Abstract

This research develops a city Branding–Competitiveness Index (BCI) that comprehend symbolic city branding elements with quantifiable aspects of urban competitiveness. It examines the effectiveness of branding strategies in emerging cities in MENA region to improve their competitiveness, focusing on King Abdullah Economic City in Saudi Arabia and New Alamein City in Egypt. This research employs a mixed-method approach that integrates systematic literature review, expert survey, and quantitative analysis using IBM SPSS Statistics 26. The BCI was built considering primary categories, then improved through expert review to make sure it is valid and relevant to the practice, then utilized on the two case studies to evaluate its efficacy and performance. Results indicated that both cities showed relatively better performance in the infrastructure, environmental planning, and accessibility indicating that government-led development models work well on some level. But they achieved lower scores in social cohesion, cultural identity, and participatory governance, highlighting the gap between urban development and the lifestyle in cities. The BCI helped identify these disparities and showed indicative insights for enhancing branding strategy. This empirical BCI provides a guiding framework for policymakers and urban planners to evaluate the strategic planning for city branding, and sustainable competitiveness. The findings demonstrate the potential applicability of BCI to emerging cities, while acknowledging that further testing in diverse international contexts is needed.

1. Introduction

In a world of global urbanization, cities are no longer geographic entities but active competitors striving for visibility, investment, and recognition in an increasingly interconnected and performance-oriented world. As cities evolve into critical nodes of economic, social, and technological innovation, the question of why certain cities thrive while others fall behind has become central to urban policy and academic inquiry. Urban competitiveness is no longer measured solely by economic indicators, but also by a city’s ability to project a distinct identity, foster livability, and attract diverse stakeholders—residents, investors, tourists, and knowledge workers alike.

The United Nations projects that by 2030, about 60% of the global population will reside in urban areas. This unprecedented demographic shift intensifies inter-city competition over resources. In response, cities have increasingly adopted strategic branding practices that aim to shape perception, promote place-based values, and leverage their unique assets to build a competitive advantage. Borrowing from marketing and corporate branding paradigms, city branding has emerged as a powerful urban development tool—transforming not only how cities are seen but also how they plan, manage, and position themselves within national and global systems. Unlike corporate branding, however, urban branding operates in a far more complex context, involving multiple layers of governance, heterogeneous user groups, and a dynamic mix of cultural, environmental, economic, and spatial variables. This complexity becomes particularly pronounced in newly established or rapidly developing cities that lack historical legacies or globally recognized identities. In such contexts, branding is not merely about promotion, but about constructing meaning, authenticity, and strategic direction from the ground up [1,2,3]. Despite extensive literature on city branding, significant scientific gap remains regarding how branding aligns or conflicts with the determinants of urban competitiveness, especially in recently established cities that lack historical identity anchors.

This research responds to these challenges by developing a comprehensive and multidimensional framework, the Branding Competitiveness Index (BCI), that links city branding strategies with measurable indicators of urban competitiveness. Based on a systematic literature review of academic research and an expert survey, the study synthesizes key factors and indicators across the variable aspects including administrative, economic, social, environmental, and urban aspects. It then applies this framework to the analysis of two representative case studies—King Abdullah Economic City (Saudi Arabia) and New Alamein City (Egypt)—to examine how new cities operationalize branding efforts to achieve competitive positioning. The aim is to provide both a theoretical contribution to the discourse on city branding and a practical tool for evaluating and guiding branding strategies in emerging urban environments. Accordingly, this research addresses the following questions:

- How can city branding and urban competitiveness be integrated into a unified evaluative framework?

- To what extent do emerging MENA cities operationalize city branding strategies in ways that support urban competitiveness?

- How can the adapted Branding–Competitiveness Index (BCI) identify areas of conflict and compatibility between branding and competitiveness?

2. Literature Review

Cities are intricate and evolving entities, and their perception and standing fluctuate with time. Effective branding initiatives significantly enhance a city’s attractiveness, hence attracting tourists, businesses, and investors. These programs facilitate economic growth and prosperity in cities, enhancing their reputations both locally and globally, thereby attracting capital and skilled labor more effectively. Scholarly debates highlight a persistent tension between ‘entrepreneurial’ branding—aimed at attracting investment—and socially oriented branding that prioritizes residents’ needs and local cultural expression [3,4].

Recent scholarly research on city branding strategies has predominantly concentrated on tourism and recreation, neglecting the broader economic, social, and environmental dimensions of city branding. Tourism significantly contributes to the economy; nevertheless, an effective urban branding plan must encompass several municipal activities and attract a diverse array of stakeholders, including residents, investors, enterprises, and visitors. Furthermore, the majority of existing research has concentrated on branding initiatives in prominent cities rich in historical and civic significance. Conversely, few studies have examined branding techniques tailored exclusively for new urban developments. These advancements provide distinct challenges in defining their identities and garnering public attention [5,6,7]. Despite the existing extensive literature, limited research addresses how city branding operates in newly planned or rapidly developing cities that lack historical identity anchors. These cities face distinct challenges in establishing credibility, shaping meaning, and building socially grounded brands.

2.1. Brand and City Branding

By combining functional, emotional, and symbolic elements, city branding helps cities create unique identities, improve how people see them, and make them more competitive [8]. It involves crafting narratives around unique attributes—cultural heritage, economic strengths, and livability—to foster positive perceptions, attract investment, and engage communities [9]. Effective city branding transcends superficial elements, aligning strategic vision, management, and stakeholder collaboration with the city’s image [10,11]. City branding is widely recognized as interdisciplinary area that include administrative, economic, social, environmental, and urban aspects, influencing cities’ global competitiveness and sustainable development. Yet city branding has also been criticized for privileging symbolic imagery and entrepreneurial city-making at the expense of inclusive, community-driven development.

Several scholars warned that city branding may shift urban development priorities away from local community needs and toward investors, tourists, and global markets. Such concerns argue that branding strategies risk privileging symbolic visibility over substantive improvements in equity, inclusion, and everyday urban life. In new or rapidly planned cities, this concern is amplified: branding often precedes the emergence of local identity, resulting in top-down narratives that may not reflect community values or lived realities [8,9,10,11,12,13].

