Abstract

This study examines how connectionist AI reshapes architectural rationality, focusing on the under-theorised epistemic implications of generative technologies. It positions latent space as the convergent medium of representation, cognition, and computation to investigate how learning-based models reorganise architectural reasoning. Employing a qualitative hermeneutic methodology suited to interpreting epistemic transformation, and analysing four emblematic cases, the study identified a tripartite shift: representation moves from symbolic abstraction to probabilistic, feature-based latent descriptions; cognition evolves from individual, rule-defined schemas to collective, data-inferred structures; and computation reorients from deterministic procedures to stochastic generative exploration. In this framework, type and style emerge not as fixed classifications but as continuous distributions of similarity, redefining the designer’s role from originator of form to curator of datasets, navigator of latent spaces, and interpreter of model outputs. Ultimately, the paper argues that connectionism introduces a distinct epistemic orientation grounded in correlation and probabilistic reasoning, thereby prompting critical reflection on the ethical, curatorial, and disciplinary responsibilities of AI-mediated design.

1. Introduction

Over the past decade, generative artificial intelligence has moved from experimental novelty to an increasingly influential force within architectural research and design practice [1,2,3,4,5]. Deep learning models, diffusion systems, and multimodal vision–language models are now routinely applied to spatial synthesis, typological generation, environmental simulation, and design exploration. Despite this rapid expansion, most architectural discourse on AI remains primarily focused on technical capability, efficiency, or formal novelty. What remains under-theorised, however, is the epistemological consequence of this shift: how the logic of architectural reasoning itself is being reorganised under connectionist AI.

This paper argues that the historical significance of generative AI in architecture does not lie merely in automation or speed, but in the emergence of a distinct connectionist mode of architectural rationality. Unlike the symbolic paradigm [6] that has governed architectural thought for centuries—based on predefined rules, typologies, and expert knowledge encoded in formal systems—connectionist systems learn directly from data. They do not deduce form from symbolic rules but infer it probabilistically through distributed patterns [5,7,8,9,10,11,12]. This transformation fundamentally alters how architectural knowledge is represented, how design cognition is structured, and how computation participates in creative reasoning.

This paper advances the claim that latent space constitutes the epistemic core of a new connectionist architectural rationality. Latent space is understood as a representational and cognitive environment in which architectural reasoning is reorganised [5,13,14,15,16]. Within this environment, form no longer emerges from predefined geometry or typological deduction, but through probabilistic navigation across learned feature distributions.

From this perspective, generative AI does not merely introduce new tools into architectural workflows; it reconfigures the conditions under which architectural intelligence operates. Design reasoning shifts from symbolic deduction to data-driven inference; typology transforms from fixed classification into probabilistic clustering; and computation evolves from deterministic optimisation toward stochastic exploration [5,17,18,19].

While recent discussions widely acknowledge the transformative impact of AI on architectural production, few studies have systematically theorised how these technologies reshape the underlying rationality of architectural thought [3,4,18,19,20,21,22,23]. Existing contributions often oscillate between technological enthusiasm and ethical anxiety, without articulating a clear epistemological framework for understanding what kind of reason generative AI introduces into architecture.

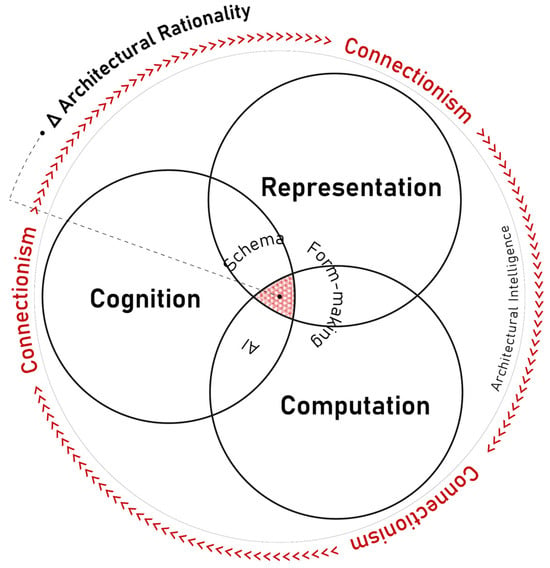

To address this gap, the paper proposes a tripartite analytical framework (Figure 1) through which connectionist architectural rationality can be examined:

Figure 1.

Tripartite analytical framework for examining connectionist architectural rationality.

- Representation—the shift from symbolic, Euclidean representation to probabilistic, feature-based latent description.

- Cognition—the transformation of design schemata from individual, static rule systems into collective, adaptive models learned from data.

- Computation—the reorientation from deterministic problem-solving toward stochastic generative exploration.

These three dimensions do not operate independently; rather, they intersect within latent space as a unified epistemic field in which perception, memory, inference, and form generation become inseparable.

Methodologically, the study adopts a hermeneutic approach, interpreting emblematic design cases as manifestations of epistemic transformation rather than as technical benchmarks. Through the analysis of four projects—Damascus House, Typal Fusion, Barrel Vault, and ArchiGAN—the paper examines how connectionist reasoning materialises across different architectural contexts and design scales. These cases are not presented as universal models but as theoretical articulations through which the logic of connectionist rationality becomes observable.

The contribution of this research is therefore not the proposal of a new design method but the formulation of a theoretical reframing: generative AI is interpreted not simply as a productive instrument, but as the carrier of a new epistemic orientation grounded in learning, probability, and collective inference. By situating latent space at the centre of architectural rationality, the paper seeks to clarify what it now means—for architecture—to represent, to think, and to compute.

The diagram formalises the paper’s theoretical framework by positioning representation, cognition, and computation as the three interdependent dimensions through which architectural rationality is reorganised under connectionist AI. The outer ring of directional arrows denotes the operative force of connectionism, indicating how learning-based processes reshape each dimension. The Δ marker identifies the locus of epistemic transformation—the point at which symbolic deduction gives way to probabilistic inference within latent space. This framework provides the basis for the methodological procedure and for the subsequent case analyses, where the tripartite structure is operationalised across different architectural contexts.

2. Theoretical Context: Symbolic vs. Connectionist Rationality

2.1. Symbolic Rationality in Architectural Thought

For much of its history, architectural rationality has been structured around what can be broadly described as symbolic rationality. This mode of reasoning assumes that architectural knowledge can be codified through explicit representations, geometric abstraction, and rule-based systems. From Vitruvius through Renaissance proportion theory to modern typology and computer-aided design, architecture has largely relied on symbols as stable mediators between concept, form, and construction [24,25].

In this paradigm, architectural intelligence is expert-defined and fixed. The designer operates through predefined typologies, compositional rules, and geometric schemas that precede the act of design. Quatremère de Quincy’s formulation of type as an abstract conceptual origin and Durand’s systematisation of form through combinatorial geometry exemplify this symbolic rationality [26,27,28,29]. Here, design becomes a deductive operation: form is generated by applying stable rules to known elements.

