Abstract

Background: Rapidly growing mycobacteria (RGM) are microorganisms with variable pathogenicity, which can cause different clinical forms of mycobacterioses. They can form structured communities at the liquid-air interface and adhere to animate and inanimate solid surfaces, characterizing one of their most powerful mechanisms of resistance and survival, named biofilms. Objectives: Here, a novel series of sulfamethoxazole (SMTZ) Schiff bases were obtained by the condensation of the primary amine from SMTZ core with six different aldehydes to evaluate their antimicrobial and antibiofilm activities, as well as physicochemical and in silico characteristics. Methods: The compounds L1–L6 included: pyridoxal hydrochloride (L1), salicylaldehyde (L2), 3-methoxysalicylaldehyde (L3), 2-hydroxy-1-naphthaldehyde (L4), 3-allylsalicylaldehyde (L5), and 4-(diethylamino)salicylaldehyde (L6). MIC determination was performed against standard strains and seven clinical isolates. Time-kill assays, biofilm inhibition assays, atomic force microscopy, and peripheral blood mononuclear cell cytotoxicity assays were carried out. Density functional theory (DFT) calculations using quantum descriptors, Mulliken charges, Fukui functions, non-covalent interactions (NCI), and reduced density gradient (RDG), along with molecular docking calculations to DHS, LasR, and PqsR, supported the experimental trend. Results: The compounds L1–L6 showed a significant capacity to inhibit the growth of RGM, with MIC values in the range of 0.61 to 1.22 μg mL−1, which are significantly lower than those observed for the parent compound SMTZ, demonstrating superior antimicrobial potency. To deepen antimicrobial activity assays, L1 was chosen for further evaluations and showed a significant ability to inhibit the growth of RGM in both planktonic and biofilm forms. In addition, atomic force microscopy views great changes in topography, electrical force, and nanomechanical properties of microorganisms. The cytotoxic assays with the peripheral blood mononuclear cell model suggest that the new compound may be considered as an antimicrobial alternative, as well as a safe substance showing selectivity indexes in the range of efficacy. Conclusions: Density functional theory (DFT) calculations were performed to obtain quantum descriptors, Mulliken charges, Fukui functions, non-covalent interactions (NCI), and reduced density gradient (RDG), which, with molecular docking calculations to DHS, LasR, and PqsR, supported the experimental trend.

1. Introduction

Rapidly growing mycobacteria (RGM) compose a subgroup of non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) that are responsible for many infections reported worldwide [1]. These microorganisms are ubiquitous and have variable pathogenicity, causing different clinical forms of mycobacteriosis, especially in immunocompromised patients [2]. The high rates of morbidity and mortality associated with infections caused by RGM species are aggravated by imprecise identification of the etiologic agent of mycobacteriosis, leading to difficulties in the implementation of adequate drug therapy [3].

The RGM species, such as M. fortuitum, M. massiliense, and M. abscessus can form structured communities at the liquid-air interface and adhere to solid surfaces, characterizing one of their most powerful mechanisms of resistance called biofilms [4,5]. Biofilms are considered important sources of infection due to their increased antimicrobial resistance and their ability to adhere to both natural and synthetic surfaces [5]. Also, biofilm development capacity is related to virulence profile, pathogenicity, resistance to antimicrobial agents, and environmental survival [4].

Notwithstanding their intrinsic complexity and the increase in the number of cases of microbial resistance, few antimicrobial drugs are approved. According to data from the Food and Drug Administration of the United States of America (FDA-USA), between 2003 and 2012, there were only seven new antimicrobials made available [6]. This scarcity threatens the treatment of common infectious diseases, such as pneumonia and tuberculosis, making the post-antibiotic era, where banal infections can cause death, even closer [7]. In this regard, it has been observed that an increasing emphasis in terms of screening new and more effective antimicrobial drugs, making this an interesting and important field in medicinal chemistry.

Among the promising scaffolds, Schiff bases have attracted increasing attention due to their unique structural and chemical properties, particularly the imine functional group (C=N), which enables reactivity, structural versatility, and metal coordination, all of which are advantageous in the context of drug discovery [8,9,10]. Beyond their structural relevance, Schiff bases have demonstrated diverse biological activities, including antioxidant [11], antidiabetic [12], and urease inhibitory effects [13]. These findings underscore the broad pharmacological potential of this class of compounds and highlight their relevance as molecular scaffolds for the design of bioactive agents. Furthermore, modern computational approaches, such as density functional theory (DFT), molecular docking, molecular dynamics simulations, and non-covalent interaction analyses, have been successfully employed to elucidate structure–activity relationships, electronic descriptors, and binding modalities of Schiff bases, providing deeper insights into their reactivity and mechanism of action.

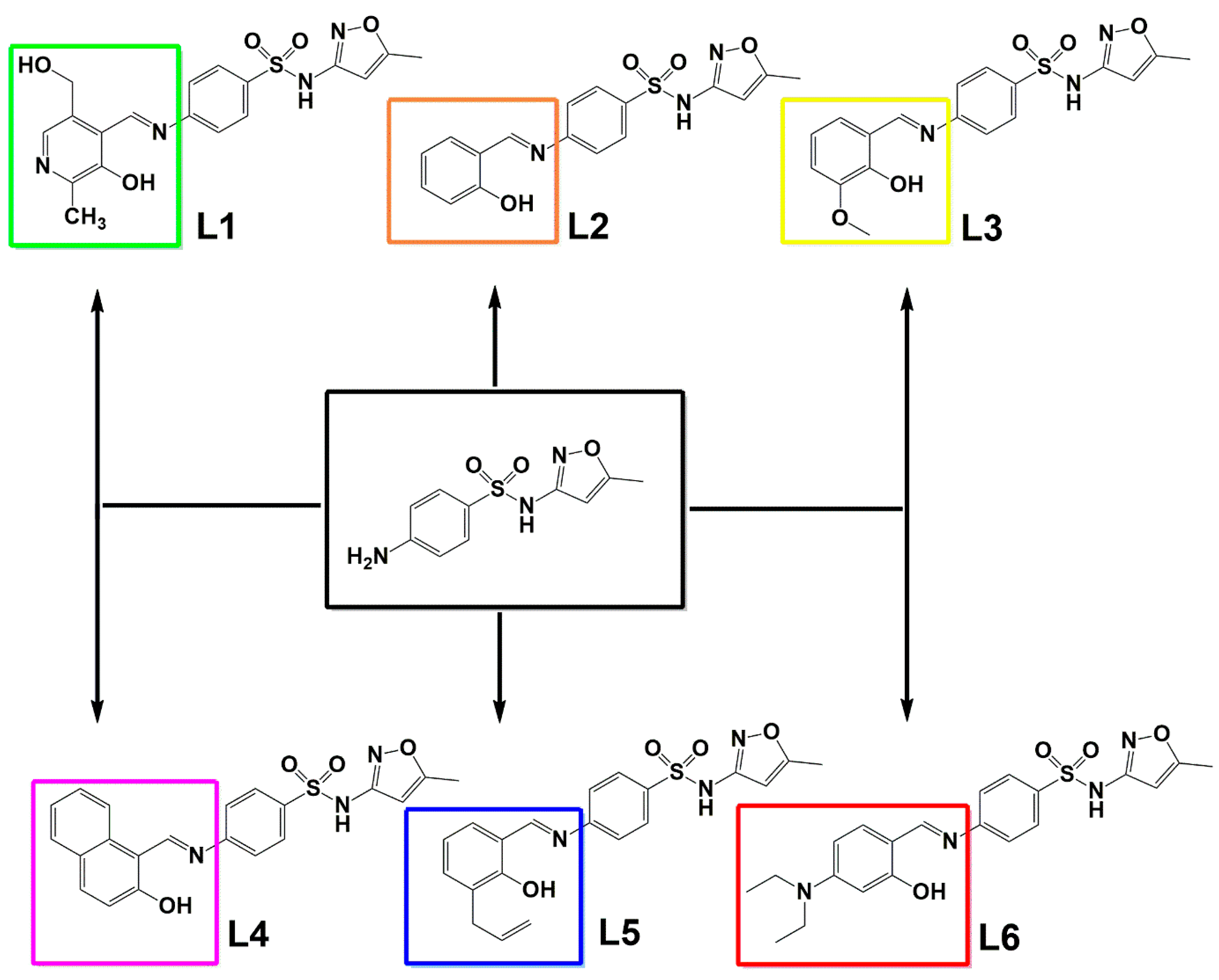

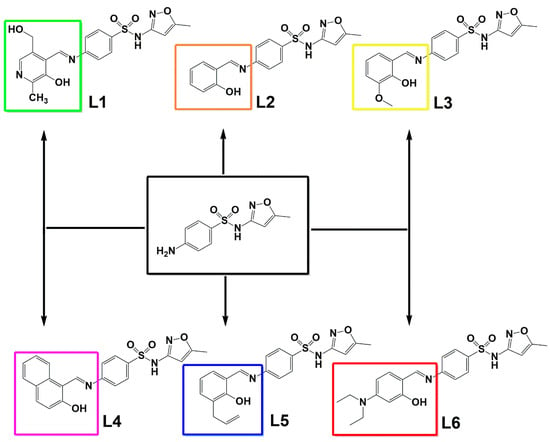

Due to the lack of efficient treatments for RGM infections this paper addresses the synthesis and characterization of Schiff bases derivatives from sulfamethoxazole (SMTZ, Scheme 1), condensed with six different aldehydes (Scheme 1): pyridoxal (L1) (form of vitamin B6), salicylaldehyde (L2), o-vanillin (L3), 2-hydroxy-1-naphthaldehyde (L4), 3-allylsalicylaldehyde (L5), and 4-(diethylamino)salicylaldehyde (L6). All compounds developed here were found to have promising activity in inhibiting the planktonic growth of different standard strains of mycobacteria and seven clinical isolates from patients diagnosed with mycobacteriosis admitted to a hospital in southern Brazil. The SMTZ condensed with L1 was chosen for further evaluations due to the very low minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values obtained, which were lower when compared to the values determined for the other molecules tested, including SMTZ. Moreover, the safety in vitro profile of this compound was also evaluated using a peripheral blood mononuclear cell model (PBMC). Furthermore, the electronic properties of the new SMTZ Schiff bases were studied employing DFT which offered information regarding the quantum descriptors, i.e., highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO), energy gap (Eg), chemical potential (µ), hardness (η), and electrophilicity index (ω), which are intrinsically correlated with the molecular reactivity in biological systems [14,15,16,17,18]. Additionally, the Fukui functions, Mulliken charges, and non-covalent interactions (NCI) [19,20] were also evaluated with molecular docking calculations. To the best of our knowledge, there are no previous reports in the literature describing Schiff bases specifically derived from SMTZ that have been evaluated against RGM. Thus, the present data are pioneering in proposing the synthesis and characterization of SMTZ derivatives (L1–L6) with antimicrobial and antibiofilm activity against both reference strains and clinical isolates of RGM.

Scheme 1.

The chemical structure of the condensation products L1–L6, considering SMTZ (in black square) as the structural core.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Synthesis and Characterization

All synthetic reactions were conducted in open atmosphere systems. Commercial reagents and solvents are used as received without further purification. The compounds L1–L6 were synthesized using a 25 mL round-bottom flask with a magnetic stirring bar. Around 1 mmol of SMTZ (0.253 g) was solubilized in 15 mL of methanol, then, 1 mmol of the respective aldehydes were added: L1 (pyridoxal hydrochloride, 0.203 g), L2 (2-hydroxybenzaldehyde, 0.122 g), L3 (2-hydroxy-3-methoxybenzaldehyde, 0.152 g), L4 (3-hydroxy-2-naphthoic acid, 0.188 g), L5 (3-allylsalicylaldehyde, 0.162 g) and L6 ((diethylamino)salicylaldehyde, 0.193 g). The reaction was carried out at 65 °C for 3 h, leading to the formation of a precipitate. The precipitate was filtered and washed twice with cold methanol for ligands L2, L3, L4, and L6. Ligand L1, which appeared as a yellow oil, was columnarized with a 7:3 chloroform/methanol eluent. For ligand L5, the precipitate formed was dissolved in chloroform, and a flash column was used to purify the synthesized product.

The structural characterization was conducted with nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra recorded on a Bruker DPX-600 spectrometer (Bruker Corporation, Billerica, MA, USA) at 600 MHz (1H) and 151 MHz (13C) (spectroscopic data provided as Supplementary Materials). Deuterated dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO-d6) was used as the solvent (tetramethyl silane (TMS) was used as the internal reference), and deuterated chloroform CDCl3-d. The chemical shifts are expressed in δ (ppm) and the coupling constants (J) in Hz. The 1H- and 13C-NMR and FTIR spectra were provided as Figures S1–S20 in the Supplementary Materials. The synthesized product crystals (L2, L3, L4, and L6) were properly purified and diluted in DMSO-d6 at a ratio of approximately 10 mg to 0.7 mL of solvent. There was no need to increase the temperature of the total dilution, resulting in a completely translucent solution without precipitation. For ligand L1, prior dissolution of the brown oil with deuterated solvent was necessary for subsequent analysis in the experimental tubes. For ligand L5, deuterated chloroform was used, also forming a translucent solution without precipitate formation. The 1H NMR spectra showed characteristic signals for the imine hydrogens, which were identified as a singlet. The 13C NMR spectra showed characteristic signals for the C=N carbons around 160 ppm. FIA-ESI-MS Analysis. Samples were diluted in methanol with DMSO (5%) and injected by flow injection analysis (FIA) into an LC-MS Q-TOF (model 9050, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) controlled by UPLC Shimadzu Nexera Series. For FIA, an aliquot (1.0 μL) of the sample solution was injected into a mobile phase consisting of methanol acidified with formic acid (0.1%) at a flow rate of 0.8 mL/min and delivered directly to the TOF-MS system (no column was used). The mass spectrometer was operated in the negative and positive ion mode under the following conditions: interface voltage 4.0 kV for the positive ion mode and −3.0 kV for the negative ion mode, nebulizing gas flow 2.0 L/min, drying gas flow 10.0 L/min, heating gas flow 10.0 L/min, interface temperature 300 °C, desolvation temperature 526 °C, and scanned range of m/z 50–2000 for MS (Figures S21–S26 in the Supplementary Materials). For data acquisition and qualitative analysis, the LabSolution software and therein occurring tools were used.

- L1: Yield: 88%. M.P.: 209 °C (decomposition). Elem. Anal. for C18H18N4O5S (M.M. = 402.42 g/mol−1), Calc. (%): C, 53.72; H, 4.51; N, 13.92. Found (%): C, 53.70; H, 4.49; N, 13.92 FT-IR (ATR, cm−1): 3452 [ν(O–H) phenol], 2836 [ν(O–H) alcohol], 1541 [s, ν(C=N) imine], 1512 [ν(N-H)amine]. HRMS calcd for C18H18N4O5S—ESI-TOF, [M+H]+ 403.1031, found 403.1035.

- L2: Yield: 88%. M.P.: 221 °C (decomposition). Elem. Anal. for C17H15N3O4S (M.M. = 357.83 g/mol−1), Calc. (%): C, 57.13; H, 4.23; N, 11.76. Found (%): C, 57.17; H, 4.22; N, 11.77. FT-IR (ATR, cm−1): 2859 [ν(O–H) phenol], 1589 [s, ν(C=N) imine], 1520 [ ν(N-H) amine]. HRMS calcd for C17H15N3O4S—ESI-TOF, [M+H]+ 358.0817, found 356.0861.

