Abstract

Credit card fraud detection remains a critical challenge for financial institutions, particularly due to extreme class imbalance and the continuously evolving nature of fraudulent behavior. This study investigates two complementary approaches: anomaly detection based on multivariate normal distribution and deep reinforcement learning using a Deep Q-Network. While anomaly detection effectively identifies deviations from normal transaction patterns, its static nature limits adaptability in real-time systems. In contrast, the DQN reinforcement learning model continuously learns from every transaction, autonomously adapting to emerging fraud strategies. Experimental results demonstrate that, although initial performance metrics of the DQN are modest compared to anomaly detection, its capacity for online learning and policy refinement enables long-term improvement and operational scalability. This work highlights reinforcement learning as a highly promising paradigm for dynamic, high-volume fraud detection, capable of evolving with the environment and achieving near-optimal detection rates over time.

Keywords:

credit card fraud detection; reinforcement learning; Deep Q-Network; anomaly detection; imbalanced data; online learning; adaptive systems; transaction security JEL Classification:

G21; G28; C45; C38

1. Introduction

Financial fraud detection represents one of the most pressing challenges in the modern digital economy, with serious consequences for financial institutions, businesses, and consumers worldwide. Moreover, the rapid digitization of financial services has created new opportunities for fraud, making it essential to develop advanced detection systems capable of identifying malicious transactions in real time.

Financial fraud can manifest itself in various forms, including credit card fraud, identity theft, money laundering, insurance fraud, and payment system exploitation. Among these, credit card fraud has emerged as one of the most common and financially damaging types, with global losses projected to reach $49.32 billion by 2030 [1,2].

In addition, the field of credit card fraud detection has evolved considerably from traditional rule-based systems to sophisticated artificial intelligence (AI) techniques. Early detection methods relied on static rules and threshold-based alerts, which often proved insufficient against adaptive fraudsters constantly developing new evasion strategies [3]. In this way, the adoption of machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) methods has revolutionized fraud detection, allowing systems to learn complex patterns from historical transaction data and identify subtle anomalies indicative of fraudulent activity [4,5].

Furthermore, Hafez et al. [6] conducted a systematic review of AI-based techniques for credit card fraud detection, highlighting the effectiveness of ML, DL, and meta-heuristic optimization algorithms. Their analysis showed that integrated AI approaches substantially improve the detection of different types of fraud. However, limitations persist in the ML and DL models, necessitating continuous development to keep pace with evolving fraudulent behaviors.

Ensemble methods have also shown significant promise. Alkhozae et al. [7] proposed an explainable credit card fraud detection model that combines multiple classifiers, including XGBoost, LightGBM, Random Forest, and MLP. This framework achieved remarkable performance with 99.86% precision, 96.36% precision, and 80.59% recall, while incorporating SHAP-based explainability and reinforcement learning for dynamic threshold tuning. As a result, the system successfully blocked 91% of fraudulent transactions while maintaining a 7.8% false-positive rate.

Moreover, the issue of class imbalance has been extensively addressed through sampling techniques. Gutiérrez-Gallego et al. [8] introduced a Balanced Underbagging Ensemble approach for highly imbalanced datasets common in financial applications. Their method outperformed 100 combinations of oversampling and undersampling techniques, demonstrating superior recall for both majority and minority classes across different ML algorithms.

In addition, evolutionary algorithms have been applied to optimize imbalanced learning. Safder et al. [9] utilized Genetic Algorithms (GA) for synthetic data generation, surpassing methods such as SMOTE, ADASYN, GAN and VAE in multiple metrics, including accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, ROC-AUC and AP curve.

Deep learning architectures have further advanced fraud detection capabilities. Salem et al. [10] proposed the local search-based binary Griffon vulture optimization algorithm (BGVOA-LS), integrating optimized feature selection with ML to improve accuracy. Their approach reduced the feature count by 67% while achieving up to 99.8% accuracy. Similarly, generative models have been applied to address data imbalance. Pavan et al. [11] employed adversarial ML based on chaotic variational autoencoders, while Ab Yajid et al. [12] developed a hybrid Big Bang-Big Crunch with cuckoo search (HB3C2S) for feature selection combined with DCNN, achieving accuracy up to 95.61%.

Unsupervised learning approaches are increasingly important for detecting new fraud patterns. Kennedy et al. [13] combined SHAP-based feature selection with autoencoder-generated labels, significantly improving label quality and model performance. Walauskis et al. [14] extended this work using ensemble unsupervised methods with percentile thresholding, effectively overcoming the challenge of severely unbalanced data labeling. Moreover, Darwish et al. [15] utilized Artificial Bee Colony (ABC)-based sampling to generate realistic synthetic fraud samples, improving model learning without biasing towards non-fraudulent transactions. Their method improved detection accuracy while reducing false alarms, improving the reliability of the system.

Explainable AI (XAI) has also gained attention due to the black-box nature of complex models. Vadlamudi et al. [16] explored the explanations of LIME and SHAP along with transformer-based models such as BERT, XLNet, and RoBERTa. Their CheMO multi-algorithm optimization approach achieved 97–98% accuracy while providing interpretable decisions. Similarly, Hirnschall [1] proposed semi-supervised Bayesian GANs with logarithmic signs, improving uncertainty-aware fraud detection and improving trustworthiness. In addition, Sundaravadivel et al. [17] demonstrated that the Adaboost and Decision Tree models outperformed ANN in predicting credit card defaults, achieving 82% accuracy versus 78%.

