One Week of a Betalain-Rich Beetroot Concentrate Does Not Improve 4 km Time-Trial Performance but Impairs Repeated Sprint Cycling Performance in Trained Cyclists

Abstract

1. Introduction

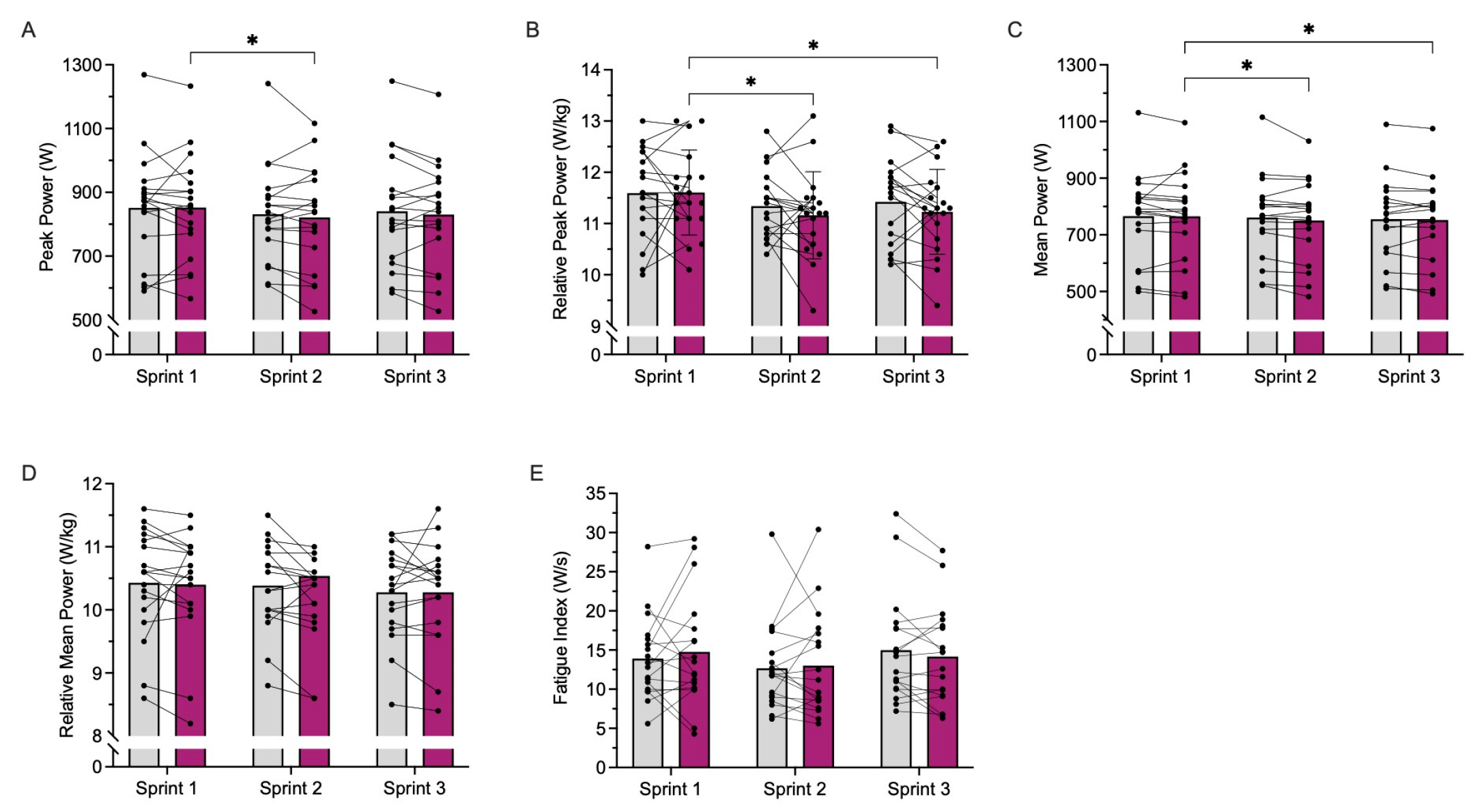

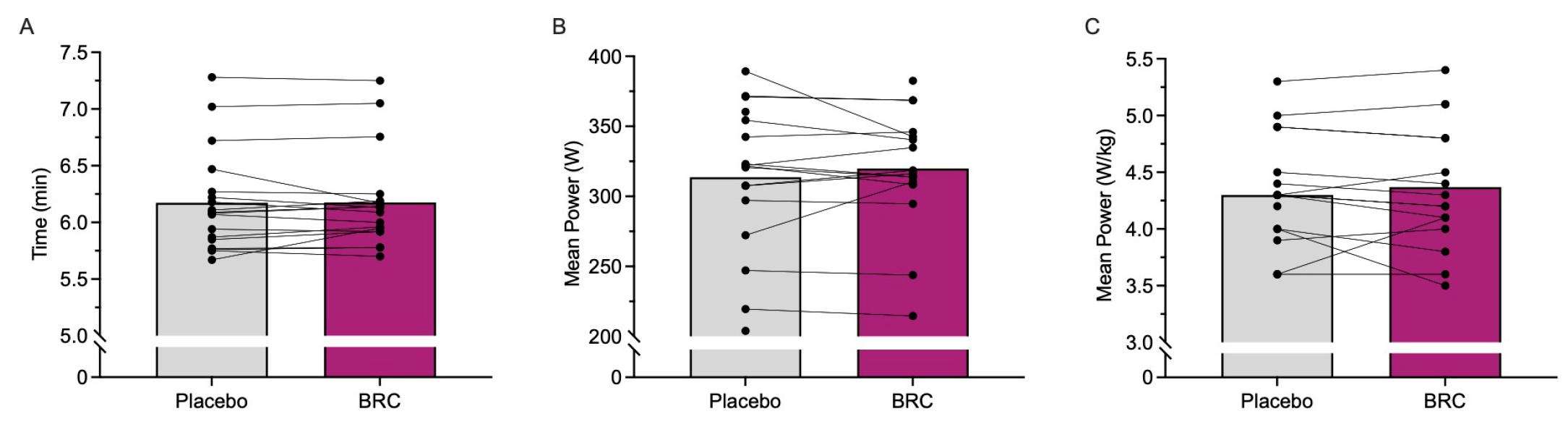

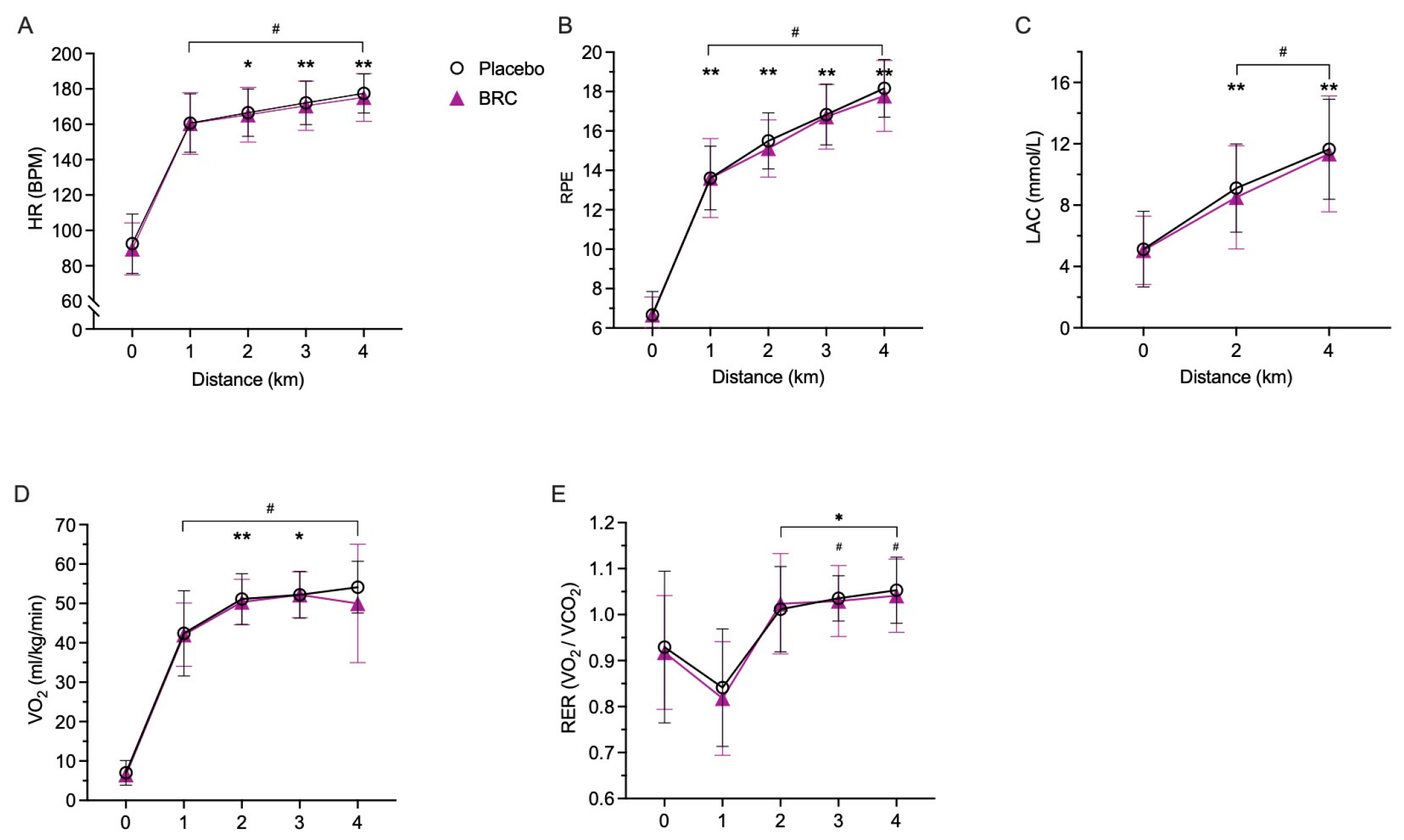

2. Results

3. Discussion

3.1. Repeated-Sprint Performance

3.2. 4 km TT Performance

3.3. Experimental Considerations

3.4. Limitations

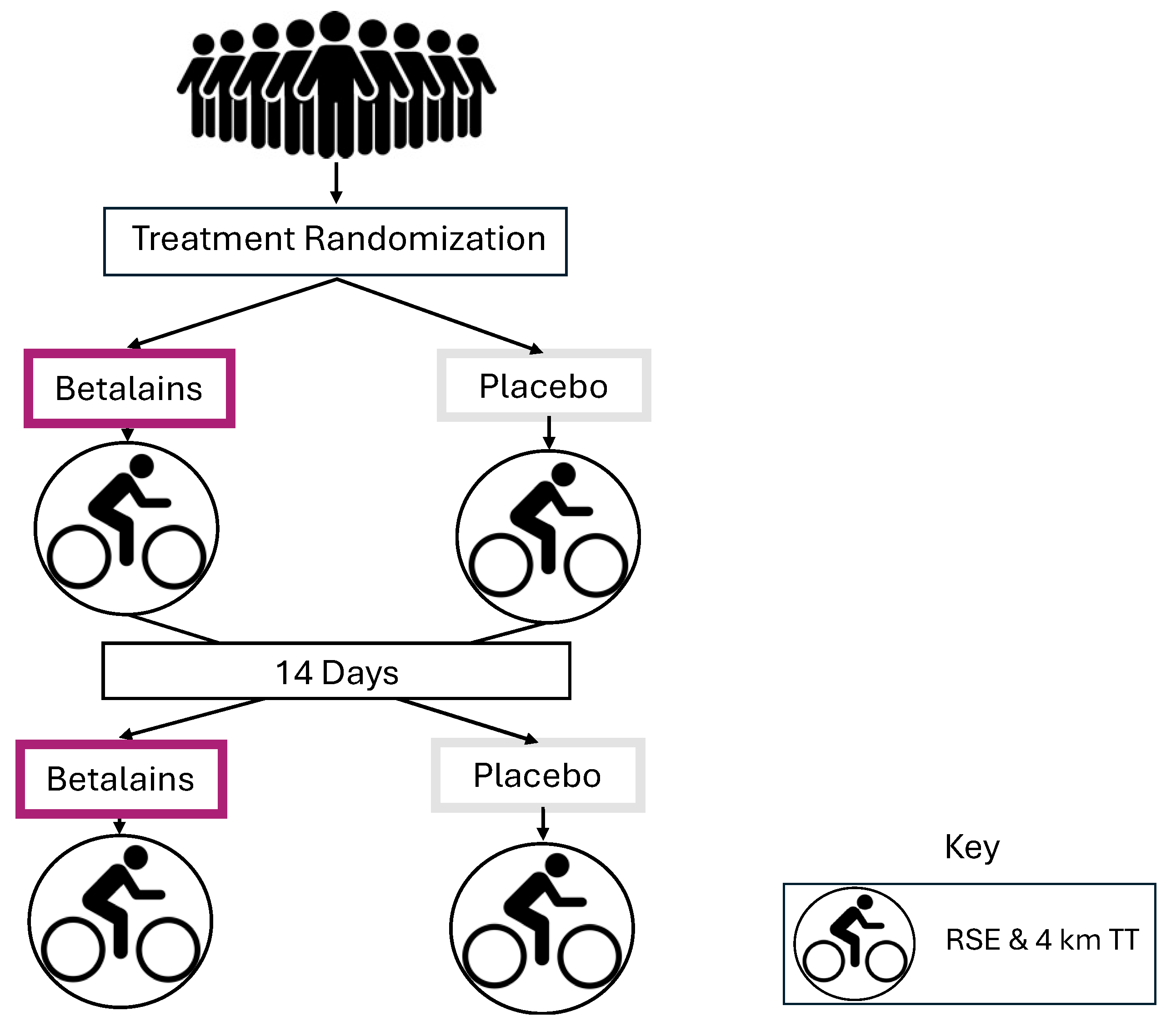

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Participants

4.2. Experimental Procedures

4.3. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BRC | Betalain-rich concentrate |

| HR | Heart rate |

| LAC | Lactate |

| NO | Nitric oxide |

| PCr | Phosphocreatine |

| PLA | Placebo |

| RBJ | Red Beetroot |

