Abstract

Resistance training (RT) influences endocrine pathways that control skeletal muscle (SM) growth. This review summarizes 25 years of evidence (January 2000–December 2025) from PubMed, Medline, and ScienceDirect, focusing on three aspects: (1) exercise types such as RT, speed, power, high-intensity interval training, and aerobic training at various intensities; (2) dietary factors, including caloric restriction, total protein, protein sources, amino acids, and carbohydrates; and (3) aging-related physiological factors that may impair the insulin/IGF-1 axis in SM, such as insulin resistance, fat infiltration, physical inactivity, mitochondrial dysfunction, and inflammation. The data from Grade A evidence in systematic reviews and RCTs are prioritized to develop practical recommendations and future research directions for young, middle-aged, older, and very old individuals. Evidence regarding the effects of anabolic amino acids in women, middle-aged, and very old individuals, as well as locally mediated IGF-1 effects of any type of exercise, is limited.

1. Introduction

Skeletal muscle (SM), its functional properties, and its anabolic stimuli are solidly regulated by lifestyle (diet and exercise) and endocrine factors such as Insulin Growth Factor-1 (IGF-1) and insulin, tightly interconnected proteins. IGF-1, a hormone primarily produced in the liver, acts as a mediator of the anabolic actions of GH in SM and is part of the myokines that play a role in metabolic homeostasis and muscle growth and repair [1]. IGF-1 regulates anti-myogenic factors, such as myostatin (MSTN), and plays a major role in repairing muscle tissue following injury or intense physical training [2]. IGF-1 activates signaling pathways of SM control by promoting its development through the activation of the mammalian target of the rapamycin pathway (mTOR) [3]. In fact, when IGF-1 levels increase, it induces a rapid preparation for protein synthesis [4]. IGF-1 acts alone and is coupled with insulin through the INS/IGF-1-Akt-mTOR pathway, an anabolic complex that sustains muscle growth [5]. IGF-1 and insulin are also involved in mitochondrial function, which plays a key role in SM health, particularly during aging [6].

Maintaining anabolic status is essential for preserving the quantity and quality of SM throughout life. Reduced cellular anabolism leads to an imbalance between muscle protein synthesis (MPS) and breakdown (MPB), which can be influenced by exercise and dietary stimuli [7]. Unlike MPS, MPB is less affected by changes in dietary amino acid intake [8]. Typically, older adults experience lower MPS and higher MPB compared to younger individuals in response to protein source, intake amount, and timing [9]. Resistance training (RT) enhances post-meal MPS at any age, whereas endurance training does not. Improving Physical Activity Level (PAL) in seniors boosts MPS. An imbalance between MPS and MPB, along with muscle disuse and inactivity, contributes to sarcopenia, which is associated with both anabolic resistance (AR) [10] and mitochondrial dysfunction [6]. Evidence is limited regarding how Moderate-Intensity Continuous Training (MICT), high-intensity interval training (HIIT), Sprint Interval Training (SIT), caloric restriction, dietary protein sources, essential amino acids (EAA), amino acid supplementation, carbohydrates, and overall health influence hormonal SM response across aging.

2. Methods

2.1. Review Questions

This literature review concerning the effects of exercise and nutrition on the insulin and IGF-1 effect in SM addresses the following questions: (1) What are the acute and chronic effects of different exercise modalities on GH, IGF-1, and IGFBPs? (2) How do caloric restriction (CR), protein dietary sources, amino acids, and carbohydrates affect IGF-1 and insulin in response to exercise? (3) How do lifestyle factors such as fitness, sedentary behavior, physical activity, and dietary factors affect IGF-1 and insulin in SM during physiological aging? (4) How do metabolic disturbances associated with physiological aging affect the IGF-1 and insulin effects on SM?

2.2. Search Strategy and Study Selection

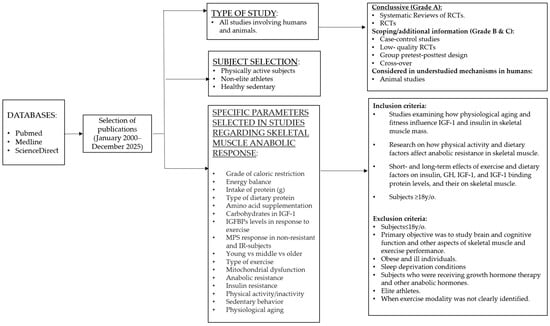

Online databases PubMed, Medline, and ScienceDirect were searched according to the criteria and methodology shown in Figure 1 to identify all relevant studies published between January 2000 and December 2025. The search included the following keywords: “exercise”, “IGF-1”, “growth hormone”, “resistance exercise”, “resistance training”, “endurance exercise”, “aerobic exercise”, “high-intensity exercise”, “speed exercise”, “power exercise”, “physical activity”, “physical inactivity”, “sedentary”, “speed and power exercise”, “caloric restriction”, “energy availability”, “dietary protein”, “plant-based protein supplements”, “animal-based supplements”, “amino acids”, “insulin resistance”, “insulin sensitivity”, “mitochondrial biogenesis”, mitochondrial dysfunction” “anabolic resistance” “aging” “physiological aging”, “healthy aging”, “myosteatosis”, and “fat infiltration”, along with specific exercise types, amino acids, and protein-based supplements with appropriate combinations of operators “AND”, “OR”, and “NOT”. Additional references were identified through analyzing the retrieved publications and the authors’ files. The language of the included studies was restricted to English.

Figure 1.

Flowchart illustrating the methodology for selecting publications.

The studies listed in the tables include pretest–posttest group studies, cross-design, RCTs, and case–control studies conducted in humans. Animal studies were used to describe mechanisms or topics that cannot or have not yet been evaluated in humans. As shown in Figure 1, studies of elite athletes are excluded from the conclusions but are cited throughout this article for illustrative and comparison purposes, i.e., the range of IGF-1 levels.

2.3. Eligibility and Evidence Handling

This primarily clinically oriented review included studies that showed at least one of the following outcomes: changes in circulating IGF-1 levels, GH, or IGFBPs before and after acute or chronic exercise exposition, grade of caloric restriction, protein sources, amino acids with anabolic functions in SM; comparisons between groups subjected to different exercise modalities; or epidemiological or cohort studies analyzing lifestyle risk factors that may influence hormonal SM responses in adults over 18. Animal studies focusing on mechanisms related to lifestyle risk factors or fundamental physiological or molecular processes—particularly those non-/less studied in humans—associated with anabolic SM response were also examined. In instances where studies did not measure IGF-1 levels but instead considered other anabolic hormonal indicators such as testosterone and myostatin, these were regarded as complementary information but not conclusive. Studies included healthy or trained individuals and excluded elite athletes (world-class and professional athletes). When limited information was available, this population was used for illustrative or comparative purposes. Except for a few specified exceptions, only studies that used serum assays were included. The search also encompassed locally mediated effects of IGF-1 and found exceedingly limited evidence. Studies in which it was impossible to identify the exercise modality, or in which information on exercise or dietary protocols was limited, were excluded.

The grades of evidence for this review to classify study selection were as follows: Grade A evidence comprises systematic reviews, meta-analyses of high-quality RCTs, and RCTs used to develop figures and conclusions that synthesize evidence concerning the effect of exercise modality and dietary factors on anabolic response as well as identifying research gaps and suggested actions at the clinical level. Grade B and C evidence consists of low-quality RCTs, systematic reviews with cohort or case–control studies, and individual studies of varying quality, which were included for scoping, contextualization, or complementary information. Grades A to C were used to develop, tables, sections and the figure that synthesizes aging and lifestyle factors linked to a low anabolic SM response. Grade D evidence, including expert opinions, was only used as recommended reading in the Conclusions and Practical Considerations section.

3. Physiological Aging, Skeletal Muscle Function, and the Anabolic Resistance Effect

SM has evident mechanical functions and acts as a dynamic reservoir for metabolism, proteins, heat, and immune regulation [11]. Aging naturally causes anatomical and functional changes in skeletal SM, such as the decline of type II fibers starting around age 25. A noticeable decrease in SM mass occurs near age 30, at a rate of 3 to 8% per decade, which accelerates after age 65–70. While aging affects both muscle structure and function, the loss of muscle quantity is less impactful than reductions in strength and physical performance. Muscle power declines earlier and more quickly with age than strength [12]. Key factors contributing to functional decline include decreased synthesis of myofibrillar proteins, lower ATPase activity of actomyosin, changes in myosin isoform expression, fewer motor units, and loss of satellite cells, which are essential for muscle repair. These alterations disrupt sarcomere signaling and intercellular communication and are influenced by impaired INS/IGF-1 pathways [13].

