Abstract

Micro- and nanoplastics (MNPs) are a new type of pollutant that are widely present in terrestrial ecosystems due to agricultural plastics, sludge use, deposition, and litter degradation. Plants can absorb them through the soil and atmosphere, with adverse effects on plant growth and development. Several studies have reported the effects of MNPs on plant physiology, biochemistry, and toxicity. However, the food chain risk of plant uptake of MNPs has not been systematically studied. This review synthesizes current research on plant MNP pollution, focusing on the uptake and transport mechanisms of MNPs by plants, influencing factors, and health hazards. The size, type, and surface charge characteristics of MNPs, as well as environmental conditions, are key factors affecting MNP absorption and accumulation in plants. Furthermore, when MNP-enriched plants are consumed by humans and animals, the accumulated MNPs can diffuse through the bloodstream to various organs, impairing physiological functions and causing a range of health problems. While a comprehensive, traceable investigation of the transmission of MNPs through the terrestrial food chain remains unconfirmed, health risk signals are unequivocal—dietary intake is the primary route of human exposure to MNPs, with direct evidence of their bioaccumulation in human tissues. Addressing this critical research gap, i.e., systematically verifying the full terrestrial food chain translocation of MNPs, is therefore pivotal for conducting robust and comprehensive assessments of the food safety and health risks posed by MNPs. This study analyzed a total of 154 literature sources, providing important theoretical insights into the absorption, transport, and accumulation of MNPs in plants, as well as the health risks associated with their transfer to humans through the food chain. It is expected to provide valuable reference for the research on the transfer of MNPs in the “soil-plant-human” chain.

1. Introduction

Plastics have become one of the most widely used materials on Earth because of their versatility, durability, and relatively low cost. According to statistics, global annual plastic production has increased sharply from 2 to 400 million tons from 1950 to 2022 [1,2,3]. With the current trajectory, global demand for plastics is expected to double by 2050 [4,5,6,7]. However, the recycling rate of plastic waste is currently less than 10%, and approximately 80% of plastic waste accumulates in the natural environment [8,9,10]. These plastics are degraded into microplastics (MPs) and nanoplastics (NPs) through physical, chemical, or biological processes [11,12,13,14].

Nowadays, micro- and nanoplastic (MNP) pollution has spread worldwide. In the oceans [15,16,17], freshwater [18,19,20], soil [21,22], and atmosphere [23,24], MNPs are not only widely distributed in areas with intensive human activities but can also be found in remote regions such as the polar ice sheets in the Arctic and Antarctic and highland glaciers [25,26,27,28,29]. As plastics are primarily manufactured, used, and discharged on land, large amounts of MNPs have accumulated in terrestrial ecosystems. Their content is 4–23 times that of the marine environment, with terrestrial ecosystems becoming a huge reservoir of MNPs [30,31,32,33]. These MNPs are primarily classified into two categories based on their sources: primary and secondary. Primary MNPs are microscale particles directly generated during plastic production and application, such as plastic microbeads incorporated into personal care products and cosmetics [34,35] and microfibers shed from synthetic fiber garments during laundering [36]. In contrast, secondary MNPs are formed via the degradation and mechanical abrasion of MNP waste, including the decomposition of landfill-disposed plastics and residues of agricultural plastic mulches (its recovery rate after use is less than 60%, and a large amount of residues remain in the soil) [37,38,39].

In addition to the above sources, more than 90% of the MNPs in wastewater from sewage treatment plants are retained in sludge post-treatment, with the remainder discharged into the environment via effluent [40]. These sewage sludges are frequently utilized as soil conditioners or fertilizers in agricultural production and irrigation, thereby further exacerbating soil microplastic contamination [41,42]. Furthermore, MNPs can be released into the environment through tire wear [43,44,45], plastic turfs [46], and the abrasion of road marking materials [47,48].

Existing data have confirmed the severity of soil microplastic pollution. According to statistics, the arithmetic mean abundance of MPs in agricultural soils in mainland China is 2462 ± 3767 items/kg, and the median is 1416 items/kg [49]. Among 15 farmland soil samples collected in northern Germany, 379 MPs measuring 1–5 mm and weighing approximately 84 kg were identified [50]. According to Kedzierski et al. [51], the global microplastic inventory in agricultural soils may range from 1.5 to 6.6 million tons.

Notably, atmospheric deposition is also one of the important sources of MNPs in terrestrial environments [52,53]. Suspended MNPs within the atmospheric compartment can be translocated to terrestrial habitats (e.g., topsoil and vegetation canopies) via wet deposition (i.e., rainfall and snowfall) or dry deposition (i.e., gravitational sedimentation and aerosol impaction) [54]. Cross-regional studies provide substantial evidence of widespread atmospheric MNP deposition. In the Paris region, the daily deposition flux ranges from 2 to 355 particles/m2, with an annual cumulative deposition of up to 3–10 tons [55]. In central Indian cities, 87.84% of atmospherically deposited MNPs are fibrous, and the deposition flux is higher in summer (491.06 ± 73.37 particles/(m2·d)) [56]. In Hangzhou, the average flux of MNPs in atmospheric wet deposition is 9.2 items/(m2·min) [57]. Zhang et al. [58] compared the characteristics of MNP deposition across forest, agricultural, and residential areas in Beijing and found that the deposition flux is the highest in residential areas (395.07 ± 41.44 item/(m2·d)), followed by agricultural land (180.12 ± 42.22 item/(m2·d)), and the lowest in forests (133.18 ± 47.44 item/(m2·d)). These cross-regional studies indicate that the deposition of atmospheric MNPs is widespread in terrestrial ecosystems, and significant variations in their flux magnitude, particle morphology, and spatial distribution are primarily driven by regional climate, land-use types, and anthropogenic activity intensity.

More critically, as MNPs accumulate in terrestrial ecosystems over time, they can enter plants via soil and atmospheric transport and subsequently migrate to stems and leaves. MNPs accumulated in plants can lead to various physiological toxicities, including hindering plant growth, inhibiting photosynthesis, interfering with nutrient metabolism, inducing oxidative damage, and generating genotoxicity [59,60].

As core producers in ecosystems, plants serve as both the fundamental link in the food chain and a primary source of human food. MNPs migrate and accumulate in plants, tend to bioaccumulate along the food chain, and ultimately enter the human body, posing risks to human health [61]. Existing studies have demonstrated that MPs can induce inflammatory responses, cause vascular occlusion, and increase the risk of cardiovascular diseases [62]. In contrast, NPs, leveraging their ultra-small particle size advantage, can cross biological barriers such as the blood–brain barrier and the placenta to invade critical organs, including brain tissue and the reproductive system, with their potential hazards being more insidious and far-reaching [63,64,65,66,67].

Furthermore, MNPs possess physicochemical properties of a large specific surface area and strong adsorption capacity, rendering them prone to acting as “carriers” for various environmental pollutants (e.g., heavy metals, antibiotics, and persistent organic pollutants), leading to a more complex combined toxicity to human health [68]. Therefore, systematically investigating the plant migration mechanisms, food chain transmission dynamics, and composite toxicity effects of MNPs holds significant theoretical and practical value for the accurate assessment of human health risks.

This study reviews the uptake and transport mechanisms of MNPs in plants. It further explores the accumulation and distribution of MNPs in plants, as well as the factors that affect their uptake. In addition, the study discusses the food chain transfer risks of MNPs and their health impacts, aiming to improve the understanding of the harm caused by MNP pollution in terrestrial ecosystems and to provide a reference for scientifically evaluating the potential risks of MNP pollution.