- L3: Yield: 86%. M.P.: 187 °C (decomposition). Elem. Anal. for C18H17N3O5S (M.M. = 387.40 g/mol−1), Calc. (%): C, 55.80; H, 4.42; N, 10.85. Found (%): C, 55.79; H, 4.44; N, 10.86. FT-IR (ATR, cm−1): 3108 [ν(O–H) phenol], 1541 [s, ν(C=N) imine], 1577 [ ν(N-H)amine]. HRMS calcd for C18H17N3O5S—ESI-TOF, [M+H]+ 388.0922, found 398.0968.

- L4: Yield: 91%. M.P.: 194 °C (decomposition). Elem. Anal. for C21H17N3O4S (M.M. = 407.44 g/mol−1), Calc. (%): C, 61.90; H, 4.21; N, 10.31. Found (%): C, 61.88; H, 4.19; N, 10.30. FT-IR (ATR, cm−1): 3353 [ν(O–H) phenol], 2878 [ν(O–H) alcohol], 1583 [s, ν(C=N) imine], 1516 [ν(N-H)amine]. HRMS calcd for C21H17N3O4S—ESI-TOF, [M+H]+ 408.0973, found 408.1021.

- L5: Yield: 91%. M.P.: 201 °C (decomposition). Elem. Anal. for C20H19N3O4S (M.M. = 397.44 g/mol−1), Calc. (%): C, 60.44; H, 4.82; N, 10.57. Found (%): C, 60.42; H, 4.80; N, 10.55. FT-IR (ATR, cm−1): 3406 [ν(O–H) phenol], 1600 [s, ν(C=N) imine], 1557 [ν(N-H)amine]. HRMS calcd for C20H19N3O4S—ESI-TOF, [M+H]+ 398.1130, found 398.1176.

- L6: Yield: 88%. M.P.: 197 °C (decomposition). Elem. Anal. for C21H24N4O4S (M.M. = 428.50 g/mol−1), Calc. (%): C, 58.86; H, 4.65; N, 13.07. Found (%): C, 58.90; H, 4.66; N, 13.09. FT-IR (ATR, cm−1): 3187 [ν(O–H) phenol], 1618 [s, ν(C=N) imine], 1554 [ν(N-H)amine], 1311 [ν(C-H) methyl], 845 [ν(N-C) methyl]. HRMS calcd for C21H24N4O4S—ESI-TOF, [M+H]+ 429.1552, found 429.1510.

2.2. X-Ray Crystallography

Data were collected on a Bruker D8 Venture diffractometer (Bruker Corporation, Billerica, MA, USA) equipped with an Incoatec IµS high brilliance Mo-Kα X-ray tube with two-dimensional Montel micro-focusing optics and a Photon 100 detector. Measurements were made at low (100 K) temperature using a Cryostream 800 unit from Oxford Cryosystems (Hanborough Business Park, Long Hanborough, UK). The structure was solved by direct methods using SHELXS [21]. Fourier-difference map analyses yielded the positions of the non-hydrogen atoms. Refinements were carried out with the SHELXL package [22]. All refinements were made by full-matrix least-squares on F2 with anisotropic displacement parameters for all non-hydrogen atoms. Hydrogen atoms were included in the refinement in calculated positions according to the molecular skeletons. Drawings were done using the software Mercury 4.1.0 and ORTEP.31 [23,24] (Figures S27–S31 in the Supplementary Materials). Crystal data and more details of the data collection and refinements of molecules L2–L6 are contained in Tables S1–S4 in the Supplementary Materials.

2.3. Microorganism Strains and Clinical Isolates

The standard strains M. abscessus (ATCC 19977), M. fortuitum (ATCC 6841), M. smegmatis (ATCC 700084), and M. massiliense (ATCC 48898) were used in this work. In addition, for the accomplishment of this study, we used seven clinical isolates of patients hospitalized at the University Hospital of Santa Maria (HUSM, RS, Brazil) obtained from the Clinical Analysis Laboratory in 2020, characterized as acid-alcohol resistant bacillus (AARB positive) and that have grown in Löwenstein-Jensen (LJ) medium Löwenstein-Jensen (LJ) medium (HiMedia Laboratories Pvt. Ltd., Mumbai, India). The phenotypical identification of clinical isolates is summarized in Table S5 in Supplementary Materials. The microorganisms were kept at −80 °C and grown on Löwenstein-Jensen agar. This work was conducted with an experimental protocol approved by the UFSM ethics committee for research with clinical isolates, CAAE number: 71795417.6.0000.5346, approved on 28 August 2017.

2.4. Susceptibility Tests

The susceptibility tests were performed by the broth microdilution (Mueller-Hinton broth (HiMedia Laboratories Pvt. Ltd., Mumbai, India) method according to the standard protocol established by Clinical & Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI), document M24-A2 [25]. The inoculum density for this susceptibility test was 5.0 × 105 CFU mL−1. The antimicrobial agents were evaluated at the following concentrations: amikacin (Fluka, Saint Louis, MO, USA) 1.0–128 µg mL−1, ciprofloxacin (Fluka, Saint Louis, MO, USA) 0.125–16 µg mL−1, clarithromycin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) 0.06–64 µg mL−1, doxycycline (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) 0.25–32 µg mL−1, imipenem (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) 1–64 µg mL−1, and SMTZ (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) 1.0–128 µg mL−1. The new compounds (L1–L6) were evaluated at concentrations of 0.150 to 1250 µg mL−1. After 72 h of incubation at 30 °C, treatment plates were read, and the minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) were determined using 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride (VetecR, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil) as microbial growth indicator [26]. After obtaining the results, to deepen the antimycobacterial and antibiofilm activity tests, the compound with the lowest minimum inhibitory concentration was selected to carry out the other tests. The breakpoints for interpreting the susceptibility of microorganisms to antimicrobial agents can be seen in Table S6 in the Supplementary Materials.

2.5. Time-Kill Assays

The death curve assays were performed using RGM strains [27,28]. The compound with the lowest MIC value was selected to carry out the test. From the values determined in the susceptibility test, MIC and ½ MIC aliquots were used for plating on Mueller-Hinton agar (BD®, Le Pont de Claix, France) after 0, 24, 48, and 72 h of exposure to the compound. The inoculated medium without drug was plated as a growth control. Based on the CFU, the inhibitory effect of the compounds was calculated. Bactericidal activity was defined as the count of the number of viable colonies treated with the compounds compared with the untreated control at a specific time point. The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 72 h, and the procedure was repeated three times.

2.6. Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) Measurements

The effect and interaction of the new Schiff Base (L1) derived from SMTZ and pyridoxal on mycobacteria were investigated by AFM, using M. smegmatis (ATCC 700084). The M. smegmatis is widely used as a model mycobacterium representative of pathogenic species of the same group, precisely because it is non-pathogenic, which minimizes the risk of contamination of the researcher and the equipment. In addition, it exhibits metabolic behavior and morphology similar to those of other non-tuberculous mycobacteria.

Topography and adhesion maps were acquired simultaneously using the PinPoint Nanomechanical mode and a high-frequency rotated monolithic silicon probe (TAP300-G Budget Sensors, NanoAndMore USA Inc., Watsonville, CA, USA) with a nominal resonance frequency of 300 kHz and 40 N m−1 force constant on a Park NX10 microscope (Park Systems, Suwon, Korea). Electric force mode was performed using the standard non-contact AFM setup with a gold-coated n-type silicon probe (NSC14 Cr/Au Mikromasch, Innovative Solutions Bulgaria Ltd., Sofia, Bulgaria), nominal resonance frequency of 160 kHz, and 5.0 N m−1 force constant. All measurements were carried out under ambient conditions at room temperature (21 ± 5 °C) and relative humidity (55 ± 10%). Images were treated offline using XEI software version 4.3.4 Build22 RTM1.

2.7. Biofilm Formation Inhibition Test

The standard strains M. abcessus, M. fortuitum, and M. massiliense, and biofilm-forming clinical isolates were used to evaluate the capacity of the selected compound to inhibit biofilm formation. The compound with the lowest MIC value in the susceptibility tests was selected to carry out the test. The biofilm formation and quantification were determined [29]. In polystyrene test tubes, 1.0 mL of Middlebrook 7H9 (MD7H9) medium (BD®, Le Pont de Claix, France) containing 1.0 × 107 CFU mL−1 of the clinical isolates culture was added. So, 1.0 mL of treatment per tube was added for each compound concentration. The concentrations used were equal to or lower than the MIC value. The tubes were topped with parafilm® and incubated at 30 °C for 7 days. After this period, the biofilm quantification was performed using 0.1% crystal violet. The absorbance was measured in a spectrophotometer with optical density (OD) at 570 nm (Spectrophotometer U-1800, Mettler Toledo, Barueri, São Paulo, Brazil). The mycobacterial biofilm inhibition induced by SMTZ was also determined for comparison, and the tests were performed in triplicate. The microorganism biofilm formation inhibition caused by the compound was determined by the significant difference between the means of the obtained absorbance for the positive control (culture medium and bacterium) and the mean obtained for the negative control (culture medium).

2.8. Computational Procedure

2.8.1. Density Functional Theory (DFT) Calculations

All DFT simulations were conducted using Gaussian 09W [30], including the natural bond orbital (NBO) software package [31]. For this reason, the B3LYP functional and the 6-311++G(d,p) basis set from Gaussian 09W were used. The self-consistent reaction field (SCRF) model was employed to account for solvent effects, using methanol as the solvent. The geometries of L2–L6 were obtained through X-ray recrystallization in methanol. The X-ray coordinates were then used together with the implicit solvent model (considering methanol as the solvent) to calculate the single-point energy and to obtain data on the energies of the HOMO and LUMO orbitals. In contrast, pyridoxal was not crystallized; instead, its geometry was optimized at the B3LYP/6-311++G(d,p) level of theory using methanol as the implicit solvent model, Polarizable Continuum Model (PCM), and verified as minima, with no imaginary frequencies detected. A combination of the software Multiwfn version 3.8, VMD version 1.9.2 [32,33], Gnuplot version 6.0, IrfanView version 4.72, UCA-FUKUI version 2.0 [34], GaussView version 5.0, and Chemcraft version 1.8 [35] was employed together with Gaussian 09W (revision A.02) and NBO for generating the molecular orbitals, density distribution, and energy levels, Fukui functions, non-covalent interactions (NCI) isosurfaces, and reduced density gradient (RDG) graphics.

2.8.2. Fukui Functions Estimation

The Fukui functions f(r), rooted in Conceptual Density Functional Theory, were calculated according to the reports in the literature [36,37]. The following descriptors are important to identify reactive regions in a molecule: nucleophilic (f+, identifies regions able to perform nucleophilic attack), electrophilic (f−, highlights areas susceptible to electrophilic interactions), neutral (f0, represents the overall molecular reactivity under neutral conditions), and dual-descriptor (f2, offers insights into sites exhibiting both nucleophilic and electrophilic behavior). These descriptors were obtained using the Finite Difference Approximation (FDA), which provides a detailed view of localized reactivity across the molecular structure.

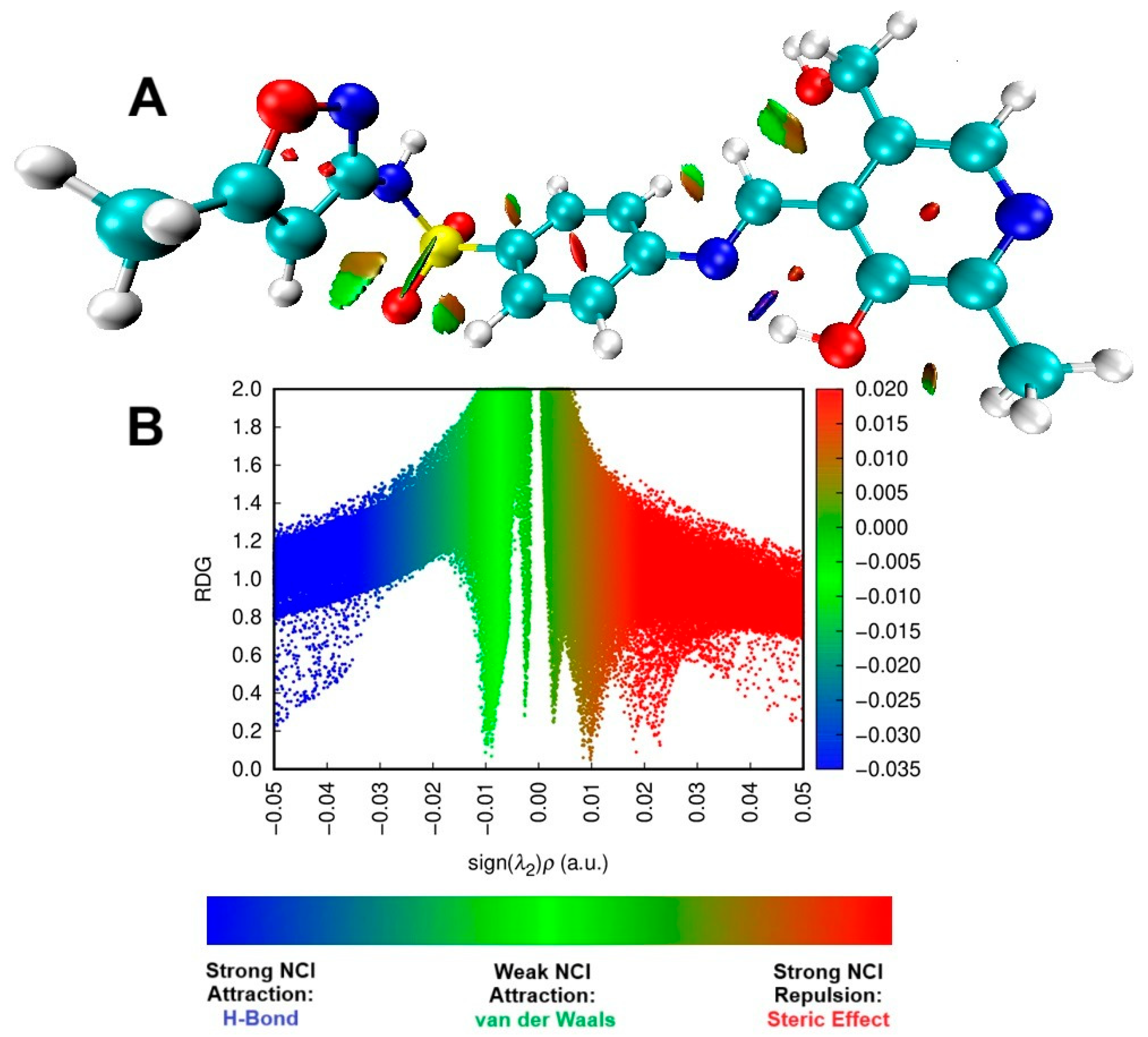

2.8.3. Non-Covalent Interactions (NCI) and Reduced Density Gradient (RDG) Analysis

The NCI was introduced by Johnson et al. [38] and has positively impacted computational chemistry, referring to the diverse types of forces that occur between molecules or within different parts of a single molecule. Although weaker than covalent bonds, NCI play a crucial role in both chemical and biological systems and are fundamental to many biological processes, particularly in the binding of large biomolecules, where precise and reversible interactions are essential for structure and function. Reduced Density Gradient (RDG) [39] is another recent computational chemistry technique, and it is a method that explores NCI within real space by examining electron density and its gradients. RDG differentiates the types of interactions such as hydrogen bonding, van der Waals forces, and steric repulsion of a molecular system, and for this use Equation (1) where ρ(r) is the electron density at a point, and ∣∇ρ(r)∣ is the magnitude of the gradient of the electron density at that point.

