Green Synthesis of Activated Carbon from Waste Biomass for Biodiesel Dry Wash

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Activated Carbon Synthesis

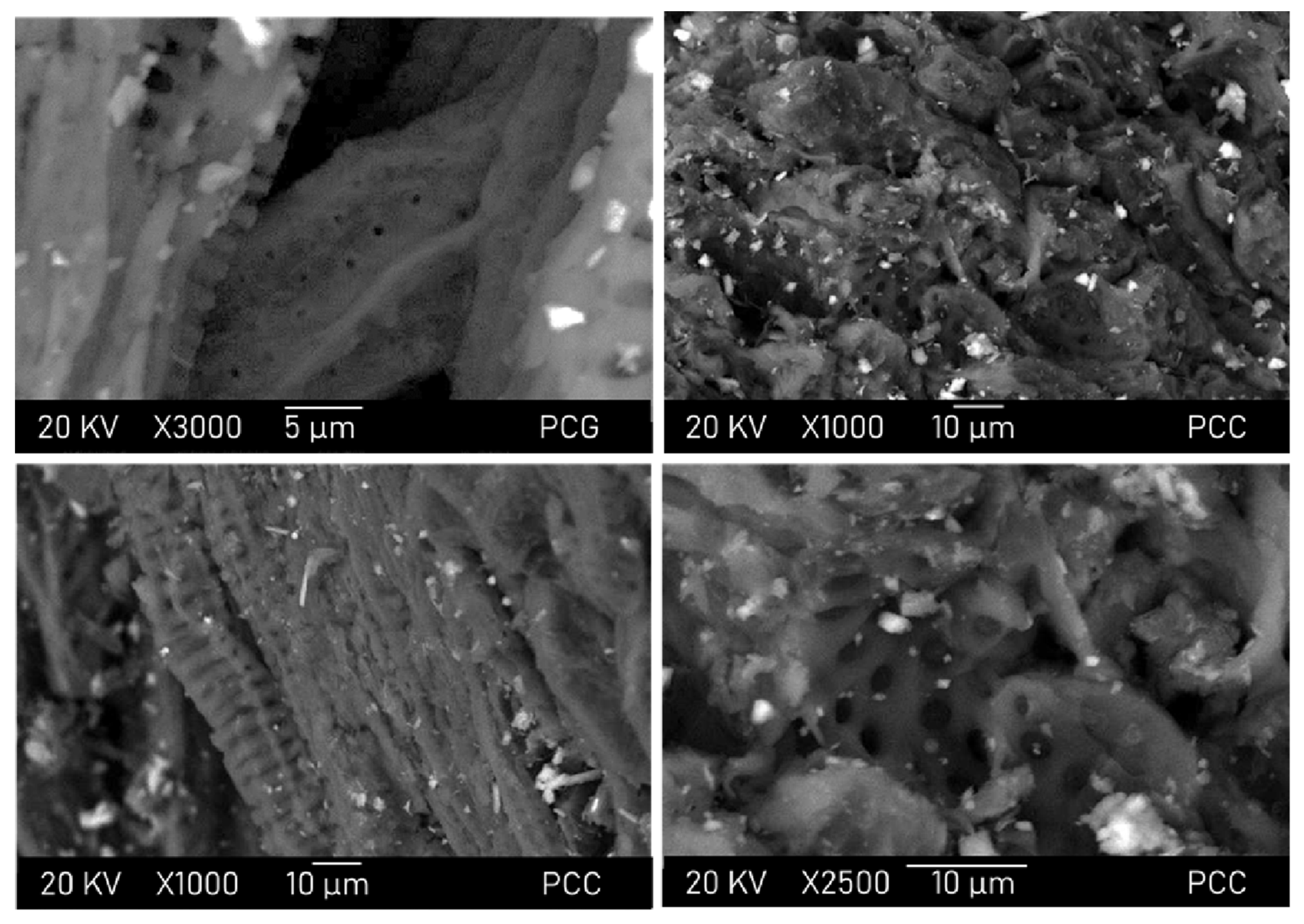

2.2. Activated Carbon Characterization

2.3. Calculation of Yield

- WAC: AC final weight

- W0: Dried biomass weight

2.4. Biodiesel Production

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chiang, P.F.; Zhang, T.; Claire, M.J.; Maurice, N.J.; Ahmed, J.; Giwa, A.S. Assessment of solid waste management and decarbonization strategies. Processes 2024, 12, 1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, H.; Gable, J.J.; Park, J.K. Evaluation of organic waste diversion alternatives for greenhouse gas reduction. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2012, 60, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secretaría de Agricultura y Desarrollo Rural. Prensa. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/agricultura/prensa/crece-16-2-produccion-de-pina-en-mexico-durante-2020?idiom=es (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Kamusoko, R.; Mukumba, P. Pineapple waste biorefinery: An integrated system for production of biogas and marketable products in South Africa. Biomass 2025, 5, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajien, A.; Idris, J.; Md Sofwan, N.; Husen, R.; Seli, H. Coconut shell and husk biochar: A review of production and activation technology, economic, financial aspect and application. Waste Manag. Res. 2023, 41, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aili Hamzah, A.F.; Hamzah, M.H.; Che Man, H.; Jamali, N.S.; Siajam, S.I.; Ismail, M.H. Recent updates on the conversion of pineapple waste (Ananas comosus) to value-added products, future perspectives and challenges. Agronomy 2021, 11, 2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Chen, M.; Ma, L.; Yang, B.; Li, L.; Liu, Q. Optimized preparation of activated carbon from coconut shell and municipal sludge. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2020, 241, 122–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejia, M.V.V. Potencial de residuos agroindustriales para la síntesis de Carbón Activado: Una revisión. Sci. Tech. 2018, 23, 411–419. [Google Scholar]