2. Pathways of MNP Uptake by Plants

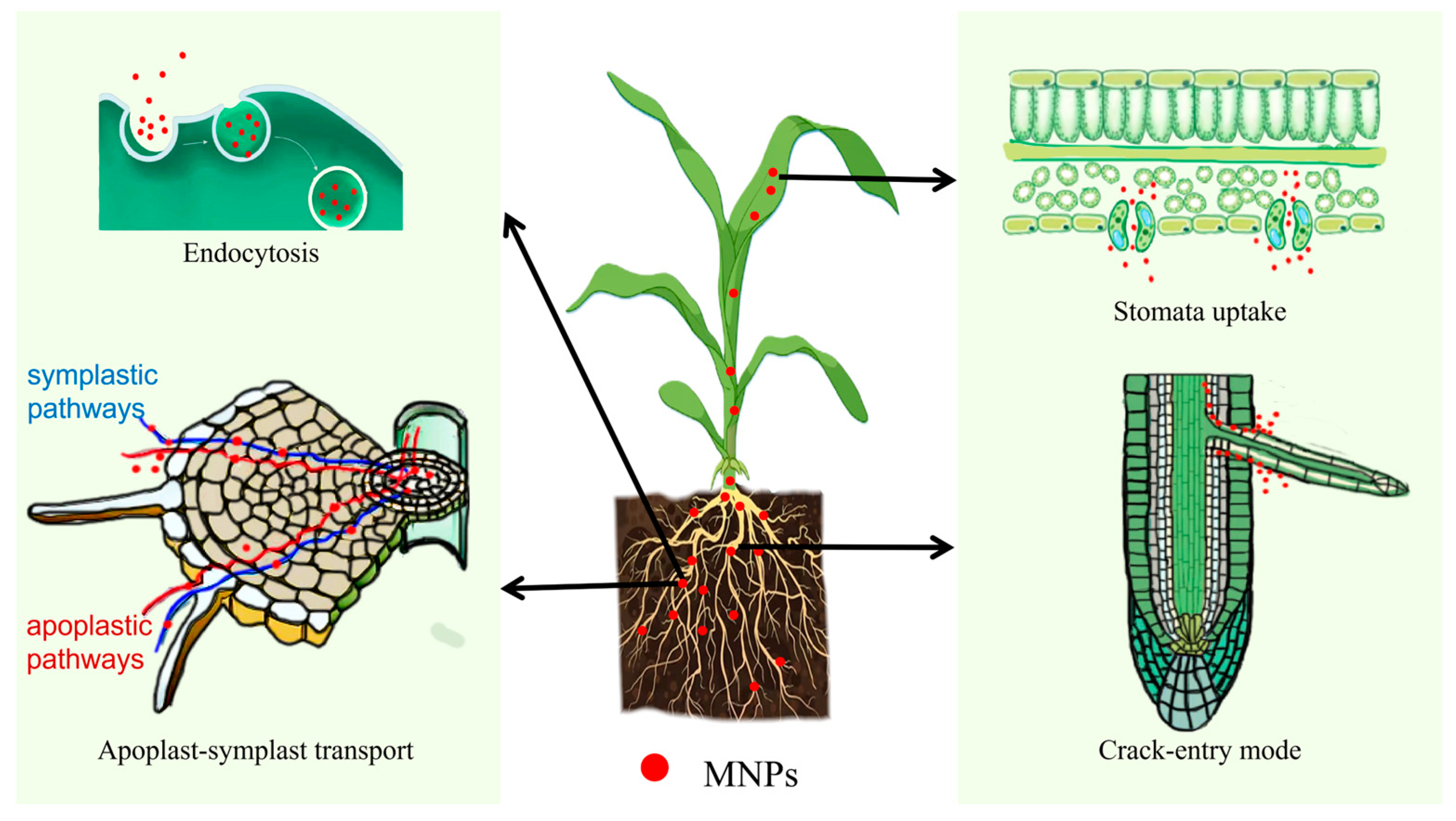

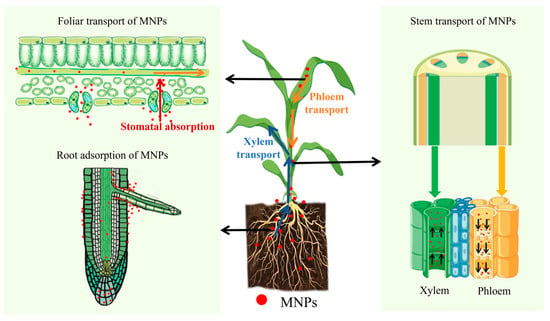

The transport and accumulation of MNPs in plants represent complex physiological processes. Advanced microscopic imaging techniques and mass spectrometry have facilitated the precise tracking and quantitative analysis of MNPs within plant tissues (Table 1). Current research demonstrates that the primary uptake and translocation mechanisms of MNPs in plants encompass endocytosis, membrane-mediated transport, epidermal crack penetration, and stomatal uptake [69] (Figure 1). This chapter aims to synthesize these mechanisms and their potential contributions to plant MNP acquisition, based on the latest scientific evidence and cumulative research outcomes.

Table 1.

Detection Techniques of MNPs in Plants.

Figure 1.

The uptake pathways of MNPs in plants.

2.1. Endocytosis

Endocytosis refers to the process by which cells form vesicles through the invagination of the plasma membrane and uptake of extracellular biological macromolecules, particulate substances, or liquids into the cell (Figure 1). Etxeberria et al. [78] cultured Sycamore (Acer pseudoplatanus) cells with fluorescently labeled MNPs. After 12 h, a large number of fluorescent signal spots were found in the vacuoles, indicating that the vacuoles were the final destination after the endocytosis of MNPs. It was confirmed that 40 nm polystyrene nanoplastics (PS-NPs) can be transported to the central vacuole via phagocytosis and subsequently absorbed by cultured cells. Bandmann et al. [79] also confirmed that tobacco BY-2 cells can take up 20 and 40 nm MNPS via endocytosis, whereas 100 nm beads do not enter the cell interior and attach to the cell wall without being endocytosed. Wu et al. [80] also observed plasma membrane invaginations, multivesicular bodies containing intraluminal vesicles, and aggregates of PS-NPs in rice (Oryza sativa L.) root cells exposed to 100 nm sized PS-NPs, but this finding was not observed in the 1 μm control group.

These phenomena reflect the dependence of cellular endocytosis on particle size. The diameter of the endocytic vesicles was <200 nm. Smaller nanoparticles are more likely to enter the cytoplasm, whereas larger nanoparticles are restricted to the cell surface. Endocytosis is the primary pathway for the uptake of relatively small MNPs [80].

2.2. Apoplast-Symplast Transport

There are two basic pathways by which plants absorb and transport MNPs—the apoplastic and symplastic pathways. The apoplast comprises cell walls, intercellular spaces, and vessels, and MNPs migrate towards the vascular bundles along the apoplastic pathway. The symplast is a continuum formed by the inter-connection of plant protoplasts through plasmodesmata and serves as a transport pathway between plant cells [81,82].

After entering through root hairs/epidermal cells, MNPs are simultaneously transported inward through both the apoplastic and symplastic pathways. When they reach the endodermis, they cannot directly enter the vascular cylinder and shift to the symplastic pathway because of the blockage of the Casparian strip in the cortical cell wall. With the help of plasmodesmata, MNPs can be transported to adjacent root cells, cross the cell membrane, enter the cytoplasm, and reach endodermal cells and vascular cylinders, finally reaching the xylem [83] (Figure 1). The presence of MNPs has been observed in the vascular systems of plants in previous studies. Based on the results of laser confocal scanning microscopy, Liu et al. [84] detected nano-sized (80 nm) and micro-sized (1 μm) MNPs in the roots, stems, and leaves of rice (Oryza sativa L.) seedlings. MNPs accumulate in the vascular systems of plant tissues, especially in the root columns, stem vascular bundles, and leaf veins, and mainly aggregate in cell walls and intercellular regions. Li et al. [85] observed aggregated MNPs (200 nm) in the cell walls and intercellular regions of the vascular systems and root cortical tissues of lettuce (Lactuca sativa).

2.3. Crack-Entry Mode

During lateral root germination, cracks form between the epidermal cells and lateral root sites. MNPs can enter plant root vessels at lateral root cracks, and under transpiration pull, they reach the plant’s stems, leaves, and other aboveground organs through the xylem (Figure 1). Li et al. [85] detected strong PS fluorescence signals in cracks in the lateral root zones (50–100 mm from the tip) of wheat (Triticum aestivum) and lettuce (Lactuca sativa), indicating that these cracks were the main entry points of root xylem MNPs in wheat (Triticum aestivum) and lettuce (Lactuca sativa). Confocal images of wheat (Triticum aestivum) cross-sections further suggested that MNPs entering through these cracks were mainly present within the vascular systems of the roots and stems.

2.4. Stomatal Absorption

Stomata are the main organs for gas exchange in terrestrial plants and are considered an effective way for MNPs to enter the mesophyll from the leaf surface. Under conditions of sufficient light, a good water supply, low CO2 concentration, suitable temperature, and high humidity, the stomata open, and MNPs that randomly land on the leaf surface enter the mesophyll from the leaf surface [86] (Figure 1). Lian et al. [87] showed that MNPs in air can accumulate on leaf surfaces through atmospheric deposition. Scanning electron microscopy of the leaf surface of lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) revealed that several PS-NPs aggregated around the stomata. Another study reported the uptake of PS-NPs (50–100 nm) by cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) leaves, with NPs clearly observed on the leaf surface and within leaf stomata [88]. These results indicate that stomatal absorption may be the main route for MNPs to enter the interior of leaves from the leaf surface. MNPs can enter stomata, move along the stomatal surface, and attach to the cell wall.