2.8.4. Molecular Docking Procedure

The Protein Data Bank (PDB) was used to obtain the crystallographic structures of the target dihydropteroate synthetase (DHS), transcriptional regulator LasR, and LysR-type transcriptional regulator PqsR (PDB codes 1TX2, 3IX3, and 4JVI, respectively) [40,41]. The chemical structure for L2–L6 was obtained from the X-ray data, while L1 was built and optimized following Section 2.8.1. The GOLD 2023 software (Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center Software Ltd., Cambridge, UK) was used for molecular docking calculations, considering the standard function ChemPLP due to the best root mean square deviation (RMSD) values previously reported [42] for the previously studied proteins. The web server Protein-Ligand Interaction Profiler (PLIP) [43] was used for the treatment of the best docking pose, while the 3D-figures were generated by PyMOL Molecular Graphics System 1.0 level software (Delano Scientific LLC software, Schrödinger, New York, NY, USA).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Synthesis and Structural Analysis of L1–L6

The SMTZ derivatives L1–L6 were obtained by the condensation of SMTZ and the respective aldehydes: pyridoxal hydrochloride (L1), salicylaldehyde (L2), o-vanillin (L3), 2-hydroxy-1-naphthaldehyde (L4), 3-allylsalicylaldehyde (L5), and 4-(diethylamino)salicylaldehyde (L6) in methanol for 180 min. All reactions showed the formation of precipitates, except the reaction involving pyridoxal, in which a dense yellow/brown oil was obtained.

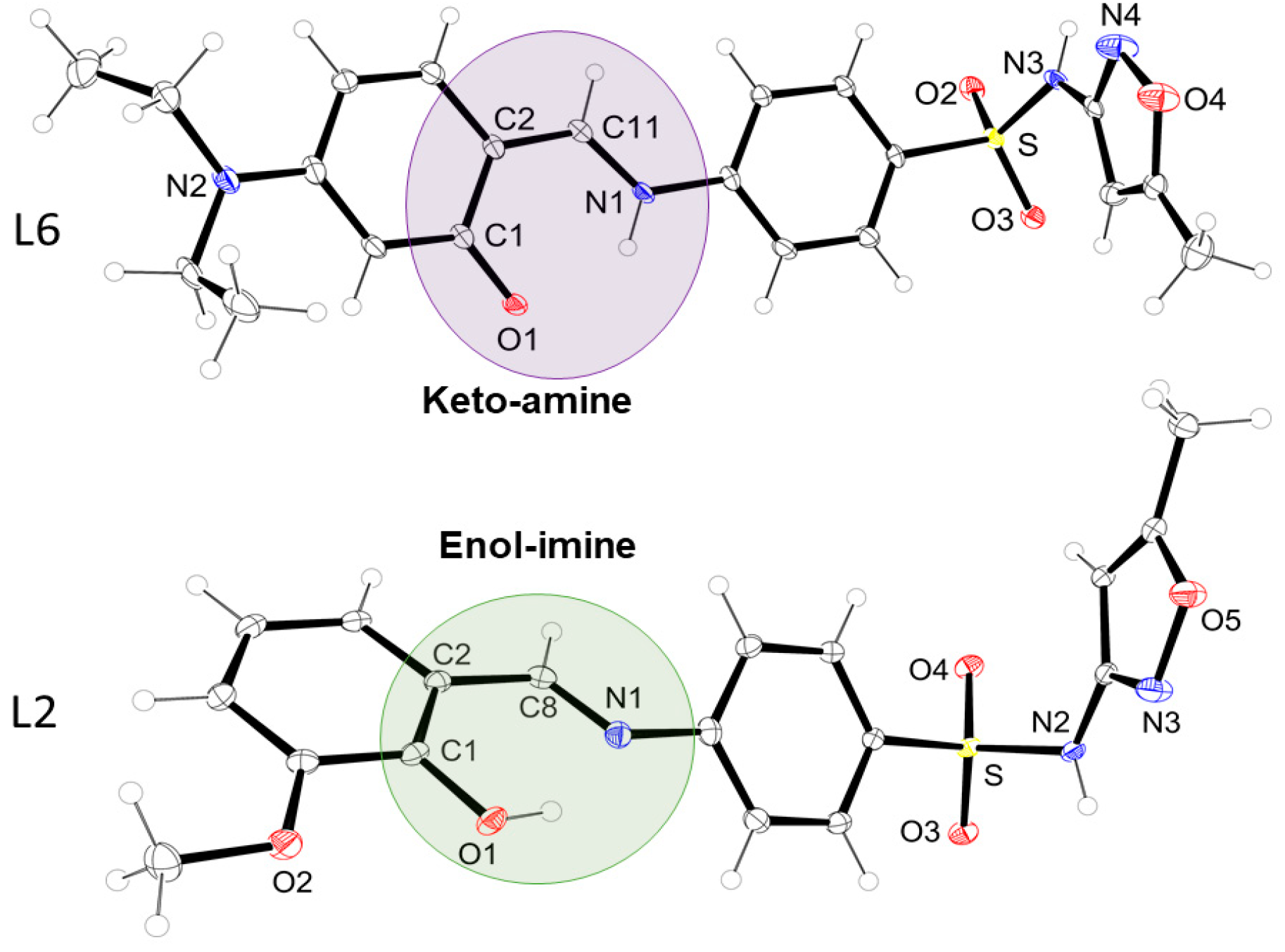

The preliminary structural characterization was performed using 1H- and 13C-NMR, FTIR, and FIA-ESI-MS analysis, which are provided in Figures S1–S26 of the Supplementary Materials. After recrystallization of the precipitates in a 70%/30% methanol/ethanol, crystals suitable for single crystal X-ray diffraction were obtained (Tables S1–S4 of measurement and crystallographic data can be evaluated in the Supplementary Materials). Two distinct behaviors were evidenced, i.e., compounds L2, L3, and L5 had the classic cut of strong phenol-imine hydrogen bond formation, being classified as enol-imine, and compounds L4 and L6 fit into the keto-amine equilibrium, according to Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Highlighting the keto-enol equilibria of compounds L2 (below) and L6 (above).

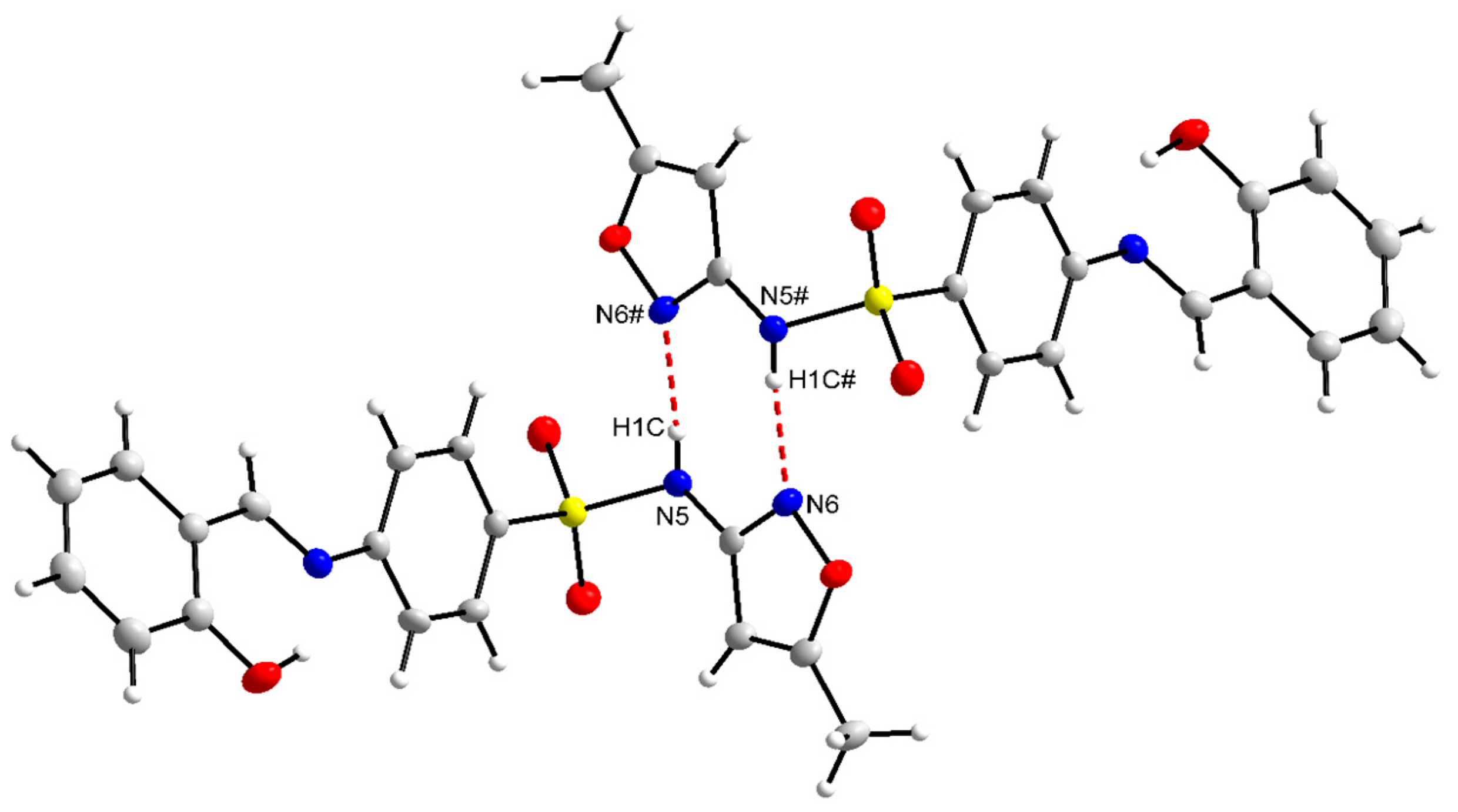

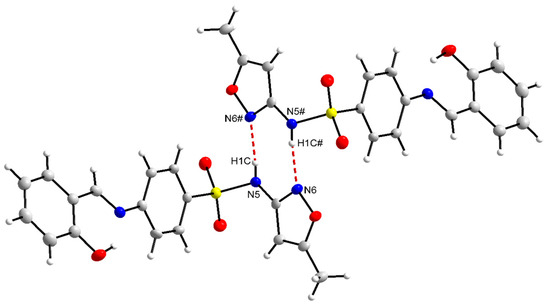

Since compounds L2, L3, and L5 crystallized in the enol-imine form, there is a strong hydrogen bond, O(phenol)-H···N(imine), with the bond order from 1.776(33) to 1.886(16) Å. On the other hand, compounds L4 and L6 showed a tendency to crystallize in the keto-imine form, and in these cases, the hydrogen bond occurs by the donor N(amine)-H···O(phenolate) (1.903(2) to 1.951(1)Å). The main bond distances are shown in Tables S3 and S4 in the Supplementary Materials. Additionally, for L2 and L5, in the solid state, the formation of hydrogen bonds in a centrosymmetric dimer system was detected, as exemplified in Figure 2 for L2.

Figure 2.

The centrosymmetric dimers for the compound L2.

The interactions observed for L2 and L5 highlight the source bonds of centrosymmetric dimers [44,45] involving donor and acceptor atoms from different molecules, thus producing a three-dimensional network [46,47]. In this case, there is a donor and acceptor element in the same molecule and their respective complements in the other molecule, in the case of the hydrogen of the amine, the nitrogen of the 5-methylisoxazole ring, being a classic representation of hydrogen bonds [48,49]. However, when the donor is a carbon of the main sp, sp2, or sp3 hybridizations and the acceptor is an electronegative element, these hydrogen bonds are indicated as non-classical [50,51].

In the case of classical immunity bonds, the determining factor for the bond to occur is the electronegativity of the elements bonded to the hydrogen in the D–H species and the polarizability of the acceptor atoms, where the hydrogen acceptor (A) must have high electron density. In addition to electronegativity and polarization, hydrogen bond distances and angles can be conventionally expressed in terms of their distances. These bonds are defined as long distances between H···A, while short distances occur between donor and acceptor elements, and therefore, temporary bonds are moderate or strong. Strong or short bonds, which represent the examples of molecules synthesized in this work, represent an electrostatic model that can be represented by D···H···A, where the interaction distance D···A becomes short and the hydrogen atom tends to be located equidistant from A and B [49,52,53,54,55].

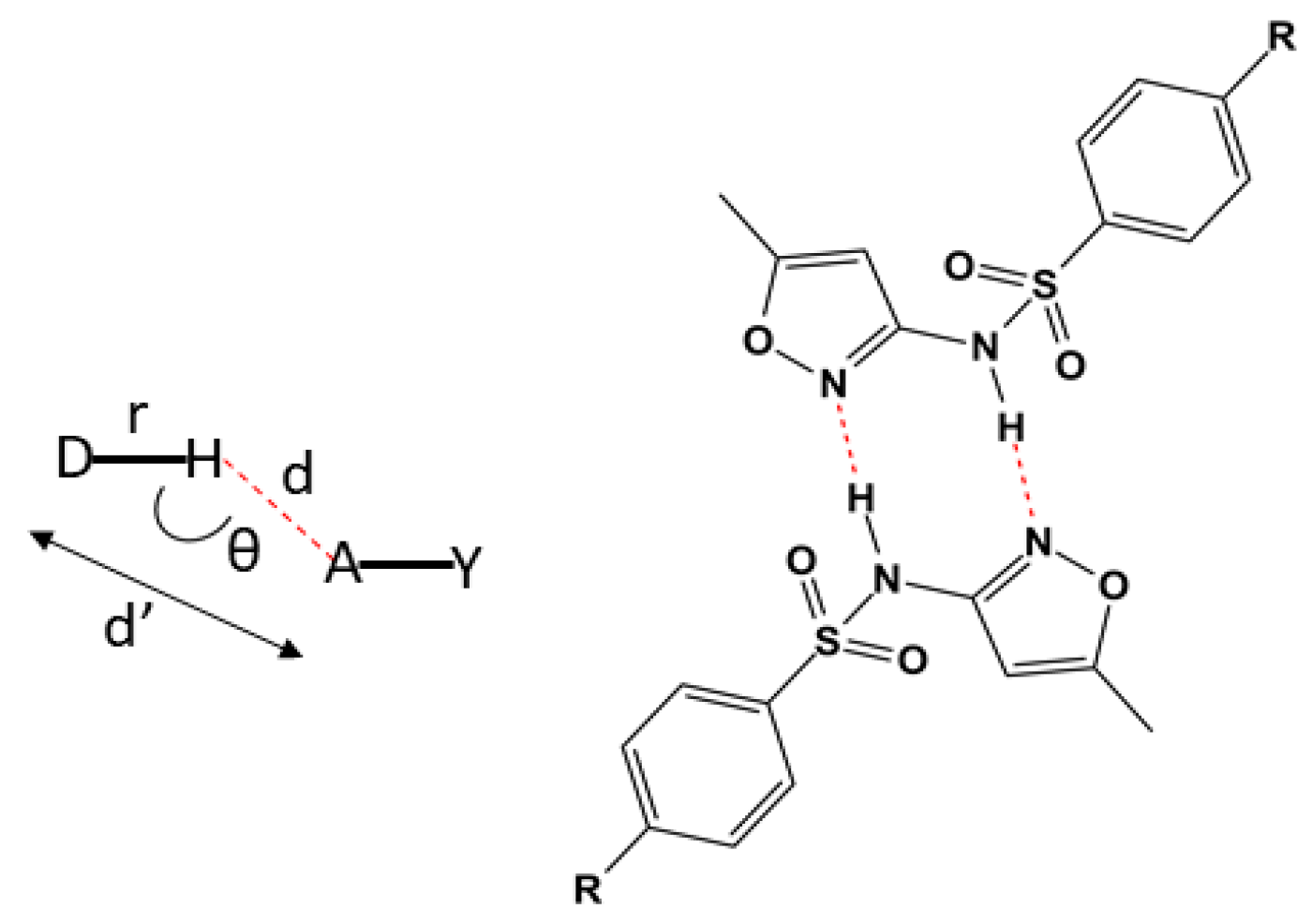

The most common distances for strong electrostatic bonds show the distances (d’) D····R presenting variations in the range of 2.2 to 2.5 Å [44,45,46,47,48] (Figure 3). However, there is a scientific consensus that the closer to 180°, the more intense the bond will be [44,46,49].

