Abstract

This study examines how the notion of value is defined, recognised, and operationalised within the four main approaches to cultural heritage preservation: the material-based, value-based, living heritage, and historic urban landscape approaches. Positioned within the broader discourse on the evolving understanding of cultural heritage—from fixed, expert-driven interpretations toward more contextual, socially constructed, and participatory perspectives—this research aims to address which value types are recognised, and how and to what extent they are operationalised by applying four main approaches to cultural heritage preservation. The methodology comprises four phases: (1) the identification, search, and selection of academic articles in the Scopus database, (2) sample overlapping and elimination of duplicates to establish a final dataset, (3) bibliometric analysis to determine publishing trends and disciplinary reach, and (4) content analysis to identify, classify, and compare value types across the selected approaches. The results reveal significant variation in how values are represented, as well as notable inconsistency in their direct inclusion in research processes. While cultural, historical, aesthetic, social, and economic values dominate across approaches, only a fraction of studies operationalise values through defined criteria or indicators. The findings highlight the absence of consensus in value interpretation and emphasise the need for more systematic, integrative, and operationalisable frameworks for treating values in the process of cultural heritage preservation.

1. Introduction

1.1. Renewing the Discourse on Cultural Heritage’s Values

Researching the notion of value within the academic domain represents a continuation of the analysis initiated through the identification, systematisation, and review of relevant data sources verified and/or published by renowned international organisations engaged in global cultural heritage preservation [1]. Among them, the leading organisations include UNESCO [2], ICOMOS [3], ICCROM [4], the Council of Europe [5], and the Architects’ Council of Europe [6], while the various types of documents they have verified and/or published represent an attempt at a global reconciliation of ideas, principles, approaches, and guidelines for practical action on cultural heritage. Although the need for a global concession of practices concerning cultural heritage preservation was initiated in 1931 [7] and established in 1964 [8], clearer steps towards the definition of cultural heritage were made in 1972 with the Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage [9]. It introduced the first division of heritage into natural (natural features, geological and physiographical formations, and natural sites) and cultural (monuments, groups of buildings, and sites) [9] (Articles 1, 2, p. 2). For this research problem and subject, of particular importance is the formulation “which are of outstanding universal value”, which constitutes an integral part of the definitions for both natural and cultural heritage [9] (Articles 1–2, p. 2). Although the issue of cultural heritage values, initiated by the work of Alois Riegl in the 19th century [10], has been continuously examined [1,11,12,13,14,15,16,17], it has become especially prominent through the formulation “outstanding universal value”. The importance of the notion of value was further confirmed in 1994 by the Nara Document on Authenticity, which emphasises that “conservation of cultural heritage in all its forms and historical periods is rooted in the values attributed to the heritage” [18] (Article 9, p. 2). Thanks to the Nara Document on Authenticity, the existence of values associated with a specific monument, group of buildings, or site becomes a prerequisite for its recognition as a part of cultural heritage, while the principle of authenticity—as our ability to understand the cultural heritage values in relation to the credibility and truthfulness of the source of information—has emerged as an “essential qualifying factor concerning values” [18] (Articles 9–10, p. 2). The issue of cultural heritage values becomes inseparable from the principle of authenticity, as further confirmed by the Declaration of San Antonio [19]. Its particular importance lies in understanding the principle of authenticity in relation to identity, history, materials, and social value, as well as the authenticity in dynamic and static sites, stewardship, and economics [19] (pp. 1–5), highlighting the complexity of the various factors that must be taken into account when researching cultural heritage and determining the credibility of its values.

Furthermore, within the Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention, the principle of authenticity is considered through material, workmanship, design, and setting [12] (pp. 66–74). The Guidelines place particular emphasis on “outstanding universal value” and its identification, which determines the cultural heritage to be recognised as of outstanding significance to humanity and inscribed on the World Heritage List [20], thereby receiving special treatment in terms of protection and preservation [12] (p. 13). In this context, the role of the World Heritage Committee is of significant importance in identifying the “outstanding universal value” of a particular monument, group of buildings, or site, and in the decision-making regarding its inscription on the World Heritage List. To ensure an optimal level of objectivity in decision-making, a set of criteria for determining “outstanding universal value” has been defined [12] (pp. 6–8), and subsequently supplemented in accordance with new knowledge and practical experience [21,22,23].

The further development of heritage studies has pointed to the risks of applying a fixed set of criteria for determining “outstanding universal value” as globally applicable, yet defined within a Western European value system [24] (p. 11). This implies the potential non-recognition and, consequently, the loss of heritage values that are context-specific, as further confirmed by the Charter—Principles for the analysis, conservation and structural restoration of architectural heritage which states that the “value and authenticity of architectural heritage cannot be based on fixed criteria because the respect due to all cultures also requires that its physical heritage be considered within the cultural context to which it belongs” [25] (p. 1). This brings the “universality” of the notion of value into question, particularly in regard to its contextual dependency, as well as the perceptions of different groups (local communities and stakeholders) concerning cultural heritage and its values. Numerous documents verified and/or published by internationally recognised organisations aim to link cultural heritage and its values, both tangible and intangible, with the surrounding environment and the people with whom it is interrelated [26,27,28,29,30,31]. The term “heritage community” is defined as “people who value specific aspects of cultural heritage which they wish, within the framework of public action, to sustain and transmit to future generations” [27] (Article 2b, p. 2).

Moreover, cultural heritage has increasingly been viewed within the context of humanistic values, with its preservation aimed at protecting the spirit of place and the identity of people, as well as at improving quality of life [31]. There has been a growing emphasis on the need for more direct involvement of local communities and stakeholders in heritage preservation processes. This is particularly evident in the Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape, which highlights the importance of reaching the “consensus using participatory planning and stakeholder consultations on what values to protect for transmission to future generations, and to determine the attributes that bear these values” [30] (Article 3b, p. 1).

Furthermore, the Burra Charter [32] addresses the management of places with cultural heritage elements, calling for the direct involvement of local communities and stakeholders throughout the entire process. A model for managing heritage places is developed, comprising seven steps grouped into three main stages: (1) understand significance—(a) understand the place, and (b) assess cultural significance; (2) develop policy—(c) identify all factors and issues, (d) develop policy, and (e) prepare a management plan; and (3) manage in accordance with policy—(f) implement the management plan, and (g) monitor the results and review the plan [32] (p. 10). Recent research develops models for managing world cultural heritage that “involves the principles and practices of identifying, preserving, documenting, interpreting, and presenting objects, sites, and phenomena of historical, natural, scientific, or other value” [33] (p. 183), aligning with the principles of sustainable development, inclusiveness, and the participation of all relevant actors [34,35,36].

For this research problem and subject, the step “assess cultural significance” is of particular relevance, as it is defined in the Burra Charter to include the identification and approach to all values of a place with cultural heritage elements using relevant criteria, along with the formulation of a “statement of significance” [32] (p. 10). “Significance” is highlighted as the synthesis of cultural heritage values, while the “statement of significance” represents a formal document confirming the value of a specific monument, group of buildings, or site as a representative of cultural heritage and determines which protective measures, including legal frameworks, are appropriate [37] (p. 35). Given that the identification of values is a prerequisite for determining the significance of a particular monument, group of buildings, or site—based on which it is formally treated as cultural heritage—the importance of studying the notion of value is renewed. Additionally, the preceding overview of thoughts on the notion of value demonstrates that it was initially considered through the context of “outstanding universal value”, within which it held an instrumental role, serving as a normative framework for assessing significance and proclaiming cultural heritage. Subsequently, with the introduction of humanistic values and the growing need for the participation of various groups in processes of value identification and cultural heritage preservation, the notion of value became contextualised and locally dependent. This observed shift in understanding the notion of value underscores its mutable nature and the need for its continuous study and (re)examination in terms of its meaning, scope, and potential for manifestation in cultural heritage preservation.

1.2. Identifying the Main Approaches to Cultural Heritage Preservation

To analyse the notion of value within the framework of cultural heritage preservation, the authors of this paper recognised the need to identify and examine the main approaches to cultural heritage preservation. It is the authors’ statement that determining and analysing the main approaches enables insight into the ways of treating the notion of value in cultural heritage preservation.

In this regard, the analysis of relevant data sources, verified and/or published by renowned international organisations, included highlighting the meaning and scope of the notion of value and the core ideas of heritage preservation. The published results are part of wider research on the notion of value. Four main approaches to cultural heritage preservation were identified: (1) the material-based approach (MBA), (2) the value-based approach (VBA), (3) the living heritage approach, and (4) the historic urban landscape approach (HUL) [1]. Their identification as the main approaches is supported by the research of Ioannis Poulios, who recognises two dominant approaches, (1) material-based and (2) value-based, while promoting the application of the (3) living heritage approach [38]. The identification of the (4) historic urban landscape approach as the fourth dominant is based on the Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape [30].

1.2.1. MBA: Material-Based Approach to Cultural Heritage Preservation

The material-based approach developed from the idea of cultural heritage as the material remnants of the past, promoted by experts engaged in conservation to preserve them for future generations [34]. It has been supported by numerous internationally recognised documents in cultural heritage preservation [1], particularly the Venice Charter, which, through its explanation of conservation and restoration procedures [8] (Articles 4–13), contributed to the practical application of this approach. Within this conventional, object-based approach, cultural heritage is regarded as immutable. The focus is placed on the preservation of building materials as the direct representatives of cultural heritage and as the bearers of its values [33,39]. The widespread application of this approach has enabled the survival of a considerable cultural heritage affected by wartime destruction, especially during the 19th and 20th centuries [38]. On the other hand, viewing the building materials as the primary bearer of cultural heritage value has contributed to the perspective that heritage should be isolated from the present and protected from contemporary use that could potentially have a negative impact on its material [38].

