An Exploration of U.S. Nutritional Diet Policies: A Narrative Review for Transformation Toward Sustainable Food Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

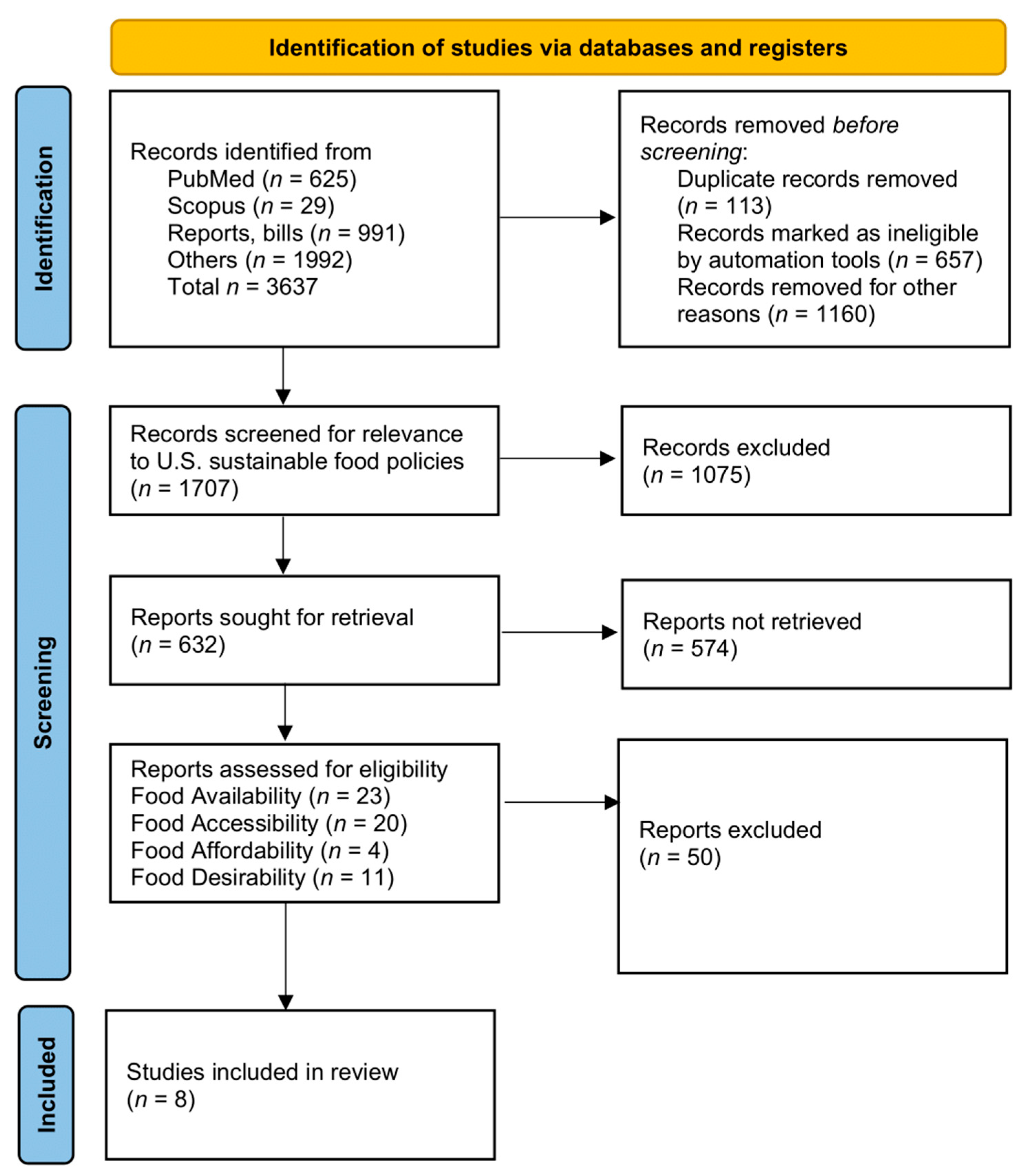

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

Aim and Research Questions

- (1)

- What federal policies currently exist in the U.S. that address sustainable food availability, accessibility, affordability, and desirability?

- (2)

- To what extent have these policies incorporated both public health and environmental sustainability?

- (3)

- What are the gaps in existing policy efforts and what recommendations have been proposed in the literature?

