Abstract

Photoacoustic (PA) velocimetry offers a promising solution to the limitations of conventional techniques for measuring blood flow velocity. Given its moderate penetration depth and high spatial resolution, PA imaging is considered suitable for measuring low-velocity blood flow in capillaries located at moderate depths. High-resolution measurements based on PA signals from individual blood cells can be achieved using a high-frequency transducer. However, high-frequency signals attenuate rapidly within biological tissue, restricting the measurable depth. Consequently, low-frequency transducers are required for deeper measurements. To date, PA flow velocimetry employing low-frequency transducers remains insufficiently explored. In this study, we investigated the effect of the concentration of particles that mimic blood cells within vessels under low-concentration conditions. The performance of flow velocity measurement was evaluated using an ultrasonic transducer (UST) with a center frequency of 10 MHz. The volume fraction of particles in the solution was systematically varied, and the spatially averaged flow velocity was assessed using two different distinct analysis methods. One method employed a time-shift approach based on cross-correlation analysis. Flow velocity was estimated from PA signal redpairs generated by particles dispersed in the fluid, using consecutive pulsed laser irradiations at fixed time intervals. The other method employed a pulsed Doppler method in the frequency domain, widely applied in ultrasound Doppler measurements. In this method, flow velocity redwas estimated from the Doppler-shifted frequency between the transmitted and received signals of the UST. For the initial analysis, numerical simulations were performed, followed by experiments based on displacement measurements equivalent to velocity measurements. The target was a capillary tube filled with an aqueous solution containing particles at different concentration levels. The time–domain method tended to underestimate flow velocity as particle concentration increased, whereas the pulsed Doppler method yielded estimates consistent with theoretical values, demonstrating its potential for measurements at high concentrations.

1. Introduction

Blood flow measurement is essential for detecting abnormalities in the human body. In patients with diabetes, the amount of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in the blood increases, accumulating beneath the endothelial cells of blood vessels and forming substances known as plaques. These substances accumulate, and can lead to peripheral artery disease, thereby resulting in abnormal blood flow. In cases of peripheral artery disease, small vessels in the feet tend to become clogged, which can eventually lead to difficulty in walking [1]. Therefore, detecting abnormalities in the body before they progress into serious diseases through blood flow measurement is highly effective.

Existing diagnostic methods for blood flows include ultrasound Doppler and laser Doppler methods. In the ultrasound Doppler method, the blood velocities are estimated by measuring the frequency shifts between the transmitted and received waves [2,3]. Although it enables deep tissue measurement because of the low scattering of sound waves in the body, it has low spatial resolution because it is difficult to distinguish between the reflected waves from the target and those from surrounding tissues. The laser Doppler method [4,5] estimates flow velocities from Doppler shifts of the frequencies of the scattering light caused by the particles’ motions through the region where a pair of laser beams are focused. This method offers a high spatial resolution due to significant differences in the optical absorption characteristics of tissues. However, the strong scattering of light within the body limits measurements to shallow depths near the skin surface. In this study, we focus on blood flow measurement using PA technology [6]. Photoacoustics enables the measurement of microvessels at moderate depths that can not be measured using conventional methods, with the advantage of differences in optical absorption contrast of tissues and the deep penetration of ultrasound [7]. Table 1 lists a comparison of the resolution and measurement depth of ultrasound Doppler, laser Doppler, and PA flowmetry (PAF) [8]. PAF includes optical resolution (OR) and acoustic resolution (AR). In OR-PAF, successful measurements were confirmed using animal blood; however, it requires focused light inside the tissue, and thus the measurement depth is limited to near the skin surface, which restricts utilizing the potential of photoacoustics to measure at moderate depths [9]. AR-PAF enables deep-tissue measurements by diffusing laser light and acquiring localized PA signals using a focused probe. Brunker and Beard reported OR-PAF measurements using particle suspension [10]; however, these were limited to concentrations one order of magnitude lower than the actual blood volume ratio, and measurements at the high concentrations required for actual blood have not been achieved. In addition, for the spatial resolution, OR-PAF requires the ability to distinguish individual particles, meaning that the spatial resolution of PA ultrasound must be smaller than the inter-particle distance by principle. This necessitates a receiver element with a frequency bandwidth exceeding tens of MHz [11]. On the other hand, high-frequency ultrasound attenuates easily within the body and is unsuitable for deep measurements, which makes low-frequency measurements necessary [12]. Recently, flowmetry based on a series of reconstructed three-dimensional images redhas been implemented in three-dimensional PA tomography [13,14]. In their measurements, the magnitude and direction of blood flow velocities were estimated based on the image processing of the reconstructed volume fields of the blood vessels. However, their processing is based on the reconstructed images that suffer from the imperfect reconstruction of the blood vessels [15]. Flowmetry based on a physical principle is expected.

Table 1.

Comparison of measurement performance of existing techniques for blood flow velocity.

