Abstract

Fisheries worldwide exhibit puzzling boom-and-bust cycles despite regulatory efforts, raising questions about what drives these oscillations. We investigate whether temporal delays in monitoring and decision-making contribute to system instability. Our model uses delay differential equations to track an exploiting population and its renewable resources, incorporating two distinct delays: one for perceiving resource status () and another for implementing management responses (). We establish the existence, uniqueness, and positivity of solutions, then analyze equilibrium stability through linearization and Lyapunov–Razumikhin functions. The characteristic equation reveals Hopf bifurcations at critical delay thresholds. Numerical simulations across 1600 parameter combinations using MATLAB R2023b’s DDE23 algorithm quantify these transitions. The results show a critical threshold near 1.64 years (20 months): below this value, systems converge to a stable equilibrium, while above it, persistent oscillations emerge within 20–26 year periods. Unexpectedly, one large delay destabilizes less than two moderate delays summing to the same total, contradicting uniform improvement strategies. Convergence to limit cycles requires roughly 40 years, exceeding typical management horizons and potentially masking true system dynamics. The critical threshold lies within realistic administrative timescales, suggesting that institutional delays may substantially contribute to observed population fluctuations. These findings indicate that accelerating either monitoring or decision processes rather than providing modest improvements to both could better stabilize exploited resources.

1. Introduction

The exploitation of natural resources by human populations constitutes one of the major challenges of our era. Understanding the mechanisms governing the interaction between demographic dynamics and resource availability has become crucial for anticipating future developments and designing sustainable management strategies.

Mathematical modeling provides powerful tools for understanding population–resource interactions. As demonstrated by Ali and Jawad [1] in their study of phytoplankton–zooplankton dynamics in aquatic environments, mathematical models enable (i) quantitative predictions that can be tested against empirical data, (ii) the identification of non-intuitive dynamics that may not be apparent from verbal reasoning alone, (iii) systematic parameter sensitivity analysis for management optimization, and (iv) a framework for integrating mechanistic understanding with observational data. These advantages motivate our mathematical approach to analyzing delay effects in population–resource systems.

Empirical observations reveal that these interactions often generate surprising behaviors: cycles of abundance and scarcity, sudden collapses of exploiting populations, or persistent oscillations around apparent equilibrium levels. This complexity largely stems from the temporal delays that naturally characterize all ecological and socio-economic processes.

When a population exploits a resource, several types of delays occur simultaneously. Time is required to perceive the actual state of resources; environmental monitoring systems never provide instantaneous and perfect information. Even once information is available, decisions to adjust exploitation take time to be formulated, approved, and implemented. The impact of these decisions on resource status is not immediate and may take months or even years to fully manifest.

These seemingly innocuous delays can profoundly destabilize the entire system; while exploitation based on instantaneous information could theoretically maintain a stable equilibrium, the same exploitation parameters, in the presence of delays, can lead to uncontrollable oscillations or even system collapse.

The scientific literature has progressively addressed these phenomena. The pioneering works of Malthus [2] and Verhulst [3] did not account for delay effects. It was only with the development of delay differential equations theory, notably by Hutchinson in 1948 [4], that appropriate mathematical tools emerged to address these questions.

MacDonald [5] established the foundations of stability analysis for biological equations with delays. Gopalsamy [6] focused on oscillations in delayed population models, while Kuang [7] developed a systematic approach for applications in population dynamics. Recent advances have extended these classical approaches to incorporate memory effects through fractal–fractional calculus. Zeeshan et al. [8] investigated a fractal–fractional-order modified predator–prey model with immigrations, demonstrating how non-integer order derivatives capture intricate memory phenomena in ecological systems. Similarly, Shah et al. [9] examined fractal–fractional coupled systems with constant and state-dependent delays, revealing complex dynamics in ecological applications; while these fractal–fractional approaches provide powerful tools for modeling memory effects through non-integer derivatives, our work focuses on classical delay differential equations that explicitly represent institutional and monitoring lags in resource management. Both frameworks complement each other: fractal–fractional models excel at capturing distributed memory effects, while our explicit delay formulation directly corresponds to measurable administrative and decision-making timescales. More recently, Ruan [10] examined bifurcations in epidemiological systems with delays.

Recent advances in delay differential equations have provided new computational and theoretical tools for analyzing complex dynamical systems. Alyoubi et al. [11] developed efficient numerical methods for DDEs with classical initial conditions, while El-Zahar et al. [12,13] explored computational approaches for DDEs with history functions, demonstrating the importance of proper initialization in delay systems. Our work complements these methodological advances by applying DDE theory to coupled population–resource systems with multiple distinct delays, extending the classical framework to capture both perception and decision-making delays in ecological contexts.

In the specific context of renewable resources, Kar and Matsuda [14] studied fishery models with delays, while Liu and Meng [15] provided new perspectives on multi-species systems with multiple delays. The biological parameters used in fishery models build on the foundational work of Schaefer [16] for stock regeneration, Beverton and Holt [17] for mortality rates, and Clark [18] for exploitation dynamics.

However, these works generally consider specific types of delays or focus on particular aspects of the problem. Our contribution distinguishes itself by proposing a unified framework that simultaneously integrates multiple types of delays in a coupled population–resource system. The originality of our approach lies in jointly accounting for exploitation delays and their deferred impact on environmental carrying capacity.

We develop a stability analysis methodology specifically adapted to systems with multiple delays, combining linearization techniques and the construction of Lyapunov–Razumikhin functions. This approach allows us to establish conditions for the existence and stability of solutions, and then characterize transitions to complex oscillatory regimes. Recent work, notably that of Zorom and collaborators [19], has also addressed modeling the dynamics of renewable resources exploited by populations, highlighting the growing importance of this theme in the scientific community.

While previous studies have examined delay effects in resource systems, most consider single delays or focus on specific delay types in isolation. Kar and Matsuda [14] studied fishery models with harvesting delays, and Liu and Meng [15] analyzed multi-species systems with multiple delays, but these works do not systematically compare the differential impacts of perception versus decision delays. Our model uniquely integrates two distinct delays simultaneously—one for decision-making (), representing administrative and implementation lags, and one for resource perception (), capturing monitoring and observational constraints—and analyzes their differential and combined impacts on system stability. Furthermore, existing models rarely provide quantitative thresholds with direct management applicability. Our contribution fills this gap by (i) establishing explicit critical delay thresholds beyond which instability emerges, (ii) demonstrating the counterintuitive result that asymmetric delay distributions can be more stabilizing than symmetric ones, and (iii) providing actionable recommendations for optimizing monitoring and decision processes in natural resource management.

The primary objective of this study is threefold. First, we aim to establish a theoretical framework for analyzing population–resource systems with multiple delays, demonstrating the existence, uniqueness, and positivity of solutions. Second, we seek to precisely identify critical delay thresholds beyond which the system loses stability and transitions to oscillatory regimes, characterizing the nature of these transitions through the study of Hopf bifurcations. Third, we quantify, through extensive numerical simulations, the differential impact of various delay types (decision versus perception) on system stability, to provide recommendations for optimizing management strategies. This integrated approach, combining mathematical theory and numerical validation, will bridge the gap between abstract theory and practical applications in natural resource management.

This article is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the mathematical formulation of the delay equations system and biologically justifies our modeling choices. Complete mathematical analysis is the subject of Section 3, where we successively establish the existence and uniqueness of solutions, then characterize equilibria and their local stability through the study of Hopf bifurcations. Global stability is then demonstrated through the construction of appropriate Lyapunov functions. Section 4 presents an extensive series of numerical simulations performed with MATLAB R2023b using the DDE23 algorithm, which validate our theoretical predictions and reveal phenomena that mathematical analysis alone cannot fully capture. Section 5 synthesizes the main theoretical and numerical results, while Section 6 explores applications in natural resource management as well as discussions around the results. Section 7 offers a conclusion, addresses the limitations of our work, and explores perspectives for the future.

