Abstract

Background/Objectives: Cognitive impairment is frequent in multiple sclerosis, yet routine screening is inconsistently implemented. We aimed to characterize cognitive impairment using CogEval in a Mexican cohort and to identify clinical and functional correlates. Methods: We conducted a cross-sectional study at UMAE No. 71 (Torreón, Mexico). Adults with MS (n = 81) underwent CogEval screening (classified as normal, mild, or severe). Disability, upper-limb dexterity (9-Hole Peg Test, mean of both hands), and gait speed (Timed 25-Foot Walk) were assessed. Bivariate tests and multivariable logistic regression examined associations with cognitive impairment. Results: Participants were 61.7% women; mean age was 35.7 ± 9.9 years. Median EDSS was 2.0 (IQR 1.0–4.0); 28.4% had EDSS ≥ 4. CogEval identified impairment in 49.4% (40/81), with 62.5% severe and 37.5% mild. In bivariate analyses, impairment was associated with higher EDSS (p < 0.001), slower 9-HPT (p < 0.001), and slower T25FW (p = 0.0058), but not with age, sex, or disease duration. In adjusted models, EDSS (OR 1.86, 95% CI 1.14–3.03; p = 0.012) and 9-HPT per second (OR 1.31, 95% CI 1.09–1.58; p = 0.005) independently predicted impairment, whereas T25FW and age were not significant. Discrimination was good (AUC = 0.863). Conclusions: About half of this Mexican MS cohort screened positive for cognitive impairment, particularly those with greater disability and reduced manual dexterity. CogEval appears feasible for routine screening and may help prioritize comprehensive neuropsychological assessment and rehabilitation.

1. Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic, immune-mediated disease of the central nervous system characterized by inflammatory demyelination and neuroaxonal loss that variably affects white and gray matter [1]. Beyond motor and sensory symptoms, cognitive impairment (CI) is common and clinically consequential, affecting an estimated 40–70% of people with MS across phenotypes and disease stages [2]. CI adversely impacts employment, education, adherence, and quality of life, often out of proportion to overt motor disability.

MS pathology features multifocal inflammation, demyelination, and gliosis across white and gray matter in brain and spinal cord, forming the characteristic plaques/lesions that disrupt saltatory conduction by loss of myelin sheaths. In early inflammatory phases, clinically isolated syndrome (CIS) and relapsing–remitting MS (RRMS), lesions are typically active, with prominent CD8+ T-cell and B-cell infiltration (less CD4+ than classically appreciated), activated microglia/macrophages at lesion rims, and reactive astrocytes, all sustaining local inflammation and tissue injury. In progressive phenotypes, primary progressive MS (PPMS) and secondary progressive MS (SPMS), inactive demyelinating lesions predominate, characterized by established demyelination, reduced axonal density, astrogliosis, and microglial activation with lower lymphocytic infiltration, yet chronic compartmentalized immune activity persists. Notably, tertiary lymphoid structures in the meninges (plasma cells, B/T cells, follicular dendritic cells) support sustained intrathecal inflammation and ongoing tissue damage [3]. Etiologically, MS arises from interplay of genetic/environmental factors with innate and adaptive immunity. A key event is blood–brain barrier disruption, facilitated by pro-inflammatory cytokines and matrix metalloproteinases, enabling autoreactive lymphocytes to access CNS myelin and drive demyelination and axonal injury. Within the CNS, microglia (antigen presentation, pro-inflammatory mediators) and astrocytes (context-dependent pro-/anti-inflammatory roles) amplify or modulate inflammation; when chronically activated, they contribute to sustained neuroinflammation, axonal injury, and plaque formation. Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis provides mechanistic support for an autoimmune origin and links peripheral with compartmentalized CNS immunity. This immunopathologic framework helps explain why cognitive symptoms can emerge early and progress across phenotypes, reinforcing the rationale for routine cognitive surveillance [4].

Converging MRI and neuropathology data implicate deep gray structures (notably the thalamus), hippocampus, corpus callosum, and cortical thinning, alongside diffuse injury in normal-appearing tissue. Disrupted thalamo-cortical and fronto-parietal connectivity aligns with slowed information processing and executive inefficiency; functional MRI suggests early compensatory hyperconnectivity that may wane as neural reserve is exhausted. Fluid biomarkers of axonal injury such as neurofilament light chain (NfL) may further stratify risk [5].

Across cohorts, processing speed is the most frequently affected domain, followed by episodic learning/memory, attention/working memory, and executive functions; visuospatial learning/memory is variably impaired, whereas language is relatively spared aside from mild word-finding difficulty. Reported frequencies depend on disease stage, instruments, impairment thresholds, education, and comorbid symptoms (depression, fatigue). In early MS (CIS/early RRMS), deficits in processing speed can already be detected and often expand in scope and severity with progression [6].

Despite the burden of CI, routine screening remains inconsistent due to time constraints, personnel demands, and limited access to full neuropsychological testing. Pragmatic initiatives such as the Brief International Cognitive Assessment for MS (BICAMS) have promoted standardized, short batteries anchored by the Symbol Digit Modalities Test (SDMT), but additional rapid, clinic-feasible tools are needed to embed cognitive surveillance in everyday practice and to triage patients for comprehensive assessment and rehabilitation [7].

CogEval (Cognitive Evaluation) is an iPad-based, self-administered processing speed test modeled on the SDMT. In a two-minute task, patients pair abstract symbols with numbers using a key; the app returns an immediate raw score and an age-/education-adjusted z-score based on normative data, without storing personally identifying information. The tool is free to download and designed for in-clinic use, enabling rapid screening with minimal staff time. Validation studies report strong convergence with SDMT and support use in routine MS care, with additional normative data published for diverse settings. Importantly, PST targets processing and does not assess verbal or visual learning; thus, CogEval is best viewed as a brief screen that can triage patients to comprehensive neuropsychological evaluation when indicated [8,9].

In MS clinics, disability and function are routinely measured with the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS), Nine-Hole Peg Test (9-HPT), and Timed 25-Foot Walk (T25FW), which capture complementary aspects of global disability, upper-limb dexterity/cerebello-frontal control, and ambulatory capacity, respectively. Prior work suggests that worse disability and impaired manual dexterity often co-occur with poorer cognitive performance, though the strength and independence of these relationships vary by cohort [10,11]. Importantly, Latin American populations remain under-represented; generating context-specific evidence from Mexican clinical practice is relevant for equity, external validity, and implementation.