In this study, flow velocity measurements are conducted using a low-frequency ultrasound transducer (UST). The volume ratio of the particles to the solution is varied to 1%, 5%, 10% for investigating how the volume ratio affects the accuracy of the low-frequency UST. In addition, time–domain analysis using the time-shift method and frequency–domain analysis using the pulsed wave (PW) Doppler method are performed to compare the results.

The rest of this manuscript is organized as follows. In Section 2, we explain the principles of measurement methods with the limit of measurement uncertainty. In Section 3, we describe the methods and conditions used in both numerical analysis and experiments. In Section 4, we present the results of the numerical analysis and measurements in the experiments. The results are discussed concerning the volume fraction of particles (VFPs) and different measurement methods: time-shift method and PW Doppler method. In Section 5, we present the conclusions of this study.

2. Principle

2.1. Time-Shift Method

The velocity of an absorbing object is obtained as the displacement of the object divided by a time difference of the pulsed irradiation of light [10]. The displacement is measured as a product of the sound speed multiplied by the time difference of the arrival time of a pair of PA waves detected by a UST. The time difference arises because of object movement; otherwise, it remains zero. The sign of the time difference indicates the direction of object motion. For calculating the time difference of arrival times, a cross-correlation (CC) analysis is used for signal processing. The CC of a pair of PA waves enables evaluating the time difference, assuming the object velocity is unchanged during the emission of the signal pair. The measurement performance of the time-shift method has been redextensively investigated in a previous study [16].

We consider a pair of continuous PA signals in the time domain, and . If the CC function is denoted as , and time-shift is , then can be expressed as

Next, we consider the discrete case. Let us take two discrete data sets and , with j being their index. If the CC function in the discrete case is denoted as with k being the shift index, and then, can be expressed as

The CC function shifts when there is a phase difference between the signals before and after the object movement. This shift enables us to determine the shift amount n at which the correlation value between the signals before and after movement is maximized. The product of this value and the time resolution of the oscilloscope corresponds to the difference in signal arrival time. Therefore, the time difference can be obtained as

We set the time interval of successive pulse irradiations , the particle displacement during the time interval L, speed of sound c, time difference in the arrival of the signal , resolution of the time dt, and amount of data shift n. The data shift n is defined as the value at which the CC between the two signals reaches its maximum. Then the velocity v can be expressed as follows.

2.2. Pulsed-Wave Doppler Method

The PW Doppler method is a technique used in ultrasound Doppler measurements. In ultrasound Doppler, an ultrasound wave is transmitted toward the target, and the reflected wave from the target is received. The frequency spectrum of the reflected wave shifts from that of the transmitted wave (Doppler shift when the target is in motion) [12]. The flow velocity is measured based on this Doppler frequency. We verify this method using PA waves. When pulsed lasers are sequentially irradiated with a time shift onto light-absorbing particles dispersed in a fluid, the generated PA signals exhibit a phase shift because of the Doppler effect caused by particle motion. The Doppler frequency can be determined, from this phase difference and the flow velocity v can be calculated. The theoretical expression for the PW method is

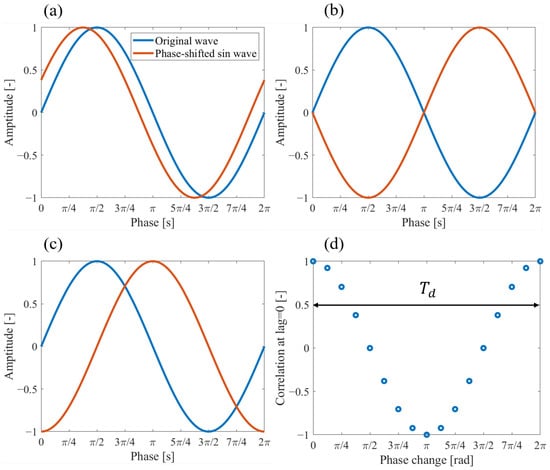

Here, , c, and represents the Doppler frequency, speed of sound, frequency of the PA wave, and angle between the target and the probe axis of the UST, respectively. Figure 1a shows a sine wave with a phase shift of from the original wave. When the phase shift is small, the value of the convolution integral at the zero shift approaches 1. Figure 1b shows a sine wave with a phase shift of , which results in an inverse phase compared to the original wave, yielding an integral value of . Figure 1c shows a sine wave with a phase shift of , and the corresponding integral value becomes 0. By shifting the phase in steps of and calculating the convolution integral value at each zero shift, the integral value first decreases and then increases again. This behavior is plotted in Figure 1d. The resulting waveform in Figure 1d has a period , which corresponds to the time it takes for the PA wave to shift by one wavelength. The Doppler frequency can be obtained by taking the inverse of this period. Since PA waves are broadband, it is difficult to determine their frequency precisely. Therefore, the PA signal is processed with a fast Fourier transform (FFT), and a bandpass filter is applied around the frequency peak to approximate a redsingle-wavelength signal, determining the PA frequency . Moreover, filtering helps approximate a single-wavelength signal and facilitates the observation of waveforms such as those shown in Figure 1 because actual PA signals include multiple frequency components.

