Definition

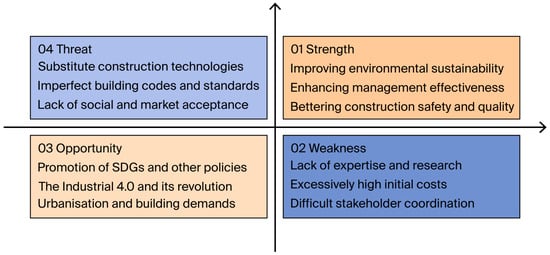

Modular construction is generally defined as a typical offsite construction approach that can improve environmental sustainability throughout the building project lifecycle. Based on this situation, identifying the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats (SWOT) while promoting this sustainable construction method effectively during the urbanisation process is essential. Generally, modular construction is a sustainable building approach that can improve project sustainability, considering the environmental, social, economic, and technological aspects. A comprehensive understanding of the basic situation of prefabricated construction is worthwhile to ensure the widespread adoption of this offsite building method. By employing the SWOT analytical framework, this study adopts a literature review approach to conduct the investigation. In terms of the project results, the core strengths of using modular construction include improving environmental sustainability, enhancing management effectiveness, and improving construction safety and quality. The major weaknesses, on the other hand, are a lack of expertise and research, excessively high initial costs, and difficulties in stakeholder coordination. On the other hand, the major opportunities include promoting the SDGs and other policies, the Industrial Revolution 4.0, and urbanisation and building demands. The main threats, however, include substitute construction technologies, imperfect building codes and standards, and a lack of social and market acceptance. Further research can increase the sample size and collect more accurate firsthand data to validate the results of the current investigation, which can increase the effectiveness of promoting modular construction in the targeted regions.

1. Introduction

This article illustrates the modular construction concept and introduces the prefabricated building project building process. By analysing the comprehensive environment of this sustainable building approach, the SWOT analytical tool is chosen to discuss the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats of adopting prefabricated construction across the industry [1]. Additionally, in the project management discipline, construction is generally defined as a project, and exploring what comprises a successful modular building project is important. Under the project concept, studying modular construction using the project management body of knowledge is reasonable because the proposed research relies on transdisciplinary collaboration and cross-industrial cooperation. Considering the hot topic of the SWOT analysis, the comprehensive literature review in this paper consolidates the relevant literature analysis to ensure the innovation of research fundamentals.

2. Overview of Modular Construction

The global construction sector is witnessing a significant increase in implementing prefabricated technology in construction projects. This environmentally friendly approach, originating in London, was embraced in domestic design in the 19th century [2]. In the last ten years, prefabrication has increasingly replaced cast-in-place construction as a dominant building method, particularly in industrialised nations. Some building projects are constructed through this offsite approach, and most construction projects are completed by combining modular building technology and the traditional cast-in-place method [3]. Notably, more and more building projects are using this green construction technology during the development of regional urbanisation. According to the definitions from academic publications, prefabrication often entails manufacturing modules and panels in industrial environments and transporting them to the building site [4]. The finished building components are then methodically integrated into the subsequent construction phase to create the building structure [5]. In other words, prefabrication can be seen as a typical offsite construction technique that can reduce the construction time and on-site building tasks. The assigned factory assembly lines produce building elements during pre-construction, which are transported to the construction site for assembly after in-factory manufacturing. On-site construction generally focuses on the safety of construction works (e.g., the structural connection and hoisting of fabricated components) and the effective assembly of required building components [6]. Although the delivery of many building products still heavily relies on the adoption of the conventional cast-in-place approach, fortunately, many building professionals have already noticed the advantages and importance of using modular construction and encouraged its wide promotion, especially for underdeveloped regions requiring a large amount of building and infrastructure construction [7].

The widespread professional viewpoint is that prefabricated construction is generally grouped into three major types, including the single-element (1D), panelised scenario (2D), and volumetric (3D) types, and modular construction commonly refers to the scenario of 2D and 3D types in the construction industry [8]. Within the context of this article, the terms “prefabricated”, “modular”, and “offsite” are utilised synonymously without any discernible effect on the substance of the written material, which is the same as the written content in other formal academic publications [9]. Modular construction is, theoretically, an offsite building method, as delineated in the specialised terminology. Some scholars performed a comprehensive analysis of the essential procedures in modular housing assembly, starting with the transportation stage and culminating in the final delivery [3]. The process of prefabricated structures is typically recognised to encompass five steps. The procedure includes design and conceptualisation, procurement and storage of construction materials, manufacture of prefabricated components, transportation to the construction site, and final assembly of the structure. Previous studies indicate that key prefabricated components and standard panels are produced, assessed, and chosen during the planning phase [10]. After the fabrication of panels at industrial sites and their transportation to the designated place, the following phase involves erecting the requisite structures. During the pre-construction phase, manufacturers are mostly responsible for producing standard panels and the requisite manufactured components, which are completed before the official construction stage [11]. Afterwards, the previously described components are manufactured offsite and transported to the designated location for final assembly. Modular construction relies heavily on prefabrication and assembly, as the quality attained at this stage can directly influence the project results evaluated by internal stakeholders. The construction of buildings using modular components is akin to assembling Lego bricks, and this sustainable building approach is widely adopted by many wealthy nations and increasingly recommended for developing nations [3].

3. A SWOT Analysis of Modular Construction

A thorough examination of the macroenvironment of modular construction is essential under the present research circumstances. The SWOT analysis has four fundamental components: opportunities, threats, strengths, and weaknesses [9]. The strengths and weaknesses emphasise the competitiveness of the target, taking into account its internal conditions. The opportunities and risks underscore the necessity to examine external aspects that may influence the analytical aim either favourably or adversely [1]. Considering prior research in the construction sector, an assessment of the interior and exterior environments of modular buildings is performed utilising this tool, emphasising the evaluation of the strengths and drawbacks of this construction methodology. A study of the credible literature presents a SWOT analysis of prefabrication in building projects, as depicted in Figure 1 [3,7]. The supporting evidence is derived from the analysed publications (including dozens of reliable journal articles, conference papers, book chapters and case studies), which must be formally published in esteemed academic issues and possess adequate citations. The selected academic publications should be peer-reviewed and indexed by convincing databases, such as the Google Scholars, Scopus and other reliable sources. Given the comprehensiveness of reviewing previous research outputs, this paper investigates the research topic from the global range. The analysis of both external and internal contexts concerning the adoption of modular structures assesses the advantages and disadvantages of prefabrication in building projects, categorised into strengths (internal), weaknesses (internal), opportunities (external), and dangers (external). The strengths of using modular constructions are summarised as improvements in environmental sustainability, management effectiveness, and construction safety and quality. On the other hand, there are several areas for improvement (weaknesses) in using this offsite building technology, including but not limited to the lack of expertise and research, excessively high initial costs, and difficult stakeholder coordination. Considering the external macroenvironment and promotion of the UN (United Nations)’s SDGs (sustainable development goals) and other supportive policies on modular construction, the Industrial Revolution 4.0 period, and the global urbanisation process with its significant building demands can be seen as the major opportunities for adopting prefabricated construction. Moreover, the substitute building technologies (e.g., the traditional cast-in-place construction method and the 3D printing building techniques), imperfect building codes and standards, and lack of social and market acceptance can threaten the effective promotion of initiating and developing modular building projects [3,7,9].

