Abstract

This study aimed to identify and validate the main challenges to be overcome for the promotion of sustainability in the Brazilian from the perspective of mining professionals. The research strategies employed were a systematic review of the literature and a survey. The data collected was processed using Lawshe’s quantitative method. The questionnaire was answered by 53 experts, and 8 of the 11 challenges identified in the literature were validated. The results highlight insufficient water resource management, a lack of technology, difficulties in implementing Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) practices, and misalignment with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Global challenges, such as emissions control and renewable energy integration, were not validated, indicating a possible disconnect between international priorities and local realities. Therefore, the findings reinforce the need for robust public policies, technological innovation, and participatory governance, adapted to the Brazilian context. The study contributes to literature by incorporating the views of industry professionals, providing input for corporate and regulatory strategies.

1. Introduction

Sustainability is the basis of contemporary development, integrating ecological preservation, social justice, and economic prosperity. Its fundamental concept, intergenerational equity, proposes meeting current needs without compromising future resources. In this context, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), established by the UN in 2015, represent a transformative agenda aimed at addressing global challenges such as climate change and inequalities [1].

In this context, it is worth highlighting the importance of the mining sector, which is a strategic pillar in the global economic scenario, as it provides the material basis for industrial production chains, infrastructure development, and contemporary technological innovations [2]. From a macroeconomic perspective, evidence shows its important participation in the composition of the Gross Domestic Product, both in emerging economies—defined as economies with large economic scale, rapid growth, solid economic structure, and significant development potential [3]—as well as consolidated economies, in addition to generating important formal jobs and related economic activities [2]. In the corporate sphere, although the mineral sector promotes investments in human capital and territorial development, it faces recurring questions about the effectiveness of its Corporate Social Responsibility actions and the management of conflicts with local populations [4].

From an environmental perspective, recent research highlights the correlation between the expansion of mining operations and processes of ecosystem degradation, such as habitat fragmentation, hydrological changes, and soil pollution, which requires the adoption of mitigating operational protocols [5]. Furthermore, the current context of energy transition has intensified pressure on strategic mineral resources, creating a paradox between their indispensability for green technologies and the imperatives of sustainability in their extraction [6].

In Brazil, the mining sector is one of the central drivers of national economic development, accounting for 4.0% of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and sustaining a production chain that encompasses approximately 205,000 direct jobs [7], expanding to more than 2 million job opportunities when indirect and induced effects are considered [7,8]. From a fiscal point of view, the mineral segment stands out as a relevant source of public resources, with an emphasis on revenue from the Financial Compensation for Mineral Resource Exploration (CFEM) and other federal and state taxes, whose redistributed resources enable strategic investments in priority areas such as infrastructure, health services, and educational systems [9].

Regarding this, environmental impacts include vegetation removal, ecosystem contamination, conservation units being compromised, and irreversible changes to natural landscapes [10,11,12]. In addition, equally worrying social costs are observed, such as systemic risks to population health in mining regions; patterns of socioeconomic vulnerability; and catastrophic events with persistent effects [11,12].

In this context, the following research question emerges: “What are the challenges to be overcome by the mining sector in promoting sustainability, considering the Brazilian context?” Therefore, this study aimed to identify and validate the challenges for greater integration of sustainability in the mining sector, considering the context of Brazil, a country with an emerging economy. Although there are some studies on the subject, few seek to capture the perspective of professionals directly involved in the sector, who are important actors for the implementation of effective changes [13,14,15].

2. Sustainable Challenges in the Mining Sector

The mining sector, as a strategic pillar for economic growth in emerging economies, faces the urgent need to harmonize its production processes with the principles of sustainability [1]. Furthermore, the implementation of environmentally responsible methods goes beyond simply reducing ecological and community damage, representing equally a determining factor for the continuity of the activity [16]. In this context, it is important for the mining sector to undergo an exemplary transformation, adopting innovative approaches that combine operational efficiency with socio-environmental commitment, in line with the Sustainable Development Goals [16,17,18].

Considering this context, it is worth highlighting some of the challenges faced by the sector, such as the difficulties in effectively implementing Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) strategies, which face critical challenges, such as the need to balance economic interests with socio-environmental impacts. In fact, the absence of robust regulations and reliance on voluntary initiatives often limit the effectiveness of these practices, resulting in the prioritization of commercial interests over social benefits [19]. Additionally, operational barriers, such as resistant organizational cultures and inadequate resource allocation, hinder community engagement [20]. Given this scenario, inclusive growth and the creation of shared value emerge as essential mediators for linking social accounting to truly sustainable CSR [21].

The lack of effective integration of sustainability practices into mining sector operations is a persistent challenge. In particular, the need to redefine strategies and adopt innovative approaches to address the challenges of mining is pressing, as the incorporation of sustainability remains a challenge, especially for small companies, due to a lack of knowledge, government engagement, and effective communication [22]. This disparity identifies barriers to the adoption of sustainable measures [23]. In this sense, the importance of innovative technologies, public policies, and dialog with society to balance economic, social, and environmental aspects in the mineral sector is emphasized [24].

Another important challenge is the lack of alignment with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which highlights contradictions between socioeconomic development and environmental impacts. When analyzing sustainable development goals in mining operations, deficiencies are found in SDGs such as clean energy (SDG7), climate action (SDG13), and gender equality (SDG5) [25] while artisanal mining reduces poverty (SDG 1), but simultaneously degrades ecosystems (SDG 15) [26]. In addition, the lack of coordination between governments, companies, and communities exacerbates problems and conflicts, which hinders sustainability [27].