Figure 3.

On the left, the representation of the distances and bond angles in classical hydrogen bonds. On the right, a representation of part of the chemical structure from L2 with the hydrogen bonds in red forming the centrosymmetric dimer. The substituent R refers to the condensation products of the salicylaldehyde and 4-(diethylamino)salicylaldehyde.

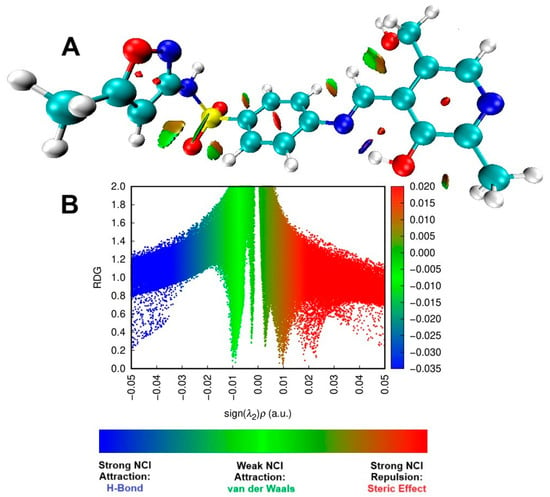

3.2. Microbiological Assays

The Schiff base compounds have been reported with high spectrum biological activity, for example, antibacterial, antifungal, anti-inflammatory, anticonvulsant, and antitumor [56,57]. Additionally, there are important advantages to working with Schiff base compounds, including the possibility to form stable complexes with transition metals [58,59] and a relatively easy synthetic pathway with the possibility of chemical modifications to adjust steric and electronic factors or induce chirality [60,61], e.g., the azometinic nitrogen presents sp2 hybridization, being typically recognized as a Lewis base of an intermediate nature to be covalently associated with other molecules [62,63,64]. In this sense, through the chemical derivation of the classic antimicrobial SMTZ (Section 3.1), the obtained derivatives L1–L6 were assayed against some clinically relevant RGMs. However, to understand the susceptibility profile of RGM to SMTZ and other clinically relevant antimicrobial agents, initially, some clinical isolate RGM (CI-I-VII) were used, considering the gold standard technique indicated by the CLSI [25] (Table 1).

Table 1.

In vivo susceptibility of clinical isolates of RGM to different antimicrobial agents.

The results summarized in Table 2 indicated that the clinical isolates RGM presented a higher resistance index to SMTZ (four resistant isolates), followed by clarithromycin (two resistant isolates and three isolates with intermediate resistance), ciprofloxacin (two isolates with resistance), doxycycline (one isolate with resistance and one isolate with intermediate resistance), amikacin and imipenem (with one clinical isolate with intermediate resistance each). Thus, none of the tested clinical isolate samples were sensitive to all antimicrobials under study, presenting at least one intermediate response, for example, the macrolide clarithromycin, which appears as a first-line drug for the treatment of mycobacterioses [3,29] only two clinical isolates RGM could be classified as drug-sensitive to this antimicrobial, with a MIC value of 2.0 μg mL−1 or less. In addition, the clinical isolate CI-VII was resistant to clarithromycin, doxycycline, and SMTZ, being considered a multidrug-resistant [65]. Overall, the evaluated RGM presented resistance to some of the main broad-spectrum antimicrobials that are often used to treat infections caused by these microorganisms [29]. It should be noted that the great variability of RGM susceptibility profile, combined with high resistance rates, is in turn a result of the limited effectiveness of current treatment regimens for diseases caused by these microorganisms [66].

Table 2.

MIC values to the standard strains and clinical isolates of RGM exposed to SMTZ and the SMTZ Schiff base derivatives (L1–L6).

Thus, considering the high resistance profile of microorganisms to clinically used antimicrobials, including SMTZ, the products of the reaction between SMTZ and six different aldehydes: pyridoxal hydrochloride (vitamin B6) (L1), salicylic aldehyde (L2), o-vanillin (L3), 3-hydroxy-2-naphthoic acid (L4), 3-allyl salicylaldehyde (L5), and 4-dimethyl salicylic aldehyde (L6) were evaluated in terms of inhibiting CI-I-VII, as well as some standard strains, i.e., M. abscessus, M. fortuitum, M. massiliense, and M. smegmatis. The results of MIC values for SMTZ and its derivatives against the standard strains of RGM, as well as against the clinical isolates, are summarized in Table 2. It was demonstrated that, of the six new molecules evaluated, all inhibited the growth of RGM, with a varied susceptibility profile. It is worth highlighting that L1 had significantly greater efficacy in planktonic inhibition of all microorganisms compared to SMTZ and L2–L6, with MIC values ranging from 1.22 to 0.61 µg mL−1 (Table 2). Overall, L1 had MIC value 0.61 µg mL−1 for M. massiliense, M. smegmatis, and one clinical isolate, while 1.22 µg mL−1 was obtained for M. abscessus, M. fortuitum, and six clinical isolates, better than those obtained with SMTZ.

Although compounds L2–L6 had higher MIC values than L1 in the range of 9.76 to 39.06 µg mL−1, these MIC values are better than those obtained for SMTZ in most of the evaluated RGM (Table 2), indicating that the derivatization of SMTZ leads to an improvement in biological activity. Due to the best biological profile achieved for L1, this compound was also explored in terms of antimicrobial, antibiofilm, and safety profile. Compound L1 contains a pyridoxal moiety that acts in several pathways of metabolism, serving as a coenzyme for the synthesis of amino acids, neurotransmitters (serotonin, norepinephrine), sphingolipids, and aminolaevulinic acid, as well as having high affinity for first and second transition series metals mainly due to the presence of phenolate oxygen and pyridine nitrogen [67,68,69].

It is important to highlight that the clinical use of SMTZ, isolated or associated with trimethoprim, has been decreasing, being used in clinical practice with great restrictions, mainly due to the development of resistant pathogens to sulfonamide [70]. In this sense, the search for novel Schiff bases with an antimicrobial profile is of extreme importance [9], reinforcing our findings as a significant contribution to antimicrobial development. There are no direct reports about SMTZ derivatives with the pathogens strains used in this work; however, from literature to other bacteria strains we can identify the excellent profile detect to L1–L6, e.g., Anacona et al. [71] synthesized, characterized, and determined the antibacterial activity of sulfathiazole-derived Schiff base, proving that the formed Schiff base had antimicrobial activity against Gram-positive (S. aureus) and Gram-negative (E. coli) bacteria, and the hybrid material based on Schiff base with sulfamerazine and salicylaldehyde moieties showed good antimicrobial activity against the same bacteria strains [72]. Additionally, Krátký et al. [73] reported that a series of Schiff bases derived from sulfadiazine were able to inhibit M. tuberculosis, M. avium, and M. kansasii, with MIC values in the range of 8.0 to 250 μM. Moreover, sulfonamide-derived Schiff bases showed varied levels of activity against S. aureus and E. coli strains [74]. Notably, MIC values closer to the upper limit of this range suggest limited clinical relevance, since higher concentrations may indicate reduced affinity or bioavailability of compounds.

A limitation of the present study is the absence of resistance induction assays. Considering the notable adaptive plasticity of rapidly growing mycobacteria, mediated by mechanisms such as efflux pumps, modifications in cell wall permeability, and biofilm formation, it is essential to assess the risk of resistance development to L1. Future studies should include prolonged exposure of RGM strains to subinhibitory concentrations of L1 to evaluate its potential to induce resistance, thereby providing additional evidence to support its validation as a candidate therapeutic agent.

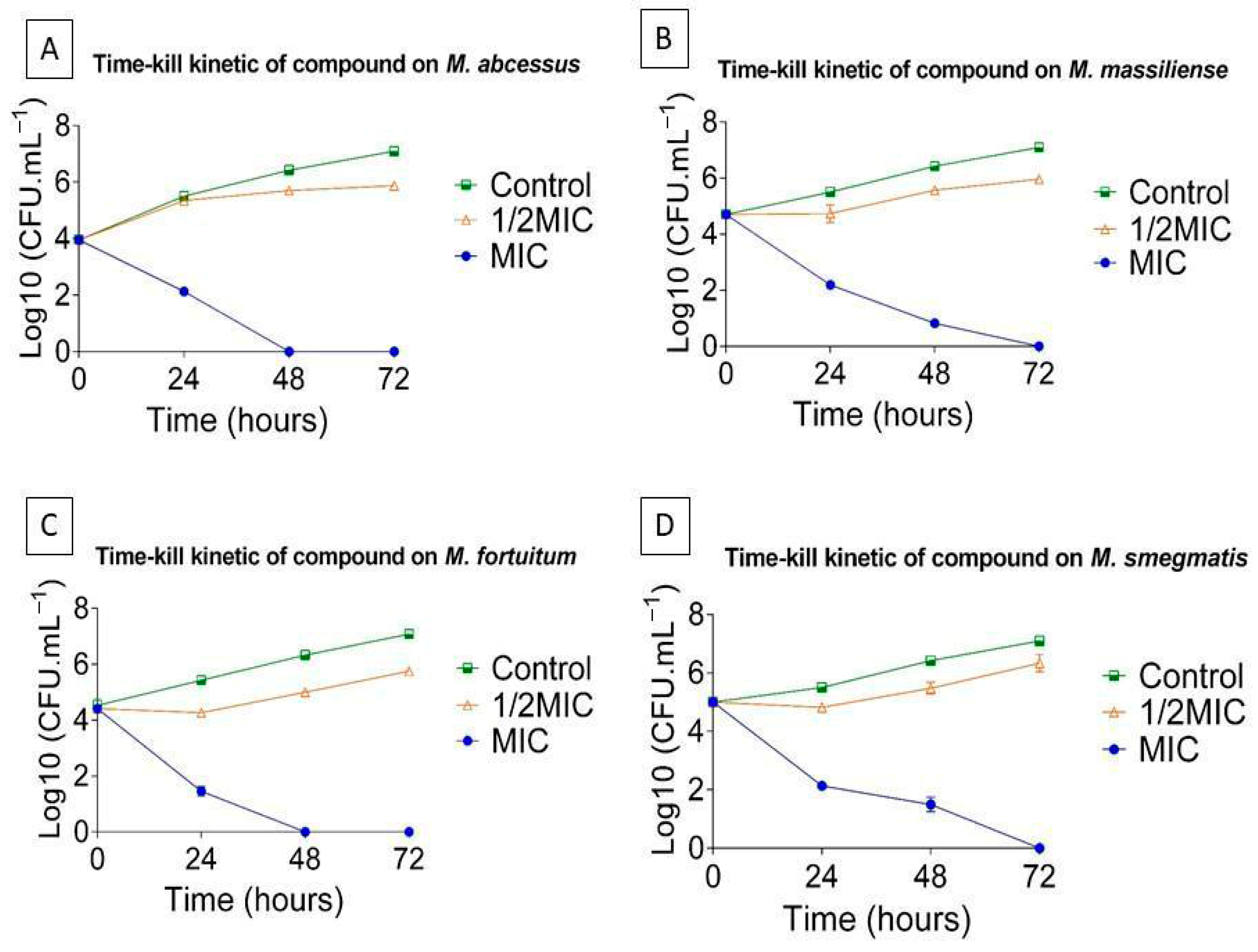

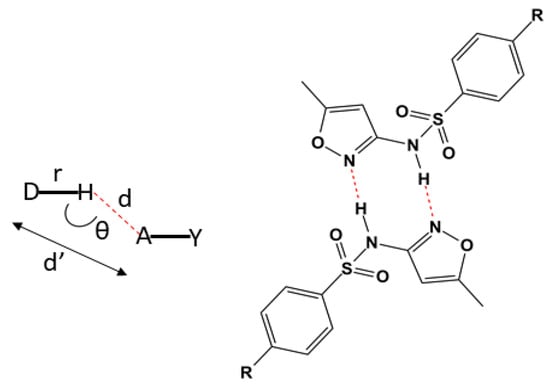

The broth microdilution method was validated by time-kill assays, which provide a dynamic overview of antibiotic activity over time [75], using the most potent antimicrobial candidate, L1, against Mycobacterium abscessus, M. massiliense, M. fortuitum, and M. smegmatis (Figure 4). Bacterial viability of strains treated with 1/2 the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) was assessed through kill curves at 0, 24, 48, and 72 h.

Figure 4.

Time–kill curves of L1 against (A) M. abscessus, (B) M. massiliense, (C) M. fortuitum, and (D) M. smegmatis. Results are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) from four independent experiments (n = 4). The small error bars reflect the low variability among replicates.

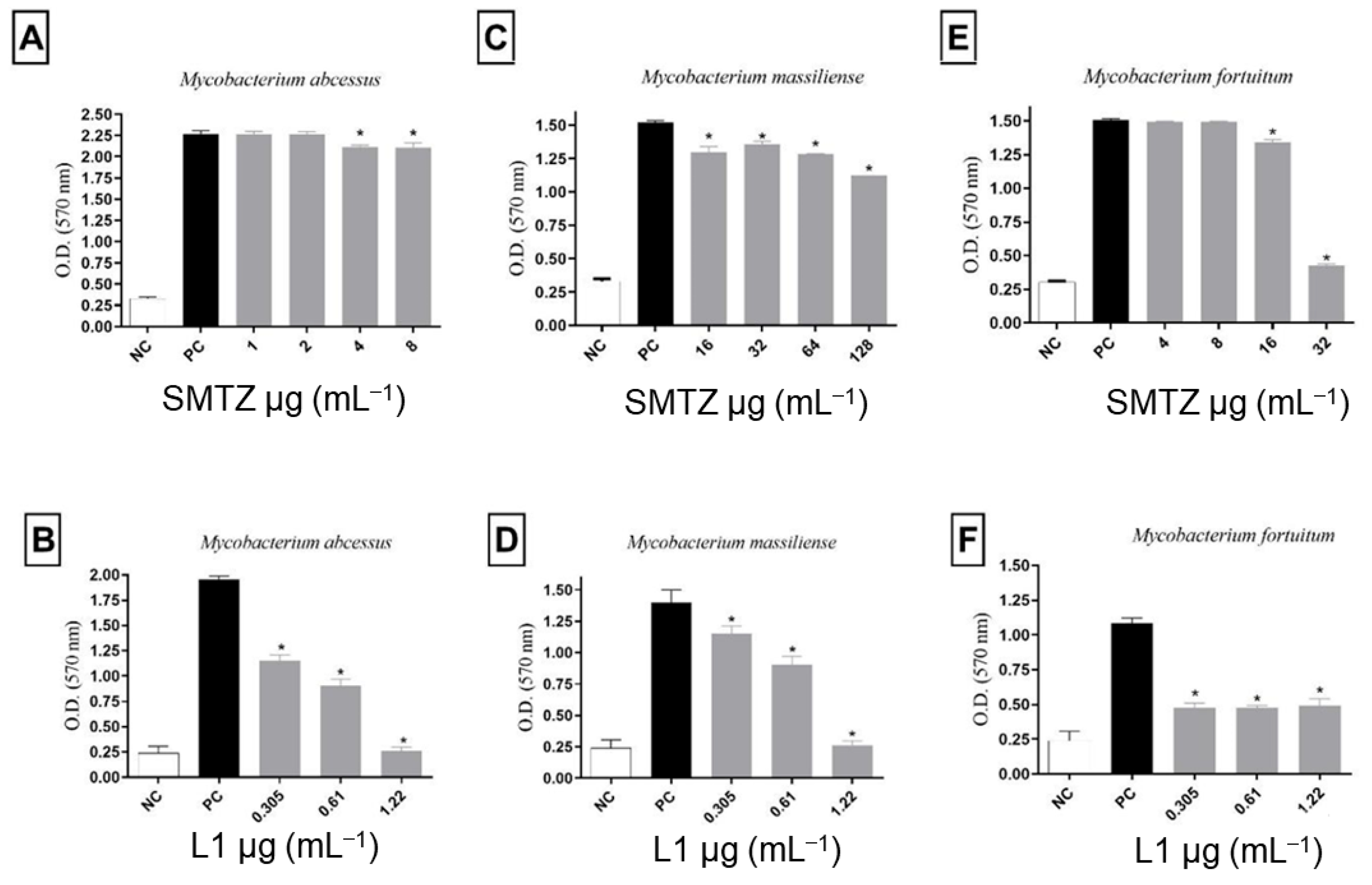

In the biofilm formation assays, sub-inhibitory concentrations of L1 were employed to ensure that planktonic cells remained viable. This approach is crucial, as biofilm development requires metabolically active and viable planktonic bacteria to initiate adhesion to surfaces and proceed through the biofilm maturation process. The use of inhibitory concentrations could suppress bacterial growth entirely, leading to a false-positive interpretation of biofilm inhibition that is due to cell death rather than a specific antibiofilm effect. Therefore, employing concentrations below the MIC allows a more accurate evaluation of the compound’s ability to interfere specifically with the biofilm formation process.

