Quantification of Microplastics in Treated Drinking Water Using µ-FT-IR Spectroscopy: A Case Study from Northeast Italy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

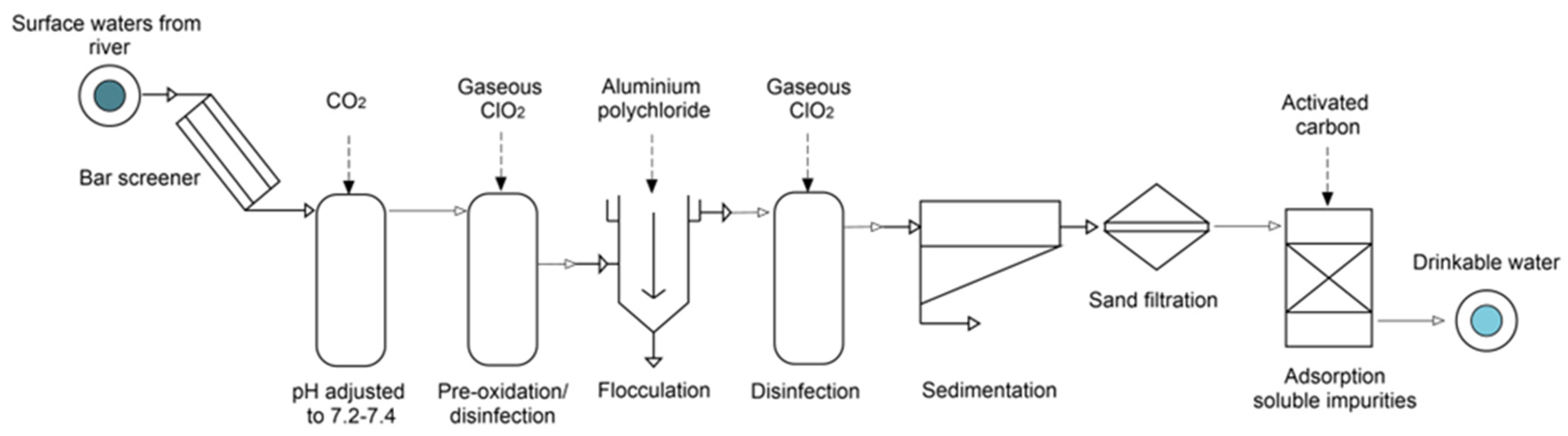

2.1. Description of the Drinking Water Treatment Plant

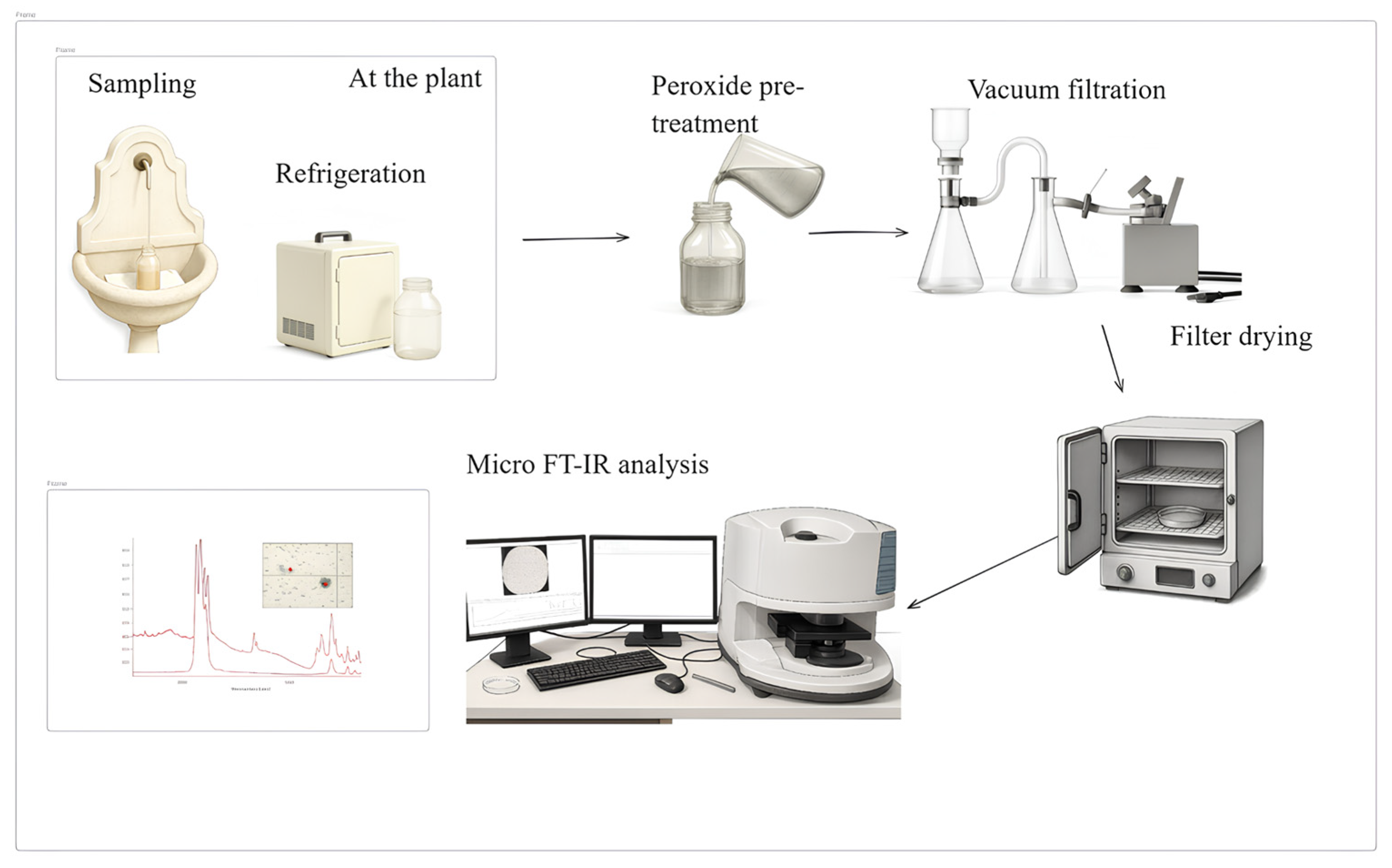

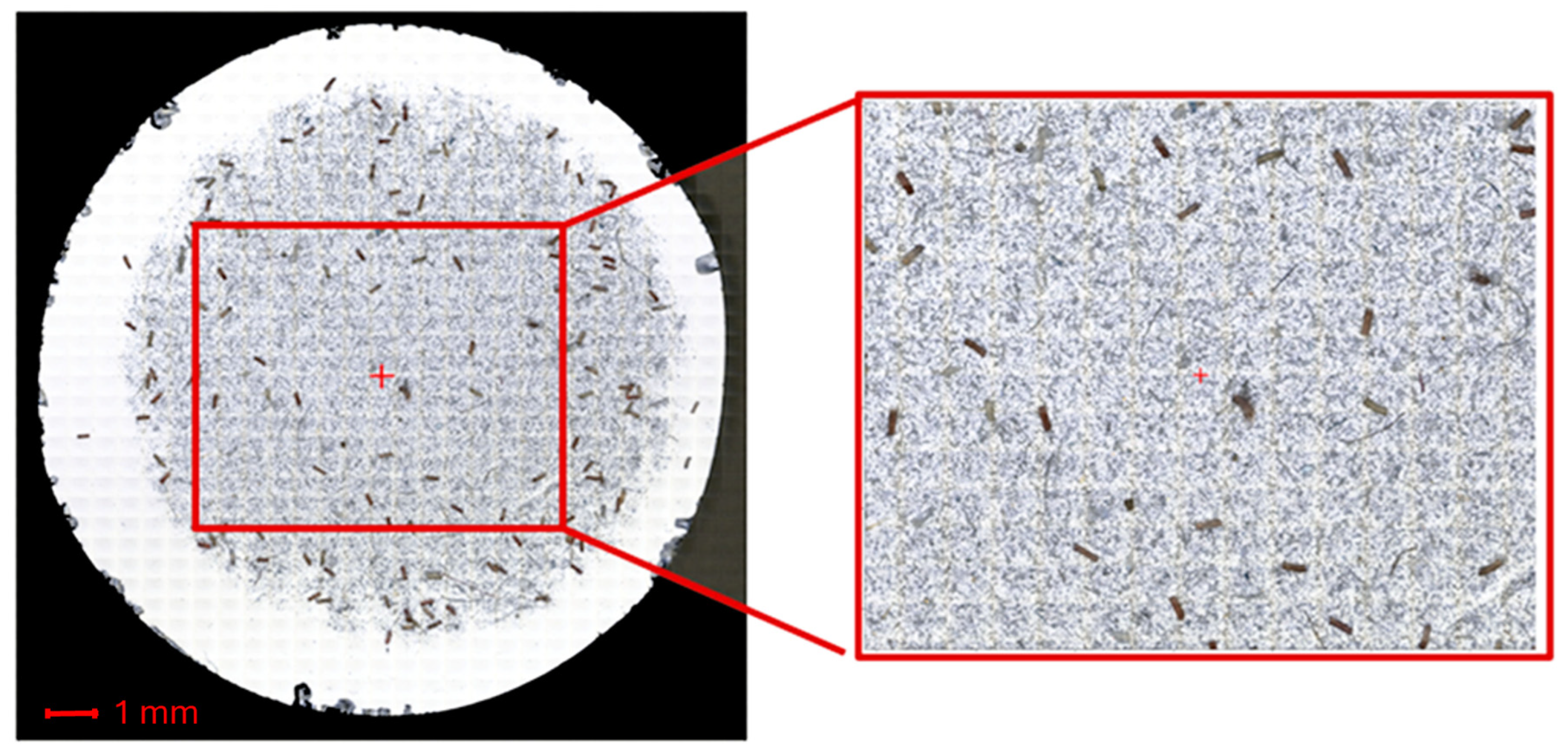

