Abstract

This narrative review of rapid eye movement (REM) focuses on its primary etiology and how it fits into the larger framework of neurophysiology and general physiology. Arterial blood flow in the retina may be sensitive to the full overlying ‘weight’ of its adjacent and contiguous vitreous humor caused by the humoral mass effect in the Earth’s gravitational field. During waking hours of the day, this ‘weight’ is continuously shifted in position due to changing head position and eye movements associated with ordinary environmental observations. This reduces its impact on any one point on the retinal field. However, during sleep, the head may maintain a relatively constant position (often supine), and observational eye movements are minimal, leaving essentially one retinal area exposed at the ‘bottom’ of each eye, relative to gravity. During sleep, REM may provide a mechanism for frequently repositioning the retina with respect to the weight it incurs from its adjacent (overlying) vitreous humor. Our findings were consistent with the intermittent terrestrial nocturnal development of ‘gravitational ischemia’ in the retina, wherein the decreased blood flow is accompanied metabolically by decreased oxygen tension, a critically important metric, with a detrimental influence on nerve-related tissue generally. However, the natural mechanisms for releasing and resolving gravitational ischemia, which likely involve glymphatics and cerebrospinal fluid shifts, as well as REM, may gradually fail in old age. Concurrently associated with old age in some individuals is the deposition of alpha-synuclein and/or tau in the retina, together with similar deposition in the brain, and it is also associated with the development of Parkinson’s disease and/or Alzheimer’s disease, possibly as a maladaptive attempt to release and resolve gravitational ischemia. This suggests that a key metabolic parameter of Parkinson’s disease and Alzheimer’s disease may be a lack of oxygen in some neural tissues. There is some evidence that oxygen therapy (hyperbaric oxygen) may be an effective supplemental treatment. Many of the cardinal features of spaceflight-associated neuro-ocular syndrome (SANS) may potentially be explained as features of gravity opposition physiology, which becomes unopposed by gravity during spaceflight. Gravity opposition physiology may, in fact, create significant challenges for humans involved in long-duration space travel (long-term microgravity). Possible solutions may include the use of artificial gravitational fields in space, such as centrifuges.

1. Introduction

Rapid eye movements (REMs) are quick, darting movements of the eyes, of moderate amplitude, that occur under closed eyelids during the REM stage of sleep [1].

Working at the University of Chicago in 1953, Eugene Aserinsky and Nathaniel Kleitman discovered REM sleep and linked it to dreaming. Their work was largely based on observations of infants, and it established that sleep is not a uniform state neurologically but rather consists of distinct and differing stages. In a 1953 paper [2], these two researchers were the first to describe specific eye movements during sleep, which were ‘rapid and jerky’.

More than two dozen species of land mammals have been studied by electroencephalography (EEG) and found to experience REM sleep. Details regarding the duration of sleep cycles have varied from one species to another.

In humans, REM sleep is believed by some to promote brain development in infants, consolidate memories, and process emotional experiences in adults. During this stage of sleep, the brain typically becomes very active, with intense dreaming, and the body’s large muscles are temporarily paralyzed to prevent the acting out of dreams. REM is also believed to help with mood regulation, creativity, and maintaining neural pathways. But the primary etiology of REM is unknown.

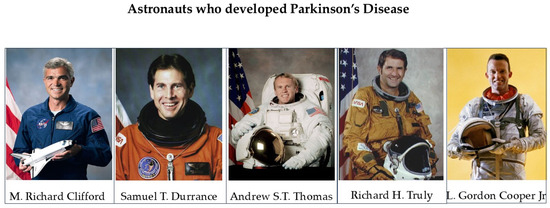

REM sleep abnormalities have been linked to both Parkinson’s disease and Alzheimer’s disease. Parkinson’s disease has recently been observed to have an increased incidence among former astronauts (Figure 1) [3,4,5,6,7]. This observation, together with other recent physiological research, has suggested the involvement of gravity in sleep, Parkinson’s disease [8,9,10,11], Alzheimer’s disease, and REM.

Figure 1.

Astronauts who developed Parkinson’s disease [3,4,5,6,7]. During the Space Shuttle era (1981–2011), five participating US/Australian astronauts, initially active before the mid-1990s, later announced publicly [3,4,5,6,7] that they had been diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease (astronauts Clifford, Durrance, Thomas, Truly, and Cooper), anecdotally suggesting a significantly higher incidence of Parkinson’s disease in astronauts than in the general population.

2. Methods and Focus

For this study of REM, we drew on research findings obtained from the clinical sciences, as well as from pathology, radiology, and public spaceflight medical data. We included a variety of research papers, which, when taken together, suggested that during sleep, gravity may significantly reduce blood flow in some parts of the retina by creating a stratified compressive mass effect from neighboring eye structures that are overlying during sleep.

These reports were consistent with the possibility that REM may provide a release from this ‘gravitational ischemia’ in the retina. Finally, we attempted to place REM within the overall context of ‘gravity opposition physiology’, those characteristics of terrestrial (on-Earth) physiology that withstand gravitational forces.

3. Gravity and Weight on the Earth’s Surface

Medical issues involving ‘gravity and weight’ have historically been somewhat common. ‘Weight-bearing joints’ (hips and knees) can experience ischemic injury to chondrocytes and cartilage, resulting from compressive stress and strain from the mass effect of the upper body (head, thorax, and abdomen) sitting on the joints as a weight burden. The ‘bone-on-bone’ joint pathology, which can characterize osteoarthritis, results from nearly complete destruction of cartilage [12].

4. Clues Regarding the Primary Etiology of REM

Although REM is believed to possibly play a role in memory, mood, and dreaming, these are considered by most investigators to be secondary roles. Since the discovery of REM sleep around 1953, a significant amount of research has been undertaken to characterize its frequency and duration and its association with some diseases. But the most important etiological clues about REM sleep may be how it is altered in astronauts during spaceflight.

5. Normal REM Sleep

In normal terrestrial (on-Earth) adult sleep architecture, REM sleep makes up about 25% of the total sleep time, occurring in cycles that lengthen as the night progresses. The night begins with non-REM (NREM) sleep, and the first REM stage is short, lasting only a few minutes. Subsequent REM stages can last for up to an hour, with the longest periods of REM occurring in the last third of the night.

During REM sleep, the eye movements are rapid and disjunctive (disconjugate), meaning that the two eyes frequently do not move in alignment with each other. They can be misaligned horizontally and/or vertically by up to 30 degrees.

Normal terrestrial REM latency in adults is generally 70 to 120 min. This is the time it takes to enter the first REM stage of sleep after falling asleep.

6. Sleeping in Space

Spaceflight investigators have reported that astronauts on the Mir Space Station experienced a one-hour increase in wakefulness during each 24 h sleep/wake cycle compared with on Earth, and that upon return to Earth, their sleep architecture returned to its usual preflight characteristics [13]. The loss of one hour of sleep per 24 h by the astronauts was characterized in detail using results from a Nightcap sleep-monitoring device to measure REM sleep and NREM sleep components. The participating astronauts were five males, with an average age of 43, who each spent approximately 6 months at the Russian space station during the time frame of 1996–1998.

The spaceflight investigators further cited several sources that agreed that ‘Humans sleep significantly less in space compared with on Earth [13]’. They then mentioned that ‘Surprisingly, REM latency decreased by nearly 30 min compared with preflight’. In their discussion, they mentioned that ‘Still, it is unclear why REM latency would be altered during spaceflight’.

