Abstract

Dementia is a progressive condition that affects cognition, communication, mobility, and independence, posing growing challenges for individuals, caregivers, and healthcare systems. While traditional care models often focus on symptom management in later stages, emerging artificial intelligence (AI) technologies offer new opportunities for proactive and personalized support across the dementia trajectory. This concept paper presents the Assistive Intelligence framework, which aligns AI-powered interventions with each stage of dementia: preclinical, mild, moderate, and severe. These are mapped across four core domains: cognition, mental health, physical health and independence, and caregiver support. We illustrate how AI applications, including generative AI, natural language processing, and sensor-based monitoring, can enable early detection, cognitive stimulation, emotional support, safe daily functioning, and reduced caregiver burden. The paper also addresses critical implementation considerations such as interoperability, usability, and scalability, and examines ethical challenges related to privacy, fairness, and explainability. We propose a research and innovation roadmap to guide the responsible development, validation, and dissemination of AI technologies that are adaptive, inclusive, and centered on individual well-being. By advancing this framework, we aim to promote equitable and person-centered dementia care that evolves with individuals’ changing needs.

1. Introduction

Dementia is a complex, progressive syndrome characterized by significant impairment in cognitive functioning, mobility, communication, and the ability to perform everyday tasks independently. As a major global health concern, dementia currently affects over 55 million individuals worldwide, with prevalence projected to nearly triple by 2050 due to population aging [1]. The trajectory of dementia from subtle preclinical changes to severe functional impairment poses escalating challenges for healthcare systems, caregivers, and families, straining both formal care resources and informal caregiving networks [2].

Traditional dementia care often centers on late-stage symptom management, while offering few personalized, proactive interventions tailored to an individual’s changing needs across disease stages [3]. Non-personalized assistive technologies frequently offer limited flexibility, resulting in decreased adoption, reduced effectiveness, and unmet patient needs [4,5]. Recent advancements in Artificial Intelligence (AI), including Generative AI (Gen AI), machine learning, natural language processing, and sensor-driven technologies, present unprecedented opportunities to transform dementia care [6,7]. AI can proactively adapt to the dynamic and personalized requirements of individuals at different dementia stages, addressing critical gaps in care delivery [8].

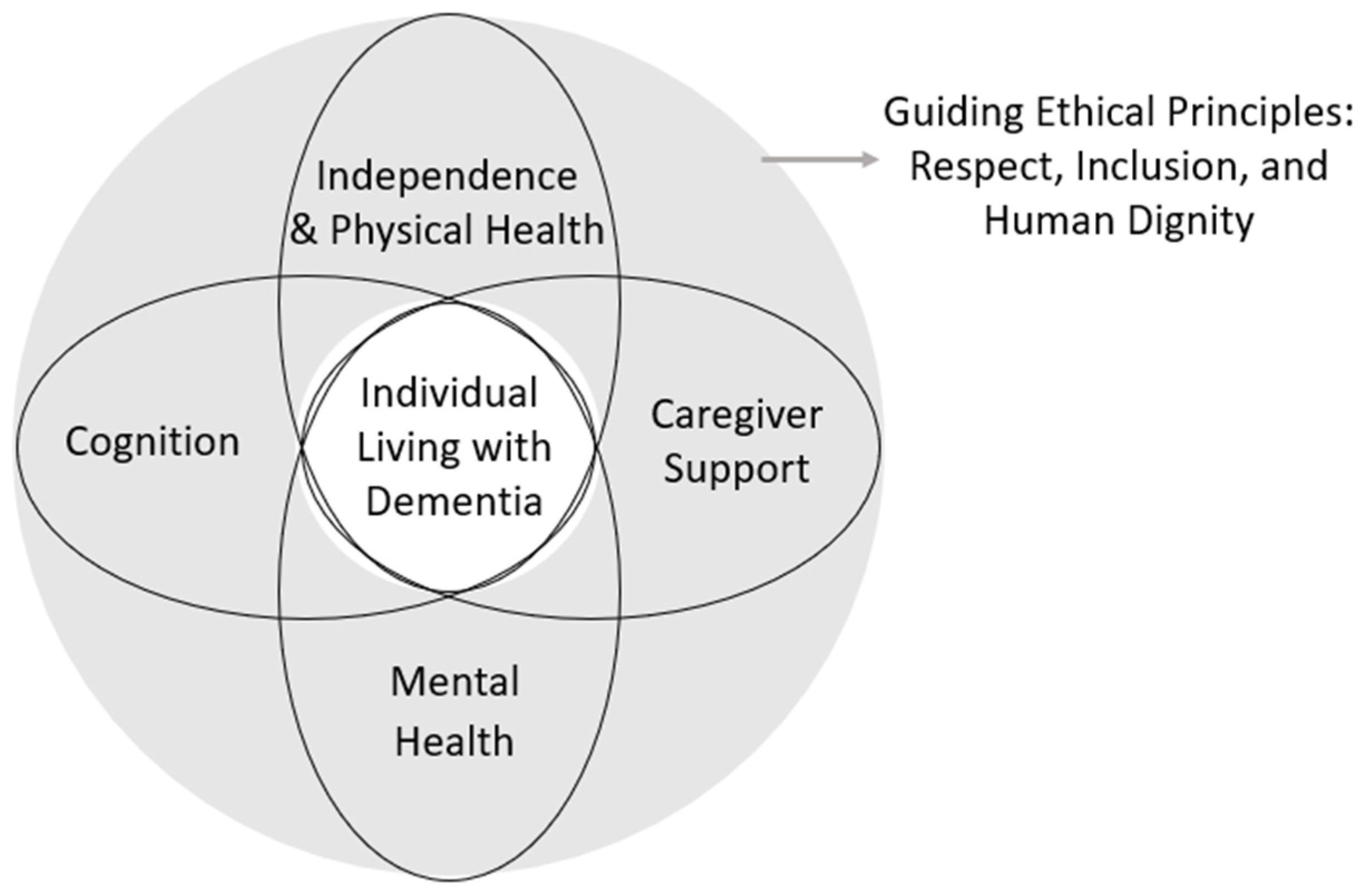

This paper proposes a novel, structured framework that systematically aligns AI-powered technologies with each clinical stage of dementia (Preclinical, Mild, Moderate, Severe) across four essential domains: cognition, mental health, independence and physical health, and caregiver support. Our objective is to illustrate how stage-specific, domain-targeted AI solutions can significantly enhance quality of life, support dignity, reduce caregiver burden, and foster sustained independence in individuals living with dementia.

2. Background and Current Gaps

2.1. Dementia Trajectory Across Stages: Preclinical, Mild, Moderate, Severe

Dementia encompasses a spectrum of progressive cognitive and functional decline, typically classified into four key clinical stages: (1) Preclinical: Subtle cognitive changes without significant interference in daily life, often detectable only through sensitive neuropsychological tests or biomarkers. (2) Mild: Noticeable memory impairments, difficulty managing complex tasks, and increased reliance on reminders or structured support systems. (3) Moderate: Significant cognitive decline impacting routine tasks, increased disorientation, noticeable language deficits, and growing dependence on caregivers for safety and support. (4) Severe: Profound cognitive impairment, minimal communication ability, full dependence on caregivers for basic activities, and often limited mobility. Each stage presents distinct challenges, requiring targeted and adaptable interventions tailored to evolving needs [9,10].

2.2. Limitations of Conventional and Non-Personalized Assistive Technologies

Traditional dementia care has primarily emphasized symptom management in moderate-to-severe stages, frequently overlooking opportunities for proactive early-stage intervention. Many conventional strategies, including caregiver assistance, pharmacological treatments, and basic assistive devices, lack personalized components, rarely adapting dynamically to the progressive trajectory of dementia [4,11]. This rigidity often limits their effectiveness and usability, worsening patient distress and caregiver burden [12]. Moreover, assistive technologies currently available for dementia care are often generic, failing to accommodate individual differences in cognitive capacity, preferences, cultural contexts, and the trajectory of disease progression [12,13]. Common shortcomings include: (1) static functionality, where devices provide fixed assistance routines that do not evolve with the individual’s cognitive decline or shifting preferences [14]; (2) issues with fragmentation as many assistive technologies operate in isolation without interoperability, forcing users and caregivers to juggle multiple disconnected tools that duplicate functions, collect data inconsistently, and complicate the overall care process [15,16]; and (3) usability barriers, as designs rarely incorporate age-related sensory, cognitive, or physical limitations, resulting in suboptimal adoption rates and frustration among users [17,18,19,20]. Such limitations underscore the urgent need for more responsive, integrated, and personalized technological interventions.

