Bridging Innovation and Governance: A UTAUT-Based Mixed-Method Study of 3D Concrete Printing Technology Acceptance in South Africa

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature

2.1. Technology Adoption in Construction

2.2. 3DCP Acceptance: Global and South African Perspectives

2.3. Institutional and Professional Factors Influencing Acceptance

2.4. Gaps and Conceptual Direction

2.5. Theoretical Framework

- Regulatory clarity: This refers to the degree to which construction professionals and regulators perceive 3DCP policies and codes to be clear and actionable.

- Policy maturity: The extent to which national policies have evolved to accommodate innovative construction technologies, including 3DCP.

- Infrastructure readiness: This is the availability of technological, material, and digital infrastructure to support 3DCP operations. The meaning of the primary constructs in the original UTAUT model, performance expectancy, effort expectancy, social influence, and facilitating conditions, in the context of 3DCP, are explained below.

- Performance expectancy: This refers to the belief that adopting 3DCP technology may help in enhancing job performance. It highlights the notion of a relative advantage of 3DCP technology over the traditional construction methods.

- Effort expectancy: This is the degree of complexity or ease associated with the use of 3DCP technology.

- Social influence: This is the degree to which an individual perceives how important it is that others feel or believe that 3DCP technology should be mainstreamed side-by-side with conventional construction technologies. It is the influence which a person, culture, belief, training, or practice has over others whom they consider important, concerning the use of a particular technology.

- Facilitating conditions: This is the degree to which an individual believes that the organizational and technical infrastructure and skills exist within the construction sector to support the use of 3DCP technology.

3. Materials and Methods

- Construction professionals, including architects, civil engineers, construction managers, project managers, contractors, and quantity surveyors.

- Regulatory bodies such as the South African Bureau of Standards, the National Home Builders Registration Council, the Construction Industry Development Board, and local municipal planning departments.

3.1. Data Collection Methods

3.2. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Hypothesis Testing Using Structural Equation Modeling

