1. Introduction About Design Philosophy by Steven Holl

Steven Holl expresses his design ideas in a variety of ways, including through words and sketches, and he has shown a strong interest in the methodology for realizing his design ideas. Holl has three main ideas in his design philosophy [

1]. The first is the concept of “Anchoring,” which emphasizes the intentional development of a project from a specific site and program, aiming for a poetic space and architecture. The second is “Perception”, which refers to the pursuit of the spatial experiential aspects of architecture in one’s perception of space, such as natural light, daily and seasonal changes, integration with the landscape, spatial change, water, and materials. Third, Holl presents “Intertwining” as the intertwining of architectural ideas, phenomena, and site, and their fusion with other elements [

2,

3]. Holl has published several books on his design philosophy, and his ideas are expressed in his unique watercolor paintings, which have attracted much attention [

4]. Although he is highly regarded for expressing his design philosophy and architectural design concepts, he has designed a wide range of projects, from public buildings to residential buildings [

5]. Design is developed through intuitive drawing expressed via sketches, encompassing a wide range of facilities from residential homes to public buildings.

Figure 1 shows his residential design project, and

Figure 2 shows his public library design project. Therefore, this study aims to clarify the characteristics of the use of space and continuity of space in residential buildings.

“a concept, whether a rationally explicit statement or a subjective demonstration, establishes an order, a field of inquiry, a limited principle”.

Architectural concepts, in Holl’s view, are not merely theoretical constructs; they serve as functional and structural guidelines that systematically determine architectural form and the arrangement of space. In addition, he frames the experience of architecture within a dual structure of order and phenomenon, proposing that

“if we consider the order (the idea) to be the outer perception and the phenomena (the experience) to be the inner perception, then in a physical construction, outer perception and inner perception are intertwined”.

This perspective suggests that phenomenological experience in architecture is not purely subjective but is structurally mediated and supported by an underlying architectural order. Accordingly, the present study assumes that the experiential qualities of Holl’s residential projects are rooted in a systematic and analyzable spatial frame project.

Under this premise, architectural order can be assessed using quantitative measures of spatial layout and functional organization, allowing a structural reading of architectural concepts that goes beyond traditional discursive or conceptual analysis. Some of the studies on Holl have elucidated the design theory of discursive expressions and the projects [

7]. Lv (2003) conducted a study on the phenomenological design thinking exhibited by investigating the correspondence between Holl’s conceptual expression and the actual designed projects [

8]. A study focusing on a specific architectural project was conducted that clarified the design method influenced by phenomenology, focusing on the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art [

9]. Other papers examine architectural phenomena through linguistic analysis, though not limited to housing, and discuss understanding experiential spatial theory [

10]. Several studies have been conducted comparing architects’ design theories with the floor plans of their residential projects [

11,

12]. This study has a different perspective from other studies in that it uses floor plans to clarify the spatial continuity.

In this study, the examination of residential functions and spatial connection positions the research within architectural theory and offers insight into the functional and structural mechanisms underlying Steven Holl’s architectural projects. While previous studies have not explicitly focused on spatial continuity in Holl’s residential architecture, this study seeks to clarify characteristics of spatial continuity by analyzing his design philosophy. From the perspective of design theory, the proposed analytical approach contributes to an understanding of spatial design mechanisms and the processes through which design intentions are translated into architectural form.

2. Research Objectives and Methodology

This study aims to clarify the relationship between residential functions and spatial continuity in the residential projects of Steven Holl.