2.2. City Branding Levels

City branding happens on different levels, from the national level to the local level. At the national level, branding initiatives try to make the country more visible around the world, bring in more business, and boost exports. Branding at the city level is more focused on things like improving the quality of life, developing the city, and creating a unique identity for the city. Branding on a smaller scale, such branding a neighborhood or area, focuses on unique local attributes and meets the demands of certain markets or communities [12,13]. To make the most of the particular features and goals of each urban setting, each branding level needs its own set of strategies.

2.3. City Branding Index

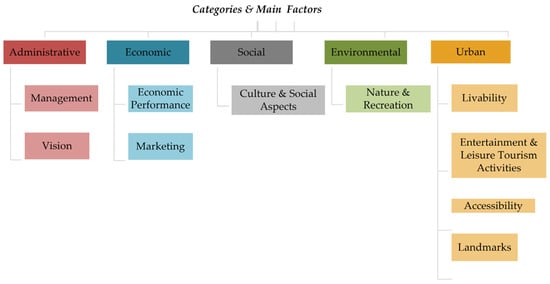

The City Branding Index (CBI) is a complete, scientifically based method to examine and improve city branding. The CBI takes into consideration a range of factors, such as government performance, economic strength, levels of social cohesion, environmental performance, and infrastructure quality. Quality of governance, alignment of strategic vision, and involvement of stakeholders are all components of administrative effectiveness [14]. Economic vitality examines things like how stable the economy is, how appealing it is to investors, and how many jobs are available. Cultural identity, community involvement, and social inclusion are all components of social cohesiveness. Environmental sustainability looks at how resources are used, how green infrastructure is built, and how pollution is controlled. The quality of urban infrastructure includes aspects like transportation networks, accessibility, public amenities, and the presence of landmarks. Different methods have been used in the past to study city branding. Rainisto (2003) [15] argued that for management and strategic planning are important for city branding. Anholt (2007) [16] introduced the GMI model, which focused on global presence and city image. Zenker and Beckmann (2013) [17] looked into how people from different places see things differently, focusing on things like livability and community involvement. Bothma (2015) also highlighted how important it is to use holistic, integrative criteria that take into consideration economic, cultural, and social factors [18]. All of these various approaches collectively inform the conceptual foundations of the City Branding Index’s contribution to urban competitiveness [19,20,21]. Currently, many of the existing indices focus heavily on external perception and global positioning, potentially overlooking issues such as social equity, and local participation. Figure 1 illustrates the main categories and factors of the CBI based on previous research.

Figure 1.

The framework of categories with its main factors of city branding.

2.4. Urban Competitiveness

Urban competitiveness denotes a city’s capacity to attract and retain investments, skills, and resources to foster economic growth, social cohesion, and environmental sustainability. Competitiveness includes various factors such as economic stability, market flexibility, innovative capacity, quality of life, and government effectiveness. However, scholars argue that competitiveness agendas may prioritize global market positioning over local needs, potentially reinforcing inequalities or overlooking community-level challenges. This tension underscores the need for competitiveness frameworks that consider both structural economic indicators and socially embedded dimensions of urban development [22].

Diverse methodologies have been established to evaluate urban competitiveness. Scholars proposed a pyramid model that highlights innovation, accessibility, and social aspects to improve quality of life. Bruneckiene (2010) [23] emphasized the significance of urban-specific indicators in addition to national economic considerations, integrating social, cultural, and environmental elements. Chao-Hung and Li-Chang (2010) [24] characterized competitiveness mostly in terms of economic strength within a global framework, emphasizing resource mobility and market dynamics. Du (2015) [25] assessed urban competitiveness by examining economic, social, cultural, environmental, and geographic aspects in Chinese cities. These methods emphasize the intricacy and multidisciplinary aspects of evaluating urban competitiveness, highlighting the necessity for cohesive frameworks to effectively direct urban development. Despite the breadth of existing models, there remains limited empirical integration between competitiveness and branding frameworks, particularly in the context of new cities where identity formation and economic positioning occur simultaneously. A competitive city ensures sustainable growth by balancing economic, social, environmental, and security factors. Success depends on unique advantages, market adaptability, and strategic management that understand challenges and opportunities. By integrating these elements, cities enhance global standing, foster innovation, and maintain long-term competitiveness.

2.5. Adapted City Branding and Urban Competitiveness Indexes

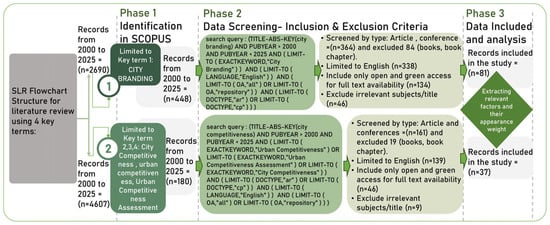

A systematic literature review (SLR) was created to ensure methodological rigor, transparency, and reproducibility. The review included peer-reviewed academic publications to ensure the reliability and relevance of the extracted indicators., in order to capture the current state of knowledge and debates within the scientific community concerning city branding and urban competitiveness. Searches were conducted in SCOPUS database using predefined keywords related to ‘city branding’, ‘urban competitiveness’, ‘city competitiveness’, and ‘urban competitiveness assessment’. The screening process applied inclusion criteria (peer-reviewed journal articles, conceptual and empirical studies, English language), publications in the period 2000–2025, and exclusion criteria (non-academic sources, non-urban contexts), as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Flowchart for the systematic literature review.

Therefore, the Adapted City Branding and Urban Competitiveness Index is based on a systematic literature review of 81 international studies for branding and 37 international studies for competitiveness, allowing the identification of factors and indicators used to assess the city branding and urban competitiveness, see Table 1. These were organized into ten thematic categories—administration, vision, economy, marketing, social factors, environment, urban livability, tourism and recreation, accessibility, and landmarks—which together form the initial structure of the adapted City Branding and Urban Competitiveness Indexes. As shown in Table 1, coding clearly indicates which indicators exhibit compatibility across both city branding and urban competitiveness, and which represent conflicting priorities, reflecting deeper structural tensions in the literature. Compatibility or conflict level was calculated based on the percentage of the difference between the relative weights for branding and competitiveness derived from SLR.

