Abstract

This review critically examines the implementation of Universal Design for Learning (UDL) in science education, providing an integrative overview of research, methodologies, and disciplinary applications. The first section explores UDL across educational stages—from early childhood to higher education—highlighting how age-specific adaptations, such as play-based and outdoor learning in early years or language- and problem-focused strategies in secondary education, enhance engagement and equity. The second section analyses science-specific pedagogies, including inquiry-based science education, the 5E model (Engage, Explore, Explain, Elaborate, Evaluate), STEM/STEAM approaches, and gamification, demonstrating how their alignment with UDL principles fosters motivation, creativity, and metacognitive development. The third section addresses the application of UDL across scientific disciplines—biology, physics, chemistry, geosciences, environmental education, and the Nature of Science—illustrating discipline-oriented adaptations and inclusive practices. Finally, a section on multiple scenarios of diversity synthesizes UDL responses to physical, sensory, and learning difficulties, neurodivergence, giftedness, and socio-emotional barriers. The review concludes by calling for enhanced teacher preparation and providing key ideas for professionals who want to implement UDL in science contexts.

1. Introduction

1.1. Understanding Universal Design for Learning: A Comprehensive Definition

Universal Design for Learning (UDL) is a theoretical and practical framework developed in 1984 by the Center for Applied Special Technology (CAST), aiming to enhance learning for all students [1]. Interestingly, the term “universal design” did not originate in the field of education but in architecture. Architect Ron Mace and his colleagues coined it to describe products and environments designed to be usable by all people to the greatest extent possible (e.g., curb-cut sidewalks) [2]. Building on this foundational idea, CAST has progressively refined and expanded the UDL model. Over time, the framework has evolved from its early focus on reducing cognitive and physical barriers [1,3] to a broader commitment to achieving social justice through the elimination of prejudice and systemic exclusion [4]. A concise overview of UDL’s historical development is provided by Schreffler et al. (2019) [5].

The central premise of UDL is that many barriers to learning are not inherent to students’ abilities but often arise from their interaction with rigid educational materials and methods [2]. This perspective reverses the traditional viewpoint arguing that it is curricula that require modification—not the learners themselves [6]. The framework adopts an interdisciplinary foundation, drawing from neuroscience, pedagogy, and psychology [7]. Its ultimate goal is to develop expert learners who are, each in their own way, resourceful, knowledgeable, strategic, goal-directed, purposeful, and motivated [1].

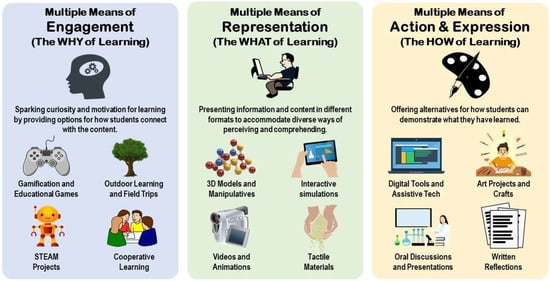

The UDL model is structured around three core principles, which are elaborated into nine guidelines and thirty-six checkpoints [4]. The first principle, providing multiple means of engagement (the why of learning), focuses on sustaining interest, offering appropriate challenges, and enhancing motivation. This is accomplished by employing approaches that enhance learners’ autonomy and decision-making, encourage cooperative engagement and a sense of community, guarantee the meaningfulness and real-world applicability of tasks, and support the development of reflective thinking and emotional self-management. The second principle, providing multiple means of representation (the what of learning), addresses the diverse ways that students perceive and comprehend information. It entails delivering material through diverse formats, elucidating key terms and symbols, providing alternatives for tailoring how information is presented, and drawing on learners’ existing knowledge to facilitate the acquisition of new concepts. The third principle, providing multiple means of action and expression (the how of learning), acknowledges that students differ in how they navigate learning environments and demonstrate understanding. These strategies encompass enhancing the availability of assistive tools, employing a range of media for communication and content creation, supplying diverse options for how learners can respond, and providing structured support for setting goals, organizing tasks, and tracking progress.

Several parallel frameworks have been developed, inspired by UDL. In 2001, researchers at the University of Connecticut expanded UDL principles to design the Universal Design for Instruction (UDI), which articulates nine principles aimed at enhancing accessibility in higher education [8]. UDI emphasizes flexibility, tolerance for error, adequate space, and an inclusive climate. Another derivative model, the Universal Design of Assessment, draws from UDL to promote inclusive evaluation practices [9], seeking to measure students’ actual competencies rather than limitations arising from format, language, or testing conditions. Although this paper focuses primarily on UDL, other pedagogical approaches also address classroom diversity, including Culturally Relevant Pedagogy, Culturally Responsive Teaching, and Differentiated Instruction [10].

The implementation of UDL is justified by the need to remove barriers within learning environments to ensure equitable access to education for all students [11]. Moreover, Sustainable Development Goals 4 and 10—Quality Education and Reducing Inequalities—represent core priorities in the United Nations Agenda, urging global efforts toward inclusive education [12]. Today, UDL has been widely adopted as an approach for creating equitable and responsive learning environments [13]. While several authors have documented its benefits [14], others question its effectiveness, noting a lack of sufficient empirical evidence to fully substantiate its outcomes [15]. Most studies focus on students’ perceptions [16] and tend to emphasize the principle of representation over the rest of the principles or measurable learning outcomes [17,18]. Furthermore, critical questions remain unresolved, such as the adequate “dosage” of UDL interventions [9], the potential role of technology [19], and how to systematically assess them [20].

1.2. Examining the Relevance of UDL in Science Education

Scientific literacy constitutes a fundamental competency in modern society, especially in light of the growing range of science- and technology-related challenges [21]. It comprises the knowledge and comprehension of scientific ideas and methods needed for well-informed personal choices, meaningful engagement in civic and cultural life, and effective contribution to economic activity [22]. Although science learning presents challenges for all students, these challenges are often magnified for learners who struggle with reading and writing or who exhibit low motivation toward science learning [23]. Science subjects frequently involve abstract and complex content, and students often hold misconceptions that interfere with conceptual understanding [24]. Many learners also encounter difficulties using scientific terminology to describe or explain concepts, as limited science vocabulary has been identified as a persistent barrier in the literature [25]. Lemke (1990) [26] argues that learners are rarely taught how to “talk science,” a skill required to discuss, explore, investigate, and express scientific ideas both orally and in writing. Furthermore, experiments and laboratory procedures can be challenging because they require students to integrate conceptual reasoning with methodological processes [27]. In addition to these general obstacles, students with learning or physical difficulties face extra barriers and often perform below their peers in science courses [28].

A significant precursor study that provided insights and best practices for improving accessibility in science education was the book Creating a Culture of Accessibility in the Sciences [29]. Since then, several studies have demonstrated that UDL-based science lessons can enhance accessibility, self-regulation, and classroom attention [5]. Moore et al. (2020) [30] further recommended that team-based learning, when aligned with UDL guidelines, can be particularly beneficial for students. In Figure 1, several examples of science-class methodologies are aligned with the UDL principles.

Figure 1.

Examples of science-class methodologies adjusted to the three UDL principles.

Despite these contributions, there remains a shortage of studies directly linking inclusion and science education [31], and, to our knowledge, comprehensive reviews addressing this relationship under different perspectives remain scarce.

In response to this gap, the present narrative review aims to synthesize the most relevant findings connecting UDL with science education. It analyzes the impact of UDL implementation across four dimensions: educational stages, science-specific methodologies, disciplinary applications, and diverse inclusion scenarios. This integrative and multimodal approach seeks to identify best practices for applying UDL in science classrooms while also highlighting existing limitations and directions for future research. The studies included in this review were selected according to the following criteria: empirical or theoretical works published in peer-reviewed journals or scholarly books between 1990 and 2025; explicit relevance to the implementation of UDL within science education across the four focal dimensions; and availability in English. The literature was identified through targeted keyword searches in major academic databases (Web of Science, Scopus, and Google Scholar), complemented by backward citation analysis. Throughout this review, the term “disability”, which is quite common in the literature, has been purposely substituted by “difficulty” or “access limitation”, since the authors align with the idea that it is the curricula that require modification, not the learners themselves, and difficulties appear when learning methodologies are not well adjusted to them.

