Abstract

Background: Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is a frequent pregnancy pathology with poor maternal and fetal outcomes and risk of type 2 diabetes in later life. Despite known risk factors, such as obesity, age, and familial history, new data suggest that environmental exposure to agents, such as pesticides, can play a role in the etiogenesis of GDM. Objective: The epidemiologic, experimental, and mechanistic evidence between pesticide exposure and GDM risk is summarized here, and we concentrate on recent research (2000–2025). Methods: We conducted a literature search in PubMed, Embase, and the Cochrane Library for studies published from January 2000 to December 2025 using combinations of the terms “fertilizers”, “herbicides”, and “pesticides” with “diabetes mellitus” and “gestational diabetes”. After deduplication, 12 unique studies met inclusion criteria for qualitative synthesis (GDM endpoint or pregnancy glycemia with pesticide exposure). Results: Occupational and agricultural exposure to pesticides during first pregnancy was determined to be associated with a significantly increased risk of GDM through various epidemiologic studies. New studies have implicated new classes of pesticides, including pyrethroids and neonicotinoids, with higher GDM risk with first-trimester exposure. Experimental studies suggest that pesticides provide potential endocrine-disrupting chemicals that can induce insulin resistance through disruption of hormonal signaling, oxidative stress, inflammation, β-cell toxicity, and epigenetic modifications. However, significant limitations exist. Most of the evidence is observational, measurement of exposure is often indirect, and confounding factors are difficult to exclude. Notably, low dietary and residential exposure is not well studied, and dose–response relationships are undefined. Conclusions: New data indicate that pesticide exposure during early pregnancy and occupational exposure may increase the risk of GDM. Prospective cohort studies using biomonitoring, chemical mixture exposure, and geographic variation in pesticide exposure should be the focus of future research. Due to potential public health implications, preventive strategies to ensure the quality of nutrition and to reduce maternal exposure to pesticides during pregnancy are rational.

1. Introduction

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) affects approximately 5–15% of pregnancies and is associated with increased risks of preeclampsia, fetal macrosomia, cesarean delivery, and long-term metabolic disorders in both mothers and their offspring [1]. GDM is multifactorially derived from both metabolic and environmental influences, such as maternal age, adiposity, and dietary quality [2,3]. High intake of refined carbohydrates, saturated fats, and ultra-processed foods elevates risk through postprandial hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinemia [4,5]. In contrast, Mediterranean-style or prudent dietary patterns, rich in whole grains, pulses, fruits, non-starchy vegetables, and unsaturated fats, are associated with reduced risk [4,5,6,7]. Proper fiber, vitamin D, and magnesium intake assist glucose homeostasis and attenuate oxidative stress [8,9]. In contrast, exposure to metabolism-altering chemicals, notably pesticide residues and persistent organic pollutants transferred through foods, has been implicated in dysglycemia and GDM, interactions that are apparently moderated by dietary quality [10,11].

Pesticides, which are used in agriculture, vector control, and homes, include insecticides (organophosphates, carbamates, pyrethroids, neonicotinoids), herbicides (e.g., 2,4-D, dicamba, glyphosate), fungicides (e.g., triazoles), and persistent organochlorines (OCs), which are known to bioaccumulate in human tissues [12,13,14]. Since 2000, epidemiology has linked pesticide exposure during early pregnancy and farm work to higher GDM odds [12,15,16]; from 2023 to 2025, multiple cohorts reported associations between first-trimester neonicotinoid biomarkers and GDM [17,18]. Biomonitoring indicates widespread prenatal exposure to 2,4-D/dicamba and chlorpyrifos in some regions [13,19]. Mechanistic literature outlines plausible diabetogenic pathways relevant to GDM physiology [20,21] (Table 1).

Table 1.

Key diabetogenic pathways relevant to GDM.

1.1. Metabolic and Insulin-Signaling Barrier

Experimental models show that organophosphate (OP), pyrethroid, organochlorine (OC), and neonicotinoid pesticides act as metabolism-disrupting agents, affecting the insulin receptor (IR)/insulin receptor substrate (IRS)–PI3K–Akt signaling pathway. OPs like chlorpyrifos and diazinon inhibit IRS-1 and Akt phosphorylation of skeletal muscle and adipose tissue, respectively, suppressing GLUT4 protein levels and glucose uptake [22,23]. Pyrethroids (e.g., permethrin, cypermethrin) modulate hepatic glucose metabolism by changing glycogen synthase kinase-3β and increasing gluconeogenic enzymes (PEPCK, G6Pase) for a net shift toward hyperglycemia [22]. OCs and PCBs activate lipogenic nuclear receptors, including PPAR-γ and AhR, leading to steatosis and hepatocellular insulin resistance [20]. Neonicotinoids like imidacloprid or thiamethoxam decrease pancreatic glucose-stimulated insulin release, downregulate β-cell GLUT2, and induce apoptosis by mitochondrial failure and caspase-3 activation [24]. Together, these alterations amplify the physiological insulin resistance of late gestation, tipping maternal glucose homeostasis toward the intolerance characteristic of GDM.

