Abstract

This study aims to characterise the B cell compartment in a cohort of Sicilian centenarians by analysing absolute CD3−CD19+ lymphocyte counts, in association with age, sex, cytomegalovirus (CMV) serostatus, related to immune ageing, and interleukin (IL)-6 levels, representative of inflamm-ageing. It also investigates age-related changes in the CD4+/CD19+ ratio as a marker of immune ageing, reflecting shifts in immune homeostasis. B cell counts were assessed by flow cytometry on 53 Sicilians aged 19–110 years: 20 Adults, 15 Older adults, 11 long-living individuals, and 7 oldest centenarians. A multiple negative binomial regression was applied to evaluate the effects of age, sex, CMV serostatus, and Il-6 levels on values of B cells. The results showed a non-significant trend toward age-related decline without sex-based differences. A significant reduction in B cell count was observed in individuals with high anti_CMV titres, while IL-6 levels showed a borderline inverse correlation. CD4+/CD19+ ratio values showed an age-related increase. Our findings suggest that the age-related decline in B cell numbers may be mostly related to CMV infection and IL-6 values, without sex contribution. The age-related increase in the CD4+/CD19+ ratio, most pronounced in oldest centenarians, may represent a compensatory adaptation promoting immune regulation and chronic inflammation control.

1. Introduction

The immune system of semi- and supercentenarians (hereafter referred to as the oldest centenarians) appears to exhibit distinctive features that may contribute to their ability to achieve extreme longevity in relatively good health [1,2,3,4]. Characterising the immunophenotype of these individuals can thus offer valuable insights into how they adapt to age-related immune alterations, including the influence of persistent infections such as cytomegalovirus (CMV), which is known to affect the distribution of T lymphocyte subsets [4,5,6,7,8].

In a previous study [4], we analysed both the percentages and absolute counts of various immune cell subsets, with particular attention to Tαβ cells and pro-inflammatory markers, in a Sicilian cohort of 28 women and 26 men aged 19 to 110 years. This cohort included 11 long-living individuals (LLIs; aged >90 and <105 years) and 8 oldest centenarians (aged 105–110 years). Flow cytometric analyses revealed considerable interindividual variability in immunosenescence markers, which appeared to be modulated by both age and CMV serostatus. In a subsequent study, we focused on the two main subsets of Tγδ cells, Vδ1 and Vδ2, assessing their relative frequencies and functional subpopulations using the Tαβ-associated markers CD27 and CD45RA. These analyses were conducted on the same cohort and blood samples used in the Tαβ study, again employing flow cytometry [9]. In a third investigation, we reported a marked age-related increase in CD3−CD56+CD16+ natural killer (NK) cells, with the highest levels observed in the semi- and supercentenarian groups, although with notable interindividual variation [10].

Taken together, our findings on Tαβ, Tγδ, and NK cells support the view that immune ageing should not be considered a uniform decline, but rather a process of differential adaptation. As discussed across these three studies, the observed increases in CD8+ TEMRA cells (CD3+CD45RA+CCR7−), Vδ1 T cells, and CD3−CD16+CD56+ NK cells may reflect adaptive immune strategies that enable centenarians, particularly the oldest among them, to cope with lifelong antigenic exposure while maintaining immune competence into extreme old age [4,9,10].

B cells also play an important role in immune ageing [11,12,13], and the number of circulating B cells decreases with age, particularly in centenarians [1,14,15,16]. Hashimoto et al. [1], in particular, reported a marked decline in B-cell counts even among the oldest centenarians. However, findings regarding the influence of sex on B-cell levels remain inconsistent [17,18].

To further explore the immunophenotypic characteristics of lymphocytes in the oldest centenarians, the present study analysed the absolute number of B lymphocytes in the aforementioned Sicilian cohort [4], according to age and sex. Furthermore, given the known effects of both CMV seropositivity [19] and interleukin (IL)-6 [20,21] on lymphoid subsets, including B cells, these two variables were included as covariates in regression models. Finally, we evaluated age-related changes in the CD4+/CD19+ ratio as a potential marker of immune ageing, reflecting shifts in immune homeostasis.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