2.2. Definitions of Key Food Security Dimensions

2.2.1. Food Availability

2.2.2. Food Accessibility

2.2.3. Food Affordability

2.2.4. Food Desirability

2.3. Search Strategy

2.4. Policy Analysis Review

3. Results

3.1. Food Availability

3.1.1. Sustainable Food Availability Policies in the United States

3.1.2. Recommendations for Sustainable Food Availability Policies

3.2. Food Accessibility

3.2.1. Sustainable Food Accessibility Policies in the United States

3.2.2. Recommendations for Sustainable Food Accessibility Policies

3.3. Food Affordability

3.3.1. Sustainable Food Affordability Policies in the United States

3.3.2. Recommendations for Sustainable Food Affordability Policies

3.4. Food Desirability

3.4.1. Sustainable Food Desirability Policies in the United States

3.4.2. Recommendations for Sustainable Food Desirability Policies

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications

- Guaranteeing human health: Transforming food systems is necessary to ensure that everyone has access to sufficiently nutritious and safe diets. By promoting sustainable, healthy diets, food systems can contribute to improving people’s health and well-being.

- Ensuring environmental health: Current food systems, including deforestation, greenhouse gas emissions, and water pollution, have significant impacts on the environment. The transformation of food systems can help mitigate these negative environmental impacts and promote sustainability.

- Addressing food security: With the world’s population expected to reach over 10 billion people by 2050, it is crucial to transform food systems to ensure food security for everyone. By improving food availability, accessibility, and affordability, sustainable food systems can help meet the growing demand for food.

- Supporting just and equal livelihoods: Transforming food systems involves creating policies that prioritize equitable access to food and support fair livelihoods for those involved in the food production and distribution chain. This can help reduce inequalities and promote social justice within the food system.

- Meeting future challenges: As the world faces challenges such as climate change, resource scarcity, and population growth, transforming food systems has become essential for adapting to these challenges and building resilience. Sustainable food systems can contribute to mitigating the impacts of climate change, conserving resources, and ensuring long-term food security.

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Crippa, M.; Solazzo, E.; Guizzardi, D.; Monforti-Ferrario, F.; Tubiello, F.N.; Leip, A. Food systems are responsible for a third of global anthropogenic GHG emissions. Nat. Food 2021, 2, 198–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willett, W.; Rockström, J.; Loken, B.; Springmann, M.; Lang, T.; Vermeulen, S.; Garnett, T.; Tilman, D.; DeClerck, F.; Wood, A.; et al. Food in the Anthropocene: The EAT–Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Lancet 2019, 393, 447–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanzo, J.; Rudie, C.; Sigman, I.; Grinspoon, S.; Benton, T.G.; Brown, M.E.; Covic, N.; Fitch, K.; Golden, C.D.; Grace, D.; et al. Sustainable food systems and nutrition in the 21st century: A report from the 22nd annual Harvard Nutrition Obesity Symposium. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 115, 18–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Non-Communicable Diseases. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases (accessed on 13 February 2024).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). About Obesity. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/php/about/index.html (accessed on 29 July 2025).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Coronavirus Disease 2019. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/index.htm (accessed on 13 February 2024).

- Burgaz, C.; Gorasso, V.; Achten, W.M.J.; Batis, C.; Castronuovo, L.; Diouf, A.; Asiki, G.; Swinburn, B.A.; Unar-Munguía, M.; Devleesschauwer, B.; et al. The effectiveness of food system policies to improve nutrition, nutrition-related inequalities and environmental sustainability: A scoping review. Food Secur. 2023, 15, 1313–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fras, Z.; Jakše, B.; Kreft, S.; Malek, Ž.; Kamin, T.; Tavčar, N.; Mis, N.F. The Activities of the Slovenian Strategic Council for Nutrition 2023/24 to Improve the Health of the Slovenian Population and the Sustainability of Food: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swinburn, B.A.; Kraak, V.I.; Allender, S.; Atkins, V.J.; Baker, P.I.; Bogard, J.R.; Brinsdenh, H.; Calvilloi, A.; Schutter, O.D.; Devarajan, R.; et al. The Global Syndemic of Obesity, Undernutrition, and Climate Change: The Lancet Commission report. Lancet Br. Ed. 2019, 393, 791–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). The Future of Food and Agriculture—Trends and Challenges. Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/2e90c833-8e84-46f2-a675-ea2d7afa4e24/content (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- US Department of Agriculture (USDA). Key Statistics & Graphics. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-u-s/key-statistics-graphics/ (accessed on 13 February 2024).

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Sustainable Healthy Diets: Guiding principles. Available online: https://www.fao.org/documents/card/en/c/ca6640en (accessed on 14 February 2024).

