Abstract

In response to the pressing climate change emergency, the rapid expansion of renewable energies, particularly photovoltaic (PV) power in Spain, is reconfiguring national energy landscapes, thereby necessitating detailed spatial analysis. This study aims to characterise the spatial distribution of PV energy in the country. Specifically, it employed the Administrative Register of Electricity Production Facilities (RAIPEE) database from 2000 to 2023 and a review of Environmental Impact Statements (EIA) from 2014 to 2023 to generate a facility density cartography. Additionally, the spatial statistic Moran’s I was used to detect aggregation patterns. The results demonstrated an aggregation tendency for low and medium power facilities (up to 10 MW), while the distribution of higher-capacity facilities appeared random. Examination of the facility density cartographies suggest significant variability among provinces and distribution trends centred around the country’s main urban regions. This approach to understanding the spatial dynamics of PV energy offers novel and crucial geospatial insights for renewable energy planning.

1. Introduction

In recent decades, the unprecedented development of renewable energy sources on a global scale constitutes a transformative phenomenon in the history of human energy [1]. This process unfolds within a context of profound ecological crisis [2,3,4,5,6,7]. The imperative to develop energy systems with a lower socio-environmental impact positions renewable sources as a fundamental pillar for overcoming the dependence on fossil fuels, the massive consumption of which has characterized the energy regime since the nineteenth century [8].

Despite considerable progress in deploying renewable energy technologies, the utilization of fossil fuels continues to drive climate change, resulting in severe environmental outcomes such as elevated temperatures. Furthermore, the period between 2005 and 2018 witnessed a marked increase, with global greenhouse gas emissions rising by 23% [9].

Since 1990, Spain’s energy consumption has exhibited a notable evolution, characterized by sustained growth that culminated with the 2008 financial crisis. Subsequently, a shift in trend has been observed, with total consumption undergoing a slight yet persistent decline. In 2023, the consumption of primary energy (energy extracted directly from nature, such as fossil fuels or wind) amounted to 110,065,000 tonnes of oil equivalent (toe). Conversely, final energy consumption (the usable energy after transformation processes, such as electricity or gasoline) was recorded at 81,465,000 toe [10].

Despite the aggregate reduction in total consumption, the composition of Spain’s final energy consumption remains strongly dominated by non-renewable sources. In 2023, fossil fuels accounted for 69% of final consumption, with a clear preponderance of oil (45%) and natural gas (22%). Coal, historically a key source, has been relegated to a modest 2% contribution. Electricity constituted 24% of consumption, while biomass supplied the remaining 7% [11].

Within electricity generation in Spain, the remarkable development of renewable energy sources has been notably conditioned by public policies, which have oscillated between development and stagnation according to the country’s economic circumstances [12]. However, in 2023, renewables accounted for 52.4% of the national electricity generation [13]. Within renewable generation, wind power was the primary source, contributing 46.6% of the total renewable output [13]. PV energy has emerged with notable force, consolidating its position as the second most important renewable source by contributing 27.8% [13]. Hydropower accounted for 18.8%, while other renewable sources contributed the remaining 6.8% [13].

Mirroring the trend observed in utility-scale facilities, PV self-consumption has experienced unprecedented growth. Since 2018, the annual installed self-consumption capacity has increased at rates ranging from 44% to 54%, rising from 380 MW to 7154 MW between 2018 and 2023. This cumulative capacity is now equivalent to 3% of the total electricity demand [14].

The development of renewable energy is not only a technological process but also a geographical phenomenon insofar as it transforms the geography of energy appropriation. This is particularly evident in PV energy, which requires large land extensions for large-scale electricity generation, thus forming a “horizontal energy regime” [15]. Consequently, the present study aims to characterize the spatial distribution of PV facilities in Spain, hypothesizing that their distribution is not random. Simultaneously, it seeks to establish a systematic and comprehensive methodology for generating cartographic representations of PV facilities.

2. Materials and Methods

For the study’s objective, a methodology based on three main pillars was established. Firstly, an autocorrelation analysis of the PV facilities was performed using the spatial statistic of Moran’s Index to determine the existence or absence of spatial clustering at the national scale. Subsequently, the distribution and concentration of PV facilities were represented by heat maps generated via kernel density interpolation, performed using QGIS 3.34 Prizren software, thereby forming a set of energy cartographies associated with PV energy.

2.1. Database of PV Facilities

The compilation of a municipal-level database of PV facilities was necessary to analyse their distribution. The Administrative Registry of Electricity Production Facilities (RAIPEE), managed by the Ministry for the Ecological Transition and the Demographic Challenge [16], constitutes the most comprehensive official database, encompassing most electricity generation facilities in Spain, along with their installed capacity and municipal-level location.

Facilities registered in the RAIPEE are categorized into regulatory groups based on generation technologies, as established by Royal Decree 413/2014 of 6 June, which regulates the activity of electricity production from renewable energy sources, cogeneration, and waste [17].

The geolocation of the facilities is performed using the municipal information contained in the RAIPEE, as this registry specifies the municipality of installation. This approach enables the creation of cartographies by employing centroids within the municipal polygons, thereby providing an aggregated spatial representation of their distribution.

