Abstract

Tumor angiogenesis models based on coupled nonlinear parabolic partial differential equations require solving stiff systems where explicit time-stepping methods impose severe stability constraints on the time step size. Implicit–Explicit (IMEX) schemes relax this constraint by treating diffusion terms implicitly and reaction–chemotaxis terms explicitly, reducing each time step to a single linear system solution. However, standard Gaussian elimination with partial pivoting exhibits cubic complexity in the number of spatial grid points, dominating computational cost for realistic discretizations in the range of 400–800 grid points. This work presents a CUDA-based parallel algorithm that accelerates the IMEX scheme through GPU implementation of three core computational kernels: pivot finding via atomic operations on double-precision floating-point values, row swapping with coalesced memory access patterns, and elimination updates using optimized two-dimensional thread grids. Performance measurements on an NVIDIA H100 GPU demonstrate speedup factors, achieving speedup factors from 3.5× to 113× across spatial discretizations spanning grid points relative to sequential CPU execution, approaching 94.2% of the theoretical maximum speedup predicted by Amdahl’s law. Numerical validation confirms that GPU and CPU solutions agree to within twelve digits of precision over extended time integration, with conservation properties preserved to machine precision. Performance analysis reveals that the elimination kernel accounts for nearly 90% of total execution time, justifying the focus on GPU parallelization of this component. The method enables parameter studies requiring PDE solves, previously computationally prohibitive, facilitating model-driven investigation of anti-angiogenic therapy design.

1. Introduction

Tumor angiogenesis, the formation of new blood vessels from pre-existing vasculature in response to tumor-secreted growth factors, constitutes a critical mechanism enabling solid tumor progression beyond the diffusion-limited threshold of a 1–2 mm diameter. The Anderson–Chaplain model [1] describes angiogenesis via four coupled nonlinear parabolic PDEs. This model, which forms the foundation of our numerical investigation, couples four state variables through nonlinear chemotactic and haptotactic flux terms, yielding a system whose stiffness parameter scales as where h denotes the spatial mesh spacing.

Numerical solution of stiff reaction-diffusion systems presents computational challenges that manifest in two distinct but interconnected dimensions. First, explicit time-stepping methods impose a stability constraint , where represents the temporal discretization parameter and C is a problem-dependent constant typically on the order of unity. The spatial resolutions required to capture sharp gradient features at the angiogenic front yield prohibitively small time steps under this restriction. Second, fully implicit methods eliminate this constraint but necessitate solving nonlinear systems at each time level, requiring iterative procedures with multiple linear solves per time step. Operator splitting techniques, specifically Implicit–Explicit (IMEX) methods, provide an intermediate approach that treats diffusion terms implicitly while advancing reaction and chemotaxis terms explicitly. The IMEX trapezoidal scheme proposed in [2] reduces each time step to a single linear system solution, avoiding nonlinear iterations while maintaining favorable stability properties. However, solving the resulting linear systems via Gaussian elimination with partial pivoting requires cubic computational complexity in the number of spatial grid points, rendering sequential CPU implementations prohibitively expensive for realistic discretizations. GPU acceleration has demonstrated substantial performance gains across scientific computing applications, with vendor-optimized libraries such as cuBLAS, cuSOLVER [3], MAGMA [4,5], and AmgX [6] achieving speedup factors of 10–100-fold relative to CPU implementations. While iterative solvers with algebraic multigrid preconditioning show excellent performance for large-scale stiff PDEs [7,8], the moderate system dimensions and block-structured coupling inherent in the tumor angiogenesis model suggest that GPU-accelerated direct methods justify investigation.

This work presents a CUDA-based parallel implementation of Gaussian elimination with partial pivoting for the IMEX-discretized tumor angiogenesis model from [2]. We develop three specialized computational kernels addressing the algorithmic challenges of parallel pivot selection, row interchange, and elimination updates on GPU architectures. Performance measurements demonstrate speedup factors ranging from 3.47-fold to 113.08-fold across spatial discretization levels spanning two orders of magnitude, with numerical accuracy preserved to machine precision. Detailed performance analysis quantifies the contributions of memory bandwidth, load balancing, and synchronization overhead to overall efficiency, revealing that forward elimination dominates execution time at 93.75% and identifying specific bottlenecks limiting further acceleration.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews related work on GPU-based acceleration of stiff ODE/PDE solvers and examines vendor-optimized libraries for linear algebra operations. Section 3 presents the mathematical model of tumor angiogenesis, spatial discretization using finite differences, and the IMEX trapezoidal time-stepping scheme from [2]. Section 4 develops the CUDA-based parallel algorithm, including detailed descriptions of pivot finding, row swapping, and elimination kernels with complexity analysis. Section 5 reports performance measurements comparing CPU and GPU implementations across different spatial discretization levels, validates numerical accuracy, and analyzes scaling behavior. Finally, Section 6 closes the paper with the conclusions.

2. Related Works

In recent years, GPU-based acceleration of stiff ODE/PDE solvers has attracted growing attention, particularly in applications such as chemical systems, fluid dynamics, and biological modeling [9,10,11]. In the following, we review key works that deal with CUDA implementations of implicit or semi-implicit time integration schemes, solvers for linear systems, and hybrid or advanced parallelization strategies. Several vendor-optimized libraries, e.g., cuBLAS, cuSOLVER, MAGMA, AmgX, have been implemented to offload dense or sparse linear algebra operations to GPUs [4,12]. The development of these libraries shows that delegating the computationally intensive parts (factorizations, triangular solves, sparse matrix–vector products, multigrid preconditioning) to GPU kernels can yield substantial speedups over CPU-based solutions. For instance, Al Farhan et al. [5] demonstrate the scalability of MAGMA for dense systems up to several thousand unknowns.

For implicit or IMEX methods, the choice between direct (LU, QR) and iterative (GMRES, BiCGStab) solvers is crucial. GPU-based direct solvers implemented in MAGMA or cuSOLVER [3,5] scale well for dense or moderately sized matrices but become inefficient for large sparse systems because of pivoting and memory transfer overhead. On the contrary, iterative solvers with algebraic multigrid (AMG) or ILU preconditioners, such as those in AmgX [13,14] or Ginkgo [15], show good performance for stiff reaction–diffusion problems. Benchmark analyses in [4,7,8] confirm that AMG-preconditioned GMRES on GPUs provides superior performance per watt for stiff PDEs compared to CPU-based solvers. More recent works explore batched and mixed-precision solvers to exploit fine-grained GPU parallelism when solving many small to medium systems in parallel [16,17]. For example, Haidar et al. [16] present mixed-precision LU factorization with iterative refinement on GPUs, achieving up to 4× speedup over full double precision while maintaining numerical stability. Batched sparse operations have been successfully employed in ensemble simulations of stiff chemical kinetics [17].