This symbolic lineage reached its twentieth-century computational expression in CAAD, shape grammars, and parametric systems. Shape grammar [30,31] formalised architectural generation as a syntactic process, while parametricism [32,33,34] embedded design logic within explicit variable relationships. Even when variation was introduced, it remained constrained by predefined symbolic structures. The system could only generate what had already been encoded within it.

From the perspective advanced here, symbolic rationality is characterised by three interrelated features:

- Predefinition—design knowledge must be explicitly formalised before generation begins.

- Fixity—rules and typologies remain stable across applications.

- Expert Authority—architectural intelligence resides primarily in the designer as an individual subject.

Within this configuration, computation functions as an instrument of execution rather than as an epistemic actor. The computer accelerates and visualises the consequences of symbolic rules, but it does not participate in the formation of architectural knowledge itself.

2.2. Limits of the Symbolic Paradigm

The limitations of symbolic rationality have long been acknowledged within both architectural theory and artificial intelligence. Critics of symbolic AI, most notably Dreyfus [35,36], argued that crucial dimensions of human intelligence—embodiment, intuition, context sensitivity—cannot be fully captured through explicit rules. Knowledge engineering confronted what became known as the knowledge bottleneck: the impossibility of exhaustively encoding the vast reservoir of tacit knowledge that underlies expert practice [37].

Architectural representation itself embodies this limitation. Orthographic projection, diagrams, and notational systems function as powerful tools of abstraction, but they operate through deliberate reduction. In compressing spatial reality into symbolic form, they exclude perceptual continuity, atmospheric nuance, and contextual ambiguity. Representation becomes a form of lossy compression—sacrificing sensory richness in favour of cognitive control [5].

Yet for centuries, this trade-off was accepted as the necessary condition of architectural rationality. The symbolic system guaranteed communicability, disciplinary stability, and professional authority. What changes with connectionism is not merely the technical means of representation but the very premise that architectural knowledge must be explicitly formalised in advance.

2.3. The Emergence of Connectionist Rationality

Connectionism introduces a fundamentally different model of intelligence—one based not on symbol manipulation but on learning through distributed patterns. Originating in cognitive science and artificial neural networks, connectionist systems do not store knowledge as explicit rules. Instead, they encode experience as weighted relations among artificial neurons, updated through exposure to data [7,38,39].

In architectural terms, this implies a shift from expert-defined knowledge to data-inferred knowledge; from fixed schemata to adaptive learning; and from deductive logic to probabilistic inference [5,40]. Where symbolic systems demand that architects define rules before computation begins, connectionist systems construct their own internal models through training.

This transformation did not emerge in isolation. Early architectural thought already contained proto-connectionist tendencies that challenged symbolic rationality without yet possessing learning-based computational mechanisms. Christopher Alexander’s diagrammatic thinking [41] reframed architectural form as a relational system of patterns rather than a syntactic composition of elements, privileging correlations over explicit rules. Batty subsequently formalised this relational approach by translating pattern-based descriptions into probabilistic and mathematical representations of spatial systems [42]. Through this formalisation, relational configurations became computable, enabling architectural patterns to be analysed and manipulated as statistical structures—an approach that established a methodological bridge between relational architectural thinking and later data-driven computation.

A more explicit epistemic rupture appeared with Nicholas Negroponte [22], who contrasted rule-based expert systems with learning machines capable of developing intelligence through experience. His distinction between embedding knowledge and enabling learning anticipated the core logic of connectionism: architectural intelligence as adaptive behaviour rather than symbolic problem-solving. However, at this stage, connectionism remained conceptually articulated but technically underdeveloped.

The term connectionism was explicitly introduced into architectural discourse by Richard Coyne [23]. He framed connectionist design as a mode of reasoning that operates without explicit symbolic rules or transparent causal accounts, foregrounding implicit knowledge, pattern recognition, and learning as legitimate foundations for design cognition. While Coyne’s contribution was primarily theoretical and lacked a corresponding generative or computational framework, it clarified connectionism as an epistemic position rather than a technical method.

The first systematic theoretical consolidation of connectionist rationality in architecture was provided by Mahalingam [19], who framed connectionism not as a tool but as an alternative paradigm of architectural reasoning. Mahalingam explicitly linked neural learning, schema construction, and architectural cognition, arguing that architectural knowledge could emerge from distributed, subsymbolic processes rather than from predefined representational systems. This marked a decisive transition from speculative critiques of symbolism to a coherent theory of learning-based architectural rationality.

Despite these conceptual advances, connectionist design remained marginal until the mid-2010s, when deep learning fundamentally altered the technical conditions of architectural computation. Breakthroughs in convolutional neural networks and neural style transfer [43,44] enabled high-dimensional feature learning directly from visual and spatial data, making subsymbolic architectural representation operational rather than theoretical. Subsequent architectural research by Chaillou, Bolojan, del Campo, Koh and others extended these methods into generative design workflows [1,2,13,40,45,46].

Taken together, this trajectory establishes connectionism not as a stylistic or technical trend, but as a distinct mode of architectural rationality—one in which design intelligence is reorganised around learning, inference, and statistical correlation rather than symbolic rule application.

2.4. Latent Space as the Core Epistemic Medium

The concept that stabilises this transformation is latent space. In deep learning, latent space refers to a high-dimensional vector field in which features extracted from data are compressed and reorganised [47,48,49].

Within this space, each point encodes a probabilistic description of form, spatial layout, texture, or typological configuration. Crucially, each point in latent space—each latent code—can be decoded back into a concrete architectural data instance through a trained generative model. Where the input data consist of architectural façade images, for example, the decoded output likewise takes the form of a new façade image; where the input is spatial layout data, the output corresponds to a newly synthesised spatial configuration. Latent space thus operates not only as an abstract representational domain, but as a bidirectional interface between architectural data and generative computation [5,13,14,16].

From the standpoint of architectural theory, latent space performs a role traditionally occupied by geometry and typology—but in a radically different manner. Classical geometry defines space through coordinates; latent space defines it through correlations. Classical typology classifies buildings into discrete categories; latent space organises them into continuous distributions of similarity. Variation arises not through rule-based recombination but through smooth interpolation across probability fields.

Latent space therefore constitutes the epistemic medium through which connectionist architectural rationality operates. Within this medium, architectural knowledge is no longer deduced from symbolic rules but inferred from relational patterns embedded in data. Latent space becomes simultaneously:

- a representational medium (encoding form as probability rather than geometry),

- a cognitive environment (organising collective schemata),

- a computational field (within which stochastic exploration unfolds).

This integrated understanding of latent space is operationalised more explicitly in Section 4 through the proposed analytical framework.

2.5. From Fixed Typology to Probabilistic Type

One of the most profound consequences of connectionist rationality concerns the architectural concept of type. In the symbolic tradition, type is defined through prior abstraction: buildings are classified according to stable morphological rules. In the connectionist paradigm, type emerges from statistical clustering across datasets. It is not predefined but inferred.

