Recent Advances in Localized Scleroderma

Abstract

1. Introduction

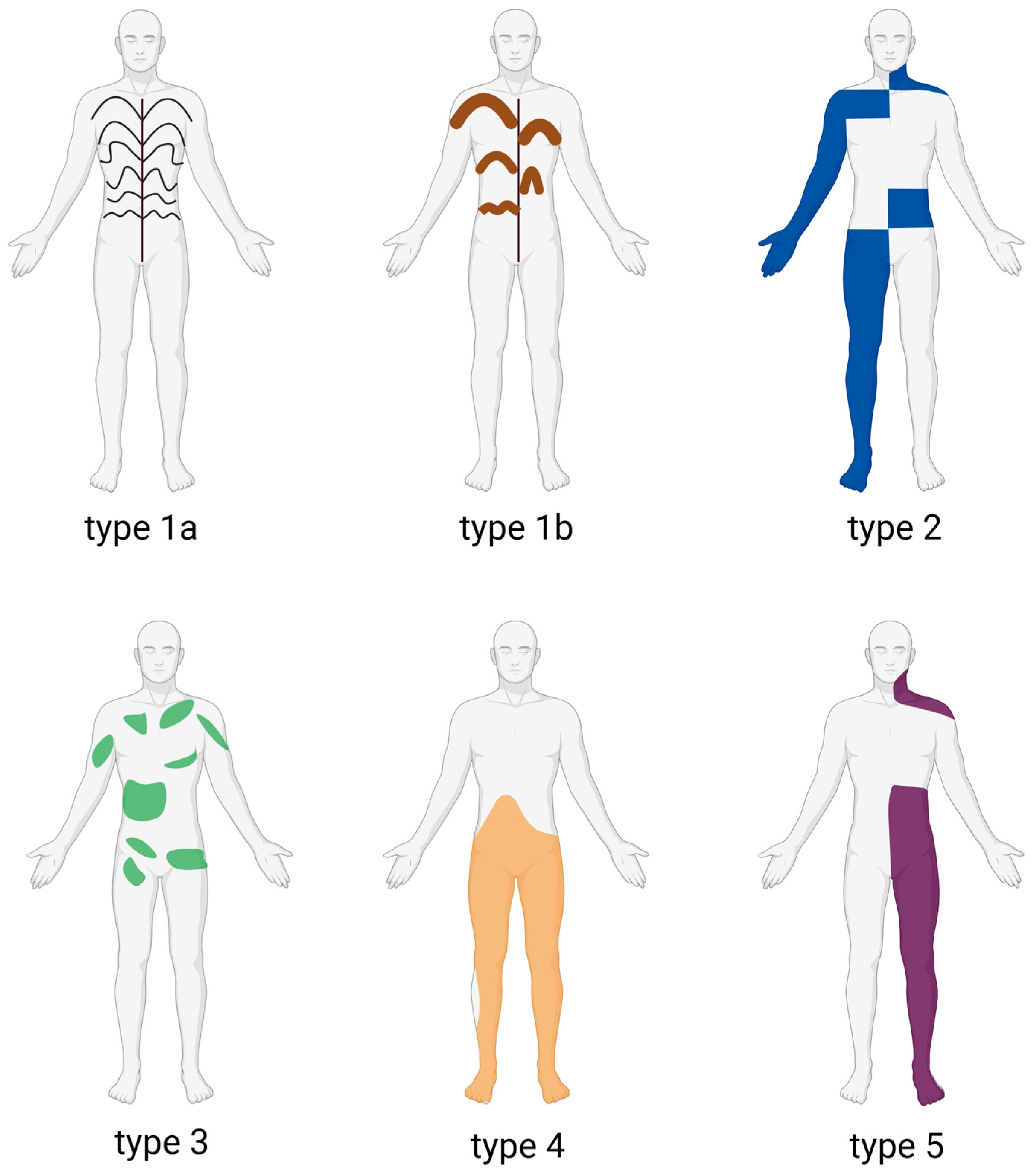

2. Subtypes of Localized Scleroderma

2.1. Main Subtypes (Padua Consensus Classification)

2.1.1. Circumscribed Morphea

2.1.2. Linear Scleroderma

2.1.3. Generalized Morphea

2.1.4. Pansclerotic Morphea

2.1.5. Mixed Morphea

2.2. Variants and Related Conditions

2.2.1. Deep Morphea (Morphea Profunda/Subcutaneous Morphea)

2.2.2. Other Clinical Variants

- Guttate morphea, characterized by multiple, small, drop-like sclerotic plaques.