Inadequate water resource management is a major challenge, with both artisanal and large-scale mining posing critical challenges to sustainable water resource management. For example, artisanal gold mining is associated with mercury contamination, aquifer degradation, and hydro morphological changes, which require water and tailings management plans, as well as cooperation between government, communities, and miners to mitigate impacts [28]. On the other hand, large-scale mining faces water conflicts resulting from a lack of transparency, overexploitation of water rights, and insufficient public policies [29]. Although the sector has lower overall water consumption, its local pressure is significant, requiring regionalized approaches to reconcile mineral production and water sustainability [30]. Given this scenario, these challenges highlight the need for integrated management models that balance socioeconomic and environmental demands.

The lack of effective recovery of degraded areas emerges as a challenge for the effective recovery of mining areas, whose analysis involves the analysis of unsustainable artisanal mining management. In this context, the need for integrated approaches, such as problem analysis, planning, and enforcement, to mitigate environmental impacts is emphasized [31]. In addition, revegetation is a key strategy for post-mining soil recovery, using native species and technologies such as nanomaterials to improve soil fertility and restore ecosystems [32]. Finally, the gap between the impacts of mining and the effective restoration of ecosystems is evident, reaffirming the need for robust practices for the recovery of mined areas [33].

The lack of control over greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions presents a complex challenge in the mining sector, highlighting a paradoxical relationship: although climate adaptation requires mineral resources, extraction and processing themselves contribute to GHG emissions [34]. In addition, environmental degradation caused by mining and pressure on water resources are exacerbated by climate change [35]. In this context, the transition to sustainable mining requires the control of GHG emissions, which is a critical challenge for the sector, considering its direct impact on global warming [36].

The implementation of reverse logistics is one of the challenges facing the mining sector. In this sense, the implementation of circular practices, particularly waste recovery systems, can be operationalized in real mining contexts [37]. Furthermore, systematic analyses have identified the main obstacles to reverse logistics, such as lack of infrastructure and economic incentives, while proposing strategic solutions [38]. Similarly, quantitative analysis of operational challenges highlights the need for integration between waste management and production chains [39], demonstrating that reverse logistics requires customized technical approaches to realize its environmental and economic benefits.

The lack of efficient waste management in mining remains a critical challenge. Although circular economy strategies and digital integration can optimize tailings management, the lack of effective technologies limits current methods, and solutions such as real-time monitoring and material reuse are needed to overcome these gaps [40]. Additionally, studies warn of the environmental risks posed by gigatons of waste in Brazil, which highlight the lack of effective policies for waste containment in megadiverse regions [41]. Finally, the analysis of conflicts arising from poor waste management has shown not only soil and water contamination, but also the worsening of inequality, which highlights the need for reflective governance models for environmental justice [42].

The lack of technology in the mining sector is one of the obstacles to achieving sustainability. In this context, barriers to the adoption of innovations—such as high initial costs, resistance to change, and a lack of skilled labor—show that without overcoming these challenges, the mining industry remains dependent on outdated methods, resulting in increased waste and pollution [43]. Furthermore, the negative impacts of traditional mining, such as soil degradation and water contamination, reinforce that the lack of environmental mitigation technologies exacerbates these problems, especially in regions with weak regulations [44]. Finally, the proposal to use analytical tools to evaluate sustainable technological solutions, such as waste management systems and renewable energy, shows that their implementation is limited by a lack of data [45].

The lack of government support and specific legislation is a critical challenge, in which the absence of a robust regulatory framework and efficient public policies results in predatory mining practices, inefficient management of natural resources, and socio-environmental conflicts, a situation that highlights the need for institutional reforms that promote transparency and oversight in the mining sector [46]. Similarly, in emerging economies, insufficient government incentives and weak environmental laws hinder the adoption of clean technologies and good operating practices, perpetuating unsustainable extractive models [47]. Finally, artisanal mining, often carried out on the fringes of legality due to the lack of adequate regulation, not only generates serious environmental impacts, such as mercury contamination, but also social problems, including informal work and land conflicts, a fact that points to the urgency of integrative policies that formalize these workers with sustainable criteria [48].

The lack of integration of renewable energy sources (RES) in the mining sector represents a major challenge. Although RES (such as solar and wind) have the potential to reduce the carbon footprint of mining, their adoption is limited both by a lack of strategic planning and by dependence on fossil fuels in remote operations [49]. Furthermore, the identification of technical and economic barriers—such as the intermittency of RES and high initial investments—not only hinder their large-scale adoption but also highlight the need for public policies that encourage energy transition in the sector, such as subsidies and public–private partnerships [50]. Finally, analyses of practical strategies to overcome these challenges, including battery storage, smart microgrids, and renewable energy purchase agreements (PPAs), demonstrate that the integration of RES is feasible, although it requires technological innovation and corporate commitment [51]. Table 1 presents a summary of the above challenges.

Table 1.

Challenges in the mining sector identified in the literature.

3. Methodological Procedures

This study was developed in four sequential methodological stages: First, a systematic review of the literature was conducted to identify the main challenges facing the mining sector that need to be overcome and that contribute to the promotion of sustainability; then, based on the results of the literature, a questionnaire was developed for data collection; subsequently, this instrument was applied to professionals in the mining sector working in Brazil; after data collection, the Lawshe Method was used to validate the challenges identified; finally, the results obtained were critically analyzed, generating conclusions and guidelines for future research in this area.