- Grosso, G.; Mateo, A.; Rangelov, N.; Buzeti, T.; Birt, C. Nutrition in the context of the Sustainable Development Goals. Eur. J. Public Health 2020, 30, i19–i23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozaffarian, D.; Angell, S.Y.; Lang, T.; Rivera, J.A. Role of government policy in nutrition—Barriers to and opportunities for healthier eating. BMJ Online 2018, 361, k2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, S.; Charlesworth, M.; Elrakhawy, M. How to write a narrative review. Anaesthesia 2023, 78, 1162–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridgway, E.; Baker, P.; Woods, J.; Lawrence, M. Historical developments and paradigm shifts in public health nutrition science, guidance, and policy actions: A narrative review. Nutrients 2019, 11, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaney, M.A. So You Want to Write a Narrative Review Article? J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 2021, 35, 3045–3049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Policy Brief: Food Security. Available online: https://www.fao.org/fileadmin/templates/faoitaly/documents/pdf/pdf_Food_Security_Cocept_Note.pdf (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- US Department of Agriculture (USDA). Healthy Food Access. Available online: https://www.usda.gov/sites/default/files/documents/7-Healthyfoodaccess.pdf (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Cafer, A.; Mann, G.; Ramachandran, S.; Kaiser, M. National Food Affordability: A County-Level Analysis. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2018, 15, 180079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Byker Shanks, C.; Smith, T.; Shanks, J. Fruit and Vegetable Desirability Is Lower in More Rural Built Food Environments of Montana, USA Using the Produce Desirability (ProDes) Tool. Food Secur. 2018, 10, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo, R.; Li, Y.; Chong, S.; Siscovick, D.; Trinh-Shevrin, C.; Yi, S. Dietary policies and programs in the United States: A narrative review. Prev. Med. Rep. 2020, 19, 101135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Policy Research. Available online: https://catalyst.harvard.edu/community-engagement/policy-research/ (accessed on 16 February 2024).

- Love, D.C.; Pinto da Silva, P.; Olson, J.; Fry, J.P.; Clay, P.M. Fisheries, food, and health in the USA: The importance of aligning fisheries and health policies. Agric. Food Secur. 2017, 6, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, M.; Tagtow, A.; Roberts, S.L.; MacDougall, E. Aligning Food Systems Policies to Advance Public Health. J. Hunger Environ. Nutr. 2009, 4, 225–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serafim, P.; Borges, C.A.; Cabral-Miranda, W.; Jaime, P.C. Ultra-Processed Food Availability and Sociodemographic Associated Factors in a Brazilian Municipality. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 858089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymundo Jr, A. Archiving Food Heritage Towards Championing Food Security: A Case Study of Lokalpedia. WIMAYA 2024, 5, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullan, B.; Ntoumanis, N.; Thøgersen-Ntoumani, C.; Lipp, O.V. “It’s a Bit More Complicated than That”: A Broader Perspective on Determinants of Obesity. Behav. Brain Sci. 2017, 40, e124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortin, K.; Harvey, S.; Swearingen White, S. Hidden Hunger: Understanding the Complexity of Food Insecurity Among College Students. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2021, 40, 242–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, K.L.; Kim, B.F.; McKenzie, S.E.; Lawrence, R.S. Food System Policy, Public Health, and Human Rights in the United States. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2015, 36, 151–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conceição, P.; Levine, S.; Lipton, M.; Warren-Rodríguez, A. Toward a food secure future: Ensuring food security for sustainable human development in Sub-Saharan Africa. Food Policy 2016, 60, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, R.A.; Merrigan, K.; Wallinga, D. A food systems approach to healthy food and agriculture policy. Health Aff. 2015, 34, 1908–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen Markey, E.J. D M. Text—S.3390—118th Congress (2023–2024): EFFECTIVE Food Procurement Act. Available online: https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/senate-bill/3390/text (accessed on 18 February 2024).

- Rep. Adams AS D N 12. Text—H.R.6569—118th Congress (2023–2024): EFFECTIVE Food Procurement Act [Internet]. 2024. Available online: https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/house-bill/6569/text (accessed on 18 February 2024).