Table 1.

Adapted City Branding and Urban Competitiveness Index based on previous research (source: the authors).

A comparative analysis between city branding and urban competitiveness indexes shows that there are conflicts and compatibilities in how the two indices perceive urban attributes. There are a number of factors that are essential in both areas, especially when it involves institutional performance and the degree of public participation. Participation is one of the most significant factors in both city branding (8.2) and urban competitiveness (8.9). This shows the significance of governance, stakeholder collaboration, and institutional responsiveness in defining both urban identity and economic success. Transportation Services is also very important in both indexes (3.5 in branding and 8.1 in competitiveness), but it is much more important in competitiveness index because it highlights how infrastructure is needed for cities to work and for the economy to grow. Basic services like education and healthcare received good ratings in both areas (4.3 and 7.0, respectively). This shows that having access to services is a key part of both livability narratives in branding and productivity in competitiveness.

Some factors, on the other hand, remain left out in both indexes. Street Furniture and The Pulse, which includes indicators such as nightlife, and public amenities, are the lowest-rated, with scores between 1.0 and 2.4 on both indexes. This means that at the strategic level, micro-scale urban characteristics are not seen as vital for branding or competitiveness, even though they are important for local identity and the user experience. Natural Resources and Iconic Elements likewise do not seem to be very important in both indexes, since they both scored less than 3.0.

Even though these two indexes have certain things in common, there are some major distinctions between them as well. These distinctions show how priorities change when you go from image-based city branding to performance-based urban competitiveness. The most important difference is the aspect of Reality, which means that urban strategies should be in line with local resources and future problems. It is almost ignored in branding (0.4), but it is quite important in competitiveness (6.8). This distinction reflects the greater emphasis competitiveness frameworks place on feasibility, contextual alignment, and long-term economic resilience. Economic Stability (3.5 vs. 8.4) and Investment-Friendly Climate (3.1 vs. 8.1) show a similar pattern, with economic fundamentals taking precedence in competitiveness index. These increases show that the literature on competitiveness is more focused on issues such as structural economic resilience, market openness, and institutional support for growth than the symbolic connections that branding generally addresses.

Another significant distinction involves the way Human Resource development is handled. It goes up from 2.4 in city branding to 7.8 in urban competitiveness. This shows a shift from symbolic identification to investing in human capital, where education, skills training, and demographic structure are seen as key assets for remaining competitive. Local Culture, on the other hand, is less competitive (4.9) than it is in branding (5.9). This is because cultural legacy and social identity are used more in image-making techniques than in performance evaluations. This contrast underscores the conceptual gap between perception-driven branding models and performance-oriented competitiveness frameworks, especially in newly developed cities where identity and economic positioning evolve simultaneously.

In conclusion, certain fundamental factors, such as participation, services, and transportation, remain important in both indices. However, city branding focuses more on symbolic, cultural, and perceptual aspects, while urban competitiveness focuses more on economic, infrastructural, and human capital aspects. The different weights given to the factors support the concept that branding is about creating an urban image and identity, whereas competitiveness is about aligning with measurable, strategic outcomes. Urban policymakers are required to achieve a balance between visibility and viability in modern city development and to understand these differences.

3. Data and Methodology

This study adopts a mixed-method research design that integrates qualitative and quantitative approaches to develop and validate comprehensive frameworks for evaluating city branding and urban competitiveness. The methodology is organized into three interlinked phases: theoretical synthesis, expert surveys, and empirical validation through case studies.

3.1. Phase 1: Theoretical Analysis

The first phase involved a systematic literature review and theoretical analysis of 118 scholarly resources (81 on city branding and 37 on urban competitiveness) focusing on the different categories involved in both of them; including the different administrative, economic, social, environmental, and urban aspects. From this review, 18 sub-factors and 56 indicators were identified. Additionally, the literature review included an analysis for the frequency of these sub-factors in the relevant resources. These frequencies were normalized (0–10 scale) and used to generate preliminary literature-derived weights. These sub-factors and indicators serve as the foundation for Phase 2.

3.2. Phase 2: Experts Survey on the CBI and UCI

The experts survey on the CBI and UCI is the second phase, which involves designing and conducting surveys with urban development professionals, policymakers, and academics. Experts were recruited using purposive sampling, targeting individuals with experience in urban planning, policy, design, or academic research. Inclusion criteria required participants to hold relevant professional or academic positions and to have prior knowledge of city branding or urban competitiveness area. Invitations were distributed exclusively via professional networks and institutional contacts. A total of 35 invitations were sent, and 25 responses were received, yielding a response rate of 71.4%. This experts survey aims at:

- Validating the sub-factors and indicators identified from the literature review and theoretical analysis.

- Identifying the relative weight of each sub-factor.

- Exposing any gaps in the existing indexes.

The survey uses Likert-scale questions to gather expert opinions on the sub-factors. Participants also provided qualitative feedback to identify missing dimensions. The results were triangulated with the literature review findings to refine and recalibrate the weightings of the CBI and UCI sub-factors to ensure that the adapted indexes are both practically relevant and theoretically grounded.

3.3. Phase 3: Empirical Application Through Case Studies

This phase will examine and evaluate the concept of city branding and urban competitiveness utilized in specific new city models, which their governments aim to establish as new centers of urban growth. This phase involves the quantitative assessment of two newly planned cities—King Abdullah Economic City (Saudi Arabia) and New Alamein City (Egypt)—to examine how branding strategies align with competitiveness outcomes.

3.3.1. Selection of the Case Studies

These case studies were selected based on the following criteria:

- Reasons Behind the City’s Establishment: The reasons and circumstances that led to the city’s establishment affect the way it promotes itself. The case studies are all about newly built cities and are intended to serve as new hubs for urban development.