Finally, these data confirmed that treatment with L1 inhibited the biological cycle of biofilm formation, demonstrating the compound’s activity against this structure even in the presence of viable mycobacterial cells.

A large and growing body of evidence offers convincing arguments that the persistence of most microbial species is achieved through biofilm formation. In very hydrophobic microorganisms, such as those of the genus Mycobacterium, biofilm formation is a successful survival strategy [1,75,76]. Biofilms formed by mycobacteria have been reported in environmental studies, especially in water systems. Another important biofilm-related group of infections is those associated with biomaterials, which are considered an important source of infections on biomedical surfaces, including medical device implants such as catheters and prostheses [1,77]. In addition, acute infections caused by microorganisms of the genus Mycobacterium are normally associated with contamination by planktonic organisms, whereas chronic infections seem to be strongly associated with biofilm formation [78]. In our study, M. abcessus, M. massiliense, and M. fortuitum, and three of the seven clinical isolates (CI-IV-VI) formed highly dense and compact biofilms on the air-liquid surface and the surface of polystyrene tubes, as evidenced in Figure S32 of the Supplementary Material [79]. This was not surprising because biofilm development capacity is a property that is not uniformly present among clinical isolates of RGM [80].

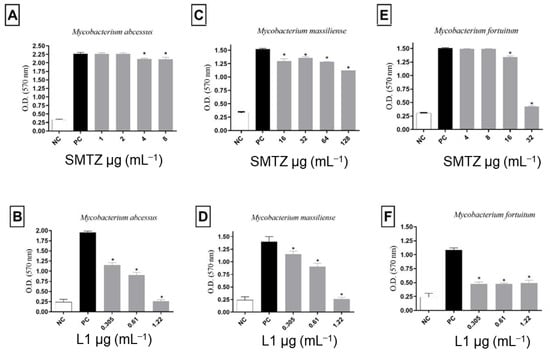

Thus, the effect of sub-inhibitory concentrations of SMTZ and L1 on the biofilm formation of M. abcessus, M. massiliense, and M. fortuitum was evaluated, and the results are summarized in Figure 5. For all microorganisms evaluated, SMTZ showed lower efficacy than L1 in inhibiting biofilm formation. The biofilm from M. abscessus was more sensitive than M. fortuitum to SMTZ. These results agree with previous reports [26,29] that indicated the low efficacy of SMTZ in inhibiting the sessile structure formed by M. abscessus, M. fortuitum, and M. massiliense, reinforcing the importance of the pyridoxal moiety in the SMTZ structure to improve the antibiofilm profile.

Figure 5.

Effect of sub-inhibitory concentrations of SMTZ (top panels: A,C,E) and L1 (bottom panels: B,D,F) on the biofilm formation of M. abscessus, M. massiliense, and M. fortuitum. Bars marked with * indicate a significant difference (p < 0.05) compared with the positive control (PC, untreated bacterial cultures with biofilm formation). The tests were subjected to the Student t-test (n = 3), considering statistical differences when p < 0.05.

Despite SMTZ being a broad-spectrum sulfonamide, considered of great importance in the control of infections caused by different pathogens, including RGM, such as M. abscessus and M. fortuitum [81], it was reported that SMTZ activity decreases significantly when the infectious agent presents itself in the form of biofilms [29,70], as was evidenced not only in Figure 5 for biofilms from M. abcessus, M. massiliense, and M. fortuitum, but also in Figure 6 for biofilms from CI-IV-VI. On the other hand, as indicated in Figure 6, compound L1 inhibited, to some degree, the formation of the biofilms in all concentrations tested to CI-IV-VI. Additionally, the concentrations used for L1 were lower than the concentrations used for SMTZ for all the performed assays, reinforcing the potential biological activity of the novel synthetic compound.

Figure 6.

Effect of sub-inhibitory concentrations of SMTZ (top graphics) and L1 (bottom graphics) on the biofilm inhibition of clinical isolates CI-IV, CI-V, and CI-VI. Bars marked with * indicate a significant difference (p < 0.05) compared with the positive control (PC, untreated bacterial cultures with biofilm formation). The tests were subjected to the Student t-test (n = 3), considering statistical differences when p < 0.05.

Several studies have reported the antibiofilm activity of different Schiff bases, but the present work reports for the first time the antibiofilm activity of a Schiff base derived from SMTZ against RGM. More et al. [82] showed the antibiofilm activity of thiazole Schiff bases against Gram-positive microorganisms, while Arshia et al. [83] evaluated the synthetic 2-amino-5-chlorobenzophenone Schiff base against biofilms formed by Gram-negative microorganisms, and the antibiofilm activity of chitosan derivative Schiff base [8] found that this organic compound completely instilled the formation of biofilms of P. aeruginosa. In this sense, we can speculate that inhibition of biofilm formation of M. abscessus, M. fortuitum, and M. massiliense by the Schiff base synthesized in our work (L1) might act mainly in two different ways: (I) avoiding the microorganism’s surface, by inhibiting physical-chemical interactions that mediate this process; and/or (II) as an inhibitor of cellular communication of the sessile community, known as Quorum sensing [84]. Thus, the new synthetic compound would act by inhibiting the signaling of the stages of the biological cycle of the formation of mycobacterial biofilm. However, new in vitro and in vivo experimental trials should be performed to elucidate the exact mechanism by which this Schiff base inhibits biofilm formation.

Moreover, since the Schiff base formed is structurally presented as an imine functional group, we highlight the greater lipophilicity of the organic compound when compared to the corresponding amino group [10]. This is a limiting factor in the antibacterial activity of new molecules, since microorganisms of the Mycobacterium genus have a thick, highly hydrophobic and lipid cell wall rich in mycolic acids, making them waterproof to disinfectants and antimicrobials, thus hindering its inhibition, both in the planktonic form and in the sessile form [85]. The promising activity of our molecule as an inhibitor of the formation of mycobacterial biofilms is extremely relevant, since biologically active substances against this sessile structure are increasingly scarce. Flores et al. [29] evaluated the antibiofilm effect of antimicrobials used in the therapy of mycobacteriosis and concluded that biofilms formed by RGM are resistant to antimicrobials commonly used in mycobacteriosis therapy. The antibiotics tested included amikacin, ciprofloxacin, clarithromycin, doxycycline, imipenem, and SMTZ.

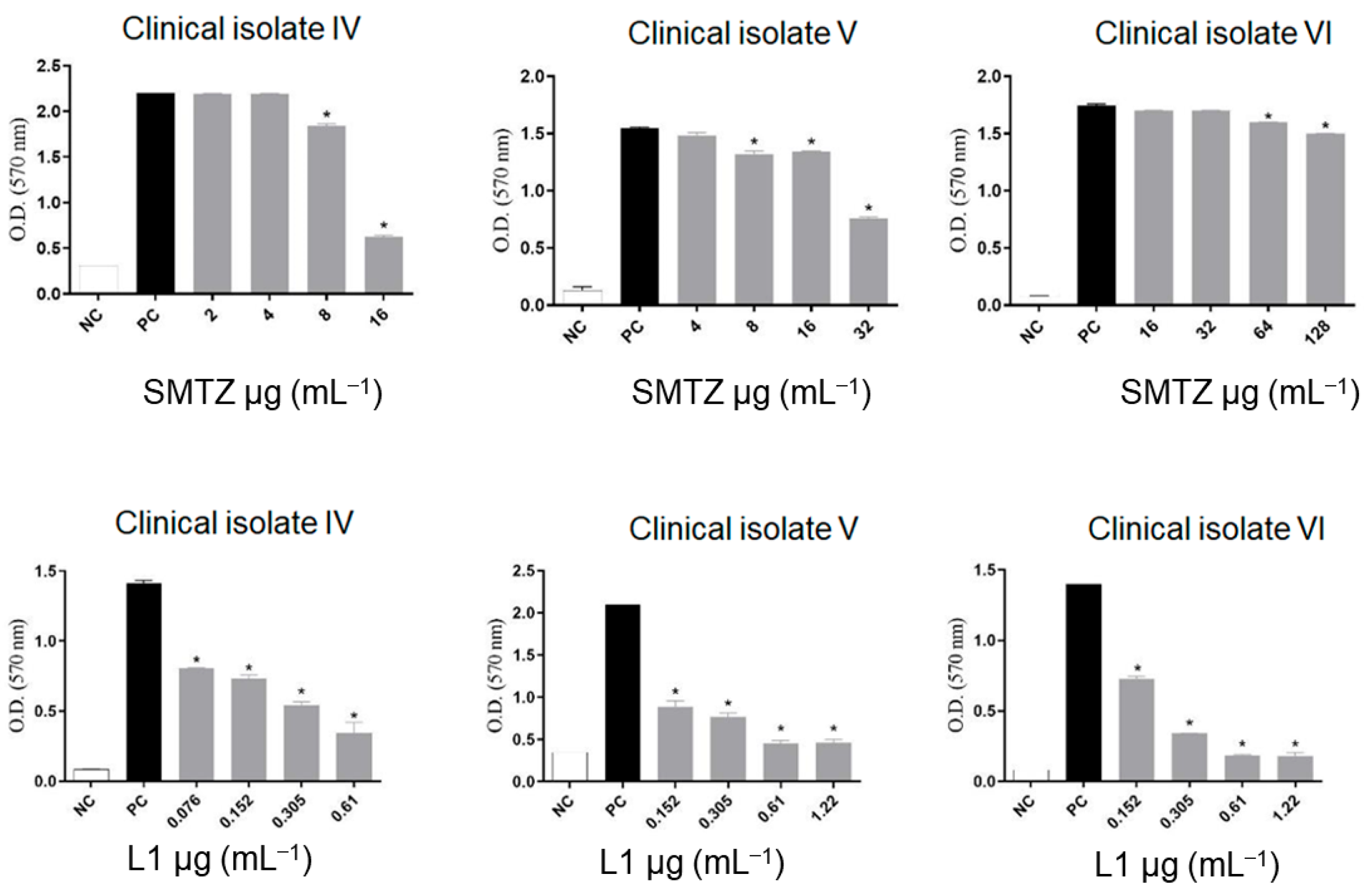

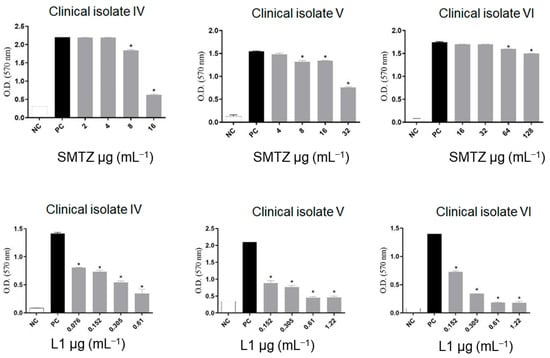

Since L1 has potential antimicrobial and antibiofilm activity, it is of great importance to evaluate its safety to comply with the basic principle of pharmacology, which says that molecules with biological activities must also be safe at the concentration of effectiveness [86]. Thus, the concentration chosen for the compound to evaluate cellular effects was selected based on previously obtained MIC results. All methodologies used for the in vitro cytotoxicity evaluation are listed in the Supplementary Materials. Cell viability after treatment with the Schiff base was evaluated using the MTT technique and the free dsDNA quantification using the Picogreen® reagent. Both results demonstrated a safe and similar profile of cellular viability. When comparing the results with the positive control, the treatments with the new molecule tested presented a satisfactory safety profile in the cell viability of the model used. In contrast, positive control (oxygen peroxide, H2O2) presented a significant decrease in cellular viability. All tested concentrations of L1 maintained the cellular viability index, like that of the negative control (NC). Additionally, the treatments did not significantly change the dsDNA release compared to untreated cells. Cells treated with H2O2 showed an increased amount of extracellular dsDNA, as expected, possibly due to the membrane damage (Figure 7A,B).

Figure 7.

Cytotoxic analysis in PBMCs exposed to L1 for 24 h. (A) Cellular viability assessed by the MTT assay. (B) Free dsDNA quantification. (C) Total levels of ROS measured using 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA). (D) Indirect quantification of NO. Bars marked with * indicate a significant difference (p < 0.05), and bars marked with *** indicate a significant difference (p < 0.01) compared with the negative control. The tests were subjected to the Student t-test (n = 3).

In addition, it is important to highlight that some microorganisms, such as M. tuberculosis, can induce cellular death through mitochondrial modulation, directly modulating cellular oxidative metabolism [87]. However, some antimicrobial molecules act by inducing oxidative stress. In this regard, we must consider that high production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) can be highly disastrous to eukaryotic cells, thus limiting their use as an antimicrobial agent [88]. Given this, after the incubation period, the PBMCs were also evaluated in terms of ROS levels and nitric oxide (NO) production in the presence of L1. None of the concentrations analyzed here was able to modify ROS levels compared to the negative control. Moreover, most of the concentrations also kept NO production to a similar amount found for untreated cells, except for the highest concentrations tested, which caused a slight increase in NO levels. As expected, H2O2 exposure causes an increased production of ROS and NO compared to the negative control (Figure 7C,D).

Finally, the broad safety margin observed for L1 in PBMCs may be associated with its chemical structure. L1 is derived from sulfamethoxazole, a clinically used sulfonamide with a well-established safety profile, and pyridoxal hydrochloride, a derivative of vitamin B6, which is a natural cofactor with low toxicity. The combination of two relatively safe building blocks might contribute to the reduced cytotoxicity observed, even at higher concentrations. It is important to highlight that the inclusion of additional cell types in future assays, such as macrophages or pulmonary epithelial cells, could provide further translationally relevant data, since these cells are directly involved in infections caused by RGM. Finally, while our initial results are encouraging, future studies must address pharmacokinetic and bioavailability assays in animal models, optimized formulations, as well as investigations on resistance risk and immunological impact. These steps are fundamental to overcoming translational barriers and advancing the development of L1 as a viable therapeutic candidate against RGM.