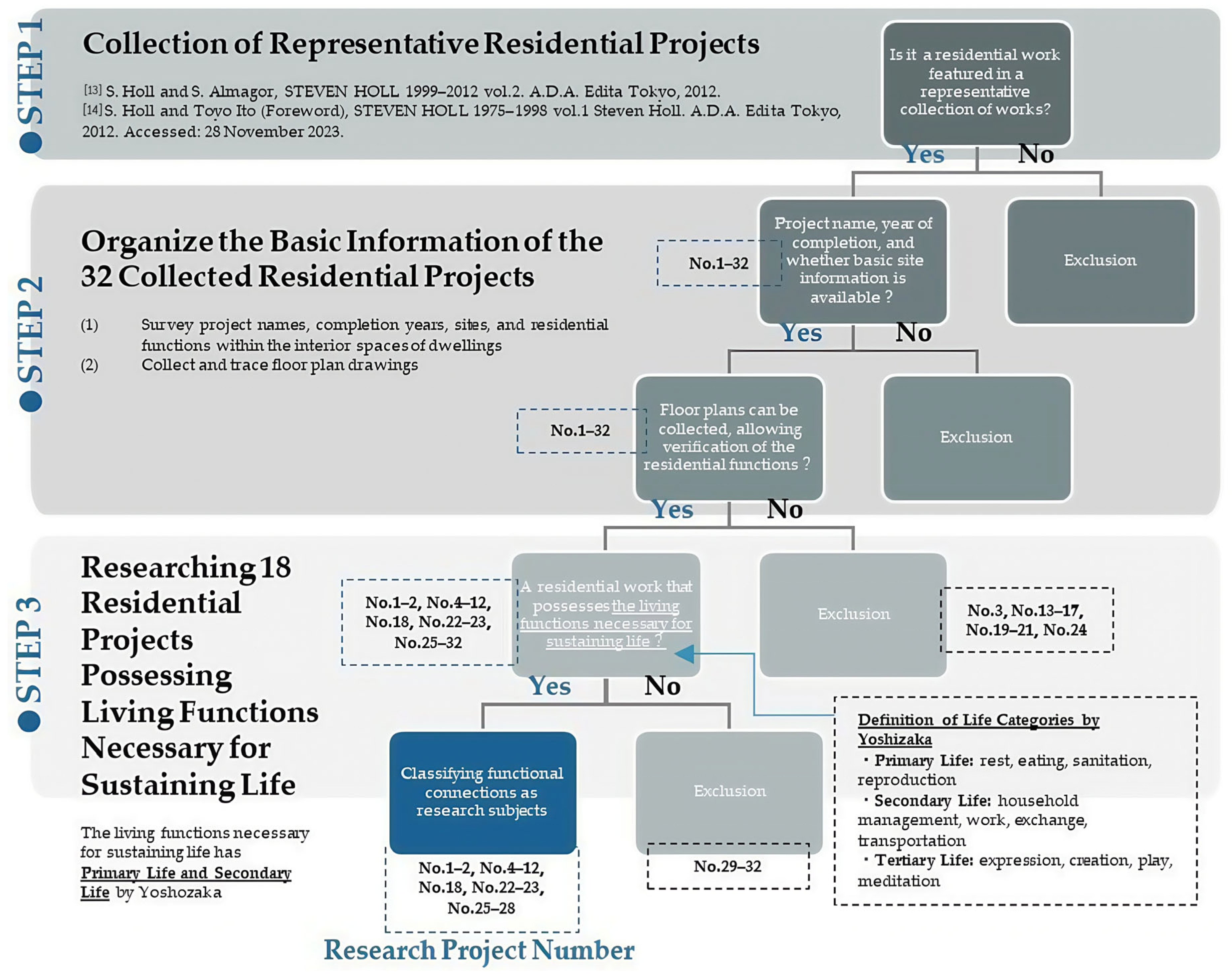

Figure 3 shows the flow for selecting research subjects. The research examines 18 residential projects selected from Holl’s design project books [

2,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21] and analyzes their compositional characteristics through floor plan classification and matrix analysis, with a particular focus on interior spatial functions. The research subjects were selected through a staged process as illustrated in

Figure 3. First, residential projects by Steven Holl were collected from representative volumes of his work, and only those clearly identified as residential works with verifiable basic information and available floor plan drawings were retained. Next, projects were evaluated based on whether they included essential living functions necessary for sustaining daily life. Through this filtering, 18 residential projects with both usable floor plans and identifiable interior living functions were finally selected as the research subjects for subsequent analysis. Steven Holl’s architectural concepts are developed through watercolor drawings, from which the master plans are generated [

22]. These plans embody the architect’s spatial intentions and values, especially regarding the organization of functions and the continuity of interior space. While architectural qualities may be understood through experiential, material, and representational aspects, this study concentrates on floor plans as a primary medium for examining functional organization and spatial relationships in residential architecture.

The analysis investigates whether typological compositional patterns can be identified in Holl’s residential projects by focusing on interior functions and room divisions. First, residential functions are identified based on first-floor plans. Second, spatial connections between rooms are classified according to their relationships to the entrance. Third, the spatial division between living rooms and private rooms is examined. These classifications form the basis for a matrix analysis, through which the characteristics of spatial continuity in Holl’s residence projects are systematically discussed. The analysis in this study focuses on first-floor plans, as they generally contain the primary residential functions and play a key role in organizing circulation, access, and the relationship between interior space and the exterior. In residential architecture, the first floor often serves as the spatial interface between communal and private domains, where functional arrangements and spatial continuity are most explicitly articulated. In this study, spaces such as living rooms are defined as “communal”, while the term “private” is restricted to individual rooms such as bedrooms. Matrix analysis is employed as an analytical framework to clarify relationships between multiple spatial elements using two analytical axes. By organizing spatial elements in a two-dimensional matrix, the presence and degree of interrelationships can be visually and systematically compared. This method enables the identification of typological tendencies and provides an effective tool for examining spatial continuity within complex residential compositions.

Matrix analysis is adopted in this study to systematically compare relationships among spatial elements and residential functions in floor plans. Because Steven Holl’s residential projects emphasize overlapping functions and spatial continuity rather than clear zoning, their compositional principles are difficult to capture through a single analytical axis or qualitative description. By employing two analytical axes, matrix analysis enables the cross-case examination of functional arrangements and spatial relationships, allowing shared compositional patterns to be identified objectively. This method, however, involves limitations, as the classification of functions and spatial connections depends partly on the researcher’s judgment, and the abstraction inherent in matrix analysis may simplify the specific contexts and design intentions of individual projects.

3. Results

3.1. Research Object Projects with Code for Type of Depiction and Facility Use

First, the basic functions of the residence were divided into the following categories: living room, kitchen, bathroom, exhibition for art projects, and others. The abbreviations of the room names in the survey are shown in

Table 1. In the classification of the functions of the residential type, 32 residences were surveyed. The results of the survey are shown in

Table 2. A circle (○) denotes the presence of the corresponding residential function. The coding rules were determined by categorizing functions essential to human life into three classes, based on Yoshizaka’s (1986) definition of life types [