Figure 1.

A basic SWOT analysis of adopting the modular construction approach (Data from [3,9]). Red colors mean positive factors, and blue colors indicate negative elements.

3.1. Strengths of Modular Constructions

In terms of the strengths of modular construction, Figure 1 lists three major internal advantages of employing this advanced building approach, which can improve environmental sustainability, management effectiveness, and construction safety and quality. Compared with the traditional cast-in-place building approach, the modular construction project can significantly improve its practical environmental sustainability performance, especially for the formal on-site construction phase [12]. First, the prefabricated mode of building components can control raw material use and reduce construction waste if the modular elements are manufactured in factories strictly complying with the standardised component production requirements. For instance, Cao et al. compared the cast-in-place and prefabricated building approaches and identified clear reductions in the total consumption of building materials [5]. The material consumption of mortar and timber was reduced by over 70%, and water consumption also decreased by approximately 25% [4,5]. In this case, construction waste, which is commonly generated from building materials, can decrease by at least 20% depending on the specific type of building waste [5]. The upper minimisation range can reach approximately 80% compared to the conventional building approach [13].

Additionally, the modular building project also performs well regarding saving energy [14]. Compared with the traditional erection method, the electricity consumption of the prefabricated building is effectively reduced by approximately 75% while undertaking external decoration work. Similar improvements also occur during transportation (saving more than 50%) and template work (saving approximately 30%), and this offsite building approach can positively control the energy wasted in reinforcement building tasks [5]. The total electricity consumption of the analysed prefabricated building is minimised by more than 40% compared with the cast-in-place construction method [5,9]. This case study also collects and analyses the negative effects of the sample building projects. The resource depletion of prefabricated building samples is reduced by approximately 35% compared to the traditional on-site construction method. Moreover, its negative influences on the stakeholder’s health and ecosystem are lowered by 6% and 3%, respectively [3,5]. Another case study conducted by the research group of Wang et al. also confirms the positive effects of using prefabricated building technology on the project’s environmental performance [15]. For example, the energy use and carbon emissions of using prefabricated public buildings (PPBs) during each project lifecycle stage are less than those of traditional public buildings (TPBs). Based on the strict review of these statistics in this case, the modular construction approach can clearly improve the environmental sustainability of building projects, and this viewpoint is also supported by many other reputable scholars and corresponding research [3,13,14,16].

Another strength of modular construction is related to improving the building project management effectiveness, particularly for reducing the construction period and improving schedule management, cost efficiency from the long-term development insight, labour force and intensity control, and other management-related aspects. Firstly, modular construction can shorten the practical building period, which is one of the major factors motivating European countries to apply this offsite technique to develop construction projects [12]. Many investigations show that the construction period of modular building projects can be reduced by approximately 50% compared to the traditional method [8]. For instance, the La Trobe Tower, one of Australia’s highest buildings (over 130 metres), was completed within weeks using the modular construction approach [16]. The construction group adopts the Hickory Building System (HBS, a newly innovative modular building form), integrating more functional components into the prefabricated structures [17]. The adoption of a modular construction approach can effectively control and significantly reduce on-site construction tasks, ranging from 80% to 90% (these replaced activities occur in the prefabricated factories during the pre-construction stage), which can reduce the on-site construction time correspondingly [12]. Thus, the practical delivery date of this noticeable construction is approximately eight months earlier than the traditional cast-in-place method, which decreases more than 30% of the total building time [16,17]. Reducing on-site construction tasks can also lower the demand for many building workforces, modify labour intensity control, and reduce on-site uncertainties [6]. In other words, replacing on-site works with in-factory prefabricated activities can improve management effectiveness and ensure more accurate project schedule administration [9].

To a large extent, the discussion in the last paragraph supports the idea that using the modular building approach can reduce construction time. It is common sense that time equals money in building projects, and so the reduction in the construction period can control the practical expenditures related to cost management performance and its efficiency [9]. Compared with the conventional construction approach, some scholars agree that using the prefabricated building approach can reduce the total construction costs by approximately 20% and decrease building labour costs by approximately 25% [8,12]. These data indicate that modular construction can modify the excessive labour-intensive and labour-resource demand of developing building projects because the prefabricated works can replace many on-site construction tasks [12,18]. According to relevant research, many academic scholars consider that a relationship should exist between the assembly rate and cost of prefabricated buildings [19]. The cost reduction obtained using modular construction presents a normal distribution curve, and the cost of a PPB reaches the lowest value when its assembly rate is 60% [15]. Compared with a TPB, this research also indicates that the case of a PPB retains its advantages in terms of practical expenditures during the different building project stages, including its design, pre-construction production, and formal building phase [3,15]. It also indicates that the use of prefabricated components in the appropriate range can control the construction budgets and decrease the building costs, especially for the formal erection stage [15]. In other words, from the long-term development perspective, the cost-saving performance of each prefabricated building project can improve the cost efficiency of using this sustainable construction approach during the urban development process, especially for high construction-demand areas [3,11].

Similar to the above considerations, another case study conducted by Afzal et al. also confirms the advantage of using prefabricated constructions for cost-saving performance compared with the traditional building approach [20]. The research team selected the typical building cases using the conventional construction approach and prefabricated technique, respectively, and presented their corresponding schedule-related performance (anticipated schedule and practical time duration) and cost performance (estimated budgets and practical expenditures). Considering the importance of construction and demolition waste management (CDWM) emphasised by many influential academic publications [21,22], the proposed building cases completed by a construction company located in Lahore city of Pakistan shows the cost-saving strengths of using prefabricated components in traditional construction development [3,20]. Specifically, using the prefabricated building technique can save approximately 35% of practical construction expenditures compared with the project using the conventional building technique, and this modular construction project also shows its advantageous performance (e.g., reducing the building schedule duration by approximately 40%) in schedule management [9,20]. Even if some scholars consider that modular construction can increase the initial costs of building projects [19,21,23], the higher operating frequency of using this offsite building technology can improve construction enterprises’ cost efficiency and management performance through their development and transformation [15,20]. Based on the above convincing viewpoints and well-rounded discussions, the suitable adoption of prefabricated constructions can improve the management effectiveness of building projects, including but not limited to cost efficiency; scheduling time duration; labour-force control; and, thus, the overall management performance of construction development.