Additionally, to complement the cartography, a review of PV facilities subjected to Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) was conducted. The EIA process culminates in the Environmental Impact Statement (EIS), which is published in the Official State Gazette (Boletín Oficial del Estado or BOE). The EIS details the basic technical characteristics of the project, such as the municipality of installation and the power capacity.

Accordingly, two mass searches were performed on the BOE webpage using the following parameters:

- First search: The first search focused on all final EIS that also contain any word with the root “sol” (solar):

- Title: “formula declaración de impacto ambiental” (formulates environmental impact statement) AND sol *

- Publication Date: From 1 January 1998 to 31 December 2023

- Second search: The second search targeted all final EIS declarations that also contain any word with the root “fot” (PV):

- Title: “formula declaración de impacto ambiental” (formulates environmental impact statement) AND fot *

- Publication Date: From 1 January 1998 to 31 December 2023

Although the projects reviewed in the BOE have received a favourable EIA, this does not guarantee their eventual construction, as they may undergo modifications after the EIS. Since most of these facilities are not yet operational, they were not used in the correlation analyses. However, they were employed to create supplementary cartographies through Kernel Density Estimation because they allow for a general visualization of how the geography of PV facilities might evolve in the future.

Classification by Power Capacity Groups

Given the assumption that the distribution of facilities may vary significantly based on installed capacity, and to offer greater precision in the results, distinct power groups have been defined. Consequently, an independent analysis has been performed for each of these groups.

The development of PV energy in Spain is closely linked to successive changes in energy policy and state incentives [9]. Over the period spanning 1998 to 2023, the typology of new facilities has evolved significantly, shifting from a predominance of small-scale projects to a concentration of large PV facilities.

The power thresholds utilized are based on the limits established by the various legislative and regulatory frameworks that have influenced the sector over the years. Specifically, reference is made to the regulations that facilitated the sector’s development through state aid, particularly during the period of substantial growth between 1998 and 2008.

The categories comprise right-semi-open intervals; thus, each interval includes the lower limit and excludes the upper limit. Furthermore, this classification facilitates improved visualization of energy cartographies and a precise analysis of each power group. The categories are defined as follows:

- 0–5 kW

- 5–100 kW

- 100 kW–1 MW

- 1–10 MW

- 10–50 MW

- 50–600 MW

2.2. Moran’s Index

To characterise the spatial distribution patterns of PV facilities, it is necessary to employ inferential statistics to reject the initial hypothesis that the distribution of the facilities is random. For this purpose, Global Moran’s Index (Moran’s I) has been used. This spatial autocorrelation statistic enables the determination of whether the distribution of an attribute (in this case, the number of PV facilities by power group) across a set of geographical entities (the municipalities hosting these facilities) exhibits a clustered, dispersed, or random spatial pattern. Moran’s I is calculated using Equation (1):

where is the number of entities, is the deviation of the attribute of entity from the mean , is the spatial weighting between entity and entity , and is the sum of these spatial weights. This index was chosen due to its capability to easily observe the spatial autocorrelation of a variable, which, in this case, is PV facilities. It is an index widely used in research subjects like the one addressed in [18].

To detect potential aggregation patterns, a spatial relationship based on Inverse Distance was selected, meaning the influence of entities is greater the closer they are, decreasing linearly with distance. Furthermore, a distance band of 30 km was considered for the definition of clusters. This choice ensures that all facilities are encompassed and that their distribution patterns are captured within a nationally relevant geographical radius.

Moran’s I is an inferential statistic, meaning its result must be interpreted in the context of a null hypothesis (). assumes the initial hypothesis of this work, which is that the spatial distribution of the PV facilities is entirely random. By applying Moran’s I, the study aims to determine if there is sufficient statistical evidence to reject this null hypothesis and, consequently, accept the alternative hypothesis (), which posits that the distribution pattern of the PV facilities is non-random.

To make this decision, the QGIS software that calculates Moran’s I provides a p-value and a z-score in addition to the index value itself.

- The p-value represents the probability that the observed distribution is the result of chance, assuming the null hypothesis is true. In this study, the result is considered statistically significant (allowing H0 to be rejected) when the probability of the distribution being random is less than 1%, meaning p < 0.01. A p > 0.01 value would suggest that the null hypothesis cannot be rejected (Complete Spatial Randomness or CSR).

- The z-score is the number of standard deviations the observed Moran’s I is away from its expected value under the null hypothesis. When the z-score is very high or very low (i.e., it lies at the extremes of the standard normal distribution, and the p-value is low), there is strong evidence to reject H0.

2.3. Kernel Interpolation

To visualize the distribution patterns of the facilities, the Kernel density interpolation technique was employed. This method creates a continuous density surface that highlights geographical areas with the highest concentration of facilities, providing a graphical representation that both validates and complements the results from the Moran’s I. Kernel interpolation resulted in maps depicting the density of PV facilities.

An interpolation radius (bandwidth) of 30 km was established. This value ensures that the influence of each facility extends over a sufficient distance to capture the clusters identified by the Moran’s I, while avoiding excessive smoothing or a non-representative fragmentation of the patterns. Additionally, a pixel size (cell size) of 1 × 1 km was defined. This resolution allows for a detailed representation of the densities, yielding maps with sufficient precision to discern regional distribution patterns.