2.2. Standard Protocol for MPs Quantification

2.2.1. Water Sampling

2.2.2. Water Sample Pre-Treatment

2.2.3. Filtration

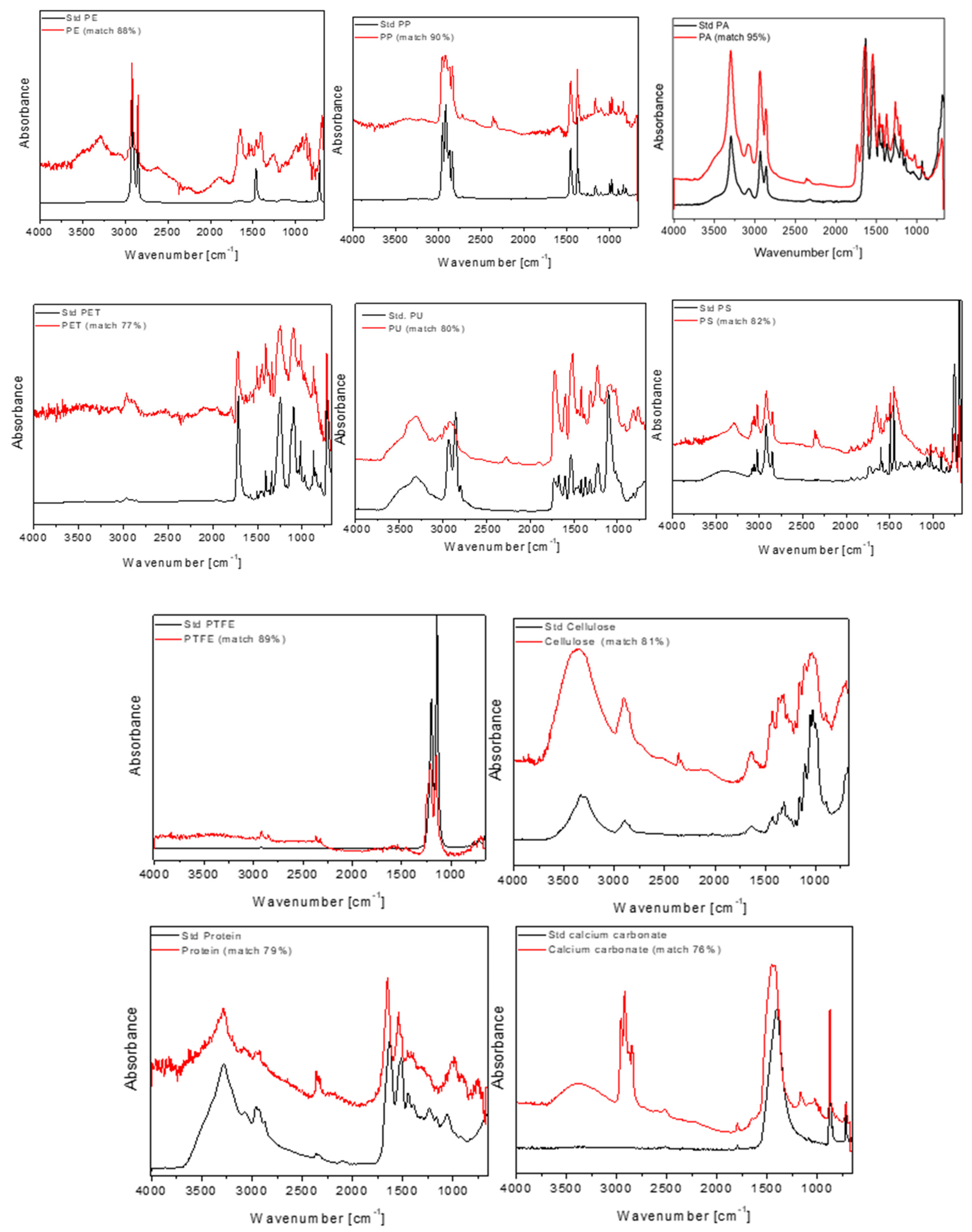

2.2.4. µ-FT-IR Analysis

