Abstract

The rapid growth and seasonal availability of agricultural materials, such as straws, stalks, husks, shells, and processing wastes, present both a disposal challenge and an opportunity for renewable fuel production. Solar-assisted thermochemical conversion, such as solar-driven pyrolysis, gasification, and hydrothermal routes, provides a pathway to produce bio-oils, syngas, and upgraded chars with substantially reduced fossil energy inputs compared to conventional thermal systems. Recent experimental research and plant-level techno-economic studies suggest that integrating concentrated solar thermal (CSP) collectors, falling particle receivers, or solar microwave hybrid heating with thermochemical reactors can reduce fossil auxiliary energy demand and enhance life-cycle greenhouse gas (GHG) performance. The primary challenges are operational intermittency and the capital costs of solar collectors. Alongside, machine learning (ML) and AI tools (surrogate models, Bayesian optimization, physics-informed neural networks) are accelerating feedstock screening, process control, and multi-objective optimization, significantly reducing experimental burden and improving the predictability of yields and emissions. This review presents recent experimental, modeling, and techno-economic literature to propose a unified classification of feedstocks, solar-integration modes, and AI roles. It reveals urgent research needs for standardized AI-ready datasets, long-term field demonstrations with thermal storage (e.g., integrating PCM), hybrid physics-ML models for interpretability, and region-specific TEA/LCA frameworks, which are most strongly recommended. Data’s reporting metrics and a reproducible dataset template are provided to accelerate translation from laboratory research to farm-level deployment.

1. Introduction

Agriculture worldwide generates hundreds of millions of tons of lignocellulosic waste annually. This includes rice straw, wheat straw, maize stover, sugarcane bagasse, coconut husk, and more. Burning these leftovers in the open air and letting them rot without control adds to air pollution, regional haze, and CO2 equivalent emissions that could be avoided. Converting waste into bio-oil, syngas, and stable carbon products, such as biochar, is a circular solution that provides both distributed energy resources and soil amendment products. Pyrolysis, gasification, and hydrothermal liquefaction (HTL) are the primary thermochemical conversion methods for turning lignocellulosic and wet agro-residues into fuels [1,2]. Conventional thermal systems require a significant amount of fossil-fuel-based thermal or electrical energy to generate heat. However, suppose we adopt this process heat with concentrated solar thermal energy or a solar-microwave hybrid heating system. In that case, we can significantly reduce fossil fuel consumption and emissions, provided we address the economics and intermittency of solar collectors [3,4,5,6,7]. Recent experimental and pilot studies have demonstrated that CSP-driven and solar-assisted pyrolysis systems can achieve the requisite reactor temperatures (typically 400–700 °C across various pyrolysis regimes) and yield levels comparable to those of fossil-heated systems under optimal conditions [8].

Nevertheless, techno-economic analyses emphasize that capital expenditures and the variability of direct normal irradiance (DNI) are pivotal factors influencing competitiveness. At the same time, AI and ML techniques have become valuable tools for research on biomass conversion [9,10,11,12,13,14]. ML has been employed to forecast proximate and ultimate properties from rapid spectroscopic data, to model product distributions across extensive operational ranges, to create efficient surrogates for computationally intensive reactor models, and to optimize multi-objective trade-offs, such as maximizing bio-oil yield while minimizing tar and NOx emissions [15,16,17,18,19,20].

Combining solar integration with AI-driven process design is a promising approach to accelerate scaling, enhance the efficiency of intermittent operation with storage, and reduce the number of experiments required to parameterize different feedstocks. However, the field faces challenges with data fragmentation, a lack of standardized reporting, and a scarcity of large datasets, which limit the practical applications of AI models. This review brings together research that (i) classifies feedstocks and conversion pathways; (ii) solar-integration modes with thermochemical reactors; (iii) the role of AI/ML in prediction, control, and optimization; (iv) techno-economic and life-cycle insights; and (v) research gaps and standardized reporting recommendations to speed up reproducible research and commercialization.

2. Methodology

This study employs a combined methodological approach, incorporating a comprehensive literature review of both experimental investigations and numerical work. The experimental part focused on preparing agro-waste-derived biomass for combustion testing. Selected agricultural residues, such as rice husk, sugarcane bagasse, groundnut shell, and corn cob, were collected, dried, size-reduced, and processed into briquettes. Recent analyses were performed to determine moisture, volatile matter, fixed carbon, ash content, and elemental composition. Combustion characteristics were studied under controlled operating conditions to evaluate ignition behavior, flame temperature, and emission parameters.

The review covered peer-reviewed publications indexed in Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar databases from 2009 to 2025. Keywords such as “agricultural waste,” “biomass combustion,” “agro-residue fuel,” and “bioenergy conversion” were used to focus on diversifying technical areas and their combinations. Studies were shortlisted based on relevance to combustion efficiency, emission performance, and environmental sustainability.

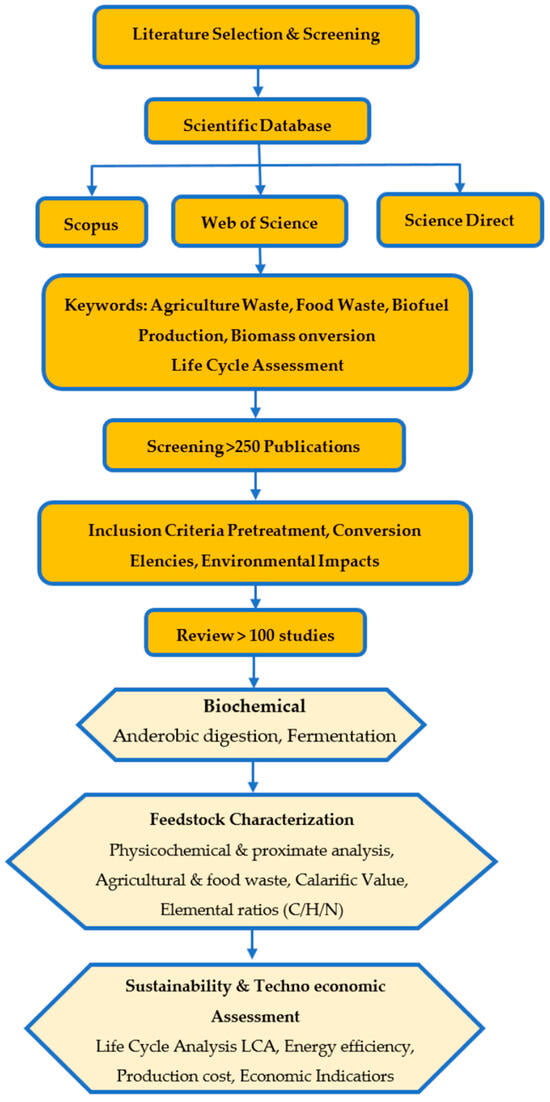

This methodology provided both practical insights and theoretical validation of biomass combustion performance, as presented in Figure 1. The integrated data were analyzed to establish correlations among feedstock properties, combustion conditions, and resulting emission profiles, thereby highlighting the feasibility of agricultural waste as a sustainable solid fuel source.

Figure 1.

Schematic Layout of Review Process of the Study. In this figure, yellow color indicates collection of articles from different journal sources and light lemon color indicates technical parameters focused to project in review articles.

3. Classification of Feedstock to Pathway to Product

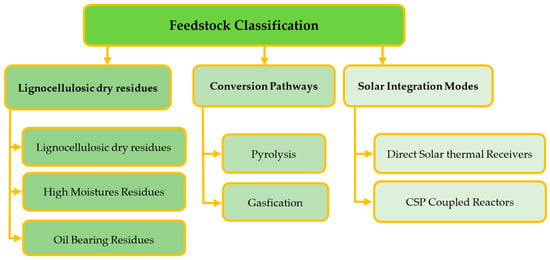

A systematic procedure is essential for mapping biomass-to-energy technologies to both their end uses and solar-integration strategies. We propose a three-level scheme presented in (Figure 2, Table 1). They are (A) Feedstock class, (B) Conversion pathway, and (C) Solar integration mode.

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of feedstock classification, conversion pathways, and solar-integration modes for sustainable bioenergy production. The color variations and gradients represent the different feedstock classifications and their corresponding types.

Table 1.

Classification of feedstock, conversion, and product details [21,22,23,24,25,26].

3.1. Feedstock Classification

Agricultural residues differ significantly in composition, density, and inherent moisture, which strongly governs their compatibility with specific thermochemical routes. This study reviewed their specifications individually for better understanding.

