Abstract

Waste valorization is a necessary activity for the development of the circular economy. Pyrolysis as a waste valorization pathway has been extensively studied, as it allows for obtaining different fractions with diverse and valuable applications. The joint analysis of results generated by thermogravimetry (TGA) and analytical pyrolysis (Py-GC/MS) allows for the characterization of waste materials and the assessment of their potential as sources of energy, value-added chemicals and biochar, as well as providing awareness for avoiding potential harmful emissions if the process is performed without proper control or management. In the present study, these techniques were employed on three greenhouse plant residues (broccoli, tomato, and zucchini). Analytical pyrolysis was conducted at eight temperatures ranging from 100 to 800 °C, investigating the evolution of compounds grouped by their functional groups, as well as the predominant compounds of each biomass. It was concluded that the decomposition of biomass initiates between 300–400 °C, with the highest generation of volatiles occurring around 500–600 °C, where pyrolytic compounds span a wide range of molecular weights. The production of organic acids, ketones, alcohols, and furan derivatives peaks around 500 °C, whereas alkanes, alkenes, benzene derivatives, phenols, pyrroles, pyridines, and other nitrogenous compounds increase with temperature up to 700–800 °C. The broccoli biomass exhibited a higher yield of alcohols and furan derivatives, while zucchini and tomato plants, compared to broccoli, were notable for their nitrogen-containing groups (pyridines, pyrroles, and other nitrogenous compounds).

1. Introduction

Vegetal biomass residues are abundant worldwide. Each year, approximately 1000 million tons of waste are generated only from agriculture [1]. Pyrolysis as a waste valorization pathway has been extensively studied using different equipment. Recent reviews provide an updated overview of this technology [2,3,4]. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) is primarily employed to characterize samples and study their behavior with temperature, while analytical pyrolysis (Py-GC/MS) is used in laboratories to identify the volatiles that can be generated from the studied residues. The combined use of both analytical techniques enables the evaluation of the potential of waste materials as sources of energy and value-added products, as well as a deeper understanding of the kinetics and mechanisms of the thermal decomposition process.

All lignocellulosic residues contain hemicellulose, cellulose, and lignin as the major fractions; thus, the pyrolysis of these isolated components has been extensively investigated [5,6,7,8]. Most studies on the pyrolysis of lignocellulosic residues have focused on woody biomass, whereas herbaceous residues from horticulture have been much less studied. In the city of Quito (Ecuador), there are currently 2300 active urban gardens generating approximately 552 tons·year−1 of vegetable waste at various stages of production. Utilizing pyrolysis to process these residues could yield a carbonaceous residue, condensable volatiles, and gases, which could be used for various purposes.

The literature contains some references on the pyrolysis of horticultural waste with different objectives. One of the most studied residues of this type is the tomato plant, whose pyrolysis has been examined by various researchers, analyzing the kinetics of the process via thermogravimetry [9], the energy recovery of pyrolytic fractions [10], or the production of biochar for soil amendment [11]. Some references also discuss the pyrolysis of Jerusalem artichoke stems (Helianthus tuberosus), analyzing the influence of heating rate on the distribution of pyrolytic products [12], and the pyrolysis of zucchini residues for biochar production and its addition to agricultural soils [13]. Additionally, articles on the pyrolysis of various types of grasses with very little woody fraction have been identified to study their potential for bio-oil production (Imperata cylindrica) [14] or their kinetics (Cymbopogon schoenanthus) [15].

In the present study, vegetable residues (stems and leaves) from tomato (Solanum lycopersicum), broccoli (Brassica oleracea var. italica), and zucchini (Cucurbita pepo L.) plants from urban greenhouses in Quito were utilized. The objective of this research is to characterize these residues and determine the volatiles that can be obtained through flash pyrolysis, employing thermogravimetric and analytical pyrolysis techniques. This analysis could serve as a foundation for studying the implementation of small-scale biorefineries that contribute to waste valorization and the development of a circular economy.

In a previous work [16] the usefulness of these residues for obtaining biochar and its application in agricultural soil amendment was demonstrated. Therefore, knowing the volatiles released, many of them being harmful, when pyrolyzing such residues, is of great importance for designing the required facilities and, especially, the small scale in situ equipment, to minimize the environmental effect of such potential emissions.

2. Materials and Methods

Vegetable residues (stems and leaves) from tomato, broccoli, and zucchini plants were sourced from urban greenhouses in Quito, Ecuador. Prior to characterization and pyrolysis, the biomass underwent drying and milling processes.

Drying: The dehumidification of the biomass was performed in an oven at 105 °C for 14 h, reducing its moisture content from an initial value of 80–90% (wet basis) to equilibrium moisture (6–8%).

Milling: The milling of the dried biomass was done using a Retsch SM300 cutting mill (Retsch GmbH, Haan, Düsseldorf, Germany) at 700 rpm, equipped with a sieve featuring a mesh size of 1.5 mm.

Elemental Analysis: The composition of carbon (C), hydrogen (H), nitrogen (N), and sulfur (S) was determined using a CHNS FlashSmart™ Elemental Analyzer (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Considering the ash and equilibrium moisture percentages of the samples, the oxygen content was calculated by difference.

Proximate Analysis: Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was performed for each biomass sample using a Mettler-Toledo TGA-1 thermobalance to determine moisture, volatile matter, fixed carbon, and ash content. The process started at room temperature with a heating rate of 10 °C min−1 until reaching 100 °C under a nitrogen flow of 80 mL min−1, maintaining this temperature for 15 min. Following this period, the same heating rate and nitrogen flow were applied to reach 700 °C. At this point, the inert atmosphere was replaced with an air flow of 80 mL min−1, maintaining isothermal conditions for 20 min.

Heating Value: The Higher Heating Value (HHV) was calculated using the expression proposed by Huang and Lo [17]:

where C, H, O, N, and S represent the mass percentages of these elements in the biomass composition.

HHV = 0.3443C + 1.192H − 0.113O − 0.024N + 0.093S [MJ kg−1]

More details of sample characterization can be found elsewhere [16].

Thermogravimetric Analysis: TGA was performed for each biomass sample under both inert (N2) and oxidative (air) atmospheres at a heating rate of 20 °C min−1 with a flow rate of 80 mL min−1, from ambient temperature to 600 °C. Two replicates were conducted for each analysis. Approximately 6 mg of the initial sample was weighed using an analytical balance (XS205 Dual Range, Mettler Toledo, Giessen, Germany).

Analytical Pyrolysis (EGA/Py-GC/MS): A Pyroprobe model EGA/PY 3030D (Frontier Lab, Koriyama, Japan) was utilized. The gases generated during the process were directed to a gas chromatograph (GC Agilent 6890N, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) connected in series with a mass spectrometry detector (MSD Agilent 5973, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). For the pyrolysis process, samples were placed in a stainless-steel thimble with a diameter of 2 mm and a height of 8 mm, which was situated in an automatic sample holder. This holder was connected to the reactor, a quartz tube measuring 5 × 20 mm. When the furnace heating the reactor reached the preselected pyrolysis temperature, the thimble containing the sample was immediately introduced into the quartz tube, undergoing flash pyrolysis and releasing volatiles. The generated volatiles were passed through a 30 m long HP-5 capillary chromatographic column to the mass spectrometer configured as a detector.

Experiments were conducted in duplicate at eight pyrolysis temperatures: 100, 200, 300, 400, 500, 600, 700, and 800 °C. The total analysis time for the volatiles was 30 min. The amount of sample introduced in each experiment was approximately 0.25 mg, weighed on a microbalance (XS205 DualRange, Mettler Toledo) with a precision of 0.01 mg.

The interpretation of the chromatograms obtained from the equipment was performed using Agilent Technologies Mass Hunter Qualitative Analysis B.08.00 software. The spectral libraries used for compound identification were NIST 08 and WILEY 7n.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Biomass Characterization

Table 1 shows the results of each biomass characterization.

Table 1.

Characterization of each biomass.

Table 1 illustrates the similarities among the three biomass types studied; the analyzed parameters fall within a narrow range of values. As already noted in the Introduction, scientific literature related to this type of waste is limited. Font et al. [9] and Llorach-Massana et al. [11] provide data on the characterization of tomato plants that can be compared with the findings of this study. According to the information available [11], the ash content of tomato leaves ranges from 18–23%, while that of the stems lies between 8–15%. The values obtained in this study are consistent with these figures.

The elemental analysis results are similar to those presented by Font et al. [9], except for the oxygen content. Since this value is derived by difference, it depends on the values of the other components, including ash and moisture. If the percentage of ash were not included in this difference, the content of that element would be overestimated, since the metal content of the ash, as well as inorganic oxygen and other anions present in the ash, would be imputed as O. In the cited reference, the ash percentage is 56% of that reported here, which accounts for the corresponding increase in the oxygen percentage. It is important to emphasize that the ash content of a plant is strongly influenced by cultivation conditions. Tripathi et al. [18] present elemental analyses of 39 different residues, while Vassilev et al. [19] provide a review of the chemical composition of 86 distinct types of biomass. In both references, it is difficult to find lignocellulosic residues with nitrogen percentages comparable to those in the present study. Among woody biomass, the maximum value is 0.7%, whereas the highest value in herbaceous biomass is found in pepper plants at 3.2% (values expressed on an ash-free and moisture-free basis). The presence of chlorophyll in the leaves of plants may contribute to the increased nitrogen content in this type of waste.

The percentage of volatiles in these residues is also similar to that of pepper plants, although the latter exhibits a higher fixed carbon proportion (19.5%) due to possessing a lower ash content (13.5%).

As these residues are herbaceous, a low lignin percentage is expected. According to Llorach-Massana et al. [11], the lignin content in tomato stems is estimated to be 19.7%, while in the leaves it is 6.1%. In the present study, deconvolution of the thermogravimetric (TG) curves was performed using the software OriginPro 2022 to estimate this content, resulting in a value of 15.6%. Although the method employed is quite approximate, the obtained value is consistent with the data found in the literature and deviates from the percentages expected for forest biomass (20–30%).

The HHV is determined by the elemental analysis of the sample. The value for these residues is relatively low when compared to other residues with lower ash content and a higher proportion of carbon. Rojas and Flores [20] determined the heating values of over 50 fruit residues, highlighting the values for orange peels, coconut husks, and pineapple skins, which exhibit HHV ranging from 18–20 MJ kg−1.

