Abstract

The juice industry generates substantial quantities of solid waste and wastewater. Consequently, efforts have focused on their treatment and valorization to obtain high-value-added products. Traditionally, these wastes are managed through landfill disposal and treatment in municipal wastewater facilities, respectively. In the present work, two alternative scenarios for the valorization of orange juice waste were developed and assessed in comparison to the conventional approach by performing a Life Cycle Assessment (LCA). Scenario 1 involved hydro-distillation of solid waste for essential oil recovery, followed by anaerobic digestion for biogas and fertilizer production, with wastewater treated via membrane filtration and chlorination. In Scenario 2, solvent-free microwave extraction (SFME) was employed for essential oil recovery, followed by anaerobic digestion. Wastewater was treated in a membrane bioreactor followed by ultraviolet treatment. According to the results, Scenario 1 achieved a 36% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions due to the beneficial effects of biogas and fertilizer production, despite its high energy demands. Scenario 2 exhibited the best environmental performance due to lower energy demands and higher extraction efficiency compared to Scenario 1, with reductions of 46% in greenhouse gas emissions and 48% in resource depletion. Overall, the findings highlight the potential of integrating innovative, energy-efficient technologies for the sustainable valorization of juice industry waste, offering measurable environmental advantages for industrial-scale implementation.

1. Introduction

Orange, one of the most popular fruits worldwide, belongs to the citrus family and is a staple product of Mediterranean countries [1]. During the production of orange juice, approximately 50% of the fresh weight of the fruit ends up as wastes, with the total volume in Europe estimated at 2.5 million tons, which is often landfilled or incinerated, causing significant environmental impacts [2,3]. The generated solid wastes, which consist mainly of peel, pulp and seeds, which in total amount up to 50–70% of the mass of processed fruit, contain valuable components such as essential oils, phenolic compounds and pectin, thus constituting them ideal for the recovery of high-value-added products or the production biofuels, such as biogas [4,5,6]. Similarly, the wastewater, generated by orange washing, equipment cleaning and other processes, can exhibit great quantitative and qualitative variability and is influenced by factors such as season, water consumption and recirculation, and processing technology [7,8]. Traditionally, juice-processing solid residues are landfilled, where they contribute to long-term environmental burdens such as methane generation and land occupation, while the generated wastewater is treated in municipal wastewater treatment plants, where it undergoes standard removal of organic load without product recovery. Overall, the targeted and efficient valorization along with the appropriate treatment of the generated waste streams from the orange juice industry is vital in the context of circular economy and sustainability [9], with these principles being the cornerstones of sustainable and efficient product systems [10,11]. Various methods have been studied for the valorization of solid waste and the treatment of wastewater from the juice production industry, with many of them being characterized as highly effective [12].

Particularly, hydrodistillation is a conventional method for the extraction of water-insoluble components with a high boiling point, in which the orange waste is immersed in boiling water under atmospheric pressure and the produced gaseous mixture of steam and oil is condensed in order to isolate the essential oils in a decanter [13,14,15]. Simultaneously, the use of microwaves in the extraction process, based on dielectric heating, has led to the development of innovative techniques such as Microwave-Assisted Extraction (MAE), Microwave Hydrodistillation (MWHD) and Solvent-Free Microwave Extraction (SFME) [16,17,18], which offer shorter extraction times, lower energy consumption and higher yields, without the demand for use of organic solvents [16,19,20]. In particular, SFME, through the selective heating of the “in situ” water of plant tissues, allows the release of essential oils with high efficiency and has already been applied in industrial operations, while the scaling up of these processes exhibit even greater yields and energy efficiency [21,22,23,24]. In addition, anaerobic digestion is an important waste management technology, as it reduces the organic load and results in the production of biogas as a renewable energy source; however, its effective application to orange waste requires the removal of limonene, being toxic for methanogens, through methods such as dilution, co-digestion or phase separation, while advanced approaches such as two-stage digestion or the use of specialized bacteria improve the stability and efficiency of the process, contributing to the sustainable valorization of waste [25,26].

The treatment of wastewater from the orange juice industry can be effectively achieved through the coupling of modern technologies such as Membrane Bioreactor (MBR) with conventional ones, like chlorination and UV treatment. MBR combines biological treatment with membrane separation, achieving a high degree of removal of organic pollutants and suspended solids, as well as producing a high-quality effluent suitable for recycling or reuse [27]. Chlorination, a widely used disinfection method, is based on the addition of chlorine or sodium hypochlorite, ensuring the destruction of pathogenic microorganisms, although it requires careful control to avoid the formation of by-products such as trihalomethanes [28]. Finally, UV disinfection is a clean, fast and effective natural method, which inactivates microorganisms without the use of chemicals and without the generation of secondary pollutants [29].