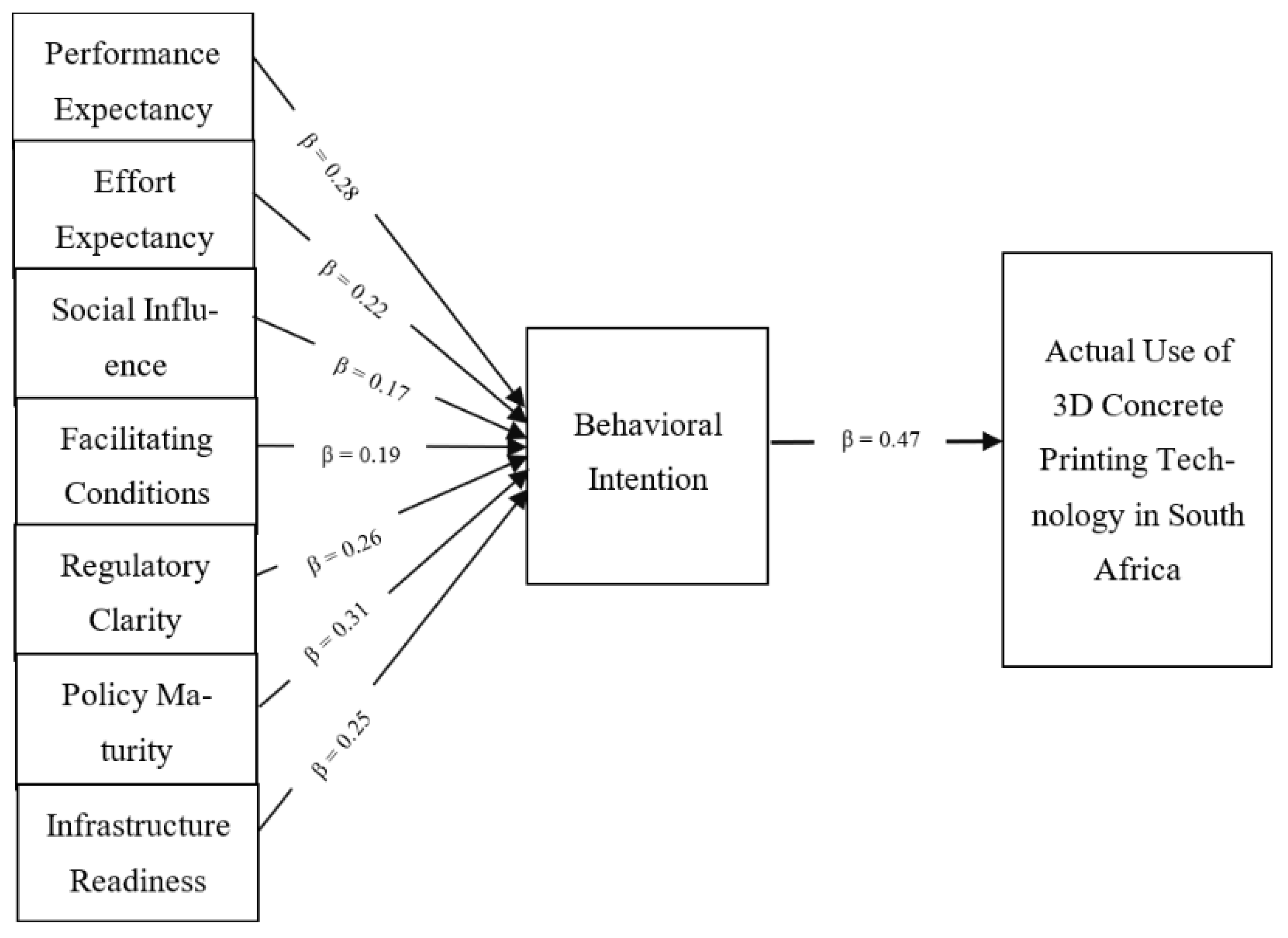

4.1.1. Model Structure

4.1.2. Hypotheses

4.1.3. Measurement Model Evaluation

4.1.4. Structural Model

- Path coefficient for hypothesis testing.

4.2. Qualitative Data Results

4.3. Triangulation and Interpretation of Findings

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BIM | Building Information Modeling |

| CAD | Computer-Aided Design |

| 3DCP | 3-Dimensional Concrete Printing |

| SMaCT | Sustainable Materials and Construction Technologies |

| TAM | Technology Acceptance Model |

| UTAUT | Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology |

| PE | Performance Expectancy |

| EE | Effort Expectancy |

| SI | Social Influence |

| FC | Facilitating Condition |

| RC | Regulatory Clarity |

| PM | Policy Maturity |

| IR | Infrastructure Readiness |

| BI | Behavioral Intention |

| AU | Actual Use |

| SABS | South Africa Bureau of Standards |

| NHBRC | National Home Builders Registration Council |

| DHS | Department of Human Settlement |

| CIDB | Construction Industry Development Board |

| CSIR | Council for Scientific and Industry Research |

| ECSA | Engineering Council of South Africa |

| SACAP | South African Council for the Architectural Profession |

| SACPCMP | South African Council for the Project and Construction Management Professions |