1.2. Oxidative Stress and Inflammatory Barrier

One of the prominent routes connecting pesticide exposure to gestational dysglycemia is the impairment of redox homeostasis and the functioning of the mitochondria. Organophosphate pesticides, such as chlorpyrifos, inhibit the electron transport complexes I and III in the mitochondria under the process of oxidative phosphorylation and generate excessive reactive oxygen species (ROS), causing lipid peroxidation in muscle and hepatic tissues [11,25]. Experimental models suggest that chronic low-dose systemic exposure to chlorpyrifos is associated with increased oxidative stress, activates NF-κB protein, and increases inflammatory cytokine expression like TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β, inducing systemic and placental inflammations similar to the low-grade inflammatory condition in GDM [26]. Analogously, pyrethroids like permethrin cause mitochondrial swelling and superoxide amassing, which induces muscle and adipose cell-bound insulin resistance and inflammatory cascades [11,23].

At the level of the pancreas, neonicotinoids and organophosphates induce oxidative stress and endoplasmic reticulum distress, thereby jeopardizing the integrity of β-cells and insulin secretion. For example, exposure to imidacloprid reduces GLUT2 expression and disrupts glucose-stimulated insulin release via the activation of the IRE1α/XBP1/CHOP signaling pathway, resulting in mitochondrial damage and β-cell apoptosis [22]. Similar redox-mediated injury mechanisms are observable in vivo; Djekkoun et al. (2022) illustrated that chronic exposure to chlorpyrifos during gestation in pregnant mice led to maternal hyperglycemia, increased levels of TNF-α, and impaired placental insulin signaling [25]. Taken together, these results indicate that pesticides contribute to sustained oxidative stress and the activation of inflammatory cytokines, both of which are critical to the development of insulin resistance and metabolic dysfunction of the placenta during pregnancy.

1.3. Incretin and Neuroendocrine Barrier

Beyond classical insulin action, pesticides may also interfere with gut–pancreas neuroendocrine regulation of postprandial glucose metabolism. Although direct human evidence is limited, experimental studies suggest that pesticide-induced oxidative stress and endocrine disruption may alter incretin-mediated signaling, thereby contributing to postprandial dysglycemia [11]. Mechanistically, chlorpyrifos exposure may disrupt incretin-mediated gut–pancreas signaling through pesticide-induced oxidative stress and endocrine dysfunction, potentially contributing to impaired postprandial glucose regulation [11].

Complementary endocrine interactions have been documented concerning pyrethroid metabolites. The prevalent urinary biomarker 3-phenoxybenzoic acid (3-PBA) has been shown to bind competitively to transthyretin, which in turn is associated with increased circulating free thyroid hormone concentrations in pregnancy. In a prospective cohort study of pregnant women, elevated urinary 3-PBA levels were significantly correlated with higher serum free T3 concentrations [27]. Alterations in thyroid hormone physiology may interact with maternal metabolic regulation, potentially influencing insulin resistance during gestation, as thyroid function and incretin sensitivity both contribute to glucose homeostasis in pregnancy [28]. Therefore, the disruption of endocrine communication due to pesticide exposure may intensify physiological insulin resistance during gestation and hasten the progression toward gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM). Therefore, disruption of endocrine communication due to pesticide exposure may intensify physiological insulin resistance during gestation and hasten the progression toward gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM).

1.4. Epigenetics and the Placenta

An expanding collection of research suggests that epigenetic reprogramming acts as a significant mediator in the metabolic dysfunction caused by pesticides, establishing a connection between maternal exposure and both immediate and transgenerational effects. In human subjects, prenatal contact with organophosphate and organochlorine substances correlates with modifications in the expression of DNA methyltransferases alongside genome-wide alterations in DNA methylation within metabolic genes, including IGF2, LEP, and PPARG, which are crucial for regulating fetal growth, adipogenesis, and insulin sensitivity [29,30]. In particular, Paul et al. (2018) documented variations in methylation across more than 600 CpG sites in individuals exposed to pesticides, suggesting involvement of immune and metabolic signaling pathways [28]. Likewise, Chen et al. (2024) found that gestational exposure to organophosphate esters altered placental methylation profiles in relation to the PPAR pathway, an essential regulator of lipid and glucose metabolism [29]. Pesticide-induced persistent organic pollutants like DDT and DDE lead to the generation of oxidative DNA damage and histone modification within the trophoblastic cells, thus changing the methylation status of imprinted loci involved in placental nutrient transport and placental growth restrictions [30]. These findings confirm evidence showing that placental methylation changes act as biomarkers reflecting maternal glycemic exposure and impact fetal metabolic programming [31]. Collectively, such studies suggest that gestational exposure to pesticides may lead to lasting epigenetic imprints on placental and fetal tissues that may be involved in the long-term postpartum insulin resistance in the mother and the passing of metabolic disease risk to subsequent generations [29,30,31].

