3.1. The Long, Hard Post-War Period: Intervention or Housing Market? (1939–1959)

In many European countries, the first significant responses to the housing problem were made at the end of the nineteenth century and during the inter-war period. However, in general, political choices in the immediate post-war period were decisive. In Spain, with little history of housing policy, the twenty years following the end of the Civil War (1936–1939), which had contradictory, ineffective policies and worse than mediocre results—at the antipodes of the welfare state policies of other European countries—were critical and determinant for subsequent developments: the number of interventions was minimal and restricted to specific locations; no public housing stock was created, nor were mechanisms activated for an affordable rental market [

18].

In his studies of urban morphology, Whitehand found that as building cycles develop, moments of crisis can shape subsequent urban expansions [

19]. In the Spanish case, twenty years of a desperate post-war crisis seem to have left long-lasting structural traces. This period shaped subsequent housing policies and dynamics marked by the promotion of horizontal property. It could be argued that the failure of the 1939–1959 period led to high homeownership rates from the 1960s and a clear, unexpected concentration of homeownership in the working-class suburbs. These two factors have characterized Spain since the developmentalist period (1960–1975) or desarrollismo.

The commitment to homeownership was certainly not new. It had been developing since the end of the nineteenth century and had been supported by the Church’s social doctrine, at least since the Rerum Novarum, which considered private property to be a key element in the social question. In contrast to the left’s slogans in favor of property suppression, the conservative response understood it as a right anchored in human nature itself and the key to social stability. The way forward was not to abolish property but to increase it.

In France, in 1894, the state launched real estate loans for the working classes. The archives of the Société Central de Crédit Immobilier (SCCI) made possible the study of the first steps in twentieth century policies in favor of homeownership for popular segments that have a certain capacity to save [

20]. In the inter-war period, the active homeownership policies of Italian Fascism and Salazar’s Estado Novo, aimed mainly at the lower middle or skilled working classes—the social base of their regimes—took center stage [

21,

22,

23,

24].

A recent publication highlighted the decisive influence of Falangist ideas in favor of homeownership in Spain in the first twenty years after the Civil War [

14]. This thesis seems to be corroborated by the fact that housing policy was, in fact, in the hands of Falangist hierarchs. As early as the 1939 Law on Protected Housing (Ley de Vivienda Protegida), the desire to promote homeownership as a formula for social pacification and social integration was clearly expressed, associated with the conservative, stable character of the traditional home. The authors show that the period culminated in the creation of the new Ministry of Housing (Ministerio de la Vivienda). The head of this ministry from 1957 to 1960, the Falangist ideologist José Luis Arrese, spread the slogan: “we want a Spain of owners and not proletarians” (“No queremos una España de proletarios sino de propietarios”). The comparison with the Italian case calls for reflection. There, fascism was not the main driving force behind homeownership. Instead, it was post-war Christian democracy that constructed the most coherent discourse and the most consistent, effective action in defense of homeownership. The formula “non ‘tutti proletari’ ma ‘tutti proprietari’” is from 1946 and sums up the position of Italian Christian democracy led by Amintore Fanfani, which makes Arrese a late epigone [

1].

In contrast to the scale and effectiveness of the INACasa Plan in Italy (1949–1963), the Obra Sindical del Hogar (OSH), set up in 1939 with the mission of solving the housing problem through the construction and public administration of affordable housing, shows the gap between Falangist-inspired discourse and deeds. Between 1942 and 1953, only 21,737 dwellings had been delivered when, in a very optimistic calculation, the 1952 Architects’ Congress had estimated a deficit of 800,000 dwellings [

25]. In short, the OSH, the Instituto Nacional de la Vivienda, and the Patronatos Municipales de la Vivienda were practically irrelevant in terms of alleviating the serious problem of affordable rental housing.

The failed post-war economic policy and a housing policy aimed at alleviating unemployment, which in fact neglected the “producing class”, led to an extremely critical situation for the weaker sections of the population. In this context, the regulation of urban rents worsened the situation. The first regulations had been introduced in the 1920s, in response to the intense inflationary process during the first European post-war period and the social tensions that characterized those years. The Royal Decree of 21 June 1920 regulated the forced extension of urban leases and the limitation of rent updates—both with the intention of protecting the tenant against the landlord. The Royal Decree contained updates in 1925 and 1931 that did not modify substantial aspects of this regulation, but which must have consolidated the progressive weakening of landlords’ expectations and the lamination of the supply of rented housing. Already in 1945, an article presented what is known as “horizontal property” (condominiums) as a long-term alternative to mobilize private savings, and it was noted that it was beginning to make progress in Zaragoza, Valencia, and Madrid [

26].

Faced with rising prices and the growing gap between salaries and housing costs, the approval of the Law on Urban Rental Contracts in 1946 insisted on regulating forced extensions with more extensive articles that recognized exceptions and special situations and maintained the protection of the tenant against the landlord. These reactive regulations drove up new housing rents, penalizing residential landlords and deterring fresh investment in the sector. Ultimately, the rent freeze and high inflation significantly worsened the housing problem by undermining the viability of rental properties.

In these years, the housing problem in major cities worsened rapidly, driven by resumed migration from rural areas experiencing misery, political repression, and limited opportunities. The resulting supply bottleneck fueled the proliferation of shantytowns, self-help housing, and cohabitation. Concurrently, a significant informal housing sub-market developed, comprising self-help neighborhoods where residents acquired minuscule land plots and constructed dwellings illicitly.

The constant decline of living conditions, amidst widespread ineffectiveness, rationing, and a black market, triggered the greatest explosion of social unrest in the early Franco regime. The misnamed 1951 Barcelona “tram strike”—actually a user boycott that escalated into a full general strike—served as a crucial wake-up call for the regime, despite harsh repression. The 1951 government restructuring brought in ministers more open to economic liberalization, and by May 1952 rationing had officially ended. This tacit acceptance of autarchy’s failure coincided with the recognition of the housing problem as the “first national problem”. In 1954, as part of the Second Housing Plan, a new law on “limited rent” housing offered builders significant incentives: tax exemptions, bonuses, priority material supply, subsidies, and credits. This marked a complete redefinition of the private social housing regime. Other complementary liberalizing measures, such as the 1956 Land Law, were less effective but provided some tools to expand the supply of urban land. However, updates to the urban renting law in 1956 and 1964 maintained compulsory extensions and subrogation possibilities for tenancy contracts upon death. These tenant guarantees ultimately contributed to the irreversible erosion of the rental housing market.

The case of Barcelona can illustrate the evolution of public intervention during the first twenty years of Franco’s regime. Despite the interventionist rhetoric, between 1939 and 1949 only two residential estates were built, with a total of 536 dwellings (barely 4% of the total number of new dwellings). Between 1950 and 1959, public actions were more decisive and sixteen housing estates were built with a total of 18,560 dwellings. During the same period, the population grew by 450,000 inhabitants. These estates accounted for only 32% of all new housing, which indirectly reveals the relative sluggishness of private initiative, despite the battery of measures to stimulate it and the worsening of the housing shortage.