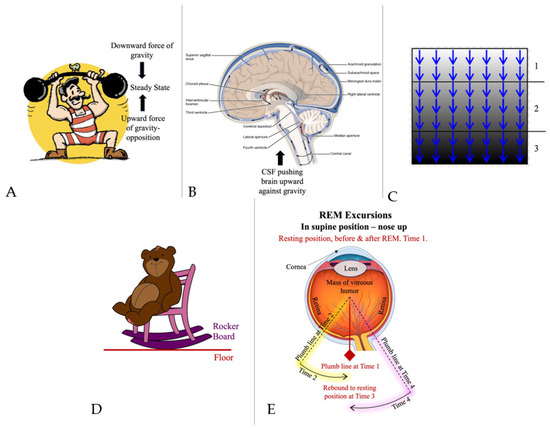

As background, the spaceflight investigators [13] cited a previous observation that ‘Sleep is regulated by the build-up of homeostatic sleep pressure and the circadian rhythm, which promotes wakefulness during the day and allows for consolidated sleep at night´ [14]. Together with another more recent source [15], this provides a mechanistic pathway for downstream events resulting in sleep, but it does not suggest an upstream primary etiology or underlying cause for sleep (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Gravity opposition physiology in the brain. (A) Context given through cartoons. Steady state between the downward force of gravity and the upward force of gravity opposition. From Pixabay, under Pixabay License. (B) Flow of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) (green arrows), buoying the brain, and pushing the brain ‘upward’ against gravity by entering the subarachnoid space at the ‘bottom’ of the cranial vault and being removed at the ‘top’ (in vertical head position). CSF outlet apertures (median and lateral, in yellow boxes) are positioned for CSF to fill various basilar cisterns (including the chiasmatic cistern) from the ventricular system, where CSF is produced in the choroid plexus. We have referred to this positioning of CSF outlets together with this configuration of CSF flow as being one component of ‘gravity opposition physiology’. We have identified other components as well. In microgravity (in space), gravitational ischemia in the brain does not occur. But regional ischemia may still form around the cortical vertex due to the upwardly directed forces of gravity opposition physiology, compressing brain tissue there against the interior of the skull vertex. During prolonged spaceflight, reabsorption of CSF at the superior sagittal sinus via arachnoid granulations may be partially obstructed due to increased pressure from upward brain shifting. This may result in a backup of the entire CSF system with increased CSF pressure in basilar cisterns (yellow boxes) and the chiasmatic cistern, which receive CSF via the foramina of Magendie and Luschka, resulting in optic disc edema in some cases. Pressure backup into the ventricular system may be the cause of dilation there. Details of this mechanism remain to be resolved and confirmed. Adapted from Wiki-Media Commons, with Creative Commons licensing [16]. (C) Schematic stratification of a biological tissue (brain, eye, and skin) into horizontal pancaking layers under the influence of gravity. Lower layers incur progressively increasing weight burden from upper layers, thus increasing compression of blood vessels and reduction in blood flow, possibly resulting in regional ischemia. (1) Top 2 horizontal layers, where normal gravitational ischemia has been largely released/resolved. (2) Middle 3 horizontal layers, where normal gravitational ischemia has gradually developed over time, waiting to be released by repositioning. (3) Bottom 2 horizontal layers, where gravitational ischemia has become pathologically severe following failure of normal release mechanisms, predisposing to Parkinson’s disease and other conditions. Details of this mechanism remain to be resolved and confirmed. From Wiki-Media Commons, with Creative Commons Licensing. (D) Gravity opposition physiology in the eye. Context given through cartoons. When the rocking chair is in motion, the interface between the curved rocker board and the floor is continuously moving, not allowing gravitational pressure to develop at any one point. From Pixabay, under Pixabay License. (E) Rapid eye movements (REMs). Although the retina interfaces continuously with its underlying choroid and sclera, the point of maximal gravitational impact (plumb line) on retinal blood vessels swings back and forth during REM, not allowing it to develop significantly at any one point. Details of this mechanism remain to be resolved and confirmed. From Wiki-Media Commons, with Creative Commons Licensing [17].

7. Gravity

Other reports [18,19] have provided observations that could explain why sleeping less in space may have an underlying etiology related to gravity, and specifically to gravitational ischemia in both the brain and the retina. On Earth, the ‘top half’ of the brain, in any given position, is sitting on the ‘bottom half’ as a weight burden, compressing blood vessels there, possibly attenuating blood flow and inducing regional ischemia, with symptoms including sleepiness, inattentiveness, generalized decreased skeletal motor activity, and yawning [20]. This gravitational ischemia, being reversible within certain limits, may be released and resolved by changes in head position, such as becoming horizontal for sleep after being vertical while awake (Figure 2). Details of this mechanism remain to be resolved and confirmed.

If left uncorrected, the weight burden causing gravitational ischemia may, over time, slowly exceed arterial pressure in the most affected regions. This is analogous to a bedridden hospitalized patient, who may develop dermal ischemia throughout the buttocks and sacral region, eventually resulting in skin breakdown and decubitus ulcers, with areas of infarction and necrosis, requiring frequent body repositioning by nursing staff. This is consistent with the observation that humans rarely spend more than 24 consecutive hours in an alert vertical position before succumbing to a horizontal resting position. In the case of REM, it may be its analogous rotation of position that refocuses gravity and releases gravitational ischemia in the retina. Volitional eye movements occur continuously during the waking hours of the day, preventing gravitational ischemia. Ischemia is characterized primarily by reduced blood flow and reduced oxygen tension.

8. Spaceflight and Gravity Opposition Physiology in Astronauts

Some of the possible contributions of gravitational ischemia in the brain to normal terrestrial physiology may be inferred by observing what happens when gravity is removed. Spaceflight may reveal the most immediate, prominent, and least integrated of the brain’s natural counterforces to gravity, which find themselves suddenly unopposed. Like a collection of coiled springs, accustomed to maintaining resistance against gravity, these physiological processes may be the most available and noticeable when gravity is suddenly removed. They occur in the brain and in the eyes as gravity opposition physiology.

Gravity on Earth acts continuously on the brain and on both eyes, with each of the three responding as a separate globe. In any body position, the top half of each globe sits on its bottom half as a weight burden [18,19]. REM sleep is initially decreased in duration during spaceflight [20], suggesting a feedback loop. Sleep, as well, is decreased during spaceflight, also suggesting a feedback loop. In both cases, gravitational ischemia does not accumulate within either the brain or the eyes, as it would on Earth, because gravity is essentially absent, reducing the need for both sleep and REM, to the extent that they are mechanisms for releasing and resolving gravitational ischemia by shifting weight away from ischemic areas. In spaceflight, their occurrence is reduced, as there is less physiological need for them to occur.

Medical examination of astronauts following spaceflights during the Space Shuttle era (1981–2011) increased our collective awareness that our terrestrial physiology may be significantly influenced by the Earth’s gravitational field.

In 2017, a medical report of astronauts returning from spaceflight compared their post-flight findings with pre-flight examination results, specifically regarding magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and other testing of the brain and eyes [21]. It concluded that an upward shifting of the brain and narrowing of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) spaces at the vertex occurred frequently and predominantly in astronauts after long-duration flights [19]. Long-duration flights are generally longer than 150 days. This upward brain shifting is believed to cause spaceflight-associated brain white matter microstructural changes and intracranial fluid redistribution [22], which could involve the frontal eye fields of the brain, through which eye movements are mediated. MRI also demonstrated lateral ventricle enlargement.

Gravity opposition physiology appears to affect the brain in space in largely the same way that gravity affects the brain on Earth: only in reverse. Instead of gravity pushing the brain of a standing terrestrial man downward, toward the base of his skull, in space, his brain is being actively pushed upward by the configuration of CSF flow, which was teleologically ‘intended’ to prevent the brain from being smashed into the skull base while on Earth, but in space, this is unopposed by gravity.

That is possibly why 80 percent of sleep is preserved in space, compared with on Earth. The cortical brain vertex is the new stress region [21], as opposed to the base of the brain. Also, there are likely many other metabolic, non-gravitational functions of sleep that work to preserve it.

Following a rocket launch, terrestrial gravity affecting the astronauts rapidly turns into microgravity. Gravity opposition physiology then takes over for gravity as the new force which generates compressive extravascular ischemia in the brain, producing (unopposed) ‘gravity opposition ischemia in space’. Research findings [20] further indicate that long-duration exposure to microgravity may alter the CSF/interstitial fluid circulation in the perivascular spaces, possibly impairing cerebral drainage systems like the glymphatic pathways and highlighting the importance of a gravitationally maintained brain fluid homeostasis (Figure 2B).

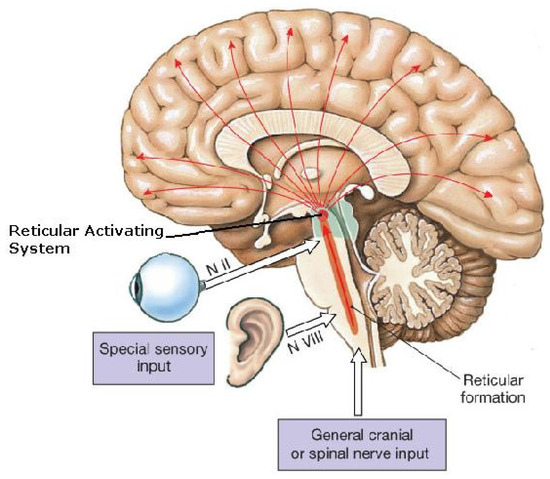

Yet sleep is primarily an electrical event, separate from gravitational ischemia in the brain, which is more of a ‘plumbing problem’. Sleep may possibly occur as an evolutionary terrestrial response, teleologically ‘intended’ to cause someone to lie down, assuming a horizontal body position [15,23,24] for the purpose of releasing gravitational ischemia in the brain. And in space, the brain cortical vertex ischemia may induce electrical sleep by influencing the terminal cortical portion of the reticular activating system (RAS) (Figure 3), even though the ischemia may not respond to any changes in position (while in microgravity). In normal terrestrial physiology, the brainstem components of the RAS are influenced to initiate sleep.