In addition to improving environmental sustainability and management effectiveness, adopting a prefabricated building approach can improve construction safety and quality [5,12]. In this case, construction safety is not only related to controlling and eliminating the negative safety risks occurring during the building stage but also considers the health issues caused by the construction project on the building stakeholders. In terms of the on-site construction safety aspect, an increasing number of investigations have focused on the application of the prefabricated building technique and its related safety in construction management [6], and many of them agree that this offsite construction approach can decrease the construction safety risks on site and improve project safety, especially during the construction stage [19,21,23]. This situation is because decreasing on-site construction works and labourers can decrease relevant uncertainties and safety issues, simplifying the challenges in safety management, especially for the on-site construction phase, to some extent [12]. The modular construction approach can facilitate a safer working environment compared with the traditional method due to the stable working location, the less risky situation of working high above the ground, the greater than 30% reduction in the on-site construction period, and other related influential elements [6]. During the formal execution of developing modular building projects, the corresponding safety risks can be classified into four groups: foundation-related issues, challenges related to building component transportation, hoisting operation problems, and final assembly risks. Fortunately, by studying the construction practices in the United States and other practical cases in different regions, some effective solutions can deal with these presented problems well, such as stable lifting structures, fall protection systems, regular safety training courses, suitable use of digital technologies for on-site safety supervision, and other aspects [3,6]. Although some consumers may suspect the practical durability and safety of using the prefabricated building technique [12,24], the effective implementation of formal construction and relevant tasks (e.g., experienced assembly workers, strict management supervision, and normalised manufacture of building components) can help deliver qualified, durable, and safe modular construction products to end users, which has been already widely used by some building stakeholders [3,21]. For example, China Vanke, a well-known construction and property development group in China, has been regarded as one of the experienced and leading developers supplying safe and sustainable prefabricated building projects during the past urbanisation process of China [5]. Therefore, the above wide discussion indicates that the appropriate use of modular constructions can improve working safety during the on-site construction stage and other construction-related tasks.

On the other hand, the effective use of modular construction can reduce the negative impacts on building stakeholders’ health. A reliable case study conducted by Tsinghua University of China (one of the top universities and reputable research institutes in China) notes that the prefabricated construction project can decrease the negative impacts of health damage on the project stakeholders [5]. In detail, the results of the investigation (from the adopted building health impact assessment system) indicate that the overall number of health damage issues caused by the case project using the prefabricated technique is reduced by nearly 7% compared to the traditional cast-in-place technique [5,9]. According to the environmental impact assessment report issued by the research team, the claims of change-related illnesses and respiratory-related diseases are decreased by more than 7.4% and 7.0%, respectively [5]. As for the construction workers and other on-site building stakeholders, this offsite construction method can reduce their practical on-site working hours and assist the building labourers in preventing exposure to high temperatures and other horrible weather conditions in many situations [6]. Meanwhile, the use of a modular construction approach can improve environmental sustainability and reduce construction pollutants effectively [14,15,16]; so, the diseases related to climate warming and respiratory system can be positively decreased by preventing work in a high-temperature environment, which is harmful to the construction labours’ health [4,5]. Hence, these figures and facts reveal the internal advantages of reducing the health damage to building stakeholders by adopting prefabricated techniques [5,11].

In addition to decreasing physical health issues, some scholars agree that the suitable adoption of a prefabricated building approach can also reduce and even eliminate mental health issues compared to traditional construction situations [25]. Mental health-related illness is one of the major reasons leading to suicide and other excessively aggressive behaviours. As one of the hardest-hit areas, the construction industry has been negatively impacted by this complex problem, as its suicide rate is over two times the overall national statistical figures in the United Kingdom and Australia [26]. The suicide rate in the construction industry in Australia and the UK is twice and 3.7 times the national average, respectively. This research considers that the major causes of mental stresses and the related unhealthy conditions are relevant to the uncertainties of the construction schedule, excessive dependency on professional workers, terrible construction environment and extreme climate, and other negative factors [3,25,26]. It can be inferred that adopting a prefabricated building approach can provide a stable working environment for building stakeholders and improve the working efficiency on the construction site [6,21]. Compared with the traditional cast-in-place development projects, a decrease in the work intensity (e.g., acceptable workload of on-site construction tasks) and reduction in potentially excessive working stress on construction labourers can mitigate relevant mental health issues in the foreseeable construction development and management [4,25], which can be seen as one of the major strengths of using the prefabricated construction technique.

Furthermore, prefabricated construction can also improve the quality of the delivered building products, decreasing the project deficiencies during its manufacturing, production, and construction stages [3]. Theoretically, many professionals in the building industry claim that this offsite building technique can decrease many on-site construction activities by manufacturing modular building components at assigned fabricated factories in advance [11,27]. For example, many on-site construction tasks, ranging from 60% to 90%, can be prefabricated and completed by the normative building process in standardised manufacturing factories, which can significantly reduce the technical deficiencies caused by manual construction by on-site building labour [12]. Traditionally, the quality of delivering cast-in-place construction projects relies on the proficiency of manual construction skills [3,11], and the constructability of prefabricated buildings (e.g., the modular reinforced cement concrete structure) is more advantageous than the conventional approach. This offsite construction method can mitigate the negative impacts of weather conditions and the inaccuracy of manual construction, which are beneficial for the structural effectiveness and building safety of final products [19,24]. Specifically, during the project lifecycle of a modular construction project, the flow of production of prefabricating the modular components and the standardised process of assembling the manufactured panels on site can decrease the technical deficiencies of the inaccuracy of manufacturing building elements for practical construction based on digital management, which can ensure a higher quality of construction compared to the traditional development mode [6,12]. Three well-known Australian buildings are regarded as representative high-rise building projects adopting HBS and related prefabricated technology. Therefore, the improvements in the construction quality of modular building projects can more likely improve the investment confidence of project developers, providing reassurance to building industry professionals and academics [3,4]. Based on the above comprehensive exploration and explanation, adopting prefabricated building projects can improve environmental sustainability, enhance management effectiveness, and improve construction quality and relevant safety performance of stakeholders, which can be regarded as major strengths in the proposed SWOT analysis.