2. Literature Review (Results)

2.1. Epidemiologic and Clinical Evidence (2000–2025)

Correlation between pesticide exposure and gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) has developed from scattered occupational findings in farm communities to complex biomonitoring studies involving several pesticide classes (Table 2). The first large-scale study, the United States Agricultural Health Study, proved that GDM risk was doubled in women with first-pregnancy occupational exposure to insecticides and herbicides compared with unexposed controls [31]. This study formed the basis of the hypothesis that pesticide exposure, and specifically exposure in agriculture, can disrupt glucose regulation during pregnancy.

Table 2.

Summary of epidemiologic and experimental studies assessing the association between pesticide exposure and gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM).

Extending this, the Canadian MIREC cohort presented the first biomarker-driven analysis, showing that higher levels of persistent organochlorine pollutants (p,p′-DDE, oxychlordane, and trans-nonachlor) were related to higher risk of GDM, whereas urinary organophosphate (OP) metabolites had variable trends following conferral for the intake of fruits and vegetables, indicating potential confounding by diet [15]. Likewise, in the Greek cohort study Rhea, related findings were reported: early-pregnancy exposure to polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and to DDT derivatives correlated with higher incidence of GDM, reasserting the diabetogenic role of lipophilic persistent organic pollutants (POPs) [12].

Over the past decade, focus has moved away from older legacy compounds to new, commonly used classes of pesticides. Chinese studies have shown that exposure to pyrethroids during pregnancy, measured by urinary 3-phenoxybenzoic acid (3-PBA), is positively correlated with fasting glucose, insulin resistance, and GDM diagnosis, especially with first-trimester exposure [27]. Supporting evidence indicates that 3-PBA is capable of binding to transthyretin and upregulating circulating free thyroid hormones, thereby disrupting metabolic adaptation in the mother [27,28].

Parallel findings have emerged for neonicotinoid insecticides (NNIs): a multicenter study from 2021 to 2025 identified elevated urinary or serum imidacloprid, acetamiprid, or thiamethoxam as being significantly associated with higher post-load glucose concentrations and nearly doubled GDM odds ratios, even after adjusting for BMI and maternal age [17] A metabolomic sub-study validated that exposure to NNI perturbed lipid and amino acid metabolism, implying that mitochondrial oxidative pathways related to insulin sensitivity were affected [18].

Recent biomonitoring evidence further demonstrated that combined exposure to multiple neonicotinoid insecticides was associated with increased GDM risk, with oxidative stress biomarkers partially mediating this association, suggesting a dose-dependent and biologically plausible exposure–response relationship [32].

There is still a dearth of evidence for fungicides and herbicides, while this topic is nonetheless interesting. Biomonitoring in North American and Latin American cohorts accounts for frequent detection of 2,4-D and dicamba in pregnant individuals, and Costa Rican reports associate combined chlorpyrifos and 2,4-D exposure with impaired fetal growth and glucose dysregulation [14,33]. Scant data, however, are focused on GDM endpoints per se, highlighting the necessity for serial, trimester-specific measurements.

Most importantly, a 2024 report demonstrated that individuals with minimal burdens of POPs and a Mediterranean-like diet had the lowest risk for GDM, while individuals with poor-quality diets and high exposure to pollutants had the highest risk, indicating a synergistic interaction between environmental exposure and nutrition [10]. Consistently and strongest across studies are the relationships between GDM and neonicotinoids and pyrethroids, and they are most evident with exposure during the first trimester, a stage that overlaps with crucial placental and pancreatic development. Legacy POPs and PCBs also remain with positive, albeit heterogeneous, relationships, with herbicide data forthcoming.

Recent large population-based studies, including the ELFE cohort and the Az-PEARS study, further support associations between prenatal pesticide exposure and gestational diabetes mellitus, with effect estimates varying by pesticide class, exposure window, and source of exposure [16,34]. Overall, the evidence underlines a multifaceted, multiclass chemical etiology of gestational dysglycemia, deserving further mechanistic investigation.

2.2. Experimental and Mechanistic Evidence

Mechanistic and translational studies contribute to plausibility for observational epidemiologic findings. Experimental studies have shown that several pesticide classes are endocrine-disrupting chemicals that can disrupt insulin signaling and glucose homeostasis by several convergent pathways. Organophosphate, pyrethroid, and organochlorine chemicals disrupt the insulin receptor substrate–PI3K–Akt pathway, resulting in blunted GLUT4 translocation in adipose and muscle tissues and increased hepatic gluconeogenesis [22,23]. These effects are mechanistically consistent with observations of insulin resistance in GDM. In addition, neonicotinoids like imidacloprid and acetamiprid reduce glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in β-cells in the pancreas, decrease expression of GLUT2, and induce mitochondrial impairment with release of cytochrome c and caspase-3 activation with β-cell apoptosis [24].