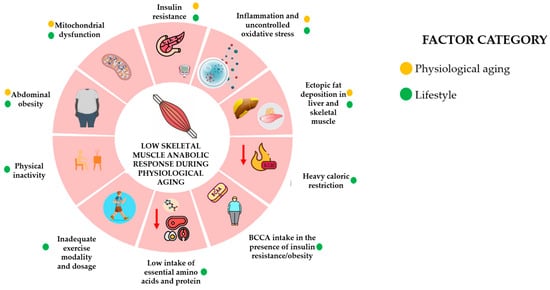

It is now acknowledged that factors like physical inactivity, diet, abdominal fat, and obesity play a significant role in sarcopenia and AR, affecting not just the elderly but also young and middle-aged adults. These factors lead to adverse effects in SM, including insulin resistance (IR) and mitochondrial dysfunction, similar to those observed in older individuals [14,15]. Exercise in the early years offers several advantages; seniors who had exercised for 30 y previously had greater maximal strength, muscle force, and function and preserved muscle fiber size [16]. AR is also heavily affected by muscle loss induced by aging and catabolic-induced stages, such as an increase in oxidative stress, inflammatory cytokines, and glucocorticoids, with the consequent increase in anabolic threshold and decreased anabolic response [17]. Although an age-expected relationship exists between SM protein AR and amino acids, aging itself is not directly linked to AR, and an adequate diet and RT exercise may help maintain proper SM and function. Specifically, sufficient RT exercise enhances MPS sensitivity, promoting a hypertrophy response [18]. Figure 2 depicts the lifestyle and physiological factors identified in low response to SM anabolic stimuli, which are further discussed in this review. They are presented in no particular order because they are more interconnected than sequential. For example, physical inactivity increases the risk of abdominal obesity, which in turn is associated with IR, inflammation, and ectopic fat deposition.

Figure 2.

Factors associated with low skeletal muscle anabolic response during physiological aging. The lifestyle factors influencing the anabolic response of skeletal muscle mass during physiological aging include mitochondrial dysfunction, insulin resistance, inflammation, abdominal obesity, ectopic fat deposition, physical inactivity, exercise modality and dosage, heavy caloric restriction, amino acid, protein intake, and branched-chain amino acid intake. The first five factors are typically expected with physiological aging. This Figure is an original work from the author.

4. Effect of Physiological Aging on Anabolic Changes in Skeletal Muscle

The estimated heritability range of IGF-1 levels is from 40 to 63% and is influenced by GH levels, obesity, age, sex, sports training, physical activity, and nutritional status [19]. The GH/IGF-1 axis plays a vital role in somatic growth and development. After birth, growth hormone (GH) and IGF-1 levels increase gradually, reaching their peak between 15–17 y/o in both males and females. Once skeletal maturation is integrated, SM homeostasis is sustained through hypertrophy and atrophy. Hypertrophy and regeneration are primarily regulated by a signaling pathway induced by IGF-1 [20]. After 20 years, IGF-1 levels show a steady decline throughout adulthood, dropping to nearly 50% or less of their peak levels by age 70 [21]. Reduced IGF-1 signaling is a key endocrine factor associated with the loss of SM during aging [22]. Aging-related inflammation contributes to GH resistance, leading to decreased circulating IGF-1 levels and synthesis [23]. Nonetheless, it is hypothesized that the decrease in the GH/IGF-1 axis during somatopause serves as a natural mechanism to help conserve the aging human individual [24].

Exercise stimuli increase IGF-1 levels in the young, middle-aged, and elderly. The level of fitness is positively correlated with plasma IGF-1. Peak GH levels are higher in elite male and female athletes than in physically active and sedentary individuals. Higher levels of physical activity stimulate GH pulsatility and, consequently, IGF-1 levels. The increase in IGF-1 bioactivity in fitter subjects is related to changes in IGF-1 circulating and its binding proteins (IGFBPs) [25]. IGF-1 basal levels are higher in Olympic, young elite, and college athletes than in healthy subjects, ranging from 300 to 450 ng/dL or higher [26,27]. Consistent with findings in younger athletes, basal IGF-1 levels in master athletes are higher than those of their sedentary counterparts [28]. The systematic training appears to affect the IGF-1 levels in active middle-aged and older physically active individuals, with the fittest individuals exhibiting higher irisin and IGF-1 levels and lower insulin and homeostasis model assessment-estimated IR (HOMA-IR) levels [29]. The latest findings coincide with large-cohort data, where the fittest non-diabetic individuals who maintain physical activity in the health-enhancing range (3000 MET min/w) had lower HOMA-IR and slowed the progression of IR [30].

Even in healthier individuals, biological aging directly affects the SM and liver, key tissues in insulin and glucose regulation. Cross-sectional studies show that aging impairs the conversion of proinsulin to insulin, which indicates ß-cell function. Regardless of a peak around 30 years for men and 50 years for women, the proinsulin ratio tends to rise with age, though insulin levels do not show a similar clear increase [31]. RCTs and epidemiological studies showed a combined effect of age and lifestyle factors on insulin sensitivity (IS). IS seems to be persistent after adjusting for metabolic risk factors such as high body mass index, waist circumference, triglycerides, blood pressure, and hemoglobin glycosylated (HbA1c) [32]. Still, telomere length, a proposed longevity biomarker, is also not associated with IR, suggesting that cellular aging and IR are heavily influenced by lifestyle factors, such as metabolic risk factors (e.g., abdominal adiposity) [33,34].

In healthy individuals, insulin inhibits lipolysis in adipose tissue and promotes glucose uptake in SM after glucose intake. A decrease in plasma insulin levels increases glucose oxidation, while an increase promotes glycogen storage in SM. SM accounts for about 80% of postprandial glucose uptake from the bloodstream [35]. The liver plays a crucial role in maintaining whole-body homeostasis and regulates systemic energy metabolism through hepatic glucose and insulin signaling. Impairments in insulin action and sensitivity in insulin-target tissues like the liver and SM lead to IR [36,37]. Despite reductions in fat-free mass (FFM) and increased visceral and intra-organ fat, a true age-related metabolic defect is linked to mitochondrial dysregulation. Mitochondrial damage causes energy shortages and disrupts ROS production, harming mitochondrial DNA and other cell components [38]. As we age, energy expenditure declines, and oxidative capacity diminishes in energy-dependent tissues, especially the SM and the heart. Nonetheless, independent of aging, excess caloric intake and low physical activity severely impair mitochondrial function and energetics by disrupting the electron chemical gradient, resulting in insulin dysfunction [39]. In male subjects between 18 and 50 y/o, low IGF-1 levels are associated with reduced insulin secretion and enhanced fat metabolism during fasting, resulting in abnormal glucose response after excessive nutrient load [40].

Older people exhibit lower SM insulin-stimulated Akt activity, insulin signaling, and the consequent decrease in SM. The interactions among mitochondrial dysfunction, inflammation, oxidative stress, changes in enzyme activity, sarcopenia, reduced autophagy, and excessive activation of the renin–angiotensin system contribute to glucose metabolic alterations in SM [41]. Evidence has also shown that aging diminishes the capacity of adipose tissue to counteract its own lipotoxicity, causing myogenic cells to become lipogenic [42]. As we age, hypertrophy and hyperplasia of lipid droplets in intra- and intermuscular regions, especially within type II fibers, contribute to IR, sarcopenia, age-related changes, and muscle dysfunction [43]. Inflammatory cytokines and fat infiltration in SM are linked to the failure to suppress FOXO1 and the upregulation of the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway. This, in turn, decreases protein activation in the mTOR pathway, reducing SM protein synthesis due to inhibition of the IGF-1/PI3K/AKT pathway, ultimately leading to AR and muscle atrophy [44,45].

Fat infiltration and inflammation also affect the liver, leading to a decline in liver function and circulating IGF-1, decreasing regenerative capacity and increasing the risk of diseases such as IR, vascular diseases, and sarcopenia [46]. Besides IGF-1, the liver also produces IGFBPs. In chronic liver disease, IGFBP-1, IGF-1, and ALS increase, whereas IGFBP-3 decreases, thereby limiting circulating IGF-1 [47].

5. Effect of Insulin, IGF-1, and IGFBPS on the Anabolic Response of Skeletal Muscle

IGF-1 binds its receptor, activating the PI(3)K/Akt/mTOR pathway, which aids myoblast differentiation from satellite cells that provide nuclei for growth. mTOR promotes SM hypertrophy and homeostasis by regulating satellite cell activity and myogenesis [48]. SM hypertrophy requires a change in protein turnover. MPS is influenced by contractile activity type, duration, volume, frequency, dietary intake, and individual responses [49]. While the liver is the primary producer of IGF-1, myocytes can produce it locally, which is crucial to maintaining SM in aging [50]. The mature IGF-1 peptide mediates IGF-1 in the SM, but its short half-life requires stabilization by six IGF-1 binding proteins (IGFBPs). IGFBPs 3, 4, 5, and 6 coordinate IGF-1 bioavailability in SM. IGFBP 3, the most abundant in the bloodstream, forms a ternary complex with the acid-labile subunit (ALS) and IGF-1, prolonging the half-life. IGFBP4 inhibits IGF-1 action, IGFBP5 is the major protein secreted from SM, and IGFBP6 inhibits IGF-2. IGF-1 interacts with IGF-1/Akt and IGF-1/MGF/ERK pathways, which connect to regulators of SM like MSTN and the GPCR family, a complementary process in SM regeneration [51].