Type thus becomes probabilistic rather than categorical. It denotes a region of higher density within latent space rather than a fixed classification. Hybridisation, ambiguity, and typological drift are not exceptions but normal conditions of this new rationality. Architectural form is no longer evaluated by correspondence to ideal models but by its position within dynamic distributions of similarity.

This reconceptualisation of type provides a crucial link between connectionist rationality and architectural authorship. When type is not authored through symbolic definition but learned from data, authorship itself is transformed. The architect no longer legislates formal rules but curates datasets, selects training regimes, and frames the conditions under which typological patterns are inferred.

Design authority therefore shifts from direct formal control to epistemic governance. Architectural authorship is exercised not through the specification of form, but through decisions about what data are included, excluded, or weighted—decisions that shape the structure of latent space and, consequently, the range of forms the system can produce.

In this sense, probabilistic type functions as the architectural manifestation of connectionist rationality: a mode of design in which form, knowledge, and authorship are co-produced through learning rather than prescribed through rules.

2.6. Summary: From Symbolic Control to Connectionist Inference

The contrast between symbolic and connectionist rationality can therefore be synthesised across several epistemic dimensions, as summarised in Table 1:

Table 1.

Comparison between Symbolic and Connectionist Rationality.

Rather than substituting one technical apparatus for another, the transition reorganises the very conditions under which architectural knowledge, reasoning, and form generation become intelligible. If symbolic rationality sought clarity through reduction and control, connectionist rationality instead operates through uncertainty, variation, and collective inference as the new conditions of architectural reason.

These conditions fundamentally reorient how architectural intelligence is interpreted in the analyses that follow.

3. Methodology

This study adopted a qualitative, hermeneutic research methodology to examine how connectionist artificial intelligence reconfigures architectural rationality. Rather than evaluating algorithmic performance or technical efficiency, the research focused on the epistemic transformation of architectural reasoning—specifically how representation, cognition, and computation are reorganised under connectionist conditions. The central research question guiding the study is:

How does connectionist AI, through latent-space learning and probabilistic inference, reconfigure architectural rationality across the domains of representation, cognition, and computation?

Hermeneutics is adopted because the object of analysis is not empirical optimisation but the interpretive transformation of architectural knowledge systems. The methodology treats generative AI models and their architectural applications as cultural–technical artefacts through which shifts in rationality become legible. This aligns with the design-research tradition in which epistemic change is examined through reflective interpretation rather than experimental verification.

3.1. Analytical Procedure

Building on the tripartite framework introduced in Section 1, the interpretive procedure follows three sequential operations.

- Theoretical delimitationOn the basis of Section 2, symbolic and connectionist rationality are defined as two distinct epistemic regimes. From this conceptual contrast, three analytical dimensions are extracted: representation, cognition, and computation. These dimensions function as the primary criteria for case interpretation.

- Case-based interpretive mappingEach case is examined through a consistent analytical lens:data → latent space → output.This allows the study to trace how architectural information is encoded, transformed, and generated within each project. Observations are not treated as empirical proof but as epistemic indicators—for example, recurrent patterns of probabilistic variation—that demonstrate how connectionist reasoning operates in architectural contexts.

- Cross-case synthesisThe final step compares patterns across all cases to identify recurring epistemic shifts—such as the emergence of collective schemata, probabilistic typological clustering, and stochastic generative exploration—while also registering divergences and limitations.

This three-step procedure ensures that hermeneutic interpretation is systematic rather than impressionistic, directly addressing the reviewer’s concern that the original methodology was overly philosophical and insufficiently defined.

3.2. Case Selection and Justification

Four cases were selected: Damascus House, Typal Fusion, Barrel Vault, and ArchiGAN. The criteria for selection are not stylistic similarity but epistemic diversity. Each case foregrounds a distinct dimension of the proposed framework:

- Damascus House examines how collective cultural memory and climatic intelligence are learned and translated through image-based training.

- Typal Fusion demonstrates how architectural type and style emerge as probabilistic spectra through dataset mixing.

- Barrel Vault focuses on latent-space navigation as a mode of representational and cognitive exploration.

- ArchiGAN foregrounds computation as generative variation rather than optimisation.

Together, these cases span different scales (house, urban facility, immersive installation, generative system), data regimes (historical typologies, infrastructural hybrids, archival imagery), and computational setups (Pix2Pix, StyleGAN2, chained GANs). This range allows the study to examine connectionist rationality as a general epistemic condition rather than a project-specific technique.

4. Analytical Framework

The analytical framework of this study characterises connectionist architectural rationality as a tripartite transformation across representation, cognition, and computation. These three dimensions do not operate as separate analytical categories but as interdependent processes that converge within latent space as a unified epistemic field.

4.1. Representation: From Symbolic Geometry to Probabilistic Latent Description

In symbolic rationality, representation functions through Euclidean geometry, orthographic projection, and diagrammatic abstraction. These systems depend on predefined symbols and stable encoding conventions. Under connectionist conditions, representation is reorganised around feature-based latent description. Architectural images and spatial data are no longer interpreted as symbolic elements (walls, windows, axes) but as probabilistic feature distributions learned through neural networks. Latent space therefore becomes a representational medium in which architectural similarity is measured statistically rather than geometrically [5,50].

This shift introduces a new representational metric: semantic proximity replaces geometric distance. Variations arise not by rule-based recombination but through interpolation across learned feature fields. Representation thus becomes exploratory rather than declarative.

4.2. Cognition: From Individual Rules to Collective, Adaptive Schemata

In the symbolic paradigm, architectural cognition is anchored in the individual expert. Design knowledge is encoded as explicit rules, typologies, and compositional schemas that remain stable across projects. Connectionist cognition, in contrast, is data-driven, adaptive, and collective. Cognitive schemata are not predefined but learned through large-scale datasets integrating multiple authors, cultures, and historical layers.

Architectural intelligence therefore migrates from the individual designer to a distributed cognitive structure embedded in training data and neural weights. Typology no longer functions as a fixed classificatory system but as a probabilistic cluster within latent space. Hybridisation, ambiguity, and typological drift become intrinsic rather than exceptional.

4.3. Computation: From Deterministic Optimisation to Stochastic Exploration

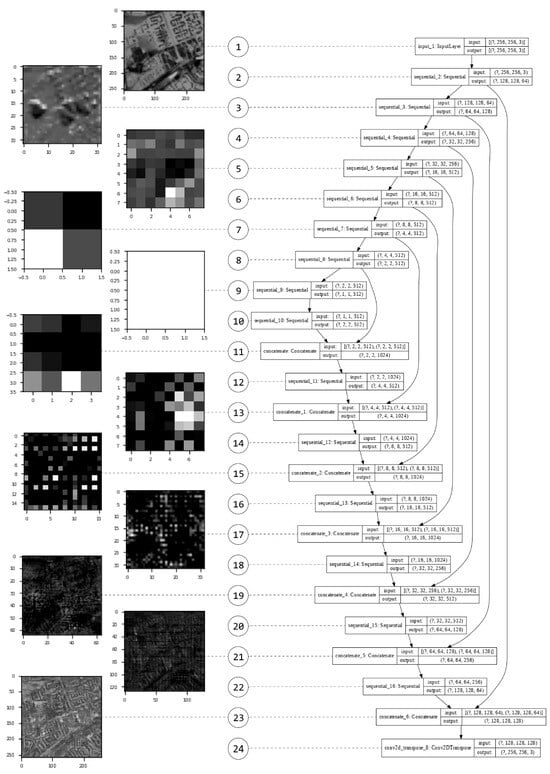

Symbolic computation seeks optimal solutions through explicit logical procedures. In contrast, connectionist computation operates through stochastic inference. Generative outcomes are driven by probabilistic sampling [51,52], compression–decompression, and random initial conditions (Figure 2). Rather than solving predefined problems, connectionist systems specialise in producing variation.