| RER | Respiratory exchange ratio |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| RPE | Rating of perceived exertion |

| RSE | Repeated sprint exercise |

| TT | Time trial |

| VO2 | Oxygen consumption |

References

- Jeukendrup, A.E.; Craig, N.P.; Hawley, J.A. The Bioenergetics of World Class Cycling. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2000, 3, 414–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorenza, M.; Hostrup, M.; Gunnarsson, T.P.; Shirai, Y.; Schena, F.; Iaia, F.M.; Bangsbo, J. Neuromuscular Fatigue and Metabolism during High-Intensity Intermittent Exercise. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2019, 51, 1642–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weavil, J.C.; Amann, M. Neuromuscular Fatigue during Whole Body Exercise. Curr. Opin. Physiol. 2019, 10, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfieri, A.; D’Angelo, S.; Mazzeo, F. Role of Nutritional Supplements in Sport, Exercise and Health. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeling, P.; Binnie, M.J.; Goods, P.S.R.; Sim, M.; Burke, L.M. Evidence-Based Supplements for the Enhancement of Athletic Performance. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2018, 28, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, T.H.; Sim, A.; Burns, S.F. The Effects of Nitrate Ingestion on High-Intensity Endurance Time-Trial Performance: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Exerc. Sci. Fit. 2022, 20, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, R.; Cass, J.K.; Lincoln, I.G.; Wideen, L.E.; Nicholl, M.J.; Molnar, T.J.; Gough, L.A.; Bailey, S.J.; Pennell, A. Effects of Dietary Nitrate Supplementation on High-Intensity Cycling Sprint Performance in Recreationally Active Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clifford, T.; Howatson, G.; West, D.; Stevenson, E. The Potential Benefits of Red Beetroot Supplementation in Health and Disease. Nutrients 2015, 7, 2801–2822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albano, C.; Negro, C.; Tommasi, N.; Gerardi, C.; Mita, G.; Miceli, A.; De Bellis, L.; Blando, F. Betalains, Phenols and Antioxidant Capacity in Cactus Pear (Opuntia ficus-indica (L.) Mill.) Fruits from Apulia (South Italy) Genotypes. Antioxidants 2015, 4, 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrzkowski, Z.; Nemzer, B.; Spórna, A.; Stalica, P.; Tresher, W.; Keller, R.; Jimenez, R.; Michałowski, T.; Wybraniec, S. Influence of Betalain-Rich Extract on Reduction of Discomfort Associated with Osteoarthritis. New Med. 2010, 1, 12–17. [Google Scholar]