When analysing the resulting cartographies, although the analyses are performed using municipal-scale databases, the extent of the records and the number of municipalities necessitate presenting the results at the national scale, distinguishing between distribution patterns within each Autonomous Community (NUTS 2). The Spanish territory is divided regionally into 17 Autonomous Communities (Figure 1), which are further subdivided into a total of 50 provinces (NUTS 3) (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Administrative division in Autonomous Communities (NUTS 2).

Figure 2.

Administrative division in Provinces (NUTS 2).

3. Results

The RAIPEE database contains a total of 63,489 registered facilities. Additionally, a separate register of 408 facilities that obtained a favourable EIS up to 2023 was compiled. Since the municipality of installation has been recorded for all entries, it is possible to map their location.

For the chronology of the EIS-registered facilities, the date of publication in the Official State Gazette (BOE) was considered. A comparative analysis between the register of favourable EIS and the RAIPEE revealed an overlap, as 15 facilities with a favourable EIS were already registered in the RAIPEE between 2019 and 2022.

3.1. Autocorrelation Patterns

When all PV facilities are considered collectively, the analysis reveals a positive Moran’s I, with a high z-score of 35.92 and p-value < 0.01. These results provide significant statistical evidence to reject the null hypothesis () of spatial randomness. Consequently, it is concluded that the distribution of PV facilities in Spain, when taken in its entirety, reflects positive spatial autocorrelation; that is, there is a tendency for facilities to cluster in proximity.

However, when performing the analysis by separating facilities into distinct power ranges, an interesting trend is observed: spatial autocorrelation decreases as the installed capacity of the facilities increases.

For the lower power ranges (0–5 kW and 5–100 kW), the positive Moran’s I is more pronounced (z = 13.84 p < 0.01 and z = 20.09 p < 0.01, respectively), indicating a strong tendency towards clustering. This is likely attributable to the mass installation of rooftop PV systems in urban and peri-urban areas. These zones, characterized by a high density of buildings, naturally induce an aggregation of smaller-capacity facilities, as the availability of rooftops and local energy demand drive their proliferation in geographic proximity.

Power ranges between 100 kW and 10 MW show a similar tendency but with lower z-scores (z = 1.99 for facilities from 100 kW to 1 MW and z = 4.12 for facilities from 1 MW to 10 MW). While still statistically significant, the reduced z-score suggests a weaker degree of positive spatial autocorrelation compared to the smallest-scale facilities.

Conversely, the power ranges exceeding 10 MW exhibit seemingly random distribution patterns. For these large-scale facilities, the obtained values are p > 0.01 and z < 1.5 (specifically z = 1.44 for 10 MW to 50 MW facilities and z = 0.71 for 50 MW to 600 MW facilities), which precludes the rejection of the null hypothesis of randomness. This suggests that large PV plants, which are often subject to requirements for vast tracts of land and specific grid connection conditions, do not show a marked tendency to cluster spatially with other facilities of similar capacity.

3.2. PV Energy Cartographies

Generally, it is observed that the development of installed PV capacity tends to diffuse from urban cores toward peripheral areas. These urban cores, being centres of high economic activity and energy consumption, act as development poles for PV facilities, particularly those associated with self-consumption and smaller facilities.

The greatest concentrations of development are primarily located around major urban centres, though significant expansion is also evident beyond these densely populated areas. This trend is particularly pronounced in the southern half of the country, where solar radiation conditions are optimally more favourable than in the north.

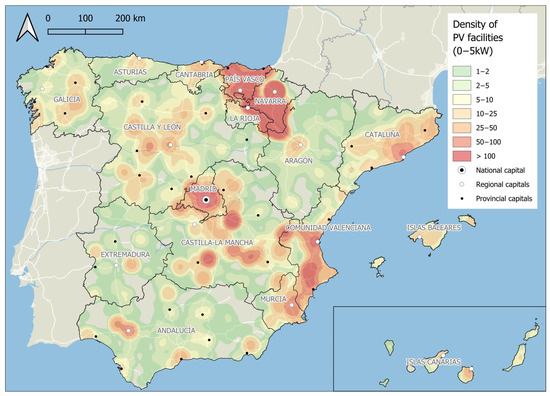

3.2.1. PV Facilities with Capacity of 0–5 kW

PV facilities with capacities ranging from 0 to 5 kW represent a significant portion of registered units but contribute marginally to Spain’s overall installed capacity. As of 2023, these low-capacity units totalled 12,937 operative facilities, accounting for 20.70% of all registered PV units, yet only 0.27% of the total national installed PV capacity (60.88 MW). The geographical distribution of these facilities varies considerably across the Autonomous Communities, revealing distinct regional density clusters (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Density of existing PV facilities of 0–5 kW.

A particularly dense cluster is observed in southern Navarra, which alone concentrates 41.90% of the total facilities and 44.14% of the capacity within the 0–5 kW range. Combined with País Vasco, these two Autonomous Communities account for over half (51.01%) of all facilities in this category (6599 units).

Along the Mediterranean coast, a substantial number of facilities are located, forming an urban-energy continuum. Comunidad Valenciana hosts 1192 facilities (9.21% of the total, 5409 kW), primarily distributed across the metropolitan areas of Valencia and Alicante. Concurrently, Murcia (300 facilities) exhibits a marked concentration within its capital city.