In the present study, we analysed data from 53 individuals of Sicilian origin, aged 19 to 110 years, enrolled between 2020 and 2022. Compared to the 54 subjects examined in the first study [4], B-cell values for 1 female semi-supercentenarian were missing. Participants had been selected based on the absence of significant health issues, including the LLIs and the oldest centenarians, who were all in relatively good health. The study design and recruitment procedures have been previously described [4]. For the validation of the age of semi- and supercentenarians, see Accardi et al. [22]. The cohort contained 20 Adults (10 males, 10 females; age range: 19.5–63.6 years), 15 Older adults (8 males, 7 females; age range: 68.5–87.3 years), 11 LLIs (7 males, 4 females; age range: 93.3–104.7 years), and 7 Oldest centenarians (1 male, 6 females; age range: 105.7–110.3 years). All LLIs and the oldest centenarians were CMV-seropositive, while CMV seropositivity was observed in 78% of older adults and 63% of younger adults [4].

2.2. Blood Sampling and Sample Processing

The participants underwent venipuncture in the morning after a 12 h fasting period. Blood samples from nonagenarians and centenarians were collected at their homes and transported to the university hospital in certified, compliant containers, whereas samples from the remaining participants were collected directly at the university hospital. Blood was drawn into tubes containing ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) or into additive-free tubes. Serum was obtained by centrifugation of dry tubes and stored at −80 °C until use, whereas leukocyte counts and flow cytometry analyses were performed on fresh whole-blood samples.

2.3. CMV Assay

Serum anti-CMV IgG levels were measured by chemiluminescence immunoassay using the LIAISON® CMV IgG II kit (DiaSorin, Turin, Italy), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The cut-off for CMV seropositivity was 14 U/mL, while the validated upper analytical limit was set at 180 U/mL. This threshold reflects technical validation, clinical applicability, and international regulatory standards, ensuring reliability and comparability of results. Accordingly, the values were divided into two groups: CMV ≥ 180 and CMV < 180. The latter group also included CMV-negative subjects.

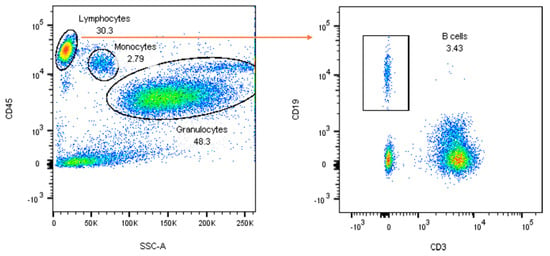

2.4. Flow Cytometry Analysis

It was performed on fresh whole blood following red blood cell lysis. The antibodies from BD Biosciences used are reported in Appendix A Table A1. Data were acquired using a FACS Canto cytometer (BD Biosciences, Milan, Italy) at the Central Laboratory of Advanced Diagnostics and Biomedical Research, “P. Giaccone” University Hospital, Palermo. Lymphocytes, monocytes, and granulocytes were initially identified based on forward scatter (FSC) and side scatter (SSC) parameters, followed by further characterisation using an SSC/CD45 dot plot. The gating strategy is illustrated in Appendix A Figure A1. Lymphocytes were gated as CD45+ with low SSC-A, and B cells were subsequently identified as CD3−CD19+ within this population. Results were first calculated as a percentage of the parent lymphocyte population and are expressed as absolute counts derived from total lymphocyte numbers. Automated differential leukocyte counts, IL-6 values, and CD4+ values were those previously assessed and reported in Ligotti et al. [4].

2.5. Statistical Analysis

To investigate how the number of B cells varies with respect to other variables, specifically age, sex, CMV serostatus, and IL-6 levels, we fitted a multiple negative binomial regression model. This type of analysis extends the principles of simple regression by allowing the simultaneous evaluation of the effects of multiple independent variables on a count-based dependent variable. This approach enables the assessment of the individual contribution of each factor while accounting for the influence of the others. In this context, the regression coefficients represent the estimated change in the logarithm of the expected B cell count associated with a one-unit increase in each independent numerical variable. Statistical significance was set at a p-value < 0.05. Model fit was evaluated using the poisgof function in R, which assesses goodness-of-fit for count data models. The CD4+/CD19+ ratio was studied using a generalised linear model with a Gamma distribution and a log-link function to appropriately account for the positive, right-skewed nature of the data. Non-parametric tests (i.e., bootstrap t-test and Spearman correlation) were applied to evaluate associations among explanatory variables. Graphical representations were generated using the ggplot2 R package (version 9.3.1). All statistical analyses were performed using R software (version 4.5.0).