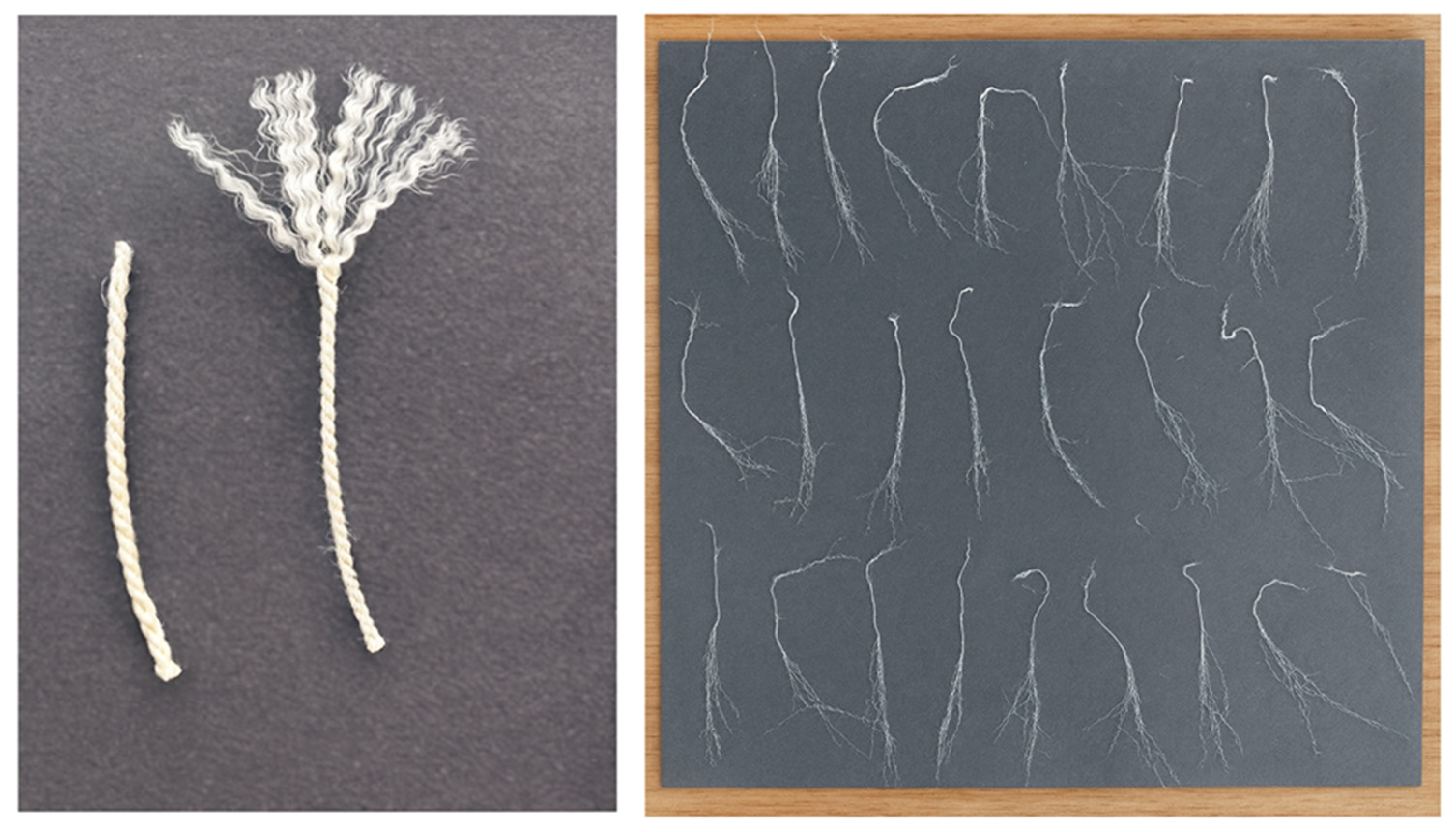

2.3. Recovery Standard

2.4. Quality Control and Analysis (QA/QC)

2.5. Graphic Analysis and Statistics

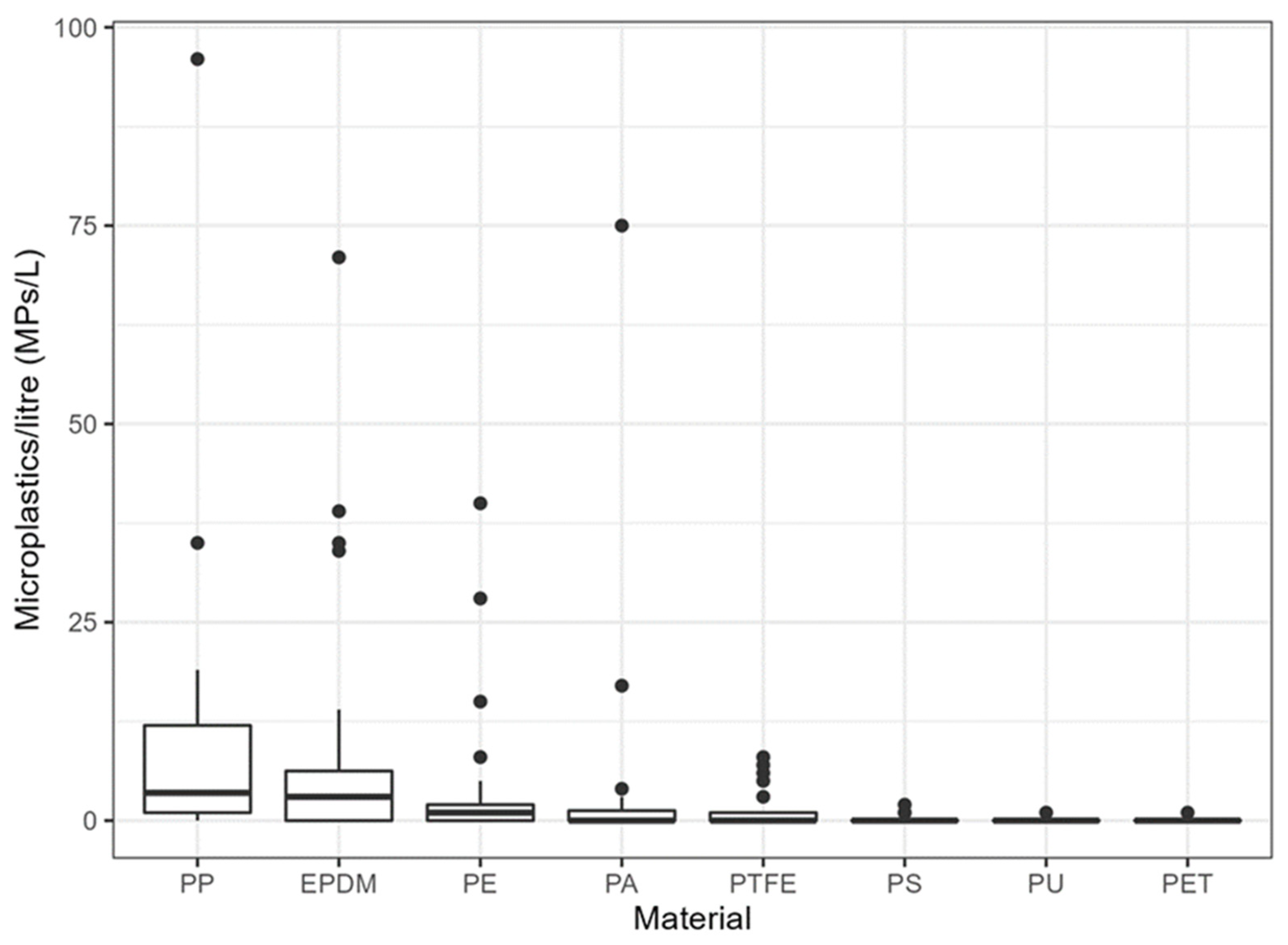