Hybrid and metaheuristic methods have further strengthened detection capabilities. Alsowail [18] combined the random light Gradient-based CatBoost Ensemble with the Enhanced Gold Rush Algorithm, attaining 99.1% accuracy. Priatna et al. [19] proposed a hybrid Autoencoder-Transformer framework for fraud in e-commerce, surpassing conventional DNN, LSTM, and RNN models in precision, precision, recall, F1-score, and AUC. Moreover, metaheuristic optimization has been applied for feature selection and hyperparameter tuning. Atban et al. [20] demonstrated that the PSO + VQC combinations achieved 94.54% precision, while Abadlia et al. [21] and Chakraborty [22] showed the effectiveness of particle swarm and sand cat swarm optimization techniques for stacked autoencoders and CNN-based detection, respectively.

Real-time and scalable architectures have also been explored. Madhavappa et al. [23] employed an optimized CNN-RNN framework for the detection of online transactions. Federated learning approaches have addressed privacy concerns while maintaining high accuracy. For example, Damanik et al. [24] proposed explainable and balanced federated learning with neural networks, while Xia et al. [25] introduced FinGraphFL, which combines graph-based learning and federated principles. In addition, El Hlouli et al. [26] proposed a fully connected deep network that combines Autoencoder and MLP architectures, achieving superior evaluation metrics in multiple unbalanced credit datasets.

Recent advances in advanced neural architectures have also improved detection performance. Shabiya et al. [27] proposed LSO-RVAE, achieving 99.80% accuracy, 100% recall, and an AUC of 0.998. Chugh et al. [28] integrated Firefly Optimization with logistic regression, improving MCC by 34.94%. Furthermore, Adejoh et al. [29] combined autoencoders, self-organizing maps, and RBMs with adaptive reconstruction thresholds, achieving high accuracy and F1-scores. In addition, Ahmad et al. [30] utilized Tomek Links undersampling to enhance the balance of the data set and improve ANN performance.

Comparative analyzes provide valuable information on algorithmic performance. Tayebi et al. [31] demonstrated that XGBoost with Bayesian optimization outperformed other ML models with high detection rates accuracy and high AUC. Similarly, Andrade-Arenas et al. [32] showed that Random Forest and XGBoost consistently outperformed alternatives using SMOTE to minimize imbalance. In addition, Theodorakopoulos et al. [33] implemented distributed big data-driven ML using PySpark, XGBoost, and CatBoost, achieving scalable real-time detection, while Akouhar et al. [34] proposed Kolmogorov-Arnold networks driven by dynamic sampling to improve adaptability across benchmark datasets.

Unsupervised and anomaly detection techniques are increasingly relevant. Karnavou et al. [35] employed Isolation Forest, one-class SVM, and deep autoencoders for unsupervised detection, while John Berkmans et al. [36] used heterogeneous multi-view graph neural networks, demonstrating substantial gains in accuracy. Additionally, Hancock et al. [37] combined SHAP with one-class classifiers for efficient feature selection in highly imbalanced data.

Despite these advances, significant limitations remain. Models often struggle with extreme class imbalance, the continuous evolution of fraud patterns, privacy restrictions, and limited interpretability. Hayat et al. [38] highlighted that evaluation flaws can exaggerate model performance, while Feng et al. [39] addressed imbalance and missing values with Gradient Boosted Decision Trees. Similarly, Chen et al. [40] integrated LSTM with logistic regression to capture spatiotemporal correlations, improving predictive performance.

This study addresses three key research questions: Can Deep Q-Networks effectively learn fraud detection policies from extremely imbalanced transaction data? How does the adaptive, sequential learning of DQN compare to static anomaly detection in fraud detection performance? And is reinforcement learning a viable paradigm for real-time, adaptive fraud detection in dynamic financial environments?

To answer these, we propose a reinforcement learning agent-based framework for credit card fraud detection, which builds a predictive model, primarily using Deep Reinforcement Learning, to classify transactions as either fraudulent or non-fraudulent. The model relies on a small set of easily available transactional features, including the transaction ID, date and time, customer ID, terminal ID, transaction amount, and the fraud label indicating legitimate or fraudulent transactions. In this way, the RL agent can continuously learn from transaction streams, adapt to emerging fraud patterns, and optimize long-term detection strategies. Moreover, because it only requires basic transactional data that are automatically generated during normal operations, the framework is practical, scalable, and privacy-preserving, enabling financial institutions to deploy adaptive fraud detection without extensive data collection or additional infrastructure.

In summary, the main contributions of this paper are threefold: (1) We propose a reinforcement learning-based framework using Deep Q-Networks for adaptive fraud detection in highly imbalanced transaction data. (2) We provide a comparative analysis between anomaly detection and reinforcement learning, highlighting the long-term learning advantages of DQN in dynamic environments. (3) We demonstrate through structured experiments that DQN can achieve sustained performance improvement over time, making it suitable for real-time deployment in systems such as ATM networks.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Problem Statement

The main task of this study is to perform a binary classification to identify whether each transaction is legitimate (0) or fraudulent (1). The primary difficulty lies in the strong imbalance between the two classes, which tends to bias models toward predicting the majority class. As a result, the model may not detect rare fraudulent cases. In addition, fraud patterns can evolve, requiring models that are capable of continuous learning and adaptation.