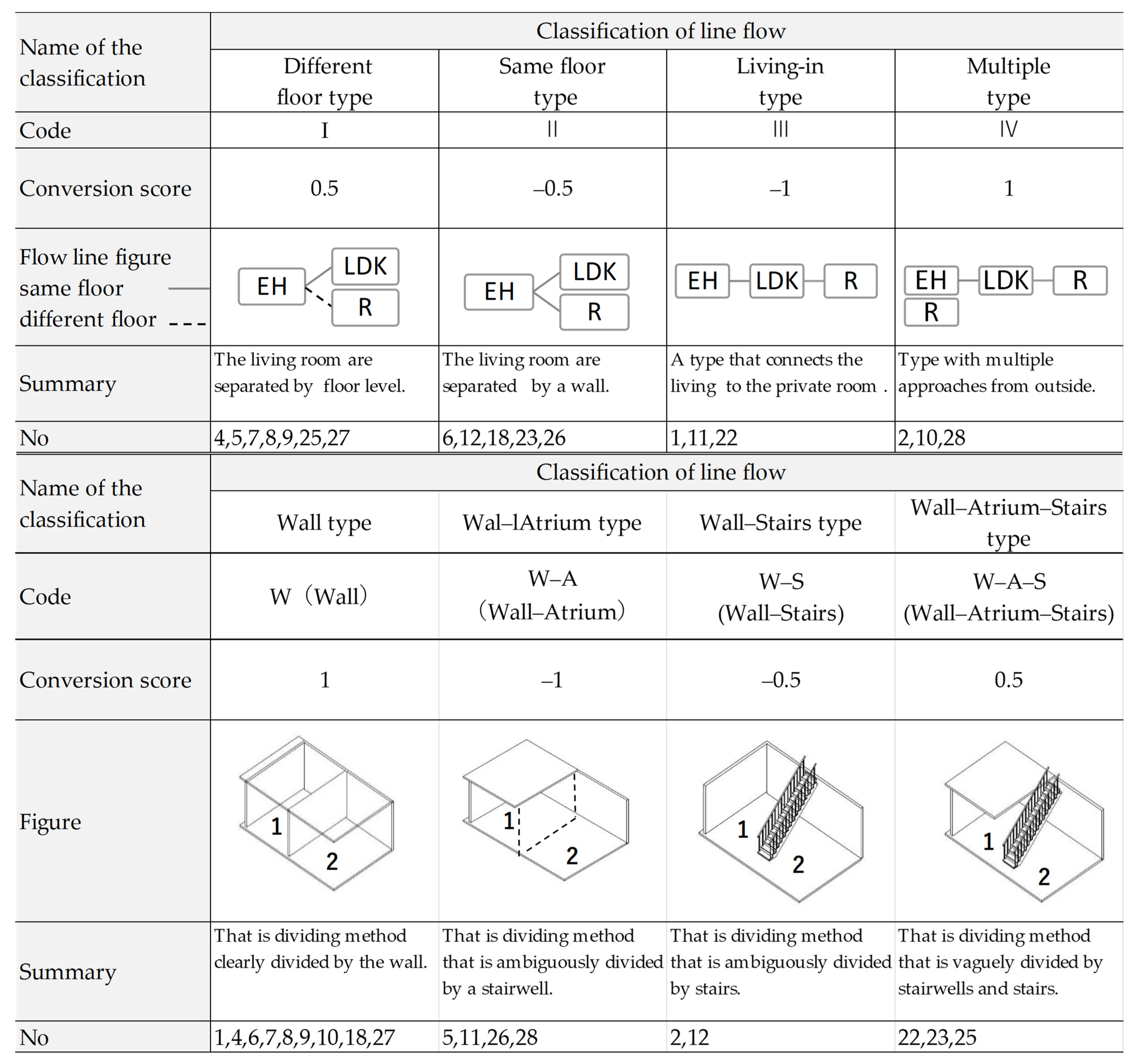

23].

This study focused first on room functions to investigate the connections between rooms. Access from the building’s exterior space is via the entrance hall. To discuss spatial connection and functionality starting from the entrance hall, the analysis was limited to the first-floor plan. This study analyzed only the first-floor plan and did not examine sectional or elevation drawings. The relationship with upper and lower floors, as well as the consideration of elevation and sectional drawings, remains a topic for future research. Among the projects presented as residential projects, vacation cabins lacking living room functions like kitchens or baths included projects numbered 29, 30, 31, and 32. When conducting the investigation into room connections, vacation cabins possessing only living room functions were excluded from the study. Additionally, projects numbered 3, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 19, 20, 21, and 24 were excluded because the resolution of the plans was too low to examine the connections between walls and rooms in detail, making it impossible to grasp the specifics of each room’s connection. Consequently, this study examines 18 projects to clarify the relationships regarding the connection of their rooms. Of the 18 works selected as research subjects, one dates from the 1970s, one from the 1980s, three from the 1990s, nine from the 2000s, and four from the 2010s.