2. Exploring Connections Between UDL and Science Education

2.1. Educational Stages: Addressing Age-Specific Needs

From the earliest stages of development, many children demonstrate the capacity to act as “little scientists,” formulating hypotheses, designing experiments, and recognizing patterns through play [32]. According to the six principles articulated by the National Science Teachers Association (NSTA), recognizing children’s natural ability to engage in scientific inquiry and the crucial role of adults in providing supportive environments are fundamental pillars of quality early science education. These innate abilities must therefore be nurtured through diverse and engaging experiences [32].

Early stimulation has long-term benefits, as it predicts higher academic achievement in later years [33]. Considering that many science achievement gaps emerge in early childhood and persist throughout schooling [34], ensuring that all children have equitable opportunities to engage in meaningful science learning is essential. Although research on UDL in early childhood education is still limited [16], evidence suggests that it can be highly effective for young learners [35].

Lohmann et al. (2023) [36] propose a detailed alignment between UDL principles and early science activities. For multiple means of engagement, they recommend integrating children’s interests, fostering social connections, encouraging physical movement, and providing choice opportunities. For multiple means of representation, they emphasize using books, experiments, puzzles, manipulatives, and technology. For multiple means of action and expression, they highlight oral discussions, crafts, art projects, and digital tools. The learning environment itself is also critical: for instance, it was found that kindergarten children with difficulties were less distracted and more on-task in outdoor classrooms than in traditional indoor settings [37]. Outdoor environments thus provide privileged spaces for exploring natural phenomena [38].

At the primary level, several studies indicate that students perform better in science when taught using UDL approaches compared with traditional methods [39]. The importance of addressing language difficulties, the memory demands of multistep processes (such as digital submissions), cultural diversity—avoiding assumptions about shared background knowledge—and routines was underscored by certain authors [40]. Teachers should provide explicit instruction on recording observations and explanations, while also offering a variety of resources for information gathering. In this regard, students perceive technology as a valuable tool [41]. According to Gaunt et al. (2025) [42], game-based learning and accessible video materials are particularly effective for operationalizing UDL principles in primary science classrooms. Outdoor learning also provides, at this stage, significant benefits by offering hands-on and interactive experiences that reduce barriers for students who may struggle in more constrained indoor settings [43]. While research explicitly connecting UDL and outdoor learning remains scarce, some studies demonstrate encouraging results in early-year contexts, marking a fruitful avenue for future exploration [44].

In secondary education, teachers report greater difficulty implementing UDL principles than their primary-level counterparts, suggesting that certain aspects of the framework may be more challenging in science contexts requiring specific demonstrations and assessments [45]. Two strategies have proven particularly effective in promoting equitable access at this level: the problem-solving approach and an emphasis on language and literacy in science [42]. Kaur and Prendergast (2023) [46] found that encouraging written reflection on problem-solving processes allowed students to demonstrate understanding through multiple means of action and expression. These interventions increased students’ enjoyment, self-confidence, and metacognitive thinking.

At the university level, it is important to distinguish between UDL applications within science disciplines and within science teacher education programs. In the former, numerous barriers have been identified, including large class sizes, rapid instructional pace, lack of curricular scaffolding, the precision of content, and limited pedagogical flexibility among faculty from science degrees [47]. Moreover, research indicates that science university instructors might be less supportive of classroom accommodations and hold more negative perceptions of disabled students than faculty in other disciplines [48].

In the latter case—teacher education—there is a need to integrate scientific and inclusive perspectives to prepare future educators capable of applying UDL principles effectively [49]. This requires targeted training, as adapting science content to make it accessible for all learners represents a major shift from traditional teaching practices [50]. Studies show that inclusive-education training improves preservice teachers’ attitudes, knowledge, and strategy use [51]. Positive teacher attitudes [52] and stronger knowledge of inclusive education [53] are key to successful implementation. Moreover, such preparation not only builds teachers’ confidence in applying UDL principles but also benefits their own professional learning [54]. Encouraging positive attitudes toward science among preservice teachers is equally crucial, since negative perceptions may be transmitted to their future students [55,56,57].

2.2. Science Methodologies Require Specific UDL Approaches

2.2.1. Inquiry-Based Science Education

Inquiry is defined as learners asking meaningful questions about the natural and designed world, gathering evidence to answer those questions through systematic investigation, and communicating findings based on that evidence [58]. Tsaliki et al. (2022) [59] argue that Inquiry-Based Science Education (IBSE) provides a valuable foundation for students to understand the process of scientific innovation, familiarize themselves with scientific concepts and methodologies, and develop scientific literacy. As a critical approach to learning, inquiry science plays a central role in cultivating informed citizens capable of evidence-based decision-making [60]. Despite its recognized benefits, research on training preservice teachers in IBSE and inclusive practices remains limited [61].

IBSE encompasses a spectrum from open inquiry, in which students explore with minimal guidance, to guided or structured inquiry approaches, where scaffolds support learning while preserving autonomy [62]. Open inquiry can overwhelm students, leading to misconceptions or errors in experimentation [63]. Conversely, structured inquiry with explicit support has been identified as the most effective method for instructing students with difficulties [64]. These approaches provide specific feedback and teacher-directed scaffolds that are gradually removed as students gain mastery [65,66]. Additional strategies to enhance IBSE include hands-on activities, spatial organizers, peer mediation, and formative assessment [67,68].

Model-based learning within IBSE further facilitates three-dimensional learning and conceptual understanding [69]. Resources for model-based practices, including scaffolding tools and lesson planning guides, are available through initiatives such as Ambitious Science Teaching [70].

The integration of UDL with instructional inquiry models such as the 5E Model seems to improve learning outcomes for diverse learners [71]. While the 5E Model actively engages students with content, UDL ensures that learning is accessible at every stage. Emerging evidence suggests that the 5E-UDL combination is effective for students with learning difficulties [69,72].

Nevertheless, teachers often report feeling insufficiently prepared to implement IBSE in diverse classrooms. Practical guidance for adapting inquiry to heterogeneous learners can be found in several works [73,74], which provide strategies and scaffolds to facilitate inclusive science teaching.

2.2.2. STEM and STEAM Approaches

Active learning encompasses instructional approaches in which students are engaged in meaningful activities and encouraged to reflect on their learning, rather than passively receiving information [75]. Research demonstrates that active learning positively impacts student learning outcomes and performance [76]. Among active learning methodologies, STEM (an educational approach that focuses on Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) and STEAM (STEM version including the A for Arts) are particularly notable, distinguishing them from broader active learning practices applicable in non-scientific contexts.

Within the framework of UDL, STEAM approaches are considered particularly appropriate, since several studies suggest they facilitate educational innovation and accommodate diverse cognitive styles and ways of thinking [77]. Specific implementations have shown the potential of STEAM-based instruction to enhance students’ scientific reasoning and critical thinking, problem-solving skills, motivation, collaboration among peers and with teachers, and the application of knowledge in inclusive arts-related contexts [78]. Additional benefits include the enhancement of creativity and empathy [79,80], increased student interest in science careers [81], and a reduction in the gender gap and confidence gains among girls in science [82].

Given that problem-solving can be particularly challenging for students with difficulties [83], teachers are encouraged to implement evidence-based practices, including explicit instruction [84], scaffolding [85], and the integration of technology tools such as iPads, multimedia resources, and specialized software to support content acquisition and metacognitive skill development [86]. Programs combining UDL and multiple intelligence approaches have been related to a greater success in fostering positive student attitudes toward STEM compared with traditional programs [87].

STEM instruction can be implemented in early childhood education [88]. At this stage, several authors advocate for a STEAM rather than a strictly STEM approach, as art-based activities are particularly engaging for young children [32]. In primary education, several studies suggest that the integration of STEAM projects enhances learning, promotes active participation, and fosters self-reflection [78], particularly when complemented by science-related community events such as festivals [89]. It has been found that some approaches to STEM do not fully leverage the potential of UDL principles [90].

Practical examples of inclusive STEAM implementations can be found in Jesionkowska et al. (2020) [91], Basham & Marino (2013) [86], Moon et al. (2012) [92], and Drigas & Kefalis (2024) [93], offering guidance for adapting STEM projects to diverse learner needs. Resources such as videos, presentations, and other guides can be found in AccessSTEM (2002–2013) [94].