To address these challenges, two modeling strategies are proposed. These approaches were selected based on their demonstrated effectiveness in the literature: anomaly detection for handling extreme class imbalance [8,13], and reinforcement learning for adapting to evolving fraud patterns [6,25].

The first strategy is anomaly detection, also known as outlier detection. This approach is particularly effective for unbalanced data. Instead of directly distinguishing between legitimate and fraudulent transactions, the model learns the pattern of normal transactions. Any transaction that deviates significantly from this learned behavior is flagged as a potential fraud. This makes the method suitable when fraudulent examples are rare and diverse.

The second strategy is reinforcement learning (RL). In this framework, fraud detection is treated as an interactive process between an agent (the detection model) and an environment (the stream of transactions). The agent makes decisions such as approving or flagging transactions, and receives rewards for correct decisions and penalties for incorrect ones. Over time, the agent learns an optimal decision policy that adapts to changing and new fraud behaviors. This continuous learning capability makes RL promising for dynamic financial systems.

2.2. Data

2.2.1. Data Description

The data used in this study is the Kaggle “Credit Card Fraud Detection” data set, which includes transactions made by European cardholders [41]. This dataset has been extensively studied in the fraud detection literature, with numerous works documenting its characteristics and preprocessing requirements [17,33]. This benchmark dataset does not contain explicit temporal sequencing information.

It contains 284,807 transactions, among which only 492 are fraudulent, representing about 0.172% of the total. This highlights the severe imbalance in the class distribution.

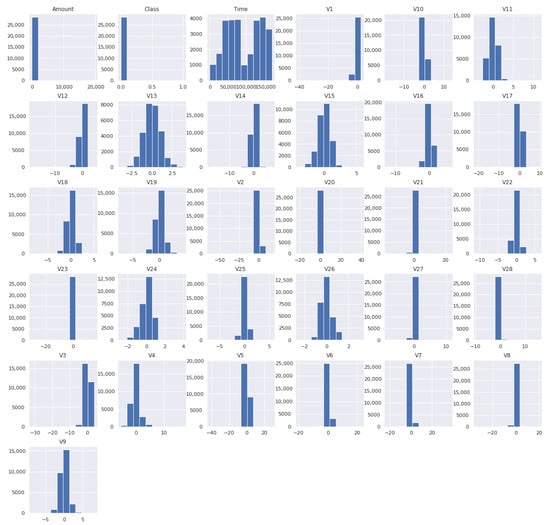

The data set contains 31 features: transaction time, the transaction amount, class label, and 28 anonymized features (V1–V28) that were obtained using principal component analysis (PCA). The PCA transformation was applied to protect confidentiality and reduce dimensionality, resulting in numerical features that capture most of the variance in the original data. The distribution of these variables is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Distribution of the PCA-derived features in the Kaggle credit card fraud dataset.

2.2.2. Data Visualization

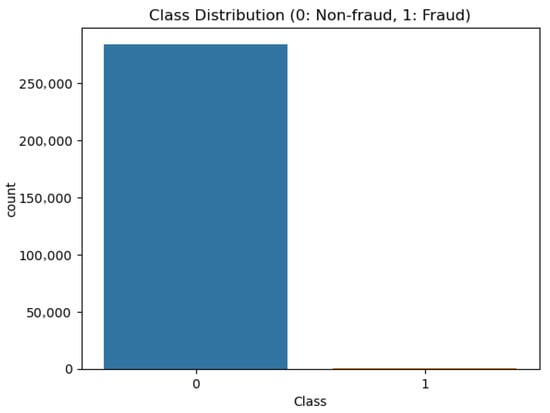

A preliminary investigation was conducted to ensure data quality and consistency. Duplicate transactions were identified and removed, reducing the data to 283,726 entries. No missing values were found, which simplifies preprocessing. After cleaning, the data contained 283,253 legitimate transactions and 473 fraudulent transactions.

The imbalance between classes is visually represented in Figure 2. Fraudulent transactions represent only a very small portion of the dataset.

Figure 2.

Class distribution showing legitimate (0) vs. fraudulent (1) transactions.

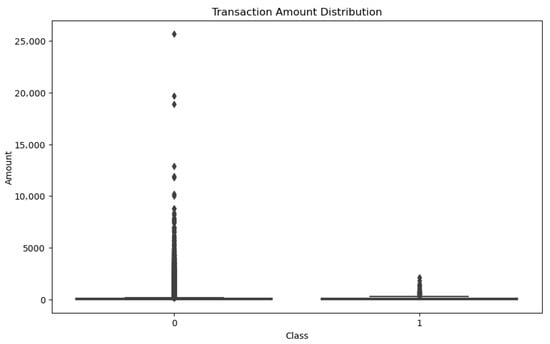

On the other hand, understanding the distribution of transaction amounts is important, as fraudulent transactions often exhibit distinctive patterns of monetary amounts. Figure 3 presents this distribution.

Figure 3.

Transaction amount distributions for legitimate (0) and fraudulent (1) classes.

Fraudulent transactions may involve either small amounts—used to test the validity of the card—or larger amounts aimed at maximizing illegal profit before the card is blocked. Recognizing such differences is essential for designing features that can help models detect these patterns effectively.