3.2. Weaknesses of Modular Construction

After discussing the strengths of modular construction, the major weaknesses of this sustainable construction approach, such as the lack of expertise and research, excessively high initial costs, and difficult stakeholder coordination, must also be considered. On the one hand, the lack of expertise and research can be regarded as one of the major internal disadvantages of using modular construction [7,23]. The traditional cast-in-place method is more widely adopted worldwide compared to modular constructions [9], and so many scholars suggest that there is still room for improvement regarding the research and practices of developing modular construction [5,27]. Specifically, modular construction techniques can reduce the working intensity of operating building tasks on the construction site [6]. However, the on-site assembling activities must still be completed by the construction labour [10]. Although employing AI and robotics and promoting human–robot collaboration for undertaking modular building works have been one of the hot spots in prefabricated construction and related fields [28], the manual approach has still been a major trend in recent years, dominating the method of completing the on-site assembly activities [10]. However, labour quality has been one of the major barriers to promoting modular construction projects in China due to the lack of prefabrication-related expertise and insufficient experience [21]. Thus, on-site construction workers need to accept sufficient vocational education and training courses to qualify them to complete the on-site assembly tasks in many developing countries [7,23].

In addition to the lack of expertise, demands for research on modular construction and relevant fields have significantly increased, such as the improvement of prefabricated operation effectiveness and safety, building durability, and the promotion of using this sustainable construction approach in practical building project development [6,12]. Specifically, some building stakeholders may have concerns regarding the safety of using delivered building products, quality systems of operation effectiveness, transportation costs, controlling risks, and other tangible problems embedded in the modular construction lifecycle, which can be seen as the internal advantages of this offsite building method [3,28]. In other words, the lack of expertise and research is one of the major weaknesses of using prefabricated building techniques during its construction development lifecycle, which is also supported by an increasing number of academic scholars [3,7,23]. Based on these considerations, more research on the relevant challenges associated with prefabricated construction management must be conducted and more modular building practices must be completed to improve the insufficient expertise of professional construction teams.

Second, the excessively high initial cost is also considered one of the major weaknesses of initiating and developing prefabricated building projects. Although this offsite development method can reduce the building material wasted during the construction phase to some extent [15,20], many academic scholars support that the initial cost of developing a single modular construction project is excessively high and expensive compared with the traditional method [23,29]. Generally, the management of modular construction’s cost efficiency relies on a sufficient quantity of developed prefabricated building projects and the wide use of this sustainable construction approach for large-scale building development. In other words, only large-scale building projects adopting modular construction techniques can improve their cost-saving performance, and so developing offsite construction projects without sufficient quantity support will likely result in higher initial costs than the conventional method [7,19]. The extra expenditures of using modular construction include but are not limited to additional consultants and design services, costs for the transportation of the modular building elements (from the manufacturing factories to the construction site), and the physical loss of prefabricated components during the on-site assembly stage [3,7,10,19]. The establishment of prefabricated building factories, purchasing related manufacturing facilities, and corresponding maintenance are indispensable during the prefabricated construction development, which is unnecessary for conventional cast-in-place building projects [8,21]. This situation can also increase the initial investment in developing modular building projects and probably reduce the investment confidence from the project developers’ perspective because the financial benefit is one of the major incentives for investors and building developers to initiate the construction projects [7,9]. In other words, the higher initial costs of developing prefabricated building projects compared with traditional construction can be seen as one of the major weaknesses and hindrances of using this sustainable development mode, which many scholars have supported [3,7].

In addition to the above discussions regarding the two typical weaknesses of using modular constructions, difficult and complex stakeholder coordination is also an essential factor impacting the adoption of this offsite approach. In some developing countries, inefficient communication among different stakeholder groups can also cause delays in developing modular construction projects [10]. It is widely accepted that many different project stakeholders are involved in developing modular construction projects, such as building investors, project developers, governmental departments, suppliers, manufacturers, end users, designers, and other building professionals and relevant types of workers [3,29]. Some scholars claim that satisfying employment in modular construction demands support for effective stakeholder coordination. However, stakeholder coordination and communication (including their cooperation effectiveness and efficiency) have still been internal disadvantages of adopting this clean production mode, which many other stakeholders have also advocated [21]. The local government and related departments are important in this scenario [27]. However, some countries still need more effective governmental support (e.g., the modified modular building codes and well-rounded corresponding laws) on the use of this offsite building approach for improving its prevenance in the local building market, such as Iran and some other countries with similar situations [3,9]. Similarly, there is still room for improvement in completing and modifying the modular construction specifications by studying the cases of Singapore and China, and improving the cooperation and communication between the government and building industries is essential [27].

On the other hand, Wu et al. claim that the enterprise culture of construction development companies and relevant entrepreneurial knowledge can significantly influence the acceptance level of embracing the innovative building approach among company employees and building professionals [21], which plays a significant role as one of the major driving factors of using the prefabricated building technique. In other words, construction developers can be considered as some of the most influential stakeholders during practical building project development [29], but the practical effectiveness of stakeholder coordination in the practical development and promotion of modular construction has been a concern of many researchers [3,7,23]. Another case is related to investigating the case of modular concrete construction developed in Lebanon: the authoritative research team described the complexity of communication among various stakeholder groups regarding how to ensure the effective coordination and accurate construction to complete the long spans of hollow-core slabs, which is one of the major challenges in the selected building case supported by the relevant research team [29]. Moreover, instead of the commercial value of this clean production mode, the researchers concentrating on the prefabricated building technique pay more attention to technological development, which can also impede the effective use of modular construction [21]. Based on the above-referenced cases, it can be inferred that the influence of different stakeholder groups on developing modular construction projects varies, causing uncertainties and risks [24], and how to ensure the effectiveness of stakeholder groups becomes one of the challenges of this clean production approach [3,7,21,27]. Therefore, the difficulties and complexities in stakeholder coordination and communication can also be seen as a major weakness in initiating and developing modular construction projects in many situations. Considering the above explanation, the lack of expertise and research, excessively high initial costs, and difficult stakeholder coordination are the main weaknesses of prefabricated building techniques.