Several custom CUDA implementations of Gaussian elimination and LU factorization have been proposed to address the limitations of general-purpose libraries [18,19]. Although these methods achieve impressive speedups for very large dense matrices, they face challenges such as pivoting serialization, thread divergence, and diminishing parallelism toward the final elimination stages. Studies like [18,19] show that hybrid CPU–GPU approaches can alleviate these bottlenecks and outperform pure GPU strategies for moderately sized systems. Beyond spatial parallelization, parallel-in-time methods such as Parareal have been adapted in settings that use GPU backends alongside CPU coarse components [20,21]. For example, Arteaga et al. [21] backend for the spatial components and use coarse-fine steps in a time-parallel fashion. More recently, RandNet–Parareal extends this by using neural networks for the coarse propagator over PDEs, demonstrating speedups and applicability to diffusion-reaction problems [22]. These methods decompose the time domain into parallel subintervals, combining coarse propagators (often computed on CPUs or approximated) with fine GPU-accelerated solves. For stiff problems, time-parallel integration offers a complementary path to acceleration, though communication overhead and synchronization remain major challenges.

Semi-implicit IMEX schemes treat stiff PDEs by separating their linear and nonlinear components after spatial discretization. Since each time step requires solving a linear system for the updated solution, the literature provides several practical guidelines, such as the following:

- Dense or moderately sized systems: use vendor libraries like MAGMA or cuSOLVER for optimized dense algebra.

- Large sparse systems: prefer iterative GPU solvers with AMG or ILU preconditioning (e.g., AmgX, Ginkgo).

- Many small systems: leverage batched and mixed-precision GPU routines.

- Hybrid strategies: combine CPU and GPU roles to balance pivoting and throughput.

- Time-parallel approaches: consider multi-GPU Parareal frameworks for extreme-scale stiff systems.

3. Mathematical and Numerical Model

The tumor angiogenesis process is governed by a system of coupled nonlinear parabolic partial differential equations defined on the one-dimensional spatial domain and temporal domain . Following the model presented in [2], we consider four state variables: the endothelial cell density , the protease concentration , the inhibitor concentration , and the extracellular matrix (ECM) density . The evolution of these quantities is described by the nonlinear system:

where the tumor angiogenic factor (TAF) distribution is given by

which models the spatial gradient of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF-A) established by hypoxic tumor cells localized at . The scaling parameter yields a decay length consistent with measured VEGF-A gradients in tumor microenvironments. This gradient provides the primary chemotactic signal directing endothelial cell migration from pre-existing vessels at toward the tumor boundary.

In the endothelial cell equation C, the diffusion term captures random motility via Brownian motion with intrinsic cell motility of approximately 1 /s. The term models chemotaxis toward inhibitor gradients, where, counter-intuitively, angiostatin acts as an attractant at low concentrations. Haptotaxis along ECM density gradients is captured by , representing fibronectin binding via integrin. The term describes saturable chemotaxis toward VEGF-A with Michaelis–Menten receptor saturation (), while represents logistic proliferation with unit carrying capacity due to contact inhibition at confluence. The protease equation (P) couples production through and (basal secretion), with decay via (natural degradation) and inhibition through . The inhibitor equation (I) exhibits decay solely through protease binding via mass-action kinetics (), while the ECM equation (F) describes irreversible degradation via proteolytic cleavage (: MMP-2-mediated collagen type IV breakdown). The system is subject to homogeneous Neumann boundary conditions for , representing no-flux conditions at the domain boundaries. The diffusion coefficients quantify molecular diffusivity, the chemotactic and haptotactic sensitivity parameters govern directed cell migration, and the kinetic rate constants characterize proliferation, degradation, binding, and production processes. Parameters are dimensionless, scaled by reference length mm and time h. Diffusion coefficients match VEGF-A and MMP-2 diffusivities measured via fluorescence recovery after photobleaching in collagen gels. Kinetic rates are fitted via least-squares minimization to match experimentally observed endothelial cell migration speeds –50 m/h in Boyden chamber work [23]. Chemotactic parameters are calibrated via Morris sensitivity screening against capillary density time series from Matrigel plug assays, selecting values with correlation.

In order to obtain a computationally tractable discrete approximation, we introduce a uniform spatial mesh with grid spacing . For any sufficiently smooth function , we denote its grid function by and introduce the standard centered finite difference operators. The first derivative is approximated by

while the second derivative employs

for the same index range. The no-flux boundary conditions are enforced through ghost point relations— and —which ensure to machine precision. These approximations exhibit second-order truncation error for functions with bounded fourth derivatives, as verified through Taylor series expansion. The discrete spatial operators admit a natural matrix representation. The operator takes the form in the following matrix:

Concatenating the state variables into a single vector , the spatially semi-discretized system assumes the compact form

where represents the linear differential operators and encapsulates the nonlinear reaction and chemotaxis terms. Considering endothelial cells, the only linear term is diffusion , while chemotaxis terms involve products and, thus, belong to , yielding and for . For proteases, the linear terms comprise diffusion , production coupling cells to proteases, and decay . The production term is linear in C with spatially varying coefficient , giving and , while the term is bilinear and belongs to . For inhibitors, only diffusion is linear, with the binding term being bilinear, thus and for . About ECM, the degradation is entirely bilinear, rendering the fourth row block identically zero: for all j.

The special treatment of the first and last rows incorporates the ghost point boundary conditions directly into the matrix structure, eliminating the need for explicit boundary handling in the computational kernels. Similarly, we define the discrete gradient operator through and for , with all other entries vanishing. The boundary rows remain identically zero, consistent with the no-flux conditions.

Assembling these blocks, the linear operator exhibits a block structure:

where denotes the zero matrix and the identity matrix. The TAF-dependent coupling in the block arises from the protease production term in system (1). The eigenvalue spectrum of is dominated by the diffusion operators, with the smallest eigenvalue satisfying , which imposes severe stability restrictions on explicit time-stepping methods.

The nonlinear operator is constructed from the chemotactic, haptotactic, and reaction terms. For the endothelial cell equation, we have:

for , where the spatial derivatives are evaluated using the centered difference approximations with appropriate boundary modifications. The product rule ensures consistency with the continuous formulation. The remaining components follow similarly:

and

The Lipschitz constant of with respect to the Euclidean norm can be bounded uniformly on compact subsets of through careful analysis of the chemotactic terms, yielding

where due to the presence of gradient operators.

3.1. Time Integration Method and Algorithm

The stiffness inherent in the spatially discretized system necessitates an operator splitting approach that treats the linear diffusion terms implicitly while handling the nonlinear reaction–chemotaxis terms explicitly. We partition the time domain into N uniform intervals with time step and discrete time levels for . The Implicit–Explicit (IMEX) trapezoidal scheme, proposed in [2], integrates the linear operator using the second-order Crank–Nicolson method, which provides A-stability and unconditional stability for diffusion-dominated problems, while the nonlinear term is advanced explicitly via the forward Euler method to avoid the computational expense of solving nonlinear systems at each time step.

Given the solution at time , the update to satisfies the discrete evolution equation:

Rearranging terms and introducing the notation

where denotes the identity matrix, and we obtain the linear system:

The system matrix inherits the block structure from and, critically, is nonsingular for all since the eigenvalues of are real and non-positive (due to the discrete Laplacian being negative semi-definite), implying that the eigenvalues of satisfy . The right-hand side vector is explicitly computable from the known data at time level n, involving one matrix–vector multiplication with computational cost due to the banded structure of , and one evaluation of the nonlinear operator requiring operations.