We aimed to estimate the prevalence and severity of screening-positive cognitive impairment using CogEval in a consecutive Mexican MS cohort, and evaluate clinical and functional correlates, testing whether global disability, upper-limb dexterity, and gait speed were independently associated with impairment after adjustment for age.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

We conducted a cross-sectional observational study at the MS and Demyelinating Diseases Clinic, Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social (IMSS), UMAE with H.E. No. 71 (Torreón, Coahuila, Mexico). Data were obtained during routine clinical care and entered into standardized forms by trained clinical staff at the time of the visit.

2.2. Participants

Eligible participants were adults (≥18 years) with a neurologist-confirmed diagnosis of MS according to the 2017 McDonald criteria [12]. Exclusion criteria were: relapse or systemic corticosteroids within 30 days prior to testing; comorbid neurological disorders (e.g., stroke, traumatic brain injury) likely to confound cognitive or motor performance; and incomplete primary variables. The final analytic sample comprised 81 participants.

2.3. Data Collection: Demographics and Clinical Variables

Demographic and clinical data (age, sex, disease duration) were extracted from the electronic medical record on the same day as testing. Global disability was assessed by a neurologist experienced in EDSS scoring (range 0–10; higher = worse disability; prespecified threshold EDSS ≥ 4 for at least moderate disability). All variables were entered into a structured Microsoft Excel study database created for this project; records were de-identified and each participant was assigned a study code prior to analysis.

2.4. Cognitive Screening

CogEval is an iPad-based, self-administered Processing Speed Test (PST) modeled on the Symbol Digit Modalities Test. In a 2 min task, participants match symbols to digits using a reference key; the application yields an immediate raw score (correct matches) and an age/education-adjusted z-score based on normative data. Administration was performed in-clinic, supervised by a trained technician/nurse to ensure task understanding, and took ~3–4 min including instruction [9].

We categorized CogEval performance as normal, mild impairment (z-score between −1.0 and −1.99), or severe impairment (z-score ≤ −2.0), following published convention for brief cognitive screens. For regression analyses, we used a binary outcome (impaired = mild or severe vs. normal).

2.5. Functional Measures

Upper-limb dexterity was assessed with the 9-HPT using a standardized board. Participants completed two trials per hand. We used the mean time in seconds across the four trials, two per hand, as the primary 9-HPT metric, in line with clinical trial practice [13].

Ambulation was evaluated over a straight 25-foot course at customary pace. Participants performed two trials; we used the mean time in seconds as the T25FW outcome [11].

All functional assessments were administered and scored in accordance with Multiple Sclerosis Functional Composite (MSFC) recommendations and standardized protocols.

2.6. Primary and Secondary Outcomes

The primary outcome was cognitive impairment on CogEval (binary: impaired vs. normal). Secondary outcomes included the three-level CogEval category (normal, mild, severe) and the continuous functional metrics (9-HPT and T25FW times).

2.7. Data Analysis

Analyses were performed in IBM SPSS Statistics v27. Continuous variables are summarized as mean ± SD (approximately symmetric) or median (IQR) (skewed). Categorical variables are presented as n (%).

Normality was assessed by Shapiro–Wilk and Q–Q plots; due to skew and sample size, we used non-parametric tests for between-group comparisons.

We compared cognitively impaired vs. normal groups using Mann–Whitney U (continuous) and chi-square (or Fisher’s exact when expected counts < 5) for categorical variables. We report two-sided p values (α = 0.05) and effect sizes: rank-biserial r (continuous) and Cramér’s V or odds ratios (categorical), as appropriate.

Multivariable modeling. We fitted a binary logistic regression with CogEval impairment (yes/no) as the dependent variable. A priori candidate predictors were EDSS, 9-HPT (per 1 s increase), and T25FW (per 1 s increase), with age considered as a potential confounder (sex and disease duration were examined in bivariate analyses and retained if p < 0.20 and EPV allowed). We report adjusted odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Discrimination was quantified using the area under the ROC curve (AUC). We inspected multicollinearity via variance inflation factor (VIF < 5).

Missingness was <5% across variables; analyses were complete-case. If missingness had exceeded this threshold, we prespecified multiple imputation by chained equations as a sensitivity analysis.

2.8. Ethics

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the “Comité Local de Investigación en Salud 501 of hospital de especialidades num 71” (registry: CONBIOETICA 05 CEI 001 2018041) of the Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social, under the institutional approval code R-2024-501-134. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and applicable regulations. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to any study procedures. Clinical information was subsequently de-identified for analysis to protect confidentiality.

3. Results

3.1. Cohort Characteristics

The study sample comprised 81 participants (mean age 35.7 ± 9.9 years); 61.7% (n = 50) were women. All participants had RRMS. Overall disability was mild to moderate: 28.4% had EDSS ≥ 4. Median EDSS was 2.0 (IQR 1.0–4.0). Functional performance showed a median 9-HPT time (mean of both hands) of 25.0 s (IQR 22.3–29.7) and a median T25FW time of 11.1 s (IQR 10.0–14.0). Median disease duration was 4.0 years (IQR 3.0–8.0) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study cohort.

3.2. Prevalence and Severity of Cognitive Impairment

CogEval screening identified cognitive impairment in 49.4% (40/81) of participants; among impaired cases, 62.5% (25/40) were severe and 37.5% (15/40) mild, while 50.6% (41/81) screened cognitively normal.

3.3. Bivariate Relationships with Cognitive Status

Relative to cognitively normal peers, participants who screened impaired on CogEval showed greater neurological disability and slower motor performance. Median EDSS was 4.0 (IQR 2.0–5.5) in the impaired group versus 1.0 (IQR 0.0–2.0) in the normal group (p < 0.001), consistent with a large rank-based effect. Hand dexterity was markedly worse among impaired participants, with 9-HPT times of 29.87 s (IQR 25.21–35.71) compared with 22.96 s (IQR 20.06–24.70) in the normal group (p < 0.001), also a large difference. Ambulation was slower in the impaired group, with T25FW of 12.70 s (IQR 10.74–14.19) versus 10.50 s (IQR 9.32–11.85) in normals (p = 0.0058), indicating a moderate difference. There were no significant differences by age (p = 0.932), sex (p = 0.930), or disease duration (p = 0.611) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Bivariate comparisons by cognitive status (Normal vs. Impaired).