In the decisive government restructuring of 1957, the Ministry of Housing was created, headed by José Luis Arrese, a Falangist with absolute loyalty to Franco as a minister. For J. Candela, the popular slogan No queremos una España de proletarios sino de propietarios (“We don’t want a Spain of proletarians, but of property owners”) and the approval in 1960 of the Law of Horizontal Property (Ley de la Propiedad Horizontal) culminated the Falangist influence on housing policy. However, the previous twenty years of Falangist interventionist policy contradicted this interpretation. All the demands for the development of horizontal property (condominiums), which had been voiced at least since 1945 through the press and the chambers of property (Cámaras de la Propiedad Inmobiliaria), went unheeded. The inaction is surprising if one considers the official will to mobilize the savings of the middle class to activate the economy and mitigate unemployment. It is even more surprising considering the Peronist experience, which was so close to early Francoism. In Argentina, the inflationary process also led to the freezing of rents in 1943. The Peronist regime’s response to the serious housing problem, which included social housing plans and mortgage loans, included the approval of the 1948 Horizontal Property Law. The Argentinian experience was echoed in the Spanish press, but there are no reports of its impact in official spheres.

Ordering the horizontal division of property to erect multistorey apartment buildings was not so much a commitment to an ideal property, a guarantor of the moral order of the home, as was advocated in Falangist and National-Catholic discourses. It was rather an instrument that facilitated alienation and stimulated the private property market. Everything seems to indicate that the interventionism of the regime was still wary of the market. Given these precedents, Arrese’s actions as head of the new Ministry of Housing, once he had been “banished” from the leadership of the Movement (Movimiento Nacional), were not a genuinely Falangist expression. Rather, they may demonstrate his capacity for verbalization and propaganda to defend the new economic liberalization that the Opus Dei technocrats were imposing.

In 1959, the delegates of the Obra Sindical del Hogar themselves, harassed by users’ complaints, saw horizontal property as a way of transferring to users the high maintenance costs of very poorly constructed housing estates. The beneficiaries were not mere tenants, “but owners, and they felt the need to root this conception in a public deed and in the obligation (due to the mortgage guarantee in force) to impose, at the owner’s expense, all those ordinary and extraordinary works required for the upkeep of the dwelling” [

24]. This transfer was the source of many conflicts and took decades to materialize.

If, at the end of Franco’s regime (1975), the high homeownership rates in working-class peripheries seem to confirm the success of José Luis Arrese’s slogan, they were neither properly the result of Falangist ideology, nor an expression of social justice, nor did they have the expected effect of social pacification.

3.2. ”Desarrollismo”: Horizontal Property and Working-Class Homeownership (1960–1975)

After twenty years of paralysis, the second period of the Franco regime resumed the process of modernization. Although immigration continued, strong and sustained economic growth and the boost to housebuilding gradually began to mitigate the very serious housing shortage that had characterized the previous period. In the case of Barcelona, a comparison between the number of dwellings built and population increases in five-year periods clearly shows the inflexion of the 1960s (

Figure 2).

The graphics reflect the vigorous expansion of the traditional building industry driven by demand, state support, and easy financial payment terms. Although initially based on the availability of abundant cheap labor due to the relative backwardness of the building sector, its structural change during this expansionary cycle is indisputable. Materials were standardized, processes were mechanized, and there were substantial increases in productivity. The rapid expansion of horizontal property allowed for a faster turnover of capital and, together with the change in the economic climate, contributed to an unprecedented rise in private initiative. In times of very high inflation rates, buying an apartment on credit was the main source of savings for the weaker economies, to an even greater extent than for more affluent economies. Real estate agencies, developers, and managers with great financial capacity (sometimes linked to banks) were formed. Although the new promoters gradually displaced small ones, our study of Nou Barris still shows an abundance of small promoters who acted fundamentally to replace single-family ground-floor dwellings with multistorey apartment buildings, in processes of densification of the existing low-rise built fabric [

28]. Thus, there was still a certain atomization of supply.

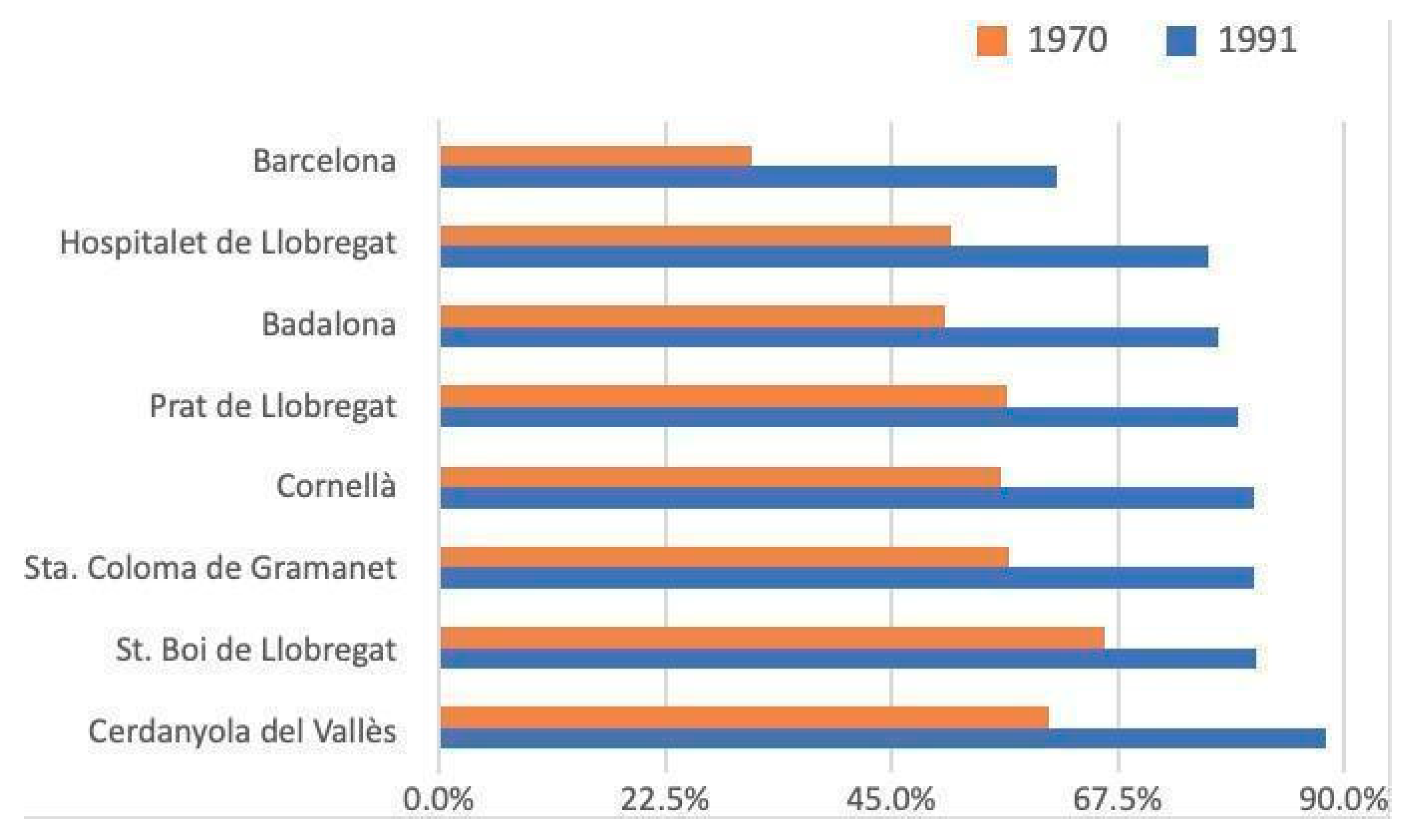

The study of housing censuses of the National Institute of Statistics (Instituto Nacional de Estadística: INE) from Franco’s regime to the early years of democracy shows the radical shift from renting to ownership and the pioneering role of working-class peripheries. In 1950, only 5.2% of Barcelona homes were owned by heads of households, a situation close to the 6.7% of 1930 [

