Abstract

Over the past decade, telehealth provision of care has become increasingly common. This shift away from in-person clinics may impact the experience of medical learners and the preceptors who train them. This study aimed to measure and compare obstetrics and gynecology resident physicians’ perceived quality of educational feedback during telemedicine compared to in-person clinical encounters. This prospective observational study recruited residents enrolled in a family planning clinical rotation at an academic residency program. After every in-person and telemedicine clinic session from January 2021 to February 2022, participating residents were sent a link to a 3 min survey via text message. Ordinal regression modeling was used to compare Likert responses between the telehealth and in-person clinical settings. All nine residents enrolled in the clinical rotation chose to participate in this study and responded to 114 of 132 survey prompts (86%). Participants positively rated the feedback they received during all clinic sessions. When comparing the two clinic experiences, there was no statistically significant difference in perceived quality of feedback or satisfaction with feedback. Residents’ perception of educational feedback during telemedicine clinic is at least similar for most measures and superior for contraception counseling when compared to an in-person clinic.

1. Introduction

Telemedicine has become increasingly important for abortion access in the United States [1]. During the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, telehealth provision of family planning care expanded rapidly due to the need to decrease clinician and patient exposure to the novel virus [2]. While abortion care can be provided via telehealth without compromising patient safety or satisfaction [3,4,5], little is known about how this sudden transition affects medical education. Currently, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) mandates that all graduating obstetrics and gynecology (ObGyn) resident physicians possess competency in educating patients on methods of abortion provision and contraception [6]. As more academic institutions integrate telehealth into family planning care, it is important to evaluate how this shift impacts the quality of medical training.

Prior to COVID-19, few studies explicitly discussed telehealth as a learning opportunity for physicians in training. A 2017 systematic review of 480 articles concerning telehealth noted that no studies mentioned the involvement of residency training programs or trainees [7]. Since COVID-19, multiple peer-reviewed articles have been published regarding the use of telehealth among medical trainees. However, these studies primarily focused on didactic education, comfortability with telehealth use, and trainee’s perceptions of patient care. Several papers have suggested benefits in resident education using telehealth for resident didactic lectures in the field of surgery [8,9,10]. Additionally, resident trainees have become increasingly comfortable with telehealth use and consider these opportunities to be valuable [11,12]. While a 2018 study of critical care residents found that 95% of these residents felt patients benefited from telehealth, almost half of studied residents felt their autonomy was decreased when using telehealth platforms [13]. This perceived lack of autonomy with telehealth education is concerning, because appropriate autonomy is an essential aspect of clinical training [14,15].

Constructive feedback from clinical faculty is another critical component of the medical learning cycle [16,17]. Providing feedback of sufficient quantity and quality, supervising clinicians help trainees identify and correct deficiencies in both knowledge and skill [17,18]. Effective feedback should be communicated in a timely fashion in a private space [19]. The content should be specific, actionable, and based on direct observation [18]. Ideally, feedback discussions should conclude with a confirmation of understanding from the trainee [19]. Improving feedback quality during clinical rotations remains a major focus of professional development for medical school faculty. However, given the complexities and importance of providing effective feedback, it remains unclear whether common practices of giving feedback are easily adapted to the telehealth setting.

In the context of the rapid and widespread adoption of telehealth in medical training, investigations into its educational impact are vital to ensure the next generation of graduating clinicians are skilled in providing care in both traditional and telehealth environments. Therefore, this study aimed to measure and compare ObGyn resident perception of the educational experience during synchronous telehealth versus in-person family planning clinic. Because the ACGME values both resident satisfaction with faculty feedback and resident perception of the appropriateness of faculty supervision, this study explored those two components of the resident experience [14]. The primary objective of this exploratory study was to measure and compare the perceived quality of feedback during both in-person and virtual clinical experiences. The secondary objectives were to measure perceived autonomy and evaluate the factors that predicted the perception of feedback in a cohort of residents. Because synchronous telehealth visits include two important components of high-quality feedback, direct observation and opportunities for timely discussion with faculty in a private space [18], it was hypothesized that the telehealth clinic setting may be associated with improved feedback quality but also a perception of inadequate autonomy.