- Blachnio, M.; Derylo-Marczewska, A.; Charmas, B.; Zienkiewicz-Strzalka, M.; Bogatyrov, V.; Galaburda, M. Activated carbon from agricultural wastes for adsorption of organic pollutants. Molecules 2020, 25, 5105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhyani, V.; Bhaskar, T. A comprehensive review on the pyrolysis of lignocellulosic biomass. Renew. Energy 2018, 129, 695–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, S.D.; Mukherjee, D.; Kuila, D. CO2 Capture using Activated Carbon Derived from Avocado Seeds and Sawdust: A Comparative Study on Adsorption Performance and Surface Properties. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 5, 117643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gale, M.; Nguyen, T.; Moreno, M.; Gilliard-Abdulaziz, K.L. Physiochemical Properties of Biochar and Activated Carbon from Biomass Residue: Influence of Process Conditions to Adsorbent Properties. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 10224–10233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colomba, A.; Berruti, F.; Briens, C. Model for the physical activation of biochar to activated carbon. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2022, 168, 105769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Kim, J.; Hyeon, T. Recent progress in the synthesis of porous carbon materials. Adv. Mater. 2006, 18, 2073–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Yu, Q.; Cui, Y.; Xie, F.; Li, W.; Li, Y.; Chen, M. Adsorption properties of activated carbon from reed with a high adsorption capacity. Ecol. Eng. 2017, 102, 443–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Das, R.; Sangwan, S.; Rohatgi, B.; Khanam, R.; Peera, S.P.G.; Misra, S. Utilisation of agro-industrial waste for sustainable green production: A review. Environ. Sustain. 2021, 4, 619–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallejo, F.; Yánez, D.; Díaz-Robles, L.; Oyaneder, M.; Alejandro-Martín, S.; Zalakeviciute, R.; Romero, T. Valorizing Biomass Waste: Hydrothermal Carbonization and Chemical Activation for Activated Carbon Production. Biomass 2025, 5, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titiladunayo, I.F.; McDonald, A.G.; Fapetu, O.P. Effect of temperature on biochar product yield from selected lignocellulosic biomass in a pyrolysis process. Waste Biomass Valorization 2012, 3, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libra, J.A.; Ro, K.S.; Kammann, C.; Funke, A.; Berge, N.D.; Neubauer, Y.; Titirici, M.M.; Fühner, C.; Bens, O.; Kern, J.; et al. Hydrothermal carbonization of biomass residuals: A comparative review of the chemistry, processes and applications of wet and dry pyrolysis. Biofuels 2011, 2, 71–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volpe, M.; Messineo, A.; Mäkelä, M.; Barr, M.R.; Volpe, R.; Corrado, C.; Fiori, L. Reactivity of cellulose during hydrothermal carbonization of lignocellulosic biomass. Fuel Process Technol. 2020, 206, 106456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevilla, M.; Fuertes, A.B. The production of carbon materials by hydrothermal carbonization of cellulose. Carbon 2009, 47, 2281–2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olszewski, M.P.; Nicolae, S.A.; Arauzo, P.J.; Titirici, M.M.; Kruse, A. Wet and dry? Influence of hydrothermal carbonization on the pyrolysis of spent grains. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 260, 121101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S.; Aktay, N.; Alptekin, F.M.; Celiktas, M.S.; Dunford, N.T. Effect of Process Parameters and Biomass Type on Properties of Carbon Produced by Pyrolysis. Biomass 2025, 5, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhetri, A.B.; Watts, K.C.; Islam, M.R. Waste cooking oil as an alternate feedstock for biodiesel production. Energies 2008, 1, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, J.M.; Alvim-Ferraz, M.C.M.; Almeida, M.F. Production of biodiesel from acid waste lard. Biores. Technol. 