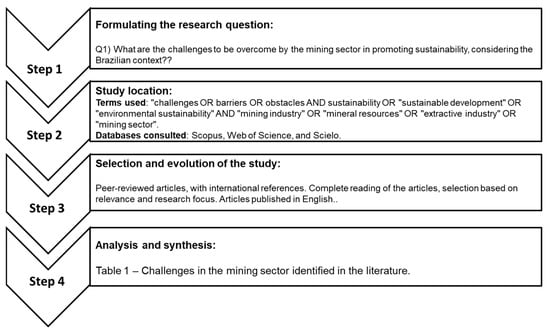

The literature review process was conducted using the Scopus, Web of Science, and Scielo scientific databases with the purpose of selecting relevant scientific publications that would support the identification of the main challenges to sustainability in the mining sector. To this end, in order to ensure a comprehensive and targeted search, research strategies were developed using Boolean operators, combining terms such as challenges OR barriers OR obstacles AND sustainability OR “sustainable development” OR “environmental sustainability” AND “mining industry” OR “mineral resources” OR “extractive industry” OR “mining sector,” which allowed us to capture important studies for the proposed analysis. Figure 1 summarizes the development of the literature review.

Figure 1.

Steps literature review.

The search strategy was implemented by analyzing titles, abstracts, and keywords from scientific publications, including both original research and review articles. In the first stage, the screening process identified 1115 potential articles, which were subjected to certain selection criteria, such as (1) thematic relevance (explicit focus on the challenges of mining for environmental, social, and economic sustainability); (2) type of publication (indexed and peer-reviewed scientific articles); (3) time frame (last decade); (4) methodological rigor (qualitative, quantitative, or mixed studies with robust evidence); and (5) languages (English and Portuguese). Simultaneously, exclusion filters were applied to eliminate studies outside the thematic scope or with duplicate content. As a result, 283 eligible articles were obtained, which were submitted for full analysis. Through a categorization process based on a complete reading of each document, 33 relevant studies were identified, which allowed for the systematization of eleven critical challenges that the mining sector needs to overcome in order to promote sustainability in its multiple dimensions.

Next, a form was developed based on the challenges identified. Experts were asked to rate each challenge using a three-point scale, where:

- (1)

- Overcoming this challenge is essential for promoting sustainability in the mining sector.

- (2)

- Overcoming this challenge is important, but not essential, for promoting sustainability in the mining sector.

- (3)

- Overcoming this challenge is not important for promoting sustainability in the mining sector.

The experts were contacted both by email and social media, while the form was made available via an online link created on the Google Forms platform, remaining open for responses for just over a month. Of the total of 324 professionals invited, a response rate of 16.36% was obtained. In terms of geographic distribution, participants were distributed as follows: 32.08% in the North, 37.74% in the Southeast, 22.64% in the Northeast, and 3.77% in both the South and Midwest of Brazil. In terms of professional experience, 28.3% of respondents had up to 5 years of experience, 20.75% had between 5 and 10 years, and 50.94% had more than 10 years of experience in the sector. In terms of positions held, the distribution was as follows: 20.75% in executive, supervisory, and management positions, 18.87% as coordinators and supervisors, and 60.38% as analysts, consultants, specialists, engineers, geologists, and technicians. Finally, in terms of academic profile, 1.89% were enrolled in higher education, 98.11% had a bachelor’s degree, 18.87% had a specialization, 22.64% had a master’s degree, and 5.66% had a doctorate.

After collecting data obtained through the survey applied to professionals, the Lawshe method was employed in accordance with guidelines [52,53]. This method consists of submitting each criterion of the research instrument to the qualified assessment of the respondents, who must classify them into three levels of relevance: (1) “essential” to the topic under investigation, (2) “important, but not essential,” or (3) “not important.” The methodology calculates the Content Validity Ratio (CVR) for each criterion in the questionnaire, following the formula described by Equation (1) in Table 2.

Table 2.

Equations for calculating the Content Validity Ratio.

The use of Lawshe’s method is justified in exploratory research due to the need to combine the initial search for understanding of a still poorly structured phenomenon with the requirement to confer rigor and objectivity to the content validation obtained from experts. In exploratory contexts, where constructs and variables may not be fully consolidated, Lawshe’s method offers a systematic approach to quantify the degree of consensus among experts regarding the relevance and representativeness of the items evaluated, transforming qualitative judgments into quantitative metrics through the calculation of the Content Validity Index. In this way, the method contributes to strengthening the internal consistency and theoretical legitimacy of the instruments or categories under development, reducing the subjectivity inherent in the exploratory phase and ensuring that the analyzed elements effectively reflect the accumulated expert knowledge on the subject.

Regarding Equation (1)—Content Validity Ratio (CVR), where “ne” represents the number of experts who consider the criterion to be “essential” and “N” is the total number of experts who participated in the survey. CVR values range from −1 to +1, with −1 indicating complete disagreement and +1 indicating complete agreement [55]. When evaluating the possible results obtained by the procedure, when more than 50% of respondents perceive the criterion as “essential,” the CVR is positive; however, when less than 50% of respondents indicate the criterion as “non-essential,” the CVR is negative. A CVR equal to zero indicates that half of the experts consider the criterion “essential” and the other half do not [56].

Equation (5)—Critical Content Validity Ratio (CVRcrítico) considers the parameters of mean, variance, and standard deviation, as described in Equations (2)–(4), where in these cases, “N” is the number of respondents and “p” is the probability of considering the item essential. Based on these parameters, it is possible to calculate the CVRcrítico, where necr ítico is given by necr ítico = μ + z .σ. Considering a significant level of 5% in the standard normal distribution, the z value used is 1.96. This level of significance follows the conventional level, ensuring comparability with previous validations based on the Lawshe method and maintaining statistical robustness.