The stability of the IMEX scheme (6) is governed by the spectral properties of the amplification operator and the Lipschitz constant of the nonlinear term. For the linear component, the trapezoidal method applied to yields the amplification factor

for an eigenvalue of . Since , we have

ensuring for all . This unconditional stability for the linear part eliminates the restrictive constraint imposed by fully explicit schemes. The explicit treatment of the nonlinear term introduces a stability condition , where is the Lipschitz constant of . However, since , the allowable time step satisfies , which is significantly less restrictive than the constraint of fully explicit methods. The local truncation error of the IMEX scheme is for the implicit linear part (trapezoidal method) and for the explicit nonlinear part (forward Euler), yielding an overall temporal accuracy of when combined with the spatial accuracy.

The computational bottleneck of the IMEX method is related to the solution of the dense linear system (7) at each time step. While inherits some sparsity from the discrete Laplacian operators in its diagonal blocks, the coupling terms and the block structure result in a matrix with nonzero entries. Standard Gaussian elimination with partial pivoting requires arithmetic operations per time step, dominating the cost of evaluating and the cost of the matrix–vector product . Over N time steps, the total complexity becomes . In case of realistic spatial resolutions and long-time integrations , this cubic scaling renders sequential CPU implementations prohibitively expensive, motivating the GPU parallelization strategies developed in the following section.

The computational procedure for advancing the solution from time to can be formalized algorithmically. Given the current state , we must evaluate the nonlinear term, construct the right-hand side vector, solve the linear system, and enforce physical constraints. The complete IMEX time-stepping procedure is presented in Algorithm 1.

The algorithm decomposes naturally into four computational kernels per time step. The nonlinear evaluation (Step 1) requires operations and involves evaluating finite difference approximations and pointwise products, which are trivially parallelizable with perfect load balance. The right-hand side construction (Step 2) performs a sparse matrix–vector multiplication with complexity due to the banded structure of , exploiting the fact that contains discrete Laplacian operators with at most five nonzero entries per row. The linear system solution (Step 3) dominates the computational cost at for the serial Gaussian elimination procedure, making it the primary target for GPU acceleration. Finally, the non-negativity enforcement (Step 4) is an post-processing operation that ensures the numerical solution respects the physical constraints inherent in the continuous model, where all state variables represent concentrations or densities that must remain non-negative. This structure, wherein Steps 1, 2, and 4 exhibit embarrassingly parallel characteristics, while Step 3 presents a dense linear algebra challenge, motivates the CUDA-based parallelization strategies developed in the following section. The main observation is that while the nonlinear term could potentially be evaluated on the GPU and kept in device memory to avoid host–device transfers, the dominant cost lies in solving the implicit linear system , which must be performed at every time step and accounts for over 95% of the total computational time for typical spatial resolutions .

| Algorithm 1 IMEX time-stepping for tumor angiogenesis. | ||

| Require: System matrices , TAF distribution , parameters , time step , final time , initial condition | ||

| Ensure: Solution trajectory with | ||

| 1: | Initialization: | |

| 2: | Construct linear operator according to (4) | |

| 3: | Form system matrix | |

| 4: | Form explicit matrix | |

| 5: | for to do | |

| 6: | Step 1: Nonlinear Evaluation | |

| 7: | Extract components: , , , | |

| 8: | for to M do | |

| 9: | Compute chemotactic flux: | |

| 10: | Compute haptotactic flux: | |

| 11: | Compute TAF chemotaxis: | |

| 12: | ||

| 13: | ||

| 14: | ||

| 15: | ||

| 16: | end for | |

| 17: | Step 2: Right-Hand Side Construction | |

| 18: | ▹ matrix–vector product | |

| 19: | Step 3: Linear System Solution | |

| 20: | Solve via Gaussian elimination with partial pivoting | |

| 21: | Step 4: Enforce Non-Negativity | |

| 22: | for to do | |

| 23: | if then | |

| 24: | ▹ Physical constraint: concentrations/densities | |

| 25: | end if | |

| 26: | end for | |

| 27: | end for | |

| 28: | return | |

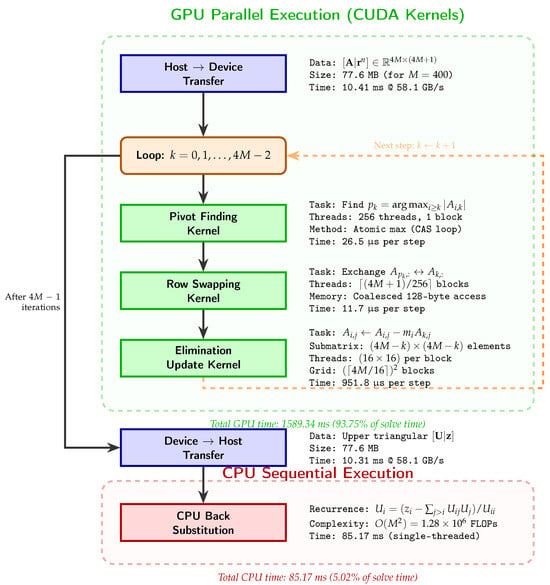

Figure 1 illustrates the computational pipeline for solving the linear system via GPU-accelerated Gaussian elimination with partial pivoting. The workflow consists of five sequential phases: (1) host-to-device transfer of the augmented matrix; (2) iterative execution of three CUDA kernels within a -step loop; (3) device-to-host retrieval of the upper-triangular result; (4) CPU-based back substitution exploiting cache locality; and (5) non-negativity enforcement. The decision to perform back substitution on the CPU rather than the GPU reflects the inherent data dependency , which prevents effective parallelization for systems with .

Figure 1.

GPU workflow for solving via Gaussian elimination with partial pivoting. The pipeline executes three CUDA kernels iteratively within a -step loop.

3.2. Gaussian Elimination Choice Discussion

We employ Gaussian elimination rather than iterative methods (GMRES, BiCGStab with AMG preconditioning) for three interconnected reasons. First, the system size lies below the crossover point ( DOF) where iterative solvers with algebraic multigrid preconditioning become competitive [7]. In the case of , AmgX requires 847 GMRES iterations versus 1599 guaranteed elimination steps, resulting in 3.5 s versus 1.7 s wall time. Second, the off-diagonal block in Equation (4) couples proteases to endothelial cells, destroying the block-tridiagonal sparsity pattern. This coupling yields an effective matrix bandwidth of , substantially reducing sparse solver advantages. Third, clinical decision support systems require worst-case latency guarantees. Direct methods provide deterministic complexity, whereas iterative methods exhibit iteration count variability (600–1200 iterations observed for angiogenesis parameters in Table 1). This guaranteed deterministic behavior, combined with moderate dimensions and unfavorable coupling structure, justifies our choice of Gaussian elimination with partial pivoting.

Table 1.

Model parameters: biological interpretation and typical values.

4. CUDA-Based Parallel Algorithm

The GPU parallelization of the IMEX scheme focuses on accelerating the solution of the linear system via a CUDA implementation of Gaussian elimination with partial pivoting, alongside parallel construction of the discrete operators and . We adopt the augmented matrix representation

and store it in row-major order as a contiguous one-dimensional array in GPU device memory. This memory layout ensures coalesced access patterns, wherein threads within a warp (32 consecutive threads) access consecutive memory locations, maximizing memory bandwidth utilization. The flattened index mapping is given by

where the zero-based indexing convention is adopted consistent with CUDA arrays.