2.2.3. Other Active Learning Methodologies for Science

In addition to STEM and STEAM, several active learning methodologies with a broader focus can be adapted for science education, including gamification, flipped classrooms, Problem-Based Learning (PBL), and cooperative learning (CL), among others. These approaches are designed to provide flexibility in teaching, allowing adaptation to students’ diverse needs and learning levels [95,96]. Gamification involves the integration of game elements into non-game contexts [97], while game-based learning (GBL) uses games as the primary medium for instruction [98]. The literature indicates that gamification and GBL can enhance science learning for diverse learners by offering immediate feedback, adaptive learning paths, and interactive experiences [99]. However, these approaches are not inherently inclusive and require intentional design to align with UDL principles. Effective applications combining UDL with gamification or GBL include immersive inquiry experiences [61] and robotics projects [100]. Hunt et al. (2022) [101] emphasize the importance of post-game reflection sessions to consolidate understanding and promote deeper learning. While many of these initiatives lack a robust theoretical foundation, recent developments such as Systemic Gamification Theory (SGT) provide a framework to guide inclusion in gamified contexts [102]. Emerging trends in personalized gamification, which adapt game experiences to different player types, also hold promise for alignment with UDL [103]. Drigas & Kefalis (2024) [93] proposed the STREAMING framework, integrating Science, Technology, Robotics, Engineering, Artificial Intelligence, Mathematics, Emotional Intelligence, Inclusion, and Gamification as an innovative model for inclusive STEAM education.

CL represents another instructional methodology particularly compatible with UDL principles. Evidence suggests that CL enhances academic performance, fosters student engagement, and encourages exploration [104]. Examples of successful implementation include undergraduate health science courses applying UDL-informed cooperative strategies [105] and primary science classrooms promoting inclusive participation [69]. Flipped classroom designs further complement team-based approaches. Terson de Paleville (2024) [106] outlines a three-step inclusive model for physiology courses: (1) a preparation phase with diverse learning resources, assessments, and virtual labs; (2) a readiness assurance phase involving individual and group testing followed by teacher feedback; and (3) an application phase requiring students to solve assignments collaboratively, applying acquired knowledge.

2.3. Science Disciplines: A Broad Range of Possibilities

Applying UDL in scientific subjects presents unique challenges, as highlighted by Curry et al. (2006) [107]. This section provides an overview of the state of the art in UDL implementation across major scientific disciplines, offering valuable references for researchers and educators.

In biology, UDL-aligned instruction might promote active learning and the development of scientific skills [108]. Notable applications include introductory biology [109], evolution lessons in primary [41] and university education [110], online teaching [111], health sciences [112], and anatomy [113]. Some studies highlight the importance of careful instructional design to ensure the effectiveness of these proposals, while some succeed in increasing student motivation without yielding significant improvements in academic performance [114]; others apply UDL without explicit recognition or systematic planning [113]. Effective strategies include cogenerative dialogue [115], student-created inclusive materials [110], and the integration of technology [112].

In physics, research-based introductory physics curricula have historically lacked guidance supporting students with difficulties [116]. To address this situation, in 2008, the Institute of Physics published a guide of good practices [117], and later, in 2021, the American Association of Physics Teachers (AAPT) published a paper specifying how to transform physics labs into accessible spaces [118]. More recently, a very complete list of methodologies to adapt UDL to this area was proposed by Lannan et al. (2021) [119] and Chini & Scanlon (2023) [120], including adaptations to labs, tools, and practices. Some interesting implementations can be found in Bustamante et al. (2021) [121], Atika et al. (2025) [122], and Barrón-Hernández & Ramírez-Díaz (2023) [123]. Multiple physics examples in primary education are provided in Hanuscin & Van Garderen (2020) [73].

In chemistry, UDL applications include 3D atomic models, technological tools, task choices, and real-life links [124]. Evidence shows improvements in the performance of students with learning difficulties [125]. Rosmi and Jauhari (2022) [126] emphasize that teachers require substantial experience to effectively apply UDL principles within the chemistry-learning process. Indeed, achieving adequate preparation is demanding; although a specialized course designed to train chemistry teachers in UDL practices led to improved use of diverse modes of representation, significant gains in student engagement and in the adoption of varied assessment strategies were still limited [127]. Nevertheless, certain inclusive initiatives incorporating digital resources have yielded positive outcomes, such as the implementation of inclusive software in secondary education [128] or in universities [129]. In the latter example, students appreciated that content was delivered in multiple ways, such as through animations, interactive simulations and videos, and the chance to evaluate themselves. In Miller & Lang (2016) [130], the challenge of reducing lab stress was considered, taking into account UDL, and special importance was placed on providing supportive communication.

When it comes to the geosciences, a review on UDL implementation can be found in Higgins & Maxwell (2021) [131]. In this domain, barriers that students face consist of limitations in visiting field sites, laboratory procedures, classroom activities, and other personal circumstances [132,133]. One of the main problems here is that instructors lack knowledge on how to find a good balance between accommodation and fieldwork learning goals [134]. In order to improve fieldwork inclusivity, experience shows that multisensory engagement, consideration of pace and timing, flexibility of access and delivery, and a focus on shared tasks are important aspects to take into account [135]. Apart from field trips, other interesting proposals have been inclusive workshops [136,137] and geocaching challenges [138].

In environmental education, in the context of sustainability, some relevant contributions insist on the importance of making outdoor spaces more welcoming for all learners [139]. Aguilar et al. (2017) [140] highlight the potential of urban spaces to make outdoor learning more accessible for everybody. Other interesting proposals can be found related to the design of inclusive materials in the domain of sustainable cities [141] or primary-education activities to raise environmental awareness and care [138].

Finally, Nature of Science (NoS) education is crucial for understanding science’s role in society (how scientific knowledge is produced and how to interpret socio-scientific issues) and to promote interest in science (through the vision of science as a human activity) [142]. NoS presents pedagogical challenges including high cognitive demands and the use of sophisticated thinking skills [143]. However, students can be supported through inclusive strategies [9], such as educational games [144].

2.4. Multiple Scenarios of Diversity

Although UDL aims to benefit all students, it is particularly essential to prioritize learners with special needs during instructional design [145].

For students with physical access needs, UDL implementation in science has inspired numerous investigations. For example, students with visual impairments can benefit from two- and three-dimensional models, such as models of molecules [124], cells [146], embryo development [147], tactile phylogenetic trees [148], and physical concepts [149]. Other strategies imply the use of extended reality tools [150] and adapted science textbooks [151]. Deaf students particularly benefit from visual and kinesthetic learning opportunities [152]. Students with mobility impairments find fieldwork or laboratory procedures especially difficult. In these cases, teamwork and specific distribution of duties might be effective [92].

Regarding learning difficulties, the neurodiversity paradigm emphasizes that cognitive variations are natural and valuable, resisting pathologizing definitions [153]. Educational environments that fail to accommodate diverse processing styles create barriers and require adjustment [154]. Neurodiversity includes learners with autism, ADHD (Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder), OCD (Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder), dyspraxia, dyslexia, dyscalculia, and developmental language disorders [155]. Tailored adaptations vary by condition, with comprehensive examples summarized in Kryukova et al. (2023) [156]. In the case of autism, personal interests in a maker program [157] and structured routines in a STEM project [158] produced favorable outcomes. Computer assistance might be adequate for learners with ADHD [159], while structured guidelines might be helpful for those with OCD [160]. Visual images, concept mapping, virtual learning environment, and global/sequential teaching styles have demonstrated positive outcomes in cases of dyspraxia and dyslexia [161]. For dyscalculia, digital manipulatives represent an efficient tool [162]. Multimodal representation, the arts, and communicative technologies support learners with developmental language disorders [163].

For slow learners, materials with engaging visuals, simplified language, pictorial representations [164], and flexible pacing through adapted notebooks [23] have proven effective. On the other hand, it is also important to consider fast or gifted learners, providing opportunities for active engagement through collaborative activities [165]. Finally, attention should be given to students affected by social stigma or stereotype threat, which can negatively impact learning [166,167,168]. Personalization, emotional connection, and creative, artistic approaches can enhance motivation for these students [169,170,171].