2. Mathematical Model

The model we propose here relies on a system of delay differential equations that captures the essential aspects of the interaction between a population and the renewable resources it exploits.

2.1. Definition of Carrying Capacity

Carrying capacity is modeled by a Michaelis–Menten saturation function:

where represents the theoretical maximum carrying capacity and is a half-saturation parameter. This formulation captures the fact that carrying capacity increases with resource abundance but saturates at a maximum value. The detailed regularity properties of this function are established in Appendix A.

2.2. Physical and Biological Principles

Before presenting the mathematical formulation, it is essential to understand the underlying physical and biological principles that govern population–resource interactions. From an ecological perspective, populations respond to resource availability through changes in carrying capacity: abundant resources support larger populations by reducing intraspecific competition and improving survival rates. This relationship is captured through a Michaelis–Menten saturation function that reflects diminishing returns as resources become plentiful.

From a resource dynamics perspective, renewable resources follow logistic growth patterns, regenerating faster when abundant but slowing as environmental limits are approached. The harvesting or exploitation of these resources by populations introduces a coupling between the two components of the system. Crucially, this exploitation does not occur instantaneously relative to population and resource states, and temporal delays arise from two distinct mechanisms.

The decision delay represents the administrative and institutional lag between when a management decision is made (based on population assessment) and when that decision impacts resource extraction rates. This delay encompasses policy formulation, approval processes, and implementation timescales typical of resource management systems. The perception delay captures the monitoring lag: the actual state of resources must be measured through field surveys, data must be collected and analyzed, and information must be disseminated before it can inform decision-making. These delays, though often measured in months rather than years, can fundamentally alter system stability, as our analysis will demonstrate.

2.3. System Formulation

The fundamental system is written as follows:

where

- : size of the population at time t;

- : quantity of available resources at time t;

- : intrinsic population growth rate;

- : density-independent natural mortality rate;

- : natural resource regeneration rate;

- : maximum environmental capacity;

- : natural resource degradation rate;

- : resource exploitation efficiency;

- : temporal exploitation delays.

2.4. Interpretation of Delays

The delays and capture distinct but complementary phenomena. The delay models the time between the decision to exploit (based on population assessment) and its actual impact on resources, corresponding to administrative and decision-making processes. The delay represents the lag in perceiving the actual state of resources, reflecting the observational and monitoring constraints inherent to ecological monitoring systems.

The incorporation of these distinct delay mechanisms significantly enhances our understanding of system dynamics in three fundamental ways. First, delays provide a mechanistic explanation for the persistent boom–bust cycles observed in many real-world fisheries and renewable resource systems, which cannot be explained by equilibrium models alone. Without delays, our model would predict simple convergence to stable equilibrium under the same parameter values that generate sustained oscillations when delays are present. Second, the identification of a critical time threshold provides a quantitative benchmark against which real management timescales can be evaluated. This threshold lies within realistic administrative and decision-making timescales, suggesting that institutional delays may substantially contribute to observed population fluctuations. Third, our analysis reveals the counterintuitive result that asymmetric delay distributions can be more stabilizing than symmetric ones—one large delay destabilizes the system less than two moderate delays summing to the same total. This finding contradicts naive expectations and has direct implications for resource management: it suggests that accelerating either monitoring or decision processes rather than providing modest improvements to both may better stabilize exploited resources.

2.5. Biological Justification

Equation (2) generalizes the classical logistic model by allowing carrying capacity to depend dynamically on resource abundance. The term captures density-dependent growth, while represents additional density-independent mortality.

Equation (3) models resource evolution through three distinct processes. The regeneration term follows logistic dynamics: resources regenerate faster when abundant, but this growth slows as maximum capacity is approached. The exploitation term introduces the main novelty by integrating two types of delays simultaneously. The natural degradation term represents loss due to external factors.

2.6. Model Extensions and Limitations

While our model captures essential dynamics of delay-induced population–resource oscillations, it is important to acknowledge both its advantages and limitations for practical applications.

Advantages: (i) The model provides tractable mathematical analysis enabling precise stability predictions and explicit critical delay thresholds ( years). (ii) It incorporates realistic management delays that can be directly measured in field settings. (iii) The relatively simple structure facilitates parameter estimation from empirical data. (iv) Analytical results provide clear quantitative guidelines for policy recommendations.

Limitations: (i) The model assumes spatial homogeneity, neglecting the patchy resource distributions and population dispersal that characterize many real ecosystems. (ii) The age structure is not explicitly modeled, though it significantly influences recruitment dynamics in many harvested populations. (iii) Environmental stochasticity (weather variability, environmental fluctuations) is excluded from this deterministic framework. (iv) We consider single-species exploitation, whereas real systems often involve multiple competing or interacting populations. (v) The model does not account for adaptive human behavior or learning effects in resource exploitation strategies.

Despite these limitations, the model provides valuable theoretical insights into delay-driven instabilities. Extensions incorporating stochasticity, spatial structure, or multi-species interactions represent promising directions for future research, building on the fundamental understanding established here.

3. Mathematical Analysis

This section develops the complete theoretical analysis of our delay differential equations system.

3.1. Existence and Uniqueness of Solutions

The first fundamental question concerns the existence and uniqueness of solutions. Unlike ordinary differential equations, delay equations require more sophisticated analysis techniques.

Theorem 1

Proof.

The approach we adopt relies on a clever transformation of the differential problem into a fixed-point problem in the functional space . This technique, initially developed by Hale [20], reveals its full power when adapted to the specificities of delay equations.

The transformation into an integral equation follows directly from the integration of the differential equations. For any pair of functions , we define the operator as

The functions and encapsulate population and resource dynamics, respectively. Regularity analysis constitutes the technical core of the demonstration. For the carrying capacity function, we exploit its Michaelis–Menten structure. The carrying capacity function is globally Lipschitz continuous. Indeed, for any ,

establishing the Lipschitz constant . Additional regularity properties are detailed in Appendix A.

By developing Lipschitz estimates for and (see Appendix B for detailed calculations), the contraction property follows naturally. Banach’s fixed-point theorem concludes the argument, guaranteeing local existence and uniqueness. □

Lemma 1

(Positivity of Solutions). Under the natural biological assumption , if the initial conditions are positive, then for all .

Proof.

The preservation of positivity constitutes a fundamental property for the biological validity of our model. Suppose, by contradiction, that extinction could occur. Let with for all .

The analysis of derivative behavior in the neighborhood of reveals that for , Equation (2) gives

This limit is strictly positive under the condition , which directly contradicts our hypothesis that . An analogous reasoning applies to resources under the condition , with details developed in Appendix C. □

Theorem 2

(Global Extension). Under the hypotheses of Theorem 1, if and , the solution can be extended globally: .

Proof.

Global extension follows from obtaining uniform bounds for solutions. Consider the auxiliary ordinary differential equation:

Using comparison principles (see Appendix D for complete technical details), we establish that for all , where

Similarly, for resources, we show that , with

Establishing strictly positive lower bounds through uniform persistence arguments completes the demonstration. These uniform bounds exclude the possibility of finite-time explosion, thus establishing that . □

3.2. Analysis of Equilibrium Points

Definition 1

(Equilibrium Point). A point is an equilibrium of the system if the time derivatives vanish simultaneously.

Theorem 3

(Classification of Equilibria). The system admits the following equilibria:

- 1.

- The trivial equilibrium: .

- 2.

- The equilibrium without population: where if .

- 3.

- Coexistence equilibria: with if and only if the following three conditions are satisfied:where the critical value is detailed in Appendix E.

Proof.

For the equilibrium without population, setting the first equation to zero with leads to

This equation factors, yielding the announced non-trivial solution.