3.2. Classification of Space Connection Between Entrance Hall and Living Room

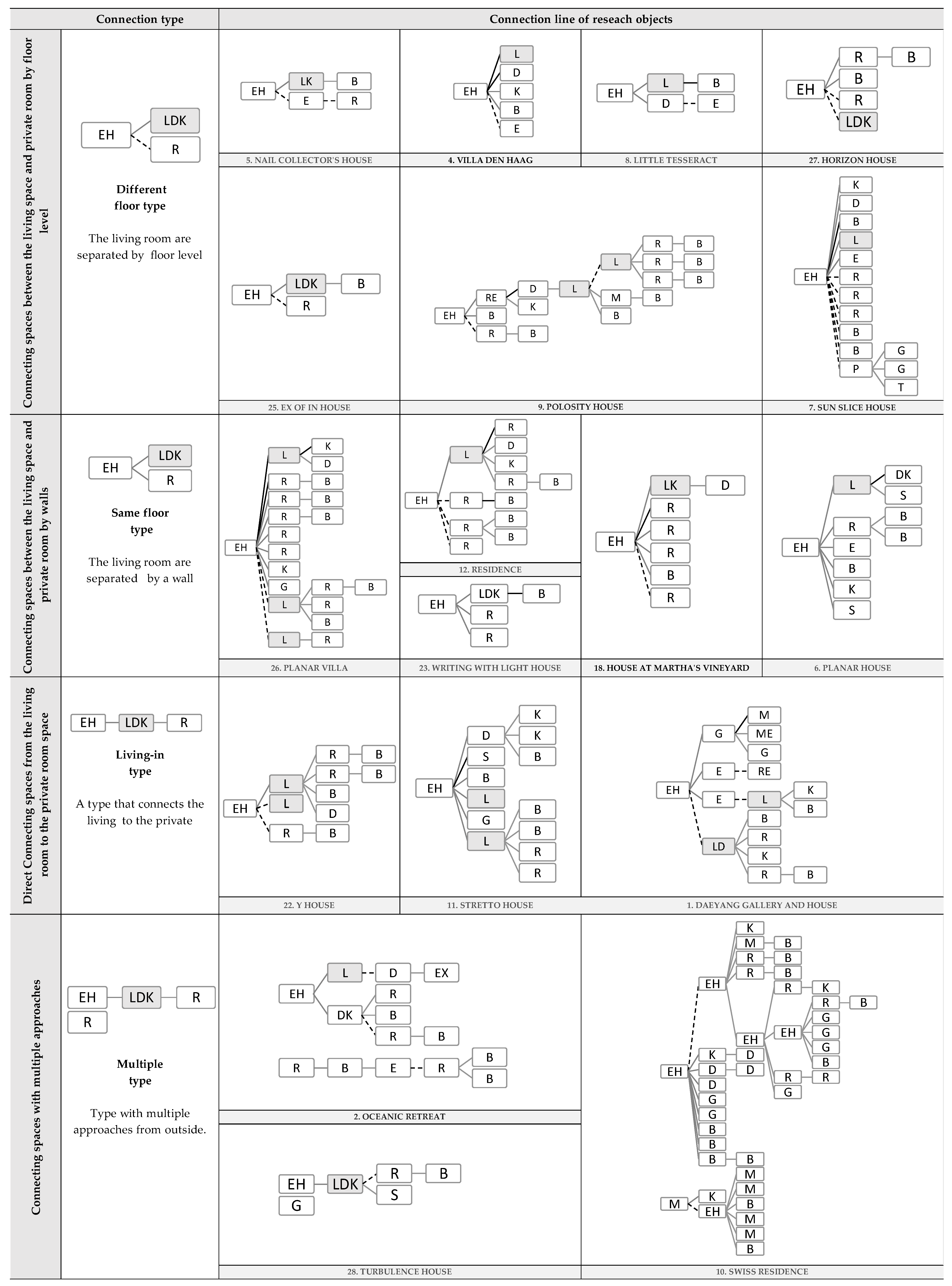

It investigated the connections between the entrance hall and each room in 18 residential projects.

Figure 4 shows the results of showing the connection between the entrance hall and the living room. It shows how the spaces are connected from the entrance hall to the rooms.

To investigate the connection of space from the entrance hall to each private room, residences with only a living room or residences without a detailed floor plan were excluded from the survey. In total, 18 residence projects were selected from 32 residences. To investigate the connections between spaces, this research conducted a survey of architectural drawings that were highly complete, excluding those in which the connections between spaces could not be identified on the drawings.

The dotted lines indicate that the stairs lead to the upper floors. There are four main types of connection graph: connecting spaces between the living room and private room by floor level; connecting spaces between the living room and private room by walls; direct connecting spaces, from the living room to the private room space; and connecting spaces, with multiple entryways.

Figure 5 shows the classification of the flow between the entrance hall and the living room. This study discusses the indexing of spatial flow lines and space division methods. The indexing of space flow lines includes private and communal, and the conversion point of the indexing was used as an evaluation criterion in the matrix analysis.

To quantify spatial partitioning characteristics, each room was numerically classified along a private–communal axis. Specifically, based on the circulation structure and spatial connection from the entrance hall to private rooms, spaces that exhibit a high degree of separation from other spaces and maintain their functional role as private rooms were defined as private (+1), whereas spaces with higher connection to other spaces were defined as the opposite, communal (−1).

In addition, an index representing the clarity of spatial boundaries was introduced, based on the presence or absence of physical partitions such as walls and ceilings. Private rooms with clearly defined boundaries were assigned a value of +1, while those with ambiguous boundaries were assigned −1.

The use of a symmetric +1/−1 scale allows the bipolar characteristics of each evaluation axis to be explicitly represented and facilitates comparison and integration among indices. This definition also enables the average score to be interpreted relative to zero, indicating the directional tendency of spatial characteristics.

The numerical values assigned to the communal–private axis (+1, −1, +0.5, and −0.5) were not empirically calibrated through behavioral measurements but were theoretically grounded and heuristically defined to operationalize the concept of a communal–private continuum in residential space. In architectural theory, communal and private spaces are commonly understood as forming a continuous spectrum rather than a binary opposition. Following this conceptual framework, a symmetric bipolar scale (+1/−1) was adopted to represent the two extremes of this continuum. Intermediate values (+0.5 and −0.5) were introduced to capture spatial configurations that simultaneously exhibit both communal and private characteristics. These values were derived through the aggregation of multiple spatial criteria—specifically, physical separation (e.g., floor or wall division) and circulation dependency—each evaluated on the same bipolar scale. When a spatial configuration satisfied one criterion strongly but only partially satisfied the other, the resulting score naturally converged toward an intermediate value. Thus, the intermediate scores were not arbitrarily assigned but emerged as a heuristic yet systematic representation of mixed spatial characteristics. This heuristic scaling approach enables comparative analysis across diverse residential layouts while maintaining theoretical consistency and analytical transparency.