3.3. Computational Approach

3.3.1. DFT Study

Initially, the electron transfer behavior for L2–L6 was evaluated using the obtained experimental X-ray structures and the DFT optimized geometries for L1 (Figure S33 in the Supplementary Materials). The Frontier orbitals LUMO/HOMO, energy gap (Eg), chemical potential (µ), hardness (η), and electrophilicity index (ω), were obtained by the DFT approach, and the results are summarized in Table 3. After comparing the six structures, it was observed that the molecular structures of L4 and L6 underwent intramolecular electron transfer, shifting from -OH to -NH, consistent with the results from the DFT calculations, once these molecules showed the two smallest energy differences between the HOMO and LUMO orbitals, at 3.36 eV and 3.30 eV, respectively. These values are significantly lower than those of L2, L3, L6, and L1, which were 3.89, 3.89, 3.94, and 3.89 eV, respectively. For these four compounds, no electron transfer was observed, and the -OH group remains in the molecular structure.

Table 3.

Quantum descriptors, HOMO and LUMO frontier orbitals, energy gap (Eg), chemical potential (µ), hardness (η), and electrophilicity index (ω) in eV for L1–L6.

Since compound L1 exhibited the highest biological activity, we applied advanced computational chemistry methods to elucidate its quantum reactivity and to understand the interactions with biological receptors. Thus, the density distribution and energy levels (B3LYP/6-311++G(d,p)) for the L1’s frontier molecular orbitals, HOMO-1, HOMO, LUMO, and LUMO+1, are represented in Figure S34 in the Supplementary Materials. Generally, molecules with a low gap between HOMO and LUMO orbitals and low hardness present higher biological activity [14,15]. However, in this study, it was found that the L1 structure was more active, which is probably due to two plausible reasons. First, the lower energy of the L1’s HOMO orbital would facilitate the transfer of charge to the LUMO of the receptor, and L1 is the compound with a more negative chemical potential, generally associated with high stability [89]. Then, these two characteristics together serve as decisive factors in the current biological mechanism. A distinct combination of L1’s HOMO orbital energy and the kinetics (rate of charge transfer), established by high stability due to the lowest chemical potential, likely leads to higher biological activity (Figure S34 in the Supplementary Materials). In this sense, there is a direct correlation between quantum descriptors (Table 3) and experimental results (Table 2). For all the cases, the SMTZ Schiff base derivatives with the lowest energy for the HOMO orbital, as well as the lowest chemical potential (µ), showed higher inhibition, L1.

Furthermore, the Fukui functions were applied with NCI and RDG to evaluate the true nature of interactions in the most active compound L1, to correlate with its high antimicrobial activity. The nucleophilic (f+), electrophilic (f−), neutral (f0), and dual-descriptor (f2) Fukui functions for L1 are represented in Figure S35 in the Supplementary Materials with low and high isosurface levels. The f+ function highlighted the reactivity of the atoms in terms of their potential for a nucleophilic attack. Figure S35 in the Supplementary Materials and Table 4 indicate that atoms N2, C7, N8, O11, and C16 are likely to participate in a nucleophilic attack, considering their low HOMO and HOMO-1 energy, transferring electron density to the microbial target, resulting in its elimination. Alternatively, the f− function is related to the reactivity of the atoms in terms of their ability to act as electrophilic agents, i.e., to receive electron density from the HOMO orbitals of microbial, charging the L1 LUMO and LUMO-1 orbitals. The atoms that can receive electron density are C1, C3, N8, O11, C16, N20, O21, O22, C25, and N27. Interestingly, according to the low isosurface in Figure S34 in the Supplementary Materials, the N2 can act as a nucleophilic and electrophilic agent, but the latter is the more reasonable due to its higher isosurface at Fukui function f− when compared with f+, agreeing with the Fukui dual-descriptor function, f2. This behavior indicates that N2 can receive NCI, forming a H-bond, or receive a covalent nucleophilic attack in the biological environment.

Table 4.

Molecular docking score value (dimensionless) for the interaction between L1–L6 and three different biomacromolecules.

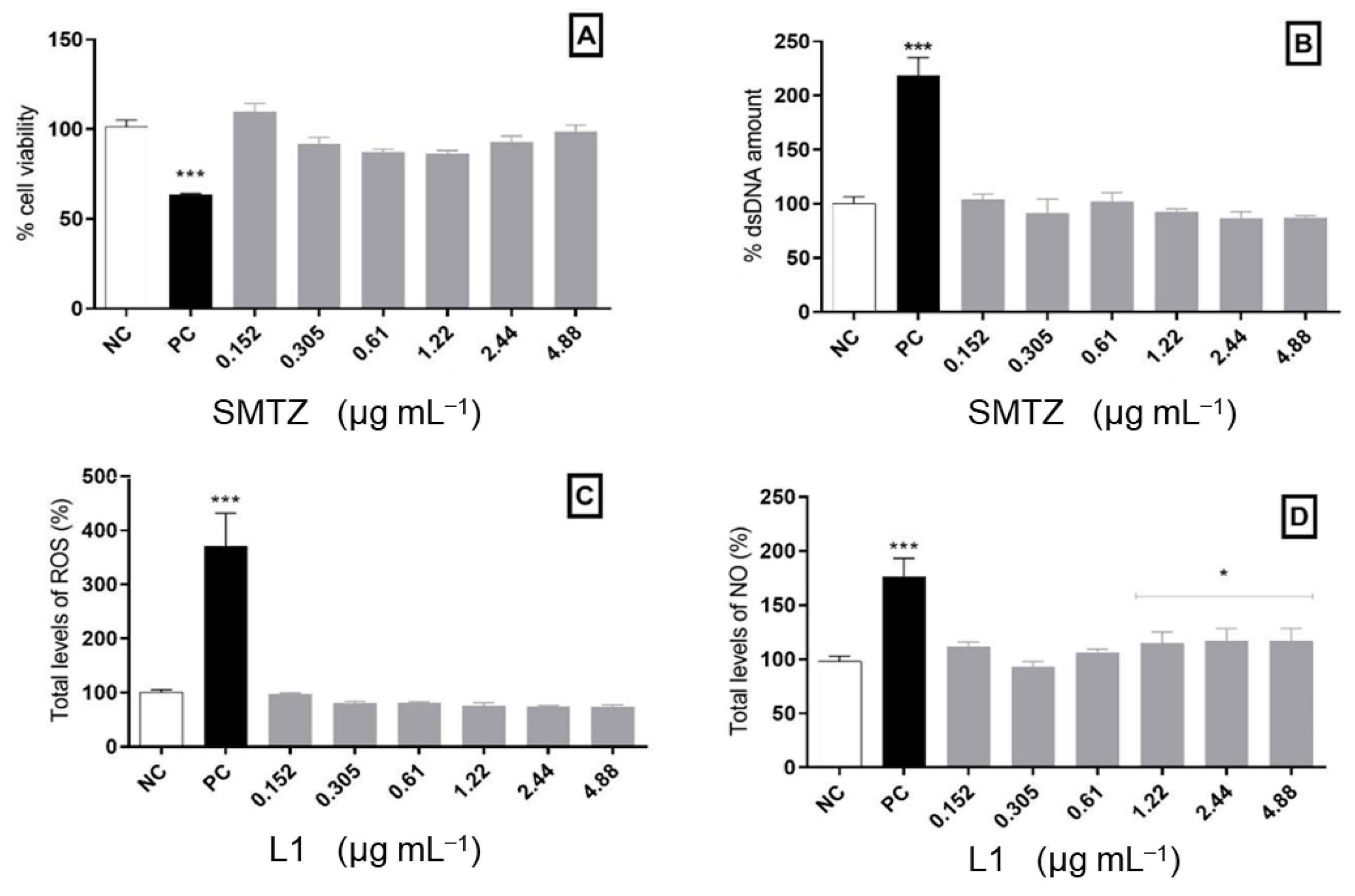

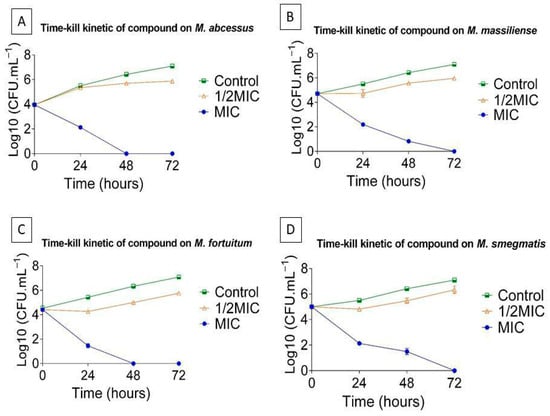

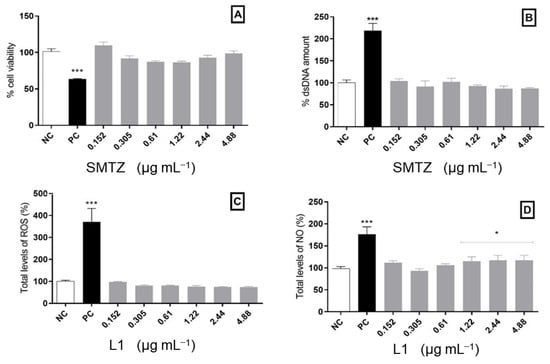

The NCI and RDG representations in Figure 8 show the dominance of the steric effect in L1, as indicated by the red color, in comparison with other interactions, such as strong hydrogen bonds and weak Van der Waals forces. The same behavior was demonstrated by Kiruthika et al. [90], in which imidazole species exhibited antimicrobial activity. In regions involving carbon atoms within heterocycles or aromatic rings, significant repulsive interaction occurs between the carbons C1, C3, C4, C5, C6, and C23, C24, and C25. It can also happen in non-cyclic carbons such as C4, C5, and C7, highlighting a pronounced steric effect. This interaction is depicted by red coloration on the RDG plot, ranging from 0.02 to 0.05 sign(λ2)ρ. Differently, blue color indicates the hydrogen bond, more specifically in N8…H34O11, with sign(λ2)ρ values between −0.05 and −0.03. On the other hand, green represents van der Waals interactions, such as those between C7H30…C13 and C12H36…O11, within sign(λ2)ρ values between −0.01 to 0.01. Interestingly, as can be observed, these interactions occur with oxygen atoms rather than nitrogen. The same behavior was also observed by other authors [91]. Overall, the obtained DFT data indicated that L1 exhibits electronic features favorable to interaction with biological targets, such as the lowest HOMO energy and a more negative chemical potential—parameters associated with greater stability and charge-transfer capability. This combination enables more efficient electron transfer to the LUMO of biological receptors, potentially facilitating stable, high-affinity interactions with protein active sites.

Figure 8.

The NCI isosurface (A) and RDG sign(λ2)ρ plot (B) for the pyridoxal. For both graphics, blue represents a strong attractive force, green signifies a very weak interaction, while red denotes a strong repulsive force.

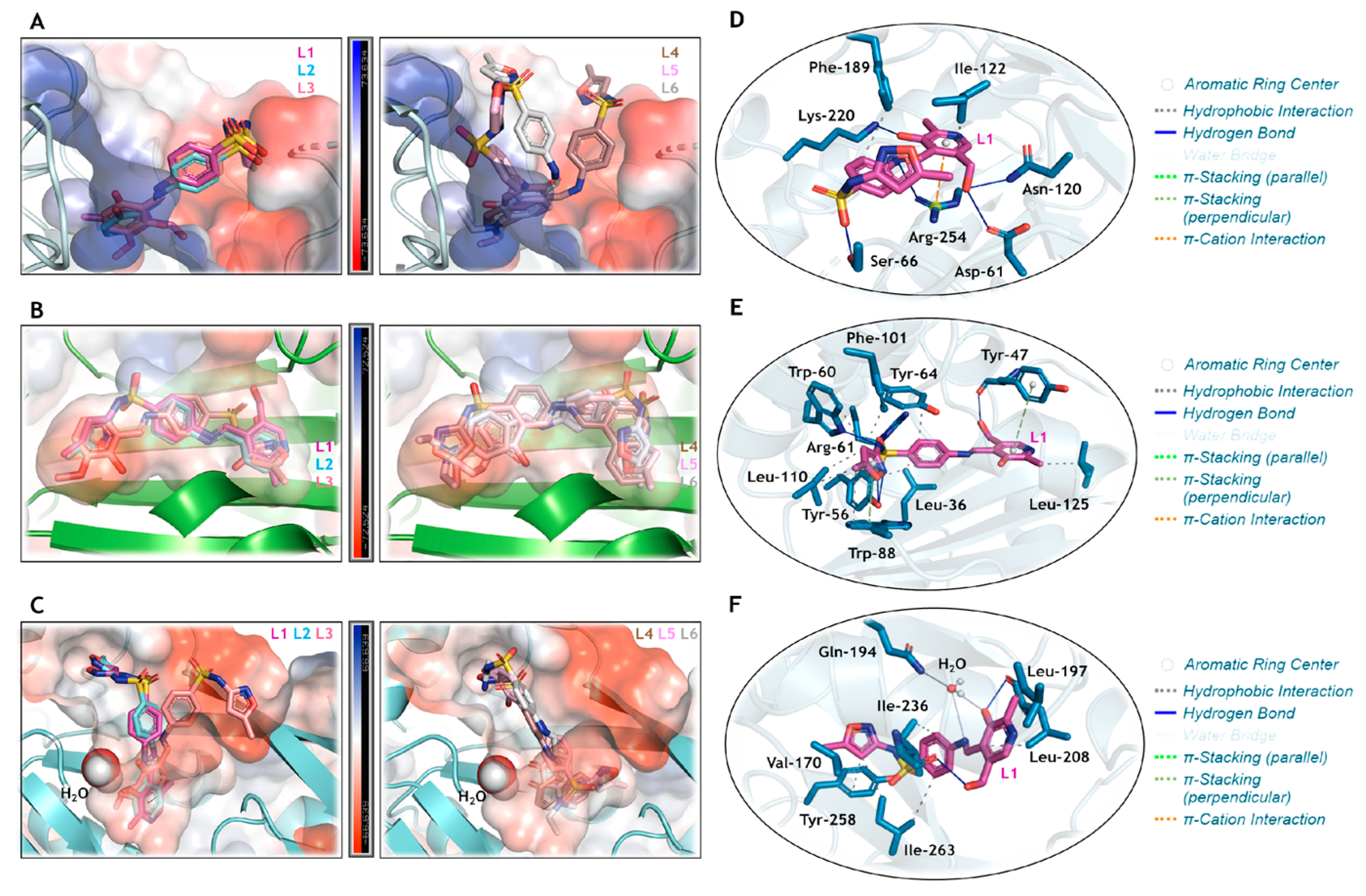

3.3.2. Molecular Docking Calculations

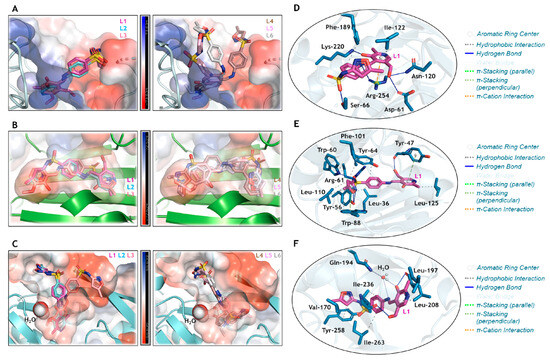

The SMTZ and its inorganic derivatives based on Cd(II), Ag(I), Ni(II), Hg(II), Cu(II), and Au(I) were previously evaluated against three feasible antibacterial targets: DHS, LasR, and PqsR, and a good correlation between in silico approach and in vitro results were found [42,92,93]. Thus, molecular docking calculations were carried out for the same protein targets to offer a molecular-level explanation of the antimicrobial activity of the SMTZ derivatives Schiff bases under study (L1–L6). The docking score values (dimensionless) are summarized in Table 4, while the corresponding docking poses are depicted in Figure 9. The highest docking score values were obtained for LasR, suggesting this protein as the main target. The Schiff bases L1–L6 had higher docking score values than those obtained for SMTZ [42] to LasR, which agrees with the experimental data indicating better MIC values for L1–L6 than for SMTZ in most standard strains and clinical isolates of RGM. Despite L1–L6 showing hydrophobic and hydrogen bonds as the main intermolecular forces to stabilize the interaction with the targets DHS, LasR, and PqsR (Figure 9), the highest docking score values were obtained for LasR, mainly due to the capacity of L1–L6 in being fully buried into the pocket of this protein (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Superposition of the heterocyclic compounds L1–L3 and L4–L6 into the electrostatic potential map of (A) DHS, (B) LasR, and (C) PqsR. The zoom representation for L1 (in pink) into the catalytic pocket of (D) DHS, (E) LasR, and (F) PqsR, highlighting the main amino acid residues (in blue) that interact with L1. For better interpretation, hydrogen atoms were omitted. Oxygen, nitrogen, and sulphur in red, dark blue, and yellow, respectively.