Castilla-La Mancha hosts a significant share of the facilities (1251 units, 9.67%, 6076 kW). However, the largest density centres in this power range are not located in the provincial capitals but rather in smaller municipalities (e.g., Daimiel, Socuéllamos, Munera). This spatial pattern distinguishes it from the urban-centric model of other regions, potentially reflecting the greater availability of peri-urban land or the proliferation of small-scale rural projects.

Madrid (756 facilities, 5.84%) and Cataluña (667 facilities, 5.16%) display a deployment pattern tightly linked to major urban centres. The majority of facilities and capacity (3405 kW and 2616 kW, respectively) are concentrated within the capital cities of Madrid and Barcelona and their corresponding metropolitan areas.

The remaining low-capacity facilities are distributed relatively equitably among the other Autonomous Communities (2172 facilities, 16.79%). In these territories, the density clusters predominantly occur in the provincial capitals and adjacent municipalities, such as Sevilla, Valladolid, Zaragoza, and Santander, reinforcing the urban-centric development model.

In summary, the dominant deployment pattern for the smallest capacity facilities is concentrated within provincial capitals and large urban areas. Cities such as Pamplona, Murcia, Madrid, Vitoria-Gasteiz, Sevilla, Valladolid, Bilbao, and Barcelona are prominent, all hosting over 30 facilities; Pamplona, notably, has 834 registered units. The high volume of low-capacity facilities within major urban areas strongly suggests that these facilities are predominantly self-consumption systems installed on building rooftops.

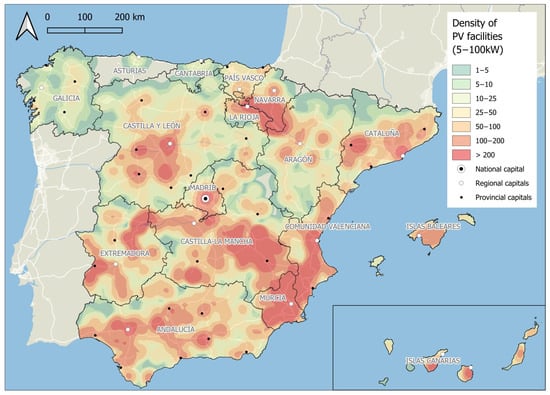

3.2.2. PV Facilities with Capacity of 5–100 kW

PV facilities with capacities between 5 and 100 kW represent the single largest group in Spain’s registered PV fleet by unit count. As of 2023, these facilities totalled 47,595 operative units, comprising 76.17% of all PV facilities registered in the RAIPEE. While their number is dominant, they collectively aggregate a total installed power of 3211.74 MW, which accounts for 14.16% of the country’s total PV capacity.

The territorial distribution of 5–100 kW facilities exhibit significant dispersion across the entire Spanish territory (Figure 4). Like the 0–5 kW group, urban centres, particularly provincial capitals, remain important concentration points. However, within this medium-capacity range, the area of concentration tends to expand considerably, extending into peri-urban zones.

Figure 4.

Density of existing PV facilities of 5–100 kW.

Furthermore, a notable proliferation is observed in large rural areas, particularly across Castilla-La Mancha, Murcia, Valencia, Extremadura, and Castilla y León. These regions, characterized by greater land availability, facilitate the development of projects at this intermediate scale. Similarly, the Guadalquivir Valley in Andalucía and the Ebro Valley in Aragón constitute significant areas of high concentration.

The largest concentrations of power and facilities are found in the following territories: Castilla-La Mancha leads the national deployment of these facilities, concentrating 10,264 units (21.57%) and 791.56 MW (24.65% of the group’s capacity). Its development is primarily centred in the provinces of Albacete, Cuenca, and Ciudad Real. Andalucía ranks as the second community in this segment, hosting 7357 facilities 15.46%) with an aggregate capacity of 617.02 MW (19.21%). The province of Sevilla is particularly prominent, concentrating a quarter of the Autonomous Community’s facilities, with the remainder distributed relatively equally among the other provinces. Following these leaders, Castilla y León concentrates 10.03% of the facilities (4775) and 10.58% of the capacity (339.83 MW), distributed primarily across the provinces of Valladolid, Zamora, Salamanca, and Ávila.

The remaining Autonomous Communities fall below 10% in both facilities and installed capacity within the 5 kW to 100 kW range. Notably, there is a low proliferation of this type of facility in the northern territories of the peninsula, which show very low percentages: Asturias (0.04%), Cantabria (0.11%), Galicia (0.88%), and País Vasco (0.87%). The situation in País Vasco is particularly noteworthy and contrasting, given its high concentration of very low-capacity (0–5 kW) facilities. This disparity suggests a greater regional preference for, or viability of, domestic rooftop self-consumption over larger-scale commercial and industrial projects.