| SACQSP | South African Council for the Quantity Surveying Profession |

| EFA | Exploratory Factor Analysis |

| SEM | Structural Equation Modeling |

| NDC | Nationally Determined Contribution |

| ICT | Information and Communication Technology |

References

- Ullah, K.; Lill, I.; Witt, E. An Overview of BIM Adoption in the Construction Industry: Benefits and Barriers. In Proceedings of the 10th Nordic Conference on Construction Economics and Organization, Tallinn, Estonia, 7–8 May 2019; Available online: https://www.emerald.com/books/oa-edited-volume/15708/chapter/87072629/An-Overview-of-BIM-Adoption-in-the-Construction/10.1108/S2516-285320190000002052 (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Llale, J.; Setati, M.; Mavunda, S.; Ndlovu, T.; Root, D.; Wembe, P. A Review of the Advantages and Disadvantages of the Use of Automation and Robotics in the Construction Industry. In The Construction Industry in the Fourth Industrial Revolution; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-26528-1_20 (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Ambily, P.; Kaliyavaradhan, S.; Rajendran, N. Top challenges to widespread 3D concrete printing (3DCP) adoption—A review. Eur. J. Environ. Civ. Eng. 2024, 28, 300–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khajavi, S.H.; Tetik, M.; Mohite, A.; Peltokorpi, A.; Li, M.; Weng, Y.; Holmström, J. Additive Manufacturing in the Construction Industry: The Comparative Competitiveness of 3D Concrete Printing. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 3865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghimien, D.; Aigbavboa, C.; Aghimien, L.; Thwala, W.D.; Ndlovu, L. Making a case for 3D printing for housing delivery in South Africa. Int. J. Hous. Mark. Anal. 2020, 13, 565–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebel, S.; Top, S.M.; Takva, C.; Gokgoz, B.I.; Llerisoy, Z.Y.; Sahmaran, M. Investigation of three-dimensional concrete printing (3DCP) technology in AEC industry in the context of construction, performance and design. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Civil Engineering and Architecture Congress (ICEARC’23), Trabzon, Turkey, 12–14 October 2023; AVESİS: Phoenix, AZ, USA, 2023. Available online: https://avesis.gazi.edu.tr/yayin/307fb186-4992-4c45-99b5-c2aacfb23f6e/investigation-of-three-dimensional-concrete-printing-3dcp-technology-in-aec-industry-in-the-context-of-construction-performance-and-design (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Marutlulle, N.K. A critical analysis of housing inadequacy in South Africa and its ramifications. Afr. Public Serv. Deliv. Perform. Rev. 2021, 9, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhlongo, Z.D.; Gumbo, T.; Musonda, I.; Moyo, T. Sustainable low-income housing: Exploring housing and governance issues in the Gauteng City Region, South Africa. Urban Gov. 2024, 4, 136–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiedu, R.O.; Adaku, E. Cost overruns of public sector construction projects: A developing country perspective. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2019, 13, 66–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windapo, A.O. Skilled labour supply in the South African construction industry: The nexus between certification, quality of work output and shortages: Original research. SA J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2016, 14, a750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, L.S.; Forst, L.S. Workers’ Compensation Costs Among Construction Workers: A. robust regression analysis. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2009, 51, 1306–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adun, H.; Ampah, J.D.; Dagbasi, M. Transitioning Toward a Zero-Emission Electricity Sector in a Net-Zero Pathway for Africa Delivers Contrasting Energy, Economic and Sustainability Synergies Across the Region. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 15522–15538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahachi, J. Innovative building technologies 4.0: Fast-tracking housing delivery through 3D printing. S. Afr. J. Sci. 2021, 117, 12344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rollakanti, C.R.; Prasad, C.V.S.R. Applications, performance, challenges and current progress of 3D concrete printing technologies as the future of sustainable construction—A state of the art review. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 65, 995–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capêto, A.P.; Jesus, M.; Uribe, B.E.B.; Guimarães, A.S.; Oliveira, A.L.S. Building a Greener Future: Advancing Concrete Production Sustainability and the Thermal Properties of 3D-Printed Mortars. Buildings 2024, 14, 1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- İlerisoy, Z.Y.; Takva, Ç.; Top, S.M.; Gökgöz, B.İ.; Gebel, Ş.; İlcan, H.; Şahmaran, M. The effectiveness of 3D concrete printing technology in architectural design: Different corner-wall combinations in 3D printed elements and geometric form configurations in residential buildings. Archit. Sci. Rev. 2025, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.; Alomayri, T.; Noaman, M.F.; Zhang, C. 3D Printed Concrete for Sustainable Construction: A Review of Mechanical Properties and Environmental Impact. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2025, 32, 2713–2743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L. Reskilling and Upskilling the Future-ready Workforce for Industry 4.0 and Beyond. Inf. Syst. Front. 2022, 26, 1697–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghayedi, A.; Mahachi, J.; Lediga, R.; Mosiea, T.; Phalafala, E. Revolutionizing affordable housing in Africa: A comprehensive technical and sustainability study of 3D-printing technology. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 105, 105329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adaloudis, M.; Bonnin Roca, J. Sustainability tradeoffs in the adoption of 3D Concrete Printing in the construction industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 307, 127201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayathilakage, R.; Rajeev, P.; Sanjayan, J. Rheometry for Concrete 3D Printing: A Review and an Experimental Comparison. Buildings 2022, 12, 1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babafemi, A.J.; Kolawole, J.T.; Miah, M.J.; Paul, S.C.; Panda, B. A Concise Review on Interlayer Bond Strength in 3D Concrete Printing. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babafemi, A.J.; Kolawole, J.T.; Chang, Z.; Šavija, B. Short-Term Creep and Prediction of Anisotropic Strength of 3d Printed Concrete Under Compressive Stress; Social Science Research Network: Rochester, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colyn, M.; van Zijl, G.; Babafemi, A.J. Fresh and strength properties of 3D printable concrete mixtures utilising a high volume of sustainable alternative binders. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 419, 135474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, W.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, K.; Uddin, N. Experimental and Numerical Investigation of an Innovative 3DPC Thin-Shell Structure. Buildings 2023, 13, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oulkhir, F.Z.; Akhrif, L.; El Jai, M. 3D concrete printing success: An exhaustive diagnosis and failure modes analysis. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 2024, 10, 517–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oke, A.E.; Atofarati, J.O.; Bello, S.F. Awareness of 3D printing for sustainable construction in an emerging economy. Constr. Econ. Build. 2022, 22, 52–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bos, F.P.; Menna, C.; Pradena, M.; Kreiger, E.; da Silva, W.R.L.; Rehman, A.U.; Weger, D.; Wolfs, R.J.M.; Zhang, Y.; Ferrara, L.; et al. The realities of additively manufactured concrete structures in practice. Cem. Concr. Res. 2022, 156, 106746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamtsevich, L.; Pustovgar, A.; Adamtsevich, A. Assessing the Prospects and Risks of Delivering Sustainable Urban Development Through 3D Concrete Printing Implementation. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebel, S.; Top, S.M.; Takva, C.; Gokgoz, B.I.; Ilerisoy, Z.Y.; Sahmaran, M. Exploring the role of 3D concrete printing in AEC: Construction, design, and performance. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. Innov. 2024, 7, 229–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, M.; Matos, A.M. 3D Construction Printing Standing for Sustainability and Circularity: Material-Level Opportunities. Materials 2023, 16, 2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, M.; Nematollahi, B.; Sanjayan, J. Printability, accuracy and strength of geopolymer made using powder-based 3D printing for construction applications. Autom. Constr. 2019, 101, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.A.; İlcan, H.; Aminipour, E.; Şahin, O.; Al Rashid, A.; Şahmaran, M.; Koç, M. Buildability analysis on effect of structural design in 3D concrete printing (3DCP): An experimental and numerical study. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2023, 19, e02295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, M.H.; Besklubova, S.; Zhong, R.Y. Economic analysis of offsite and onsite 3D construction printing techniques for low-rise buildings: A comparative value stream assessment. Addit. Manuf. 2024, 89, 104292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batarseh, S.; Kamardeen, I. The Impact of Individual Beliefs and Expectations on BIM Adoption in the AEC Industry. In EPiC Series in Education Science; EasyChair: Stockport, UK, 2017; pp. 466–475. Available online: https://easychair.org/publications/paper/MhkG (accessed on 11 November 2023).