Figure 3.

Reticular activating system (RAS).The reticular activating system (RAS) includes sites of cortical arousal (activation, causing wakefulness, and/or deactivation, causing sleep) (red arrow tips). Scattered multi-focal cortical sites (red arrow tips) are deactivated (causing sleep) by projections from brainstem components of the RAS (possibly resulting from gravitational ischemia in the brainstem on Earth). But in microgravity, those cortical sites may be deactivated (causing sleep) more directly by the cortical ischemia resulting from the regional pressure applied through gravity opposition physiology, which pushes the brain toward the skull vertex (sagittal suture), causing compression there. N = nerve. Adapted from Wiki-Media Commons, with Creative Commons licensing [25].

9. Sleep and REM

From another perspective, why do sleep and REM occur at all in space, if they are controlled by a feedback loop, and if there is no need for them to occur in the absence of gravitational ischemia?

In microgravity (in space), gravitational ischemia in the brain does not occur. But regional ischemia may still form around the cortical vertex due to the upwardly directed forces of gravity opposition physiology, compressing brain tissue and blood vessels there against the interior of the skull (Figure 2B).

Why does REM come early when sleeping in space? (i.e., why is REM latency decreased?) CSF pressure is increased around the basilar cisterns and chiasmatic cistern due to gravity opposition physiology. This results in the brain shifting in position toward the skull vertex, as seen in post-flight MRI scans. It also results in papilledema, a principal feature of spaceflight-associated neuro-ocular syndrome (SANS) [26,27,28,29,30]. The same pressure feedback mechanism that decreased REM duration when there was reduced weight from the vitreous humor on the retina in microgravity now induces earlier onset of REM due to pressure from the optic nerve head. On Earth, pressure on the retina comes ‘through the front door’ from vitreous pressure caused by gravity. In space, pressure on the retina comes ‘through the back door’ from increased CSF pressure at the optic nerve head via the chiasmatic cistern, caused by gravity opposition physiology. However, the REM response in space is non-physiological and ineffective in reducing retinal ischemia, and this could become a problem. Gravity, as a force, is external to the human body, and the body is influenced differently with changes in body position relative to gravity (Figure 4). Gravity opposition physiology, as a force, is internally located, so in microgravity, it is unaffected by changes in body position in space.

Recent reports suggest a translational electrophysiology in the brain, from neuronal ischemia to neuronal transmission. Basic science investigators used animal studies to test a large swath of ischemia in the brain created by brief transient episodes of cerebrovascular occlusion [31]. Electrical activity was generated from the involved neurons and was associated with neuroprotection. The model of brief episodic cerebrovascular occlusion used by investigators approximately mimics the regional ischemia caused by gravity in the brain. The investigators also studied reperfusion injury, which mimics the release of gravitational ischemia by repositioning the head in a gravitational field [23,31]. Their data suggest that shifting regions of gravitational ischemia over a 24 h period may work like a hydroelectric dam to generate enough neuronal transmission to provide the electrical requirements of sleep. Another report [24] suggests that these electrical changes may be harmful in some situations, capable of causing sudden, unexpected death.

The conversion of regional ischemia (gravitational ischemia in the brain) and reperfusion injury (from releasing gravitational ischemia in the brain) into electrical phenomena (like sleep) now seems plausible. Although we are very far from understanding the neurophysiology of sleep, and even why it occurs, spaceflight is providing some interesting data, much of which is related to changes in gravity.

In normal terrestrial physiology, the multifocal cortical sleep-inducing mechanisms are triggered by projections from the RAS in the brainstem (resulting from gravitational ischemia there). But in microgravity, those mechanisms may be triggered more directly by the cortical ischemia resulting from the pressure applied through gravity-opposition physiology (Figure 2). However, sleeping in space may not release or resolve the cortical pressure resulting from gravity-opposition physiology. And this may remain a problem for long-duration space travel.

Some answers to these questions might eventually come from a different physiological construct. Other investigators have recently reported research findings obtained from a different, but likely relevant, perspective: parabolic flight as a simulation of microgravity as well as hypergravity [32]. This different configuration of gravitational forces and sleep timing, relative to actual spaceflight, might provide data that could be used to back-test the specific role of gravity opposition physiology.

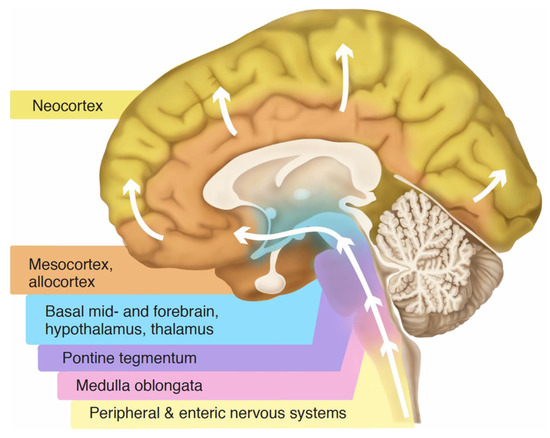

Figure 4.

Braak staging. Sequential layering in an upright brain, from the bottom up (white arrows), by Lewy bodies in Parkinson’s disease, suggests a horizontal sedimentary stratification, appearing to be influenced by gravity over time. The optic nerve and retina, not shown in the graphic, are involved at the mid-level. Adapted from Wikimedia Commons, with Creative Commons licensing [33].

But why does REM occur at all during sleep in space? The subarachnoid space, containing CSF, is continuous along the entire course of the optic nerve, exposing all sides of the optic nerve to CSF. However, at certain times of day, during certain postural changes, parts of the subarachnoid space around the optic nerve may collapse in a patchy configuration to become simply potential spaces around the optic nerve. These potential spaces may possibly be returned to being actual spaces containing CSF by REM. This process may be activated by yawning [20].

REM may intermittently (with each darting movement) exert traction on the optic nerve, stretching it in different directions to allow the flow of CSF along the entire course of the nerve, as opposed to it being sequestered at a few blocked-off areas. Gravity opposition physiology pushes CSF from the chiasmatic cistern into the back side of the retina [34]. The pressure differential across the optic nerve head may be maintained by REM in such a way as to facilitate retinal blood flow and, ultimately, vision.

10. Retinal Responses to Gravity: Sleep Deprivation vs. Microgravity

Parkinson’s disease acquired during spaceflight is potentially the flip side of terrestrial Parkinson’s disease, and an examination of retinal involvement is important, as it may reflect the etiology of REM.

Retina investigators recently reported [35] that terrestrial patients with Parkinson’s disease often have tortuous arteries in the retinal superior temporal quadrant, which may be an early biomarker for the disease. To a lesser degree, the superior nasal retinal field may also exhibit tortuous arteries, while the overall venous circulation remains unaffected [35].

Regarding the origin and etiology of the tortuosities, they cite research findings in their introduction [35] suggesting that Parkinson’s may be preceded, or even caused, by neurovascular abnormalities in the brain, which seem to be ‘distinct from’ those causing strokes and traditional cerebrovascular disease, and suggesting that the retinal tortuosities they observed may possibly reflect this in some way [35]. Their study was carried out using ultra-widefield (UWF) scanning laser ophthalmoscopy.

Concurrently, pathology investigators elsewhere [36] looked at post-mortem eyes (N = 99) that were collected prospectively through the Netherlands Brain Bank from donors who had ‘Parkinson’s disease with dementia’, and ‘dementia with Lewy bodies’, as well as other neurodegenerative diseases, and non-neurological controls. Multiple retinal and optic nerve cross-sections were immunostained with anti-alpha-synuclein antibodies [36]. Their findings [36] were more often positive in the superior half of the retinas of Parkinson’s patients post-mortem, analogous to the location of arterial tortuosities reported by the retina investigators [35]. The pathology investigators [36], however, did not break down their findings into superior temporal vs. nasal quadrants.

Possibly relevant, as well, was the finding that in normal terrestrial physiology, the superior retinal hemisphere receives significantly more blood flow than the inferior hemisphere [37]. This finding is from a study that did not segregate out subjects with a congenitally present cilioretinal artery (30% of the population), which significantly localizes to the superior temporal retinal quadrant and is associated with better outcomes following some ischemic events.

This may be an evolutionary adaptation to protect the blood circulation in the superior temporal retinal quadrant, which is exposed to gravitational ischemia during NREM sleep, when the eyes are typically rotated up and out, rolling the superior temporal retinal quadrant into the ‘bottom’ position, when sleeping in a supine position with the nose up. Because the superior and inferior retinal fields exhibit this physiological difference, some newly occurring pathological events may produce a differential response between them.