2. Materials and Methods

The University of Hawaiʻi Human Studies Program determined this study to be exempt from full review by the Institutional Review Board. Using a repeated-measures design, this prospective observational study recruited ObGyn residents enrolled in a family planning rotation at the University of Hawaiʻi John A Burns School of Medicine. In 2016, this institution started offering telehealth provision of medication abortion and contraception. When the state of Hawaiʻi declared a public health emergency in March of 2020, the Complex Family Planning Clinic expanded telehealth services, offering multiple telehealth and in-person clinic sessions each week [20]. ObGyn residents participating in these clinic sessions were exposed to both telehealth and in-person training within the same rotation. All telehealth and in-person clinic sessions were supervised by academic faculty with fellowship training in Complex Family Planning. All supervising attendings participated in both in-person and telehealth clinic sessions. Telehealth sessions were synchronous including the patient, the resident, the attending, and potentially other learners.

The ObGyn residents were selected as a sample of convenience for the present study. Eligibility criteria included any ObGyn resident participating in this clinic. All eligible residents were invited to participate via email before the start of the rotation. All interested participants provided written consent and completed an anonymous, three-item demographic questionnaire. Participants attended regularly scheduled in-person and telehealth clinics focusing on contraception and abortion care. After each clinic session, participants were contacted via text message with a link to a three-minute, web-based survey created with REDCap electronic data-capture tools (see Figure 1) [21,22]. This survey was developed by the study authors and included fourteen questions using five-point Likert scales and one free response prompt (see supplementary Figure S1). The survey questions collected data related to perceived quality of feedback and satisfaction with feedback. Additional questions explored factors which appear to contribute to trainee educational experience based on previous publications [14,16,18,19,23,24]. These measures included (1) whether they were given specific examples during feedback, (2) whether they felt encouraged, (3) whether they agreed with the feedback they received, and (4) whether they had the appropriate level of autonomy. These factors were selected based on the ACGME guidelines that an optimal educational experience should include high-quality feedback, appropriate supervision, and autonomy for residents [14]. Surveys were not sent on days the participants did not attend the clinic due to illness, vacation, or holidays.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of methods.

Because each resident attended multiple clinics per week during a 7-week rotation, each single participant filled out the same survey multiple times, providing separate feedback on each individual clinic session. Participants engaged in up to two half-days of in-person clinic and one half-day of telemedicine clinic each week. Therefore, each resident could potentially complete a maximum of 21 surveys during their 7-week rotation. To maintain anonymity, the survey did not collect identifiable information and the responses were analyzed in aggregate at the conclusion of data collection. All eligible participants were compensated with a small breakfast at the conclusion of the study regardless of whether they chose to participate. Statistical analysis was performed in SPSS (version 29). Chi square analysis was used to compare response rates of each cohort. Descriptive statistics were used to assess demographic characteristics. Ordinal regression modeling was used to compare Likert responses between the two clinical settings. To further evaluate predictors of feedback quality and satisfaction, a series of multiple ordinal regressions were performed with backwards elimination to remove non-significant variables in a stepwise fashion, producing two final models. Predictor variables in the original model included: clinic type (in-person versus telemedicine), use of examples during feedback, and feeling encouraged by feedback.

3. Results

All of the nine eligible residents consented to participate in this prospective study (see Table 1). From January 2021 to February 2022, 132 survey prompts were sent to the nine participating residents. During this 14-month period, 114 responses were received from nine participants, yielding an 86.3% overall response rate. Response rates differed significantly between the two settings. Of the 41 invitations sent following telemedicine clinic sessions, 29 surveys were completed (70.7%). Among the 91 invitations sent after in-person clinic sessions, 85 responses were received (93.4%; X2 = 12.4; p < 0.01). Mean number of surveys completed per participant was 12.6.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics (n = 9).