- Jayaseelan, R.; Brindha, D. A Qualitative Approach Towards Adoption of Information and Communication Technology by Medical Doctors Applying UTAUT Model. J. Xi’an Univ. Archit. Technol. 2020, 12, 4689–4703. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, M.N.K.; Lewis, P.; Thornhill, A. Research Methods for Business Students, 8th ed.; Pearson: New York, NY, USA, 2019; ISBN 978-1-292-20878-7. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, D.-C.; Lin, S.-H.; Ma, H.-L.; Wu, D.-B. Use of a Modified UTAUT Model to Investigate the Perspectives of Internet Access Device Users. Int. J. Hum.–Comput. Interact. 2017, 33, 549–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Davis, G.B.; Davis, F.D. User Acceptance of Information Technology: Toward a Unified View. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nematollahi, B.; Xia, M.; Sanjayan, J. Current Progress of 3D Concrete Printing Technologies. In Proceedings of the 34th International Symposium on Automation and Robotics in Construction (IAARC) Tribun EU, s.r.o., Brno, Taipei, Taiwan, 28 June–1 July 2017; Available online: http://www.iaarc.org/publications/2017_proceedings_of_the_34rd_isarc/current_progress_of_3d_concrete_printing_technologies.html (accessed on 26 July 2025).

- Al-Raqeb, H.; Ghaffar, S.H. 3D Concrete Printing in Kuwait: Stakeholder Insights for Sustainable Waste Management Solutions. Sustainability 2024, 17, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, A.U.; Perrot, A.; Birru, B.M.; Kim, J.-H. Recommendations for quality control in industrial 3D concrete printing construction with mono-component concrete: A critical evaluation of ten test methods and the introduction of the performance index. Dev. Built Environ. 2023, 16, 100232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhooshan, S.; Bhooshan, V.; Dell’Endice, A.; Chu, J.; Singer, P.; Megens, J.; Van Mele, T.; Block, P. The Striatus bridge. Archit. Struct. Constr. 2022, 2, 521–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, A.; Kazemian, A.; Ataei, S. Comparative Analysis of 3D Printed Bridge Construction in Louisiana. Publications [Internet]. Available online: https://repository.lsu.edu/transet_pubs/152 (accessed on 1 December 2022).

