Height, Sex, and Sport as Correlates of Tendon Stiffness in Elite Athletes

Abstract

1. Introduction

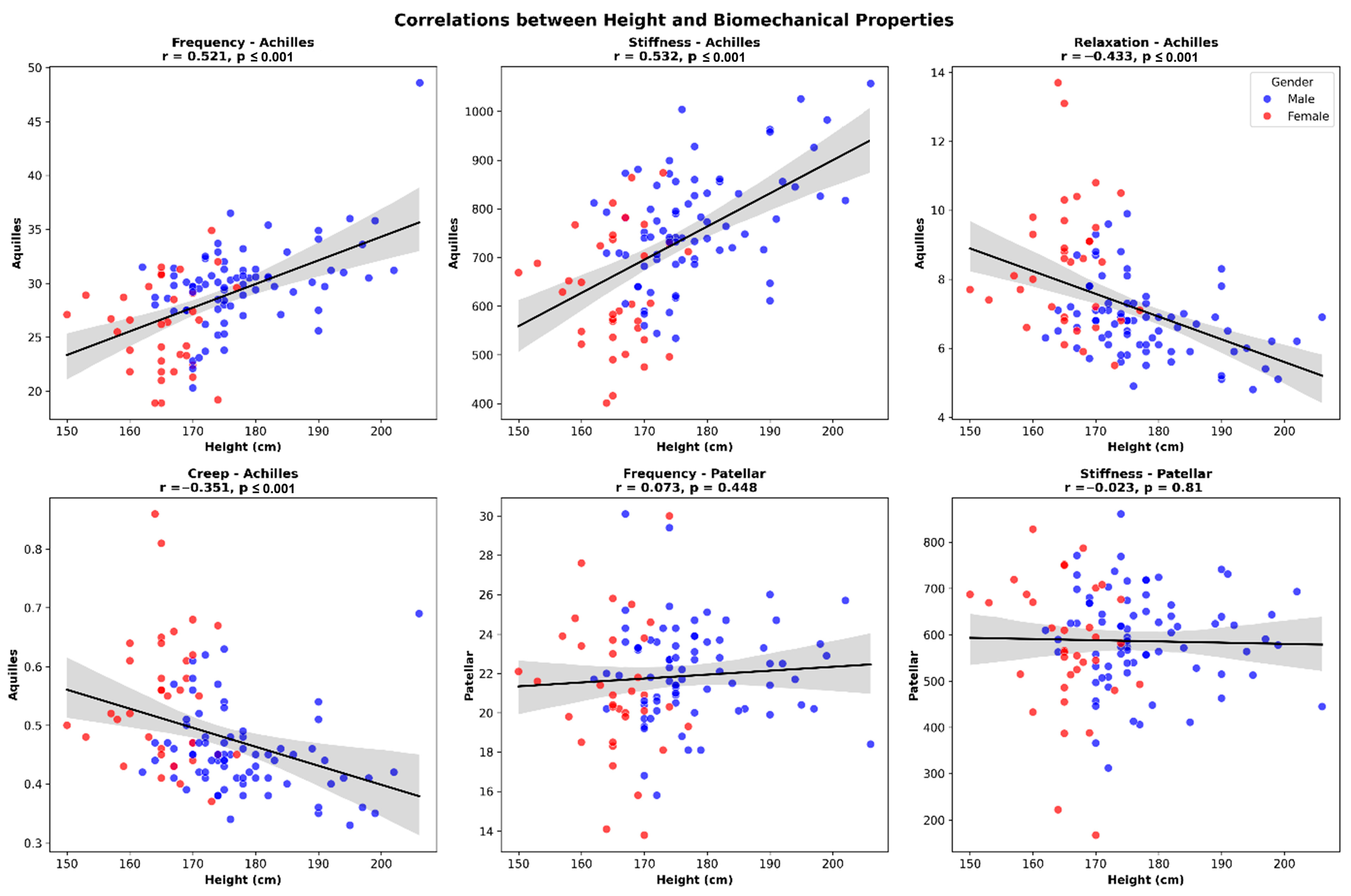

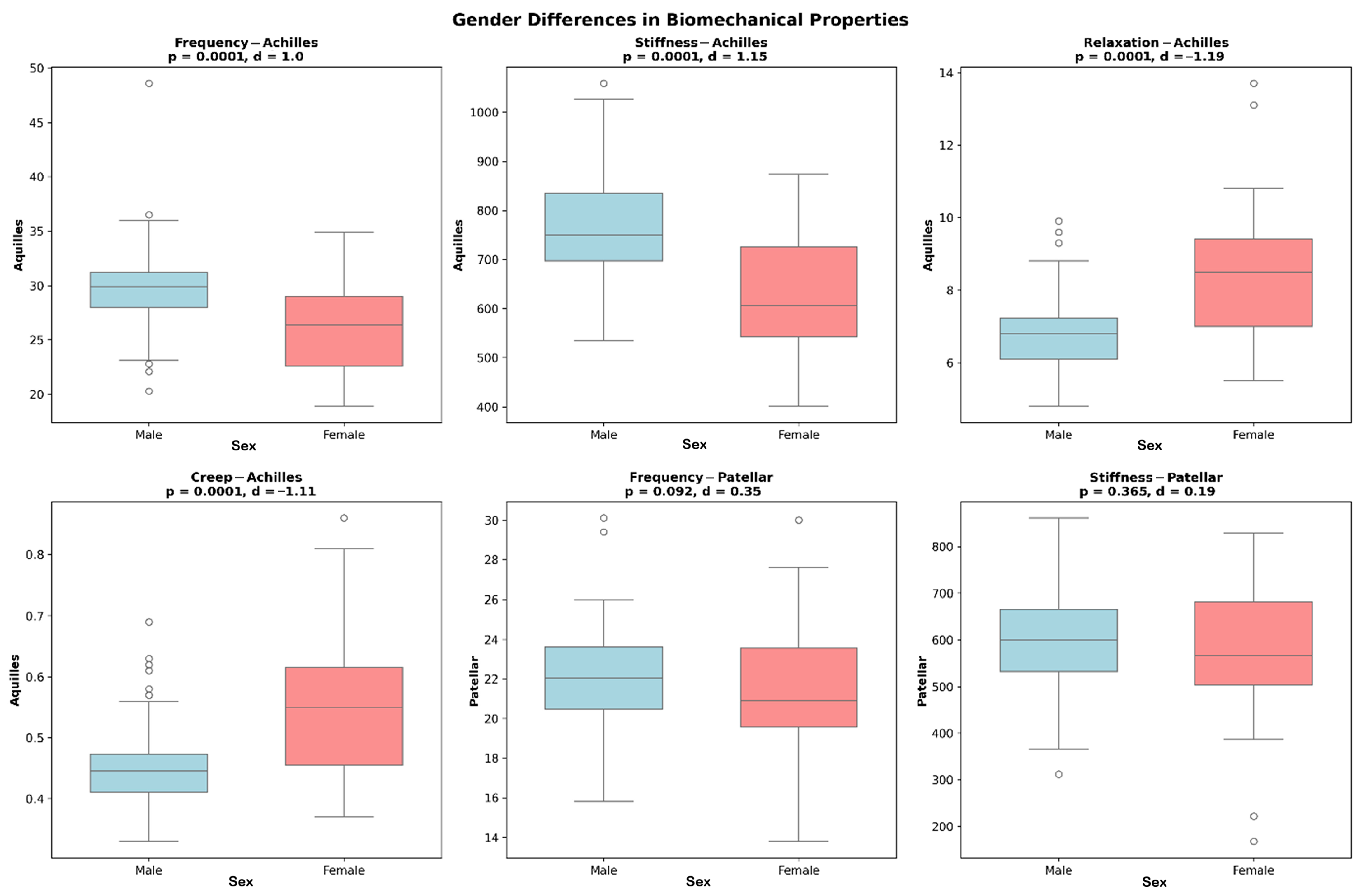

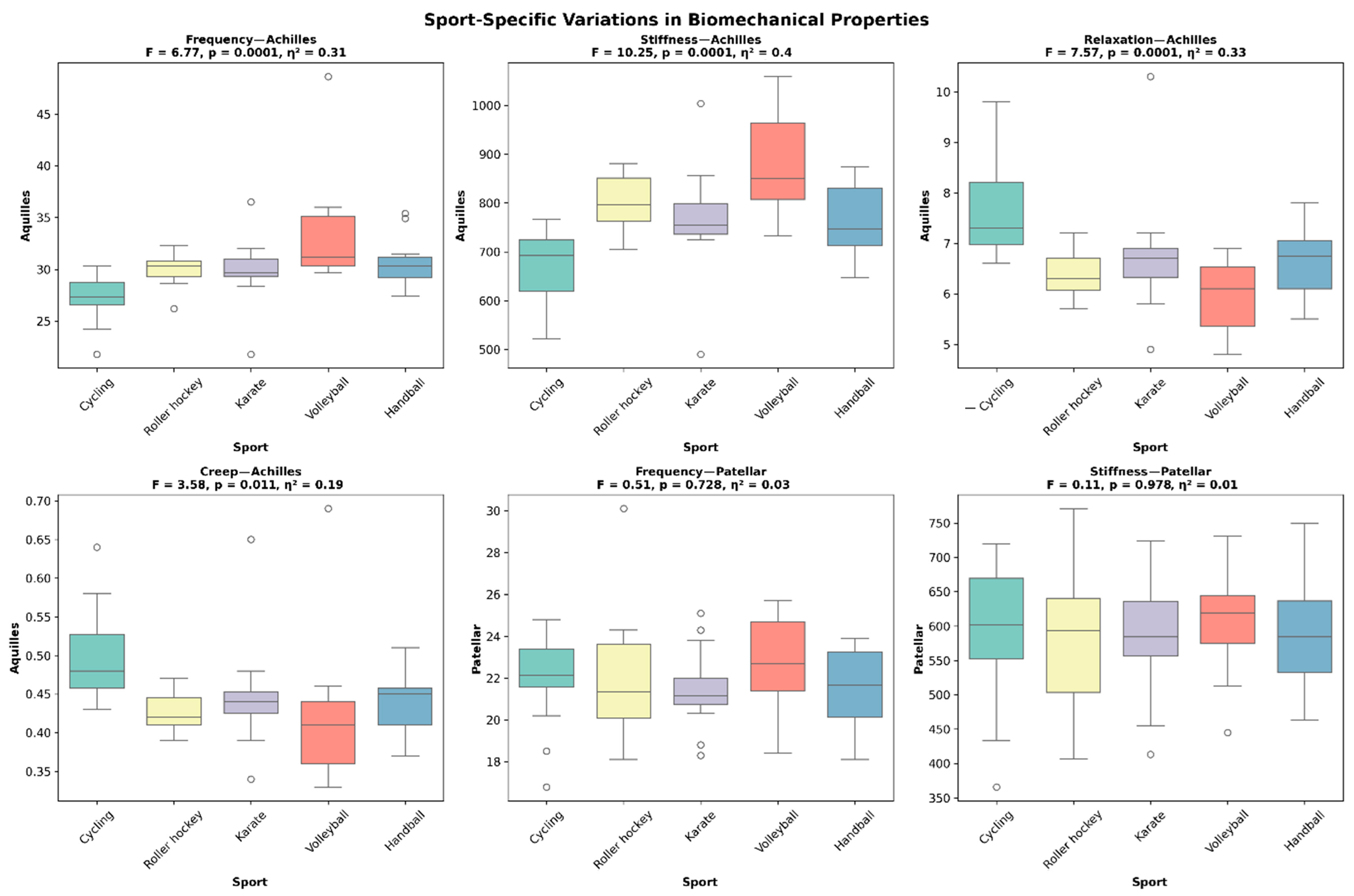

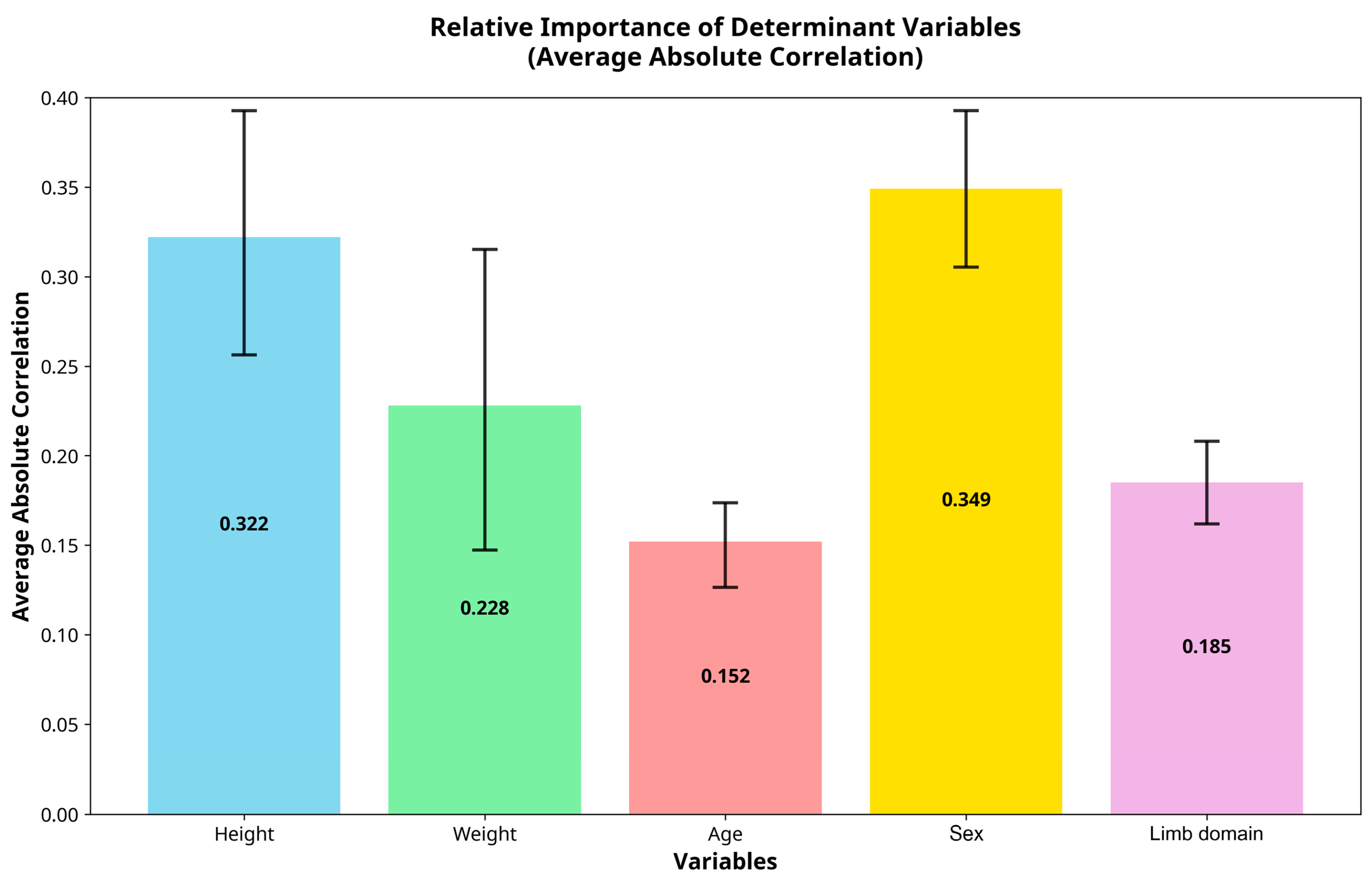

2. Results

3. Discussion

Practical Applications

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Experimental Approach

4.2. Participants

4.3. Anthropometric Measurements

4.4. Limb Dominance Assessment

4.5. Myoton Measurements

- (a)

- Frequency, measured in Hertz (Hz), reflects the natural oscillation frequency of the tissue after a mechanical impulse and is an indicator of dynamic stiffness; it is calculated using the formula *f* = (1/2π) √(*k*/*m*).

- (b)

- Stiffness, expressed in Newtons per meter (N/m), represents the tissue’s resistance to deformation under an external force and is related to structural elasticity, defined by the formula S = F/Δ*x*.

- (c)

- Logarithmic decrement is a dimensionless parameter that describes the reduction rate in the vibration amplitude following perturbation, reflecting viscoelastic damping; it is calculated as D = (A1 − A2)/A1.

- (d)

- Relaxation, measured in milliseconds (ms), is the time required for the tissue to reduce internal stress under constant deformation, indicating viscoelastic relaxation; it is defined by the formula ε(*t*) = ε0 *e*(−λt).

- (e)

- Creep, quantified in millimeters (mm), refers to the progressive increase in deformation under a constant load maintained over time, as expressed by the formula ε(*t*) = ε0 + Δε (1 − *e*(−βt)).