Mitochondria play a crucial role in SM regulation. Oxidative phosphorylation-active myotubes primarily arise from glycolytic myoblasts during myogenesis, thereby establishing a new mitochondrial network. Stimulating mitochondrial biogenesis promotes myogenesis and repairs atrophying muscles. Mitophagy removes damaged mitochondria, crucial for myogenic differentiation. IGF-1 activates PGC-1ɑ and BNIP3, which are essential for mitochondrial biogenesis, mitophagy, and atrophy reduction [52]. PGC-1 is also a mediator of insulin signaling, mitochondrial biogenesis, and SM [53]. Insulin and IGF-1 stimulate glucose and amino acid uptake in SM, promoting a net positive protein balance by upregulating protein synthesis [54]. Insulin stimulates hepatic IGF-1 production even without GH through IGF-1 binding proteins. The INS/IGF-1-Akt-mTOR pathway regulates protein synthesis, degradation, cellular proliferation, survival, glucose uptake, and energy production. INS/IGF-1 signaling affects a key hub for protein synthesis and degradation. mTOR inhibits protein breakdown by blocking autophagy via ULK1 [55].

6. Effects of Exercise on the Anabolic Response in Skeletal Muscle

Exercise is the most potent stimulus for GH release and SM growth, and GH partly regulates anabolic effects through its conversion to IGF-1 [56]. Recent evidence shows that changes in systemic IGF-1 activity have a lower direct impact on intramuscular anabolic signaling, and hypertrophic adaptations induced by RT training programs are locally mediated [57]. Since most research has measured circulating proteins to assess the effects of exercise on the GH–IGF-1 axis, the acute and chronic effects of exercise on circulating levels of insulin, IGF-1, and their binding proteins are summarized in the tables below.

6.1. Acute Exercise: RT/HIIT/SIT—Aerobic at Different Intensities

SM mainly utilizes fatty acids during resting and carbohydrates, fatty acids, ketones, and carbon skeletons during physical activity and exercise in an intensity- and time-dependent manner [58]. The fractional synthetic rate of protein synthesis is blunted in working SM, and the anabolic process occurs mainly after exercise [59]. The increase in GH release after exercise is affected by metabolic and physiological aspects such as blood lactate levels, pH, adrenergic, and cholinergic mechanisms. GH-binding protein (GHBP), total IGF-1, IGFBP-2, and acid-labile subunit (ALS) increase during exercise, while IGFBF-1 increases after exercise. Free IGF-1 does not appear to change during or following exercise. The increase in IGF-1 might enhance post-exercise reparative processes [60]. In general, there is a linear increase between GH secretion and exercise intensity or RT, but it might vary. For example, the acute increase in IGF-1 after the RT bout is less pronounced in middle-aged men (~49 y/o) than in younger men (~21 y/o). At the same time, the testosterone response remains similar regardless of age [61]. The intensity of aerobic exercise does not affect the activation of AMPK and mTOR signaling after RT [62]. In the systematic review and meta-analysis by De Alcantara et al. (2020) [63], RT influenced total IGF-1 levels but not free IGF-1. The type of exercise (endurance vs. RT) affects IGF-1, although the underlying mechanisms remain poorly understood. Older and untrained subjects exhibited dysregulated and exaggerated IGF-1 signaling that may reflect an incomplete compensatory cellular response to counteract age-related AR. In older subjects, IGFBP4 increases at 24 and 48 h in an attempt to compensate for the AR and IGF-1 expression [64]. Case–control and experimental studies describing the acute effects of exercise on GH, IGF-1, and their binding proteins are presented in Table 1 and Table 2.

Table 1.

Case–control studies showing hormonal responses (IGF-1/IGFBPs/insulin) by exercise modality.

Table 2.

Studies showing acute hormonal responses (IGF-1/IGFBPs/insulin) by exercise modality.

6.2. Chronic Effects of Exercise: RT/HIIT/SIT—Aerobic at Different Intensities

Naturally released peptide and protein hormones, such as GH and IGF-1, increased after RT. Compared to stretching, after 10 w only in the moderate RT (8 to 10 RM), IGF-1 basal levels increased in adults from 25 to 35 y/o with a balanced diet in macronutrients [75]. Also, RT reduction from three to two sessions/w seems to maintain IGF-1 levels but not testosterone in community-dwelling women [76]. The systematic review and meta-analysis of Jiang et al., 2020 [77], which included a large number of RCTs, showed that RT protocols increased IGF-1 levels, but the effect was strongly significant only in women, subjects of both sexes ≥ 60 y/o, and RT protocols lasting ≤ 16 w. RT-induced hormonal elevations on long-term muscle hypertrophy are not fully clear. Acute hormonal responses indicate the intensity and subsequent metabolic stress of a specific RT protocol, whereas the long-term hypertrophic adaptation depends on different factors [78]. Evidence from RCTs and reviews has also shown a non-conclusive effect of RT mitochondrial biogenesis, content, and respiratory capacity [79,80].

HIIT and SIT protocols effectively improve cardiometabolic health and oxidative mechanisms in SM. HIIT induces greater activation of type II muscle fibers with the most significant potential for hypertrophy after RT. SIT increases the expression of myogenic differentiation genes such as MYOD1. In contrast, HIIT increases force-gene generation genes such as CARNS1 and MYLK4, and both seem to downregulate MSTN but not increase satellite cell content [10]. In young female healthy sedentary subjects, 12 w of increased HIIT and HIIT + physical activity (measured as step count) increased the IGF-1 salivary concentration [81]. A case–control study has shown that salivary IGF-1 and serum IGF-1 correlate in females [82]. Studies describing the chronic effects of exercise (2 w to 32 w) on IGF-1 are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Studies showing chronic hormonal responses (IGF-1/IGFBPs/insulin) by exercise modality.

6.3. Effects of Exercise on Insulin Function

There is strong evidence that aerobic exercise and/or physical activity that meets the recommendations of exercising for at least 30 min on 3–5 d/w helps to improve IS and glycemic control [97]. The benefits of IS of exercise programs such as HIIT and MICT in IS are seen with or without improvements in parameters of aerobic fitness (VO2max and VO2peak) and can be augmented by a greater volume of exercise intensity stimuli. In any situation, individuals with higher cardiorespiratory fitness had better glycemic control. Jiahao et al. (2021) [98] reviewed that healthy older adults who engaged in high-intensity RT for at least 12 w demonstrated improved IS, whereas individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus exhibited variable results. The benefits of exercise in improving IS are independent of weight loss and more effective than dietary changes alone, although proper dietary and nutritional adjustments can further enhance these benefits [99,100].

One of the quality parameters of SM related to IS is the amount of intramuscular, intermuscular, and intramyocellular fat. In individuals who are lean, endurance-trained, obese, or have T2DM, the intramyocellular fat is deleterious for IS. [101]. In non-obese non-athlete men, high physical activity was higher in the high VO2peak/high-intramyocelular lipids group than in low VO2/peak low VO2, VO2/peak low VO2, and high VO2/peak low VO2 groups. Fitness seems to be a better parameter for predicting IS, regardless of fat storage, such as IMCL level [102]. In the review of Zouhal et al. (2022) [103], it is reported that the effect of exercise protocols lasted from 2 to 52 w in healthy sedentary men and women aged 40 to 85. IGF-1 and GH levels increased independently of the type of exercise, whilst insulin levels changed inconsistently. The exercise modalities included were HIIT and RT, aerobic exercise at different intensities, and low-impact exercises. Overall, regular, adequate exercise enhances IS, promotes mitochondrial biogenesis, and increases IGF-1, which is crucial for sustaining healthy SM.

7. Effects of Dietary Factors on the Anabolic Response in Skeletal Muscle

It is known that energy balance and the direct stimulation of anabolic-effect nutrients contained in food, such as cow milk and dietary protein, on IGF-1 and insulin are proven in postnatal life growth and lean mass accretion [104]. During adult life, the anabolic effects of diet, IGF-1, and insulin are seen in healthy adults with anabolic-stimuli variations. On the other hand, moderate and long-term energy deficits induce a catabolic state that affects protein turnover. In fact, in trained females and healthy male subjects, energy deficit negatively impacts anabolic hormones and reduces myofibrillar and sarcoplasmic MPS [105,106]. Hereby, it is further reviewed how CR, protein sources, amino acids, and carbohydrates impact the endocrine anabolic response to exercise during healthy aging.

7.1. Caloric Restriction and Protein Intake

At the molecular level, CR-induced suppression of mTOR plays a key role in promoting longevity. In animal studies, neither age nor CR significantly changed total mTOR levels. CR appears to affect phosphorylated mTOR in middle-aged rats, but not in the muscles of young and adult animals, indicating that CR’s impact on mTOR signaling and the UPP in SM is age-dependent [107]. Sharples et al. (2015) [108] explained that long-term CR and dietary restriction reduce skeletal muscle mass (SM), shifting the body from growth to survival mode. One hypothesis proposes that in older animals, IGF-1 declines due to increased SIRT1, which negatively regulates IGF-1 and is downstream of Akt/mTOR, as a survival mechanism. The resulting increase in SIRTs in response to nutrient shortages, such as reduced protein intake, may adversely affect mTOR function and impair regenerative processes. For example, short-term CR in rodents’ hindlimb muscles caused delayed contractile relaxation, likely due to loss of fast-twitch fibers and abnormal expression of transcription factors that regulate slow versus fast muscle phenotypes [109].

The short- and long-term negative effects of repair and regenerative mechanisms during CR are quickly reversed once refeeding occurs in humans and rodents [110]. Besides the mechanism linked to mTOR, short CR appears to enhance SM function and quality through other pathways, such as the activation of CR-induced somatic maintenance genes, which are beyond the scope of this review.