This may also be relevant to the development of SANS in long-duration spaceflight. The increased blood flow may have a protective effect against ischemia associated with the increased CSF pressure, which is likely associated with the development of papilledema. Not all astronauts have developed papilledema, and this may partially explain why.

A recent research project [38,39] concluded that pulsatile motion in the CSF of the chiasmatic cistern, related to the circle of Willis arteries, is associated with a normally functioning visual–neural circuitry. Conversely, a relatively quiet, non-pulsatile chiasmatic cistern is associated with Parkinson’s disease—a neurological illness characterized by numerous visual abnormalities [38,39]. The reasons appear to be related to the CSF pressure, specifically within the chiasmatic (suprasellar) cistern, and its adverse effect on blood perfusion pressure, specifically within the chiasm itself, as well as in the optic nerves [38,39]. This new MRI method for assessing the chiasmatic cistern characterizes some CSF circulation disruptions as being associated with alpha-synuclein retention [38,39]. Higher CSF pressure in the chiasmatic cistern may, ultimately, constrict blood flow in the retina, causing ischemia there [38,39,40]. And another novel MRI study [41], specifically evaluating cerebral arteries in Parkinson’s patients, has reported hemodynamic abnormalities potentially consistent with the tortuosities in retinal arteries.

Gravity acts continuously on the brain and on both eyes, each of the three as a separate globe. In any body position, the top half of each globe sits on its bottom half as a weight burden [42]. Blood vessels toward the bottom are compressed by external pressure on their individual vascular walls from the overlying mass, reducing blood flow, resulting in a gradient of ischemia, consistent with the variation in weight of overlying mass throughout the globe (Figure 2A–C). The brain is most severely affected by this ‘gravitational ischemia’ in a vertical, standing position during the 16 waking hours of the day [42]. The eyes are most impacted by gravitational ischemia during sleep while in a horizontal supine position with the nose up, with the greatest impact being on the retina. During a standing position, the eyes are protected from the weight of the brain by shelving effects of the orbital roof, and during sleep, the retina incurs the additional compressive forces of both eyelid weight and traction. The difference between the brain and the eye is largely related to their movements (or lack of movement (brain)) and to the shelving effects of bony structures of the skull, as well as dural structures, such as the falx and cerebellar tentorium. The brain is entirely still, except for pulsations of blood vessels and CSF. Overall, gravitational ischemia is ‘distinct from’ typical cerebrovascular disease, which causes ischemia and strokes mostly by intravascular stenosis and occlusion [42].

In old age, the brain incurs changes in stiffness and elasticity [42,43], which may cause a deterioration of its ability to release gravitational ischemia with positional changes (from standing vertical to lying horizontal) [44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51]. In a maladaptive manner, alpha-synuclein may be deposited to release gravitational ischemia in the brain by increasing blood–brain barrier (BBB) permeability [10,11] (Figure 2C).

Some physiology of the eye seems targeted to oppose gravity by releasing gravitational ischemia. This may include rapid eye movements (REMs). The relative jerkiness of REM ‘churns’ blood through the vasculature (like a washing machine in the agitation cycle) to release gravitational ischemia, in addition to changing the focal point of the maximum impact of gravity (Figure 2D,E). To be clear, the eye (or the brain, or the skin) is never free from gravitational ischemia, which is simply moved from one area to another by position changes [42].

An under-appreciated factor in gravitational ischemia may be morphometric and volumetric changes in the lacrimal gland associated with various diseases and physiological states [52]. The lacrimal gland is situated in the superior temporal aspect of the anterior orbit. Its weight and compressive pressure from swelling may potentially have a significant impact on the superior temporal retinal field. Common variants in lacrimal size and morphology may also be underappreciated [53].

A recent case report [54] illustrates the power of gravity to damage a biological system by weaponizing adjacent body parts when appropriate gravity opposition mechanisms are not in place. A 44-year-old man who had taken a prescribed sleeping medication and alcohol lost consciousness in a position that allowed the mass of his head (passively), under the force of gravity, to compress his left eye from the anterior toward the posterior. With his normal response to pain obtunded by medication, he incurred a serious eye injury from gravitational ischemia. The case report [54] and the chiasmatic CSF research [38,39] describe largely the same physiological process. One went through the front door [54], and the other went through the back door [38,39], to cause ischemic retinopathy.

Gravity opposition physiology may similarly protect the brain from the bony skull base as CSF enters the subarachnoid space at the brain base and is withdrawn at the apex (arachnoid granulations) [38,39,42], buoying up the brain, and consistent with the MRI observations of astronauts, revealing an upward lifting of the brain when gravity is removed (Figure 2B).

And research suggests that some manifestations of gravity opposition physiology may be intensified following a failure of others to release gravitational ischemia in the brain, going into overdrive attempting to overcome the resistance of releasing gravitational ischemia in the brain [38]. However, the CSF flow and pressure physiology between the brain and the eye has not yet been fully characterized and is likely pertinent here. Some research suggests that the optic nerve subarachnoid space is largely collapsed while standing in a vertical position to protect the eye from increased hydrostatic pressure [55]. And since standing in a gravitational field is not relevant in outer space (microgravity), this may be consistent with the development of optic disc edema there. Pertinent, as well, may be the yet unclarified association of Parkinson’s with non-arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy [56].

Taken together, these reports suggest that the retinal arterial tortuosities found in Parkinson’s patients by the retina investigators [35] are likely primarily ischemic in origin, related to reduced blood flow and reduced oxygen tension in some region of the brain or of the eye, or both. In part, they may be related directly to gravitational ischemia, or to gravity opposition physiology, or simply to more secondary or tertiary responses to those two (i.e., collateral damage). The tortuosities may result from persistent arteriolar constriction in an auto-regulatory attempt to increase retinal perfusion pressure in the setting of decreased blood flow (ischemia) associated with compartmentally increased CSF pressure in the chiasmatic cistern. At this time, a preponderance of research evidence suggests that although there may be elements of inflammatory and immune mechanisms scattered throughout this multi-step process, involving neurovascular changes, vascular endothelial dysfunction [23], and alpha-synuclein deposition, the retinal arterial tortuosities result primarily from an ischemic event, likely driven by gravity.

11. Final Observations

REM does not occur in isolation, and there are potentially four other takeaways from this review.

- Gravity opposition physiology may, in fact, create significant challenges for humans involved in long-duration space travel (long-term microgravity). Possible solutions may include the use of artificial gravitational fields in space, such as centrifuges. Astronauts may not require such facilities continuously, but rather only at space stations.

- If gravitational ischemia (Figure 5) is a problem in terrestrial physiology [46,47], and if Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s diseases are physiologically maladaptive responses in old age, then oxygen delivery of some sort may possibly play a role in resolving those neurodegenerative diseases, as a decreased level of parenchymal oxygen tension may be the primary concern [9,57,58,59].

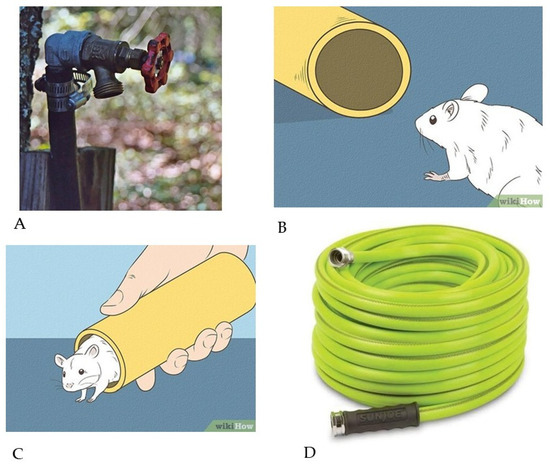

Figure 5. Gravitational ischemia in the brain and in the eye. The story of the mouse and the garden hose. (A) Once upon a time, Mr. Joe Schmoe was standing in his front yard with a long garden hose, watering his shrubbery. After he had finished, he detached the garden hose from the spigot near his house. He then set the hose on the ground and walked away. (B) Some water drained out of the hose, which created a space for a mouse passing by to enter the hose and spend the night, unbeknownst to Mr. Schmoe. The next day, Mr. Schmoe reattached the hose to the spigot and began to water his shrubs. The water flow through the hose was only about half of its usual rate and pressure. (C) Mr. Schmoe detached the hose from the spigot to make sure that he had a normal water flow and pressure coming from the spigot. He did, but he then noticed a small mouse emerging from the end of the garden hose, looking stunned. The mouse then quickly scampered away from Mr. Schmoe’s front yard, vowing never to return. (D) Just then, a truck carrying a load of garden hoses and fertilizer bags drove by Mr. Schmoe’s house and accidentally spilled its cargo onto his front yard. Dozens of coiled garden hoses landed directly on top of Mr. Schmoe’s garden hose, together with small bags of fertilizer. Unable to move the load, Mr. Schmoe proceeded to water his shrubbery with his own garden hose, which was lying underneath the others. The water flow rate and pressure were unchanged from when the mouse had been in his garden hose, about half of normal. Just then, a group of doctors, who were walking down the street, stopped by to ask what was happening. Mr. Schmoe told them, and the doctors then ‘re-inflated’ Mr. Schmoe’s garden hose by filling it with X-ray dye under pressure. They then took X-rays of his garden hose, which showed it to be entirely clean on the inside and open to flow. The graphic images have Creative Commons licensing.