1.2.2. VBA: Value-Based Approach to Cultural Heritage Preservation

The value-based approach emerged from the need to overcome the limitations of the material-based approach, particularly in understanding the notion of value. Unlike the material-based approach, which is oriented towards heritage conservation experts and their interpretation of value, the application of the value-based approach seeks to involve diverse groups—including local communities and stakeholders—in the processes of cultural heritage preservation. The expansion of the value-based approach into practical application can be attributed to documents such as the Burra Charter, which emphasises that the assessment of a place’s significance is based on values assigned to it by all stakeholder groups, not only by experts [32] (Article 6), [34]. Also, the Nara Document on Authenticity highlights the importance of ensuring “that attributed values are respected and that their determination includes efforts to build, as far as possible, a multidisciplinary and community consensus concerning these values” [18] (Appendix 1.3, p. 3). The value-based approach is grounded in understanding the cultural heritage and its values as a social construct [40] and in the statement that cultural heritage values result from the interaction between the heritage itself, its context, and people [33]. Owing to the ideas embedded in the value-based approach, the scope of the notion of value has expanded to include both tangible and intangible values, which are starting to be understood as changeable, justifying the importance of their (re)examination.

Although a significant step has been made toward including various relevant actors in the processes of cultural heritage preservation, researchers note the still-dominant role of experts in decision-making [33,38]. Consequently, the value-based approach remains closer to the material-based. Despite efforts to overcome the limitations identified in the material-based approach, the value-based approach has not yet succeeded in achieving a balance between the preservation of tangible and intangible values. Although the presence of intangible values has been acknowledged, they are still not treated equally within the processes of cultural heritage preservation. The limitations of the value-based approach have also been observed from the standpoint of the difficulty in forming a consensus about which cultural heritage values—identified by various groups such as local communities, stakeholders, and experts—should be preserved. Some authors explain this issue through the subjectivity in value assessment, as well as the existence of conflicting values and interests among local communities, stakeholders, and experts [40,41].

1.2.3. LHA: Living Heritage Approach to Cultural Heritage Preservation

The living heritage approach emerged from the need to identify and more directly involve relevant actors—primarily local community members—in the processes of cultural heritage preservation. Particular focus is placed on their equal participation and decision-making capacity. To understand its main ideas, it is necessary to comprehend the term “living heritage”, which is explained as “the ongoing use of heritage by its associated community for the purpose for which it was originally created” [42] (p. 4). This approach is based on the concept of continuity (1) of the original function of the cultural heritage, (2) of the relationship between the community and the cultural heritage, (3) of the community’s care for the cultural heritage, and (4) of the development of both tangible and intangible aspects of the cultural heritage in response to changing conditions [38,41,43]. The concept of continuity in the living heritage approach becomes dominant over the principle of authenticity, thus transforming the idea of preserving cultural heritage as a material remnant of the past into the need to preserve it as a process [33], thereby opening possibilities for its broader practical application, especially in the context of world heritage management [44].

On the other hand, the early development of the living heritage approach—also referred to as the people-centred, community-based approach—was the result of the activities of ICCROM and the Programme on Living Heritage Sites, launched in 2003 as part of the Integrated Territorial and Urban Conservation (ITUC) initiative [43]. The Programme’s main idea was to connect cultural heritage with the contemporary context, “including benefits and people’s interests and capacity to engage in continuous care as true and long-term custodians of these sites” [43] (p. 43). The Programme’s objectives included “the creation of tools necessary to develop a community-based approach to conservation and management; promotion of traditional knowledge systems in conservation practices and increased attention paid to living heritage issues in training programmes” [43] (p. 43).

The central role of the community in the development and implementation of the living heritage approach is evident. At the same time, the significant contribution lies in defining the “core community” as members of the local community who are directly connected to the cultural heritage, maintain its original function, and nurture a responsible relationship toward it—making it an integral part of contemporary life, or in other words, making it “living” [38] (p. 21). Due to their direct and intergenerational continuity with the cultural heritage, core community members are identified as relevant actors in decision-making processes concerning heritage preservation [38] (p. 24). Other stakeholder groups, including the broader local community and experts, have a consultative and educational role toward the core community, which acts as the decision-maker [45]. This represents one of the main differences between the living heritage approach and the previously analysed ones.

The particular significance of the living heritage approach lies in its applicability to various types of heritage [43]. However, it is essential to acknowledge the potential drawbacks of its practical application. This approach emphasises the continuity of cultural heritage use, in contrast to the material-based approach, which aims to separate it from contemporary life. Unlike the value-based approach, which attempts to include both tangible and intangible values (albeit with the continued dominance of tangible ones), the living heritage approach focuses on nurturing intangible values of cultural heritage, while the preservation of tangible values is deprioritised [38,46]. Nonetheless, through the living heritage approach, the idea of adapting cultural heritage to contemporary needs is developed, whereby cultural heritage begins to be preserved for the present, and the ways it is adapted to contemporary demands begin to be interpreted as its new values.

1.2.4. HUL: Historic Urban Landscape Approach to Cultural Heritage Preservation

To understand the historic urban landscape approach, it is necessary to explain the term “historic urban landscape”. It was defined in 2011 in the Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape [30]—a document responsible for the formal articulation of the historic urban landscape approach and promoting its broader application in cultural heritage preservation and management. According to the definition, “historic urban landscape” refers to “the urban area understood as the result of a historic layering of cultural and natural values and attributes, extending beyond the notion of ‘historic centre’ or ‘ensemble’ to include the broader urban context and its geographical setting” [30] (I. Definition, item 8, p. 3). Although its promotion was renewed in 2011 [30], its conceptual development dates back to 2005, in the UNESCO initiative and the Vienna Memorandum, which aimed to bridge the gap between cultural heritage preservation and development [44,47]. The Memorandum’s significance lies in the need to maintain cultural continuity through quality interventions and the imperative to identify different historical layers, as reflected in the statement that “urban planning, contemporary architecture and preservation of the historic urban landscape should avoid all forms of pseudo-historical design, as they constitute a denial of both the historical and the contemporary alike” [47] (D. Guidelines for conservation management, item 21, p. 4).

This approach is based on understanding cultural heritage as a process—an idea initiated by the living heritage approach. Focused on urban conservation and the preservation of historic urban landscapes, this approach reinterprets cultural heritage values that extend beyond the scope of individual monuments or ensembles, “shifting the discourse from ‘monuments’ to ‘people’, from ‘objects’ to ‘functions’, from ‘preservation’ to ‘sustainable use and development’ and from ‘material evidence to the intangible (and even unconservable) intellectual construct of ancestral communal memory” [48] (p. 2) [49]. Furthermore, it fosters an understanding of cultural heritage values as evidence of the urban environment’s evolution [37,50], thereby connecting with the concept of continuity. As in the value-based and living heritage approaches, it adopts the idea of cultural heritage as a social and ideological construct [48,51], positioning people at the centre of cultural heritage preservation and management [30] (Introduction, item 6, p. 2). The relevance of this approach is further demonstrated by research efforts aimed at identifying the relevant groups that should be included in cultural heritage preservation and management practices, as well as the tools for their participation and the methods for the practical implementation of the historic urban landscape approach [52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59]. The potential for broader practical application of this approach is outlined in the Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape [30] and further explained in the HUL Guidebook: Managing Heritage in Dynamic and Constantly Changing Urban Environments [60]. This includes a set of six steps [30] (item 3) and four groups of tools [30] (IV. Tools, item 24) for practically implementing the historic urban landscape approach in cultural heritage preservation and management practices, thereby marking a significant step toward a more direct link between heritage theory and practice.

Through an understanding of cultural heritage as a process and the recognition of the need to maintain continuity, the historic urban landscape approach is seen as a carrier of the advanced ideas on cultural heritage that were initiated in the Burra Charter [32,61]. These ideas expanded the scope of cultural heritage and its values, as well as the range of stakeholders involved in its preservation and management practices. However, despite the identification of significant potential, the historic urban landscape approach is still not globally applied in heritage preservation and management practice, which is explained by the lack of operational methods and tools [61]—particularly in identifying the cultural heritage values and associated attributes which form an essential starting point for any research considering cultural heritage and its preservation and management.

1.3. Research Challenge: Unestablished Consensus on Cultural Heritage and Its Values

Previous identification and analysis of the four main approaches to cultural heritage preservation have enabled tracing the ideas concerning cultural heritage over time. At their cores lie values; thus, cultural heritage preservation becomes a process of negotiating values [62] deemed significant by relevant experts and various stakeholder groups. However, the subjectivity inherent in different actors’ assessments of the values’ importance and in selecting the “most significant” ones complicates the process of responsible cultural heritage preservation. This complexity is further exacerbated by the increasing number of internationally recognised documents, which, despite striving to establish a global consensus on cultural heritage and its preservation [63], paradoxically fail to provide more precise and directly applicable guidance for the identification and safeguarding of cultural heritage values. This issue is particularly evident in the context of World Cultural Heritage. It entails the formal exclusion of local communities from preservation and management processes [64], thereby omitting a valuable source of local knowledge that could contribute to the recognition and appropriate treatment of cultural heritage values.

The gap between theory, which aspires to establish global coherence in the treatment of cultural heritage, and practice, which is contextually dependent, is also reflected in the categorisation of approaches to cultural heritage preservation. On the one hand, there is the application of expert-led approaches [16,24,48,65], predominant in the context of World Cultural Heritage and often based on the application of universally defined principles and the consideration of cultural heritage values within one or more related academic disciplines. On the other hand, approaches grounded in the central local community’s role are developing [16,24,48,65]. Although recognised as more interdisciplinary and inclusive compared to expert-led approaches, these approaches also possess potential drawbacks, including the risk that certain groups may abuse their positions as decision-makers [66,67,68].

The decision to apply one of the four main approaches depends on the context and condition of the cultural heritage, the needs of the stakeholders involved in its preservation, and the intentions of the decision-makers. However, there is an increasing call for the simultaneous application of knowledge from all four main approaches. Furthermore, to establish a basis for achieving consensus on the interpretation of cultural heritage, particular attention should be devoted to operationalising and combining the different tools for approaching its values, which constitute an integral component of each of the four identified main approaches to cultural heritage preservation.

1.4. Research Outline

Building on the identified lack of consensus and operational clarity in the treatment of cultural heritage values, this study moves beyond definitional discussions to examine how values are recognised, operationalised, and prioritised within contemporary academic practice. Rather than asking what cultural heritage values are in abstract terms, the research focuses on how value types are mobilised within the four dominant approaches to cultural heritage preservation—material-based (MBA), value-based (VBA), living heritage (LHA), and historic urban landscape (HUL) —as reflected in the global academic literature. Although the four-approach framework is well established, the literature still lacks a systematic, evidence-based account of how these approaches are operationalised through value types in contemporary scholarship and how their practical implications are implicitly shaped by what is actually measured and prioritised. Building on calls to combine knowledge across approaches and to better operationalise tools for approaching values, this study advances the field by moving from a descriptive classification of types to a data-driven synthesis that maps (1) value type recognition versus (2) direct inclusion in research processes across the four approaches, and identifies patterns of dominance and under-representation.