Research in humans demonstrated that energy balance and dietary protein influence whole-body and SM protein metabolism, contributing to the control of SM. MPS, a primary regulator of SM, is highly stimulated by dietary protein and controlled energy surplus. Protein and carbohydrate timing facilitate chronic SM hypertrophy adaptations to RT [111]. The ingesting protein at a rate of 1.6 to 2.4 g/kg or consuming meals containing AP (15–30 g) can potentially contribute to alleviating the decrease in MPS and intracellular proteolysis induced by minor deficits in light CR [112]. Increasing protein intake helps maintain FFM and nitrogen retention when CR results in ≥25% weight loss. In general, the increase in dietary protein intake from 50% to 100% above the RDA may counteract the nitrogen losses resulting from diet, exercise, or both [113].

CR effects on the GH–IGF-1 axis appear to vary based on the amount of CR, diet profile, exposure duration, and exercise type. Moderate caloric restriction (~30%) of the initial intake during a short-term fasting period (four w of Ramadan fasting) resulted in a decrease in GH at the first w, an increase in IGFBP-3 at the fourth, and no observable effect on post-submaximal exercise IGF-1 levels [114]. Compared to a Western diet, balanced moderate CR in weight-stable middle-aged individuals triggers transcriptional reprogramming that favors maintenance and repair activities by downregulating the IGF-1/INS/FOXO pathway and enhancing mitochondrial biogenesis through PGC-1α expression. These changes can slow the transcriptional shifts associated with aging in SM [115].

Under certain circumstances, fasting—similar to the acute phase of inflammation—raises GH levels but induces GH resistance in the liver, reducing circulating IGF-1 levels [22]. In fact, CR induces AR to RT. Weight loss decreases MPS and increases MPB. CR affects anabolic hormones and disrupts the GH–IGF-1 axis mainly by decreasing the effect of GH on IGF-1 and the suppression of the hypertrophic PGC1α-4/IGF-1/AKT1 pathway, leading to a decrease in SM fibers in rodent models [116]. In young subjects, 3 days of CR at 15 cal/FFM induce AR after a high-intensity bout of RT whilst consuming 1.2 g/P/kg, and it continues after post-exercise supplementation with protein or carbohydrates. The AR occurs even after a post-exercise peak of GH, but the IGF-1 response is low, showing that CR seems to limit the effectiveness of RT [117].

In a systematic review by Rahmani et al. (2019) [118], involving subjects with a CR restriction (≥50%) leads to a significant decrease in IGF-1 levels. Conversely, during heavy CR (≥40%), combining a high-protein diet with RT can help maintain MPS [119]. In the review by Ardavani et al. (2021) [120], there is contradictory evidence regarding SM retention during low- and very-low-calorie diets when adding aerobic, high-intensity, or RT in healthy adults. In a small sample (n = 90) of non-obese, middle-aged men and women, two years of very conservative CR (12%) positively influenced SM gene expression related to mitochondrial biogenesis through the SIRT pathway, as well as proteostasis, inflammation, and cellular turnover. No changes in peak torque during knee extension were observed due to CR. Data on IGF-1 levels, MPS, health status, or physical activity were not included [121]. There is still limited information regarding changes in SM in healthy individuals exposed to long-term low-energy diets (≥6 months).

Low energy availability refers to an athlete’s inadequate energy intake relative to their lean body mass, which is necessary for vital physiological functions. This occurs when exercise demands are high and serves as an illustrative example of the long-term effects of diminished energy intake. Prolonged and heavy energy imbalance, not associated with illness, has been studied among athletes during periods of low energy availability or during overtraining syndrome (OTS), characterized by a proinflammatory profile and physiological fatigue, including low production of anabolic hormones such as testosterone and IGF-1. During this physiological state, basal levels of hormones are not always negatively affected, but the anabolic and GH response to an acute bout of training is blunted [122,123]. For instance, among national-level Finnish athletes, a prolonged recovery from OTS lasting one year was associated with low resting leptin levels and a poor response to a maximal exercise test, accompanied by a pro-inflammatory profile characterized by elevated levels of IL-6, IL-1ß, and TNF-ɑ and a reduction in IGF-1 levels following maximal exercise at 6 and 12 months [124]. In contrast, nutritional shorter changes along seasons could affect anabolic and catabolic physiological profiles in athletes (i.e., rhythmic gymnasts, wrestlers, swimmers, and volleyball players) without detriment to the training and competition performance [25,125,126].

7.2. Dietary Protein, Protein Supplements, and Amino Acids

7.2.1. Animal Protein and Animal Protein-Based Dietary Supplements

In any situation, the effect of protein or amino acid supplementation on IGF-1/mTOR/Akt pathways in SM is attenuated or enhanced by dietary modifications [127]. The review by Tezze et al. (2023) [128] shows that high-quality whey protein, combined with RT exercise in young adults, exerts a more significant effect on MPS than the same doses of lower-quality proteins. The lowest doses of AP, such as egg and beef, and supplemented proteins, including whey, casein, milk, and soy, that stimulate MPS ranged from 5 to 20 g, up to a maximum between 20 g and 45 g in a single intake session, whilst 170 g of beef induces greater MPS than quantities less than or equal to 150 g. High-quality proteins such as whey or egg proteins are sufficient to maximize the postabsorptive rates of myofibrillar MPS in resting conditions over 4 h. In young volunteers, 20 g stimulated MPS in SM during the postabsorptive state at rest. A study on middle-aged women found that, in resting conditions, 23 g of both complete and incomplete proteins equally stimulate MPS regardless of their amino acid profile [129]. Other factors, such as the rate of protein digestion, may influence MPS. For instance, in young adults, rapidly digested proteins (such as whey) promote amino acid oxidation and protein synthesis, whereas slowly digested proteins (such as caseins) significantly inhibit proteolysis, resulting in an overall enhancement of protein anabolic effects [130].

Circulating IGF-1 is generally more influenced by exercise than by protein ingestion. High protein intake does not appear to increase IGF-1 levels acutely, but after 24 h, this increase may be reduced with the addition of exercise [131]. Likewise, myokines that inhibit IGF-1 action, such as MSTN, increase atrophy-related genes, induce muscle wasting, and suppress SM hypertrophy during aging seem to be highly affected and modulated by exercise than dietary protein and protein-derived supplements. AP, like whole milk, combined with a high-protein diet, can produce only a long-term effect; eggs may reduce MSTN, but with a negligible clinical impact, whereas whey protein does not influence MSTN. Bovine colostrum is high in leucine and growth factors [132], but evidence regarding its effects on IGF-1 levels is contradictory among athletes [133], not well supported in healthy male subjects [134], and not superior to RT in older adults [135].

7.2.2. Plant Dietary Protein and Plant-Based Supplements

Research on diet-based or supplemented soy protein in healthy groups regarding IGF-1 and its binding proteins is limited. Available evidence indicates that 40 g of isolated soy protein, which represents a substantial daily soy protein intake even among vegan populations, increases IGF-1 and IGFBP-3 levels [136]. This is consistent with the meta-analysis of Zeng et al. (2020) [137,138], where in healthy middle-aged men and postmenopausal women, dosages of 50 and 25 g of soy protein had no strong increase in IGF-1 levels. This effect on IGF-1 is observed in unhealthy individuals and decreases in interventions longer than 12 w. When matched for leucine content, soy protein induces the same extent of MPS as whey protein in young males and females [139].

Novel plant-based protein supplements such as Vicia Faba peptide network seem to induce the same positive effects of milk proteins on muscle size after immobilization [140] and induce an acute increase in promyogenic factors such as irisin and a decrease in atrophic factors such as MSTN after exercise [141]. Nevertheless, the supplementation with 0.33 mg/kg of Vicia Faba did not enhance resting or post-exercise myofibrillar protein synthesis in recreationally young men, whilst RT did [142]. The effects of this novel supplement on older adults, women, and IGF-1 remain unknown. It is important to note that consuming a combination of plant proteins or leucine-enriched options can produce similar effects to AP when taken in the same amount by young men and women [143].

7.2.3. Anabolic Amino Acids

BCAAs are highly oxidized in SM during fasting and exercise in an intensity-dependent manner. Whole-body leucine oxidation is higher following exercise compared to during rest, and leucine oxidation is elevated in fasting states relative to post-absorptive states. In the fed state, leucine and isoleucine contribute to increased insulin secretion [144,145]. The effect of BCAA in IGF-1 is seen when co-ingested with carbohydrates independently of an acute RT bout. The anabolic effect of leucine alone is observed only when EAA are present, as a sustained increase in MPS requires their availability [146]. In healthy individuals, most evidence does not support the notion that BCAA or leucine supplementation improves strength or hypertrophy. These nutrients appear to induce an anabolic effect in SM only under conditions such as sarcopenia and menopause, but the evidence remains inconclusive [147,148]. Excess BCAA may impair IS via the mTORC1/S6K1 signaling pathway. In individuals with excess body fat mass and under some metabolic conditions, BCAA might induce SM lipid accumulation and hepatic lipogenesis, contributing to IR [149]. In the critical review by Supruniuk et al. (2023) [150], it is detailed that excessive accumulation of BCAA is a well-established metabolic feature associated with obesity and an early risk factor for IR, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, and T2DM. Therefore, increasing BCAA levels through dietary supplementation to boost IGF-1 for enhancing MPS and SM regeneration should be tailored to the individual dietary needs of healthy subjects, but not for those with metabolic risk.