More detailed information on the characterization of these materials can be found elsewhere [16].

3.2. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA, DTG)

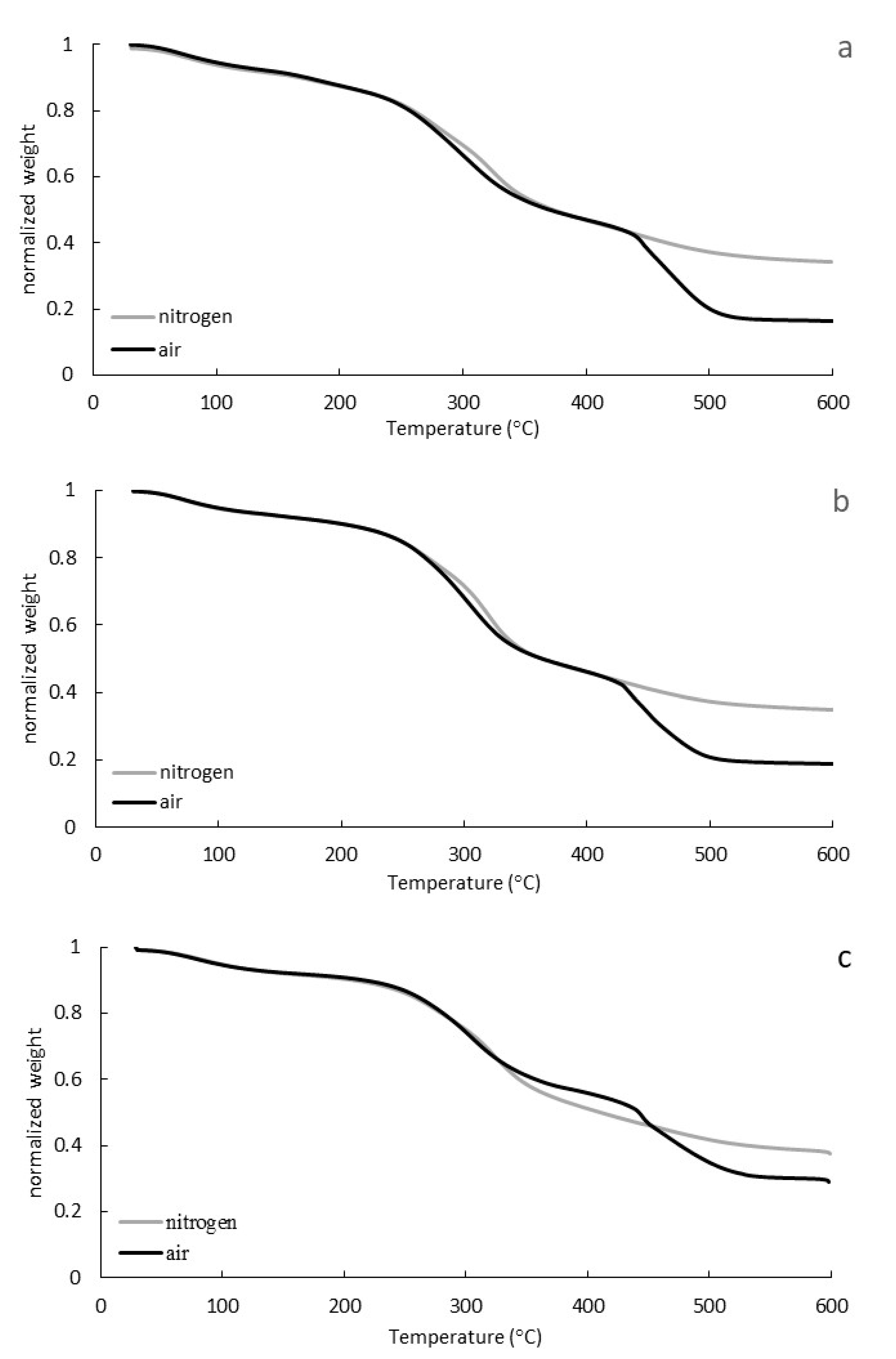

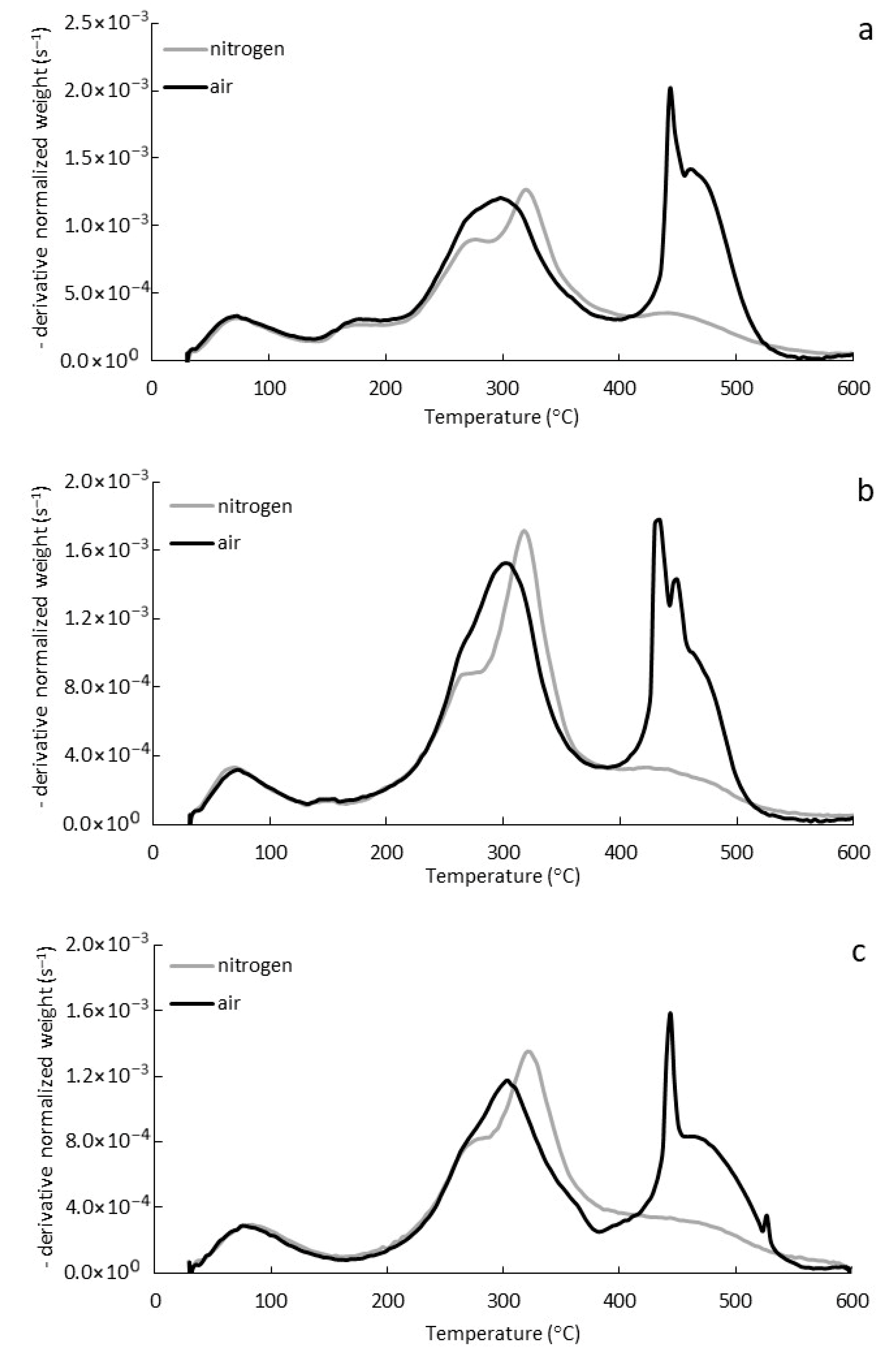

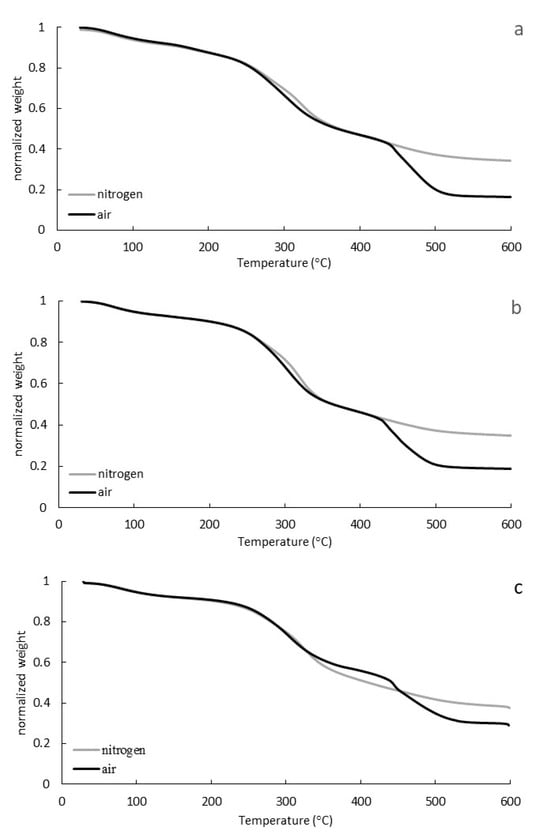

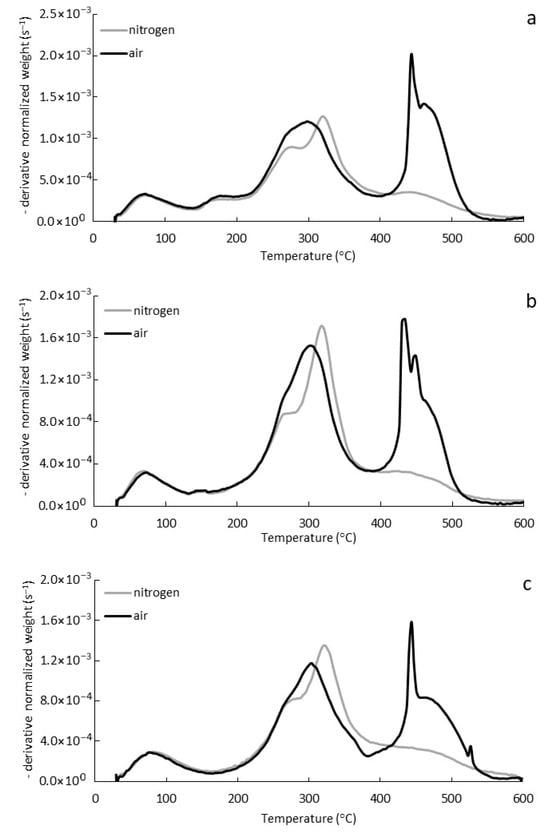

Thermogravimetric analysis was conducted on the three biomass types under both inert and oxidative atmospheres at a heating rate of 20 °C min−1. From these data, the derivative thermogravimetric (DTG) curves were obtained. Figure 1 and Figure 2 present the TG and DTG results for the three biomass types in both atmospheres, respectively. As observed, all three biomasses exhibit very similar behavior characteristic of lignocellulosic materials.