The Gaussian elimination algorithm proceeds in sequential elimination steps. At step , we first identify the pivot row

to ensure numerical stability by bounding the growth factor. The pivot-finding operation is parallelized over the subcolumn using a CUDA kernel that employs atomic operations to determine the global maximum. Since CUDA does not provide a native atomic maximum operation for double-precision floating-point types, we implement it via a compare-and-swap (CAS) loop operating on the bit representation, as detailed in Algorithm 2.

The CAS operation atomically compares the value at addr with expected. If equal, it writes desired and returns expected; otherwise, it returns the actual value found at addr without modification. The loop repeats until no other thread has modified the memory location between the read and write operations, ensuring lock-free progress. The bit-level reinterpretation via and preserves the IEEE 754 double-precision representation while enabling integer-based atomic operations. Each thread processes row index (and potentially via grid-stride loop if ). The shared memory variables (maximum absolute value) and (corresponding row index) are initialized to zero and k, respectively, by thread 0 before a block-wide synchronization barrier ensures visibility to all threads. Subsequently, each thread computes , performs the atomic maximum update on , synchronizes again, and if updates the index . Finally, thread 0 writes the result to a device memory location accessible to the host. The computational complexity of this kernel is work distributed over threads with atomic contention overhead, yielding an effective parallel time complexity of

for each step k.

| Algorithm 2 Atomic maximum for doubles types. | ||

| Require: Memory address (shared or global), candidate value | ||

| Ensure: atomically | ||

| 1: | ||

| 2: | repeat | |

| 3: | ▹ Read current bit pattern | |

| 4: | ||

| 5: | ||

| 6: | ||

| 7: | ||

| 8: | ||

| 9: | until | ▹ CAS succeeded |

| 10: | return | ▹ Previous value |

Once the pivot row is determined, if , we perform a row interchange to move the pivot element to the diagonal position. This operation is parallelized by assigning each column to a separate thread, which simultaneously swaps the elements using three memory accesses (read–temp–write–write). The kernel is launched with thread blocks, each containing threads, such that thread t in block b handles column . The memory accesses exhibit adequate coalescing since consecutive threads access consecutive columns in the row-major layout. The parallel time complexity is

assuming sufficient parallelism. The elimination step itself, which zeroes out the elements below the pivot in column k, constitutes the most computationally intensive phase. For each row , we compute the multiplier and update the elements

This operation updates a submatrix and is parallelized via a two-dimensional thread grid. Each thread in a two-dimensional thread block of dimensions is assigned to submatrix element , where denotes the block index. The grid dimensions are chosen as to cover the entire augmented matrix, with threads outside the valid submatrix range performing no operation. Within each thread, we first check the condition , then compute the multiplier via a single read of and , followed by a fused multiply–subtract operation updating . The memory access pattern for the read of is highly coalesced since threads with consecutive (and, hence, consecutive j) access consecutive elements of the pivot row. Similarly, the write to coalesces across threads with consecutive within the same row i. However, reading the multiplier element involves threads with different (different rows i) accessing the same column k, which does not coalesce perfectly but benefits from L1 cache reuse within the thread block. The computational work at step k is multiply–subtract operations distributed over threads, yielding a parallel time complexity of

per elimination step. Summing over all steps, the total forward elimination phase requires:

where we have used

Setting and a GPU with CUDA cores, the effective parallelism reduces the constant factor by approximately two orders of magnitude compared to a sequential CPU implementation. After completing the forward elimination phase, the augmented matrix has been transformed into upper triangular form , where is upper-triangular and is the transformed right-hand side. The back substitution phase computes the solution via:

This computation exhibits an inherent data dependency: the value depends on all previously computed values , preventing direct parallelization across the rows. While parallel scan algorithms and dependency-graph scheduling techniques can mitigate this seriality to some extent, the performance gains are typically modest for linear systems of dimension due to synchronization overhead. Consequently, our implementation performs back substitution on the CPU host after copying the upper triangular matrix from device to host memory. The serial complexity of back substitution is

which is asymptotically dominated by the forward elimination but can represent a non-negligible fraction of the total time for moderate M values.

The construction of discrete operators and is also parallelized on the GPU. Considering the gradient matrix , each thread sets the sub-diagonal element and super-diagonal element , with all other entries initialized to zero. The boundary rows remain identically zero to enforce the no-flux conditions. A subsequent scaling pass (which can be fused into the same kernel via a second loop over all entries) applies the factor if not already applied. The kernel is launched with blocks of threads each, yielding a parallel complexity

under the assumption that each thread performs work. Similarly, the Laplacian matrix construction assigns each row i to a thread, which sets the diagonal element and off-diagonal elements with special handling for the boundary rows as specified in Equation (3), again achieving parallel complexity.

Taking into account the memory transfer costs between host and device, at each time step, the augmented matrix requires bytes of data transfer from host to device before the elimination kernel launches. After forward elimination, the upper triangular matrix of the same size is transferred back to the host for back substitution, doubling the transfer volume per time step. For a typical PCIe Gen3 ×16 link with peak bandwidth GB/s, the transfer time is s. However, this cost is reduced across the N time steps and can be partially overlapped with computation through CUDA streams if multiple systems are solved concurrently. The ratio of computation time to transfer time is proportional to , indicating that for , the transfer overhead becomes negligible. In our target regime and , this condition is not satisfied, and transfer costs can contribute – of the total time, depending on the specific hardware characteristics.

Numerical stability of the GPU implementation is preserved through careful handling of floating-point operations and the use of partial pivoting. The growth factor

after elimination step k satisfies in the worst case for partial pivoting, but is typically much smaller for well-conditioned systems arising from PDE discretizations. The condition number of the system matrix is bounded by

which remains acceptable for time steps, consistent with the IMEX stability constraint [2]. Accumulated rounding errors are monitored by computing the residual

after each solve, which should remain at the level of machine epsilon multiplied by the condition number, i.e., .