Accordingly, the study addresses the following research questions:

- RQ1. Which value types are recognised within academic research applying the four main approaches to cultural heritage preservation, and how does their representation vary across approaches?

- RQ2. To what extent are recognised value types directly operationalised within research processes (e.g., through criteria, indicators, or evaluative frameworks), and where do discrepancies emerge between recognition and application?

- RQ3. What patterns of dominance, under-representation, or selectivity in value operationalisation can be identified across the four approaches, and what do these patterns imply for current heritage preservation practices?

These questions are directly aligned with the bibliometric and content-analysis design of the study and structure the presentation and discussion of results.

2. Materials and Methods

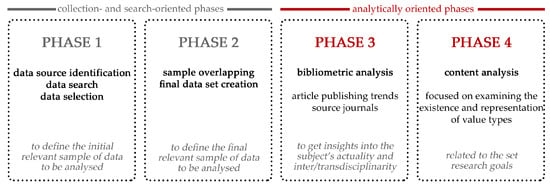

This research encompassed four main phases: (1) the identification of the data source, data search and data selection, (2) sample overlapping–final data set creation, (3) bibliometric analysis, and (4) content analysis (Figure 1). The first two phases focused on defining, collecting, and selecting relevant data sources, and establishing the final data sample. The third phase focused on analysing the research topic’s currency, and its potential for interdisciplinarity and transdisciplinarity. The fourth phase is directly linked to the research objectives.

Figure 1.

Research design (provided by authors, 2026).

By combining bibliometric mapping with structured content analysis, the study enables a replicable synthesis of how the four approaches are enacted in contemporary academic practice, particularly through the value types that are explicitly identified and directly included into research processes.

2.1. Phase 1: Identification of Data Source, Data Search, and Data Selection

The first research phase comprised the following: (1) profiling data sources and selecting an appropriate database for collecting scholarly works, (2) creating the initial search string to determine the scope of data sources, and (3) creating the control search string to more directly link data sources with the research problem and subject.

2.1.1. Profiling Data Sources

Scopus was identified as the relevant database for collecting scholarly works in architecture, aligning with the authors’ research standpoint. This choice is well-justified through the existing academic literature, which highlights Scopus’s comprehensive scope, interdisciplinary coverage, and metadata accuracy [69,70].

2.1.2. Initial Search String

The initial search of the Scopus database encompassed the following: (1) data searching based on the input of primary and secondary keywords defined concerning the research problem and subject; and (2) data narrowing of scholarly works based on a defined set of criteria. Data sources indexed in the Scopus database up to 1 December 2024 were included.

- Data Searching

The primary and secondary keywords were searched within the title, abstract, and keywords of the scholarly works. The primary keywords related to the research field included the following: (1) architecture; (2) cultural heritage; and (3) values. The secondary keywords related to the research subject encompassed the names of the four main approaches to cultural heritage preservation: (1) material-based approach; (2) value-based approach; (3) living heritage approach; and (4) historic urban landscape approach. Based on the defined keywords, a total of 293 scholarly works were found: 40 related to the material-based approach, 192 related to the value-based approach, 39 related to the living heritage approach, and 22 related to the historic urban landscape approach.

- Data Narrowing

The sample of scholarly works (a total of 293) was narrowed down by introducing additional criteria to obtain a final relevant data sample for further analysis. The criteria for narrowing the data sample and the rationale for their definition are detailed in Table 1. The temporal framework of the published works was not considered, as it would have potentially excluded scholarly works studying one of the four main approaches to cultural heritage preservation, which would have affected the scope and relevance of the conducted research. Based on the applied criteria, a total of 97 academic articles were identified, of which 14 focused on the material-based approach, 65 on the value-based approach, 11 on the living heritage approach, and 7 on the historic urban landscape approach. By introducing the narrowing criteria, especially criteria C4, C5, and C6, it was possible to identify how well the academic articles, based on the defined primary and secondary keywords, align with this research problem and subject. The introduction of the additional criterion C7—which concerns the duplicate elimination and the grouping of academic articles according to the applied approach to cultural heritage preservation—resulted in the final relevant sample of 77 academic articles, of which 27 focused on the material-based approach, 30 on the value-based approach, 13 on the living heritage approach, and 7 on the historic urban landscape approach.

Table 1.

Set of criteria for data narrowing (provided by authors, 2025).

2.1.3. Control Search String

The control search of the Scopus database was conducted with the aim of establishing a more direct connection between the relevant sample of data sources and the problem and subject of this research study. As with the initial search, it included the following: (1) data searching based on the input of primary and secondary keywords redefined in relation to the initial search; and (2) data narrowing of scholarly works based on a previously defined set of criteria (Table 1).

- Data Searching

Primary and secondary keywords were once again searched within the title, abstract, and keywords of the scholarly works. In order to identify those that more directly address one of the four recognised main approaches to cultural heritage preservation, the search keywords within the Scopus database were redefined. The primary keyword, related to the research field, was (1) heritage, while the secondary keywords, related to the subject of the research, represented the names of the four recognised main approaches to cultural heritage preservation. They were specified using quotation marks as follows: (1) “material-based approach”; (2) “value-based approach”; (3) “living heritage approach”; and (4) “historic urban landscape approach”. Based on the defined keywords and their search within the title, abstract, and keywords of scholarly works, a total of 123 works were identified: 5 related to the material-based approach, 44 related to the value-based approach, 12 related to the living heritage approach, and 62 related to the historic urban landscape approach.

- Data Narrowing

The sample of scholarly works (a total of 123) was narrowed by introducing additional criteria, with the aim of obtaining a final relevant data sample for further analysis. Based on the applied set of criteria for data narrowing (Table 1), a total of 62 academic articles were identified: 4 focused on the material-based approach, 21 focused on the value-based approach, 7 focused on the living heritage approach, and 30 focused on the historic urban landscape approach. By introducing the additional criterion C7, the final relevant sample of 53 academic articles was obtained, of which 1 focused on the material-based approach, 15 focused on the value-based approach, 7 focused on the living heritage approach, and 30 focused on the historic urban landscape approach.