The assessment of environmental impacts associated with industrial processes can be effectively conducted through Life Cycle Assessment (LCA), a comprehensive methodological framework that evaluates inputs, outputs, and potential environmental effects across all stages of a product’s life cycle [30]. The main purpose of LCA is to identify the key environmental hotspots during the various phases of production and propose improvements that enhance the overall environmental sustainability of the system [31]. This approach provides a holistic understanding of how alternative waste management and treatment strategies influence resource consumption, emissions, and overall environmental performance, offering a scientific basis for decision-making toward sustainable industrial practices.

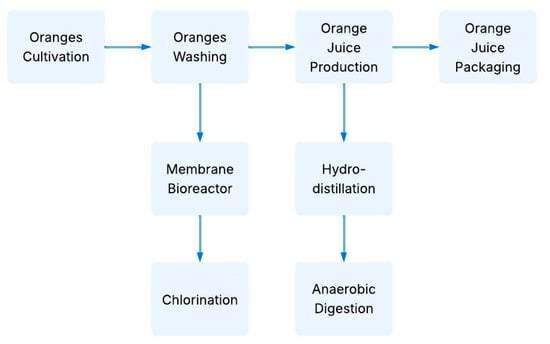

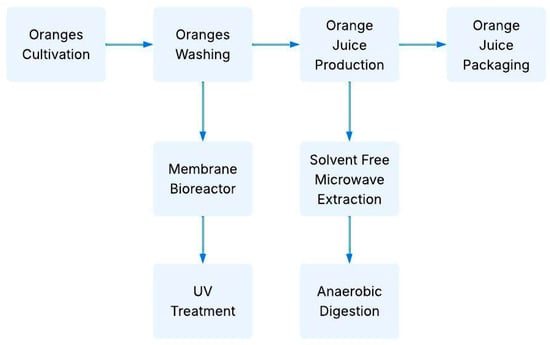

The primary objective of the present work is to evaluate the environmental sustainability of alternative valorization and treatment pathways for the solid wastes and wastewater generated in the orange juice industry. For this purpose, three different scenarios were developed and assessed through LCA. The Baseline scenario represents the current common practice, in which wastes are disposed of in landfills or treated in municipal wastewater treatment plants. Scenario 1 focuses on the valorization of solid wastes through hydrodistillation for essential oil recovery, followed by anaerobic digestion for biomethane production, while wastewater is treated through MBR and chlorination. Scenario 2 adopts a similar valorization approach but utilizes SFME instead of hydrodistillation, combined with thermophilic anaerobic digestion, while wastewater is treated using an MBR followed by UV treatment. The overall goal of the study is to assess and compare the environmental performance of these scenarios, determining whether the integration of innovative solid waste valorization and wastewater treatment technologies within the orange juice industry can reduce its environmental footprint and promote the principles of the circular economy.

2. Materials and Methods

The LCA analysis was performed in accordance with the guidelines set forth by the ISO 14040 recommendations series (14040:2006 and 14044:2006) [30,32]. The methodology for impact assessment utilized in this study was ReCiPe 2016 (H, hierarchist), which primarily aims to convert Life Cycle Inventory results into a limited set of environmental impact scores through the application of characterization factors. The LCA analysis was executed using the LCA for Experts software (version 10.6.2.9, Sphera Solutions GmbH, Stuttgart, Germany).

The two alternative scenarios were simulated using SuperPro Designer (Intelligen, Inc., Freehold, NJ, USA), which enabled the calculation of mass and energy balances for each scenario.

2.1. Goal & Scope

The main goal of the present work is to evaluate the environmental performance of implementing different solid wastes and wastewater valorization and treatment technologies and compare their performance with a baseline scenario representing the current common practice. For this purpose, the environmental impact of the baseline scenario was assessed, and subsequently two different scenarios were evaluated, with each one assessing the performance of different valorization and treatment technologies.

2.2. Functional Unit

The selected functional unit for the LCA analysis is 1 L of packaged orange juice.