3. Transport and Accumulation of MNPs in Plants

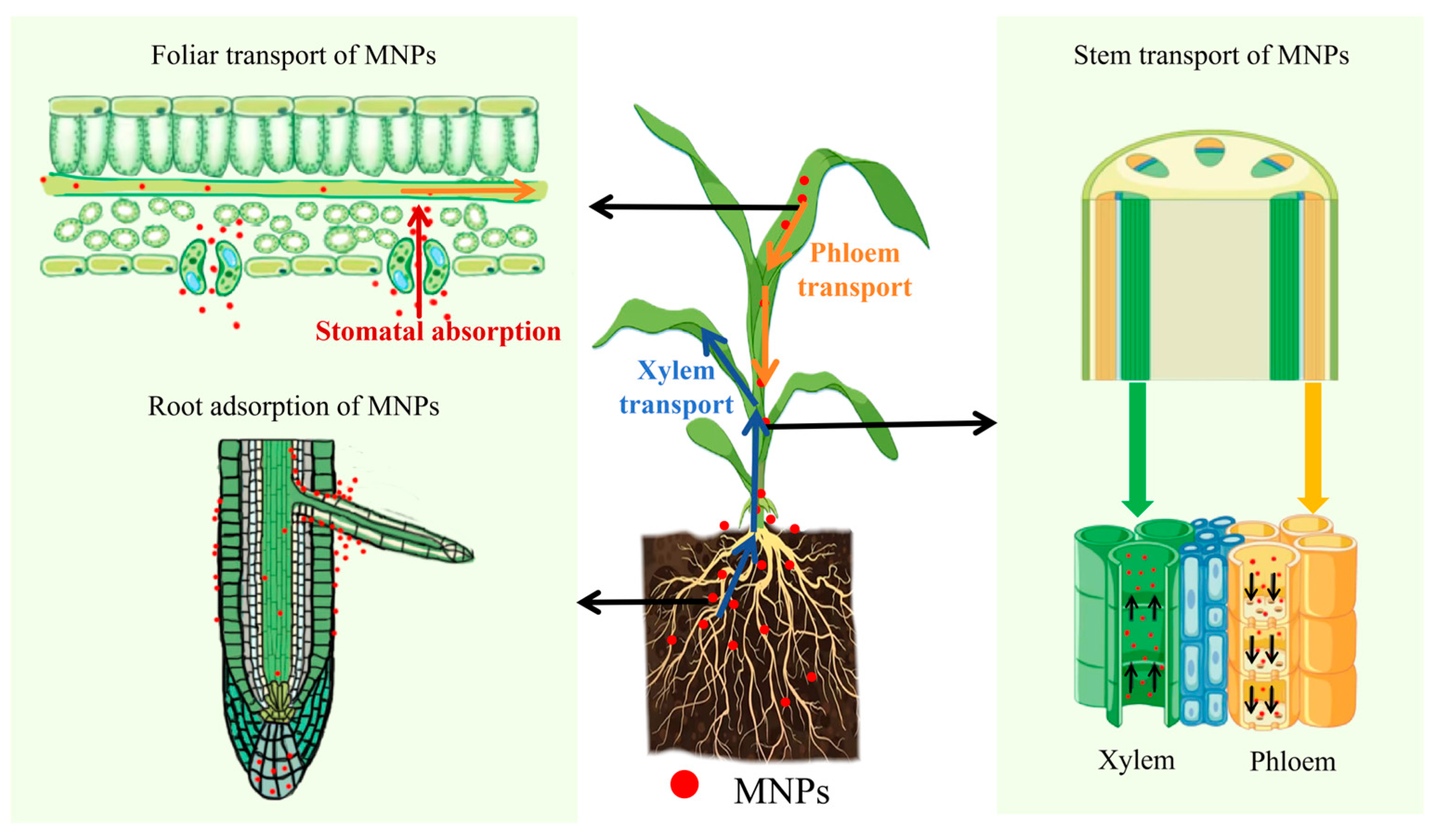

Plant roots are the “first barrier” to the entry of plants. Hartmann et al. [89] found that when plant roots were directly exposed to MNPs, the main sites of particle accumulation were the root cap, apical meristem, and differentiation zone. In addition, MNPs can enter the vascular bundles of root tissues and are transported from the roots to the stems and leaves via the xylem under transpiration pull [90] (Figure 2). The higher the transpiration rate (e.g., in high-temperature, low-humidity environments), the greater the absorption [82,84,91]. Liu et al. [84] observed nano-sized (80 nm) and micro-sized (1.0 μm) PS microspheres in the vascular systems of rice (Oryza sativa L.) roots, stems, and leaves. The results clearly demonstrate, for the first time, that nano- and micro-sized MPs can be absorbed by rice (Oryza sativa L.) roots and then transferred to the stems and leaves.

Figure 2.

The transport mechanisms of MNPs in plants.

As the upward transport distance increases, the migration of MNPs is hindered, and there are differences in their accumulation in different parts of the plant [85]. A large number of exposure experiments have confirmed that the quantity and mass concentration of MNPs absorbed and accumulated by plant roots increase with increasing MNP concentration and exposure time. The accumulation pattern in different parts of the plant was as follows: roots > leaves > stems [73,92,93].

Leaf absorption is an essential method by which plants accumulate atmospheric MNPs. MNPs appear in and around stomata through atmospheric deposition and are transported downward to stems and roots along with nutrients in the phloem [90] (Figure 2). A study by Li et al. [94] in 2025 showed that polyethylene terephthalate (PET) and polystyrene (PS) were the main types of MNPs in plant leaves, and their concentrations were positively correlated with the level of air pollution and leaf growth time. In highly polluted areas, such as polyester factories and landfills, PET and PS concentrations in plant leaves can reach 104 ng/g dry weight, whereas in open-field leafy vegetables, they are 102–103 ng/g dry weight, which is significantly higher than those in greenhouse-grown vegetables.

4. Factors Influencing the Uptake and Accumulation of MNPs in Plants

4.1. Size

The uptake and transport efficiency of MNPs in plants depend mainly on the particle size. Generally, the smaller the particle size, the easier it is for plants to absorb, and the greater the distribution in different tissues. Li et al. [95] found that PS-MNPs with smaller particle sizes (such as 0.2 μm) are more easily absorbed by maize (Zea mays) roots and are more widely distributed within the roots, being able to enter various tissues such as the epidermis, cortex, and xylem. In contrast, PS-MNPs with larger particle sizes (e.g., 5.0 μm) can hardly be absorbed by the roots. Jiang et al. [96] also found that 100 nm PS-MNPs can enter the roots of Vicia faba, whereas 5 μm PS-MPs accumulate on the root surface due to their larger volume. In a study on the impact of MNP particle size on rice (Oryza sativa L.), rice was found to have a certain enrichment capacity for PS-MNPs; the smaller the particle size and the higher the concentration, the greater the accumulated amount [97].

However, owing to the limitations of current detection techniques, there is no accurate conclusion regarding the maximum diameter of MNPs that plants can absorb and transport.

4.2. Type

Currently, the MNPs detected in the environment mainly include polyethylene (PE), polypropylene (PP), polyvinyl chloride (PVC), PS, etc. [90]. The chemical stability, surface functionalities, and degradation kinetics of MNPs are governed by their polymer compositions, which, in turn, exert divergent effects on the physiological and biochemical profiles of plants. Table 2 summarizes the effects of distinct MNP types across key plant growth and developmental stages. For instance, Liu et al. [98] validated that PE, PP, and PET collectively suppress pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) seed germination and seedling establishment, with PET exerting a more pronounced inhibitory effect on pepper seedlings relative to PE and PP—likely attributable to its superior chemical stability and attenuated degradation rate within plant tissues. Consistent with this observation, Shi et al. [99] reported that the adverse effects of PP on tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum L.) growth are less severe compared to PS and PE; PP-treated tomato plants mitigate oxidative damage by markedly enhancing antioxidant enzyme activities, thereby reducing the tissue burdens of malondialdehyde (MDA) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). These researchers attributed this type of dependency response to differences in the polymer skeletons or chemical structures.

Table 2.

The impact of microplastic types on plants.

The exposure duration of MNPs modulates their environmental behavior (e.g., aggregation and adsorption) and degradation dynamics, ultimately leading to time-dependent toxicological effects on crops. Pignattelli et al. [100] conducted controlled experiments using garden cress (L. sativum) as the model organism, exposing specimens to suspensions of PP, PE, PVC, and PE+PVC. Distinct toxicological phenotypes were observed across exposure paradigms: under acute exposure (6 days), PE and PE+PVC acted as primary stressors, significantly impairing seed germination and shoot elongation; in contrast, following chronic exposure (21 days), PP and PE dominated the toxicological outcomes, characterized predominantly by compromised seed germination and suppressed biomass accretion. Notably, the biomass of the acute exposure group did not exhibit a significant reduction and was even marginally higher than that of the control group, whereas the PE and PP treatment groups under chronic exposure displayed a substantial biomass decline—validating that long-term MNP exposure imposes a cumulative adverse impact on plant resource allocation and partitioning. Ma et al. [101] demonstrated in a study on rice (Oryza sativa L.) that 14-day PVC exposure induced significantly greater potential impairment to plant growth and metabolic cascades compared to PS; an additional investigation focusing on cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) photosynthetic physiology revealed that over a 74-day exposure period, PE and PS exerted more potent inhibitory effects on photosynthetic capacity than PVC, and the plasticizer dioctyl phthalate (DOP) synergistically exacerbated PS-induced damage to cucumber photosynthetic machinery [102].

In synthesis, the impacts of MNPs on crops are characterized by both type- and time-dependent effects—type-dependent effects are dictated by the inherent physicochemical attributes of MNPs, whereas time-dependent effects are intimately linked to the cumulative bioaccumulation of MNPs and their transformation products within plant tissues.

4.3. Surface Charge

The surface charge of MNPs affects their interactions with plants through electrostatic interactions, thereby influencing their absorption and transport by plants. Generally, amino-modified polystyrene (PS-NH2) is positively charged, while carboxyl-modified polystyrene (PS-COOH) is negatively charged.

When roots are exposed to MNPs with different charges, the negatively charged PS-COOH has a stronger ability to translocate from the roots to other tissues. In contrast, the positively charged PS-NH2 has more type- and time-dependent effects but has a lower translocation rate [103,104,105,106]. This study found that when the roots were exposed to MNPs with different charges, Arabidopsis thaliana absorbed and accumulated more negatively charged PS-COOH than positively charged PS-NH2 [103].

MNPs with different charges were adsorbed onto leaf surfaces. The positively charged PS-NH2 had stronger binding to the leaf surface and aggregation on the leaf surface. This aggregation hinders the movement of MNPs to the roots. This hindrance effect was more significant in PS-NH2. Sun et al. [107] showed that the overall mass of negatively charged PS-COOH attached to maize (Zea mays) leaves is lower than that of positively charged PS-NH2. After the same exposure time, the negatively charged PS-COOH in the vascular bundles had relatively smaller aggregate sizes than the positively charged PS-NH2, which is consistent with the results observed in the leaves. Consequently, the amount of PS–NH2 migrating into the roots was lower than that of PS-COOH. Wang et al. [105] detected higher levels of positively charged PS-NH2 in lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) leaves, and the number of accumulated MNPs increased with increasing exposure concentrations.

4.4. Soil Types and Environmental Conditions

Different soil types and environmental conditions can affect plant growth and physiological status. Clay has fine particles, small intergranular pores, high colloid content, and a large surface area, which easily adsorbs MNPs and makes them difficult to move. Sandy soil, owing to its large pores and good air permeability, allows MNPs to more easily penetrate the vicinity of plant roots along with water. Wang et al. [108] found that MNPs can significantly change the pore structure of soil, leading to the dispersion of pore spaces and blocking of connected large pores, thereby reducing soil porosity. The research results of Guo et al. [109] indicated that MNPs can change the pore size distribution of soil, reduce pore availability, and have a greater impact on clay.

In addition, light, carbon dioxide, temperature, and relative humidity can affect the opening and closing of leaf stomata, thus influencing the entry of MNPs into the plant mesophyll [86].

Soil often contains various pollutants, including pesticides, antibiotics, heavy metals, and organic pollutants. MNPs can adsorb and enrich these pollutants as carriers, thus forming a combined pollution system. This combined pollution may affect the uptake of MNPs by plants through synergistic or antagonistic effects and may trigger new toxic effects [110,111]. When soil is polluted by MNPs and heavy metals, the MNPs can promote the migration of heavy metals in the soil and change the properties of the soil and microbial community, thus affecting plants [112].