4. Results and Associated Debates

According to the methodologies and guidelines described by [52,53] and after applying the Content Validation Ratio (CVR) calculation for each challenge analyzed in this study, the critical CVR value was determined. It is important to note that the survey involved the participation of 53 professionals working in the mining sector in Brazil. The critical CVR obtained was 0.269, a value used as a reference for the validation of the challenges identified. Thus, challenges with coefficients greater than 0.269 were considered valid, while those with lower values were considered invalid because they did not meet the established criteria. This approach aims to ensure the relevance of the challenges in the context of the mining sector in a country with an emerging economy, such as Brazil, especially when the objective is to promote the sustainability of the mining sector, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Validation of challenges—Analysis using the Lawshe Method.

The analysis of the data presented in Table 3 allowed us to identify the challenges considered relevant for promoting sustainability in the mineral sector, according to the perception of professionals who work directly in this segment in the Brazilian context. Among the 11 challenges initially raised, 8 were validated as significant, as shown in Table 3. Regarding the social dimension, the validated challenges were “Difficulty in effectively implementing Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) strategies,” “Lack of effective integration of sustainability practices in mining sector operations,” and “Lack of alignment with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).” In the environmental dimension, the validated challenges were “Insufficient water resource management,” “Lack of effective recovery of degraded areas,” and “Lack of mining waste management.” In terms of the economic dimension, the validated indicators were “Absence of technologies” and “Lack of government support and specific legislation.”

Analyzing the first validated challenge, “Difficulty in effectively implementing Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) strategies,” it is clear that the effectiveness of these strategies is compromised by the lack of a consistent regulatory framework and excessive reliance on voluntary actions, factors that often result in the prioritization of economic objectives over socio-environmental considerations [19]. Furthermore, as highlighted by [20], internal organizational barriers, such as resistance to change and poor resource distribution, are intensified in the Brazilian context, where historical challenges in relations with local communities and the absence of strategic integration of CSR into corporate operations are particularly evident. In this context, the inability to measure impacts systematically, coupled with the fragmentation of existing initiatives, highlights the urgency of stricter regulatory mechanisms and the adoption of a holistic approach. Thus, such measures are important for CSR to overcome its symbolic role of corporate legitimization and consolidate itself as an effective instrument of sustainability in the Brazilian mining sector.

The validation of the challenge “Lack of effective integration of sustainability practices in mining sector operations” in the Brazilian context reveals a complex problem. As highlighted by [22], this difficulty is particularly pronounced among small companies in the sector, which face obstacles such as a lack of technical knowledge, insufficient government support, and deficiencies in communication processes. Furthermore, this reality becomes even more critical due to the heterogeneity of the national mining industry, where large-scale operations—with more consolidated structures—coexist with small enterprises with limited capacity [23]. When analyzing this perspective, the authors demonstrate that the challenges to sustainability in the sector are not restricted to purely technological issues, but also encompass cultural and organizational aspects. In this sense, to overcome these challenges, as proposed by [24], a multidimensional approach is needed that integrates technological innovation, improvement of public policies, and strengthening of dialog with the impacted communities, elements that are essential conditions for the sustainable development of Brazilian mining. Regarding this, the development of practices that enhance the integration of operations towards a more sustainable sector is important. For example, promoting integrated management between managers and operational staff can contribute to achieving more sustainable goals in the sector.

The validated challenge “Lack of alignment with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)” demonstrates a disconnect between the practices of the Brazilian mining sector and the goals of the 2030 Agenda, particularly SDGs 7 (clean energy), 13 (climate action), and 5 (gender equality), as evidenced by [25]. This mismatch reflects both operational limitations and deficiencies in sectoral governance, exacerbated by the dichotomy between large industrial operations—with isolated advances in innovation (SDG 9)—and artisanal mining, which reproduces patterns observed in African contexts [54], in which economic benefits (SDG 1) coexist with environmental degradation (SDG 15). Given this scenario, the absence of effective coordination mechanisms between government, companies, and communities, as highlighted by the same authors, intensifies the contradictions typical of the “resource curse,” which requires, as proposed by Mahmoudi Kouhi et al. ([25]), the implementation of specific evaluation systems to measure and promote the internalization of SDGs throughout the production chain of the national mining sector.

The validation of the challenge “Insufficient water resource management” in the Brazilian mineral sector reveals a multifaceted problem, characterized by different impacts depending on the scale of operation. As evidenced by studies, artisanal mining mainly generates qualitative impacts, such as mercury contamination and aquifer degradation, which requires cooperative approaches between government, communities, and miners [28]. On the other hand, large-scale mining faces quantitative and institutional challenges, including conflicts over water rights and inadequate public policies [29]. Although sectoral water consumption is relatively low globally, its local pressure is significant, especially in sensitive biomes such as the Amazon and Cerrado, requiring regionalized management models [30]. In this context, effective solutions require the integration of closed-loop technologies, participatory governance, and compensation mechanisms adapted to the Brazilian reality, where the coexistence of industrial operations and mining in shared basins intensifies socio-environmental conflicts and requires differentiated institutional responses.

The “lack of effective recovery of degraded areas” is another validated challenge, which highlights a complex issue with distinct characteristics depending on the scale of operations in the mining sector. As demonstrated in comparative studies, such as [31], the obstacles faced by artisanal mining in Brazil are similar to those documented in the African context, which requires comprehensive solutions that combine accurate environmental assessments, collaborative planning strategies, and robust enforcement mechanisms. In turn, innovative technical approaches, including revegetation techniques with native species and the application of nanomaterials for soil regeneration [32] face specific challenges in the Brazilian reality, especially in fragile ecosystems such as the Amazon and Cerrado biomes. In addition, the discrepancy between the magnitude of environmental impacts and the effectiveness of restoration actions, as highlighted by [33], is intensified in the national scenario by three factors: (1) deficiencies in environmental inspection systems; (2) technological inequalities between different sizes of mining operations; and (3) ecological particularities of the impacted environments, factors that require the development of specific protocols that address these singularities in the recovery plans for mined areas.