Figure 1.

Normalized TG curves of the three biomass types studied: (a) broccoli; (b) tomato; (c) zucchini (heating rate: 20 °C min−1).

Figure 2.

-DTG curves of the three biomass types studied: (a) broccoli; (b) tomato; (c) zucchini (heating rate: 20 °C min−1).

Figure 1 shows that, in general, when comparing both atmospheres, the two curves coincide up to approximately 300–400 °C. Therefore, up to this temperature, the solid decomposition process appears to be independent of the reaction atmosphere. Beyond this point, the curves diverge, as combustion of the fixed carbon occurs in the oxidative atmosphere, resulting in a more pronounced decline around 450 °C.

The DTG graph (Figure 2) clearly indicates that, although the processes in both atmospheres differ significantly after 400 °C, noticeable differences already exist below 300 °C.

The analysis of the DTG curves in a nitrogen atmosphere allows the identification of the decomposition processes of the 3 major fractions (hemicellulose, cellulose, and lignin), in addition to moisture loss at temperatures below 100 °C. The thermogravimetric analysis of these fractions has been widely studied, and the decomposition ranges for each of these fractions have been previously deduced. Some studies demonstrate that the thermal behavior of these components can vary depending on whether they are part of a biomass or have been isolated [4,21]. In the curves shown in Figure 2, the weight loss observed between 200–270 °C is primarily associated with hemicellulose decomposition, although the degradation of cellulose and lignin also begins in this range. The decomposition found between 270–380 °C is linked to the main decomposition of cellulose, with the degradation of more labile lignin and remaining hemicellulose occurring as well. The interval between 380 °C and approximately 600 °C is associated with the degradation of more resistant lignin, with a DTG peak centered around 450 °C. These temperature ranges are consistent with those found in the literature for the decomposition of hemicellulose, cellulose, and lignin [6,7,8,21,22].

Notably, the DTG curve for broccoli exhibits an additional shoulder between 130–200 °C, which may be associated, considering previous studies [23,24], with the decomposition of glucosinolates. These compounds are characteristic of the Brassica plant genus, which includes broccoli, and provide protection to the plant against diseases and infections.

Analysis of the DTG curves in an oxidative atmosphere reveals that the shoulder associated with hemicellulose decomposition becomes nearly imperceptible, overlapping with the characteristic cellulose decomposition peak. This cellulose peak appears less pronounced and occurs at lower temperatures than in the N2 atmosphere.

As previously mentioned, significant differences between the thermogravimetric curves of both atmospheres become apparent above 400 °C. While in the presence of N2, only lignin decomposition occurs above 400 °C, in an oxidative atmosphere, a series of exothermic reactions take place due to the combustion of the biochar formed during the degradation of the different biomass fractions, leading to the generation of various peaks in the DTG curves.

It is important to highlight the sharp peak that forms at approximately 450 °C in the oxidative atmosphere across all 3 biomass types, which may be associated with the combustion of the most superficial biochar fraction that reacts more violently with air. This sharp peak has been previously observed in the oxidative pyrolysis of other biomass types, increasing with the heating rate and the proportion of O2 in the atmosphere. Examples include the oxidative pyrolysis of pinewood [25], cocoa pod husks [26], and heet tobacco [27].

When comparing the 3 biomass types in both inert and oxidative atmospheres, it is evident that the DTG peaks for tomato plants are of greater intensity in both atmospheres, indicating a higher decomposition rate.

3.3. Analytical Pyrolysis (EGA/Py-GC/MS)

The objective of this technique is to analyze the volatiles generated by flash pyrolysis at different temperatures for the biomasses studied. Experiments were conducted in the temperature range of 100–800 °C for each feedstock. The results obtained from each experiment provide a list of compounds detected at each temperature, as well as the chromatographic area value for each compound, which is related to its yield.

In this study, over 200 different compounds were detected for each biomass. Only those compounds that, compared to MS library spectra, appeared at any temperature with a similarity percentage higher than 80% were selected. The chromatographic areas of each compound were normalized by the mass of the sample used in each experiment to ensure intensive comparisons (mass-independent), allowing for equivalent comparison across the 3 biomasses. This new list of compounds was then compiled into corresponding tables for each biomass (Supplementary Materials Tables S1–S3).