As an index of the flow line between the living room and the private room, the living room was set as the communal space of the home as a family interaction space, and the private room was set as the private space, which is on the opposite side of the communal space. Those that are more adjacent to the living room and are often related to it in terms of flow line were set as communal, and those where the living room and private space are not so related were set as private.

First, the floor-dependent type is one in which the living room and the private space are divided according to the number of floors. By dividing the space three-dimensionally according to the number of floors, it is possible to clearly separate the living room from the private space, and to secure more private space for each individual. In terms of indexing, this is a private space, and the conversion point is 0.5 points.

Next is the same floor type. This is a common type of residence in which the living room and the private room are separated by a wall on the same floor. The index for this type is −0.5, which means that space is more communal. The third type, the living-in type, is also a common type of residence, in which the living room leads to private space.

According to the indexing, the conversion point is located at −1.0, indicating a spatial configuration in which circulation passes through the living room to reach private spaces. This arrangement promotes communication among family members and can therefore be regarded as a highly communal spatial type. It represents a distinctive residence type characterized by multiple approaches from the exterior. By contrast, according to the indexing, cases in which the conversion point is located at 1.0 represent the spatial type with the strongest degree of privacy.

3.3. Divided Configuration of Living Room and Other Room Spaces and Indexation Between Ambiguous and Clear Boundaries

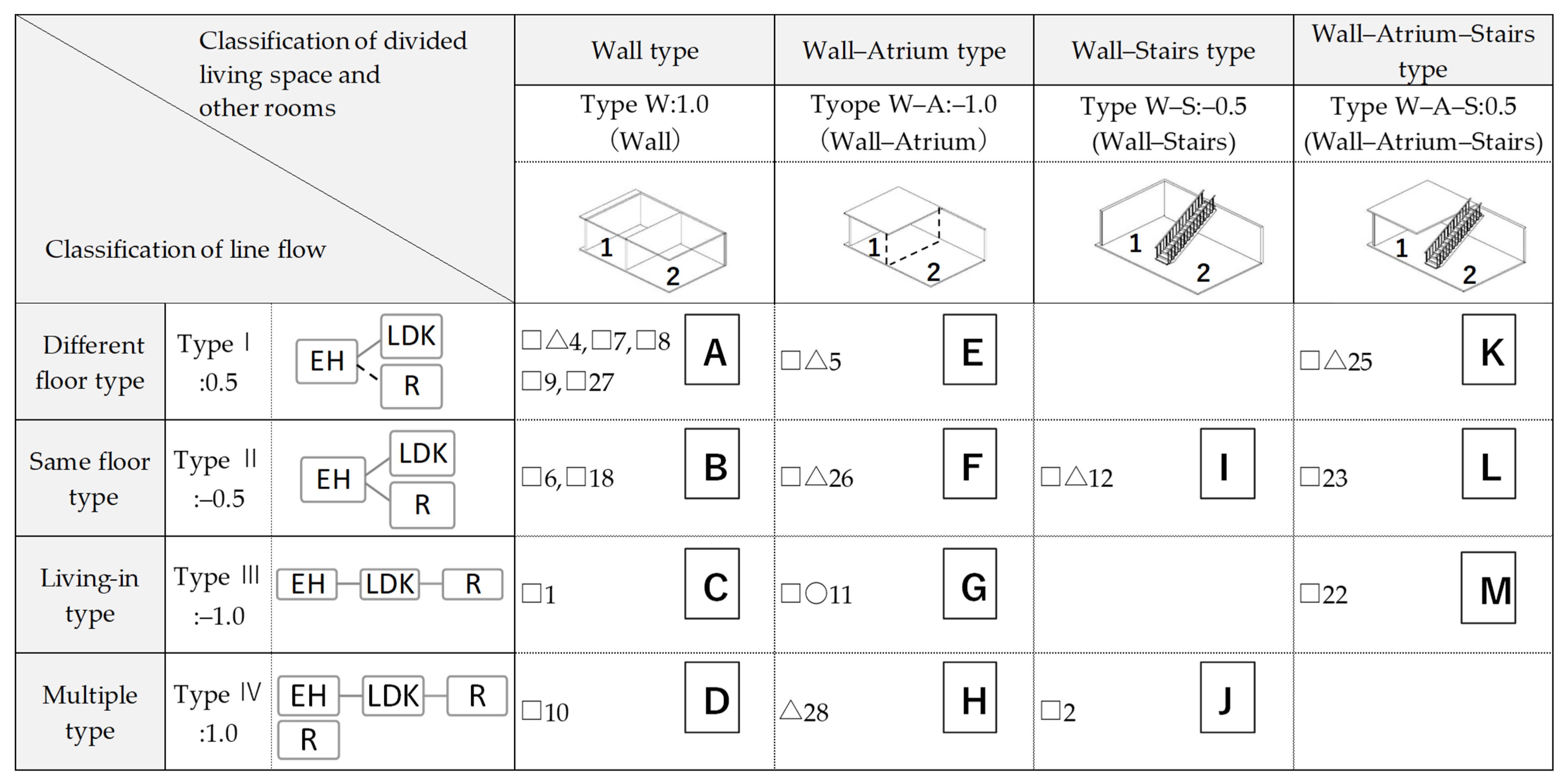

Next, this study analyzed the branch type using a conjunction graph in residential projects. First, this study typified how the living room and other room spaces are separated, and then analyzed the connection between the spaces using flow lines. Regarding the typology of how the living room and other room spaces are divided, the following types of spaces were identified as dividing spaces: spaces consisting of walls, spaces consisting of walls and an atrium, spaces consisting of stairs, and spaces consisting of stairs and an atrium.