The validated challenge “Lack of mining waste management” demonstrates its importance, particularly when considering the severe environmental and socioeconomic effects resulting from mining operations in the country. As evidenced in studies such as [41], the magnitude of the problem is evident in the uncontrolled accumulation of tailings in areas of high biodiversity—aggravated by the lack of adequate regulatory mechanisms—which has caused the accelerated degradation of terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems. Furthermore, as highlighted by [42], inadequate management of these materials exacerbates social and environmental tensions, which requires the adoption of more participatory and adaptive governance structures to promote socio-environmental equity. On the other hand, [40] identifies the scarcity of sophisticated technological solutions—including continuous monitoring systems and approaches based on the principles of the circular economy—as the main obstacle to mitigating these impacts. Given these findings, the consistent correlation between academic findings and the results obtained from methodological validation emphasizes the urgent need to: develop more effective regulatory frameworks, foster sectoral technological advances, and implement social engagement mechanisms as fundamental pillars for sustainable management of mining waste in Brazil.

Another validated challenge, the “Absence of technologies,” highlights the seriousness of this limitation as a determining factor for the sustainable development of the national mining sector. In fact, the results obtained corroborate the studies by [43], which identify an interrelated set of obstacles to technological modernization, ranging from financial aspects (such as high capital costs for implementation) to cultural issues (organizational resistance) and technical training (shortage of qualified professionals), factors that together perpetuate the use of outdated operating methods with significant environmental costs. It is worth noting that this situation becomes even more critical when analyzed from the perspective of Brazil’s specificities, in which, as demonstrated by [44], the combination of outdated technology and an inadequate regulatory framework exacerbates ecological damage, particularly in vulnerable biomes. Although the international scenario offers promising technological alternatives—as highlighted by [45] with their integrated environmental management systems and renewable energy solutions —their adoption in the national context faces structural barriers, such as deficiencies in basic infrastructure and insufficient robust data collection and analysis systems. Given this situation, the remarkable congruence between the empirical evidence reported in the specialized literature and the findings of this methodological validation unequivocally highlights the urgent need to formulate and implement specific industrial policies that place technological innovation at the heart of the strategy for the sustainable transformation of the Brazilian mining sector.

Finally, the validation of the challenge “Lack of government support and specific legislation” highlights a critical structural obstacle to achieving sustainability in the Brazilian mining sector, presenting significant parallels in international studies. As demonstrated by [46], the lack of a consistent regulatory framework—a phenomenon that is replicated in the Brazilian scenario—not only creates conditions conducive to the maintenance of environmentally predatory practices, but also exacerbates socio-environmental tensions, requiring profound changes in sectoral governance structures. This situation is even more complex in developing countries, where [47] identify that the combination of weak environmental legislation and the absence of effective government incentive mechanisms acts as a barrier to the sustainable modernization of the sector, leading to the perpetuation of obsolete operating models with high socio-ecological costs. In the specific case of Brazil, as highlighted by [48], regulatory gaps are particularly worrying in the artisanal mining segment, whose marginalized operations result in both severe environmental damage (especially contamination by substances such as mercury) and significant social issues arising from informality. Given this scenario, there is a clear and urgent need to develop comprehensive policy strategies that simultaneously address: (1) improving institutional oversight and monitoring capacities; in addition, (2) updating the sector’s legal framework; and, finally, (3) creating effective mechanisms for formalization and training for small producers—elements that are not only fundamental but also essential for building a truly sustainable governance model for the mining sector in the Brazilian context.

Although the challenges “Lack of control of greenhouse gas emissions,” “Difficulties in implementing reverse logistics,” and “Low integration of renewable energy sources (RES)” were not statistically validated in this study with professionals from the Brazilian mining sector, their relevance to sustainability in mining remains unquestionable. The non-validation of these aspects by respondents does not imply a lack of importance but may reflect particularities of the Brazilian operational context or different sectoral priorities. It is essential to recognize that these factors continue to represent significant structural challenges for the sustainability of the sector globally, especially in emerging economies, as widely documented in the specialized literature.

The analysis of the results reveals that three challenges, “Lack of control of greenhouse gas emissions,” “Difficulties in implementing reverse logistics,” and “Low integration of renewable energy sources (RES),” did not achieve statistical significance in the validation carried out with experts from the Brazilian mining sector. However, it is important to note that this lack of empirical validation does not diminish their recognized theoretical and practical importance for the sustainability of the sector. The discrepancy between the findings of this research and the consensus in the international literature can be attributed to contextual factors specific to the Brazilian reality, such as operational particularities or distinct hierarchies of priorities in the business environment. It is important to note that these challenges remain structural obstacles to sustainability in the mining sector, particularly relevant in developing countries, as attested by several academic studies on the subject. This finding suggests the need for further research to explore the reasons underlying the different perceptions of these factors by Brazilian professionals.