3.3. The Opportunity of Modular Construction

The opportunity mainly refers to the external advantages of using modular construction, including, but not limited to, the promotion of SDGs and other policies, Industrial Revolution 4.0, and urbanisation and building demands. First, several scholars prove the interactional relationship between the construction industry and the UN’s SDGs, especially for their high relevance to SDGs 3, 6, 7, 9, 11, 12, 13, and 15 [30]. The modular construction approach can improve the environmental sustainability of building projects and the surrounding environment for stakeholders, which directly or indirectly supports 169 targets presented by the UN from a macro perspective, as discussed before [5,15]. In terms of SDG 3, a representative case illustrates how modular construction can better satisfy human health and relevant well-being. The rapid construction of required hospitals in Wuhan using prefabricated building techniques protected the health condition of residents and impeded the spread of the COVID-19 global pandemic during the outbreak period to a large extent [31]. Additionally, modular construction can reduce polluted water production during the project lifecycle compared with the past construction method, which can be conducive to SDG 6 (e.g., sufficient clean water provision). Specifically, the investigation of 11 cities selected from China proves that suitable C&DW management, which modular constructions can facilitate, contributes to improving the water-saving performance of construction projects [22]. Third, the world has been facing a global energy crisis, and the UN’s SDG 7 (affordable energy) also relies on the wide adoption of modular construction to some extent. This situation is because such offsite construction can better the environmental performance (e.g., decreases in energy consumption and building material use) compared with the traditional method [5,15], and the required energy infrastructure construction and sustainable building development can also assist in dealing with the energy problem globally [3,9].

Regarding the UN’s SDG 9, the modular construction technique can help establish smart factories, speeding up the development of innovative buildings and infrastructure. During the transformation of the construction industry, the application of digital technologies, such as the use of BIM, GIS and VR techniques, into practical modular construction projects can be more conducive to promoting industrial innovation and human-oriented infrastructure compared with the conventional building method [3,9]. On the other hand, the UN’s SDG 11 focuses on developing inclusive cities and safe communities for humans. In fact, modular construction also plays an important role in this process because many scholars advocate the sustainable transformation of building industries and their urban development from the traditional urbanisation and construction methods to the smart governance of inclusive community establishment under the UN’s 2030 SDG agenda [30]. For example, the European Commission presented the concept of the Industrial Revolution 5.0 to ensure human-oriented progress in the Industrial Revolution 4.0 period [32]. Many scholars have already emphasised the importance of using prefabricated building techniques and integrated systems, which can improve the effectiveness of promoting SDG 11. Similarly, since the use of modular construction can reduce construction waste and modify resource depletion [3,5], this advanced building approach can facilitate sustainable consumption and manufacturing output, which is highly relevant to the UN’s SDG 12 [30]. Moreover, the improvements in environmental sustainability made by adopting modular constructions can be beneficial for dealing with the global issue of climate change and protecting the biodiversity of the terrestrial ecosystem [5,15]. In other words, the reductions in carbon emissions and construction pollutants can mitigate the global warming crisis and protect the biodiversity of on-land life, which can be conducive to achieving the UN’s SDGs 13 and 15 to some extent [3]. The above discussions and related investigations in the literature confirm the importance of using modular construction in facilitating the promotion of the UN’s 2030 agenda for SDGs [30], and so it is reasonable to regard the promotion of the UN’s SDGs and other policies as one of the major opportunities for widely adopting the prefabricated construction technique during practical project development.

Second, the Industrial Revolution 4.0 is another typical opportunity for modular construction. The Industrial Revolution 4.0 era promotes modular frameworks, improving operational efficiency and project scope accuracy. Worldwide advocacy and effective implementation of the UN’s SDGs might increase the use of prefabricated buildings, hence alleviating their negative environmental effects [5,9,12]. There are many advantages caused by the Industrial Revolution 4.0 in the practical promotion of modular construction projects. On the one hand, the Industrial Revolution 4.0 can facilitate the wide use of BIM, improving the effective integration of prefabricated construction management and decreasing the conflicts emerging during the project lifecycle [3,17]. Automated production technologies, such as the application of 3D printing and construction robots, can improve the efficiency of resource consumption and construction sustainability of modular building projects [33]. The reduction of resource waste and stakeholder conflicts can improve the project’s success to some extent and encourage the use of modular construction [3]. Additionally, the innovation of IoT can be motivated under the background of the Industrial Revolution 4.0 [28], which is suitable for applying the Just-in-Time (JIT) strategy during the project lifecycle of prefabricated construction. For example, the improvements in IoT can improve supply chain management during the manufacture, production, and transportation of prefabricated building components, which can improve the schedule management and resource-saving performance of modular construction projects [9,28]. Furthermore, the data-driven management mode can optimise the decision-making strategy of the management process and identify the potential risks of implementing modular construction projects in advance [3,34]. The data-driven management mode, application of VR and augmented reality, and suitable adoption of automatic production can improve the safety management and relevant performance of modular construction quality [28,34]. It is common sense that using AR and VR technologies can allow stakeholders to better understand the estimated modular products and corresponding construction effectiveness, which can greatly reduce the misunderstanding of producing the project results and improve the communication efficiency of modular construction. In other words, improvements in modular construction management efficiency (e.g., the potential uncertainties of complex stakeholder management) or the effectiveness of delivering building products can be the incentive for using this sustainable offsite building approach [9]. Based on the above discussions, the Industrial Revolution 4.0 period is another opportunity (or external advantage) for prefabricated construction.

In addition to the positive impacts of the Industrial Revolution 4.0 and the promotion of the UN’s 2030 agenda for SDGs, the practical situation of urbanisation and construction demands worldwide can also be regarded as a major opportunity for modular buildings. Miatto et al. claim that there is still a huge global demand for urbanisation and construction, especially in many underdeveloped regions [35]. However, the increasing urban expansion and corresponding construction demands on residential buildings will likely cause many resources to be wasted and building pollutants to be produced, which indicate the importance of environmental protection, considering the environmental sustainability of construction projects [4,35]. For example, due to the rapid infrastructure development and residential housing demand, the construction sector consumes a large amount of energy in China [3], and its relevant environmental issues and systematic risks have been noticed around the world [9]. The ineffective control and planning of the urbanisation process in Slovakia has caused a decline in the number of green infrastructures, sustainable buildings, and relevant land uses. Thus, many scholars support that how to balance the construction development demand and environmental sustainability has been a wide concern for the global building sector and relevant stakeholders [14,15]. Based on this condition, the urbanisation and construction demands can motivate the use of a sustainable building approach, and modular construction is one of the appropriate options for dealing with this proposed problem [4,5,7]. It is clear that China, the United States, India, Indonesia and Nigeria are the top five countries with high built-up growth expansion from 1990 to 2015, and there are still huge demands for construction development worldwide, especially in developing countries [36,37]. Considering the many convincing investigations, the use of the prefabricated building method is recommended, as it can improve the environmental sustainability of construction projects compared to the traditional cast-in-place method [3,5,13]. Thus, the urbanisation and construction demands can also be seen as a representative opportunity for modular construction.