- Fernandez, L.I.C.; Caldas, L.R.; Mendoza Reales, O.A. Environmental evaluation of 3D printed concrete walls considering the life cycle perspective in the context of social housing. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 74, 106915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqaryouti, Y.; Suwaidi, M.A.; AlKhuwaildi, R.M.; Kolthoum, H.; Youssef, I.; Imam, M.A. A Case Study of the Largest 3D Printed Villa: Breaking Boundaries in Sustainable Construction. E3S Web Conf. 2024, 586, 01002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Z.Y.; Wolfs, R.J.M.; Bos, F.P.; Salet, T.A.M. A Framework for Large-Scale Structural Applications of 3D Printed Concrete: The Case of a 29 m Bridge in the Netherlands. Open Conf. Proc. 2022, 1, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela Aguilera, A.; Tsenkova, S. Build it and they will come: Whatever happened to social housing in Mexico. Urban Res. Pract. 2019, 12, 493–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sklair, L. The Icon Project: Architecture, Cities, and Capitalist Globalization; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017; p. 352. ISBN 978-0-19-046418-9. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, X.; Zhang, R.; Yang, R.; Dai, J. Innovation in Construction: A Critical Review and Future Research. Int. J. Innov. Sci. 2014, 6, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okangba, S.; Khatleli, N.; Root, D. Indicators for Construction Projects Supply Chain Adaptability using Blockchain Technology: A Review. In Proceedings of the International Structural Engineering and Construction, Cairo, Egypt, 26–31 July 2021; Volume 8, pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rane, N.; Choudhary, S.; Rane, J. Leading-edge Technologies for Architectural Design: A Comprehensive Review. Int. J. Arch. Plan. 2023, 3, 12–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ifinedo, P. Technology Acceptance by Health Professionals in Canada: An Analysis with a Modified UTAUT Model. In Proceedings of the 2012 45th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Maui, HI, USA, 4–7 January 2012; pp. 2937–2946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Thong, J.Y.L.; Xu, X. Consumer Acceptance and Use of Information Technology: Extending the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology. MIS Q. 2012, 36, 157–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilal, M.; Maqsood, T. Toward Improving BIM Acceptance in Facilities Management: A Hybrid Conceptual Model Integrating TTF and UTAUT; RMIT University: Melbourne, Australia, 2017; Available online: https://researchrepository.rmit.edu.au/esploro/outputs/9921886344901341?institution=61RMIT_INST&skipUsageReporting=true&recordUsage=false/2006100336 (accessed on 11 November 2023).