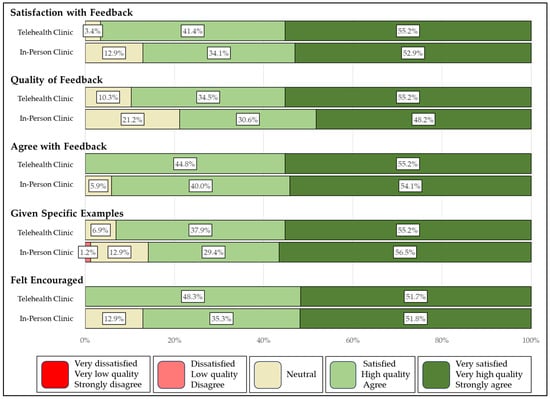

Overall, participants positively perceived the feedback they received during all clinic sessions. Eighty-nine percent of all clinic sessions left participants feeling ‘satisfied’ or ‘highly satisfied’ with feedback, and 81.6% of all clinic sessions included ‘high quality’ or ‘very high quality’ feedback. When comparing the two clinic settings (in-person versus telehealth clinic sessions), there was no statistically significant difference in satisfaction with this feedback (p = 0.5) or perceived quality of feedback (p = 0.3; see Figure 2). Regardless of the setting, most participants strongly agreed with the feedback they received (p = 0.7). Additionally, most participants strongly agreed that they were given specific examples of how to improve (p = 0.8) and felt encouraged by the feedback they received (p = 0.6).

Figure 2.

Evaluations of feedback after telehealth and in-person clinic.

In the final regression models for feedback quality and satisfaction, clinic type (in-person versus telehealth) did not significantly predict feedback quality or satisfaction. Instead, feeling encouraged and receiving specific examples during feedback were associated with a higher perceived quality of feedback and increased satisfaction (see Table 2). The adequacy of autonomy and level of agreement with feedback were not significant predictors and were removed from the final models.

Table 2.

Ordinal regression analysis predicting satisfaction and quality of feedback.

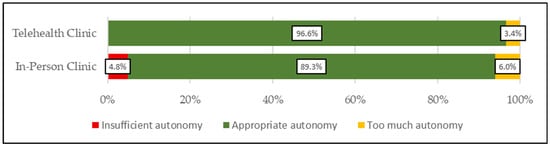

Most participants felt they were given appropriate autonomy in both the telehealth (96.6%) and the in-person clinic settings (89.3%; p = 0.3; see Figure 3). No participants reported insufficient autonomy during the telehealth clinic, whereas 4.8% of in-person clinic sessions were reported to involve not enough autonomy.

Figure 3.

Evaluations of autonomy during telehealth and in-person clinic.

4. Discussion

In this study, a cohort of ObGyn residents positively rated the feedback they received during both in-person and telehealth clinic sessions. There was no difference in the perceived quality of feedback or satisfaction with feedback between the two clinical education settings. These findings support the ongoing use of telehealth as an opportunity to train resident physicians.

For both settings, the use of specific examples and promoting feelings of encouragement were the only significant predictors of feedback quality and satisfaction, a finding which aligns with previous publications concerning best practices for in-person medical training [19]. This finding supports the conclusion that the characteristics of high-quality feedback remain consistent across in-person and virtual interfaces. Additionally, despite the physical limitations, telehealth clinics may create a virtual space that is equally or, in some cases, more accommodating of robust feedback practices than in-person clinic settings. For example, the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada promotes a coaching model as part of building learner competency [16]. In this model, clinical educators engage in coaching feedback, wherein they provide specific and actionable suggestions within a safe environment based on direct observations. When engaging in this coaching feedback, synchronous telemedicine encounters may naturally create repeated opportunities for direct observations of learners engaged in patient care, a vital step in the medical learning cycle [17,25]. Telemedicine may also provide a safe virtual space for faculty to provide timely and ongoing feedback, another important characteristic of formative feedback [19,26].