3. Conclusions and Prospects

The present review constitutes a valuable contribution to guide science teachers in understanding and implementing UDL in their classrooms. Its main contributions lie in the identification of age-specific strategies that effectively support inclusive science learning; a detailed synthesis of UDL-aligned methodologies and resources specifically adapted to science teaching (IBSE, the 5E instructional model, and STEM/STEAM approaches); the highlighting of promising directions such as gamification, CL, and flipped-classroom designs; a discipline-specific overview that clarifies how UDL can be implemented in biology, physics, chemistry, geosciences, environmental education, and in NoS activities; and the exemplification of UDL application across multiple scenarios of diversity within science-class contexts.

Although in recent years there has been a clear increase in publications relating UDL to science teaching, this area of knowledge is still in its early stages. As described in the review, most studies focus on students’ perceptions following UDL implementation, while very few measure learning outcomes. This represents an important shift required to genuinely understand UDL’s effectiveness in science-learning contexts. Similarly to what occurs with gamification, if designs are not well defined, any observed benefits may be attributable primarily to increases in student motivation, with no corresponding effects on learning results. More specific guidelines and empirical data are therefore necessary to support science teachers in adequately implementing UDL, since many studies are still not truly connected to the theoretical framework or apply it only superficially.

One major concern identified throughout the review is the lack of training among science-education professionals in methodologies for managing diversity. UDL is commonly addressed through specific subjects in early childhood and primary-education degree programs; however, greater emphasis should be placed on disciplinary applications of UDL and on the relationship between UDL and innovative methodologies such as gamification, CL, and flipped-classroom approaches. Arguably, secondary school teachers are not as well equipped to address the challenges of diversity within their science disciplines. Programs training secondary school science teachers should therefore include not only disciplinary content and its didactics but also fundamental notions and practical experiences related to inclusive education, especially those connected to IBSE and STEAM approaches. Furthermore, faculty members within science degrees—among whom resistance to inclusive practices is more frequently documented—should be offered targeted seminars and workshops to develop sensitivity toward diversity and a willingness to adopt inclusive methodologies.

This sensitivity is an important element to strengthen, as teachers who hold positive views on diversity are more inclined to implement appropriate proposals. The neurodiversity paradigm should be adopted, and terms such as “disability” should, over time, be replaced by more inclusive alternatives such as “difficulty” or “access limitation”. Following this philosophy, the latter terms were adopted in this review.

Some practical recommendations derived from this article, which emphasize the importance of applying UDL across all educational stages, ensuring a balanced implementation of the three UDL principles, identifying appropriate methodologies, and enhancing the inclusivity of laboratories, field experiences, and complex content, can be summarized in 10 key ideas presented in Figure 2. Teacher training programs should prioritize rigorous and detailed development of each of these identified components.

Figure 2.

Key ideas for science teachers to implement inclusive classes.

This review, however, presents several limitations that must be taken into account: first, a bias toward the English-language literature; second, the impossibility of fully covering the different dimensions examined; and third, an optimistic perspective regarding UDL application in science contexts due to the predominance of publications reporting successful experiences. As this was a narrative review, the conclusions relied primarily on conceptual and descriptive evidence rather than on measurable learning outcomes; however, future reviews should place greater emphasis on quantitative approaches.

Future lines of research point to the potential role of technology in supporting UDL and the need for specific assessment of designed proposals, appropriate dosage of UDL interventions, and the integration of UDL with specific methodologies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.F.-M. and G.J.-V.; methodology, N.F.-M.; validation, N.F.-M. and G.J.-V.; formal analysis, N.F.-M.; investigation, N.F.-M.; resources, N.F.-M. and G.J.-V.; data curation, N.F.-M.; writing—original draft preparation, N.F.-M.; writing—review and editing, N.F.-M. and G.J.-V.; visualization, N.F.-M. and G.J.-V.; supervision, N.F.-M. and G.J.-V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AAPT | American Association of Physics Teachers |

| ADHD | Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder |

| CAST | Center for Applied Special Technology |

| CL | Cooperative Learning |

| GBL | Game-Based Learning |

| IBSE | Inquiry-Based Science Education |

| NSTA | National Science Teachers Association |

| NoS | Nature of Science |

| OCD | Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder |

| PBL | Problem-Based Learning |

| SGT | Systemic Gamification Theory |

| STEAM | Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts, and Mathematics |

| STEM | Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics |

| STREAMING | Science, Technology, Robotics, Engineering, Artificial Intelligence, Mathematics, Emotional Intelligence, Inclusion, and Gamification |

| UDL | Universal Design for Learning |

| UDI | Universal Design for Instruction |

References

- CAST. Universal Design for Learning Guidelines Version 2.2. 2018. Available online: https://udlguidelines.cast.org/more/downloads/#v2-2 (accessed on 29 November 2025).

- Rose, D.H.; Meyer, A. Teaching Every Student in the Digital Age: Universal Design for Learning; ASCD: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- CAST. Universal Design for Learning Guidelines Version 2.0. 2011. Available online: https://udlguidelines.cast.org/more/downloads/#v2-0 (accessed on 29 November 2025).

- CAST. Universal Design for Learning Guidelines Version 3.0. 2024. Available online: https://udlguidelines.cast.org/more/downloads/#v3-0 (accessed on 29 November 2025).

- Schreffler, J.; Vasquez, E., III; Chini, J.; James, W. Universal Design for Learning in Postsecondary STEM Education for Students with Disabilities: A Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. STEM Educ. 2019, 6, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, R.; McNiff, A.; Schuck, R.; Imm, K.; Zimmerman, S. “UDL is a Way of Thinking”; Theorizing UDL Teacher Knowledge, Beliefs, and Practices. Front. Educ. 2023, 8, 1145293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, A.; Rose, D.H.; Gordon, D. Universal Design for Learning: Theory and Practice; CAST Professional Publishing: Wakefield, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Burgstahler, S. Universal Design of Instruction (UDI): Definition, Principles, Guidelines, and Examples. Disabilities, Opportunities, Internetworking, and Technology (DO-IT). Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED506547.pdf (accessed on 29 November 2025).