2.3. The Emerging Role of AI and GenAI in Dementia Care

Advances in AI are beginning to transform dementia care, from early detection to cognitive and emotional support. Machine learning models applied to speech, motor behavior, gait analytics, and digital biomarker patterns show promise in identifying mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and early-stage dementia before clinical symptoms fully emerge [21,22]. For example, speech-based AI algorithms have achieved near-80% accuracy in predicting progression from MCI to Alzheimer’s disease over multi-year follow-up periods [23]. Additionally, multimodal AI approaches that combine acoustic, linguistic, and behavioral features have improved dementia screening benchmarks over standard baselines [24]. AI has also been applied to support caregivers and improve the quality of life. Preliminary reviews note AI-driven dashboards and alert systems that consolidate wearable or ambient sensor data to help caregivers anticipate behavioral episodes or health risks, although most implementations remain in early development phases and small trials [25,26]. GenAI platforms are also being explored for cognitive stimulation and personalized engagement. Pilot studies of applications like Aikomi in care-home environments have shown high levels of user engagement (>40 on rating scales) and spontaneous communication among residents with dementia, suggesting the potential for personalized, AI-informed interventions that adapt over time [27]. However, longitudinal evidence on scalable GenAI-supported interventions remains limited.

2.4. Gaps in the Current Technological Landscape

Despite rapid innovation, AI-driven dementia tools remain largely fragmented and siloed. Many solutions, such as cognitive-training apps, fall detection systems, or reminder tools, are developed independently and lack interoperability. Caregivers often need to manage multiple tools separately, leading to redundancy and fragmented data collection [25]. This fragmentation contributes to cognitive overload and usability challenges, with older adults and caregivers reporting technology fatigue and inconsistent adoption rates [28]. More importantly, it prevents patients from using the full potential of AI, as the data collected by one sensor can benefit services provided by other applications. Another major limitation is the lack of personalization and longitudinal adaptability. Most AI applications currently offer static experiences, fixed difficulty in cognitive tasks, or one-size-fits-all reminders that do not adjust as user ability or preferences evolve. Research highlights that such rigidity undermines engagement and long-term efficacy, especially in progressive conditions like dementia [27,28]. Personalized platforms that adapt content over time remain scarce, limiting opportunities for sustained cognitive benefit and user trust.

These limitations underscore the need for a structured framework that aligns AI tools with core domains of dementia care, such as cognition, mental health, independence and daily functioning, and caregiver support, while emphasizing ethical and user-centered design. Such a framework can guide integration, interoperability, and personalization across domains, ensuring that AI applications function cohesively and adapt over time. This conceptual organization is elaborated in the following section to demonstrate how stage- and domain-specific AI interventions can be systematically deployed to support dignity, independence, and caregiver effectiveness among individuals with dementia.

This manuscript utilizes a narrative review of published literature. Articles were identified through targeted searches in PubMed and Google Scholar using combinations of terms including ‘AI’, ‘dementia’, ‘assistive technology’, ‘caregiver support’, and ‘cognitive monitoring’. Priority was given to peer-reviewed studies, feasibility trials, systematic reviews, and real-world implementation reports with relevance to stage-specific dementia care. While not a systematic review, this approach ensures inclusion of representative and impactful work across clinical, technological, and ethical domains.

2.5. AI Domain Framework

In the following section, we will outline how AI is revolutionizing early detection through digital biomarkers, enhancing diagnostic accuracy, providing novel therapeutic interventions, supporting emotional well-being, fostering independence, and alleviating the significant burden placed on caregivers. While the field is still in its early stages of development, the evidence points toward a future where AI-powered assistive technologies are integral to improving the quality of life for millions of individuals living with dementia and those who care for them [25].

- A.

- Cognition (Early Detection and Cognitive Stimulation)

AI technologies are increasingly used for early detection of dementia and mild cognitive impairment. Machine learning models can analyze subtle patterns in everyday technology use, speech, and mobility to detect cognitive decline years before clinical diagnosis. For example, automated speech analysis (using both acoustic and linguistic features) can distinguish early dementia with up to ~94% accuracy [29], and one study predicted progression from MCI to Alzheimer’s with ~78% accuracy by examining speech from neuropsychological exams [23]. Simple log data, such as technology use patterns, can also flag cognitive decline, with stopping the use of certain technologies being associated with a more severe cognitive decline and Alzheimer’s diagnoses a year later [30]. Gait and movement data are also revealing; wearable inertial sensors during mobility tasks have identified gait abnormalities indicative of cognitive impairment with over 97% sensitivity [22]. These AI-driven approaches provide inexpensive, non-invasive screening tools that can facilitate earlier interventions [29,30].

Beyond detection, AI enables cognitive stimulation and support tailored to an individual’s stage and needs. Generative AI and other techniques can provide personalized cognitive exercises, reminders, and reminiscence therapy. For instance, AI-powered reminiscence systems that present personalized prompts (e.g., family photos or music with conversational agents) have shown high engagement and stimulated communication in people with dementia [31]; in a pilot study, a digital reminiscence therapy app using an AI virtual assistant was well-received by older adults, who reported it “helpful, easy to use, and enjoyable,” and it improved their emotional well-being [31]. Such AI companions can adapt content to the user’s life history or current cognitive level, for example, simplifying a task or providing a hint when the user struggles, thereby maintaining an appropriate challenge level. Early-stage dementia patients might use a smart journaling chatbot or virtual assistant that subtly assesses their memory and thinking during conversation, while later-stage patients could benefit from AI that automatically adjusts game difficulty or provides calming storytelling sessions. The key is that AI systems can personalize and adjust in real-time, offering cognitive engagement that is neither too easy nor too frustrating [27]. This personalized, proactive cognitive support contrasts with static, one-size-fits-all tools and holds promises for prolonging mental function and quality of life.

- B.

- Mental Health (Emotion Detection and Social Support)

AI-powered systems are being developed to monitor and support the mental and emotional health of individuals with dementia. One application area is using AI to detect emotional states, such as agitation, anxiety, or depression, through analysis of speech, facial expressions, or behavior patterns. Research has shown that computer vision algorithms can accurately recognize facial expression changes related to pain or distress in nonverbal patients. For example, automated facial analysis models now achieve ~98% sensitivity and specificity in detecting different levels of pain from facial images [32]. In dementia care, similar AI tools can monitor micro-expressions, vocal tone, or sensor data (like restlessness measured via wearables) to catch early signs of agitation or mood changes. Early detection of these states allows caregivers or clinicians to intervene sooner (for instance, by redirecting a person before agitation escalates), thus improving safety and comfort. Some AI systems have been trained to interpret a person’s tone of voice or word choices as indicators of confusion or frustration, alerting caregivers to provide reassurance. Although these technologies are still maturing, initial studies demonstrate that AI emotion recognition can be reliable even when patients cannot self-report their feelings [33]. This capability is crucial in moderate to late-stage dementia, where individuals may struggle to communicate pain or depression.

AI is also being applied to conversational agents and social robots to support mood and reduce isolation in dementia. Loneliness and social withdrawal are major challenges, and AI-driven companions offer scalable ways to provide interaction and engagement. Recent systematic reviews of AI interventions for older adults report that technologies like voice-based virtual assistants and socially assistive robots have significantly reduced feelings of loneliness in many trials [34]. In six of nine studies, for example, using a social robot or AI companion led to measurable decreases in loneliness and improvements in emotional well-being among older users [34]. These AI companions can engage the person in conversation, remind them of happy memories, or even tell jokes and stories, acting as a form of cognitive behavioral support. Importantly, such systems can be available 24/7, offering consistent companionship that human caregivers often cannot sustain. Early pilots in dementia care homes have shown that residents interact willingly with AI-driven pet robots or chatbots, sometimes leading to increased positive emotions and social interaction during use [33]. Moreover, advanced conversational AI can maintain context over time, allowing it to address the person’s interests or worries (for example, the AI might recognize and respond if the individual is repeatedly asking about a family member). Finally, adaptive communication tools are emerging for individuals in late-stage dementia who may be nonverbal [35]. While still largely in prototype stages, voice-to-symbol or gesture-to-action technologies could greatly help those who can no longer form coherent speech. In summary, AI offers a toolkit to both monitor emotional well-being and actively foster social connection, from detecting unseen distress to providing companionship that alleviates depression and anxiety in people living with dementia.