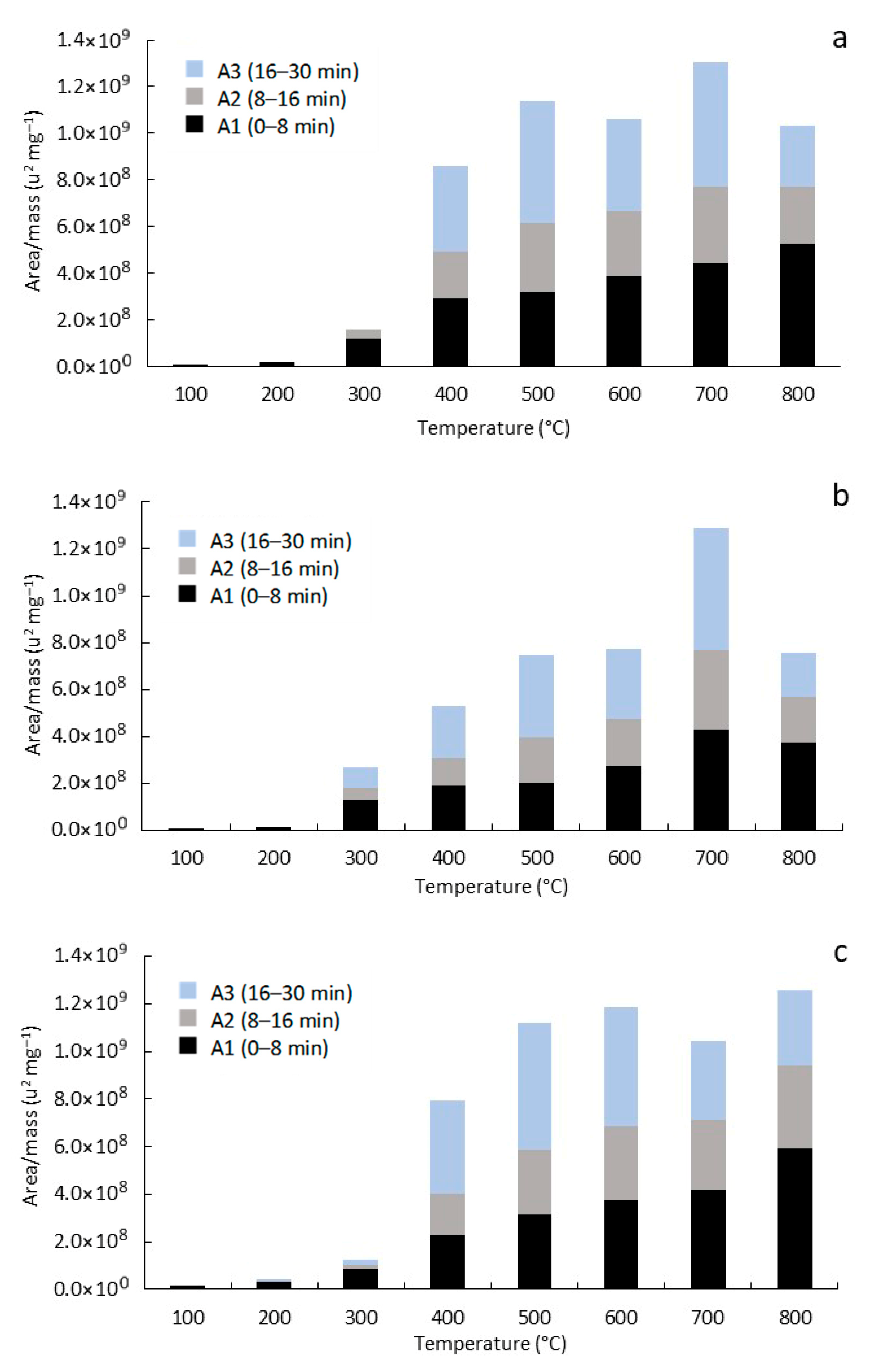

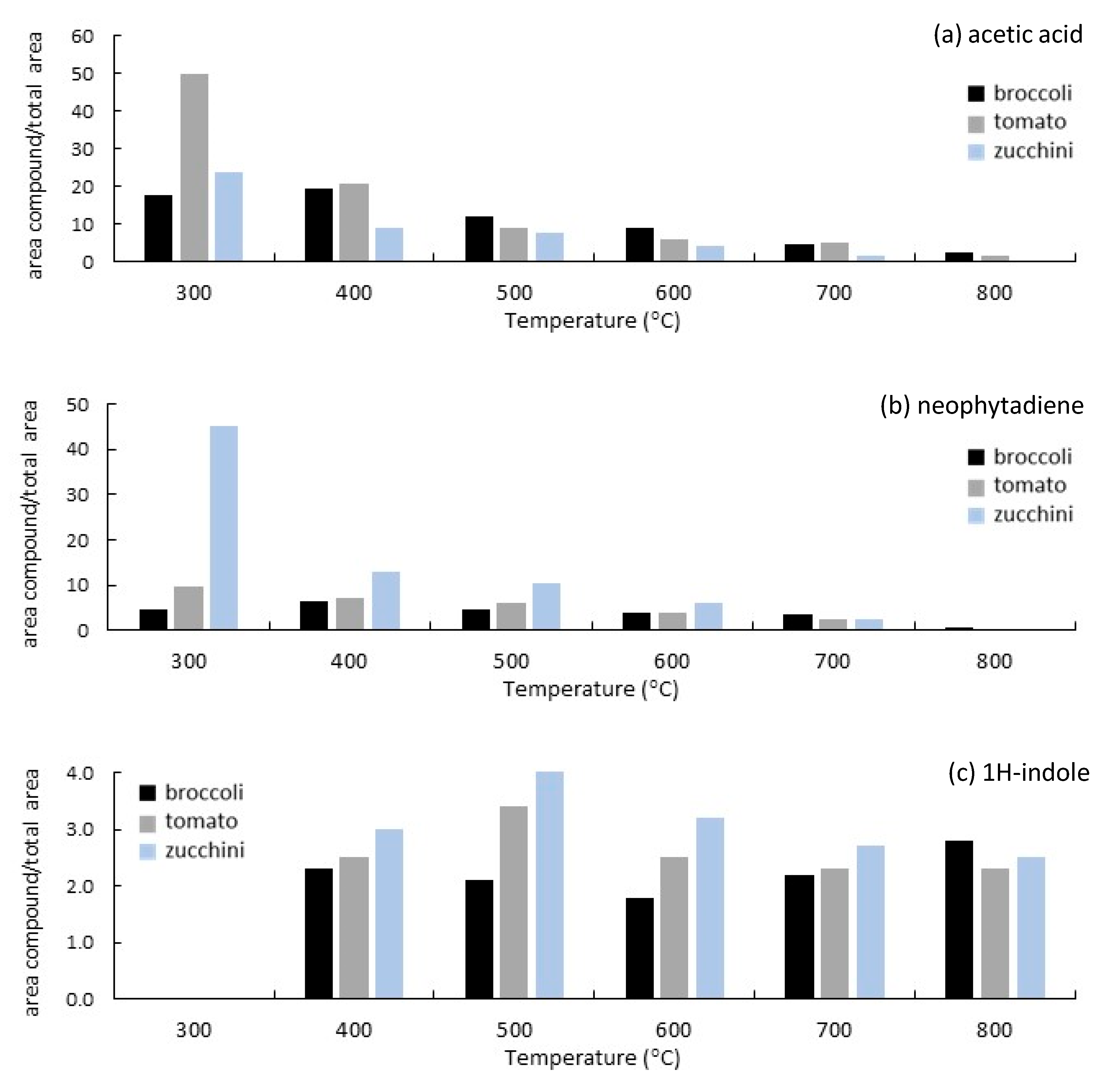

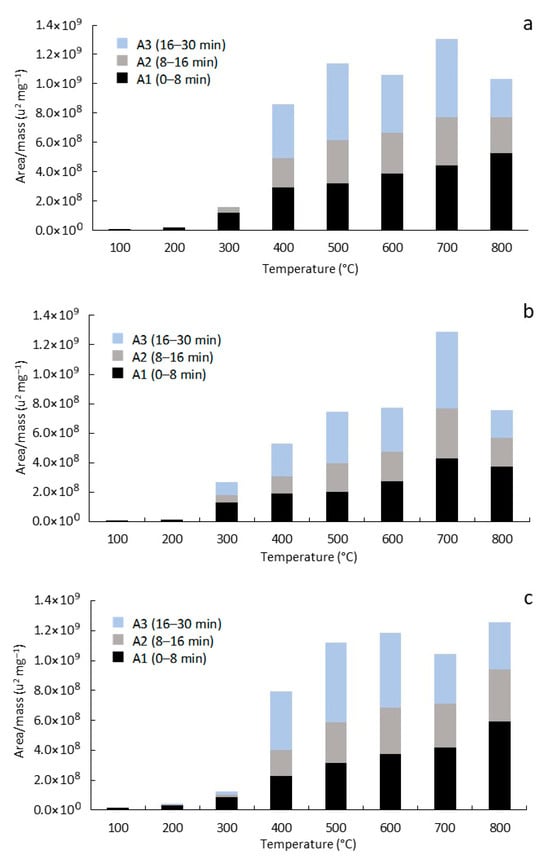

Figure 3 illustrates the evolution of total volatiles (total area/mass) for each biomass type and temperature. Additionally, the total time of each chromatogram has been divided into three sections (intervals: 0–8 min (A1), 8–16 min (A2), and 16–30 min (A3)), and the chromatographic area of the compounds present in each interval has been added.

Figure 3.

Total volatiles (total area/mass) of each biomass as a function of pyrolysis temperature: (a) broccoli; (b) tomato; (c) zucchini. Volatiles have been grouped by retention time segments.

In the first-time interval, the lighter compounds with a molecular weight of less than 100 are detected. As the retention time progresses, the compounds exhibit higher molecular weights. Figure 3 shows the evolution of the area for each section for each biomass type.

As expected, as the temperature increases, the production of total volatiles rises for all biomass types, since higher temperatures provide greater energy for bond cleavage, resulting in a higher volatilization of solid fractions. At 100 and 200 °C, no compounds are generated, with the exception of the water present in the biomasses. The maximum increase in the percentage of volatiles obtained occurs between 300 and 500 °C.

Figure 3 shows that the compounds comprising group A1 begin to appear at 300 °C for all biomass types. This group includes compounds such as water (which was already observed at 100–200 °C due to the removal of moisture present in the samples) and CO2. These are primarily products generated from the decomposition of hemicellulose and part of cellulose. Their production increases with rising pyrolysis temperature, both due to the greater decomposition of solid fractions and the formation of lighter compounds at higher temperatures (700–800 °C) as a result of the cracking of heavier molecules. The increase in these compounds with temperature is nearly linear within the studied temperature range. Compounds in group A1 are the most abundant and, in addition to water and CO2, include organic acids, alcohols, ketones, and short-chain hydrocarbons.

Regarding group A2, it is observed that the compounds begin to appear at 300 °C and experience a significant increase, with a steep slope, up to 500 °C. Beyond this temperature, the generation of compounds in this group generally stabilizes, although it may decrease slightly at higher temperatures due to possible cracking, thereby contributing to the increase in compounds in group A1. Overall, this group consists of ketones, aldehydes, and organic acids with radicals, as well as some aromatic and heterocyclic compounds such as indole.

Compounds in group A3 initiate their production intensely at 400 °C. These are heavier molecules, with maximum yields observed around 600–700 °C, clearly decreasing at higher temperatures due to cracking processes. This group includes long-chain alkanes and alkenes, as well as heavy aromatics derived from lignin, which, upon cracking, will form lighter aromatics that appear at shorter retention times.