- Roski, M.; Walkowiak, M.; Nehring, A. Universal Design for Learning: The More, the Better? Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egara, F.; Mosia, M. Equipping Pre-service Mathematics Teachers for Diverse Classrooms: Best Practices and Innovations. Open Books Proc. 2025, 9, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education. Empowering Teachers to Promote Inclusive Education: Literature Review; European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education: Odense, Denmark, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Shafik, W. The Interplay Between Global Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and Inclusivity. In Global Sustainable Transition with Inclusion: A Focus on the People with Disabilities and the Marginalized; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2025; pp. 69–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, A.; Devitt, A.; Banks, J.; Sanchez Fuentes, S.; Sandoval, M.; Riviou, K.; Terrenzio, S. What Next for Universal Design for Learning? A Systematic Literature Review of Technology in UDL Implementations at Second Level. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2024, 55, 113–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrera, M.; Moliner, O. How Does Universal Design for Learning Help Me to Learn? Students with Autism Spectrum Disorder Voices in Higher Education. Stud. High. Educ. 2023, 49, 899–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creaven, A.M. Considering the Sensory and Social Needs of Disabled Students in Higher Education: A Call to Return to the Roots of Universal Design. Policy Futures Educ. 2024, 23, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewe, L.P.; Galvin, T. Universal Design for Learning Across Formal School Structures in Europe—A Systematic Review. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capp, M.J. Teacher Confidence to Implement the Principles, Guidelines, and Checkpoints of Universal Design for Learning. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2020, 24, 706–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flood, M.; Banks, J. Universal Design for Learning: Is it Gaining Momentum in Irish Education? Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King-Sears, M.E.; Stefanidis, A.; Evmenova, A.S.; Rao, K.; Mergen, R.L.; Owen, L.S.; Strimel, M.M. Achievement of Learners Receiving UDL Instruction: A Meta-analysis. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2023, 122, 103956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suprihatiningrum, J.; Ristiyanti, S.; Maulidina, F.; Wulayalin, K.A. Science Teachers’ Experiences to Ensure Science for All Movement: From Theory to Practice. Sci. Educ. Int. 2025, 36, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, A.M.; Ferreira, M.E.; da Silva Loureiro, M.J. Scientific Literacy: The Conceptual Framework Prevailing over the First Decade of the Twenty-First Century. Rev. Colomb. Educ. 2021, 81, 195–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turiman, P.; Omar, J.; Daud, A.M.; Osman, K. Fostering the 21st Century Skills through Scientific Literacy and Science Process Skills. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 59, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rappolt-Schlichtmann, G.; Daley, S.G.; Lim, S.; Lapinski, S.; Robinson, K.H.; Johnson, M. Universal Design for Learning and Elementary School Science: Exploring the Efficacy, Use, and Perceptions of a Web-Based Science Notebook. J. Educ. Psychol. 2013, 105, 1210–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pine, K.; Messer, D.; St. John, K. Children’s Misconceptions in Primary Science: A Survey of Teachers’ Views. Res. Sci. Technol. Educ. 2001, 19, 79–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, P.L.; Concannon, J.P. Students’ Perceptions of Vocabulary Knowledge and Learning in a Middle School Science Classroom. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2016, 38, 391–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemke, J.L. Talking Science: Language, Learning, and Values; Ablex Publishing Corporation: Norwood, NJ, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo, M.G.; Reverdito, A.M.; Blanco, M.; Salerno, A. Difficulties of Undergraduate Students in the Organic Chemistry Laboratory. Probl. Educ. 21st Century 2012, 42, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baurhoo, N.; Asghar, A. Using Universal Design for Learning to Construct Inclusive Science Classrooms for Diverse Learners. Learn. Landsc. 2014, 7, 59–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukhai, M.A.; Mohler, C.E. Creating a Culture of Accessibility in the Sciences; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, J.; Searles, S.; Holterman, L.A.; Simone, C.; Huggett, K. Universal Design for TBL®: Promoting Inclusion and Access for All Learners. Med. Sci. Educ. 2020, 30, 595–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comarú, M.W.; Lopes, R.M.; Braga, L.A.M.; Mota, F.B.; Galvão, C. A Bibliometric and Descriptive Analysis of Inclusive Education in Science Education. Stud. Sci. Educ. 2021, 57, 241–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meré-Cook, Y. Inclusive STEAM Education in Early Childhood: Strengths-Based Strategies for Supporting Children with Disabilities; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, Y.; Oliver, M.; Venville, G. Long-Term Outcomes of Early Childhood Science Education: Insights from a Cross-National Comparative Case Study on Conceptual Understanding of Science. Int. J. Sci. Math. Educ. 2012, 10, 1269–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clements, D.H.; Vinh, M.; Lim, C.I.; Sarama, J. STEM for Inclusive Excellence and Equity. In Developing Culturally and Developmentally Appropriate Early STEM Learning Experiences; Routledge: London, UK, 2023; pp. 148–171. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, D.; Dote-Kwan, J. Preschoolers with Visual Impairments and Additional Disabilities: Using Universal Design for Learning and Differentiation. Young Excep. Child. 2021, 24, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohmann, M.J.; Hovey, K.A.; Gauvreau, A.N. Universal Design for Learning (UDL) in Inclusive Preschool Science Classrooms. J. Sci. Educ. Stud. Disabil. 2023, 26, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guardino, C.; Hall, K.W.; Largo-Wight, E.; Hubbuch, C. Teacher and Student Perceptions of an Outdoor Classroom. J. Outdoor Environ. Educ. 2019, 22, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, A. Nature and the Outdoor Learning Environment: The Forgotten Resource in Early Childhood Education. Int. J. Early Child. Environ. Educ. 2015, 3, 85–97. [Google Scholar]

- Mirza, M.A.; Khurshid, K.; Hasan, A.; Shah, Z.; Shah, F. Correlating Universal Design of Learning and Performance in Science at the Elementary School Level. In Handbook on Intelligent Techniques in the Educational Process: Vol 1 Recent Advances and Case Studies; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 269–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, A.K.; Hansen, E.R.; Dwyer, H.A.; Harlow, D.B.; Franklin, D. Differentiating for Diversity: Using Universal Design for Learning in Elementary Computer Science Education. In Proceedings of the 47th ACM Technical Symposium on Computing Science Education, Memphis, TN, USA, 2–5 March 2016; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 376–381. [Google Scholar]

- Finnegan, L.A.; Dieker, L.A. Universal Design for Learning-Representation and Science Content: A Pathway to Expanding Knowledge, Understanding, and Written Explanations. Sci. Act. 2019, 56, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaunt, L.; Quane, K.; Trewartha, B.; Porta, T. Universal Design for Learning for Mathematics Education. In Proceedings of the 47th Annual Conference of the Mathematics Education Research Group of Australasia, Canberra, Australia, 6–10 July 2025; MERGA: Sydney, Australia, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Beames, S.; Christie, B.; Blackwell, I. Developing Whole School Approaches to Integrated Indoor/Outdoor Teaching. In Children Learning Outside the Classroom: From Birth to Eleven; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 82–93. [Google Scholar]

- Heugen, K. Bringing the Benefits of Nature to All Children. In The Active Learner, Highscope’s Journal for Early Educators; HighScope: Ypsilanti, MI, USA, 2019; pp. 12–13. Available online: https://highscope.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/HSActiveLearner_2019Spring_sample.pdf (accessed on 29 November 2025).

- Rao, K.; Ok, M.W.; Bryant, B.R. A Review of Research on Universal Design Educational Models. Remedial Spec. Educ. 2014, 35, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, T.; Prendergast, M. Students’ Perceptions of Mathematics Writing and Its Impact on Their Enjoyment and Self-Confidence. Teach. Math. Its Appl. 2022, 41, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Street, C.D.; Koff, R.; Fields, H.; Kuehne, L.; Handlin, L.; Getty, M.; Parker, D.R. Expanding Access to STEM for At-Risk Learners: A New Application of Universal Design for Instruction. J. Postsecond. Educ. Disabil. 2012, 25, 363–375. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner, M.E. Faculty Willingness to Provide Accommodations and Course Alternatives to Postsecondary Students with Learning Disabilities. Int. J. Spec. Educ. 2007, 22, 32–45. [Google Scholar]