The absence or fragmentation of reliable data on greenhouse gas emissions from the Brazilian mining sector stems primarily from the lack of specific sectoral inventories and the limitations of national reporting systems, which aggregate industrial emissions into broad categories, making disaggregation by mining activity difficult. Furthermore, the heterogeneity of companies in the sector, ranging from large corporations with robust sustainability reports to small mining companies without disclosure obligations, contributes to the inconsistency and discontinuity of information. The Brazilian National Emissions Inventory, although comprehensive, does not detail the emissions associated with the productive stages of mining (extraction, processing, transportation, and waste disposal), which prevents an accurate view of the sector’s carbon footprint. This gap has strategic relevance, as it hinders the development of public mitigation policies, the fulfillment of international decarbonization commitments, and the integration of ESG criteria into mineral supply chains, limiting the country’s ability to measure, manage, and reduce its emissions in a transparent and evidence-based manner.

Additionally, it is worth noting that the ESG-oriented framework presented by [54], which proposes a systemic integration between technical sustainability measures, impact mitigation, and management mechanisms for complex mining, can both complement and contrast with the Brazilian context. The framework complements other methods by offering an operational architecture that emphasizes continuous environmental monitoring, the technical optimization of processes, and corporate responsibilities that can strengthen liability control practices and risk reduction [54]. However, it contrasts insofar as the proposed framework appears to be generated from priorities and institutional structures distinct from those in Brazil and, therefore, requires institutional translation to respect the strong regulation and transparency requirements already in force in Brazil. In practice, adaptation would require that the technical elements be aligned with Brazilian regulatory and participatory instruments, to transform technical proposals into practices compatible with national regulatory governance and socio-environmental accountability standards [54].

5. Conclusions

This study aimed to identify and validate the main challenges for sustainability in the Brazilian mining sector, considering the context of an emerging economy. To this end, a methodological approach was adopted that combined a systematic review of the literature, a survey of professionals, and the application of the Lawshe method, which allowed the study to achieve its purpose by highlighting the perceptions of professionals directly involved in the sector. As a result, the empirical validation of the challenges not only reinforced the relevance of critical issues, such as water resource management and technology integration, but also revealed the particularities of the national scenario.

The results showed that, among the 11 challenges initially raised, 8 were validated as priorities by the experts, with CRV above 0.269, with “Insufficient water resource management” (CVR = 0.88) and “Lack of technologies” (CVR = 0.28) standing out. Specifically, the validated challenges were distributed as follows: the social dimension faced the issues of “Difficulty in effectively implementing Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) strategies,” “Lack of effective integration of sustainability practices in mining sector operations,” and “Lack of alignment with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)”; the environmental dimension faced the issues of “Insufficient management of water resources,” “Lack of effective recovery of degraded areas,” and “Lack of mining waste management”; and, finally, the economic dimension faced the issues “Absence of technologies” and “Lack of government support and specific legislation.” However, challenges widely discussed in international literature, such as GHG emissions control, reverse logistics, and renewable energy sources (RES), did not reach statistical significance, suggesting a possible disconnect between global priorities and local realities. This divergence may be associated with specific characteristics of the Brazilian mining sector, such as the predominance of small-scale operations and regulatory gaps.

The implications of this study are both theoretical and practical. In the theoretical field, the research expands the literature by demonstrating that, in emerging economies, challenges such as insufficient water resource management, the absence of adequate technologies, regulatory fragility, and the difficulty of integrating sustainability practices constitute central barriers to the transformation of the sector. In practice, the results reinforce the need to strengthen the Brazilian regulatory framework, foster technological innovation, and adopt public policies that enable the recovery of degraded areas and effective waste management. Furthermore, the validation of the challenges by industry professionals reinforces the feasibility of implementing the proposed solutions.

A limitation of the research is its exploratory nature, since it focuses on a single context for analysis. Another limiting factor was the response rate, which was 16.36%. However, it should be noted that for the Lawshe method that the quality and knowledge of the professionals in the analyzed context are more important than the quantity of responses. Furthermore, professionals from all 5 different regions of Brazil participated in the survey. Consequently, given the sample’s composition and focus on Brazilian professionals, results should be interpreted contextually.