3.1.1. Lignocellulosic Dry Residues

Rice and wheat straw, corn stover, sugarcane bagasse, and peanut shells are Lignocellulosic dry residues [27,28,29,30]. These low-moisture (<15%) fibrous materials are amenable to conventional pyrolysis and gasification. James A. Gomez et al. [31]. Plantain agro-industry residues (leaf sheaths, peels, rachis) were valorized in a multi-input bio-refinery using independent processing of lignocellulosic and starchy fractions, simulated in Super Pro Designer. Leaf sheaths underwent fiber extraction, while 25% each of peels and rachis were processed via starch liquefaction, yielding optimized bio-product distribution and an NPV of $21.3M. This demonstrates that lignocellulosic dry residues can be effectively integrated into fraction-specific thermochemical pathways for achieving high-value bio-fiber and bio-fuel production. Harsh V. Rambhia et al. [32] used coconut shell, a lignocellulosic dry residue, in their research, which was co-pyrolyzed with thermoplastics using Thermo-Gravimetric Analysis (TGA) and Distributed Activation Energy Modeling (DAEM) to optimize fuel and chemical production. The apparent activation energies ranged from 187 to 199 kJ/mol for coconut shells and from 169 to 360 kJ/mol for plastics, highlighting different thermal decomposition behaviors. This study demonstrates that co-pyrolysis of lignocellulosic residues with polymers can enhance energy recovery and broaden the product spectrum for sustainable biofuel production. Rufis Fregue Tiegam Tagne et al. [33] investigated the conversion of African lignocellulosic residues from coffee and pineapple skins into bio-hydrogen via dark fermentation after alkaline H2O2 pretreatment to release fermentable sugars. It included pH 6 and 1.25% H2O2, yielding up to 92 mL H2/g VS, demonstrating efficient H2 production. This work highlights that chemical pretreatment, combined with controlled fermentation, can significantly enhance the valorization of lignocellulosic waste for sustainable bioenergy. María del Carmen Recio-Ruiz et al. [34] demonstrated that the pyrolysis of hemp hurd, olive stone, almond shell, and technical lignins showed that the bio-polymeric composition governs product yields and applications. Residues with higher lignin content produced gases with a heating value of 23 MJ/m3, a solid yield of 58%, and phenolic-rich bio-oils, whereas hemp hurd yielded micro-porous chars, achieving a CO2/CH4 selectivity of up to 53. These research findings highlight the potential for the integral valorization of all pyrolysis fractions, enabling autothermal operation above 500 °C and application-specific product tailoring.

3.1.2. High-Moisture Residues

High-moisture residues encompass agro-industrial and food-processing wastes such as fruit pomace, olive mill residues, winery lees, vegetable slurries, and algal biomass. These materials typically contain more than 60 wt% water, making conventional drying before thermochemical conversion highly energy-intensive. As a result, hydrothermal liquefaction (HTL) and anaerobic digestion (AD) have emerged as the most suitable valorization pathways because they can process wet biomass under subcritical aqueous conditions (250–370 °C, 10–20 MPa) without prior drying.

Parisa Niknejad et al. [35] explored the co-digestion of source-separated organics (SSO) and bioplastics through a coupled high-solid anaerobic digestion (HSAD)–HTL system. The HSAD phase achieved methane yields of 96–182 mL/g VS, while subsequent HTL at 330 °C maximized bio-crude yield (38 wt%) and enhanced the higher heating value (HHV). This hybrid configuration mitigated bioplastic accumulation and promoted a circular bio-economy, simultaneously producing biogas and hydrocarbon-rich oil fractions.

In a subsequent study, Niknejad et al. [36] extended this framework to biodegradable disposables, highlighting differential degradation behavior between compostable bags and utensils. Compostable bags reduced methane yield by 29.5%, while utensils reduced it by 9% during HSAD. The subsequent HTL step (280–350 °C) fully liquefied the residual bioplastics, improving oil quality and reducing oxygen content. These findings confirm the synergistic potential of sequential HSAD–HTL systems for waste-to-fuel conversion and microplastic mitigation.

Similarly, Oluwayinka M. Adedeji et al. [37] investigated the co-hydrothermal liquefaction of beverage residues (winery lees and brewery trub) and sewage sludge, generating an aqueous co-product (ACP) enriched in dissolved organics suitable for AD. The co-HTL–AD process yielded 317 mL CH4/g COD and achieved an energy recovery efficiency of 80.6%, outperforming single-feed systems. However, the study also noted the requirement for K+, Ca2+, and Mg2+ supplementation to sustain microbial activity during AD of the aqueous fraction.

Kamaldeep Sharma et al. [38] developed an integrated HTL–AD valorization approach using biogas digestate as a secondary feedstock. The resulting solid HTL mineral product contained 48–52 wt% C, 3.1–3.5 wt% P, and 1.1–1.2 wt% N, confirming its potential as a slow-release organic fertilizer. Nutrient recovery efficiencies reached 90% for phosphorus (as struvite and hydroxyapatite), with 70% bioavailability in agronomic assays. This dual-resource recovery pathway, which combines energy and fertilizer, exemplifies the principles of a closed-loop circular bio-economy, thereby reducing reliance on synthetic fertilizers, detailed information are illustrated in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of high-moisture residue valorization via hydrothermal liquefaction and anaerobic digestion.

Collectively, these studies highlight that coupled HTL–AD systems achieve high conversion efficiencies, maximize carbon and nutrient recovery, and mitigate wastewater toxicity. Yet, key challenges remain in scaling pressure-resistant reactor systems, mitigating corrosion from acidic intermediates, and developing low-cost catalysts for selective depolymerization of mixed organic wastes. The table below, based on references [35,36,37,38], summarizes the valorization of high-moisture residue via hydrothermal liquefaction and anaerobic digestion.

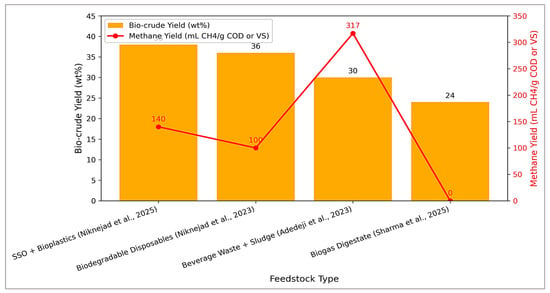

Figure 3 illustrates the comparative energy recovery and product yields obtained from different high-moisture residue valorization systems discussed in Section 3.1.2. It clearly shows that hybrid HSAD–HTL and co-HTL–AD configurations outperform single-stage processes in both bio-crude yield and methane generation. While the SSO + bioplastics and biodegradable disposables systems [35,36] achieve the highest bio-crude yields (36 to 38 wt%) through efficient hydrothermal depolymerization of organic fractions, the co-HTL of beverage waste and sewage sludge [37] demonstrates superior methane recovery (317 mL CH4/g COD) due to enhanced microbial conversion of the aqueous co-product. The biogas digestate-based HTL system [38] exhibits lower fuel yields but provides significant benefits in nutrient recycling, underscoring a complementary trade-off between energy recovery and resource circularity. Together, these results confirm the potential of integrated HTL–AD systems as a sustainable solution for managing high-moisture agro-industrial wastes while maximizing both carbon and nutrient recovery.

Figure 3.

Comparative Performance of HTL–AD Systems for High-Moisture Residues. References [35,36,37,38] are referred to in this figure.

3.1.3. Oil-Bearing Residues

Following the valorization of high-moisture residues through hydrothermal liquefaction and anaerobic digestion, another promising category comprises oil-bearing agro-residues such as Jatropha, neem, sunflower, groundnut, and coconut shells. These residues contain substantial quantities of residual triglycerides and fatty acids, making them particularly suited to co-pyrolysis, catalytic cracking, or solvent-assisted liquefaction for bio-oil and biodiesel precursor production. Their higher intrinsic calorific values (30–35 MJ kg−1) enable enhanced liquid-phase yields and improved product stability compared with carbohydrate-dominated feedstocks.

Victor I. Ameh et al. [39] optimized the pyrolysis of Gmelina arborea seed waste, a non-edible oil-bearing biomass, to overcome the limitations of transesterification-based biodiesel production. At 485 °C, 0.9 mm particle size, and a heating rate of 40 °C min−1, a 54 wt% % pyrolytic oil yield was achieved, with an HHV = 33.7 MJ kg−1 and 81.9 wt% % volatiles, aligning with ASTM fuel specifications. GC-MS analysis confirmed the presence of 67.5% cyclic monoterpenes and no sulfur compounds, validating the product’s suitability as a sulfur-free, high-energy-density biofuel.

V.A. Ajayi and A. Lateef [40] discussed the biotechnological valorization of melon seed shells, groundnut shells, and peels, emphasizing enzymatic hydrolysis and microbial fermentation as complementary routes to thermochemical conversion. They identified these residues as underutilized due to their lignin–cellulose complexity and anti-nutritional factors, yet rich in valuable phenolic and lipid fractions. Modern biorefinery strategies can thus integrate lipid extraction, biocatalytic conversion, and thermal upgrading, thereby contributing simultaneously to SDGs 3, 9, 12, and 13, which focus on health, resource efficiency, and climate action.