3.4. Threats of Modular Constructions

The major threats to modular construction, including but not limited to substitute construction technologies, imperfect building codes and standards, and a lack of social and market acceptance, must also be considered. On the one hand, several alternative building approaches can still complete the required construction deliverables. Generally, the construction approach can be divided into the on-site and offsite construction methods [4], and many researchers argue that comparative results are obtained between the on-site and offsite building approaches [15]. In most situations, using the cast-in-place building approach for completing development projects will cause large amounts of construction pollutants to be produced and unsatisfying energy-use efficiency, especially considering its environmental performance under the UN’s SDGs [5,30]. However, the traditional cast-in-place approach is always regarded as the typical onsite building approach that is widely employed worldwide [29]. In other words, such an on-site construction approach has high technical maturity for ensuring successful building delivery because it can be adaptable to deal with complicated construction conditions and ensure safety while considering risky geographical conditions [3,29]. Based on the features and advantages of the conventional cast-in-place building method, its social acceptance and market popularity are relatively high compared with other construction methods, especially for practical building projects developed in underdeveloped regions [3].

On the other hand, 3D printing technology is commonly seen as an innovative building approach, and it can be used for either offsite or on-site construction activities [33,38]. Although the practical application of 3D printing technology for construction projects is still limited to the requirements of the building height and site conditions [3,9,38], this innovative building way can reduce the labour demands and human resources by approximately 60% and save more than 20% of the on-site construction time in some investigations [39]. Due to its benefits for the constructability and sustainability of construction projects, many scholars support the adoption of 3D printing technology in developing building projects compared with the traditional method [40]. For instance, this advanced building approach can improve the construction management performance regarding the project schedule, cost, and quality control [41], and it can also improve environmental sustainability [40]. Based on the above discussions, a few alternatives (e.g., the traditional method of cast-in-place construction and 3D printing building method) exists with specific benefits for building development that could replace the functions of using the modular construction approach [3,29,41]. Thus, modular construction has many different strengths for building projects, considering the UN’s SDGs [5,30], but substitute construction technologies must still be considered as the major threats of modular buildings while promoting this sustainable construction approach.

Second, imperfect building codes and standards can also be considered another threat to the modular construction approach. This building approach is more advantageous than traditional construction, and developing the design codes and building standards for promoting modular construction projects is important. Specifically, the building industry still needs more confidence in applying this sustainable approach to the wide-scale prefabricated construction of high-rise building projects [8]. Due to insufficient design and management experience, there is room for improvement in modifying more completed codes and standards of prefabricated constructions worldwide [42]. This situation can lead to complicated scenarios that cannot ensure the qualified seismic design and practical constructability during the project’s whole lifecycle [3]. Based on this condition, many other scholars also support the viewpoint that imperfect corresponding codes and standards can impede the wide use of modular construction in different types of construction development [21]. For instance, adopting fabricated building members to consistently ensure the effectiveness between the design and modular construction stage is challenging because of inadequate standards [8].

There are also deficient codes (whether in architectural or structural building design) and imperfect regulations for ensuring the accuracy of erecting modular construction projects on-site and promoting this sustainable building approach [8]. In the construction industry, completed and reliable building codes and standards are widely accepted to play indispensable roles in developing successful projects [7,9], which is similarly supported by the case analysis conducted in Saudi Arabia [43]. Without guidance from professional building codes and standards of prefabricated construction projects, ensuring the effectiveness and consistency of implementing the outputs from the design stage to the practical execution phase is difficult, which will likely cause unsatisfying feedback from stakeholder evaluation and even project failure [3,44,45]. Thus, an increasing number of building professionals and academic scholars emphasise the significance of developing more completed and reliable codes and standards for delivering and promoting prefabricated construction projects [8,42,44,45]. In other words, this situation means that the current design codes and building standards are not that comprehensive and perfect, and Xu et al. also note that the modular construction specifications in different regions (e.g., China and Singapore) still need to be improved and modified more comprehensively [27]. Therefore, imperfect building codes and standards must be regarded as a major threat to the use of modular construction.

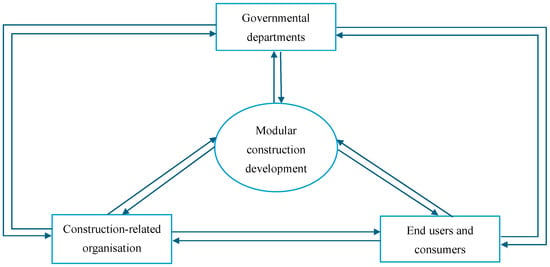

In addition to the above two threats, the lack of social and market acceptance in many regions can also be considered one of the main negative factors of using the modular construction approach. As shown in Figure 2, the important roles of three types of stakeholder groups in facilitating the wider promotion of using modular construction in different countries and regions must be recognized. In terms of low-level social acceptance, although many scholars support the safety guaranteed by prefabricated buildings [46], a large number of public and non-professionals are unfamiliar with the concept of modular construction, so they may subjectively advocate that traditional building methods are safer than the prefabricated method during the development of this offsite construction approach. For example, they could be concerned about some risks to structural performance and insist that the offsite building approach cannot be used to complete the construction project based on the quality requirements [18]. On the other hand, modular construction may be restricted to accomplish monotonous types of required building products; so, many public and residents cannot express sufficient passion for developing prefabricated buildings in order to protect the traditional style of buildings [3,9]. As for the inferior market acceptance in some developing regions, many building professionals and construction workers have been habituated to the wide use of the traditional on-site construction method due to industry inertia [18,47]. For instance, some designers express aesthetic concerns when using the prefabricated building approach, and the attitudes towards using this offsite method vary for different types of stakeholder (e.g., modular building contractors and prefabricated manufacturers), which has been proven by a case study conducted in Lebanon [29]. Generally, many building professionals are more familiar with the adoption of the cast-in-place construction approach than the modular building approach [9], and thus the industrial unwillingness and market uncertainties to hinder innovation and promotion of this offsite method must be considered [18]. As explained in the last paragraph, it can be inferred that the imperfect building codes, standards, and specifications of implementing modular building projects can also decrease the market incentives and shareholder confidence in investing in prefabricated construction projects [8,42,44,45]. Based on these considerations, the lack of social and market acceptance must be regarded as one of the major threats to using and facilitating the promotion of modular construction.