- Hewavitharana, T.; Nanayakkara, S.; Perera, A.; Perera, P. Modifying the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) Model for the Digital Transformation of the Construction Industry from the User Perspective. Informatics 2021, 8, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okangba, S.; Khatleli, N.; Root, D. On the Journey to Blockchain Technology, BIM and the BEE in the Construction Sector. In Proceedings of the International Structural Engineering and Construction, Sydney, Australia, 28 November–2 December 2022; Available online: https://www.isec-society.org/ISEC_PRESS/ASEA_SEC_06/xml/CON-16.xml (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Azamela, J.C.; Tang, Z.; Ackah, O.; Awozum, S. Assessing the Antecedents of E-Government Adoption: A Case of the Ghanaian Public Sector. SAGE Open 2022, 12, 21582440221101040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahul, A.V.; Santhanam, M.; Meena, H.; Ghani, Z. 3D printable concrete: Mixture design and test methods. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2019, 97, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walzer, A.N.; Kozlova, M.; Mohite, A.; Yeomans, J.S.; Hall, D. A Stochastic Decision-Support Framework for Exploring Strategic Pathways in 3D Concrete Printing; Social Science Research Network: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Gao, Y.; Chen, H.; Jiao, H.; Dong, M.; Bier, T.; Kim, M. 3D printing concrete technology from a rheology perspective: A review. Adv. Cem. Res. 2024, 36, 567–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klenam, D.; Asumadu, T.; Bodunrin, M.; Obiko, J.; Genga, R.; Maape, S.; McBagonluri, F.; Soboyejo, W. Frontiers|Toward sustainable industrialization in Africa: The potential of additive manufacturing—An overview. Front. Manuf. Technol. 2025, 4, 1410653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blind, K. 12: The overall impact of economic, social and institutional regulation on innovation. In Handbook of Innovation and Regulation; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2023; Available online: https://www.elgaronline.com/edcollchap/book/9781800884472/b-9781800884472.00020.xml (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Taherdoost, H. A review of technology acceptance and adoption models and theories. Procedia Manuf. 2018, 22, 960–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemay, D.J.; Doleck, T.; Bazelais, P. Context and technology use: Opportunities and challenges of the situated perspective in technology acceptance research. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2019, 50, 2450–2465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardi, P.M. Doing Survey Research|A Guide to Quantitative Methods; Routledge: New Yor, NY, USA, 2018; Available online: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/mono/10.4324/9781315172231/survey-research-peter-nardi (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Leung, L. Validity, reliability, and generalizability in qualitative research. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2015, 4, 324–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, M.D. Triangulation: A Method to Increase Validity, Reliability, and Legitimation in Clinical Research. J. Emerg. Nurs. 2019, 45, 103–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Wyk, L.; Kajimo-Shakantu, K.; Opawole, A. Adoption of innovative technologies in the South African construction industry. Int. J. Build. Pathol. Adapt. 2021, 42, 410–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, S.; Greenwood, M.; Prior, S.; Shearer, T.; Walkem, K.; Young, S.; Bywaters, D.; Walker, K. Purposive sampling: Complex or simple? Research case examples. J. Res. Nurs. 2020, 25, 652–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, C.; Scott, S.; Geddes, A. Snowball Sampling. In Qualitative Research Designs; SAGE Research Methods Foundations: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2019; Available online: http://methods.sagepub.com/foundations/snowball-sampling/10.4135/9781526421036831710 (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Adams, W.C. Conducting Semi-Structured Interviews. In Handbook of Practical Program Evaluation; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 492–505. ISBN 978-1-119-17138-6. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/9781119171386.ch19 (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Larson, R.B. Controlling social desirability bias. Int. J. Mark. Res. 2019, 61, 534–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, G.W.; Cooper-Thomas, H.; Lau, R.S.; Wang, L.C. Reporting reliability, convergent and discriminant validity with structural equation modeling: A review and best-practice recommendations. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2024, 41, 745–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, R.; Campbell, D.; Thatcher, J.; Roberts, N. Operationalizing Multidimensional Constructs in Structural Equation Modeling: Recommendations for IS Research. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2012, 30, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakol, M.; Dennick, R. Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. Int. J. Med. Educ. 2011, 2, 53–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Den, S.; Schneider, C.; Mirzaei, A.; Carter, S. How to measure a latent construct: Psychometric principles for the development and validation of measurement instruments. Int. J. Pharm. Pract. 2020, 28, 326–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bujang, M.A.; Omar, E.D.; Baharum, N.A. A Review on Sample Size Determination for Cronbach’s Alpha Test: A Simple Guide for Researchers. Malays. J. Med. Sci. 2018, 25, 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cope, D.G. Methods and Meanings: Credibility and Trustworthiness of Qualitative Research. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2014, 41, 89–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slevin, E.; Sines, D. Enhancing the truthfulness, consistency and transferability of a qualitative study: Utilising a manifold of approaches. Nurse Res. 2000, 7, 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anney, V.N. Ensuring the Quality of the Findings of Qualitative Research: Looking at Trustworthiness Criteria. J. Emerg. Trends Educ. Res. Policy Stud. 2015, 5, 272–281. [Google Scholar]

- Nkansah, B.K. On the Kaiser-Meier-Olkin’s Measure of Sampling Adequacy. Math. Theory Model. 2018, 8, 52–76. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, B.; Onsman, A.; Brown, T. Exploratory Factor Analysis: A Five-Step Guide for Novices. J. Emerg. Prim. Health Care 2010, 8, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Winter, J.C.F.; Dodou, D. Factor recovery by principal axis factoring and maximum likelihood factor analysis as a function of factor pattern and sample size. J. Appl. Stat. 2012, 39, 695–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, K.D.; Herdman, A.O. Understanding the Impact of Convergent Validity on Research Results. Organ. Res. Methods 2012, 15, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ab Hamid, M.R.; Sami, W.; Mohmad Sidek, M.H. Discriminant Validity Assessment: Use of Fornell & Larcker criterion versus HTMT Criterion. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2017, 890, 12163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V.; Hayfield, N.; Terry, G. Thematic Analysis. In Handbook of Research Methods in Health Social Sciences; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; Available online: https://link.springer.com/rwe/10.1007/978-981-10-5251-4_103 (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Yossef, M.; Chen, A. Applicability and limitations of 3D printing for civil structures. In Proceedings of the 2015 Conference on Autonomous and Robotic Conference of Infrastructure, Ames, IA, USA, 2–3 June 2015; IA State University: Ames, IA, USA, 2015; pp. 237–246. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, S.; Weng, T.; Jin, R.; Yang, M.; Yu, M.; Zhang, W.; Wang, X.; Han, C. Curcumin-incorporated 3D bioprinting gelatin methacryloyl hydrogel reduces reactive oxygen species-induced adipose-derived stem cell apoptosis and improves implanting survival in diabetic wounds. Burns Trauma 2022, 10, tkac001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voorwinden, A. The privatised city: Technology and public-private partnerships in the smart city. Law Innov. Technol. 2021, 13, 439–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanello, G.; Fu, X.; Mohnen, P.; Ventresca, M. The Creation and Diffusion of Innovation in Developing Countries: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Econ. Surv. 2016, 30, 884–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Constructs | Mean | Std Dev | Cronbach’s Alpha (α) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Performance expectancy | 4.10 | 0.61 | 0.81 |