4.6. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| Hz | Hertz |

| ICC | Intraclass Correlation Coefficient |

| ISAK | International Society for the Advancement of Kinanthropometry |

| N/m | Newtons per meter |

| η2 (eta2) | Eta-squared (effect size measure) |

| R2 | Coefficient of Determination |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

References

- McMahon, G.; Cook, J. Female tendons are from venus and male tendons are from mars, but does it matter for tendon health? Sports Med. 2024, 54, 2467–2474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cassel, M.; Intziegianni, K.; Risch, L.; Müller, S.; Engel, T.; Mayer, F. Physiological Tendon Thickness Adaptation in Adolescent Elite Athletes: A Longitudinal Study. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiesinger, H.-P.; Rieder, F.; Kösters, A.; Müller, E.; Seynnes, O. Are Sport-Specific Profiles of Tendon Stiffness and Cross-Sectional Area Determined by Structural or Functional Integrity? PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0158441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cristi-Sánchez, I.; Danes-Daetz, C.; Neira, A.; Ferrada, W.; Yáñez Díaz, R.; Silvestre Aguirre, R. Patellar and Achilles Tendon Stiffness in Elite Soccer Players Assessed Using Myotonometric Measurements. Sports Health 2019, 11, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepley, A.S.; Joseph, M.F.; Daigle, N.R.; Digiacomo, J.E.; Galer, J.; Rock, E.; Rosier, S.B.; Sureja, P.B. Sex Differences in Mechanical Properties of the Achilles Tendon: Longitudinal Response to Repetitive Loading Exercise. J. Strength. Cond. Res. 2018, 32, 3070–3079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Deng, L.; Xiao, S.; Li, L.; Fu, W. Sex Differences in the Morphological and Mechanical Properties of the Achilles Tendon. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGowen, J.M.; Hoppes, C.W.; Forsse, J.S.; Albin, S.R.; Abt, J.; Koppenhaver, S.L. The utility of myotonometry in musculoskeletal rehabilitation and human performance programming. J. Athl. Train. 2023, 58, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koterba, J.; Saulicz, E. Reliability of Measurement of Neck and Back Muscle Mechanical Properties Using MyotonPRO: A Systematic Review. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 2025, 44, 616–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjær, M.; Petersen, J.; Dünweber, M.; Andersen, J.; Engebretsen, L.; Magnusson, S. Dilemma in the Treatment of Sports Injuries in Athletes: Tendon Overuse, Muscle Strain, and Tendon Rupture. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2025, 35, e70026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ra’ad, M.K.; Sukanen, M.; Finni, T. Achilles Tendon stiffness: Influence of measurement methodology. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2024, 50, 1522–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volesky, K.; Novak, J.; Janek, M.; Katolicky, J.; Tufano, J.J.; Steffl, M.; Courel-Ibáñez, J.; Vetrovsky, T. Assessing the Test-Retest Reliability of MyotonPRO for Measuring Achilles Tendon Stiffness. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2025, 10, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Deng, L.; Xiao, S.; Fu, W. Morphological and viscoelastic properties of the Achilles tendon in the forefoot, rearfoot strike runners, and non-runners in vivo. Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 1256908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurashina, W.; Iijima, Y.; Sasanuma, H.; Saito, T.; Takeshita, K. Evaluation of muscle stiffness in adhesive capsulitis with Myoton PRO. JSES Int. 2023, 7, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Römer, C.; Zessin, E.; Czupajllo, J.; Fischer, T.; Wolfarth, B.; Lerchbaumer, M.H. Effect of anthropometric parameters on achilles tendon stiffness of professional athletes measured by shear wave elastography. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 2963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trybulski, R.; Kużdżał, A.; Wilk, M.; Więckowski, J.; Fostiak, K.; Muracki, J. Reliability of MyotonPro in measuring the biomechanical properties of the quadriceps femoris muscle in people with different levels and types of motor preparation. Front. Sports Act. Living 2024, 6, 1453730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaPrade, C.M.; Chona, D.V.; Cinque, M.E.; Freehill, M.T.; McAdams, T.R.; Abrams, G.D.; Sherman, S.L.; Safran, M.R. Return-to-play and performance after operative treatment of Achilles tendon rupture in elite male athletes: A scoping review. Br. J. Sports Med. 2022, 56, 515–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, J.J.; Chen, K.K.; Sarker, S.; Hasija, R.; Huang, H.-H.; Guzman, J.Z.; Vulcano, E. Epidemiology of Achilles tendon injuries in collegiate level athletes in the United States. Int. Orthop. 2020, 44, 585–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brazier, J.; Maloney, S.; Bishop, C.; Read, P.J.; Turner, A.N. Lower extremity stiffness: Considerations for testing, performance enhancement, and injury risk. J. Strength. Cond. Res. 2019, 33, 1156–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.J., IV; Gruber, A.H. Leg stiffness, joint stiffness, and running-related injury: Evidence from a prospective cohort study. Orthop. J. Sports Med. 2021, 9, 23259671211011213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackney, J.; Wilcoxon, S.; Holtmeier, M.; Eaves, H.; Harker, G.; Potthast, A. Low Stiffness Dance Flooring Increases Peak Ankle Plantar Flexor Muscle Activation During a Ballet Jump. J. Danc. Med. Sci. 2023, 27, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneebeli, A.; Falla, D.; Clijsen, R.; Barbero, M. Myotonometry for the evaluation of Achilles tendon mechanical properties: A reliability and construct validity study. BMJ Open Sport. Exerc. Med. 2020, 6, e000726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohm, S.; Mersmann, F.; Arampatzis, A. Human tendon adaptation in response to mechanical loading: A systematic review and meta-analysis of exercise intervention studies on healthy adults. Sports Med. Open 2015, 1, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sukanen, M.; Khair, R.a.M.; Ihalainen, J.K.; Laatikainen-Raussi, I.; Eon, P.; Nordez, A.; Finni, T. Achilles tendon and triceps surae muscle properties in athletes. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2024, 124, 633–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weidlich, K.; Domroes, T.; Bohm, S.; Arampatzis, A.; Mersmann, F. Addressing muscle–tendon imbalances in adult male athletes with personalized exercise prescription based on tendon strain. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2024, 124, 3201–3214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maloof, A.; Hackett, L.; Bilbrough, J.; Hayek, C.; Murrell, G. Evaluating Elastographic Tendon Stiffness as a Predictor of Return to Work and Sports After Primary Rotator Cuff Repair. Orthop. J. Sports Med. 2025, 13, 23259671241306761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, M. Female hormones: Do they influence muscle and tendon protein metabolism? Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2018, 77, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taş, S.; Yılmaz, S.; Onur, M.R.; Soylu, A.R.; Altuntaş, O.; Korkusuz, F. Patellar tendon mechanical properties change with gender, body mass index and quadriceps femoris muscle strength. Acta Orthop. Traumatol. Turc. 2017, 51, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, D.; Verderber, L.; Germano, A.M.; Nitzsche, N. Correlations Between Achilles Tendon Stiffness and Jumping Performance: A Comparative Study of Soccer and Basketball Athletes. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2025, 10, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seymore, K.D.; Hanlon, S.L.; Pohlig, R.T.; Elliott, D.M.; Silbernagel, K.G. Relationship Between Structure and Age in Healthy Achilles Tendons. J. Orthop. Res. 2025, 43, 1250–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo-Sánchez, A.; Abián, P.; Jiménez, F.; Abián-Vicén, J. Myotendinous asymmetries derived from the prolonged practice of badminton in professional players. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0222190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pissarra, Â.; Ribeiro, L.; Rodrigues, S. Ultrasonographic Evaluation of the Patellar Tendon in Cyclists, Volleyball Players, and Non-Practitioners of Sports—The Influence of Gender, Age, Height, Dominant Limb, and Level of Physical Activity. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2024, 9, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobs, M.W.; Feuerbacher, J.F.; Mersmann, F.; Bloch, W.; Arampatzis, A.; Schumann, M. Maximal strength training improves muscle-tendon properties and increases tendon matrix remodulation in well-trained triathletes. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 27333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorimer, A.V.; Hume, P.A. Stiffness as a Risk Factor for Achilles Tendon Injury in Running Athletes. Sports Med. 2016, 46, 1921–1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szajkowski, S.; Pasek, J.; Dwornik, M.; Cieślar, G. Mechanical properties of the patellar tendon in weightlifting athletes—The utility of myotonometry. Adaptations of patellar tendon to mechanical loading. Acta Bioeng. Biomech. 2024, 26, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Römer, C.; Czupajllo, J.; Wolfarth, B.; Sichting, F.; Legerlotz, K. The Myometric Assessment of Achilles Tendon and Soleus Muscle Stiffness before and after a Standardized Exercise Test in Elite Female Volleyball and Handball Athletes—A Quasi-Experimental Study. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 3243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malliaras, P.; Barton, C.J.; Reeves, N.D.; Langberg, H. Achilles and patellar tendinopathy loading programmes: A systematic review comparing clinical outcomes and identifying potential mechanisms for effectiveness. Sports Med. 2013, 43, 267–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksen, C.S.; Svensson, R.B.; Gylling, A.T.; Couppé, C.; Magnusson, S.P.; Kjaer, M. Load magnitude affects patellar tendon mechanical properties but not collagen or collagen cross-linking after long-term strength training in older adults. BMC Geriatr. 2019, 19, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohlgemuth, R.P.; Brashear, S.E.; Smith, L.R. Alignment, cross linking, and beyond: A collagen architect’s guide to the skeletal muscle extracellular matrix. Am. J. Physiol.-Cell Physiol. 2023, 325, C1017–C1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breine, B.; Malcolm, P.; Galle, S.; Fiers, P.; Frederick, E.C.; Clercq, D.D. Running Speed-induced Changes in Foot Contact Pattern Influence Impact Loading Rate. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2018, 19, 774–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiesinger, H.-P.; Rieder, F.; Kösters, A.; Müller, E.; Seynnes, O.R. Sport-specific capacity to use elastic energy in the patellar and Achilles tendons of elite athletes. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blazevich, A.; Fletcher, J. More than energy cost: Multiple benefits of the long Achilles tendon in human walking and running. Biol. Rev. 2022, 98, 2210–2225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, C.; Deng, L.; Li, L.; Zhang, X.; Fu, W. Exercise Effects on the Biomechanical Properties of the Achilles Tendon—A Narrative Review. Biology 2022, 11, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taş, S.; Yüzbaşıoğlu, Ü.; Ekici, E.; Katmerlikaya, A. Sex-related differences in human tendon stiffness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Indian J. Orthop. 2025, 59, 876–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gianakos, A.L.; Hartman, H.; Kerkhoffs, G.M.; Calder, J.; Kennedy, J.G. Sex differences in biomechanical properties of the Achilles tendon may predispose men to higher risk of injury: A systematic review. J. ISAKOS 2024, 9, 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mersmann, F.; Domroes, T.; Tsai, M.S.; Pentidis, N.; Schroll, A.; Bohm, S.; Arampatzis, A. Longitudinal Evidence for High-Level Patellar Tendon Strain as a Risk Factor for Tendinopathy in Adolescent Athletes. Sports Med. Open 2023, 9, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, X.; Lu, B.; Sun, X.; Cui, J.; Tian, G.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Y.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, G.; et al. Biomechanical and neuromuscular adaptations in joint contributions during loaded countermovement jumps. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 19167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malliaras, P.; Cook, J.; Purdam, C.; Rio, E. Patellar Tendinopathy: Clinical Diagnosis, Load Management, and Advice for Challenging Case Presentations. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2015, 45, 887–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassel, M.; Carlsohn, A.; Fröhlich, K.; John, M.; Riegels, N.; Mayer, F. Tendon adaptation to sport-specific loading in adolescent athletes. Int. J. Sports Med. 2016, 37, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwamoto, N.; Arita, Y.; Takahashi, H. Bilateral Characteristics of the Achilles Tendon and Their Relationship with Jump Performance in University Kendo Athletes. J. Musculoskelet. Neuronal Interact. 2025, 25, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couppé, C.; Svensson, R.; Skovlund, S.; Jensen, J.; Eriksen, C.; Malmgaard-Clausen, N.; Nybing, J.; Kjaer, M.; Magnusson, S. Habitual side-specific loading leads to structural, mechanical and compositional changes in the patellar tendon of young and senior life-long male athletes. J. Appl. Physiol. 2021, 131, 1187–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarczuk, S.; Maniar, N.; Opar, D.; Duhig, S.; Shield, A.; Barrett, R.; Bourne, M. Mechanical, Material and Morphological Adaptations of Healthy Lower Limb Tendons to Mechanical Loading: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2022, 52, 2405–2429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silbernagel, K.; Hanlon, S.; Sprague, A. Current Clinical Concepts: Conservative Management of Achilles Tendinopathy. J. Athl. Train. 2020, 55, 438–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Hondt, L.; Groote, F.D.; Afschrift, M. A Dynamic Foot Model for Predictive Simulations of Gait Reveals Causal Relations Between Foot Structure and Whole Body Mechanics. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2023, 20, e1012219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delabastita, T.; Hollville, E.; Catteau, A.; Cortvriendt, P.; Groote, F.D.; Vanwanseele, B. Distal-to-proximal Joint Mechanics Redistribution Is a Main Contributor to Reduced Walking Economy in Older Adults. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2021, 31, 1036–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacques, T.; Bini, R.; Arndt, A. Bilateral in vivo neuromechanical properties of the triceps surae and Achilles tendon in runners and triathletes. J. Biomech. 2021, 123, 110493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luis, I.; Afschrift, M.; Groote, F.D.; Gutierrez-Farewik, E.M. Insights Into Muscle Metabolic Energetics: Modelling Muscle-Tendon Mechanics and Metabolic Rates During Walking Across Speeds. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2024, 20, e1012411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubo, K.; Teshima, T.; Hirose, N.; Tsunoda, N. A Longitudinal Study of the Physical Characteristics, Muscle-Tendon Structure Properties, and Skeletal Age in Preadolescent Boys. J. Musculoskelet. Neuronal Interact. 2023, 23, 407–416. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, M.M.; Hannafin, J.A. The Mature Athlete: Aging Tendon and Ligament. Sports Health 2013, 6, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenroth, L.; Cronin, N.J.; Peltonen, J.; Korhonen, M.T.; Sipilä, S.; Finni, T. Triceps surae muscle-tendon properties in older endurance- and sprint-trained athletes. J. Appl. Physiol. 2015, 120, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensson, R.B.; Heinemeier, K.M.; Couppé, C.; Kjaer, M.; Magnusson, S.P. Effect of aging and exercise on the tendon. J. Appl. Physiol. 2016, 121, 1353–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rettig, A.C.; Liotta, F.J.; Klootwyk, T.E.; Porter, D.A.; Mieling, P. Potential Risk of Rerupture in Primary Achilles Tendon Repair in Athletes Younger than 30 Years of Age. Am. J. Sports Med. 2005, 33, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Docking, S.I.; Cook, J. How do tendons adapt? Going beyond tissue responses to understand positive adaptation and pathology development: A narrative review. J. Musculoskelet. Neuronal Interact. 2019, 19, 300. [Google Scholar]