The anabolic effect of EAA on SM is another dietary factor that has been studied. A low-EAA diet reduces serum EAA concentrations, thereby affecting IGF-1 and IGFBP-1 transcription in the liver and lowering circulating IGF-1 levels. Studies in mammals show that dietary EAA intake is not the sole factor for growth but is crucial as an IGF-1-tropic signal for the proper maintenance of the GH/IGF-1 axis and for facilitating IGF-1 action [151]. Little is known concerning the effect of EAA supplementation in healthy humans. In the RCT of Dillon et al. (2009) [152] conducted in older women (68 ± 2 y/o), the chronic intake of 15 g of EAA increases lean body mass, FSR, and IGF-1 protein expression in SM. In the review of Ispoglou (2020) [153], long-term EAA supplementation in healthy older adults was found to be able to help meet protein needs but does not provide extra benefits for strength, lean body mass, or functional improvements.

Especially in women, limited available evidence has shown that creatine supplementation increases the phosphorylation states of the Akt/mTOR signaling pathway and directly enhances muscle differentiation via the upregulation of MRF activities, which, in turn, may enhance the intramuscular IGF-1 content and modulate MSTN [154]. In young male RT novices, supplementation with 0.03 g/kg of either hydrochloride creatine or monohydrate creatine after 8 w of RT training at 75–80% intensity had positive hormonal anabolic stimuli such as the increase in GH, IGF-1, testosterone/cortisol ratio, and follistatin/myostatin ratio in addition to SM and cross-sectional appendicular SM areas [155]. Nevertheless, there is no evidence of the effect of creatine supplementation on IGF-1 increase or satellite cell expression in older men (≥55 y/o) after 6–12 w of RT training [156].

Arginine is another amino acid that may influence the GH–IGF-1 axis activity in humans. An RCT performed in regular strength-trained athletes showed that the supplementation with 2200 mg of L-ornithine, 3000 mg of L-Arginine, and 12 mg of vitamin B12 enhanced the increase in GH and IGF-1 after 3 w of RT [157]. A systematic review and meta-analysis by Nejati et al. (2023) [158] found no significant benefits of arginine supplementation on IGF-1 levels in either acute or chronic cases. However, two major limitations are that the studies did not report baseline arginine levels, and the fitness levels of the subjects were not specified.

7.3. Carbohydrates

Oral glucose load and the simultaneous glucose-induced stimulation of insulin secretion did not alter the whole-body protein synthesis or breakdown rate. In non-exercise conditions, physiological hyperinsulinemia can stimulate MPS in an insulin-dependent manner [159]. Under specific circumstances, such as limited carbohydrate availability (700 kcal/day), normal levels of IGF-1 are not restored [160]. In healthy young and older individuals, the impact of insulin on MPS becomes significant only when amino acid delivery to SM increases. The influence of insulin on MPS is diminished in older adults and those with IR. This reduction is likely to affect insulin signaling related to MPS metabolism and contributes to endothelial dysfunction, with consequent metabolic and cardiovascular problems [161].

The effect of carbohydrates on MPS seems to be affected by the type, duration, and intensity of exercise. The increase in intramuscular glycogen affects whole-body protein synthesis, degradation, and net balance during prolonged exercise in humans. In contrast, adding glucose to a protein dose that maximizes protein synthesis stimulates MPS. Despite the increase in insulin, it did not exhibit additive or synergistic effects on the stimulation of MPS or the inhibition of MPB, nor did it enhance the post-exercise stimulation of MPS [129]. This is similar to the findings of Wilburn et al. (2020) [162], where pre-exercise and exercise carbohydrate supplementation does not intensify the anabolic mTOR signaling initiated after RT in younger recreationally trained men. In contrast, a review and RCT showed that low carbohydrate availability, especially in acute bouts ≥ 45 min and long-term exposition (8–12 w), increases BCAA oxidation in SM and might blunt the anabolic response and limit performance in anaerobic exercise and hypertrophy in high-intensity exercise [163,164].

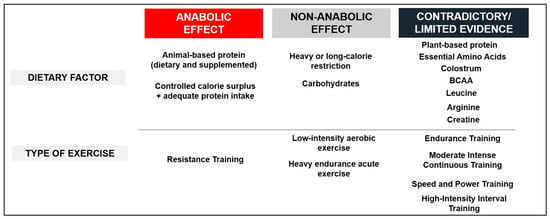

Figure 3 and Figure 4 synthesize the effects of dietary factors and exercise modality on the hormonal anabolic response in SM. Figure 3 synthesizes the manner in which dietary factors and exercise influence IGF-1 and IGFBPs within the SM of healthy adults, categorizing the effects into three groups: (a) anabolic effect, where evidence consistently indicates their impact on IGF-1 or IGFBPs; (b) no anabolic effect, where evidence has not established any effects on circulating IGF-1 or IGFBPs; and (c) limited or contradictory evidence, where there is a lack of consistency in the findings regarding their effects on circulating IGF-1 or IGFBPs. The majority of the evidence derives from studies involving younger male subjects (20–30 years) and older male and female subjects (menopause or 60 years and above). It is noticeable that evidence from SIT and HIIT has ranged from no to positive anabolic effects in a few studies, but high-quality evidence remains lacking. Few studies report circulating IGF-1 levels as the primary outcome in studies of anabolic amino acids.

Figure 3.

Effect of dietary factors and exercise on the IGF-1 or its binding proteins in healthy adults. This figure categorizes the dietary factors and types of exercise studied into three groups: (1) anabolic effect, where evidence is consistent regarding their impact on IGF-1 or IGFBPs; (2) no anabolic effect, where evidence has not demonstrated any effects on circulating IGF-1 or IGFBPs; and (3) limited or contradictory evidence, where there is a lack of consistency in the evidence concerning their effects on circulating IGF-1 or IGFBPs. Most of the evidence comes from younger men (20–30 y/o) and older men and women (menopause or ≥60 y/o). This Figure is an original work from the author.

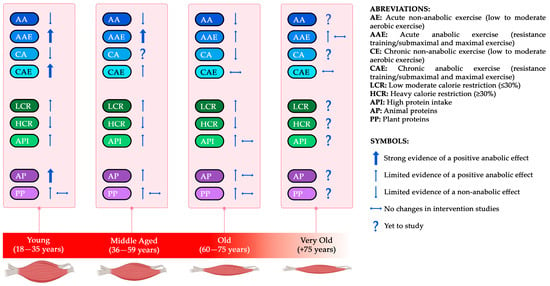

Figure 4.

Conceptual framework of the main exercise and dietary factors affecting the anabolic stimuli (IGF-1-Insulin-mTOR) throughout aging. Figure 4 synthesizes the evidence concerning the effects of the primary exercise and dietary factors identified in this review on insulin and IGF-1 levels across four stages of aging: young, middle-aged, old, and very old. RT and AP elicit an anabolic response, particularly in young and middle-aged individuals, whereas responses in older populations are more heterogeneous. CR at low levels does not influence the anabolic effect, whilst heavy CR does. There remains a need for further data regarding older subjects across all topics. The anabolic effects of both animal and plant protein sources in healthy adults include increases in IGF-1 levels and MPS. Given that these effects may vary by age group, this information can serve as a foundational framework for future research. This Figure is an original work from the author.

8. Limitations

This work identifies significant limitations in the studies included and excluded that examine the impact of dietary factors and exercise on SM. The sense of progression and individualization over periods of 1 to 6 months is incorporated into the evidence, but there are remaining concerns, such as the maintenance phase and new progression methods to support long-term adaptations or sustain SM improvements. Assessments associated with the impact of anabolic hormonal changes induced by exercise on SM beyond 1RM or isometric strength, such as speed and power, which are lost with aging, are still lacking. The clinical importance of the significant or nonsignificant results is not always considered. There is information available on studies assessing AP and PP from food sources or dietary supplements, but evidence comparing food sources vs. dietary supplements is still limited.

Most of the included RCTs featured a sample size calculation, but some did not consider the effect size in their discussion. In several cases, the groups usually consisted of 10 to 20 individuals, which could significantly influence the impact of size effects on their conclusions. The effects of changes in the INS/IGF-1 axis, exercise modality, or dietary factors on FFM or SM are beyond this review’s scope, yet biases may affect the quantitative outcomes measured by different body composition methods (field-based vs. reference methods). This review mainly serves as a framework for future research. Its conclusions focus on key dietary factors and exercise methods identified as essential for lifestyle modifications to promote and support optimal quality and quantity of SM across aging.

9. Conclusions and Practical Considerations

In summary, data from grades A to C of evidence suggest that the primary lifestyle and aging factors associated with decreased hormonal anabolic response in SM include physical inactivity, fitness level, abdominal adiposity, fat infiltration, mitochondrial dysfunction, inadequate protein intake, heavy CR, inadequate exercise modality, and dosage across young, middle-aged, and older adults.