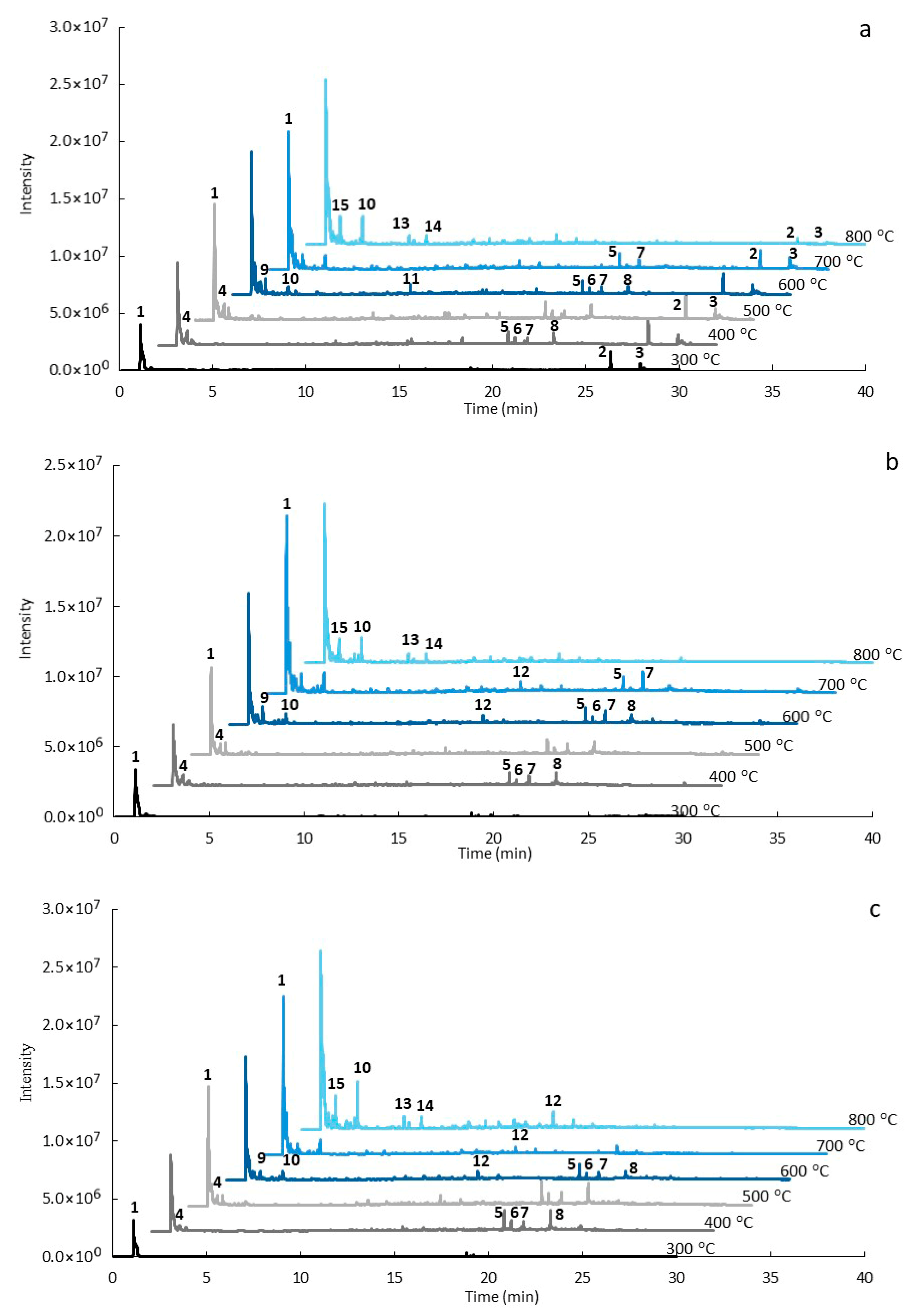

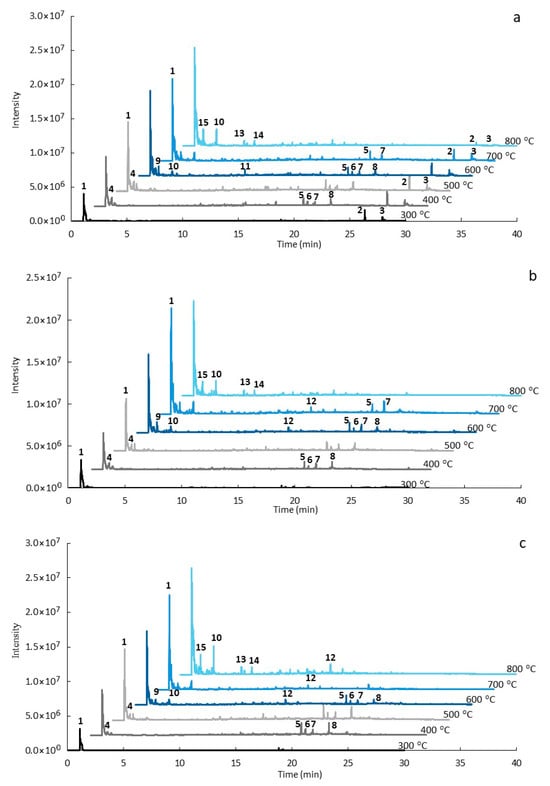

For an initial general analysis of the obtained pyrograms, these were analyzed collectively for the three biomass types at all pyrolysis temperatures, with the aim of observing the evolution of the generated volatiles and detecting similarities and differences in the decomposition of the studied biomasses. Figure 4 presents these pyrograms, with the axes shifted for better visualization. The most significant peaks detected have been numbered.

Figure 4.

Chromatograms of the volatiles obtained from each biomass at different temperatures: (a) broccoli; (b) tomato; (c) zucchini. The chromatogram for each temperature has been represented in a different color to facilitate comparison between different biomasses. The lower chromatograph in each graph (in black) corresponds to a temperature of 300 °C. The remaining chromatographs have been shifted along both axes (the x-axis by 2 min and the y-axis by 2.2 × 106 units) for better visualization. The most significant compounds are numbered according to their order of appearance in the results discussion. Numbered compounds: water (1); long-chain saturated hydrocarbon (2); m/z = 225, 241, 71, 57, 43; (3); acetic acid (4); neophytadiene (5); cyclohexane derivative (6); hexadecanoic acid (7); 9,12,15-octadecatrienoic acid (8); 2-propanone, 1-hydroxy (9); toluene (10); limonene (11); 1H-indole (12); ethylbenzene (13); styrene (14); benzene (15).

The pyrograms obtained at 100 and 200 °C are not included in the figure, as they only show the peak corresponding to water (peak #1) resulting from the dehydration of the biomasses.

At 300 °C, the decomposition of the biomasses begins, with new peaks appearing in the chromatograms, although they are still of low intensity. Notably, peaks #2 and #3 are predominantly present in broccoli at higher retention times. While their identification is complex, the mass spectrum of the first indicates that it corresponds to a long-chain saturated hydrocarbon with a molecular weight greater than 240; the second is an unidentified compound with a mass spectrum showing predominant signals at m/z = 225, 241, 71, 57, and 43. These two compounds have proven to be characteristic of broccoli decomposition, as they are barely detected in the other biomass types.

At 400 °C, the decomposition of all three biomasses becomes notable. Other peaks with high yields appear: acetic acid (#4); neophytadiene (#5); a cyclohexane derivative (#6); hexadecanoic acid (#7); and 9,12,15-octadecatrienoic acid (#8). Broccoli exhibits the highest number of detected components. At 500 °C and 600 °C, the intensities increase, particularly in the region of lighter compounds at lower retention times. Two compounds common to all three biomasses appear with greater intensity: 2-propanone, 1-hydroxy (#9) and toluene (#10). Notably, limonene (#11) is prominent in broccoli, while 1H-indole (#12) stands out in zucchini and tomato. Broccoli retains its two characteristic compounds at higher retention times. At 700 °C and 800 °C, significant cracking of heavier compounds and an increase in lighter ones are observed. Generally, the compounds group at shorter retention times, and at 800 °C, there are almost no peaks at retention times greater than 16 min in any of the three biomasses. It is noteworthy that the intensity of the two characteristic compounds of broccoli (#2 and #3), which appeared at retention times greater than 26 min, has decreased significantly. The intensities of compounds #5, 6, 7, and 8 also diminish. In contrast, ethylbenzene (#13) and styrene (#14) appear in all three biomasses, while the intensity of toluene (#10) continues to increase across all samples. The peak of 2-propanone, 1-hydroxy almost disappears while that of benzene (#15), practically imperceptible at lower temperatures and very close to 2-propanone, 1-hydroxy in the chromatogram, increases significantly.

From this initial general analysis, it can be concluded that, although CO2 and H2O are the compounds with notable intensity in all experiments, there are other compounds of greater interest generated from all biomass types that begin to appear at 300 °C and persist at higher temperatures with varying intensities: acetic acid, neophytadiene, hexadecanoic acid, limonene, 1H-indole and toluene. Overall, broccoli can be considered the biomass that generates the highest number of compounds, with higher intensity, and exhibits the most characteristic compounds in the pyrolysis process.