3. Results

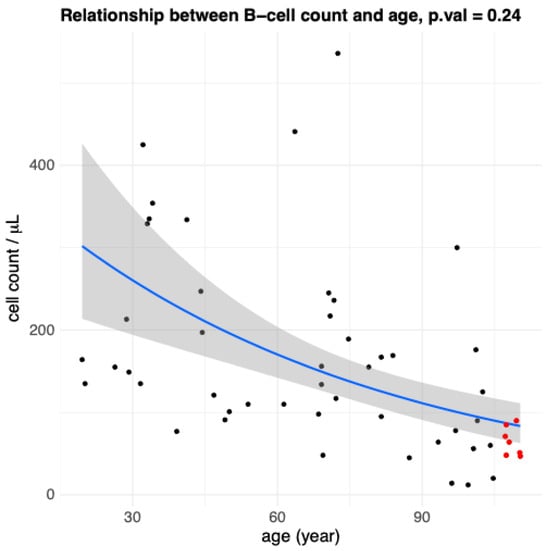

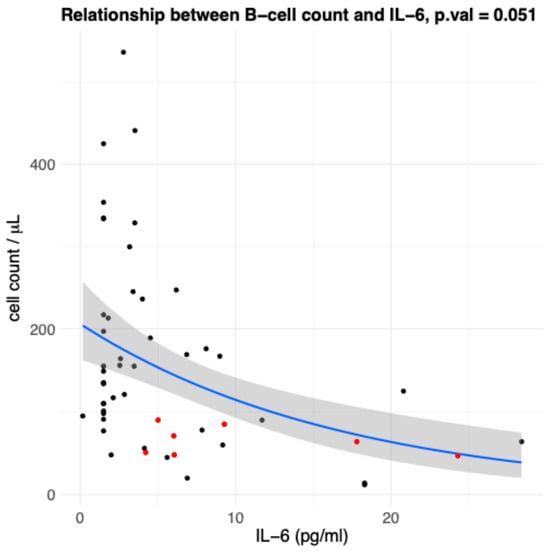

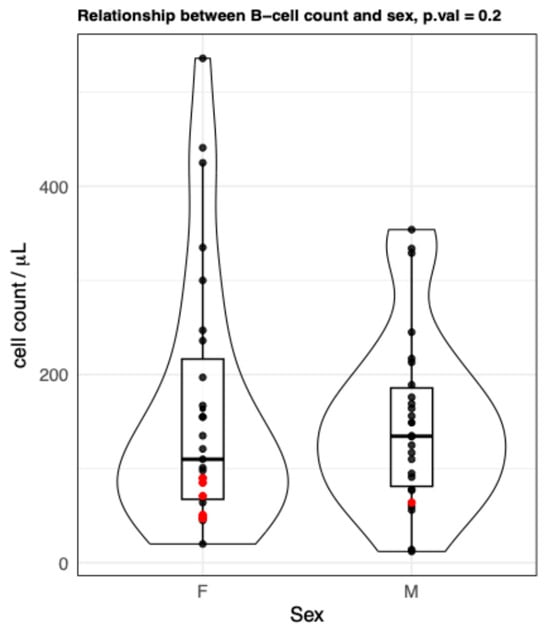

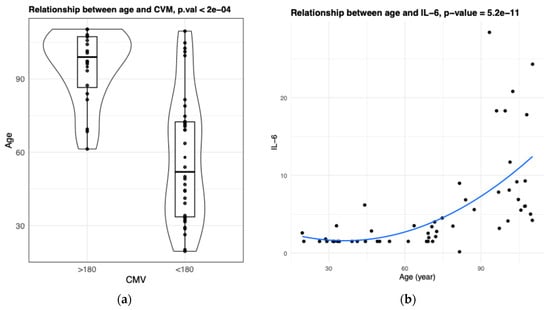

We evaluated the relation between the absolute number of B cells, identified by flow cytometry as CD3−CD19+, in the peripheral blood of all study participants, and age. Considering the results from the multivariable regression model (Table 1), although there was a trend towards an age-related decline in B cell counts, it did not reach statistical significance (Figure 1). Similarly, after adjustment for covariates in the same model, sex was not associated with significant differences in absolute B cell numbers (Appendix A Figure A2). The model revealed a robust and statistically significant effect of CMV serostatus since individuals with a CMV antibody titre equal to or greater than 1:180 had significantly lower B cell numbers compared to those who were either seronegative or had titres below this threshold (p-value = 0.0063). The low anti-CMV group exhibited the highest B-cell values (Figure 2). By contrast, we observed an inverse correlation between IL-6 levels and circulating B cells in the multivariable analysis (Figure 3). While this association approached significance, it remained at a borderline statistical threshold (p-value = 0.051). Finally, Table 2 presents the median values of the CD4+/CD19+ ratio across different age groups. The data clearly show that the CD4+/CD19+ ratio increases with age. To further examine the relationship between the CD4+/CD19+ ratio and age, we applied a multivariate regression model that included the other explanatory variables (Table 3). The results confirmed a strong association between the CD4+/CD19+ ratio and age, with higher ratios observed in the oldest centenarians (Table 2). Once again, IL-6 approached significance, but remained at a borderline statistical threshold (p-value = 0.053).

Table 1.

Regression coefficients, standard errors, and significance levels from the negative binomial model fitted with B cell count (CD3−CD19+) as the dependent variable.

Figure 1.

Age-related changes in B cell count (CD3−CD19+) values. Scatterplot representation showing the relationship between B cells and age in all participants (n = 53). Each point represents data from an individual healthy donor. Red points indicate the oldest centenarian (105+ years) values, black points indicate younger people. The solid blue line represents the fitted trend from a negative binomial regression model, and the surrounding shaded band shows the model-based 95% confidence interval for the fitted mean. The p-value from the multiple regression (p = 0.24) indicates a non-significant association.

Figure 2.