- Cawley, J.F. Science for Students with Disabilities. Remedial Spec. Educ. 1994, 15, 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyce, J.; Harrison, J.R.; Gitomer, D.H. Modifications and Accommodations: A Preliminary Investigation into Changes in Classroom Artifact Quality. Int. J. Inclus. Educ. 2020, 24, 181–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cretu, D.M.; Morandau, F. Initial Teacher Education for Inclusive Education: A Bibliometric Analysis of Educational Research. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottfried, M.A.; Hutt, E.L.; Kirksey, J.J. New Teachers’ Perceptions on Being Prepared to Teach Students with Learning Disabilities: Insights from California. J. Learn. Disabil. 2019, 52, 383–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narot, P.K.; Srisuruk, P. Pre-service Curriculum and Perception of Prospective Student Teachers towards Inclusive Education. In Handbook of Research on Teacher Education: Innovations and Practices in Asia; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2022; pp. 721–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriña, A.; Carballo, R.; Doménech, A. Transforming Higher Education: A Systematic Review of Faculty Training in UDL and Its Benefits. Teach. High. Educ. 2025, 1, 1722–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabre-Mitjans, N.; Jiménez-Valverde, G.; Guimerà-Ballesta, G.; Calafell-Subirà, G. Digital Gamification to Foster Attitudes Toward Science in Early Childhood Teacher Education. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 5961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Valverde, G.; Heras-Paniagua, C.; Fabre-Mitjans, N.; Calafell-Subirà, G. Gamifying Teacher Education with FantasyClass: Effects on Attitudes Towards Physics and Chemistry Among Preservice Primary Teachers. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamora-Polo, F.; Corrales-Serrano, M.; Sánchez-Martín, J.; Espejo-Antúnez, L. Nonscientific University Students Training in General Science Using an Active-Learning Merged Pedagogy: Gamification in a Flipped Classroom. Educ. Sci. 2019, 9, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Research Council (NRC). Inquiry and the National Science Education Standards: A Guide for Teaching and Learning; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Tsaliki, C.; Papadopoulou, P.; Malandrakis, G.; Kariotoglou, P. Evaluating Inquiry Practices: Can a Professional Development Program Reform Science Teachers’ Practices? J. Sci. Teach. Educ. 2022, 33, 815–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, A.L.; Ong, Y.S.; Ng, Y.S.; Tan, J.H.J. STEM Problem Solving: Inquiry, Concepts, and Reasoning. Sci. Educ. 2023, 32, 381–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sofianidis, A.; Skraparlis, C.; Stylianidou, N. Combining Inquiry, Universal Design for Learning, Alternate Reality Games, and Augmented Reality Technologies in Science Education: The IB-ARGI Approach and the Case of Magnetman. J. Sci. Educ. Technol. 2024, 33, 928–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Research Council (NRC). National Science Education Standards; National Academy Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Klahr, D.; Nigam, M. The Equivalence of Learning Paths in Early Science Instruction: Effects of Direct Instruction and Discovery Learning. Psychol. Sci. 2004, 15, 661–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Therrien, W.J.; Taylor, J.C.; Hosp, J.L.; Kaldenberg, E.R.; Gorsh, J. Science Instruction for Students with Learning Disabilities: A Meta-Analysis. Learn. Disabil. Res. Pract. 2011, 26, 188–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scruggs, T.E.; Mastropieri, M.A.; Boon, R. Science Education for Students with Disabilities: A Review of Recent Research. Stud. Sci. Educ. 1998, 32, 21–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watt, S.J.; Therrien, W.J.; Kaldenberg, E.; Taylor, J. Promoting Inclusive Practices in Inquiry-Based Science Classrooms. Teach. Except. Child. 2013, 45, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Therrien, W.J.; Taylor, J.C.; Watt, S.; Kaldenberg, E.R. Science Instruction for Students with Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. Remedial Spec. Educ. 2014, 35, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toma, R.B. Confirmation and Structured Inquiry Teaching: Does it Improve Students’ Achievement Motivations in School Science? Can. J. Sci. Math. Technol. Educ. 2022, 22, 28–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebti, L.; Damiani, M.L. Engaging Students with Disabilities in Universally Designed Science Education. J. Sci. Educ. Stud. Disabil. 2021, 24, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambitious Science Teaching Development Group. Tools for Ambitious Science Teaching. Available online: https://ambitiousscienceteaching.org/resource-type/type-tool/ (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Koebley, S.; Wakeman, S.; Ruhter, L.; Pugalee, D.; Karvonen, M. Making Science-Inquiry Learning Accessible for Students with Complex Support Needs. J. Sci. Educ. Stud. Disabil. 2024, 27, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Garderen, D.; Decker, M.; Juergensen, R.; Abdelnaby, H. Using the 5E Instructional Model in an Online Environment with Pre-service Special Education Teachers. J. Sci. Educ. Stud. Disabil. 2020, 23, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanuscin, D.; Van Garderen, D. Universal Design for Learning Science: Reframing Elementary Instruction in Physical Science; NSTA Press: Arlington, VA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Israel, M.; Shehab, S. Increasing Science Learning and Engagement for Academically Diverse Students through Scaffolded Scientific Inquiry and Universal Design for Learning. In Towards Inclusion of All Learners through Science Teacher Education; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 201–211. [Google Scholar]

- Bonwell, C.C.; Eison, J.A. Active Learning: Creating Excitement in the Classroom; School of Education and Human Development, George Washington University: Washington, DC, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Doolittle, P.; Wojdak, K.; Walters, A. Defining Active Learning: A Restricted Systematic Review. Teach. Learn. Inq. 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Land, M.H. Full STEAM Ahead: The Benefits of Integrating the Arts into STEM. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2013, 20, 547–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoma, R.; Farassopoulos, N.; Lousta, C. Teaching STEAM through Universal Design for Learning in Early Years of Primary Education: Plugged-in and Unplugged Activities with Emphasis on Connectivism Learning Theory. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2023, 132, 104210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catterall, L.G. A Brief History of STEM and STEAM from an Inadvertent Insider. STEAM J. 2017, 3, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyotte, K.W.; Sochacka, N.W.; Costantino, T.E.; Kellam, N.N.; Walther, J. Collaborative Creativity in STEAM: Narratives of Art Education Students’ Experiences in Transdisciplinary Spaces. Int. J. Educ. Arts 2015, 16, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Segarra, V.A.; Natalizio, B.; Falkenberg, C.V.; Pulford, S.; Holmes, R.M. STEAM: Using the Arts to Train Well-Rounded and Creative Scientists. J. Microbiol. Biol. Educ. 2018, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, W.L.; Samsudin, M.A.; Ismail, M.E.; Ahmad, N.J. Gender Differences in Students’ Achievements in Learning Concepts of Electricity via STEAM Integrated Approach Utilizing Scratch. Probl. Educ. 21st Century 2020, 78, 423–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, M.T. Defining a Technology Research Agenda for Elementary and Secondary Students with Learning and Other High Incidence Disabilities in Inclusive Science Classrooms. J. Spec. Educ. Technol. 2010, 25, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCleery, J.A.; Tindal, G.A. Teaching the Scientific Method to At-Risk Students and Students with Learning Disabilities through Concept Anchoring and Explicit Instruction. Remedial Spec. Educ. 1999, 20, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, S.; Taymans, J.; Watson, A.W.; Ochsendorf, R.J.; Pyke, C.; Szesze, M.J. Effectiveness of a Highly Rated Science Curriculum Unit for Students with Disabilities in General Education Classrooms. Except. Child. 2007, 73, 202–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basham, J.D.; Marino, M.T. Understanding STEM Education and Supporting Students Through Universal Design for Learning. Teach. Except. Child. 2013, 45, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasri, N.; Rahimi, N.M.; Nasri, N.M.; Talib, M.A.A. A Comparison Study Between Universal Design for Learning-Multiple Intelligence (UDL-MI) Oriented STEM Program and Traditional STEM Program for Inclusive Education. Sustainability 2021, 13, 554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, M.; Fryer, C. A Collaborative Initiative: STEM and Universally Designed Curriculum for At-Risk Preschoolers. Natl. Teach. Educ. J. 2014, 7, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Gilleran Stephens, C.; Antwi, S.H.; Linnane, S. Universal Design for Learning (UDL): A Framework for Re-Design of an Environmental Education (EE) Outreach Program for a More Inclusive and Impactful Science Festival Event. Discov. Educ. 2025, 4, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvarajan, L.; Kamarudin, N.; Mustakim, S.S. Bridging the Gap: How Universal Design for Learning Can Transform Biology Education: A Systematic Review. IIUM J. Educ. Stud. 2025, 13, 3–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jesionkowska, J.; Wild, F.; Deval, Y. Active Learning Augmented Reality for STEAM Education—A Case Study. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, N.W.; Todd, R.L.; Morton, D.L.; Ivey, E. Accommodating Students with Disabilities in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM); Center for Assistive Technology and Environmental Access, Georgia Institute of Technology: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2012; Volume 8, p. 21. [Google Scholar]

- Drigas, A.; Kefalis, C. STREAMING: A Comprehensive Approach to Inclusive STEM Education. Sci. Electron. Arch. 2024, 17, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AccessSTEM. Disability Type. Available online: https://doit.uw.edu/programs/accessstem/ (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Otegui, X.; Raimondi, C. Enhancing Pedagogical Practices in Engineering Education: Evaluation of a Training Course on Active Learning Methodologies. In Towards a Hybrid, Flexible and Socially Engaged Higher Education; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torralba, K.D.; Doo, L. Active Learning Strategies to Improve Progression from Knowledge to Action. Rheumatol. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 2020, 46, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapp, K.M. The Gamification of Learning and Instruction: Game-Based Methods and Strategies for Training and Education; Pfeiffer: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez, E. Game-Based Learning. In Encyclopedia of Education and Information Technologies; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kalogiannakis, M.; Papadakis, S.; Zourmpakis, A.I. Gamification in Science Education: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintero, J.; Baldiris, S.; Cerón, J.; Garzón, J.; Burgos, D.; Vélez, G. Gamification as Support for Educational Inclusion: The Case of AR-mBot. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Advanced Learning Technologies (ICALT), Bucharest, Romania, 1–4 July 2022; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 269–273. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, J.; Taub, M.; Marino, M.; Duarte, A.; Bentley, B.; Holman, K.; Banzon, A. Enhancing Engagement and Fraction Concept Knowledge with a Universally Designed Game-Based Curriculum. Learn. Disabil. Contemp. J. 2022, 20, 77–95. [Google Scholar]

