Abstract

Objectives: This systematic review aimed to examine hip rotator range of motion (ROM) and strength values across athletic, injured, and non-active populations, and to determine how these values differ when measured at different hip flexion angles. Methods: A systematic literature search was conducted in accordance with PRISMA guidelines across six electronic databases (PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, SPORTDiscus, CINAHL, and Medline) from inception to June 2025. Eligible studies included observational, cross-sectional, case-control, or randomized controlled trial (RCT) studies that quantitatively assessed hip IR/ER ROM and/or strength in defined population groups (athletic, injured, or non-active). Two reviewers independently screened titles, abstracts, and full texts, extracted data on study design, population characteristics, measurement methods, and outcome variables, and assessed risk of bias using an established tool. Discrepancies were resolved by a third reviewer. Results: 11 studies met the inclusion criteria, including 1276 participants across athletic, injured, and non-active populations. Hip rotator ROM was measured in nine studies and strength in three, with varying testing angles (0° and/or 90° hip flexion). Overall, athletes showed greater ROM at 0° compared to injured and non-active groups, but had reduced ROM at 90° relative to non-active participants. Non-active individuals had the lowest ROM at 0°. Strength findings, though limited, indicated higher values at 90° than at 0°. Conclusions: Hip rotator ROM and strength vary across populations and testing angles, with ROM generally lower and strength higher at 90° of hip flexion. Due to methodological inconsistencies, findings should be interpreted as directional evidence, reinforcing the need for standardized assessment protocols in future research.

1. Introduction

Assessments of hip joint strength and range of motion (ROM) are commonly employed for clinical evaluation of hip and groin pain [1]. These assessments are utilized not only in athletic populations [1,2], but also in populations with hip pathologies such as hip osteoarthritis (OA) [3,4,5,6]. However, while research has extensively explored hip flexion, extension, and abduction, research specifically focusing on ROM and strength of hip rotator muscles remains limited.

The hip has been implicated as a contributing factor to inguinal pain, yet few publications or prevention programs specifically assess hip rotator function [7]. In patients with patellofemoral pain (PFP), reduced hip abduction and external rotation (ER) strength are frequently observed, and an altered internal to external rotation (IR/ER) strength ratio has been proposed as a contributing factor [8].

In athletic populations, femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) is recognized as a risk factor for early hip joint degeneration, with the typical injury mechanism involving combined hip flexion, adduction, and IR; movements that place substantial demand on the hip rotators [9,10]. Additionally, neuromuscular imbalances have been suggested as potential risk factors for these injuries [11,12]. Limited hip rotational capacity has also been identified as a contributing factor in the development of both FAI and anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries [13]. Despite growing interest, assessment strategies for hip IR and ER ROM and strength remain inconsistent across the literature.

To date, no systematic review has investigated how hip rotator strength and ROM vary across populations or how they are influenced by testing position. Clarifying these patterns is essential to guide screening, rehabilitation, and performance strategies. This systematic review aimed to investigate hip rotator ROM and strength values across different populations, specifically to determine whether (a) these values differ according to participant level of physical activity, and (b) whether they vary when measured using different hip flexion angles.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol and Registration

This systematic review was conducted following the guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 [14] and is registered in the PROSPERO database (ID: CRD42023428661). The completed PRISMA checklist can be found in Figure S1.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

Eligibility criteria were defined in accordance with the PRISMA-P framework. Studies were included if they involved male participants aged 18 to 65 years, comprising athletic, non-athletic, and/or injured populations. Eligible studies assessed hip IR and/or ER strength and/or ROM, measured at 0° and/or 90° of hip flexion. Strength had to be evaluated using isometric methods, reported in Newtons (N) or kilograms (kg), with validated tools such as handheld dynamometers. ROM had to be reported in degrees. Studies were included if they compared outcomes between flexion angles (0° vs. 90°), participant groups (e.g., injured vs. healthy, athletic vs. non-athletic), or limb status (e.g., dominant vs. non-dominant, injured vs. uninjured).