2.3. System Boundaries

The system boundaries define which parts of the life cycle are included in the analysis and are critical for the accuracy and completeness of the results. The system boundaries of this LCA analysis include all processes from the cultivation and harvesting of oranges to the treatment of solid and liquid waste resulting from the production of juices (cradle-to-gate). Specifically, the system boundaries include the cultivation of oranges, the processing of oranges to produce orange juice, and the treatment of the generated wastes, including the resulting residues. The product systems of the three different studied scenarios are depicted in Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of Baseline Scenario.

Figure 2.

Flowchart of Scenario 1.

Figure 3.

Flowchart of Scenario 2.

2.4. Data Requirements

Data regarding the production of the orange juice were obtained following communication with a Greek orange juice production company located in Peloponnese region. For the solid waste valorization of Scenarios 1 and 2, input and output flow data were extracted from the simulation models created in SuperPro Designer (Figures S1–S8) while for the wastewater treatment data from accessible references as well as the GABI professional and Ecoinvent databases, specifically referencing the geographical scope of the European Union 28 (EU-28) were utilized. Details regarding the simulation in SuperPro Designer are described in Supplementary Material. Specifically, for the electricity source of the present work it refers to electricity grid mix for Greece.

2.5. Life Cycle Inventory (LCI)

The Life Cycle Inventory (LCI) of the baseline scenario and of Scenarios 1 and 2 are presented in the following Table 1.

Table 1.

Life Cycle Inventory of all studied scenarios.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Scenario

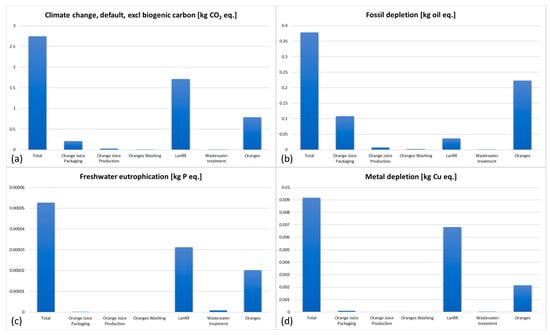

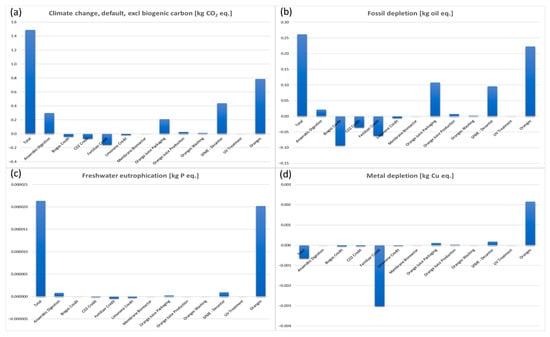

The total environmental effect of the Baseline Scenario, along with the environmental impact of each separate process, is depicted in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Environmental impact of the Baseline Scenario on (a) climate change (kg CO2 eq.), (b) fossil depletion (kg oil eq.), (c) freshwater eutrophication (kg P eq.), and (d) metal depletion (kg Cu eq.).

The Baseline scenario evaluated the environmental impact of the current waste management practices in the juice production industry, where solid waste is landfilled and wastewater is sent to municipal wastewater treatment facilities. This scenario presented the highest environmental burden in all studied indicators compared to the alternative scenarios. The main factors contributing to greenhouse gas emissions (2.75 kg CO2 eq.) are methane emissions from landfilling, along with the consumption of conventional fuels during the cultivation of oranges and the production of juice products [33,34]. Fossil depletion amounts to 0.378 kg oil eq., which is mainly attributed to the use of electrical and thermal energy from conventional sources [35], while freshwater eutrophication (5.27 × 10−5 kg P eq.) is attributed to the run off of nutrients from the landfill disposal and the orange cultivation [36]. Finally, the impacts on metal depletion are relatively low (9.17 × 10−3 kg Cu eq.) and are related to chemical consumption and processing infrastructure.

3.2. Scenario 1

The total environmental effect of Scenario 1, along with the environmental impact of each separate process, is depicted in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Environmental impact of Scenario 1 on (a) climate change (kg CO2 eq.), (b) fossil depletion (kg oil eq.), (c) freshwater eutrophication (kg P eq.), and (d) metal depletion (kg Cu eq.).

Scenario 1 includes hydrodistillation and anaerobic digestion of the generated solid wastes, along with the use of membrane bioreactors and chlorination for wastewater purification. The adoption of these technologies achieves a significant reduction in impacts compared to the baseline scenario, mainly due to the recovery of products that substitute conventional raw materials, such as biogas and organic fertilizer [37]. Greenhouse gas emissions are reduced from 2.75 to 1.76 kg CO2 eq., while freshwater eutrophication is reduced by 46%, reaching 2.84 × 10−5 kg P eq. Metal depletion exhibits a net benefit (−2.25 × 10−3 kg Cu eq.), indicating raw material substitution through recovered products, while mineral resource depletion increases slightly by 11% (0.419 kg oil eq.), due to the considerable consumption of thermal energy during the hydrodistillation process [38].