Previous publications have emphasized the need for telemedicine-specific rubrics and faculty development programming focused on telehealth teaching [27,28]. In contrast, the current study did not include any telehealth-specific training for involved faculty, yet the surveyed residents maintained a positive assessment of faculty feedback and supervision. This finding suggests some of the skills required to create a positive in-person learning environment may be transferable to the telehealth setting.

Additionally, this study found no difference in the appropriateness of resident autonomy during in-person and telehealth clinic sessions. The majority of clinic sessions in both settings provided autonomy that was perceived to be appropriate by the participating residents. Prior to starting the current study, the authors hypothesized that the direct supervision of the synchronous telehealth clinic would positively impact feedback quality but negatively impact progressive autonomy. In contrast to this study’s hypothesis, there was a non-significant trend towards having more autonomy during telehealth clinic compared to in-person clinic. Surveyed residents reported receiving high-quality feedback without inhibiting autonomy of practice. Resident autonomy is often viewed as having an inverse relationship with faculty supervision [29]. However, the self-determination theory (SDT) poses that educators should strive to provide autonomy-supportive supervision [30]. Within this SDT framework, both autonomy and feedback to promote competency coexist as essential components of medical training. Further, the current study’s finding also contrasts with a 2018 study in which almost half of critical care residents felt they had inadequate autonomy during telehealth experiences [13]. However, the 2018 study surveyed residents about telehealth, but did not provide surveys about in-person clinical experiences for comparison. The present study’s use of in-person clinic as a control is a major strength, allowing for more meaningful conclusions.

In addition to the inclusion of data from in-person clinics as a comparison, another strength of this study is the novel approach that allowed for the rapid evaluation of a new curriculum change. Traditionally, medical learners complete annual evaluations of clinic rotations which may require years to assess the value of program updates. This study collected real-time feedback in a relatively short period of timeframe, which may be useful to residency programs seeking to evaluate the value of curricular changes.

The limitations of this study include the small, homogenous sample size. The participants were a convenience sample at a single institution in a specific rotation, which may limit the generalizability to other resident programs. Additionally, all study participants identified as female, which is likely a reflection of the national trend for the ObGyn specialty. In fact, 83.5% of physicians starting an ObGyn residency in 2020 were female [31]. Despite this limited sample, the outcomes of interest in this study, including resident perception of feedback and autonomy, are universal to clinical teaching and likely not specific to female ObGyn residents. Additionally, the survey was not validated. Although the surveys remained anonymous, acquiescence bias cannot be ruled out. This study relied on repeated measures from participants. The survey was designed to be brief and convenient to complete, but participants may have experienced response fatigue which could bias the results. Finally, although the overall response rate is high, the in-person clinic sessions yielded a higher response rate than the telehealth clinics. The authors speculate that social desirability bias (in which a participant does not want to complete a survey with negative ratings) or the logistics of completing the survey after telehealth may have contributed to this trend towards lower response rates after telehealth clinics. Because of both this higher response rate after in-person clinics and the larger total number of in-person clinic sessions, the analysis included a larger proportion of survey responses concerning the in-person clinic educational experience. Despite this imbalance, the response rate after the telehealth visits remains acceptable for this study’s analysis.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrated that ObGyn resident perception of feedback and autonomy during the telemedicine family planning clinic is comparable to perceived feedback quality and autonomy during the in-person clinic. These findings are especially relevant for learners at institutions without in-person abortion training due to an increasing number of logistical and legal barriers. This outcome supports the development of remote training opportunities for these learners. Researchers in other specialties should continue to evaluate the educational experiences of medical trainees as in-person visits shift to more telehealth platforms in order to assure graduating physicians are appropriately trained to provide safe and high-quality care to patients in both settings.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ime4020019/s1, Supplementary Figure S1: Survey tool.