Further, Manurung et al. [41] demonstrated the fast pyrolysis of Jatropha curcas L. nut shells within a continuous bench-scale system (2.27 kg h−1 feed, 480 °C). The process generated 50 wt% % bio-oil, 23 wt% % char, and 17 wt% syngas, confirming the potential of Jatropha residues as a second-generation biofuel source. The oil exhibited a heterogeneous chemical composition, featuring oxygenated aromatics and long-chain hydrocarbons, indicative of both fuel and chemical precursor potential.

Overall, oil-bearing agro-residues bridge the gap between lipid-rich crops and lignocellulosic waste, yielding bio-oils with lower oxygen content and superior heating values, although they require pretreatment or blending to control nitrogen and ash content. Integrating solar-assisted pyrolysis or microwave-enhanced heating could further improve energy efficiency and product selectivity by reducing external fossil input, aligning these processes with the broader solar-biorefinery framework outlined earlier. Table 3 summarizes the performance of selected oil-bearing agro-residues, emphasizing their bio-oil yields (30–54 wt%) and high heating values (25–34 MJ kg−1) across different thermochemical and biotechnological pathways. These results reinforce the discussion above, demonstrating that oil-bearing residues such as Gmelina arborea, Jatropha curcas, and groundnut shells provide energy-rich, low-oxygen biofuels that complement the high-moisture and lignocellulosic feedstocks discussed earlier. Integrating such lipid-rich residues within solar-assisted or hybrid biorefineries can further enhance process efficiency and product selectivity, advancing the circular bioeconomy framework introduced in preceding sections.

Table 3.

Representative Studies on the Valorization of Oil-Bearing Agro-Residues [39,40,41].

3.2. Conversion Pathways and Typical Products

The conversion of agro-residues into biofuels and value-added products primarily relies on thermochemical routes such as pyrolysis, gasification, and hydrothermal liquefaction (HTL), each governed by distinct temperature, pressure, and feedstock moisture conditions. These processes transform heterogeneous agricultural wastes into energy-dense intermediates, bio-oil, syngas, and biochar, which can be upgraded or directly utilized depending on end-use requirements. Figure 2 and Table 1 earlier established the mapping of feedstock types to conversion modes; this section outlines the performance and applicability of each route based on representative studies.

3.2.1. Pyrolysis

Pyrolysis is one of the most extensively studied thermochemical processes for transforming agro-residues into biofuels and carbon-rich co-products. It involves the thermal decomposition of biomass in an oxygen-limited environment, typically at 400–700 °C, producing three primary products: biochar, bio-oil, and syngas. The relative proportions of these products depend strongly on operational parameters such as heating rate, residence time, particle size, and reactor configuration. Generally, slow pyrolysis favors char production, fast pyrolysis maximizes bio-oil yield, and intermediate regimes balance all three streams.

Recent research highlights pyrolysis as a versatile approach for managing lignocellulosic and oil-bearing residues, while generating renewable fuels and soil amendments. Sasidhar and Murugavelh [42] optimized the pyrolysis of cashew nut shells and husks, reporting that shells exhibited higher thermal degradation rates and energy values than husks. At optimal conditions, 600 °C for shells and 450 °C for husks, the process achieved yields of 44–50 wt% bio-oil, confirming a strong economic potential with internal return rates above 15%. Similarly, Rathod et al. [43] demonstrated that slow pyrolysis of groundnut shells produced up to 27 wt% bio-oil, 30 wt% biochar, and 55 wt% syngas, achieving energy and exergy efficiencies of 84% and 79%, respectively.

Beyond energy recovery, pyrolysis also supports carbon circularity. The resulting biochar can serve as a soil conditioner, enhancing fertility and promoting long-term carbon sequestration, while the bio-oil, once upgraded through hydride-oxygenation or catalytic cracking, provides a renewable alternative to fossil-derived fuels. When coupled with solar-assisted heating or microwave pretreatment, pyrolysis efficiency and selectivity can be further enhanced, reducing fossil input and improving reactor control. Altogether, these findings affirm pyrolysis as a technically robust and economically scalable route for valorizing diverse agro-wastes within an integrated solar-biorefinery framework.

3.2.2. Gasification

Gasification is a high-temperature thermochemical process that converts agricultural residues into syngas, a mixture primarily composed of hydrogen (H2), carbon monoxide (CO), carbon dioxide (CO2), and methane (CH4), through controlled partial oxidation. Operating typically between 700 °C and 1200 °C, gasification facilitates higher carbon conversion efficiency than pyrolysis and allows the resulting gas to be utilized for electricity generation, hydrogen production, or synthetic fuel synthesis. Its versatility and cleaner combustion profile make it particularly attractive for integrating with solar-driven reactors and fuel cell systems in the pursuit of carbon-neutral energy solutions.

Recent studies have demonstrated the adaptability of gasification to a wide range of agro-waste feedstocks. Basinas et al. [44] correlates the pyrolysis temperature (300–700 °C) with biochar yield (55–41.3 wt%), surface area (up to 116.1 m2; g−1), alkalinity (pH ≈ 11.5), and kinetic parameters (Ea: 83–180 kJ mol−1), demonstrating clear process property relationships. These quantified results substantiate the selection of high-temperature digestate biochars for enhanced soil fertility and improved anaerobic digestion stability and methane productivity. Nanda et al. [45] investigated the supercritical water gasification (SCWG) of fruit and agro-food residues, achieving H2 yields of up to 4.8 mol g−1 from coconut shells in the presence of a 2 wt% K2CO3 catalyst and an energy recovery of nearly 46%. This highlights the potential of catalytic enhancement in improving conversion efficiency under aqueous supercritical conditions. Similarly, Galvagno et al. [46] modeled and experimentally validated an integrated system for gasifying orange peels and solid oxide fuel cells (SOFCs). The setup processed 65 kg/h−1 of biomass with 20% moisture, generating 120 kW of DC power and 135 kW of heat, achieving a remarkable combined heat and power (CHP) efficiency of 74%. These outcomes emphasize the economic and energetic potential of coupling biomass gasification with high-efficiency power systems.

Additionally, Nisamaneenate et al. [47] optimized the gasification of cassava rhizome using a Ni/char catalyst, thereby reducing tar formation and increasing the H2/CO ratio to 1.22, thereby enhancing syngas quality and cold gas efficiency. Collectively, these findings confirm that catalytic and solar-assisted gasification not only improve thermal efficiency but also strengthen the environmental sustainability of agro-waste valorization. When integrated with solar heat or hybrid CSP systems, gasification offers a promising route to renewable hydrogen production and decentralized clean energy.

3.2.3. Solar–Microwave Hybrid Thermochemistry

Recent advances in biomass valorization have led to growing interest in solar–microwave hybrid thermochemical systems, which combine the renewable heat of concentrated solar energy with the precision of microwave-assisted heating. Conventional pyrolysis and gasification processes often rely on fossil fuels, limiting their sustainability. Hybrid systems overcome this by using solar flux (ranging from 800 to 1000 W m2) for bulk heating, while microwaves deliver rapid, volumetric heating at the molecular level. This integration improves energy efficiency, ensures uniform temperature distribution, and significantly reduces reaction time and secondary tar formation.

Soto-Díaz et al. [48] Demonstrates a novel solar-assisted synthesis of CaS-decorated biomass-derived activated carbon, achieving semispherical CaS nanoparticles (~30 nm), high electrochemical capacitance (~180 F g−1 at 2 V), and a specific energy of 14.42 Wh kg−1. The statistically validated influence of synthesis temperature (400–800 °C) and activating agent concentration (1–3 M), along with 50% capacitance enhancement after 15,000 cycles, confirms the robustness and electro-activation potential of the developed supercapacitor electrodes. Reddy et al. [49] demonstrated that microwave-assisted pyrolysis of groundnut shells at 600 °C achieved 38 wt% bio-oil and 30 wt% char, outperforming conventional electric heating. The resulting bio-oil contained more aromatic hydrocarbons and phenolics, with higher heating value and reduced oxygen content. Likewise, Soto-Díaz et al. [48] reported a 43.2 wt% bio-oil yield from the microwave pyrolysis of lignocellulosic residues, highlighting improved product selectivity and reduced energy demand. When solar preheating is introduced before microwave irradiation, total energy consumption decreases by 25–35% without compromising yield or composition.