3.3. Scenario 2

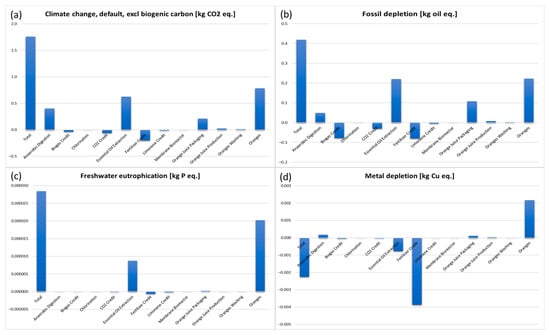

The total environmental effect of Scenario 2, along with the environmental impact of each separate process, is depicted in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Environmental impact of Scenario 2 on (a) climate change (kg CO2 eq.), (b) fossil depletion (kg oil eq.), (c) freshwater eutrophication (kg P eq.), and (d) metal depletion (kg Cu eq.).

Scenario 2 includes solvent-free microwave extraction and anaerobic digestion of solid wastes, along with the implementation of a membrane bioreactor and UV-light treatment for wastewater purification. Overall, Scenario 2 exhibits the best results in terms of environmental performance. Although electricity consumption is increased, the benefits of higher essential oil recovery (122 kg vs. 86.5 kg in Scenario 1), higher biogas production (670 kg vs. 558 kg), and the use of UV disinfection instead of chlorine outweigh the additional energy requirements [37,39]. Additionally, it is worth mentioning that chlorination, if not performed accurately, may lead to the generation of harmful by-products, whereas in UV disinfection this risk is eliminated, hence further solidifying the benefits of UV as an efficient wastewater treatment method [28,40]. CO2 emissions are further reduced to 1.49 kg CO2 eq. (−46% compared to baseline and −15% compared to Scenario 1), Fossil depletion is limited to 0.262 kg oil eq. (−31%), while freshwater eutrophication reaches 2.14 × 10−5 kg P-eq., resulting in 59% reduction compared to the Baseline Scenario. Finally, metal depletion is almost zero (−6.51 × 10−4 kg Cu-eq.), reflecting a net environmental benefit.

3.4. Comparison

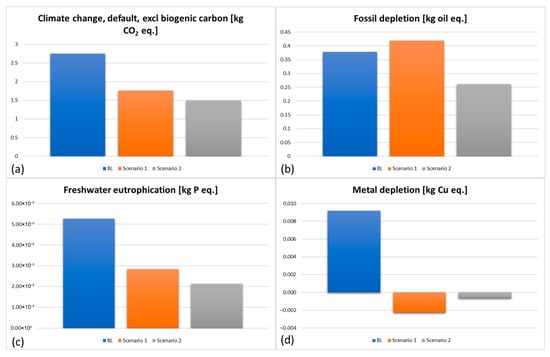

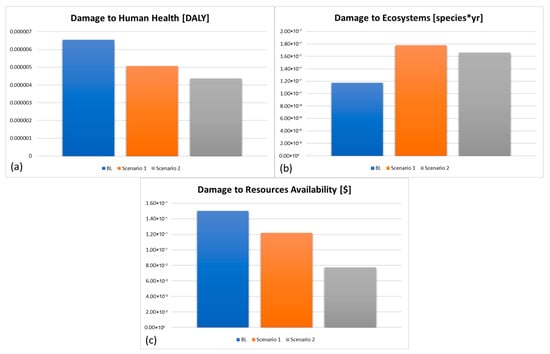

A direct comparison regarding the environmental impact of the three studied scenarios is presented in the following Figure 7 and Figure 8.

Figure 7.

Environmental impact of the different studied Scenarios on (a) climate change (kg CO2 eq.), (b) fossil depletion (kg oil eq.), (c) freshwater eutrophication (kg P eq.), and (d) metal depletion (kg Cu eq.).

Figure 8.

Comparison of the ReCiPe endpoints (a) damage to human health (DALY), (b) damage to ecosystems (species*yr), and (c) damage to resources availability ($) of the three studied Scenarios.