B cell counts (CD3−CD19+) stratified by anti-CMV antibody titers. Violin plots show the distribution of circulating B cell counts in participants with anti-CMV titres ≥ 180 and <180. Each dot represents an individual healthy donor; red dots indicate the oldest centenarians (≥105 years), black points indicate younger people. The p-value derived from the multivariable regression analysis (p = 0.0063) indicates significantly higher B cell counts in the low anti-CMV group. The low anti-CMV group includes individuals with titres < 180, including CMV-seronegative subjects, whereas the high anti-CMV group includes individuals with titers ≥ 180.

Figure 3.

Association between IL-6 levels and circulating B-cell counts (CD3−CD19+). Scatterplot showing the inverse relationship between circulating B cells and IL-6 levels in all participants (n = 53). Each point represents an individual healthy donor; red points indicate the oldest centenarians (≥105 years), black points indicate younger people. The solid blue line represents the fitted trend from a negative binomial regression model, and the surrounding shaded band shows the model-based 95% confidence interval for the fitted mean. The p-value from the multivariable regression analysis (p = 0.051) approached statistical significance, suggesting a trend toward an association between B-cell counts and interleukin-6 (IL-6) levels.

Table 2.

Median values of the CD4+/CD19+ ratio across different age classes.

Table 3.

Regression coefficients, standard errors, and significance levels from the gamma regression model fitted with CD4+/CD19+ ratio as the dependent variable.

4. Discussion

A significant association between chronological age and peripheral B cell counts has been documented in nearly all studies employing univariate analyses [1,15,17]. However, in our multiple regression model that incorporates potential confounder variables (i.e., sex, CMV serostatus, and circulating IL-6 levels), the age effect is attenuated and no longer statistically significant (Table 1). This attenuation is likely due to multicollinearity among the predictors, which reflects the biological interconnectedness of ageing-related processes rather than a purely statistical artifact. In our sample, chronological age is inherently correlated with both CMV serostatus and systemic IL-6 elevation (Appendix A Figure A3a,b), confirming their contributions to immune ageing [8,22,23]. The univariate relationship between age and B cell count, which is generally observed, may reflect both direct and indirect effects, with the latter mediated by age-associated immunological alterations such as CMV infection and IL-6 blood levels. In the multivariable context, the model partitions share variance among the covariates, allowing for the isolation of each variable’s unique contribution to the outcome. As a result, the specific variance attributable to age alone is diminished, rendering its effect size non-significant (Table 1) [24]. However, it is important to consider that including multiple covariates, especially in studies with limited sample sizes, can lead to a reduction in statistical power due to the consumption of degrees of freedom [25].