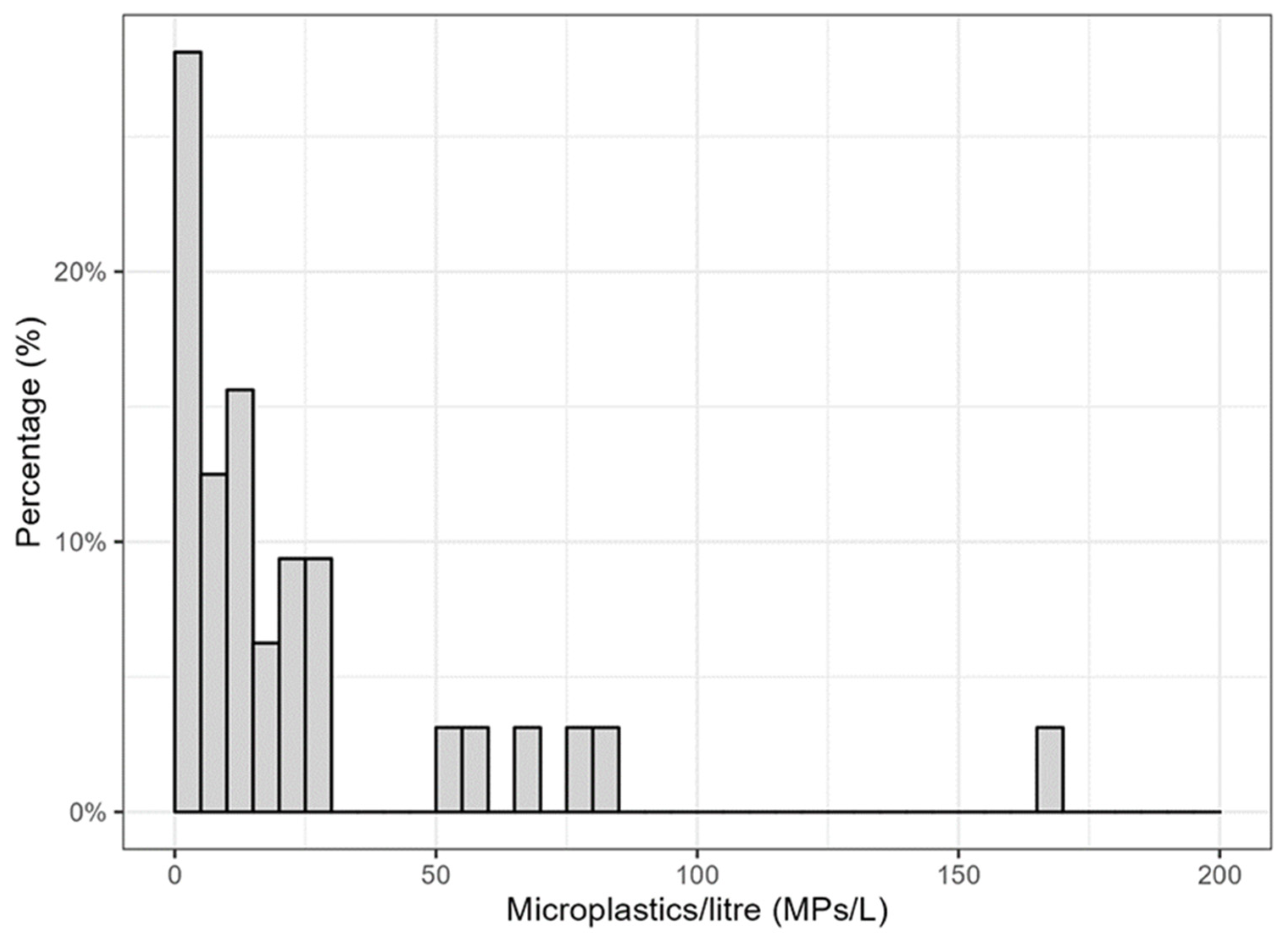

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| µ-FT-IR | Micro-Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy |

| CAGR | Compound annual growth rate |

| MPs | Microplastics |

| ECHA | European Chemicals Agency |

| PE | Polyethylene |

| PP | Polypropylene |

| PS | Polystyrene |

| PA | Polyamides |

| PET | Polyethylene terephthalate |

| PVC | Polyvinyl chloride |

| PAN | Polyacrylonitrile |

| PMA | Polymethyl acrylate |

| DWPFs | Drinking water purification facilities |

| POPs | Persistent Organic Pollutants |

| RS | Raman spectroscopy |

| Pyr-GC-MS | Pyrolysis gas chromatography/mass spectrometry |

| SEM/EDS | Scanning electron microscopy plus energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy |

| OPTIR | Optical photothermal infrared |

| QCL-IR | Quantum cascade laser infrared |

| GAC | Granular activated carbon |

| CO2 | Carbon dioxide |

| ClO2 | Chlorine dioxide |

| PAC | Aluminium polychloride |

| HDPE | High-density polyethylene |

| L | Litre |

| HQI | Hit Quality Index |

| LOD | Limit of detection |

| NaClO | Sodium hypochlorite |

| QA/QC | Quality analysis and quality control |

| EPDM | Ethylene-propylene-diene monomer |

| PTFE | Polytetrafluoroethylene |

| PU | Polyurethane |

| AT | Artificial turf |

| SBR | Styrene-butadiene rubber |

| NTU | Nephelometric Turbidity Unit |

| PUR | Polyurethane resin |

| S | Standard residual errors |

Appendix A

References

- Plastics Europe. Plastics—The Facts 2022. 2022. Available online: https://plasticseurope.org/knowledge-hub/plastics-the-facts-2022/ (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Grand View Research. Plastic Market Size, Share & Trends Analysis Report. 2024. Available online: https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/global-plastics-market (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. Global Plastics Outlook: Economic Drivers, Environmental Impacts and Policy Options; OECD Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2022; Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/environment/global-plastics-outlook_de747aef-en (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Plastics Europe. Plastics—The Facts 2019. 2019. Available online: https://plasticseurope.org/knowledge-hub/plastics-the-facts-2019/ (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Ghayebzadeh, M.; Aslani, H.; Taghipour, H.; Mousavi, S. Estimation of plastic waste inputs from land into the Caspian Sea: A significant unseen marine pollution. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 151, 110871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boucher, J.; Friot, D. Primary Microplastics in the Oceans: A Global Evaluation of Sources; IUCN International Union for Conservation of Nature: Gland, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Liu, C.; He, D.; Xu, J.; Sun, J.; Li, J.; Pan, X. Environmental behaviors of microplastics in aquatic systems: A systematic review on degradation, adsorption, toxicity and biofilm under aging conditions. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 423, 126915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novotna, K.; Cermakova, L.; Pivokonska, L.; Cajthaml, T. Pivokonsky Microplastics in drinking water treatment—Current knowledge and research needs. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 667, 730–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Chemicals Agency Annex XV Restriction Report—Microplastics. 2019. Available online: https://echa.europa.eu/documents/10162/05bd96e3-b969-0a7c-c6d0-441182893720 (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- Assis, G.; Antonelli, R.; Dantas, A.S.; Teixeira, A. Teixeira Microplastics as hazardous pollutants: Occurrence, effects, removal and mitigation by using plastic waste as adsorbents and supports for photocatalysts. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 111107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 1833-4:2023; Textiles—Quantitative Chemical Analysis—Part 4: Mixtures of Certain Protein Fibres with Certain Other Fibres (Method Using Hypochlorite). International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/86273.html (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Kosuth, M.; Mason, S.A.; Wattenberg, E.V. Anthropogenic contamination of tap water, beer, and sea salt. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0194970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Wang, X.; Niu, X.; Zeng, J.; Zhou, Y.; Suona, Z.; Yuan, Y.; Chen, X. Overview of analytical methods for the determination of microplastics: Current status and trends. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2023, 167, 117261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, L.; Zhou, N.; Chen, Y.; Ling, Z.; Xiang, P. Microplastics in the human body: A comprehensive review of exposure, distribution, migration mechanisms, and toxicity. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 946, 174215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, W.; Jarvis, P.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, J.; Chen, J.; Tan, Q.; Tian, Y. Occurrence, removal and potential threats associated with microplastics in drinking water sources. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 104527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.L.; Kim, J.G.; Kim, H.B.; Choi, J.H.; Tsang, Y.F.; Baek, K. Occurrence and removal of microplastics in wastewater treatment plants and drinking water purification facilities: A review. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 410, 128381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Microplastics in Drinking-Water. 2019. Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/326499 (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Council Directive 98/83/EC of 3 November 1998 on the Quality of Water Intended for Human Consumption. OJ L 330, 1998. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/1998/83/oj/eng (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- United Nations Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. 2015. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- European Commission. Commission Delegated Decision (EU) 2024/1441 of 11 March 2024 Supplementing Directive (EU) 2020/2184 of the European Parliament and of the Council by Laying Down a Methodology to Measure Microplastics in Water Intended for Human Consumption (Notified Under Document C(2024) 1459). Official Journal of the European Union, L 1441. 21 May 2024. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/dec_del/2024/1441/oj (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- ISO 16094-2:2025; Water Quality—Analysis of Microplastic in Water—Part 2: Vibrational Spectroscopy Methods for Waters with Low Content of Suspended Solids Including Drinking Water. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/84460.html (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- ISO 5667-27:2025; Water Quality—Sampling—Part 27: Guidance on Sampling for Microplastics in Water. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/82612.html (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Schymanski, D.; Oßmann, B.E.; Benismail, N.; Boukerma, K.; Dallmann, G.; von der Esch, E.; Fischer, D.; Fischer, F.; Gilliland, D.; Glas, K.; et al. Analysis of microplastics in drinking water and other clean water samples with micro-Raman and micro-infrared spectroscopy: Minimum requirements and best practice guidelines. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2021, 413, 5969–5994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, S.R.; Razzak, S.A.; Hassan, I.; Hossain, S.M.Z.; Hossain, M.M. Microplastics in Freshwater and Drinking Water: Sources, Impacts, Detection, and Removal Strategies. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2023, 234, 673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Guidelines for Drinking-Water Quality: Fourth Edition Incorporating the First and Second Addenda. 2022. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK579461 (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- ISO 5667-3:2024; Water Quality—Sampling—Part 3: Preservation and Handling of Water Samples. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/82273.html (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- ISO 5667-14:2014; Water Quality—Sampling—Part 14: Guidance on Quality Assurance and Quality Control of Environmental Water Sampling and Handling. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/55452.html (accessed on 11 December 2024).