Figure 1.

Theoretical diagram of Doppler frequency analysis using the PW Doppler method: (a) time signal with a phase shift of —, (b) time signal with a phase shift of —, (c) time signal with a phase shift of —, and (d) variation of correlation values with a phase change.

2.3. Directional Characteristics of UST

An UST exhibits either directional or omnidirectional characteristics. A fully directional UST has an extremely narrow, cylindrical measurement volume. In this case, more than one absorber does not exist at the same distance from the transducer, and thus, the PA signals are not spatially averaged. An omnidirectional UST spatially averages PA signals generated from absorbers located at the same distance from the transducer. Variations between adjacent particles are smoothed out when the distance between particles is smaller than the spatial resolution, thereby resulting in spatial averaging. A focused UST may exhibit intermediate characteristics between the directional and omnidirectional types because it forms a narrow cylindrical measurement volume at the focal point. The directional and omnidirectional characteristics of USTs were investigated using k-Wave: a redMATLAB® R2023b Toolbox for the time–domain simulation of acoustic wave fields [17].

2.4. Uncertainty Limit

The measurement uncertainty of the flowmetry includes a statistical part contributed by randomly changing samples and a biased one intrinsic in the method or instrument. The statistical part can be reduced by acquiring a greater quantity of samples, whereas the biased part remains constant. One can recall the concept of the Cramér-Rao Lower Bound (CRLB) in the statistical signal processing to estimate the uncertainty limit [18]. Although the lower limit by the CRLB originates from the statistical process, it contributes to the uncertainty as a bias. The CRLB provides a base value of uncertainty at a given condition of the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). In the time-shift method, the deviation of time shift caused by electronic noise and uncorrelated physical processes is referred to as a jitter error. The lower bound of the jitter error based on the CRLB under a given SNR condition was derived by [19] as

where , , T, B, redand redrepresent the jitter error, center frequency, time window length, fractional bandwidth, normalized CC coefficient, and signal-to-noise ratio, respectively. Based on the experimental conditions, the center frequency was set to 10 MHz, time window T to 3 μs, and fractional bandwidth B to 1.2. The normalized cross-correlation coefficient strongly depends on the SNR, and therefore the CRLB was calculated by varying between 0.8 and 1.

3. Methods and Conditions

The UST used in this study had a focal diameter of 2 mm with the performance regarded as intermediate between directional and omnidirectional USTs described in Section 2.3. The characteristics of both directional and omnidirectional USTs were investigated using numerical analysis.

3.1. Numerical Analysis

3.1.1. Directionality of UST

The characteristics of a fully directional UST were investigated using numerical analysis. A computational grid of 150 × 150 × 150 points with a spacing of 15 m was generated. An omnidirectional sensor was placed at the position (20, 75, 75). The sensor characteristics were set with a center frequency of 10 MHz and a frequency range from 3.8 MHz to 16.2 MHz. A spherical initial pressure source simulating a particle was placed along a single direction, coaxial with the sensor to reproduce the characteristics of a directional UST. The center of the sphere was positioned along the line from (50, 75, 75) to (150, 75, 75), and a spherical initial pressure with a diameter of 50 m was generated for each center coordinate. The number of particles N was varied from 1 to 100, and a numerical simulation was performed for each case.

3.1.2. Non-Directionality of UST

The characteristics of a nondirectional UST were investigated using numerical analysis. A computational grid of 150 × 150 × 150 points with a spacing of 15 m was generated. An omnidirectional sensor was placed at the position (20, 75, 75). The sensor characteristics were set with a center frequency of 10 MHz and a frequency range from 3.8 MHz to 16.2 MHz. Particles were randomly distributed according to each VFP within the coordinate range from (25, 25, 25) to (125, 125, 125) to reproduce the features of an omnidirectional sensor. Spherical initial pressures with a diameter of 50 m were generated at each particle position. The VFP was varied from 0.01% to 40%, and a numerical simulation was performed for each case. The Wigner–Seitz radius was computed to compare the weighted average of frequency spectrum (WAFS) with the inter-particle distance. Assuming the effective volume occupied by a single particle as a sphere, the total solution volume V was divided by the number of particles N, and the radius of this sphere was referred to as the Wigner–Seitz radius .

Using the Wigner–Seitz radius and particle radius r, the inter-particle distance g was calculated under the assumption that the particles were uniformly arranged.