A direct comparison of the three scenarios shows that both alternative scenarios outperform the baseline scenario in most of the studied environmental categories (climate change, fossil resource depletion, freshwater eutrophication), demonstrating that the recovery of energy and high–value-added materials significantly improves the environmental footprint of the juice production industry. Additionally, Scenario 2 consistently exhibits the best overall performance. Increased essential oil recovery yields, higher biogas production, and the avoidance of chlorinated disinfection are the main factors contributing to its improved environmental performance. At the same time, Scenario 1 achieves a substantial reduction in impacts compared to the baseline scenario; however, the high energy requirements of hydrodistillation and the use of chlorination limit its net environmental benefit.

Regarding the Baseline scenario, the total damage to human health reaches 6.54 × 10−6 DALYs, to ecosystems 1.17 × 10−7 species*yr and to resources availability 0.150 $, confirming that this scenario is the one with the heaviest environmental burden.

On the other hand, Scenario 1 reduces the damage to human health to 5.06 × 10−6 DALYs (−22.6%) and to resources availability to 0.122 $ (−18.7%), while a slight increase in damage to ecosystems is observed (1.78 × 10−7 species*yr), mostly attributed to the use of sodium hypochlorite and the methane emissions. Additionally, it is worth noting that although in the midpoint category of fossil depletion an increase in Scenario 1 compared to the baseline is observed, the value of the endpoint regarding resources availability is decreased compared to the Baseline scenario. This observation is explained, due to the fact that the endpoint indicator takes into account results regarding both fossil and metal depletion, in which a significant decrease in the midpoint indicator is observed [41]. Despite the increased energy requirements of hydrodistillation and the use of sodium hypochlorite, its overall environmental performance is clearly improved compared to the conventional system.

Accordingly, in Scenario 2 the damage to human health is further reduced to 4.37 × 10−6 DALY (−33%) and to resources to 0.077 $ (−49%), while the damage to ecosystems is lower compared to Scenario 1 (1.66 × 10−7 species*yr). Overall, this scenario achieves the greatest improvement, demonstrating that the combination of SFME, thermophilic digestion and UV disinfection technologies leads to the greatest reduction in emissions and resource consumption, achieving the highest net environmental benefit.

4. Discussion

Life Cycle Assessment shows that the combination of solid waste valorization (through essential oil extraction and anaerobic digestion) with novel on-site wastewater treatment can significantly reduce the environmental footprint of the juice industry. This result aligns with recent studies indicating that the recovery of products and energy from food waste leads to substantial emission reductions and resource savings. According to international literature, similar strategies in the beverage and food industries have achieved emission reductions of up to 40–50%, which is consistent with the findings of the present study.

The comparison of the two alternative scenarios demonstrates that the energy efficiency of the extraction process and the choice of disinfection technology can be determining factors in optimizing the environmental performance of the studied system. Hydrodistillation is particularly energy-intensive and limits the overall benefits of Scenario 1, while the SFME method achieves higher essential oil recovery with a lower environmental burden. At the same time, replacing chlorination with UV disinfection significantly reduces toxicological impacts and dependence on chemical products. The thermophilic anaerobic digestion applied in Scenario 2 also provides higher energy efficiency, increasing biogas production and, consequently, fossil energy substitution.

On a practical level, the findings of the present work indicate that juice industries can substantially reduce their environmental footprint by investing in energy-efficient extraction technologies, optimized anaerobic digestion systems with control of inhibitory substances (such as d-limonene), and wastewater treatment lines that avoid the use of chlorine. The proposed technological options are compatible with circular economy principles, enhancing the overall sustainability of the sector.

The main limitations of the study concern the use of simulated data (SuperPro Designer), the uncertainty of the database parameters (EU-28), the absence of economic analysis and the lack of quantitative sensitivity analysis. The investigation of these parameters in future studies, as well as the pilot implementation of the scenarios on an industrial scale, will provide a stronger basis for decision-making and documentation of the sustainability of waste recovery systems.

To reduce the uncertainty associated with the simulation-based results and to support future industrial implementation, subsequent studies should incorporate targeted experimental work. Specifically, direct laboratory comparisons of hydrodistillation and solvent-free microwave extraction using identical batches of orange waste are necessary to validate essential oil yields, energy requirements and oil composition. Likewise, Biochemical Methane Potential (BMP) assays and continuous anaerobic digestion trials would enable more accurate determination of methane production, process stability and degradation efficiency. Furthermore, comprehensive characterization of the resulting digestate—such as nutrient content, heavy metals, pathogen indicators and phytotoxicity—would allow a more reliable estimation of its fertilizer substitution potential. Conducting these experiments in future research will significantly strengthen the robustness and reliability of the LCA outcomes.