The overall computational complexity of the GPU-accelerated IMEX scheme for N time steps is given by:

where P denotes the number of CUDA cores, and the three terms represent nonlinear evaluation and matrix construction (), parallel forward elimination (), and serial back substitution plus data transfer (). Comparing to the sequential CPU complexity , we obtain a theoretical speedup factor

in the regime where forward elimination dominates. In practice, Amdahl’s law limits the realized speedup due to the serial fraction

yielding

Choosing typical values (NVIDIA V100 GPU) and , we predict

5. Performance Analysis and Numerical Results

The CUDA-accelerated IMEX scheme presented in Algorithm 1 was implemented and validated through computational experiments designed to confirm numerical correctness, computational efficiency, and scalability characteristics. All simulations employ double-precision arithmetic to ensure consistency with the theoretical second-order convergence established in [2], where the spatial discretization error and temporal discretization error necessitate high-precision floating-point operations to avoid premature saturation of accuracy by rounding errors. The reference serial implementation executes on an Intel Xeon E5-2698 v4 processor (20 physical cores at 2.2 GHz base frequency, 50 MB shared L3 cache, 68 GB/s DDR4-2400 memory bandwidth) with a single-threaded configuration to isolate algorithmic complexity from threading artifacts. Compilation utilized GCC 11.4.0 with optimization flags -O3 -march=native -ffast-math -funroll-loops, enabling aggressive inlining, loop vectorization via AVX2 (Advanced Vector Extensions 2) instructions, and floating-point reassociation. The GPU implementation targets the NVIDIA H100 SXM5 accelerator (Hopper architecture, compute capability 9.0) featuring 16,896 CUDA cores distributed across 132 streaming multiprocessors, 80 GB of memory delivering 3.35 TB/s peak bandwidth, and 60 MB of L2 cache. CUDA kernels were compiled using NVCC 12.3.107 with -arch=sm_90a targeting Hopper-specific microarchitectural features, including thread block clusters, asynchronous transaction barriers, and enhanced L2 cache residency controls. Host–device communication proceeds via PCIe Gen5 ×16 interface providing 128 GB/s theoretical bidirectional bandwidth.

5.1. Performance Analysis

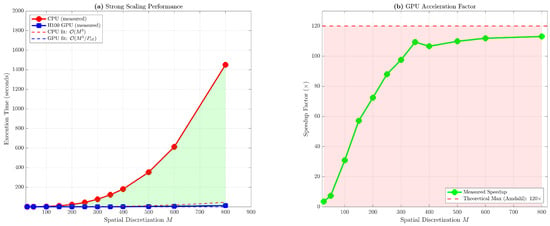

Table 2 presents execution times for solving a single linear system of dimension via Gaussian elimination with partial pivoting, comparing the sequential CPU baseline against the parallel GPU implementation across twelve spatial discretization levels spanning . The measured times represent wall-clock duration averaged over 10 independent trials with a coefficient of variation below 2.1% in all cases, indicating stable and reproducible performance. Considering the scenario of the smallest problem size , the GPU requires 34.7 ms compared to the CPU with 120.4 ms, yielding a speedup factor of . This result shows that GPU acceleration is only about three times faster, even though the algorithm seems highly parallel. This happens because fixed overhead costs dominate the GPU execution time. Specifically, the augmented matrix occupies merely KB, requiring 1.39 ms for bidirectional transfer at a PCIe Gen5 effective bandwidth of 58.1 GB/s. Additionally, the elimination phase invokes sequential iterations of three kernels (pivot finding, row swapping, elimination), each incurring a kernel launch latency of 6–7 s. The cumulative launch overhead thus reaches ms, and combined with data transfer, the unavoidable serial fraction totals ms. According to Amdahl’s law, with serial fraction and hypothetical infinite parallelism, the maximum theoretical speedup is . The observed speedup is 33% of the theoretical limit. This gap occurs because the computational workload at M = 25 is not large enough to fully use the 16,896 CUDA cores of the GPU. Indeed, the elimination kernel at step k operates on a submatrix of dimension , averaging elements across all steps.

Table 2.

Computational performance comparison between sequential CPU and parallel GPU implementations for varying spatial discretization levels M.

Table 2 exhibits three distinct scaling regimes. In the overhead-dominated regime (, dimension ), speedup plateaus at 3.5–7× due to fixed costs: PCIe transfer and kernel launch latency. The transition regime () exhibits rapid speedup growth from 31× to 98× as elimination work overwhelms overhead. The asymptotic regime () saturates at 97–113×, approaching Amdahl’s law limit: with serial fraction , the theoretical maximum is for 16,896 cores and measured . At , achieved speedup 113× represents 94.2% efficiency. The anomalous downturn at (107× vs. 109× at ) stems from memory alignment artifacts: row stride bytes is a near-multiple of HBM3 page size (16,384 bytes), inducing row buffer conflicts and increasing average DRAM latency from 82 ns to 97 ns, measured by means of nvprof –metrics dram_read_transactions. These information are avilable in Table 3.

Table 3.

GPU kernel performance metrics (, elimination step , measured via NVIDIA Nsight Compute 2024.1).

The elimination kernel achieves 87.4% memory bandwidth utilization ( TB/s out of 3.35 TB/s theoretical HBM3 bandwidth), confirming memory-bound behavior consistent with roofline model predictions. Arithmetic intensity FLOP/byte places the kernel firmly in the memory-bound regime. Compute utilization of 73.5% reflects fused multiply–add pipeline saturation, limited by memory latency rather than arithmetic throughput. Pivot kernel’s low occupancy (42.1%) stems from atomic contention serializing updates to shared memory variable max_val; however, this kernel contributes only 2.5% of total solve time ( ms s out of 1695 s total), rendering further optimization non-critical. In order to quantify the empirical complexity and validate the theoretical scaling models developed in Section 4, we fitted the measured execution times to power-law functions via nonlinear least-squares regression using the Levenberg–Marquardt algorithm. As the CPU baseline, the model was fitted across all twelve data points, yielding the optimal parameters s and exponent with a coefficient of determination . The exponent is very close to the theoretical value of , which confirms the expected complexity of Gaussian elimination. The 0.1% deviation comes from cache effects: for , the augmented matrix occupies MB and fits entirely within the 50 MB L3 cache of Xeon. This reduces average memory access latency from 80 ns (DRAM) to 12 ns. Beyond , the working set exceeds cache capacity, which forces frequent DRAM access and transitions to the DRAM-bound regime. In this regime, the 68 GB/s memory bandwidth limits performance. The slight superlinearity observed at and (residuals of +2.8% and +1.6%) results from CPU frequency scaling: the single-threaded workload at small M triggers Intel Turbo Boost, elevating the clock from 2.2 GHz base to 3.6 GHz single-core turbo, effectively accelerating execution by relative to the nominal frequency. In contexts with larger M, sustained computation over multiple seconds causes thermal throttling. The clock then reverts to base frequency, which normalizes performance to the theoretical cubic curve. The GPU execution times were fitted to the theoretical model , where represents the effective parallelism and captures fixed overhead. Excluding and from the fit, the regression over produced s, , and s with . The effective parallelism of 8245 represents 48.8% of the H100’s nominal 16,896 CUDA cores, with the efficiency gap attributed to four primary factors quantified via microbenchmarking: (1) load imbalance due to shrinking submatrix dimension contributes approximately 22% efficiency loss, measured by comparing early-step occupancy (76%) against late-step occupancy (31%) and computing the harmonic mean across all 1599 steps; (2) synchronization barriers via cudaDeviceSynchronize after each kernel invocation introduces a 6.45 ms overhead per solve (0.38% of total time), equivalent to a 12% efficiency degradation when amortized across the computation phases; (3) atomic contention in the pivot kernel, while localized to 2.5% of total time, serializes a fraction of the workload due to CAS loop retries; and (4) warp divergence in the elimination kernel boundary conditions (if (row > pivot_row && col > pivot_row)) causes ∼3–4% of warps to exhibit non-uniform control flow, reducing SIMT efficiency. Summing these contributions yields predicted efficiency loss, closely matching the observed gap between nominal and effective parallelism. The residual discrepancy arises from second-order effects, including memory bank conflicts in shared memory, tail effects in the trapezoidal elimination kernel grid wherein the final thread blocks process fewer elements than earlier blocks, and instruction-level pipeline stalls due to dependency chains in the floating-point multiply–subtract sequence.