3.2. Experimental Apparatus

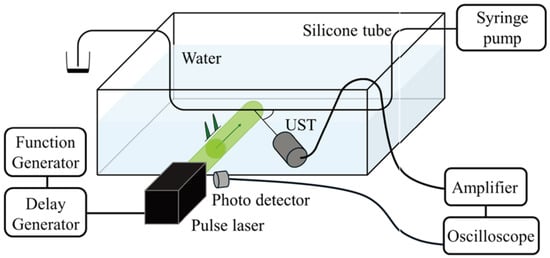

The experimental setup for the time-shift method is shown in Figure 2. A particle suspension prepared by mixing black particles with a solution was used as the measurement target. The suspension was injected into a silicone tube with outer and inner diameters of 1.5 mm and 1.0 mm, respectively. We used black paramagnetic polyethylene particles with a specific gravity of 1.2 and a particle diameter in a range of 53–63 m (redCospheric: Santa Barbara, California, USA, BKPMS-1.2 53–63 m). The solution was prepared by mixing water and glycerol at a mass ratio of 1:4.2 to prevent the particles from settling; this resulted in a specific gravity of 1.2. An Nd:YAG pulsed laser with a wavelength of 532 nm and a pulse duration of 5–9 ns (redRayture Systems: Shinjuku, Tokyo, Japan, GAIA Dual) was used as the irradiation source. Although the maximum repetition rate of a single laser was around 20 Hz, two lasers were used in combination, and the pulse interval was controlled using a function generator (redRigol Technologies: Suzhou, China, DG1022Z) and a delay generator (Quantum Composers: Bozeman, Montana, USA, 9618). A focused UST (redEvident Scientific: Shinjuku, Tokyo, Japan, V311-SU) with a center frequency of 10 MHz, a focal length of 30 mm, and a focal diameter of 2 mm was used. The UST was connected to an amplifier to amplify the signal, which was then recorded using an oscilloscope (redRohde & Schwarz: Munich, Bavaria, Germany, RTM3004). The timing of the laser irradiation was detected using a photodetector (redThorlabs: Newton, New Jersey, USA, DET10A2).

Figure 2.

Experimental setup at the time-shift method: Black polyethylene particles were used as the light-absorbing particles, and a pulsed laser with a 532 nm wave length was irradiated. The time interval of the irradiation was set to 500 s, and the actual timing was monitored with a photodetector. The generated photoacoustic waves were acquired using an UST with a center frequency of 10 MHz.

3.3. Time-Shift Method

A pulse signal with a frequency of 15 Hz was sent from the function generator to the delay generator, and the laser excitation and irradiation timing were set with reference to the first pulse signal. The laser irradiation interval was set to 500 s. Each pulse emission timing was detected by a photodetector (response time: 1 ns). The VFP in the solution was set to 1%, 5%, 10%. The average flow velocity inside the tube, based on the flow rate setting of the syringe pump, ranged from 20 mm/s to 90 mm/s, and ten pairs of PA signals were acquired at 10 mm/s intervals. The photodetector and PA signals were interpolated 100 times using spline interpolation. The irradiation timing was determined by calculating the time derivative of the photodetector signal using the central difference scheme and identifying its maximum value. Based on this reference, the PA signals were extracted using an arbitrary number of data points. The data shift between the two PA signals was obtained via CC analysis. The measured flow velocity corresponding to each preset flow velocity was calculated from this data shift using Equation (4). The measured velocities were averaged over ten trials for each flow rate condition. The bias between the measured and preset velocities for each volume ratio was calculated using

3.4. PW Doppler Method

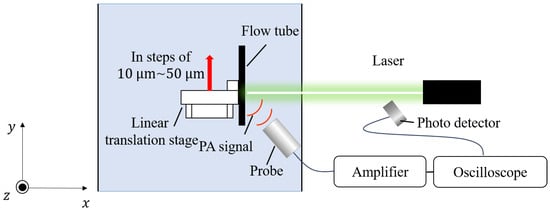

The experimental configuration for the PW Doppler method is schematically shown in Figure 3. The displacement was estimated using the PW Doppler method. The flow tube into which the solution was injected was fixed using a device fabricated with a 3D printer. The setup was mounted on a redlinear translation stage (Thorlabs XR25P/M), which enabled movement in 10 m increments. Agar (mixture mainly composed of agarose and agaropectin [20]) was added to the solution at a mass ratio of 10% to suppress particle movement within the flow tube. A photograph of the experimental setup was captured, and the angle between the flow tube and probe was measured using the software tool ImageJ 1.54d. The fixed flow tube was moved in steps of 10 m, 20 m, 30 m, 40 m, and 50 m, and the signals were acquired ten times at each displacement. The displacement was calculated from the signal at 0 m and the signals at each displacement; these values were compared with the actual displacements.

Figure 3.