Figure 2.

Sub-symbolic feature fields underlying generative inference.

This reorients the goal of architectural computation. Instead of performance optimisation or singular solution-finding, computation becomes an exploratory engine generating families of plausible architectural configurations. Architectural agency correspondingly shifts from rule execution to curation, navigation, and interpretation of probabilistic design spaces.

The diagram shows how a convolutional neural network encodes architectural images into multi-level feature maps, progressively abstracting raw pixels into correlations of edges, textures and spatial gradients. This compression–decompression cycle constructs a latent description that serves as the basis for stochastic generative sampling. Crucially, the network does not recognise architecture through symbolic components (such as walls or windows), but through distributed feature fields whose probabilistic structure enables variation to emerge during generation. This directly supports the argument developed in Section 4.3: connectionist computation departs from deterministic optimisation by producing architectural possibilities through probabilistic navigation across these learned feature distributions.

4.4. Latent Space as the Unifying Epistemic Medium

Latent space constitutes the operative environment in which these three transformations intersect. It integrates:

- representational encoding (features),

- cognitive organisation (probabilistic schemata),

- and computational exploration (stochastic generation).

Rather than functioning as a neutral technical container, latent space operates as an epistemic infrastructure: a space in which architectural knowledge is learned, structured, and activated. Within this infrastructure, architectural reasoning no longer proceeds through symbolic deduction but through probabilistic inference and collective pattern recognition.

5. Case Analysis

This section applies the analytical framework and hermeneutic procedure set out in Section 3 and Section 4 to four emblematic projects: Damascus House, Typal Fusion, Barrel Vault, and ArchiGAN. Each case is examined through the consistent analytical lens of data → latent space → output, allowing the study to trace how architectural information is encoded, transformed, and generated. While all four cases activate the tripartite dimensions of representation, cognition, and computation, each foregrounds one dimension more explicitly. Together, they form a coherent evidential field through which the epistemic reconfiguration of architectural rationality under connectionist AI becomes demonstrable.

5.1. Damascus House: Collective Cognition and the Learning of Cultural–Environmental Intelligence

The Damascus House project [53] provides the clearest illustration of how connectionist systems reconfigure architectural cognition from individual rule-based reasoning into collective, data-driven learning. The project employed a Pix2Pix [54] image-to-image translation model trained on a curated dataset of Ottoman courtyard houses from Damascus [55]. The dataset encoded not only formal spatial arrangements but also climatic logics, lighting conditions, and cultural patterns of domestic organisation embedded within the historical typology.

At the representational level, architectural knowledge is no longer abstracted into diagrams or typological schemas prior to computation. Instead, spatial relationships are encoded as pixel-based correlations across the training dataset. The model does not “recognise” walls, courtyards, or thresholds as symbolic elements; rather, it learns probabilistic associations between visual features and spatial configurations. This marks a shift from declarative representation to latent, feature-based description.

At the cognitive level, the key transformation lies in how environmental and cultural intelligence are internalised. Traditional courtyard design knowledge would normally be accessed through historical treatises, climatic rules, and architectural precedents interpreted by the designer. In this project, in contrast, these forms of intelligence are inferred through training. The model constructs an internal schema that aggregates multiple historical examples into a distributed statistical structure. The resulting design proposals exhibit consistent characteristics—such as courtyard-centred organisation, shading gradients, and thermal buffering—without any explicit rule encoding.

Crucially, the evidence supporting this cognitive shift lies in the model’s capacity to generate spatial configurations that remain culturally legible and environmentally responsive even when applied to a new geographic context in Nazareth, Israel. This demonstrates that what is being transferred is not a formal copy of a typology but a learned relational schema. The architectural “knowledge” guiding the output no longer belongs to an individual expert but to the statistical structure of the trained model.

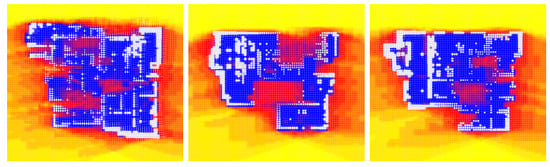

At the computational level, generation proceeds through probabilistic sampling rather than rule execution. Multiple valid design variants are produced from the same input condition, all satisfying the learned relationships without converging on a single optimal solution (Figure 3). This reinforces the argument that computation in a connectionist regime is oriented toward exploration rather than optimisation.

Figure 3.

Learned relational schema in the Damascus House project. The colour map represents a solar radiation simulation heatmap, where warmer colours indicate higher solar exposure and cooler (blue) colours indicate lower exposure or shaded conditions.

The Damascus House case thus provides concrete evidence for the transformation of architectural cognition into a collective, adaptive, and probabilistic system. Claims regarding “collective memory” in this context can therefore be interpreted not as a literal transposition of Rossi’s urban theory [56] into digital form, but as a computational analogue: persistence of spatial intelligence is achieved through data density and statistical learning rather than material permanence.

The diagrams show how the model generates alternative courtyard-house configurations by internalising relationships between spatial form, cultural dwelling patterns, and environmental performance. The heatmaps visualise the simulated thermal radiation associated with each proposal, revealing how the model adjusts courtyard depth, shading gradients, and enclosure to modulate environmental behaviour while retaining culturally legible spatial organisation. The highlighted correspondences (in red) indicate relational features the model reconstructs across outputs, demonstrating that the generative process draws on a learned schema rather than reproducing fixed typological rules. The emergence of multiple viable configurations reflects the exploratory and non-deterministic nature of connectionist inference, showing how the model proposes a range of culturally coherent and environmentally responsive possibilities.

5.2. Typal Fusion: Probabilistic Typology and the Reorganisation of Representational Logic

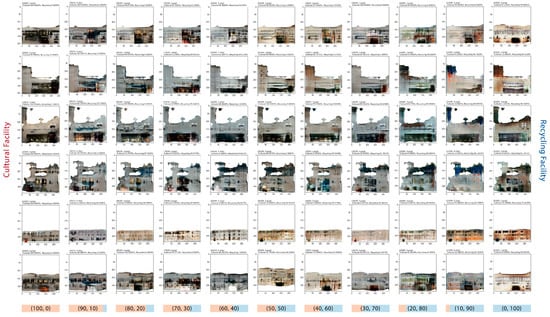

While Damascus House foregrounds cognitive transformation, the Typal Fusion project [57] most directly demonstrates the transformation of representation and typology under connectionist conditions. The project explored the hybridisation of two programmatically and formally distinct building categories—cultural facilities and recycling infrastructure—through controlled dataset mixing in a Pix2Pix training regime.