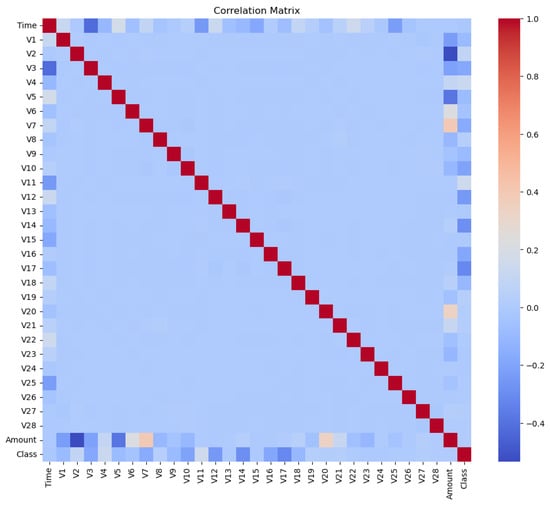

In addition, a correlation analysis was performed to identify the features that are most closely related to the target variable.

The correlation matrix in Figure 4 illustrates the relationships between all features, including the target.

Figure 4.

Correlation matrix of all 31 features, including the 28 PCA components.

The correlation heat map reveals that several PCA-derived features have notable relationships with fraud. Components such as V14, V17, V12, and V10 typically show strong negative correlations, indicating that smaller values in these components are associated with a higher probability of fraud. In contrast, components such as V11, V4, V2, and V7 show positive correlations with fraudulent activity.

The features Time and Amount have weak correlations with the target. Time shows minimal influence, while Amount may have a slight positive relationship, suggesting that fraudulent transactions might differ in their typical value distribution.

Because the V-features are uncorrelated due to the PCA transformation, they provide a suitable input space for machine learning algorithms. This property reduces redundancy and helps models learn effectively from independent features.

Technically speaking, correlation analysis is therefore a critical step in identifying which variables most contribute to distinguishing fraudulent transactions. These features will be prioritized in future modeling to enhance both accuracy and interpretability.

In this analysis, a feature was considered to have a “significant linear correlation” with the target if its absolute correlation coefficient . This threshold is commonly used in feature selection for fraud detection to identify meaningful relationships while avoiding noise [17]. Features such as V14, V17, and V11 met this criterion and were prioritized in subsequent modeling.

As a synthesis, this exploratory data analysis has quantitatively and visually confirmed the profound class imbalance that defines the fraud detection problem. More importantly, it has successfully identified a subset of principal components (notably V2, V4, V7, V11, V12, V14, and V17) that exhibit significant linear correlations with the target variable. These features are strong candidates for being the primary drivers in our subsequent classification models. The insights derived from the transaction amount distribution and these key correlations provide a critical, empirically grounded foundation for the next phase of this study: building and evaluating predictive models that are specifically designed to be robust to imbalance and capable of leveraging these discriminative signals for accurate fraud identification.

2.3. Models and Methodology

In this study, we used two different machine learning approaches. Each method solves the problem differently.

The first model is the anomaly Detection Model. This model works well with unbalanced data. It learns what normal transactions look like and flags transactions that are very different as potential fraud. However, this model needs to be retrained when new data arrives, which can be impractical for credit card systems that process transactions continuously.

The second model is a Reinforcement Learning Model (DQN). This model can learn and adapt automatically over time. Although it is harder to train at first, it can improve itself with each new transaction without needing manual retraining. This makes it suitable for dynamic environments like fraud detection.

2.3.1. Anomaly Detection Using Multivariate Normal Distribution

The anomaly detection algorithm aims to identify transactions that deviate significantly from normal behavior. In our case, we model the normal transaction patterns using the Multivariate Normal Distribution, which captures both the mean behavior and the covariance structure of multiple features simultaneously.

The probability density function for a vector of characteristic d of dimensionality is given by the following:

where:

- is the feature vector that represents a transaction,

- is the mean vector of the normal transactions,

- is the covariance matrix that captures the correlations of features,

- d is the number of selected features.

For computational simplicity and interpretability, we assume that the features are statistically independent. Under this assumption, the joint probability density function is factorized into a product of univariate normal distributions:

where and denote the mean and standard deviation of the j-th feature, respectively.

Due to the extreme class imbalance in fraud detection, the model is trained exclusively on normal transactions. and the dataset partitioned as follows:

Based on prior feature correlation and importance analysis, we selected the following features for the model: [‘V4’, ‘V11’, ‘V12’, ‘V14’, ‘V16’, ‘V17’, ‘V18’, ‘V19’, ‘Time’].

The developed anomaly detection algorithm operates in three main steps as mentioned in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1 Anomaly Detection Process |

|

2.3.2. Deep Q-Network for Reinforcement Learning

In this approach, fraud detection is formulated as a sequential decision-making problem under the Reinforcement Learning paradigm.

The agent interacts with an environment that represents the transaction data set and learns to distinguish between normal and fraudulent transactions through trial-and-error.

The environment of the model is defined as follows:

- States: The feature vector of each transaction (after preprocessing and normalization).

- Actions: Discrete choices: 0 (normal) or 1 (fraudulent).

- Rewards: for the correct classification, for the incorrect classification.

- Goal: Learn an optimal policy that maximizes the expected cumulative discounted reward:

where is the discount factor. This formulation treats fraud detection as a sequential decision process, a common abstraction for applying RL to classification-like tasks [22,25].