The conclusions coming from Grade A evidence addressing the effect of dietary factors and exercise modality on SM hormonal anabolic response are described as follows:

- Acute and chronic exposure to RT improves anabolic response, especially in young and middle-aged subjects;

- Acute heavy endurance exercise and chronic low-intensity exercise do not induce an anabolic response;

- Moderate CR (≤30%) does not seem to affect the anabolic response;

- Short- and long-term heavy CR (30–50%) seems to decrease anabolic response in SM;

- Low carbohydrate availability impairs IGF-1 and GH function;

- High-quality proteins stimulate MPS and IGF-1 in a dose-dependent manner.

Future research is needed in the following areas:

- Local effects of any exercise modality on intramuscular anabolic signaling and hypertrophic adaptations;

- In general, all dietary factors and exercise modalities are considered in very old subjects, especially combined protocols (diet + exercise);

- Optimization of diet + exercise to combat AR in older subjects;

- Individualization of acute dose–response and chronic protein intake by age sub-groups (young, middle-aged, old, and very old);

- Optimal plant–protein combinations to achieve the same anabolic effect as AP;

- Appropriate dosage, timing, and periodization of CR;

- Proper dosage, periodization, and progression of exercise to ensure long-term benefits;

- Sex differences in the anabolic response of SM to dietary factors and exercise.

Practical recommendations by age group based on Grade A evidence that may be beneficial are the following:

- Young and middle-aged individuals:

- RT frequency suggested ≥2–3 x/w plus additional sessions of SIT, HIIT, or moderate- to high-intensity aerobic exercise;

- Consider including portions of AP food sources or AP or PP dietary supplements that match in leucine content;

- Increasing protein intake during CR.

- Older adults:

- RT frequency recommended 2–3 x/w;

- High-intensity exercise mixed with low to moderate intensity aerobic exercise to stimulate both hormonal response in SM but also favor IS;

- Avoiding moderate to heavy CR (≥30%);

- It is suggested to increase protein intake (~1.2–1.8 g/kg/d) and consider the addition of protein supplements rich in leucine, including leucine-rich sources, in the absence of IR;

- Adjusting carbohydrate sources and timing to favor IS.

In any case, regular monitoring by field experts is advisable to tailor these recommendations. Revising expert guidelines, such as the Global consensus on optimal exercise strategies for promoting healthy longevity in older adults (2025) [165] and the Dietary protein intake to support healthy muscle aging in the 21st century and beyond: considerations and future directions (2025) [166], is suggested.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The Author thanks David Jaso for his assistance with the figure design and the Secretaria de Ciencia, Humanidades, Tecnologia e Innovacion.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| Akt | Protein kinase B |

| ALS | Acid-labile subunit |

| AMPK | AMP-activated protein kinase |

| AP | Animal proteins |

| AR | Anabolic resistance |

| BCAA | Branched Chain Amino Acids |

| CR | Caloric restriction |

| EAA | Essential amino acids |

| FFM | Fat-free mass |

| FOXO1 | Transcription factor; Forkhead box protein O1 |

| FRS | Fractional Rate Protein Synthesis |

| HIIT | High-intensity interval training |

| IGF-1 | Insulin Growth Factor-1 |

| IGFBPs | Insulin Growth Factor Binding Proteins |

| INS | Insulin |

| IR | Insulin resistance |

| IS | Insulin sensitivity |

| MICT | Moderate-Intensity Continuous Training |

| MPB | Muscle protein breakdown |

| MPS | Muscle protein synthesis |

| MSTN | Myostatin |

| Mtor | Mechanistic target of rapamycin |

| P | Grams of protein |

| PAL | Physical Activity Level |

| PGC-1α | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPAR-γ)-coactivator-1α |

| PI3K | Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase |

| PP | Plan proteins |

| RDA | Recommended Dietary Allowance |

| RT | Resistance training |

| SIRTs | Family of proteins, nicotine adenine dinucleotide(+)-dependent histone Deacetylases |