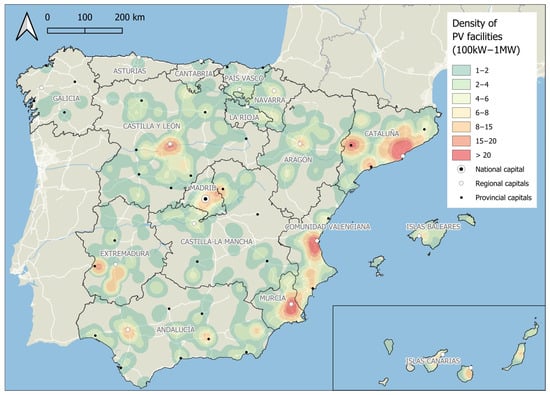

3.2.3. PV Facilities with Capacity of 100 kW–1 MW

PV facilities with capacities between 100 kW and 1 MW reveal distinct spatial dynamics within the Spanish territory compared to the patterns observed in lower power ranges. This group comprises 1024 registered facilities, equivalent to only 1.64% of Spain’s total PV facilities, yet they aggregate 490.64 MW, constituting 2.16% of the country’s total installed PV power.

Functional urban areas and metropolitan peripheries constitute the primary settings for the proliferation of these facilities (Figure 5). Unlike smaller-capacity facilities, the concentration of the 100 kW–1 MW power range tends to be situated in zones characterized by industrial activity.

Figure 5.

Density of existing PV facilities of 100 kW–1 MW.

An illustrative example of this trend is observed in the Community of Madrid, where the density core shifts away from the city centre toward the Henares industrial axis (northeast of the region). This geographical distribution strongly suggests that a significant fraction of the facilities in this power group corresponds to industrial or tertiary PV self-consumption systems, typically installed on factory rooftops or available land within industrial areas. Similarly, density clusters around provincial capitals tend to diffuse into their metropolitan coronas, where major industrial zones are commonly located. This phenomenon is notably evident in cities such as Valencia, Murcia, Seville, Badajoz, and Valladolid, thereby reinforcing the hypothesis that this power range is functionally linked to the electrification of industrial processes.

The distribution of these mid-range power facilities shows the following particularities by Autonomous Community. Cataluña concentrates the largest share of the facilities in this power range, accounting for 22.56% (231 units) and 90.25 MW installed capacity. Concentrations stand out in Barcelona, Lleida, and Tarragona, as well as their respective metropolitan areas. Castilla y León follows, concentrating 13.96% of the total facilities (143 units) and 16.29% of the capacity (79.93 MW), with the main density cluster found in and around Valladolid. The remaining Autonomous Communities collectively account for 63.48% of the facilities (650 units) and 65.32% of the total capacity (320.47 MW). The principal clusters of both facilities and capacity in these territories typically correspond to provincial capitals such as Granada, Zaragoza, Pamplona, León, Palencia, and Burgos.

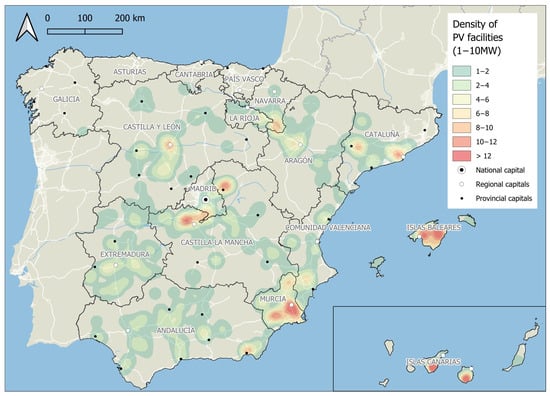

3.2.4. PV Facilities with Capacity of 1–10 MW

The development of PV facilities with capacities between 1 MW and 10 MW is less numerous than lower-capacity categories, yet their contribution to the total installed power is substantial. This range includes 566 registered facilities, representing a small fraction (0.91%) of the total PV facilities nationwide. However, despite their low unit count, these facilities aggregate 1974.36 MW, constituting 8.70% of the country’s total installed PV capacity.

The spatial distribution reveals that peri-urban areas concentrate a significant number of these facilities, demonstrating a clear functional link to areas with greater land availability and lower urban development pressure (Figure 6). These locations allow projects to benefit from proximity to the infrastructure and electricity demand associated with large urban agglomerations without incurring the cost or complexity of dense urban sites.

Figure 6.

Density of existing PV facilities of 1–10 MW.

The distribution of these facilities shows a significant concentration across four specific Autonomous Communities, which collectively host just over half (50.18%) of all units in this range: Castilla-La Mancha (80 facilities), Andalucía (79 facilities), Murcia (73 facilities), and Castilla y León (52 facilities).

A particular spatial pattern is observed in Castilla-La Mancha, where the majority of 1–10 MW facilities are in the provinces of Toledo and Guadalajara. This reveals a clear “border effect,” characterized by significant concentration clusters in the areas contiguous to the Community of Madrid. These border zones offer critical advantages: proximity to the capital for accessing high demand and robust grid infrastructure, coupled with a significantly greater availability of rural land compared to the central Madrid region itself.