- Nodular or keloidal morphea, which presents as firm nodules or keloid-like raised lesions.

- Bullous morphea, a rare form where tense bullae develop on sclerotic plaques, sometimes with histopathological features overlapping with lichen sclerosus et atrophicus (LSA).

2.2.3. Atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini

2.2.4. Associated Sclerosing Conditions

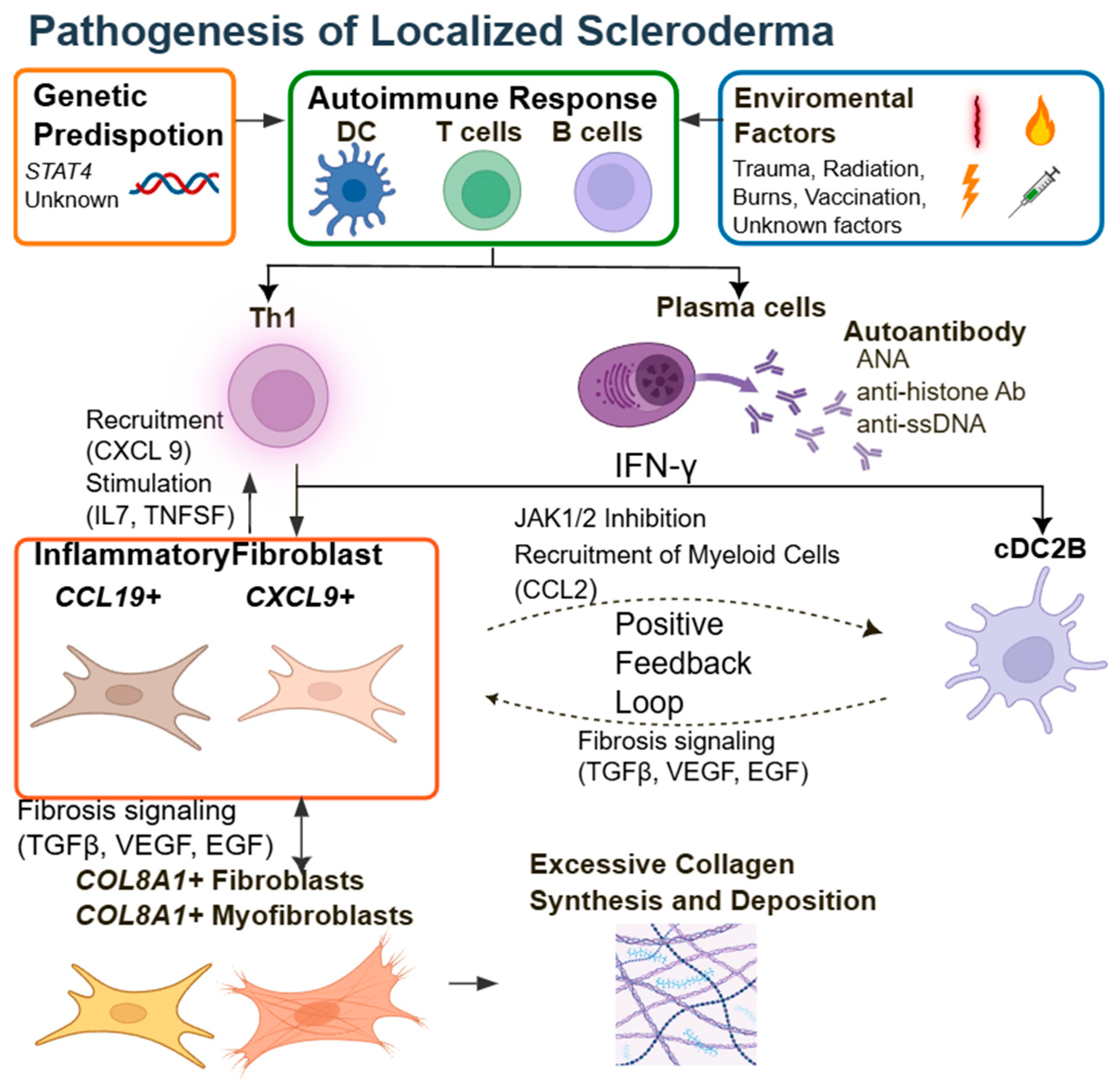

3. Pathophysiology of LSc

3.1. A Concept Based on Clinical Features: Somatic Mosaicism and Neural Crest Cells

3.2. A Concept Based on Gene Expression Patterns in Lesional Skin

3.2.1. Insights from Comparing LSc and SSc

3.2.2. Gene Expression Analysis in Lesional Skin of LSc

3.3. Immunological Findings and Biomarkers

3.4. Monogenic Forms of LSc: Linking Genetics to Targeted Therapy

4. General Clinical Course of LSc

5. Important Extracutaneous Manifestations

5.1. Musculoskeletal Complications

5.2. Neurological Complications

5.3. Ocular Complications

5.4. Growth and Developmental Complications

5.5. Association with Antiphospholipid Antibodies

6. Diagnosis and Clinical Evaluation of LSc

7. Management of LSc

7.1. Disease Assessment Tools

7.2. Standard Treatments for LSc

7.3. Novel Treatments for LSc

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Marín-Hernández, E.; Suárez-Frías, B.; Siordia Reyes, A.G. Hyperpigmented Lesions with Acquired Atrophy Following Blaschko Lines in a Patient with Diagnosed with Localized Scleroderma. Bol. Med. Hosp. Infant. Mex. 2021, 78, 621–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Li, J.; Zhang, W.; Yan, Z. Morphea: An Unusual Case Affecting Lip and Alveolar Bone. Int. J. Dermatol. 2023, 62, e623–e625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muroi, E.; Ogawa, F.; Yamaoka, T.; Sueyoshi, F.; Sato, S. Case of Localized Scleroderma Associated with Osteomyelitis. J. Dermatol. 