- Coelho, F.; Abreu, A.M. Systemic Gamification Theory (SGT): A Holistic Model for Inclusive Gamified Digital Learning. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2025, 9, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Valverde, G.; Fabre-Mitjans, N.; Heras-Paniagua, C.; Guimerà-Ballesta, G. Tailoring Gamification in a Science Course to Enhance Intrinsic Motivation in Preservice Primary Teachers. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altun, S. The Effect of Cooperative Learning on Students’ Achievement and Views on the Science and Technology Course. Int. Electron. J. Elem. Educ. 2015, 7, 451–467. [Google Scholar]

- Aparicio-Ting, F.; Kurz, E. I Get by with a Little Help from My Friends: Applying UDL to Group Projects. In Incorporating Universal Design for Learning in Disciplinary Contexts in Higher Education; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 52–63. [Google Scholar]

- Terson de Paleville, D. Flipped Team-Based Learning as Universal Design for Learning Physiology. Physiology 2024, 39, S948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curry, C.; Cohen, L.; Lightbody, N. Universal Design in Science Learning. Sci. Teach. 2006, 73, 32–37. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery, T.D.; Green, B.M.; Oliech, C.G.; Evanseck, J.D. Learning from a Pandemic: Redesigning with Universal Design for Learning to Enhance Scientific Skills (Practice Brief). J. Postsecond. Educ. Disabil. 2024, 37, 73–79. [Google Scholar]

- Orndorf, H.C.; Waterman, M.; Lange, D.; Kavin, D.; Johnston, S.C.; Jenkins, K.P. Opening the Pathway: An Example of Universal Design for Learning as a Guide to Inclusive Teaching Practices. CBE—Life Sci. Educ. 2022, 21, ar28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepore, T.; Lu, J.; Starowicz, R.; Hlusko, L.J. Student Perception of Accessibility and Disability in College Evolutionary Biology Courses: A Qualitative Study Using Reflexive Thematic Analysis. Int. J. Inclus. Educ. 2025, 1, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojdak, K.; Smith, M.K.; Orndorf, H.; Ramirez, M.L. Evaluating Universal Design for Learning and Active Learning Strategies in Biology Open Educational Resources (OERs). Teach. Learn. Inq. 2024, 12, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casebolt, T.; Humphrey, K. Use of Universal Design for Learning Principles in a Public Health Course. Ann. Glob. Health 2023, 89, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dempsey, A.M.; Nolan, Y.M.; Lone, M.; Hunt, E. Examining Motivation of First-Year Undergraduate Anatomy Students through the Lens of Universal Design for Learning (UDL): A Single Institution Study. Med. Sci. Educ. 2023, 33, 945–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryans Bongey, S.; Cizadlo, G.; Kalnbach, L. Blended Solutions: Using a Supplemental Online Course Site to Deliver Universal Design for Learning (UDL). Campus-Wide Inf. Syst. 2010, 27, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehner, E. Cogenerative Dialogue: Developing Biology Learning Accommodations for Students with Disabilities. World J. Educ. Res. 2016, 3, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scanlon, E.; Schreffler, J.; James, W.; Vasquez, E.; Chini, J.J. Postsecondary Physics Curricula and Universal Design for Learning: Planning for Diverse Learners. Phys. Rev. Phys. Educ. Res. 2018, 14, 020101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stonehouse, C. Access for All: A Guide to Disability Good Practice for University Physics Departments. Inst. Phys. Guide 2008, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Dounas-Frazer, D.R.; Gillen, D.; Herne, C.M.; Howard, E.; Lindell, R.S.; McGrew, G.I.; Mumford, J.R.; Nguyen, N.H.; Osadchuk, L.C.; Crane, J.P.; et al. Increase Investment in Accessible Physics Labs: A Call to Action for the Physics Education Community. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2202.00816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lannan, A.; Chini, J.J.; Scanlon, E. Resources for Supporting Students with and without Disabilities in Your Physics Courses. Phys. Teach. 2021, 59, 192–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chini, J.J.; Scanlon, E.M. Teaching Physics with Disabled Learners: A Review of the Literature. In International Handbook of Physics Education Research; AIP Publishing: Melville, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustamante, C.; Chini, J.J.; Scanlon, E. Supporting Students with ADHD in Introductory Physics Courses: Four Steps for Instructors. Phys. Teach. 2021, 59, 573–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atika, I.N.; Buana, S.H.A.; Yusrika, A.Z. Development of a STEM-Based Physics Instructional Tool to Encourage Students’ Collaboration Skills in Inclusive High School. J. Penelit. Pendidik. IPA 2025, 11, 917–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrón-Hernández, A.R.; Ramírez-Díaz, M.H. Universal Learning Design in Physics Teaching: An Application Proposal. Rev. Científica 2023, 47, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurramadhani, A.Z.; Pratama, K.P.S.; Amelia, L.; Kusuma, A.; Erika, F. Literature Review: Universal Design for Learning (UDL) Approach of Chemistry Learning in Inclusion Schools. Hydrog. J. Kependidik. Kim. 2024, 12, 1324–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King-Sears, M.E.; Johnson, T.M. Universal Design for Learning Chemistry Instruction for Students with and without Learning Disabilities. Remedial Spec. Educ. 2020, 41, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosmi, Y.F.; Jauhari, M.N. Universal Design for Learning pada Pembelajaran Pendidikan Jasmani Adaptif di Sekolah Inklusi. STAND J. Sports Teach. Dev. 2022, 3, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, R.; Choden, K.; Lhapchu, L.; Rinchen, S. Integrating Universal Design for Learning Principles in Chemistry Education. J. Res. Educ. Pedagog. 2025, 2, 464–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann, T.; Melle, I. Evaluation of a Digital UDL-Based Learning Environment in Inclusive Chemistry Education. Chem. Teach. Int. 2019, 1, 20180026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, C.T.; Lawrie, G.A.; Thompson, C.D.; Kyne, S.H. “Every Little Thing That Could Possibly Be Provided Helps”: Analysis of Online First-Year Chemistry Resources Using the Universal Design for Learning Framework. Chem. Educ. Res. Pract. 2022, 23, 385–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.K.; Lang, P.L. Using the Universal Design for Learning Approach in Science Laboratories to Minimize Student Stress. J. Chem. Educ. 2016, 93, 1823–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, A.K.; Maxwell, A.E. Universal Design for Learning in the Geosciences for Access and Equity in Our Classrooms. J. Appl. Instr. Des. 2021, 10, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carabajal, I.G.; Marshall, A.M.; Atchison, C.L. A Synthesis of Instructional Strategies in Geoscience Education Literature that Address Barriers to Inclusion for Students with Disabilities. J. Geosci. Educ. 2017, 65, 531–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giles, S.; Jackson, C.; Stephen, N. Barriers to Fieldwork in Undergraduate Geoscience Degrees. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2020, 1, 77–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feig, A.D.; Atchison, C.; Stokes, A.; Gilley, B. Achieving Inclusive Field-Based Education: Results and Recommendations from an Accessible Geoscience Field Trip. J. Sch. Teach. Learn. 2019, 19, 66–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokes, A.; Feig, A.D.; Atchison, C.L.; Gilley, B. Making Geoscience Fieldwork Inclusive and Accessible for Students with Disabilities. Geosphere 2019, 15, 1809–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Frank, A.; Fesharaki, O.; Iglesias-Álvarez, N. Tasting of Mineral Salts: An Inclusive Proposal for the Teaching of Geology. In INTED2021 Proceedings, Proceedings of the 15th International Technology, Education and Development Conference, Online, 8–9 March 2021; IATED: Valencia, Spain, 2021; pp. 3080–3087. [Google Scholar]