5. The Food Chain Transfer Risks of MNPs and Their Impacts on Human Health

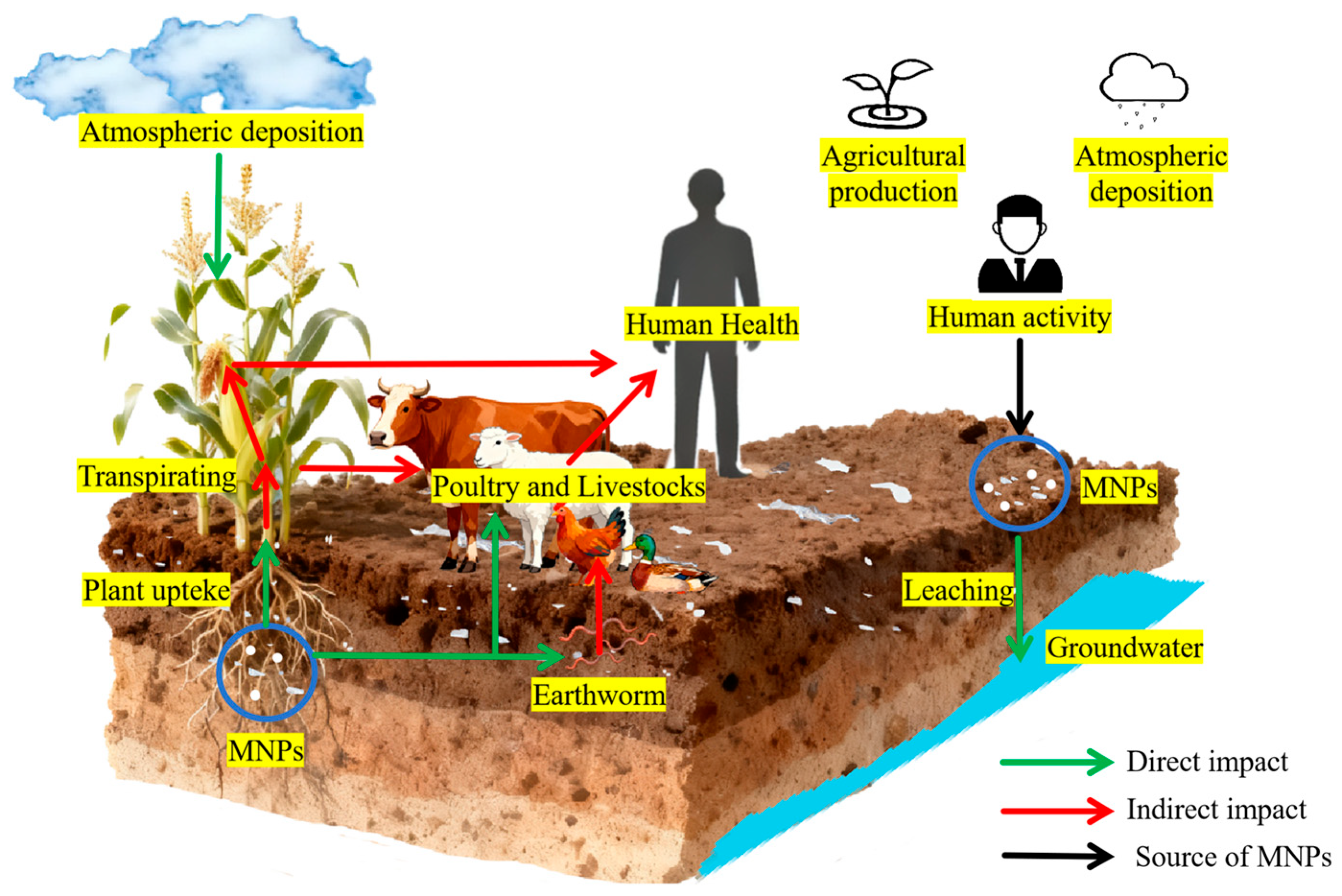

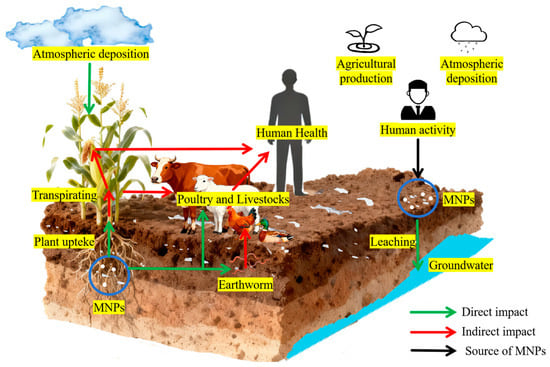

5.1. Transfer of MNPs in Plants to Humans Through the Food Chain

The MNPs in soil primarily originate from agricultural production, atmospheric deposition, and human activities. After these MNPs enter the soil, they may not only be absorbed by plant roots and transported to edible parts, but also directly ingested by soil animals such as earthworms. Subsequently, by feeding on contaminated plants or soil-dwelling animals, MNPs are further enriched in the bodies of terrestrial animals such as cattle and sheep and eventually transferred to humans along the food chain, posing potential risks to the entire ecosystem and human health (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Circulation and food chain transfer of MNPs in terrestrial ecosystems.

While the accumulation of MNPs in vegetables and fruits has been confirmed, and traces of MNPs have been detected in human samples, the tracking, identification, and quantitative analysis of MNPs in organisms remain extremely challenging, and the cumulative amount of MNPs entering the human body through the dietary pathway remains unclear to date. While the complete transmission path of MNPs in the terrestrial food chain has not been verified by traceability studies, their potential health risk signals are already clear. To address these gaps and clarify the potential threats posed by MNPs, it is necessary to conduct systematic analyses and verifications of the specific transmission processes of MNPs within the terrestrial food chain. Given the lack of direct data supporting current food-chain transmission processes, advancing this research direction will lay a foundation for clarifying the environmental migration laws and health risks associated with MNPs.

5.1.1. Primary Producers → Human

As primary producers, plants are the starting points of the food chain and of MNPs entering the food chain. Plants adsorb MNPs from the soil and atmosphere via their roots and leaves. After consuming plants or plant-derived foods containing MNPs, the accumulated MNPs are ingested (Figure 3). The accumulation of MNPs in plants such as lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) [113], water spinach (Ipomoea aquatica F.) [93,114], Vicia faba [96], onion (Allium cepa L.) [115], peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.), and rice (Oryza sativa L.) [116] has been confirmed. Oliveri Conti et al. [117] first detected MNPs (<10 μm) in vegetables (B. oleracea italic, Lactuca sativa, Daucus carota, and Solanum tuberosum) and fruits (Malus domestica and Pyrus communis), and the concentration in fruits was higher than that in the edible parts of vegetables.

5.1.2. Primary Producers → Consumers → Humans

In addition to directly consuming primary producers, humans ingest MNPs via livestock (e.g., cattle, sheep, pigs, and chickens) that consume them. After these animals ingest plants or feed containing MNPs through digestion and absorption, MNPs accumulate in their digestive tracts, liver, and other tissues. When humans consume animal-derived products (meat, meat products, eggs, and dairy products), MNPs can be ingested indirectly (Figure 3). Studies have detected MNPs in edible tissues (i.e., liver, meat, and tripe) of livestock (cows and sheep) [118].

Emerging evidence indicates the presence of MNPs in the human body, with particles in the 20–100 μm size range accounting for the highest proportion (>70%) in tissues such as bone marrow, placenta, and semen [119,120,121]. Owing to the limitations in the sensitivity and selectivity of existing detection technologies, the efficient separation and accurate identification of nanoscale MNPs remain technical bottlenecks, potentially leading to underestimation of their actual exposure levels in the human body [122].

In terms of morphology, MNPs in the human body are mainly of three types—spherical, irregular fragments, and fibrous. Fibrous MNPs are frequently detected in respiratory and digestive tract samples. This phenomenon is directly related to the fact that MNPs enter the human body mainly via inhalation and ingestion [123,124].

In terms of chemical composition, PE, PS, PVC, PET, and PP are the main polymer types detected in the human body, with a cumulative proportion exceeding 70% [119,120,121,125]. These polymers are widely used in the production and manufacture of daily necessities, including food packaging, textiles, and medical devices. Their application scenarios are highly consistent with the characteristics of high-frequency contact in daily human life, which also provides an important material basis for MNPs to enter the human body via various pathways [126,127].

5.2. The Impact of MNPs on Human Health

5.2.1. Distribution of MNPs in the Human Body

MNPs can enter multiple links of the food chain via multiple media, such as soil, water bodies, and the atmosphere, and are gradually transmitted and accumulated in humans. Studies have identified traces of MNPs in human tissues, and their distribution and potential impact on the human body have become a key focus of attention.

In the circulatory system, Leslie et al. [125] detected MNPs in whole-blood samples from 22 healthy volunteers at an average total concentration of 1.6 µg/mL. This study demonstrated that MNPs can enter the human circulatory system and be transported to various organs via the bloodstream, providing key evidence for subsequent studies on organ-level pollution.

In the digestive system, the gastrointestinal tract is the main accumulation site for ingested MNPs, and pollution is particularly prominent. Özsoy et al. [124] first confirmed the presence of MNPs in human gastric tissue. In addition, other research teams have detected various MNPs in human fecal and colon tissue samples [128,129]. Further, intestinal organoid experiments revealed that MNPs can accumulate in intestinal epithelial cells, suggesting that they may directly affect intestinal epithelial cell function. Notably, as an essential metabolic organ, MNPs were directly detected in liver tissues from patients with liver cirrhosis, but not in healthy livers. There may be two explanations for this difference—healthy livers may have the ability to clear MNPs; in contrast, it may also be due to the limitations of the detection methods that cannot capture extremely low concentrations of MNPs in healthy livers [130].

In the reproductive system, Ragusa et al. [119] used Raman Microspectroscopy to examine the placentas of six healthy pregnant women. The results showed that MNPs were detected in the placentas of four of the women, with sizes ranging from 5 to 10 μm. This study is the first to demonstrate that MNPs can cross the placental barrier and enter the fetal environment, potentially posing risks to normal fetal development. In addition, other studies have detected MNPs in human testes and semen, suggesting that MNPs may adversely affect male reproductive function [121].

In the motor system, Guo et al. [120] analyzed 16 human bone marrow samples and found that MNPs were detected in all samples, with an average concentration as high as 51.28 µg/g. As the core organ of human hematopoiesis, the bone marrow is widely contaminated by MNPs, suggesting that they may threaten hematopoietic function and thereby affect blood cell production and function.

Furthermore, a 2025 study published in Nature Medicine has expanded the understanding of the distribution of MNPs in the human body—this study confirmed that MNPs are widely present in the human liver, kidneys, and brain, the with the concentration of MNPs in the brain being 7–30 times that in the liver or kidneys. Notably, a significantly greater number of MNPs was detected in brain samples from patients with dementia [66]. This association provides a new research direction for exploring potential links between MNPs and neurological diseases.