For future research, we recommend the following actions: (1) conducting a quantitative study to develop specific indicators that measure progress in overcoming the validated challenges; (2) formulating an integrated framework that relates these challenges to socio-environmental performance metrics, adapted to the context of emerging economies. Such initiatives could broaden the applicability of the results but also assist in both public policy evaluation and sustainable corporate management. Additionally, scholars should (3) consider strategies for promoting sustainability in the mining sector that were not analyzed in this study, such as, for example, the concept and guidelines of Environmental, Social and Governance—ESG. Finally, it is important to note that continued investigation of these gaps is essential to align the Brazilian mining sector with the principles of Agenda 2030.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.D.B. and V.W.B.M.; methodology, E.D.B., A.C.S.M., V.W.B.M. and M.T.d.P.; software, E.D.B.; validation, S.F.d.S., A.N.P. and F.C.A.L.; formal analysis, E.D.B. and V.W.B.M.; investigation, E.D.B.; resources, E.D.B. and V.W.B.M.; data curation, S.F.d.S., A.N.P. and F.C.A.L.; writing—original draft preparation, E.D.B.; writing—review and editing, E.D.B. and S.F.d.S.; visualization, V.W.B.M. and A.C.S.M.; supervision, F.C.A.L. and V.W.B.M.; project administration E.D.B. and V.W.B.M.; funding acquisition, V.W.B.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico—CNPq grant number: 300195/2025-7 and Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior—CAPES grant number: 88887.185063/2025-00.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Monteiro, N.B.R.; da Silva, E.A.; Moita Neto, J.M. Sustainable development goals in mining. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 228, 509–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ericsson, M.; Löf, O. Mining’s contribution to national economies between 1996 and 2016. Miner. Econ. 2019, 32, 223–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Pan, Q. Economic Growth in Emerging Market Countries. Glob. J. Emerg. Mark. Econ. 2021, 13, 192–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilson, G.; Maconachie, R. Artisanal and small-scale mining and the Sustainable Development Goals: Opportunities and new directions for sub-Saharan Africa. Geoforum 2020, 111, 125–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maus, V.; Giljum, S.; Gutschlhofer, J.; da Silva, D.M.; Probst, M.; Gass, S.L.B.; Luckeneder, S.; Lieber, M.; McCallum, I. A global-scale data set of mining areas. Sci. Data 2020, 7, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sovacool, B.K.; Ali, S.H.; Bazilian, M.; Radley, B.; Nemery, B.; Okatz, J.; Mulvaney, D. Sustainable minerals and metals for a low-carbon future. Science 2020, 367, 30–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBRAM, I.B.d.M. Resultados da Indústria Mineral Brasileira em 2022. Available online: https://ibram.org.br/noticia/desempenho-da-mineracao-tem-queda-em-2022-mas-setor-cria-mais-empregos-e-aumentara-investimentos-para-us-50-bi-ate-2027/ (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Brasil, M.d.M.e.E. Em 2023, MME Trabalhou para Criar Cenário Nacional Favorável para Investimentos. Available online: https://www.gov.br/mme/pt-br/assuntos/noticias/em-2023-mme-trabalhou-para-criar-cenario-nacional-favoravel-para-investimentos (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Silva, L.N.O.; da Silva, J.G.; de Almeida, R.B. Environmental disasters and their impacts on the Brazilian economy: The mining industry case. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 23817–23837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontana, M.E.; Levino, N.d.A.; Guarnieri, P.; Salehi, S. Using Group Decision-Making to assess the negative environmental, social and economic impacts of unstable rock salt mines in Maceio, Brazil. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2023, 16, 101360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macêdo, A.K.S.; de Oliveira, T.d.C.M.; Brighenti, L.S.; dos Santos, H.B.; Thomé, R.G. Socio-environmental impacts on the Doce River basin, Brazil: A review from historic pollution to large disaster events. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 21, 2339–2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siqueira-Gay, J.; Sonter, L.J.; Sánchez, L.E. Exploring potential impacts of mining on forest loss and fragmentation within a biodiverse region of Brazil’s northeastern Amazon. Resour. Policy 2020, 67, 101662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skenderas, D.; Politi, C. Industry 4.0 Roadmap for the Mining Sector. In RawMat 2023; MDPI: Basel, Switzerland, 2023; p. 16. [Google Scholar]