The dataset was systematically organised into eleven training subsets, in which cultural and recycling façades were mixed in 10% increments from 100:0 (pure cultural) to 0:100 (pure recycling). In this project, the principal representational decision is therefore enacted at the level of the dataset: typal emphasis is modulated by adjusting the statistical composition of the training images rather than by editing forms directly. Whereas symbolic typology would construct hybrids through compositional collage or explicit formal analogy, here hybridisation emerges from the model’s learning of latent feature distributions across these mixed subsets, suggesting that typological blending arises from the encoding of feature statistics during training, rather than through predetermined geometric recombination.

At the representational level, the key evidential shift lies in the nature of similarity. In symbolic systems, typology depends on categorical membership: a building either belongs to a type or it does not. In Typal Fusion, typological identity emerges as a gradient of probability. Intermediate data ratios generate outputs that are neither recognisably cultural nor purely infrastructural but occupy ambiguous hybrid states (Figure 4). These outcomes indicate that typological organisation operates as a continuous field of similarity encoded in the model’s learned feature distributions rather than as a fixed classificatory system.

Figure 4.

Typal spectrum generated in the Typal Fusion project.

At the cognitive level, typological knowledge no longer functions as a priori schema but as an emergent distribution learned from sample density. The model is not instructed on what constitutes a “cultural building” or “recycling facility”; it infers these categories statistically. The conceptual authority of type thus shifts from being defined a priori within architectural theory to being inferred from patterns internal to the training corpus.

At the computational level, the generative mechanism is explicitly exploratory. Variations arise not from the recombination of predefined formal parts but from the model’s sensitivity to changes in the statistical composition of the training data. Even small adjustments in dataset proportion produce qualitatively distinct outputs, indicating that generative difference is driven by probabilistic responsiveness rather than parametric control.

The evidential strength of Typal Fusion lies in its capacity to demonstrate typology as a probabilistic, continuously differentiable construct. This directly supports the paper’s central claim that latent space reorganises representation itself, replacing symbolic categories with graded distributions of similarity.

The sequence illustrates how typological organisation is reconfigured from categorical membership into probabilistic similarity under connectionist learning. Each column corresponds to a Pix2Pix model trained on a distinct data mixture—ranging from 100:0 cultural to 0:100 recycling images in 10% increments—revealing how feature distributions, rather than symbolic rules, structure typal identity. Clear categories emerge at the extremes, whereas mid-range ratios produce hybrid, indeterminate configurations that cannot be stably classified. This evidences that typology functions as a continuous field encoded through learned feature statistics, supporting the argument that connectionist representation replaces fixed taxonomies with graded distributions of similarity.

5.3. Barrel Vault: Latent Space as a Navigable Representational and Cognitive Field

The Barrel Vault project [58] foregrounds latent space not as an abstract computational container but as an actively navigable representational and cognitive environment. Using a generative model trained on a large corpus of urban imagery and archival spatial data, the project invited participants to traverse architectural possibilities through interactive latent walks (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Latent-space traversal in the Barrel Vault project.

The sequence records a participant’s continuous navigation through the model’s latent space, revealing how learned feature structures organise architectural similarity and difference. As the participant moves incrementally across latent coordinates, the vaulted form transforms smoothly yet unpredictably, expressing the probabilistic gradients encoded during training. The visual continuity between frames indicates that similarity is structured as a learned feature field, while the qualitative shifts demonstrate that variation arises from stochastic sensitivity rather than symbolic or parametric manipulation. This evidences that latent space functions as a cognitively navigable representational environment in which architectural possibilities emerge through exploration rather than rule execution.

At the representational level, the project demonstrates that architectural form is no longer depicted through static drawings or pre-defined parametric families. Instead, each position in latent space corresponds to a probabilistic reconstruction derived from learned features. Visual continuity across the latent walk evidences that architectural similarity is organised statistically rather than geometrically.

At the cognitive level, the project illustrates how architectural memory becomes operational within a learned feature field. The model does not store explicit historical references; instead, recurring urban morphologies, material textures, and spatial rhythms emerge as clusters within latent space. When users navigate this space, they are effectively traversing a learned cognitive map generated from aggregated visual culture.

The experiential interface of Barrel Vault transforms cognitive reasoning into a spatialised exploratory act. The designer or participant no longer selects from predefined options but navigates gradients of probability. This constitutes a fundamental departure from symbolic decision trees or parametric dependency graphs.

At the computational level, the generative process is inherently stochastic. Each step along a latent trajectory produces a new inferred configuration. Repeating the same trajectory produces similar but non-identical results. This evidences that variation is not noise but a structural property of computation under connectionist rationality.

The project thus provides strong empirical grounding for the argument that latent space functions as the epistemic medium in which representation, cognition, and computation intersect as a unified probabilistic field.

5.4. ArchiGAN: Computation as Generative Exploration Rather than Optimisation

The ArchiGAN project [40] most explicitly foregrounds the transformation of computation. Using a nested generative adversarial network trained on Baroque architectural plans, the system produces large populations of plan alternatives rather than converging on a single optimal solution.

At the representational level, plan geometry is encoded as learned feature distributions rather than symbolic diagrams. What is manipulated is not geometry per se but latent vectors that encode relationships among walls, voids, circulation, and symmetry.

At the cognitive level, architectural order is not imposed through rule sets but inferred from the statistical structure of historical data. The model reproduces Baroque-like spatial logic without explicit encoding of axes, proportions, or formal hierarchies.

At the computational level, the essential transformation lies in the goal of computation itself. Instead of optimisation, the system generates a field of possibilities. Hundreds of valid architectural solutions are produced, which are then organised through post hoc evaluation metrics. Architectural intelligence here lies not in solving a problem once, but in enabling rapid exploration across a wide solution space.

This evidences a decisive epistemic shift: computation becomes a machine for producing difference rather than a machine for validating correctness. Architectural agency correspondingly shifts toward curatorial selection and interpretive judgement.

5.5. Cross-Case Synthesis: Convergent Epistemic Shifts

Across the four cases, consistent epistemic transformations can be identified. First, architectural representation shifts from symbolic abstraction to probabilistic feature encoding. Second, architectural cognition shifts from individual expert reasoning to collective, data-driven learning. Third, architectural computation shifts from deterministic optimisation to stochastic exploration.

Despite differences in scale, data type, and technical implementation, all cases demonstrate that latent space functions as the operative epistemic infrastructure in which these transformations converge. Representation, cognition, and computation no longer operate as separable stages but as interdependent processes unfolding within a unified probabilistic field.