29]. In 1960, when cohabitation, overcrowding, and self-help building were at their highest levels of the century, homeownership represented only 11.2% compared to an overwhelming 84.4% renting (INE data from 1962). This percentage tripled in 1970 to a significant 34.2%: 18.5% were still paying for their homes and 15.7% had already finished paying (INE data from 1976). The 1981 housing census confirms the great change in the city of Barcelona: 52% of households in the city were already owned, compared to 46% rented (INE data from 1981).

This increase in property ownership has a paradoxical social bias: the new suburban working-class neighborhoods were the real Trojan horse of homeownership in the city [

30]. In 1970, when homeownership in Barcelona stood at the aforementioned 34.2%, the large suburban districts 9 and 10—with their more working-class character and greater urban growth—showed percentages of around 44%. These high rates of house ownership in 1970 were mainly associated with new property. The new suburban housing estates and the four- or five-story apartment buildings that massively replaced the old low-rise family houses in the 1960s and early 1970s housed all the families who were religiously paying installments on their new flats. However, the recently developed but higher-economic-status districts 3 and 11 had much lower ownership percentages, below 30% (29% and 22%). There, many of the housing developments were rented and benefited from some form of protection. This was much more difficult to find in the economically weaker districts. The correlation between social class and property ownership in Barcelona in 1970 clearly illustrates the dramatic increase in homeownership among the working class during the 1960s. While 52% of the population was working class and 11.8% wealthy, the correlation for the wealthy was negative (−0.26). In contrast, the working class showed a clear positive correlation (+0.32), rising to +0.39 in the five peripheral districts. Furthermore, district-level data from 1965 to 1970 reveal that the working-class homeownership rate (0.37 correlation) surpassed the city average (0.25). The socio-professional and property maps by administrative districts in 1970 show how the most working-class and immigrant neighborhoods and administrative districts of the city were leading in terms of house ownership. The more affluent neighborhoods, with a higher percentage of managers, liberal professions, and technicians, were those with the lowest percentages of homeownership (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4).

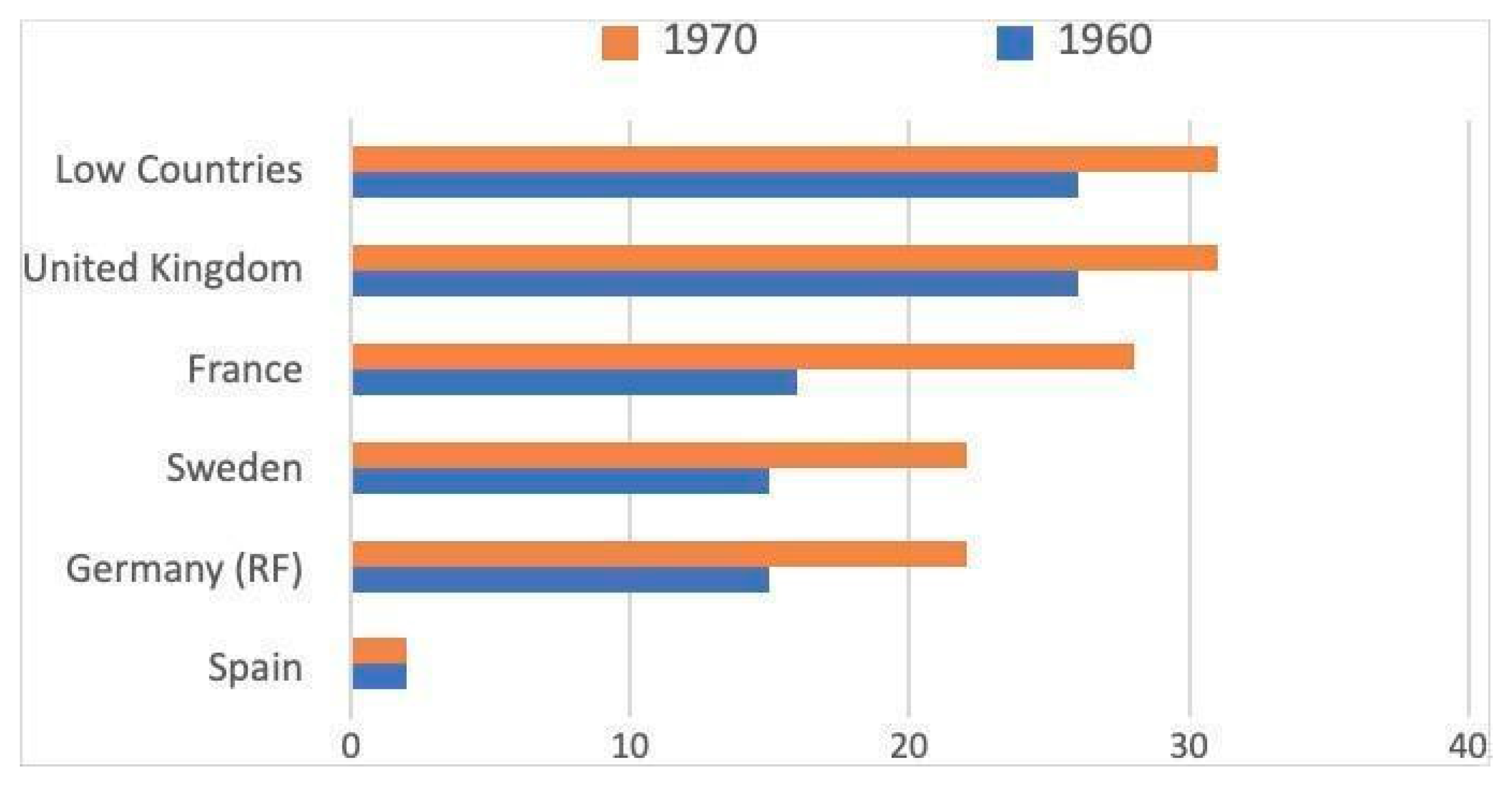

The data on the municipalities in the metropolitan working-class belt further reinforce this association between peripheral working-class neighborhoods and property and should be interpreted in terms of total continuity with that of the large working-class districts and neighborhoods on the outskirts of Barcelona. In 1960, the proportion of the working-class population in these municipalities clearly exceeded that of Barcelona (in Barcelona, the proportion of the working-class population was around 60%, whereas in the municipalities closest to Barcelona, such as L’Hospitalet, Cornellà, Badalona, Santa Coloma, and Sant Adrià del Besòs, it was well over 80%; INE, 1962). From a much more modest housing stock, with more severe overcrowding conditions than in Barcelona and already high rates of ownership in 1950, the 1960s saw rates of between 57% and 65% of ownership of housing units. Within a tax system of a clearly regressive nature, housing policy led the weaker social sectors to subsidize higher-income families. Official protection in housing paradoxically favored the construction of rental housing for the wealthy, while economically weaker classes were compelled to enter the property market, incurring significant additional effort [

33]. This extremely unfair situation was complemented by a chronic shortage of social rented housing compared to other European countries (

Figure 5).