- Wilkins, J.L.; Farrell, T.J.; Rangarajan, A. Linking vegetable preferences, health and local food systems through community-supported agriculture. Public Health Nutr. 2015, 18, 2392–2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, E.A.; Nifong, R.L.; Ferguson, R.B.; Palm, C.; Osmond, D.L.; Baron, J.S. Nutrients in the nexus. J. Environ. Stud. Sci. 2016, 6, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.E.; Carcedo, A.J.P.; Eggen, M.; Grace, K.L.; Neff, J.; Ciampitti, I.A. Integrated modeling framework for sustainable agricultural intensification. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 6, 1039962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wunderlich, S.; Gatto, K.A. Consumers’ food choices and the role of perceived environmental impact. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2016, 11, 989–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Jilcott Pitts, S.B.; Wu, Q.; Demarest, C.L.; Dixon, C.E.; Dortche, C.J.; Bullock, S.L.; McGuirt, J.; Wardet, R.; Ammerman, A.S. Farmers’ market shopping and dietary behaviours among Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program participants. Public Health Nutr. 2015, 18, 2407–2414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenna, P.; Zakaria, F.; Guest, J.; Evans, B.; Banwart, S. Will the circle be unbroken? The climate mitigation and sustainable development given by a circular economy of carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus and water. RSC Sustain. 2023, 1, 960–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thilsted, S.H.; Thorne-Lyman, A.; Webb, P.; Bogard, J.R.; Subasinghe, R.; Phillips, M.J.; Alison, E.H. Sustaining healthy diets: The role of capture fisheries and aquaculture for improving nutrition in the post-2015 era. Food Policy 2016, 61, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagasse, L.P.; Love, D.C.; Smith, K.C. Country-of-Origin Labeling Prior to and at the Point of Purchase: An Exploration of the Information Environment in Baltimore City Grocery Stores. Ecol. Food Nutr. 2014, 53, 58–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, L.; Rudolph, L. Supporting Climate, Health, and Equity under the Farm Bill. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 389, 1541–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muth, M.K.; Birney, C.; Cuéllar, A.; Finn, S.M.; Freeman, M.; Galloway, J.N.; Gee, I.; Gephart, J.; Jones, K.; Low, L.; et al. A systems approach to assessing environmental and economic effects of food loss and waste interventions in the United States. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 685, 1240–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, M.E.; Hamm, M.W.; Hu, F.B.; Abrams, S.A.; Griffin, T.S. Alignment of Healthy Dietary Patterns and Environmental Sustainability: A Systematic Review. Adv. Nutr. 2016, 7, 1005–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reinhardt, S.L.; Boehm, R.; Blackstone, N.T.; El-Abbadi, N.H.; McNally Brandow, J.S.; Taylor, S.F.; DeLonge, M.S. Systematic Review of Dietary Patterns and Sustainability in the United States. Adv. Nutr. 2020, 11, 1016–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swasey, J.H.; Iudicello, S.; Parkes, G.; Trumble, R.; Stevens, K.; Silver, M.; Recchia, C.A. The fisheries governance tool: A practical and accessible approach to evaluating management systems. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0253775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rep. Caraveo Y D C 8. Text—H.R.4060—118th Congress (2023–2024): Food Access and Stability Act of 2023 [Internet]. 2023. Available online: https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/house-bill/4060/text (accessed on 18 February 2024).

- Sen Casey, R.P. Text—S.1036—118th Congress (2023–2024): Senior Hunger Prevention Act of 2023 [Internet]. 2023. Available online: https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/senate-bill/1036/text (accessed on 19 February 2024).

- Sen Booker, C.A.D.N. S.1809—118th Congress (2023–2024): Office of Small Farms Establishment Act of 2023 [Internet]. 2023. Available online: https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/senate-bill/1809 (accessed on 19 February 2024).

- Rep. Strickland M D W 10. H.R.3877—118th Congress (2023–2024): Office of Small Farms Establishment Act of 2023 [Internet]. 2023. Available online: https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/house-bill/3877 (accessed on 19 February 2024).

- Rep. Bonamici S D O 1. H.R.3951—118th Congress (2023–2024): Sustaining Healthy Ecosystems, Livelihoods, and Local Seafood Act [Internet]. 2023. Available online: https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/house-bill/3951 (accessed on 19 February 2024).

- Sen Whitehouse, S.D.R. S.2211—118th Congress (2023–2024): Sustaining Healthy Ecosystems, Livelihoods, and Local Seafood Act [Internet]. 2023. Available online: https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/senate-bill/2211 (accessed on 19 February 2024).

- Sen Warner, M.R.D.V. S.203—117th Congress (2021–2022): Healthy Food Access for All Americans Act [Internet]. 2021. Available online: https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/senate-bill/203 (accessed on 19 February 2024).