5.2.2. Diseases That May Be Caused by MNPs and Their Degradation Products

The impact of MNPs on human health is inferred from in vivo exposure experiments. These experiments have been validated using animal models (such as mice [131], zebrafish [132], rainbow trout [133], and earthworms [134]), in vitro models (such as human cell cultures), and organoid experiments (such as brain [135], heart [136], kidney [137], intestinal [138], and liver [139] organoids). It has been demonstrated that MNPs and their degradation products can damage multiple human systems through various toxic mechanisms, thereby triggering multisystem diseases and health risks.

In the circulatory system, MNPs in the blood are phagocytosed by immune cells, which then block capillaries in the cerebral cortex, increasing the risk of thrombosis [140]. Marfella et al. [141] detected MNPs in carotid plaques and their content was positively correlated with the risk of myocardial infarction and stroke, suggesting that MNPs may be involved in the occurrence and development of atherosclerosis. In addition, the accumulation of MNPs in heart tissue can cause inflammation and oxidative stress, thereby increasing the risk of heart attack and stroke [142].

In the digestive system, after entering the human body, MNPs are deposited on the surfaces of tissues and organs, including the gastrointestinal and respiratory tracts. They can cause mucosal inflammation and epithelial cell damage, and even disrupt the intestinal barrier through mechanisms such as mechanical friction and physical obstruction [143]. Additionally, they can disrupt the balance of intestinal flora, trigger metabolic disorders, and cause liver inflammation and abnormal lipid metabolism, resulting in hepatic fat accumulation and hepatocyte damage [139,144].

In the respiratory system, inhaled MNPs deposit in the alveoli and induce inflammatory reactions. Long-term exposure may lead to respiratory diseases such as asthma and pneumoconiosis [145]. Occupational exposure to specific types of PVC is associated with an increased risk of lung cancer [146].

When the reproductive system is affected, MNPs can damage the structure and function of the testes, reduce the quantity and quality of sperm, and ultimately decrease male fertility [147]. The ovaries and uterus play important roles in female reproduction, serving as sites for egg production and embryonic development, respectively. Long-term exposure to MNPs can reduce the number of antral follicles and the quality of oocytes, as well as induce uterine inflammation, leading to reproductive dysfunctions such as pelvic inflammatory disease, endometriosis, and recurrent miscarriages, and can even cause fetal growth restriction [148,149,150]. These results demonstrate the potential toxicity of MNPs in human reproductive organs and provide a basis for understanding the effects of plastic pollution on human reproductive health.

In the nervous system, MNPs can inhibit acetylcholinesterase activity, affect neural signal transmission, induce abnormal motor behavior, impair learning and memory, and trigger local immune responses, thereby triggering neuroinflammation [151]. Long-term neuroinflammation has been proven to be closely related to the occurrence of neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease [152].

Plastics often contain additives, such as plasticizers, phthalates, bisphenol A, and other chemical substances, added during production. These additives have endocrine-disrupting effects and can alter endocrine and immune functions, as well as metabolic processes [153]. Endocrine disruptors, which mimic or antagonize hormones in the human body, lead to hormonal imbalances that affect normal growth, development, and reproductive health [154].

6. Conclusions

This review establishes that MNPs are taken up by plants via four primary pathways—endocytosis, apoplastic–symplastic transport, crack entry, and stomatal absorption—followed by intraplant translocation and selective accumulation. Notably, root tissues exhibit substantially higher MNP accumulation levels compared to aboveground organs, reflecting a distinct spatial distribution pattern of MNPs in plants. The bioaccumulation of MNPs is jointly modulated by intrinsic particle physicochemical properties (e.g., dimensional characteristics, material composition, and surface charge) and extrinsic environmental factors (e.g., soil texture and nutrient composition, ambient temperature, and moisture regime). These findings significantly advance our mechanistic understanding of the behavior of MNPs in terrestrial food webs, explicitly identifying plants as a pivotal entry point mediating the biomagnification of MNPs across successive trophic levels. Moreover, the established “environment-plant-human” migration framework provides a robust theoretical scaffold for quantitatively predicting the environmental fate and transport dynamics of MNPs in agricultural ecosystems.

The existing literature has confirmed that MNPs can accumulate in edible plant tissues and may subsequently migrate to animals and humans via the food chain. This phenomenon has raised widespread concerns about food safety. Critically, MNPs can traverse physiological barriers, leading to their bioaccumulation in key organs, including the brain, gastrointestinal tract, heart, kidneys, and liver. Such organ-specific enrichment subsequently induces multifaceted multisystem impairments, thereby exerting cascading adverse effects on human growth, development, and reproductive health.