During these years, a substantial part of Barcelona’s housing stock was built, the market was consolidated as the main supplier of housing in Spain, and the structural foundations for subsequent developments were defined to a large extent.

3.3. The Transition to Democracy: Homeownership and Urban Social Movements (1975–1985)

From 1973 onwards, the economic crisis hit the building sector hard and a violent recession began, with cost inflation as the main trigger. In five years, the number of housing starts halved, and the contraction did not stop until 1985. As the economic recession progressed, the rise in housing costs clearly outstripped per capita household income. The relative demographic stabilization, the stagnation of real income, and expectations of improvement deepened the demand crisis, which was aggravated by the tightening of financing conditions, motivated by the liberalization and reorganization of the financial system. To this must be added the ineffectiveness of the new legislative measures on social housing. Under pressure from rising costs, particularly wages, the housing industry underwent a process of rationalization, concentration, and restructuring, with the penetration of large companies from the public works sector and the consolidation of some real estate companies linked to banks [

34].

The unquestionable growth of the housing stock during the extensive construction cycle that began around 1960, in a context of urgency and concessions made to development, did not always meet the minimum standards. Long delays occurred in terms of facilities, infrastructure, and street conditions (paving, lighting, etc.). As a result, neighborhood struggles to achieve better housing and neighborhood conditions grew in the uncertain environment of the end of Franco’s regime. Unlike the combative rent strikes that had characterized the inter-war crises, neighborhood movements aimed to consolidate precarious house ownership and improve urban facilities, infrastructure, and street conditions. If we look at the case of Nou Barris, the first to be self-organized were the self-help housing neighborhoods created in the two decades after the war [

35]. Here, the residents, united by the common condition of a property that was still precarious from a legal perspective, with incomplete domestic equipment, organized themselves to build basic infrastructure together, such as sewage systems. Residents of the self-built area of Roquetes Altes, under the leadership of the Jesuit Santiago Thió, took advantage of the summer holidays of 1964 to do just this, as did the neighborhood association (asociación de vecinos) created around the same time in the self-built neighborhood of Ca n’Oriach in Sabadell [

36].

Actively organized, these neighborhoods moved on from the assistance provided by parish and social centers to the strengthening of autonomous neighborhood structures and, finally, to the planning of conflicts, struggles, and collective actions that went beyond the narrow legal framework of Franco’s dictatorship [

37]. The occupations of the Barcelona–Granollers motorway in late 1969 (and again in 1971) by Torre Baró and Vallbona residents, driven by the lack of connection between their historically linked neighborhoods, align with this pattern. This type of collective action ultimately led to the formation of increasingly strong and determined neighborhood associations in numerous peripheral areas. These mobilized in a very radical way against the Barcelona municipality when, between 1969 and 1973, the new urban planning (Planes Parciales) and the reform of major roads such as the Meridiana or the Ronda ring road involved the possible destruction of more than 4000 homes in Nou Barris, which threatened the insecure ownership of the houses. The neighborhood associations demonstrated by blocking the Meridiana road and even invaded the municipal plenary. This situation caused the subsequent fall of several mayors. In the housing estates of the Obra Sindical del Hogar in the metropolitan area, built in the 1950s, the legal insecurity of the confusing regime of deferred ownership was the determining factor in the mobilizations between 1969 and 1973. The house payment strikes are the best example of this type of collective action, which was isolated at first, but later coordinated with other housing estates in the metropolitan area and in Barcelona itself, for example, in Trinitat Nova and Verdum in Nou Barris [

30,

38].

Once basic shelter (stable, equipped with water and electricity, and with legal security) had been resolved, people’s demands concentrated on shortfalls in the extra-domestic sphere. Complaints about the serious lack of school places, nurseries, infrastructure/street conditions, and green spaces also extended to the large private housing estates, with construction company offices in the neighborhood itself, such as Sant Ildefons (originally Ciudad Satélite) in Cornellà from 1969, or Ciutat Meridiana in 1973. Finally, the revision of the Intermunicipal Urban Plan (Plan General Metropolitano de Ordenación Urbana or Plan Comarcal—PGMOU) between 1974 and 1976 offered the opportunity to bring together many of these demands in a very active, organized neighborhood movement [

38]. Looking at the example of Nou Barris, it can be concluded that imperfect housing property, derived from self-help building or from the promotions of the Obra Sindical del Hogar, was at the origin and in the radical nature of many of the neighborhood struggles during the second Franco regime. In the Nou Barris district, this radicalism moved from the more working-class areas with more imperfect, insecure housing property to those with a better economic level and more legal orthodox property. The growing access to homeownership undoubtedly reinforced the horizon of stability and fostered involvement and commitment, not only with the problems of each housing plot. In the face of threats and shortages in these neighborhoods, the increasingly coordinated struggle in defense of collective rights, services, and public space marked the beginning of a new era.

In a period of economic crisis and unemployment, neighborhood struggles acquired considerable prominence in the anti-Franco social and political movements and became a way of accessing citizenship. In this context, access to ownership seemed more of an incentive to struggle and compromise than the instrument of pacification hoped for by Francoism. Perhaps it was an element of moderation, compared to the urban violence that erupted in Europe from the late 1970s onwards, motivated by the mechanisms of social and ethnic segregation and the lack of prospects for a marginalized, disillusioned population. It is also significant to compare the SAAL operations of housing provision for the most underprivileged classes, promoted by the Portuguese revolutionary government of 1974–1976, with the policies of the first democratic municipal governments in Spain, which were clearly focused on the provision of public facilities and spaces. The approval of the PGMOU, conceived at the end of the Francoist period by progressive municipal technical staff, attempted to redirect the inherited urban planning parameters, with a clear reduction in potential population densities according to the regulations, and with land reserves for the necessary provision of public facilities and infrastructures. The housing shortage in Spain had not disappeared. For example, shantytowns still abounded. However, both the municipal technicians and the neighborhood movements, influenced in all likelihood by the high proportion of property owners, focused fundamentally on services, facilities. and collective spaces. They were in tune with the scarcely revolutionary and fundamentally civic dimension of much anti-Francoism.