Figure 2.

The three-party stakeholder groups facilitating the use of modular construction. Arrows mean they are interactive or could impact each other considering the different scenarios.

4. Conclusions and Prospects

After exploring the SWOT analysis of using modular constructions, an understanding of how to determine a successful construction project under the project lifecycle concept is necessary. In project management disciplines, a large number of people generally agree that construction can be regarded as a typical project. By reviewing reputable sources, a project is commonly seen as a working effort under a limited time boundary, which can produce non-copyable deliverables. Based on this concept, the endeavour involved in construction has a certain lifecycle and delivers unique building products to the end users, which can satisfy the project definition. Prefabricated construction is one of the typical construction modes, and so it is essential to ensure the critical factors for the successful development of modular construction. The five most important critical factors for the successful implementation of the concept of circular economy into modular construction projects include the in-time design completed at the early stage, leadership provided by professional contractors, support and commitment made by major clients, sufficient knowledge reserve of the project team, and effective stakeholder coordination and information sharing. The stakeholder plays an important role in ensuring the project’s success in developing modular construction from a sustainable perspective. Considering the relevant concept of the construction project management field, a successful modular construction project needs to satisfy the schedule, quality, and cost requirements under effective scope management, which is usually defined as the triple constraints in the project management discipline. In order to promote it more smoothly, it is essential to realise the corresponding barriers (e.g., threats and weaknesses of promoting modular constructions). Compared with other replaceable construction methods (e.g., the cast-in-place building project), it is significant for modular construction to have more advanced performance in the aspects of constructability, sustainability, and management efficiency. This situation can improve the stakeholders’ experience and benefits by allowing them to participate in modular construction projects as internal stakeholders or be positively affected by prefabricated building projects as external stakeholders. In other words, successful modular construction not only achieves the established scope and targets regarding the building quality, cost estimation, project schedule, and safety requirements from a project perspective but also needs to ensure the satisfaction of different stakeholder groups involved in a prefabricated building project from a macro perspective. Thus, these factors must be considered when someone aims to initiate and develop a sustainable modular construction project successfully.

In further research, it is important to conduct sufficient first-hand data collection and evaluation to validate and modify the current study. Numerous studies highlight the pertinent reasons and challenges associated with the replication and advancement of building projects in the last decade. Evaluating the advantages and disadvantages of using prefabricated technology in construction projects within project lifecycle considerations is crucial for attaining the UN’s SDGs. A construction project typically has a prolonged duration, complicating the focus on a singular aspect or phase when evaluating the factors influencing the advancement and evolution of prefabricated building projects. Under the present conditions, a thorough literature review and an empirical data analysis must be conducted to investigate the principal factors influencing the practical advancement and extensive adoption of the prefabricated building method in construction projects across the project lifecycle. The Project Management Body of Knowledge delineates the project lifecycle into distinct and independent phases, from inception to conclusion. In further research, the proposed topic must be explored in the long-term development process and typically encompasses five discrete stages: conceptual design and decision-making analysis, pre-construction preparation, formal construction and product delivery, operation and maintenance, and waste and demolition after the building’s lifecycle. Therefore, it is prudent to examine the determinants affecting the success of building projects using the project lifecycle analysis framework.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.Z. and D.S.; methodology, Z.Z.; software, Z.Z.; validation, D.S., Y.K., X.F. and Z.Z.; formal analysis, Z.Z.; investigation, Z.Z. and Y.K.; resources, Z.Z.; data curation, D.S.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.Z.; writing—review and editing, D.S. and X.F.; visualization, D.S.; supervision, D.S.; project administration, Z.Z.; funding acquisition, Z.Z. and D.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Sichuan Provincial Bureau of Statistics and its funding project titled “Research on the Collaborative Application of Building a Circle and Strengthening the Chain of Low-Altitude Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Logistics Industry in Chengdu–Deyang–Mianyang” (Grant Number 2025XL02).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

During the development of this review, the authors express their sincere appreciation for the support from the guidelines from the “2025 Chongzhou City Philosophy and Social Sciences Planning Project” and the support from the UCSI University in Malaysia and Tianfu College of SWUFE in China.