2009, 100, 6355–6361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibeto, C.; Ofoefule, A.; Ezeugwu, H. Fuel quality assessment of biodiesel produced from groundnut oil (Arachis hypogea) and its blend with petroleum diesel. Am. J. Food Technol. 2011, 6, 798–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Predojević, Z.J. The production of biodiesel from waste frying oils: A comparison of different purification steps. Fuel 2008, 87, 3522–3528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, Y.C.; Singh, B.; Upadhyay, S.N. Advancements in development and characterization of biodiesel: A review. Fuel 2008, 87, 2355–2373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, J.H. Green chemistry: Challenges and opportunities. Green Chem. 2007, 9, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales Troyo, F. Análisis del Ciclo de Vida de la Producción de Biodiesel a Partir de Aceite Usado. Master’s Thesis, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Mexico City, Mexico, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Khuong, D.A.; Trinh, K.T.; Nakaoka, Y.; Tsubota, T.; Tashima, D.; Nguyen, H.N.; Tanaka, D. The investigation of activated carbon by K2CO3 activation: Micropores-and macropores-dominated structure. Chemosphere 2022, 299, 134365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oni, B.A.; Abatan, O.G.; Busari, A.; Odunlami, O.; Nweke, C. Production and characterization of activated carbon from pineapple waste for treatment of kitchen wastewater. Desalination Water Treat. 2020, 183, 413–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Yan, R.; Chen, H.; Lee, D.H.; Zheng, C. Characteristics of hemicellulose, cellulose and lignin pyrolysis. Fuel 2007, 86, 1781–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Wang, L. Technologies for Biochemical Conversion of Biomass; Academic Press Publication: Cambridge, MA, USA; Elsevier Inc.: Oxford, UK, 2016; pp. 3–7. [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi, M.; Sahu, J.N.; Ganesan, P. Effect of process parameters on production of biochar from biomass waste through pyrolysis: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 55, 467–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosheleva, R.I.; Mitropoulos, A.C.; Kyzas, G.Z. Synthesis of activated carbon from food waste. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2019, 17, 429–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, T.Y.; Arumugam, S.D.; Latip, N.H.A.; Abdullah, A.M.; Latif, P.A. Effect of activation temperature and heating duration on physical characteristics of activated carbon prepared from agriculture waste. Environ. ASIA 2010, 3, 143–148. [Google Scholar]

- Dıaz-Teran, J.; Nevskaia, D.M.; López-Peinado, A.J.; Jerez, A. Porosity and adsorption properties of an activated charcoal. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2001, 187, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, R.; Aslam, Z.; Shawabkeh, R.A.; Asghar, A.; Hussein, I.A. BET, FTIR, and RAMAN characterizations of activated carbon from waste oil fly ash. Turk. J. Chem. 2020, 44, 279–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, G.M.; Cipriano, D.F.; Schettino, M.A., Jr.; Cunha, A.G.; Coelho, E.R.C.; Freitas, J.C.C. One-step methodology for preparing physically activated biocarbons from agricultural biomass waste. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 103113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yacob, A.R.; Azmi, A.; Amat Mustajab, M.K.A. Physical and chemical activation effect on activated carbon prepared from local pineapple waste. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2015, 699, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavia, D.L.; Lampman, G.M.; Kriz, G.S.; Vyvyan, J.R. Introduction to Spectroscopy, 5th ed.; Cengage Learning: Stamford, CT, USA, 2015; pp. 14–87. [Google Scholar]