Oxidative stress and inflammation are another unifying mechanism. Pesticides increase reactive oxygen species (ROS), reduce antioxidant protection like superoxide dismutase and glutathione peroxidase, and activate NF-κB signaling with upregulation of inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β) [11,22,26]. This pathway disrupts insulin signaling and precipitates systemic inflammation, tipping pregnancy-associated insulin resistance. Pyrethroids and select OPs also dysregulate thyroid and incretin axes: pyrethroid metabolites displace thyroxine from transthyretin binding sites, elevating plasma free T3, whereas neonicotinoids and carbamates suppress GLP-1 and GIP secretion by intestinal L-cells, overall blunting postprandial glucose tolerance [27,28].

Emerging epigenetic evidence also links pesticide exposure with developmental causes of GDM. Human placental and cord-blood studies reveal that organophosphate exposure modifies DNA methylation of metabolic genes such as IGF2, LEP, and PPARG, whereas neonicotinoids and organochlorines affect histone acetylation and microRNA expression (particularly miR-29a/b) that reduce insulin-signaling genes [29,30]. These findings imply that pregnancy exposure to the environment can trigger lifelong epigenetic reprogramming of metabolic pathways, possibly leading to intergenerational transmission of risk for diabetes. Animal models reproduce these molecular events at the organismal level. In pregnant mice, simultaneous exposure to chlorpyrifos and permethrin induces fasting hyperglycemia, elevated TNF-α, reduced insulin signaling at the placental membrane, and fetal growth retardation consistent with GDM-like biology [23,26]. Similar outcomes are obtained with chronic exposure to neonicotinoids, reducing β-cell mass and hepatic lipid metabolism [35]. In particular, maternal neonicotinoid exposure has been shown to impair glucose metabolism by deteriorating brown adipose tissue thermogenesis, resulting in reduced energy expenditure and insulin sensitivity during pregnancy [35]. Altogether, mechanistic and experimental evidence points out that pesticide exposure can influence several biological systems—endocrine, metabolic, inflammatory, and epigenetic—to result in maternal insulin resistance and glucose intolerance characteristic of gestational diabetes.

3. Discussion

The present narrative review explored the link between pesticide exposure and the risk of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) through the inclusion of epidemiologic, mechanism-based, and nutrition-based perspectives. Incorporating evidence from studies between the year 2000 and the year 2025 suggests a new association between exposure to agricultural and dietary pesticides and the development of GDM, and in this way, introduces an environmental dimension into a condition that, traditionally, has been causally linked with metabolic and genetic factors.

3.1. Epidemiologic Evidence from 2000–2025

During the past two decades, converging epidemiologic evidence supports a credible link between pesticide exposure and GDM. Evidence stemming from research among agricultural and population-based community cohorts (i.e., non-occupationally exposed populations) in North America, Europe, and Asia indicates that both occupational and environmental pesticide exposures increase the risk of GDM [15,16,17,18,19]. The magnitude of such associations remains prominent following the adjustment for maternal age, body mass index, and socioeconomic factors and serves to strengthen the inference of an environmentally related causal component beyond the traditional metabolic risk factors. Biomonitoring studies also indicate that populations with simultaneous exposure to multiple pesticide classes, i.e., organophosphates, organochlorines, pyrethroids, and neonicotinoids, show cumulative increases in indicators of insulin resistance and glucose intolerance [10,15,16,18,19]. Geographic differences in exposure patterns underscore the role of dietary and agricultural determinants; remarkably, cohorts with strong adherence to vegetarian diets in populations with elevated pesticide residues in the diet show a clear exposure gradient, thus implicating diet as the major mode of contact [19]. Overall, the consistency, dose–response tendencies, and biological plausibility of these associations point toward an environmental contribution to the pathogenesis of GDM.

3.2. Mechanistic and Experimental Coherence

Mechanistic experiments confirm such epidemiological associations. In vitro and in vivo studies report that organophosphates, pyrethroids, and organochlorines interfere with the pathway of insulin by blocking the pathway of the insulin receptor substrate–PI3K–Akt pathway with consequent defective translocation of GLUT4 and increased hepatic gluconeogenesis [22,23,25]. Furthermore, some pesticide chemical groups also stimulate nuclear receptors such as PPAR-γ, consequently inducing ectopic lipid accumulation and hepatic resistance to insulin [34]. Neonicotinoids replicate such activities by β-cell mitochondrial injury, reduced secretion of insulin in response to glucose challenge, and apoptosis mediated through the release of cytochrome c and activation of caspase-3 [24,35].