2010, 37, 81–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asano, Y.; Fujimoto, M.; Ishikawa, O.; Sato, S.; Jinnin, M.; Takehara, K.; Hasegawa, M.; Yamamoto, T.; Ihn, H. Diagnostic Criteria, Severity Classification and Guidelines of Localized Scleroderma. J. Dermatol. 2018, 45, 755–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulian, F.; Culpo, R.; Sperotto, F.; Anton, J.; Avcin, T.; Baildam, E.M.; Boros, C.; Chaitow, J.; Constantin, T.; Kasapcopur, O.; et al. Consensus-Based Recommendations for the Management of Juvenile Localised Scleroderma. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2019, 78, 1019–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knobler, R.; Geroldinger-Simić, M.; Kreuter, A.; Hunzelmann, N.; Moinzadeh, P.; Rongioletti, F.; Denton, C.P.; Mouthon, L.; Cutolo, M.; Smith, V.; et al. Consensus Statement on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Sclerosing Diseases of the Skin, Part 1: Localized Scleroderma, Systemic Sclerosis and Overlap Syndromes. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2024, 38, 1251–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuffanelli, D.; Winkelmann, R. Systemic Scleroderma, A Clinical Study of 727 Cases. Arch. Dermatol. 1961, 84, 359–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peterson, L.S.; Nelson, A.M.; Su, W.P.D. Classification of Morphea (Localized Scleroderma). Mayo Clin. Proc. 1995, 70, 1068–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulian, F.; Woo, P.; Athreya, B.H.; Laxer, R.M.; Medsger, T.A., Jr.; Lehman, T.J.A.; Cerinic, M.M.; Martini, G.; Ravelli, A.; Russo, R.; et al. The Pediatric Rheumatology European Society/American College of Rheumatology/European League against Rheumatism Provisional Classification Criteria for Juvenile Systemic Sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007, 57, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Błaszczyk, M.; Królicki, L.; Krasu, M.; Glińska, O.; Jabłońska, S. Progressive Facial Hemiatrophy: Central Nervous System Involvement and Relationship with Scleroderma En coup de sabre. J. Rheumatol. 2003, 30, 1997–2004. [Google Scholar]