Regarding the CMV contribution to immune ageing, CMV is the most extensively investigated virus in the context of ageing, as its lifelong persistence profoundly reshapes immune function and is considered a major driver of immunosenescence [8]. Lifelong CMV infection is the primary cause of peripheral expansion of T memory cells (the so-called memory inflation), but not for the age-related loss of naïve T cells, both considered hallmarks of immunosenescence [8,26]. In older individuals, chronic CMV infection can weaken vaccine responses, increase vulnerability to infections, and contribute to age-related conditions like cardiovascular diseases [8]. Research into CMV–ageing interactions aims to clarify the role of this infection in immune deterioration and its broader consequences for health and longevity in later life. To date, no other virus has been shown to impose such deep and multifaceted effects on the human immune system [5,6,7,8,26,27,28]. However, to the best of our knowledge, the current study is the first to examine the effects of CMV on B-cell levels in the oldest centenarians.

Concerning IL-6, it has long been recognised as a key cytokine in gerontology [29], as its age-related increase contributes to chronic low-grade inflammation (“inflamm-ageing”) and is associated with frailty, immune dysfunction, and age-related morbidity and mortality [30,31,32,33]. Therefore, given their known effects on immune ageing, both CMV and IL-6 were included as covariates in our analysis in order to obtain unbiased and properly adjusted effect estimates.

Regarding the mechanisms underlying the reduction in B cells in individuals with high anti-CMV titres (Figure 2), one can speculate based on current knowledge of the impact of CMV on the immune system in older adults. As noted above, chronic CMV infection drives the expansion and long-term persistence of CMV-specific T cells, a phenomenon termed memory inflation [4,8,9]. These enlarged T-cell populations can occupy substantial immunological space, potentially outcompeting other immune cells, including B cells, for niches and resources. This competition may compromise overall immune system balance and contribute to age-related immune dysfunction. In parallel, chronic infection fuels inflamm-ageing, which alters the bone marrow microenvironment through elevated pro-inflammatory mediators and impaired support for immune cell development, including that of B cells. Such age-related changes are associated with a decline in naïve B-cell output and an accumulation of terminally differentiated, functionally exhausted memory B cells, ultimately affecting their survival and functional capacity [34]. This latter explanation may also be consistent with the observed inverse association between IL-6 levels and circulating B-cell numbers (Figure 3), which approached statistical significance. This borderline result may reflect limited statistical power due to the small sample size, rather than the absence of a biological relationship, given the well-established role of IL-6 in inflamm-ageing [35].

Several studies have reported higher mean B cell counts in adult women compared to men [17,18], although this finding is not universally observed. Supporting this trend, Roszczyk et al. [18] documented higher mean and median percentages of B cells in older women than in men within their cohort, with B cells measured as a proportion of total lymphocytes. However, in our study, we did not observe any significant differences in B cell counts between males and females (Appendix A Figure A2). It is worth noting, however, that as shown in both Figure 1 and Appendix A Figure A2, the oldest centenarians (red dots) display the lowest levels of B lymphocytes, and 6 out of 7 of them are women, which confirms the general ratio among women to men centenarians [22]. This imbalance in sex distribution, particularly among oldest centenarians, reflecting a well-established demographic reality [22], may account for the lack of statistically significant differences observed between men and women.

The strong association between the CD4+/CD19+ ratio and age, with higher ratios observed in the oldest centenarians (Table 2), likely reflects the decline in B-cell numbers together with the relative preservation of CD4+ T cells, the so-called memory inflation. This imbalance might indicate adaptive remodelling of the immune system in extreme ageing, characterised by a shift toward a T cell-dominated profile. In the oldest centenarians, this immune configuration might represent a successful compensatory adaptation that favours immune regulation and control of chronic inflammation rather than maximal immune activation, as also demonstrated in previous papers about the characterisation of lymphocyte subpopulations in oldest centenarians [1,3,4,9,10,22].