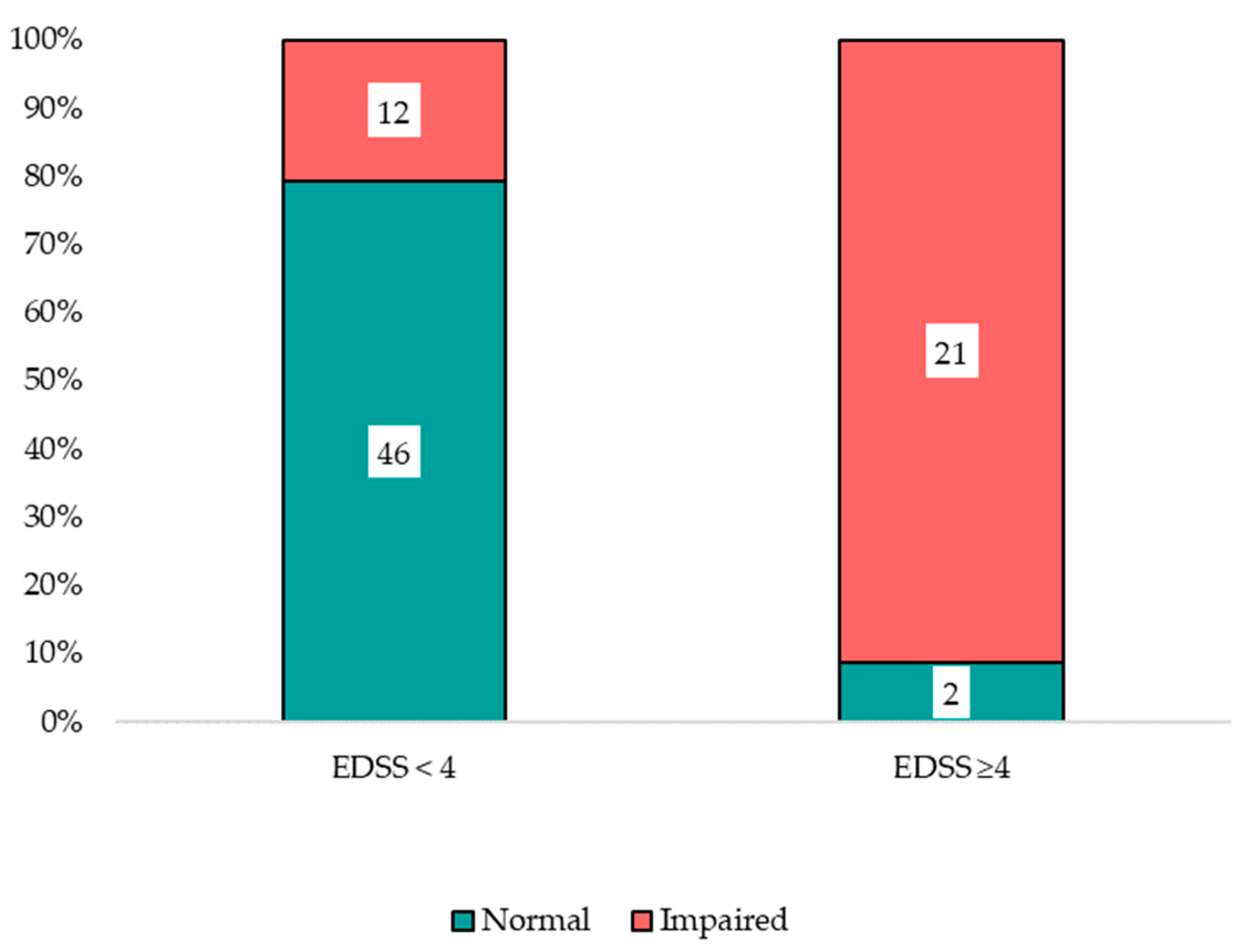

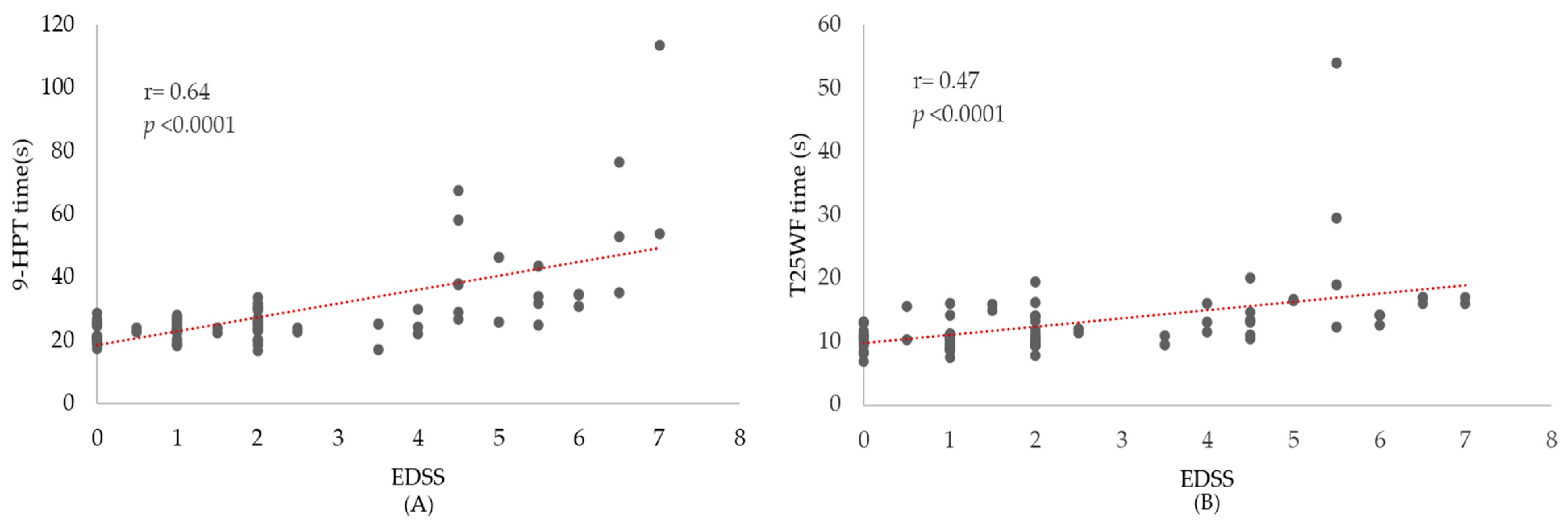

3.4. Disability Strata and Functional Performance

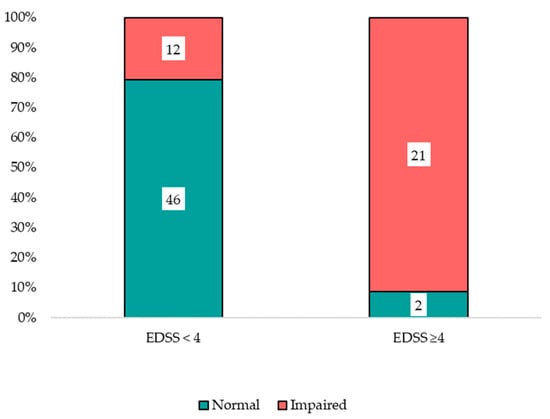

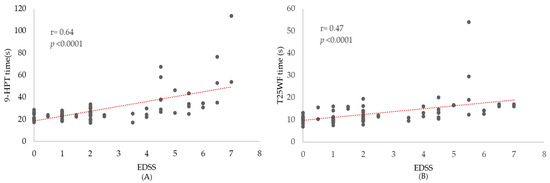

Participants with higher disability (EDSS ≥ 4) were more likely to screen impaired on CogEval and exhibited worse 9-HPT and slower T25FW performance than those with EDSS < 4, reflecting a clinically meaningful gradient across disability strata (Figure 1 and Figure 2). A similar stepwise pattern was observed across CogEval categories, with progressively worse EDSS and 9-HPT performance.

Figure 1.

Cognitive status by disability strata.

Figure 2.

Disability correlates of manual dexterity and gait speed. Scatterplots show individual participants. (A) 9-HPT time (s) vs. EDSS (B) T25FW time (s) vs. EDSS. The red dotted line indicates the linear trend; its positive slope suggests that greater disability tends to be accompanied by slower performance.