- Tollefson, M.M.; Witman, P.M. En coup de sabre Morphea and Parry-Romberg Syndrome: A Retrospective Review of 54 Patients. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2007, 56, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orozco-Covarrubias, L.; Guzmán-Meza, A.; Ridaura-Sanz, C.; Carrasco Daza, D.; Sosa-de-Martinez, C.; Ruiz-Maldonado, R. Scleroderma “en coup de sabre” and Progressive Facial Hemiatrophy. Is It Possible to Differentiate Them? J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2002, 16, 361–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, S.; Fujimoto, M.; Ihn, H.; Kikuchi, K.; Takehara, K. Clinical Characteristics Associated with Antihistone Antibodies in Patients with Localized Scleroderma. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1994, 31, 567–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherber, N.S.; Boin, F.; Hummers, L.K.; Wigley, F.M. The “Tank Top Sign”: A Unique Pattern of Skin Fibrosis Seen in Pansclerotic Morphea. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2009, 68, 1511–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, L.; Lin, J.; Furst, D.E.; Fiorentino, D. Systemic and Localized Scleroderma. Clin. Dermatol. 2006, 24, 374–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laxer, R.M.; Zulian, F. Localized Scleroderma. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 2006, 18, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kencka, D.; Blaszczyk, M.; Jabłońska, S. Atrophoderma Pasini-Pierini Is a Primary Atrophic Abortive Morphea. Dermatology 1995, 190, 203–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNiff, J.; Glusac, E.; Lazova, R.; Carroll, C. Morphea Limited to the Superficial Reticular Dermis: An Underrecognized Histologic Phenomenon. Am. J. Dermatopathol. 1999, 21, 315–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powell, J.J.; Wojnarowska, F. Lichen Sclerosus. Lancet 1999, 353, 1777–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, R. Lichen Sclerosus. Dermatol. Clin. 2010, 28, 707–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihn, H. Eosinophilic Fasciitis: From Pathophysiology to Treatment. Allergol. Int. 2019, 68, 437–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazori, D.R.; Femia, A.N.; Vleugels, R.A. Eosinophilic Fasciitis: An Updated Review on Diagnosis and Treatment. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 2017, 19, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lebeaux, D.; Sène, D. Eosinophilic Fasciitis (Shulman Disease). Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 2012, 26, 449–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobe, H.; Ahn, C.; Arnett, F.C.; Reveille, J.D. Major Histocompatibility Complex Class I and Class II Alleles May Confer Susceptibility to or Protection against Morphea: Findings from the Morphea in Adults and Children Cohort: Association of MHC Class I and Class II Alleles with Morphea. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014, 66, 3170–3177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Happle, R. Mosaicism in Human Skin. Understanding the Patterns and Mechanisms. Arch. Dermatol. 1993, 129, 1460–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miura, S.; Someya, M.; Toyama, S.; Kawai, T.; Yamashita, T.; Shishido, N.; Asano, A. Case of Scleroderma En coup de sabre with Ipsilateral Hearing Loss and Aphakia. Eur. J. Dermatol. 2019, 29, 423–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lauesen, S.R.; Daugaard-Jensen, J.; Lauridsen, E.F.; Kjær, I. Localised Scleroderma En coup de sabre Affecting the Skin, Dentition and Bone Tissue within Craniofacial Neural Crest Fields. Clinical and Radiographic Study of Six Patients. Eur. Arch. Paediatr. Dent. 2019, 20, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pain, C.E.; Torok, K.S. Challenges and Complications in Juvenile Localized Scleroderma: A Practical Approach. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 2024, 38, 101987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milano, A.; Pendergrass, S.A.; Sargent, J.L.; George, L.K.; McCalmont, T.H.; Connolly, M.K.; Whitfield, M.L. Molecular Subsets in the Gene Expression Signatures of Scleroderma Skin. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e2696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franks, J.M.; Martyanov, V.; Cai, G.; Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; Wood, T.A.; Whitfield, M.L. A Machine Learning Classifier for Assigning Individual Patients with Systemic Sclerosis to Intrinsic Molecular Subsets. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019, 71, 1701–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, D.; Spino, C.; Johnson, S.; Chung, L.; Whitfield, M.L.; Denton, C.P.; Berrocal, V.; Franks, J.; Mehta, B.; Molitor, J.; et al. Abatacept in Early Diffuse Cutaneous Systemic Sclerosis: Results of a Phase II Investigator-Initiated, Multicenter, Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020, 72, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinchcliff, M.; Huang, C.-C.; Wood, T.A.; Matthew Mahoney, J.; Martyanov, V.; Bhattacharyya, S.; Tamaki, Z.; Lee, J.; Carns, M.; Podlusky, S.; et al. Molecular Signatures in Skin Associated with Clinical Improvement during Mycophenolate Treatment in Systemic Sclerosis. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2013, 133, 1979–1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martyanov, V.; Kim, G.