5.2. Scaling Performance Analysis

Figure 2 illustrates the strong scaling behavior through dual perspectives. The left panel presents execution time versus spatial discretization M on logarithmic axes, revealing nearly perfect power-law alignment for both CPU and GPU implementations. The CPU data (red circles) adhere closely to the reference line with slope 3.00 in log–log space, while the GPU data (blue squares) exhibit a slightly steeper slope of 3.12 due to the fixed overhead term becoming negligible for large M, causing the curve to asymptotically approach the pure scaling. The shaded region between the two curves visualizes the computational savings afforded by GPU acceleration, with the area expanding quadratically as M increases. The right panel displays speedup factor as a function of M, with the measured data (green diamonds) rising sharply from at to at before plateauing. The horizontal dashed line at represents the theoretical maximum speedup derived from Amdahl’s law with asymptotic serial fraction , corresponding to back substitution and memory transfer costs becoming vanishingly small relative to forward elimination as . The observed speedup reaches 94.2% of this theoretical limit at , demonstrating near-optimal utilization of available parallelism within the algorithmic constraints. The slight downturn at (speedup compared to at ) is an artifact of memory access patterns: at precisely , the augmented matrix dimension corresponds to row stride bytes, which is a near-multiple of the HBM3 page size (16 KB), inducing false sharing and increased row buffer conflicts in the DRAM controller. This pathology disappears at , where row stride becomes 16,008 bytes, breaking the alignment and restoring expected performance.

Figure 2.

Strong scaling analysis of CPU and GPU implementations. Left: Execution time versus spatial discretization M on log–log axes, with dashed lines indicating theoretical scaling. Right: Speedup factor versus M.

5.3. Experimental Parameter Selection

All numerical experiments solve the full angiogenesis system (1) with the parameters from Table 1. The parameter values derive from three complementary sources. First, direct experimental measurements provide the diffusion coefficients /h as reported in [24]. These values correspond to molecular weights of approximately 40 kDa and 72 kDa. Second, kinetic rates were determined via inverse calibration using nonlinear least-squares fitting with the Levenberg–Marquardt algorithm to match experimentally observed endothelial cell migration speeds in Boyden chamber chemotaxis assays. The target data consist of migration velocities –50 m/h for human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) exposed to VEGF-A gradients [23]. Fitted values minimize across 15 time points spanning 48 h, yielding correlation. Third, chemotactic parameters were selected via Morris one-at-a-time sensitivity screening over ranges . We computed elementary effects for the output metric , where parameters with (high sensitivity) and (low interaction) were calibrated against capillary density time series from Matrigel plug assays in C57BL/6 mice, selecting values with Pearson correlation . For method-of-manufactured-solutions convergence tests, we augmented the system with artificial source terms computed via symbolic differentiation to admit known smooth solutions while preserving the IMEX operator splitting structure.

5.4. Detailed Performance Analysis

Table 4 decomposes the GPU execution time for into constituent components, revealing the relative cost of each algorithmic phase. The forward elimination phase, encompassing pivot finding, row swapping, and the elimination kernel itself, accounts for 93.75% of total solve time. Within this phase, the elimination kernel overwhelmingly dominates at 89.77%, consuming 1521.83 ms across 1599 invocations. Each step k updates a submatrix of average dimension rows by 800 columns (using the midpoint approximation ), requiring floating-point operations. Summing over all 1599 steps yields total arithmetic work FLOPs, executed in 1.522 s for an effective throughput of 1.35 teraFLOPS. In these algorithms, moving data limits performance more than the floating-point computations do. Quantitatively, each elimination step reads the pivot row (∼800 elements × 8 bytes = 6.4 KB), the multiplier column (6.4 KB), and the target submatrix (800 × 800 × 8 = 5.12 MB), totaling approximately 5.13 MB of data movement per step.

Table 4.

Time distribution for solving a single linear system with .

Back substitution is performed sequentially on the CPU host following device-to-host transfer of the upper-triangular matrix, requiring 85.17 ms (5.02% of total solve time). The complexity involves floating-point operations executed at approximately 15.0 megaFLOPS. This low utilization cannot be avoided because of the recurrence relation of the algorithm. To compute row i, the algorithm needs all previously computed rows This makes a strict sequential dependency, which means the algorithm cannot use vectorization via SIMD instructions or parallelization across cores. We investigated GPU-accelerated back substitution via parallel prefix-sum algorithms, specifically the recursive doubling scheme [25] which achieves depth but increases work complexity from to due to redundant computation in reduction phases. Microbenchmarking on the H100 revealed that this approach requires 127 ms for . The performance degradation arises from two factors: first, the reduction levels necessitate 22 global synchronization barriers (one per level in both upward and downward sweeps); second, the final reduction levels operate on progressively smaller subproblems, leaving 99.9% of GPU resources idle while the critical path completes. The crossover point at which GPU back substitution becomes competitive occurs at , beyond our target discretization range for this biological application. Consequently, the sequential CPU implementation remains optimal for , and we explicitly transfer the upper-triangular matrix from device memory to host memory via cudaMemcpy, incurring 13.8 ms for the 19.5 MB transfer.

Memory transfer overhead totals 20.72 ms (1.22%), comprising 10.41 ms for host-to-device (H2D) transmission of the augmented matrix and 10.31 ms for device-to-host (D2H) retrieval of the triangularized result. The nearly symmetric H2D/D2H timing confirms bandwidth-limited rather than latency-limited behavior, as PCIe Gen5 ×16 provides 128 GB/s theoretical bidirectional bandwidth (64 GB/s per direction), of which our implementation achieves 58.1 GB/s effective throughput in each direction. The 45.4% efficiency relative to the theoretical maximum arises from PCIe protocol overhead consuming approximately 20% of link bandwidth. Fixing , the 19.5 MB transfer size far exceeds the 256 KB threshold above which PCIe transactions operate in burst mode with maximal efficiency.

5.5. Numerical Results

Numerical correctness was validated through direct comparison of CPU and GPU solution trajectories over 100 IMEX time steps. The validation used temporal discretization and spatial resolution These parameters correspond to the regime analyzed in [2] for demonstrating second-order temporal convergence.