5. Conclusions

The primary objective of the present work was to evaluate the environmental sustainability of alternative valorization and treatment pathways for the solid wastes and wastewater generated in the orange juice industry. According to the obtained results, the integrated valorization of solid wastes and the treatment of wastewater derived from the orange juice production process can substantially reduce the environmental footprint of the industry. Both alternative strategies (Scenarios 1 and 2) perform significantly better than the baseline scenario, which involves landfilling of solid wastes and conventional wastewater treatment at a municipal facility.

Scenario 2, which combines solvent-free microwave extraction of essential oil, thermophilic anaerobic digestion, membrane bioreactor treatment, and ultraviolet disinfection, presents the highest environmental performance. Specifically, it achieves a greenhouse gas emission reduction of approximately 46%, while Scenario 1 results in a reduction of approximately 36%.

The main mechanisms contributing to the improvement of environmental performance include the substitution of fossil energy through the utilization of the produced biogas, the replacement of inorganic fertilizers with the organic by-product of anaerobic digestion (known as digestate), as well as the recovery of high-value essential oils. The selection of technologies that enhance the efficiency of by-product streams and limit the use of chemicals leads to significant environmental benefits. The findings of the study are in line with recent international research that highlights the role of circular economy strategies in reducing emissions and in the sustainable management of food waste.

The application of the combination of microwave extraction and thermophilic anaerobic digestion on an industrial scale can significantly contribute to promoting the circular economy of the sector, transforming waste into valuable energy and material resources. Further experimental investigation of the performances, economic evaluation and sensitivity analysis of the system parameters is proposed, in order to enhance the reliability of the results and facilitate the establishment of such technologies in the food industry.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/waste3040042/s1, Figure S1: Composition of solid wastes inserted in SuperPro Designer. Figure S2: Flowchart of Scenario 1, Section 1. Figure S3: Flowchart of Scenario 1, Section 2. Figure S4: Simplified chemical reactions of anaerobic digestion. Figure S5: Sequence of reactions in SuperPro Designer. Figure S6: Operating conditions of the adsorption bed. Figure S7: Flowchart of Scenario 1 in SuperPro Designer. Figure S8: Flowchart of Scenario 2 in SuperPro Designer.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.D., T.K. and A.K.; methodology, A.K.; software, F.D., T.K. and A.K.; validation, F.D. and T.K.; formal analysis, F.D., T.K. and A.K.; investigation, A.K.; resources, M.K.; data curation, F.D., T.K. and A.K.; writing—original draft preparation, F.D.; writing—review and editing, T.K.; visualization, F.D.; supervision, M.K.; project administration, M.K.; funding acquisition, M.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article and/or the Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| LCA | Life Cycle Assessment |