Figure 5 shows the division configuration of the living room and other room spaces. The atrium means that the space is divided three-dimensionally by the difference in the height of the ceiling. The same applies to the combined staircase and atrium type, which means that the space is not only divided in plan, but also vertically between the living room and other rooms. To conduct matrix analysis in this chapter, criteria were set and scored for the categories that were classified. The following is a detailed explanation of the indexing of the way space is divided. Ambiguous boundaries are defined as spaces that are not physically partitioned but are assumed to be partitioned consciously, such as differences in ceiling heights, and clear boundaries are defined as spaces partitioned by walls or spaces that can be physically felt on a plane. Clear boundaries were scored as 1.0, ambiguous boundaries as −1.0, and the horizontal axis was set. The results were categorized into four types: wall type, wall–atrium type, wall–stairway type, and wall–atrium–stairway type.Vertical voids, such as atria, can strongly structure spatial perception and may therefore not always function as ambiguous boundaries. However, in this study, the atrium is treated as an ambiguous boundary because it does not involve a physical partition in plan; the division is perceived mainly through changes in ceiling height rather than through explicit walls or doors. Since the clarity of spatial boundaries can vary in degree, this classification allows for a range of conditions.

Next is the wall-atrium type, which is an ambiguous division of space by the atrium. Since the difference in the height direction of the ceiling gives an ambiguous sense of space division, we set the index number to −1.0 and determined it as an ambiguous division method. The wall-stair type is a method in which the space is ambiguously divided by stairs, and the index number was set to −0.5 as a space that is more ambiguous. This is because there are spaces separated by stairs due to the presence of stairs on the plane.

Finally, the wall–atrium–stairway type is a space that is divided by a stairwell and a staircase in a complex manner. The index number was set to 0.5, and the space was considered to have more than an obvious boundary. The wall–atrium–stairway type indeed contains both ambiguous elements (atrium) and clear elements (walls and stairs). In this study, the index value of 0.5 was assigned to this type to indicate that, while retaining some ambiguity due to the atrium, the boundary is closer to being clear than ambiguous. This score was derived by positioning this type between the clearly defined wall type (1.0) and the more ambiguous wall–atrium type (−1.0), thereby representing a hybrid boundary.