Hybridization also enhances process flexibility: solar energy supplies steady-state heat, while microwave power compensates for solar intermittency, maintaining continuous operation. The resulting biochars exhibit a greater surface area and pore volume, while the bio-oils display higher energy density (30–35 MJ kg−1). Such systems provide a modular and decentralized solution for converting rural or agro-industrial waste, aligning with carbon-neutral biorefinery models. Overall, solar–microwave hybrid thermochemistry represents a promising and scalable pathway for producing sustainable fuels and materials from agro-residues, effectively bridging renewable energy utilization with efficient waste valorization.

Halil Atalay et al. [50] reported that a combined solar–wind drying system exhibits markedly improved thermodynamic performance, achieving exergy efficiencies of 68.04–83.89% during banana drying experiments. When compared quantitatively, the system delivers substantially higher exergy efficiency than both conventional solar dryers and solar-assisted hybrid configurations, while also demonstrating superior sustainability indicators. In addition, the short energy payback period of 1.36 years underscores the effectiveness of integrating multiple renewable sources for efficient, environmentally responsible drying applications.

Santhoshkumar and Anand Ramanathan [51] reported that hybrid renewable-assisted systems exhibit significantly better performance than conventional systems, with exergy efficiencies ranging from 68.04 to 83.89%. Quantitative comparisons show that hybrid configurations achieve approximately 57.7% higher exergy efficiency than conventional systems and 21.52% higher efficiency than solar-assisted hybrids, along with a reduced energy payback period of 1.36 years. These numerical improvements demonstrate the clear advantage of integrating renewable energy sources to enhance energy efficiency, sustainability, and economic feasibility.

3.3. Solar-Integration Modes

The integration of solar energy into thermochemical biomass conversion processes offers a sustainable means to reduce reliance on fossil fuels and enhance energy efficiency. By utilizing concentrated solar power (CSP) as a clean heat source, these systems provide the process temperatures required for pyrolysis, gasification, and reforming, thereby achieving near-zero carbon emissions. Depending on reactor design and heat delivery mechanisms, solar-assisted systems can be categorized into direct, indirect, and hybrid solar–electric configurations [49,50,51,52,53]. Each mode governs how solar energy interacts with the reaction zone, influencing conversion efficiency, reactor durability, and scalability.

3.3.1. Direct and Indirect Solar Heating

In direct solar heating, concentrators such as parabolic dishes, heliostat fields, or linear Fresnel reflectors focus solar radiation onto a reactor cavity containing the biomass. The focused solar flux, typically 800 to 1000 W/m2, enables a rapid temperature rise to 400 to 900 °C, facilitating efficient thermal decomposition. Studies by Z’Graggen et al. [52] and Adeniyi et al. [53] demonstrated that solar-driven pyrolysis of olive residues and nutshells achieved bio-oil yields of up to 50 wt% and thermal efficiencies exceeding 85%, surpassing those of conventional electric heating. Nonetheless, this mode demands high-temperature-resistant reactor materials and accurate solar tracking to maintain flux uniformity, particularly under intermittent irradiance conditions.

In indirect systems, solar radiation first heats an intermediate medium, such as molten salts, ceramic particles, or inert gases, that subsequently transfers heat to the biomass reactor. This approach isolates the reaction zone from direct radiation, enhancing temperature control and enabling continuous operation. Tregambi et al. [54] achieved stable solar gasification of wood and sludge in a particle-flow reactor at 850 °C, producing syngas with H2/CO ratios of 1.1–1.3. Similarly, Gómez-Barea et al. [55] integrated thermal energy storage into an indirect system, improving operational stability by 30–35% under fluctuating solar conditions. This configuration is therefore ideal for round-the-clock biomass conversion using stored solar heat.

3.3.2. Hybrid Solar–Electric Systems

Hybrid solar–electric systems represent a pragmatic evolution of solar-driven thermochemical processes by combining concentrated solar thermal energy with auxiliary electric or microwave heating to maintain steady operation during fluctuating solar conditions [48,49,56]. These systems typically operate at 600–900 °C, providing rapid heating, efficient conversion, and continuous process stability, even under intermittent sunlight.

Soto-Díaz et al. [48] reported that coupling solar preheating with microwave-assisted pyrolysis of agro-residues reduced total energy demand by 28%, while maintaining bio-oil yields of 40–45 wt% % and improving product selectivity. The integration of microwave heating provides volumetric energy absorption, reducing hot spots and ensuring more uniform decomposition. Similarly, Liang et al. [56] demonstrated that hybrid solar–plasma gasification achieved syngas efficiencies comparable to those of conventional electric gasifiers, while reducing CO2 emissions by nearly 40%.

Furthermore, Chidambaram Padmavathy et al. [57] investigated solar–electrical co-heating for biowaste gasification, observing a 23% improvement in hydrogen production efficiency, attributed to better temperature uniformity and plasma–solar synergy. These systems not only enhance overall thermal efficiency but also enable real-time process control by dynamically adjusting electrical input in response to solar irradiance. The hybrid approach thereby offers a resilient and adaptable configuration for distributed biorefineries, particularly suited for rural settings with abundant biomass resources and variable sunlight availability.

3.3.3. Outlook

The integration of direct, indirect, and hybrid solar-assisted systems in biomass thermochemistry represents a critical step toward sustainable, carbon-neutral energy production [49,52,55]. Direct solar heating enables rapid conversion and minimal tar formation, but it requires advanced materials and precise optical design. Indirect systems excel in thermal regulation and catalyst longevity, while hybrid systems ensure continuous operation and grid-compatible flexibility [56,57,58].

Future optimization efforts should focus on enhancing solar flux distribution, improving thermal storage media, and refining reactor control strategies. Emerging studies, such as those by Manurung et al. [41] and Kalogirou [50], emphasize integrating phase-change materials (PCMs) with ceramic particle storage units to achieve 24 h continuous operation. Moreover, innovations in machine learning–based predictive control, for example, in Reddy et al. [49], could automate power switching between solar and electric inputs, reducing energy losses and process downtime.

From an environmental standpoint, solar-assisted systems offer substantial benefits: life-cycle analyses indicate up to 60% reductions in CO2 emissions and 45% lower primary energy consumption compared with fossil-based thermochemical systems [53,57]. Economically, hybrid systems also show promise; modular installations with localized biomass supply chains can lower transportation costs and improve regional energy security.

In summary, solar-integrated biomass conversion, spanning direct, indirect, and hybrid configurations, forms the foundation of future circular bioenergy systems. Through material innovation, storage integration, and smart energy management, these technologies can transform agricultural residues into sustainable fuels, fertilizers, and value-added chemicals, closing the loop between renewable energy and waste management [55,58].

4. Solar-Assisted Thermochemical Technologies

This section synthesizes experimental and numerical simulation results, illustrating the performance of solar energy in supplying heat for thermochemical processes and its current capabilities and limitations.

4.1. Solar-Driven Pyrolysis: Lab to Pilot Demonstrations

Recent experimental and modeling studies demonstrate that concentrated solar power (CSP) collectors, such as parabolic troughs, Fresnel reflectors, and heliostat towers, can deliver sufficiently high thermal flux for fast and intermediate pyrolysis, achieving stable reactor temperatures exceeding 500 °C. These systems produce bio-oil and char yields comparable to fossil-fueled counterparts under optimal Direct Normal Irradiance (DNI) conditions [59]. However, reactor thermal stability remains a critical challenge, and thermal energy storage (TES) using sensible or latent heat media is essential to maintain process continuity during transient irradiance [56].

Experimental trials using Linear Fresnel Reflector (LFR) systems reported overall pyrolysis heat-delivery efficiencies of 20–25%, demonstrating operational viability in Mediterranean and tropical latitudes. Despite this progress, large-scale deployment remains limited by optical losses, capital intensity, and the need for standardized solar-reactor coupling geometries.

It was found that thermal energy storage (TES) is a critical component for the effective operation of solar-assisted thermochemical systems, particularly under fluctuating solar irradiance. By storing excess thermal energy during periods of high solar availability [ranging from 11 am to 3 pm] and releasing it during low-irradiance conditions [after 5 pm onwards], TES enables stable reactor temperatures and continuous process operation. For high-temperature thermochemical applications, storage approaches based on sensible heat using molten salts or ceramic media, as well as thermochemical storage systems, are more suitable due to their thermal resilience and energy density. Selecting an appropriate TES system requires careful consideration of operating temperature limits, storage capacity, heat retention, cyclic durability, and compatibility with reactor materials. Properly designed TES integration enhances system reliability, reduces reliance on auxiliary energy sources, and improves economic performance by increasing overall system utilization under variable solar conditions.