| SFME | Solvent Free Microwave Extraction |

References

- Zhong, G.; Nicolosi, E. Citrus Origin, Diffusion, and Economic Importance. In The Citrus Genome; Alessandra, G., La Malfa, S., Deng, Z., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 5–21. ISBN 978-3-030-15308-3. [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz, D.L.; Batuecas, E.; Orrego, C.E.; Rodríguez, L.J.; Camelin, E.; Fino, D. Sustainable Management of Peel Waste in the Small-Scale Orange Juice Industries: A Colombian Case Study. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 265, 121587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manakas, P.; Balafoutis, A.T.; Kottaridi, C.; Vlysidis, A. Sustainability Assessment of Orange Peel Waste Valorization Pathways from Juice Industries. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2025, 15, 6525–6544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Torre, I.; Martin-Dominguez, V.; Acedos, M.G.; Esteban, J.; Santos, V.E.; Ladero, M. Utilisation/Upgrading of Orange Peel Waste from a Biological Biorefinery Perspective. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 103, 5975–5991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocker, R.; Silva, E.K. Sustainable Pectin-Based Film for Carrying Phenolic Compounds and Essential Oil from Citrus sinensis Peel Waste. Food Biosci. 2024, 61, 104526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senit, J.J.; Velasco, D.; Gomez Manrique, A.; Sanchez-Barba, M.; Toledo, J.M.; Santos, V.E.; Garcia-Ochoa, F.; Yustos, P.; Ladero, M. Orange Peel Waste Upstream Integrated Processing to Terpenes, Phenolics, Pectin and Monosaccharides: Optimization Approaches. Ind. Crops Prod. 2019, 134, 370–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerva, I.; Remmas, N.; Melidis, P.; Tsiamis, G.; Ntougias, S. Microbial Succession and Identification of Effective Indigenous Pectinolytic Yeasts From Orange Juice Processing Wastewater. Waste Biomass Valorization 2021, 12, 4885–4899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viuda-Martos, M.; Fernandez-Lopez, J.; Sayas-Barbera, E.; Sendra, E.; Perez-Alvarez, J.A. Physicochemical Characterization of the Orange Juice Waste Water of a Citrus By-Product. J. Food Process Preserv. 2011, 35, 264–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christofi, A.; Tsipiras, D.; Malamis, D.; Moustakas, K.; Mai, S.; Barampouti, E.M. Biofuels Production from Orange Juice Industrial Waste within a Circular Economy Vision. J. Water Process Eng. 2022, 49, 103028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Dong, H.; Wang, Y.; Men, J.; Wang, J.; Zhao, X.; Zou, S. Valorization of Alkali–Thermal Activated Red Mud for High-Performance Geopolymer: Performance Evaluation and Environmental Effects. Buildings 2025, 15, 2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Dong, H.; Zhao, X.; Wang, K.; Gao, X. Utilisation of Bayer Red Mud for High-Performance Geopolymer: Competitive Roles of Different Activators. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 23, e05047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavahian, M.; Chu, Y.-H.; Mousavi Khaneghah, A. Recent Advances in Orange Oil Extraction: An Opportunity for the Valorisation of Orange Peel Waste a Review. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 54, 925–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustamante, J.; van Stempvoort, S.; García-Gallarreta, M.; Houghton, J.A.; Briers, H.K.; Budarin, V.L.; Matharu, A.S.; Clark, J.H. Microwave Assisted Hydro-Distillation of Essential Oils from Wet Citrus Peel Waste. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 137, 598–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paini, J.; Midolo, G.; Valenti, F.; Ottolina, G. One-Pot Combined Hydrodistillation of Industrial Orange Peel Waste for Essential Oils and Pectin Recovery: A Multi-Objective Optimization Study. Sustainability 2025, 17, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heydari, M.; Rostami, O.; Mohammadi, R.; Banavi, P.; Farhoodi, M.; Sarlak, Z.; Rouhi, M. Hydrodistillation Ultrasound-Assisted Green Extraction of Essential Oil from Bitter Orange Peel Wastes: Optimization for Quantitative, Phenolic, and Antioxidant Properties. J. Food Process Preserv. 2021, 45, e15585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo, A.R.T.S.; Périno, S.; Fernandez, X.; Cunha, C.; Rodrigues, M.; Ribeiro, M.P.; Jordao, L.; Silva, L.A.; Rodilla, J.; Coutinho, P.; et al. Solvent-Free Microwave Extraction of Thymus mastichina Essential Oil: Influence on Their Chemical Composition and on the Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Activities. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benassi, L.; Alessandri, I.; Vassalini, I. Assessing Green Methods for Pectin Extraction from Waste Orange Peels. Molecules 2021, 26, 1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jebreen, A.M.Y.; Sahni, O. Areesha Citrus Peel Waste Management of Oranges. In Valorization of Citrus Food Waste; Chauhan, A., Islam, F., Imran, A., Singh Aswal, J., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 31–42. ISBN 978-3-031-77999-2. [Google Scholar]