In summary, agricultural stakeholders and policymakers must consider the contamination of MNPs when developing soil management practices and food safety regulations, particularly given the potential for oxidative stress, chronic inflammation, and organ damage in consumers. Although current research has established a basic framework for the migration and risks of MNPs in terrestrial plants, critical knowledge gaps remain: (1) field-applicable detection methods for MNPs in plants must be developed; (2) the effects of naturally occurring, morphologically diverse MNPs on plant uptake require investigation; and (3) multi-trophic level experiments are needed to quantify biomagnification effects and establish comprehensive risk assessment frameworks for the “soil-plant-human” contamination pathway.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.R., X.W. and Z.X.; methodology, L.R. and J.Z.; formal analysis, L.R. and L.L.; investigation, L.R. and J.Z.; data curation, L.R. and Y.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, L.R.; writing—review and editing, L.R., X.W. and Q.S.; visualization, L.R.; supervision, Y.Z. and L.L.; project administration, X.W., Z.X. and Q.S.; funding acquisition, X.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Xinjiang Autonomous Region Nature Fund Project, grant number 2023D01A113.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors of this paper declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Plastics Europe. Plastics—The Fast Facts 2024; Plastics Europe: Brussels, Belgium, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Houssini, K.; Li, J.; Tan, Q. Complexities of the global plastics supply chain revealed in a trade-linked material flow analysis. Commun. Earth Environ. 2025, 6, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayanathara Thathsarani Pilapitiya, P.G.C.; Ratnayake, A.S. The world of plastic waste: A review. Clean. Mater. 2024, 11, 100220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stegmann, P.; Daioglou, V.; Londo, M.; van Vuuren, D.P.; Junginger, M. Plastic futures and their CO2 emissions. Nature 2022, 612, 272–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dokl, M.; Copot, A.; Krajnc, D.; Fan, Y.V.; Vujanović, A.; Aviso, K.B.; Tan, R.R.; Kravanja, Z.; Čuček, L. Global projections of plastic use, end-of-life fate and potential changes in consumption, reduction, recycling and replacement with bioplastics to 2050. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2024, 51, 498–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Roijen, E.; Miller, S.A. Leveraging biogenic resources to achieve global plastic decarbonization by 2050. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 7659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pottinger, A.S.; Geyer, R.; Biyani, N.; Martinez, C.C.; Nathan, N.; Morse, M.R.; Liu, C.; Hu, S.; de Bruyn, M.; Boettiger, C.; et al. Pathways to reduce global plastic waste mismanagement and greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. Science 2024, 386, 1168–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geyer, R.; Jambeck, J.R.; Law, K.L. Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1700782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nature, S. Plastics pollution is surging—The planned UN treaty to curb it must be ambitious. Nature 2025, 643, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Walker, T.R. Plastic recycling: A panacea or environmental pollution problem. Npj Mater. Sustain. 2024, 2, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, R.C.; Olsen, Y.; Mitchell, R.P.; Davis, A.; Rowland, S.J.; John, A.W.G.; McGonigle, D.; Russell, A.E. Lost at Sea: Where Is All the Plastic? Science 2004, 304, 838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frias, J.P.G.L.; Nash, R. Microplastics: Finding a consensus on the definition. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 138, 145–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, K.L.; Thompson, R.C. Microplastics in the seas. Science 2014, 345, 144–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, S.; Reemtsma, T. Things we know and don’t know about nanoplastic in the environment. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2019, 14, 300–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiba, S.; Saito, H.; Fletcher, R.; Yogi, T.; Kayo, M.; Miyagi, S.; Ogido, M.; Fujikura, K. Human footprint in the abyss: 30 year records of deep-sea plastic debris. Mar. Policy 2018, 96, 204–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, M.; Tekman, M.B.; Gutow, L. Sea change for plastic pollution. Nature 2017, 544, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, M.; Jiang, Y.; Kwong, R.W.M.; Brar, S.K.; Zhong, H.; Ji, R. How do humans recognize and face challenges of microplastic pollution in marine environments? A bibliometric analysis. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 280, 116959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thacharodi, A.; Meenatchi, R.; Hassan, S.; Hussain, N.; Bhat, M.A.; Arockiaraj, J.; Ngo, H.H.; Le, Q.H.; Pugazhendhi, A. Microplastics in the environment: A critical overview on its fate, toxicity, implications, management, and bioremediation strategies. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 349, 119433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanton, T.; Johnson, M.; Nathanail, P.; MacNaughtan, W.; Gomes, R.L. Freshwater microplastic concentrations vary through both space and time. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 263, 114481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liu, H.; Paul Chen, J. Microplastics in freshwater systems: A review on occurrence, environmental effects, and methods for microplastics detection. Water Res. 2018, 137, 362–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dissanayake, P.D.; Kim, S.; Sarkar, B.; Oleszczuk, P.; Sang, M.K.; Haque, M.N.; Ahn, J.H.; Bank, M.S.; Ok, Y.S. Effects of microplastics on the terrestrial environment: A critical review. Environ. Res. 2022, 209, 112734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nizzetto, L.; Langaas, S.; Futter, M. Pollution: Do microplastics spill on to farm soils? Nature 2016, 537, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Li, H.-X.; Lin, L.; Pan, Y.-F.; Liu, S.; Hou, R.; Xu, X.-R. Occurrence and human exposure risks of atmospheric microplastics: A review. Gondwana Res. 2022, 108, 200–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahal, Y.; Babel, S. Atmospheric Microplastics Analysis: Discrepancies, Issues, and Way Forward. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2025, 237, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Gao, T.; Kang, S.; Shi, H.; Mai, L.; Allen, D.; Allen, S. Current status and future perspectives of microplastic pollution in typical cryospheric regions. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2022, 226, 103924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Kang, S.; Wang, Z.; Luo, X.; Guo, J.; Gao, T.; Chen, P.; Yang, C.; Zhang, Y. Microplastic characteristic in the soil across the Tibetan Plateau. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 828, 154518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeken, I.; Primpke, S.; Beyer, B.; Gütermann, J.; Katlein, C.; Krumpen, T.; Bergmann, M.; Hehemann, L.; Gerdts, G. Arctic sea ice is an important temporal sink and means of transport for microplastic. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Su, J.; Xiong, X.; Wu, X.; Wu, C.; Liu, J. Microplastic pollution of lakeshore sediments from remote lakes in Tibet plateau, China. Environ. Pollut. 2016, 219, 450–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, S.; Allen, D.; Phoenix, V.R.; Le Roux, G.; Durántez Jiménez, P.; Simonneau, A.; Binet, S.; Galop, D. Atmospheric transport and deposition of microplastics in a remote mountain catchment. Nat. Geosci. 2019, 12, 339–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Ji, J.; Tao, J.; Yang, Y.; Wu, D.; Han, L.; Li, S.; Wang, J. Current advances in interactions between microplastics and dissolved organic matters in aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2023, 158, 116882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, A.A.; Walton, A.; Spurgeon, D.J.; Lahive, E.; Svendsen, C. Microplastics in freshwater and terrestrial environments: Evaluating the current understanding to identify the knowledge gaps and future research priorities. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 586, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uwamungu, J.Y.; Wang, Y.; Shi, G.; Pan, S.; Wang, Z.; Wang, L.; Yang, S. Microplastic contamination in soil agro-ecosystems: A review. Environ. Adv. 2022, 9, 100273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; S, S.; Sachdev, S.; Sahoo, K.S.; Ambade, B.; Bauddh, K. Microplastic pollution in agricultural environments: Origins, impacts, and mitigation strategies. Phys. Chem. Earth Parts A/B/C 2025, 138, 103866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Ren, S.-Y.; Ni, H.-G. Incidence of microplastics in personal care products: An appreciable part of plastic pollution. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 742, 140218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giustra, M.; Sinesi, G.; Spena, F.; De Santes, B.; Morelli, L.; Barbieri, L.; Garbujo, S.; Galli, P.; Prosperi, D.; Colombo, M. Microplastics in Cosmetics: Open Questions and Sustainable Opportunities. ChemSusChem 2024, 17, e202401065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Periyasamy, A.P.; Tehrani-Bagha, A. A review on microplastic emission from textile materials and its reduction techniques. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2022, 199, 109901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrovic, M.; Mihajlovic, I.; Tubic, A.; Novakovic, M. Microplastics in municipal solid waste landfills. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Health 2023, 31, 100428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Liu, Q.; Jia, W.; Yan, C.; Wang, J. Agricultural plastic mulching as a source of microplastics in the terrestrial environment. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 260, 114096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Hu, Z.; Wu, F.; Guo, K.; Gu, F.; Cao, M. The Use and Recycling of Agricultural Plastic Mulch in China: A Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.W.; Chen, L.B.; Mei, Q.Q.; Dong, B.; Dai, X.H.; Ding, G.J.; Zeng, E.Y. Microplastics in sewage sludge from the wastewater treatment plants in China. Water Res. 2018, 142, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christian, A.E.; Koper, I. Microplastics in biosolids: A review of ecological implications and methods for identification, enumeration, and characterization. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 864, 161083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bläsing, M.; Amelung, W. Plastics in soil: Analytical methods and possible sources. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 612, 422–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kole, P.J.; Lohr, A.J.; Van Belleghem, F.G.A.J.; Ragas, A.M.J. Wear and Tear of Tyres: A Stealthy Source of Microplastics in the Environment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Os, M.F.; Nooijens, M.G.A.; van Renesse van Duivenbode, A.; Tromp, P.C.; Höppener, E.M.; Grigoriadi, K.; Boersma, A.; Parker, L.A. Degradation rates and ageing effects of UV on tyre and road wear particles. Chemosphere 2025, 372, 144121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Järlskog, I.; Jaramillo-Vogel, D.; Rausch, J.; Gustafsson, M.; Strömvall, A.-M.; Andersson-Sköld, Y. Concentrations of tire wear microplastics and other traffic-derived non-exhaust particles in the road environment. Environ. Int. 2022, 170, 107618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Haan, W.P.; Quintana, R.; Vilas, C.; Cózar, A.; Canals, M.; Uviedo, O.; Sanchez-Vidal, A. The dark side of artificial greening: Plastic turfs as widespread pollutants of aquatic environments. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 334, 122094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burghardt, T.E.; Pashkevich, A. Road markings and microplastics—A critical literature review. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2023, 119, 103740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burghardt, T.E.; Pashkevich, A.; Babić, D.; Mosböck, H.; Babić, D.; Żakowska, L. Microplastics and road markings: The role of glass beads and loss estimation. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2022, 102, 103123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.Y.; Yu, L.; Li, Y.J.; Han, B.J.; Zhang, J.D.; Tao, S.; Liu, W.X. Spatial Distributions, Compositional Profiles, Potential Sources, and Intfluencing Factors of Microplastics in Soils from Different Agricultural Farmlands in China: A National Perspective. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 16964–16974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harms, I.K.; Diekötter, T.; Troegel, S.; Lenz, M. Amount, distribution and composition of large microplastics in typical agricultural soils in Northern Germany. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 758, 143615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kedzierski, M.; Cirederf-Boulant, D.; Palazot, M.; Yvin, M.; Bruzaud, S. Continents of plastics: An estimate of the stock of microplastics in agricultural soils. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 880, 163294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Xu, A.; Shi, M.; Su, Y.; Liu, W.; Zhang, Y.; She, Z.; Xing, X.; Qi, S. Atmospheric deposition is an important pathway for inputting microplastics: Insight into the spatiotemporal distribution and deposition flux in a mega city. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 341, 123012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Kang, S.; Allen, S.; Allen, D.; Gao, T.; Sillanpää, M. Atmospheric microplastics: A review on current status and perspectives. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2020, 203, 103118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, D.; Chu, X.