4.2. Solar-Microwave and Microwave-Assisted Pyrolysis

Solar-based strategies support to enhance renewable energy system performance, demonstrated by Colmenar-Santos et al [60] the techno-economic viability of hybridizing CSP plants with biogas to improve dispatchability and reduce electricity generation costs compared to molten salt storage, supported by case studies, waste availability analysis, and sensitivity assessment, while simultaneously addressing environmental waste valorization. Sanchez et al [61] provides a detailed solar pyrolysis model using an LFR system in Seville, identifying optimal operating conditions (571 K, 149 min), reactor design parameters (3.23 m length, 4.55 m2 aperture), and achieving a maximum char yield of 40.8 wt% with an annual production of 1375 kg biochar from 13.9 t biomass, collectively highlighting the potential of solar-assisted thermal processes for flexible, sustainable, and resource-efficient energy generation. Microwave-assisted pyrolysis (MAP) offers clear advantages over conventional pyrolysis (CP), including higher yields of combustible gases (H2, CH4, CO), bio-oils with elevated phenolic content and calorific value, and superior-quality biochar, as reported by Ahmed Elsayed Mahmoud Fodah [62]. Specifically, in reactor design, parameter modifications and catalyst selection have a critical influence on product distribution. Zeolites favor gas and biochar production, as well as metal-based catalysts, which enhance bio-oil yield and phenolic composition. By integrating MAP with pretreatments such as torrefaction or anaerobic digestion of feedstocks, product quality is further improved. Meanwhile, machine learning (ML) approaches enable the optimization of multiple interacting parameters [10,61,62]. This research highlights the mechanistic insights, technological challenges, and the potential for future scalability of MAP for industrial bioresource valorization.

Additionally, this MAP offers volumetric heating and rapid heating rates, which can enhance product quality and improve energy efficiency. Through this detailed research, we understand that combining solar preheating with microwave heating has been proposed as a means to reduce electrical microwave energy demand while achieving the desired heating profiles. This research indicates MAP produces higher gas fractions enriched in H2/CH4, higher-quality bio-char and phenolic-rich bio-oils, but requires microwave absorbers or pretreatment to ensure sufficient dielectric heating for typical agro-residues. Biochar, as a microwave substrate, has been demonstrated to enable MAP for low-loss feedstocks [63,64].

4.3. Hydrothermal Liquefaction and Solar Integration

For high-moisture residues, Hydrothermal liquefaction (HTL) is significantly preferred. Solar integration in HTL is less mature due to reactor pressure requirements; however, solar thermal heat can preheat feedstock and maintain thermal budgets, thereby reducing fossil boiler load [65,66,67,68,69,70]. Plethora research is ongoing into high-temperature solar receivers and heat exchangers compatible with pressurized HTL. In real experimental trials, HTL with solar heat remains an identified research gap [53,67,68].

Milica Mihajlovic et al. [71] conducted research work on Hydrothermal processing (HTP), which presents a sustainable pathway for mitigating the global plastic waste crisis by converting plastics into hydrochar, bio-oil, organic acids, and syngas under high-temperature, high-pressure aqueous conditions. Despite its potential for integration into the circular economy and environmental benefits, such as reduced reliance on virgin resources, large-scale adoption is limited by high energy demand, complex system design, and economic feasibility. The research produced 72 wt% hydrochar and 80 wt% bio-oil from a waste product, with 95% [hydrochar] and 98% [bio-oil] plastic degradation efficiency. Further focusing on process optimization, energy recovery through water recycling, and strategic policy support, including subsidies and carbon credits, is crucial to enhancing the techno-economic viability and enabling HTP to transition from pilot demonstrations to commercially scalable solutions.

4.4. Reactor Design Considerations for Solar Coupling

Effective solar–reactor coupling relies on uniform flux distribution, insulation against convective/radiative losses, and materials capable of withstanding cyclic thermal stress. Falling-particle receivers have gained attention for providing both direct heat transfer and inherent thermal storage.

Granular activated carbon (GAC) composites and photo-Fenton hybrids show promise for integrated pollutant control and heat management [71], supporting system-wide sustainability. Recent simulations by Martínez-Manuel et al. (2022) and Ischia et al. (2020) [53,72] showed that the study conducted at 180 to 220 °C for 2 h to evaluate absorption performance and achieved 95.6% at a 300 nm (wavelength). It revealed that surface absorbance stability under >400 kW/m2 flux is essential for long-term reactor efficiency. The development of spectrally selective solar absorber coatings (SACs) such as Pyromark-2500 maintains optical efficiency (>88%) after 1000 h of exposure, making them promising for commercial solar pyrolysis reactors.

Moreover, Table 4 presents a comparative performance summary of solar-assisted thermochemical systems, integrating the preceding section by quantifying operational efficiencies, temperature ranges, and technological constraints for the key solar-assisted conversion pathways. It reveals that each technology, whether solar-driven pyrolysis, solar-integrated hydrothermal liquefaction (HTL), or solar hydrothermal carbonization, operates within distinct thermal and design envelopes that influence both energy conversion and product distribution. The tabulated data emphasize that optimizing multiple interdependent parameters, such as reactor temperature, residence time, and solar flux stability, is critical to achieving sustainable performance gains. These complex, nonlinear interactions among process variables underscore the need for intelligent optimization techniques that can identify optimal operating points across dynamic solar and feedstock conditions. Consequently, the insights from Table 4 naturally transition to Section 5, where the roles of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and machine learning are explored as means to predict, model, and control such multifactorial processes, enabling more efficient and adaptive biomass-to-fuel conversion systems.

Table 4.

Comparative Performance of Solar-Assisted Thermochemical Systems.

Additionally, the high capital investment initially required for concentrated solar power (CSP) systems remains a significant challenge for large-scale implementation. Cost reduction can be achieved through modular, scalable receiver–reactor designs that lower manufacturing and installation costs, as well as through the development of low-cost, high-reflectivity heliostats. Advances in thermal energy storage materials and system integration can improve heat retention and reduce energy losses, thereby enhancing overall system efficiency. Coupling CSP units with existing industrial infrastructure increases capacity utilization and reduces additional capital expenditure. Furthermore, process intensification and AI-based operational optimization enable improved thermal efficiency, reduced operational downtime, and adaptive control under variable solar conditions. Hybridisation with auxiliary heat sources further mitigates intermittency issues, thereby improving reliability and economic performance.

5. Role of AI and Machine Learning in Biomass-to-Fuel Processes

Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) are becoming integral to advancing the efficiency, scalability, and precision of biomass-to-biofuel conversion technologies. These tools are being increasingly used to address multiple complex challenges in the valorization of agro-wastes, particularly those involving feedstock variability, reactor optimization, and real-time process control under dynamic solar-assisted conditions. Broadly, AI tools have tackled the following bottlenecks:

- (1)

- Rapid feedstock characterization and classification, eliminating slow, manual lab-based testing,

- (2)

- Development of surrogate models and predictive, predicting yields and emissions with high precision under variable conditions,

- (3)

- Multi-objective optimization and control, allowing real-time decisions under constraints of emissions, energy efficiency, product yield, and solar intermittency.

5.1. Feedstock Characterization and Feature Extraction

High-throughput spectroscopic techniques like NIR, MIR, and Raman were combined with supervised ML, specifically PLS, Random Forests, XG-Boost, and CNNs, which can predict the presence of proximate and ultimate analysis parameters like moisture, volatile matter, fixed carbon, and elemental composition far faster than experimental procedures. These predictions support the use of real-time data or pre-preparation for feedstock sorting to match the conversion pathway [72,73,74,75,76]. Recent research shows high accuracy when sufficient labeled data are available; however, it stresses the need for diverse, open datasets to avoid overfitting to narrow feedstock sets.

Recent studies have shown high prediction accuracy when sufficient and diverse labeled datasets are available. For example, Mohanraj Kumar et al. [77] successfully utilized ML to predict optimal enzyme loadings and pretreatment strategies for algal polysaccharides, significantly improving saccharification and fermentation efficiency in algal biorefineries. Similarly, Yeole et al. [78] demonstrated the potential of ANN-GWO hybrid models for estimating bio-oil yield from lignocellulosic feedstocks, showing strong correlation with experimental outcomes for rice husk and sawdust pyrolysis. However, the field still suffers from: (1) narrow dataset generalizability, (2) lack of standardized open-access databases, and (3) overfitting risks due to limited feedstock diversity.

Thus, standardization in dataset reporting (e.g., with JSON metadata and CSV format) is urgently needed to enhance the transferability of models across research labs and geographical contexts.

5.2. Modeling of Reactor Behavior Using Simulation

Detailed numerical models of pyrolysis or gasification in CFD require computationally intensive, complex kinetic networks for accurate predictions, which take longer. ML surrogates trained on experimental and numerical datasets by using Gaussian processes, tree ensembles, deep NNs, etcetera, provide rapid mapping from operating conditions to product precious yields and composition [78,79,80,81]. This alternative offers real-time optimization and uncertainty-aware decision-making. Recent research clearly demonstrated accurate yield prediction for complex feedstocks and validated the use of ML-based Bayesian optimization to find Pareto-optimal operating windows with far fewer experiments [82,83,84].