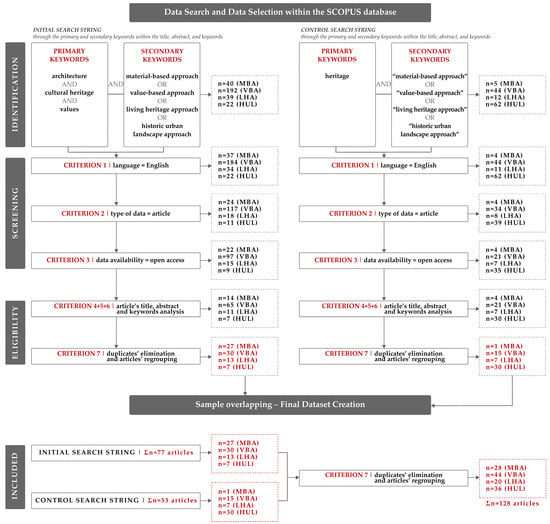

2.2. Phase 2: Sample Overlapping–Final Dataset Creation

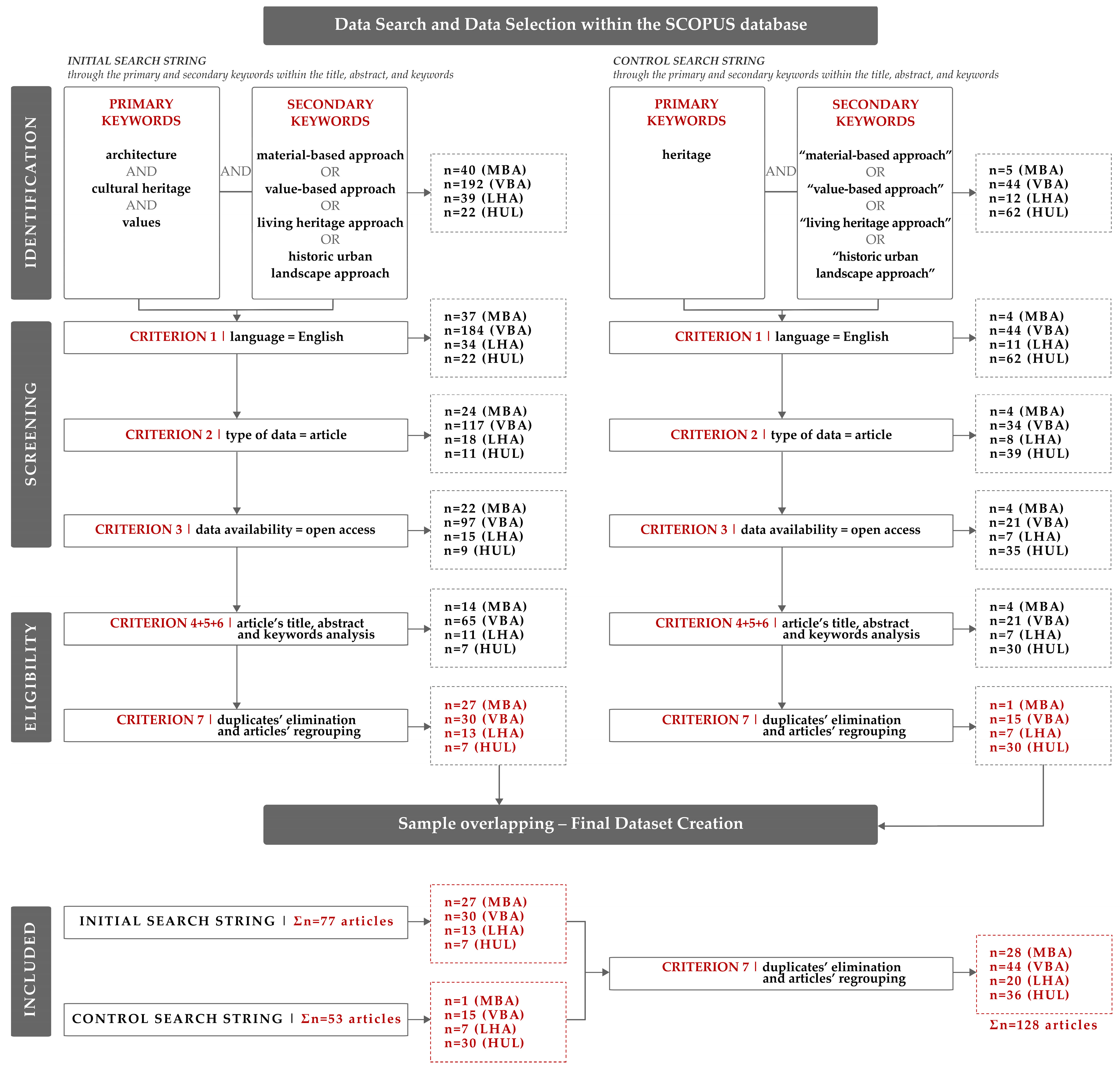

Based on the results obtained from the initial and control search strings of the Scopus database, two samples of relevant data sources were formed. Phase 2 of the research focused on systematically merging these two samples in order to construct a single, coherent final dataset. As illustrated in Figure 2, this phase involved a parallel and transparent comparison of the two samples, enabling the identification of their overlap and convergence. The process comprised the following: (1) the systematisation of academic articles according to the applied approach to cultural heritage preservation, (2) the identification and elimination of duplicate records, and (3) the regrouping of articles to ensure consistency across the four analytical categories. The PRISMA-style diagram presented in Figure 2 provides a detailed visual account of the sample overlapping process, clearly tracing how the initial and control search strings progressively converged toward the final dataset. On the other hand, Table 2 shows the number of data sources from the initial and control search strings based on the criteria used to narrow and define academic articles for further bibliometric and content analysis.

Figure 2.

Data search and data selection (provided by authors, 2026) The full resolution of this figure is provided within the Supplementary Material S2.

Table 2.

Two samples of relevant data sources (provided by authors, 2025).

In the subsequent steps, the refined sample is further structured according to the predefined criteria, resulting in a final dataset that is methodologically transparent, reproducible, and fully aligned with the research design.

- Data Systematisation

The data systematisation and their grouping according to the applied approach to cultural heritage preservation was possible through an analysis of the title, abstract, and keywords of the articles (application of the criteria C4, C5, and C6). Additionally, they were systematised into four groups: (1) MBA, (2) VBA, (3) LHA, and (4) HUL.

- Duplicate Elimination

The two data samples constitute the primary source of information relevant to this research problem and subject. The systematisation of academic articles also allowed the identification of potential duplicates. By applying the additional criterion C7—which pertains to the elimination of duplicates and the grouping of academic articles according to the applied approach to cultural heritage preservation—the final relevant data sample for further content analysis was defined: 128 academic articles (Supplementary Material S1). Of these, 28 focus on the material-based approach, 44 examine the value-based approach, 20 address the living heritage approach, and 36 academic articles analyse the historic urban landscape approach (Table 3).

Table 3.

Final sample of relevant data sources (provided by authors, 2025).

2.3. Phase 3: Bibliometric Analysis

Following the definition of the final relevant data sample (128 academic articles), a bibliometric analysis was carried out involving the following: (1) article publishing trends and (2) source journals.

- Article Publishing Trends

The trend in the publication of academic articles indicates the relevance of the research topic. The bibliometric analysis enabled the highlighting of the currency and potential dominance of one of the four main approaches over time, as well as the simultaneous representation of research addressing various approaches.

- Source Journals

The analysis of the academic journals where the articles were published enabled the identification of the research arenas to which they belong, the potential predominance of any specific research arena, and the journal’s impact. Furthermore, the obtained data indicate the degree of interdisciplinarity and transdisciplinarity of the research problem—the question of cultural heritage values and their manifestation through the application of one of the four main approaches to cultural heritage preservation. The relationship between the identified academic journals and the published articles is presented in Supplementary Material S1.

2.4. Phase 4: Content Analysis

The content analysis was conducted concerning the academic articles’ grouping according to the four main approaches to cultural heritage preservation: (1) MBA, (2) VBA, (3) LHA, and (4) HUL. It encompassed the following: (1) the article type, research arena, and value existence analysis, (2) representation of the value types recognised within the analysed articles, (3) identification of the value types directly included in the research process, and (4) representation of the value types directly included in the research process. Based on the content analysis conducted, the research objectives of this paper were achieved: (1) a systematic overview of the relationship between recognised value types and those directly involved in cultural heritage preservation on the one hand, and the applied approaches to cultural heritage preservation on the other, and (2) the identification of the dominance of specific value types/certain approaches within the process of cultural heritage preservation.

- Article Type, Research Arena, and Value Existence Analysis

The identification of the article type provided insight into how a particular research problem is viewed: (1) through a literature review, (2) by developing and applying specific methods, or (3) through the case study analysis (or their combination). Additionally, classifying the academic articles according to the research arenas allowed for an understanding of the interdisciplinarity and transdisciplinarity of the topic. On the other hand, based on the identification of the notion of value and its treatment in academic articles, a set of articles was identified in which specific value types were directly included in the research process. The value existence analysis distinguishes between several analytically relevant conditions:

- Articles in which cultural heritage values are not identified;

- Articles in which the term “value” is used descriptively or metaphorically but remains analytically irrelevant to the research objectives;

- Articles in which value types are recognised or mentioned but not operationalised;

- Articles in which specific value types are explicitly and directly integrated into the research methodology through criteria, indicators, evaluative frameworks, or scoring systems.

This distinction allows for a reading of how the notion of value is treated within contemporary academic practice, moving beyond mere terminological presence toward assessing the degree of methodological engagement with values. The same analytical logic was consistently applied across all four approaches, enabling a comparative examination of differences in how cultural heritage values are recognised, conceptualised, and operationalised within each approach. The results of this classification are presented in Appendix A (Table A1, Table A2, Table A3 and Table A4), which collectively supports the comparative analysis discussed in Section 3.2.

- Representation of the Value Types Recognised Within the Analysed Articles

The content analysis of academic articles, in which a specific value type was identified, enabled the listing of all recognised value types, with a particular focus on their representation. In this way, the most frequently represented value types were highlighted. The results of this research step are organised according to the four main approaches to cultural heritage preservation and presented in Supplementary Material S1.

- Identification of the Value Types Directly Included in the Research Process within the Analysed Articles

The content analysis enabled the identification of academic articles in which specific value types were directly included in the research process. The results of this research step are presented in a set of tables (Appendix A, Table A1, Table A2, Table A3 and Table A4), organised according to the approach to cultural heritage preservation applied in the research process.

- Representation of the Value Types Directly Included in the Research Process within the Analysed Articles

Based on the identification of the value types directly included in the research process, it was possible to observe the degree of their representation through the analysed articles. The results of this research step are organised according to the four main approaches to cultural heritage preservation and presented in Supplementary Material S1.

3. Results

As a result of the Scopus database search and the analysis of a relevant data sample of the academic articles, the following are presented: (1) a bibliometric analysis, and (2) a content analysis.

3.1. Bibliometric Analysis

The bibliometric analysis carried out on the relevant sample of academic articles encompasses an examination of the (1) article publishing trends, and (2) source journals. The bibliometric analysis is not intended to be an end in itself, but to be a contextual layer that frames the subsequent content analysis. By tracing publication dynamics, journal outlets, and disciplinary clustering, it provides insight into how value-oriented heritage research has evolved alongside shifts in policy frameworks, methodological agendas, and applied heritage practices.