Author Contributions

All four authors have substantially contributed to this submission. Conceptualization, P.N.S. and M.N.; methodology, P.N.S., H.O. and K.C.; study recruitment, K.C.; data collection, K.C.; formal analysis, P.N.S.; writing—original draft preparation, K.C. and P.N.S.; writing—review and editing, H.O., M.N. and P.N.S.; visualization, P.N.S.; supervision, P.N.S.; project administration, P.N.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The University of Hawaiʻi Human Studies Program determined this study to be exempt from full review (protocol # 2020-00583).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset generated and analyzed during the current study is not publicly available to ensure the ongoing privacy of the participants. When thoughtfully considering data sharing, there was concern that the identity of specific respondents could be inferred or predicted given this study involves repeated measures of a small known sample.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ACGME | Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education |

| ObGyn | Obstetrics and Gynecology |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus 2019 |

References

- Raymond, E.; Chong, E.; Winikoff, B.; Platais, I.; Mary, M.; Lotarevich, T.; Castillo, P.W.; Kaneshiro, B.; Tschann, M.; Fontanilla, T.; et al. TelAbortion: Evaluation of a direct to patient telemedicine abortion service in the United States. Contraception 2019, 100, 173–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chong, E.; Shochet, T.; Raymond, E.; Platais, I.; Anger, H.A.; Raidoo, S.; Soon, R.; Grant, M.S.; Haskell, S.; Tocce, K.; et al. Expansion of a direct-to-patient telemedicine abortion service in the United States and experience during the COVID-19 pandemic. Contraception 2021, 104, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerestes, C.; Murayama, S.; Tyson, J.; Natavio, M.; Seamon, E.; Raidoo, S.; Lacar, L.; Bowen, E.; Soon, R.; Platais, I.; et al. Provision of medication abortion in Hawai ‘i during COVID-19: Practical experience with multiple care delivery models. Contraception 2021, 104, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerestes, C.; Delafield, R.; Elia, J.; Chong, E.; Kaneshiro, B.; Soon, R. “It was close enough, but it wasn’t close enough”: A qualitative exploration of the impact of direct-to-patient telemedicine abortion on access to abortion care. Contraception 2021, 104, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stifani, B.M.; Smith, A.; Avila, K.; Boos, E.W.; Ng, J.; Levi, E.E.; Benfield, N.C. Telemedicine for contraceptive counseling: Patient experiences during the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic in New York City. Contraception 2021, 104, 254–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2023. Available online: https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/pfassets/programrequirements/220_obstetricsandgynecology_2023.pdf (accessed on 24 May 2025).

- Sharma, R.; Clark, S.; Torres-Lavoro, J.; Dhaded, A.; Hsu, H.; Greenwald, P. Telemedicine in the emergency department: A novel, academic approach to optimizing operational metrics and patient experience. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2017, 70, S128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marttos, A.C., Jr.; Juca, F.; Moscardi, M.; Fiorelli, R.K.A.; Pust, G.D.; Ginzburg, E.; Schulman, C.I.; Grant, A.A.; Namias, N. Use of telemedicine in surgical education: A seven-year experience. Am. Surg. 2018, 84, 1252–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, C.H.; Schenarts, K.D. Evolving educational techniques in surgical training. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 2016, 96, 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyers, L.N.; Schultz, A.; Baceviciene, R.; Blaney, S.; Marvi, N.; Dellavalle, R.P.; Dunnick, C.A. Teledermatology as an educational tool for teaching dermatology to residents and medical students. Telemed. J. E Health 2015, 21, 312–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afshari, M.; Witek, N.P.; Galifianakis, N.B. Education research: An experiential outpatient teleneurology curriculum for residents. Neurology 2019, 93, 170–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papanagnou, D.; Stone, D.; Chandra, S.; Watts, P.; Chang, A.M.; E Hollander, J. Integrating telehealth emergency department follow-up visits into residency training. Cureus 2018, 10, e2433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dang, B.; Taylor, B.; Moore, K.; Taylor, S. The effect of ICU telemedicine on resident perceptions of education, autonomy, and patient care. Crit. Care Med. 2018, 46, S391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Guide to the Common Program Requirements (Residency). 2024. Available online: https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/pdfs/guide-to-the-common-program-requirements-residency.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Crockett, C.; Joshi, C.; Rosenbaum, M.; Suneja, M. Learning to drive: Resident physicians’ perceptions of how attending physicians promote and undermine autonomy. BMC Med. Educ. 2019, 19, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, D.; Landreville, J.M.; Trier, J.; Cheung, W.J.; Bhanji, F.; Hall, A.K.; Frank, J.R.; Oswald, A. Coaching in competence by design: A new model of coaching in the moment and coaching over time to support large scale implementation. Perspect. Med. Educ. 2024, 13, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, A.; van Diggele, C.; Roberts, C.; Mellis, C. Feedback in the clinical setting. BMC Med. Educ. 2020, 20, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branfield Day, L.; Miles, A.; Ginsburg, S.; Melvin, L.M. Resident perceptions of assessment and feedback in competency-based medical education: A focus group study of one internal medicine residency program. Acad. Med. 2020, 95, 1712–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.B.; Chiu, A.M. Assessment and feedback methods in competency-based medical education. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2022, 128, 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Office of the Governor. Emergency Proclamation, COVID-19. 2020. Available online: https://dod.hawaii.gov/hiema/emergency-proclamation-covid-19/ (accessed on 18 June 2023).