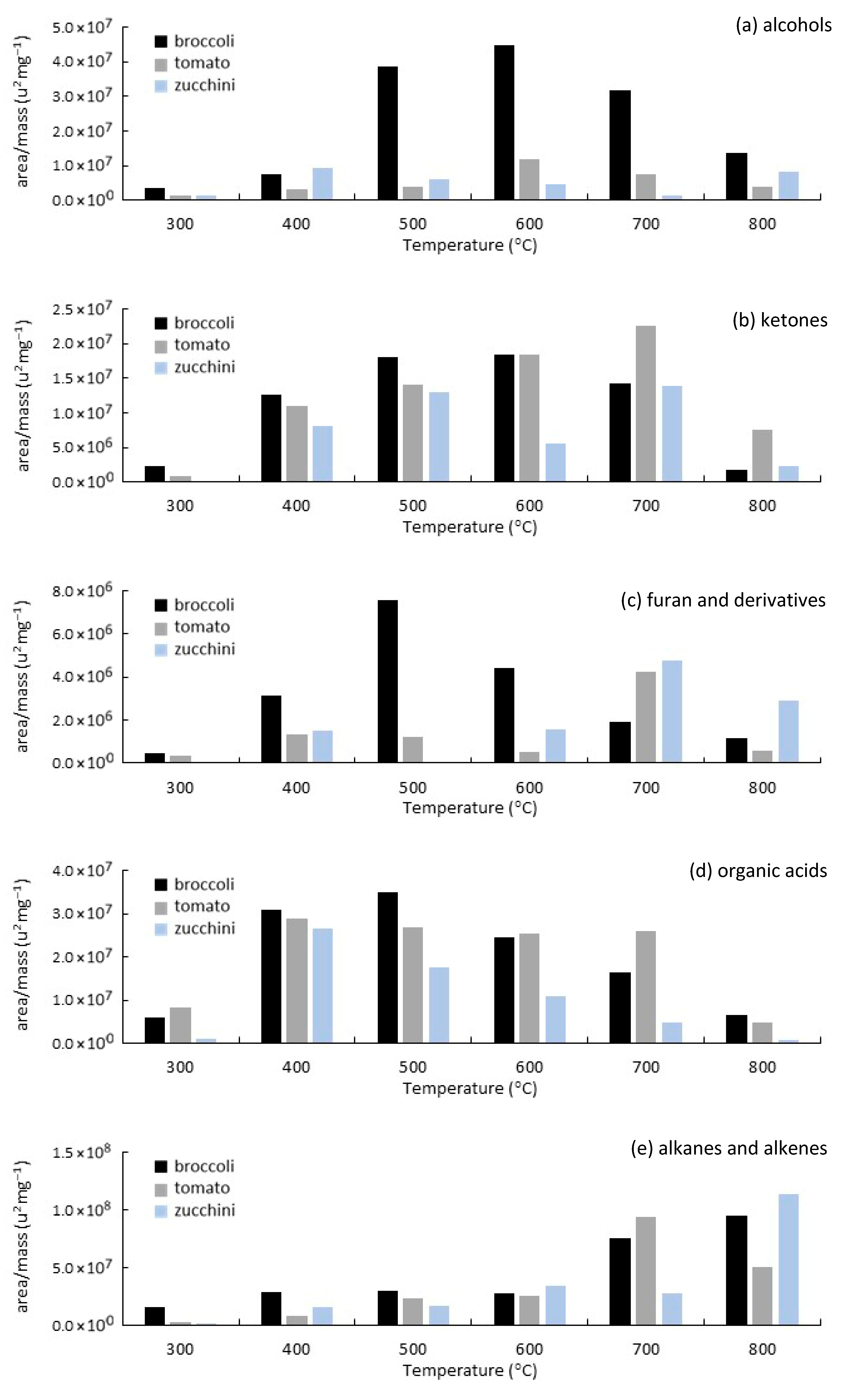

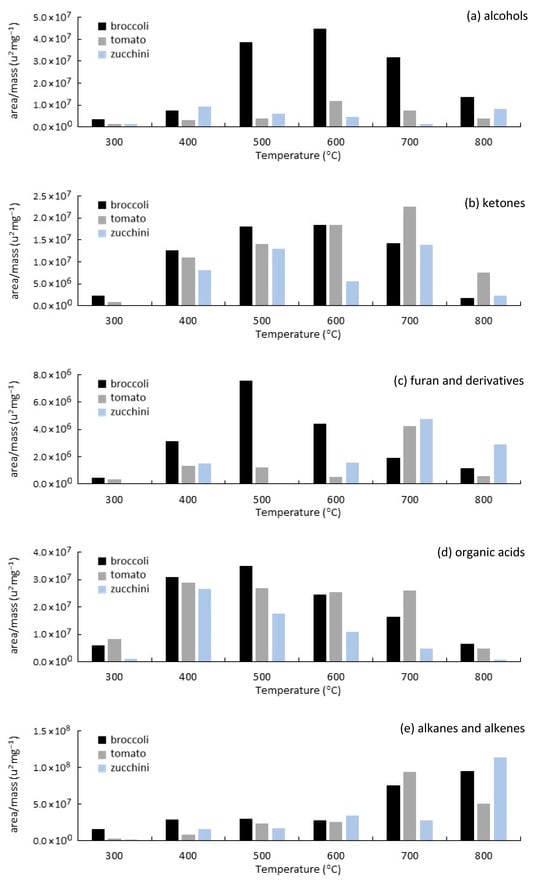

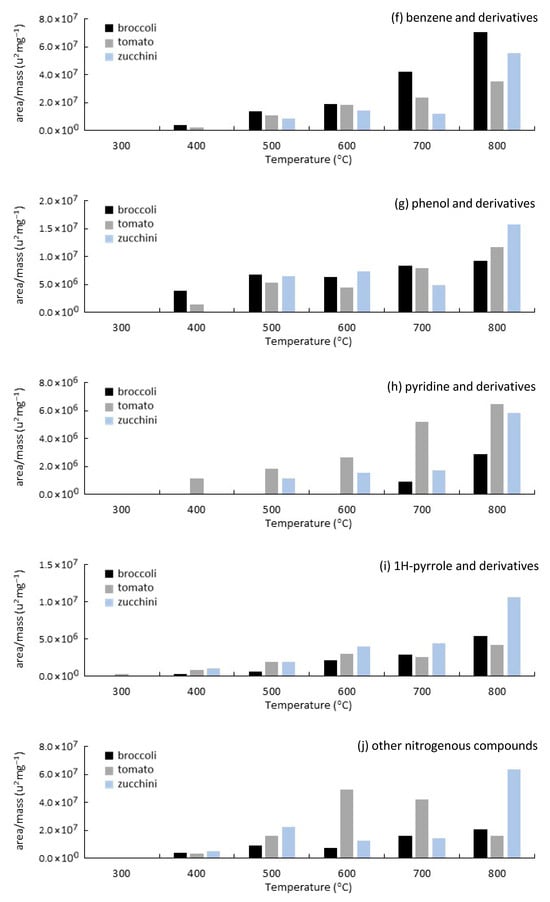

The detected volatiles (Supplementary Materials Tables S1–S3) have been grouped by families according to their main functional groups. The following groups have been selected: alcohols, ketones, furans and derivatives, alkanes and alkenes, benzene and derivatives, phenols and derivatives, organic acids, pyridine and derivatives, 1H-pyrrole and derivatives, and other nitrogenous compounds. Figure 5 displays the sum of the normalized areas (u2 mg−1) of the identified compounds belonging to each of these families for each biomass and pyrolysis temperature. None of these groups are detected at temperatures below 300 °C.

Figure 5.

Evolution of functional groups in each biomass with temperature: (a) alcohols; (b) ketones; (c) furan and derivatives; (d) organic acids; (e) alkanes and alkenes; (f) benzene and derivatives; (g) phenol and derivatives; (h) pyridine and derivatives; (i) 1H-pyrrole and derivatives; (j) other nitrogenous compounds.

As shown in Figure 5, the groups of alkanes and alkenes, along with benzene derivatives, phenols, pyridines, pyrroles, and, to a lesser extent, the group of other nitrogenous compounds, increase in intensity at higher temperatures. In contrast, the groups of alcohols, ketones, organic acids, and furan derivatives begin their production at lower temperatures, decreasing at higher temperatures either due to decomposition into lighter molecules or because other mechanisms become favored.

The evolution of these groups is determined by the thermal stability of the fractions from which they originate. For example, the depolymerization of hemicellulose at lower temperatures primarily produces acetic acid and furan derivatives, making it logical to expect the formation of these compounds in significant quantities at lower temperatures. However, aromatic compounds and phenolic derivatives mainly arise from the decomposition of lignin, a polymer that is much more stable than hemicellulose, thus suggesting an increase in the yield of such compounds with rising pyrolysis temperatures. The study of the pyrolysis of the macromolecules hemicellulose, cellulose, and lignin, conducted individually, has been carried out by numerous authors [6,28,29] to analyze the stability of each fraction and identify the predominant products obtained in each case.

Regarding the relationship between the biomass studied and the yields of the functional groups obtained, it is observed that broccoli exhibits the highest and most significant yield in alcohols and furans (furfural being especially significant in this second group), which aligns with its higher percentage of oxygen. The zucchini and tomato plants stand out, in contrast to broccoli, in the groups containing N (pyridines, pyrroles, and other nitrogenous compounds), corroborating their higher N content compared to broccoli. The tomato plant is particularly notable for its yield in the ketone group and, along with broccoli, in organic acids, with yields significantly higher than those produced by zucchini.

These results are comparable to those obtained by Wang et al. [12] in their study on the decomposition of Jerusalem artichoke stems, where the predominant functional groups were carbonyl compounds and organic acids, also yielding significant values for phenolic derivatives.

Overall, the compounds belonging to these functional groups have applications in various industrial sectors (food industry, fuels, textiles, pharmaceuticals, etc.).

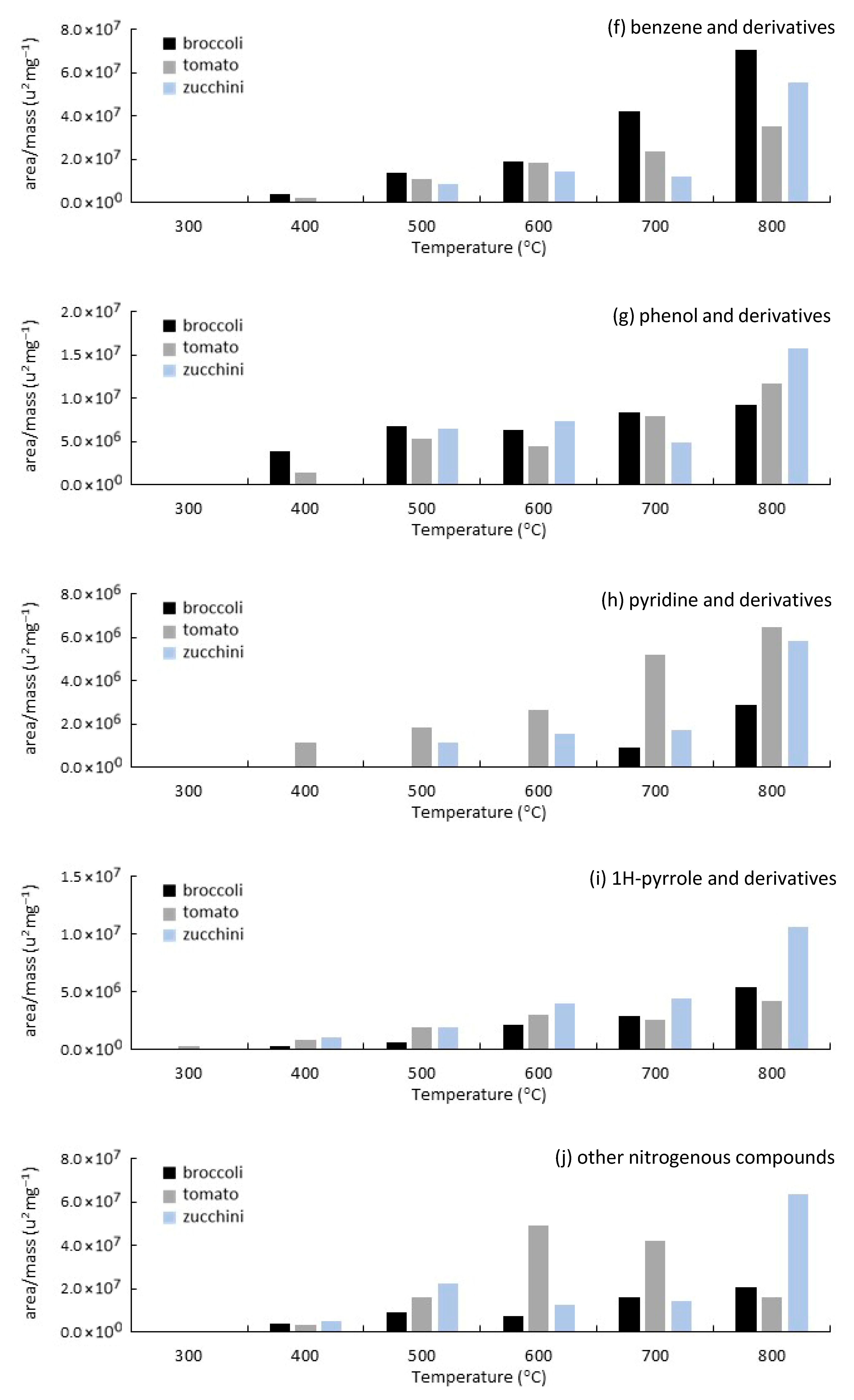

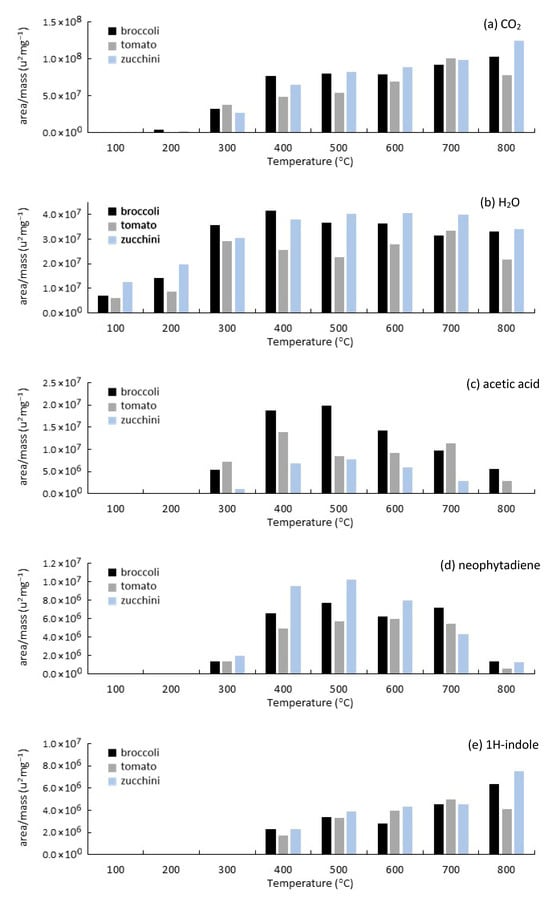

Figure 6 presents the evolution of some specific compounds with temperature. CO2 and H2O (Figure 6a,b) are the most abundant compounds at any temperature across all three biomasses. The area/mass value for CO2 sometimes exceeds that of the other major compounds by a factor of 10. CO2 is produced starting at 300 °C and increases almost linearly up to 800 °C, with zucchini exhibiting the highest production. H2O is initially present in the biomasses as bound water and is released as vapor through heating from the initial temperatures of the process. However, its yield increases up to 400 °C due to the pyrolysis process and remains constant up to 800 °C. Zucchini, along with broccoli, generates the largest amount of water. These compounds are formed through decarboxylation and dehydration reactions that occur during the biomass decomposition, either directly from the solid or from intermediates generated during the process [7,30,31].