At the same time, the cases also reveal important limits. Learned schemata are inherently dependent on dataset composition, exposing architectural reasoning to data bias. Latent-space navigation lacks explicit causal transparency, complicating interpretability. Additionally, probabilistic generation, while expansive in formal diversity, does not by itself guarantee contextual, social, or environmental appropriateness. These limitations are examined further in the subsequent Discussion section.

6. Discussion

The findings presented in the preceding case analyses indicate that connectionist AI does not simply introduce new generative techniques, but reorganises foundational assumptions of architectural rationality. These epistemic shifts become most legible when read against longer traditions of typological reasoning and computational design. The discussion that follows therefore situates the observed transformations within ongoing debates on symbolic, parametric, and learning-based modes of architectural reasoning, while also addressing their conceptual and practical limits.

6.1. Connectionist Rationality and the Legacy of Typological Reason

The case analyses show that connectionist AI reorganises typology from a symbolic system of classification into a probabilistic field of similarity. This transformation directly engages, but does not simply negate, the typological tradition associated with Durand and Rossi.

In Durand’s rationalist project, typology functions as a deductive instrument: architecture is generated through the systematic recombination of predefined geometric and programmatic elements. Rationality is secured through formal clarity, repeatability, and methodological transparency. In contrast, the Typal Fusion and Damascus House cases show that under connectionist conditions, typology is no longer deduced from explicit compositional rules but inferred from statistical regularities embedded within datasets. Architectural form emerges not as an instantiation of abstract type but as a probabilistic reconstruction situated within a learned distribution.

Rossi’s theory of type as collective memory offers a closer point of contact. The persistence of form across time, in Rossi’s account, is anchored in the material endurance of urban artefacts. In the present cases, particularly Damascus House and Barrel Vault, persistence operates through data density rather than physical permanence. What is retained is no longer an artefact but a statistical trace. This constitutes a shift in the substrate of memory from the city to the dataset.

However, it is crucial to resist an uncritical equivalence between Rossi’s collective memory and data-driven learning. In connectionist systems, memory is not a shared lived experience, but a curated archive mediated by selection protocols, institutional access, and algorithmic filtering. The “collective” is therefore contingent and partial. While connectionist typology can simulate continuity, it also introduces new mechanisms of exclusion. What appears as a neutral distribution of features is always conditioned by what has been made available as data.

The discussion thus reframes typology under connectionist rationality as neither purely symbolic nor genuinely historical, but as probabilistic abstraction—a third epistemic condition that sits between geometric deduction and urban permanence.

6.2. From Shape Grammar and Parametricism to Latent-Space Generation

The results also require repositioning connectionist design in relation to earlier generations of computational architecture, particularly shape grammar and parametricism.

Shape grammar formalised architectural generation as symbolic computation. Design emerges through rule application, and the epistemic authority of the system derives from the explicitness of its syntax. Parametricism extended this logic through continuous variation, but it retained an underlying rule-based structure: relationships between parts remain predefined, even when their numerical values vary.

It is equally important to situate connectionist generation within a longer lineage of non-symbolic and emergent computational approaches in architecture. Evolutionary design, population-based models, and complex-systems thinking—exemplified by Frazer’s evolutionary architecture and DeLanda’s population logic—challenged deterministic and top-down design control by introducing emergence through iterative variation and selection. However, these approaches still rely on explicitly defined fitness criteria, parameter spaces, or rule systems that structure the search process in advance. This raises the question of whether connectionist models merely extend these non-symbolic paradigms, or whether they reorganise architectural rationality at a more fundamental epistemic level.

Against this backdrop, the four cases analysed here can be understood as concrete instantiations of a distribution-driven generative logic. In ArchiGAN, for example, the production of hundreds of valid plan configurations is not the result of varying a parametric model but of sampling a learned probability field. In Barrel Vault, spatial continuity is produced not through geometric constraints but through proximity within latent space.

This marks a fundamental displacement of control. In parametric systems, the designer prescribes the structure of the design space in advance. In connectionist systems, the structure of the space is learned. The designer no longer determines the space of possible solutions but curates the data from which this space is inferred. Agency thus shifts from formal authorship to epistemic governance.

At the same time, the findings indicate that connectionist computation does not abolish parametric logic so much as supersede it at a different epistemic level. Parametric models still operate locally within the generation and evaluation of outcomes, but the global structure of the design space is organised statistically rather than geometrically. This layered relationship complicates any simplistic narrative of technological succession.

6.3. Agency, Interpretation, and the Question of Architectural Authorship

Across all cases, architectural agency is redistributed rather than eliminated. The designer no longer occupies the position of sole originator of form, but nor is authorship displaced entirely onto the machine. Instead, agency becomes curatorial, navigational, and interpretive.

In Typal Fusion, authorship is exercised through dataset composition. In Barrel Vault, it is enacted through the selection of latent trajectories. In ArchiGAN, it lies in post-generative evaluation and filtering. These operations are not secondary; they define the epistemic boundaries of what the system can produce.

This redistribution of agency raises substantive theoretical questions. If design intelligence is partly delegated to statistical inference, what remains of architectural judgement? The cases suggest that judgement does not disappear but shifts upward in abstraction. Rather than judging isolated forms, designers evaluate distributions, tendencies, and fields of variation.

This also reframes debates around “algorithmic agency”. The results do not support a strong claim that machines become autonomous architectural agents. Instead, they indicate that agency is structurally distributed across human intention, data curation, and algorithmic inference. Claims of full algorithmic authorship therefore require significant qualification.

Similarly, philosophical notions such as embodiment and collective body can only be sustained at the level of metaphor. While the learning process aggregates traces of past human activity, it does not replicate lived perception.

Rather than supporting phenomenological accounts of embodiment, the cases examined here are more appropriately framed through post-cognitivist theories of distributed cognition and the extended mind, in which cognitive processes are understood as emerging across assemblages of humans, artefacts, and environments rather than residing within a single subject [59,60].

From this perspective, connectionist systems operate on representations of experience, not on experience itself. The cases therefore support a restrained interpretation in which embodiment remains a conceptual analogy rather than an ontological condition of machine cognition.

6.4. Epistemic Limits: Bias, Opacity, and the Risk of Visual Overgeneralisation

The findings also expose critical limitations that must temper any epistemic claims made for connectionist architectural rationality.

First, data bias is structurally embedded in all four cases. In Damascus House, the cultural logic transferred into the model is confined to the archival scope of the dataset. In Typal Fusion, typological hybridity is conditioned by the relative representation of program categories. What appears as neutral morphological emergence is in fact tightly coupled to curatorial decisions. Bias is not an anomaly but a constitutive feature of learning-based design.

Second, the opacity of neural networks limits interpretability. Although latent space provides a navigable representational environment, the causal mechanisms linking specific features to design outcomes remain largely inaccessible. This complicates architectural accountability. Designers can observe correlations but cannot always explain why particular spatial outcomes occur.