Ildefonso Caro et al. [85] proposed integrating kinetic models for simultaneous saccharification and fermentation, demonstrating the potential to optimize ethanol production from agricultural and food residues. Enzyme dosage and inoculum strength were identified as critical operating variables. However, experimental productivity remains below 5 mg. The predictive models estimated yields nearly twice those observed experimentally, underscoring the impact of integrated ML-kinetic approaches.

5.3. Physics-Guided ML Using PINNs and Hybrid Approaches

Pure data-driven models may fail when extrapolating to new feedstocks or reactor scales. Physics-informed neural networks (PINNs) and hybrid models that embed conservation laws or mechanistic kinetic constraints into ML models improve extrapolation and interpretability. The essential properties for process control in intermittent solar-driven setups are. The literature survey reveals an increasing number of hybrid model deployments, underscoring the need for accelerated research into code-based data sharing.

Muhammad Ahtasham Mushtaq et al. [86] reported that integrating AI and ML into horticultural crop management offers transformative potential for stress detection, predictive modeling, and precision interventions, thereby advancing climate-smart agriculture. Despite promising applications in irrigation optimization, image-based phenotyping, and multi-omics integration, barriers such as limited data accessibility, algorithmic bias, and high implementation costs constrain large-scale adoption. Overcoming these challenges through robust training, cost-effective frameworks, and open data platforms will be pivotal to achieving resilient, carbon-neutral fruit production under climate stress.

Shaojun Ren et al. [87] used the PINN model to predict the accurate performance of the emission gases produced during combustion, and the resulting data were trained using ML models. A 50-times random-sampling test was conducted, and it was observed that R2 achieved an accuracy of 0.91–0.97. Also, it reveals that this ML model plays a key role in predicting combined gas emissions and ensures scientific interpretability. Further research [86] using the Disentangled Representation-aided Physics-Informed Neural Network (DR-PINN) ML model predicted an inequality constraint and a monotonic relationship between feedstock and emission gases. The study achieved R2 = 0.96 for the training set, RMSE = 1.7, and for feedstocks outside the training set, R2 = 0.81 and RMSE = 3.

5.4. Optimization and Control Under Intermittency

Solar intermittency adds a temporal dimension to optimization. AI algorithms have been proposed and applied in simulated environments to model predictive control with ML, reinforcement learning for scheduling with storage, and Bayesian experimental design for adaptive campaigns, improving the operational level to achieve maximum LHV yield while constraining emissions and minimizing auxiliary fossil use. Recent experimental demonstrations of closed-loop ML control in solar-driven reactors are still rare and point to a potential research area.

Azmirul Hoque et al. [88] integrated AI, remote sensing, and IoT into innovative greenhouse solar dryers, marking a significant advancement in precision agriculture that enables faster, energy-efficient, and high-quality dehydration of fruits and spices. These technologies enhance sustainability by reducing drying time, energy consumption, and carbon emissions, while blockchain and real-time monitoring improve traceability, product safety, and operational efficiency. Collectively, they minimize post-harvest losses and support carbon credit verification, demonstrating substantial potential to transform agri-food processing and advance environmentally sustainable agricultural practices.

Lu Liu et al. [89] demonstrate that hybrid biogas produced by solar-driven multi-generation systems integrating electricity, freshwater, hydrogen, cooling, and post-combustion CO2 capture offers a highly efficient and sustainable solution to meet growing energy and environmental demands. Coupling ORC and Kalina cycles with waste heat recovery units and solar-assisted CO2 capture significantly enhances energy efficiency and reduces fossil fuel dependency, and lowers the system’s carbon footprint. Sensitivity and parametric analyses, complemented by ML-based GA-ANN optimization. This research reveals substantial economic benefits, including a reduced payback period and increased NPV, highlighting the feasibility of deploying such integrated multi-energy systems for environmentally and financially sustainable operation.

To further synthesize the current state of research, Table 5 consolidates the diverse applications of AI and machine learning across the biomass-to-fuel conversion value chain. This comparative overview highlights the specific techniques employed, target variables, and operational benefits derived in each subdomain. Understanding these intersections is crucial as we transition into the discussion on combustion-related parameters, where fuel quality and emissions performance remain critical for downstream applications.

Table 5.

Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Applications Across Biomass-to-Fuel Conversion Stages.

6. Fuel Quality, Emissions, and Combustion Considerations

The combustion readiness and environmental performance of biofuels derived from solar-assisted thermochemical processes are critical to their adoption at scale. As these biofuels are intended for use in distributed power systems, co-firing, internal combustion engines, or industrial heat processes, their quality must meet technical standards related to energy density, stability, and emissions. This section discusses the combustion-relevant characteristics of the significant products, bio-oil, biochar, and syngas, while addressing their environmental implications and the emerging role of AI in predicting and enhancing these properties.

Bio-oil, predominantly produced through pyrolysis or hydrothermal liquefaction (HTL), is a complex mixture of oxygenated compounds, including carboxylic acids, aldehydes, ketones, and phenolics. These confer several undesirable characteristics, such as high acidity (pH 2–4), high viscosity, and immiscibility with fossil fuels. Furthermore, the oxygen content (30–50 wt.%) leads to lower heating values (16–20 MJ/kg) and poor thermal stability, limiting its direct use in combustion engines without upgrading. Methods such as hydrodeoxygenation (HDO), emulsification with diesel, and catalytic cracking are commonly applied to enhance its fuel quality. Recent AI-assisted frameworks have been developed to screen catalyst combinations, predict HDO performance, and identify optimal pyrolysis parameters for higher phenolic yield and reduced acid formation. For example, Yeole et al. [78] employed an artificial neural network gray wolf optimizer (ANN-GWO) model to estimate bio-oil yields from agricultural feedstocks such as rice husk and sawdust with high predictive accuracy. Similarly, Fodah et al. [62] demonstrated that microwave-assisted pyrolysis (MAP), particularly when combined with AI-optimized susceptors and catalysts, can enhance the energy content and stability of bio-oil.

Biochar, another key product of pyrolysis and torrefaction, has applications as a solid fuel and soil amendment. Its combustion performance is dictated by its fixed carbon content (often >60%), volatile matter, ash composition, and surface area. High fixed-carbon biochars exhibit calorific values of 22–30 MJ/kg, making them suitable for co-firing in thermal plants or for briquetting for domestic use. However, elevated ash levels or the presence of heavy metals (depending on the feedstock) may contribute to particulate emissions or the release of toxic trace elements. Rathod et al. [43] reported that slow pyrolysis of groundnut shells produced biochars with favorable combustion efficiency and energy yields. In a complementary study, Mahmoud Fodah et al. [62] reported that biochar produced via MAP exhibited enhanced porosity and a higher specific surface area, thereby improving both combustion and adsorption performance.

Syngas, obtained through gasification and supercritical water gasification (SCWG), contains varying proportions of H2, CO, CH4, and CO2. Its calorific value (4–10 MJ/Nm3) and suitability for downstream utilization depend on the H2/CO ratio and tar content. A key challenge is tar formation, which impairs engine operation and synthesis gas cleaning. Syngas intended for Fischer–Tropsch synthesis, ammonia production, or hydrogen fuel cells must maintain a H2/CO ratio near unity and exhibit tar levels below 100 mg/Nm3. To achieve this, catalytic gasification using materials such as Ni-char composites has shown promise. For instance, Nisamaneenate et al. [47] demonstrated that cassava rhizome gasification using a Ni/char catalyst reduced CO2 and tar content while enhancing the syngas LHV and H2/CO ratio. AI and machine learning models are increasingly applied to predict gas composition and tar formation across a wide range of operating conditions, facilitating the design of robust gasification systems.

The emissions generated from biofuel combustion, such as nitrogen oxides (NOx), sulphur oxides (SOx), particulate matter (PM2.5), carbon monoxide (CO), and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), vary depending on the fuel type, feedstock origin, and combustion conditions. The detailed biomass conversion comparisons were presented in Table 6. Accurate quantification and control of these emissions are essential for regulatory compliance and for mitigating health risks. AI-based models are being used to predict emission profiles from various feedstocks and combustion setups. Nevertheless, field validation of these models remains limited, highlighting the need for comprehensive emissions datasets from pilot- and full-scale trials.

Table 6.

Comparison of Biomass Conversion Products to Industry Standards.