- Schrank, I.; Möller, J.N.; Imhof, H.K.; Hauenstein, O.; Zielke, F.; Agarwal, S.; Löder, M.G.; Greiner, A.; Laforsch, C. Microplastic sample purification methods—Assessing detrimental effects of purification procedures on specific plastic types. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 833, 154824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Azzawi, M.S.M.; Kefer, S.; Weißer, J.; Reichel, J.; Schwaller, C.; Glas, K.; Knoop, O.; Drewes, J.E. Validation of Sample Preparation Methods for Microplastic Analysis in Wastewater Matrices—Reproducibility and Standardization. Water 2020, 12, 2445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 3696:1987; Water for Analytical Laboratory Use—Specification and Test Methods. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1987. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/9169.html (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Dris, R.; Gasperi, J.; Rocher, V.; Saad, M.; Renault, N.; Tassin, B. Microplastic contamination in an urban area: A case study in Greater Paris. Environ. Chem. 2015, 12, 592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danopoulos, E.; Twiddy, M.; Rotchell, J.M. Microplastic contamination of drinking water: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0236838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martellone, L.; Vincenzo, M.D.; Litti, L. Sampling strategies and pretreatment methods for microplastics in aquatic environments. Rapporto ISTISAN 21/2, 2021. Available online: https://www.iss.it/documents/20126/9340614/21−2+web.pdf/d1d4d928-fc56−2c27-deef-da69a905edce?t=1711721192588 (accessed on 5 December 2024).

- Zhang, X.; He, A.; Guo, R.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, L.; Morita, S.; Xu, Y.; Noda, I.; Ozaki, Y. A new approach to removing interference of moisture from FTIR spectrum. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2022, 265, 120373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mossotti, R.; Fontana, G.D.; Anceschi, A. Are we wearing pollution? 3D images and artificial intelligence to monitor microplastics. GeoTrade Geopolit. Foreign Trade Mag. 2022, 3, 84–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNI EN 1049-2:1996; Tessili. Tessuti Ortogonali—Costruzione—Metodi di Analisi. Determinazione del Numero di Fili per Unità di Lunghezza. Ente Italiano di Normazione: Rome, Italy, 1996. Available online: https://store.uni.com/uni-en-1049-2-1996 (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- UNI 5423:1964; Tessili: Prove. Determinazione del Diametro Delle Fibre di Lana con il Metodo del Microscopio a Proiezione. Ente Italiano di Normazione: Rome, Italy, 1964. Available online: https://store.uni.com/uni-5423-1964 (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- ISO 137:2015; Wool—Determination of Fibre Diameter—Projection Microscope Method. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/61688.html (accessed on 3 November 2024).

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. 2024. Available online: https://www.r-project.org/ (accessed on 22 May 2025).