Primary outcomes included hip IR/ER strength and ROM values, reported numerically as means and standard deviations, medians with interquartile ranges, or in formats convertible to these metrics. Eligible study designs were randomized controlled trials, case-control studies, and observational studies (cross-sectional or cohort).

Studies were excluded if participants had undergone hip-related surgical procedures, if outcome data were not numerically presented or could not be obtained from authors upon request, or if the outcomes of interest, hip IR/ER strength or ROM at specified hip flexion angles, were not reported.

2.3. Information Sources and Search Strategy

An extensive literature search was conducted using the electronic databases PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, SPORTDiscus, CINAHL, and Medline. The search was carried out in June 2025, using a specific search syntax. Filters were applied to include only case-control studies, observational studies, or randomized controlled trials (RCTs). To enhance the comprehensiveness of the search, reference lists of all eligible articles and relevant systematic reviews were manually screened for additional studies that met the inclusion criteria.

2.4. Selection Process

Titles and abstracts retrieved through the database search were screened independently by two reviewers (M.F.-M., C.S.-A.) to assess their relevance to the review topic. Articles deemed potentially eligible were then reviewed in full text. Discrepancies between reviewers were resolved by consultation with a third researcher (J.B.-M.), who made a final decision based on alignment with the predefined inclusion criteria. Only studies that achieved a score of six or higher on the PEDro scale were considered methodologically sound and included in the final synthesis (see Table S1).

2.5. Data Items

Extracted variables included author(s), participant classification (e.g., athlete, non-active, injured), underlying pathology (if applicable), study design, sample size, participant sex, mean age, study duration, intervention details, comparison group (if any), measurement tools used, outcome units, and specific strength and ROM variables assessed.

The primary outcomes of interest were passive hip IR and ER ROM and maximal voluntary isometric contraction (MVIC) of the hip rotator muscles. All outcomes were recorded as means and standard deviations (SD). To account for methodological heterogeneity, all reported strength and ROM measurements were included, and assessments were categorized by the angle of hip flexion (0° or 90°). When studies involved multiple population groups—such as athletes, injured individuals, or non-active participants—outcome data were classified accordingly for subgroup analysis. In cases where essential outcome data were missing or unclear, study authors were contacted to request additional information. Three authors were contacted; one responded with partial data, while the remaining two did not reply.

2.6. Study Risk of Bias Assessment

The methodological quality of all included studies was assessed using the Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro) scale. Two reviewers independently rated each study, with disagreements resolved through discussion or consultation with a third reviewer. The PEDro scale evaluates internal validity based on criteria such as random allocation, baseline comparability, blinding, and adequacy of follow-up [15]. This approach ensured a consistent evaluation of internal validity across both randomized and non-randomized designs.

2.7. Synthesis Methods

Given the variability in outcome measures across included studies, a categorical grouping approach was used to facilitate synthesis and comparison. Studies were organized into six outcome categories based on the type of measurement and hip flexion angle: (1) IR ROM at 0°, (2) IR and ER ROM at 0°, (3) IR and ER ROM at 90°, (4) ER strength at 0°, (5) IR and ER strength at 0°, and (6) IR and ER strength at 90°. Several studies contributed data to more than one category, and population differences (e.g., non-active, injured, athletic) were accounted for in subgroup comparisons.

To ensure comparability, data conversions were performed where necessary. Values reported in °/kg were converted to absolute units (degrees) using participant body mass provided in the original studies, and values converted from N to kg-force were divided by 9.81 m/s2 to account for gravitational acceleration [16]. Details of the conversion procedures are provided in Supplementary Materials.

Although meta-analysis was initially considered, variability in measurement protocols, flexion angles, and reporting units prevented statistical pooling. Due to these inconsistencies and the small number of studies reporting comparable outcomes, calculation of I2 to assess heterogeneity was not feasible, and statistical pooling was deemed inappropriate. As a result, findings were synthesized descriptively and organized into summary tables for structured comparison.