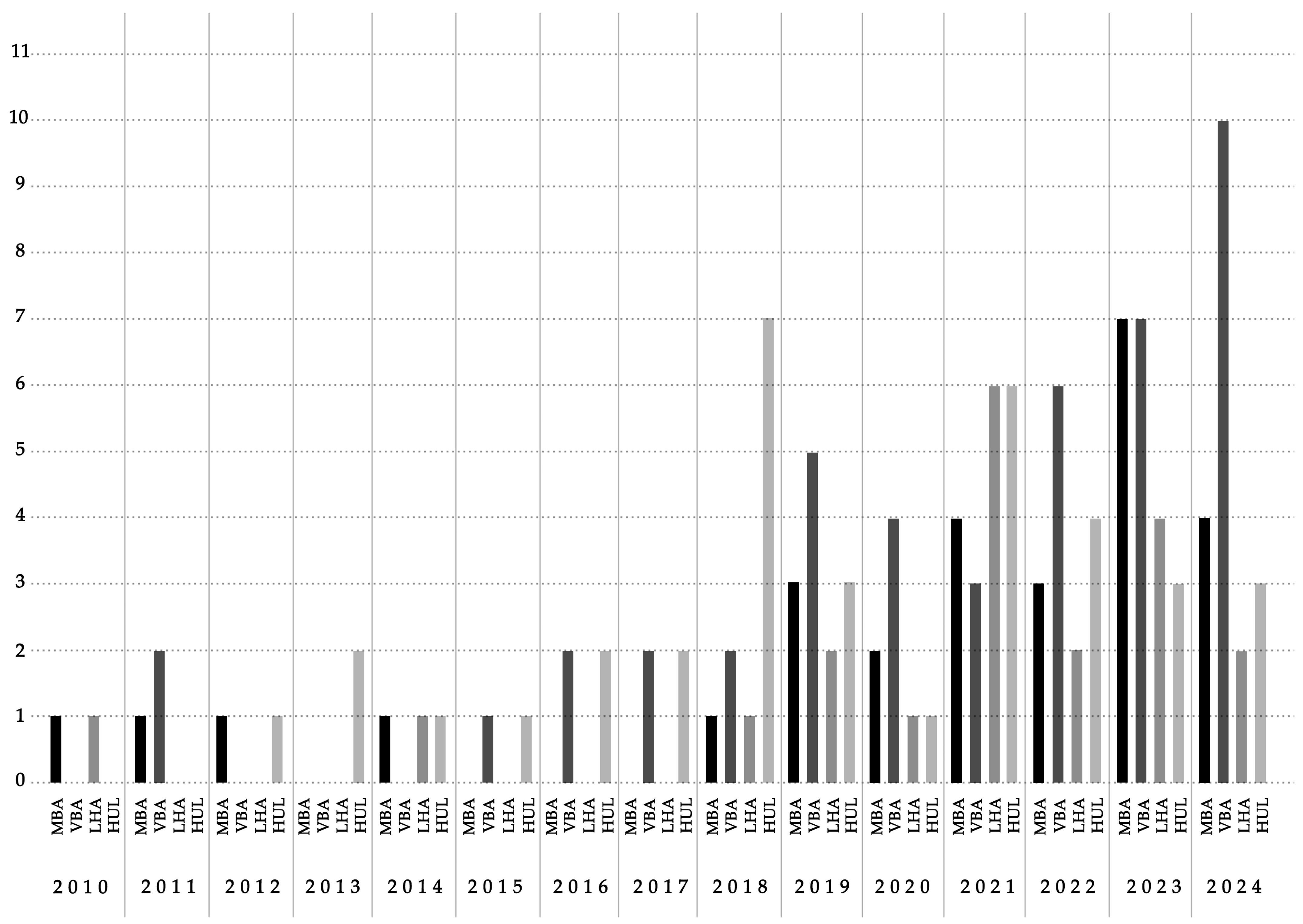

- Article Publishing Trends

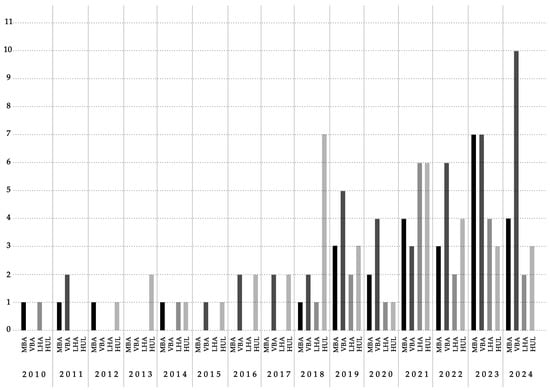

Figure 3 illustrates the annual publishing trend of the analysed academic articles, considering the main approach to cultural heritage preservation (MBA, VBA, LHA, or HUL). It illustrates that researching these approaches gained prominence in 2010. The annual publication count indicates that the subject has been particularly topical in the last four years, as 57.81% of the analysed data sample (74 articles) were published between 2021 and 2024. It is also observed that, until 2018, research was oriented towards the analysis of various approaches; however, not all four main approaches were represented simultaneously. Since 2018, research focused on the HUL has emerged, accounting for 19.44% (seven articles) of the total data sample. Research focused on the MBA has appeared intermittently since 2010. From 2018, the number of published articles has increased, reaching 25% (seven articles) of the total data sample in 2023. The year 2021 was significant for researching the LHA, when 30% (six articles) of the total data sample were published. Articles emphasising the VBA became prominent in 2022, while in 2024 they comprised 19.3% (10 articles) of the total data sample. The observed increase in publications after 2010, and particularly since 2018, corresponds with the consolidation and wider uptake of integrative heritage frameworks, most notably the LHA and HUL approaches. This temporal pattern reflects a gradual shift from object- and fabric-centred conservation toward process-oriented, value-driven, and context-sensitive practices, in which questions of value identification, negotiation, and operationalisation become increasingly central. The uneven temporal representation of the four approaches also indicates that methodological experimentation with value assessment emerges at different paces, shaping how and when values are translated from conceptual frameworks into heritage preservation practices.

Figure 3.

Bibliometric analysis—article publishing trends (provided by authors, 2025).

- Source Journals

Based on the analysis of the journals’ characteristics, it was established that 128 academic articles were published across 69 different journals (Supplementary Material S1). The most significant number of journals publish articles focused on researching the VBA (value-based approach) (47.83%, 33 journals), followed by the HUL (historic urban landscape approach) (30.43%, 21 journals), and the MBA (material-based approach) (30.43%, 21 journals), while journals dedicated to publishing articles which research the LHA (living heritage approach) are less represented (20.29%, 14 journals). Among the identified journals, only two have published articles that investigate all four main approaches (Table 4). The Journal of Cultural Heritage Management and Sustainable Development stands out particularly, with a total of 12 academic articles (9.37% of the relevant data sample). It spans the fields of Arts and Humanities, Social Sciences, and Business, Management and Accounting [71]. Although Sustainability also publishes articles exploring all four main approaches to cultural heritage preservation, evidenced by the fact that 13 articles (10.16% of the relevant data sample) appear in it, it has a particular emphasis on researching the VBA (value-based approach) and the HUL (historic urban landscape approach). It covers Social Sciences, Computer Science, Environmental Science, and Energy [72]. In addition to the aforementioned journals, 15 others have published two or more articles, each focusing on researching one of the four main approaches to cultural heritage preservation (Table 4).

Table 4.

Journal information and number of articles (provided by authors, 2025).

The concentration of publications within a relatively limited set of journals further illustrates the institutionalisation of value-oriented heritage research within specific disciplinary and editorial contexts. Journals that consistently publish across multiple approaches function as key arenas where methodological conventions for value assessment are formed, stabilised, and disseminated. This concentration also suggests that the ways in which values are framed, prioritised, and operationalised are partly shaped by dominant publication venues, which in turn inform the patterns identified in the subsequent content analysis. Together, these bibliometric patterns informed the design and interpretation of the content analysis by indicating where dominant research agendas and publication practices are most likely to influence the recognition and direct operationalisation of cultural heritage values.

3.2. Content Analysis

The content analysis focused on the identification, representation, and direct inclusion of value types in the research process. The results are organised according to the four main approaches to cultural heritage preservation. They present the following: (1) article type, research arena, and value existence analysis, (2) representation of the value types recognised within the analysed articles, (3) identification of the value types directly included in the research process, and (4) representation of the value types directly included in the research process.

3.2.1. MBA: Material-Based Approach

- Article Type, Research Arena, and Value Existence Analysis

Analysing the academic articles focused on the MBA (material-based approach) (28 articles) indicates that they cover nine research arenas (Appendix A, Table A1), the most prevalent of which is heritage conservation (25%, seven articles). Research in each of the analysed articles involves the analysis of the case studies (100%, 28 articles), with some focusing exclusively on case study analysis (21.43%, 6 articles), and others applying a specific methodology to a case study (60.71%, 17 articles), or combining theoretical knowledge, a proposed methodology, and its application to a case study (17.86%, 5 articles) (Appendix A, Table A1). Furthermore, it was determined that three articles do not recognise any cultural heritage values (10.71%) [73,74,75]. In contrast, in seven articles (25%) [76,77,78,79,80,81,82], the term “value” is employed solely to explain specific parameters and characteristics that are not relevant to the problem and subject of this research. Conversely, in 14 articles (50%) [83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96], types of cultural heritage values relevant to this research were recognised. Specific value types were directly included in the research process in four articles (14.29%) [97,98,99,100] (Table 5).

Table 5.

MBA—identification of the value types directly included in the research process.

- Representation of the Value Types Recognised within the Analysed Articles

A total of 44 value types were identified, among which the most prominent are as follows: cultural (50%, nine articles), historical (44.44%, eight articles), architectural (38.89%, seven articles), and heritage (22.22%, four articles), as well as artistic and symbolic values (16.67%, three articles) (Supplementary Material S1).

- Identification of the Value Types Directly Included in the Research Process within the Analysed Articles

Although a large number of value types were recognised, only four articles demonstrated an effort to include them directly in the research process (Table 5). Among these, two articles employ valorisation to determine the level of significance [97] and the state of the cultural heritage’s preservation [98], while one article recognises the aspects influencing heritage development over time [99]. The research conducted by Moscatelli directly includes a specific value type—expressive value—in the research process [100].

- Representation of the Value Types Directly Included in the Research Process within the Analysed Articles

Given that only one value type—expressive value—was directly included in the research process within the analysed articles (Table 5), it was not possible to examine the representation of value types directly included in the research process through the analysis of articles focused on the application of the MBA (material-based approach).

3.2.2. VBA: Value-Based Approach

- Article Type, Research Arena, and Value Existence Analysis

By analysing the academic articles oriented towards the VBA (value-based approach) (44 articles), it was highlighted that they encompass eighteen research arenas (Appendix A, Table A2), among which the most represented is heritage preservation (27.27%, 12 articles). The most significant number of articles (36.36%, 16 articles) theoretically analyse a specific problem, define and develop research methods, and apply them to a particular case study (Appendix A, Table A2). From the 44 articles, content analysis determined that 28 articles (63.64%) [33,39,66,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125] recognise specific value types, whereas they are directly included in the research process in 16 articles (36.36%) [126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140,141] (Table 6).

Table 6.

VBA—identification of the value types directly included in the research process.

- Representation of the Value Types Recognised within the Analysed Articles

A total of 306 different value types were recognised within the analysed articles (Supplementary Material S1). Of these, the most prominent are the following ones: cultural (72.73%, 32 articles), aesthetic (56.82%, 25 articles), heritage (52.27%, 23 articles), economic, historical and social (50%, 22 articles); then historic and scientific (31.8%, 14 articles), intrinsic (29.55%, 13 articles), spiritual (27.27%, 12 articles), architectural, educational, and intangible (25%, 11 articles), environmental, human, and tangible (20.45%, 9 articles); followed by symbolic and use (18.18%, 8 articles), added, community and political (15.91%, 7 articles), ecological and identity (13.64%, 6 articles), and artistic and archaeological (11.36%, 5 articles).

- Identification of the Value Types Directly Included in the Research Process within the Analysed Articles

Specific value types were directly included in the research process in 16 articles (Table 6). Notably, some articles clearly define a set of value types directly included in the research process [127,128,129,130,131,132,134,135,136,137,138,139,140]. Additionally, some studies include defined indicators for the directly included value types [128,130,135,137,138]. Two articles use the term “significance”, equating it with values [126,133]. Furthermore, three articles identify criteria for recognising values [137,139,141].