Curiously, a superposition of the docking pose for L1–L3 was evidenced in the catalytic pocket of DHS (Figure 9A), LasR (Figure 9B), and PqsR (Figure 9C). These SMTZ derivatives were those that were experimentally detected with the lowest MIC values compared to L4–L6 (Figure 9A–C), indicating the impact of iminium (L1–L3) and enamine (L4 and L6) forms, and the nature of the chemical moiety covalently bound to the base Schiff group on the biological activity, as described in Section 3.3.1. Since L1 was experimentally detected as the most potent antibacterial compound, its interactive capacity with the amino acid residues of the proteins DHS (Figure 9D), LasR (Figure 9E), and PqsR (Figure 9F) was analyzed, indicating that the isoxazole moiety is not crucial to the interactive profile with the proteins. Finally, the asymmetric distribution of Mulliken atomic charge (Figure S36 in the Supplementary Materials) in the L1 structure corroborates the compound’s capacity to interact with positive or negative electrostatic potential maps for DHS, LasR, and PqsR. Interestingly, there was a direct relationship between quantum reactivity (Table 3) and docking scores (Table 4). As shown in Figure S36, the oxygen atoms with the lowest Mulliken charge in L1 are O10 and O11, both participating in hydrogen bonds (Figure 9D–F). This intermolecular interaction represents the most relevant energetic stabilization contribution, which is associated with the greatest inhibition observed both experimentally and in silico (Table 4). Furthermore, for LasR and PqsR, the compound with the lowest-energy HOMO orbital and lowest chemical potential (µ) had a higher score. In contrast, for DHS, the most active compound was the one with the lowest Eg and η, in agreement with reports in the literature [90].

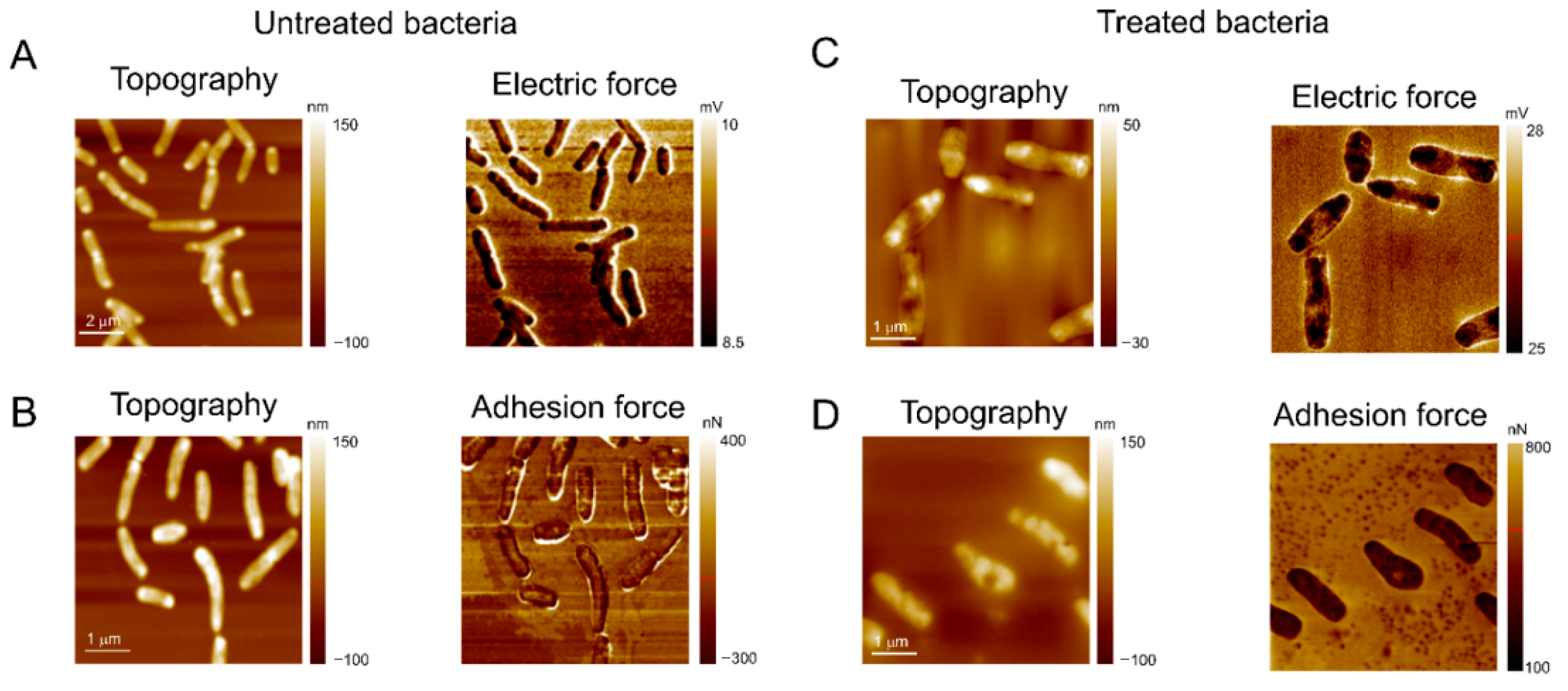

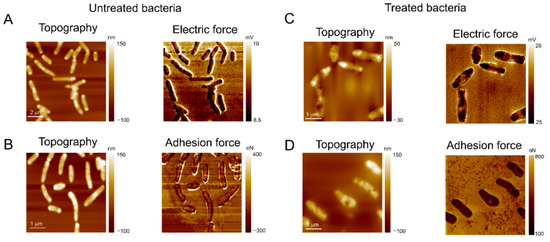

3.4. Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) Analysis

The effect of the treatment with L1 on the topography, electrostatic, and adhesion force properties of M. smegmatis, as a model due to its high sensitivity in the presence of L1 (Table 2), was evaluated by AFM analysis. As depicted in Figure 10A,B, the topography images displayed the expected feature for untreated mycobacteria, i.e., a rod-shaped morphology structure. On the other hand, as depicted in Figure 10C,D, the bacilli are significantly modified after the treatment with L1 under the MIC value, exhibiting a non-specific morphology, but with evidence of ellipsoids of revolution with withered regions. The membranes of mycobacteria are very susceptible to the treatment, undergoing large deformations and displaying many holes all over their surface.

Figure 10.

The AFM images of M. smegmatis after incubation for 24 h at 30 °C. (A,B) Negative control image (bacterial inoculum and Müeller Hinton broth culture medium); the images demonstrate (A) the microorganism’s electrical force and (B) adhesion force parameters, as well as their topographies, without treatment with L1. (C,D) Images of M. smegmatis after treatment with MIC value provided for the compound L1 (0.61 µg mL−1); the images demonstrate the altered parameters of (C) electrical force and (D) adhesion force of the microorganism, as well as their topographies damaged by the action of the compound.

In addition to morphological changes, the treatment with the compound also affected the adhesion force on mycobacterial walls. As shown in Figure 10B,D, the adhesive forces on the untreated bacteria membrane are roughly 0.140 μN but increase up to 0.29 μN. These data offer insights that the treatment with the compound L1 might cause damage to the mycobacteria by changing the organic functions of the membrane structure. This facilitates the AFM tip nanoindentation on the bacterial wall, inducing a higher contact area and following a subsequent increase in the adhesive forces (pull-off force), where a similar effect was also observed [94,95]. Moreover, the adhesion force map shown in Figure 10B indicates a higher adhesive force at the border between the bacteria surface and substrate, but after treatment, the adhesive force at the mycobacteria perimeter is decreased (Figure 10D).

This evidence suggests that the compound also reduces the bacteria’s interfacial adhesion, which must contribute to decreasing bacterial growth rates on the substrates. Figure 10A and Figure 10C show the topography and electric force maps for the mycobacteria, untreated and treated with L1, respectively. In AFM maps, dark regions are relatively more negative, while brighter ones indicate positively charged regions. Thus, the electric force maps in Figure 10A indicate that the mycobacterial membrane is much more negative than the substrate, being clear evidence that electrostatic forces must also mediate the adhesion of the bacteria to the substrate [28,96]. The electrostatic component between the mycobacterial membrane and substrate does not show significant changes after the treatment with L1, but many negative regions were found on the bacterial walls. Finally, most of the higher topography dots correspond to negative regions, while on withered spots the bacterial membrane is positively charged, highlighting its destabilization due to the L1 treatment.

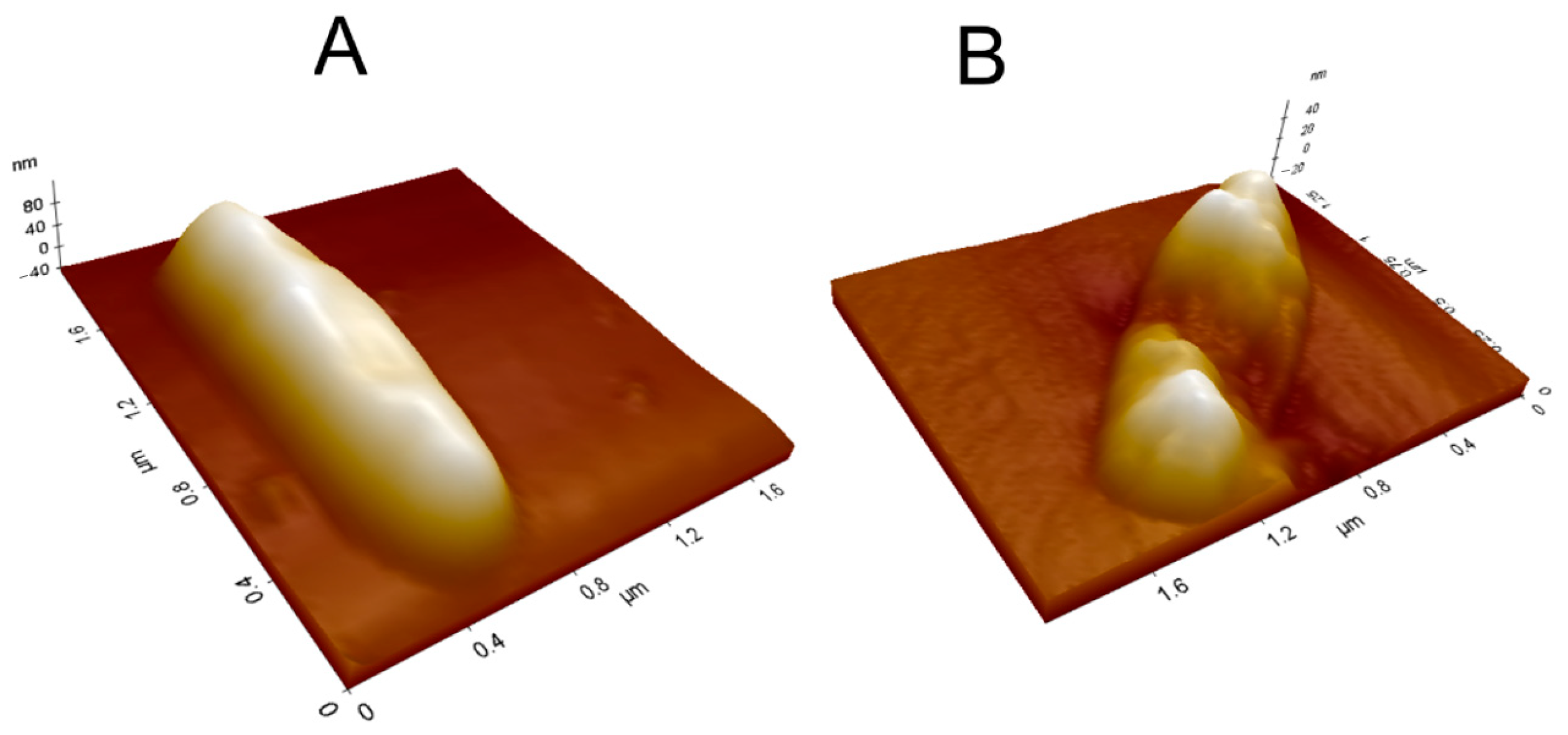

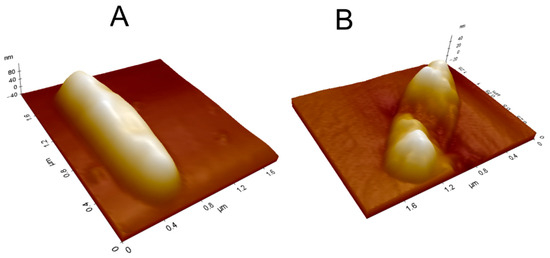

The AFM measurements on mycobacteria are timely, i.e., the effect of the treatment with L1 is easily observed on topography, adhesion, and electric force images. The AFM 3D image reconstruction feature is even more suitable to evidence the deformation of the bacterial wall after the treatment. Figure 11 shows 3D topographic images of M. smegmatis, where a withered region is observed after L1 treatment under MIC value (0.61 μg mL−1).

Figure 11.

The 3D topographic images of M. smegmatis (A) before and (B) after L1 treatment under MIC value (0.61 µg mL−1).