Figure 6.

Evolution of some specific compounds with temperature: (a) carbon dioxide; (b) water; (c) acetic acid; (d) neophytadiene; (e) 1H-indole.

Acetic acid and neophytadiene are compounds with high yields (expressed as area/mass of sample) (Figure 6c,d). Acetic acid is observed starting from 300 °C, reaching a maximum between 400–500 °C. It is primarily formed from the decomposition of hemicellulose through the cleavage of O-acetyl groups [6]. At higher temperatures, its production decreases because the reactions that form acids become less competitive at elevated temperatures, and the acids that are already formed undergo cracking into lighter molecules [7]. The biomass that produces the most acetic acid is broccoli, while zucchini produces it to a lesser extent.

Neophytadiene, a long-chain branched alkene (C20H38), also exhibits a maximum yield between 400–600 °C, nearly disappearing at 800 °C. It is a natural pigment found in a wide variety of fruits and vegetables, particularly in leafy greens and tomatoes. Among the biomasses studied in this work, zucchini produces the highest amount of this compound, followed by broccoli and then tomato. Notably, research by Shi et al. [32] on vegetables affected by whiteflies concluded that there is a correlation between the level of neophytadiene in the vegetables and the apparent attraction to this insect, which may aid in controlling these pests.

The behavior of indole (C8H7N) (Figure 6e), a heterocyclic organic compound, is different, as its yield increases with temperature in all three biomasses, with zucchini standing out at 800 °C.

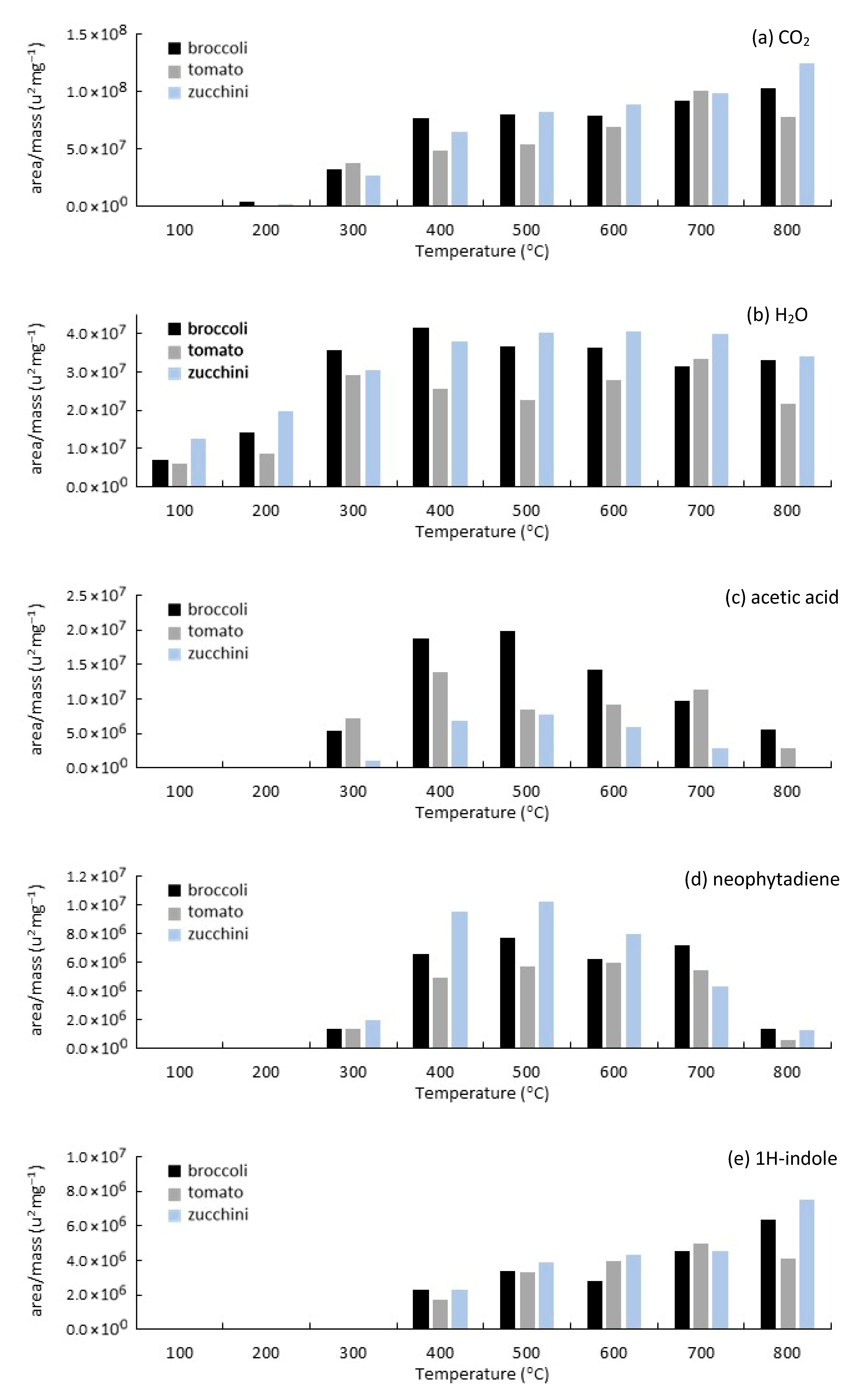

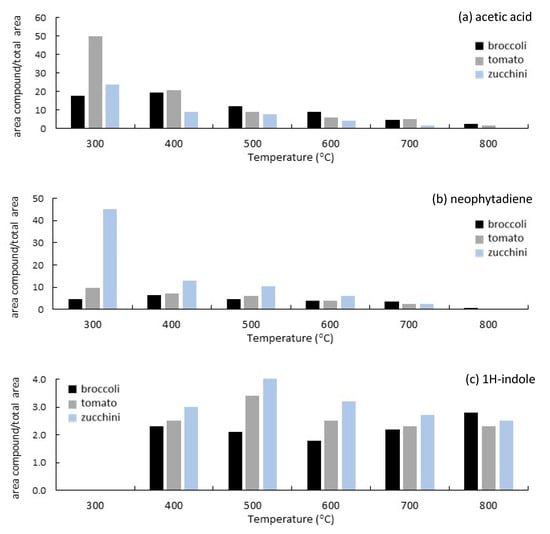

Figure 7 compares the evolution of the relative area values (compound area/total area) for acetic acid, neophytadiene, and indole (with the area values of CO2 and H2O subtracted from the total area calculation). While Figure 6 is associated with the yield of the compounds, Figure 7 can be related to the mass fraction of the compound in the total mixture. As can be observed, the evolution of the compound area/mass ratios and compound area/total area ratios are quite different. Both acetic acid and neophytadiene are compounds that begin to form at very low temperatures, when only a few other volatiles have been generated. This results in high concentrations, even at 300 °C, despite their low yields. As the process temperature increases and other volatiles are produced, the relative area values for both compounds decrease. In the case of indole, the fact that its yield increases with temperature allows its proportion within the total mixture to remain approximately constant.

Figure 7.

Comparison of area percentages for some generated compounds: (a) acetic acid; (b) neophytadiene; (c) 1H-indole. In this figure, total area does not include the area values of CO2 and H2O.

4. Conclusions

In this study, a thermogravimetric analysis of waste biomass from broccoli, tomato, and zucchini plants sourced from urban greenhouses was conducted, both in inert and oxidative atmospheres. Additionally, the analytical pyrolysis of each of these residues was performed within the temperature range of 100–800 °C, analyzing the evolution of the generated volatiles.

After a preliminary drying treatment, the residues reached an average equilibrium moisture content of 7%. Under these conditions, their ash content ranged from 17% to 22%, while the volatile content was approximately 58%.

The thermogravimetric analysis reveals the decomposition pattern characteristic of lignocellulosic residues, where, in an inert atmosphere, processes associated mainly with the decomposition of hemicellulose (peaking around 280 °C), cellulose (peaking around 320 °C), and lignin (peaking around 450 °C) can be distinguished. In the case of broccoli, an additional decomposition process is observed around 180 °C, which is associated with the glucosinolate content of this residue. In an oxidative atmosphere, the decomposition processes of hemicellulose and cellulose overlap. Around 450 °C, a very sharp DTG peak is noted, which is associated with the violent combustion of the more superficial biomass, which is more reactive with air, as well as the biochar formed at lower temperatures. The decomposition of lignin continues to occur over a broad temperature range.

From the pyrograms obtained during the analytical pyrolysis of these residues, it can be concluded that the decomposition of the biomasses begins between 300–400 °C. The maximum number of different volatiles was observed at around 500–600 °C, where the compounds encompass a wide range of molecular weights. At higher temperatures (700–800 °C), the formation of lighter molecules is favored (thermal cracking), and all compounds are concentrated at shorter retention times.

Although CO2 and H2O are the compounds with notable intensity in all experiments, there are other compounds of greater interest generated, such as acetic acid, neophytadiene, hexadecanoic acid, 2-propanone,1-hydroxy, toluene, limonene, 1H-indole, ethylbenzene, styrene and benzene.