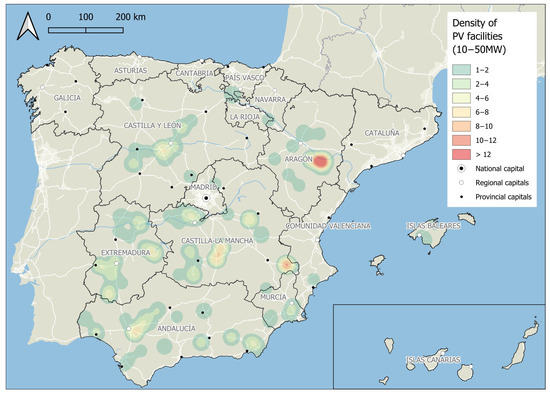

3.2.5. PV Facilities with Capacity of 10–50 MW

PV facilities with capacities between 10 MW and 50 MW constitute the largest share of solar generation capacity in Spain, despite their low unit count. These facilities account for only 348 facilities (0.56% of the national total) but contribute 12,829.24 MW, which is 56.55% of the country’s total installed PV power.

The spatial distribution of facilities in this power group exhibits a distinct behaviour compared to lower power ranges: the clusters of highest density decouple from major urban cores. Instead, peri-urban and rural areas act as the primary regions where these utility-scale facilities proliferate. The main concentration clusters are observed in Aragon, as well as in areas near important urban centres such as Valladolid, Guadalajara, Albacete, Badajoz, and Seville (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Density of existing PV facilities of 10–50 MW.

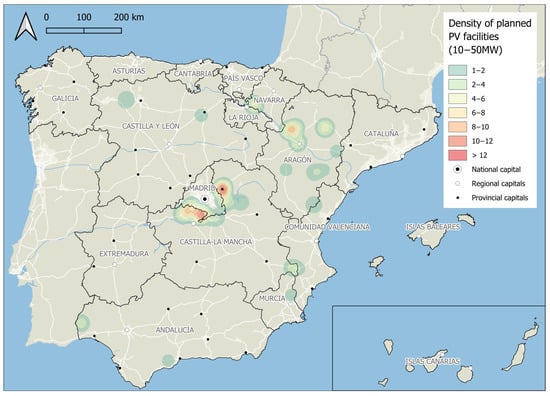

Complementing the data on operative facilities, the Environmental Impact Statements (EIS) approved up to December 2023 reveal a clear trend toward increasing installed capacity on the Madrid border with the contiguous provinces of Guadalajara and Toledo. Furthermore, significant prospective developments are evident on the periphery of Zaragoza and at isolated points in León, Navarra, Teruel, Huesca, and Huelva (Figure 8). This prospective EIS map strongly suggests a continuous expansion of large-scale PVs toward areas with high solar potential and extensive land availability.

Figure 8.

Density of planned PV facilities of 10–50 MW.

The concentration of these large-scale facilities is particularly notable within a few Autonomous Communities, which collectively aggregate most of the installed capacity in this range. Castilla-La Mancha leads the implementation of these projects, concentrating 30.17% of the facilities (105 units) and 29.99% of the associated capacity (3847.17 MW). More than half of these facilities are in the provinces of Ciudad Real (34 facilities) and Cuenca (28 facilities), though all provinces within the community host at least 11 facilities of this range. Andalucía ranks as the second region in this segment, hosting 73 facilities (22.04%) with a total capacity of 2927.50 MW (22.82%). Notably, one-third of these facilities are concentrated in the province of Sevilla. Extremadura shows a high concentration with 69 facilities (19.83%) and 2706.13 MW (21.09%). With 44 facilities in Badajoz and 25 in Cáceres, the region stands as one of the areas with the highest density of large-scale PV capacity, largely driven by its high solar potential and land availability. Aragon hosts 51 facilities (14.66%) totalling 1913.64 MW (14.92%), with the majority of these situated near the city of Zaragoza.

In synthesis, the analysis of the 10 MW to 50 MW PV facilities reveals an implementation pattern that decouples from the densest urban centres to seek locations in peri-urban and rural areas offering large extensions of available land.

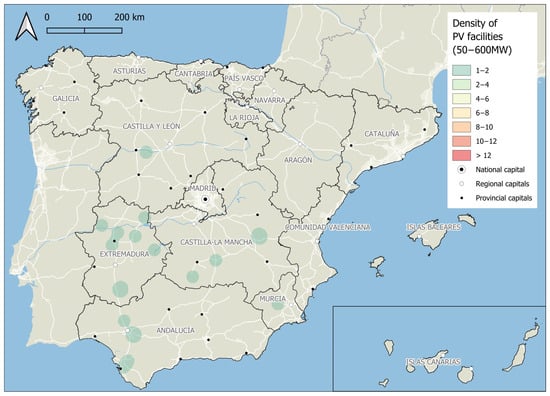

3.2.6. PV Facilities with Capacity of 50–600 MW

As of 2023, only 19 active facilities are registered in this capacity group. However, their impact on the generation fleet is significantly high: these 19 large-scale facilities account for 4118.94 MW, representing 18.16% of all installed PV capacity in the country.

The distribution of these facilities shows a concentration in the southern half of the country, a domain boasting one of the highest solar irradiances in Europe. Extremadura is consolidated as the leading Autonomous Community in this power group, hosting 8 facilities that collectively aggregate a total of 2345.70 MW (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Density of existing PV facilities of 50–600 MW.