-H.J.; Hayes, W.; Du, S.; Ganguly, B.J.; Sy, O.; Lee, S.K.; Bogatkevich, G.S.; Schieven, G.L.; Schiopu, E.; et al. Novel Lung Imaging Biomarkers and Skin Gene Expression Subsetting in Dasatinib Treatment of Systemic Sclerosis-Associated Interstitial Lung Disease. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0187580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franks, J.M.; Martyanov, V.; Wang, Y.; Wood, T.A.; Pinckney, A.; Crofford, L.J.; Whitfield, M. Machine Learning Predicts Stem Cell Transplant Response in Severe Scleroderma. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2020, 79, 1608–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torok, K.S.; Li, S.C.; Jacobe, H.M.; Taber, S.F.; Stevens, A.M.; Zulian, F.; Lu, T.T. Immunopathogenesis of Pediatric Localized Scleroderma. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, J.C.; Rainwater, Y.B.; Malviya, N.; Cyrus, N.; Auer-Hackenberg, L.; Hynan, L.S.; Jacobe, H. Transcriptional and Cytokine Profiles Identify CXCL9 as a Biomarker of Disease Activity in Morphea. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2017, 137, 1663–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirizio, E.; Liu, C.; Yan, Q.; Waltermire, J.; Mandel, R.; Schollaert, K.L.; Konnikova, L.; Wang, X.; Chen, W.; Torok, K.S. Genetic Signatures from RNA Sequencing of Pediatric Localized Scleroderma Skin. Front. Pediatr. 2021, 9, 669116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.R.; Charos, A.; Damsky, W.; Heald, P.; Girardi, M.; King, B.A. Treatment of Generalized Deep Morphea and Eosinophilic Fasciitis with the Janus Kinase Inhibitor Tofacitinib. JAAD Case Rep. 2018, 4, 443–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheinberg, M.; Sabbagh, C.; Ferreira, S.; Michalany, N. Full Histological and Clinical Regression of Morphea with Tofacitinib. Clin. Rheumatol. 2020, 39, 2827–2828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, G.; Sanyal, A.; Mirizio, E.; Hutchins, T.; Tabib, T.; Lafyatis, R.; Jacobe, H.; Torok, K.S. Single-Cell Transcriptome Analysis Identifies Subclusters with Inflammatory Fibroblast Responses in Localized Scleroderma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, E.; Ma, F.; Wasikowski, R.; Billi, A.C.; Gharaee-Kermani, M.; Fox, J.; Dobry, C.; Victory, A.; Sarkar, M.K.; Xing, X.; et al. Pansclerotic Morphea Is Characterized by IFN-γ Responses Priming Dendritic Cell Fibroblast Crosstalk to Promote Fibrosis. JCI Insight 2023, 8, e171307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saracino, A.M.; Denton, C.P.; Orteu, C.H. The Molecular Pathogenesis of Morphoea: From Genetics to Future Treatment Targets. Br. J. Dermatol. 2017, 177, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papara, C.; De Luca, D.A.; Bieber, K.; Vorobyev, A.; Ludwig, R.J. Morphea: The 2023 Update. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1108623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falanga, V.; Medsger, T.; Reichlin, M. Antinuclear and Anti-Single-Stranded DNA Antibodies in Morphea and Generalized Morphea. Arch. Dermatol. 1987, 123, 350–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertens, J.S.; de Jong, E.M.G.J.; van den Hoogen, L.L.; Wienke, J.; Thurlings, R.M.; Seyger, M.M.B.; Hoppenreijs, E.P.A.H.; Wijngaarde, C.A.; van Vlijmen-Willems, I.M.J.J.; van den Bogaard, E.; et al. The Identification of CCL18 as Biomarker of Disease Activity in Localized Scleroderma. J. Autoimmun. 2019, 101, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snarskaya, E.S.; Vasileva, K.D. Localized Scleroderma: Actual Insights and New Biomarkers. Int. J. Dermatol. 2022, 61, 667–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghdassarian, H.; Blackstone, S.A.; Clay, O.S.; Philips, R.; Matthiasardottir, B.; Nehrebecky, M.; Hua, V.K.; McVicar, R.; Liu, Y.; Tucker, S.M.; et al. Variant STAT4 and Response to Ruxolitinib in an Autoinflammatory Syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 2241–2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamaguchi, Y.; Ueda-Hayakawa, I.; Kaneko, U.; Shimizu, M.; Miyamae, T.; Ishikawa, H.; Ae, R.; Nakamura, Y.; Asano, Y.; Fujimoto, M.; et al. Nationwide Epidemiological and Clinical Survey of Juvenile-Onset Morphea in Japan. J. Dermatol. 2025, 52, 860–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazal, S.; Muntyanu, A.; Aw, K.; Kaouache, M.; Khoury, L.; Piram, M.; McCuaig, C.; Chédeville, G.; Rahme, E.; Osman, M.; et al. Incidence, Prevalence, and Mortality of Localized Scleroderma in Quebec, Canada: A Population-Based Study. Lancet Reg. Health Am. 2025, 44, 101044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piram, M.; McCuaig, C.C.; Saint-Cyr, C.; Marcoux, D.; Hatami, A.; Haddad, E.; Powell, J. Short-and Long-term Outcome of Linear Morphoea in Children. Br. J. Dermatol. 2013, 169, 1265–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saxton-Daniels, S.; Jacobe, H. An Evaluation of Long-Term Outcomes in Adults with Pediatric-Onset Morphea. Arch. Dermatol. 2010, 146, 1044–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christen-Zaech, S.; Hakim, M.D.; Afsar, F.S.; Paller, A.S. Pediatric Morphea (Localized Scleroderma): Review of 136 Patients. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2008, 59, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liguoro, I.; Simonini, G.; Martini, G. The Burden of Extracutaneous Manifestations in Juvenile Localized Scleroderma: A Literature Review. Autoimmun. Rev. 2025, 24, 103812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.C.; Higgins, G.C.; Chen, M.; Torok, K.S.; Rabinovich, C.E.; Stewart, K.; Laxer, R.M.; Pope, E.; Haines, K.A.; Punaro, M.; et al. Extracutaneous Involvement Is Common and Associated with Prolonged Disease Activity and Greater Impact in Juvenile Localized Scleroderma. Rheumatology 2021, 60, 5724–5733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulian, F.; Vallongo, C.; Woo, P.; Russo, R.; Ruperto, N.; Harper, J.; Espada, G.; Corona, F.; Mukamel, M.; Vesely, R.; et al. Localized Scleroderma in Childhood Is Not Just a Skin Disease. Arthritis Rheum. 2005, 52, 2873–2881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ardalan, K.; Zigler, C.K.; Torok, K.S. Predictors of Longitudinal Quality of Life in Juvenile Localized Scleroderma. Arthritis Care Res. 2017, 69, 1082–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.C.; Torok, K.S.; Rabinovich, C.E.; Dedeoglu, F.; Becker, M.L.; Ferguson, P.J.; Hong, S.D.; Ibarra, M.F.; Stewart, K.; Pope, E.; et al. Initial Results from a Pilot Comparative Effectiveness Study of 3 Methotrexate-Based Consensus Treatment Plans for Juvenile Localized Scleroderma. J. Rheumatol. 2020, 47, 1242–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, E.Y.; Li, S.C.; Torok, K.S.; Virkud, Y.V.; Fuhlbrigge, R.C.; Rabinovich, C.E.; Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance (CARRA) Legacy Registry Investigators. Baseline Description of the Juvenile Localized Scleroderma Subgroup from the Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance Legacy Registry. ACR Open Rheumatol. 2019, 1, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zannin, M.E.; Martini, G.; Athreya, B.H.; Russo, R.; Higgins, G.; Vittadello, F.; Alpigiani, M.G.; Alessio, M.; Paradisi, M.; Woo, P.; et al. Ocular Involvement in Children with Localised Scleroderma: A Multi-Centre Study. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2007, 91, 1311–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takehara, K.; Sato, S. Localized Scleroderma Is an Autoimmune Disorder. Rheumatology 2005, 44, 274–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lis-Święty, A.; Brzezińska-Wcisło, L.; Arasiewicz, H.; Bergler-Czop, B. Antiphospholipid Antibodies in Localized Scleroderma: The Potential Role of Screening Tests for the Detection of Antiphospholipid Syndrome. Postepy Dermatol. Alergol. 2014, 31, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sator, P.-G.; Radakovic, S.; Schulmeister, K.; Hönigsmann, H.; Tanew, A. Medium-Dose Is More Effective than Low-Dose Ultraviolet A1 Phototherapy for Localized Scleroderma as Shown by 20-MHz Ultrasound Assessment. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2009, 60, 786–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorolay, V.V.; Fisicaro, R.; Tsui, B.; Tran, N.-A.; Eltawil, Y.; Glastonbury, C.; Wu, X.C. Neuroimaging and Clinical Features of Parry-Romberg Syndrome and Linear Morphea En-Coup-de-Sabre in a Large Case Series. Acad. Radiol. 2025, 32, 4154–4163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kister, I.; Inglese, M.; Laxer, R.M.; Herbert, J. Neurologic Manifestations of Localized Scleroderma: A Case Report and Literature Review. Neurology 2008, 71, 1538–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamaguchi, Y. Drug-Induced Scleroderma-like Lesion. Allergol. Int. 2022, 71, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjarks, B.J.; Kerkvliet, A.M.; Jassim, A.D.; Bleeker, J.S. Scleroderma-like Skin Changes Induced by Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy. J. Cutan. Pathol. 2018, 45, 615–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, M.; Nonomura, Y.; Kaku, Y.; Nakabo, S.; Endo, Y.; Otsuka, A.; Kabashima, K. Scleroderma-like Syndrome Associated with Nivolumab Treatment in Malignant Melanoma. J. Dermatol. 2019, 46, e43–e44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyama, S.; Sato, S.; Asano, Y. Localized Scleroderma Histologically Characterized by Liquefaction Degeneration and Upper Dermis Fibrosis: A Possible Association with Chemotherapy. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2020, 45, 632–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattozzi, C.; Richetta, A.G.; Cantisani, C.; Giancristoforo, S.; D’Epiro, S.; Gonzalez Serva, A.; Viola, F.; Cucchiara, S.; Calvieri, S. Morphea, an Unusual Side Effect of Anti-TNF-Alpha Treatment. Eur. J. Dermatol. 2010, 20, 400–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venetsanopoulou, A.I.; Mavridou, K.; Pelechas, E.; Voulgari, P.V.; Drosos, A.A. Development of Morphea Following Treatment with an ADA Biosimilar: A Case Report. Curr. Rheumatol. Rev. 2024, 20, 451–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arkachaisri, T.; Vilaiyuk, S.; Torok, K.S.; Medsger, T.A., Jr. Development and Initial Validation of the Localized Scleroderma Skin Damage Index and Physician Global Assessment of Disease Damage: A Proof-of-Concept Study. Rheumatology 2010, 49, 373–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaishree, S. Hyaluronic Acid Filler Injection for Localized Scleroderma-Case Report and Review of Literature on Filler Injections for Localized Scleroderma. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2022, 15, 1627–1637. [Google Scholar]