- Banda, W. A proposed DEMATEL based framework for appraising challenges in the artisanal and small-scale mining sector. Resour. Policy 2023, 80, 103172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marimuthu, R.; Sankaranarayanan, B.; Ali, S.M.; Jabbour, A.B.L.d.S.; Karuppiah, K. Assessment of key socio-economic and environmental challenges in the mining industry: Implications for resource policies in emerging economies. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 27, 814–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, F.P. Mining industry and sustainable development: Time for change. Food Energy Secur. 2017, 6, 61–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blinova, E.; Ponomarenko, T.; Knysh, V. Analyzing the Concept of Corporate Sustainability in the Context of Sustainable Business Development in the Mining Sector with Elements of Circular Economy. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Famiyeh, S.; Opoku, R.A.; Kwarteng, A.; Asante-Darko, D. Driving forces of sustainability in the mining industry: Evidence from a developing country. Resour. Policy 2021, 70, 101910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, N. Challenges of corporate social responsibility (CSR) in domestic settings: An exploration of mining regulation vis-à-vis CSR in Ghana. Resour. Policy 2016, 47, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinari, C.; Annan-Diab, F. Challenges facing practitioners when implementing CSR strategies: The case for the Brazilian mining industry. Soc. Responsib. J. 2024, 20, 1451–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, T.; Sahoo, C.K. Indian mining industry: A balancing act? Social accounting and the path to sustainable corporate social responsibility. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2025, 32, 434–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateus, A.; Martins, L. Challenges and opportunities for a successful mining industry in the future. Bol. Geol. Y Min. 2019, 130, 99–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, W.; Ferreira, P.; Araújo, M. Challenges and pathways for Brazilian mining sustainability. Resour. Policy 2021, 74, 101648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qarahasanlou, A.N.; Khanzadeh, D.; Shahabi, R.S.; Basiri, M.H. Introducing sustainable development and reviewing environmental sustainability in the mining industry. Rud. Geol. Naft. Zb. 2022, 37, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudi Kouhi, R.; Jebrailvand Moghaddam, M.M.; Rafie, S.F.; Maghsoudy, S.; Doulati Ardejani, F.; Butscher, C.; Taherdangkoo, R. A quantitative framework for measuring sustainable development goals in mining operations. Discov. Sustain. 2024, 5, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tougma, W.J.; Koffi, G.B.; Kouraogo, P.; Yao, K.A. Balancing economic gains and environmental sustainability: The role of artisanal gold mining in achieving SDGs 1 and 15 in Gaoua, Burkina Faso. Miner. Econ. 2025, 38, 473–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mvile, B.N.; Bishoge, O.K. Mining and sustainable development goals in Africa. Resour. Policy 2024, 90, 104710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustamante, N.; Danoucaras, N.; McIntyre, N.; Díaz-Martínez, J.C.; Restrepo-Baena, O.J. Review of improving the water management for the informal gold mining in Colombia. Rev. Fac. Ing. 2016, 174–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arenas-Collao, K.; Valdés-González, H.; Reyes-Bozo, L.; Salazar, J.L. The Water Management Impacts of Large-Scale Mining Operations: A Social and Environmental Perspective. Water 2024, 16, 1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lima, J.P.M.; Amaral, M.C.S.; de Lima, S.C.R.B. Sustainable water management in the mining industry: Paving the way for the future. J. Water Process Eng. 2025, 71, 107239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wireko-gyebi, R.S.; Osei, M.; Baah-ennumh, T.Y. Planning for the effective and sustainable management of Ghana ’ s artisanal small-scale gold mining industry. Resour. Policy 2022, 76, 102576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakkou, H.Z.R.; Elmansour, E.G.P.A.; Benzaazoua, F.A.M. Revegetation and ecosystem reclamation of post-mined land: Toward sustainable mining. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 21, 9775–9798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Principles, I.; For, S.; Ecological, T.H.E.; Of, R.; Sites, M. International principles and standards for the ecological restoration and recovery of mine sites. Restor. Ecol. 2022, 30, e13771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleischwitz, R. Mineral resources in the age of climate adaptation and resilience. J. Ind. Ecol. 2020, 24, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arabi, M.; Mechkirrou, L.; El Malki, M.; Alaoui, K.; Chaieb, A.; Maaroufi, F.; Karmich, S. Overview of Ecological Dynamics in Morocco-Biodiversity, Water Scarcity, Climate Change, Anthropogenic Pressures, and Energy Resources-Navigating Towards Ecosolutions and Sustainable Development. E3S Web Conf. 2024, 527, 01001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgkinson, J.H.; Smith, M.H. Climate change and sustainability as drivers for the next mining and metals boom: The need for climate-smart mining and recycling. Resour. Policy 2021, 74, 101205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Born, K. Adoption of circular economy practices in the mining sector: Evidence from Chile. Resour. Policy 2025, 102, 105514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osei, V.; Bai, C.; Asante-Darko, D.; Quayson, M. Evaluating the barriers and drivers of adopting circular economy for improving sustainability in the mining industry. Resour. Policy 2023, 86, 104168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.K.; Kumar, A.; Garza-Reyes, J.A.; de Sá, M.M. Managing operations for circular economy in the mining sector: An analysis of barriers intensity. Resour. Policy 2020, 69, 101752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Kong, D.; Ye, Q.; Zhang, X.; Tian, D.; Solangi, Y.A. Enhancing Environmental Sustainability in the Mining Industry: Circular Economy Strategies for Resource Management and Digital Integration. L. Degrad. Dev. 2025, 36, 2887–2901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmo, F.F.; Lanchotti, A.O.; Kamino, L.H.Y. Mining waste challenges: Environmental risks of gigatons of mud, dust and sediment in megadiverse regions in Brazil. Sustain. 2020, 12, 8466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, L. Socio-environmental impacts of mineral mining and conflicts in Southern and West Africa: Navigating reflexive governance for environmental justice. Environ. Res. Lett. 2024, 19, 104013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ediriweera, A.; Wiewiora, A. Barriers and enablers of technology adoption in the mining industry. Resour. Policy 2021, 73, 102188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X. Coal mining and environmental development in southwest China. Environ. Dev. 2017, 21, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouresmaieli, M.; Ataei, M.; Qarahasanlou, A.N.; Barabadi, A. Multi-criteria Decision-making Methods for Sustainable Decisionmaking in the Mining Industry (A Comprehensive Study). J. Min. Environ. 2024, 15, 683–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.U.; Zhongyi, P.; Ullah, A.; Mumtaz, M. A comprehensive evaluation of sustainable mineral resources governance in Pakistan: An analysis of challenges and reforms. Resour. Policy 2024, 88, 104383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholaus Chusi, T.; Bouraima, M.B.; Yazdani, M.; Jovčić, S.; Hernández, V.D. Addressing the Challenges Facing Developing Countries in the Mining Sector: Moving Towards Sustainability. J. Appl. Res. Ind. Eng. 2024, 11, 333–349. [Google Scholar]

- Achina-Obeng, R.; Aram, S.A. Informal artisanal and small-scale gold mining (ASGM) in Ghana: Assessing environmental impacts, reasons for engagement, and mitigation strategies. Resour. Policy 2022, 78, 102907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouresmaieli, M.; Ataei, M.; Nouri Qarahasanlou, A.; Barabadi, A. Integration of renewable energy and sustainable development with strategic planning in the mining industry. Results Eng. 2023, 20, 101412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Hao, J.; Liu, M.; Cui, N. Risks impeding sustainable energy transition related to metals mining. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2024, 52, 228–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enemuo, M.; Ogunmodimu, O. Transitioning the mining sector: A review of renewable energy integration and carbon footprint reduction strategies. Appl. Energy 2025, 384, 125484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, I.C.R. Da Aplicação do Método de Lawshe Para Avaliação da Percepção de Clientes de Belo Horizonte a Respeito dos Serviços de Supermercados; Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais: Belo Horizonte, Brazil, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rampasso, I.S.; Quelhas, O.L.G.; Anholon, R.; Pereira, M.B.; Miranda, J.D.A.; Alvarenga, W.S. Engineering education for sustainable development: Evaluation criteria for Brazilian context. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondarenko, V.; Salieiev, I.; Kovalevska, I.; Chervatiuk, V. A new concept for complex mining of mineral raw material resources from DTEK coal mines based on sustainable development and ESG strategy. Min. Miner. Depos. 2023, 17, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayre, C.; Scally, A.J. Critical values for Lawshe’s content validity ratio: Revisiting the original methods of calculation. Meas. Eval. Couns. Dev. 2014, 47, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawshe, C.H. A quantitative approach to content validity. Pers. Psychol. 1975, 28, 563–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).