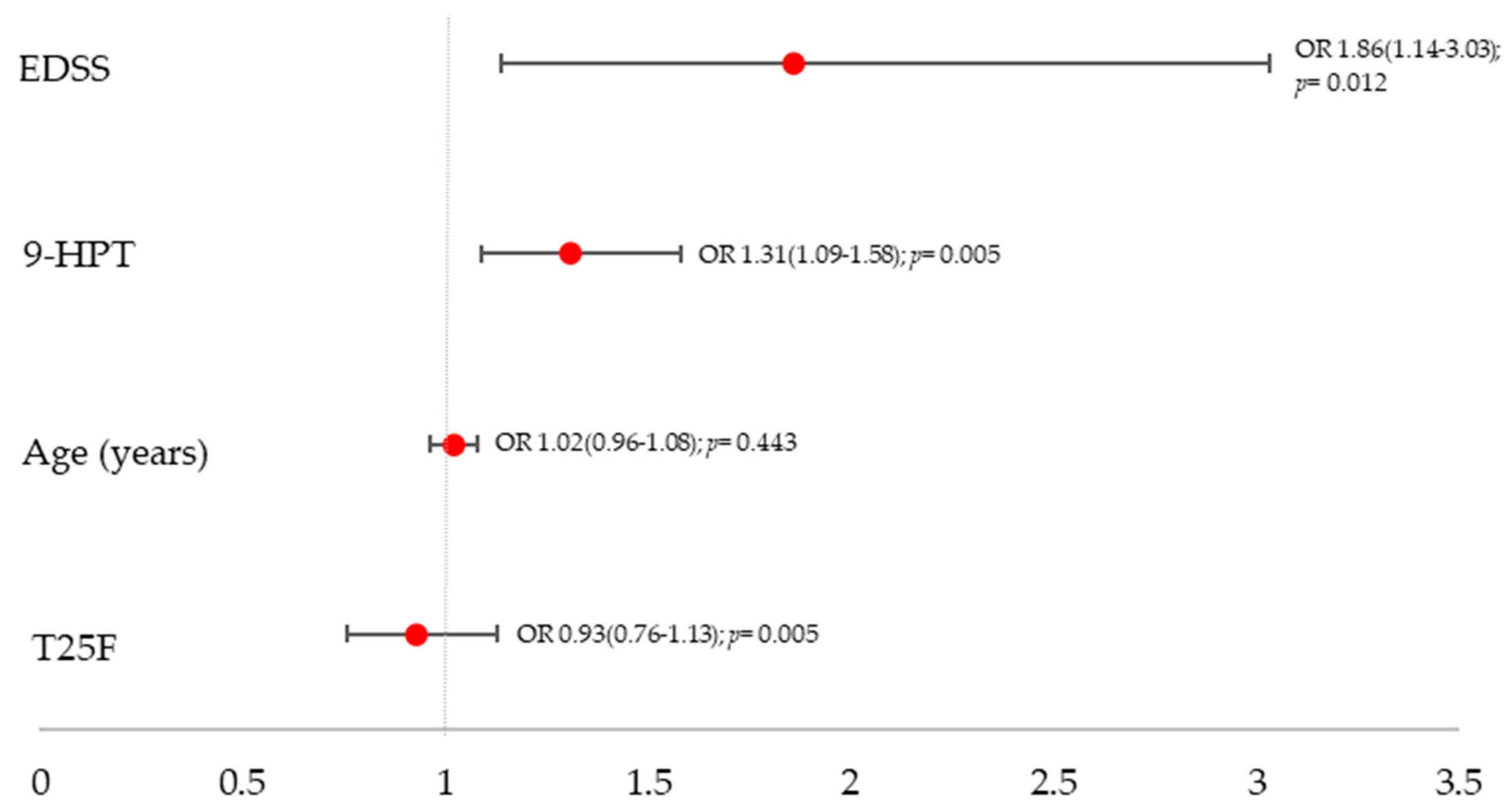

3.5. Multivariable Model

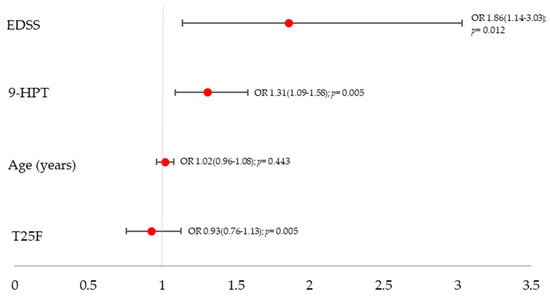

In multivariable binary logistic regression including EDSS, 9-HPT, T25FW, and age, two variables were independently associated with cognitive impairment: EDSS (OR 1.86, 95% CI 1.14–3.03; p = 0.012) and 9-HPT per 1 s increase (OR 1.31, 95% CI 1.09–1.58; p = 0.005). T25FW (OR 0.93, 95% CI 0.76–1.13; p = 0.443) and age (OR 1.02, 95% CI 0.96–1.08; p = 0.628) were not significant. Model discrimination was good (AUC = 0.863) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Adjusted odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals from a multivariable logistic regression including EDSS, 9-HPT, T25FW, and age.