- C.

- Independence and Physical Health (ADLs, Safety, and Health Monitoring)

AI-powered assistive technologies can profoundly support independence and physical health for people with dementia by assisting with both basic and instrumental activities of daily living (ADLs and IADLs) and by monitoring overall health and safety. In terms of Basic ADLs, smart-home technologies are being used to create safer, dementia-friendly environments [36,37]. For example, an AI-equipped home can automate routine functions like lighting and temperature control and provide prompts or reminders for self-care tasks [38]. Motion sensors and context-aware algorithms detect when a person enters a dark hallway at night and automatically switch on lights to prevent falls [39]. Similarly, sensors can remind someone to wash their hands or brush their teeth by playing a prompt if the task is forgotten. Importantly, these systems can adapt to the individual’s habits; for instance, if the resident usually wakes at 7 a.m., the system might gradually raise lighting and start a morning routine playlist to cue them to start the day. To support safety and mobility, AI-enhanced devices monitor gait and movement patterns to predict and prevent falls [40]. Wearable sensors (like smart shoe insoles or pendants) continuously track gait speed, balance, and activity; if the AI detects a deviation associated with fall risk (for instance, unusually shuffling steps or prolonged inactivity suggesting a fall), it can alert caregivers immediately [39]. Research shows that combining data from multiple sensors can reliably flag such risks; one study achieved over 94% accuracy in classifying abnormal movements and fall-related behaviors using an array of wearables and ambient sensors [22]. GPS-based mobility monitors are also used to support independence while preventing wandering incidents: if a person moves outside a predefined “safe zone”, the system can gently guide them back or notify caregivers [41]. Similarly, geo-fencing AI can thus enable a person with dementia to walk in their neighborhood more safely, preserving freedom of movement.

For Instrumental ADLs, AI offers tools to maintain autonomy in complex daily tasks. Medication adherence is a prime example [42]; smart pill dispensers coupled with AI scheduling can ensure medications are taken correctly. These dispensers can be programmed with the dosing schedule and will issue alerts (voice reminders, flashing lights) at the right times; if a dose is missed, the AI can prompt again after a short interval and notify a caregiver via a mobile app if the medication still is not taken [43]. Many such devices also log adherence data, so doctors and family can remotely monitor if pills are being skipped. A recent systematic review found dozens of innovative medication dispenser solutions, often integrating sensors and companion apps for caregivers, though it noted the importance of designing these systems to be user-friendly for older adults [43]. Beyond medications, meal preparation and home safety can be augmented with AI: smart kitchen systems use sensors on stoves and ovens to detect unsafe situations (like a burner left on) and either remind the user or automatically shut it off [44]. There are also AI-driven cooking assistants that guide individuals step-by-step through a recipe or daily meal prep, using verbal instructions and even computer vision to see if each step is completed [45]. For scheduling and navigation, digital assistants on smartphones or smart speakers can manage calendars and provide gentle voice reminders for appointments or tasks (“It’s Tuesday, time for your exercise class”). These assistants can learn the person’s routine and adjust reminders to their cognitive needs (e.g., giving more detailed instructions if the user is in a later disease stage).

Broader health monitoring is another domain where AI excels. Wearable health trackers (like smart watches, patches, or bed sensors) continuously collect vital signs such as heart rate, sleep patterns, activity levels, and even gait speed [46]. AI algorithms analyze this data to establish a personal baseline and can spot subtle changes that might indicate a problem, for instance, detecting increased restlessness and poor sleep over several nights could flag a possible urinary tract infection or pain issue, even before other obvious symptoms emerge. In one community dementia monitoring project, a multi-sensor network accurately predicted agitation and health deterioration events with very high accuracy (AUC > 0.97), allowing proactive care adjustments [47]. Likewise, ambient sensors throughout the home (motion detectors, smart thermostats, door sensors, etc.) feed into AI systems that learn the individual’s daily routines. If the person usually goes to the kitchen every morning but one day does not, the system can check in by playing a reminder (“It’s time for breakfast”) or alert a caregiver to do a safety check. Essentially, the home becomes a ubiquitous safety net, automatically detecting hazards and changes in health status. Studies have categorized these smart-home health technologies into functional monitoring (tracking daily activities and detecting anomalies like falls or wandering) and physiological monitoring (tracking health metrics), both of which significantly enhance independence and reduce the need for constant human supervision [39]. Early evidence suggests that such integrated systems can extend the time people with dementia live safely at home by preventing emergencies and providing assistance exactly when needed [39]. The challenge moving forward is to ensure these technologies are easy to use, respect privacy, and are tailored to the sensory/cognitive abilities of users (for example, using simple voice prompts and intuitive devices). When designed well, AI-powered assistance can empower individuals with dementia to maintain autonomy, managing daily living tasks with less frustration and risk.

- D.

- Caregiver Support (Monitoring, Alerts, and Decision Support)

AI-powered assistive technologies not only help individuals with dementia, but also directly support caregivers, both family members and professional carers, by reducing burdens and providing guidance [48,49,50]. One major contribution of AI is through wearables and ambient sensors that deliver real-time alerts, effectively acting as an extra set of eyes and ears so that caregivers do not have to supervise every moment [51]. For example, if an elderly person with dementia leaves the house unexpectedly at 2 a.m., a network of door sensors and GPS trackers can instantly notify the caregiver via smartphone, allowing for a quick response to ensure safety. Similarly, if the person falls or shows abnormal vital signs (like a dangerous heart rate or prolonged inactivity), the system generates an alarm. By catching issues early, these technologies relieve caregivers from the anxiety of “constant vigilance.” Studies have shown that smart home monitoring systems can reliably report meaningful deviations in a person’s behavior to caregivers in real-time [39]. In one comprehensive smart-home trial, sensors aggregated data on daily habits, posture, meals, and vitals and sent automatic alerts to caregivers when something was out of the ordinary, enabling prompt remote support while the patient aged in place [39]. This kind of continuous oversight means caregivers can rest or attend to other activities, confident that the AI will inform them if intervention is needed, significantly reducing stress and burnout. Wearable caregiver devices themselves are emerging too (for instance, a caregiver might wear a smart band that vibrates or texts them when an alert from the home system is triggered). By filtering out false alarms and only alerting for genuine issues, AI addresses “alarm fatigue” [52] and makes monitoring more efficient than traditional sensor systems.

Beyond alerts, AI can provide decision-support and personalized guidance for caregiving challenges. Managing behavioral symptoms (“responsive behaviors”) in dementia, such as agitation, aggression, wandering, or sundowning, is often difficult for family caregivers. Here, AI-driven applications can analyze data from the person’s daily patterns and suggest tailored strategies. For instance, if a wearable and smart calendar detects that agitation tends to spike in the late afternoon, a caregiving app might recommend engaging the person in a calming activity before that time or ensuring a nap after lunch. By mining large datasets of dementia care, AI systems begin to learn what interventions work best for specific scenarios and can coach caregivers through a chat interface or dashboard. One example is the CareHeroes app, which includes an AI chatbot that answers caregivers’ questions and offers tips; in a pilot study, caregivers who used CareHeroes for 3 months showed a significant decrease in depression symptoms, indicating that the app’s support eased their emotional burden [53]. Caregivers in the study particularly appreciated the chatbot feature, which could provide answers on demand (for example, how to handle a loved one’s repetitive questions) and offer reminders for self-care. Another emerging class of tools uses AI to integrate information from various sources, daily activity logs, the patient’s medical data, and even environmental sensors, into a unified care dashboard. These dashboards can highlight important trends (such as declining mobility or eating patterns) and even predict potential problems. For instance, an AI system might forecast an increased fall risk based on subtle gait changes and prompt the caregiver with: “Risk of fall is rising, consider a physiotherapy consultation or use of a walking aid.” In simulations, such AI-driven decision support has been shown to improve caregivers’ confidence and problem-solving abilities [49]. In a systematic review of AI for informal caregiving, researchers found that digital assistants can personalize information for caregivers and help coordinate care during emergencies or deviations from routine [49]. Importantly, these systems can prioritize explainability by communicating to the caregiver why an alert or suggestion is being made (for example, “exit-seeking behavior detected by motion sensor, possibly indicating anxiety. Try taking the person for a short walk.”). This transparency helps build trust in the AI recommendations and allows caregivers to learn and adapt their strategies.