3.4. The Real Estate Policy of Democracy and the Speculative Bubble (1985–2013)

The mid-1980s saw the beginning of a new expansionary period driven by the incorporation into the then European Economic Community (1986) and the incipient globalization of the Spanish economy. In a period marked by deepening and broadening of liberal postulates, after the Keynesian public demand policies of the immediate post-war period, there was not in fact a simple neoliberal return to pure markets, but rather a market system based on the growth of debt among low- and middle-income people, especially for the acquisition of homeownership, which has been described as “privatized Keynesianism” [

39]. So, although with significant differences between countries, the 1980s were years of reduced public intervention and deregulation in Germany, France, and the UK. At the end of the 1990s, when the liberalizing tendencies in France and Germany were attenuated, the Netherlands entered a clear phase of disintervention [

16].

Paradoxically, the welfare state model was adopted in Spain just when its gradual dismantling in Europe was beginning and when the widespread adoption of homeownership was considered a success story. In this context, the Boyer Decree of 1985 (Royal Decree-Law 2/1985) officially intended to lay the foundations for increasing the supply and reducing the rise in rents. The stated objective was to provide better access to rental housing and to increase the mobility of human resources. It eliminated de facto the forced rent contract extension and the possibility of subrogation. This regulation, which only affected new tenants’ contracts, led to a confusing situation that was not regulated until the new law on urban rents in 1994. However, what is certain is that this new regulation ended up contributing to a real estate policy focused on promoting homeownership. The significant tax advantages associated with the purchase of housing and the end of rent stability guarantees encouraged many tenants to move into homeownership.

This opened up a field for investment and a new expansionary phase of the Spanish property market based on massive household indebtedness. From 1985 to 1990, credit contracted by households for house purchases increased at an average annual rate of 28.6%, while debts increased by 23.3%. House prices followed similar rates of increase. The expansionary phase lasted until 1992, when a five-year period of crisis and adjustment began. From 1997 onwards, the exit from the crisis once again led to a new real estate-financial cycle, which ended up becoming the wildest and most catastrophic. Public action, while proclaiming a desire to increase rental contracts, in fact reinforced homeownership. It limited itself to massively fueling building investment, while reducing to a minimum any correction mechanism through public intervention. This resulted in a high proportion of secondary housing and unoccupied dwellings [

40]. Between 2000 and 2020, the population in Spain increased by 17.5% (from 40 to 47 million). Between 2000 and 2007, a period of intense immigration, the pressure on demand from population growth was combined with easy, low-interest credit. The reduction in interest rates and the liberal granting of mortgages with few guarantees stimulated heavy household indebtedness and a spectacular growth in the demand for homeownership that did not stop until the speculative bubble burst. It has been calculated that debt increased by more than 200%, due to the credit facilities, at the same time as the figures for the Spanish economy showed strong specialization in the building and real estate sectors [

39,

40,

41].

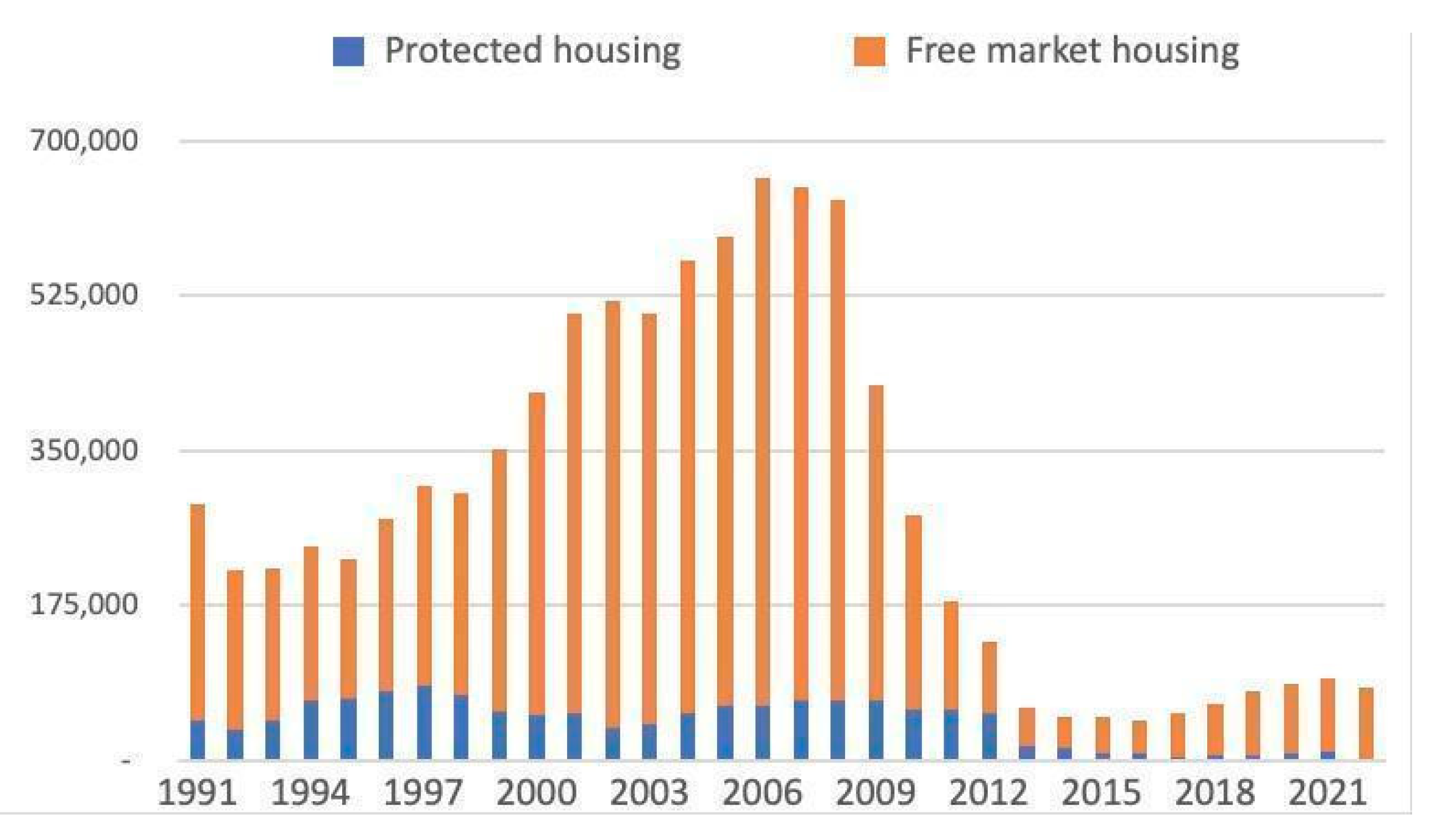

Reliance was placed exclusively on the market, and the meagre stock of public rental housing that was inherited not only was not increased, but decreased, as it was partly sold to tenants. The construction of social housing was halved from more than 85,000 units in 1997 to less than 41,000 in 2003. While the number of new homes on the market grew, Royal Decree-Law 5/1996 on the Liberalization of Land and the Aznar government’s Land Law 6/1998 allowed the development of any potential urban land that was not specially protected (

Figure 6 and

Figure 7).