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.A.; Thielke, R.; Payne, J.; Gonzalez, N.; Conde, J.G. Research electronic data capture (REDCap): A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J. Biomed. Inf. 2009, 42, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Minor, B.L.; Elliott, V.; Fernandez, M.; O’Neal, L.; McLeod, L.; Delacqua, G.; Delacqua, F.; Kirby, J.; et al. REDCap Consortium: The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software partners. J. Biomed. Inf. 2019, 95, 103208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, A.R.; Wright, A.S.; Kim, S.; Horvath, K.D.; Calhoun, K.E. Educational feedback in the operating room: Gap between resident and faculty perceptions. Am. J. Surg. 2012, 204, 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.J.; Clark, M.J.; Meyerson, S.L.; Bohnen, J.D.; Brown, K.M.; Fryer, J.P.; Szerlip, N.; Schuller, M.; Kendrick, D.E.; George, B. Mind the gap: The autonomy perception gap in the operating room by surgical residents and faculty. J. Surg. Educ. 2020, 77, 1522–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffa, B.; Muellers, K.; Andreadis, K.; Ancker, J.S.; Flower, K.B.; Horowitz, C.R.; Kaushal, R.; Lin, J.J. A qualitative study on using telemedicine for precepting and teaching in the academic setting. Acad. Med. 2023, 98, 1204–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, H.N.; Opara, I.N.; Dwaihy, R.L.; Acuff, C.; Brauer, B.; Nabaty, R.; Levine, D.L. Engaging third-year medical students on their internal medicine clerkship in telehealth during COVID-19. Cureus 2020, 12, e8791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lesselroth, B.; Monkman, H.; Palmer, R.; Kuziemsky, C.; Liew, A.; Foulks, K.; Kelly, D.; Wolfinbarger, A.; Wen, F.; Kollaja, L.; et al. assessing telemedicine competencies: Developing and validating learner measures for simulation-based telemedicine training. AMIA Annu. Symp. Proc. 2024, 2023, 474–483. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rueda, A.E.; Monterrey, A.C.; Wood, M.; Zuniga, L.; Rodriguez, B.D.R. Resident education and virtual medicine: A faculty development session to enhance trainee skills in the realm of telemedicine. Mededportal 2023, 19, 11302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Happel, J.P.; Ritter, J.B.; Neubauer, B.E. Optimizing the balance between supervision and autonomy in training. JAMA Intern. Med. 2018, 178, 959–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawatsky, A.P.; O’Brien, B.C.; Hafferty, F.W. Autonomy and developing physicians: Reimagining supervision using self-determination theory. Med Educ. 2022, 56, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Data Resource Book: Academic Year 2019–2020. 2020. Available online: https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/pfassets/publicationsbooks/2019-2020_acgme_databook_document.pdf (accessed on 11 May 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Academic Society for International Medical Education. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).