Figure 5. Gravitational ischemia in the brain and in the eye. The story of the mouse and the garden hose. (A) Once upon a time, Mr. Joe Schmoe was standing in his front yard with a long garden hose, watering his shrubbery. After he had finished, he detached the garden hose from the spigot near his house. He then set the hose on the ground and walked away. (B) Some water drained out of the hose, which created a space for a mouse passing by to enter the hose and spend the night, unbeknownst to Mr. Schmoe. The next day, Mr. Schmoe reattached the hose to the spigot and began to water his shrubs. The water flow through the hose was only about half of its usual rate and pressure. (C) Mr. Schmoe detached the hose from the spigot to make sure that he had a normal water flow and pressure coming from the spigot. He did, but he then noticed a small mouse emerging from the end of the garden hose, looking stunned. The mouse then quickly scampered away from Mr. Schmoe’s front yard, vowing never to return. (D) Just then, a truck carrying a load of garden hoses and fertilizer bags drove by Mr. Schmoe’s house and accidentally spilled its cargo onto his front yard. Dozens of coiled garden hoses landed directly on top of Mr. Schmoe’s garden hose, together with small bags of fertilizer. Unable to move the load, Mr. Schmoe proceeded to water his shrubbery with his own garden hose, which was lying underneath the others. The water flow rate and pressure were unchanged from when the mouse had been in his garden hose, about half of normal. Just then, a group of doctors, who were walking down the street, stopped by to ask what was happening. Mr. Schmoe told them, and the doctors then ‘re-inflated’ Mr. Schmoe’s garden hose by filling it with X-ray dye under pressure. They then took X-rays of his garden hose, which showed it to be entirely clean on the inside and open to flow. The graphic images have Creative Commons licensing. - During long-term space flight, gravity opposition physiology remains unopposed and induces its own regional ischemia in the brain (near the skull vertex) and in the retina (associated with papilledema). These may potentially be addressed, in part, by using an increased ambient ‘fraction of inspired oxygen’ (FiO2) in the spacecraft [60]. An interesting historical note is that some of the earliest astronauts breathed near-100% oxygen, until the Apollo 1 launch-pad explosion at Cape Kennedy in 1967 killed all three astronauts onboard.

- Many of the cardinal features of SANS may potentially be explained as features of gravity opposition physiology, which become unopposed by gravity during spaceflight.

11.1. The Story of the Mouse and the Garden Hose

Once upon a time, Mr. Joe Schmoe was standing in his front yard with a long garden hose, watering his shrubbery. After he had finished, he detached the garden hose from the spigot near his house (Figure 5A). He then set the hose on the ground and walked away. Some water drained out of the hose, which created a space for a mouse passing by to enter the hose and spend the night, unbeknownst to Mr. Schmoe (Figure 5B). The next day, Mr. Schmoe reattached the hose to the spigot and began to water his shrubs. The water flow through the hose was only about half of its usual rate and pressure. Mr. Schmoe detached the hose from the spigot to make sure that he had a normal water flow and pressure coming from the spigot. He did, but he then noticed a small mouse emerging from the end of the garden hose, looking stunned. The mouse then quickly scampered away from Mr. Schmoe’s front yard, vowing never to return (Figure 5C).

Just then, a truck carrying a load of garden hoses (Figure 5D) and fertilizer bags drove by Mr. Schmoe’s house and accidentally spilled its cargo onto his front yard. Dozens of coiled garden hoses landed directly on top of Mr. Schmoe’s garden hose, together with small bags of fertilizer. Unable to move the load, Mr. Schmoe proceeded to water his shrubbery with his own garden hose, which was lying underneath the others. The water flow rate and pressure were unchanged from when the mouse had been in his garden hose, about half of normal. Just then, a group of doctors, who were walking down the street, stopped by to ask what was happening. Mr. Schmoe told them, and the doctors then ‘re-inflated’ Mr. Schmoe’s garden hose by filling it with X-ray dye under pressure. They then took X-rays of his garden hose, which showed it to be entirely clean on the inside and open to flow. The doctors then handed Mr. Schmoe the X-ray pictures together with an invoice for USD 1,000, and they told him that everything was fine, as they resumed their walk down the street. But everything was not fine. The water flow through Mr. Schmoe’s garden hose was only half of its normal volume and pressure; at the same time, there was a load of garden hoses sitting on top of it. What could be wrong? Did the group of doctors not see the load of hoses? How is that possible?

11.2. Welcome to the History of Medicine (The Story of How We May Have Gotten to This Place)

During the 1800s, an infectious disease called syphilis was very prominent in the medical world. European investigators were studying blood vessels in the brains of deceased patients who, during life, had exhibited bizarre neurological symptoms (like Wallenberg syndrome). On the inside of the arteries, they found inflammatory lesions, which partially obstructed blood flow (like the mouse in the garden hose in Figure 5).

Even before the advent of X-rays, generations of doctors came of age considering ischemic vascular disease (which reduces blood flow) to be essentially synonymous with occlusive or stenotic vascular disease. Their mindset was that if blood flow was reduced within the anatomical distribution or perfusion territory of a group of blood vessels, then that reduction must have been caused by partial or complete blockages inside one or more of the blood vessels, analogous to the mouse in the garden hose (Figure 5).

And the passage of decades, and changes in the medical environment, did not alter this thought process. During World War II, the availability of penicillin led to a precipitous decline in syphilis. But the epidemiological importance of syphilis for causing vascular disease would very shortly be replaced by cigarette smoking and its accompanying atherosclerosis, as millions of GIs returned home from war, many with a pack of cigarettes in a shirt breast pocket [27].

Fast forward to the 21st century. Modern medicine was built on the concept that, epidemiologically, reduced blood flow through an artery is caused by a blockage in the artery (a mouse in the garden hose). Instances of blood vessels incurring outside pressure were known to occur but were considered to be uncommon, such as when a brain abscess pushed against the outside of a blood vessel. That was the thought process. It was ‘correct’, but it considered only half of the picture.

Today, gravity in the brain is considered by some to be an important cause of ischemia there. This regional ischemia may occur in parenchymal brain tissue surrounding blood vessels located at the bottom of the brain, at the bottom of a pile of other blood vessels filled with blood and surrounded by parenchymal neural tissue. This is analogous to Mr. Schmoe’s garden hose at the bottom of a pile of other garden hoses (Figure 5D).

This physiologically normal and reversible ischemia, accompanied by both decreased blood flow and lower oxygen levels, occurs when the bottom blood vessels (like the garden hose) are squeezed (compressed) under the pressure of the collective weight of those above it. Gravitational ischemia is not caused by a mouse in the garden hose (Figure 5). Gravitational ischemia in the brain and in the eyes is a central phenomenon underlying gravity opposition physiology and the disturbances it may cause during spaceflight.

At autopsy, the brain of a deceased adult weighs about 3 pounds. That does not sound like a lot of weight. But from the perspective of a small blood vessel sitting at the base (bottom) of the brain, those 3 pounds of weight are significant, and at autopsy, they are not filled with blood, which would create additional weight. The load of garden hoses and fertilizer bags simply represents the entire brain, with all of its many blood vessels (Figure 5).

Ironically, this view of ischemia sees gravitational ischemia (a component of normal terrestrial physiology) as extremely common in its occurrence compared with stenotic or occlusive ischemia, which, in comparison, is uncommon. The retina is part of the central nervous system, and it may be best studied in the context of the brain, especially in light of alpha-synuclein and tau accumulating in both structures preceding Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s diseases.

Within the Earth’s gravitational field, the ‘bottom’ of the brain (together with its meninges) is typically sandwiched (and squeezed) between its underlying skull bone and its overlying brain parenchyma, together with its dense vasculature. Similarly, during sleep, a particular area of the retina is located at the ‘bottom’ of the eye, which, together with its soft vascular choroid, is sandwiched (and squeezed) between its underlying dense firm sclera and its overlying avascular vitreous body.