- Size, Population, and Context: All case studies are similar in terms of their area, size and population density. Additionally, the 2 cities are located in middle east Arabic countries.

- Economic and Geographic Aspects: The cities vary in terms of economic significance and development. The selected cases represents an economic model from Arab countries.

- Timeframe: Beginning in the early 2000s, when governments and cities started to recognize the value of branding cities and transitioned from theory to practical, understandable concepts, the selected cases were constructed in this era.

3.3.2. Analysis Methods for Case Studies

- Qualitative Content Analysis: The selected case studies are evaluated using qualitative methods to explore the degrees of their CBI and UCI. Previous research on these cities and expert surveys are analyzed to identify strengths and weaknesses in each city. Data sources included planning documents, city reports, academic evaluations, and development agency publications, while the quantitative analysis follows the adapted index in Phase 2. Participants in this survey were recruited through purposive and snowball sampling via academic networks, professional associations, and planning institutions. Inclusion criteria required respondents to hold relevant academic qualifications or professional experience in urban development–related fields. The survey was administered online, and participation was voluntary and anonymous to reduce response bias.

- Case Studies Comparative Analysis: A comparative analysis is performed using SPSS to calculate the mean, standard deviation, and component factor analysis to discern commonalities, best practices, and persistent difficulties across the chosen case studies. This step emphasizes the elements that contribute to effective city branding and urban competitiveness.

- Gap Analysis: The results from the case studies are compared with the theoretical study to find the gaps between intended strategies and actual execution. This investigation guides the development of the 2 cities and help in making further informed decisions for the urban development. This methodology offers a comprehensive approach to understanding and enhancing city branding and urban competitiveness by merging theoretical insights, expert validation, and practical case study analysis, thereby facilitating informed development decisions. This step identifies misalignments between strategic objectives and actual outcomes, offering insight into where branding narratives diverge from competitiveness realities.

4. Adapted City Branding and Urban Competitiveness Indexes Based on Experts Survey

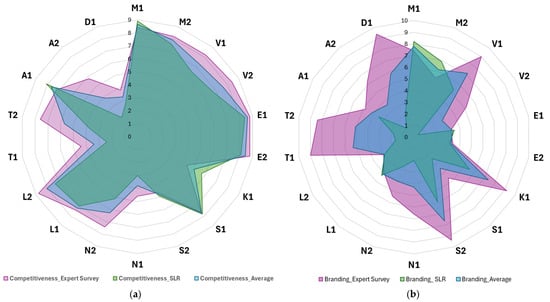

To validate the City Branding and Urban Competitiveness Indexes (CBI and UCI), a structured expert survey was conducted as a second step after the systematic literature review (SLR). The goal was to review, improve, and give weight to the sub-factors and indicators that were taken from 81 research on city branding and 37 research on urban competitiveness. Twenty-five professionals and academics took part in the survey. Those subjects included city planners, urban designers, policy makers, consultants, and university researchers. Experts rated how important each factor was for branding and competitiveness on a five-point Likert scale. Expert-derived scores were normalized and combined with SLR frequencies using a simple mean to generate the final weighting scheme for each sub-factor. Figure 3 shows the adapted indexes, which combine theoretical insights and experts opinions in a way that makes them more useful for evaluating city branding and urban competitiveness in new cities.

Figure 3.

(a) Urban Competitiveness Index based on SLR, expert survey, and its average—(b) city branding based on SLR, expert survey, and its average—(c) Adapted Branding Competitiveness Index (BCI) average as a balanced index level (source: the authors).

The expert survey results indicated some changes in priorities relative to the SLR findings, reflecting the shifting professional perspectives on effective city branding and urban competitiveness. In the CBI, the expert survey introduced notable shifts in emphasis relative to the SLR-derived weights, including Target Groups Diversity (from 5.3 to 9.0), Local Culture (from 5.9 to 9.4), and Street Furniture (from 1.0 to 6.2), highlighting the increasing acknowledgment of place-based identity, inclusivity, and spatial quality in influencing urban image. Conversely, the urban competitiveness index sustained elevated ratings for structural and economic variables. Job Opportunities, Investment-Friendly Climate, and Economic Infrastructure garnered high ratings from both SLR and expert survey (between 8.0 and 8.8), indicating continued prioritization of economic resilience and institutional capacity within competitiveness assessments. These differences reflect the broader tension mentioned in the literature between perception-oriented branding priorities and the performance-oriented focus of competitiveness frameworks.

The revised indexes demonstrate an expanded framework where symbolic identification and spatial experience are increasingly significant in city branding, while urban competitiveness continues to be rooted in systemic economic and institutional performance. The enhanced index provides a structured basis for evaluating the multifaceted nature of contemporary urban settings, facilitating evidence-based branding initiatives that are strategically sound and socially impactful.

5. Case Studies: KAEC and New Alamein

This section discusses the Branding-Competitiveness Index (BCI) on the two selected case studies: King Abdullah Economic City (KAEC) in Saudi Arabia and New Alamein City in Egypt. Both of these cities are large-scale urban expansions that are meant to be growth hubs within their own national planning frameworks: Saudi Vision 2030 and Egypt’s Fourth-Generation Cities Plan. These cities show how the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region is still changing. They are changing metropolitan regions from places that are only useful into places that are globally competitive and symbolically important. The research investigates how each city uses branding tactics, and measures for competitiveness. The case studies demonstrate the practical application of the adapted BCI and its capacity to reveal areas of convergence and tension between branding narratives and competitiveness indicators.

5.1. KAEC

5.1.1. Overview and Strategic Vision for KAEC

KAEC was opened in 2005 as one of Saudi Arabia’s main economic diversification projects. It is an example of a city that is established for a specific purpose to attract worldwide investment, talent, and tourism within the Saudi Vision 2030. KAEC was intended to be a competitive logistical and industrial hub on the Red Sea. Its branding approach is based on a blend of economic ambition, livability on the coast, and smart infrastructure. It focuses on themes of efficiency, innovation, and opportunity. The King Abdullah Port, the Industrial Valley, and the Marina District are all important parts of the city’s identity that serve as visual and functional catalysts [26]. KAEC’s administration is based on a model driven by the public–private partnership. This makes it easier to invest, but it also raises issues about how open it is to all users and how much they may participate. Despite strong marketing initiatives including digital platforms, international collaborations, and real estate marketing, there are still issues with making the city more lively. The city achieves comparatively higher scores in environmental sustainability and infrastructure, but there are concerns about cultural identity, community participation, and branding coherence [26,27].