- Wickham, H.; Bryan, J. R Package Readxl, Version 1.4.3. Read Excel Files. CRAN: Windhoek, Namibia, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venables, W.N.; Ripley, B.D. Modern Applied Statistics with S; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praveena, S.M.; Laohaprapanon, S. Quality assessment for methodological aspects of microplastics analysis in bottled water—A critical review. Food Control 2021, 130, 108285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koelmans, A.A.; Nor, N.H.M.; Hermsen, E.; Kooi, M.; Mintenig, S.M.; De France, J. Microplastics in freshwaters and drinking water: Critical review and assessment of data quality. Water Res. 2019, 155, 410–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Lin, T.; Chen, W. Occurrence and removal of microplastics in an advanced drinking water treatment plant (ADWTP). Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 700, 134520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, L.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Lin, L.; Chen, Y.; Shen, J. Occurrence, Degradation Pathways, and Potential Synergistic Degradation Mechanism of Microplastics in Surface Water: A Review. Curr. Pollut. Rep. 2023, 9, 312–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noordermeer, J.W.M. Ethylene–Propylene Polymers. In Kirk-Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: West Sussex, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, C.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, B.; Yao, X. Global Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET) Plastic Supply Chain Resource Metabolism Efficiency and Carbon Emissions Co-Reduction Strategies. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brancaleone, E.; Mattei, D.; Fuscoletti, V.; Lucentini, L.; Favero, G.; Cecchini, G.; Frugis, A.; Gioia, V.; Lazzazzara, M. Microplastic in Drinking Water: A Pilot Study. Microplastics 2024, 3, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, S.-H.; Kim, M.-J.; Kim, J.; Batool, R.; Cho, K.; Chung, J.; Lee, S.; Kim, E.-J. Fate and potential risks of microplastic fibers and fragments in water and wastewater treatment processes. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 463, 132938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, B.; Xue, W.; Hu, C.; Liu, H.; Qu, J.; Li, L. Characteristics of microplastic removal via coagulation and ultrafiltration during drinking water treatment. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 359, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheswaran, B.; Karmegam, N.; Al-Ansari, M.; Subbaiya, R.; Al-Humaid, L.; Raj, J.S.; Govarthanan, M. Assessment, characterization, and quantification of microplastics from river sediments. Chemosphere 2022, 298, 134268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nantege, D.; Odong, R.; Auta, H.S.; Keke, U.N.; Ndatimana, G.; Assie, A.F.; Arimoro, F.O. Microplastic pollution in riverine ecosystems: Threats posed on macroinvertebrates. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 76308–76350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Busquets, R.; Campos, L.C. Enhancing microplastic removal from natural water using coagulant aids. Chemosphere 2024, 364, 143145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Directive (EU) 2020/2184 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 December 2020 on the Quality of Water Intended for Human Consumption (Recast) (Text with EEA Relevance), OJ L 435, 23.12.2020. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32020L2184 (accessed on 16 December 2024).

- Pivokonsky, M.; Cermakova, L.; Novotna, K.; Peer, P.; Cajthaml, T.; Janda, V. Occurrence of microplastics in raw and treated drinking water. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 643, 1644–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirstein, I.V.; Gomiero, A.; Vollertsen, J. Microplastic pollution in drinking water. Curr. Opin. Toxicol. 2021, 28, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alma, O.G. Comparison of Robust Regression Methods in Linear Regression. Int. J. Contemp. Math. Sci. 2011, 6, 409–421. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, K.; Gong, W.; Lv, J.; Xiong, X.; Wu, C. Accumulation of floating microplastics behind the Three Gorges Dam. Environ. Pollut. 2015, 204, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dotti, F.; Mossotti, R.; Fontana, G.D.; Ferri, A. Drinking Water Microplastic Particles, Mendeley Data. V1. 2024. Available online: https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/88xvhcd6pz/1 (accessed on 21 September 2025).

| Volume (L) | Replicate | PET (Theoretical Value Number of Fibres: 256) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N° Fibres | % Recovered Fibres | ||

| 1 | R1 | 225 | 88 |

| 1 | R2 | 207 | 80 |

| 1 | R3 | 211 | 82 |

| 1 | R4 | 239 | 93 |

| Average | 221 | 85.8 | |

| St.dev | 13 | 5.9 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Dalla Fontana, G.; Lamprillo, D.; Dotti, F.; Ferri, A.; Foccardi, T.; Mossotti, R. Quantification of Microplastics in Treated Drinking Water Using µ-FT-IR Spectroscopy: A Case Study from Northeast Italy. Microplastics 2026, 5, 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/microplastics5010023

Dalla Fontana G, Lamprillo D, Dotti F, Ferri A, Foccardi T, Mossotti R. Quantification of Microplastics in Treated Drinking Water Using µ-FT-IR Spectroscopy: A Case Study from Northeast Italy. Microplastics. 2026; 5(1):23. https://doi.org/10.3390/microplastics5010023

Chicago/Turabian StyleDalla Fontana, Giulia, Davide Lamprillo, Francesca Dotti, Ada Ferri, Tommaso Foccardi, and Raffaella Mossotti. 2026. "Quantification of Microplastics in Treated Drinking Water Using µ-FT-IR Spectroscopy: A Case Study from Northeast Italy" Microplastics 5, no. 1: 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/microplastics5010023

APA StyleDalla Fontana, G., Lamprillo, D., Dotti, F., Ferri, A., Foccardi, T., & Mossotti, R. (2026). Quantification of Microplastics in Treated Drinking Water Using µ-FT-IR Spectroscopy: A Case Study from Northeast Italy. Microplastics, 5(1), 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/microplastics5010023