Oxidative stress and inflammatory response are major unifying mechanisms connecting various chemical structures to identical metabolic endpoints. Pesticides induce the production of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species and inhibit antioxidant defenses and the activation of NF-κB and the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β), which accelerate systemic insulin resistance [11,22,26]. The thyroid and incretin signaling pathways represent additional targets; e.g., pyrethroid metabolites like 3-phenoxybenzoic acid bind to transthyretin with resultant elevated free T3 levels, while neonicotinoids and carbamates inhibit the secretion of GLP-1 and GIP with resultant disruption of the postprandial insulin responses [27,28].

Epigenetic reprogramming offers a mechanistic link between acute exposure and long-term metabolic dysregulation. Organophosphate and organochlorine exposure modulates DNA-methyltransferase activity to yield differential methylation of essential metabolic genes like IGF2, LEP, and PPARG [29,30,31]. Neonicotinoids induced histone-acetylation alterations and miR-29a/b-microRNA upregulation that suppress insulin-signaling transcripts [3]. The molecular findings are reflected in placental tissues obtained at term in exposed pregnancies, implying heritable or long-term epigenetic memory, implicating the risk of diabetes postpartum and across generations [31].

These aggregated datasets confirm that multiple subclasses of pesticides act on convergent biological mechanisms—endocrine disruption, oxidative stress, inflammatory signal transduction, and epigenetic regulation—to cause insulin resistance and β-cell dysfunction in agreement with GDM pathophysiology.

3.3. Nutritional Pathways and the Dual Burden of Exposure

Nutrition is both a determinant of metabolic resilience and an exposure vector for pesticides. Prospective cohorts invariably indicate that compliance with Mediterranean or high-quality diet patterns reduces GDM risk through higher insulin sensitivity and decreased oxidative burden [2,4,5,8]. Westernized diets with saturated fats and refined carbohydrates increase inflammation and oxidative burden [6,7]. Since fruits and vegetables are highly frequent pesticide transporters, the metabolic benefit of dietary plants may be blunted in areas with high agricultural chemical exposure. Cohorts with Mediterranean-type diets but also with elevated serum POP concentrations report the lowest GDM incidence, suggesting diet quality can buffer—but not eliminate—the negative impact of environmental exposure [10].

From the preventive standpoint, programs that promote careful selection and preparation of agricultural products can considerably reduce dietary pesticide exposure with retention of nutrient density [25]. Choice of lean meats and fish at low trophic levels limits the intake of lipophilic chemicals, such as organochlorines and PCBs [12]. Appropriate nutrient consumption—particularly antioxidants and dietary fiber—may also relieve oxidative and inflammatory outcomes related to exposure, exemplifying the integration of nutritional and toxicological mechanisms [9,11].

3.4. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Despite strong coherence, major methodological limitations remain. The majority of studies depend on single serum or urinary biomarkers reflecting short-term exposure at best and potentially masking trimester-specific vulnerability. Residual confounding by diet, adiposity, or socioeconomic context remains a concern, and diagnostic heterogeneity in GDM criteria complicates pooled analysis. Further, pesticide mixtures characteristic of real-world exposure are rarely studied in terms of interactive entities. Longitudinal biomonitoring throughout pregnancy in conjunction with standardized diagnostic endpoints and mixture-modeling approaches like Bayesian kernel machine regression or weighted quantile sum analysis should be adopted in future research. Integrative omics during pregnancy cohorts, such as the transcriptomic, metabolomic, and epigenomic profiling, will define molecular imprints of exposure and define causal pathways. The placental and β-cell organoid systems hold strong translational potential for mechanism validation.

3.5. Public Health Implications

The intersection of environmental toxicology, nutrition, and obstetric endocrinology carries major public health significance. Reductions in gestational pesticide exposure may offer population-level benefits, although the magnitude of such effects remains to be quantified. Antenatal counseling should combine dietary guidance for glycemic control with practical recommendations to minimize exposure—thorough washing of products, avoidance of domestic pesticide use, and preference for low-residue foods. Policy-level actions that support sustainable agriculture and enforce residue monitoring complement individual preventive measures. Epidemiologic consistency, mechanistic plausibility, and nutritional mutual dependency support the role of pesticide exposure as a potential environmental contributor to GDM. Even though established causality awaits future longitudinal confirmation, the aggregate evidence warrants precautionary approaches involving the combination of nutritional optimization with exposure diminution. Interdisciplinary research partnership will be essential in bringing this knowledge to beneficial maternal–child health interventions.

4. Materials and Methods

An extensive literature search was conducted across PubMed, Embase, and the Cochrane Library for records published from 1 January 2000 to December 2025. Search terms combined “fertilizers”, “herbicides”, and “pesticides” with “diabetes mellitus” and “gestational diabetes”. Human studies were included if they assessed GDM incidence/prevalence or pregnancy glycemia in relation to pesticide exposure (biomarkers, occupational/agricultural, or modeled ambient exposure). Experimental and mechanistic studies were included if they addressed insulin signaling, β-cell toxicity, oxidative or inflammatory stress, thyroid, incretin, or epigenetics relevant to pregnancy.