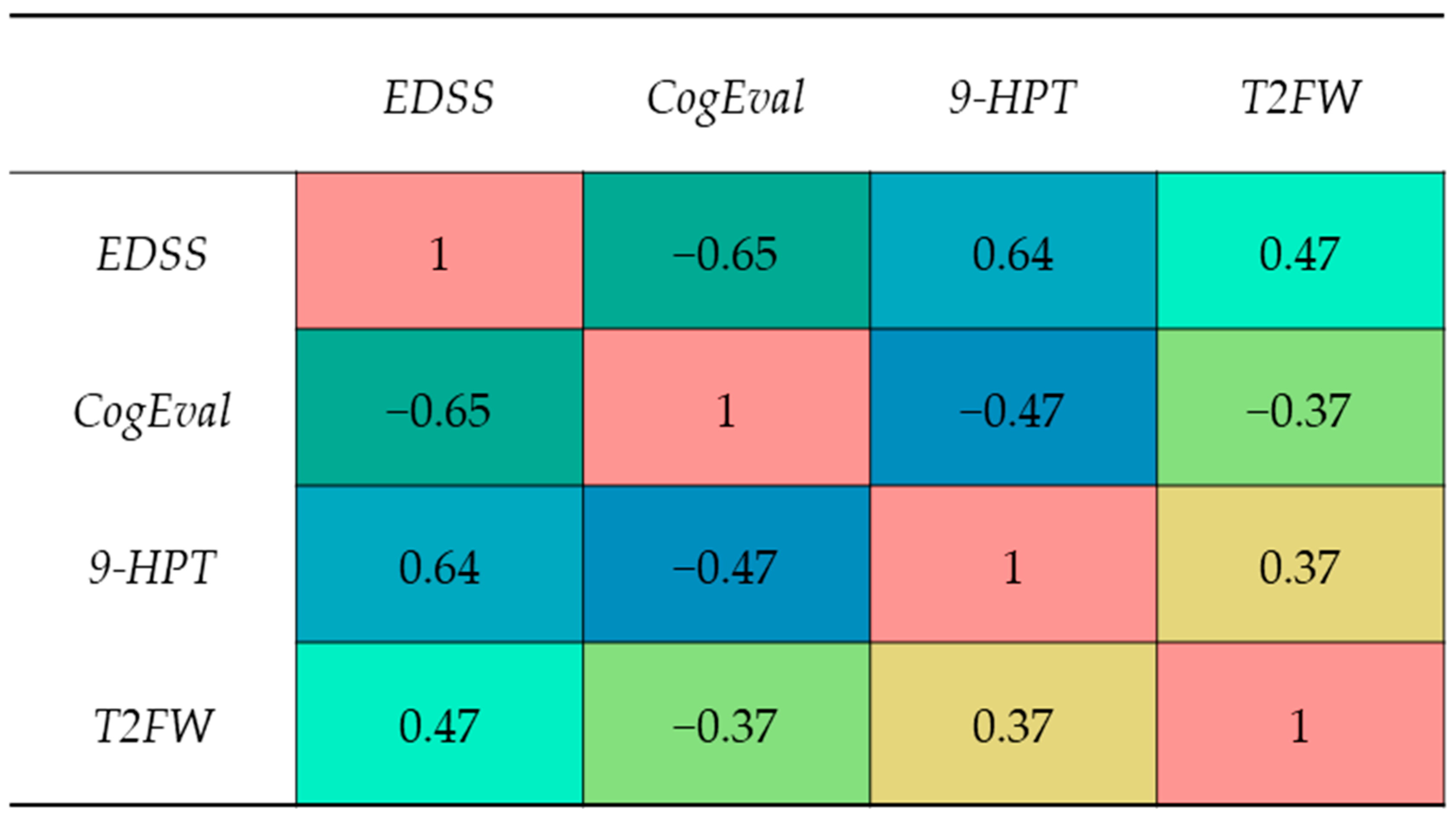

3.6. Exploratory Analyses

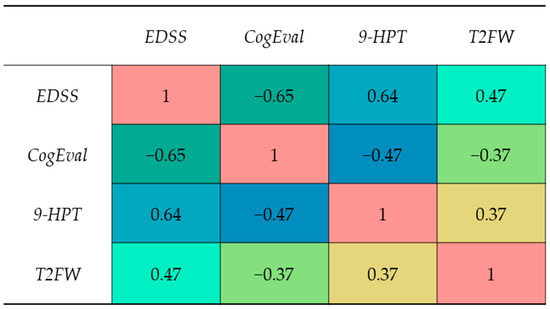

A rank-based Spearman correlation matrix (Figure 4) summarized the joint relationships among disability, motor performance, and cognition. The strongest associations were observed between EDSS and CogEval z-score (ρ = −0.65) and between EDSS and 9-HPT time (ρ = 0.64), indicating that greater disability aligns with both processing-speed inefficiency and slower upper-limb dexterity. EDSS and T25FW showed a moderate correlation (ρ = 0.47). Processing speed correlated negatively with motor measures, CogEval z with 9-HPT (ρ = −0.47) and with T25FW (ρ = −0.37), with magnitudes smaller than those involving EDSS.