| Effort expectancy | 3.85 | 0.67 | 0.79 |

| Social influence | 3.60 | 0.72 | 0.77 |

| Facilitating conditions | 3.75 | 0.64 | 0.83 |

| Regulatory clarity | 3.30 | 0.59 | 0.88 |

| Policy maturity | 3.25 | 0.57 | 0.87 |

| Infrastructure readiness | 3.15 | 0.60 | 0.86 |

| Behavioral intention | 3.95 | 0.68 | 0.82 |

| Actual use | 3.70 | 0.65 | 0.80 |

| Factors | Constructs | Number of Items | Cronbach’s Alpha (α) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Performance expectancy | 3 | 0.75–0.82 |

| 2 | Effort expectancy | 3 | 0.71–0.78 |

| 3 | Social influence | 3 | 0.69–0.81 |

| 4 | Facilitating conditions | 3 | 0.72–0.85 |

| 5 | Regulatory clarity | 3 | 0.80–0.88 |

| 6 | Policy maturity | 3 | 0.79–0.87 |

| 7 | Infrastructure readiness | 3 | 0.77–0.86 |

| 8 | Behavioral intention | 3 | 0.76–0.84 |

| 9 | Actual use | 3 | 0.73–0.82 |

| Constructs | Composite Reliability | Average Variance Extracted | Cronbach’s Alpha (α) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Performance expectancy | 0.89 | 0.68 | 0.85 |

| Effort expectancy | 0.87 | 0.64 | 0.83 |

| Social influence | 0.82 | 0.59 | 0.79 |

| Facilitating conditions | 0.85 | 0.61 | 0.80 |

| Regulatory clarity | 0.91 | 0.72 | 0.88 |

| Policy maturity | 0.92 | 0.74 | 0.89 |

| Infrastructure readiness | 0.90 | 0.69 | 0.87 |

| Behavioral intention | 0.88 | 0.65 | 0.84 |

| Actual use | 0.86 | 0.66 | 0.83 |

| Hypotheses | Path | β (Beta) | t-Value | p-Value | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | PE → BI | 0.28 | 4.21 | <0.001 | Supported |

| H2 | EE → BI | 0.22 | 3.76 | <0.001 | Supported |

| H3 | SI → BI | 0.17 | 2.85 | 0.005 | Supported |

| H4 | FC → BI | 0.19 | 3.10 | 0.002 | Supported |

| H5 | RC → BI | 0.26 | 4.55 | <0.001 | Supported |

| H6 | PM → BI | 0.31 | 5.14 | <0.001 | Supported |

| H7 | IR → BI | 0.25 | 4.00 | <0.001 | Supported |

| H8 | BI → AU | 0.47 | 6.32 | <0.001 | Supported |

| Fit Index | Value | Acceptable Threshold | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chi-square | 1.87 | <3.00 | Good fit |

| Root Mean Square Error of Approximation | 0.05 | ≤0.08 | Excellent fit |

| Comparative Fit Index | 0.95 | ≥0.90 | Excellent fit |

| Tucker–Lewis Index | 0.94 | ≥0.90 | Excellent fit |

| Standardized Root Mean Square Residual | 0.04 | ≤0.08 | Good fit |

| Goodness of Fit Index | 0.92 | ≥0.90 | Good fit |

| Constructs | PE | EE | SI | FC | RC | PM | IR | BI | AU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PE | 0.82 | ||||||||