- Representation of the Value Types Directly Included in the Research Process within the Analysed Articles

Based on a content analysis of the 16 articles, 105 value types were directly included in the research process. However, only 16 value types are represented in more than 10% of the analysed articles. Among these, the most prominent are the following: economic (56.25%, nine articles), aesthetic (43.75%, seven articles), cultural, historical, and scientific (37.5%, six articles), social (31.25%, five articles), architectural, educational, historic, spiritual, and symbolic (18.75%, three articles), and ecological, environmental, heritage, intrinsic, and landscape (12.5%, two articles) (Supplementary Material S1).

3.2.3. LHA: Living Heritage Approach

- Article Type, Research Arena, and Value Existence Analysis

An analysis of the academic articles focused on the LHA (living heritage approach) (20 articles) indicates that they encompass seven research arenas (Appendix A, Table A3), among which the most represented is heritage management (45%, nine articles). The majority of articles focus on case study analysis conducted either in part or throughout the entire article (90%, 18 articles). To a lesser extent, articles that predominantly analyse a research problem through a literature review and theoretical development within the research field are also present (10%, two articles), as are those focusing on a combination of a literature review and case study analysis (15%, three articles) (Appendix A, Table A3). The content analysis determined that 13 articles (65%) [38,44,142,143,144,145,146,147,148,149,150,151,152] recognise different value types, whereas 7 articles (35%) [45,153,154,155,156,157,158] directly include different value types in the research processes (Table 7).

Table 7.

LHA—identification of the value types directly included in the research process.

- Representation of the Value Types Recognised within the Analysed Articles

A total of 130 different value types of cultural heritage were identified (Supplementary Material S1). The most prominent among them are as follows: social (45%, nine articles), cultural (40%, eight articles), heritage and historical (35%, seven articles), aesthetic and economic (30%, six articles), and religious and use value (25%, five articles). Following these are the following: inherent, socio-cultural, and traditional (20%, four articles), as well as artistic, ecological, historic, intangible, intrinsic, spiritual, and tangible (15%, three articles).

- Identification of the Value Types Directly Included in the Research Process within the Analysed Articles

Among the analysed academic articles, specific value types were directly included in the research process in seven of them (Table 7). Notably, some articles clearly define a set of value types that were identified and directly included in the research process [45,154,158]. Additionally, other articles not only identify and directly include specific value types but also define corresponding indicators [153,155,156,157]. Particularly noteworthy is an article in which the value types are grouped according to the stakeholders which identified them [154], as well as a study focusing on the analysis of garden culture as heritage [153], in which, by cross-referencing theoretical data on garden values with interview data from garden owners, a specific value matrix is developed. The lack of “doing value” is also recognised as a distinct value type.

- Representation of the Value Types Directly Included in the Research Process within the Analysed Articles

Based on content analysis of the 16 articles, 25 value types were directly included in the research process (Supplementary Material S1). However, only two value types are mentioned in more than one article: aesthetic and social (28.57%, two articles). This outcome is a result of the specific nature of the topics studied, as well as the fact that in numerous articles, in addition to the identified value types, corresponding indicators that cover other value types are also identified, as shown in Table 7.

3.2.4. HUL: Historic Urban Landscape Approach

- Article Type, Research Arena, and Value Existence Analysis

An analysis of the academic articles focused on the HUL (historic urban landscape approach) (36 articles) indicates that they span eight research arenas (Appendix A, Table A4), among which the most represented is heritage management (55.5%, 20 articles). The majority of articles (77.78%, 28 articles) include case study analysis. Considering that this approach is relatively recent within the field of heritage preservation, articles focused on its theoretical and critical examination are also highly presented (22.22%, eight articles). Additionally, a notable number of articles combine theoretical analysis of the research problem, development of methodological tools, and their application to a case study (16.67%, six articles) (Appendix A, Table A4). Among the 36 articles analysed, content analysis found that 29 articles (80.55%) [37,48,54,55,56,57,58,59,61,63,64,159,160,161,162,163,164,165,166,167,168,169,170,171,172,173,174,175,176] recognise different value types. However, only six articles (16.67%) [177,178,179,180,181,182] directly include specific value types in the research process (Table 8), while one article does not address the notion of value [183].

Table 8.

HUL—identification of the value types directly included in the research process.

- Representation of the Value Types Recognised within the Analysed Articles

A total of 171 different value types were identified among the analysed articles (Supplementary Material S1). The most predominantly represented are the following: cultural (71.43%, 25 articles), heritage (60%, 21 articles), intangible and natural (40%, 14 articles), historic and social (37.14%, 13 articles), outstanding universal (34.29%, 12 articles), historical (31.43%, 11 articles), and architectural and aesthetic (28.57%, 10 articles). Following these are the following value types: scientific (25.71%, nine articles), economic and tangible (22.86%, eight articles), symbolic (17.14%, six articles), archaeological, artistic, environmental, and spiritual (14.29%, five articles), and ecological, new, property, socio-cultural, and urban heritage (11.43%, four articles).

- Identification of the Value Types Directly Included in the Research Process within the Analysed Articles

Among the analysed academic articles, specific value types were directly included in the research process in six of them (Table 8). Some articles explicitly define a set of value types [178,179,180,182], while the corresponding indicators were identified in one article [181].

On the other hand, in the research conducted by Rey-Perez et al. [177], although value types were identified, the methodology for recognising and including them in the research process is not specified—this is justified by the article’s aim in presenting the scientific project’s results.

- Representation of the Value Types Directly Included in the Research Process within the Analysed Articles

Based on the content analysis of six articles, 30 value types directly included in the research process have been identified (Supplementary Material S1). However, only seven value types are referenced in more than one article: social (50%, three articles), and architectural, cultural, environmental, historic, scientific, and outstanding universal (33.33%, two articles).

4. Discussion

Based on the content analysis and the obtained research results, it was possible to compare and interpret them. Particular attention was paid to the following: (1) value representation in current approaches to cultural heritage preservation, and (2) identification of the dominance of specific value types/approaches in the process of cultural heritage preservation.

While the content analysis reveals clear patterns in the frequency and distribution of cultural heritage value types, its analytical scope lies in examining how values are framed, prioritised, and operationalised within contemporary academic practice. The dominance of certain value types should therefore be understood not as a direct reflection of societal or stakeholder-based valuation processes, but as an indicator of prevailing disciplinary conventions, methodological trajectories, and regulatory logics that structure heritage-related research. In particular, values such as scientific, artistic, historic, and social [181], as well as outstanding universal [135,179], tend to dominate because they align more readily with established planning instruments, assessment frameworks, and policy-oriented methodologies [9,12,184,185], making them easier to formalise and integrate into research designs. Conversely, relational, experiential, and socially negotiated values, although widely recognised, are less frequently operationalised due to their methodological complexity and reliance on participatory and perception-based research approaches [45,135,137,140,178,180,181]. This interpretive perspective is consistent with the refined research questions and the overall aim of the study, which is to provide a cross-cutting synthesis of how cultural heritage values are stabilised and mobilised within contemporary academic practice, thereby complementing applied [45,178,181], governance-oriented [135,182], and perception-based studies [137,140,154] that address value formation in specific contexts.