Experimental configuration at the PW Doppler measurement: Black polyethylene particles were used as light-absorbing particles, and a nano-second pulsed laser was irradiated. A particle suspension solidified with agar was placed in the flow tube, and it was displaced at equal intervals using a redlinear translation stage.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Numerical Analysis

4.1.1. Effect of Directional UST

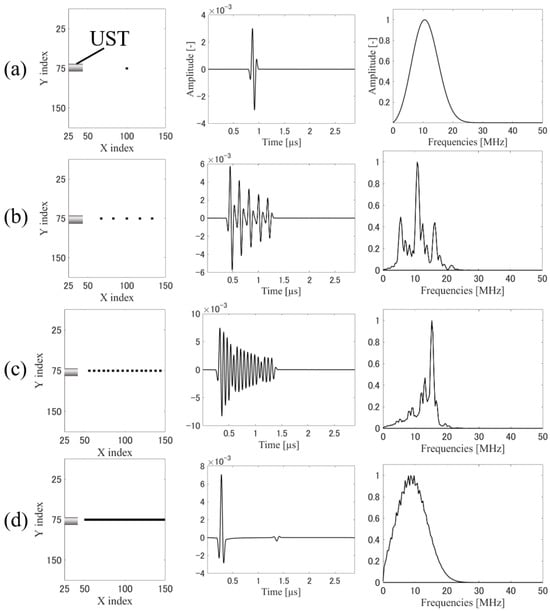

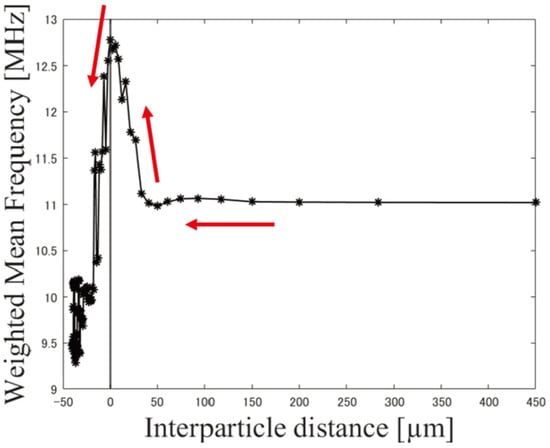

Representative results of the numerical analysis redfor the directional UST are shown in Figure 4. The first column shows initial pressure distributions; the second column, acquired signals; and the third column, frequency spectra of the signals. Changes were observed in the frequency spectra with the VFP. We calculated the WAFS for each case to evaluate the variation. The results are shown in Figure 5, where the horizontal axis indicates the inter-particle distance for each number of particles, and the vertical axis shows the WAFS. When the inter-particle distance was longer than 50 m, signals did not overlap, and the WAFS remained nearly constant. The low-frequency components decreased as the signals began to overlap, and the WAFS shifted toward higher frequencies. The WAFS dropped sharply, when the inter-particle distance fell below 0 m. In other words, when the distribution changed from heterogeneous to homogeneous, the WAFS shifted toward the lower-frequency range. The center frequency of the UST was 10 MHz, which redcorresponded to a spatial resolution of around 75 m. Even when compared to this value, the WAFS did not shift to lower frequencies below the spatial resolution. This implies that UST can individually identify particles within a heterogeneous target if the UST has perfect directivity, regardless of the axial spatial resolution.

Figure 4.

Simulation of directional UST: A 150 × 150 × 150 grid with a spacing of 15 m was generated, and an omnidirectional sensor with a center frequency of 10 MHz and a frequency range from 3.8 MHz to 16.2 MHz was placed at (25, 75, 75). (a) Simulation results with a single particle: The spectrum peak spreads around 11 MHz in accordance with the characteristics of the sensor. (b) Simulation results with five particles: With the increase of inter-particle distance, the signals hardly overlap. Further the spectrum spreads around 10 MHz, following the characteristics of the sensor. (c) Simulation results with 16 particles: The signals overlap, which lead to a reduction in low-frequency components. (d) Simulation results with 100 particles: The particles overlap and form a cylindrical initial pressure distribution. The signals overlap, and the spectrum shifts toward the lower frequency range compared to (a).

Figure 5.

Relationship between inter-particle distance and weighted-averaged frequency spectrum (WAFS) in directional UST. The horizontal axis represents the particle spacing, and the vertical axis shows the WAFS of the frequency spectrum obtained from the simulation results. Up to around 50 m, the WAFS remains nearly unchanged where the signals do not overlap. The low-frequency components decrease as the signals begin to overlap causing the WAFS to increase. When the particle spacing falls below 0 m, which results in overlapping particles, a downshift occurs toward lower frequencies occurs. This continues until the particles completely overlap, forming a cylindrical initial pressure distribution.