- Anticona, M.; Blesa, J.; Frigola, A.; Esteve, M.J. High Biological Value Compounds Extraction from Citrus Waste with Non-Conventional Methods. Foods 2020, 9, 811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiwari, B.K. Ultrasound: A Clean, Green Extraction Technology. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2015, 71, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayramoglu, B.; Sahin, S.; Sumnu, G. Solvent-Free Microwave Extraction of Essential Oil from Oregano. J. Food Eng. 2008, 88, 535–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukroufa, M.; Boutekedjiret, C.; Petigny, L.; Rakotomanomana, N.; Chemat, F. Bio-Refinery of Orange Peels Waste: A New Concept Based on Integrated Green and Solvent Free Extraction Processes Using Ultrasound and Microwave Techniques to Obtain Essential Oil, Polyphenols and Pectin. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2015, 24, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Fabiano-Tixier, A.S.; Vian, M.A.; Chemat, F. Solvent-Free Microwave Extraction of Bioactive Compounds Provides a Tool for Green Analytical Chemistry. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2013, 47, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, G.M.M.; Uddin, M.J.; Islam, M.T.; Barmon, J.; Dey, S.S.; Chandra Ghos, B.; Al Bashera, M.; Karmaker, P.; Karmakar, A.; Rahman, T.; et al. Solvent-Free Microwave Extraction and Hydrodistillation Extraction of Essential Oils from Syzygium Cumini Leaves: Comparative Analysis of Chemical Constituents, in Vitro and in Silico Approaches. LWT 2025, 228, 118074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrò, P.S.; Paone, E.; Komilis, D. Strategies for the Sustainable Management of Orange Peel Waste through Anaerobic Digestion. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 212, 462–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokaya, B.; Kerroum, D.; Hayat, Z.; Panico, A.; Ouafa, A.; Pirozzi, F. Biogas Production by an Anaerobic Digestion Process from Orange Peel Waste and Its Improvement by Limonene Leaching: Investigation of H2O2 Pre-Treatment Effect. Energy Sources Part A Recovery Util. Environ. Eff. 2024, 46, 2704–2712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Asheh, S.; Bagheri, M.; Aidan, A. Membrane Bioreactor for Wastewater Treatment: A Review. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2021, 4, 100109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kekes, T.; Tzia, C.; Kolliopoulos, G. Drinking and Natural Mineral Water: Treatment and Quality–Safety Assurance. Water 2023, 15, 2325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Li, M.; Li, W.; Qiang, Z. A Review of the Fluence Determination Methods for UV Reactors: Ensuring the Reliability of UV Disinfection. Chemosphere 2022, 286, 131488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drosou, F.; Kekes, T.; Boukouvalas, C. Life Cycle Assessment of the Canned Fruits Industry: Sustainability through Waste Valorization and Implementation of Innovative Techniques. AgriEngineering 2023, 5, 395–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askham, C. REACH and LCA—Methodological Approaches and Challenges. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2012, 17, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Organization for Standardization [ISO]. ISO 14040:2006 Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment—Principles and Framework. 2006. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/37456.html (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Cabot, M.I.; Lado, J.; Sanjuán, N. Peeling the Orange: Delving into Life Cycle Indicators for Water Footprint, Ecosystem Services, and Biodiversity for Orange Cultivation in Uruguay. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2025, 54, 261–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Fang, M.; Lou, Z.; He, H.; Guo, Y.; Pi, X.; Wang, Y.; Yin, K.; Fei, X. Methane Emissions from Landfills Differentially Underestimated Worldwide. Nat. Sustain. 2024, 7, 496–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, F.; Felgueiras, C.; Smitkova, M.; Caetano, N. Analysis of Fossil Fuel Energy Consumption and Environmental Impacts in European Countries. Energies 2019, 12, 964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essien, J.P.; Ikpe, D.I.; Inam, E.D.; Okon, A.O.; Ebong, G.A.; Benson, N.U. Occurrence and Spatial Distribution of Heavy Metals in Landfill Leachates and Impacted Freshwater Ecosystem: An Environmental and Human Health Threat. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0263279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamparas, M. 1—The Role of Resource Recovery Technologies in Reducing the Demand of Fossil Fuels and Conventional Fossil-Based Mineral Fertilizers. In Low Carbon Energy Technologies in Sustainable Energy Systems; Kyriakopoulos, G.L., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; pp. 3–24. ISBN 978-0-12-822897-5. [Google Scholar]

- Gavahian, M.; Farahnaky, A.; Javidnia, K.; Majzoobi, M. Comparison of Ohmic-Assisted Hydrodistillation with Traditional Hydrodistillation for the Extraction of Essential Oils from Thymus vulgaris L. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2012, 14, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukouvalas, C.; Kekes, T.; Oikonomopoulou, V.; Krokida, M. Life Cycle Assessment of Energy Production from Solid Waste Valorization and Wastewater Purification: A Case Study of Meat Processing Industry. Energies 2024, 17, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collivignarelli, M.C.; Abbà, A.; Miino, M.C.; Caccamo, F.M.; Torretta, V.; Rada, E.C.; Sorlini, S. Disinfection of Wastewater by UV-Based Treatment for Reuse in a Circular Economy Perspective. Where Are We At? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdivia, S.; Backes, J.G.; Traverso, M.; Sonnemann, G.; Cucurachi, S.; Guinée, J.B.; Schaubroeck, T.; Finkbeiner, M.; Leroy-Parmentier, N.; Ugaya, C.; et al. Principles for the Application of Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2021, 26, 1900–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).