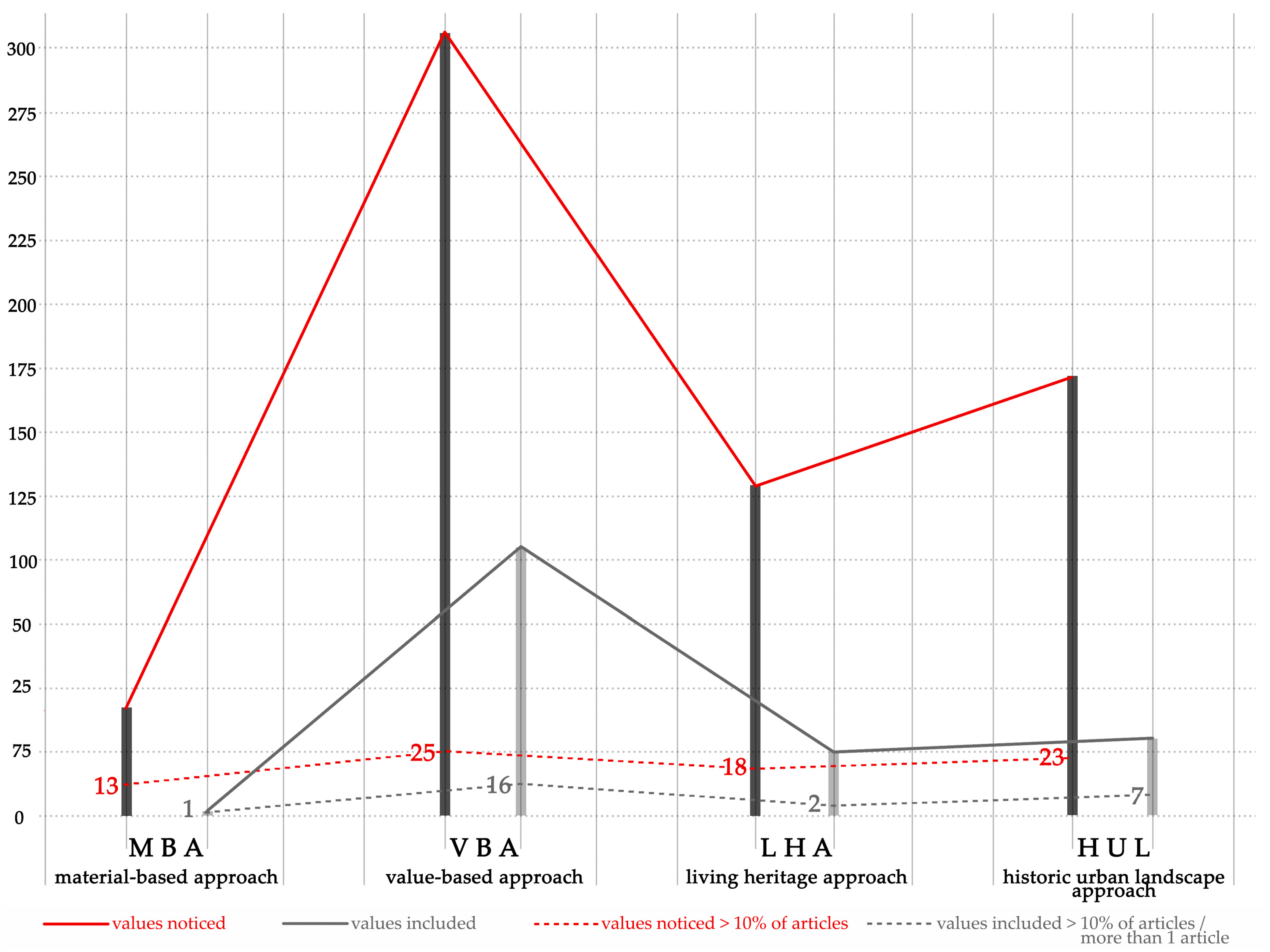

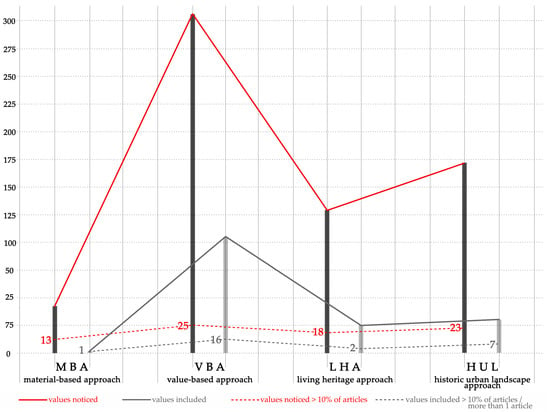

4.1. Value Representation in Current Approaches to Cultural Heritage Preservation

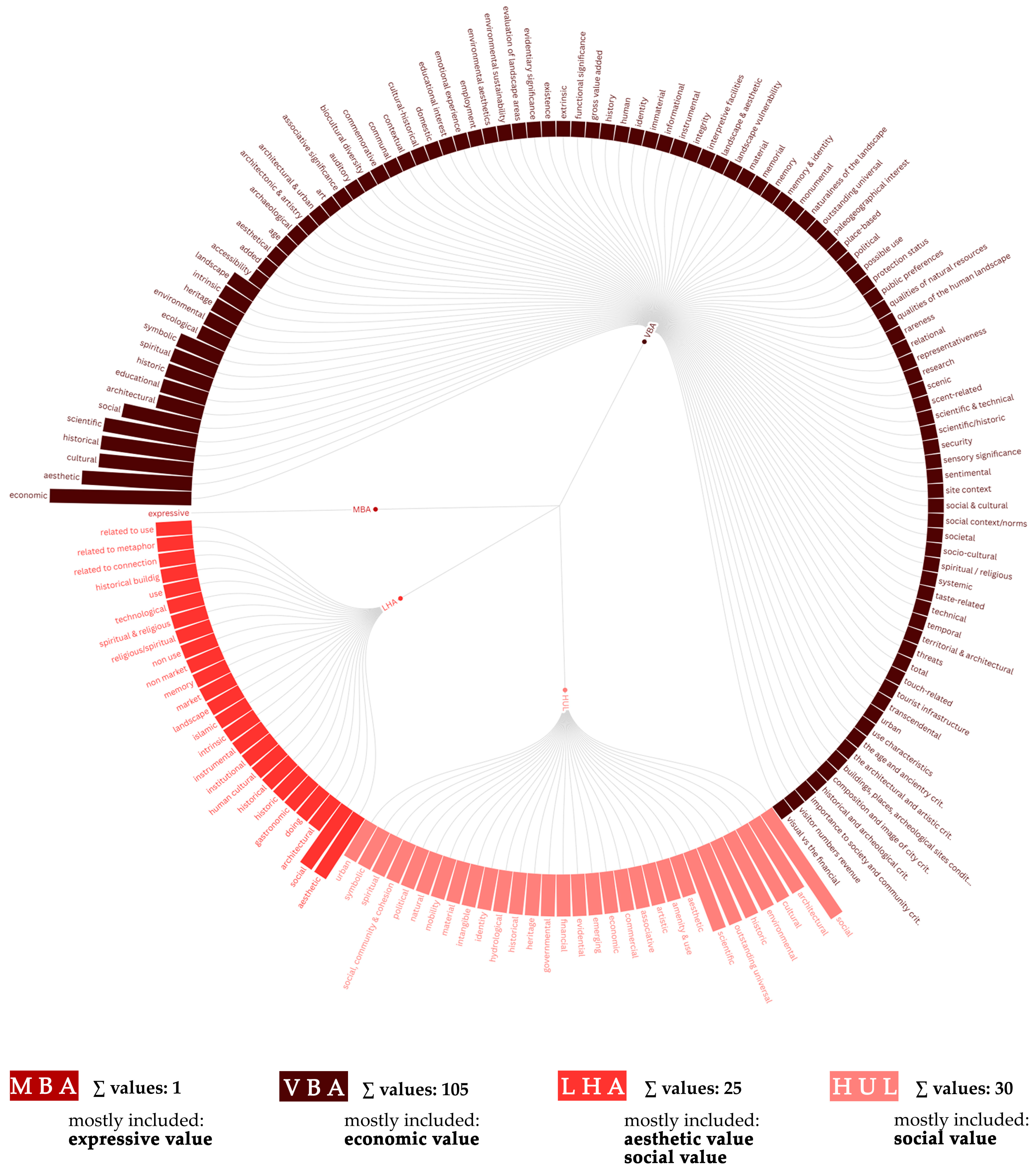

The comparison of the obtained research results involved analysing the degree of representation and direct involvement of specific value types in the research process within the analysed academic articles concerning the four main approaches to cultural heritage preservation. Figure 4 provides a synthetic depiction and numerical insight into the relationship between the recognised value types and those directly included in the process of cultural heritage preservation, on the one hand, and the applied approaches, on the other. It highlights discrepancies between the total number of value types that were recognised and those directly involved in the research process, both within a single approach (MBA: 44–1, VBA: 306–105, LHA, 130–25, and HUL: 171–30) and in their mutual comparison. Also, a difference was observed between the total number of recognised value types and those represented in more than 10% of the analysed relevant data sample (MBA: 44–13, VBA: 306–25, LHA, 130–18, and HUL: 171–23). The aforementioned discrepancy was also highlighted in the relationship between the total number of identified value types directly involved in the research process and those directly involved in more than 10% of the analysed relevant data sample (MBA: 1–1, VBA: 105–16, LHA: 25–2, and HUL: 30–7).

Figure 4.

Representation of the value types recognised/included in the analysed articles (provided by authors, 2025).

Rather than interpreting these discrepancies as methodological inconsistency or analytical deficiency, the results suggest that such variation may be inherent to the nature of cultural heritage values themselves. Value plurality, selective operationalisation, and uneven representation across approaches reflect the context-dependent and often conflicting character of heritage values [185], which are shaped by disciplinary traditions, research objectives, and institutional frameworks. In this sense, inconsistency should not be understood solely as a failure of methodological rigour, but also as an epistemologically productive condition that reveals how different approaches prioritise, stabilise, or bracket specific values in response to distinct analytical and practical demands. This reading aligns with recent empirical [137] and perception-based studies [140] that conceptualise value plurality and trade-offs as constitutive features of heritage processes rather than anomalies to be resolved. From this perspective, the uneven translation of recognised values into operational research categories does not necessarily indicate conceptual weakness, but instead exposes the limits of their formalisation.

At the same time, the observed patterns of value representation must be situated in relation to dominant normative heritage doctrines, such as those promoted by UNESCO [9,21,30,31,32] and ICOMOS [8,18,28,29], which have played a central role in structuring the vocabulary and categorisation of heritage values [1]. While these frameworks have been instrumental in broadening the understanding of heritage beyond material fabric, their widespread adoption within contemporary academic practice has also contributed to a certain terminological stabilisation that is not always matched by corresponding methodological innovation. As a result, values articulated within normative doctrines are frequently recognised at a conceptual level, yet only selectively translated into operational research tools. By critically positioning these findings vis-à-vis normative heritage frameworks, the analysis highlights a gap between doctrinal ambition and research practice. This gap has been increasingly problematised in recent scholarship that empirically tests, adapts, or challenges normative value categories through participatory methods [45,140], governance-oriented analyses [135,182], and context-sensitive modelling [178,181]. The discrepancies identified in Figure 4 can therefore be read as indicators of an ongoing tension between the normative expansion of value concepts and the practical constraints of their operationalisation within research- and planning-oriented contexts.