Figure 4.

Spearman correlation matrix among EDSS, 9-HPT (s), T25FW (s), and CogEval z-score; cell values indicate ρ.

Scatterplots (Figure 3) were consistent with monotonic patterns without clear non-linearities. Together, these exploratory results reinforce the primary findings: CogEval tracks most closely with global disability (EDSS) and, among motor tests, with upper-limb dexterity (9-HPT), whereas gait speed (T25FW) contributes comparatively less independent information to cognitive screening in this cohort.

4. Discussion

In this single-center Mexican cohort, approximately half of patients with MS screened positive for cognitive impairment using CogEval (49.4%), with a predominance of severe cases among those impaired (62.5%). Impairment was strongly associated with higher overall disability and slower upper-limb performance, while gait speed lost significance in multivariable models. These findings reinforce those cognitive changes in MS are common and clinically meaningful, even in relatively young cohorts with mild-to-moderate disability, and that brief screening can identify patients who may benefit from comprehensive neuropsychological assessment and rehabilitation [14].

The prevalence we observed lies within the widely reported 40–70% range for cognitive impairment in MS, and the profile fits prior descriptions across disease phenotypes and stages [15]. Our multivariable results align with reports that global disability and upper-limb dexterity relate to cognitive status, likely reflecting shared neural substrates (fronto-parietal–cerebellar networks and thalamo-cortical disconnection) and diffuse gray- and white-matter pathology that underlie both cognitive and motor domains [16,17]. The robust association with the 9-HPT is consistent with its recognized sensitivity to cerebellar and fronto-parietal dysfunction and with its role in the MS Functional Composite [18]. By contrast, T25FW was significant in bivariate analysis but not after adjustment, suggesting overlap with EDSS (mobility component) and possibly lower sensitivity to cognitive–motor coupling than manual dexterity in this sample [19].

4.1. Screening Tool and Clinical Implications

Our data support the feasibility of brief cognitive screening in routine MS care. While international initiatives (e.g., BICAMS) commonly rely on the Symbol Digit Modalities Test as a rapid index of processing speed, our results indicate that CogEval, administered in minutes, can stratify cognitive risk and correlate with functional measures. In practice, patients screening positive could be prioritized for a full neuropsychological battery, counseling on vocational/academic accommodations, and targeted interventions (speed-of-processing training, external memory aids, fatigue/sleep optimization). Embedding screening alongside EDSS and MSFC components may streamline decision-making and rehabilitation referrals.

4.2. Pathophysiological Considerations

Cognitive impairment in MS arises from a mix of demyelination, axonal injury, and network disconnection particularly involving thalamic hubs and frontal–parietal circuitry, plus cortical and deep gray matter atrophy; these processes map well onto slowing of information processing and executive dysfunction [20]. Blood and CSF-based biomarkers such as neurofilament light chain (NfL) track neuroaxonal damage and are increasingly linked to cognitive outcomes; integrating such markers could refine risk stratification beyond clinical measures alone [21].

Active inflammatory lesions (gadolinium-enhancing) have been linked to transient decrements in processing-speed tasks (e.g., PASAT), supporting the concept of “cognitive relapses,” with partial recovery as inflammation subsides. Microglia, essential for experience-dependent synaptic remodeling, may contribute to pathology through excessive synaptic pruning during demyelination, degrading network connectivity and cognition [22].

4.3. MRI Assessment

Early MRI work showed that lesion burden on conventional T2-weighted scans does not fully account for cognitive impairment in MS. Advanced techniques (e.g., magnetization transfer, diffusion tensor imaging, T1 relaxometry) revealed diffuse microstructural injury in tissue that appears normal on routine MRI, and double inversion recovery improved visualization of cortical lesions, both closely linked to cognitive decline [23]. Volumetric studies consistently associate gray-matter atrophy with worse cognition, particularly in deep gray matter (notably the thalamus), mesial temporal structures, and neocortex; thalamic atrophy and altered diffusivity independently correlate with impairment. Hippocampal volume and function are also affected and represent a predilection site for demyelination [24]. Resting-state fMRI demonstrates altered functional connectivity across thalamic–hippocampal–cortical networks; hyperconnectivity may reflect early compensation that later gives way to hypoconnectivity as reserve is exhausted. Overall, combining structural and functional measures helps explain clinical heterogeneity, but MRI alone has limited individual-level prognostic power; among imaging markers, gray-matter atrophy is the most reliable indicator of cognitive risk [25].

4.4. Treatment of Cognitive Impairment

The Multiple Sclerosis Outcomes Assessment Consortium (MSOAC) initiative sought to modernize outcome measurement in phase 3 MS trials, which traditionally emphasize annualized relapse rate and EDSS-defined disability progression. First-line DMTs (e.g., interferon-β, glatiramer acetate) outperform placebo on these endpoints, and newer escalation agents (e.g., fingolimod, ocrelizumab, ozanimod) are generally more efficacious than older therapies [26]. With respect to cognition, a meta-analysis pooling 55 cohorts from 44 studies found small-to-moderate gains on SDMT or PASAT with DMT use. SDMT has only recently become a frequent tertiary/exploratory endpoint in phase 3 trials; post hoc analyses reported greater SDMT improvement with daclizumab vs. interferon-β1a, although daclizumab is no longer pursued due to safety concerns. Overall, between-therapy differences on SDMT appear statistically significant but small and are not recommended as a stand-alone factor for treatment selection [27].