- Karamanidis, K.; Epro, G. Monitoring Muscle-Tendon Adaptation Over Several Years of Athletic Training and Competition in Elite Track and Field Jumpers. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 607544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mencel, J.; Marusiak, J.; Jaskólska, A.; Jaskólski, A.; Kisiel-Sajewicz, K. Impact of the Location of Myometric Measurement Points on Skeletal Muscle Mechanical Properties Outcomes. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2021, 11, 525–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciejewska-Skrendo, A.; Leźnicka, K.; Leońska-Duniec, A.; Wilk, M.; Filip, A.; Cięszczyk, P.; Sawczuk, M. Genetics of Muscle Stiffness, Muscle Elasticity and Explosive Strength. J. Hum. Kinet. 2020, 74, 143–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombes, B.; Tucker, K.; Vicenzino, B.; Vuvan, V.; Mellor, R.; Heales, L.; Nordez, A.; Hug, F.; Hug, F.; Hug, F. Achilles and patellar tendinopathy display opposite changes in elastic properties: A shear wave elastography study. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2018, 28, 1201–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, G.E.; Martin, R.; Williams, L.; Pearce, O.; Morris, K. Objective assessment of stiffness in Achilles tendinopathy: A novel approach using the MyotonPRO. BMJ Open Sport. Exerc. Med. 2018, 4, e000446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, A.; Detrembleur, C.; Fisette, P.; Selves, C.; Mahaudens, P. MyotonPro Is a Valid Device for Assessing Wrist Biomechanical Stiffness in Healthy Young Adults. Front. Sports Act. Living 2022, 4, 797975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sport | n | Height (m) [95%CI] | BMI (kg/m2) [95%CI] | Weight (kg) [95%CI] | Age (Years) [95%CI] | TL (h/wk) | % Right |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Athletics * | 7 | 1.76 ± 0.08 [1.70, 1.82] ab | 24.2 ± 1.6 [22.9, 25.5] ab | 74.1 ± 11.2 [64.8, 83.4] ab | 25.1 ± 4.2 [21.6, 28.6] | 16 ± 2.5 | 85.7 |

| Archery * | 8 | 1.69 ± 0.09 [1.62, 1.76] a | 24.8 ± 2.7 [22.7, 26.9] ab | 70.6 ± 10.2 [62.5, 78.7] a | 27.6 ± 6.3 [22.6, 32.6] | 14 ± 3.0 | 100 |