Finally, AI tools can facilitate communication and coordination among the care team (family members, doctors, home aides) [54,55]. For example, CareMOBI (mhealth for Organization to Bolster Interconnectedness), a mobile app that links primary care providers to adult day health centers and family caregivers. In a feasibility study, CareMOBI was shown to be highly valuable and acceptable to users for facilitating secure, team-based communication and enabling the early identification of clinical changes through a shared log of daily health information [54]. With consent, an AI platform can automatically compile reports on the person’s status and progress, which caregivers can share with clinicians during check-ups to improve medical decisions [56]. By serving as an intelligent intermediary, AI ensures that important information (like a change in behavior or medication side effects) does not slip through the cracks between appointments. Early trials like the iSupport program [57], which is an online education tool for dementia caregivers now incorporating AI elements, have noted high user satisfaction and sustained engagement over 12 weeks, suggesting that caregivers are open to tech-based support when it is relevant and easy to use [53].

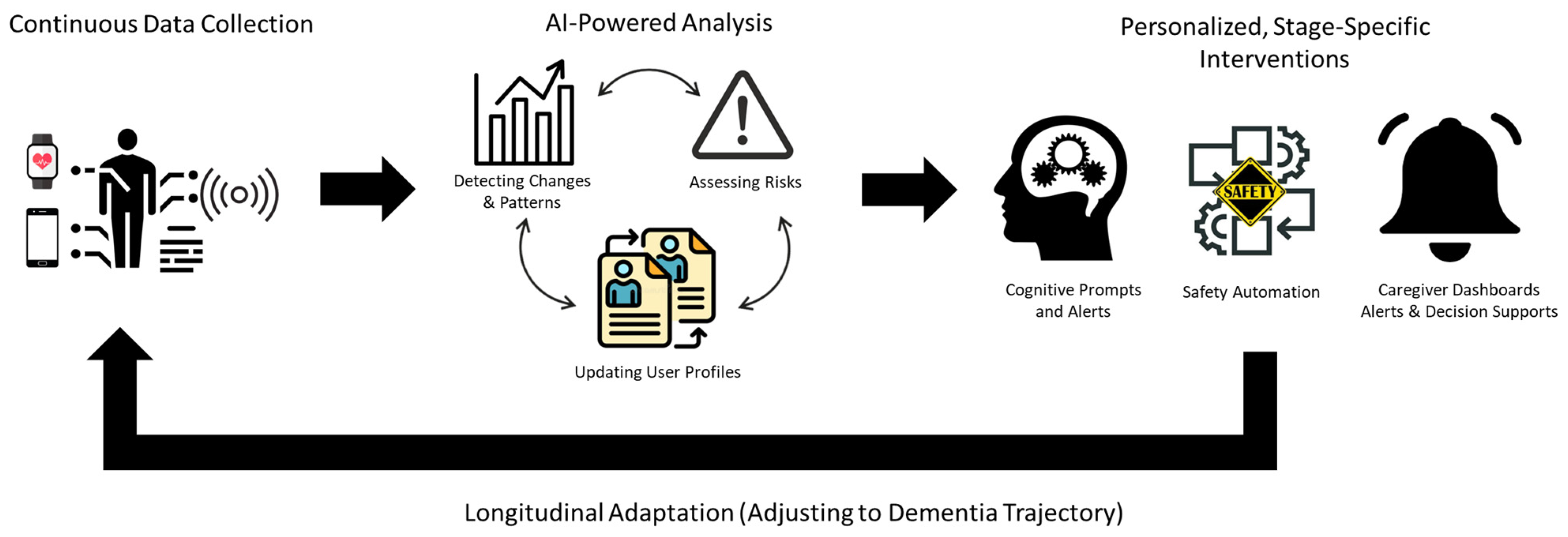

In summary, AI-powered assistive technologies span a broad spectrum of support, from early detection and cognitive stimulation to emotional monitoring and social connection, enhancing independence, safety, and health and reducing caregiver burden through real-time alerts and decision support. Together, these innovations can handle routine monitoring, predict and prevent crises, and provide personalized guidance for day-to-day care. This integrated, stage- and domain-specific approach not only reduces caregiver stress and burnout but also improves care continuity and outcomes for people with dementia. As these AI systems evolve, ongoing caregiver input and rigorous validation will be essential to ensure they are accurate, culturally appropriate, and aligned with real-world needs, while also addressing important ethical and social considerations discussed in the next section. Figure 1 presents the conceptual domains, illustrating how these domains map onto dementia care. In addition, Figure 2 illustrates the dynamic feedback loop that enables the system to adapt over time. This adaptive process begins with continuous data collection from a diverse ecosystem of apps and tools, including wearables, ambient sensors, and user interaction logs. This data is fed into the AI-Powered Analysis engine, which continuously detects changes and patterns, assesses risks (e.g., agitation, falls), and updates user profiles. Based on this real-time analysis, the system delivers Personalized, Stage-Specific Interventions back through these various apps and tools, such as displaying cognitive prompts on a smart display, triggering alerts on a caregiver’s mobile app, or initiating safety automation in the smart home environment. Crucially, the framework operates as a closed-loop system: the user’s response and subsequent data are fed back into the collection stage, allowing the AI to continuously self-adapt and personalize support along the dementia trajectory. Table 1 provides concrete examples of AI-powered assistive technologies tailored to each domain and stage and Table 2 provides a summary of AI Interventions by operational status.

Figure 1.

Assistive Intelligence Framework for AI-Powered Dementia Care. This framework centers the Individual Living with Dementia, intersecting four key domains: Cognition, Mental Health, Independence and Physical Health, and Caregiver Support. These domains are guided by overarching ethical principles of Respect, Inclusion, and Human Dignity, which inform AI design and deployment in dementia care contexts.

Figure 2.

The Assistive Intelligence Adaptive Feedback Loop. This dynamic, closed-loop system begins with continuous data collection from sensors, wearables, and mobile devices, which feeds into an AI-powered analysis engine. The engine detects behavioral and physiological patterns, assesses risks, and updates user profiles in real time. Based on these insights, the system delivers personalized, stage-specific interventions tailored to the user’s evolving cognitive and functional needs. The architecture also includes caregiver-facing features such as dashboards, alerts, and decision-support tools ensuring that both individuals with dementia and their caregivers benefit from timely, adaptive support. This feedback loop allows the system to continuously learn and self-adjust along the dementia trajectory.

Table 1.

AI Powered Assistive Technologies Across Dementia Phases.

Table 2.

Summary of AI Interventions by Operational Status.

Many performance metrics cited for AI applications (e.g., detection accuracy or sensitivity) are drawn from early-stage or pilot studies with small, homogeneous samples, controlled testing environments, or limited real-world validation. Readers should interpret these figures with caution, as scalability and generalizability remain open challenges across most AI-dementia research domains.

2.6. Ethical and Social Considerations

The use of AI-powered assistive technologies in dementia care brings important ethical and social challenges that must be carefully considered to support safe, fair, and trustworthy innovation.

2.7. Privacy and Data Protection

AI systems in dementia care collect extensive sensitive health and behavioral data, which heightens concerns around privacy, consent, and data misuse. There are significant risks around data leakage, inadequate anonymization, and unclear governance frameworks in smart-home and wearable systems used in long-term care [58]. Besides technical risks, Ghaiumy Anaraky has outlined human-factor considerations around privacy and has shown that older adults have unique privacy decision-making behaviors that need to be considered [18]. For example, the app should clearly outline the benefits of data disclosures to the older adult users [18], and avoid using dark design patterns such as disclosure defaults, which make older adults more concerned about technology tools [59]. Overall, AI should personalize disclosure prompts, policy communications, and technology education to the older adult users [19,60,61].

In sum, protecting users requires robust end-to-end encryption, strict access controls, transparent data usage policies, and consent mechanisms tailored to the cognitive circumstances of users.