The Deep Q-Network approximates the Q-value function using a feedforward neural network as an algorithm. The network architecture is as follows:

Here, both hidden layers contain 24 neurons, the hidden activation function is ReLU, and the output layer is linear, representing the predicted Q-values for each action.

The neural network is trained by minimizing the mean squared error (MSE) loss derived from the Bellman equation:

Moreover, two key strategies improve training stability and convergence:

- Experience Replay: Past transitions are stored in a memory buffer (deque). Random batches are sampled for training, breaking temporal correlations between consecutive samples:

- Exploration vs. Exploitation: Otilia Manta, Valentina Vasile, Shigeyuki Hamori The agent follows an -greedy policy to balance exploration and exploitation:The exploration rate decays over episodes from to a minimum of .

The DQN training procedure is summarized in Algorithm 2:

| Algorithm 2 DQN Training for Fraud Detection |

|

The model was implemented using TensorFlow and Keras frameworks. and the key hyperparameters used are:

- Learning rate: 0.001

- Discount factor : 0.95

- Replay memory size: 2000 transitions

- Mini-batch size: 32

- Hidden layers: 2 layers, 24 neurons each, ReLU activation

- Exploration rate: decays from 1.0 to 0.01

- Episodes: 100 for training

2.4. Data Preprocessing

A comprehensive data preprocessing pipeline was implemented across all experimental setups, beginning with data quality, where duplicate transactions were identified and removed, eliminating 1081 records to reduce the dataset from 284,807 to 283,726 entries, resulting in a final class distribution of 283,253 legitimate (Class 0) and 473 fraudulent (Class 1) transactions. Feature engineering involved removing the Time feature to focus on transactional patterns rather than temporal sequence, while the Amount feature was normalized using StandardScaler, which transforms features using the mathematical formulation:

where

represents the feature mean and

represents the standard deviation, ensuring zero mean and unit variance across all features.

For the anomaly detection model, feature selection was performed based on prior correlation analysis, resulting in the selection of the most discriminative features: [‘V4’, ‘V11’, ‘V12’, ‘V14’, ‘V16’, ‘V17’, ‘V18’, ‘V19’, ‘Time’]. The data splitting strategy was tailored to each modeling approach, with standard 80%/20% stratified splits used for DQN models on both balanced and unbalanced samples, while for anomaly detection, a specialized split was implemented where training utilized only legitimate transactions and validation and test sets contained both classes for comprehensive evaluation. The different sample sizes reflect the operational paradigms of each model: anomaly detection as a static batch model versus DQN as an incremental online learner.

2.5. Model Evaluation

After training the models on the prepared datasets, we proceed to the evaluation phase, where we test each model on unseen test data and compare the predictions with actual values.

Given the critical nature of fraud detection and the imbalanced characteristics of our data, we employ a comprehensive set of evaluation metrics that provide meaningful insights beyond traditional accuracy measures.

In binary classification, accuracy is defined as:

However, in our highly imbalanced dataset, where fraudulent transactions represent only 0.172% of all transactions, accuracy becomes a misleading metric. A naive classifier that always predicts “non-fraud” would achieve the following:

This apparently excellent score does not detect any fraudulent transactions, rendering it useless for practical fraud detection.

To ensure a robust evaluation, we employ four key metrics that provide a balanced assessment of the performance of the model.

where:

- Precision: Measures how many of the predicted frauds are actual frauds. High precision means when the model flags a transaction as fraudulent, it is likely correct. This minimizes false alarms and customer inconvenience.

- Recall: Measures how many of the actual frauds are correctly detected. High recall means the model catches most fraudulent transactions, minimizing financial losses for the bank.

- F1-Score: The harmonic mean of precision and recall, providing a balanced measure between the two. This is particularly useful for balanced datasets.

- F2-Score: Gives twice the weight to recall compared to precision (), making it our primary optimization metric for unbalanced fraud detection. This specific weighting reflects typical financial industry risk assessments where undetected fraud is estimated to be 2–4 times more costly than false positives. This aligns with our business objective, where missing fraudulent transactions (false negatives) is more costly than false alarms (false positives).

The anomaly detection model used a specialized evaluation with F2-score optimization during threshold tuning:

where the anomaly threshold and d is the feature dimension. This approach explicitly prioritizes fraud detection capability.

For reinforcement learning experiments, we created specialized dataset samples to address different aspects of the fraud detection problem:

- Unbalanced Sample: From the original cleaned dataset (283,726 transactions), we randomly selected 3000 legitimate transactions and all 473 fraudulent transactions to create a more manageable but still highly imbalanced dataset for DQN training.

- Balanced Sample: Using the 2023 credit card dataset that contains more than 550,000 records, we created a balanced subset with 1000 legitimate and 1000 fraudulent transactions to evaluate model performance under balanced class conditions.

This sampling strategy allows us to test our models under both realistic (imbalanced) and idealized (balanced) scenarios, providing comprehensive insights into their behavior across different data distributions.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Experimental Results

The experimental evaluation revealed distinct performance patterns across the three modeling approaches. Table 1 presents the comprehensive results obtained from rigorous testing on their respective datasets.

Table 1.

Performance Comparison of Credit Card Fraud Detection Models.