2.8. Reporting Bias Assessment

To assess reporting bias across studies, a comparative table was created to highlight methodological differences that could influence the presentation of results, including the units of measurement used, hip flexion angles assessed (0° or 90°), the presence or absence of a control group, and the population type (athletic, injured, or non-active) (see Table S2).

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

A total of 371 records were identified through six databases, including PubMed (n = 199), Scopus (n = 16), Web of Science (n = 96), SPORTDiscus (n = 4), CINAHL (n = 26), and Medline (n = 30). No records were removed prior to screening. Following title and abstract screening, 298 records were excluded, leaving 73 reports for full-text review. All reports were successfully retrieved for eligibility assessment. Of these, 62 reports were excluded for the following reasons: duplication across databases (n = 11), not aligned with the study aim (n = 33), lack of hip rotator measurements (n = 17), and lack of hip flexion measurement angle (n = 1). A PRISMA Flow Diagram [14,17] of the literature search results can be found in Figure S2.

Across the 11 included studies, a total of 1276 participants were assessed, including 721 athletes (soccer, Gaelic football, field hockey, Australian football, and soft tennis players), 309 participants with injuries (long-standing groin pain, low back pain (LBP), or PFP), and 246 healthy controls, with several studies reporting on more than one group type. As for variables, nine studies measured hip IR and/or ER ROM [18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26] and three assessed hip rotator strength [26,27,28], with Girdwood 2023 evaluating both outcomes. For ROM, five studies tested at 0° hip flexion and four tested at 90°. For strength, two studies measured at 0°, one at 90°, with Hoglund et al., 2014 [27] testing at both flexion angles.

3.2. Study Characteristics

For the included articles, Table 1 provides detailed information on the population, variables measured, and outcomes assessed. Table 2 shows the methods used to evaluate ROM and strength in each article.

Table 1.

Population, measurements and outcomes reported in included studies.

Table 2.

Table display of methods used for ROM and strength evaluations in each article.

3.3. Results of Individual Studies

Tables S3 and S4 exhibit the outcomes of each study individually, analyzing ROM and strength, respectively, illustrating the mean values, SD, confidence intervals, and the total number of participants engaged in each study.

3.4. Results of Syntheses

3.4.1. Comparison Between Populations

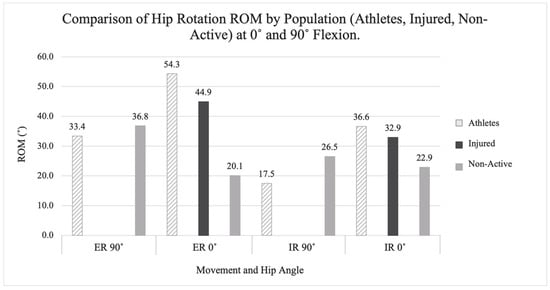

Comparison of hip IR and ER ROM across athletic, injured, and non-active populations, measured at 0° and 90° hip flexion, can be found in Figure 1. Group pooled averages were calculated by taking the mean of the reported means from each eligible study. Overall, athletes demonstrated lower IR and ER ROM at 90° compared to non-active participants. ROM values for injured participants were not available at 90° from the included studies. At 0° of hip flexion, athletes generally displayed the highest ROM values, followed by injured participants, with non-active individuals demonstrating the lowest averages.

Figure 1.

Comparison of hip rotation ROM by population and hip flexion measurement angle [18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26]. Note: Bars represent average values pooled from the included studies for each population. Values for injured participants at ER 90° and IR 90° were not available. Abbreviations: ROM: range of motion, IR: internal rotation, ER: external rotation.

Strength outcomes were reported in only three studies, primarily in non-active populations, with limited data available for athletic and injured participants. Across the available studies, athletic populations tended to show greater hip IR and ER strength values than non-active participants when measured at 0° hip flexion, with no comparison available for measurements at 90°. However, due to the scarcity of strength data, population-level comparisons were not visualized and should be interpreted cautiously (specific values can be found in Table S4).