2.8. Autonomy and Informed Consent

Dementia inherently impairs cognitive capacity, complicating standard informed consent practices. Studies highlight the need for supported decision-making processes or legal representatives to help protect the autonomy of people with dementia [62,63]. Research from different cultural settings also shows that ethical practices should respect local values [64,65], and caregiving roles to make consent procedures more appropriate and inclusive [63]. For example, having more technology caregivers increases older adult users’ self-efficacy and comfort with using technology features [66]. Buhr et al. (2025) suggest using an “ethics-by-design” approach, where people with dementia and their caregivers help create value-based profiles to guide how AI systems make decisions in a way that reflects users’ beliefs and cultural backgrounds [62].

2.9. Fairness and Algorithmic Bias

AI models trained on biased data can worsen health disparities by failing to accurately detect or diagnose dementia in underserved or underrepresented groups. Yuan et al. (2023) found significant sex, racial, and socioeconomic biases in predictive models for Alzheimer’s, with higher error rates among minority groups [67]. Without active efforts in bias detection, correction, and model validation across demographic strata, AI systems may disadvantage marginalized groups and undermine equitable care delivery.

To mitigate these risks, active bias detection and correction methods are essential. These can include pre-processing techniques like re-sampling or re-weighting training data to ensure equitable representation [68,69], in-processing methods that add fairness constraints directly into the model’s optimization [70], and post-processing adjustments to model outputs to ensure parity across groups [71,72]. Continuous auditing of model performance on disaggregated demographic data will also be critical for post-deployment fairness [73].

2.10. Explainability and Trust

Complex AI models, especially black-box deep learning systems, often lack transparency, making it difficult for users and caregivers to understand how decisions are made. This lack of clarity can reduce trust and confidence among both clinicians and users [74]. To address this, Explainable AI approaches are essential. For example, Medani et al. (2025) show that AI systems designed with explainability in mind can improve dementia prediction accuracy while also making the decision process more understandable in clinical settings [75].

2.11. Other Considerations for Implementation of AI Powered Assistive Technologies for Dementia

To translate the proposed AI framework into practical, real-world dementia care, several crucial implementation dimensions must be addressed, such as sensor ecosystem integration, co-designed caregiver-AI interfaces, usability and accessibility, and cost-effectiveness and scalability. By addressing these areas, feasibility, acceptance, and impact across care settings can be improved.

2.12. Sensor Ecosystem Integration

Integrated sensor networks are foundational for AI-driven interventions in dementia care, enabling real-time monitoring and decision-making. Ensuring interoperability across wearables, ambient sensors, voice assistants, and smart-home technologies requires standardized data-sharing protocols and system integration standards [76]. For health-related data, this includes frameworks such as Health Level Seven Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources (HL7 FHIR) [77], which enables secure, structured exchange of clinical and sensor data between systems. For Internet of Things (IoT)-enabled environments, protocols such as Message Queuing Telemetry Transport (MQTT) [78] and Constrained Application Protocol (CoAP) [79] are commonly used for lightweight, real-time device communication. Emerging integration platforms that combine HL7 FHIR with edge-computing and IoT layers are particularly well-suited for AI-powered dementia care applications that require continuous, multi-modal input and clinical coordination. IoT-enabled systems have demonstrated high reliability and classification accuracy (>99% for activity inference, >94% for anomaly detection) when combining multiple sensor modalities [80]. Additionally, accurate detection capabilities—such as predicting agitation events with AUC-ROC > 0.97 in community-based dementia monitoring—demonstrate the value of sensor-enabled predictive analytics [47]. Additionally, ensuring data security and privacy remains essential, given the sensitivity of health behavior data captured by these systems.

Several large-scale European initiatives (Table 3) have already demonstrated the potential of interoperable, scalable, and user-centered digital ecosystems for active and healthy aging. Notably, the Pilots for Healthy and Active Ageing (PHArA-ON) project has developed customizable, open platforms that integrate IoT, AI, robotics, wearable sensors, big data analytics, and cloud-based services across multiple pilot sites in Europe [81]. Similar efforts such as ACTIVAGE [82] and Smart and Healthy Ageing through People Engaging in Supportive Systems (SHAPES) [83] are emphasize real-world deployment, device interoperability, and sustained support for autonomy and care coordination. While these projects do not focus solely on Alzheimer’s disease, their architectures and objectives align closely with AI-powered dementia care particularly in addressing modularity, personalization, and cross-sector collaboration.

Table 3.

Comparison between AI/IoT Aging Platforms.

Preliminary findings from European initiatives such as SHAPES and ACTIVAGE suggest that user acceptance and engagement can vary between stakeholder groups. Older users often benefit from passive, low-burden technologies with minimal interface complexity, while caregivers show stronger engagement when provided with customizable dashboards, alerts, and actionable information for care coordination [81]. Importantly, low patient engagement was not necessarily due to technological ineffectiveness but reflected mismatches between system design and user needs [83]. Lessons from these trials suggest that older adults benefit most from passive data collection and simple, stable interactions, while caregivers require more detailed dashboards and configurable modules. Our framework reflects these insights through its layered design: a Continuous Data Collection layer enables low-burden, passive monitoring; the AI-Powered Personalization layer adjusts support dynamically to the user’s evolving cognitive profile; and the Caregiver Support layer is designed to be more interactive and customizable, offering actionable alerts, trend summaries, and decision support features tailored to care workflows.

2.13. Caregiver–AI Interface Co-Design

Engaging caregivers in participatory design ensures that AI solutions resonate with real-world care. A mixed-methods study of decision-support systems integrating assistive technologies emphasized that user involvement improves relevance, usability, and acceptance [76]. Reviews also underscore AI’s ability to support decision-making and stress reduction among informal caregivers when designs offer transparency into alerts and recommendations [49]. Effective interfaces should provide clear insight into how data is used and allow caregivers meaningful control and customization.

2.14. Usability and Accessibility for Older Adults

User interfaces must reflect age-related sensory, cognitive, and motor differences. For example, older adults are more loss-aversive than younger adults [84] and an app can leverage this to be more motivating for older adults: instead of prompting the user with a gain-framed message of “to get fit, please walk”, it can prompt users with a loss-framed message of “to stay fit, please walk”. Systematic usability analyses for dementia technologies show that intuitive design, multimodal feedback, and adaptive features significantly enhance engagement among older adults [12]. Smart home health technologies have demonstrated barriers to adoption, where usability, social acceptability, and physical access are inadequate [39]. Adaptive interfaces that respond to cognitive decline or visual/hearing limitations help reduce frustration and support sustained use.

2.15. Cost, Scalability, and Economic Viability

Affordability and scalability are key to widespread adoption. Digital assistive technologies show promise in supporting aging-in-place and improving independence, though barriers related to cost and system complexity [85]. Pilot interventions like Brain CareNotes demonstrate scalable caregiver-focused mobile apps that are usable and well-accepted, highlighting the potential for cost-effective deployment [86]. Finally, cloud-based or subscription models and partnerships with insurers and policymakers are essential to integrate AI solutions into reimbursable care frameworks and ensure equitable access.

While a full cost-effectiveness analysis is beyond the scope of this paper, several core assumptions can inform future economic modeling of AI-powered dementia interventions. AI-integrated smart-home sensors, wearable devices, and mobile applications are estimated at $300–$1500 per household, depending on complexity (e.g., camera-based vs. motion-only sensors), with AI dashboard integration ranging from $50–$100/month for cloud-based services. Initial setup and caregiver training are projected at 3–5 h per home, at labor costs of approximately $40–$60/h, in line with smart-home health technology deployment reports [87,88]. Studies suggest that AI-assisted monitoring and early detection can reduce emergency visits and inpatient days [89] primarily by preventing falls, wandering, and unmanaged behavioral symptoms. For example, the study by Economic evaluation of passive monitoring technology for seniors projected savings of approximately US $5069 per person per year using passive monitoring technology in older adults [88]. These preliminary figures support the feasibility of cost-effective scaling, particularly in home- and community-based settings. A formal economic evaluation, including quality-adjusted life years and caregiver productivity impacts, will be an essential next step.