- Das, D.; Samal, D.P.; Meikap, B.C. Preparation of activated carbon from green coconut shell and its characterization. J. Chem. Eng. Process Technol. 2015, 6, 1000248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrios, M.; Skelton, R.L. Comparison of purification methods for biodiesel. Chem. Eng. J. 2008, 144, 459–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, J. A Membrane Separation Process for Biodiesel Purification. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kirk, R.S.; Sawyer, R.; Egan, H. Composición y Análisis de Alimentos; Décima primera reimpresión; Grupo Editorial Patria: Mexico City, Mexico, 2011; pp. 706–710. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, W.M.; Medeiros, N.J.; Boyd, D.J.; Snell, J.R. Biodiesel transesterification kinetics monitored by pH measurement. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 136, 771–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atadashi, I.M.; Aroua, M.K.; Aziz, A.A.; Sulaiman, N.M.N. Refining technologies for the purification of crude biodiesel. Appl. Energy 2011, 88, 4239–4251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, F.; Shahzadi, A.; El Zerey-Belaskri, A.; Abbas, Z. Conventional and advanced purification techniques for crude biodiesel—A critical review. Int. J. Chem. Biochem. Sci. 2017, 12, 113–121. [Google Scholar]

| % Residual Oil | Oil Acidity | % FFA |

|---|---|---|

| 100 | 2.26 | 1.14 |

| 75 | 2.02 | 1.02 |

| 50 | 1.79 | 0.91 |

| 25 | 1.51 | 0.79 |

| 0 | 1.38 | 0.65 |

| Blank | 0.4 | 0.23 |

| Property | Astm Method | Limit | Units | Before AC | After AC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flash point Water and sediment Kinematic viscosity 40 °C Cloud point | D 93 | 93 min–370 max | °C | 125.00 | 125.00 |

| D 2709 | 0.05 max | %V | 0.09 | 0.02 | |

| D 445 | 1.9–6.0 | mm2/s | 3.90 | 3.70 | |

| D 2500 | Variable | °C | −1.00 | −4.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

García-Ruiz, D.L.; Valencia-Delgado, D.S.; Hernández-Ocaña, S.M.; Ortega-Varela, L.F.; Domratcheva-Lvova, L.; Morales-Troyo, F.; Solana-Reyes, Y.; Gutiérrez-García, C.J. Green Synthesis of Activated Carbon from Waste Biomass for Biodiesel Dry Wash. Biomass 2026, 6, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomass6010003

García-Ruiz DL, Valencia-Delgado DS, Hernández-Ocaña SM, Ortega-Varela LF, Domratcheva-Lvova L, Morales-Troyo F, Solana-Reyes Y, Gutiérrez-García CJ. Green Synthesis of Activated Carbon from Waste Biomass for Biodiesel Dry Wash. Biomass. 2026; 6(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomass6010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarcía-Ruiz, Diana Litzajaya, Dylan Sinhue Valencia-Delgado, Salvador Moisés Hernández-Ocaña, Luis Fernando Ortega-Varela, Lada Domratcheva-Lvova, Fermín Morales-Troyo, Yadira Solana-Reyes, and Carmen Judith Gutiérrez-García. 2026. "Green Synthesis of Activated Carbon from Waste Biomass for Biodiesel Dry Wash" Biomass 6, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomass6010003

APA StyleGarcía-Ruiz, D. L., Valencia-Delgado, D. S., Hernández-Ocaña, S. M., Ortega-Varela, L. F., Domratcheva-Lvova, L., Morales-Troyo, F., Solana-Reyes, Y., & Gutiérrez-García, C. J. (2026). Green Synthesis of Activated Carbon from Waste Biomass for Biodiesel Dry Wash. Biomass, 6(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomass6010003