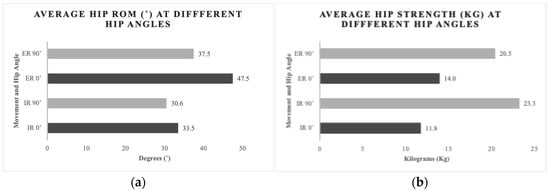

3.4.2. Comparison Between Hip Flexion Angles

Figure 2 summarizes the pooled average values for hip IR and ER and strength at 0° and 90° of hip flexion across all studies. Both ROM and strength varied with hip testing angle, with IR and ER ROM showing lower values at 90° compared to 0°. On the contrary, for hip rotator strength, Figure 2b illustrates that hip rotator strength increases substantially when measured at 90° compared with 0° of hip flexion for both muscle groups. At 0°, ERs demonstrated greater strength than IRs (14 kg vs. 11.8 kg). However, at 90°, this relationship reversed, with IRs reaching 23.3 kg compared to 20.5 kg for ERs.

Figure 2.

Average hip rotation ROM and strength at 0° and 90° hip flexion. (a) Pooled average IR and ER ROM across all populations [18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26]. (b) Pooled average IR and ER strength across all populations [26,27,28]. Abbreviations: IR: internal rotation, ER: external rotation.

3.4.3. Reporting Biases

Comparing the measurement modalities across studies, we observed that for ROM measurements, three out of seven studies measured hip rotations at 90° hip flexion, and five measured at 0° hip flexion. With regards to strength, one study measured hip rotation strength at 0° hip flexion, and one took measurements both at 90° and 0° hip flexion (Table 2).

In addition, stabilization protocols to prevent unwanted movement varied among studies. Four out of ten studies employed strapping, three used manual pressure, one used a spirit level, one used a roll, and one study did not specify any stabilization method during measurements.

Another important factor to note was whether measurements were taken from both legs. Most studies considered measurements from both limbs. However, two studies specified that the published values were average values from both legs.

4. Discussion

This systematic review synthesized findings on hip rotator ROM and strength across athletic, injured, and non-active populations, examining whether these measurements differ by activity level and hip flexion angle. Overall, athletes demonstrated greater ROM at 0° hip flexion compared to injured and non-active populations, but experienced notable reductions at 90° when compared to non-active participants. Non-active groups generally showed lower ROM than both athletes and injured participants at 0°, with insufficient data to assess values across all three groups at 90°. Strength outcomes, although limited, indicated that both IR and ER strength were substantially greater at 90° than at 0°, with IRs showing the highest values in flexed positions. These findings confirm that both population type and testing angle could influence hip rotator characteristics.

4.1. Hip Rotator ROM

Injured populations consistently exhibited high IR and ER ROM compared to controls at 0°, findings that do not align with studies on patellar tendinopathy, PFP, chronic ankle instability, and post-ACL reconstruction [29,30,31,32,33]. An explanation for this could be due to the higher ER values seen in Tak et al. 2017 [21], which implemented a side-lying approach to measurement taking. Furthermore, findings show that athletes had greater IR ROM compared to injured and non-active participants. These findings could be explained by specific sport-related movements [11,12]. Tak et al. 2017 further noted ROM deficits in sport-specific postures, emphasizing the functional consequences of mobility restrictions [21]. Cadaveric and in vivo studies, such as Delp et al. 1999, demonstrated that IR ROM increases while ER decreases as the hip flexes [34], a pattern seen in the present findings across IR but not ER measurements, although differences in ER were lower than those of IR. Knee flexion has also been shown to increase ROM measures due to biarticular muscle involvement [35]. The standardized use of 90° knee flexion during testing in most studies helps control for this effect.

4.2. Hip Rotator Strength

Data on the effect of injuries on hip rotator values remains sparse. Patients with patellar tendinopathy (PT) were studied by Mendonça et al. 2018 and Zhang et al. 2018 with both studies identifying reduced MVIC for hip abductor and ER compared to controls [30,31]. A decrease in hip ER was also observed in patients with chronic ankle instability and post-ACL reconstruction as compared to control groups [31,32], with another study stating that a decrease in hip ER strength at baseline could be a predictive measure for possible ACL injuries in male and female athletes [36]. In addition, for hip IR, a decrease was observed in patients with PFP [33]. Finally, another study found no difference between karate athletes and active controls and attribute their results to possible sport-specific adaptations [37]. However, due to the lack of strength data on injured participants in this review, no specific comparison can be made with available data on this population.