5.1.2. Branding and Competitiveness Strategies Employed in KAEC

KAEC employs a branding approach that combines spatial, economic, and digital elements to create an image that is competitive on a global scale and fits with Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030. The city’s branding is based on the concept that it is a smart, high-performing, and investment-friendly city that is also a regional economic and logistical hub [27]. Innovation, connectivity, and economic opportunity are some of the main themes that make KAEC competitive, as well. In KAEC, spatial branding can be seen in the design and development of iconic neighborhoods like Bay La Sun and the Marina Promenade. These districts have mixed-use waterfront areas, branded real estate projects, and luxury residential neighborhoods. Architectural landmarks, improvements to public spaces, and environmental aesthetics are all used to give a sense of modernity and global sophistication. Marketing strategies focus on how easy it is to do business, the city’s high-quality infrastructure, and how well the city fits with national goals for economic change. The marketing strategies are based on the competitiveness of the city. At the same time, KAEC uses well-known international partners, like logistics companies, international schools, and hotel chains, to strengthen its image as a cosmopolitan and business-friendly place to visit. Therefore, the strategies employed in the city are trying to reach the balance between city branding and urban competitiveness [26,27].

5.2. New Alamein City

5.2.1. Overview and Strategic Vision for New Alamein City

The Egyptian government started building New Alamein City in 2018. This was a huge change in how Egypt builds cities along the coast. Instead of just small seasonal resorts, the government is now building full-scale, year-round metropolitan hubs. The New Urban Communities Authority (NUCA) oversees New Alamein, which is meant to be a fourth-generation smart city. Its goal is to reduce the pressure on the current metropolitan cities while encouraging sustainable expansion along the North Coast [28,29,30,31].

5.2.2. Branding and Competitiveness Strategies Employed in New Alamein City

New Alamein City is intended to be Egypt’s flagship smart city in the Mediterranean region by using a state-driven branding strategy that combines valuing heritage, developing the shore, and planning for the future. The city branding is based on three main aspects: cultural continuity, economic diversification, and tourism development. These aspects are employed by huge development projects that would bring in wealthy people from the home country, visitors from the region, and investors from around the world. The city’s branding strategy focuses on luxury tourism, cultural heritage, and educational innovation [28]. Examples of these aspects are the Alamein Towers, the Roman Theatre, and connections with colleges throughout the world. The city uses famous buildings and large waterfront constructions as branding tools to show that it is modern and important across the world. But governance is still quite centralized, with top-down planning frameworks that make it hard for people to get involved. When it comes to competitiveness, New Alamein does well in urban infrastructure and tourism-related services, but not so well in social cohesion, cultural identity, and administrative responsiveness. While the city benefits from solid physical planning and governmental investment, its long-term competitiveness rests on growing beyond symbolic megaprojects toward real community integration and localized branding distinctiveness [28,29].

5.3. Data Collection

A quantitative survey was based on the adapted BCI from the literature review and included 85 participants for KAEC and 79 participants for New Alamein. The survey targeted academics, researchers, and professionals in the field of urban planning and urban design. It comprises 22 questions across 6 sections. The first section includes general data about the profession, the highest level of education, and years of professional experience. The other sections included questions related to the 56 indicators stated in Table 1 before and asked to use 5 Likert scale for rating: (1 = Strongly Disagree—5 = Strongly Agree), by the end of each section there was an open-ended question to add any other parameters from their experiences in this field with its rated scale (1–5).

5.4. Results

The results in this section illustrate the findings derived from the application of the adapted BCI to the two selected case studies: KAEC and New Alamein City. Based on the data acquired from the secondary sources, expert evaluations, and SPSS statistical analysis, with reliability statistics Cronbach’s Alpha 0.978. The study quantified each city’s performance across the different indicators and subsequently across the five major categories: administrative, economic, social, environmental, and urban livability. The results analysis focuses on identifying the relative strengths, weaknesses, and interrelations among these categories and the 56 indicators, revealing how each city branding strategies contribute to its overall competitiveness.

5.4.1. SPSS Results on KAEC

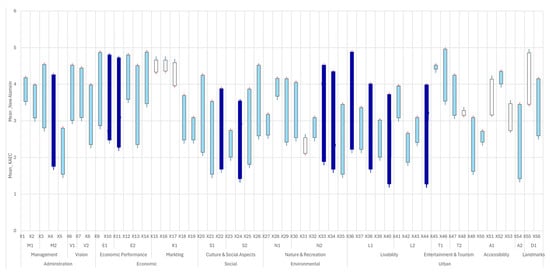

The SPSS analysis on KAEC illustrated relatively high mean scores across most categories of the adapted BCI. Figure 4 illustrates the results from the SSPS analysis. Based on the responses of 85 participants, the mean values ranged from 2.8 to 4.87, with standard deviations between 0.21 and 1.42. These ranges illustrate consistent expert agreement on the achievement of the city branding and urban competitiveness. KAEC has scored high average scores (M ≈ 4.2–4.5) in the administrative and economic categories. These results suggest perceived strengths in governance, institutional coordination, and investment climate. The framework for the city management, which is supported by Emaar, The Economic City, and Saudi Vision 2030, has facilitated the strategic planning for the city. Meanwhile, the city achieved moderate scores (M ≈ 3.0–3.5) in the social and cultural categories, showing progress in livability and service provision but alerting the limited local community engagement and the development of the cultural identity. The city branding is still on the institutional level and focuses on investment promotion and appealing lifestyle more than participatory development and enhancing the identity. Furthermore, the city scored strong in the Environmental and urban categories. The high mean scores in Sustainable Mobility (M = 4.87) and Infrastructure Readiness (M = 4.71) indicate the success of KAEC in achieving connectivity, accessibility, smart urban systems, and high environmental quality. Overall, KAEC illustrates high city branding coherence and urban competitiveness, particularly in the categories of economic, infrastructure, and environmental. However, the city branding relays towards the performance-based indicators, there is still less integration of cultural authenticity and local community participation.