Our study is not without limitations. First and foremost, the study follows a cross-sectional design, which poses inherent constraints. While such studies are valuable for estimating prevalence and highlighting potential associations among variables, they are inherently limited in establishing causal relationships or tracking longitudinal changes over time. Another important limitation concerns the relatively small number of the oldest participants enrolled, particularly centenarians and the oldest centenarians. However, it should be emphasised that these oldest centenarians represent an extremely rare segment of the population; the estimated ratio of supercentenarians to centenarians is approximately 1 in 1000 [22]. Additionally, our sample exhibited a marked sex imbalance, mirroring the known demographic distribution among Italian centenarians, where women outnumber men by approximately 85% to 15% [36]. According to data from the Supercentenarians of Italy website, as of October 2025, there were 23 living individuals aged over 110 years, only 1 of whom was male, and 171 semi-supercentenarians (aged over 107), among whom only 16 were men, yielding a striking female-to-male ratio > 10:1 [37]. This demographic reality necessitates caution when interpreting results from sex-stratified analyses. A further limitation of our study is the lack of B-cell subset analysis. This choice was intentional, as our primary goal was to provide an overall characterisation of total CD19+ B cells across an exceptionally broad age range. Future studies with larger cohorts and more detailed immunophenotyping will be needed to clarify age-related changes within specific B cell subpopulations (see below).

To address several of these limitations, future efforts should aim to include additional national research centres interested in the biology of semi- and supercentenarians. Expanding the recruitment base would increase the overall sample size, particularly for male participants, and would also enable a more comprehensive evaluation of B-cell subtypes implicated in immune ageing. Indeed, future studies with larger cohorts and longitudinal designs, and, where feasible, with more sex-balanced samples, will be necessary to clarify the strength, consistency, and potential biological relevance of this association.

5. Conclusions

Our findings indicate that the age-related decline in circulating B-cells is not primarily driven by chronological age per se but is largely associated with CMV seropositivity and systemic inflammation, as reflected by IL-6 levels. When these variables were included as covariates in the multivariable model, age was no longer an independent predictor of B cell counts, suggesting that previously reported age effects may largely reflect indirect, age-associated processes.

In this context, neither sex-based differences in B cell counts nor a shift toward B cell predominance were observed in the oldest centenarians. Together, these results highlight the importance of considering chronic CMV infection and inflamm-ageing when interpreting immune ageing trajectories, particularly in extremely long-lived individuals.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization G.B., G.C., C.C. and A.C.; methodology G.B., A.M.C., C.C., M.D.S. and S.M.; formal analysis A.C., S.M. and G.B.; investigation, G.A., A.M.C., M.D.S., C.C. and A.A.; data curation G.A., A.C. and G.B.; writing—original draft preparation, G.A., A.C., C.C. and A.A.; writing—review and editing, G.A., A.C. and A.A.; supervision S.M., C.C. and G.C.; funding acquisition, C.C. and G.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of “Paolo Giaccone”, University Hospital, which approved the study protocol (Nutrition and Longevity, No. 032017, 1 March 2017).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank Alessandro Delucchi, a representative of the European Supercentenarian Organisation and of Longevity Quest, data provider to the Buck Institute for Research on Aging, for the identification of the semi- and supercentenarians by http://www.supercentenariditalia.it.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CMV | Cytomegalovirus |

| FSC | forward scatter |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| LLIs | long-living individuals |

| NK | Natural Killer |

| SSC | side scatter |

Appendix A

Table A1.

List of antibodies used in the study.

Table A1.

List of antibodies used in the study.

| Target Cells | Antibodies |

|---|---|

| Leukocytes | CD45 PerCP-Cy™5.5, clone 2D1 (HLe-1) |

| T lymphocytes | CD3 FITC, clone SK7 |

| B Lymphocytes | CD19 APC, clone SJ25C1 |

Figure A1.

Gating strategy for the identification of B lymphocytes (CD3−CD19+). For the explanation, see the main text.

Figure A2.

B cells (CD3−CD19+) values stratified by sex groups. Violin plots showing no differences between the B cell count from female and male groups. Each point represents data from an individual healthy donor. Red points indicate the values of the oldest centenarians. p-value (from the multiple regression) = 0.2. F = females; M = males.

Figure A3.

Association between explanatory variables. Both CVM (a) and IL-6 (b) values are significantly associated with age (bootstrap t-test p-value < 0.05, Spearman correlation p-value < 0.05).