The generation of organic acids, ketones, alcohols, and furan derivatives reaches a maximum around 500 °C, while alkanes, alkenes, benzene derivatives, phenols, pyrroles, pyridines, and other nitrogenous compounds increase with temperature up to 700–800 °C. The evolution of these functional groups is determined by the thermal stability of the fractions from which they originate. Thus, for example, acetic acid and furan derivatives are generated at low temperatures since they come mainly from the depolymerization of hemicellulose, while aromatics and phenolic derivatives that come mainly from the decomposition of lignin increase their yield at high temperatures.

Although the decomposition of the three biomasses is similar, broccoli stands out by initiating its decomposition earlier, with the generation of two compounds with molecular weights greater than 240, which are characteristic of the pyrolysis of this biomass across all temperatures. Broccoli exhibits a higher yield of alcohols and furan derivatives, which corresponds to its greater oxygen content. In contrast, zucchini and tomato plants generate much more nitrogen-containing compounds than broccoli (pyridines, pyrroles, and other nitrogenous compounds), corroborating their higher percentage of this element.

The evolution of the compound area/mass ratios (associated with the compound yield) and compound area/total area ratios (related to the compound mass fraction) are quite different. For example, both acetic acid and neophytadiene begin to form at 300 °C, reaching a maximum at intermediate temperatures. However, the fact that only a few other volatiles are generated at low temperatures results in the compound area/total area ratio reaching its maximum value at 300 °C, decreasing significantly by increasing temperature. In the case of 1H-indole, the fact that its yield increases with temperature allows its proportion within the total mixture to remain approximately constant.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/biomass6010002/s1, Table S1: EGA/Py-GC/MS analysis results of broccoli residues. Values (area/pyrolyzed mass) of the compounds identified with a similarity percentage (score) with the libraries higher than 80%, in any of the experiments; Table S2: EGA/Py-GC/MS analysis results of tomato residues. Values (area/pyrolyzed mass) of the compounds identified with a similarity percentage (score) with the libraries higher than 80%, in any of the experiments; Table S3: EGA/Py-GC/MS analysis results of zucchini residues. Values (area/pyrolyzed mass) of the compounds identified with a similarity percentage (score) with the libraries higher than 80%, in any of the experiments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M. and A.N.G.; methodology, S.M. and F.G.; software, S.M. and F.G.; validation, A.N.G., A.M. and U.S.; formal analysis, U.S., A.M. and A.N.G.; investigation, S.M., U.S. and F.G.; resources, S.M. and F.G.; data curation, S.M., F.G. and A.N.G.; writing—original draft preparation, S.M. and F.G.; writing—review and editing, S.M., U.S., F.G., A.N.G. and A.M.; visualization, S.M. and F.G.; supervision, U.S., A.N.G. and A.M.; project administration, U.S. and A.M.; funding acquisition, S.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Universidad Central del Ecuador (International Collaboration Agreement No. 061-P-05).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article and Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DTG | Derivative thermogravimetric |

| EGA/Py-GC/MS | Evolved gas analysis/Pyrolyzer—Gas chromatography/Mass spectrometry |

| HHV | Higher heating value |

| Py-GC/MS | Pyrolyzer—Gas chromatography/Mass spectrometry |

| TGA | Thermogravimetric analysis |

References

- Sathish Kumar, R.K.; Sasikumar, R.; Dhilipkumar, T. Exploiting agro-waste for cleaner production: A review focusing on biofuel generation, bio-composite production, and environmental considerations. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 435, 140536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerzak, W.; Acha, E.; Li, B. Comprehensive review of biomass pyrolysis: Conventional and advanced technologies, reactor designs, product compositions and yields, and techno-economic analysis. Energies 2024, 17, 5082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuppaladadiyam, A.K.; Vuppaladadiyam, S.S.V.; Sikarwar, V.S.; Ahma, E.; Pant, K.K.; Murugavelh, S.; Pandey, A.; Bhattacharya, S.; Sarmah, A.; Leu, S.-Y. A critical review on biomass pyrolysis: Reaction mechanisms, process modeling and potential challenges. J. Energy Inst. 2023, 108, 101236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Dai, Y.; Yang, H.; Xiong, Q.; Wang, K.; Zhou, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, S. A review of recent advances in biomass pyrolysis. Energy Fuels 2020, 34, 15557–15578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.-X.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, F.; Jiang, L.-Q.; Zhao, Z.-L.; Li, H.-B. TG-FTIR for kinetic evaluation and evolved gas analysis of cellulose with different structures. Fuel 2020, 268, 117365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.H.; Wang, C.W.; Ong, H.C.; Show, P.L.; Hsieh, T.H. Torrefaction, pyrolysis and two-stage thermodegradation of hemicellulose, cellulose and lignin. Fuel 2019, 258, 116168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, D.K.; Gu, S.; Bridgwater, A.V. Study on the pyrolytic behaviour of xylan-based hemicellulose using TG-FTIR and Py-GC-FTIR. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2010, 87, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, D.; Xiao, R.; Gu, S.; Zhang, H. The Overview of Thermal Decomposition of Cellulose in Lignocellulosic Biomass. In Cellulose—Biomass Conversion; van der Ven, T., Kadla, J., Eds.; InTechOpen: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Font, R.; Moltó, J.; Gálvez, A.; Rey, M.D. Kinetic study of the pyrolysis and combustion of tomato plant. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2009, 85, 268–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Encinar, J.M.; González, J.F.; Martínez, G. Energetic use of the tomato plant waste. Fuel Process. Technol. 2008, 89, 1193–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llorach-Massana, P.; Lopez-Capel, E.; Peña, J.; Rieradevall, J.; Montero, J.I.; Puy, N. Technical feasibility and carbon footprint of biochar co-production with tomato plant residue. Waste Manag. 2017, 67, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Xu, F.; Zong, P.; Zhang, J.; Tian, Y.; Qiao, Y. Effects of heating rate on fast pyrolysis behavior and product distribution of Jerusalem artichoke stalk by using TG-FTIR and Py-GC/MS. Renew. Energy 2019, 132, 486–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohawesh, O.; Coolong, T.; Aliedeh, M.; Qaraleh, S. Greenhouse evaluation of biochar to enhance soil properties and plant growth performance under arid environment. Bulg. J. Agric. Sci. 2018, 24, 1012–1019. [Google Scholar]

- Hidayat, S.; Abu Bakar, M.S.; Yang, Y.; Phusunti, N.; Bridgwater, A.V. Characterisation and Py-GC/MS analysis of Imperata Cylindrica as potential biomass for bio-oil production in Brunei Darussalam. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2018, 134, 510–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, M.A.; Ye, G.; Luo, H.; Liu, C.; Malik, S.; Afzal, I.; Xu, J.; Ahmad, M.S. Pyrolysis and kinetic analyses of Camel grass (Cymbopogon schoenanthus) for bioenergy. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 228, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, S.; Stahl, U.; Ruiz, W.; García, A.N.; Marcilla, A. Characterization of Biochar Produced from Greenhouse Vegetable Waste and Its Application in Agricultural Soil Amendment. AgriEngineering 2025, 7, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.-F.; Lo, S.-L. Predicting heating value of lignocellulosic biomass based on elemental analysis. Energy 2020, 191, 116501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, M.; Sahu, J.N.; Ganesan, P. Effect of process parameters on production of biochar from biomass waste through pyrolysis: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 55, 467–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassilev, S.V.; Baxter, D.; Andersen, L.K.; Vassileva, C.G. An overview of the chemical composition of biomass. Fuel 2010, 89, 913–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, A.; Flores, C. Valorización de residuos de frutas para combustión y pirólisis. Rev. Politec. 2019, 15, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanidis, S.D.; Kalogiannis, K.G.; Iliopoulou, E.F.; Michailof, C.M.; Pilavachi, P.A.; Lappas, A.A. A study of lignocellulosic biomass pyrolysis via the pyrolysis of cellulose, hemicellulose and lignin. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2014, 105, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Resende, F.L.P.; Moutsoglou, A.; Raynie, D.E. Pyrolysis of lignin extracted from prairie cordgrass, aspen, and Kraft lignin by Py-GC/MS and TGA/FTIR. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2012, 98, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Mourant, D.; Gunawan, R.; Lievens, C.; Wang, X.S.; Ling, K.; Bartle, J.; Li, C.Z. Yield and properties of bio-oil from the pyrolysis of mallee leaves in a fluidised-bed reactor. Fuel 2012, 102, 506–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLeod, A.J.; Panesar, S.S.; Gil, V. Thermal degradation of glucosinolates. Phytochemistry 1981, 20, 977–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amutio, M.; Lopez, G.; Aguado, R.; Artetxe, M.; Bilbao, J.; Olazar, M. Kinetic study of lignocellulosic biomass oxidative pyrolysis. Fuel 2012, 95, 305–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Londoño-Larrea, P.; Villamarín-Barriga, E.; García, A.N.; Marcilla, A. Study of cocoa pod husks thermal decomposition. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 9318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcilla, A.; Berenguer, D.; Martínez, I. Effect of the addition of zeolites and silicate compounds on the composition of the smoke generated in the decomposition of Heet tobacco under inert and oxidative atmospheres. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2022, 164, 105532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Gao, A.; Cen, K.; Zhang, J.; Cao, X.; Ma, Z. Investigation of biomass torrefaction based on three major components: Hemicellulose, cellulose, and lignin. Energy Convers. Manag. 2018, 169, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Xiuwen, W.; Hu, J.; Liu, Q.; Shen, D.; Xiao, R. Thermal degradation of softwood lignin and hardwood lignin by TG-FTIR and Py-GC/MS. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2014, 108, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, K.B.; Arora, J.S.; Chew, J.W.; Dauenhauer, P.J.; Mushrif, S.H. Fast Pyrolysis of Cellulose, Hemicellulose, and Lignin: Effect of Operating Temperature on Bio-oil Yield and Composition and Insights into the Intrinsic Pyrolysis Chemistry. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2019, 58, 15838–15852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vikram, S.; Rosha, P.; Kumar, S. Recent modeling approaches to biomass pyrolysis: A review. Energy Fuels 2021, 35, 7406–7433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Preisser, E.L.; Liu, B.; Pan, H.; Xiang, M.; Xie, W.; Wang, S.; Wu, Q.; Li, C.; Liu, Y.; et al. Variation in both host defense and prior herbivory can alter plant-vector-virus interactions. BMC Plant Biol. 2019, 19, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.