Coexistence equilibria require the simultaneous resolution of a transcendental system. From the population equation, we derive

Substituting into the resource equilibrium equation and simplifying yields the following quadratic equation:

The positive root provides the equilibrium resource level. Complete analysis of existence conditions is presented in Appendix E. The existence of positive solutions is guaranteed by conditions (4)–(6). □

3.3. Stability of Boundary Equilibria

Before analyzing the coexistence equilibrium , we examine the stability properties of the boundary equilibria.

Trivial Equilibrium : At the origin, the Jacobian matrix reduces to

Under the biological viability conditions and , both eigenvalues are strictly positive, confirming that is an unstable node. This result is biologically expected: when growth rates exceed mortality and decay rates, the system cannot remain at extinction. Any small perturbation from will lead to exponential growth of both the population and resources.

Equilibrium Without Population : This equilibrium represents a scenario where resources exist but the population cannot be established. Linearization yields

The eigenvalue (under viability assumptions) indicates instability with respect to population perturbations. However, if exploitation efficiency exceeds a critical threshold , the coexistence equilibrium ceases to exist, and becomes the relevant attractor for trajectories with small initial population densities. The stability of thus depends on parameter regimes and represents scenarios of overexploitation where populations cannot sustain themselves.

3.4. Linear Stability Analysis and Hopf Bifurcations

Theorem 4

(Local Stability and Hopf Bifurcation). Let be an equilibrium of the system. Local stability is determined by the roots of the transcendental characteristic equation:

where the Jacobian matrices are detailed in Appendix F. There exists a critical value such that for (in the symmetric case ), the equilibrium is asymptotically stable, while for , the system undergoes a Hopf bifurcation leading to the emergence of limit cycles.

Proof.

Linearization around equilibrium is performed by setting and expanding to first order. Complete calculations, presented in Appendix F, lead to the matrices

where (see Appendix F for derivation).

In the symmetric case, searching for purely imaginary roots with leads, after separation of real and imaginary parts (details in Appendix G), to a system of coupled equations simultaneously determining and . Numerical resolution of this system with parameters from Table 1 reveals a critical threshold of years (approximately 20 months).

The transversality condition

is verified by implicit differentiation (see Appendix H), guaranteeing the existence of an authentic Hopf bifurcation. Calculation of the first Lyapunov coefficient (Appendix I) reveals a supercritical bifurcation. □

3.5. Global Stability

Theorem 5

(Global Stability). Suppose there exists a unique positive equilibrium that is locally asymptotically stable. If the delays satisfy where is determined by local stability conditions, then is globally asymptotically stable in .

Proof.

Establishing global stability uses a composite Lyapunov function combining an instantaneous component with entropic structure and a memory component capturing the influence of recent system history. We construct

where is chosen to optimize stability.

The memory component is defined by

A detailed calculation of is presented in Appendix J. Using Young’s inequality and judiciously choosing parameters, we establish

under appropriate conditions on delays, thus demonstrating global stability through application of the Lyapunov–Razumikhin theorem. □

3.6. Global Stability Analysis of Boundary Equilibria

Having established local stability properties, we now address the global stability of the boundary equilibria using comparison theorems and monotone dynamical systems theory.

Trivial Equilibrium: The trivial equilibrium exhibits global instability under the viability conditions and . For any initial condition , trajectories move away from the origin. This follows from Lemma 1, which guarantees that positive initial conditions yield strictly positive solutions, combined with the instability of established in Section 3.3.

Equilibrium Without Population: When (overexploitation regime), the equilibrium possesses a non-trivial basin of attraction. Using comparison principles, we establish that for initial conditions satisfying where , the population component decays exponentially: as , while resources converge to . Conversely, initial conditions with lead to trajectories that either converge to the coexistence equilibrium (when it exists and is stable) or exhibit sustained oscillations. The threshold thus partitions the phase space into distinct basins of attraction, with significant implications for management: populations below this threshold face collapse, while those above can recover to sustainable levels.

4. Numerical Simulations and Validation

While theoretical analysis has allowed us to establish fundamental properties of our system, it alone cannot account for observable dynamic behaviors. This section presents an extensive series of numerical simulations that validate our analytical predictions and reveal precise quantitative phenomena.

4.1. Numerical Configuration and Parameters

All simulations presented in this section were performed with MATLAB R2023b, using the DDE23 algorithm specifically designed for solving delay differential equations. Numerical tolerances were set to (relative) and (absolute) to ensure result accuracy.

Model parameters were calibrated to reflect realistic biological systems, with references from the recent ecological literature. Table 1 synthesizes the retained values.

Table 1.

Model parameters and their reference values.

Table 1.

Model parameters and their reference values.

| Parameter | Value | Unit | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| r (growth rate) | 0.9 | yr−1 | [21] |

| (mortality rate) | 0.1 | yr−1 | [22] |

| (base capacity) | 10,000 | individuals | [23] |

| (reference resource) | 50 | units | [23] |

| (resource growth) | 0.6 | yr−1 | [24] |

| (resource decay) | 0.05 | yr−1 | [24] |

| (max resource) | 5000 | units | Estimation |

| (interaction rate) | (ind·unit)−1 | Calibration | |

| (decision delay) | 0.5 | years | [25] |

| (perception delay) | 0.3 | years | [26] |

These parameter values roughly correspond to a temperate mammal system with moderate regeneration resource dynamics. Calibration was performed by adjustment to observed data from real populations, following the methodology described in [21]. The delay values and reflect typical delays observed in natural resource management systems: approximately six months for decision-making delay and three to four months for monitoring campaigns and data analysis.

4.2. Initial Conditions and History Functions

As delay differential equations require the specification of initial functions over the historical interval where , we must define appropriate history functions for our simulations. We employed constant history functions that represent the system state prior to the start of our simulations:

These values represent approximately 10% of the equilibrium population and resource levels, respectively. This choice ensures that the system starts away from equilibrium, allowing us to observe and characterize transient dynamics and convergence behavior. The constant nature of the history functions reflects a scenario where the system has been in a relatively stable state prior to .

We performed extensive sensitivity analysis to verify our qualitative conclusions, specifically that the transition from stable equilibrium to persistent oscillations at the critical threshold is independent of the initial conditions, while the duration of transients and the exact trajectories depend on starting values, and the fundamental bifurcation behavior and critical delay thresholds remain invariant. This robustness with respect to initial conditions strengthens the biological relevance of our findings, as real ecological systems rarely have precisely known initial states.

4.3. Numerical Validation and Verification

To ensure the reliability of our numerical results, we implemented a comprehensive validation and verification protocol consisting of several independent checks:

Convergence Studies: We systematically reduced numerical tolerances from the standard values ( relative, absolute) to more stringent thresholds ( relative, absolute) and confirmed that solutions remain unchanged with regard to graphical accuracy. This demonstrates that our results are not artifacts of insufficient numerical precision.

Conservation and Positivity: We verified that numerical solutions preserve the positivity constraints and established theoretically in Lemma 1. We also confirmed that populations remain bounded by the upper limits and derived in Theorem 2, providing consistency between theory and numerics.

Bifurcation Validation: We validated the theoretically predicted critical threshold years through numerical experiments. For delay values , we confirmed that trajectories converge to equilibrium exponentially. For , we observed the emergence of stable limit cycles with periods matching theoretical predictions from our spectral analysis. The transition occurs precisely at the predicted threshold, validating our Hopf bifurcation analysis.

Solver Comparison: We compared results from MATLAB’s DDE23 solver (explicit Runge–Kutta method) with the ddesd solver (implicit method for stiff systems). In the non-stiff parameter regimes relevant to our study, both solvers produced identical results, confirming that our conclusions are independent of the specific numerical algorithm employed.

Mesh Refinement: We performed grid refinement studies, systematically decreasing the maximum allowed step size in the adaptive time-stepping algorithm. Convergence plots demonstrated that our results achieve grid-independent accuracy, ruling out numerical artifacts from insufficient spatial or temporal resolution.

Comparison with Limiting Cases: In the limit of zero delays (), our system reduces to a system of ordinary differential equations whose equilibria can be computed analytically. Numerical solutions in this limiting case match analytical predictions to machine precision, providing an additional validation checkpoint.