Strength findings, though limited to two studies, align with previous literature examining gluteal activation and torque production during rotation at different angles [38]. Peduzzi de Castro et al. 2021 reported increased activation of the gluteus maximus and medius with greater hip flexion, with the gluteus medius middle fibers and upper gluteus maximus contributing more substantially to IR torque beyond 30° and 50°, respectively [38]. These recruitment patterns, while physiologically relevant, can complicate strength assessment. Some have proposed prioritizing 0° testing to standardize evaluation [38]. Although not systematically analyzed here, changes in the IR/ER strength ratio depending on testing angle may offer relevant insights into neuromuscular function and warrant future exploration.

When assessing hip muscles in injured patients, the muscle movement most assessed in scientific articles is hip flexion [32]. There is a substantial difference in the amount of information available when assessing hip flexion and extension compared to hip rotators in injured populations. These findings suggest that current hip assessment practices may not fully capture functional strength and ROM profiles, particularly in athletic or injured populations, where testing at different hip flexion angles could reveal important deficits or imbalances. Clinicians should be aware that testing hip rotation strength or ROM at different flexion angles may yield divergent results, influencing diagnosis, monitoring, and rehabilitation planning. Hence, more studies investigating the effects of hip rotator muscles in injured participants could enable a more comprehensive understanding of the hip complex, potentially informing approaches for their prevention and/or future rehabilitation.

4.3. Study Strengths and Limitations

This review’s strengths include a comprehensive search strategy across multiple databases, inclusion of different populations, and review of the existing literature on both ROM and strength outcomes across different testing positions. However, several limitations should be acknowledged. Strength data were limited, particularly for injured populations, restricting the ability to draw complete population-level comparisons. Notably, only three studies assessed rotator strength, despite its functional relevance in sports and rehabilitation contexts. This highlights a significant gap in the literature and underscores the need for further research specifically targeting hip rotator strength at differing flexion angles. Methodological heterogeneity, including differences in stabilization protocols, dynamometer use, body positioning, and varying athletic and injury backgrounds, complicates direct comparisons across studies. Additionally, the inability to perform a meta-analysis due to the substantial variability in reporting and measurement protocols among the included studies. As a result, a narrative synthesis was adopted to preserve methodological integrity and allow meaningful interpretation within outcome-specific categories.

4.4. Implications for Future Research

This systematic review underscores the critical need for standardized measurement protocols in assessing hip rotator strength and ROM. Inconsistent methodologies across studies have led to inconclusive findings, highlighting the challenge of drawing definitive conclusions about the variations in hip rotation strength and mobility across different populations. Future research should prioritize developing and adhering to standardized measurement techniques to ensure data comparability and reliability. Additionally, further studies should explore the biomechanical and physiological mechanisms underlying the observed differences in hip rotation strength and mobility among athletic, injured, and non-active populations. While this review does not evaluate the direct relationship between hip rotator function and injury risk, the findings suggest that differences in strength and ROM across populations and testing positions might hold clinical relevance. This highlights the need for further research to explore whether such characteristics could serve as screening indicators or therapeutic targets in prevention and rehabilitation settings. Furthermore, standardized methodologies will also facilitate meta-analyses and systematic reviews, ultimately contributing to more robust evidence-based practices in clinical and athletic settings.