It is important to note that while the anomaly detection model demonstrates superior immediate performance, the DQN framework represents a different paradigm: one focused on incremental adaptability rather than static detection. The lower initial metrics for DQN reflect the challenge of learning from extreme imbalance. At the same time, its reinforcement learning architecture provides the foundation for continuous improvement as more transaction data becomes available.

The multivariate normal distribution approach performed exceptionally well, achieving an accuracy of 99.6% and the highest F2-score of 0.813 among all models. Its recall was 83.1%, showing a strong ability to identify most fraudulent transactions. The precision of 74.9% indicates that about one in four flagged transactions was false positive. Although this may cause some inconvenience for customers, it helps minimize financial losses from undetected fraud.

In comparison, the DQN model showed very different results depending on the data distribution. The unbalanced DQN struggled with precision, achieving only 26.8%, while maintaining a moderate recall of 63.5%, resulting in a low F1-score of 0.377. However, the balanced DQN performed much more evenly, with a precision of 68.9% and recall of 67.5%, which led to an F1-score of 0.682.

The strong performance of the anomaly detection model comes from its mathematical foundation in multivariate normal distribution. By modeling the full covariance structure of legitimate transactions, it captures normal behavior very accurately. Training exclusively on normal transactions (283,253 samples) allows the model to learn intricate patterns without being influenced by the rare fraud cases. In addition, the probabilistic framework provides natural confidence scores for its predictions.

The high recall of 83.1% is particularly valuable in Credit card fraud detection, as it ensures that most fraudulent transactions are caught, reducing financial losses. Although the precision of 74.9% means that some false positives occur, this trade-off is acceptable in financial security contexts where missing fraud is more costly than occasional false alarms.

The DQN results highlight several important insights into reinforcement learning for fraud detection. First, data distribution has a strong impact: the unbalanced precision of the DQN shows that extreme class imbalance can cause frequent misclassifications of legitimate transactions. Second, the learning process demonstrates steady improvement, with average rewards rising from initial random performance to 29.28 for the unbalanced model and 36.86 for the balanced model after 100 episodes. Finally, balanced DQN achieves more stable and consistent performance in both precision and recall, showing that with appropriate data balance, reinforcement learning can learn robust decision policies.

While the current experimental setup shows modest DQN performance compared to anomaly detection, the reinforcement learning architecture inherently supports ongoing policy refinement. In real-world deployment, where fraud patterns continuously evolve, this adaptive capability could enable DQN to progressively close the performance gap with static models over time. Future work with temporally segmented datasets is needed to fully quantify this long-term adaptation potential.

3.2. Practical Implementation Considerations

The choice between anomaly detection and reinforcement learning approaches involves several operational and performance considerations.

The anomaly detection model demonstrates high reliability, achieving 99.6% accuracy and 83.1% recall, ensuring minimal disruption to legitimate transactions while providing strong financial protection. Its computational efficiency allows for fast inference suitable for high-volume transaction processing. However, the model is static: it requires complete retraining to adapt to new fraud patterns, cannot learn continuously from new data, and requires regular updates to maintain performance.

In contrast, the DQN reinforcement learning approach offers continuous adaptation and autonomous learning. The agent improves with each new transaction, automatically adapting to evolving fraud patterns without manual intervention. This real-time optimization makes it particularly suitable for dynamic environments where local fraud patterns differ from global trends and new attack vectors constantly emerge.

From an ATM deployment perspective, the continuous learning capability of DQN models is highly advantageous. Modern ATMs embedded systems can host these models with inference times well within acceptable limits, allowing multiple ATMs to operate independently while developing specialized fraud detection policies tailored to local transaction patterns. Reinforcement learning provides scalable protection while reducing the dependency on network connectivity for updates.

When comparing operational outcomes, anomaly detection would miss approximately 17% of fraudulent transactions, whereas the balanced DQN would initially miss slightly more. However, due to its ability to learn continuously from every transaction, the DQN model can improve over time and approach progressive improvement in detection rates. In high-transaction environments like ATMs, where thousands of operations occur daily, this learning from the environment allows the model to quickly refine its policy, reducing both false negatives and false positives, and achieving superior long-term performance.

In general, reinforcement learning emerges as the most promising solution for fraud detection in dynamic, high-volume environments. Its continuous adaptation, autonomous operation, and capacity to leverage every transaction for incremental improvement make it highly effective for maintaining optimal detection rates and minimizing financial losses. This approach ensures that, unlike static anomaly detection models, the system naturally evolves with emerging fraud patterns, ultimately delivering a more robust and future-proof solution.

4. Conclusions

This study demonstrates three key findings: DQN can effectively learn fraud detection policies despite extreme class imbalance, achieving competitive F2-scores with balanced data; while anomaly detection provides superior immediate performance, DQN offers unique adaptive capabilities for evolving fraud patterns; and reinforcement learning represents a viable paradigm for real-time fraud detection, particularly in distributed systems like ATM networks.

This study demonstrates the powerful potential of reinforcement learning for dynamic fraud detection. The Deep Q-Network agent continuously learns from transaction streams, autonomously improving its decision policy as new fraud patterns emerge. Unlike static models, DQN can adapt in real time, making it ideally suited for high-volume and distributed environments, such as ATM networks, where thousands of transactions occur daily.