| SIT | Sprint Interval Training |

| SM | Skeletal muscle |

| UPP | Ubiquitin–proteasome pathway |

| VO2MAX | Maximum rate of oxygen consumption |

| W | Weeks |

References

- Kraemer, W.J.; Ratamess, N.A.; Hymer, W.C.; Nindl, B.C.; Fragala, M.S. Growth hormone(s), testosterone, insulin-like growth factors, and cortisol: Roles and integration for cellular development and growth with exercise. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velloso, C.P. Regulation of muscle mass by growth hormone and IGF-1. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2008, 154, 557–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barclay, R.D.; Burd, N.A.; Tyler, C.; Tillin, N.A.; Mackenzie, R.W. The role of the IGF-1 signaling cascade in muscle protein synthesis and anabolic resistance in aging skeletal muscle. Front. Nutr. 2019, 6, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Syverud, B.C.; VanDusen, K.W.; Larkin, L.M. Growth factors for skeletal muscle tissue engineering. Cells Tissues Organs 2016, 202, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuyama, T.; Kyohara, M.; Terauchi, Y.; Shirakawa, J. The roles of the IGF axis in the regulation of the metabolism: Interaction and difference between insulin receptor signaling and IGF-1 receptor signaling. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Ji, Y.; Liu, R.; Zhu, X.; Wang, K.; Yang, X.; Liu, B.; Gao, Z.; Yan, Y.; Shen, Y.; et al. Mitochondrial Dysfunction: Roles in Skeletal Muscle Atrophy. J. Transl. Med. 2023, 21, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, R.W.; Traylor, D.A.; Weijs, P.J.; Phillips, S.M. Defining anabolic resistance: Implications for delivery of clinical care nutrition. Curr. Opin. Crit. Care 2018, 24, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paulussen, K.J.M.; McKenna, C.F.; Beals, J.W.; Wilund, K.R.; Salvador, A.F.; Burd, N.A. Anabolic resistance of muscle protein turnover comes in various shapes and sizes. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 615849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burd, N.A.; Gorissen, S.H.; Van Loon, L.J. Anabolic resistance of muscle protein synthesis with aging. Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 2013, 41, 169–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haran, P.H.; Rivas, D.A.; Fielding, R.A. Role and potential mechanisms of anabolic resistance in sarcopenia. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2012, 3, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argilés, J.M.; Campos, N.; Lopez-Pedrosa, J.; Rueda, R.; Rodriguez-Mañas, L. Skeletal muscle regulates metabolism via interorgan crosstalk: Roles in health and disease. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2016, 17, 789–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boros, K.; Freemont, T. Physiology of ageing of the musculoskeletal system. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 2017, 31, 203–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angulo, J.; Assar, M.E.; Álvarez-Bustos, A.; Rodríguez-Mañas, L. Physical activity and exercise: Strategies to manage frailty. Redox Biol. 2020, 35, 101513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shur, N.F.; Creedon, L.; Skirrow, S.; Atherton, P.J.; MacDonald, I.A.; Lund, J.; Greenhaff, P.L. Age-Related Changes in Muscle Architecture and Metabolism in Humans: The Likely Contribution of Physical Inactivity to Age-Related Functional Decline. Ageing Res. Rev. 2021, 68, 101344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, H.N.; Jung, C.H.; Hwang, Y. Sarcopenia in youth. Metabolism 2023, 144, 155557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gries, K.J.; Raue, U.; Perkins, R.K.; Lavin, K.M.; Overstreet, B.S.; D’Acquisto, L.J.; Graham, B.; Finch, W.H.; Kaminsky, L.A.; Trappe, T.A.; et al. Cardiovascular and Skeletal Muscle Health with Lifelong Exercise. J. Appl. Physiol. 2018, 125, 1636–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dardevet, D.; Rémond, D.; Peyron, M.-A.; Papet, I.; Savary-Auzeloux, I.; Mosoni, L. Muscle Wasting and Resistance of Muscle Anabolism: The “Anabolic Threshold Concept” for Adapted Nutritional Strategies during Sarcopenia. Sci. World J. 2012, 2012, 269531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moro, T.; Brightwell, C.R.; Deer, R.R.; Graber, T.G.; Galvan, E.; Fry, C.S.; Volpi, E.; Rasmussen, B.B. Muscle protein anabolic resistance to essential amino acids does not occur in healthy older adults before or after resistance exercise training. J. Nutr. 2018, 148, 900–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherlala, R.A.; Kammerer, C.M.; Kuipers, A.L.; Wojczynski, M.K.; Ukraintseva, S.V.; Feitosa, M.F.; Mengel-From, J.; Zmuda, J.M.; Minster, R.L. Relationship between Serum IGF-1 and BMI Differs by Age. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2020, 76, 1303–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiaffino, S.; Mammucari, C. Regulation of skeletal muscle growth by the IGF1-Akt/PKB pathway: Insights from genetic models. Skelet. Muscle 2011, 1, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidlingmaier, M.; Friedrich, N.; Emeny, R.T.; Spranger, J.; Wolthers, O.D.; Roswall, J.; Körner, A.; Obermayer-Pietsch, B.; Hübener, C.; Dahlgren, J.; et al. Reference Intervals for Insulin-like Growth Factor-1 (IGF-1) from Birth to Senescence: Results from a Multicenter Study Using a New Automated Chemiluminescence IGF-1 Immunoassay Conforming to Recent International Recommendations. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 99, 1712–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovannini, S.; Marzetti, E.; Borst, S.E.; Leeuwenburgh, C. Modulation of GH/IGF-1 axis: Potential strategies to counteract sarcopenia in older adults. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2008, 129, 593–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, A.I.; Priego, T.; Moreno-Ruperez, Á.; González-Hedström, D.; Granado, M.; López-Calderón, A. IGF-1 and IGFBP-3 in inflammatory cachexia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junnila, R.K.; List, E.O.; Berryman, D.E.; Murrey, J.W.; Kopchick, J.J. The GH/IGF-1 axis in ageing and longevity. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2013, 9, 366–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eliakim, A.; Nemet, D. Exercise Training, Physical Fitness and the Growth Hormone-Insulin-Like Growth Factor-1 Axis and Cytokine Balance. Med. Sport Sci. 2010, 128, 128–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartorio, A.; Marazzi, N.; Agosti, F.; Faglia, G.; Corradini, C.; Palo, E.D.; Cella, S.; Rigamonti, A.; Muller, E.E. Elite Volunteer Athletes of Different Sport Disciplines May Have Elevated Baseline GH Levels Divorced from Unaltered Levels of Both IGF-1 and GH-Dependent Bone and Collagen Markers: A Study On-The-Field. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2004, 27, 410–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, D.; Huang, C.; Chen, S.; Yang, W. Serum reference value of two potential doping candidates—Myostatin and insulin-like growth factor-I in the healthy young male. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2017, 14, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herbert, P.; Hayes, L.D.; Sculthorpe, N.; Grace, F.M. High-intensity interval training (HIIT) increases insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-1) in sedentary aging men but not masters’ athletes: An observational study. Aging Male 2016, 20, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curiel-Cervantes, V.; Solis-Sainz, J.C.; Camacho-Barrón, M.; Aguilar-Galarza, A.; Valencia, M.E.; Anaya-Loyola, M.A. Systematic training in master swimmer athletes increases serum insulin growth factor-1 and decreases myostatin and irisin levels. Growth Factors 2022, 40, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, T.K.; Oh, B.K.; Lee, M.Y.; Sung, K.C. Association between physical activity and insulin resistance using the homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance independent of waist circumference. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 6002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ateia, S.; Rusu, E.; Cristescu, V.; Enache, G.; Cheța, D.M.; Radulian, G. Proinsulin and age in general population. J. Med. Life 2013, 6, 424–429. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bryhni, B.; Arnesen, E.; Jenssen, T.G. Associations of age with serum insulin, proinsulin and the proinsulin-to-insulin ratio: A cross-sectional study. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2010, 10, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, N.Y.; Noordam, R.; Christodoulides, C. Telomere length and metabolic syndrome traits: A Mendelian randomisation study. Aging Cell 2021, 20, e13445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, L.A. Insulin resistance and biological aging: The role of body mass, waist circumference, and inflammation. Biomed. Res. Int. 2022, 2022, 2146596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokarz, V.L.; MacDonald, P.E.; Klip, A. The cell biology of systemic insulin function. J. Cell Biol. 2018, 217, 2273–2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunt, N.J.; Kang, S.W.; Lockwood, G.P.; Couteur, D.G.L.; Cogger, V.C. Hallmarks of Aging in the Liver. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2019, 17, 1151–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X.; Asthana, P.; Gurung, S.; Zhang, S.; Wong, S.K.K.; Fallah, S.; Chow, C.F.W.; Che, S.; Zhai, L.; Wang, Z.; et al. Regulation of age-associated insulin resistance by MT1-MMP-mediated cleavage of insulin receptor. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 3749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorim, J.A.; Coppotelli, G.; Rolo, A.P.; Palmeira, C.M.; Ross, J.M.; Sinclair, D.A. Mitochondrial and Metabolic Dysfunction in Ageing and Age-Related Diseases. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2022, 18, 243–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritz, P.; Berrut, G. Mitochondrial function, energy expenditure, aging and insulin resistance. Diabetes Metab. 2005, 31, 5S67–5S73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thankamony, A.; Capalbo, D.; Marcovecchio, M.L.; Sleigh, A.; Jørgensen, S.W.; Hill, N.R.; Mooslehner, K.; Yeo, G.S.; Bluck, L.; Juul, A.; et al. Low circulating levels of IGF-1 in healthy adults are associated with reduced β-cell function, increased intramyocellular lipid, and enhanced fat utilization during fasting. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 99, 2198–2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shou, J.; Chen, P.; Xiao, W. Mechanism of increased risk of insulin resistance in aging skeletal muscle. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2020, 12, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Hu, Y.; Pan, Y.; Li, M.; Niu, Y.; Zhang, T.; Sun, H.; Zhou, S.; Liu, M.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Fatty infiltration in the musculoskeletal system: Pathological mechanisms and clinical implications. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1406046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conte, M.; Martucci, M.; Sandri, M.; Franceschi, C.; Salvioli, S. The Dual Role of the Pervasive “Fattish” Tissue Remodeling With Age. Front. Endocrinol. 2019, 10, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dondero, K.; Friedman, B.; Rekant, J.; Landers-Ramos, R.; Addison, O. The effects of myosteatosis on skeletal muscle function in older adults. Physiol. Rep. 2024, 12, e16042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, X.; Zhang, P.; Chen, X.; Liu, W. Ubiquitin-proteasome pathway in skeletal muscle atrophy. Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 1289537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Couteur, D.G.; Ngu, M.C.; Hunt, N.J.; Brandon, A.E.; Simpson, S.J.; Cogger, V.C. Liver, ageing and disease. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2025, 22, 680–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dehkhoda, F.; Lee, C.M.M.; Medina, J.; Brooks, A.J. The Growth Hormone Receptor: Mechanism of Receptor Activation, Cell Signaling, and Physiological Aspects. Front. Endocrinol. 2018, 9, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zammit, P.S. Function of the myogenic regulatory factors Myf5, MyoD, Myogenin and MRF4 in skeletal muscle, satellite cells and regenerative myogenesis. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2017, 72, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arantes, V.H.F.; da Silva, D.P.; de Alvarenga, R.L.; Terra, A.; Koch, A.; Machado, M.; Monteiro Baboia Pompeo, F.A. Skeletal muscle hypertrophy: Molecular and applied aspects of exercise physiology. Ger. J. Exerc. Sport Res. 2020, 50, 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harridge, S.D.R. Ageing and local growth factors in muscle. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2003, 13, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassilakos, G.; Barton, E.R. Insulin-like growth factor I regulation and its actions in skeletal muscle. Compr. Physiol. 