In the story shown in Figure 5, there was no difference in the water flow through the garden hose (analogous to cerebral perfusion pressure) when it was partially obstructed internally by the mouse, compared with when it was externally constricted by the overlying garden hoses and bags of fertilizer. This is a central theme of gravitational physiology. What remains unknown is the percentage of blood flow that is lost and the specific brain and eye regions where ischemia occurs.

12. Conclusions

- In normal terrestrial physiology, the superior retinal hemisphere receives significantly more blood flow than the inferior hemisphere. This includes the influence of the cilioretinal artery (which is congenitally present in 30% of the population), which significantly localizes to the superior temporal retinal quadrant. This may be an evolutionary adaptation to protect the blood circulation in the superior temporal retinal quadrant, which is exposed to gravitational ischemia during sleep, when the eyes are typically rotated up and out, rolling the superior temporal retinal quadrant into the ‘bottom’ position, when sleeping in a supine position with the nose up.

- Some of the possible contributions of gravitational ischemia in the brain to normal terrestrial physiology may be inferred by observing what happens when gravity is removed. Spaceflight may reveal the most immediate, prominent, and least integrated of the brain’s natural counterforces to gravity, which find themselves suddenly unopposed. Gravity on Earth acts continuously on the brain and on both eyes, with each of the three responding as a separate globe.

- In microgravity (in space), gravitational ischemia in the brain does not occur. But regional ischemia may still form around the cortical vertex due to the upwardly directed forces of gravity opposition physiology, compressing brain tissue and blood vessels there against the interior of the skull. This may itself induce sleep by directly triggering terminal cortical receptors in the RAS. But this sleep may be non-physiological and ineffective at releasing or resolving the regional brain ischemia associated with gravity opposition physiology. This could create an unfavorable situation for astronauts.

- Essentially, all humans and land mammals experience disconjugate eye twitching for a couple of hours every night during sleep, and no one knows why. This phenomenon is called REM.

- The primary physiological (teleological) purpose of REM may be to mitigate gravitational ischemia in the retina.

13. Acknowledging Weaknesses in Our Narrative Review

Our paper extends the concept of ‘gravitational ischemia’ from the brain to the retina without accounting for anatomical differences, which are significant. Specifically, regarding vasculature, the retina is a thin layer of neural tissue with its own vasculature. Its underlying choroidal layer is very vascular and provides circulatory assistance to the retina. Its overlying vitreous is essentially non-vascular.

The concept of ‘gravitational ischemia’ is focused on a theoretical point in space, within either the brain or retina, which is infinitely small and dimensionless. It simply incurs the weight of overlying body tissue, which, in the case of the brain, is other brain tissue, and in the case of the retina, is mostly vitreous humor. The overlying mass is considered simply as weight, essentially as if it were Silly Putty. This may seem in conflict with Figure 2C, which implies a large, relatively homogeneous vascular structure (the brain). It may also seem in conflict with the garden hose story, which calls attention to the weight of the overlying vasculature. But, in fact, each layer in Figure 2C is simply a collection of points with a different amount of overlying mass. In the case of the retina, the different layers would look more like a three-dimensional bowl (retina) filled with Silly Putty (vitreous humor), transected by a superimposed stack of horizontal planes, analogous to the two-dimensional lines in Figure 2C. The bowl (retina) would have some thickness, although a narrow one. Many pieces of the retinal bowl would have a small amount of overlying retina and a large amount of overlying vitreous humor.

Direct experimental data regarding this topic are very limited. Data from spaceflight have been very helpful but are also limited, especially to the general public. Nonetheless, it may be beneficial to at least frame the conversation regarding a primary etiology for REM and let others contribute to it in the future.

- In Figure 1, we note an increased incidence of Parkinson’s disease among astronauts. We characterize this as ‘anecdotal’, without including numerical data regarding sample size and terrestrial incidence for comparison. As of 2025, the total number of astronauts and cosmonauts who have participated in long-duration spaceflight is approximately 300. There is no public access to the vast majority of medical records regarding these participants. Of the very few who have publicly announced health issues subsequent to spaceflight, we have noticed what we consider to be a high prevalence of Parkinson’s disease. But we have not comprehensively organized all of these data. Refs. [3,4,5,6,7] are only public announcements of disease presence in each astronaut.

- Figure 5 and the garden hose story depiction of gravitational ischemia ignore the complex vascular physiology, such as autoregulation, and the blood–brain barrier. It is simply a metaphor, but, as such, we tried to use it to focus our readers’ attention on relationships that might easily be overlooked. Our history of medicine was similarly limited and focused.

- In this paper, we explored uncharted territory. We sought an answer to the following questions: ‘What is the primary causation and etiology of REM’? ‘Why do our eyeballs twitch intermittently at night while we sleep’? In the vast ocean of the medical literature, very few investigators have considered these questions at all. No one seems to know where to start. We would like to frame a conversation around this topic.There is little real data from anywhere that reflects directly on this topic. But spaceflight is producing medical data about the brain, sleep, and REM from a place where life is very different from what we know on Earth, because of a very limited number of variables, mostly the Earth’s gravitational and magnetic fields. Conditions like a ‘lack of atmosphere’ are mostly secondary.The early stages of exploration are going to consist largely of trying to stitch together half-truths and ‘maybe-relationships’. There is no low-hanging fruit in sight. Still, the question is important enough to motivate us forward. Problems revolving around ischemia can potentially be mitigated by something fairly simple and available: oxygen.And this set of problems regarding gravity, ischemia, and REM is interfacing with another set of problems regarding Parkinson’s disease, involving both the brain and the eyes, arterial tortuousities, and evidence of preceding cerebrovascular disease, involving the blood–brain barrier, glymphatics, and complex immune phenomena. It is at least plausible that problems involving the release and resolution of gravitational ischemia could be at play in this mix.

- The cause of the alpha-synuclein/tau deposition associated with Parkinson’s disease and Alzheimer’s is largely unknown but is under intense investigation. A large body of research involving human pathological specimens and animal models has produced results from which many inferences can be made, although nothing has been conclusively demonstrated. Among the inferences is the possibility that ischemia and reduced neural oxygen tension may play a role in the etiology of either or both neurodegenerative diseases.

- This narrative review did not systematically evaluate alternative functions of REM. Most of what is described in the literature is secondary functions associated with memory and abnormal REM physiology, such as REM behavioral disorder. We also did not discuss possible non-gravitational causes of astronaut neurodegeneration, such as radiation exposure.

- We used Wikipedia graphics for illustrative purposes only, and not to substantiate information.

- We cited direct spaceflight measurements of sleep times compared with direct terrestrial measurements in the same astronauts (13). The numbers varied from one night to the next, and from one astronaut to another. Overall, the duration of time (in hours) spent sleeping in space per 24 h cycle is less than the typical nightly sleep duration on Earth. We characterized it as 80%.

- We conclude by mentioning several very recent publications regarding various aspects of this topic [61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70]. Although none directly addresses the conclusions of our paper, they each contribute significantly to the mosaic of information that currently serves as our foundation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.H.J.; methodology, G.O.; software, G.O.; validation, J.H.J., J.O. and G.O.; formal analysis, J.H.J.; investigation, J.H.J.; resources, J.H.J.; data curation, J.H.J.; writing—original draft preparation, G.O.; writing—review and editing, J.O.; visualization, J.O.; supervision, G.O.; project administration. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

J. Howard Jaster is an employee of London Corporation, the other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Rosenblum, Y.; Jafarzadeh Esfahani, M.; Adelhöfer, N.; Zerr, P.; Furrer, M.; Huber, R.; Roest, F.F.; Steiger, A.; Zeising, M.; Horváth, C.G.; et al. Fractal Cycles of Sleep, a New Aperiodic Activity-Based Definition of Sleep Cycles. Elife 2025, 13, RP96784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aserinsky, E.; Kleitam, N. Regularly Occurring Periods of Eye Motility, and Concomitant Phenomena, during Sleep. Science 1953, 118, 273–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikipedia. Michael R. Clifford. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Michael_R._Clifford (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Wikipedia. Samuel T. Durrance. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Samuel_T._Durrance (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Wikipedia. Andy Thomas. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Andy_Thomas (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- The New York Times. Richard Truly, 86, Dies; Shuttle Astronaut Who Went on to Lead NASA. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2024/03/07/science/space/richard-truly-dead.html (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Leroy, G.J. New Mexico Museum of Space History. Available online: https://nmspacemuseum.org/inductee/leroy-g-cooper-jr/#content (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Ali, N.; Beheshti, A.; Hampikian, G. Space Exploration and Risk of Parkinson’s Disease: A Perspective Review. NPJ Microgravity 2025, 11, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaster, J.H.; Ottaviani, G. Gravitational Ischemia in the Brain: How Interfering with Its Release May Predispose to Either Alzheimer’s- or Parkinson’s-like Illness, Treatable with Hyperbaric Oxygen. Physiologia 2023, 3, 510–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, Y.Y.; Wu, C.-Y.; Yu, D.; Kim, E.; Wong, M.; Elez, R.; Zebarth, J.; Ouk, M.; Tan, J.; Liao, J.; et al. Biofluid Markers of Blood-Brain Barrier Disruption and Neurodegeneration in Lewy Body Spectrum Diseases: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Park. Relat. Disord. 2022, 101, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, J.; Milenkovic, I.; Kovacs, G.G. Patterns of Tau and α-Synuclein Pathology in the Visual System. J. Parkinsons. Dis. 2015, 5, 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Ning, E.; Lu, L.; Zhang, H.; Yang, X.; Hao, Y. Effectiveness of Low-Intensity Pulsed Ultrasound on Osteoarthritis: Molecular Mechanism and Tissue Engineering. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1292473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piltch, O.; Flynn-Evans, E.E.; Young, M.; Stickgold, R. Changes to Human Sleep Architecture during Long-duration Spaceflight. J. Sleep Res. 2025, 34, e14345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borbély, A.A. A Two Process Model of Sleep Regulation. Hum. Neurobiol. 1982, 1, 195–204. [Google Scholar]