There are no approved pharmacologic treatments specifically for cognitive symptoms in MS. A systematic review concluded that evidence remains insufficient; the best signal came from fampridine with SDMT as the primary outcome in a single class I study showing a transient effect, while lower-class trials were inconsistent [28]. Adequately powered, controlled trials with cognition as a primary outcome are needed to clarify drug effects.

By contrast, cognitive rehabilitation shows more robust support. Restorative, often computer-mediated training targeting processing speed and working memory yields moderate effects overall (meta-analysis of 20 RCTs; n = 982), with small-to-moderate benefits across processing speed, executive function, and memory though gains wane without booster sessions [29]. Programs such as RehaCom are the most studied in MS, with benefits evident immediately and up to two years post-treatment; training-related improvements correlate with changes in brain activation/connectivity on fMRI [30]. Preliminary data suggest that higher cognitive reserve, less white-matter disruption, and more normative functional connectivity profiles predict greater response to computerized training (e.g., BrainHQ) [31].

4.5. Strengths and Limitations

Strengths include a well-characterized clinical cohort, standardized functional testing, and prespecified multivariable modeling with discrimination estimates (AUC). Limitations include the cross-sectional design (no causal inference), single-center setting (generalizability), moderate sample size (precision for small effects), and lack of systematic adjustment for mood, fatigue, sleep, and education/linguistic factors that can influence cognitive performance. We also did not analyze MRI metrics or biomarkers in the present study, precluding structure–function correlations.

5. Conclusions

In this Mexican cohort, nearly half of patients with multiple sclerosis screened positive for cognitive impairment on CogEval (49.4%). Cognitive impairment was related to greater global disability and reduced upper-limb dexterity: EDSS and 9-HPT remained independent predictors in multivariable models, whereas T25FW and age did not. The model showed good discrimination (AUC = 0.863), supporting the clinical relevance of these associations. Taken together, these findings indicate that brief cognitive screening is feasible in routine care and can efficiently flag individuals who warrant comprehensive neuropsychological evaluation and targeted rehabilitation.

From a practical standpoint, embedding CogEval alongside standard assessments (EDSS, 9-HPT, T25FW) may streamline risk stratification, inform counseling, and guide referrals to cognitive and occupational therapy. Given that impairment was common even in a relatively young cohort with mild-to-moderate disability, systematic screening could help surface needs that are otherwise under-recognized in busy clinics.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: L.F.H.S., D.M.S.S.G., J.A.M.C. and L.E.Z.M.; methodology: L.F.H.S.; formal analysis: L.F.H.S. and L.E.Z.M.; investigation: L.F.H.S. and L.E.Z.M.; writing—original draft preparation: L.F.H.S. and L.E.Z.M.; writing—review and editing: L.F.H.S.; supervision: D.M.S.S.G. and J.A.M.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The protocol was approved by the “Comité Local de Investigación en Salud 501 del HOSPITAL DE ESPECIALIDADES NUM 71” (registry: CONBIOETICA 05 CEI 001 2018041), Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social, approval code R-2024-501-134. The study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this article are available from the corresponding author upon request. The data contain sensitive information and are not publicly available for ethical reasons.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MS | Multiple Sclerosis |

| EDSS | Expanded Disability Status Scale |

| CogEval | Cognitive Evaluation |

| 9-HPT | 9-Hole Peg Test |

| T25FW | Timed 25-Foot Walk |

| MSFC | Multiple Sclerosis Functional Composite |

| MSOAC | Multiple Sclerosis Outcomes Assessment Consortium |

| BICAMS | Brief International Cognitive Assessment for MS |

| SDMT | Symbol Digit Modalities Test |

| NfL | Neurofilament light chain |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| CSF | Cerebrospinal Fluid |