2.16. Research and Innovation Roadmap

To advance the Assistive Intelligence framework from concept to clinical implementation requires a structured research agenda that prioritizes feasibility, clinical validation, personalization, and long-term engagement. Rigorous studies and interdisciplinary collaboration will be essential to ensure that AI-powered technologies are safe, effective, and responsive to the evolving needs of individuals with dementia and their caregivers. For example, the CareHeroes chatbot intervention showed potential to reduce caregiver depression and improve usability in real-world settings [53], and the iSupport program for carers supporting people with rare dementias demonstrated strong user retention and acceptability in a 12-week feasibility study [90]. These early efforts validate the potential of AI tools to be both practical and well-received by users. However, scaling such interventions requires rigorous clinical validation across care settings. AI systems like Monash dementia detection platform [91] have shown high accuracy for early identification of cognitive decline, yet they require further clinical trials to establish their safety, efficacy, and generalizability (Monash University, 2025). Real-world effectiveness must also be evaluated in diverse environments beyond controlled clinical contexts, including home and community care, to ensure broad applicability. The development of adaptive AI systems that can evolve with the cognitive and behavioral changes typical in dementia is also equally important. Personalized systems have shown promise in tailoring support based on individual profiles and real-time data, while simulated studies combining reinforcement learning with large language models have demonstrated the feasibility of emotionally responsive, dynamic AI interactions [92]. To support sustained engagement and effectiveness, longitudinal research is needed to assess how these technologies perform over time and respond to users’ changing needs. Collectively, these research priorities provide a roadmap for responsibly scaling AI-enabled tools that are ethical, adaptive, and clinically impactful in real-world dementia care.

In conclusion, AI technologies hold significant promise to enhance dementia care by delivering personalized, adaptive, and proactive support across disease stages. The Assistive Intelligence framework provides a structured approach to aligning AI tools with key domains of care like cognition, mental health, independence and physical health, and caregiver support—while centering ethical and user-focused design. To translate this potential into real-world impact, future efforts must emphasize clinical validation, interdisciplinary collaboration, and equitable access. With responsible development, AI can help create more effective, inclusive, and sustainable dementia care systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.M. and R.G.A.; methodology, B.M. and R.G.A.; resources, B.M. and R.G.A.; data curation, B.M. and R.G.A.; writing—original draft preparation, B.M. and R.G.A.; writing—review and editing, B.M. and R.G.A.; visualization, B.M. and R.G.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Nichols, E.; Steinmetz, J.D.; Vollset, S.E.; Fukutaki, K.; Chalek, J.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdoli, A.; Abualhasan, A.; Abu-Gharbieh, E.; Akram, T.T. Estimation of the global prevalence of dementia in 2019 and forecasted prevalence in 2050: An analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Public Health 2022, 7, e105–e125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alzheimer’s Association. 2024 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2024, 8, 131–168. [Google Scholar]

- Palmdorf, S.; Stark, A.L.; Nadolny, S.; Eliaß, G.; Karlheim, C.; Kreisel, S.H.; Gruschka, T.; Trompetter, E.; Dockweiler, C. Technology-assisted home care for people with dementia and their relatives: Scoping review. JMIR Aging 2021, 4, e25307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibson, G.; Dickinson, C.; Brittain, K.; Robinson, L. The everyday use of assistive technology by people with dementia and their family carers: A qualitative study. BMC Geriatr. 2015, 15, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly Lynn, J.; Rondón-Sulbarán, J.; Quinn, E.; Ryan, A.; McCormack, B.; Martin, S. A systematic review of electronic assistive technology within supporting living environments for people with dementia. Dementia 2019, 18, 2371–2435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kameyama, M.; Umeda-Kameyama, Y. Applications of artificial intelligence in dementia. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2024, 24, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Arriba-Pérez, F.; García-Méndez, S.; González-Castaño, F.J.; Costa-Montenegro, E. Automatic detection of cognitive impairment in elderly people using an entertainment chatbot with Natural Language Processing capabilities. J. Ambient Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 2023, 14, 16283–16298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyall, D.M.; Kormilitzin, A.; Lancaster, C.; Sousa, J.; Petermann-Rocha, F.; Buckley, C.; Harshfield, E.L.; Iveson, M.H.; Madan, C.R.; McArdle, R. Artificial intelligence for dementia—Applied models and digital health. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2023, 19, 5872–5884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, M.; O’Connell, T.; Johnson, S.; Cline, S.; Merikle, E.; Martenyi, F.; Simpson, K. Estimating Alzheimer’s disease progression rates from normal cognition through mild cognitive impairment and stages of dementia. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2018, 15, 777–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharre, D.W. Preclinical, prodromal, and dementia stages of Alzheimer’s disease. Pr. Neurol. 2019, 15, 36–47. [Google Scholar]