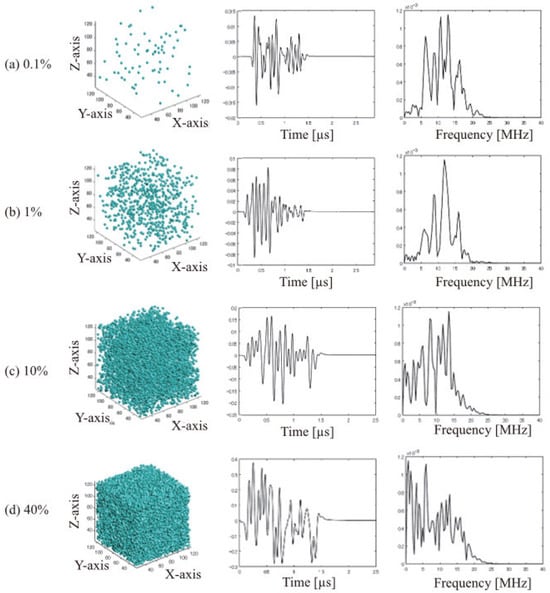

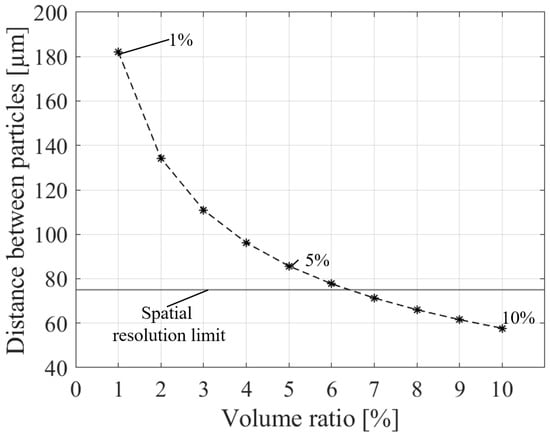

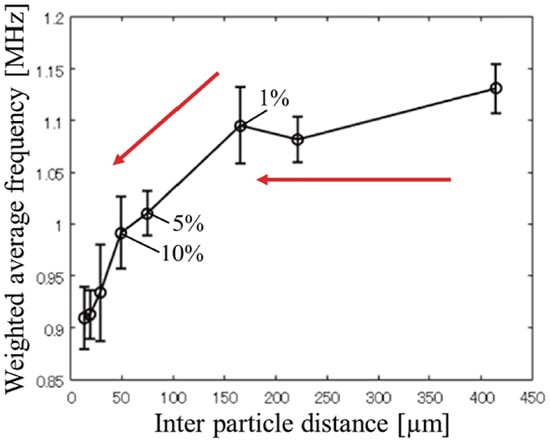

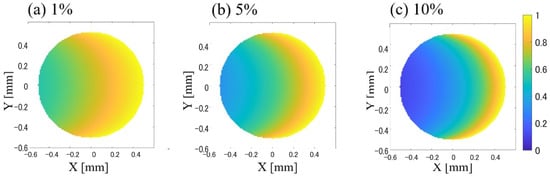

4.1.2. Effect of Non-Directional UST

Representative results of the numerical analysis redfor the non-directional UST are shown in Figure 6. The first column shows the initial pressure distributions; the second column, acquired signals; and the third column, frequency spectra of the signals. Figure 7 shows the inter-particle distance and spatial resolution for each VFP. Figure 8 presents a comparison between the inter-particle distance and WAFS. By comparing Figure 7 and Figure 8, it can be observed that the WAFS remains nearly constant when the inter-particle distance is well above the lateral spatial resolution (i.e., below 1% VFP). When the inter-particle distance approaches or falls below the spatial resolution (i.e., above 5% VFP), the WAFS shifts toward lower frequencies. This shift can be attributed to spatial averaging, which smooths out the variations between particles. Thus, under these conditions, the omnidirectional UST exhibits spatial averaging above 5% VFP, which treats particles within a heterogeneous target as a uniform medium.

Figure 6.

Simulation of omnidirectional UST. A 150 × 150 × 150 grid with a spacing of 15 m was generated, and an omnidirectional sensor with a center frequency of 10 MHz and a frequency range from 3.8 MHz to 16.2 MHz was placed at (20, 75, 75). At 1% VFP, where the particle spacing is below the spatial resolution, the frequency spectrum follows the characteristics of the sensor and is distributed around 11 MHz. At 10% VFP, where the particle spacing is also below the spatial resolution, it increases the low-frequency components of the frequency spectrum. At 40% VFP, the low-frequency components further increase.

Figure 7.

Particle spacing at each volume fraction of particles. The horizontal axis represents the VFP, and the vertical axis represents the particle spacing. Comparing the spatial resolution of 75 m red (illustrated as horizontal line) with the particle spacing, at 1% VFP, the particle spacing is well above the spatial resolution, whereas at 10% VFP, it falls below the redresolution.

Figure 8.

Relationship between particle spacing and spectrum in omnidirectional UST. The horizontal axis represents the inter-particle distance, and the vertical axis represents the WAFS of the frequency spectrum. For particle spacings below 1% VFP, which are well below the spatial resolution, the WAFS shows little change. The frequency spectrum shifts toward the lower frequencies when the particle spacing approaches or falls below the spatial resolution.