5. Conclusions

This review identifies meaningful trends in hip rotator ROM and strength across populations and testing angles. Athletes exhibit reduced IR ROM at 90° relative to non-active participants, while non-active individuals show lower ROM at 0° compared with athletes and injured groups. Overall, IR and ER ROM values are lower when measured at 90° hip flexion, whereas strength values are substantially greater when measured at 90° hip flexion, with IRs producing the highest outputs in flexed positions. However, inconsistencies in measurement protocols, units, and testing methods across studies prevent precise quantification of these differences. These results highlight the importance of standardized assessment methods and should be interpreted as directional evidence until more uniform data are available.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/encyclopedia5040170/s1, Figure S1: PRISMA Checklist; Figure S2: PRISMA flow diagram; Equation (S1): Formula for conversion of degree/kg to degree; Equation (S2): Formula for conversion of N to Kg; Table S1: PEDro scale outcomes for study risk of bias assessment; Table S2: Factors evaluating reporting bias across studies; Table S3: Individual outcomes for ROM values across studies; Table S4: Individual outcomes for strength values across studies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.B.-M. and L.G.-L.; methodology, M.F.-M. and C.S.-A.; software, J.F.-G.; validation, M.F.-M., C.S.-A., and J.B.-M.; formal analysis, M.F.-M.; investigation, M.F.-M. and C.S.-A.; resources, J.B.-M. and L.G.-L.; data curation, M.F.-M. and J.B.-M.; writing—original draft preparation, M.F.-M.; writing—review and editing, J.F.-G. and J.B.-M.; visualization, L.G.-L.; supervision, J.B.-M.; project administration, J.B.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Luis Gonzalez-Lago was employed as Head of Medical at the company Saski Baskonia SAD (Baskonia Alavés Group) at the time of publication. He received no honorarium, compensation, or contractual benefit related to this work. None of his business or academic relationships affected the purpose or scope of this research. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ACL | Anterior cruciate ligament |

| cm | Centimeter |

| ER | External rotation |

| f | Force |

| FAI | Femoroacetabular impingement |

| IR | Internal rotation |

| kg | Kilograms |

| MVIC | Maximal voluntary isometric contraction |

| Nm | Newton meters |

| OA | Osteoarthritis |

| PFP | Patellofemoral pain |

| PICOS | Participants, intervention, comparisons, outcomes, and study design framework |

| RCT | Randomized controlled trial |

| ROM | Range of motion |

References

- Mosler, A.B.; Crossley, K.M.; Thorborg, K.; Whiteley, R.J.; Weir, A.; Serner, A.; Hölmich, P. Hip strength and range of motion: Normal values from a professional football league. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2016, 20, 339–343. [Google Scholar]

- Dallinga, J.M.; Benjaminse, A.; Lemmink, K.A.P.M. Which screening tools can predict injury to the lower extremities in team sports?: A systematic review. Sports Med. 2012, 42, 791–815. [Google Scholar]