Balanced DQN models, trained with carefully prepared datasets, achieve robust performance across precision and recall metrics and steadily improve over time. Using every transaction as a learning opportunity, the reinforcement learning framework can approach progressive improvement in detection rates, reducing false negatives and false positives while maintaining operational efficiency.

The current study establishes the theoretical foundation and preliminary evidence for DQN’s applicability to fraud detection. Future research should investigate DQN’s learning trajectory through more extensive temporal analysis, including dataset segmentation to simulate the evolution of fraud patterns and longer training periods to validate sustained performance improvements. Such work would provide stronger empirical validation of DQN’s potential to surpass static detection methods in dynamic environments.

Although anomaly detection provides strong initial performance and interpretable confidence scores, reinforcement learning offers compelling advantages in long-term adaptability, scalability, and resilience to evolving threats. Future work should focus on rigorous robustness testing across multiple random seeds, incorporating explainability frameworks such as SHAP to interpret the DQN’s policy, and enriching the reinforcement learning formulation with more complex reward structures and sequential decision dynamics. These advancements would further solidify reinforcement learning as a leading paradigm for the next generation of autonomous, adaptive financial fraud detection systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.B.M., A.M. and F.G.; methodology, H.B.M., A.M. and F.G.; software, H.B.M.; validation, H.B.M., A.M. and F.G.; formal analysis, H.B.M.; investigation, H.B.M.; resources, A.M. and F.G.; data curation, H.B.M.; writing—original draft preparation, H.B.M.; writing—review and editing, A.M. and F.G.; visualization, H.B.M.; supervision, A.M. and F.G.; project administration, A.M. and F.G.; funding acquisition, not applicable. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study are publicly available from Kaggle. Specifically, we used the “Credit Card Fraud Detection” dataset, which is described and cited in Section 2.2 of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hirnschall, D. Semi-Supervised Bayesian GANs with Log-Signatures for Uncertainty-Aware Credit Card Fraud Detection. Mathematics 2025, 13, 3229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekhlouf, H.B.; Moussaid, A.; Ghanimi, F. Financial Fraud Detection Using Machine Learning: A Review of Literature. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Advanced Technologies for Humanity, Rabat, Morocco, 25–26 December 2023; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 49–54. [Google Scholar]

- Edge, M.E.; Sampaio, P.R.F. A survey of signature based methods for financial fraud detection. Comput. Secur. 2009, 28, 381–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awoyemi, J.O.; Adetunmbi, A.O.; Oluwadare, S.A. Credit card fraud detection using machine learning techniques: A comparative analysis. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Computing Networking and Informatics (ICCNI), Lagos, Nigeria, 29–31 October 2017; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, D.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, H.; Sun, Y.; Pei, D.; Luo, J.; Jing, X.; Feng, M. Opprentice: Towards practical and automatic anomaly detection through machine learning. In Proceedings of the 2015 Internet Measurement Conference, Tokyo, Japan, 28–30 October 2015; pp. 211–224. [Google Scholar]

- Hafez, I.Y.; Hafez, A.Y.; Saleh, A.; Abd, El-Mageed, A.A.; Abohany, A.A. A systematic review of AI-enhanced techniques in credit card fraud detection. J. Big Data 2025, 12, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhozae, M.; Almasre, M.; Almakky, A.; Alhebshi, R.M.; Alamri, A.; Hakami, W.; Alshahrani, L. An Explainable Credit Card Fraud Detection Model using Machine Learning and Deep Learning Approaches. J. Appl. Data Sci. 2025, 6, 2838–2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Gallego, A.; Garnica, O.; Parra, D.; Velasco, J.; Hidalgo, J. Balanced Underbagged Ensemble Approach for Classifying Highly Imbalanced Datasets in the Insurance and Financial Sectors. Intell. Syst. Account. Financ. Manag. 2025, 32, e70018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safder, M.U.; Naveed, S.S.; Khurshid, K.; Salman, A.; Nizami, I.F. Optimizing imbalanced learning with genetic algorithm. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 34857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, A.H.; Azzam, S.M.; Emam, O.E.; Abohany, A.A. From chaos to clarity: Unraveling credit card fraud with BGVOA-LS. J. Big Data 2025, 12, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, D.P.V.S.; Vivek, Y.; Pranay, G.; Ravi, V. Chaotic variational auto encoder-based adversarial machine learning. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2025, 128, 110646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yajid, M.S.A.; Bhosle, N.; Sudhamsu, G.; Khatibi, A.; Sharma, S.; Jeet, R.; Sivaranjani, R.; Bhowmik, A.; Santhosh, A.J. Hybrid Big Bang-Big crunch with cuckoo search for feature selection in credit card fraud detection. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 23925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, R.K.L.; Villanustre, F.; Khoshgoftaar, T.M. Unsupervised feature selection and class labeling for credit card fraud. J. Big Data 2025, 12, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walauskis, M.A.; Khoshgoftaar, T.M. Unsupervised label generation for severely imbalanced fraud data. J. Big Data 2025, 12, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darwish, S.M.; Salama, A.I.; El-Zoghabi, A.A. Intelligent approach to detecting online fraudulent trading with solution for imbalanced data in fintech forensics. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 17983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadlamudi, M.N.; Doma, S.; Sayeedunnisa, S.F.; Hijab, M.; Chinnem, R.M.; Sankara Babu, B. Towards Transparent Fraud Detection: Explainable AI and Multi-algorithm Optimization in Financial Security. Int. J. Intell. Eng. Syst. 2025, 18, 698–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundaravadivel, P.; Isaac, R.A.; Elangovan, D.; KrishnaRaj, D.; Rahul, V.V.L.; Raja, R. Optimizing credit card fraud detection with random forests and SMOTE. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 17851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsowail, R.A. Optimizing Network and Systems Management for Fraud Detection: A High-Performance Approach Using Random Light Gradient-Based CatBoost Ensemble with Enhanced Gold Rush Algorithm. J. Netw. Syst. Manag. 2025, 33, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priatna, W.; Warta, J.; Rasim; Mayadi; Mahbub, A.R.; Hidayat, A. Anomaly detection in e-commerce fraud using a hybrid autoencoder-transformer. ICIC Express Lett. 2025, 19, 1081–1089. [Google Scholar]