Conflicts of Interest

Yuping Kou, engineering management specialist, Specialised Engineering Branch, Sichuan Road & Bridge Co., Ltd, Sichuan Province. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Benzaghta, M.A.; Elwalda, A.; Mousa, M.M.; Erkan, I.; Rahman, M. SWOT analysis applications: An integrative literature review. J. Glob. Bus. Insights 2021, 6, 54–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agha, A.; Shibani, A.; Hassan, D.; Zalans, B. Modular construction in the United Kingdom housing sector: Barriers and implications. J. Archit. Eng. Technol. 2021, 10, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Syamsunur, D.; Wang, L.; Nugraheni, F. Identification of Impeding Factors in Utilising Prefabrication during Lifecycle of Construction Projects: An Extensive Literature Review. Buildings 2024, 14, 1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Syamsunur, D.; Wang, X. The implication of using modular construction projects on the building sustainability: A critical literature review. Adv. Urban Eng. Manag. Sci. 2022, 1, 422–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Li, X.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, Z. A comparative study of environmental performance between prefabricated and traditional residential buildings in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 109, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fard, M.M.; Terouhid, S.A.; Kibert, C.J.; Hakim, H. Safety concerns related to modular/prefabricated building construction. Int. J. Inj. Control Saf. Promot. 2017, 24, 10–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, R.; Mao, C.; Hou, L.; Wu, C.; Tan, J. A SWOT analysis for promoting offsite construction under the backdrop of China’s new urbanisation. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 173, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thai, H.T.; Ngo, T.; Uy, B. A review on modular construction for high-rise buildings. Structures 2020, 28, 1265–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Syamsunur, D.; Wang, L.; Kit, A.C. Exploring the feasibility of using modular technology for construction projects in island areas. J. Infrastruct. Policy Dev. 2024, 8, 3424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Qi, L.; Liu, Y.; Liu, X.; Li, H.X.; Li, Y. Assessing and prioritising delay factors of prefabricated concrete building projects in China. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z. The Obstacles to Promoting the Modular Building Project: A Tentative Assessment of the Literature. In Technological Innovation in Engineering Research; BP International: London, UK, 2022; Volume 6, pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navaratnam, S.; Ngo, T.; Gunawardena, T.; Henderson, D. Performance review of prefabricated building systems and future research in Australia. Buildings 2019, 9, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Pan, W. Reducing construction waste through modular construction. In International Symposium on Advancement of Construction Management and Real Estate; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2021; pp. 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Chowdhury, M.M.; Issa, R.R.; Shi, W. Simulation of dynamic energy consumption in modular construction manufacturing processes. J. Archit. Eng. 2018, 24, 04017034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, W.; Kuroki, S. Life cycle environmental and cost performance of prefabricated buildings. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdous, W.; Bai, Y.; Ngo, T.D.; Manalo, A.; Mendis, P. New advancements, challenges and opportunities of multi-storey modular buildings–A state-of-the-art review. Eng. Struct. 2019, 183, 883–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.X.; Luther, M.; Mills, A. Prefabrication in the Australian context. In Modular and Offsite Construction (MOC) Summit Proceedings; University of Alberta: Edmonton, AB, Canada, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, A.M.; Arantes, A.; Cruz, C.O. Barriers to the Adoption of Modular Construction in Portugal: An Interpretive Structural Modeling Approach. Buildings 2022, 12, 1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.; Shen, G.Q.; Li, Z.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, W. Barriers to promoting prefabricated construction in China: A cost–benefit analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 649–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzal, M.; Maqsood, S.; Yousaf, S. Performance evaluation of cost saving towards sustainability in traditional construction using prefabrication technique. Int. J. Eng. Sci 2017, 5, 73–79. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, G.; Yang, R.; Li, L.; Bi, X.; Liu, B.; Li, S.; Zhou, S. Factors influencing the application of prefabricated construction in China: From perspectives of technology promotion and cleaner production. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 219, 753–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Chen, R.; Yuan, H.; Yong, Q.; Weng, X.; Zuo, J.; Zillante, G. An evaluation model for city-scale construction and demolition waste management effectiveness: A case study in China. Waste Manag. 2024, 182, 284–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuni, I.Y.; Shen, G.Q. Barriers to the adoption of modular integrated construction: Systematic review and meta-analysis, integrated conceptual framework, and strategies. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 249, 119347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuni, I.Y.; Shen, G.Q.; Mahmud, A.T. Critical risk factors in the application of modular integrated construction: A systematic review. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2022, 22, 133–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagbenro, R.K.; Sunindijo, R.Y.; Illankoon, C.; Frimpong, S. Influence of prefabricated construction on the mental health of workers: Systematic review. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2023, 13, 345–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, A.P.; Nwaogu, J.M.; Naslund, J.A. Mental ill-health risk factors in the construction industry: Systematic review. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2020, 146, 04020004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z.; Zayed, T.; Niu, Y. Comparative analysis of modular construction practices in mainland China, Hong Kxong and Singapore. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 245, 118861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.Z.; Chen, Z.; Xue, F.; Kong, X.T.; Xiao, B.; Lai, X.; Zhao, Y. A blockchain-and IoT-based smart product-service system for the sustainability of prefabricated housing construction. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 286, 125391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamzeh, F.; Abdul Ghani, O.; Saleh Bacha, M.B.; Abbas, Y. Modular concrete construction: The differing perspectives of designers, manufacturers, and contractors in Lebanon. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2017, 24, 935–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, W.; Opoku, A.; Agyekum, K.; Oppon, J.A.; Ahmed, V.; Chen, C.; Lok, K.L. The critical role of the construction industry in achieving the sustainable development goals (SDGs): Delivering projects for the common good. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Chen, Y.; Su, X.; An, L. Rapid construction and advanced technology for a Covid-19 field hospital in Wuhan, China. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Civ. Eng. 2020, 174, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghobakhloo, M.; Iranmanesh, M.; Tseng, M.L.; Grybauskas, A.; Stefanini, A.; Amran, A. Behind the definition of Industry 5.0: A systematic review of technologies, principles, components, and values. J. Ind. Prod. Eng. 2023, 40, 432–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosravani, M.R.; Haghighi, A. Large-scale automated additive construction: Overview, robotic solutions, sustainability, and future prospect. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Li, Z.; AbouRizk, S. Automating common data integration for improved data-driven decision-support system in industrial construction. J. Comput. Civ. Eng. 2022, 36, 04021037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miatto, A.; Dawson, D.; Nguyen, P.D.; Kanaoka, K.S.; Tanikawa, H. The urbanisation-environment conflict: Insights from material stock and productivity of transport infrastructure in Hanoi, Vietnam. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 294, 113007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denis, E. More urban constructions for whom? Drivers of urban built-up expansion across the world from 1990 to 2015. In Theories and Models of Urbanization: Geography, Economics and Computing Sciences; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 235–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Zhou, L.; Li, Y.; Liu, H.; Shen, X.; Wang, Z.; Wang, X. New-type urbanisation in China: Predicted trends and investment demand for 2015–2030. J. Geogr. Sci. 2017, 27, 943–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Gehlot, A.; Akram, S.V.; Gupta, L.R.; Jena, M.K.; Prakash, C.; Singh, S.; Kumar, R. Cloud manufacturing, internet of things-assisted manufacturing and 3D printing technology: Reliable tools for sustainable construction. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Huang, S.; Han, D.; Zhang, Z.; Gao, Y.; Feng, P.; Zhang, D. Toward automated construction: The design-to-printing workflow for a robotic in-situ 3D printed house. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2022, 17, e01442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sayegh, S.; Romdhane, L.; Manjikian, S. A critical review of 3D printing in construction: Benefits, challenges, and risks. Arch. Civ. Mech. Eng. 2020, 20, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.A.; Zhumabekova, A.; Paul, S.C.; Kim, J.R. A review of 3D printing in construction and its impact on the labor market. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Lee, M.W.; Jaillon, L.; Poon, C.S. The hindrance to using prefabrication in Hong Kong’s building industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 204, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamoussi, B.; Abu-Rizaiza, A.; AL-Haij, A. Sustainable building standards, codes and certification systems: The status quo and future directions in Saudi Arabia. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdous, W.; Manalo, A.; Sharda, A.; Bai, Y.; Ngo, T.D.; Mendis, P. Construction industry transformation through modular methods. In Innovation in Construction: A Practical Guide to Transforming the Construction Industry; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 259–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wang, J.; Wu, J.; Shi, W.; Ji, D.; Wang, X.; Zhao, X. Constraints hindering the development of high-rise modular buildings. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 7159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, G.; Kim, H.; Lee, H.S.; Park, M.; Hyun, H. Analysis of safety risk factors of modular construction to identify accident trends. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2022, 21, 1040–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldmann, F.G.; Birkel, H.; Hartmann, E. Exploring barriers towards modular construction—A developer perspective using fuzzy DEMATEL. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 367, 133023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.