4.2. Dominance Identification of Specific Value Types/Approaches in the Process of Cultural Heritage Preservation

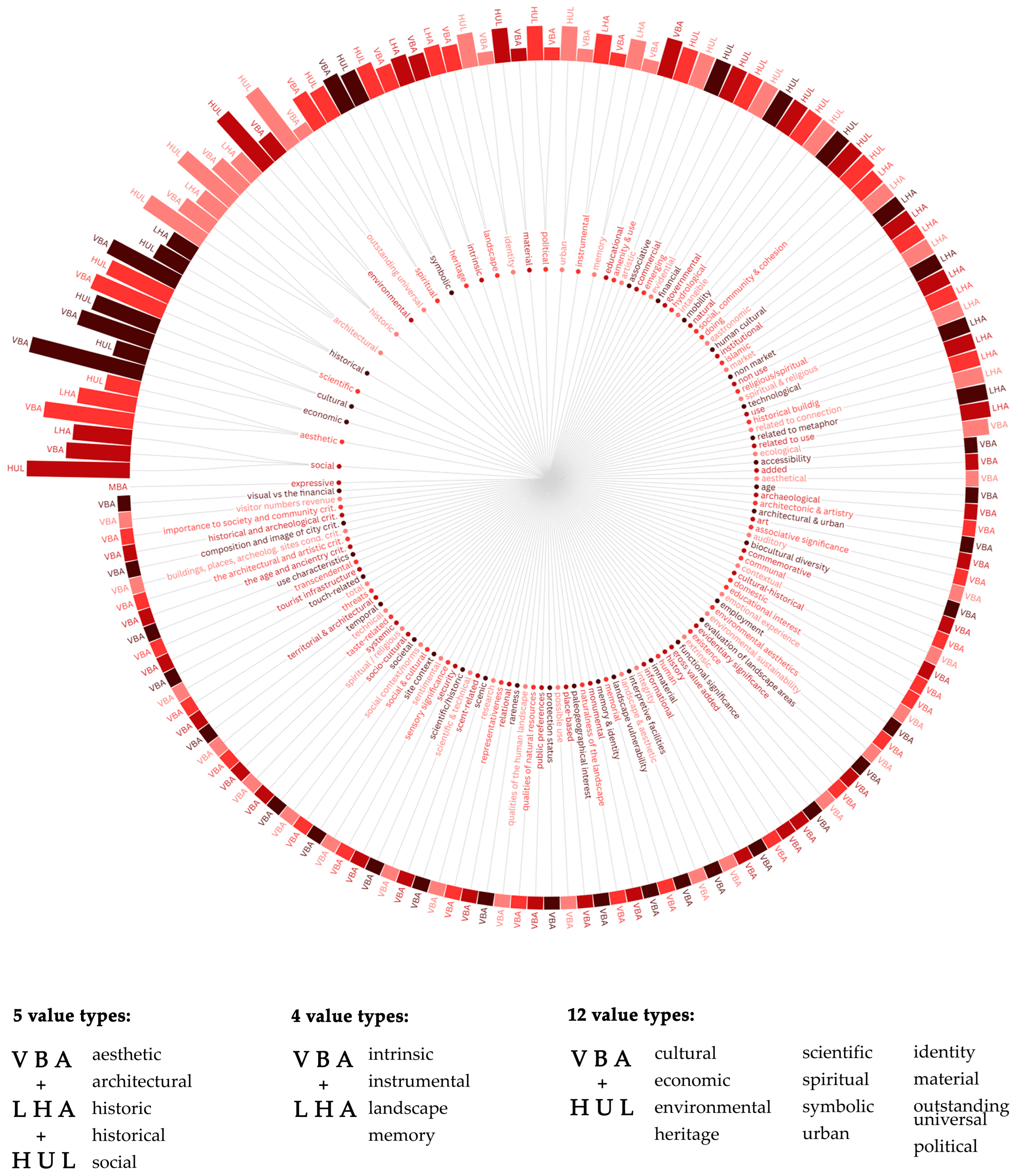

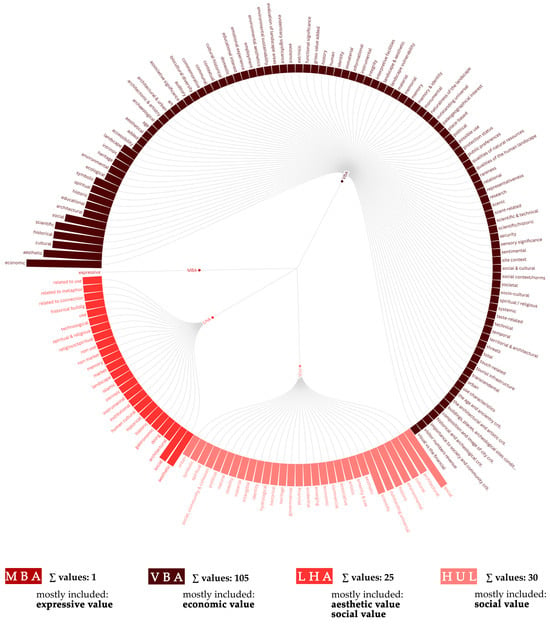

An insight into the relationship between all recognised value types and those directly involved in the research process within the analysed academic articles enabled the identification of 134 different value types directly included in the research process through the application of one of the four main approaches to cultural heritage preservation. Based on the obtained data, it was possible to conduct a comparative analysis aimed at identifying the potential dominance of (a) any of the four main approaches from the perspective of direct inclusion of specific value types in the research process, and (b) a specific value type, from the perspective of its direct inclusion in the research process through the application of two or more recognised main approaches to cultural heritage preservation.

Figure 5 includes a listing of all value types directly included in the research process through the application of one of the four main approaches. Specifically, it highlights the degree of the values’ inclusion within the analysed data sample. The dominance of the VBA is emphasised in terms of the number of value types directly included in the research process. Tracks on the circle of Figure 5 are allocated to each identified value type, and their lengths correspond to the level of inclusion of each value type within the analysed academic articles. Through the application of the MBA, only one value type—expressive—was directly involved in the research process. Furthermore, through the application of the VBA, the most frequently included value type is economic. On the other hand, through the application of the LHA, aesthetic and social values are equally included, whereas through the application of the HUL, the most frequently included value type is social.

Figure 5.

Four main approaches to cultural heritage preservation—representation of dominance (provided by authors, using online available and free data visualisation platform “Flourish”, 2025). The full resolution of this figure is provided within the Supplementary Material S2.

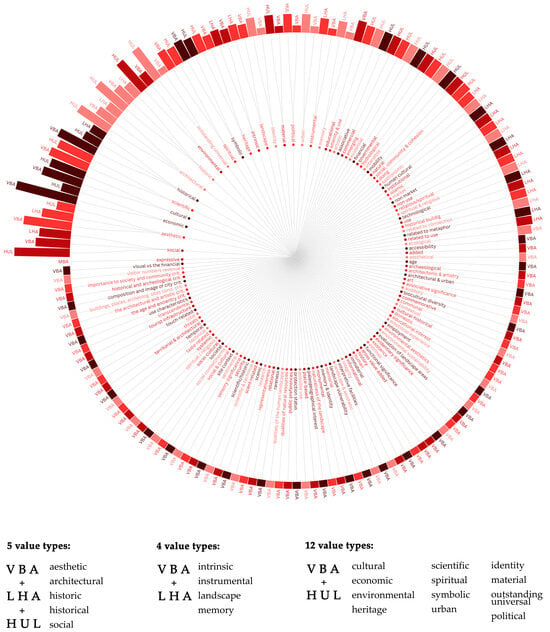

Determining the dominance of a specific value type is contingent upon its inclusion in the research process through the application of two or more of the recognised main approaches to cultural heritage preservation. Figure 6 highlights that only 21 values are directly included. Specifically, five values (aesthetic, architectural, historic, historical, and social) are directly included through the VBA, LHA, and HUL. Four values (intrinsic, instrumental, landscape, and memory) are directly included through the VBA and LHA, whereas twelve other values (cultural, economic, environmental, heritage, identity, material, outstanding universal, political, scientific, spiritual, symbolic, and urban) are directly included through the VBA and HUL.

Figure 6.

Representation of value types’ dominance (provided by authors, using online available and free data visualisation platform “Flourish”, 2026). The full resolution of this figure is provided within the Supplementary Material S2.

The observed dominance of the VBA in terms of direct value inclusion reflects its stronger methodological alignment with structured assessment frameworks, including criteria-based evaluation [130,136,137,138,179], specific value matrix development [134,153], and multi-criteria decision-support tools [127,154,178,181]. Unlike the MBA, which remains closely tied to fabric-oriented conservation logics, the VBA more readily accommodates formalised value translation mechanisms, enabling a broader range of values to be explicitly integrated into research designs. In this sense, dominance should be understood not as theoretical superiority, but as a function of methodological compatibility with evaluative and planning-oriented research practices.

Importantly, the absence of a newly proposed conceptual or methodological model in this study is deliberate. Rather than advancing an additional framework, the present review positions itself as a critical synthesis that maps how existing structured assessment models and multi-criteria approaches are selectively mobilised across heritage paradigms. By identifying which value types consistently traverse multiple approaches, and which remain confined to single frameworks, the analysis highlights points of convergence and fragmentation that can inform the further development and refinement of applied evaluative tools. The comparatively limited operationalisation of the LHA and HUL approaches should therefore not be read as a reiteration of normative critique alone, but as an empirical indication of the methodological challenges inherent in translating relational, socially negotiated, and process-oriented values into formal research instruments. Seen from this perspective, the dominance patterns identified in Figure 5 and Figure 6 reveal a structural tension between integrative heritage paradigms and the demands of comparability, reproducibility, and formalisation in contemporary academic research practice. Rather than signalling analytical weakness, the selective operationalisation of values across approaches exposes where current assessment models succeed, where they struggle, and where future methodological innovation is most urgently needed.

4.3. Limitations of the Study

Several limitations within the study scope should be acknowledged when interpreting the results. First, the analysis is based on a single bibliographic database (Scopus). While Scopus was selected due to its broad interdisciplinary coverage, metadata quality, and relevance to architecture- and heritage-related research, the inclusion of additional databases (e.g., Web of Science or discipline-specific repositories) may have resulted in a broader or slightly different dataset. In particular, reliance on a single indexed database may privilege certain publication geographies, institutional contexts, and traditions, while underrepresenting locally grounded or regionally circulated scholarship. Second, the study includes English-language publications only. This choice was made to ensure consistency and accessibility within the global academic discourse. However, it may have excluded relevant research published in other languages, particularly in regions where cultural heritage scholarship is strongly embedded in local academic traditions. This limitation is especially relevant in the context of Global South research, where critical, practice-oriented, and community-based heritage studies are often published in national journals, policy reports, or non-English outlets that fall outside mainstream indexing systems. Third, although the study adopts a bibliometric and content-analysis framework, the analytical lens is anchored in architectural and built-environment scholarship. This framing may have influenced the disciplinary distribution of the sample and the prominence of certain value types, potentially underrepresenting perspectives from the fields such as anthropology [186], sociology [187], archaeology [188], or legal heritage studies [189,190]. Fourth, the dataset is limited to peer-reviewed, open-access journal articles. This restriction was introduced to ensure a consistent and comparable analytical framework, grounded in sources that undergo multiple rounds of peer review and follow clearly defined research structures and methodologies. While this corpus is considered appropriate and relevant for the aims of the present study, the inclusion of books, edited volumes, and applied project reports could provide additional conceptual and methodological insights in future research.

These limitations do not undermine the validity of the findings but rather define the scope of the study. They should be understood as structural constraints inherent to large-scale bibliometric and content-analytic reviews, rather than as methodological shortcomings. They also point to clear directions for future research, including (1) multi-database searches, (2) multilingual sampling, (3) the systematic inclusion of monographs and edited volumes, (4) targeted inclusion of regionally situated and Global South scholarship, and (5) broader interdisciplinary integration.

5. Concluding Remarks