- Magro, C.M.; Halteh, P.; Olson, L.C.; Kister, I.; Shapiro, L. Linear Scleroderma “En coup de sabre” with Extensive Brain Involvement-Clinicopathologic Correlations and Response to Anti-Interleukin-6 Therapy. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2019, 14, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Nocton, J.; Chiu, Y. A Case of Pansclerotic Morphea Treated With Tocilizumab. JAMA Dermatol. 2019, 155, 388–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osminina, M.; Geppe, N.; Afonina, E. Scleroderma “En coup de sabre” With Epilepsy and Uveitis Successfully Treated With Tocilizumab. Reumatol. Clín. Engl. Ed. 2020, 16, 356–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lythgoe, H.; Baildam, E.; Beresford, M.W.; Cleary, G.; McCann, L.J.; Pain, C.E. Tocilizumab as a Potential Therapeutic Option for Children with Severe, Refractory Juvenile Localized Scleroderma. Rheumatology 2018, 57, 398–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martini, G.; Campus, S.; Raffeiner, B.; Boscarol, G.; Meneghel, A.; Zulian, F. Paediatric Rheumatology Tocilizumab in Two Children with Pansclerotic Morphoea: A Hopeful Therapy for Refractory Cases? Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2017, 35, S211–S213. [Google Scholar]