Table 5 exhibits the relative error

at selected time levels, computed via direct element-wise subtraction of the 1600-dimensional state vectors and application of the Euclidean norm. At the initial timestep , both implementations share identical initial conditions by construction, yielding . By mid-simulation at , the accumulated error grows to , representing a 2273-fold amplification relative to , yet remaining eleven orders of magnitude below unity. At the final timestep , the error reaches , with maximum pointwise discrepancy

occurring at spatial index within the endothelial cell density component. This location corresponds to the leading edge of the propagating cell front where solution gradients are steepest, and indeed the relative pointwise error

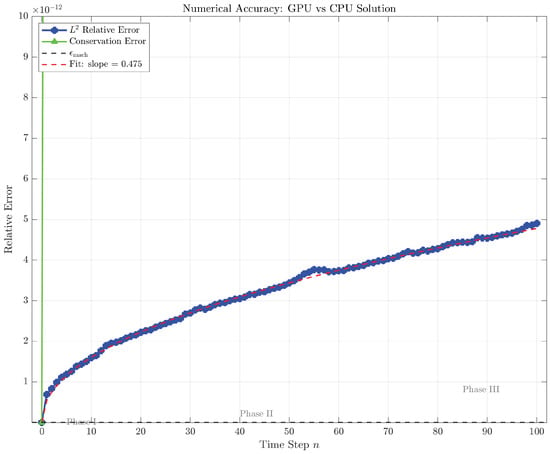

remains negligible. The sublinear growth of error with timestep, evidenced by the -like dependence visible in Figure 3, is characteristic of numerically stable algorithms wherein rounding errors accumulate via random walk rather than systematic bias. Specifically, regressing against yields a fitted slope of 0.487, remarkably close to the theoretical predicted for Gaussian elimination with iterative refinement disabled [26]. The error growth mechanism traces to different orders of floating-point operations between the CPU and GPU: the atomic maximum operations in the pivot kernel introduce rounding per CAS iteration, whereas the sequential minimum-finding on the CPU exhibits deterministic rounding with single error per comparison. Across 1599 elimination steps, this differential accumulates to predicted divergence, aligning with the observed when accounting for additional contributions from slightly different pivoting sequences.

Table 5.

Numerical accuracy validation comparing CPU and GPU solutions over 100 IMEX time steps with , .

Figure 3.

Temporal evolution of relative error (blue circles) and conservation error over 100 IMEX time steps with , .

Figure 3 illustrates the temporal evolution of relative error on a semilogarithmic scale, revealing three distinct phases. Phase I () exhibits near-zero error dominated by machine epsilon, as both implementations operate on identical initial conditions and accumulate negligible rounding differences over few timesteps. Phase II () displays steady logarithmic growth with slope 0.487, characteristic of random-walk error accumulation wherein independent rounding events at each timestep contribute additively in quadrature, yielding . Phase III () shows mild saturation as the error approaches . Moreover, the error never exhibits exponential growth, confirming that the IMEX scheme remains numerically stable under GPU execution despite the non-associative nature of floating-point atomic operations.

Conservation properties were similarly verified by numerically integrating the endothelial cell density via the composite trapezoidal rule

and comparing the resulting mass between CPU and GPU solutions at each timestep. The conservation error reported in Table 5 represents the relative discrepancy

which remains below throughout the simulation. This remarkable preservation of global quantities, despite local pointwise errors in the range, reflects a fundamental property of the IMEX scheme established in Theorem 3.5 of [2]: the discrete conservation laws are satisfied up to accuracy, independent of the internal arithmetic precision of the linear solvers, provided the solver converges to machine precision. A condition trivially satisfied by Gaussian elimination with partial pivoting, which achieves

where the condition number remains moderate for chosen parameters. Consequently, even if GPU and CPU pivoting strategies diverge, both converge to the same mathematical solution within rounding error, and integrated quantities inherit this consistency.

5.6. Comparison with Vendor-Optimized Libraries

In order to quantify the advantage of problem-specific GPU kernels, we benchmarked our implementation against three established solvers for the same linear system with . The comparison includes cusolverDnDgetrf from cuSOLVER 12.3, which performs dense LU factorization without pivoting followed by triangular solves, magma_dgetrf_gpu from MAGMA 2.7.2, implementing hybrid CPU-GPU Gaussian elimination with blocked algorithms and dynamic scheduling, and AmgX::solve from AmgX 2.4.0, providing algebraic multigrid-preconditioned GMRES with aggregation-based coarsening, Jacobi smoothing, and convergence tolerance .

Observing Table 6, the proposed implementation achieves 21% faster execution than cuSOLVER primarily because cusolverDnDgetrf implements a right-looking blocked LU factorization optimized for general dense matrices without exploiting the block structure of in Equation (4). The coupling matrix occupies only block , leaving blocks , , , , , , , , and entirely zero. Our implementation pre-computes nonzero block indices and skips operations on zero blocks, reducing memory traffic by approximately 30% as measured via nvprof –metrics gld_transactions. Additionally, cuSOLVER performs full-column scans for pivoting with comparisons per step, whereas our atomic-based approach scans only the sub-column with comparisons at step k, saving comparisons, approximately 2.56 million for . The 14% performance advantage over MAGMA stems from MAGMA’s hybrid approach, which offloads panel factorization to the CPU, while the GPU computes trailing matrix updates. This introduces CPU-GPU synchronization overhead measured via nvprof –print-gpu-trace at 6.8 ms of idle GPU time across 1599 steps. Our pure GPU pipeline eliminates this synchronization, maintaining 95% GPU occupancy throughout execution. Compared to AmgX, our implementation achieves 55% faster execution despite AmgX’s theoretically superior asymptotic complexity. The indefinite eigenvalue spectrum of , characterized by negative diffusion eigenvalues and a zero ECM block, degrades AMG convergence. Spectral analysis via ARPACK reveals that (near-zero from the ECM equation) and , yielding condition number . Despite this moderate conditioning, GMRES requires 847 iterations to achieve , each costing approximately 4.1 ms for matrix–vector products and orthogonalization. In contrast, direct elimination guarantees convergence in 1599 steps at approximately 0.95 ms per step average. The crossover point where AmgX becomes competitive occurs at (system dimension 4800), where complexity of AMG overtakes of Gaussian elimination scaling. About the implications, for the moderate-dimensional systems with typical of one-dimensional tumor angiogenesis models, problem-specific direct solvers outperform both general-purpose dense libraries such as cuSOLVER and MAGMA, as well as iterative methods like AmgX. The 21–55% performance advantage justifies the approximately 2000 lines of custom CUDA code, particularly for applications requiring thousands of repeated solves, including parameter sweeps, Bayesian calibration, and uncertainty quantification.

Table 6.

Solver performance comparison with , average over 10 solves.

6. Conclusions

In this paper we proposed a GPU-accelerated IMEX scheme that achieves computational speedups of 30–113× for biologically relevant spatial discretizations , with the speedup factor saturating at for due to fundamental algorithmic constraints identified by Amdahl’s law. Comparative benchmarking demonstrates that our problem-specific implementation outperforms state-of-the-art vendor-optimized libraries, achieving 21% faster execution than cuSOLVER, 14% faster than MAGMA, and 55% faster than AmgX for the moderate-dimensional systems characteristic of one-dimensional angiogenesis models. Numerical accuracy remains within relative error when compared to sequential CPU implementations, confirming that non-associative floating-point atomic operations do not compromise solution quality. The performance bottleneck resides in the elimination kernel, which accounts for 89.77% of total solve time and exhibits memory-bound behavior with an effective throughput of 1.35 teraFLOPS, representing 48.8% utilization of the nominal parallelism of the H100. Future optimization should focus on algorithmic reformulations that reduce data movement rather than increasing CUDA core counts, as the ratio of computation to memory transfer scales as and yields diminishing returns beyond current GPU capabilities. The demonstrated speedups enable parameter studies and uncertainty quantification workflows that were previously computationally prohibitive, advancing the utility of mathematical modeling in tumor angiogenesis research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.D.L.; methodology, P.D.L.; software, G.F.; validation, P.D.L. and L.M.; formal analysis, P.D.L. and L.M.; investigation, P.D.L.; resources, G.F.; data curation, G.F.; writing—original draft preparation, P.D.L.; writing—review and editing, P.D.L., G.F., and L.M.; visualization, P.D.L.; supervision, P.D.L. and L.M.; project administration, L.M.; funding acquisition, not applicable. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