3.4. Matrix Analysis and Residential Features from the Planning Related to Connection

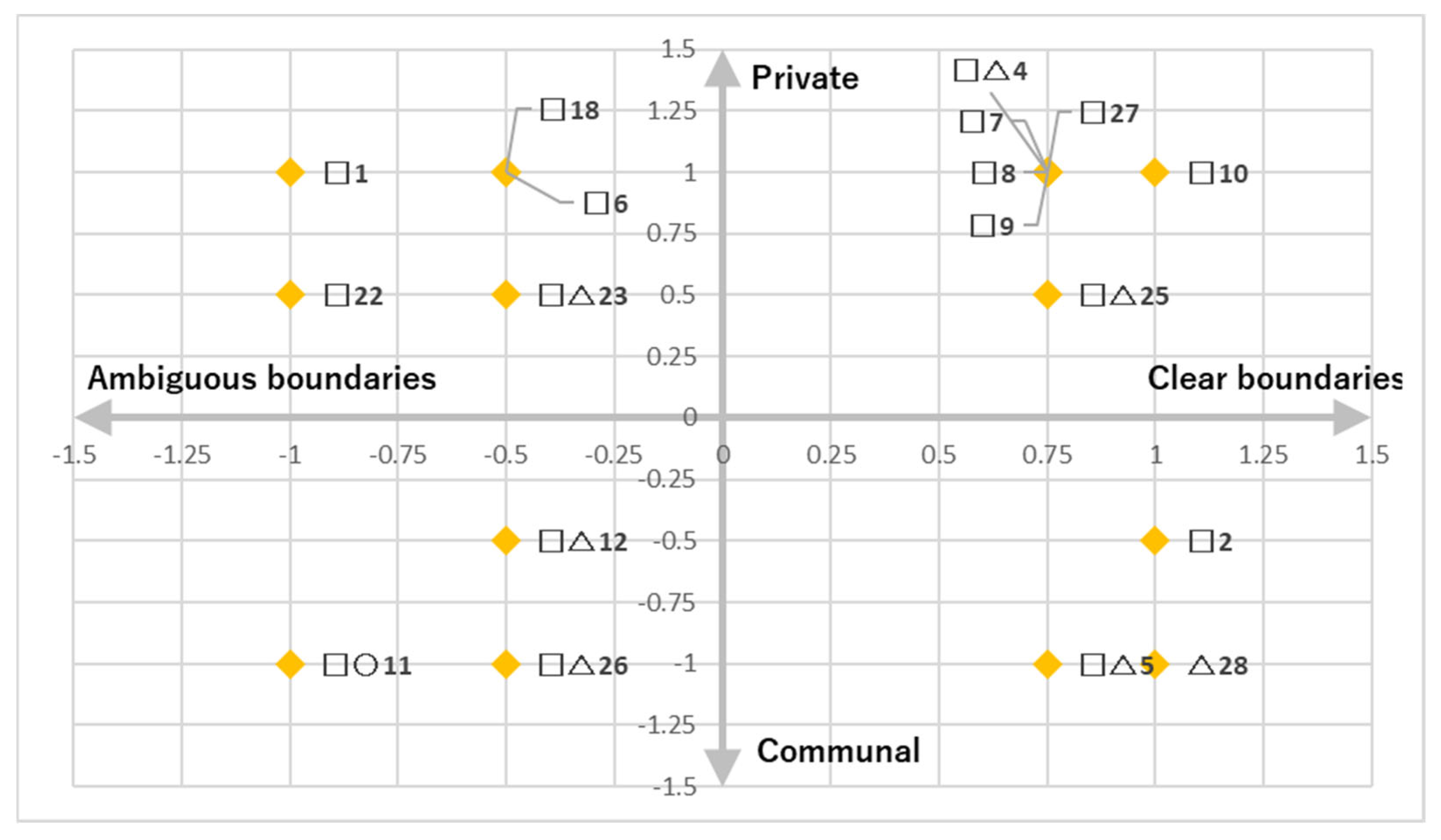

A matrix analysis is conducted by taking the bifurcation type using the connection graph and the division of the living room and other rooms as the two axes.

Figure 6 shows a matrix diagram of the four axes, with branching on the vertical axis and the division of the living room and other rooms on the horizontal axis. The “communal–private” axis indicates the functional character of a space, while the “clarity of boundaries” axis represents the compositional method, the physical manner of spatial division. Since these evaluation axes correspond to different dimensions, the analytical framework is justified. About the vertical axis, the private indicator for residential space was established based on the degree to which a space is isolated from other spaces, enabling it to function as a private room. Conversely, the communal indicator was defined as spaces that are easily connected to other areas, existing as open spaces that foster interaction with others.

And it provides additional information on the classification of roof shapes. Geometric shapes before the number of residential projects show the roof type. A square figure means a flat roof. A triangular figure means a sloping roof. A round figure means an arc-shaped roof. The meanings of the symbols are summarized as notes below

Figure 6. The roof form is limited to descriptive elements.

Figure 7 shows the results of the matrix analysis.

Figure 6 presents a classification framework that organizes spatial composition types based on the modes of division between living spaces and other rooms, such as differences in floor level and degrees of spatial continuity, as well as the use of architectural elements, including walls, atriums, and stairs. In contrast,

Figure 7 plots each residential case on a two-dimensional matrix derived from this classification, visually illustrating the relationship between the clarity of spatial boundaries and the functional character of spaces.

As a result, four cumulative trends were observed. On the axis of clear boundary and private, types A, D, and K corresponded. This group has the largest number of projects. The characteristics of these residences are that they emphasize private space with a clear method of space division. It can be inferred that Holl is conscious of clear boundaries, such as walls in private spaces, when designing residences. Secondly, there were three projects on the axis of clear boundary and communal, and this group tended to emphasize the communal space for family reunion, while certainly dividing the space by using a clear boundary. Thirdly, there were four projects on the axis of ambiguous boundary and private, and while dividing the space ambiguously, designed the space with an awareness of private space where individuals can spend their time as they wish.

Finally, there were three projects in the fourth category, ambiguous boundary and communal axis, and while softly dividing the space with ambiguous boundaries, the space was developed around a space for family reunion. The projects were evaluated and classified into four categories: private, communal, clear boundary, and ambiguous boundary.

However, the numerical predominance observed in this study is partly attributable to sampling constraints. Further research with an expanded sample size is required to examine whether additional or different tendencies may emerge.

In summary, this study found that there are four typological forms in terms of spatial use and division of the living room and private spaces. Based on the information provided by the floor plans, it was able to classify residences in terms of their spatial functions and flow lines. This study discovered the characteristics of residential projects from the perspective of function and flow lines, not simply the individuality of the form.

Figure 6.

Matrix diagram of the vertical axis and the horizontal axis.

Figure 6.

Matrix diagram of the vertical axis and the horizontal axis.

The symbol preceding the project number indicates the roof shape.

| □ | Flat roof |

| △ | Sloped roof |

| ○ | Curved roof |

Figure 7.

The results of the matrix analysis.

Figure 7.

The results of the matrix analysis.

4. Discussion

From the results, it can be inferred that Holl is conscious of obvious boundaries, such as walls in private spaces, when designing his residences. There were three projects on the axis of obvious boundaries and communal, and this group tended to emphasize communal spaces for family gatherings, while certainly dividing the space with said boundaries. There were four projects on the axis of ambiguous boundaries and private, and this group designed spaces with an awareness of private spaces where individuals can spend their time as they wish, all the while dividing the space. There were three projects on the axis of ambiguous boundaries and communal, and the space is subtly divided by ambiguous boundaries; meanwhile, the space is developed around the space for family reunion.

Holl indicates the following:

“A concept, whether a rationally explicit statement or a subjective demonstration, establishes an order, a field of inquiry, a limited principle.”

“If we consider the order (the idea) to be the outer perception and the phenomena (the experience) to be the inner perception, then in a physical construction, outer perception and inner perception are intertwined.”

Holl transforms order into an idea about architecture, which he defines as external perception. As a counterpart, he defines phenomena (experience) as internal perception. Since he describes order and phenomena as intertwined within a physical structure (a building), this study found that Holl’s architectural expression includes these order-related characteristics. In fact, the analysis of the floor plan of the residence showed that characteristics existed regarding the use and composition of the space.