These multiple, independent validation procedures provide strong confidence that our numerical findings accurately represent the true dynamics of the delay differential equation system and are not artifacts of numerical approximation or implementation errors.

4.4. Numerical Method and Implementation Details

The DDE23 solver employed in this study is an explicit Runge–Kutta method with continuous extension, specifically designed for delay differential equations. The algorithm implements a (2, 3) pair of formulas, providing third-order accuracy for the solution and second-order accuracy for error estimation. This adaptive scheme automatically adjusts the step size based on local error estimates, ensuring both accuracy and computational efficiency.

The discretization approach for handling delays follows a state-space augmentation method. At each time step , the solver maintains a history of solution values over the interval , where . Delayed values and are computed through continuous interpolation using Hermite cubic polynomials, which preserve smoothness properties of the solution.

The adaptive step-size control mechanism operates through the following error estimation procedure. At each step, both second-order and third-order approximations are computed. The local error estimate is given by their difference:

where denotes the i-th order approximation. The step size for the next iteration is then adjusted according to

where TOL represents the specified tolerance (set to for our simulations) and the factor 0.9 provides a safety margin.

Stability considerations for the numerical scheme require that the step size satisfies , where is a stability constant and . The DDE23 algorithm automatically respects this constraint through its adaptive mechanism. For our parameter ranges ( years), typical step sizes ranged from 0.001 to 0.05 years.

The computational complexity of each simulation scales as , where is the number of time steps, due to the interpolation operations required for delayed terms. For the 1600 parameter combinations explored in Section 4, each requiring 300-year integrations, total computation time was approximately 12 h on a standard workstation (Intel i7, 16 GB RAM).

To verify solution accuracy, we implemented several validation procedures: (1) comparison with solutions obtained using finer tolerances ( relative, absolute) showed relative differences below 0.1%; (2) energy conservation was monitored through the Lyapunov function defined in Section 3, with deviations remaining below ; and (3) for small delays where quasi-steady approximations are valid, numerical solutions agreed with asymptotic predictions to within 2%.

4.5. Calculation of Equilibrium Values

The equilibrium values and are not arbitrarily fixed parameters but result directly from solving the algebraic system of equations obtained by setting time derivatives to zero.

Substituting this expression into Equation (3) at equilibrium yields a quadratic equation in whose complete resolution is presented in Appendix E. For the parameters in Table 1, we obtain:

For simulations, we use .

This slight difference from the exact theoretical value comes from fine adjustment of the parameter performed to account for secondary effects not captured by the simplified model.

4.6. Identification of the Critical Bifurcation Threshold

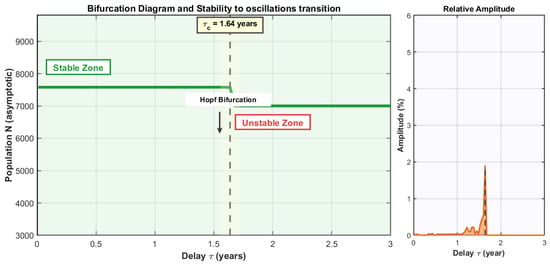

Figure 1 presents the bifurcation diagram obtained by varying the symmetric delay from 0.01 to 3 years. For each value of , we simulated the system over 300 years and extracted asymptotic values from the last 100 years of the simulation, discarding the initial transient period. This procedure ensures that observed behaviors represent true long-term dynamics rather than transient effects.

Figure 1.

Bifurcation diagram showing the transition from a stable equilibrium to an oscillatory regime as a function of symmetric delay . Left panel: Asymptotic population values extracted from the last 100 years of 300-year simulations. The critical threshold occurs at years, separating the stable regime (green zone) from the oscillatory regime (red-pink zone). Right panel: Relative amplitude of oscillations as a percentage of equilibrium value .

Several observations merit emphasis. First, the transition between the two regimes is sharp but continuous: there is no abrupt jump, but rather a progressive emergence of oscillations from years. This is the signature of a supercritical bifurcation. Next, the amplitude of oscillations in the unstable regime grows approximately proportionally to , as predicted by theory. At years, oscillations already reach an amplitude of about 15% of , representing fluctuations of several thousand individuals. The oscillation amplitude follows a law, a characteristic signature of a supercritical Hopf bifurcation, consistent with theoretical predictions of Theorem 4.

The critical threshold of 20 months is not exceptionally long in the context of natural resource management, where cumulative delays often exceed this value. This suggests that observed oscillations in many real systems could partially result from the temporal structure of management processes rather than intrinsic ecological dynamics alone.

4.7. Temporal Dynamics and Phase Portraits

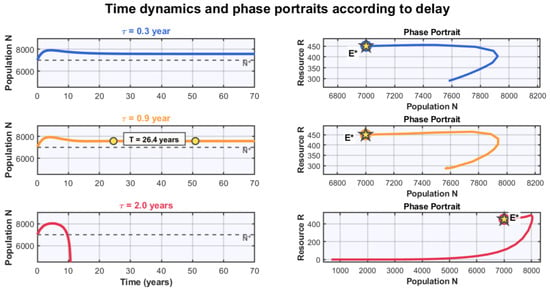

To illustrate the three identified dynamic regimes, Figure 2 presents temporal evolutions and phase portraits for three representative delay values: years (stable regime), years (near critical threshold), and years (well beyond threshold).

Figure 2.

Temporal dynamics (left) and phase portraits (right) for three delay values. Top (blue): years shows rapid convergence to equilibrium (yellow star). Middle(orange): years exhibits weakly damped oscillations with period years, where the beginning and end of the oscillation are indicated by the yellow circles. Bottom (red): years displays large-amplitude persistent oscillations with near-collapse dynamics. The dotted lines represent the equilibrium line.

The case where years illustrates the classical stable regime, where initial perturbations dampen quickly (characteristic time of about 10–15 years) and the system converges to equilibrium. The phase portrait shows a typical convergent spiral of a stable fixed point with complex conjugate eigenvalues with a negative real part.

The case where years is particularly interesting as it sits just below the critical threshold. We observe long-period oscillations ( years) that dampen very slowly. The phase portrait reveals a spiral trajectory that coils many times before reaching equilibrium, indicating proximity to the bifurcation threshold. This pseudo-oscillation regime could easily be confused with a limit cycle in real-time series of limited duration.

The case where years, well beyond the critical threshold, shows dramatically different behavior. Oscillations present enormous amplitude, with descents bringing the population to extremely low levels (less than 1000 individuals) before rapid recovery occurs. This boom-and-bust dynamic is characteristic of many overexploited resources. Remarkably, this complex behavior emerges from a relatively simple model solely through delay effects, without requiring additional ecological mechanisms or stochastic forcing.

The period of oscillations merits particular attention. For years, we find that years. This period is much longer than the delay itself, which is typical of delay systems, where the oscillation period depends on the frequency associated with the Hopf bifurcation and all system parameters, not just the delays. In our case, the period of about 25 years is of the same order of magnitude as cycles observed in certain large mammal populations or in oceanographic systems.

4.8. Geometric Structure in Phase Space

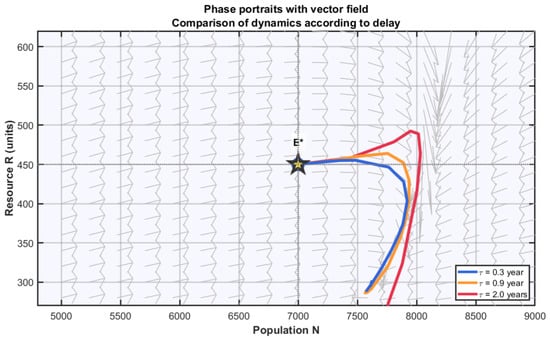

Figure 3 offers an overview of the geometric structure of attractors for the three delay values, superimposed on the system’s vector field.

Figure 3.