Figure 4.

Mean—SPSS analysis for the BCI indicators in both cities, and dark blue stock indicators illustrate the gap between the cities, light blue stock indicators illustrate better performance for KAEC, and white stock indicators illustrate better performance for New Alamein City (source: the authors).

5.4.2. SPSS Results New Alamein City

The SPSS analysis on New Alamein City illustrated different performance levels across the indicator of the adapted BCI. Figure 4 and Table S1 illustrate the results from the SPSS analysis. Based on the responses of 79 participants in the survey, mean values ranged from 1.54 to 4.86, indicating moderate to strong performance overall, with relatively low variability across responses (SD = 0.35–1.37). New Alamein city in the administrative and economic categories achieved moderate mean scores (M ≈ 3.0–3.5), reflecting efficient institutional coordination but limited participatory governance and private-sector involvement. Economic diversification remains in its early phases, with most initiatives still driven by the government. On the other hand, the social and cultural categories illustrated weaker performance, specifically in the community engagement and cultural expression (M = 1.5–2.4). These scores suggest a potential gap between the rapid urban development and the social and community integration. On the contrast, the environmental and urban categories performed strongly, especially in the are of sustainable transportation and accessibility (M = 4.86), demonstrating progress in the urban mobility infrastructure and environmental considerations. However, lower scores in the indicators of pollution management and use of renewable energy indicate that the sustainability efforts are more of strategies and not yet implemented. Overall, New Alamein illustrates comparatively higher scores in the infrastructure, connectivity, and urban image-making but it still faces several challenges in the social cohesion, participatory branding, and long-term economic sustainability. Thus, while the city has succeeded in achieving a modern and sustainable city identity, further integration of cultural and community aspects may support balanced competitiveness.

6. Discussion

The comparative analysis outcomes of KAEC and New Alamein City indicate different approaches in the implementation of city branding and urban competitiveness strategies among growing cities in the MENA region. The Saudi Vision 2030 and Egypt’s Fourth-Generation Cities Initiative are two ambitious national plans that led to the establishment of these cities. Both cities aim at diversifying their economies and making them more visible across the world. The results show that both cities have relatively strong performance in infrastructure and environmental performance, but their social and cultural aspects are still not fully developed. The application of the BCI enables a clearer differentiation between symbolic dimensions of branding and structural determinants of competitiveness, addressing gaps in existing indices that treat these constructs separately.

KAEC illustrates a high level of institutional maturity and economic strategies, with most BCI indicators showing mean values of more than 4.0. The city branding success appears more oriented on combining economic utility, urban design, and digital visibility. The city’s port, industrial valley, and mixed-use waterfronts illustrate the city identity as a place where new ideas and smart investments can take place. These results support Rainisto’s (2003) [15] who claimed that the city branding works better when it is part of long-term economic plans and good governance. But the fact that local cultural stories and citizen involvement are not well considered shows that KAEC’s identity is mostly built from a top-down approach. This is in line with Kavaratzis and Kalandides’s (2015) [32] criticism that city branding which only relays on economic and aesthetic factors are more likely to be shallow, not sustainable and not connect with real place experiences. These observations align with literature suggesting that branding-led development may prioritize global competitiveness narratives over community-driven needs, raising questions about inclusivity and local relevance.

On the other hand, New Alamein City is at a developmental phase where the environment and infrastructure are doing well, but still the social inclusion and economic diversity are in their early phases. The results indicate that New Alamein branding is mostly based on symbolic megaprojects such as the Alamein Towers and the Roman Theatre. These kinds of projects make the area more visually appealing and tourist-friendly on the international level, but the long-term plans for the urban competitiveness remain unclear. Zenker, Braun and Petersen (2017) [33] discussed the “representation gap” in new urban brands, which is where city images, which are created by the governments, are more important than local community-based authenticity. This is the reason behind the low score of New Alamein in community engagement and cultural vitality. Despite this, the city high scores in sustainable mobility and accessibility indicate that the city model is well-connected and ecologically aware, which fits with global trends in green and resilient city branding, as per Gospodini (2019) [34].

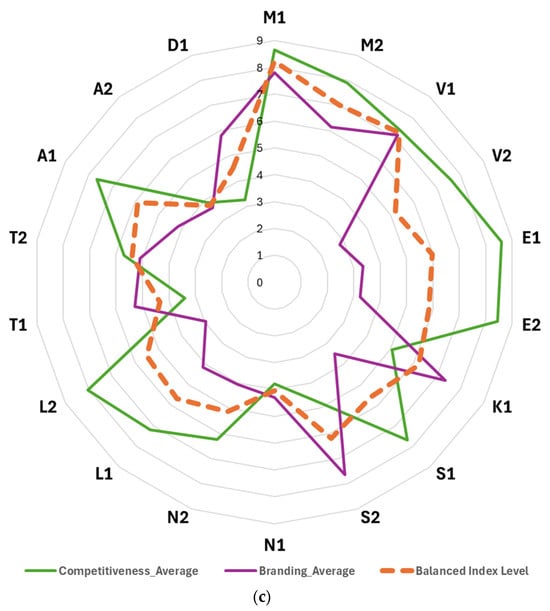

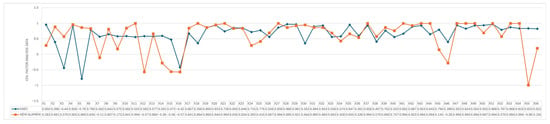

Comparative analysis between the two cities using component factor analysis (CFA) with the extraction method: principal component analysis, criteria mineigen (1) iterate (25)/extraction:pc/rotation:norotate/method = correlation. Three components extracted with full details of communalities, total variance explained, extraction sums of squared loadings in Tables S2 and S3. The results indicate a persistent regional issue: the disconnect between physical branding and social embedding, see Figure 5. Both KAEC and New Alamein achieved good branding through infrastructure, technical progress, and environmental design. However, both cities have trouble turning these assets into unified urban identities that are based on local culture. KAEC can be considered as a form of economic branding. In this model, urban competitiveness is based on market positioning, good governance, and collaborations with other countries. Meanwhile, New Alamein is an example of aesthetic branding, where visual representation and spatial design are more important than strategic communication. Both approaches help with short-term goals, but provide limited evidence of balanced integration of city branding and urban competitiveness as the adapted BCI framework suggests.