- Nemzer, B.V.; Pietrzkowski, Z.; Hunter, J.M.; Robinson, J.L.; Fink, B. A Betalain-Rich Dietary Supplement, but Not PETN, Increases Vasodilation and Nitric Oxide: A Comparative, Single-Dose, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Blinded, Crossover Pilot Study. J. Food Res. 2020, 10, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hoorebeke, J.; Trias, C.; Davis, B.; Lozada, C.; Casazza, G. Betalain-Rich Concentrate Supplementation Improves Exercise Performance in Competitive Runners. Sports 2016, 4, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montenegro, C.F.; Kwong, D.A.; Minow, Z.A.; Davis, B.A.; Lozada, C.F.; Casazza, G.A. Betalain-Rich Concentrate Supplementation Improves Exercise Performance and Recovery in Competitive Triathletes. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2017, 42, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumford, P.W.; Kephart, W.C.; Romero, M.A.; Haun, C.T.; Mobley, C.B.; Osburn, S.C.; Healy, J.C.; Moore, A.N.; Pascoe, D.D.; Ruffin, W.C.; et al. Effect of 1-Week Betalain-Rich Beetroot Concentrate Supplementation on Cycling Performance and Select Physiological Parameters. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2018, 118, 2465–2476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendez-Villanueva, A.; Edge, J.; Suriano, R.; Hamer, P.; Bishop, D. The Recovery of Repeated-Sprint Exercise Is Associated with PCr Resynthesis, While Muscle pH and EMG Amplitude Remain Depressed. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e51977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przyborowski, K.; Proniewski, B.; Czarny, J.; Smeda, M.; Sitek, B.; Zakrzewska, A.; Zoladz, J.A.; Chlopicki, S. Vascular Nitric Oxide–Superoxide Balance and Thrombus Formation after Acute Exercise. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2018, 50, 1405–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leite, C.D.F.C.; Zovico, P.V.C.; Rica, R.L.; Barros, B.M.; Machado, A.F.; Evangelista, A.L.; Leite, R.D.; Barauna, V.G.; Maia, A.F.; Bocalini, D.S. Exercise-Induced Muscle Damage after a High-Intensity Interval Exercise Session: Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 7082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawamura, T.; Muraoka, I. Exercise-Induced Oxidative Stress and the Effects of Antioxidant Intake from a Physiological Viewpoint. Antioxidants 2018, 7, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitti, S.; Bruneau, M.; Bisgrove, L.; Grey, S.; Levine, S.; Mattern, C.; Faller, J. Effects of a Single Dose of a Betalain-Rich Concentrate on Determinants of Running Performance and Recovery Muscle Blood Flow: A Randomized, Triple-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Crossover Trial. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aucouturier, J.; Boissière, J.; Pawlak-Chaouch, M.; Cuvelier, G.; Gamelin, F.-X. Effect of Dietary Nitrate Supplementation on Tolerance to Supramaximal Intensity Intermittent Exercise. Nitric Oxide 2015, 49, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonvik, K.L.; Nyakayiru, J.; Van Dijk, J.W.; Maase, K.; Ballak, S.B.; Senden, J.M.G.; Van Loon, L.J.C.; Verdijk, L.B. Repeated-Sprint Performance and Plasma Responses Following Beetroot Juice Supplementation Do Not Differ between Recreational, Competitive and Elite Sprint Athletes. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2018, 18, 524–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, A.J.; Yamada, T.; Rassier, D.E.; Andersson, D.C.; Westerblad, H.; Lanner, J.T. Reactive Oxygen/Nitrogen Species and Contractile Function in Skeletal Muscle during Fatigue and Recovery. J. Physiol. 2016, 594, 5149–5160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisafulli, D.L.; Buddhadev, H.H.; Brilla, L.R.; Chalmers, G.R.; Suprak, D.N.; San Juan, J.G. Creatine-Electrolyte Supplementation Improves Repeated Sprint Cycling Performance: A Double Blind Randomized Control Study. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2018, 15, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Oorschot, J.W.M.; Schmitz, J.P.J.; Webb, A.; Nicolay, K.; Jeneson, J.A.L.; Kan, H.E. 31P MR Spectroscopy and Computational Modeling Identify a Direct Relation between Pi Content of an Alkaline Compartment in Resting Muscle and Phosphocreatine Resynthesis Kinetics in Active Muscle in Humans. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e76628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.M.; Thompson, C.; Wylie, L.J.; Vanhatalo, A. Dietary Nitrate and Physical Performance. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2018, 38, 303–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, M.-J.; Chan, H.-L.; Huang, Y.-Z.; Lin, J.-H.; Hsu, H.-H.; Chang, Y.-J. Mechanism of Fatigue Induced by Different Cycling Paradigms with Equivalent Dosage. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Debold, E.P.; Westerblad, H. New Insights into the Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms of Skeletal Muscle Fatigue: The Marion J. Siegman Award Lectureships. Am. J. Physiol.-Cell Physiol. 2024, 327, C946–C958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Margaritelis, N.V.; Nastos, G.G.; Vasileiadou, O.; Chatzinikolaou, P.N.; Theodorou, A.A.; Paschalis, V.; Vrabas, I.S.; Kyparos, A.; Fatouros, I.G.; Nikolaidis, M.G. Inter-Individual Variability in Redox and Performance Responses after Antioxidant Supplementation: A Randomized Double Blind Crossover Study. Acta Physiol. 2023, 238, e14017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Adekolurejo, O.O.; Wang, B.; McDermott, K.; Do, T.; Marshall, L.J.; Boesch, C. Bioavailability and Excretion Profile of Betacyanins—Variability and Correlations between Different Excretion Routes. Food Chem. 2024, 437, 137663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, A.K.A.; Stellingwerff, T.; Smith, E.S.; Martin, D.T.; Mujika, I.; Goosey-Tolfrey, V.L.; Sheppard, J.; Burke, L.M. Defining Training and Performance Caliber: A Participant Classification Framework. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2022, 17, 317–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurlow, F.; Weakley, J.; Townshend, A.D.; Timmins, R.G.; Morrison, M.; McLaren, S.J. The Acute Demands of Repeated-Sprint Training on Physiological, Neuromuscular, Perceptual and Performance Outcomes in Team Sport Athletes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2023, 53, 1609–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Values |