This duality between order and phenomena in Holl’s approach parallels theoretical perspectives that emphasize the experiential and poetic qualities of space. In particular, Gaston Bachelard’s

The Poetics of Space (1957) conceptualizes space as a “lived place” imbued with memory, imagination, and symbolic resonance [

23]. In Holl’s residential projects, the manipulation of light, the placement of openings, and the articulation of spatial sequences translate his conceptual order into phenomenological experiences, allowing inhabitants to perceive temporal and seasonal changes in a deeply embodied manner.

Steven Holl’s residential architecture is characterized by its understanding of buildings not merely as physical structures or functional spaces, but as environments for the bodily and psychological experiences of their inhabitants. This design approach reflects clear theoretical influences from Gaston Bachelard’s

The Poetics of Space [

23] and Steen Eiler Rasmussen’s

Experiencing Architecture [

24], both of which provide a framework for understanding human spatial perception.

Bachelard conceives of space as a “lived place,” imbued with human memory, imagination, and psychological symbolism. He analyzes the house, nests, attics, and cellars as archetypal spaces that mediate the relationship between the individual and their inner world. This notion of poetic and symbolic space is evident in Holl’s residential projects, where variations in light and the placement of openings allow inhabitants to physically sense the passage of time and seasonal changes, rendering the space emotionally and symbolically resonant.

Similarly, Steen Eiler Rasmussen’s assertion that “architecture is experienced through the whole spectrum of the senses” (1959) resonates with Holl’s design principles [

24]. Circulation patterns, sightlines, ceiling heights, spatial compression and expansion, as well as material and lighting qualities, serve to integrate outer perception (order) with inner perception (experience), creating residences that are both rationally organized and sensorially engaging. Holl’s residences thus exemplify the intertwining of conceptual structure and lived experience, demonstrating how architecture can function simultaneously as an ordered system and a poetic, embodied environment.

Holl deliberately orchestrates circulation patterns, sightlines, ceiling heights, spatial compression and expansion, material textures, and qualities of light to foreground the inhabitant’s sensory experience. In doing so, the residence functions not merely as a living space but as a setting that actively engages and enriches the inhabitant’s perceptual and emotional experience.

However, spatial continuity identified through floor plan analysis cannot be directly equated with phenomenological experience. Rather, it should be understood as a structural condition that may support such experience, which requires further verification through three-dimensional, material, and experiential analysis.

As another type of residential architecture, collective housing is expected to exhibit a greater variety of spatial functions. Holl often designs collective housing and large-scale projects by integrating multiple programs. While such projects require spatial functions and connections that respond to urban context, circulation, and shared use, Holl is expected to flexibly adjust the degree of spatial openness and boundary ambiguity according to conceptual order, phenomenological experience, scale, and social context.

Nevertheless, since these studies focused only on the internal function, the use of space, and the way of dividing space, they have not yet been examined from a three-dimensional viewpoint. Although it was able to analyze the internal functions by using floor plans and was able to clarify one component that may have been indicated by Holl, there are still many points that remain unsatisfied. In the future, detailed analysis is needed to continue the research, focusing on the three-dimensional connection of the space using cross-sectional drawings and the interior materials in space.

The current matrix framework, while based on two-dimensional, could potentially be extended to incorporate three-dimensional and sensory parameters. For example, vertical spatial relationships, ceiling heights, and visual connections could be encoded as additional axes or layers in the matrix, while material qualities and light conditions could be represented as attributes of individual spatial elements. Such extensions would allow a systematic and comparative examination of how spatial continuity translates into embodied, perceptual experience.

5. Conclusions

This study clarifies the characteristics of the continuity of residential space in Steven Holl’s residential projects. This study focused on the composition of spatial connections in Holl’s residential projects. In order to show the continuity of each residential space in the residential projects in this study and to diagram the correspondence between each space, the uses of the spaces in the floor plans were classified, and the results were presented using matrix analysis. As a result, residential projects can be classified into four categories in terms of continuity of living room, indicating that residential projects have a unique form of expression.

Taken together, Holl’s residential projects can be interpreted as an integration of Bachelardian poetic-spatial sensibilities and Rasmussenian multi-sensory experiential principles, demonstrating how architecture can operate as a lived, perceptually and emotionally charged environment for everyday life.

This study focused on the functionality of residence as an order underpinning the phenomenological concept, clarifying a methodology for structural quantification.

This research found that clarifying the functional and spatial aspects of engineering expression in architectural design, which is highly regarded for its artistic qualities, will contribute to gaining insights into methodological approaches for future designs.

While this study focused on residential projects, future research will include other facilities and will focus on the relationship between the composition and ideas of architectural projects. In the future, it will also be conducting watercolor sketches and discursive expressions, focusing on the relationship between Holl’s ideas and drawing expressions. Also, it will be conducting research on design drawings. As part of our research on elevation drawings, we will focus particularly on the shape of windows. The design philosophy is influenced by phenomenology, and concepts are expressed using light and color, including the use of window design as a means of expressing naturally lit spaces.

Moreover, this study provides insights into bridging Holl’s phenomenological design philosophy with a more quantitative understanding of space. By applying matrix analysis to the floor plans of Holl’s residential projects, a novel methodological approach for architectural design research has been established, enabling the systematic evaluation of spatial functions and their continuity. This approach not only contributes to the analysis of Holl’s residence but also offers a frame for examining architectural expression in other projects where experiential and conceptual aspects are intertwined.