Third, the findings point to the limitations of visual intelligence as a proxy for architectural intelligence. All four cases operate primarily on image data. While this enables rich formal exploration, it risks overgeneralising from visual similarity to spatial, social, or environmental adequacy. Latent continuity does not guarantee structural feasibility, programmatic functionality, or urban viability.

Finally, the exploratory strength of generative variation also generates a cognitive risk. The abundance of plausible alternatives can obscure evaluative benchmarks. When variation becomes the dominant epistemic value, architectural criteria such as use, ethics, and material performance risk being subordinated to latent diversity.

These limits underscore that connectionist rationality is not a self-sufficient architectural epistemology. It requires external critical frameworks to regulate its operation.

6.5. Toward a Recalibrated Architectural Rationality

Taken together, the findings suggest that connectionist AI does not simply introduce a new toolset into architectural design, but recalibrates the internal structure of architectural rationality itself. Representation becomes probabilistic rather than symbolic. Cognition becomes collective rather than individual. Computation becomes exploratory rather than optimising.

Yet this recalibration is better understood as a reorientation within architectural reason, not its replacement. Symbolic and parametric systems remain operative, but their epistemic dominance is displaced. Architectural intelligence increasingly operates across layered regimes of representation, learning, and inference.

At the same time, the limitations identified above indicate that connectionist rationality remains structurally incomplete as a disciplinary foundation. Its strength lies in its capacity to reorganise variation and similarity at scale; its weakness lies in its dependence on data regimes, its opacity, and its reliance on visual proxies.

The discussion therefore supports a balanced conclusion: connectionist AI introduces a distinct epistemic orientation grounded in probability and learning, but this orientation must remain embedded within broader architectural frameworks of material reasoning, social responsibility, and critical interpretation.

7. Conclusions

This study set out to address a gap in current architectural discourse: while generative artificial intelligence has been widely examined in terms of technical capability and formal novelty, its epistemological implications for architectural rationality have remained under-theorised. The central research question asked how connectionist AI, operating through latent-space learning and probabilistic inference, reconfigures architectural reasoning across representation, cognition, and computation.

Through a hermeneutic analysis of four emblematic cases—Damascus House, Typal Fusion, Barrel Vault, and ArchiGAN—the study has shown that connectionist AI is better understood not as a technical extension of existing design practices, but as the carrier of a distinct epistemic orientation within architectural thought. At the representational level, architectural description shifts from symbolic and geometric abstraction to feature-based probabilistic encoding. At the cognitive level, design intelligence migrates from individual rule-based expertise to collective, data-driven learning. At the computational level, optimisation gives way to stochastic exploration, and generation proceeds through the navigation of probability fields rather than deterministic procedures.

These transformations do not imply the replacement of symbolic or parametric rationalities. Rather, they point to a recalibration of architectural rationality, in which symbolic rules, parametric relations, and connectionist inference coexist within layered epistemic regimes. What distinguishes the connectionist condition is not speed or automation, but the emergence of latent space as an operative epistemic medium in which architectural knowledge is learned, structured, and activated probabilistically.

By repositioning latent space as an epistemic infrastructure rather than a purely technical construct, this study contributes to architectural theory in two principal ways. First, it clarifies how typology, representation, and authorship are being reorganised under learning-based computation. Second, it reframes generative AI as a driver of epistemic transformation rather than as a neutral design tool. In doing so, it situates contemporary AI practices within a longer lineage of architectural rationality while identifying their specific discontinuities.

Several limitations of this research must be acknowledged. The analysis is based primarily on image-driven generative systems and therefore engages only indirectly with structural performance, material behaviour, and socio-political agency in architecture. The interpretive framework also depends on curated datasets and selected exemplars, which inevitably introduces forms of data bias. Finally, while the epistemic shifts identified here are conceptually robust, their translation into large-scale, real-world architectural production remains an open and unresolved question.

Despite these limitations, the findings indicate that connectionist AI marks a significant turning point in how architecture represents, reasons, and computes. The challenge ahead is not to celebrate or resist this shift in isolation, but to critically integrate probabilistic, data-driven reasoning within broader architectural frameworks of material responsibility, social judgement, and disciplinary accountability.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the findings of this study are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| CAAD | Computer-Aided Architectural Design |

| Chained GANs | A sequential pipeline of multiple GAN models (e.g., Pix2Pix networks) where each output becomes the input to the next (A → B → C …), used in the ArchiGAN project to produce multi-step generative transformations. |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| GAN | Generative Adversarial Network |

| Pix2Pix | A conditional GAN architecture used for image-to-image translation (e.g., domain A → domain B) |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| StyleGAN2 | A second-generation style-based GAN architecture enabling high-resolution, controllable image synthesis. |

| VAE | Variational Autoencoder |

References

- Chaillou, S. Artificial Intelligence and Architecture: From Research to Practice; Birkhäuser: Basel, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- del Campo, M.; Leach, N. Machine Hallucinations: Architecture and Artificial Intelligence; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Leach, N. Architecture in the Age of Artificial Intelligence; Bloomsbury: London, UK, 2021; p. 239. [Google Scholar]

- Carpo, M. Beyond Digital: Design and Automation at the End of Modernity; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, S.-Y. On the Architectural Rationality of Connectionist Design. Ph.D. Thesis, University College London, London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Haugeland, J. Artificial Intelligence: The Very Idea; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1989; p. 302. [Google Scholar]

- Rumelhart, D.E.; McClelland, J.L.; PDP Research Group. Explorations in the microstructure of cognition: Foundations. In Parallel Distributed Processing; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1986; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- McClelland, J.L.; Rumelhart, D.E.; Group, P.R. Explorations in the microstructure of cognition: Psychological and biological models. In Parallel Distributed Processing; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1987; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Smolensky, P. Connectionist AI, Symbolic AI, and the Brain. Artif. Intell. Rev. 1987, 1, 95–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picon, A. Digital Culture in Architecture: An Introduction for the Design Professions. In Digital Culture in Architecture; Birkhäuser: Basel, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Shavlik, J.W.; Mooney, R.J.; Towell, G.G. Symbolic and Neural Learning Algorithms: An Experimental Comparison. Mach. Learn. 1991, 6, 111–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, T.D. Symbolic and sub-symbolic representations in computational models of human cognition: What can be learned from biology? Theory Psychol. 2003, 13, 847–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolojan, D.; Yousif, S.; Vermisso, E. Latent Design Spaces: Interconnected Deep Learning Models for Expanding the Architectural Search Space. In Architecture and Design for Industry 4.0: Theory and Practice; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 201–223. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, S. Exploring in the Latent Space of Design: A Method of Plausible Building Facades Images Generation, Properties Control and Model Explanation Base on StyleGAN2. In Proceedings of the the International Conference on Computational Design and Robotic Fabrication, Shanghai, China, 3–4 July 2021; pp. 55–68. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Stouffs, R. From Exploration to Interpretation-Adopting Deep Representation Learning Models to Latent Space Interpretation of Architectural Design Alternatives. In Proceedings of the 26th International Conference ofthe Association for Computer-Aided Architectural Design Research in Asia (CAADRIA), Hong Kong, China, 29 March–1 April 2021; pp. 131–140. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.; Johanes, M.; Kim, F.C.; Doumpioti, C.; Holz, G.-C. On GANs, NLP and Architecture: Combining Human and Machine Intelligences for the Generation and Evaluation of Meaningful Designs. Technol. Archit. Des. 2021, 5, 207–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terzidis, K. Algorithmic Architecture, 1st hardcover ed.; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2016; p. 176. [Google Scholar]