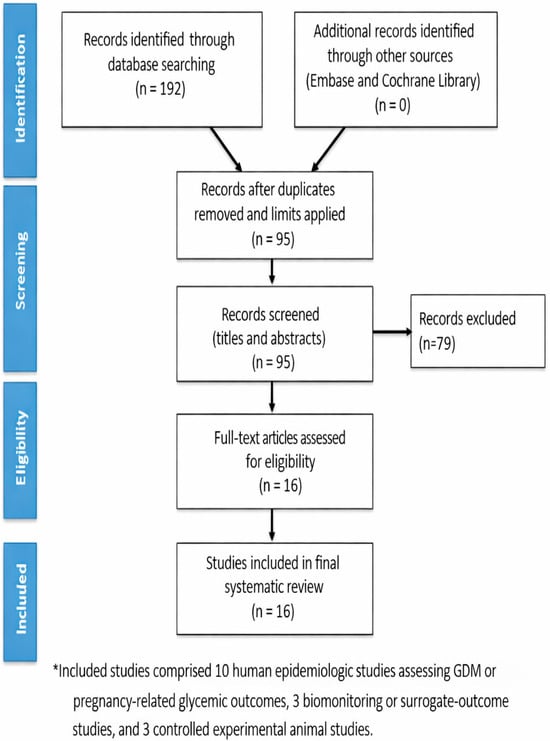

Titles and abstracts were screened. After duplicates were removed, 16 studies met the inclusion criteria (10 human epidemiologic studies assessing GDM or pregnancy-related glycemic outcomes, 3 biomonitoring or surrogate-outcome studies, and 3 controlled experimental animal studies) (Figure 1)

Figure 1.

Flow diagram illustrating the study selection process.

Table 2 summarizes epidemiologic studies evaluating clinically diagnosed GDM or validated pregnancy-related glycemic outcomes, as well as experimental animal studies modeling gestational exposure with maternal metabolic endpoints to support biological plausibility. Where available, adjusted effect estimates (odds ratios or relative risks with 95% confidence intervals) were extracted. For studies with continuous outcomes or experimental designs, effect estimates were reported as regression coefficients, percent changes, or mean differences, as appropriate.

5. Conclusions

Epidemiologic, experimental, and mechanistic evidence between 2000 and 2025 suggests that pesticide exposure, especially to neonicotinoids and pyrethroids during initial pregnancy, and work/agricultural exposure can increase GDM risk. Data on mechanisms through insulin resistance, β-toxicity, oxidative/inflammatory stress, thyroid/incretin perturbation, and epigenetics support biological plausibility. Despite the limitations of observational evidence, the public health imperatives are such that efforts to reduce exposure and expedite prospective, mixture-sensitive studies are needed to establish dose–response, critical periods, and prevention.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.P. and P.H.; methodology, C.P.; validation, P.T.; writing—original draft preparation, C.P.; writing—review and editing, P.T.; supervision, P.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| Akt | Protein kinase B |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| DDT | Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane |

| DDE | Dichlorodiphenyldichloroethylene |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic Acid |

| GDM | Gestational Diabetes Mellitus |

| GIP | Glucose-Dependent Insulinotropic Peptide |

| GLP-1 | Glucagon-Like Peptide 1 |

| GLUT2 | Glucose Transporter Type 2 |

| GLUT4 | Glucose Transporter Type 4 |

| IGF2 | Insulin-Like Growth Factor 2 |

| IL | Interleukin |

| IRS | Insulin Receptor Substrate |

| MIREC | Maternal–Infant Research on Environmental Chemicals (Cohort) |

| miR | MicroRNA |

| NF-κB | Nuclear Factor Kappa B |

| NNI | Neonicotinoid Insecticide |

| OP | Organophosphate |

| OCP | Organochlorine Pesticide |

| PCBs | Polychlorinated Biphenyls |

| PI3K | Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase |

| POPs | Persistent Organic Pollutants |

| PPAR-γ | Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Gamma |

| PPARG | Gene Encoding PPAR-γ |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| SFA | Saturated Fatty Acids |