|---|---|

| N (M/F) | 18 (15/3) |

| Age (yr) | 38.83 ± 8.09 |

| Height (cm) | 176.86 ± 9.60 |

| Weight (kg) | 73.23 ± 10.95 |

| Weekly training (h) | 9.68 ± 3.09 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vitti, S.; Smith, M.E.; Killip, S.; Sarkisov, A.; Frattellone, G.; Mattern, C.; Faller, J. One Week of a Betalain-Rich Beetroot Concentrate Does Not Improve 4 km Time-Trial Performance but Impairs Repeated Sprint Cycling Performance in Trained Cyclists. Physiologia 2025, 5, 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/physiologia5040054

Vitti S, Smith ME, Killip S, Sarkisov A, Frattellone G, Mattern C, Faller J. One Week of a Betalain-Rich Beetroot Concentrate Does Not Improve 4 km Time-Trial Performance but Impairs Repeated Sprint Cycling Performance in Trained Cyclists. Physiologia. 2025; 5(4):54. https://doi.org/10.3390/physiologia5040054

Chicago/Turabian StyleVitti, Steven, Meghan E. Smith, Sean Killip, Alyssa Sarkisov, Grace Frattellone, Craig Mattern, and Justin Faller. 2025. "One Week of a Betalain-Rich Beetroot Concentrate Does Not Improve 4 km Time-Trial Performance but Impairs Repeated Sprint Cycling Performance in Trained Cyclists" Physiologia 5, no. 4: 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/physiologia5040054

APA StyleVitti, S., Smith, M. E., Killip, S., Sarkisov, A., Frattellone, G., Mattern, C., & Faller, J. (2025). One Week of a Betalain-Rich Beetroot Concentrate Does Not Improve 4 km Time-Trial Performance but Impairs Repeated Sprint Cycling Performance in Trained Cyclists. Physiologia, 5(4), 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/physiologia5040054