| Boxing * | 7 | 1.69 ± 0.11 [1.60, 1.78] a | 22.9 ± 1.9 [21.3, 24.5] a | 65.3 ± 11.6 [55.0, 75.6] a | 23.7 ± 3.2 [21.0, 26.4] | 15 ± 2.0 | 100 |

| Cycling | 15 | 1.68 ± 0.08 [1.64, 1.72] a | 23.4 ± 1.8 [22.4, 24.4] a | 66.1 ± 9.2 [61.1, 71.1] a | 22.5 ± 5.1 [19.8, 25.2] | 18 ± 4.0 | 93.3 |

| Handball | 15 | 1.77 ± 0.07 [1.73, 1.81] b | 25.6 ± 3.3 [23.8, 27.4] b | 80.5 ± 11.8 [74.1, 86.9] b | 25.9 ± 4.7 [23.3, 28.5] | 16 ± 3.0 | 86.7 |

| Judo | 10 | 1.72 ± 0.08 [1.67, 1.77] ab | 29.4 ± 5.0 [25.9, 32.9] c | 83.0 ± 20.4 [68.9, 97.1] b | 25.7 ± 4.3 [22.7, 28.7] | 15 ± 2.5 | 100 |

| Karate | 13 | 1.72 ± 0.06 [1.69, 1.75] ab | 24.1 ± 2.6 [22.6, 25.6] ab | 71.5 ± 9.4 [66.0, 77.0] ab | 25.5 ± 5.0 [22.5, 28.5] | 14 ± 2.0 | 92.3 |

| Volleyball | 14 | 1.90 ± 0.09 [1.85, 1.95] c | 24.7 ± 1.8 [23.7, 25.7] ab | 89.6 ± 11.6 [83.0, 96.2] c | 25.6 ± 3.3 [23.8, 27.4] | 17 ± 3.5 | 92.9 |

| Statistics | <0.001 | 0.002 | <0.001 | 0.381 | 0.381 | 0.682 |

| Variable | Group | Mean ± SD [95% CI] | p-Value (Effect Size) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Achilles tendon | |||

| Frequency (Hz) | Left | 28.5 ± 3.2 a [27.9–29.1] | 0.012 (d = 0.18) |

| Right | 29.1 ± 3.5 [28.4–29.8] | ||

| Male | 29.8 ± 3.4 a [29.1–30.5] | ≤0.001 (d = 0.83) | |

| Female | 27.2 ± 2.8 [26.5–27.9] | ||

| Stiffness (N/m) | Left | 720 ± 120 a [695–745] | 0.021 (d = 0.16) |

| Right | 740 ± 130 [715–765] | ||

| Male | 780 ± 135 a [752–808] | ≤0.001 (d = 1.04) | |

| Female | 650 ± 110 [625–675] | ||

| Logarithmic decrement | Left | 0.98 ± 0.25 [0.93–1.03] | 0.154 |

| Right | 0.95 ± 0.28 [0.89–1.01] | ||

| Male | 0.89 ± 0.22 a [0.85–0.93] | 0.008 (d = 0.60) | |

| Female | 1.05 ± 0.3 [0.98–1.12] | ||

| Relaxation (ms) | Left | 7.2 ± 1.5 [6.9–7.5] | 0.089 |

| Right | 7.0 ± 1.6 [6.7–7.3] | ||

| Male | 6.5 ± 1.4 a [6.2–6.8] | ≤0.001 (d = 0.92) | |

| Female | 8.2 ± 1.5 [7.8–8.6] | ||

| Creep (mm) | Left | 0.48 ± 0.1 [0.46–0.50] | 0.102 |

| Right | 0.46 ± 0.11 [0.44–0.48] | ||

| Male | 0.43 ± 0.09 a [0.41–0.45] | ≤0.001 (d = 1.03) | |

| Female | 0.55 ± 0.12 [0.52–0.58] | ||

| Patellar tendon | |||

| Frequency (Hz) | Left | 21.8 ± 3.1 [21.1–22.5] | 0.243 |

| Right | 21.5 ± 3.4 [20.8–22.2] | ||

| Male | 21.2 ± 3.5 a [20.5–21.9] | 0.035 (d = 0.34) | |

| Female | 22.3 ± 2.8 [21.6–23.0] | ||

| Stiffness (N/m) | Left | 580 ± 135 [552–608] | 0.187 |

| Right | 590 ± 140 [561–619] | ||

| Male | 610 ± 145 a [580–640] | 0.009 (d = 0.53) | |

| Female | 540 ± 120 [515–565] | ||

| Logarithmic decrement (dimensionless) | Left | 0.96 ± 0.11 [0.94–0.98] | 0.421 |

| Right | 0.95 ± 0.12 [0.93–0.97] | ||

| Male | 0.94 ± 0.1 [0.92–0.96] | 0.112 | |

| Female | 0.98 ± 0.13 [0.95–1.01] | ||

| Relaxation (ms) | Left | 9.3 ± 2.1 [8.9–9.7] | 0.305 |

| Right | 9.1 ± 2.3 [8.7–9.5] | ||

| Male | 8.7 ± 2.0 a [8.3–9.1] | ≤0.001 (d = 0.81) | |

| Female | 10.1 ± 2.2 [9.6–10.6] | ||

| Creep (mm) | Left | 0.59 ± 0.14 [0.56–0.62] | 0.188 |

| Right | 0.57 ± 0.15 [0.54–0.60] | ||

| Male | 0.55 ± 0.13 a [0.52–0.58] | 0.002 (d = 0.65) | |

| Female | 0.65 ± 0.15 [0.61–0.69] |

| Sport | n | Frequency (Hz) | Stiffness (N/m) | Logarithmic Decrement | Relaxation (ms) | Creep (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Achilles | ||||||