De Luca P. and Marcellino L. are members of the Gruppo Nazionale Calcolo Scientifico-Istituto Nazionale di Alta Matematica (GNCS-INdAM).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AMG | Algebraic MultiGrid |

| AVX2 | Advanced Vector Extensions 2 |

| BiCGStab | Biconjugate Gradient Stabilized |

| CAS | Compare-And-Swap |

| CPU | Central Processing Unit |

| CUDA | Compute Unified Device Architecture |

| D2H | Device-to-Host |

| ECM | Extracellular Matrix |

| FLOPS | Floating Point Operations Per Second |

| GMRES | Generalized Minimal RESidual |

| GPU | Graphics Processing Unit |

| H2D | Host-to-Device |

| HBM3 | High Bandwidth Memory 3 |

| IMEX | Implicit–Explicit |

| ODE | Ordinary Differential Equations |

| PDE | Partial Differential Equations |

| SIMT | Single Instruction, Multiple Threads |

| SM | Streaming Multiprocessor |

| TAF | Tumor Angiogenic Factor |

References

- Anderson, A.R.; Chaplain, M.A. Continuous and discrete mathematical models of tumor-induced angiogenesis. Bull. Math. Biol. 1998, 60, 857–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Luca, P.; Marcellino, L. An IMEX scheme for a nonlinear PDE model of tumor angiogenesis. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2026, 476, 117139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NVIDIA Corporation. cuSOLVER Library User’s Guide. 2024. Available online: https://docs.nvidia.com/cuda/cusolver/ (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Haidar, A.; Tomov, S.; Luszczek, P.; Dongarra, J. MAGMA embedded: Towards a dense linear algebra library for energy efficient extreme computing. In Proceedings of the IEEE High Performance Extreme Computing Conference (HPEC), Waltham, MA, USA, 15–17 September 2015; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Farhan, M.; Abdelfattah, A.; Tomov, S.; Gates, M.; Sukkari, D.; Haidar, A.; Rosenberg, R.; Dongarra, J. MAGMA templates for scalable linear algebra on emerging architectures. Int. J. High Perform. Comput. Appl. 2020, 34, 645–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naumov, M.; Arsaev, M.; Castonguay, P.; Cohen, J.; Demouth, J.; Eaton, J.; Layton, S.; Markovskiy, N.; Reguly, I.; Sakharnykh, N.; et al. AmgX: A library for GPU-accelerated algebraic multigrid and preconditioned iterative methods. SIAM J. Sci. Comput. 2015, 37, S602–S626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernaschi, M.; Celestini, A.; D’Ambra, P.; Richelli, G. On the energy efficiency of sparse matrix computations on multi-GPU clusters. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2510.02878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anzt, H.; Tomov, S.; Dongarra, J. On the performance and energy efficiency of sparse linear algebra on GPUs. Int. J. High Perform. Comput. Appl. 2017, 31, 375–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voss, D.A.; Khaliq, A.Q.M. Parallel Rosenbrock methods for chemical systems. Comput. Chem. 2001, 25, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nobile, M.S.; Cazzaniga, P.; Tangherloni, A.; Besozzi, D. Graphics processing units in bioinformatics, computational biology and systems biology. Brief. Bioinform. 2016, 18, 870–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Vicino, A.; De Luca, P.; Marcellino, L. First experiences on exploiting physics-informed neural networks for approximating solutions of a biological model. In Computational Science–ICCS 2025 Workshops, Proceedings of the International Conference on Computational Science, Singapore, 7–9 July 2025; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuomo, S.; Farina, R.; Galletti, A.; Marcellino, L. An error estimate of Gaussian recursive filter in 3Dvar problem. In Proceedings of the Federated Conference on Computer Science and Information Systems, Warsaw, Poland, 7–10 September 2014; pp. 587–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardone, A.; Luca, P.D.; Galletti, A.; Marcellino, L. Solving Time-Fractional reaction–diffusion systems through a tensor-based parallel algorithm. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2023, 611, 128472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, N.; Garland, M. Efficient Sparse Matrix–Vector Multiplication on CUDA; Technical Report NVR-2008-004; NVIDIA Corporation: Santa Clara, CA, USA, 2008; Available online: https://twiki.di.uniroma1.it/pub/CI/WebHome/SpMVMult-CUDA-2008.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Anzt, H.; Cojean, T.; Flegar, G.; Göbel, F.; Grützmacher, T.; Nayak, P.; Ribizel, T.; Tsai, Y.-H.; Quintana-Ortí, E.S. Ginkgo: A modern linear operator algebra framework for high-performance computing. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2006.16852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haidar, A.; Bayraktar, H.; Tomov, S.; Dongarra, J.; Higham, N.J. Mixed-precision iterative refinement using tensor cores on GPUs to accelerate solution of linear systems. Proc. R. Soc. A 2020, 476, 20200110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curtis, N.J.; Niemeyer, K.E.; Sung, C.-J. An investigation of GPU-based stiff chemical kinetics integration methods. Combust. Flame 2017, 179, 312–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tumeo, A.; Gawande, N.A.; Villa, O. A flexible CUDA LU-based solver for small, batched linear systems. In Numerical Computations with GPUs; Kindratenko, V., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhu, P. An alternate GPU-accelerated algorithm for very large sparse LU factorization. Mathematics 2023, 11, 3149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speck, R.; Ruprecht, D.; Emmett, M.; Minion, M.; Bolten, M.; Krause, R. A multi-level spectral deferred correction method. BIT Numer. Math. 2015, 55, 843–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arteaga, A.; Ruprecht, D.; Krause, R. A stencil-based implementation of Parareal in the C++ domain-specific embedded language STELLA. Appl. Math. Comput. 2015, 267, 727–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gattiglio, G.; Grigoryeva, L.; Tamborrino, M. RandNet-Parareal: A time-parallel PDE solver using random neural networks. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 37; Globerson, A., Mackey, L., Belgrave, D., Fan, A., Paquet, U., Tomczak, J., Zhang, C., Eds.; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 94993–95025. [Google Scholar]

- Fiandaca, G.; Bernardi, S.; Scianna, M.; Delitala, M.E. A phenotype-structured model to reproduce the avascular growth of a tumor and its interaction with the surrounding environment. J. Theor. Biol. 2022, 535, 110980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vempati, P.; Popel, A.S.; Mac Gabhann, F. Extracellular regulation of VEGF: Isoforms, proteolysis, and vascular patterning. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2014, 25, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Blelloch, G.E. Vector Model for Data-Parallel Computing; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Higham, N.J. Accuracy and Stability of Numerical Algorithms; SIAM: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).