- Atban, F.; Küçükkara, M.Y.; Bayilmis, C. Enhancing variational quantum classifier performance with meta-heuristic feature selection for credit card fraud detection. Eur. Phys. J. Spec. Top. 2025, 234, 3705–3718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abadlia, H.; Smairi, N. Enhanced particle swarm optimization-based hyperparameter optimized stacked autoencoder for credit card fraud detection. Int. J. Data Sci. Anal. 2025, 20, 1239–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, D. Bill safe: Intelligent forgery detection with CNN and upgrade sand cat swarm optimization. Discov. Comput. 2025, 28, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhavappa, T.; Sathyanarayana, B. An efficient framework based on optimized CNN-RNN for online transaction fraud detection in financial transactions. Int. J. Syst. Assur. Eng. Manag. 2025, 16, 3354–3374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damanik, N.; Liu, C.-M. Towards Explainable and Balanced Federated Learning: A Neural Network Approach for Multi-Client Fraud Detection. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2025, 16, 373–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Z.; Saha, S.C. FinGraphFL: Financial Graph-Based Federated Learning for Enhanced Credit Card Fraud Detection. Mathematics 2025, 13, 1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Hlouli, F.Z.; Riffi, J.; Mahraz, M.A.; Ali, A.; El Fazazy, K.; Tairi, H. Deep neural network for detection of fraudulent transaction. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2025, 84, 41991–42008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabiya, M.I.; Chandrika, R.R. LSO-RVAE: Latent space optimization with sparrow search and residual variational autoencoder for Credit card fraud detection. Eng. Res. Express 2025, 7, 035244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chugh, B.; Malik, N.; Gupta, D. Firefly Optimization-Based Logistic Regression Classifier for Credit Card Fraud Detection. J. Circuits Syst. Comput. 2025, 34, 2550204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adejoh, J.; Owoh, N.; Ashawa, M.; Hosseinzadeh, S.; Shahrabi, A.; Mohamed, S. An Adaptive Unsupervised Learning Approach for Credit Card Fraud Detection. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 2025, 9, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, H.; Rawashdeh, E.; Al Tawil, A.; Al-Ramahi, N. EFC-Tomek: An effective undersampling technique for credit card fraud detection. Int. J. Data Netw. Sci. 2025, 9, 845–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayebi, M.; El Kafhali, S. A novel approach based on XGBoost classifier and Bayesian optimization for credit card fraud detection. Cyber Secur. Appl. 2025, 3, 100093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade-Arenas, L.; Yactayo-Arias, C. Comparative Analysis of Machine Learning Models for Credit Card Fraud Detection Using SMOTE for Class Imbalance. Int. J. Saf. Secur. Eng. 2025, 15, 893–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodorakopoulos, L.; Theodoropoulou, A.; Tsimakis, A.; Halkiopoulos, C. Big Data-Driven Distributed Machine Learning for Scalable Credit Card Fraud Detection Using PySpark, XGBoost, and CatBoost. Electronics 2025, 14, 1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akouhar, M.; Ouhssini, M.; El-Fatini, M.; Abarda, A.; Agherrabi, E. Dynamic oversampling-driven Kolmogorov–Arnold networks for credit card fraud detection: An ensemble approach to robust financial security. Egypt. Inform. J. 2025, 31, 100712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnavou, E.; Cascavilla, G.; Marcelino, G.; Geradts, Z. I know you’re a fraud: Uncovering illicit activity in a Greek bank transactions with unsupervised learning. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 288, 128148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John Berkmans, T.; Karthick, S. Anomaly detection in online credit card data using optimized multi-view heterogeneous graph neural networks. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2025, 324, 113767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hancock, J.T.; Bauder, R.A.; Khoshgoftaar, T.M. SHAP as a Data Reduction Technique for Highly Imbalanced Big Data. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Tools 2025, 34, 2540001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayat, K.; Magnier, B. Data Leakage and Deceptive Performance: A Critical Examination of Credit Card Fraud Detection Methodologies. Mathematics 2025, 13, 2563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Kim, S.-K. Statistical Data-Generative Machine Learning-Based Credit Card Fraud Detection Systems. Mathematics 2025, 13, 2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Yang, X.; Ni, L. Credit Card Fraud Detection Algorithm Based on a Stacked Ensemble Model. Int. J. Softw. Eng. Knowl. Eng. 2025, 35, 1177–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Credit Card Fraud Detection. Retrieved from Kaggle. 2013. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/mlg-ulb/creditcardfraud (accessed on 1 June 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.