4. Conclusions

The derivatization of SMTZ through the incorporation of the pyridoxal moiety in L1 significantly enhanced the antimicrobial and antibiofilm activity against RGM, positioning this compound as the leading representative of a new generation of promising derivatives (L1–L6). Among them, L1 exhibited the lowest MIC values for standard strains (M. abscessus, M. fortuitum, M. massiliense, and M. smegmatis) and RGM clinical isolates, ranging from 0.61 to 1.22 µg mL−1, reflecting the synergistic effect of the sulfonamide and pyridoxal groups in disrupting essential metabolic pathways. Molecular docking studies demonstrated that L1 interacts effectively with the DHS, LasR, and PqsR targets, with LasR identified as the primary target. The analyses revealed that the compound fully occupies the protein pockets, forming hydrophobic and hydrogen bond interactions, while the asymmetric distribution of Mulliken charges favors binding to both positively and negatively charged electrostatic regions. The superposition of L1–L3 in the catalytic pockets of DHS, LasR, and PqsR underscores the importance of the iminium form and the chemical nature of the pyridoxal moiety in biological activity, consistent with the observed low MIC values. Finally, the atomic force microscopy (AFM) analysis confirmed that L1 treatment induces profound structural and biophysical alterations in M. smegmatis. Changes in cell topography, withered membrane regions, increased adhesion forces, and disrupted surface charge distribution indicate compromised membrane integrity. Additionally, reduced interfacial adhesion suggests diminished biofilm formation, reinforcing the compound’s antibiofilm effect. Overall, the integration of in vitro, in silico, and AFM results demonstrates that L1 acts through multifactorial mechanisms on RGM, combining direct antimicrobial activity with interference in virulence and adhesion processes. This study is novel, with no prior reports of SMTZ derivatives evaluated against the same clinical RGM isolates, highlighting that minor chemical modifications, such as the addition of the pyridoxal group, can produce substantial improvements in biological activity, as was also reinforced with low toxicity and high in vitro biocompatibility for L1–L6 derivatives, establishing L1 as a promising candidate for preclinical studies. These findings underscore the importance of an integrated approach, combining chemical synthesis, microbiological evaluation, molecular docking, and nanoscale analyses, for the development of targeted, effective, and potentially personalized antimicrobial therapies.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/futurepharmacol5040072/s1, S1. Spectroscopic data of the ligands L1–L6. S2. FTIR—Infrared analysis. S3. FIA-ESI-MS Analysis. S4. Crystal data and data collection, and refinements of ligands L2–L6. S5. ORTEP projection of the molecular structures of the ligands L2–L6. S6. Clinical isolates and phenotypical identification. S7. Breakpoints for interpreting susceptibility tests. S8. Formation of clinical isolate biofilms. S9. In vitro cytotoxicity evaluations. S10. Computational data. S11. Supplementary references.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.d.S.S., D.F.B. and M.A.d.C.; methodology, F.d.S.S., J.D.S., T.A.d.L.B., C.S., D.F.B. and M.A.d.C.; software, C.S., O.A.C. and Y.C.A.S.; validation, F.d.S.S., D.F.B. and M.A.d.C.; formal analysis, J.D.S., A.K.M., M.R.S., M.F.L., O.A.C., D.F.B. and M.A.d.C.; investigation, F.d.S.S., J.D.S., A.K.M., M.R.S., T.A.d.L.B., D.F.B. and M.A.d.C.; resources, D.F.B. and M.A.d.C.; data curation, F.d.S.S., O.A.C., D.F.B. and M.A.d.C.; writing—original draft preparation, F.d.S.S., O.A.C., Y.C.A.S., T.A.d.L.B. and D.F.B.; writing—review and editing, F.d.S.S., O.A.C., Y.C.A.S. and D.F.B.; visualization, F.d.S.S., O.A.C. and Y.C.A.S.; supervision, O.A.C., D.F.B. and M.A.d.C.; project administration, D.F.B. and M.A.d.C.; funding acquisition, D.F.B. and M.A.d.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Brazilian Research Councils: Conselho Nacional do Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (PQ-2022; 308411/2022-6 and N° 32/2023 Pós-Doutorado Júnior—PDJ 2023 174545/2023-1) and Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES-PROEX, 001). The Coimbra Chemistry Centre—Institute of Molecular Sciences (CQC-IMS), which is supported by the Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (FCT), Portuguese Agency for Scientific Research. CQC is funded by FCT through projects UID/PRR/00313/2025 (https://doi.org/10.54499/UID/PRR/00313/2025) and UID/00313/2025 (https://doi.org/10.54499/UID/00313/2025) and IMS through special complementary funds provided by FCT (project LA/P/0056/2020 https://doi.org/10.54499/LA/P/0056/2020).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The experiments were conducted by an experimental protocol approved by the ethics committee of the Universidade Federal de Santa Maria (UFSM, Brazil) for research involving clinical isolates (CAAE number: 71795417.6.0000.5346, approved on 28 August 2017). The peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) derived from discarded total blood samples of healthy adults were obtained from the Clinical Analysis Laboratory (LEAC) of the Franciscan University (UFN, Brazil) (experimental protocol approved by UFN ethics committee for research with human beings, CAAE number: 31211214.4.0000.5306, approved on 3 August 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article or Supplementary Materials.

Acknowledgments

OAC acknowledges Programa de Pós-Graduação em Biologia Celular e Molecular from Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (Rio de Janeiro, Brazil) and CAPES for the grant PIPD (process SCBA 88887.082745/2024-00 with subproject 31010016).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Niño-Padilla, E.I.; Velazquez, C.; Garibay-Escobar, A. Mycobacterial biofilms as players in human infections: A review. Biofouling 2021, 37, 410–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varghese, B.; Enani, E.; Shoukri, M.; AlThawadi, S.; AlJohani, S.; Al-Hajoj, S. Emergence of rare species of nontuberculous mycobacteria as potential pathogens in Saudi Arabian clinical setting. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2017, 11, e0005288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowman, S.; Burns, K.; Benson, S.; Wilson, R.; Loebinger, M.R. The antimicrobial susceptibility of non-tuberculous mycobacteria. J. Infect. 2016, 72, 324–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Pozo, J.L. Biofilm-related disease. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 2018, 16, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, K. Persister cells: Molecular mechanisms related to antibiotic tolerance. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 2012, 211, 121–133. [Google Scholar]

- Woolhouse, M.; Farrar, J. Policy: An intergovernmental panel on antimicrobial resistance. Nature 2014, 509, 555–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, J. Tackling Drug-Resistant Infections Globally: Final Report and Recommendation; Welcome Trust: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, S.S.; Kenawy, E.; Sonbol, F.I.; Sun, J.; Al-Etewy, M.; Ali, A.; Huizi, L.; El-Zawawy, N.A. Pharmaceutical potential of a novel chitosan derivative Schiff base with special reference to antibacterial, anti-biofilm, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, hemocompatibility and cytotoxic activities. Pharm. Res. 2018, 36, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, A.; Al-Rashida, M.; Uroos, M.; Ali, S.A.; Khan, K.M. Schiff bases in medicinal chemistry: A patent review (2010–2015). Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2017, 27, 63–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin Break, M.K.; Tahir, M.I.M.; Crouse, K.A.; Khoo, T.J. Synthesis, characterization, and bioactivity of Schiff bases and their Cd2+, Zn2+, Cu2+ complexes derived from chloroacetophenone isomers with S-benzyldithiocarbazate and the X-ray crystal structure of S-benzyl-β-N-(4-chlorophenyl)methylenedithiocarbazate. Bioinorg. Chem. Appl. 2013, 2013, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.; Fazal, Z.; Alam, A.; Ibrahim, M.; Ali, T.; Ali, M.; Khan, H.D. Synthetic Transformation of 4-Fluorobenzoic Acid to 4-Fluorobenzohydrazide Schiff Bases and 1,3,4-Oxadiazole Analogs Having DPPH Radical Scavenging Potential. Lett. Drug Des. Discov. 2023, 20, 2018–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakoor, A.; Fareed, G.; Ahmad, I.; Elhenawy, A.A.; Khan, M.; Fareed, N.; Ibrahim, M. Exploring the Anti-Diabetic Activity of Benzimidazole Containing Schiff Base Derivatives: In Vitro α-Amylase, α-Glucosidase Inhibitions and In Silico Studies. J. Mol. Struct. 2025, 1321, 140136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakoor, A.; Jan, F.; Rahman, S.; Ali, M.; Ibrahim, M.; Khan, H.; Khan, M. Synthesis, Urease Inhibitory Activity, Molecular Docking, Dynamics, MMGBSA and DFT Studies of Hydrazone-Schiff Bases Bearing Benzimidazole Scaffold. Chem. Biodivers. 2025, 22, e202402096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Farraj, E.S.; Qasem, H.A.; Aouad, M.R.; Al-Abdulkarim, H.A.; Alsaedi, W.H.; Khushaim, M.S.; Feizi-Dehnayebi, M.; Al-Ghamdi, K.; Abu-Dief, A.M. Synthesis, structural determination, DFT calculation and biological evaluation supported by molecular docking approach of some new complexes incorporating (E)-N’-(3,5-di-tert-butyl-2-hydroxybenzylidene) isonicotino hydrazide ligand. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2024, 39, e7768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwer, K.E.; Hamza, Z.K.; Ramadan, R.M. Synthesis, spectroscopic, DFT calculations, biological activity, SAR, and molecular docking studies of novel bioactive pyridine derivatives. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 15598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zine, Y.; Krid, A.; Boulcina, R.; Harakat, D.; Robert, A.; Bensouici, C.; Debache, A. Synthesis, biological evaluation, DFT calculations and molecular docking of 5-arylidene-thiazolidine-2,4-dione derivatives. Polycycl. Aromat. Compd. 2023, 44, 4784–4807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agwupuye, J.A.; Gber, T.E.; Edet, H.O.; Zeeshan, M.; Batool, S.; Duke, O.E.E.; Adah, P.O.; Odey, J.O.; Egbung, G.E. Molecular modeling, DFT studies and biological evaluation of methyl 2,8-dichloro-1,2-dihydroquinoline-3-carboxylate. Chem. Phys. Impact 2023, 6, 100146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, J.; Tareq, A.M.; Hossain, M.M.; Sakib, S.A.; Islam, M.N.; Ali, M.H.; Uddin, A.B.M.N.; Hoque, M.; Nasrin, M.S.; Emran, T.B.; et al. Biological evaluation, DFT calculations and molecular docking studies on the antidepressant and cytotoxicity activities of Cycas pectinata Buch.-Ham. compounds. Pharmaceuticals 2020, 13, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M.A.; Badran, A.; Attai, M.M.A.; El-Gohary, N.M.; Hussain, Z.; Farouk, O. Synthesis, structural characterization, Fukui functions, DFT calculations, molecular docking and biological efficiency of some novel heterocyclic systems. J. Mol. Struct. 2024, 1314, 138815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreño, A.; Páez-Hernández, D.; Cantero-López, P.; Zúñiga, C.; Nevermann, J.; Ramírez-Osorio, A.; Gacitúa, M.; Oyarzún, P.; Sáez-Cortez, F.; Polanco, R.; et al. Structural characterization, DFT calculation, NCI, scan-rate analysis and antifungal activity against Botrytis cinerea of (E)-2-{[(2-aminopyridin-2-yl)imino]-methyl}-4,6-di-tert-butylphenol (pyridine Schiff base). Molecules 2020, 25, 2741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G.M. A short history of SHELX. Acta Crystallogr. A 2008, 64, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G.M. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystallogr. C 2015, 71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrugia, L.J. ORTEP-3 for Windows—A version of ORTEP-III with a graphical user interface (GUI). J. Appl. Crystallogr. 1997, 30, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putz, H.; Barndenburg, K. Diamond—Crystal and Molecular Structure Visualization; Crystal Impact: Bonn, Germany, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- CLSI. Susceptibility Testing of Mycobacteria, Nocardia spp. and Other Aerobic Actinomycetes, 3rd ed.; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI): Wayne, PA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Siqueira, F.D.; Rossi, G.G.; Machado, A.K.; Alves, C.F.S.; Flores, V.C.; Somavilla, V.D.; Agertt, V.A.; Siqueira, J.D.; Dias, R.S.; Copetti, P.M.; et al. Sulfamethoxazole derivatives complexed with metals: A new alternative against biofilms of rapidly growing mycobacteria. Biofouling 2018, 34, 893–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guterres, K.B.; Rossi, G.G.; Menezes, L.B.; Campos, M.M.; Iglesias, B.A. Preliminary evaluation of the positively and negatively charge effects of tetra-substituted porphyrins on photoinactivation of rapidly growing mycobacteria. Tuberculosis 2019, 117, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, G.G.; Guterres, K.B.; Silveira, C.H.; Moreira, K.S.; Burgo, T.A.L.; Iglesias, B.A.; Campos, M.M.A. Peripheral tetra-cationic Pt(II) porphyrins photo-inactivating rapidly growing mycobacteria: First application in mycobacteriology. Microb. Pathog. 2020, 148, 144–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, V.C.; Siqueira, F.D.; Mizdal, C.R.; Bonez, P.C.; Agertt, V.A.; Stefanello, S.T.; Rossi, G.G.; Campos, M.M.A. Antibiofilm effect of antimicrobials used in the therapy of mycobacteriosis. Microb. Pathog. 2016, 99, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Petersson, G.A.; Nakatsuji, H.; et al. Gaussian 09, Revision C.01.; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Glendening, E.D.; Landis, C.R.; Weinhold, F. NBO 6.0: Natural Bond Orbital Analysis Program. J. Comput. Chem. 2013, 34, 1429–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.; Chen, F. Multiwfn: A multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 2012, 33, 580–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T. A comprehensive electron wavefunction analysis toolbox for chemists, Multiwfn. J. Chem. Phys. 2024, 161, 082503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Márquez, J.; Zorrilla, D.; Sánchez-Coronilla, A.; de los Santos, D.M.; Navas, J.; Fernández-Lorenzo, C.; Alcántara, R.; Martín-Calleja, J. Introducing UCA-FUKUI software: Reactivity-index calculations. J. Mol. Model. 2014, 20, 2492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chemcraft—Graphical Software for Visualization of Quantum Chemistry Computations, Version 1.8, Build 682. Available online: https://www.chemcraftprog.com/ (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Parr, R.G.; Yang, W. Density functional approach to the frontier-electron theory of chemical reactivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1984, 106, 4049–4050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Parr, R.G. Hardness, softness, and the Fukui function in the electronic theory of metals and catalysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1985, 82, 6723–6726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, E.R.; Keinan, S.; Mori-Sánchez, P.; Contreras-García, J.; Cohen, A.J.; Yang, W. Revealing noncovalent interactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 6498–6506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras-García, J.; Yang, W.; Johnson, E.R. Analysis of hydrogen-bond interaction potentials from the electron density: Integration of noncovalent interaction regions. J. Phys. Chem. A 2011, 115, 12983–12990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babaoglu, K.; Qi, J.; Lee, R.E.; White, S.W. Crystal Structure of 7,8-Dihydropteroate Synthase from Bacillus anthracis. Structure 2004, 12, 1705–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilangovan, A.; Fletcher, M.; Rampioni, G.; Pustelny, C.; Rumbaugh, K.; Heeb, S.; Cámara, M.; Truman, A.; Chhabra, S.R.; Emsley, J.; et al. Structural Basis for Native Agonist and Synthetic Inhibitor Recognition by the Pseudomonas aeruginosa Quorum Sensing Regulator PqsR (MvfR). PLoS Pathog. 2013, 9, e1003508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siqueira, F.D.S.; Siqueira, J.D.; Denardi, L.B.; Moreira, K.S.; Burgo, T.A.L.; Marques, L.L.; Machado, A.K.; Davidson, C.B.; Chaves, O.A.; Campos, M.M.A.; et al. Antibacterial, antifungal, and anti-biofilm effects of sulfamethoxazole-complexes against pulmonary infection agents. Microb. Pathog. 2023, 175, 105960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adasme, M.F.; Linnemann, K.L.; Bolz, S.N.; Kaiser, F.; Salentin, S.; Haupt, V.J.; Schroeder, M. PLIP 2021: Expanding the scope of the protein-ligand interaction profiler to DNA and RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, W530–W534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flakus, H.T. On the vibrational transition selection rules for the centrosymmetric hydrogen-bonded dimeric systems. J. Mol. Struct. Theochem 1989, 187, 35–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flakus, H.T.; Machelska, A. ‘Long-range’ isotopic H/D effects in the infrared spectra of the centrosymmetric dimeric systems of hydrogen bonds. J. Mol. Struct. 1998, 447, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clegg, R.S.; Reed, S.M.; Hutchison, J.E. Self-assembled monolayers stabilized by three-dimensional networks of hydrogen bonds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998, 120, 2486–2487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simón, L.; Goodman, J.M. Enzyme catalysis by hydrogen bonds: The balance between transition state binding and substrate binding in oxyanion holes. J. Org. Chem. 2010, 75, 1831–1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]