- Talia, J.; Bitar, C.; Wang, Y.; Whitfield, M.L.; Khanna, D. A Case of Recalcitrant Linear Morphea Responding to Subcutaneous Abatacept. J. Scleroderma Relat. Disord. 2021, 6, 194–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.C.; Torok, K.S.; Ishaq, S.S.; Buckley, M.; Edelheit, B.; Ede, K.C.; Liu, C.; Rabinovich, C.E. Preliminary Evidence on Abatacept Safety and Efficacy in Refractory Juvenile Localized Scleroderma. Rheumatology 2021, 60, 3817–3825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalampokis, I.; Yi, B.Y.; Smidt, A.C. Abatacept in the Treatment of Localized Scleroderma: A Pediatric Case Series and Systematic Literature Review. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2020, 50, 645–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.B.; Blixt, E.K.; Drage, L.A.; El-Azhary, R.A.; Wetter, D.A. Treatment of Morphea with Hydroxychloroquine: A Retrospective Review of 84 Patients at Mayo Clinic, 1996–2013. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2019, 80, 1658–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strong, A.L.; Rubin, J.P.; Kozlow, J.H.; Cederna, P.S. Fat Grafting for the Treatment of Scleroderma. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2019, 144, 1498–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmero, M.L.H.; Uziel, Y.; Laxer, R.M.; Forrest, C.R.; Pope, E. En coup de sabre Scleroderma and Parry-Romberg Syndrome in Adolescents: Surgical Options and Patient-Related Outcomes. J. Rheumatol. 2010, 37, 2174–2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, B.; Wang, X.; Long, X.; Zhang, M.; Huang, J.; Yu, N.; Xu, J. Supportive Use of Adipose-Derived Stem Cells in Cell-Assisted Lipotransfer for Localized Scleroderma. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2018, 141, 1395–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Long, X.; Si, L.; Chen, B.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, T.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, R.C.; Wang, X. A Pilot Study on Ex Vivo Expanded Autologous Adipose-Derived Stem Cells of Improving Fat Retention in Localized Scleroderma Patients. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2021, 10, 1148–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Li, W.; Cao, R.; Gao, D.; Zhang, Q.; Li, X.; Li, B.; Lv, L.; Li, M.; Jiang, J.; et al. Application of an IPSC-Derived Organoid Model for Localized Scleroderma Therapy. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, e2106075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Takahashi, T.; Takahashi, T.; Asano, Y. Recent Advances in Localized Scleroderma. Sclerosis 2025, 3, 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/sclerosis3040040

Takahashi T, Takahashi T, Asano Y. Recent Advances in Localized Scleroderma. Sclerosis. 2025; 3(4):40. https://doi.org/10.3390/sclerosis3040040

Chicago/Turabian StyleTakahashi, Toshiya, Takehiro Takahashi, and Yoshihide Asano. 2025. "Recent Advances in Localized Scleroderma" Sclerosis 3, no. 4: 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/sclerosis3040040

APA StyleTakahashi, T., Takahashi, T., & Asano, Y. (2025). Recent Advances in Localized Scleroderma. Sclerosis, 3(4), 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/sclerosis3040040