- Kolasinski, S.L.; Neogi, T.; Hochberg, M.C.; Oatis, C.; Guyatt, G.; Block, J.; Callahan, L.; Copenhaver, C.; Dodge, C.; Felson, D.; et al. 2019 American College of Rheumatology/Arthritis Foundation Guideline for the Management of Osteoarthritis of the Hand, Hip, and Knee. Arthritis Care Res. 2020, 72, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacharias, A.; Pizzari, T.; English, D.J.; Kapakoulakis, T.; Green, R.A. Hip abductor muscle volume in hip osteoarthritis and matched controls. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2016, 24, 1727–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judd, D.L.; Thomas, A.C.; Dayton, M.R.; Stevens-Lapsley, J.E. Strength and functional deficits in individuals with hip osteoarthritis compared to healthy, older adults. Disabil. Rehabil. 2014, 36, 307–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, A.; Constantinou, M.; Diamond, L.E.; Beck, B.; Barrett, R. Individuals with mild-to-moderate hip osteoarthritis have lower limb muscle strength and volume deficits. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2018, 19, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tak, I.; Engelaar, L.; Gouttebarge, V.; Barendrecht, M.; Van Den Heuvel, S.; Kerkhoffs, G.; Langhout, R.; Stubbe, J.; Weir, A. Is lower hip range of motion a risk factor for groin pain in athletes? A systematic review with clinical applications. Br. J. Sports Med. 2017, 51, 1611–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finnoff, J.T.; Hall, M.M.; Kyle, K.; Krause, D.A.; Lai, J.; Smith, J. Hip Strength and Knee Pain in High School Runners: A Prospective Study. Am. Acad. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2011, 3, 792–801. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, N.J.; Eyles, J.P.; Hunter, D.J. Hip Osteoarthritis: Etiopathogenesis and Implications for Management. Adv. Ther. 2016, 33, 1921–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Más Martínez, J.; Morales-Santías, M.; Bustamante Suarez Suarez de Puga, D.; Sanz-Reig, J. La cirugía artroscópica de cadera en deportistas varones menores de 40 años con choque femoroacetabular: Resultado a corto plazo. Rev. Esp. Cir. Ortop. Traumatol. 2014, 58, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Read, P.J.; Oliver, J.L.; De Ste Croix, M.B.A.; Myer, G.D.; Lloyd, R.S. Neuromuscular Risk Factors for Knee and Ankle Ligament Injuries in Male Youth Soccer Players. Sports Med. 2016, 46, 1059–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maestro, A.; Lago, J.; Revuelta, G.; Del Fueyo, P.; Del Pozo, L.; Ayan, C.; Martin, V. Analysis of hip strength and mobility as injury risk factors in amateur women’s soccer: A pilot study, Analisis de la fuerza y movilidad de la cadera como factores de riesgo de lesión en fútbol femenino amateur: Un estudio piloto. Arch. De Med. Del Deporte 2017, 34, 25–29. [Google Scholar]

- D’Onofrio, R.; Perna, P.; Pompa, D.; Civitillo, C.; Sannicandro, I.; Manzi, V. Asymmetry, lumbo-pelvic hip complex and injury in european soccer players. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fit. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Morton, N.A. The PEDro scale is a valid measure of the methodological quality of clinical trials: A demographic study. Aust. J. Physiother. 2009, 55, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, D.A. Kinetics: Forces and Moments of Force. In Biomechanics and Motor Control of Human Movement; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009; pp. 107–138. [Google Scholar]

- Haddaway, N.R.; Page, M.J.; Pritchard, C.C.; McGuinness, L.A. PRISMA2020: An R package and Shiny app for producing PRISMA 2020-compliant flow diagrams, with interactivity for optimised digital transparency and Open Synthesis. Campbell Syst. Rev. 2022, 18, e1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocarino, J.M.; Resende, R.A.; Bittencourt, N.F.N.; Correa, R.V.A.; Mendonça, L.M.; Reis, G.F.; Souza, T.R.; Fonseca, S.T. Normative data for hip strength, flexibility and stiffness in male soccer athletes and effect of age and limb dominance. Phys. Ther. Sport 2021, 47, 53–58. [Google Scholar]

- Nevin, F.; Delahunt, E. Adductor squeeze test values and hip joint range of motion in Gaelic football athletes with longstanding groin pain. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2014, 17, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Valenciano, A.; Ayala, F.; Vera-García, F.J.; Ste Croix Mde Hernández-Sánchez, S.; Ruiz-Pérez, I.; Cejudo, A.; Santonja, F. Comprehensive profile of hip, knee and ankle ranges of motion in professional football players. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fit. 2019, 59, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tak, I.J.R.; Langhout, R.F.H.; Groters, S.; Weir, A.; Stubbe, J.H.; Kerkhoffs, G.M.M.J. A new clinical test for measurement of lower limb specific range of motion in football players: Design, reliability and reference findings in non-injured players and those with long-standing adductor-related groin pain. Phys. Ther. Sport 2017, 23, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanabe, T.; Watabu, T.; Miaki, H.; Kubo, N.; Pleiades, T.I.; Sugano, T.; Mizuno, K. Association Between Nondominant Leg-Side Hip Internal Rotation Restriction and Low Back Pain in Male Elite High School Soft Tennis Players. J. Sport Rehabil. 2023, 32, 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manning, C.; Hudson, Z. Comparison of hip joint range of motion in professional youth and senior team footballers with age-matched controls: An indication of early degenerative change? Phys. Ther. Sport 2009, 10, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espí-López, G.V.; López-Martínez, S.; Inglés, M.; Serra-Añó, P.; Aguilar-Rodríguez, M. Effect of manual therapy versus proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation in dynamic balance, mobility and flexibility in field hockey players. A randomized controlled trial. Phys. Ther. Sport 2018, 32, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siwecka, G.; Wodka-Natkaniec, E.; Niedzwiedzki, L.; Switon, A.; Niedzwiedzki, T. Relationship between the hip range of motion and functional motor system movement patterns in football players. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fit. 2022, 62, 904–909. [Google Scholar]