References

- Hashimoto, K.; Kouno, T.; Ikawa, T.; Hayatsu, N.; Miyajima, Y.; Yabukami, H.; Terooatea, T.; Sasaki, T.; Suzuki, T.; Valentine, M.; et al. Single-cell transcriptomics reveals expansion of cytotoxic CD4 T cells in supercentenarians. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 24242–24251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Pujol, E.; Noguera-Castells, A.; Casado-Pelaez, M.; García-Prieto, C.A.; Vasallo, C.; Campillo-Marcos, I.; Quero-Dotor, C.; Crespo-García, E.; Bueno-Costa, A.; Setién, F.; et al. The multiomics blueprint of the individual with the most extreme lifespan. Cell Rep. Med. 2025, 6, 102368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagiannis, T.T.; Dowrey, T.W.; Villacorta-Martin, C.; Montano, M.; Reed, E.; Belkina, A.C.; Andersen, S.L.; Perls, T.T.; Monti, S.; Murphy, G.J.; et al. Multi-modal profiling of peripheral blood cells across the human lifespan reveals distinct immune cell signatures of aging and longevity. eBioMedicine 2023, 90, 104514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ligotti, M.E.; Accardi, G.; Aiello, A.; Aprile, S.; Calabrò, A.; Caldarella, R.; Caruso, C.; Ciaccio, M.; Corsale, A.M.; Dieli, F.; et al. Sicilian semi- and supercentenarians: Identification of age-related T-cell immunophenotype to define longevity trait. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2023, 214, 61–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Looney, R.; Falsey, A.; Campbell, D.; Torres, A.; Kolassa, J.; Brower, C.; McCann, R.; Menegus, M.; McCormick, K.; Frampton, M.; et al. Role of Cytomegalovirus in the T Cell Changes Seen in Elderly Individuals. Clin. Immunol. 1999, 90, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vescovini, R.; Telera, A.R.; Pedrazzoni, M.; Abbate, B.; Rossetti, P.; Verzicco, I.; Arcangeletti, M.C.; Medici, M.C.; Calderaro, A.; Volpi, R.; et al. Impact of Persistent Cytomegalovirus Infection on Dynamic Changes in Human Immune System Profile. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0151965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hassouneh, F.; Goldeck, D.; Pera, A.; van Heemst, D.; Slagboom, P.E.; Pawelec, G.; Solana, R. Functional Changes of T-Cell Subsets with Age and CMV Infection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Caruso, C.; Ligotti, M.E.; Accardi, G.; Aiello, A.; Candore, G. An immunologist’s guide to immunosenescence and its treatment. Expert Rev. Clin. Immunol. 2022, 18, 961–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ligotti, M.E.; Accardi, G.; Aiello, A.; Calabrò, A.; Caruso, C.; Corsale, A.M.; Dieli, F.; Di Simone, M.; Meraviglia, S.; Candore, G. Sicilian semi- and supercentenarians: Age-related Tγδ cell immunophenotype contributes to longevity trait definition. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2024, 216, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ligotti, M.E.; Accardi, G.; Aiello, A.; Calabrò, A.; Caruso, C.; Corsale, A.M.; Dieli, F.; Di Simone, M.; Meraviglia, S.; Candore, G. Sicilian semi- and supercentenarians: Age-related NK cell immunophenotype and longevity trait definition. Transl. Med. UniSa 2023, 25, 2–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, S.; Wang, C.; Mao, X.; Hao, Y. B Cell Dysfunction Associated With Aging and Autoimmune Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frasca, D. Senescent B cells in aging and age-related diseases: Their role in the regulation of antibody responses. Exp. Gerontol. 2018, 107, 55–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frasca, D.; Blomberg, B.B. Aging Affects Human B Cell Responses. J. Clin. Immunol. 2011, 31, 430–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Mol, J.; Kuiper, J.; Tsiantoulas, D.; Foks, A.C. The Dynamics of B Cell Aging in Health and Disease. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 733566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchini, E.; Pecorini, S.; De Biasi, S.; Gibellini, L.; Nasi, M.; Cossarizza, A.; Pinti, M. Lymphocyte Subtypes and Functions in Centenarians as Models for Successful Aging. In Handbook of Immunosenescence; Fulop, T., Franceschi, C., Hirokawa, K., Pawelec, G., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Y.; Kim, J.; Metter, E.J.; Nguyen, H.; Truong, T.; Lustig, A.; Ferrucci, L.; Weng, N.-P. Changes in blood lymphocyte numbers with age in vivo and their association with the levels of cytokines/cytokine receptors. Immun. Ageing 2016, 13, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Al-Attar, A.; Presnell, S.R.; Peterson, C.A.; Thomas, D.T.; Lutz, C.T. The effect of sex on immune cells in healthy aging: Elderly women have more robust natural killer lymphocytes than do elderly men. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2016, 156, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roszczyk, A.; Zych, M.; Sołdacki, D.; Zagozdzon, R.; Kniotek, M.J. Reference values of lymphocyte subsets from healthy Polish adults. Central Eur. J. Immunol. 2024, 49, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chidrawar, S.; Khan, N.; Wei, W.; McLarnon, A.; Smith, N.; Nayak, L.; Moss, P. Cytomegalovirus-seropositivity has a profound influence on the magnitude of major lymphoid subsets within healthy individuals. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2009, 155, 423–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aliyu, M.; Zohora, F.T.; Anka, A.U.; Ali, K.; Maleknia, S.; Saffarioun, M.; Azizi, G. Interleukin-6 cytokine: An overview of the immune regulation, immune dysregulation, and therapeutic approach. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2022, 111, 109130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazquez, M.I.; Catalan-Dibene, J.; Zlotnik, A. B cells responses and cytokine production are regulated by their immune microenvironment. Cytokine 2015, 74, 318–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Accardi, G.; Calabrò, A.; Caldarella, R.; Caruso, C.; Ciaccio, M.; Di Simone, M.; Ligotti, M.E.; Meraviglia, S.; Zarcone, R.; Candore, G.; et al. Immune-Inflammatory Response in Lifespan—What Role Does It Play in Extreme Longevity? A Sicilian Semi- and Supercentenarians Study. Biology 2024, 13, 1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frasca, D.; Blomberg, B.B. Aging, cytomegalovirus (CMV) and influenza vaccine responses. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2016, 12, 682–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Using Multivariate Statistics, 6th ed.; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Tu, W.; Rao, S. Mechanisms Underlying T Cell Immunosenescence: Aging and Cytomegalovirus Infection. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 2111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikolich-Žugich, J.; Čicin-Šain, L.; Collins-McMillen, D.; Jackson, S.; Oxenius, A.; Sinclair, J.; Snyder, C.; Wills, M.; Lemmermann, N. Advances in cytomegalovirus (CMV) biology and its relationship to health, diseases, and aging. GeroScience 2020, 42, 495–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, L.; Di Benedetto, S. Immunosenescence and Cytomegalovirus: Exploring Their Connection in the Context of Aging, Health, and Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ershler, W.B. Interleukin-6: A cytokine for gerontologists. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1993, 41, 176–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, T.; Newman, A.B. Inflammatory markers in population studies of aging. Ageing Res. Rev. 2011, 10, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Puzianowska-Kuźnicka, M.; Owczarz, M.; Wieczorowska-Tobis, K.; Nadrowski, P.; Chudek, J.; Slusarczyk, P.; Skalska, A.; Jonas, M.; Franek, E.; Mossakowska, M. Interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein, successful aging, and mortality: The PolSenior study. Immun. Ageing 2016, 13, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tyrrell, D.J.; Goldstein, D.R. Ageing and atherosclerosis: Vascular intrinsic and extrinsic factors and potential role of IL-6. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2021, 18, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Abraham, S.; Parekh, J.; Lee, S.; Afrin, H.; Rozenblit, M.; Blenman, K.R.M.; Perry, R.J.; Ferrucci, L.M.; Liu, J.; Irwin, M.L.; et al. Accelerated Aging in Cancer and Cancer Treatment: Current Status of Biomarkers. Cancer Med. 2025, 14, e70929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Frasca, D.; Diaz, A.; Romero, M.; Garcia, D.; Blomberg, B.B. B Cell Immunosenescence. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 36, 551–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tylutka, A.; Walas, Ł.; Zembron-Lacny, A. Level of IL-6, TNF, and IL-1β and age-related diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1330386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- ISTAT. Available online: https://www.istat.it/it/files//2022/06/STAT-TODAY_CENTENARI-2021.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Supercentenari d’Italia. Available online: https://www.supercentenariditalia.it/persone-viventi-piu-longeve-in-italia (accessed on 10 October 2025). (In Italian)

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.