- del Campo, M.; Manninger, S. Tectonics of the Latent Space. In Proceedings of the 44th Annual Conference for the Association for Computer Aided Design in Architecture (ACADIA 2024): Designing Change, Calgary, AB, Canada, 11–16 November 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Mahalingam, G. Representing Architectural Design Using a Connections-based Paradigm. In Proceedings of the Association for Computer Aided Design in Architecture (ACADIA 2003), Indianapolis, IN, USA, 24–27 October 2003; pp. 270–277. [Google Scholar]

- Carpo, M. The Second Digital Turn: Design Beyond Intelligence, Paperback ed.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA; London, UK, 2017; p. 240. [Google Scholar]

- Terzidis, K. Permutation Design: Buildings, Texts, and Contexts; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Negroponte, N. Soft Architecture Machines; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1976; p. 140. [Google Scholar]

- Coyne, R.D. Design reasoning without explanations. AI Mag. 1990, 11, 72–80. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, M.H. Vitruvius: The Ten Books on Architecture; CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform: Scotts Valley, CA, USA, 2016; p. 284. [Google Scholar]

- Carpo, M. The Alphabet and The Algorithm; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- De Quincy, Q. An Essay on the Nature, the End, and the Means of Imitation in the Fine Arts; Smith, Elder and Company: London, UK, 1837. [Google Scholar]

- Noble, J. The Architectural Typology of Antoine Chrysostome Quatremere de Quincy (1755–1849). Edinb. Archit. Res. 2000, 27, 145–159. [Google Scholar]

- de Quincy, Q.; Chrysostôme, A. Quatremère De Quincy’s Historical Dictionary of Architecture: The True, the Fictive and the Real, translated by Samir Younès, hardcover ed.; Papadakis Publisher: London, UK, 2000; p. 256. [Google Scholar]

- Durand, J.N.L. Partie Graphique des Cours D’architecture Faits a L’école Royale Polytechnique Depuis sa Réorganisation; Précédée d’un Sommaire des Lecons Relatives a ce Nouveau Travail; Chez L’auteur, a l’Ecole Royale Polytechnique et Chez Firmin Didot: Paris, France, 2014; p. 35. [Google Scholar]

- Stiny, G.; Gips, J. Shape Grammars and the Generative Specification of Painting and Sculpture. In Proceedings of the IFIP Congress (2), Ljubljana, Yugoslavia, 23–28 August 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, W.J. The Logic of Architecture: Design, Computation and Cognition, 6th printing ed.; MIT Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998; p. 308. [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher, P. Parametricism: A New Global Style for Architecture and Urban Design. Archit. Des. 2009, 79, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazer, J. Parametric Computation: History and Future. Archit. Des. 2016, 86, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, P. Parametricism 2.0: Gearing Up to Impact the Global Built Environment. Archit. Des. 2016, 86, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreyfus, H. What Computers Can’t Do: The Limits of Artificial Intelligence; Legare Street Press: Paris, Frence, 2022; p. 308. [Google Scholar]

- Dreyfus, H.L. What Computers Still Can’t Do: A Critique of Artificial Reason; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Feigenbaum, E.A. Knowledge Engineering: The Applied Side of Artificial Intelligence. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1980, 426, 91–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckner, C.; Garson, J. Connectionism. Available online: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/connectionism/ (accessed on 29 May 2020).

- Fodor, J.A.; Pylyshyn, Z.W. Connectionism and cognitive architecture: A critical analysis. Cognition 1988, 28, 3–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaillou, S. AI + Architecture: Towards a New Approach. Master’s Thesis, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, C. Notes on the Synthesis of Form, Paperback ed.; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1964; Volume 5, p. 224. [Google Scholar]

- Batty, M. A Theory of Markovian Design Machines. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 1974, 1, 125–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatys, L.A.; Ecker, A.S.; Bethge, M. Image Style Transfer using Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 2414–2423. [Google Scholar]

- Jing, Y.; Yang, Y.; Feng, Z.; Ye, J.; Yu, Y.; Song, M. Neural style transfer: A review. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 2019, 26, 3365–3385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolojan, D. Creative AI: Augmenting Design Potency. Archit. Des. 2022, 92, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, I. Architectural Plasticity: The Aesthetics of Neural Sampling. Archit. Des. 2022, 92, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingma, D.P.; Welling, M. Auto-encoding variational bayes. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1312.6114. [Google Scholar]

- Tipping, M.E.; Bishop, C.M. Probabilistic principal component analysis. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Stat. Methodol. 1999, 61, 611–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinton, G.E.; Salakhutdinov, R.R. Reducing the dimensionality of data with neural networks. Science 2006, 313, 504–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickl, A. Navigating CLIPedia: Architectonic instruments for querying and questing a latent encyclopedia. Front. Archit. Res. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, I. Discrete Sampling: There is No Object or Field … Just Statistical Digital Patterns. Archit. Des. 2019, 89, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, M. Artificial Intelligence: A Guide for Thinking Humans, 1st hardcover ed.; Pelican: London, UK, 2019; p. 448. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, S.-Y.; Valls, E.L.; Tabony, A.; Castillio, L.C. Damascus House: Exploring the connectionist embodiment of the Islamic environmental intelligence by design. In Proceedings of the 41st Education and Research in Computer Aided Architectural Design in Europe (eCAADe) Conference, Graz, Austria, 20–23 September 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Isola, P.; Zhu, J.-Y.; Zhou, T.; Efros, A.A. Image-to-Image Translation with conditional Adversarial Networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HA, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 1125–1134. [Google Scholar]

- Kibrit, Z. Damascus House: During the Ottoman Period, 1st ed.; Salhani Est.: Damascus, Syria, 2000; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, A. The Architecture of the City, American ed.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1982; p. 208. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, S.-Y. From Parametric Determinism to Emergent Fusion: Data-Curated Style Control in Connectionist Architecture; UCL (University College London): London, UK, 2025; Volume 23. [Google Scholar]

- Carranza, E.R.; Huang, S.-Y.; Besems, J.; Gao, W. (IN)VISIBLE CITIES: What Generative Algorithms Tell Us about Our Collective Memory Schema. In Proceedings of the 28th International Conference of the Association for Computer-Aided Architectural Design Research in Asia (CAADRIA), Ahmedabad, Inida, 18–24 March 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Hutchins, E. Cognition in the Wild; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, A.; Chalmers, D. The extended mind. Analysis 1998, 58, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).