As the data indicate, this facilitated the accelerated development of the free market for housing production, with a primary orientation towards homeownership. The legislative context, renewed confidence in the construction sector as a factor in the country’s economic development, and liberalizing and permissive economic policies regarding increasingly deregulated debt were factors that contributed to the explosive growth of Spain’s housing stock in the free market [

44,

45]—on the other hand, it is important to note that this period also saw a shift in urban development, with construction activity moving from the outskirts of cities such as Nou Barris in Barcelona. This area experienced significant growth due to urban densification in the 1960s and 1970s, followed by a decline in new housing production in the 1980s. Conversely, within the confines of proximate municipalities within metropolitan areas, where there existed available land for residential expansion, there was a notable concentration of this increase [

46].

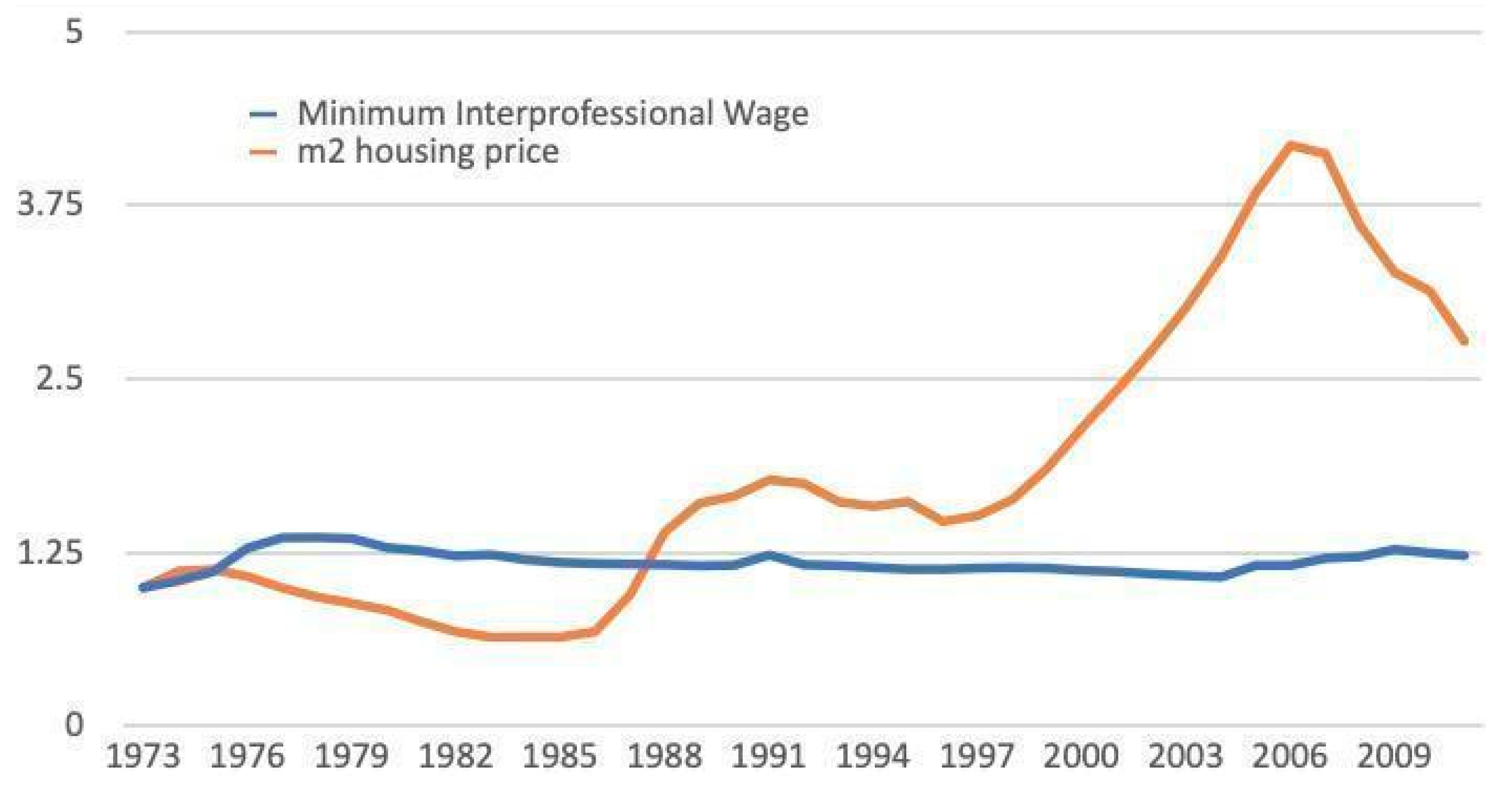

Government changes in political forces and the constraints of the complex administrative structure of powers inevitably led to an erratic, zigzagging legislative record and unintended effects. In addition, investments by democratic city councils in neighborhood improvements, persistent tax benefits for house ownership purchases, and the demand generated by the unexpected wave of immigration all contributed to a rise in land prices. It was a period with an increasing provision of mortgage credit across many countries and, undoubtedly, the speculative bubble fueled by easy credit triggered the abnormal rise in prices above the consumer price index (CPI) and above rents [

44,

45]. In this regard, it is worth noting that, prior to the 2008 crisis, mortgage lending in Spain had become increasingly aggressive and expansive, with financial institutions routinely offering loans of up to 100% of the property value, often without robust income verification. The deregulated financial environment, combined with historically low interest rates and the strong cultural preference for homeownership, resulted in unprecedented levels of household indebtedness. However, unlike countries such as the United Kingdom or Ireland—where post-crisis reforms introduced more rigorous regulation of mortgage lending and imposed tighter controls on loan-to-value ratios [

47,

48]—Spain was slower to implement such measures. It was not until the adoption of the Mortgage Law 5/2019 that significant protective mechanisms were introduced to reduce household risk exposure and to improve transparency in lending practices. The absence of early corrective intervention arguably exacerbated the social consequences of the housing bust, particularly for low-income and immigrant households, who had been encouraged to access credit under increasingly lax conditions during the boom years. This regulatory inertia not only deepened the impact of the crisis but also reinforced structural inequalities in access to housing and financial protection.

The impact on price increases is particularly evident if the evolution of the Interprofessional Minimum Wage (IMW) and the average price of housing are compared. It was the reckless policy of granting credit, concentrated in the real estate and housing sector, that triggered the bursting of the bubble and the collapse of the financial pyramid, which supported building, mortgage loans, and real estate activities [

44,

45].

While some features of Spain’s housing model and policy trajectory are undoubtedly specific, particularly regarding the institutional legacy and political context, the broader dynamics leading up to the crisis—especially the role of financial liberalization and credit expansion—were shared with other European countries. It is therefore important to situate the Spanish experience within a wider European framework that includes cases such as Ireland, the United Kingdom, and the Netherlands, where similar patterns of deregulated lending, speculative building, and eventual financial instability also emerged. In Ireland, the housing boom was especially intense relative to the size of the economy and led to a sovereign bailout in 2010. Spain avoided default but required a European rescue of its banking sector in 2012, particularly to stabilize the savings banks most exposed to real estate. Both countries saw a sharp rise in secondary and unoccupied housing, often in peripheral areas with poor infrastructure. Spain’s specificity lies not in the mechanism of the crisis, but in its intensity and socio-spatial dynamics—such as the dominance of homeownership and the weakness of public rental provision. As in other liberalized economies, the lack of effective regulation and countercyclical policy during the boom years was a key factor behind the housing and financial crisis.