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Liao, Z.; Ji, X.; Ju, J.; Yang, B.; Chen, Z.; Dahlgren, R.; et al. Micro- and nano-plastics in the atmosphere: A review of occurrence, properties and human health risks. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 465, 133412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dris, R.; Gasperi, J.; Saad, M.; Mirande, C.; Tassin, B. Synthetic fibers in atmospheric fallout: A source of microplastics in the environment? Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2016, 104, 290–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prajapati, A.; Jadhao, P.; Kumar, A.R. Atmospheric microplastics deposition in a central Indian city: Distribution, characteristics and seasonal variations. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 374, 126183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, L.; Huang, W.; Ye, X.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yu, M.; Li, J.; Yoo, H.; Jeon, K.-J.; Li, W. Atmospheric microplastics in rainfalls in the megacity of Hangzhou: Morphology, composition, and deposition flux. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 386, 127301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Jia, X.; Wang, K.; Lu, L.; Li, F.; Li, J.; Xu, L. Characteristics, sources and influencing factors of atmospheric deposition of microplastics in three different ecosystems of Beijing, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 883, 163567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Cui, Q.; Chen, L.; Zhu, X.; Zhao, S.; Duan, C.; Zhang, X.; Song, D.; Fang, L. A critical review of microplastics in the soil-plant system: Distribution, uptake, phytotoxicity and prevention. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 424, 127750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, M.; Huang, Y.; Liu, L.; Ren, L.; Li, C.; Yang, R.; Zhang, Y. The effects of Micro/Nano-plastics exposure on plants and their toxic mechanisms: A review from multi-omics perspectives. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 465, 133279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, J.; Li, H.; Liu, P.; Zhang, Z.; Ouyang, Z.; Guo, X. Review of the toxic effect of microplastics on terrestrial and aquatic plants. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 791, 148333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlov, M. Landmark study links microplastics to serious health problems. Nature 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopatz, V.; Wen, K.; Kovacs, T.; Keimowitz, A.S.; Pichler, V.; Widder, J.; Vethaak, A.D.; Holloczki, O.; Kenner, L. Micro- and Nanoplastics Breach the Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB): Biomolecular Corona’s Role Revealed. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Yang, H.; Niu, S.; Guo, M.; Xue, Y. Mechanisms of micro- and nanoplastics on blood-brain barrier crossing and neurotoxicity: Current evidence and future perspectives. NeuroToxicology 2025, 109, 92–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurub, R.E.; Bainbridge, S.; Rahman, L.; Halappanavar, S.; El-Chaâr, D.; Wade, M.G. Particulate contamination of human placenta: Plastic and non-plastic. Environ. Adv. 2024, 17, 100555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nihart, A.J.; Garcia, M.A.; El Hayek, E.; Liu, R.; Olewine, M.; Kingston, J.D.; Castillo, E.F.; Gullapalli, R.R.; Howard, T.; Bleske, B.; et al. Bioaccumulation of microplastics in decedent human brains. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 1114–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, Y.; Wu, S.; Wei, G. Adverse effects of microplastics and nanoplastics on the reproductive system: A comprehensive review of fertility and potential harmful interactions. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 903, 166258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, H. Adsorption of antibiotics on microplastics. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 237, 460–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Z.; Xu, X.; Guo, L.; Jin, R.; Lu, Y. Uptake and transport of micro/nanoplastics in terrestrial plants: Detection, mechanisms, and influencing factors. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 907, 168155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Y.; Hu, R.; Zheng, Y.; Ding, L.; Qiu, X.; Yang, J.; Liang, X.; Guo, X. Sampling, extraction, and analysis of micro- and nano-plastics in environmental and biological compartments: A review. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2025, 183, 118056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, Z.; Ma, S.; Ouyang, Z.; Liu, P.; Qiang, H.; Guo, X. The review of nanoplastics in plants: Detection, analysis, uptake, migration and risk. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2023, 158, 116889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Luo, Y.; Peijnenburg, W.J.G.M.; Li, R.; Yang, J.; Zhou, Q. Confocal measurement of microplastics uptake by plants. MethodsX 2020, 7, 100750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Gao, Y.; He, S.; Chi, H.-Y.; Li, Z.-C.; Zhou, X.-X.; Yan, B. Quantification of Nanoplastic Uptake in Cucumber Plants by Pyrolysis Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2021, 8, 633–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Q.; Wu, Y.; Liu, W.; Ma, X.; He, D.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Wu, W. Identification and quantification of nanoplastics in different crops using pyrolysis gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Chemosphere 2024, 354, 141689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.-Q.; Lu, C.-H.; Mai, L.; Bao, L.-J.; Liu, L.-Y.; Zeng, E.Y. Response of rice (Oryza sativa L.) roots to nanoplastic treatment at seedling stage. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 401, 123412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Li, L.; Feng, Y.; Li, R.; Yang, J.; Peijnenburg, W.J.G.M.; Tu, C. Quantitative tracing of uptake and transport of submicrometre plastics in crop plants using lanthanide chelates as a dual-functional tracer. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2022, 17, 424–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Lamana, J.; Marigliano, L.; Allouche, J.; Grassl, B.; Szpunar, J.; Reynaud, S. A Novel Strategy for the Detection and Quantification of Nanoplastics by Single Particle Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS). Anal. Chem. 2020, 92, 11664–11672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Etxeberria, E.; Gonzalez, P.; Baroja-Fernández, E.; Romero, J.P. Fluid Phase Endocytic Uptake of Artificial Nano-Spheres and Fluorescent Quantum Dots by Sycamore Cultured Cells. Plant Signal. Behav. 2006, 1, 196–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandmann, V.; Mueller, J.D.; Koehler, T.; Homann, U. Uptake of fluorescent nano beads into BY2-cells involves clathrin-dependent and clathrin-independent endocytosis. FEBS Lett. 2012, 586, 3626–3632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Liu, W.; Zeb, A.; Lian, J.; Sun, Y.; Sun, H. Polystyrene microplastic interaction with Oryza sativa: Toxicity and metabolic mechanism. Environ. Sci. Nano 2021, 8, 3699–3710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Chen, H.; Shen, M.; Tao, J.; Chen, S.; Yin, L.; Zhou, W.; Wang, X.; Xiao, R.; Li, R. Recent advances on the transport of microplastics/nanoplastics in abiotic and biotic compartments. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 438, 129515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Ben, Y.; Che, R.; Peng, C.; Li, J.; Wang, F. Uptake, transport and accumulation of micro- and nano-plastics in terrestrial plants and health risk associated with their transfer to food chain—A mini review. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 902, 166045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maity, S.; Guchhait, R.; Sarkar, M.B.; Pramanick, K. Occurrence and distribution of micro/nanoplastics in soils and their phytotoxic effects: A review. Plant Cell Environ. 2022, 45, 1011–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Guo, R.; Zhang, S.; Sun, Y.; Wang, F. Uptake and translocation of nano/microplastics by rice seedlings: Evidence from a hydroponic experiment. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 421, 126700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Luo, Y.; Li, R.; Zhou, Q.; Peijnenburg, W.J.G.M.; Yin, N.; Yang, J.; Tu, C.; Zhang, Y. Effective uptake of submicrometre plastics by crop plants via a crack-entry mode. Nat. Sustain. 2020, 3, 929–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driesen, E.; Van den Ende, W.; De Proft, M.; Saeys, W. Influence of Environmental Factors Light, CO2, Temperature, and Relative Humidity on Stomatal Opening and Development: A Review. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, J.; Liu, W.; Meng, L.; Wu, J.; Chao, L.; Zeb, A.; Sun, Y. Foliar-applied polystyrene nanoplastics (PSNPs) reduce the growth and nutritional quality of lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.). Environ. Pollut. 2021, 280, 116978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, D.; Shi, Z.; Shan, X.; Yang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, X. Insights into growth-affecting effect of nanomaterials: Using metabolomics and transcriptomics to reveal the molecular mechanisms of cucumber leaves upon exposure to polystyrene nanoplastics (PSNPs). Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 866, 161247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartmann, G.F.; Ricachenevsky, F.K.; Silveira, N.M.; Pita-Barbosa, A. Phytotoxic effects of plastic pollution in crops: What is the size of the problem? Environ. Pollut. 2022, 292, 118420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, Q.; Cui, J.; Jin, B. Environmental microplastics: Classification, sources, fates, and effects on plants. Chemosphere 2023, 313, 137559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Li, Q.; Li, R.; Zhou, J.; Wang, G. The distribution and impact of polystyrene nanoplastics on cucumber plants. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 16042–16053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, S.; Zeng, Y.; Chen, Y.; Liu, H.; Yan, X.; Pu, S. A new quantitative insight: Interaction of polyethylene microplastics with soil-Microbiome-Crop. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 460, 132302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Du, A.; Ge, T.; Li, G.; Lian, X.; Zhang, S.; Hu, C.; Wang, X. Accumulation modes and effects of differentially charged polystyrene nano/microplastics in water spinach (Ipomoea aquatica F.). J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 480, 135892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Xu, L.; Li, R.; Zhang, R.; Li, M.; Ran, C.; Rao, Z.; Wei, X.; Chen, M.; et al. Leaf absorption contributes to accumulation of microplastics in plants. Nature 2025, 641, 666–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Chang, X.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhong, R.; Wang, L.; Wei, J.; Wang, Y. Uptake and distribution of microplastics of different particle sizes in maize (Zea mays) seedling roots. Chemosphere 2023, 313, 137491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, X.; Chen, H.; Liao, Y.; Ye, Z.; Li, M.; Klobučar, G. Ecotoxicity and genotoxicity of polystyrene microplastics on higher plant Vicia faba. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 250, 831–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, X.; Wang, W.; Zhu, L. Size-dependent effects of polystyrene micro- and nanoplastics on the quality of rice grains and the metabolism mechanism. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 382, 126463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, G.; Wang, S.; Feng, F.; Huang, J.; Wang, M.; Rong, S.; Zhao, H.; Su, S.; Liu, W. Risks of microplastics on germination and growth of pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) depending on the type, concentration, and particle size. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2025, 40, 104385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, R.; Liu, W.; Lian, Y.; Zeb, A.; Wang, Q. Type-dependent effects of microplastics on tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum L.): Focus on root exudates and metabolic reprogramming. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 859, 160025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pignattelli, S.; Broccoli, A.; Renzi, M. Physiological responses of garden cress (L. sativum) to different types of microplastics. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 727, 138609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Aqeel, M.; Khalid, N.; Nazir, A.; Alzuaibr, F.M.; Al-Mushhin, A.A.M.; Hakami, O.; Iqbal, M.F.; Chen, F.; Alamri, S.; et al. Effects of microplastics on growth and metabolism of rice (Oryza sativa L.). Chemosphere 2022, 307, 135749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, H.; Li, Z.; Wang, M.; Liu, B.; Chu, Y.; Lin, Z. Effects of microplastics and combined pollution of polystyrene and di-n-octyl phthalate on photosynthesis of cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.). Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 947, 174426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.-D.; Yuan, X.-Z.; Jia, Y.; Feng, L.-J.; Zhu, F.-P.; Dong, S.-S.; Liu, J.; Kong, X.; Tian, H.; Duan, J.-L.; et al. Differentially charged nanoplastics demonstrate distinct accumulation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2020, 15, 755–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Lu, S.; Guo, L.; Wang, P.; He, C.; Liu, D.; Bian, H.; Sheng, L. Effects of polystyrene nanoplastics with different functional groups on rice (Oryza sativa L.) seedlings: Combined transcriptome, enzymology, and physiology. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 834, 155092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Xiang, L.; Wang, F.; Wang, Z.; Bian, Y.; Gu, C.; Wen, X.; Kengara, F.O.; Schäffer, A.; Jiang, X.; et al. Positively Charged Microplastics Induce Strong Lettuce Stress Responses from Physiological, Transcriptomic, and Metabolomic Perspectives. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 16907–16918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, G.; Chen, M.; Wang, W.; Liu, W.; Liao, H.; Li, Z.; Wang, J. The direct effects of micro- and nanoplastics on rice and wheat. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2024, 180, 117976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Lei, C.; Xu, J.; Li, R. Foliar uptake and leaf-to-root translocation of nanoplastics with different coating charge in maize plants. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 416, 125854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, J.; Qu, Z.; Ayurzana, B.; Zhao, G.; Li, W. Effects of microplastics on the pore structure and connectivity with different soil textures: Based on CT scanning. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2024, 36, 103791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Li, P.; Yang, X.; Wang, Z.; Lu, B.; Chen, W.; Wu, Y.; Li, G.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, G.; et al. Soil texture is an important factor determining how microplastics affect soil hydraulic characteristics. Environ. Int. 2022, 165, 107293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.R.; Ulhassan, Z.; Li, G.; Lou, J.; Iqbal, B.; Salam, A.; Azhar, W.; Batool, S.; Zhao, T.; Li, K.; et al. Micro/nanoplastics: Critical review of their impacts on plants, interactions with other contaminants (antibiotics, heavy metals, and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons), and management strategies. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 912, 169420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.; Zhang, Y.; Hussain, N.; Lan, T.; Chen, G.; Tang, X.; Deng, O.; Yan, C.; Li, Y.; Luo, L.; et al. A bibliometric analysis of global research hotspots and progress on microplastics in soil-plant systems. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 341, 122890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Cui, G.; Jin, Q.; Liu, J.; Dong, Y. Effects of microplastics on the uptake and accumulation of heavy metals in plants: A review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 111812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, Z.; Zhang, T.; Luo, J.; Bai, H.; Ma, S.; Qiang, H.; Guo, X. Internalization, physiological responses and molecular mechanisms of lettuce to polystyrene microplastics of different sizes: Validation of simulated soilless culture. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 462, 132710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.; Liao, H.; Junaid, M.; Chen, X.; Kong, C.; Wang, Q.; Pan, T.; Chen, G.; Wang, X.; Wang, J. Polystyrene nanoplastics’ accumulation in roots induces adverse physiological and molecular effects in water spinach Ipomoea aquatica Forsk. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 872, 162278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maity, S.; Chatterjee, A.; Guchhait, R.; De, S.; Pramanick, K. Cytogenotoxic potential of a hazardous material, polystyrene microparticles on Allium cepa L. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 385, 121560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Wang, B.; Ye, R.; Yu, N.; Xie, Z.; Hua, Y.; Zhou, R.; Tian, B.; Dai, S. Evidence and Impacts of Nanoplastic Accumulation on Crop Grains. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, 2202336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveri Conti, G.; Ferrante, M.; Banni, M.; Favara, C.; Nicolosi, I.; Cristaldi, A.; Fiore, M.; Zuccarello, P. Micro- and nano-plastics in edible fruit and vegetables. The first diet risks assessment for the general population. Environ. Res. 2020, 187, 109677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahrani, F.; Mohammadi, A.; Dobaradaran, S.; De-la-Torre, G.E.; Arfaeinia, H.; Ramavandi, B.; Saeedi, R.; Tekle-Röttering, A. Occurrence of microplastics in edible tissues of livestock (cow and sheep). Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 22145–22157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ragusa, A.; Svelato, A.; Santacroce, C.; Catalano, P.; Notarstefano, V.; Carnevali, O.; Papa, F.; Rongioletti, M.C.A.; Baiocco, F.; Draghi, S.; et al. Plasticenta: First evidence of microplastics in human placenta. Environ. Int. 2021, 146, 106274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X.; Wang, L.; Wang, X.; Li, D.; Wang, H.; Xu, H.; Liu, Y.; Kang, R.; Chen, Q.; Zheng, L.; et al. Discovery and analysis of microplastics in human bone marrow. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 477, 135266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Zhu, L.; Weng, J.; Jin, Z.; Cao, Y.; Jiang, H.; Zhang, Z. Detection and characterization of microplastics in the human testis and semen. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 877, 162713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridgeman, L.; Pamies, D.; Frangiamone, M. Human organoids to assess environmental contaminants toxicity and mode of action: Towards New Approach Methodologies. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 497, 139562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, A.S.; Cherubini, A.; Rusconi, F.; Santo, N.; Madaschi, L.; Pistoni, C.; Moschetti, G.; Sarnicola, M.L.; Crosti, M.; Rosso, L.; et al. Human airway organoids and microplastic fibers: A new exposure model for emerging contaminants. Environ. Int. 2022, 163, 107200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özsoy, S.; Gündogdu, S.; Sezigen, S.; Tasalp, E.; Ikiz, D.A.; Kideys, A.E. Presence of microplastics in human stomachs. Forensic Sci. Int. 2024, 364, 112246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leslie, H.A.; van Velzen, M.J.M.; Brandsma, S.H.; Vethaak, A.D.; Garcia-Vallejo, J.J.; Lamoree, M.H. Discovery and quantification of plastic particle pollution in human blood. Environ. Int. 2022, 163, 107199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan Anik, A.; Hossain, S.; Alam, M.; Binte Sultan, M.; Hasnine, M.D.T.; Rahman, M.M. Microplastics pollution: A comprehensive review on the sources, fates, effects, and potential remediation. Environ. Nanotechnol. Monit. Manag. 2021, 16, 100530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-Y.; Chia, R.W.; Veerasingam, S.; Uddin, S.; Jeon, W.-H.; Moon, H.S.; Cha, J.; Lee, J. A comprehensive review of urban microplastic pollution sources, environment and human health impacts, and regulatory efforts. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 946, 174297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, Y.S.; Tuan Anuar, S.; Azmi, A.A.; Wan Mohd Khalik, W.M.A.; Lehata, S.; Hamzah, S.R.; Ismail, D.; Ma, Z.F.; Dzulkarnaen, A.; Zakaria, Z.; et al. Detection of microplastics in human colectomy specimens. JGH Open Open Access J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 5, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, F.; Ren, H.; Zhang, Y. Analysis of Microplastics in Human Feces Reveals a Correlation between Fecal Microplastics and Inflammatory Bowel Disease Status. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 414–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvatits, T.; Tamminga, M.; Liu, B.; Sebode, M.; Carambia, A.; Fischer, L.; Püschel, K.; Huber, S.; Fischer, E.K. Microplastics detected in cirrhotic liver tissue. eBioMedicine 2022, 82, 104147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallapaty, S. Microplastics block blood flow in the brain, mouse study reveals. Nature 2025, 638, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, R.; Deng, Y.; Zhang, S.; Wolosker, M.B.; Zhu, Q.; Ren, H.; Zhang, Y. Accumulation of different shapes of microplastics initiates intestinal injury and gut microbiota dysbiosis in the gut of zebrafish. Chemosphere 2019, 236, 124334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdile, N.; Cattaneo, N.; Camin, F.; Zarantoniello, M.; Conti, F.; Cardinaletti, G.; Brevini, T.A.L.; Olivotto, I.; Gandolfi, F. New Insights in Microplastic Cellular Uptake Through a Cell-Based Organotypic Rainbow-Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) Intestinal Platform. Cells 2025, 14, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, X.; Wang, Z.; Liu, L.; Wang, D.; Gu, Y.; Chen, L.; Chen, X.; Meng, Z. The combined effects of azoxystrobin and different aged polyethylene microplastics on earthworms (Eisenia fetida): A systematic evaluation based on oxidative damage and intestinal function. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 923, 171494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, F.; You, H.; Tang, X.; Su, Y.; Peng, H.; Li, H.; Wei, Z.; Hua, J. Early-life exposure to polypropylene nanoplastics induces neurodevelopmental toxicity in mice and human iPSC-derived cerebral organoids. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2025, 23, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Wu, Q.; Li, Y.; Feng, Y.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, W. Low-dose of polystyrene microplastics induce cardiotoxicity in mice and human-originated cardiac organoids. Environ. Int. 2023, 179, 108171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Wang, Y.; Xue, Q.; Yao, J.; Chen, L.; Feng, S.; Shao, J.; Guo, Z.; Zhou, B.; Xie, J. Polystyrene microplastics disrupt kidney organoid development via oxidative stress and Bcl-2/Bax/caspase pathway. Chem.-Biol. Interact. 2025, 419, 111642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Z.; Meng, R.; Chen, G.; Lai, T.; Qing, R.; Hao, S.; Deng, J.; Wang, B. Distinct accumulation of nanoplastics in human intestinal organoids. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 838, 155811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.; Li, X.; Zhou, Y.; Yu, H.; Xie, Y.; Guo, H.; Wang, H.; Li, Y.; Feng, Y.; Wang, Y. Polystyrene microplastics induce hepatotoxicity and disrupt lipid metabolism in the liver organoids. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 806, 150328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H.; Hou, J.; Li, M.; Wei, F.; Liao, Y.; Xi, B. Microplastics in the bloodstream can induce cerebral thrombosis by causing cell obstruction and lead to neurobehavioral abnormalities. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eadr8243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marfella, R.; Prattichizzo, F.; Sardu, C.; Fulgenzi, G.; Graciotti, L.; Spadoni, T.; D’Onofrio, N.; Scisciola, L.; La Grotta, R.; Frigé, C.; et al. Microplastics and Nanoplastics in Atheromas and Cardiovascular Events. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 390, 900–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Wang, C.; Duan, X.; Liang, B.; Genbo Xu, E.; Huang, Z. Micro- and nanoplastics: A new cardiovascular risk factor? Environ. Int. 2023, 171, 107662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Li, H.; Wang, J.; Wu, B.; Guo, X. Polystyrene microplastics aggravate inflammatory damage in mice with intestinal immune imbalance. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 833, 155198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva Brito, W.A.; Mutter, F.; Wende, K.; Cecchini, A.L.; Schmidt, A.; Bekeschus, S. Consequences of nano and microplastic exposure in rodent models: The known and unknown. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2022, 19, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.C.; Saha, G. Effect of microplastics deposition on human lung airways: A review with computational benefits and challenges. Heliyon 2024, 10, e24355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Halimu, G.; Zhang, Q.; Song, Y.; Fu, X.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, H. Internalization and toxicity: A preliminary study of effects of nanoplastic particles on human lung epithelial cell. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 694, 133794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, W.; Yuan, Y.; Tian, Y.; Cheng, C.; Chen, Y.; Zeng, L.; Yuan, Y.; Li, D.; Zheng, L.; Luo, T. Oral exposure to polystyrene nanoplastics reduced male fertility and even caused male infertility by inducing testicular and sperm toxicities in mice. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 454, 131470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, G.; Xiong, S.; Jing, Q.; van Gestel, C.A.M.; van Straalen, N.M.; Roelofs, D.; Sun, L.; Qiu, H. Maternal exposure to polystyrene nanoparticles retarded fetal growth and triggered metabolic disorders of placenta and fetus in mice. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 854, 158666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, X.; Cao, M.; Peng, T.; Shan, H.; Lian, W.; Yu, Y.; Shui, G.; Li, R. Features, Potential Invasion Pathways, and Reproductive Health Risks of Microplastics Detected in Human Uterus. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 10482–10493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhuan, Q.; Zhang, L.; Meng, L.; Fu, X.; Hou, Y. Polystyrene microplastics induced female reproductive toxicity in mice. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 424, 127629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, K.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, H.; Wang, D.; Guo, M.; Mu, M.; Liu, Y.; Nie, X.; Li, B.; Li, J.; et al. A comparative review of microplastics and nanoplastics: Toxicity hazards on digestive, reproductive and nervous system. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 774, 145758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, P.; Wang, F.; Xi, G.; Li, Y.; Wang, F.; Wang, H.; Li, L.; Ma, X.; Han, Y.; Shi, Y. Association of microplastics in human cerebrospinal fluid with Alzheimer’s disease-related changes. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 494, 138748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burgos-Aceves, M.A.; Abo-Al-Ela, H.G.; Faggio, C. Physiological and metabolic approach of plastic additive effects: Immune cells responses. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 404, 124114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bostan, N.; Ilyas, N.; Akhtar, N.; Mehmood, S.; Saman, R.U.; Sayyed, R.Z.; Shatid, A.A.; Alfaifi, M.Y.; Elbehairi, S.E.I.; Pandiaraj, S. Toxicity assessment of microplastic (MPs); a threat to the ecosystem. Environ. Res. 2023, 234, 116523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.