- Rep. Ryan T D O 13. H.R.1313—117th Congress (2021–2022): Healthy Food Access for All Americans Act [Internet]. 2021. Available online: https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/1313 (accessed on 19 February 2024).

- Rep. Lucas FD R O 3. H.R.2642—113th Congress (2013–2014): Agricultural Act of 2014 [Internet]. 2014. Available online: https://www.congress.gov/bill/113th-congress/house-bill/2642 (accessed on 19 February 2024).

- Rep. Conaway KM R T 11. H.R.2—115th Congress (2017–2018): Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018 [Internet]. 2018. Available online: https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/house-bill/2 (accessed on 18 February 2024).

- Freudenberg, N.; Nestle, M. A call for a national agenda for a healthy, equitable, and sustainable food system. Am. J. Public Health 2020, 110, 1671–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sen Blumenthal, R.D.C. Text—S.2342—113th Congress (2013–2014): Stop Subsidizing Childhood Obesity Act [Internet]. 2014. Available online: https://www.congress.gov/bill/113th-congress/senate-bill/2342/text (accessed on 18 February 2024).

- Rep. DeLauro RL D C 3. H.R.5232—114th Congress (2015–2016): Stop Subsidizing Childhood Obesity Act [Internet]. 2016. Available online: https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/house-bill/5232 (accessed on 18 February 2024).

- Sen Blumenthal, R.D.C. S.2936—114th Congress (2015–2016): Stop Subsidizing Childhood Obesity Act [Internet]. 2016. Available online: https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/senate-bill/2936 (accessed on 18 February 2024).

- Rep. DeLauro RL D C 3. Actions—H.R.9299—117th Congress (2021–2022): Stop Subsidizing Childhood Obesity Act [Internet]. 2022. Available online: https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/9299/actions (accessed on 18 February 2024).

- Sen Blumenthal, R.D.C. S.5086—117th Congress (2021–2022): Stop Subsidizing Childhood Obesity Act of 2022 [Internet]. 2022. Available online: https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/senate-bill/5086 (accessed on 18 February 2024).

- Rep. DeLauro RL D C 3. H.R.7342—115th Congress (2017–2018): Stop Subsidizing Childhood Obesity Act [Internet]. 2018. Available online: https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/house-bill/7342 (accessed on 18 February 2024).

- Rep. Cartwright M D P 17. Text—H.R.3800—114th Congress (2015–2016): Nutrition Education Act [Internet]. 2016. Available online: https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/house-bill/3800/text (accessed on 18 February 2024).

- Rep. Cartwright M D P 17. H.R.3323—115th Congress (2017–2018): Nutrition Education Act [Internet]. 2017. Available online: https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/house-bill/3323 (accessed on 18 February 2024).

- Rep. Cartwright M D P 8. H.R.5892—116th Congress (2019–2020): Nutrition Education Act [Internet]. 2020. Available online: https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/5892 (accessed on 18 February 2024).

- Rep. Cartwright M D P 8. H.R.5308—117th Congress (2021–2022): Nutrition Education Act [Internet]. 2021. Available online: https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/5308 (accessed on 18 February 2024).

- Kusumawardani, A.; Laksmono, B.S.; Setyawati, L.; Soesilo, T.E.B. A Policy Construction for Sustainable Rice Food Sovereignty in Indonesia. Slovak J. Food Sci. Potravin. 2021, 15, 484–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaharia, A.; Diaconeasa, M.-C.; Maehle, N.; Szolnoki, G.; Capitello, R. Developing Sustainable Food Systems in Europe: National Policies and Stakeholder Perspectives in a Four-Country Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mensah, K.; Wieck, C.; Rudloff, B. Sustainable Food Consumption and Sustainable Development Goal 12, Conceptual Challenges for Monitoring and Implementation. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 32, 1109–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobi, J.; Mukhovi, S.; Llanque, A.; Giger, M.; Bessa, A.; Golay, C.; Ifejika Speranza, C.; Mwangi, V.; Augstburger, H.; Buergi-Bonanomi, E.; et al. A New Understanding and Evaluation of Food Sustainability in Six Different Food Systems in Kenya and Bolivia. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 19145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, M.A.; Friel, S.; Wingrove, K.; James, S.W.; Candy, S. Formulating Policy Activities to Promote Healthy and Sustainable Diets. Public Health Nutr. 2015, 18, 2333–2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbour, L.; Lindberg, R.; Woods, J.; Charlton, K.; Brimblecombe, J. Local Urban Government Policies to Facilitate Healthy and Environmentally Sustainable Diet-Related Practices: A Scoping Review. Public Health Nutr. 2021, 25, 471–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrad, A.; Aguirre-Bielschowsky, I.; Reeve, B.; Rose, N.; Charlton, K. Australian Local Government Policies on Creating a Healthy, Sustainable, and Equitable Food System: Analysis in New South Wales and Victoria. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2022, 46, 332–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deaconu, E.-M.; Pătărlăgeanu, S.R.; Petrescu, I.-E.; Dinu, M.; Sandu, A. An Outline of the Links between the Sustainable Development Goals and the Transformative Elements of Formulating a Fair Agri-Food Trade Policy—A Measurable EU Achievement. Proc. Int. Conf. Bus. Excell. 2023, 17, 1449–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garske, B.; Heyl, K.; Ekardt, F.; Weber, L.; Gradzka, W. Challenges of Food Waste Governance: An Assessment of European Legislation on Food Waste and Recommendations for Improvement by Economic Instruments. Land 2020, 9, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omuemu, V.O. COVID-19 Pandemic and Its Implication for Nutritional Status of Children in Nigeria: A Call for Transformation to a Sustainable Food System. J. Com. Med. PHC 2022, 34, 12–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Policy Feature | International Models (e.g., EU, Brazil, Canada) | U.S. Policies |