3.5. Evictions, Rent Comeback, Vulture Funds, and Popular Rent-Seeking (2013–2023)

The impact of the crisis was particularly dramatic and harsh in Spain, due to the effect on the economy as a whole, where 60% of credit was compromised, and due to the rapid, brutal increase in evictions, initially for non-payment of mortgages [

46,

49]. In a context of economic crisis and growing unemployment, the high indebtedness of families, especially those who arrived in the last wave of immigration, led to strong mobilizations and the emergence of citizen platforms such as the Platform of People Affected by Mortgages (PAH) [

50,

51]. Over time, as the crisis, precariousness, and restriction of mortgage credit have imposed a strong contraction in the demand for homeownership, there has been a progressive expansion of the rental housing market and an increase in evictions resulting from non-payment of rent (in 2019, by means of Royal Decree-Law 7/2019 on urgent housing and rental measures, the terms prior to the liberalizing reform—5 years of mandatory extension—were recovered. The alternation of social democratic and liberal governments in recent decades has been key in the somewhat erratic evolution of the regulation, which has led to a certain perception of instability and legal insecurity).

The resetting of relations between real estate and financial actors in Spain was needed to rescue the banking sector and to transform nonperforming mortgages into income-producing assets in the housing sector. The SAREB (the Management Company for Assets Arising from Bank Reorganization) was created, in 2012, to buy such assets, and assume the losses, to clean up the banks’ balance sheets and seek new investors in the international markets. In this way, between 2014 and 2019, new financial players entered the market, in particular large investment funds that have displaced the traditional banking sector, which is heavily conditioned by the new solvency requirements [

52]. These new players have ended up controlling a large part of the commercial sector and, as lobbyists, have obtained tax advantages, legal reforms, and institutional support for their lines of business. For example, while the new mortgage regulations decisively restrict mortgage credit to the working classes, Law 4/2013 on Measures for the Flexibilization and Promotion of the Rental Market allows landlords to set the terms of contracts and facilitates the repossession of property, while at the same time cutting tenants’ rights with measures such as reducing the duration of contracts to three years. These changes have contributed to rapidly rising prices, tenant pressure, and evictions, and have led to an exponential increase in evictions resulting from non-payment of rent.

The housing market has taken on an increasingly global character. The investment and real estate interest of the major landlords, tourist pressure, and the emergence of liberalizing channels in terms of housing, such as the AirBNB model [

53,

54], have had a particular impact in Spain. But although the leading role of the large international investment funds has been unquestionable, as they are capable of forming a real estate lobby with enormous strength in the direction of the market, it cannot be forgotten that the majority of rented housing is still in the hands of private individuals. Thus, even in these years of restructuring and investment, a majority of housing transactions, close to 70%, have been for individuals and only 30% for legal entities—Land Registers show that more than 87% of property sales and purchases throughout Spain between 2014 and 2019 were in the hands of private individuals, natural persons. Legal entities did not exceed 13% of transactions, except in 2014 when they reached 15%. SAREB sales substantially confirm these proportions [

45].

All of this resulted in an exceptional housing situation in Spain. Over the past few decades, a complex interplay of legal, economic, demographic, and institutional factors has had a profound impact on Spain’s housing market. One of the most striking dynamics has been landowners’ ability to make substantial speculative profits without engaging in any economic or professional activity, simply by treating housing as a speculative market asset and stripping it of its social value. These unearned profits were largely the result of public urban planning decisions, revealing a legal framework that disproportionately favored private ownership [

55,

56].

Institutional weaknesses further exacerbated the situation. In many cases, public administrations lacked the foresight or political commitment to curb speculative behaviors. In the worst instances, they tolerated, if not directly enabled, corruption and systematically neglected to promote protected housing. Consequently, social housing policies were increasingly marginalized, despite growing structural needs.

Demographic and sociocultural changes have also played a key role. The arrival of large cohorts born in the 1970s on the housing market has coincided with increased demand, a trend that is expected to continue until smaller cohorts enter the market in the coming years. While the total population has grown by around 5% in recent years, the number of households has increased by almost 20%. This discrepancy is rooted in a sharp decline in average household size—from four people per dwelling decades ago to fewer than three today. Between 1994 and 2004 alone, the average dropped from 3.24 to 2.85 people per household, approaching the European average of 2.6 people. The rise in single-person households has further accelerated this process [

57].

Economic factors have also contributed to the inflation in housing demand. In the context of low returns on equity markets and historically low interest rates, real estate became an attractive and relatively safe investment. Mortgage conditions became increasingly favorable, with cheaper credit and aggressive lending practices that facilitated household indebtedness.