An insightful study by Vershinina et al. [90] examined the combustion and emission behavior of waste-derived fuel blends in various forms —pellets, wet slurries, and granules—across a range of moisture contents. Their findings showed that low-moisture mixtures rich in woody biomass ignited faster and combusted more completely, achieving lower oxidation thresholds and reduced carbon residues. In contrast, pelleted coal sludge exhibited delayed ignition and incomplete burnout, leading to higher unburned carbon and potential pollutant release. Notably, slurry and wet granule formats of coal sludge enhanced fuel conversion and reduced NOx emissions due to water-induced thermal moderation. These results emphasize the importance of considering fuel form and moisture content in combustion system design and highlight the need for predictive combustion models calibrated on real fuel behavior. Integrating AI with combustion datasets from such studies could further improve real-time optimization of operational parameters, ensuring cleaner and more efficient energy recovery from complex biofuel blends.

From a systems perspective, these fuel products also support circular bioeconomy strategies. High-quality, clean-burning biofuels derived from agro-waste provide renewable energy solutions while mitigating open burning, landfill accumulation, and fossil fuel dependency. Demichelis et al. [91] observed that Italy’s agro-food waste, when valorized through integrated biorefineries, can yield energy-rich fuels, generate economic returns, and reduce emissions. The success of such initiatives relies on ensuring that fuel properties meet technical standards and that environmental impacts are mitigated. Here, integrating AI frameworks for feedstock characterization, emissions forecasting, and combustion control can play a transformative role in advancing both performance and sustainability.

In conclusion, the combustion performance of solar-derived biofuels is governed by a complex interplay of fuel properties, feedstock variability, and system design. Bio-oil requires upgrading to match fossil fuel standards; biochar offers high energy density but may require emissions control; syngas quality depends on H2/CO ratios and tar mitigation strategies. AI-based tools are increasingly supporting the upgrading of these parameters, contributing to a more predictable and environmentally sound utilization of thermochemical biofuels. Future research should focus on field-scale validation of AI-assisted combustion models and the development of harmonized datasets linking fuel characteristics to emissions and thermal performance. Table 7 summarizes the combustion-relevant characteristics of thermochemical biofuels, bio-oil, biochar, and syngas, highlighting their typical energy content, associated technical challenges, and upgrade needs. It also illustrates how artificial intelligence tools are increasingly leveraged to optimize quality prediction, emissions control, and process efficiency across these fuel types.

Table 7.

Combustion-Relevant Properties of Thermochemical Biofuels and the Role of AI.

7. Techno-Economic Analysis and Life-Cycle Assessment

Techno-economic assessments (TEA) of solar-driven thermochemical systems suggest they can reduce operational costs and life-cycle greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions under favorable conditions such as high direct normal irradiance (DNI), low-cost collectors, and optimized thermal storage integration [92]. Key sensitivity parameters in TEA include (a) capital costs and optical efficiency of solar collectors (parabolic trough, Fresnel, heliostat), (b) seasonal DNI variability and its impact on capacity factor, (c) feedstock logistics such as transportation, drying, and seasonal availability, and (d) the economic value of co-products like biochar and syngas in various markets. These factors significantly affect plant sizing and cost competitiveness.

Pankaj Garkoti and Sonal K. Thengane [93] demonstrate that circular economy (CE)-based biogas plants in both rural and urban Indian contexts can achieve economic viability and environmental sustainability. Rural biogas plants utilizing rice straw and cattle dung exhibit a higher net present value ($3.24 million) due to the increased solid content, resulting in greater compressed biomethane (CBG) and fertilizer production. Similarly, urban plants using sewage sludge and municipal organic waste also show positive returns ($1.30 million), albeit lower than those in rural setups.

A life cycle assessment reveals that methane leakage, composting, and membrane separation are the primary contributors to greenhouse gas emissions. In rural plants, climate impacts are slightly higher due to increased feedstock and composting emissions. Sensitivity analysis reveals the significant effect of CBG and CO2 selling prices, feedstock costs, and discount rates on economic performance. These findings offer actionable insights for designing and implementing CE-based biogas systems in India, balancing techno-economic feasibility with climate change mitigation objectives.

The study by Kai Chen Goh et al. [94] highlights that waste-to-energy (WtE) technologies offer an effective and sustainable strategy for managing restaurant food waste in Malaysia and Singapore. Among anaerobic digestion, pyrolysis, and gasification, anaerobic digestion has emerged as the most promising, achieving up to 60% waste reduction, generating 5 MW of renewable energy per year, and providing a favorable 12–15% return on investment with a 5–7-year payback period.

Life cycle assessment indicates significant environmental benefits, including a reduction of 0.8 kg CO2 per kg of food waste compared to landfilling. With supportive policies, technological improvements, and community engagement, it is possible to add 75 MW of renewable energy, powering over 30,000 homes, advancing the circular bio-economy, and contributing to multiple United Nations Sustainable Development Goals.

Y.P. Ragini et al. [95] emphasize that agricultural and food waste biomass represent abundant, cost-effective, and high-lignocellulose feedstocks for sustainable biofuel production, addressing both energy demand and waste management challenges. Recent advances in pretreatment and biorefinery processes, coupled with techno-economic and life cycle assessments, have enhanced the efficiency, environmental sustainability, and economic feasibility of biofuel production. The integration of advanced conversion technologies and comprehensive process enhancement ensures effective utilization of feedstock, positioning waste-derived biofuels as a viable alternative to fossil fuels while supporting circular bioeconomy strategies.

The research reviewed shows that experimental and numerical studies focused solely on short-term or seasonal research for specific products. It is essential that multi-season operational data, including thermal storage, component degradation, and weather-dependent performance, be available to assess the technical performance of the products, which will support a detailed techno-economic analysis (TEA) and life-cycle assessment (LCA). Based on short-term or steady-state data, research often underestimates performance variability in solar-assisted systems. Therefore, incorporating multi-season operational data allows accurate representation of weather-dependent solar availability, thermal storage charging and discharging behavior, and component degradation over time. Long-term datasets improve estimation of capacity factors, maintenance costs, embodied emissions, and system reliability, leading to more realistic cost-of-energy and environmental impact assessments. This approach reduces uncertainty and enhances confidence in large-scale deployment decisions.

Additionally, the high capital costs of concentrated solar power systems remain a key barrier to widespread adoption. Based on the research, it is concluded that cost-reduction strategies are most important and can be achieved by incorporating modular receiver-reactor designs, low-cost heliostat manufacturing, advanced thermal energy storage materials, and integration with existing industrial infrastructure to improve capacity utilization. Moreover, process intensification and AI-driven operations highly optimize and further reduce levelized energy costs by enhancing thermal efficiency, minimizing downtime, and enabling flexible operation. Hybridization with auxiliary heat sources can also mitigate intermittency and improve economic viability.

8. Gaps, Challenges, and Research Priorities

Significant progress has been achieved in solar-driven pyrolysis and related thermochemical systems for biofuel production; however, critical research and deployment challenges remain. One of the most pressing limitations is the absence of widely accepted, AI-compatible datasets that link feedstock physicochemical descriptors with reactor operating conditions, product yields, compositional profiles, and emissions outputs. This data gap considerably constrains the generalization and reproducibility of machine learning (ML) models [15]. Establishing standardized formats, such as CSV files embedded with JSON metadata, would facilitate data sharing, interoperability, and model training across research platforms.

Despite numerous experimental demonstrations of solar pyrolysis, long-term, multi-seasonal datasets that incorporate thermal storage behavior, component degradation, and weather-dependent performance remain scarce. This undermines the robustness of techno-economic analysis (TEA) and life-cycle assessment (LCA), particularly in regions with variable solar resources. In such contexts, integrating spatially resolved and GIS-based modeling, as already demonstrated for biomass supply chains and renewable energy siting, can help bridge data gaps and improve decision-making for siting, logistics, and infrastructure planning for solid waste valorization [93,94,95,96,97].

Furthermore, most current ML applications in biomass-to-energy systems are still dominated by black-box models trained on limited data, which restricts interpretability and extrapolation. There is a clear need for hybrid approaches that embed thermodynamic and kinetic constraints, such as physics-informed neural networks and surrogate models constrained by mass and energy balances, to ensure that predictions remain physically plausible even in sparsely sampled regions of the design space. Variability in experimental reporting practices, for example, inconsistent characterization of solar flux, reactor residence time distributions, or off-gas sampling protocols, further complicates model training and comparison. Internationally harmonized validation protocols and uncertainty reporting would therefore be a valuable complement to open datasets.

Future research should address both fundamental and system-level challenges associated with solar-assisted thermochemical technologies by advancing detailed reaction mechanism analysis, including pathway identification and characterization of intermediate species under hybrid and transient heating conditions. Emphasis is required on dynamic and transient system modeling to capture fluctuating solar input, thermal inertia, and start-up/shutdown behavior, supported by the development of high-temperature, corrosion-resistant sensors for real-time diagnostics and closed-loop control. Long-term studies on the durability of materials, including reactor alloys, coatings, seals, and insulation, are essential to mitigate corrosion, fouling, and thermal fatigue in harsh hydrothermal and high-temperature environments. Establishing standardized benchmarking metrics, such as reference feedstocks and canonical operating windows, will facilitate cross-study comparisons and accelerate learning curves.