Andalucía hosts 5 facilities, 3 of which are in Sevilla and 2 in Cádiz. In total, the Autonomous Community concentrates an installed capacity of 676.99 MW. Castilla-La Mancha host 4 facilities (2 in Cuenca and 2 in Ciudad Real) totalling 471.39 MW. Meanwhile, the Murcia has 1 facility with 493.66 MW. Finally, Castilla y León has 1 facility in the province of Zamora with a capacity of 131.20 MW.

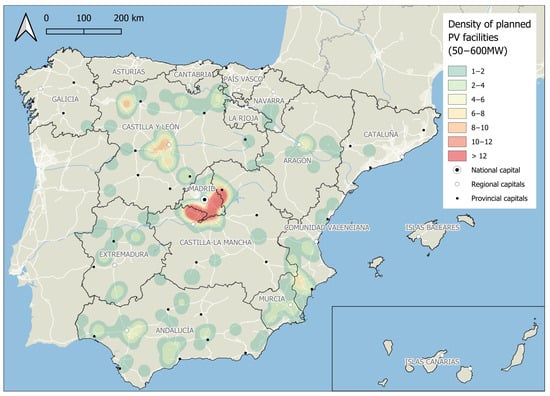

The analysis of favourable EIS is fundamental for clearly observing the future orientation of large-scale PV development. These EIS act as a prospective window into projects that could materialize in the coming years.

A notable feature is the formation of a high-power facilities ring to the south and east of Madrid, which complements and expands upon the 10–50 MW developments analysed previously. This ring not only encompasses the border zones of Guadalajara and Toledo but also shows expansion into the interior of the Autonomous Community of Madrid, specifically in the south-east of the region (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Density of planned PV facilities of 50–600 MW.

Furthermore, important generation clusters are projected in the peri-urban and rural areas of Valladolid, Zaragoza, Sevilla and León, as well as along the Mediterranean coast.

In sum, 50–600 MW facilities tend to be situated primarily in peri-urban areas and rural areas with large extensions of available land.

3.2.7. Main Spatial Patterns for PV Facilities

Despite the territorial heterogeneity in the distribution dynamics of PV facilities across Spain’s Autonomous Communities, it is possible to establish the following general location patterns based on the defined power groups.

- Pattern 1: Urban concentration of low-capacity facilities. Low-capacity installations, corresponding to the groups 0–5 kW, 5–100 kW, and 100 kW–1 MW, exhibit a tendency toward concentration within urban centres. This dynamic is particularly noticeable in regions housing the country’s largest metropolitan agglomerations, such as Madrid and Catalonia. This concentration is highly likely attributable to the proliferation of residential self-consumption PV on rooftops. Nevertheless, the 100 kW–1 MW group may include self-consumption installations for small industries, located on both rooftops and ground-mounted sites.

- Pattern 2: Peri-urban location of medium-capacity facilities. Higher-capacity facilities (group 1–10 MW) tend to move away from urban centres, concentrating instead in metropolitan rings. A preference is observed for municipalities that host large industrial areas. The capacity and distribution of these facilities strongly suggest they are primarily industrial self-consumption projects, sited on factory rooftops or adjacent industrial land. A prime example of this dynamic is found in the industrial area of Zaragoza (Aragón). However, it cannot be ruled out that a fraction of the installations at the upper end of this group may correspond to utility-scale generation facilities.

- Pattern 3: Rural location proximate to urban centres for high-capacity facilities. The highest-capacity facilities (groups 10–50 MW and 50–600 MW) show a more dispersed territorial distribution, yet their location is frequently circumscribed to rural areas near urban centres. Given their size, these are unequivocally ground-mounted generation facilities that require extensive land areas. This land requirement and the pursuit of lower land costs explain their placement in rural zones. Proximity to the main energy consumption centres (cities) implies a higher density of existing transport and distribution infrastructure, which potentially reduces grid connection costs and minimizes energy losses during transmission. This trend is evident in the rural areas of Guadalajara and Toledo bordering Madrid, as well as in the region’s southeastern rural area.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

This article has characterized the energy territories associated with PV power in Spain by undertaking a detailed analysis of the spatial distribution and development patterns of the PV infrastructure. Furthermore, the research establishes a robust methodology for mapping PV facilities, thereby constituting a valuable advance for future energy planning. The findings reveal a complex, non-random deployment landscape shaped by scale, urban geography, and land availability, leading to several key conclusions regarding PV development in Spain.

Firstly, the analysis provides significant statistical evidence confirming that the distribution of PV facilities is emphatically not random. Upon examining the distribution across different power groups, clear tendencies toward spatial concentration and clustering are observed. The analysis utilizing Moran’s I concludes that PV facility clusters exist both at the aggregate scale and distinctly within similar power ranges. This concentration is particularly pronounced in the lower-capacity groups (up to 1 MW), which are primarily associated with distributed generation and self-consumption. Conversely, the higher-capacity facilities (10 MW and above) exhibit a relatively more dispersed or random spatial distribution, reflecting the nature of utility-scale energy projects.

Secondly, although the cartography generated using Kernel interpolation constitutes a preliminary approximation to representing the spatial dynamics of PV energy in Spain, a potential relation can be distinguished between the number of lower-capacity facilities and the country’s highly urbanized regions. The influence of urban centres, particularly regional and provincial capitals, appears evident in Autonomous Communities such as Madrid, Cataluña, País Vasco, Aragon, and Murcia.