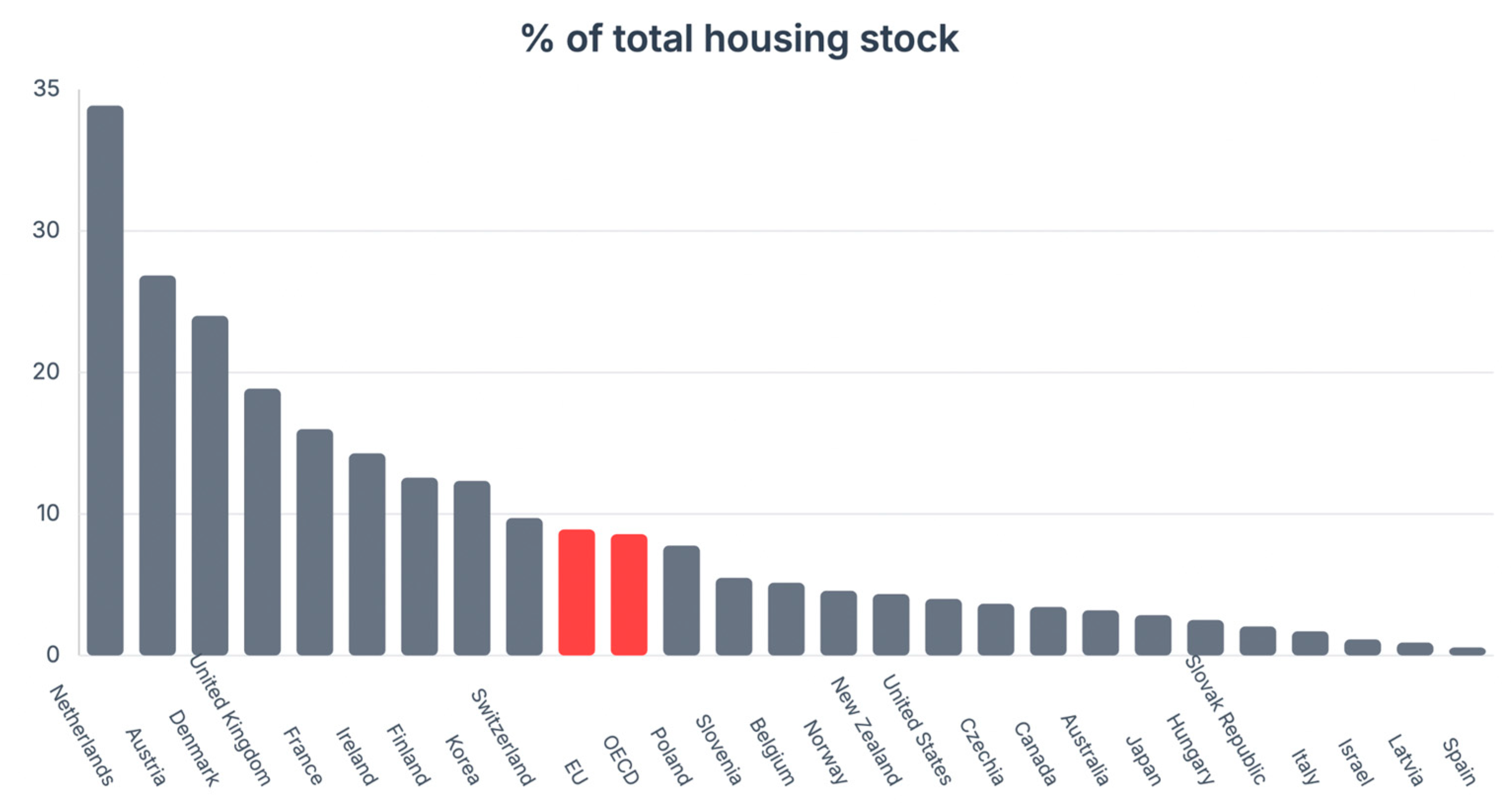

At the same time, public support for protected housing declined significantly. While around 50% of new housing in Spain was classified as protected three decades ago, this figure had dropped to less than 8% by the early 2000s. This was accompanied by a significant shortage of social rental housing: the public sector currently owns less than 1% of all dwellings, compared to an average of around 12% across Europe [

58].

Additional pressure has come from two further sources. Firstly, the growing settlement of immigrant populations—now representing almost 10% of Spain’s population—has generated sustained demand. Secondly, foreign buyers, particularly from other EU countries, have continued to purchase second homes in coastal and tourist regions, contributing to price increases in these areas.

Finally, the persistent weakness of Spain’s welfare system has led many citizens to view housing as a form of private social security. In a context of low pensions and limited public support in old age, owning a home is still widely perceived as a vital guarantee of long-term stability [

59].

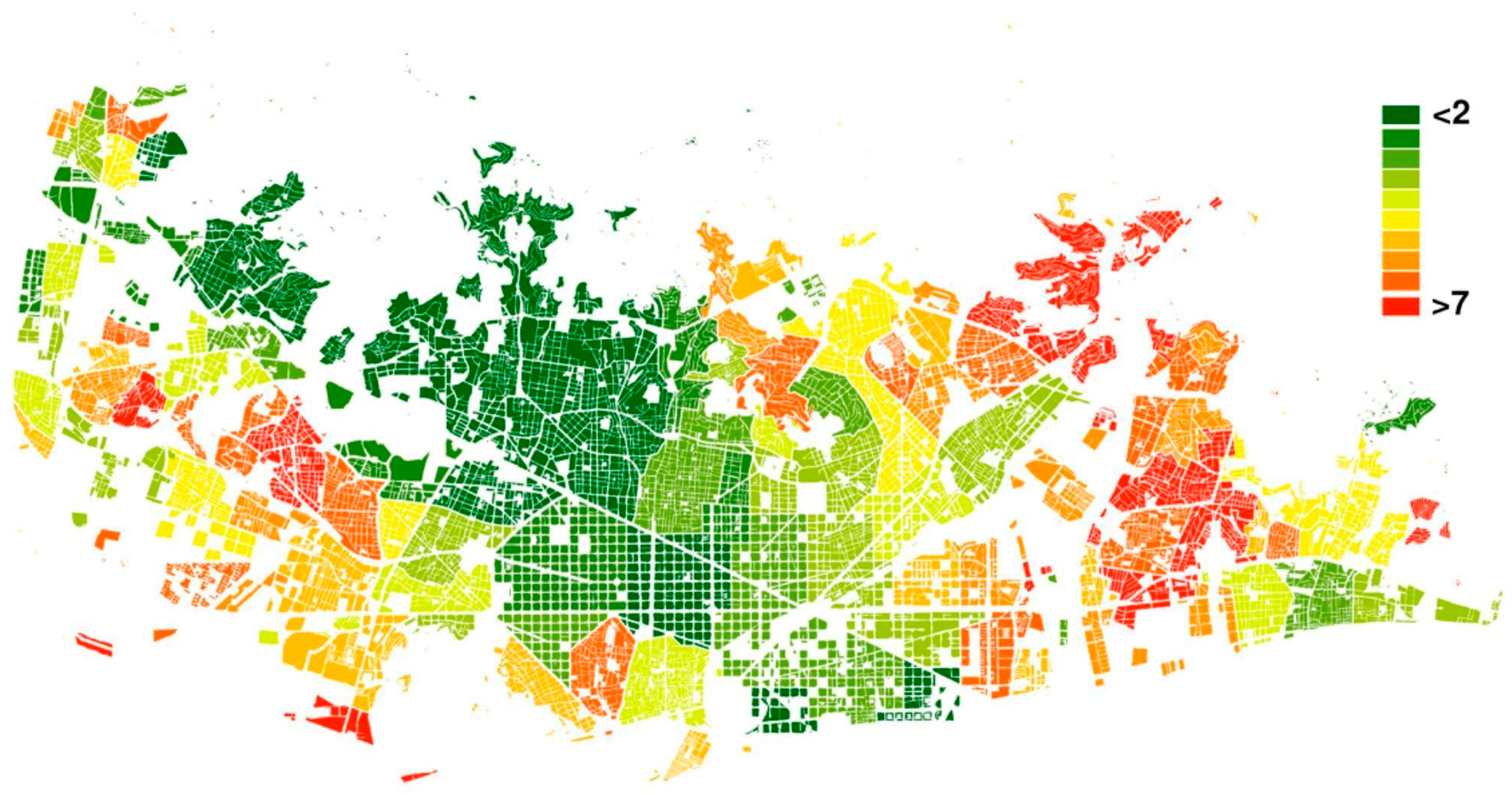

The city of Barcelona has been severely affected by this context, with areas such as Nou Barris becoming paradigms of fragility and implicit social vulnerability, as illustrated in

Figure 8 [

60].

These areas have experienced high population density due to progressive densification, insufficient average housing sizes, and a high number of inhabitants per housing unit. Other factors, such as an ageing population, immigration from outside the EU, and low household incomes, have resulted in these areas being inhabited by the most disadvantaged social classes, as well as those who are potentially at risk of residential vulnerability and more exposed to situations of fragility, such as those evident during the pandemic [

61].