| CI | Cognitive impairment |

| CNS | Central nervous system |

| CIS | Clinically isolated syndrome |

| RRMS | Relapsing–remitting MS |

| SPMS | Secondary progressive MS |

| PPMS | Primary progressive MS |

| PST | Processing speed test |

References

- Haki, M.; Al-Biati, H.A.; Al-Tameemi, Z.S.; Ali, I.S.; Al-Hussaniy, H.A. Review of multiple sclerosis: Epidemiology, etiology, pathophysiology, and treatment. Medicine 2024, 103, e37297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLuca, J.; Chiaravalloti, N.; Sandroff, B. Treatment and management of cognitive dysfunction in patients with multiple sclerosis. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2020, 16, 319–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippi, M.; Bar-Or, A.; Piehl, F.; Preziosa, P.; Solari, A.; Vukusic, S.; Rocca, A.M. Multiple sclerosis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2018, 4, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi, N.; Razavi, S.; Nikzad, E. Multiple Sclerosis: Pathogenesis, Symptoms, Diagnoses and Cell-Based Therapy. Cell J. 2017, 19, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damjanovic, D.; Valsasina, P.; Rocca, M.A.; Stromillo, M.; Gallo, A.; Enzinger, C.; Hulst, H.; Rovira, A.; Muhlert, N.; De Stefano, N.; et al. Hippocampal and Deep Gray Matter Nuclei Atrophy Is Relevant for Explaining Cognitive Impairment in MS: A Multicenter Study. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2017, 38, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talebi, M.; Sadigh-Eteghad, S.; Talebi, M.; Naseri, A.; Zafarani, F. Predominant domains and associated demographic and clinical characteristics in multiple sclerosis-related cognitive impairment in mildly disabled patients. Egypt. J. Neurol. Psychiatry Neurosurg. 2022, 58, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balconi, J.; Langdon, D.; Dhakal, B.; Benedict, R.H.B. An Update on New Approaches to Cognitive Assessment in Multiple Sclerosis. NeuroSci 2025, 6, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hechenberger, S.; Helmlinger, B.; Tinauer, C.; Jauk, E.; Ropele, S.; Heschl, B.; Wurth, S.; Damulina, A.; Eppinger, S.; Demjaha, R.; et al. Evaluation of a self-administered iPad®-based processing speed assessment for people with multiple sclerosis in a clinical routine setting. J. Neurol. 2024, 271, 3268–3278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, S.; Losinski, G.; Mourany, L.; Schindler, D.; Mamone, B.; Reece, C.; Kemeny, D.; Narayanan, S.; Miller, D.M.; Bethoux, F.; et al. Processing speed test: Validation of a self-administered, iPad®-based tool for screening cognitive dysfunction in a clinic setting. Mult. Scler. J. 2017, 23, 1929–1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feys, P.; Lamers, I.; Francis, G.; Benedict, R.; Phillips, G.; LaRocca, N.; Hudson, L.D.; Rudick, R.; Multiple Sclerosis Outcome Assessments Consortium. The Nine-Hole Peg Test as a manual dexterity performance measure for multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. J. 2017, 23, 711–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motl, R.W.; Cohen, J.A.; Benedict, R.H.B.; Phillips, G.; LaRocca, N.; Hudson, L.D.; Rudick, R.; Multiple Sclerosis Outcome Assessments Consortium. Validity of the Timed 25-Foot Walk as an ambulatory performance outcome measure for multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. J. 2017, 23, 704–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, A.J.; Banwell, B.L.; Barkhof, F.; Carroll, W.M.; Coetzee, T.; Comi, G.; Correale, J.; Fazekas, F.; Filippi, M.; Freedman, M.S.; et al. Diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: 2017 revisions of the McDonald criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2018, 17, 162–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, M.W.; Repovic, P.; Mostert, J.; Bowen, J.D.; Comtois, J.; Strijbis, E.; Uitdehaag, B.; Cutter, G. The nine hole peg test as an outcome measure in progressive MS trials. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2023, 69, 104433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiaravalloti, N.D.; DeLuca, J. Cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis. Lancet Neurol. 2008, 7, 1139–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langdon, D.W.; Amato, M.P.; Boringa, J.; Brochet, B.; Foley, F.; Fredrikson, S.; Hämäläinen, P.; Hartung, H.-P.; Krupp, L.; Penner, I.; et al. Recommendations for a brief international cognitive assessment for Multiple Sclerosis (BICAMS). Mult. Scler. J. 2012, 18, 891–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calabrese, M.; Magliozzi, R.; Ciccarelli, O.; Geurts, J.J.G.; Reynolds, R.; Martin, R. Exploring the origins of grey matter damage in multiple sclerosis. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2015, 16, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dineen, R.A.; Vilisaar, J.; Hlinka, J.; Bradshaw, C.M.; Morgan, P.S.; Constantinescu, C.S.; Auer, D.P. Disconnection as a mechanism for cognitive dysfunction in multiple sclerosis. Brain 2009, 132, 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solaro, C.; Grange, E.; Di Giovanni, R.; Cattaneo, D.; Bertoni, R.; Prosperini, L.; Uccelli, M.M.; Malrengo, D. Nine Hole Peg Test asymmetry in refining upper limb assessment in multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2020, 45, 102422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Learmonth, Y.C.; Motl, R.W.; Sandroff, B.M.; Pula, J.H.; Cadavid, D. Validation of patient determined disease steps (PDDS) scale scores in persons with multiple sclerosis. BMC Neurol. 2013, 13, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, M.; Rinaldi, F.; Grossi, P.; Gallo, P. Cortical pathology and cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis. Expert. Rev. Neurother. 2011, 11, 425–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, T.; Tur, C.; Eshaghi, A.; Doshi, A.; Chan, D.; Binks, S.; Wellington, H.; Heslegrave, A.; Zetterberg, H.; Chataway, J. Serum neurofilament light and MRI predictors of cognitive decline in patients with secondary progressive multiple sclerosis: Analysis from the MS-STAT randomised controlled trial. Mult. Scler. J. 2022, 28, 1913–1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barros, C.; Fernandes, A. Linking Cognitive Impairment to Neuroinflammation in Multiple Sclerosis using neuroimaging tools. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2021, 47, 102622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, F.; Datta, S.; Garcia, N.; Rozario, N.L.; Perez, F.; Cutter, G.; Narayana, P.A.; Wolinsky, J.S. Intracortical lesions by 3T magnetic resonance imaging and correlation with cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. J. 2011, 17, 1122–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meijer, K.A.; Eijlers, A.J.; Douw, L.; Uitdehaag, B.M.; Barkhof, F.; Geurts, J.J.; Schoonheim, M.M. Increased connectivity of hub networks and cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis. Neurology 2017, 88, 2107–2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijer, K.A.; van Geest, Q.; Eijlers, A.; Geurts, J.; Schoonheim, M.; Hulst, H. Is impaired information processing speed a matter of structural or functional damage in MS? Neuroimage Clin. 2018, 20, 844–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalincik, T.; Manouchehrinia, A.; Sobisek, L.; Jokubaitis, V.; Spelman, T.; Horakova, D.; Havrdova, E.; Trojano, M.; Izquierdo, G.; Lugaresi, A.; et al. Towards personalized therapy for multiple sclerosis: Prediction of individual treatment response. Brain 2017, 140, 2426–2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landmeyer, N.C.; Bürkner, P.C.; Wiendl, H.; Ruck, T.; Hartung, H.-P.; Holling, H.; Meuth, S.G.; Johnen, A. Disease-modifying treatments and cognition in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: A meta-analysis. Neurology 2020, 94, e2373–e2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.H.; Goverover, Y.; Genova, H.M.; DeLuca, J. Cognitive efficacy of pharmacologic treatments in multiple sclerosis: A systematic review. CNS Drugs 2020, 34, 599–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampit, A.; Heine, J.; Finke, C.; Barnett, M.H.; Valenzuela, M.; Wolf, A.; Leung, I.H.K.; Hill, N.T.M. Computerized cognitive training in multiple sclerosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurorehabilit. Neural Repair 2019, 33, 695–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messinis, L.; Nasios, G.; Kosmidis, M.H.; Zampakis, P.; Malefaki, S.; Ntoskou, K.; Nousia, A.; Bakirtzis, C.; Grigoriadis, N.; Gourzis, P.; et al. Efficacy of a computer-assisted cognitive rehabilitation intervention in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis patients: A multicenter randomized controlled trial. Behav. Neurol. 2017, 2017, 5919841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charvet, L.E.; Yang, J.; Shaw, M.T.; Sherman, K.; Haider, L.; Xu, J.; Krupp, L.B. Cognitive function in multiple sclerosis improves with telerehabilitation: Results from a randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0177177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).