At the same time, system-level integration with industrial heat networks, waste management infrastructure, and energy grids, alongside safety-oriented and regulatory-compliant design approaches, will be critical for accelerating the transition from laboratory-scale demonstrations to commercial deployment. The capital-intensive nature of concentrating solar power (CSP) infrastructure and the fragmented, often informal, biomass supply chains present structural barriers to bankable project development [25,26]. To mitigate these constraints, supportive policy interventions are required, including capital grants or concessional financing for pilot-scale solar–biomass facilities, fiscal incentives for feedstock aggregation and pre-treatment, and the establishment of carbon-credit or results-based finance mechanisms linked to biochar and other negative-emission co-products. In line with stakeholder-focused renewable energy planning approaches, embedding socio-technical frameworks and participatory governance into project design can enhance public acceptance, ensure that benefits accrue to local communities [98,99,100], and improve the long-term viability of solar-assisted thermochemical valorization pathways.

9. Conclusions

Solar-assisted thermochemical conversion of agricultural residues offers a promising route to decarbonize decentralized energy systems while valorizing biomass that would otherwise be sent for open burning or landfill disposal. Recent experimental and techno-economic studies confirm the feasibility of CSP-integrated pyrolysis and hybrid solar–microwave systems, particularly in high-DNI regions with optimized thermal storage. Parallel advances in machine learning are accelerating feedstock screening, surrogate model development, and multi-objective process optimization, thus reducing experimental burden and enhancing system controllability.

Nevertheless, commercialization remains constrained by the lack of AI-ready datasets linking feedstock properties to product distributions, limited field-scale demonstrations with thermal storage, and insufficient interpretability in black-box AI models. Furthermore, heterogeneity in experimental reporting obstructs cross-study comparison and meta-analysis. To overcome these barriers, coordinated efforts are needed to develop standardized data templates, pilot deployments across varied agro-climatic zones, and hybrid modeling frameworks that integrate mechanistic insights with data-driven prediction. Policy support through capital grants and carbon offset mechanisms will be pivotal in scaling solar-assisted pyrolysis as a core technology in the circular bioeconomy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.V.K., D.R., S.R.; methodology, B.V.K., S.R., D.R.; investigation, B.V.K., D.R., S.R.; formal analysis, B.V.K., S.R., D.R.; writing—original draft, B.V.K., D.R., S.R.; writing—review and editing, S.R., D.R., H.Y.; visualization, B.V.K., D.R., S.R.; supervision, D.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability Statement

All data are reported in this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript

| CSP | Concentrated Solar Thermal |

| GHG | Greenhouse Gas |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| PCM | Phase change materials |

| DNI | Direct Normal Irradiance |

| HTL | Hydrothermal Liquefaction |

| TGA | Thermo-Gravimetric Analysis |

| DAEM | Distributed Activation Energy Modeling |

| HSAD | High-Solid Anaerobic Digestion |

| ACP | Aqueous Co-Product |

| AD | Anaerobic Digestion |

| CV | Calorific Value |

| JCL | Jatropha curcas L. |

| SCWG | Supercritical water gasification |

| SOFC | Solid Oxide Fuel Cells |

| CHP | Combined Heat and Power |

| MPAS | Multi-Point Air Supply. |

| SACs | Solar absorber coatings |

| SFB | Soot From Forest Biomass |

| EFB | empty fruit bunches |

| ORC | Organic Rankine Cycle |

| EFGT | Externally Fired Gas Turbine |

| MAP | Microwave Assisted Pyrolysis |

| SPF | Solar Photo-Fenton |

| GAC | Granular Activated Carbon |

| TEA | Techno-Economic Analysis |

| LCA | Life-Cycle Assessment |

| CBG | Compressed Biomethane |

| WtE | Waste-To-Energy |

References

- Adams, P.; Bridgwater, T.; Lea-Langton, A.; Ross, A.; Watson, I. Biomass conversion technologies. In Greenhouse Gases Balances of Bioenergy Systems; Adams, P.T.A.P., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moodley, P. Sustainable Biofuels: Opportunities and Challenges. Sustain. Biofuels 2021, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lackner, M.; Besharati, M. Agricultural waste: Challenges and solutions, a review. Waste 2025, 3, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rekik, S. Optimizing Green Hydrogen Strategies in Tunisia: A Combined SWOT–MCDM Approach. Sci. Afr. 2024, 26, e02438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rekik, S.; Khabbouchi, I.; Eladeb, A.; Alshammari, B.M.; Kolsi, L. A Spatio-Techno-Economic Analysis for Wind-Powered Hydrogen Production in Tunisia. Alex. Eng. J. 2025, 128, 833–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, S.; Nassar, Y.F.; Algassie, H.; Mahammed, A.; El-Khozondar, H.; Elmnifi, M.; Salem, M. Exploring Optimum Sites for Exploitation of Hydropower Energy Storage Stations (PHES) Using the Geographic Information Systems (GIS) in Libya. Sol. Energy Sustain. Dev. J. 2025, 14, 394–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rekik, S.; Khabbouchi, I.; El Alimi, S. A Spatial Analysis for Optimal Wind Site Selection from a Sustainable Supply-Chain-Management Perspective. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Pornrungroj, C.; Linley, S.; Reisner, E. Strategies to improve light utilization in solar fuel synthesis. Nat. Energy 2021, 7, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weldekidan, H.; Strezov, V.; Town, G. Review of solar energy for biofuel extraction. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 88, 184–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano-Gómez, C.I.; Wong-Arguelles, C.; Hinojosa-López, J.I.; Muñiz-Márquez, D.B.; Wong-Paz, J.E. Novel insights into agro-industrial waste: Exploring techno-economic viability as an alternative source of water recovery. Waste 2025, 3, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, P.R.; Moon, J.-H.; Ogunsola, N.O.; Lee, S.H.; Ling, J.L.J.; You, S.; Park, Y.-K. Recent advances and future prospects of thermochemical biofuel conversion processes with machine learning. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 471, 144503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateescu, C.; Tudor, E.; Dima, A.-D.; Chiriță, I.; Tanasiev, V.; Prisecaru, T. Artificial Intelligence Approach in Predicting Biomass-to-Biofuels Conversion Performances. In Proceedings of the 2022 23rd International Carpathian Control Conference (ICCC), Sinaia, Romania, 29 May–1 June 2022; pp. 370–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parveen, F.; Slater, A.G. Digitalisation of Catalytic Processes for Sustainable Production of Biobased Chemicals and Exploration of Wider Chemical Space. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2025, 15, 1689–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Peng, X.; Xia, A.; Shah, A.A.; Huang, Y.; Zhu, X.; Zhu, X.; Liao, Q. The role of machine learning to boost the bioenergy and biofuels conversion. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 343, 126099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaseen, Z.M.; Alawi, O.A. Artificial intelligence models development for profitability factor prediction in concentrated solar power with dual backup systems. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 5058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascher, S.; Watson, I.; You, S. Machine learning methods for modelling the gasification and pyrolysis of biomass and waste. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 155, 111902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandelwal, K.; Dalai, A.K. Prediction of Individual Gas Yields of Supercritical Water Gasification of Lignocellulosic Biomass by Machine Learning Models. Molecules 2024, 29, 2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, M.; Yao, Y. Applications of artificial intelligence-based modeling for bioenergy systems: A review. GCB Bioenergy 2021, 13, 774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olafasakin, O.O.; Chang, Y.-H.; Passalacqua, A.; Subramaniam, S.; Brown, R.C.; Wright, M.M. Machine Learning Reduced Order Model for Cost and Emission Assessment of a Pyrolysis System. Energy Fuels 2021, 35, 9950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onsree, T.; Tippayawong, N. Machine learning application to predict yields of solid products from biomass torrefaction. Renew. Energy 2020, 167, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balopi, B.; Moyo, M.; Gorimbo, J.; Liu, X. Biomass-to-electricity conversion technologies: A review. Waste Dispos. Sustain. Energy 2025, 7, 323–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartolucci, L.; Cordiner, S.; Maina, E.D.; Mulone, V. Flexible polygeneration of drop-in fuel and hydrogen from biomass: Advantages from process integration. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 315, 118812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brassard, P.; Godbout, S.; Hamelin, L. Framework for consequential life cycle assessment of pyrolysis biorefineries: A case study for the conversion of primary forestry residues. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 138, 110549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]