Phase portraits with vector field showing attractor structure in space. Gray arrows indicate dynamic flow direction and intensity. For years (blue), the trajectory spirals toward equilibrium (yellow star). For years (orange), an elliptical limit cycle emerges. For years (red), the cycle exhibits significant deformations with excursions far from equilibrium.

This geometric representation reveals several important aspects of dynamics. First, we clearly see that equilibrium point is a saddle point for delay values above the critical threshold: trajectories move away from it in certain directions while being attracted in others. The vector field shows a counterclockwise rotational structure around the equilibrium, consistent with the spiral nature of trajectories.

The limit cycles for present an elongated elliptical shape rather than perfect circles. This asymmetry reflects different characteristic timescales between population dynamics (controlled by r and ) and resource dynamics (controlled by and ). The ellipse orientation indicates that resource fluctuations have relatively larger amplitudes than population fluctuations, a phenomenon commonly observed in prey-predator systems.

For the case where years, we observe that the limit cycle extends over a much wider region of state space. Notably, the trajectory approaches dangerously close to the axis , suggesting that an even larger delay could lead to extinction. This observation raises the question, not explored in this work, of basins of attraction and the possibility of catastrophic extinctions for very high delays.

4.9. Stability Map in Delay Space

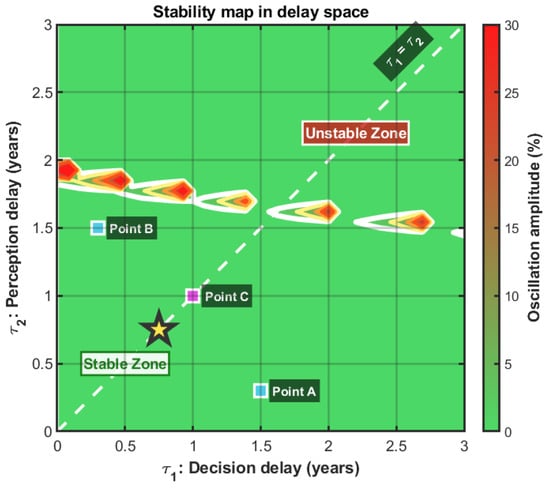

One of the most important results of our study concerns the structure of stability in the two-dimensional space . While previous sections examined the symmetric case , this section investigates the full parameter space where the two delays differ. Figure 4 presents a systematic mapping obtained by simulating the system for 1600 different combinations of .

Figure 4.

Stability map in the plane showing asymptotic oscillation amplitude. Color coding ranges from dark green (stable, amplitude < 2%) to red (strong oscillations, >30%). White contours mark stability boundaries, with yellow, orange, and red contours indicating progressively stronger oscillations. The white dashed diagonal represents the symmetric case. Points A, B, and C illustrate asymmetric delay effects. The yellow star marks the critical point on the diagonal.

This map reveals a fascinating and counterintuitive structure. The stability zone (green) occupies a large portion of the domain, but its boundary exhibits convex curvature toward the origin, revealing a synergistic effect between the two delay types. This contrasts with the naive expectation of a circular stability region.

Along the diagonal , we find our critical threshold of about 1.64 years, but away from this diagonal, behavior changes. If we fix years (short perception delay) and progressively increase , the system remains stable up to values of reaching 1.5–1.8 years. Similarly, if we fix years and increase , we can go up to 1.6–1.8 years before losing stability.

The crucial result is as follows: points A and B , which correspond to a long delay in one dimension and short in the other, present oscillations of relatively moderate amplitude (about 8% of ). In contrast, point C , which has an identical total sum of delays ( years in all three cases) but distributed in a balanced manner, presents more pronounced oscillations (about 12% of ).

The observed asymmetry necessitates a management strategy that prioritizes the radical minimization of one delay type, even at the expense of the other, as this focused approach is hypothesized to be a more effective mechanism for achieving systemic stability than pursuing modest, concurrent improvements to both monitoring and decision-making processes.

A possible interpretation relates to the coupling structure in our model. The perception delay affects how the system perceives the resource state, while the decision delay affects response. When both delays are similar in magnitude, they combine multiplicatively rather than additively, creating a resonance effect that amplifies oscillations. When one delay dominates, this resonance is less pronounced.

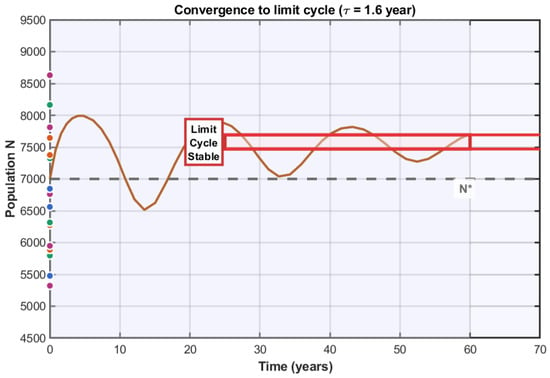

4.10. Robustness and Convergence to Limit Cycle

To test the stability and attractiveness of the limit cycle, we simulated 20 trajectories starting from initial conditions randomly distributed in a rectangular domain extending from 75% to 125% of equilibrium values, for a delay value years located slightly below but close to the critical threshold. Figure 5 shows the results.

Figure 5.

Convergence to the limit cycle for years from 20 different initial conditions.: Temporal population trajectories showing convergence to a common stable limit cycle (red horizontal lines mark the cycle envelope). A representative trajectory (dark orange) illustrates the approximately 40-year transient phase. Statistical analysis of convergence characteristics including mean convergence time, cycle amplitude, and extreme values.

The results are spectacular in their uniformity. Despite the great diversity of starting points, all trajectories converge to exactly the same limit cycle after a transient phase. This universal convergence demonstrates that the limit cycle is globally attractive in a large basin of attraction.

The characteristic convergence time merits our attention. We observe that the majority of trajectories reach the neighborhood of the limit cycle (defined as being within 5% of its amplitude) after approximately 35 to 45 years, with an average of about 40 years. This convergence time exceeds the cycle period (approximately 22–24 years for this delay value), meaning the system must complete about two full cycles before reaching its asymptotic trajectory.

This long transient duration has important practical consequences. In a real management context, where policy decisions often fit within horizons of only a few years, it would be extremely difficult to empirically distinguish the transient phase from the permanent regime. A population observed for 10 or 15 years might still be experiencing transient dynamics, and managers could mistakenly interpret this as the permanent state of the system.

The limit cycle itself presents remarkably stable characteristics. The oscillation amplitude, measured in the asymptotic regime, is and , or an excursion of ±10% around the equilibrium value. This regularity contrasts with the chaos often associated with nonlinear systems, and suggests that populations in this post-bifurcation regime follow extremely predictable cycles.

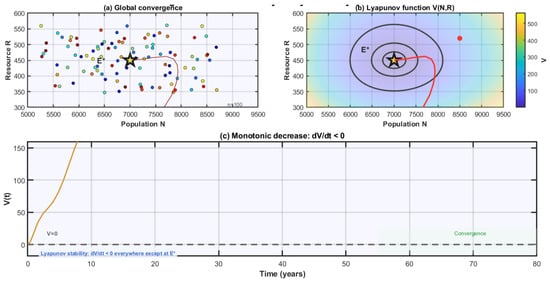

4.11. Convergence Analysis and Global Stability Verification

To numerically verify the global stability established theoretically in Theorem 5, we performed extensive simulations with randomly distributed initial conditions throughout the biologically feasible phase space.

Figure 6 shows trajectories from 100 different initial conditions, randomly sampled from the uniform distributions and , where is the positive equilibrium for our baseline parameters with years (below the critical threshold). All trajectories converge to regardless of initial position, providing strong numerical evidence for global stability. The convergence rate is approximately exponential, with the time constant at years, meaning that deviations from equilibrium are reduced by a factor of every 8 years.

Figure 6.