| EE | 0.48 | 0.80 | |||||||

| SI | 0.44 | 0.46 | 0.77 | ||||||

| FC | 0.52 | 0.45 | 0.49 | 0.78 | |||||

| RC | 0.43 | 0.39 | 0.41 | 0.47 | 0.85 | ||||

| PM | 0.41 | 0.36 | 0.43 | 0.44 | 0.52 | 0.86 | |||

| IR | 0.45 | 0.41 | 0.40 | 0.48 | 0.50 | 0.53 | 0.83 | ||

| BI | 0.53 | 0.49 | 0.47 | 0.51 | 0.54 | 0.56 | 0.52 | 0.81 | |

| AU | 0.39 | 0.37 | 0.35 | 0.38 | 0.42 | 0.46 | 0.44 | 0.61 | 0.81 |

| Theme | Illustrative Quotes | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Performance Potential | “It can halve the time we spend on-site. Less labour, less waste” Civil Engineer | Professionals believe 3DCP can reduce construction time and material waste. |

| Learning Curve and Complexity | “We barely know how it works. Most firms would need serious retraining” Contractor | Many express concerns over the lack of expertise and a steep learning curve. |

| Influence of Policy Actors | “We’re not against it; we just need it to be standardized first” Regulator | Regulatory bodies are hesitant, citing a lack of standards and risk data. |

| Infrastructural Gaps | “In some rural areas, just delivering cement is difficult, let alone a printer” Focus Group Participant | Regional infrastructure and logistics remain key barriers. |

| Perceived Legitimacy | “It sounds elitist. Is it really for poor people or just show-off tech?” Quantity Surveyor | Some participants question whether 3DCP is appropriate for low-income housing. |

| Support for Innovation | “We need more pilot projects. You don’t change the industry by talking” Architect | Younger professionals and academics showed high openness to experimentation. |

| Constructs | Quantitative Finding, SEM Path Coefficient, and Significance | Qualitative Insight | Interpretation | Integration Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Performance Expectancy | β = 0.31 p < 0.01 Strong predictor of behavioral intention | 3DCP seen as time-saving and innovative but only if conditions allow. | Consistent. Professionals appreciate performance potential but need proven outcomes to build confidence. | Convergent |

| Effort expectancy | β = 0.24 p < 0.01 Moderate predictor | Concerns about knowledge gaps and complexity of the technology. | Consistent. Perceived ease of use remains a challenge. | Convergent |

| Social influence | β = 0.18 p < 0.05 Smaller but significant impact | Younger professionals and academic voices are more enthusiastic. | Partial convergence. Social push is still limited across different sectors. | Partial convergence |

| Facilitating Conditions | β = 0.21 p < 0.05 Significant influence | Lack of structured training, logistics, and support systems cited. | Strong alignment. Inadequate infrastructure and skills. | Convergent |

| Regulatory Clarity | β = 0.29 p < 0.01 High predictor | Regulatory uncertainty, absence of code inclusion, fear of liability acknowledged. | Strong convergence. Uncertainty delays planning, design, and investment decisions. Regulatory ambiguity is a major barrier. | Convergent |

| Policy Maturity | β = 0.33 p < 0.01) Strongest influence | No coherent national framework, fragmented initiatives noted by regulators and professionals alike. | Consistent. Clear policies are critical enablers. | Convergent |

| Infrastructure Readiness | β = 0.27 p < 0.01 Significant | Urban-rural divide, and lack of local 3DCP supply networks limits practical deployment. | Strong convergence. Regional inequalities are a key limiting factor. | Convergence |

| Behavioral Intention to accept 3DCP technology | β = 0.48 p < 0.001 Highly significant | Interest is high but practical deployment is rare without systemic enablers. | This validates the need to bridge intention–action gaps. | Convergence |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Okangba, S.; Ngcobo, N.; Mahachi, J. Bridging Innovation and Governance: A UTAUT-Based Mixed-Method Study of 3D Concrete Printing Technology Acceptance in South Africa. Architecture 2025, 5, 131. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture5040131

Okangba S, Ngcobo N, Mahachi J. Bridging Innovation and Governance: A UTAUT-Based Mixed-Method Study of 3D Concrete Printing Technology Acceptance in South Africa. Architecture. 2025; 5(4):131. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture5040131

Chicago/Turabian StyleOkangba, Stanley, Ntebo Ngcobo, and Jeffrey Mahachi. 2025. "Bridging Innovation and Governance: A UTAUT-Based Mixed-Method Study of 3D Concrete Printing Technology Acceptance in South Africa" Architecture 5, no. 4: 131. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture5040131

APA StyleOkangba, S., Ngcobo, N., & Mahachi, J. (2025). Bridging Innovation and Governance: A UTAUT-Based Mixed-Method Study of 3D Concrete Printing Technology Acceptance in South Africa. Architecture, 5(4), 131. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture5040131