- Goodall, G.; Taraldsen, K.; Granbo, R.; Serrano, J.A. Towards personalized dementia care through meaningful activities supported by technology: A multisite qualitative study with care professionals. BMC Geriatr. 2021, 21, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, S.-Y.; Zaslavsky, O.; Berridge, C. Technology usability for people living with dementia: Concept analysis. JMIR Aging 2024, 7, e51987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thordardottir, B.; Malmgren Fänge, A.; Lethin, C.; Rodriguez Gatta, D.; Chiatti, C. Acceptance and use of innovative assistive technologies among people with cognitive impairment and their caregivers: A systematic review. BioMed Res. Int. 2019, 2019, 9196729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Nordberg, O.E.; Rongve, A.; Bachinski, M.; Fjeld, M. State-of-the-Art HCI for Dementia Care: A Scoping Review of Recent Technological Advances. J. Dement. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2025, 2, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brookman, R.; Parker, S.; Hoon, L.; Ono, A.; Fukayama, A.; Matsukawa, H.; Harris, C.B. Technology for dementia care: What would good technology look like and do, from carers’ perspectives? BMC Geriatr. 2023, 23, 867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollmer Dahlke, D.; Ory, M.G. Emerging issues of intelligent assistive technology use among people with dementia and their caregivers: A US perspective. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, L.D.; Husebo, B.S.; Vislapuu, M. Promotors and barriers to the implementation and adoption of assistive technology and telecare for people with dementia and their caregivers: A systematic review of the literature. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaiumy Anaraky, R.; Byrne, K.A.; Wisniewski, P.J.; Page, X.; Knijnenburg, B. To disclose or not to disclose: Examining the privacy decision-making processes of older vs. younger adults. In Proceedings of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Yokohama, Japan, 8–13 May 2021; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Ghaiumy Anaraky, R.; Bulgurcu, B.; Byrne, K.; Li, Y.; Cho, H.; Knijnenburg, B. Would You Preserve Your Privacy or Enhance it? How to Best Frame Privacy Interventions for Older and Younger Users. In Proceedings of the 58th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Hilton Waikoloa Village, HI, USA, 7–10 January 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Ghaiumy Anaraky, R.; Schuster, A.M.; Van Fossen, J.; Nov, O.; Cotten, S. Increased Use of Asocial Technologies Is Associated with Reduced Well-being Among Older Adults. In Proceedings of the 2025 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Hilton Waikoloa Village, HI, USA, 7–10 January 2025; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, S.A.; Lee, E.E.; Jeste, D.V.; Van Patten, R.; Twamley, E.W.; Nebeker, C.; Yamada, Y.; Kim, H.-C.; Depp, C.A. Artificial intelligence approaches to predicting and detecting cognitive decline in older adults: A conceptual review. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 284, 112732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahul, R.M.; Ambadekar, S.; Dhanvijay, D.M.; Dhanvijay, M.M.; Dudhedia, M.A.; Gaikwad, V.; Kanawade, B.; Pansare, J.; Bodkhe, B.; Gawande, S. Multimodal approaches and AI-driven innovations in dementia diagnosis: A systematic review. Discov. Artif. Intell. 2025, 5, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amini, S.; Hao, B.; Yang, J.; Karjadi, C.; Kolachalama, V.B.; Au, R.; Paschalidis, I.C. Prediction of Alzheimer’s disease progression within 6 years using speech: A novel approach leveraging language models. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2024, 20, 5262–5270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, L.; Sharma, A.; Gebhardt, A.; Colonel, J. Predicting Cognitive Decline: A Multimodal AI Approach to Dementia Screening from Speech. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE International Conference on AI and Data Analytics (ICAD), Medford, MA, USA, 24 June 2025; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Steijger, D.; Christie, H.; Aarts, S.; IJselsteijn, W.; Verbeek, H.; de Vugt, M. Use of artificial intelligence to support quality of life of people with dementia: A scoping review. Ageing Res. Rev. 2025, 108, 102741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.; Jiang, L.; Chen, X.S.; Feng, Y. Interactive AI Technology for Dementia Caregivers: Needs and Implementation Evidence. J. Technol. Hum. Serv. 2025, 43, 91–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hird, N.; Osaki, T.; Ghosh, S.; Palaniappan, S.K.; Maeda, K. Enabling personalization for digital cognitive stimulation to support communication with people with dementia: Pilot intervention study as a prelude to AI development. JMIR Form. Res. 2024, 8, e51732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Contreras-Somoza, L.; Irazoki, E.; Toribio-Guzmán, J.; de la Torre-Díez, I.; Diaz-Baquero, A.; Parra-Vidales, E.; Perea-Bartolomé, M.; Franco-Martín, M. Usability and user experience of cognitive intervention technologies for elderly people with MCI or dementia: A systematic review. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 636116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.; Wang, X.; Lawler, K.; Garg, S.; Bai, Q.; Alty, J. Applications of artificial intelligence to aid early detection of dementia: A scoping review on current capabilities and future directions. J. Biomed. Inform. 2022, 127, 104030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaiumy Anaraky, R.; Schuster, A.M.; Cotten, S.R. Can changes in older adults’ technology use patterns be used to detect cognitive decline? Gerontologist 2024, 64, gnad158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, J.; Liang, T.; Hasan, W.U.; Zaman, K.T.; Du, Y.; Xie, B.; Tao, C. Promoting personalized reminiscence among cognitively intact older adults through an AI-driven interactive multimodal photo album: Development and usability study. JMIR Aging 2024, 7, e49415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, J.; Yu, Y.; Lin, W.; Hu, A.; Wu, C. Application of AI in multilevel pain assessment using facial images: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2024, 26, e51250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otaka, E.; Osawa, A.; Kato, K.; Obayashi, Y.; Uehara, S.; Kamiya, M.; Mizuno, K.; Hashide, S.; Kondo, I. Positive emotional responses to socially assistive robots in people with dementia: Pilot study. JMIR Aging 2024, 7, e52443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wang, C.; Xiang, X.; An, R. AI applications to reduce loneliness among older adults: A systematic review of effectiveness and technologies. Healthcare 2025, 13, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourgeois, M.; Fried-Oken, M.; Rowland, C. AAC strategies and tools for persons with dementia. ASHA Lead. 2010, 15, 8–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthanat, S.; Begum, M.; Gu, T.; LaRoche, D.P.; Xu, D.; Zhang, N. Caregiver perspectives on a smart home-based socially assistive robot for individuals with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementia. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2020, 15, 789–798. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Arthanat, S.; Wilcox, J.; LaRoche, D. Smart home automation technology to support caring of individuals with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementia: An early intervention framework. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2024, 19, 779–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nithya, S.; Palanisamy, S.K.; Obaid, A.J.; Apinaya Prethi, K.; Alkhafaji, M.A. AI-Based Secure Software-Defined Controller to Assist Alzheimer’s Patients in Their Daily Routines. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Frontiers of Intelligent Computing: Theory and Applications, Cardiff, UK, 11–12 April 2023; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 453–463. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Y.J.; Felber, N.A.; Pageau, F.; Schwab, D.R.; Wangmo, T. Benefits and barriers associated with the use of smart home health technologies in the care of older persons: A systematic review. BMC Geriatr. 2024, 24, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, S.; Si, Y.; Guo, C.; Wang, P.; Li, S.; Wang, J.; Wang, X. The prediction model of fall risk for the elderly based on gait analysis. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puthusseryppady, V.; Morrissey, S.; Aung, M.H.; Coughlan, G.; Patel, M.; Hornberger, M. Using GPS tracking to investigate outdoor navigation patterns in patients with Alzheimer disease: Cross-sectional study. JMIR Aging 2022, 5, e28222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkumar, J.; Karthikeyan, C.; Vamsidhar, E.; Dattatraya, K.N. Automated pill dispenser application based on IoT for patient medication. In IoT and ICT for Healthcare Applications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 231–253. [Google Scholar]

- Gargioni, L.; Fogli, D.; Baroni, P. A systematic review on pill and medication dispensers from a human-centered perspective. J. Healthc. Inform. Res. 2024, 8, 244–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menghi, R.; Gullà, F.; Germani, M. Assessment of a Smart Kitchen to Help People with Alzheimer’s Disease. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Smart Homes and Health Telematics, Singapore, 10–12 July 2018; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 304–309. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Soh, Y. A cooking assistance system for patients with Alzheimers disease using reinforcement learning. Int. J. Inf. Technol. 2017, 23, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Naami, B.; Abu Owida, H.; Abu Mallouh, M.; Al-Naimat, F.; Agha, M.D.; Al-Hinnawi, A.-R. A new prototype of smart wearable monitoring system solution for alzheimer’s patients. Med. Devices Evid. Res. 2021, 14, 423–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedi, A.; Chu, C.H.; Khan, S.S. Early Prediction of Agitation in Community-Dwelling People with Dementia Using Multimodal Sensors and Machine Learning: Benchmarking of State-of-the-Art Techniques. In Proceedings of the International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Montreal, QC, Canada, 16–22 August 2025; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Borna, S.; Maniaci, M.J.; Haider, C.R.; Gomez-Cabello, C.A.; Pressman, S.M.; Haider, S.A.; Demaerschalk, B.M.; Cowart, J.B.; Forte, A.J. Artificial intelligence support for informal patient caregivers: A systematic review. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milella, F.; Russo, D.; Bandini, S. AI-powered solutions to support informal caregivers in their decision-making: A systematic review of the literature. OBM Geriatr. 2023, 7, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, B.; Tao, C.; Li, J.; Hilsabeck, R.C.; Aguirre, A. Artificial intelligence for caregivers of persons with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias: Systematic literature review. JMIR Med. Inform. 2020, 8, e18189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stavropoulos, T.G.; Lazarou, I.; Diaz, A.; Gove, D.; Georges, J.; Manyakov, N.V.; Pich, E.M.; Hinds, C.; Tsolaki, M.; Nikolopoulos, S. Wearable devices for assessing function in Alzheimer’s disease: A European public involvement activity about the features and preferences of patients and caregivers. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2021, 13, 643135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deb, S.; Claudio, D. Alarm fatigue and its influence on staff performance. IIE Trans. Healthc. Syst. Eng. 2015, 5, 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggiano, N.; Brown, E.L.; Clarke, P.J.; Hristidis, V.; Roberts, L.; Framil Suarez, C.V.; Allala, S.C.; Hurley, S.; Kopcsik, C.; Daquin, J. An Evidence-Based IT Program With Chatbot to Support Caregiving and Clinical Care for People with Dementia: The CareHeroes Development and Usability Pilot. JMIR Aging 2024, 7, e57308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Z.; Zhong, J.; Sadarangani, T.R. A mixed-methods examination of the acceptability of, CareMOBI, a dementia-focused mhealth app, among primary care providers. Digit. Health 2024, 10, 20552076241287361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Z.; Sadarangani, T. Likelihood of Adoption of Caremobi: Addressing Communication Gaps Between Adult Day Health Centers and Primary Care. Innov. Aging 2022, 6, 841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudi, E.; Wu, W.; Najarian, C.; Aikens, J.; Bynum, J.; Vydiswaran, V.V. Identifying caregiver availability using medical notes with rule-based natural language processing: Retrospective cohort study. JMIR Aging 2022, 5, e40241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. iSupport. 2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/mental-health-and-substance-use/treatment-care/isupport (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Bennett, B.; McDonald, F.; Beattie, E.; Carney, T.; Freckelton, I.; White, B.; Willmott, L. Assistive technologies for people with dementia: Ethical considerations. Bull. World Health Organ. 2017, 95, 749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaiumy Anaraky, R.; Lowens, B.; Li, Y.; Byrne, K.A.; Risius, M.; Wisniewski, P.; Soleimani, M.; Soltani, M.; Knijnenburg, B. Older and younger adults are influenced differently by dark pattern designs. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.03830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aly, H.; Liu, Y.; Khan, S.; Anaraky, R.G.; Byrne, K.; Knijnenburg, B. Digital privacy education: Customized interventions for US older and younger adults in rural and urban settings. Technol. Soc. 2025, 81, 102805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aly, H.; Liu, Y.; Anaraky, R.G.; Khan, S.; Namara, M.; Byrne, K.A.; Knijnenburg, B. Tailoring digital privacy education interventions for older adults: A comparative study on modality preferences and effectiveness. Proc. Priv. Enhancing Technol. 2024, 2024, 635–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhr, E.; Welsch, J.; Shaukat, M.S. Value preference profiles and ethical compliance quantification: A new approach for ethics by design in technology-assisted dementia care. AI Soc. 2025, 40, 1209–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AboJabel, H.; Welsch, J.; Schicktanz, S. Cross-cultural perspectives on intelligent assistive technology in dementia care: Comparing Israeli and German experts’ attitudes. BMC Med. Ethics 2024, 25, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Ghaiumy Anaraky, R.; Knijnenburg, B. How not to measure social network privacy: A cross-country investigation. Proc. ACM Hum. Comput. Interact. 2021, 5, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaiumy Anaraky, R.; Li, Y.; Knijnenburg, B. Difficulties of measuring culture in privacy studies. Proc. ACM Hum. Comput. Interact. 2021, 5, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kropczynski, J.; Ghaiumy Anaraky, R.; Akter, M.; Godfrey, A.J.; Lipford, H.; Wisniewski, P.J. Examining collaborative support for privacy and security in the broader context of tech caregiving. Proc. ACM Hum. Comput. Interact. 2021, 5, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, C.; Linn, K.A.; Hubbard, R.A. Algorithmic fairness of machine learning models for Alzheimer disease progression. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2342203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deiana, A. A Pre-Processing Framework for Mitigating Representation Bias in Machine Learning Classification Algorithms. Doctoral Dissertation, Politecnico di Torino, Torino, Italy, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, T.; Pan, W.; Yu, J.; Ji, G.; Meng, X.; Wang, Y.; Li, M. Mitigating bias in AI mortality predictions for minority populations: A transfer learning approach. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2025, 25, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazer, L.H.; Zatarah, R.; Waldrip, S.; Ke, J.X.C.; Moukheiber, M.; Khanna, A.K.; Hicklen, R.S.; Moukheiber, L.; Moukheiber, D.; Ma, H. Bias in artificial intelligence algorithms and recommendations for mitigation. PLoS Digit. Health 2023, 2, e0000278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ali Skaiky, A.; Ali, H.M.S.; Mohammed, A.; Mahdi, Z.A. Comprehensive Bias Mitigation in AI: Evaluating Pre-Processing, In-Processing, and Post-Processing Techniques for Fair Decision-Making. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE 4th International Conference on Computing and Machine Intelligence (ICMI), Mount Pleasant, MI, USA, 5–6 April 2025; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Mackin, S.; Major, V.J.; Chunara, R.; Newton-Dame, R. Post-processing methods for mitigating algorithmic bias in healthcare classification models: An extended umbrella review. BMC Digit. Health 2025, 3, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudiyanselage, U.B.; Jayprakash, B.; Lee, K.; Kwon, K.H. Disaggregated Health Data in LLMs: Evaluating Data Equity in the Context of Asian American Representation. In Proceedings of the AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society, Madrid, Spain, 20–22 October 2025; pp. 292–303. [Google Scholar]