- Sawada, T.; Iino, Y.; Yoshida, K.; Okazaki, H.; Nomura, S.; Shimizu, C.; Arima, T.; Juichi, M.; Zhou, S.; Kurabayashi, N.; et al. Prefrontal Synaptic Regulation of Homeostatic Sleep Pressure Revealed through Synaptic Chemogenetics. Science 2024, 385, 1459–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikipedia. Cerebrospinal Fluid. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cerebrospinal_fluid#/media/File:1317_CFS_Circulation.jpg (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Wiki-Media. Commons Iris Retina. Available online: https://www.edupointbd.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/iris-retina.png (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Jaster, J.H. Gravitational Ischemia in the Brain—May Explain Why We Sleep, and Why We Dream. AME Med. J. 2021, 6, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaster, J.H. Gravity in the Brain-How It May Regulate Skeletal Muscle Metabolism by Balancing Compressive Ischemic Changes in the Weight-Bearing Pituitary and Hypothalamus. Physiol. Rep. 2021, 9, e14878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walusinski, O. How Yawning Switches the Default-Mode Network to the Attentional Network by Activating the Cerebrospinal Fluid Flow. Clin. Anat. 2014, 27, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, D.R.; Albrecht, M.H.; Collins, H.R.; Asemani, D.; Chatterjee, A.R.; Spampinato, M.V.; Zhu, X.; Chimowitz, M.I.; Antonucci, M.U. Effects of Spaceflight on Astronaut Brain Structure as Indicated on MRI. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 1746–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barisano, G.; Sepehrband, F.; Collins, H.R.; Jillings, S.; Jeurissen, B.; Taylor, J.A.; Schoenmaekers, C.; De Laet, C.; Rukavishnikov, I.; Nosikova, I.; et al. The Effect of Prolonged Spaceflight on Cerebrospinal Fluid and Perivascular Spaces of Astronauts and Cosmonauts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2120439119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaster, J.H. Gravity in the Brain: How Compressive Ischemic Changes in the Weight-Bearing Brainstem Autonomic Nuclei May Contribute to Vascular Endothelial Dysfunction Elsewhere in the Body Following Sleep Deprivation. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2021, 320, H1415–H1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaster, J.H. Reperfusion Injury to Ischemic Medullary Brain Nuclei after Stopping Continuous Positive Airway Pressure-Induced CO2-Reduced Vasoconstriction in Sleep Apnea. J. Thorac. Dis. 2018, 10, S2029–S2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiki-Media. Commons RAS: Reticular Activating System. Available online: https://rcweb.dartmouth.edu/CANlab/brainstemwiki/doku.php/ras.html (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Ong, J.; Tavakkoli, A.; Zaman, N.; Kamran, S.A.; Waisberg, E.; Gautam, N.; Lee, A.G. Terrestrial Health Applications of Visual Assessment Technology and Machine Learning in Spaceflight Associated Neuro-Ocular Syndrome. NPJ Microgravity 2022, 8, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, J.; Tarver, W.; Brunstetter, T.; Mader, T.H.; Gibson, C.R.; Mason, S.S.; Lee, A. Spaceflight Associated Neuro-Ocular Syndrome: Proposed Pathogenesis, Terrestrial Analogues, and Emerging Countermeasures. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2023, 107, 895–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, J.; Waisberg, E.; Masalkhi, M.; Kamran, S.A.; Lowry, K.; Sarker, P.; Zaman, N.; Paladugu, P.; Tavakkoli, A.; Lee, A.G. Artificial Intelligence Frameworks to Detect and Investigate the Pathophysiology of Spaceflight Associated Neuro-Ocular Syndrome (SANS). Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, J.; Jang, K.J.; Baek, S.J.; Hu, D.; Lin, V.; Jang, S.; Thaler, A.; Sabbagh, N.; Saeed, A.; Kwon, M.; et al. Development of Oculomics Artificial Intelligence for Cardiovascular Risk Factors: A Case Study in Fundus Oculomics for HbA1c Assessment and Clinically Relevant Considerations for Clinicians. Asia-Pacific J. Ophthalmol. 2024, 13, 100095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiroz-Reyes, M.A.; Quiroz-Gonzalez, E.A.; Quiroz-Gonzalez, M.A.; Lima-Gomez, V. Effects of Cigarette Smoking on Retinal Thickness and Choroidal Vascularity Index: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Retin. Vitr. 2025, 11, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Xu, J.; Chen, Y.; Xu, Q.; Zhang, W.; Hu, B.; Li, A.; Zhu, Q. Electrophysiological Signatures in Global Cerebral Ischemia: Neuroprotection Via Chemogenetic Inhibition of CA1 Pyramidal Neurons in Rats. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2024, 13, e036146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Roy, B.; Jouvencel, A.; Friedl-Werner, A.; Renel, L.; Cherchali, Y.; Osseiran, R.; Sanz-Arigita, E.; Cazalets, J.-R.; Guillaud, E.; Altena, E. Is Sleep Affected after Microgravity and Hypergravity Exposure? A Pilot Study. J. Sleep Res. 2025, 34, e14279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikipedia. Braak Staging. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Braak_staging#/media/File:BraakStagingbyVisanjiEtAl.png (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Jaster, J.H.; Ong, J.; Ottaviani, G. Visual Motion Hypersensitivity, from Spaceflight to Parkinson’s Disease-as the Chiasmatic Cistern May Be Impacted by Microgravity Together with Normal Terrestrial Gravity-Opposition Physiology in the Brain. Exp. Brain Res. 2024, 242, 521–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.P.; Robbins, C.B.; Pead, E.; McGrory, S.; Hamid, C.; Grewal, D.S.; Scott, B.L.; Trucco, E.; MacGillivray, T.J.; Fekrat, S. Ultra-Widefield Imaging of the Retinal Macrovasculature in Parkinson Disease Versus Controls with Normal Cognition Using Alpha-Shapes Analysis. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 2024, 13, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart de Ruyter, F.J.; Morrema, T.H.J.; den Haan, J.; Gase, G.; Twisk, J.W.R.; de Boer, J.F.; Scheltens, P.; Bouwman, F.H.; Verbraak, F.D.; Rozemuller, A.J.M.; et al. α-Synuclein Pathology in Post-Mortem Retina and Optic Nerve Is Specific for α-Synucleinopathies. NPJ Park. Dis. 2023, 9, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomita, R.; Iwase, T.; Ueno, Y.; Goto, K.; Yamamoto, K.; Ra, E.; Terasaki, H. Differences in Blood Flow Between Superior and Inferior Retinal Hemispheres. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2020, 61, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierobon Mays, G.; Hett, K.; Eisma, J.; McKnight, C.D.; Elenberger, J.; Song, A.K.; Considine, C.; Richerson, W.T.; Han, C.; Stark, A.; et al. Reduced Cerebrospinal Fluid Motion in Patients with Parkinson’s Disease Revealed by Magnetic Resonance Imaging with Low b-Value Diffusion Weighted Imaging. Fluids Barriers CNS 2024, 21, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mays, G.P.; Hett, K.; Eisma, J.; McKnight, C.D.; Elenberger, J.; Song, A.K.; Considine, C.; Han, C.; Stark, A.; Claassen, D.O.; et al. Reduced Suprasellar Cistern Cerebrospinal Fluid Motion in Patients with Parkinson’s Disease Revealed by Magnetic Resonance Imaging with Dynamic Cycling of Diffusion Weightings. Res. Sq. 2023; preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossinelli, D.; Fourestey, G.; Killer, H.E.; Neutzner, A.; Iaccarino, G.; Remonda, L.; Berberat, J. Large-Scale in-Silico Analysis of CSF Dynamics within the Subarachnoid Space of the Optic Nerve. Fluids Barriers CNS 2024, 21, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, L.; Wu, Y.; Lv, X.; Xu, Y.; Dou, W.; Zhang, H.; Wu, J.; Shang, S. Intracerebral Hemodynamic Abnormalities in Patients with Parkinson’s Disease: Comparison between Multi-Delay Arterial Spin Labelling and Conventional Single-Delay Arterial Spin Labelling. Diagn. Interv. Imaging 2024, 105, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaster, J.H.; Ottaviani, G. Gravity-Induced Ischemia in the Brain-and Prone Positioning for COVID-19 Patients Breathing Spontaneously. Acute Crit. Care 2022, 37, 131–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, H.; Kurt, M.; Zeng, N.; Ozkaya, E.; Marcuz, F.; Wu, L.; Laksari, K.; Camarillo, D.B.; Pauly, K.B.; Wang, Z.; et al. MR Elastography Frequency-Dependent and Independent Parameters Demonstrate Accelerated Decrease of Brain Stiffness in Elder Subjects. Eur. Radiol. 