Generally, urban cores concentrate the smaller-scale facilities (<1 MW), suggesting their development is directly linked to the immediate presence of electricity demand. Conversely, higher-capacity facilities (>10 MW) end to be located in peri-urban and rural areas. This deployment pattern likely reflects the requirement for large land extensions and lower urban development pressure.

Additionally, this dual distribution pattern may suggest that the location of PV facilities, while multifactorial, is influenced by the interplay between the location of major consumption centres and surface area availability. The growth of smaller-scale facilities is likely tied to the characteristics of urban and peri-urban areas, which also harbour the highest electricity demand due to population density.

However, in the absence of more precise facility geolocation data, as well as more advanced statistical techniques, these hypotheses cannot be stated categorically. Instead, they constitute a new avenue for future research.

Finally, future research should build upon this initial characterization. This necessitates a continued effort to expand and update the facilities database according to the study year. Furthermore, it is essential to broaden the variables considered beyond land uses by incorporating socioeconomic or demographic factors. Analysing these variables could help indicate potential distributions based on elements such as household income or the economic activity profile of each municipality. Simultaneously, it would be beneficial to consider other types of statistical regression models to more accurately comprehend and forecast the complex distribution of PV facilities across the Spanish territory.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/solar5040058/s1, Table S1: Moran’s Index results by power category.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.d.J.; methodology, I.d.J.; software, I.d.J.; validation, C.H.-G. and A.P.-G.; formal analysis, I.d.J.; investigation, I.d.J., C.H.-G. and A.P.-G.; resources, A.P.-G.; data curation, C.H.-G.; writing—original draft preparation, I.d.J.; writing—review and editing, C.H.-G. and A.P.-G.; visualization, I.d.J.; supervision, C.H.-G. and A.P.-G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available at Supplementary Materials.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PV | Photovoltaic |

| EIS | Environmental Impact Statement |

| EIA | Environmental Impact Assessment |

References

- Smil, V. Energía y Civilización. Una Historia, 3rd ed.; Arpa: Barcelons, Spain, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Coronel, A. Ecología política de la frontera. Las membranas del metabolismo capitalista. Daimon 2022, 87, 83–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer-Kowalski, M.; Hüttler, W. Society’s Metabolism. J. Ind. Ecol. 1998, 2, 107–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, B.; York, R. Carbon metabolism: Global capitalism, climate change, and the biospheric rift. Theory Soc. 2005, 34, 391–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer-Kowalski, M.; Haberl, H. El metabolismo socieconómico. Ecol. Política 2000, 19, 21–33. [Google Scholar]

- González de Molina, M.; Toledo, V.M. Metabolismos, Naturaleza e Historia. In Hacia una Teoría de las Transformaciones Socioecológicas, 1st ed.; Icaria: Madrid, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Durán, R.; Reyes, L. En la Espiral de la Energía, 2nd ed.; Libros en Acción: Madrid, Spain, 2018; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Malm, A. Capital Fósil, 1st ed.; Capitán Swing: Masris, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Aksoy, M.H.; Ispir, M. Techno-economic feasibility of different photovoltaic technologies. Appl. Engi. Lett. 2023, 8, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IDAE. Balances Energéticos (1990–2023). Estadísticas y Balances Energéticos de España. 2024. Available online: https://www.idae.es/informacion-y-publicaciones/estudios-informes-y-estadisticas/estadisticas-y-balance-energetico (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Enerdata. World Energy & Climate Statistics—Yearbook 2025. 2025. Available online: https://www.enerdata.net/ (accessed on 4 September 2025).

- Coronas, S.; de la Hoz, J.; Alonso, À.; Martín, H. 23 Years of Development of the Solar Power Generation Sector in Spain: A Comprehensive Review of the Period 1998–2020 from a Regulatory Perspective. Energies 2022, 15, 1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- REE. Portal ESIOS. Balance Energético Nacional. 2024. Available online: https://www.esios.ree.es/es (accessed on 20 February 2024).

- APPA Autoconsumo. Informe Anual del Autoconsumo Fotovoltaico. 2023. Available online: https://www.informeautoconsumo.es/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Informe-Autoconsumo-Fotovoltaico-2023.pdf (accessed on 22 May 2025).

- Huber, M.T.; McCarthy, J. Beyond the subterranean energy regime? Fuel, land use and the production of space. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2017, 42, 655–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio para la Transición Ecológica y el Reto Demográfico. Registro Administrativo de Instalaciones de Producción de Energía Eléctrica (RAIPRE). 2024. Available online: https://www.miteco.gob.es/es/energia/energia-electrica/electricidad/energias-renovables/registro-administrativo.html (accessed on 24 September 2024).

- Ministerio de Industria Energía y Turismo. Real Decreto 413/2014, de 6 de Junio, por el Que se Regula la Actividad de Producción de Energía Eléctrica a Partir de Fuentes de Energía Renovables, Cogeneración y Residuos; BOE Núm. 140 de 10 de Junio de 2014; Ministerio de Industria Energía y Turismo: Madrid, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y. New Approaches for Calculating Moran’s Index of Spatial Autocorrelation. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e68336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).