| Cycling | 15 | 27.8 ± 2.9 a | 675 ± 85 a,b | 1.02 ± 0.18 a | 7.8 ± 1.1 a | 0.51 ± 0.08 a |

| Roller Hockey | 12 | 30.2 ± 1.8 b,c | 805 ± 75 c | 0.89 ± 0.2 b,c | 6.5 ± 0.8 b,c | 0.43 ± 0.07 b,c |

| Karate | 14 | 30.5 ± 3.2 b,c | 785 ± 95 c | 0.82 ± 0.15 c | 6.7 ± 1.0 b | 0.44 ± 0.08 b,c |

| Athletics | 8 | 31.2 ± 2.5 c | 820 ± 110 c | 0.79 ± 0.22 c | 6.3 ± 1.2 c | 0.41 ± 0.09 c |

| Volleyball | 13 | 32.1 ± 3.8 c | 865 ± 130 d | 0.75 ± 0.19 c | 5.9 ± 1.3 c | 0.39 ± 0.1 c |

| Taekwondo | 8 | 26.8 ± 3.5 a | 645 ± 120 a | 0.98 ± 0.25 a,b | 8.2 ± 1.5 a | 0.53 ± 0.11 a |

| Judo | 10 | 27.2 ± 3.8 a | 665 ± 140 a | 1.12 ± 0.3 a | 7.9 ± 1.4 a | 0.52 ± 0.12 a |

| p-value (η2) | <0.001 (0.24) | <0.001 (0.29) | <0.001 (0.22) | <0.001 (0.27) | <0.001 (0.25) | |

| Patellar | ||||||

| Cycling | 15 | 21.2 ± 2.5 | 565 ± 90 | 0.97 ± 0.1 | 9.4 ± 1.2 a | 0.6 ± 0.09 a |

| Roller Hockey | 12 | 21.5 ± 2.8 | 590 ± 110 | 0.94 ± 0.11 | 9.1 ± 1.5 a | 0.58 ± 0.1 a,b |

| Karate | 14 | 21.8 ± 3.5 | 610 ± 125 | 0.93 ± 0.12 | 8.8 ± 1.8 a,b | 0.56 ± 0.11 a,b |

| Athletics | 8 | 22.1 ± 3.1 | 625 ± 135 | 0.91 ± 0.13 | 8.5 ± 1.6 b,c | 0.54 ± 0.1 b,c |

| Volleyball | 13 | 22.5 ± 2.9 | 595 ± 115 | 0.89 ± 0.14 | 8.2 ± 1.4 c | 0.52 ± 0.09 c |

| Taekwondo | 8 | 21.3 ± 4.2 | 610 ± 145 | 0.95 ± 0.15 | 9.1 ± 1.7 a | 0.59 ± 0.12 a |

| Judo | 10 | 22.8 ± 3.7 | 630 ± 135 | 0.99 ± 0.16 | 9.8 ± 1.9 a | 0.63 ± 0.13 a |

| p-value (η2) | 0.325 (0.09) | 0.215 (0.11) | 0.418 (0.07) | 0.012 (0.18) | 0.008 (0.2) |

| Parameter | Cross-Validated R2 | RMSE | MAE | Top 3 Predictors (Importance ± 95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Achilles Stiffness | 0.87 ± 0.04 | 47.2 | 36.8 | Height (0.42 ± 0.08), Weight (0.28 ± 0.05), Sex (0.18 ± 0.04) |

| Achilles Frequency | 0.85 ± 0.05 | 1.31 | 1.02 | Height (0.39 ± 0.09), Sex (0.24 ± 0.06), Weight (0.21 ± 0.04) |

| Patellar Stiffness | 0.74 ± 0.08 | 67.3 | 52.1 | Weight (0.31 ± 0.12), Height (0.29 ± 0.15), Age (0.22 ± 0.08) |

| Patellar Frequency | 0.72 ± 0.09 | 1.58 | 1.24 | Age (0.35 ± 0.11), Sex (0.28 ± 0.13), Height (0.19 ± 0.09) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bustamante-Garrido, A.; Sepúlveda González, S.; Inostroza-Ríos, F.; de Toledo Nóbrega, O.; Miarka, B.; Araya-Ibacache, M.; Aidar, F.J.; Aedo-Muñoz, E.; Brito, C.J. Height, Sex, and Sport as Correlates of Tendon Stiffness in Elite Athletes. Physiologia 2025, 5, 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/physiologia5040056

Bustamante-Garrido A, Sepúlveda González S, Inostroza-Ríos F, de Toledo Nóbrega O, Miarka B, Araya-Ibacache M, Aidar FJ, Aedo-Muñoz E, Brito CJ. Height, Sex, and Sport as Correlates of Tendon Stiffness in Elite Athletes. Physiologia. 2025; 5(4):56. https://doi.org/10.3390/physiologia5040056

Chicago/Turabian StyleBustamante-Garrido, Alejandro, Sebastián Sepúlveda González, Felipe Inostroza-Ríos, Otávio de Toledo Nóbrega, Bianca Miarka, Mauricio Araya-Ibacache, Felipe J. Aidar, Esteban Aedo-Muñoz, and Ciro José Brito. 2025. "Height, Sex, and Sport as Correlates of Tendon Stiffness in Elite Athletes" Physiologia 5, no. 4: 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/physiologia5040056

APA StyleBustamante-Garrido, A., Sepúlveda González, S., Inostroza-Ríos, F., de Toledo Nóbrega, O., Miarka, B., Araya-Ibacache, M., Aidar, F. J., Aedo-Muñoz, E., & Brito, C. J. (2025). Height, Sex, and Sport as Correlates of Tendon Stiffness in Elite Athletes. Physiologia, 5(4), 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/physiologia5040056