4.2. Measurements Based on the Time-Shift Method

4.2.1. Effect of VFP on Measurement

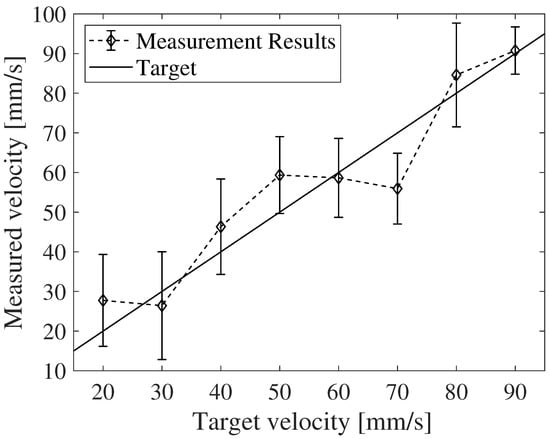

Figure 9 shows the measurement results of the flow velocities at 1% VPF. The mean bias is 5.7%, and the measured flow velocity changes linearly with the theoretical values. The uncertainty is 13 mm/s, which corresponds to a time delay of 3 ns. Here, the average SNR of the signal is 28 dB, and the normalized CC coefficient is 0.9. The CRLB was calculated by substituting these values into Equation (6). Under the experimental conditions, the CRLB was estimated to be ~1 ns, which is on the same order as the uncertainty in the experimentally obtained time shift. This implies that the uncertainty in the measurement is reasonable and likely caused by factors such as electronic noise and uncorrelated physical processes.

Figure 9.

Flow velocity measurement results at 1% VFP. The average bias was 5.7%, and the measurement results varied linearly by the theoretical values.

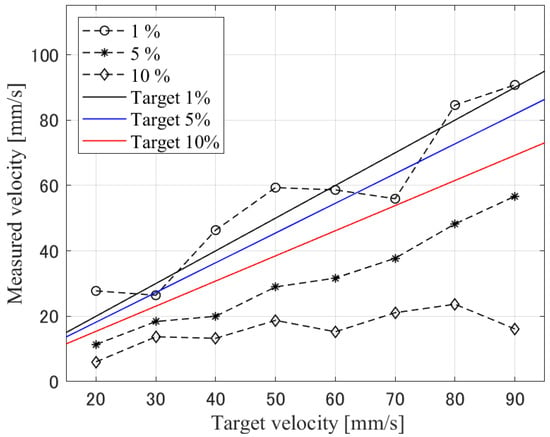

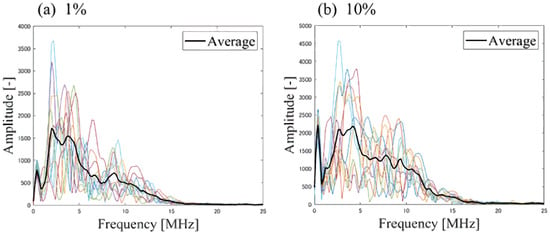

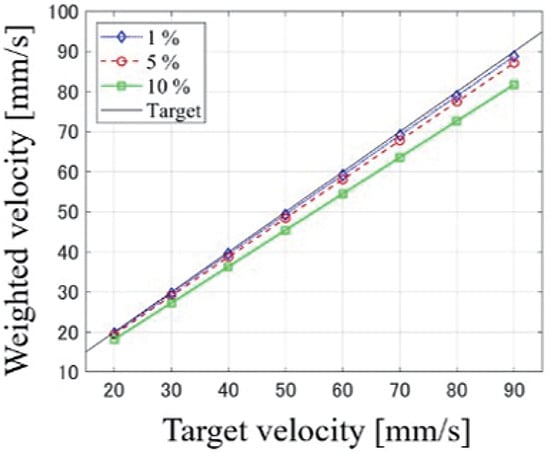

The sound speed in the solution without particles was 1500 m/s at the experiment [21]. Under the same temperature, the sound speeds at each particle concentration were estimated based on existing models [22,23]. In general, the sound speed increases when solid particles are suspended in a liquid. The estimated sound speeds were 1505 m/s, 1528 m/s, and 1551 m/s for the concentrations of 1%, 5%, and 10%, respectively [21]. Figure 10 shows the measurement results when the variation of VPF. The target velocities were plotted in the graph for the individual VFPs taking into account of the viscosity increases with an assumption of Newtonian fluid with particle suspensions [24]. The average bias was 5.7% at 1% VFP, −42% at 5% VFP, and −68% at 10% VFP. Figure 11 shows representative frequency spectra for 1% VFP and 10% VFP. The measurement results show that increasing the VFP underestimates the flow velocity. Two factors can be considered in this regard: (1) the effect of the light penetration depth. Increasing the VFP increases the amount of light absorption, which limits light absorption to the low-speed region of the flow inside the tube, possibly leading to an underestimation of the flow velocity. (2) The other is the effect of the UST characteristics. The USTs have a narrow cylindrical measurement area at the focal volume, potentially exhibiting intermediate characteristics between directional and non-directional USTs. As shown in Section 4.1.1, directional USTs can individually identify particles in non-uniform media regardless of the lateral spatial resolution. The omnidirectional UST may not be able to individually identify particles when the inter-particle distance is below the spatial resolution, thereby resulting in spatial averaging because of the dominance of low-frequency components in the frequency spectrum. If the UST used in this experiment is omnidirectional, it may not individually identify particles or observe particle movement, potentially leading to an underestimation of flow velocity.

Figure 10.