|---|---|---|

| Policy Framework | Comprehensive national strategies (e.g., EU Farm to Fork) | Fragmented programs across USDA, FDA, and state/local agencies |

| Primary Objectives | Improve health, reduce environmental footprint, ensure food sovereignty | Improve access and affordability, limited focus on sustainability |

| Implementation Strategy | Top-down plus community-led pilots | Program-specific interventions (e.g., SNAP, school meals) |

| Governance Level | National and regional coordination | Federal, with state variation |

| Monitoring and Evaluation | Structured metrics, annual reports, SDG alignment | Inconsistent or absent outcome tracking |

| Integration of Environmental Goals | Strong integration with climate and biodiversity goals | Often limited or indirect integration |

| Stakeholder Engagement | Multi-stakeholder forums, civil society involvement | Primarily agency-driven with limited community input |

| Policy Name | Year of Enactment | Target Population | Policy Goals | Level of Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agricultural Act (Farm Bill) | 2014, 2018 | Farmers, low-income families | Support agriculture, conservation, nutrition assistance | Federal |

| Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) | Ongoing | Low-income individuals and families | Improve food access through financial assistance | Federal |

| Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act | 2010 | School-aged children | Improve school meal nutrition standards | Federal with local implementation |

| EFFECTIVE Food Procurement Act (proposed) | 2023 (Senate), 2024 (House) | Federal food procurement programs | Promote climate-resilient procurement and sustainability | Federal (proposed) |

| Senior Hunger Prevention Act (proposed) | 2023 | Older adults and disabled individuals | Streamline nutrition access and reduce senior hunger | Federal (proposed) |

| Food System Transformation Domains | Summary of Policy Recommendations Found in the Literature |

|---|---|

| Food availability [30,35,36,38,43] |

|

| Food accessibility [30,38,39] |

|

| Food affordability [30,39,42] |

|

| Food desirability [30,58] |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gonzalez-Alvarez, A.D.; Awan, A.T.; Sharma, M. An Exploration of U.S. Nutritional Diet Policies: A Narrative Review for Transformation Toward Sustainable Food Systems. Encyclopedia 2025, 5, 114. https://doi.org/10.3390/encyclopedia5030114

Gonzalez-Alvarez AD, Awan AT, Sharma M. An Exploration of U.S. Nutritional Diet Policies: A Narrative Review for Transformation Toward Sustainable Food Systems. Encyclopedia. 2025; 5(3):114. https://doi.org/10.3390/encyclopedia5030114

Chicago/Turabian StyleGonzalez-Alvarez, Ana Daniela, Asma Tahir Awan, and Manoj Sharma. 2025. "An Exploration of U.S. Nutritional Diet Policies: A Narrative Review for Transformation Toward Sustainable Food Systems" Encyclopedia 5, no. 3: 114. https://doi.org/10.3390/encyclopedia5030114

APA StyleGonzalez-Alvarez, A. D., Awan, A. T., & Sharma, M. (2025). An Exploration of U.S. Nutritional Diet Policies: A Narrative Review for Transformation Toward Sustainable Food Systems. Encyclopedia, 5(3), 114. https://doi.org/10.3390/encyclopedia5030114