- Girdwood, M.; Mentiplay, B.F.; Scholes, M.J.; Heerey, J.J.; Crossley, K.M.; O’Brien, M.J.M.; Perraton, Z.; Shawdon, A.; Kemp, J.L. Hip Muscle Strength, Range of Motion, and Functional Performance in Young Elite Male Australian Football Players. J. Sport. Rehabil. 2023, 32, 910–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoglund, L.T.; Wong, A.L.K.; Rickards, C. The impact of sagittal plane hip position on isometric force of hip external rotator and internal rotator muscles in healthy young adults. Int. J. Sports Phys. Ther. 2014, 9, 58–67. [Google Scholar]

- Ferber, R.; Bolgla, L.; Earl-Boehm, J.E.; Emery, C.; Hamstra-Wright, K. Strengthening of the hip and core versus knee muscles for the treatment of patellofemoral pain: A multicenter randomized controlled trial. J. Athl. Train. 2015, 50, 366–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendonça, L.D.; Ocarino, J.M.; Bittencourt, N.F.N.; Macedo, L.G.; Fonseca, S.T. Association of hip and foot factors with patellar tendinopathy (Jumper’s Knee) in Athletes. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2018, 48, 676–684. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.J.; Lee, W.C.; Ng, G.Y.F.; Fu, S.N. Isometric strength of the hip abductors and external rotators in athletes with and without patellar tendinopathy. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2018, 118, 1635–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCann, R.S.; Bolding, B.A.; Terada, M.; Kosik, K.B.; Crossett, I.D.; Gribble, P.A. Isometric hip strength and dynamic stability of individuals with chronic ankle instability. J. Athl. Train. 2018, 53, 672–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, P.W.; Burnham, J.; Yonz, M.; Johnson, D.; Ireland, M.L.; Noehren, B. Hip external rotation strength predicts hop performance after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2018, 26, 1137–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lobo Júnior, P.; Barbosa Neto, I.A.; de Souza Borges, J.H.; Ferreira Tobias, R.; da Silva Boitrago, M.; de Paula Olivera, M. Clinical Muscular Evaluation in Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome. Acta Ortop. Bras. 2018, 26, 91–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delp, S.L.; Hess, W.E.; Hungerford, D.S.; Jones, L.C. Variation of rotation moment arms with hip flexion. J. Biomech. 1999, 32, 493–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langhout, R.; Tak, I.; Van Der Westen, R.; Lenssen, T. Range of motion of body segments is larger during the maximal instep kick than during the submaximal kick in experienced football players. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fit. 2017, 57, 388–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khayambashi, K.; Ghoddosi, N.; Straub, R.K.; Powers, C.M. Hip Muscle Strength Predicts Noncontact Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury in Male and Female Athletes: A Prospective Study. Am. J. Sports Med. 2016, 44, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Probst, M.M.; Fletcher, R.; Seelig, D.S. A Comparison of Lower-Body Flexibility, Strength, and Knee Stability between Karate Athletes and Active Controls. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2007, 21, 451–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peduzzi de Castro, M.; de Brito Fontana, H.; Fóes, M.C.; Santos, G.M.; Ruschel, C.; Roesler, H. Activation of the gluteus maximus, gluteus medius and tensor fascia lata muscles during hip internal and external rotation exercises at three hip flexion postures. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 2021, 27, 487–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).