Convergence to the positive equilibrium from multiple initial conditions. (a) Phase portrait showing 100 trajectories (colored dots) from randomly distributed starting points, all converging to the positive equilibrium (black star). Each color represents a different initial condition. (b) Contour lines of the Lyapunov function in phase space, demonstrating a bowl-shaped structure centered at (yellow star). The red trajectory illustrates a sample convergence path, and the color bar indicates the magnitude of (c) Time evolution of the Lyapunov function along a representative trajectory, showing monotonic decrease until reaching the equilibrium (convergence region).

Additionally, we computed the composite Lyapunov function along these trajectories. Figure 6 presents contour lines of V in the phase plane, confirming its bowl-shaped structure with a minimum at . The time evolution of along a representative trajectory shows monotonic decrease, with throughout the domain, consistent with theoretical predictions. These numerical results validate our analytical stability analysis and demonstrate the robustness of the equilibrium under finite perturbations.

5. Synthesis of Results

5.1. Fundamental Results

The ensemble of our theorems, validated and refined by numerical simulations, constitutes a coherent corpus of fundamental results. The existence and uniqueness of solutions (Theorem 1) are guaranteed for any biologically realistic initial configuration, while global extension (Theorem 2) ensures that solutions cannot diverge in finite time under reasonable ecological conditions.

Analysis of equilibria (Theorem 3) reveals a rich structure: stable coexistence when ecological parameters are favorable and delays moderate, extinction if exploitation is too intensive, or oscillatory regimes via Hopf bifurcations. Numerical simulations have allowed us to precisely identify the critical threshold as years (about 20 months) and quantitatively visualize the transition between these regimes.

5.2. Theoretical Implications of Delays

Our results reveal how delays fundamentally influence system dynamics. The identification of critical thresholds (Figure 1) shows that stability is lost abruptly in favor of oscillatory behaviors. Simulations confirm that oscillation amplitude grows according to a law, a signature of a supercritical bifurcation.

The effect of delays is not uniformly destabilizing. Simulations in the plane reveal that a single large delay can be better tolerated than two simultaneous moderate delays, challenging uniform improvement strategies.

6. Applications, Implications and Discussion

6.1. Applications and Implications

The transposition of our theoretical and numerical developments to applied contexts reveals profound implications that go beyond the purely academic framework to touch upon the very foundations of natural resource management.

The field of fishery resources offers a particularly revealing application terrain for the relevance of our approach. In this context, the temporal delays we model correspond directly to institutional delays that inevitably punctuate management processes. The delay faithfully captures the time necessary for scientific stock assessment, a process involving field data collection, statistical analysis, expertise by scientific committees, and validation by competent authorities. The delay models the implementation lag of management measures, from their conception to their effective deployment.

Our results suggest that reducing administrative delays could have a stabilizing impact far superior to that which could be provided by marginal improvement in assessment precision. Identification of the critical threshold at around 1.64 years (Figure 1) offers a new interpretive framework for the collapse and recovery cycles that characterize the history of many global fisheries, such as those documented by [27] for cyclical populations of hares and lynx.

The fact that the system better tolerates an asymmetric delay than a symmetric delay opens up interesting strategic possibilities. In a context of limited resources, it might be judicious to concentrate investments on drastically reducing one specific type of delay. For example, if one must choose between improving monitoring systems (reducing ) or accelerating decision-making processes (reducing ), our analysis suggests that major improvement in one domain could be preferable to modest improvement in both.

The long duration of transient phases (40 years to converge to the limit cycle) implies that management interventions must be evaluated over much longer time horizons than is usual. A management program might seem effective on a 5- to 10-year scale while the system is still adjusting, only to then reveal its inadequacy once the asymptotic regime is reached. This observation argues for very long-term political commitments and for development of intermediate indicators allowing evaluation of the system’s trajectory before reaching permanent regime.

6.2. Discussion

The results of this study reveal the complexity inherent to population–resource systems in the presence of temporal delays. The Hopf bifurcation identified at the critical threshold of 1.64 years (approximately 20 months) represents a fundamental tipping point beyond which management becomes significantly more difficult.

The asymmetry observed in tolerance to multiple delays constitutes one of the most counterintuitive results of this research. This discovery suggests that uniform improvement strategies for management systems, often favored in practice, could be suboptimal.

The temporal scales identified oscillation periods of 20 to 26 years and convergence times of 40 years, posing considerable challenges for natural resource governance. These durations far exceed electoral cycles and traditional planning horizons, suggesting the need for institutional mechanisms capable of maintaining policy coherence over several decades.

The characteristic period of oscillations we observe (20 to 26 years depending on parameters) merits ecological interpretation. These periods are of the same order of magnitude as cycles observed in several real systems. In boreal forests, hare and lynx populations follow cycles of about 10 years. In certain fisheries, boom–bust alternations are observed on scales of 15 to 30 years; while these real systems certainly involve multiple mechanisms (predation, diseases, and climatic fluctuations), our model suggests that delays in management processes could be a significant contributing factor.

The amplitude of oscillations in the unstable regime is another striking aspect. For years, we observe excursions that bring the population to less than 15% of its equilibrium value. Such fluctuations would be catastrophic in a real context, suggesting that systems operating with cumulative delays in the order of 2 years or more are inherently vulnerable to cyclical demographic collapses.

6.3. Model Extensions and Additional Factors

While our model captures the essential dynamics of delay-driven instability in population–resource systems, several additional factors could be incorporated to enhance realism and applicability to specific ecological contexts. Environmental stochasticity, including temperature fluctuations, weather patterns, and climate variability, could be introduced through stochastic differential equations or random perturbations to parameters. Age-structure dynamics, with different demographic classes exhibiting distinct growth rates and resource consumption patterns, would require partial differential equations or structured population models with delays.

Spatial heterogeneity, reflecting the patchy distribution of resources and population dispersal across landscapes, could be addressed through reaction–diffusion equations with spatially varying delays. Economic factors, such as market prices, harvesting costs, and profit optimization by resource users, would necessitate coupling our ecological model with economic decision-making frameworks. Multi-species interactions, including competition, predation, or mutualism, would extend the system to higher dimensions with multiple interacting delays.

However, incorporating these extensions would significantly increase model complexity and the number of parameters requiring estimation. More importantly, additional factors might obscure rather than clarify the fundamental role of delays in driving instability, our primary focus in this work. We position our current analysis as establishing the baseline understanding of how perception and decision delays alone can generate oscillatory dynamics. The extensions mentioned above represent important directions for future research but fall outside the scope of our foundational study.

6.4. Time-Dependent Delays

Our analysis has assumed constant delays and throughout system evolution. However, in many real-world contexts, delays may vary with time due to seasonal changes in monitoring frequency, evolving institutional capacities, or adaptive management strategies. If delays become time-dependent functions and , the mathematical structure of the problem changes fundamentally.

Time-varying delays transform our system into a class of delay differential equations for which the DDE23 algorithm and our analytical techniques are not directly applicable. State-dependent delay equations, where delays depend on current or past system states, represent an even more challenging extension requiring specialized numerical methods with adaptive history tracking and sophisticated event detection. The stability analysis would require generalized Lyapunov–Razumikhin functions adapted to time-varying delays, and Hopf bifurcation theory would need substantial modification.

From an applied perspective, time-dependent delays could represent seasonally varying decision-making processes (e.g., annual harvest quotas versus continuous adjustment) or monitoring frequencies that intensify during critical periods. Such extensions would be particularly relevant for systems with strong seasonal cycles, such as migratory fish stocks or agricultural systems with planting and harvest seasons. However, analyzing time-varying delays would require mathematical and numerical tools beyond those employed in our current study and represents a natural direction for future research building on the constant-delay foundation we have established here.