2020, 30, 6614–6623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaster, J.H. Gravity in the Brain: How It Might Regulate Skeletal Muscle Metabolism by Balancing Compressive Ischemic Changes in the Weight-Bearing Hypothalamus, While Sometimes Predisposing to Maladaptive Cerebral β-Amyloid Deposition. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2023, 23, 645–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.-C.; Bogale, T.A.; Koistinaho, J.; Pizzi, M.; Rolova, T.; Bellucci, A. The Contribution of β-Amyloid, Tau and α-Synuclein to Blood-Brain Barrier Damage in Neurodegenerative Disorders. Acta Neuropathol. 2024, 147, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoyama, Y.; Yamada, Y.; Kosugi, K.; Yamada, M.; Narita, K.; Nakahara, T.; Fujiwara, H.; Toda, M.; Jinzaki, M. Effect of Gravity on Brain Structure as Indicated on Upright Computed Tomography. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voldsbekk, I.; Groote, I.; Zak, N.; Roelfs, D.; Geier, O.; Due-Tønnessen, P.; Løkken, L.-L.; Strømstad, M.; Blakstvedt, T.Y.; Kuiper, Y.S.; et al. Sleep and Sleep Deprivation Differentially Alter White Matter Microstructure: A Mixed Model Design Utilising Advanced Diffusion Modelling. Neuroimage 2021, 226, 117540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, M.; Molnar, A.; Angeli, O.; Szabo, D.; Bernath, F.; Hajdu, D.; Gombocz, E.; Mate, B.; Jiling, B.; Nagy, B.V.; et al. Prevalence of Cilioretinal Arteries: A Systematic Review and a Prospective Cross-Sectional Observational Study. Acta Ophthalmol. 2021, 99, e310–e318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaster, J.H. Age-Related Arterial Dysfunction in the Brain May Precede Parkinson’s Disease and Other Types of Dementia, Reflecting a Failure to Release Gravitational Ischemia. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2024, 327, H000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shinojima, A.; Kakeya, I.; Tada, S. Association of Space Flight With Problems of the Brain and Eyes. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2018, 136, 1075–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wåhlin, A.; Holmlund, P.; Fellows, A.M.; Malm, J.; Buckey, J.C.; Eklund, A. Optic Nerve Length before and after Spaceflight. Ophthalmology 2021, 128, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starčević, A.; Radojičić, Z.; Djurić Stefanović, A.; Trivić, A.; Milić, I.; Milić, M.; Matić, D.; Andrejic, J.; Djulejic, V.; Djoric, I. Morphometric and Volumetric Analysis of Lacrimal Glands in Patients with Thyroid Eye Disease. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 16345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorber, M.; Vidić, B. Measurements of Lacrimal Glands from Cadavers, with Descriptions of Typical Glands and Three Gross Variants. Orbit 2009, 28, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.-K.; Chen, C.-L. Ischemic Retinopathy from Prolonged Orbital Compression. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 390, e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmlund, P.; Støverud, K.-H.; Wåhlin, A.; Wiklund, U.; Malm, J.; Jóhannesson, G.; Eklund, A. Posture-Dependent Collapse of the Optic Nerve Subarachnoid Space: A Combined MRI and Modeling Study. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2021, 62, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, J.H.; Kang, M.C.; Youn, J.; Park, K.-A.; Han, K.-D.; Jung, J.-H. Nonarteritic Anterior Ischemic Optic Neuropathy and Incidence of Parkinson’s Disease Based on a Nationwide Population Based Study. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 2930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, W.; Pan, Z.; Xie, F. Efficacy and Safety of Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy for Parkinson’s Disease with Cognitive Dysfunction: Protocol for a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMJ Open 2024, 14, e087164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, S.; Liu, W.; Sheng, X.; Jin, L.; Zhao, Q. Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy Improves Motor Symptoms, Sleep, and Cognitive Dysfunctions in Parkinson’s Disease. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2025, 54, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.; Tan, W.; Ran, X.; Yan, M.; Xie, F. Effect of Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy for Non-Motor Symptoms among Patients with Parkinson’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Rehabil. 2025, 39, 281–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaster, J.H.; Ottaviani, G. Gravitational Ischemia in the Brain—May Be Exacerbated by High Altitude and Reduced Partial Pressure of Oxygen, Inducing Lung Changes Mimicking Neurogenic Pulmonary Edema. Int. J. Cardiol. 2021, 343, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, N.; Ji, H.; Guan, Z.; Pan, Y.; Deng, C.; Guo, Y.; Liu, D.; Chen, T.; Wang, S.; Wu, Y.; et al. A Deep Learning System for Detecting Silent Brain Infarction and Predicting Stroke Risk. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2025, 9, 1907–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, M.; Wang, Y.; Xu, S. From Retina to Brain: How Deep Learning Closes the Gap in Silent Stroke Screening. NPJ Digit. Med. 2025, 8, 655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drachmann, J.; Petersen, L.; Jeppesen, S.K.; Bek, T. Systemic Hypoxia Increases Retinal Blood Flow but Reduces the Oxygen Saturation Less in Peripheral Than in Macular Vessels in Normal Persons. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2025, 66, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magonio, F. REM Phase: An Ingenious Mechanism to Enhance Clearance of Metabolic Waste from the Retina. Exp. Eye Res. 2022, 214, 108860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limoli, C.; Khalid, H.; Wagner, S.K.; Huemer, J. Retinal Ischemic Perivascular Lesions (RIPLs) as Potential Biomarkers for Systemic Vascular Diseases: A Narrative Review of the Literature. Ophthalmol. Ther. 2025, 14, 1183–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, X.; Liu, Y.; Xie, M.; Li, C.; Li, X.; Shang, D.; Chen, M.; Chen, H.; Su, W. Parkinson’s Disease with Possible REM Sleep Behavior Disorder Correlated with More Severe Glymphatic System Dysfunction. NPJ Park. Dis. 2025, 11, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, M.; Ferrari, V.; Pierantozzi, M.; Simonetta, C.; Carparelli, F.; D’Angelo, V.; Bagetta, S.; Di Giuliano, F.; Mercuri, N.B.; Schirinzi, T.; et al. Increased Blood-Brain Barrier Permeability Is Associated with Dysfunctional α Band Connectivity in Early-Stage Parkinson’s Disease. J. Neural Transm. 2025; online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDevitt, E.A.; Kim, G.; Turk-Browne, N.B.; Norman, K.A. The Role of Rapid Eye Movement Sleep in Neural Differentiation of Memories in the Hippocampus. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 2025; online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.-T.; Zhang, H.; Su, W.; Liu, W.; Chen, Y.-T.; Ren, H.-Y.; He, M.; Zhang, Y.-X.; Fan, Y.-P.; Liu, W.; et al. Age-(in)Dependent Altered Molecular Mechanisms in Parkinson’s Disease through Extracellular Vesicle Proteome and Lipidome. Cell Rep. Med. 2025, 6, 102432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erhardt, E.B.; Mayer, A.R.; Lin, H.C.; Pirio Richardson, S.E.; Shaff, N.A.; Vakhtin, A.A.; Caprihan, A.; van der Horn, H.J.; Hoffman, N.; Phillips, J.P.; et al. The Influence of Intermittent Hypercapnia on Cerebrospinal Fluid Flow and Clearance in Parkinson’s Disease and Healthy Older Adults. NPJ Park. Dis. 2025, 11, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).