- Markus, A.F.; Kors, J.A.; Rijnbeek, P.R. The role of explainability in creating trustworthy artificial intelligence for health care: A comprehensive survey of the terminology, design choices, and evaluation strategies. J. Biomed. Inform. 2021, 113, 103655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medani, M.; Elhessewi, G.M.S.; Alqahtani, M.; Asklany, S.A.; Alamro, S.; Albalawneh, D.a.; Alshammeri, M.; Assiri, M. Leveraging explainable artificial intelligence with ensemble of deep learning model for dementia prediction to enhance clinical decision support systems. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 16639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nap, H.H.; Stolwijk, N.E.; Ipakchian Askari, S.; Lukkien, D.R.; Hofstede, B.M.; Morresi, N.; Casaccia, S.; Amabili, G.; Bevilacqua, R.; Margaritini, A. The evaluation of a decision support system integrating assistive technology for people with dementia at home. Front. Dement. 2024, 3, 1400624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gazzarata, R.; Almeida, J.; Lindsköld, L.; Cangioli, G.; Gaeta, E.; Fico, G.; Chronaki, C.E. HL7 Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources (HL7 FHIR) in digital healthcare ecosystems for chronic disease management: Scoping review. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2024, 189, 105507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swarnamugi, M.; Chinnaiyan, R. Smart and reliable transportation system based on message queuing telemetry transport protocol. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Intelligent Computing and Control Systems (ICCS), Madurai, India, 15–17 May 2019; pp. 918–922. [Google Scholar]

- Mun, D.-H.; Le Dinh, M.; Kwon, Y.-W. An assessment of internet of things protocols for resource-constrained applications. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE 40th Annual Computer Software and Applications Conference (COMPSAC), Atlanta, GA, USA, 10–14 June 2016; pp. 555–560. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X.; Li, J. An AIoT-enabled autonomous dementia monitoring system. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2207.00804. [Google Scholar]

- D’Onofrio, G.; Fiorini, L.; Toccafondi, L.; Rovini, E.; Russo, S.; Ciccone, F.; Giuliani, F.; Sancarlo, D.; Cavallo, F. Pilots for healthy and active ageing (PHArA-ON) project: Definition of new technological solutions for older people in Italian pilot sites based on elicited user needs. Sensors 2021, 22, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaberi, C.; Dafoulas, G.E.; Βallis, A.; Raptis, O. ACTIVAGE project: European Multi Centric Large Scale Pilot on Smart Living Environments. Case Study of the GLOCAL evaluation framework in Central Greece. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. Ment. Health 2018, 1, 138–143. [Google Scholar]

- Gioulekas, F.; Pinaka, O.; Gounaris, K.; Tzikas, A.; Stamatiadis, E.; Loukatzikou, A.; Andreou, A.; Gonidis, F.; Karkaletsis, K.; Kratouni, M. Smart and Healthy Ageing Through People Engaging in Supportive Systems; European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, K.A.; Ghaiumy Anaraky, R. Strive to win or not to lose? Age-related differences in framing effects on effort-based decision-making. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2020, 75, 2095–2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, C.; Nißen, M.; Kowatsch, T.; Vinay, R. Impact of digital assistive technologies on the quality of life for people with dementia: A scoping review. BMJ Open 2024, 14, e080545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, M.J.; Kercher, V.M.; Jordan, E.J.; Savoy, A.; Hill, J.R.; Werner, N.; Owora, A.; Castelluccio, P.; Boustani, M.A.; Holden, R.J. Technology caregiver intervention for Alzheimer’s disease (I-CARE): Feasibility and preliminary efficacy of Brain CareNotes. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2023, 71, 3836–3847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albala, S.A.; Kasteng, F.; Eide, A.H.; Kattel, R. Scoping review of economic evaluations of assistive technology globally. Assist. Technol. 2021, 33, 50–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, J.E.; Cooper, J.; Scheibling, C.; Parikh, A. Economic evaluation of passive monitoring technology for seniors. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2020, 32, 1375–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, S.Y.; Sumner, J.; Wang, Y.; Wenjun Yip, A. A systematic review of the impacts of remote patient monitoring (RPM) interventions on safety, adherence, quality-of-life and cost-related outcomes. NPJ Digit. Med. 2024, 7, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naunton Morgan, B.; Windle, G.; Lamers, C.; Brotherhood, E.; Crutch, S. Adaptation of an eHealth Intervention: iSupport for carers of people with rare dementias. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 21, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, A. AI Enhances Dementia Detection in Hospitals, Monash University Study Shows. 2025. Available online: https://insideageing.com.au/ai-enhances-dementia-detection-in-hospitals-monash-university-study-shows/ (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Yuan, F.; Hasnaeen, N.; Zhang, R.; Bible, B.; Taylor, J.R.; Qi, H.; Yao, F.; Zhao, X. Integrating Reinforcement Learning and AI Agents for Adaptive Robotic Interaction and Assistance in Dementia Care. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2501.17206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.