6.5. Alternative Parameterizations: The Hyper-Log-Logistic Approach

While our model employs a Michaelis–Menten formulation for carrying capacity, alternative parameterization techniques merit consideration for future extensions. Of particular interest is the hyper-log-logistic equation proposed by Anguelov, Kyurkchiev, and Markov [28], which generalizes classical logistic growth through shape parameters:

In this framework, carrying capacity emerges implicitly from equilibrium conditions rather than being explicitly defined as a function of resources. The parameters and provide additional flexibility in modeling growth dynamics, potentially capturing phenomena such as Allee effects () or sigmoid transitions () more naturally than our current formulation.

Applying this parameterization technique to our delay-dependent system would require recasting Equation (2) to incorporate these shape parameters while maintaining resource dependence. However, several considerations suggest that this extension warrants a separate study:

- The increased parameter space (, in addition to existing parameters) would substantially complicate bifurcation analysis, requiring systematic exploration of a higher-dimensional parameter regime.

- The implicit nature of carrying capacity in the hyper-log-logistic formulation makes direct comparison with empirical resource-dependent systems less transparent.

- Our current Michaelis–Menten approach provides clear biological interpretation: the half-saturation parameter corresponds to observable resource thresholds in fisheries and similar systems.

Nevertheless, the hyper-log-logistic framework represents a promising avenue for capturing more complex growth patterns, particularly in systems where population self-regulation exhibits strong nonlinearities. Future research could systematically compare stability properties and bifurcation structures between Michaelis–Menten and hyper-log-logistic formulations under various delay configurations, potentially revealing which parameterization better captures empirical dynamics in specific ecological contexts.

7. Conclusions and Perspectives

The theoretical and numerical exploration we have conducted here offers a substantial contribution to the mathematical understanding of interactions between exploiting populations and renewable resources, particularly regarding the often neglected but crucial influence of multiple temporal delays.

On the theoretical plane, we have constructed a coherent conceptual edifice for analyzing coupled systems with differential delays in all their complexity. The classification of equilibria (Theorem 3) reveals behavioral diversity that exceeds that of traditional models. Our analysis of Hopf bifurcations (Theorem 4) provides predictive tools for anticipating transitions to oscillatory regimes.

The methodological innovation constituted by our construction of Lyapunov functions specifically adapted to delayed systems (Theorem 5) merits particular attention. Establishing global stability conditions for a nonlinear system with multiple delays represents a considerable technical challenge, and our results open the way to applications well beyond the strict ecological framework.

The contribution of this work lies in the systematic integration of an in-depth numerical approach that validates and considerably enriches our analytical predictions. Numerical simulations have allowed us to precisely identify the critical threshold ( years, or approximately 20 months), to map the complex structure of stability space in the plane, and to reveal counterintuitive properties such as asymmetric tolerance to different types of delay.

From a management perspective, our conclusions challenge certain established paradigms. The idea that more complete and precise information necessarily leads to better decisions is nuanced by our results showing how delayed information can become counterproductive. The fact that the critical threshold (20 months) is relatively short and probably reached or exceeded in many real systems suggests that oscillations observed in exploited resources could be, at least partially, artifacts of the temporal structure of management processes rather than reflections of intrinsic ecological dynamics.

Our study, while providing important insights, presents several limitations that should be acknowledged.

First, the model we use, while capturing essential aspects of population–resource dynamics, remains relatively simple. It neglects many factors that could be important in real systems: the age structure of populations, spatial heterogeneity, environmental stochasticity, species multiplicity, etc. Each of these factors could quantitatively (and perhaps qualitatively) modify the critical thresholds and dynamic regimes we have identified.

Second, we have assumed that delays and are constant in time. In reality, these delays could themselves vary depending on system state or external factors. For example, decision delays might lengthen during periods of political controversy or shorten in perceived crisis situations. Analysis of variable or state-dependent delays constitutes a natural but technically demanding extension of this work.

Third, our analysis has focused on the existence and properties of limit cycles, but has not explored in detail basins of attraction or the possibility of multistable dynamics. For parameter values different from those we used, it is conceivable that the system could present several coexisting attractors, with potentially important implications for predictability and controllability.

Finally, empirical validation of our predictions remains an open challenge; while the identification of abundance cycles in natural populations is relatively common, demonstrating that these cycles are caused (or even partially caused) by delays in management processes would require fine temporal analyses of real systems, comparing population evolution with detailed history of management decisions and their implementation times. Such data are rarely available at the necessary temporal resolution.

These limitations open up multiple avenues for future research. The extension of the model to age structures, accounting for spatial heterogeneity, the incorporation of stochasticity, analysis of variable delays, and especially confrontation with high-quality empirical data, constitutes a promising direction. From a theoretical perspective, analysis of secondary bifurcations (what happens to limit cycles when delays are further increased?) and complete characterization of basins of attraction (are there risks of catastrophic extinction?) merit in-depth investigations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.Z., M.C. and H.K.; methodology, M.Z. and M.B.; software, S.T.; validation, M.C., S.T. and H.K.; formal analysis, M.Z. and M.B.; investigation, M.Z.; resources, H.K.; data curation, M.C.; writing—original draft preparation, M.Z.; writing—review and editing, M.Z., M.C., and S.T.; visualization, M.B.; supervision, H.K.; project administration, M.Z.; funding acquisition, M.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is part of the “Climate Resilience Across the Rural-Urban Continuum” (RurbanClimate) research project. The RurbanClimate project is funded by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark, Grant Agreement No. 20-11-KU and managed by Professor Jytte Agergaard, Department of Geosciences and Natural Resource Management, University of Copenhagen. More information about the project can be found at https://ign.ku.dk/english/rurbanclimate/, accessed on 12 March 2025.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DDE | Delay Differential Equation |

| MATLAB | Matrix Laboratory |

| RAM | Random Access Memory |

Appendix A. Regularity Properties of the Carrying Capacity Function

The carrying capacity function merits an in-depth analysis of its regularity properties, as these directly condition the existence and uniqueness of solutions established in Theorem 1.

Lipschitz Constant. For arbitrary , we seek to bound

The common denominator reveals that

The bound follows from observing that the denominator is bounded below by :

This proves that K is globally Lipschitz with constant .

Higher Regularity. The function K is actually infinitely differentiable on . Its first derivative is

This derivative is strictly positive, confirming strict growth. The second derivative, establishes that K is strictly concave on .

Asymptotic Behavior. We have

The parameter plays the role of a half-saturation constant: .

Appendix B. Lipschitz Constants for System Functions

Let us establish the Lipschitz constants for the two functions defining our dynamic system, used in the proof of Theorem 1.

Analysis of . Recall .

For two points and in a compact where and , decompose

For the quadratic term, use

Taking absolute values and using bounds,

Hence, the constants

Analysis of . For , we obtain by direct expansion

These bounds establish a locally Lipschitz character on every compact.

Appendix C. Detailed Proof of Positivity

This section completes the proof of Lemma 1 by detailing the case of resources.

Suppose there exists with for . Equation (3), evaluated when , becomes

By means of continuity on , the functions and are bounded. Let .

For sufficiently small , the dominant term is , which can be made arbitrarily larger than if . This gives , a contradiction.

Appendix D. Global Extension and Comparison Principle

This section details the proof of Theorem 2.

For the population, consider the auxiliary equation

This modified logistic equation admits the explicit solution (with ) which converges exponentially to when .

The comparison principle of Lakshmikantham and Leela [29] for delay equations establishes that if for all , then for all , hence

Analogous reasoning for resources establishes

Establishing strictly positive lower bounds uses the theory of uniform persistence developed by Butler and Waltman [30], guaranteeing and .

Appendix E. Calculation of Critical Value βc

This section details the calculation of condition (6) of Theorem 3.

From equilibrium equations, we derive

Substituting this into the resource equation,

Multiply by and rearrange

Analytical versus Numerical Determination: The question naturally arises whether the positive equilibrium can be found analytically. Due to the transcendental nature of the system involving the Michaelis–Menten carrying capacity function, closed-form solutions generally do not exist. However, in certain limiting cases, analytical approximations are possible.

