stress and Multiple Sclerosis—Systematic review and meta-analysis of the association with disease onset, relapse risk and disability progression. Brain Behav. Immun. 2024, 120, 620–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohr, D.C.; Hart, S.L.; Julian, L.; Cox, D.; Pelletier, D. Association between stressful life events and exacerbation in multiple sclerosis: A meta-analysis. BMJ 2004, 328, 731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farez, M.F.; Correale, J. Immunizations and risk of multiple sclerosis: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Neurol. 2011, 258, 1197–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Lapiscina, E.H.; Mahatanan, R.; Lee, C.H.; Charoenpong, P.; Hong, J.P. Associations of serum 25(OH) vitamin D levels with clinical and radiological outcomes in multiple sclerosis, a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Neurol. Sci. 2020, 411, 116668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellwig, K.; Rockhoff, M.; Herbstritt, S.; Borisow, N.; Haghikia, A.; Elias-Hamp, B.; Menck, S.; Gold, R.; Langer-Gould, A. Exclusive Breastfeeding and the Effect on Postpartum Multiple Sclerosis Relapses. JAMA Neurol. 2015, 72, 1132–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howie, P.W.; Mcneilly, A.S. Breast-feeding and postpartum ovulation. IPPF Med. Bull. 1982, 16, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Baroncini, D.; Annovazzi, P.O.; De Rossi, N.; Mallucci, G.; Clerici, V.T.; Tonietti, S.; Mantero, V.; Ferrò, M.T.; Messina, M.J.; Barcella, V.; et al. Impact of natural menopause on multiple sclerosis: A multicentre study. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2019, 90, 1201–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maglione, A.; Rolla, S.; Mercanti, S.F.D.; Cutrupi, S.; Clerico, M. The Adaptive Immune System in Multiple Sclerosis: An Estrogen-Mediated Point of View. Cells 2019, 8, 1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Confavreux, C.; Hutchinson, M.; Hours, M.M.; Cortinovis-Tourniaire, P.; Moreau, T. Rate of pregnancy-related relapse in multiple sclerosis. Pregnancy in Multiple Sclerosis Group. N. Engl. J. Med. 1998, 339, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avila, M.; Bansal, A.; Culberson, J.; Peiris, A.N. The Role of Sex Hormones in Multiple Sclerosis. Eur. Neurol. 2018, 80, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koetzier, S.C.; Neuteboom, R.F.; Wierenga-Wolf, A.F.; Melief, M.-J.; de Mol, C.L.; van Rijswijk, A.; Dik, W.A.; Broux, B.; van der Wal, R.; Berg, S.A.A.v.D.; et al. Effector T Helper Cells Are Selectively Controlled During Pregnancy and Related to a Postpartum Relapse in Multiple Sclerosis. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 642038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vukusic, S.; Hutchinson, M.; Hours, M.; Moreau, T.; Cortinovis-Tourniaire, P.; Adeleine, P.; Confavreux, C. Pregnancy and multiple sclerosis (the PRIMS study): Clinical predictors of post-partum relapse. Brain J. Neurol. 2004, 127 Pt 6, 1353–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graves, J.S.; Krysko, K.M.; Hua, L.H.; Absinta, M.; Franklin, R.J.M.; Segal, B.M. Ageing and multiple sclerosis. Lancet Neurol. 2023, 22, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agorastos, A.; Chrousos, G.P. The neuroendocrinology of stress: The stress-related continuum of chronic disease development. Mol. Psychiatry 2022, 27, 502–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagkouni, A.; Alevizos, M.; Theoharides, T.C. Effect of stress on brain inflammation and multiple sclerosis. Autoimmun. Rev. 2013, 12, 947–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapanti, E.; Dermentzoglou, A.; Kazakou, P.; Kilindireas, K.; Mastorakos, G. The role of the stress adaptive response in multiple sclerosis. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2025, 78, 101204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, Y.; de Pedro-Cuesta, J.; Söderström, M.; Stawiarz, L.; Link, H. Seasonal patterns in optic neuritis and multiple sclerosis: A meta-analysis. J. Neurol. Sci. 2000, 181, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martynova, E.; Khaibullin, T.; Salafutdinov, I.; Markelova, M.; Laikov, A.; Lopukhov, L.; Liu, R.; Sahay, K.; Goyal, M.; Baranwal, M.; et al. Seasonal Changes in Serum Metabolites in Multiple Sclerosis Relapse. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlberg, C.; Mycko, M.P. Linking Mechanisms of Vitamin D Signaling with Multiple Sclerosis. Cells 2023, 12, 2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahler, J.V.; Solti, M.; Apóstolos-Pereira, S.L.; Adoni, T.; Silva, G.D.; Callegaro, D. Vitamin D3 as an add-on treatment for multiple sclerosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2024, 82, 105433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thouvenot, E.; Laplaud, D.; Lebrun-Frenay, C.; Derache, N.; Le Page, E.; Maillart, E.; Froment-Tilikete, C.; Castelnovo, G.; Casez, O.; Coustans, M.; et al. High-Dose Vitamin D in Clinically Isolated Syndrome Typical of Multiple Sclerosis: The D-Lay MS Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2025, 333, 1413–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esmaeil Mousavi, S.; Heydarpour, P.; Reis, J.; Amiri, M.; Sahraian, M.A. Multiple sclerosis and air pollution exposure: Mechanisms toward brain autoimmunity. Med. Hypotheses 2017, 100, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias-Pérez, R.D.; Taborda, N.A.; Gómez, D.M.; Narvaez, J.F.; Porras, J.; Hernandez, J.C. Inflammatory effects of particulate matter air pollution. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2020, 27, 42390–42404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortese, A.; Lova, L.; Comoli, P.; Volpe, E.; Villa, S.; Mallucci, G.; La Salvia, S.; Romani, A.; Franciotta, D.; Bollati, V.; et al. Air pollution as a contributor to the inflammatory activity of multiple sclerosis. J. Neuroinflamm. 2020, 17, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Block, M.L.; Calderón-Garcidueñas, L. Air pollution: Mechanisms of neuroinflammation and CNS disease. Trends Neurosci. 2009, 32, 506–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steelman, A.J. Infection as an Environmental Trigger of Multiple Sclerosis Disease Exacerbation. Front. Immunol. 2015, 6, 520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miele, G.; Cepparulo, S.; Abbadessa, G.; Lavorgna, L.; Sparaco, M.; Simeon, V.; Guizzaro, L.; Bonavita, S. Clinically Manifest Infections Do Not Increase the Relapse Risk in People with Multiple Sclerosis Treated with Disease-Modifying Therapies: A Prospective Study. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimaldi, L.; Papeix, C.; Hamon, Y.; Buchard, A.; Moride, Y.; Benichou, J.; Duchemin, T.; Abenhaim, L. Vaccines and the Risk of Hospitalization for Multiple Sclerosis Flare-Ups. JAMA Neurol. 2023, 80, 1098–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).