| T3 | Triiodothyronine |

| T4 | Thyroxine |

| TLR4 | Toll-Like Receptor 4 |

| TNF-α | Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha |

| 3-PBA | 3-Phenoxybenzoic Acid |

| β-cell | Pancreatic Beta Cell |

References

- Choudhury, A.A.; Devi Rajeswari, V. Gestational diabetes mellitus—A metabolic and reproductive disorder. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 143, 112183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, X.; Zheng, Q.; Jiang, X.; Chen, X.; Liao, Y.; Pan, Y. The effect of diet quality on the risk of developing gestational diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Public Health 2023, 10, 1062304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cui, Y.; Liao, M.; Xu, A.; Chen, G.; Liu, J.; Yu, X.; Li, S.; Ke, X.; Tan, S.; Luo, Z.; et al. Association of maternal pre-pregnancy dietary intake with adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 63, 3430–3451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohtashaminia, F.; Hosseini, F.; Jayedi, A.; Mirmohammadkhani, M.; Emadi, A.; Takfallah, L.; Shab-Bidar, S. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet and risk of gestational diabetes: A prospective cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2023, 23, 647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tobias, D.K.; Zhang, C.; Chavarro, J.; Bowers, K.; Rich-Edwards, J.; Rosner, B.; Mozaffarian, D.; Hu, F.B. Prepregnancy adherence to dietary patterns and lower risk of gestational diabetes mellitus. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 96, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rogozińska, E.; Chamillard, M.; Hitman, G.A.; Khan, K.S.; Thangaratinam, S. Nutritional manipulation for the primary prevention of gestational diabetes mellitus: A meta-analysis of randomised studies. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0115526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Karamanos, B.; Thanopoulou, A.; Anastasiou, E.; Assaad-Khalil, S.; Albache, N.; Bachaoui, M.; Slama, C.B.; El Ghomari, H.; Jotic, A.; Lalic, N.; et al. Relation of the Mediterranean diet with the incidence of gestational diabetes. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 68, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ojo, O.; Ojo, O.O.; Adebowale, F.; Wang, X.H. The Effect of Dietary Glycaemic Index on Glycaemia in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Nutrients 2018, 10, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Basiri, R.; Seidu, B.; Cheskin, L.J. Key Nutrients for Optimal Blood Glucose Control and Mental Health in Individuals with Diabetes: A Review of the Evidence. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, G.; Pang, W.W.; Yang, J.; Guivarch, C.; Grewal, J.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, C. The Interplay of Persistent Organic Pollutants and Mediterranean Diet in Association with the Risk of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care 2024, 47, 2239–2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sun, C.; Shen, J.; Fang, R.; Huang, H.; Lai, Y.; Hu, Y.; Zheng, J. The impact of environmental and dietary exposure on gestational diabetes mellitus: A comprehensive review emphasizing the role of oxidative stress. Front. Endocrinol. 2025, 16, 1393883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Vafeiadi, M.; Roumeliotaki, T.; Chalkiadaki, G.; Rantakokko, P.; Kiviranta, H.; Fthenou, E.; Kyrtopoulos, S.A.; Kogevinas, M.; Chatzi, L. Persistent organic pollutants in early pregnancy and risk of gestational diabetes mellitus. Environ. Int. 2017, 98, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.C.; Cohn, B.A.; Cirillo, P.M.; Santella, R.M.; Terry, M.B. DDT exposure during pregnancy and DNA methylation alterations in female offspring in the Child Health and Development Study. Reprod Toxicol. 2020, 92, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Daggy, J.K.; Haas, D.M.; Yu, Y.; Monahan, P.O.; Guise, D.; Gaudreau, É.; Larose, J.; Benbrook, C.M. Dicamba and 2,4-D in the Urine of Pregnant Women in the Midwest: Comparison of Two Cohorts (2010–2012 vs. 2020–2022). Agrochemicals 2024, 3, 42–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, G.D.; Dodds, L.; Arbuckle, T.E.; Ashley-Martin, J.; Ettinger, A.S.; Fisher, M.; Taback, S.; Bouchard, M.F.; Monnier, P.; Dallaire, R.; et al. Exposure to organophosphorus and organochlorine pesticides, perfluoroalkyl substances, and polychlorinated biphenyls in pregnancy and the association with impaired glucose tolerance and gestational diabetes mellitus: The MIREC Study. Environ. Res. 2016, 147, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guesdon, L.; Warembourg, C.; Chevrier, C.; de Lauzon-Guillain, B.; Caudeville, J.; Charles, M.A.; Le Lous, M.; Blanc-Petitjean, P.; Béranger, R. Maternal exposure to pesticides and gestational diabetes mellitus in the Elfe cohort. Environ. Res. 2025, 284, 122275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, D.; Zhou, L.; Mu, C.; Lin, M.; Sheng, Y.; Xu, Y.; Huang, D.; Liu, S.; Zeng, X.; Chongsuvivatwong, V.; et al. Effects of neonicotinoid pesticide exposure in the first trimester on gestational diabetes mellitus based on interpretable machine learning. Environ. Res. 2025, 273, 121168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, J.; Liu, Q.; Geng, S.; Mu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Miao, M.; Dai, Y.; Hu, L. Serum neonicotinoid insecticides levels and gestational diabetes mellitus: Mediation by plasma metabolomic alterations. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 384, 126965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.; Pan, X.F.; Miao, M.; Guo, H.; Meng, P.; Huang, W. Exposure to a Multitude of Environmental Chemicals During Pregnancy and Its Association with the Risk of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Toxics 2025, 13, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhang, B.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Dai, Y.; Ding, J.; Zhou, X.; Qi, X.; Wu, C.; Zhou, Z. Prenatal exposure to neonicotinoid insecticides, fetal endocrine hormones and birth size: Findings from SMBCS. Environ. Int. 2024, 193, 109111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrestha, S.; Singh, V.K.; Sarkar, S.K.; Shanmugasundaram, B.; Jeevaratnam, K.; Koner, B.C. Effect of sub-toxic chlorpyrifos on redox sensitive kinases and insulin signaling in rat L6 myotubes. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord. 2018, 17, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Xiao, X.; Kim, Y.; Kim, D.; Yoon, K.S.; Clark, J.M.; Park, Y. Permethrin alters glucose metabolism in conjunction with high fat diet by potentiating insulin resistance and decreases voluntary activities in female C57BL/6J mice. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2017, 108, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wei, F.; Cheng, F.; Li, H.; You, J. Imidacloprid affects human cells through mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress. Sci. Total. Environ. 2024, 951, 175422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wołejko, E.; Łozowicka, B.; Jabłońska-Trypuć, A.; Pietruszyńska, M.; Wydro, U. Chlorpyrifos Occurrence and Toxicological Risk Assessment: A Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Djekkoun, N.; Depeint, F.; Guibourdenche, M.; El Khayat El Sabbouri, H.; Corona, A.; Rhazi, L.; Gay-Queheillard, J.; Rouabah, L.; Hamdad, F.; Bach, V.; et al. Chronic Perigestational Exposure to Chlorpyrifos Induces Perturbations in Gut Bacteria and Glucose and Lipid Markers in Female Rats and Their Offspring. Toxics 2022, 10, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Normann, S.S.; Ma, Y.; Andersen, H.R.; Valente, M.J.; Renko, K.; Arnold, S.; Jensen, R.C.; Andersen, M.S.; Vinggaard, A.M. Pyrethroid exposure biomarker 3-phenoxybenzoic acid (3-PBA) binds to transthyretin and is positively associated with free T3 in pregnant women. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2025, 264, 114495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazarus, J. Thyroid Regulation and Dysfunction in the Pregnant Patient. [Updated 21 July 2016]. In Endotext [Internet]; Feingold, K.R., Adler, R.A., Ahmed, S.F., Eds.; MDText.com, Inc.: South Dartmouth, MA, USA, 2000. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279059/?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Paul, K.C.; Chuang, Y.H.; Cockburn, M.; Bronstein, J.M.; Horvath, S.; Ritz, B. Organophosphate pesticide exposure and differential genome-wide DNA methylation. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 645, 1135–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chen, Y.; Huang, B.; Liang, H.; Ji, H.; Wang, Z.; Song, X.; Zhu, H.; Song, S.; Yuan, W.; Wu, Q.; et al. Gestational organophosphate esters (OPEs) exposure in association with placental DNA methylation levels of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) signaling pathway-related genes. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 947, 174569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardenas, A.; Gagné-Ouellet, V.; Allard, C.; Brisson, D.; Perron, P.; Bouchard, L.; Hivert, M.F. Placental DNA Methylation Adaptation to Maternal Glycemic Response in Pregnancy. Diabetes 2018, 67, 1673–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saldana, T.M.; Basso, O.; Hoppin, J.A.; Baird, D.D.; Knott, C.; Blair, A.; Alavanja, M.C.; Sandler, D.P. Pesticide exposure and self-reported gestational diabetes mellitus in the Agricultural Health Study. Diabetes Care 2007, 30, 529–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mahai, G.; Wan, Y.; Wang, A.; Qian, X.; Li, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, W.; He, Z.; Li, Y.; Xia, W.; et al. Exposure to multiple neonicotinoid insecticides, oxidative stress, and gestational diabetes mellitus: Association and potential mediation analyses. Environ. Int. 2023, 179, 108173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Wendel de Joode, B.; Peñaloza-Castañeda, J.; Mora, A.M.; Corrales-Vargas, A.; Eskenazi, B.; Hoppin, J.A.; Lindh, C.H. Pesticide exposure, birth size, and gestational age in the ISA birth cohort, Costa Rica. Environ. Epidemiol. 2024, 8, e290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Parra, K.L.; Harris, R.B.; Farland, L.V.; Beamer, P.; Fournier, A.J.; Ellsworth, P.C.; Furlong, M. Prenatal exposure to agricultural pesticide applications and gestational diabetes mellitus in the Az-PEARS population-based study (2014–2020). Environ. Int. 2025, 207, 109989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, W.; Fang, J.; Ji, C.; Zhong, H.; Zhong, T.; Cui, X. Maternal neonicotinoid pesticide exposure impairs glucose metabolism by deteriorating brown fat thermogenesis. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2025, 290, 117596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.