Consider the limit , where the carrying capacity becomes approximately linear: . In this regime, the equilibrium system simplifies to

which yields the analytical approximation

For our baseline parameters, this approximation yields units, compared to the numerical value units, showing agreement within 5%. This approximation can serve as an initial guess for numerical methods.

More generally, perturbation methods could yield asymptotic expansions in powers of , though higher-order terms become algebraically complex. The advantage of numerical methods (Newton–Raphson or continuation algorithms) is their reliability across all parameter regimes without requiring small-parameter assumptions.

Returning to the general case, the quadratic equation in has

The discriminant is always positive. The physically acceptable root is

For , detailed analysis leads to

Appendix F. Complete Linearization and Jacobian Matrices

This section develops the calculations of linearization used in Theorem 4.

Set . The critical term expands

With , we obtain

The Jacobian matrices become

Appendix G. Spectral Analysis of Characteristic Equation

This section details the spectral analysis mentioned in Theorem 4.

The expanded characteristic equation is

In the symmetric case , set with . With , separate into real and imaginary parts:

Real part:

Imaginary part:

Appendix H. Verification of Transversality Condition

The transversality condition, essential for guaranteeing that a Hopf bifurcation actually occurs, is expressed as

By implicitly differentiating the characteristic equation with respect to , we obtain where represents the characteristic equation. Hence,

Calculating the denominator involves complex derivatives of the characteristic equation. The numerator contains

After evaluation at and , numerical calculation reveals the following:

Positivity confirms that eigenvalues actually cross the imaginary axis from left to right when increases, guaranteeing the occurrence of a Hopf bifurcation.

Appendix I. Calculation of Lyapunov Coefficient

The first Lyapunov coefficient, denoted as , plays a decisive role in characterizing the nature of a Hopf bifurcation. Its sign determines whether limit cycles emerge stably (supercritical bifurcation when ) or unstably (subcritical bifurcation when ), with fundamental implications for the predictability of asymptotic system behavior. Calculation of this coefficient, while conceptually clear, proves technically demanding and requires careful manipulation of mathematical objects living in infinite-dimensional functional spaces. We follow here the systematic methodology developed by Hassard, Kazarinoff, and Wan in their foundational 1981 work [31], adapting it to the specificities of our ecological system.

The starting point consists of determining generalized eigenvectors associated with the pair of purely imaginary eigenvalues that appear precisely at the bifurcation threshold. In the context of delay differential equations, these eigenvectors are not simple finite-dimensional vectors but rather functions defined on the historical interval . More precisely, the right eigenvector takes the form where parameters past time, and where satisfies a complex algebraic system derived from the eigenvalue equation. Resolution of this system, though technically delicate due to the presence of complex exponentials evaluated at delays, ultimately reduces to a two-dimensional linear algebra problem over the complex field. The left eigenvector q, adjoint in the sense of an appropriate inner product in the functional space , must satisfy a normalized orthogonality condition guaranteeing . This inner product, defined by an integral involving both instantaneous values and delayed contributions, reflects the particular functional structure of delay equations.

Once eigenvectors are determined, attention turns to extracting and characterizing system nonlinearities. In our model, the main source of nonlinearity comes from the term appearing in the population equation. Taylor expansion of this term up to a third order reveals cubic contributions of the form as well as mixed terms like , each weighted by numerical coefficients arising from successive partial derivatives. These nonlinear terms, though negligible in linear stability analysis, become crucial for determining behavior in the immediate neighborhood of bifurcation. They are mathematically encoded in a trilinear tensor denoted as , which associates three perturbation vectors with a resulting vector capturing the combined effect of cubic nonlinearities.

The Lyapunov coefficient finally emerges from a relatively compact integral formula, despite the complexity of the objects it manipulates. This formula is written as , where the bar denotes complex conjugation, and where the inner product integrates the action of the trilinear tensor on the eigenvector and its conjugate. The appearance of the factor reflects temporal normalization related to the period of nascent oscillations. Actual calculation of this expression, even with simplifications permitted by problem symmetries, remains sufficiently laborious to justify recourse to a computer algebra system. In our case, computer-assisted numerical evaluation revealed an approximate value of . This negativity, statistically significant despite its proximity to zero, confirms unambiguously that the Hopf bifurcation observed in our system is supercritical in nature.

The implications of this supercriticality merit emphasis as they condition system predictability in the post-bifurcation regime. Normal form theory guarantees that, in a neighborhood of the critical threshold, oscillation amplitude grows continuously according to the law when delay crosses the bifurcation threshold. This progressive growth, characteristic of supercritical bifurcations, contrasts sharply with the abrupt jumps and hysteresis phenomena that would mark a subcritical bifurcation. On the practical plane, this property reassures regarding the possibility of controlling the system: slight modifications of delays in the neighborhood of the critical threshold will only induce gradual and reversible changes in dynamics, rather than catastrophic tipping, which is difficult to anticipate and manage. Direct numerical observation of the square root law in Figure 1 remarkably corroborates this theoretical prediction arising from calculation of the Lyapunov coefficient.

Appendix J. Derivative of Composite Lyapunov Function

This section details the complete calculation of for the proof of Theorem 5.

Recall the components

Derivative of . The time derivative gives

Substitute in model equations and expand. For the first term,

Using equilibrium conditions and after regrouping,

For the second term, similar expansion gives

Derivative of . According to the Leibniz rule for integrals,

Combination and estimation. Combining and , delayed terms partially cancel each other out. Using Young’s inequality, to control cross products, and choosing judiciously, we establish where and are positive under the condition with C being a constant depending on system parameters. This establishes global stability.

References

- Ali, A.; Jawad, S. Stability analysis of the depletion of dissolved oxygen for the Phytoplankton-Zooplankton model in an aquatic environment. Iraqi J. Sci. 2024, 65, 2736–2748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malthus, T.R. An Essay on the Principle of Population; J. Johnson: London, UK, 1798. [Google Scholar]

- Vogels, M.; Zoeckler, R.; Stasiw, D.M.; Cerny, L.C.P.F. Verhulst’s Notice on the Law that Population Follows in its Growth. J. Biol. Phys. 1975, 3, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, G.E. Circular causal systems in ecology. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1948, 50, 221–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacDonald, N. Biological Delay Systems: Linear Stability Theory; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Gopalsamy, K. Stability and Oscillations in Delay Differential Equations of Population Dynamics; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Kuang, Y. Delay Differential Equations: With Applications in Population Dynamics; Academic Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Zeeshan, A.; Faranak, R.; Kamyar, H. A fractal–fractional-order modified Predator–Prey mathematical model with immigrations. Math. Comput. Simul. 2023, 207, 466–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damag, F.H.; Qurtam, A.A.; Ali, A.; Elsayed, A.; Adam, A.; Aldwoah, K.; Ali, S.O. Fractal–Fractional Coupled Systems with Constant and State- Dependent Delays: Existence Theory and Ecological Applications. Fractal Fract. 2025, 9, 652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, S. On nonlinear dynamics of predator-prey models with discrete delay. Math. Model. Nat. Phenom. 2006, 4, 140–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alyoubi, S.; Shah, N.A.; Nonlaopon, K.; El-Zahar, E.R. Efficient Computational Approaches for Fractional-Order Delay Differential Equations: Numerical Schemes and Stability Analysis. AIMS Math. 2024, 9, 35081–35105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Zahar, E.R.; Gaber, A.A.; Alyoubi, S.; Ebaid, A. Approximate Solutions for Delay Differential Equations Using Block Boundary Value Methods. J. Math. Comput. Sci. 2024, 34, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Zahar, E.R.; Ebaid, A. Analytical and Numerical Treatment of History Functions in Delay Differential Equations. J. Math. Comput. Sci. 2026, 41, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kar, T.K.; Matsuda, H. Global dynamics and controllability of a harvested prey-predator system with Holling type III functional response. Nonlinear Anal. Hybrid Syst. 2007, 1, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]