Figure 5.

Component factor analysis—SPSS—for the BCI indicators in KAEC and New Alamein City (source: authors).

The BCI advances beyond current city branding and urban competitiveness indices by integrating symbolic, perceptual, and structural indicators into a single analytical framework. Most of the existing indices—such as Anholt’s GMI, Rainisto’s success factors, or conventional competitiveness models—treat branding and competitiveness as conceptually separate domains, limiting their ability to capture the inter-connection between the image-making and performance-based development. The BCI addresses this segregation by simultaneously incorporating governance, economic restructuring, spatial identity, environmental performance, and social inclusion.

7. Conclusions

This study has developed a Branding–Competitiveness Index (BCI) that connects the theoretical frameworks with the practical aspects of city branding and urban competitiveness. The study utilized a multi-phase methodology that resulted in a multidimensional analytical framework for evaluating the impact of branding tactics on urban performance and identity creation. The adapted BCI has five principal categories: Administrative, Economic, Social, Environmental, and Urban. Within each category, there is a hierarchy of factors, sub-factors and indicators. This BCI includes both the symbolic and practical aspects of city growth. This provides a structured and adaptable basis for evaluating city branding and urban competitiveness in different contexts. The BCI offers a conceptual and analytical tool that is useful both in theory and in practice because it combines measurable aspects of competitiveness with perceptual and symbolic branding characteristics. It helps policymakers and urban planners make decisions based on facts by connecting branding goals to real-world results in cities. The framework also lets cities compare their accomplishments, find gaps, and change their strategy to make them more inclusive and resilient in terms of competitiveness.

The application of the BCI on two recently developed cities, KAEC in Saudi Arabia and New Alamein City in Egypt, illustrated how the framework can be applied to assess branding–competitiveness dynamics in emerging cities. The results highlighted that both cities did well in terms of infrastructure preparation, accessibility, and environmental quality. This indicates that government-led planning can lead to physical and economic change. Meanwhile, these case studies also illustrate that there are still challenges in the social and cultural aspects, where user involvement, local community participation, and the creation of local identity are still limited. While the study provided indicative insights into the two case studies, there were some limitations faced this study, including the analysis based mostly on secondary data and expert opinions. These are strong, but they may not fully show how people feel and what they have experienced in these new urban areas. With the limited population in both cities at the moment, it was hard to implement community survey.

The study highlights wider ramifications for urban design and development practices around the world. As cities throughout the world seek more branding and competitiveness that can be measured and enhanced based on this framework that connects image-making with structural performance. The BCI provides a framework for assessing the role of branding in fostering sustainable competitiveness in cities across diverse economic and cultural settings. The BCI framework helps build city brands that are more real, inclusive, and adaptable by encouraging a balance between visibility and viability to ensure long term plans and to act as a catalyst for sustainable urban development.

Finally, the study confirms that the most competitive cities of the future will not only be those that are economically successful or technologically advanced, but also those that can fit their urban image, cultural authenticity, and human experience into a branding framework that is both coherent and adaptable.

Future research should integrate multi-stakeholder surveys that involves residents, local businesses, governmental authorities, community associations and investors to capture the diverse perceptions of city branding and urban competitiveness. In addition, applying the BCI to cities beyond the MENA region—such as European, Asian, or Latin American contexts—would help in developing comparative analysis to assess its cross-cultural validity and reveal how governance structures, demographic profiles and socio-economic settings influence index performance. Comparative and longitudinal studies would also provide deeper insights into how city identities evolve over time and how city branding strategies influence, and are influenced by, long-term urban competitiveness performance. Moreover, integrating digital data sources—such as social media sentiment, mobility traces, and geospatial analytics—may also provide deeper insights into how urban image and lived experience intersect. Applying the BCI to different city typologies, including historic cities, post-industrial cities, and secondary urban centers, would further test its adaptability.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/architecture5040129/s1, Table S1: SPSS Analysis for the BCI indicators in both cities, Table S2: Component factor analysis for the BCI indicators in KAEC, Table S3: Component factor analysis for the BCI indicators in New Alamein City.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.H.A., A.A.-L. and T.E.; methodology, N.H.A., A.A.-L. and T.E.; software, N.H.A. and A.A.-L.; validation, N.H.A. and T.E.; formal analysis, N.H.A., A.A.-L. and T.E.; investigation, N.H.A., A.A.-L. and T.E.; resources, N.H.A., A.A.-L. and T.E.; data curation, N.H.A., A.A.-L. and T.E.; writing—original draft preparation, N.H.A., A.A.-L. and T.E.; writing—review and editing, N.H.A. and T.E.; visualization, N.H.A.; supervision, N.H.A., A.A.-L. and T.E.; project administration, N.H.A. and T.E.; funding acquisition, T.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

No funding is received for this research.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Effat university (RCI_REC/4.November.2025/7.1.Exp./58).

Informed Consent Statement

The surveys in this research were conducted online in an anonymous way. The survey didn’t collect any personal details, information, images, or videos that can relate to any person. Additionally, this phrase was included at the beginning of the survey: “Your participation is voluntary and anonymous, and all responses are confidential.”