- Ríos-Reyes, C.A.; Portilla-Mendoza, K.A.; Carrillo-Hernández, Y.M.; Díaz-Gutiérrez, S.L.; Gutiérrez-Quintero, N.S.; Castellanos-Alarcón, O.M.; López-Alba, M. Inclusive Teaching of Palaeontology for People with and without Disabilities through Didactic Workshops. Int. J. Inclus. Educ. 2024, 29, 2358–2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, O.; Buckley, K.; Lieberman, L.J.; Arndt, K. Universal Design for Learning-A Framework for Inclusion in Outdoor Learning. J. Outdoor Environ. Educ. 2022, 25, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillenschneider, C. Integrating Persons with Impairments and Disabilities into Standard Outdoor Adventure Education Programs. J. Exp. Educ. 2007, 30, 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar, O.M.; McCann, E.P.; Liddicoat, K. Inclusive Education. In Urban Environmental Education Review; Comstock Publishing Associates: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Espinoza-Ramos, G.R. Making Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) More Inclusive and Engaging through Universal Design for Learning (UDL): A Case Study at the Westminster Business School. In An Agenda for Sustainable Development Research; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 651–669. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, C.; Smith, G.; Broderick, N. A Starting Point: Provide Children Opportunities to Engage with Scientific Inquiry and Nature of Science. Res. Sci. Educ. 2021, 51, 1759–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manassero-Mas, M.A.; Vázquez-Alonso, Á. Enseñar y Aprender a Pensar sobre la Naturaleza de la Ciencia: Un Juego de Cartas como Recurso en Educación Primaria. Rev. Eureka Enseñ. Divulg. Cienc. 2023, 20, 220201–220219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Valverde, G.; Fabre-Mitjans, N.; Guimerà-Ballesta, G. Games and Playful Activities to Learn About the Nature of Science. Encyclopedia 2025, 5, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsayed, R.; Daehler, K.; Clark, J.G.; Bloom, N.E. Promoting Inclusion and Engagement in STEM: A Practical Guide for Out-of-School-Time Professionals; WestEd: San Francisco, CA, USA; Northern Arizona University: Flagstaff, AZ, USA, 2022; Available online: https://planets-stem.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/A-Practical-Guide-082922-centered.pdf (accessed on 29 November 2025).

- Panzera-Gonçalves, J.; Marcolan Valverde, T.; Segatelli, T.M.; Oliveira, C.A. Teaching Cell Biology to a Student Who is Blind: Promoting Inclusion and Teacher Training in Higher Education. Int. J. Inclus. Educ. 2025, 1, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magaña-Cruz, E.; Vera, L.G.; Arguijo, J.A.; Peña, A.T.; Flores, L.G.; Reynaga-Peña, C.G. Engineering for UDL-Based Education: Translating Book Images into Interactive 3D Educational Materials for Health Sciences Subjects. Tecnol. Educ. Rev. CONAIC 2024, 11, 76–82. [Google Scholar]

- Hasley, A.O.; Jenkins, K.P.; Orndorf, H.; Gibson, J.P. Tactile Trees: Demystifying Phylogenies for Everyone with Universal Design for Learning. Am. Biol. Teach. 2024, 86, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toggerson, B.K. In Service of Equity: 3D-Printed Models in University Introductory Physics. Phys. Teach. 2022, 60, 565–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos Aguiar, L.R.; Álvarez Rodríguez, F.J.; Madero Aguilar, J.R.; Navarro Plascencia, V.; Peña Mendoza, L.M.; Quintero Valdez, J.R.; Vázquez, J.R.; Mendieta, A.; Lazcano Ortiz, L.E. Implementing Gamification for Blind and Autistic People with Tangible Interfaces, Extended Reality, and Universal Design for Learning: Two Case Studies. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 3159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouroupetroglou, G.; Kacorri, H. Deriving Accessible Science Books for the Blind Students of Physics. In Proceedings of the AIP Conference, Alexandroupolis, Greece, 9–13 September 2009; American Institute of Physics: Melville, NY, USA, 2010; Volume 1203, pp. 1308–1313. [Google Scholar]

- Wulayalin, K.A.; Suprihatiningrum, J. Creating Accessible Chemistry Content for Students with Disabilities: Findings from Schools Providing Inclusive Education in Indonesia. J. Penelit. Pendidik. IPA 2024, 10, 2199–2210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, P. The Neurodiversity Approach (es): What Are They and What Do They Mean for Researchers? Hum. Dev. 2022, 66, 73–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, R. Empire of Normality: Neurodiversity and Capitalism; Pluto Press: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Botha, M.; Chapman, R.; Giwa Onaiwu, M.; Kapp, S.K.; Stannard Ashley, A.; Walker, N. The Neurodiversity Concept Was Developed Collectively: An Overdue Correction on the Origins of Neurodiversity Theory. Autism 2024, 28, 1591–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kryukova, N.I.; Rastorgueva, N.E.; Popova, E.O.; Zakharova, V.L.; Aytuganova, J.I.; Bikbulatova, G.I. Examining the Implementations Related to Teaching Science to Students with Disabilities. Eurasia J. Math. Sci. Technol. Educ. 2023, 19, em2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, W.B.; Yu, J.; Wei, X.; Vidiksis, R.; Patten, K.K.; Riccio, A. Promoting Science, Technology, and Engineering Self-Efficacy and Knowledge for All with an Autism Inclusion Maker Program. Front. Educ. 2020, 5, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moody, A.K.; Kubasko, D.S.; Walker, A.R. Strategies for Supporting Students Diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorders in STEM Education. J. Am. Acad. Spec. Educ. Prof. 2018, 44, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hite, R.; Childers, G.; Jones, G.; Corin, E.; Pereyra, M. Describing the Experiences of Students with ADHD Learning Science Content with Emerging Technologies. J. Sci. Educ. Stud. Disabil. 2021, 24, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leininger, M.; Taylor Dyches, T.; Prater, M.A.; Heath, M.A. Teaching Students with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Intervent. Sch. Clin. 2010, 45, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, M.; Downey, D. Teaching Strategies for Third-Level Science Students with Dyslexia and/or Dyspraxia. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Engaging Pedagogy 2010 (ICEP10), Dublin, Ireland, 2 September2010. [Google Scholar]

- Nwikpo, M.N.; Chiemeka, P.C. Leveraging Digital Manipulatives in Remediation of Dyscalculia: A Theoretical Framework. Unizik Orient J. Educ. 2024, 12, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Boyle, S.; Rizzo, K.L.; Taylor, J.C. Reducing Language Barriers in Science for Students with Special Educational Needs. Asia-Pac. Sci. Educ. 2020, 6, 364–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wusqo, I.U.; Pamelasari, S.D.; Khusniati, M.; Yanitama, A.; Pratidina, F.R. The Development and Validation of Science Digital Scrapbook in a Universal Design for Learning Environment. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 1918, 052090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milakis, E.D. Collaborative Project-Based Learning as a Pedagogical Strategy for Inclusion in Gifted STEAM Education: Teachers’ Perspectives from Mixed-Ability Classrooms. Int. J. Multidiscip. Trends 2025, 7, 92–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, E.A. Gender Identity, Sexuality and Autism: Voices from Across the Spectrum; Jessica Kingsley Publishers: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Dowey, N.; Barclay, J.; Fernando, B.; Giles, S.; Houghton, J.; Jackson, C.; Khatwa, A.; Lawrence, A.; Mills, K.; Newton, A.; et al. A UK Perspective on Tackling the Geoscience Racial Diversity Crisis in the Global North. Nat. Geosci. 2021, 14, 256–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, C.M.; Aronson, J. Stereotype Threat and the Intellectual Test Performance of African Americans. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 69, 797–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heron, P.J.; Crameri, F.; Canaletti, E.F.; Harrison, D.; Hashemi, S.; Leigh, P.; Narayan, S.; Osowski, K.; Rantanen, R.; Williams, J.A. Art, Music, and Play as a Teaching Aid: Applying Creative Uses of Universal Design for Learning in a Prison Science Class. Front. Educ. 2025, 10, 1524007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowther, G.J.; Adjapong, E.; Jenkins, L.D. Teaching Science with the “Universal Language” of Music: Alignment with the Universal Design for Learning Framework. Adv. Physiol. Educ. 2023, 47, 491–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaladanki, V.S.; Bhattacharya, K. Interactive Notebook Arts-Based Approach to Physics Instruction. Creat. Approaches Res. 2015, 8, 2. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.