2018, 9, 413–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, X.; Yan, Q.; Wang, D.; Du, G.; Zhou, J. IGF-1 signaling regulates mitochondrial remodeling during myogenic differentiation. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halling, J.F.; Pilegaard, H. PGC-1α-mediated regulation of mitochondrial function and physiological implications. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2020, 45, 927–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, R.P.; Duarte, J.A. Protein turnover in skeletal muscle: Looking at molecular regulation towards an active lifestyle. Int. J. Sports Med. 2023, 44, 763–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartori, R.; Romanello, V.; Sandri, M. Mechanisms of muscle atrophy and hypertrophy: Implications in health and disease. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wideman, L.; Weltman, J.Y.; Hartman, M.L.; Veldhuis, J.D.; Weltman, A. Growth hormone release during acute and chronic aerobic and resistance exercise. Sports Med. 2002, 32, 987–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterczala, A.J.; Pierce, J.R.; Barnes, B.R.; Urso, M.L.; Matheny, R.W.; Scofield, D.E.; Flanagan, S.D.; Maresh, C.M.; Zambraski, E.J.; Kraemer, W.J.; et al. Insulin-like growth factor-I biocompartmentalization across blood, interstitial fluid, and muscle, before and after 3 months of chronic resistance exercise. J. Appl. Physiol. 2022, 133, 170–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hargreaves, M.; Spriet, L.L. Skeletal muscle energy metabolism during exercise. Nat. Metab. 2020, 2, 817–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, A.J.; Richter, E.A. Regulatory mechanisms of skeletal muscle protein turnover during exercise. J. Appl. Physiol. 2009, 106, 1702–1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widdowson, W.M.; Healy, M.; Sönksen, P.H.; Gibney, J. The physiology of growth hormone and sport. Growth Horm. IGF Res. 2009, 19, 308–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arazi, H.; Damirchi, A.; Faraji, H.; Rahimi, R. Hormonal responses to acute and chronic resistance exercise in middle-age versus young men. Sport Sci. Health 2012, 8, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, T.W.; Eddens, L.; Kupusarevic, J.; Simoes, D.C.M.; Furber, M.J.W.; Van Someren, K.A.; Howatson, G. Aerobic exercise intensity does not affect the anabolic signaling following resistance exercise in endurance athletes. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 10785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Alcantara Borba, D.; Da Silva Alves, E.; Rosa, J.P.P.; Alves Facundo, L.; Magno Amaral Acosta, C.; Coelho Silva, A.; Veruska Narciso, F.; Silva, A.; Túlio de Mello, M. Can IGF-1 Serum Levels Really be Changed by Acute Physical Exercise? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Phys. Act. Health 2020, 17, 575–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, D.R.; McKay, B.R.; Tarnopolsky, M.A.; Parise, G. Blunted satellite cell response is associated with dysregulated IGF-1 expression after exercise with age. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2018, 118, 2225–2231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, P.A.; da Silva Aguiar, S.; Barbosa, L.D.M.P.F.; Dos Santos Rosa, T.; Sales, M.M.; Maciel, L.A.; Lopes de Araújo Leite, P.; Gutierrez, S.D.; Minuzzi, L.G.; Sousa, C.V.; et al. Relationship of Testosterone, LH, Estradiol, IGF-1, and SHBG with Physical Performance of Master Athletes. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2023, 95, 363–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, K.; Szewczyk, A.; Kiszałkiewicz, J.; Middalska-Sek, M.; Domańska-Senderowska, D.; Brzeziański, M.; Lulińska, E.; Jegier, A.; Brzeziańska-Lasota, E. Type of training has a significant influence on the GH/IGF-1 axis but not on regulating miRNAs. Biol. Sport 2020, 37, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arazi, H.; Babaei, P.; Moghimi, M.; Asadi, A. Acute effects of strength and endurance exercise on serum BDNF and IGF-1 levels in older men. BMC Geriatr. 2021, 21, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kliszczewicz, B.; Markert, C.D.; Bechke, E.; Williamson, C.; Clemons, K.N.; Snarr, R.L.; McKenzie, M.J. Acute effect of popular high-intensity functional training exercise on physiologic markers of growth. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2021, 35, 1677–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behrendt, T.; Kirschnick, F.; Kröger, L.; Beileke, P.; Rezepin, M.; Brigadski, T.; Leßmann, V.; Schega, L. Comparison of the effects of open vs. closed skill exercise on the acute and chronic BDNF, IGF-1 and IL-6 response in older healthy adults. BMC Neurosci. 2021, 22, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eryılmaz, S.K.; Aslankeser, Z.; Özdemir, Ç.; Özgünen, K.; Kurdak, S. The effect of 30-m repeated sprint exercise on muscle damage indicators, serum insulin-like growth factor-I and cortisol. Biomed. Hum. Kinet. 2019, 11, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taipale, R.; Gagnon, S.; Ahtiainen, J.; Häkkinen, K.; Kyröläinen, H.; Nindl, B. Active recovery shows favorable IGF-1 and IGF binding protein responses following heavy resistance exercise compared to passive recovery. Growth Horm. IGF Res. 2019, 48–49, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geesmann, B.; Gibbs, J.C.; Mester, J.; Koehler, K. Association between energy balance and metabolic hormone suppression during ultraendurance exercise. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2017, 12, 984–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Chang, J.S.; Kim, H.; Lee, K.H.; Kong, I.D. Intense walking exercise affects serum IGF-1 and IGFBP3. J. Lifestyle Med. 2015, 5, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasani-Ranjbar, S.; Soleymani Far, E.; Heshmat, R.; Rajabi, H.; Kosari, H. Time course responses of serum GH, insulin, IGF-1, IGFBP1, and IGFBP3 concentrations after heavy resistance exercise in trained and untrained men. Endocrine 2012, 41, 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges Bastos, C.L.; Miranda, H.; Vale, R.G.; Portal Mde, N.; Gomes, M.T.; Novaes Jda, S.; Winchester, J.B. Chronic effect of static stretching on strength performance and basal serum IGF-1 levels. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2013, 27, 2465–2472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, M.A.D.; Gerage, A.M.; Silva, D.R.P.D.; Ribeiro, A.S.; Machado, D.G.D.S.; Pina, F.L.C.; Tomeleri, C.M.; Venturini, D.; Barbosa, D.S.; Mayhew, J.L.; et al. Effect of resistance training with different frequencies and subsequent detraining on muscle mass and appendicular lean soft tissue, IGF-1, and testosterone in older women. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2019, 19, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Q.; Lou, K.; Hou, L.; Lu, Y.; Sun, L.; Tan, S.C.; Low, T.Y.; Kord-Varkaneh, H.; Pang, S. The effect of resistance training on serum insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1): A systematic review and meta-analysis. Complement. Ther. Med. 2020, 50, 102360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, J.; Schoenfeld, B.J.; Nakazato, K. The role of hormones in muscle hypertrophy. Phys. Sportsmed. 2018, 46, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porter, C.; Reidy, P.T.; Bhattarai, N.; Sidossis, L.S.; Rasmussen, B.B. Resistance exercise training alters mitochondrial function in human skeletal muscle. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2015, 47, 1922–1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groennebaek, T.; Vissing, K. Impact of resistance training on skeletal muscle mitochondrial biogenesis, content, and function. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiménez-Roldán, M.J.; Sañudo, B.; Carrasco Páez, L. Influence of High-Intensity Interval Training on IGF-1 Response, Brain Executive Function, Physical Fitness and Quality of Life in Sedentary Young University Women-Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasuda, Y. Sex differences in salivary free insulin-like growth factor-1 levels in elderly outpatients. Cureus 2021, 13, e17553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroto-Izquierdo, S.; Martín-Rivera, F.; Nosaka, K.; Beato, M.; González-Gallego, J.; De Paz, J.A. Effects of submaximal and supramaximal accentuated eccentric loading on mass and function. Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 1176835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huschtscha, Z.; Parr, A.; Porter, J.; Costa, R.J.S. The Effects of a High-Protein Dairy Milk Beverage With or Without Progressive Resistance Training on Fat-Free Mass, Skeletal Muscle Strength and Power, and Functional Performance in Healthy Active Older Adults: A 12-Week Randomized Controlled Trial. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 644865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, P.M.; Nunes, J.P.; Tomeleri, C.M.; Nascimento, M.A.; Schoenfeld, B.J.; Antunes, M.; Gobbo, L.A.; Teixeira, D.; Cyrino, E.S. Resistance training performed with single and multiple sets induces similar improvements in muscular strength, muscle mass, muscle quality, and IGF-1 in older women: A randomized controlled trial. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2020, 34, 1008–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Micielska, K.; Gmiat, A.; Zychowska, M.; Kozlowska, M.; Walentukiewicz, A.; Lysak-Radomska, A.; Jaworska, J.; Rodziewicz, E.; Duda-Biernacka, B.; Ziemann, E. The beneficial effects of 15 units of high-intensity circuit training in women is modified by age, baseline insulin resistance and physical capacity. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2019, 152, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arazi, H.; Khanmohammadi, A.; Asadi, A.; Haff, G.G. The effect of resistance training set configuration on strength, power, and hormonal adaptation in female volleyball players. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2018, 43, 154–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, L.; Slater, G.; Hackett, D.; Johnson, N.; O’Connor, H. Physiological implications of preparing for a natural male bodybuilding competition. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2018, 18, 619–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojanen, T.; Kyröläinen, H.; Igendia, M.; Häkkinen, K. Effect of prolonged military field training on neuromuscular and hormonal responses and shooting performance in warfighters. Mil. Med. 2018, 183, e705–e712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ives, S.J.; Norton, C.; Miller, V.; Minicucci, O.; Robinson, J.; O’Brien, G.; Escudero, D.; Paul, M.; Sheridan, C.; Curran, K.; et al. Multi-modal exercise training and protein-pacing enhances physical performance adaptations independent of growth hormone and BDNF but may be dependent on IGF-1 in exercise-trained men. Growth Horm. IGF Res. 2017, 32, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellami, M.; Dhahbi, W.; Hayes, L.D.; Padulo, J.; Rhibi, F.; Djemail, H.; Chaouachi, A. Combined sprint and resistance training abrogates age differences in somatotropic hormones. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0183184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- So, W.; Song, M.; Park, Y.; Cho, B.; Lim, J.; Kim, S.; Song, W. Body composition, fitness level, anabolic hormones, and inflammatory cytokines in the elderly: A randomized controlled trial. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2013, 25, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nindl, B.C.; McClung, J.P.; Miller, J.K.; Karl, J.P.; Pierce, J.R.; Scofield, D.E.; Young, A.J.; Lieberman, H.R. Bioavailable IGF-1 is associated with fat-free mass gains after physical training in women. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2011, 43, 793–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishida, Y.; Matsubara, T.; Tobina, T.; Shindo, M.; Tokuyama, K.; Tanaka, K.; Tanaka, H. Effect of low-intensity aerobic exercise on insulin-like growth factor-I and insulin-like growth factor-binding proteins in healthy men. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2010, 2010, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, D.; Jun, T.; Park, K.; Chang, H.; So, W.Y.; Song, W. Twelve weeks of combined exercise is better than aerobic exercise for increasing growth hormone in middle-aged women. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. 2010, 20, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borst, S.E.; De Hoyos, D.V.; Garzarella, L.; Vincent, K.; Pollock, B.H.; Lowenthal, D.T.; Pollock, M.L. Effects of resistance training on insulin-like growth factor-I and IGF binding proteins. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2001, 33, 648–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, S.R.; Hawley, J.A. Update on the effects of physical activity on insulin sensitivity in humans. BMJ Open Sport Exerc. Med. 2017, 2, e000143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiahao, L.; Jiajin, L.; Yifan, L. Effects of resistance training on insulin sensitivity in the elderly: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Exerc. Sci. Fit. 2021, 19, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]