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author(s) used ChatGPT5.1 for the purpose of refining the writing language. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BCI | Branding–Competitiveness Index |

| RW | Relative Weight |

| KAEC | King Abdullah Economic City |

| NUCA | New Urban Communities Authority |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for Social Sciences |

References

- Department of Economic and Social Affairs. World Urbanization Prospects; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2019; Available online: https://population.un.org/wup/assets/WUP2018-Highlights.pdf (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- Kotler, P.; Gertner, D. Chapter 3—A place marketing and place branding perspective revisited. In Destination Brands; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2011; pp. 33–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinnie, K. Contingent self-definition and amorphous regions: A dynamic approach to place brand architecture. Mark. Theory 2018, 18, 31–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshuis, J.; Edwards, A. Branding the City: The Democratic Legitimacy of a New Mode of Governance. Urban Stud. 2012, 50, 1066–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florek, M.; Hereźniak, M.; Augustyn, A. Measuring the effectiveness of city brand strategy. In search for a universal evaluative framework. Cities 2021, 110, 103079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboubakr, D.; ElSerafi, T. City Growth Challenges as a Dilemma between Urban Mobility and Livability: A Case Study of Heliopolis. Civ. Eng. Archit. 2023, 11, 1795–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElSerafi, T. Integrating Transit-Oriented Development in Historic Urban Districts: Enhancing Mobility and Preservation in ElMosky, Cairo. Civ. Eng. Archit. 2025, 13, 1326–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavaratzis, M. From city marketing to city branding: Towards a theoretical framework for developing city brands. Place Brand. 2004, 1, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julier, G. Urban Designscapes and the Production of Aesthetic Consent. Urban Stud. 2005, 52, 869–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P.; Gertner, D. Country as brand, product and beyond: A place marketing and brand management perspective. In Destination Branding; Routledge: London, UK, 2004; p. 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasapi, I.; Cela, A. Destination Branding: A Review of the City Branding Literature. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2017, 8, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hankinson, G. Location branding: A study of the branding practices of 12 English cities. J. Brand Manag. 2001, 9, 127–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldwell, N.; Freire, J.R. The Differences between Branding a Country, a Region and a City: Applying the Brand Box Model. J. Brand Manag. 2004, 12, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troisi, O.; Kashef, M.; Visvizi, A. Managing Safety and Security in the Smart City: COVID-19, Emergencies and Smart Surveillance. In Managing Smart Cities: Sustainability and Resilience Through Effective Management; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 73–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rainisto, S. Success Factors of Place Marketing: A Study of Place Marketing Practices in Northern Europe and the United States. Ph.D. Thesis, Helsinki University of Technology, Espoo, Finland, 2003. Available online: https://urn.fi/urn:nbn:fi:tkk-000746 (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Anholt, S. Competitive Identity: The New Brand Management for Nations, Cities and Regions; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenker, S.; Beckmann, S.C. My place is not your place—Different place brand knowledge by different target groups. J. Place Manag. Dev. 2013, 6, 6–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydoghmish, F.M.; Rafieian, M. Developing a comprehensive conceptual framework for city branding based on urban planning theory: Meta-synthesis of the literature (1990–2020). Cities 2022, 128, 103731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alganawi, A.; Ibrahim, A. The Role of Mayadeen (Roundabouts) in City Branding: The Case of Jeddah. In Proceedings of the Research and Innovation Forum 2023, Kraków, Greece, 12–14 April 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elserafi, T. Challenges for cycling and walking in new cities in Egypt, experience of Elsheikh Zayed City. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 2019, 66, 703–725. [Google Scholar]

- Kashef, M. Mixed-use and Street Network Attributes of Vibrant Urban Settings. Archit. Urban Plan. 2023, 19, 188–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komasi, H.; Zolfani, S.H.; Prentkovskis, O.; Skačkauskas, P. Urban Competitiveness: Identification and Analysis of Sustainable Key Drivers (A Case Study in Iran). Sustainability 2022, 14, 7844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruneckiene, J.; Guzavičius, A.; Činčikaitė, R. Measurement of Urban Competitiveness in Lithuania. Inz. Ekon.-Eng. Econ. 2010, 21, 493–509. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Hsu, L. The Influence of Dynamic Capability on Performance in the High Technology Industry: The Moderating Roles of Governance and Competitive Posture. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2010, 4, 562–577. Available online: https://academicjournals.org/journal/AJBM/article-abstract/D5BE35A22618 (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Du, Q.; Wang, Y.; Ren, F.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, H.; Wu, C.; Li, L.; Shen, Y. Measuring and Analysis of Urban Competitiveness of Chinese Provincial Capitals in 2010 under the Constraints of Major Function-Oriented Zoning Utilizing Spatial Analysis. Sustainability 2014, 6, 3374–3399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, S.; Swain, M.; Alkhabbaz, M. King Abdullah Economic City: Engineering Saudi Arabia’s post-oil future. Cities 2015, 45, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussa, R. King Abdullah Economic City: The Growth of New Sustainable City in Saudi Arabia. In New Cities and Community Extensions in Egypt and the Middle East; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Housing, Utilities and Urban Communities; General Organization for Physical Planning (GOPP). National Strategic Plan for Urban Development 2052; General Organization for Physical Planning (GOPP): Cairo, Egypt, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Attia, S. Al Alamein New City, a Sustainability Battle to Win. In New Cities and Community Extensions in Egypt and the Middle East; Attia, S., Shafik, Z., Ibrahim, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElSerafi, T.; Ben Aly, A. Fusing Smart Innovation and Human-Centered Design: A Livable Approach to Smart Sustainable District. Civ. Eng. Archit. 2025, 13, 2257–2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahar, A.; Ibrahim; Asmaa. Smart Cities or Smart People: The Role of Stakeholders to Achieve Integrative Vision. In Smart Cities for Sustainable Development. Advances in Geographical and Environmental Sciences; Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2022; pp. 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavaratzis, M.; Kalandides, A. Rethinking the place brand: The interactive formation of place brands and the role of participatory place branding. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2015, 47, 1368–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenker, S.; Braun, E.; Petersen, S. Branding the destination versus the place: The effects of brand complexity and identification for residents and visitors. Tour. Manag. 2017, 58, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gospodini, A. Urban design: The evolution of concerns, the increasing power, challenges and perspectives. J. Urban Des. 2019, 25, 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).