Measurement result of the flow velocity in the tube with different concentrations of the particles at 1% VFP, 5% VFP, and 10% VFP. The results are compared to the redcorresponding theoretically-expected value as the bulk mean velocity of the fully-developed laminar flow of Newtonian fluid based on the volumetric flowrate of the syringe pump. The results shows a tendency to underestimate with an increase in the VFP, and bias of 5.7% for 1% VFP, −36% for 5% VFP, and −65% for 10% VFP.

Figure 11.

Comparison of frequency spectra of photoacoustic signals with different concentrations at (a) 1% VFP, (b) 10% VFP. At 10% VFP, low-frequency components are more dominant compared at 1% VFP.

4.2.2. Light Penetration Depth

Increasing the VFP increases the amount of light absorbed per unit volume, limiting light irradiation to the vicinity of the tube wall. When the flow inside the tube follows the velocity distribution of a fully-developed laminar flow (Hagen–Poiseuille flow) of a Newtonian fluid, the flow velocity will be underestimated if light irradiation is limited to the vicinity of the wall. The light absorption coefficient at each VFP was calculated using Lambert-Beer’s law to investigate the effect of the light penetration depth [25].

Table 2 presents the absorption coefficients and attenuation ratios of the light energy before and after transmission through a 1 mm-thick glass cuvette for each VFP. The light energy was corrected based on the measurement results at VFP 0%. The absorption coefficients were calculated using the redLambert-Beer’s law. The light attenuation ratios across the cross-sectional area of the flow tube were calculated using these values. The results are shown in Figure 12. The computational grid was set to 100 × 100 with an interval of 0.01 mm, and a circle with a radius of 0.5 mm was used as the cross-section of the flow tube. Assuming that light was irradiated from the positive X direction, the distance between each coordinate and the wall surface in the positive X direction was taken as the light path, and the light attenuation ratio was calculated using Lambert-Beer’s law. Light is sufficiently irradiated near the wall surface in the positive X direction and attenuates as it progresses in the negative X direction. This was calculated based on the light absorption coefficient at each VFP. The light attenuation became more pronounced with an increase in VFP. The weighted flow velocity was calculated from the following equation, using this light attenuation ratio as the weight.

Table 2.

Absorption coefficients and attenuation ratios at each VFP.

Figure 12.

Light attenuation ratio across the cross-section of the flow tube. The light attenuation ratio in the cross-sectional area of the flow was calculated using the light absorption coefficient for each VFP. When the incident light is irradiated from the positive X-direction, the attenuation is smaller near the wall in the positive X-direction and increases toward the center. Higher VFP results in more pronounced light attenuation.

We calculated the weighted average flow velocity for each velocity range. The spatial distributions of the flow velocities were calculated for the cross-sectional area inside the tube. The results are shown in Figure 13. The redunderestimation rate was −3.2% at 5% VFP and −9.1% at 10% VFP, which is smaller than the redunderestimation rate of flow velocity measurements. Therefore, light penetration depth has a minor effect on the underestimation.

Figure 13.

Weight-averaged flow velocity. The weight-averaged flow velocity was calculated using the light attenuation ratio across the cross-sectional area of the flow, weighted by the light absorption coefficient for each VFP. For all the VFP, the flow velocity changes linearly with the target.

4.2.3. Effect of UST Properties

Spatial averaging occurs in an omnidirectional UST when the inter-particle distance falls below the lateral spatial resolution, and low-frequency components become dominant. Figure 7 shows that the particle spacing is well above the spatial resolution at 1% VFP; however, it falls below it at 10% VFP. In addition, as shown in Figure 11, at 10% VFP, low-frequency components become dominant compared to those at 1% VFP. Under the experimental conditions of this study, increasing VFP causes the inter-particle distance to fall below the spatial resolution, which leads to spatial averaging. The spatial averaging prevents the identification of individual particles, thereby hindering the observation of particle movements and leading to an underestimation of flow velocity. This is likely because the focal diameter (2 mm) of the UST at the experiment was 40 times larger than the particle diameter (50 m), leading to the omnidirectional effect becoming dominant.

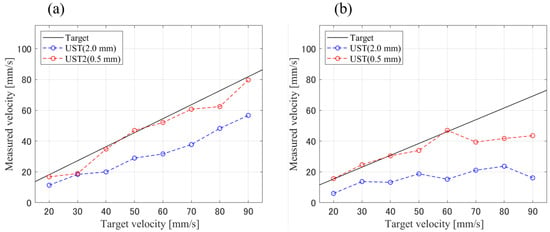

4.2.4. Effect of Spatial Resolution

Directional UST can identify individual particles within an inhomogeneous target regardless of the axial spatial resolution. This suggests the possibility of improving the measurement performance at a high VFP by reducing the focal diameter and narrowing the measurement area. We describe the experimental results obtained using another UST with a smaller focal diameter (Japan Probe, B10K20I R30). We used a UST with a center frequency of 10 MHz and a focal diameter of 2.0 mm (hereafter UST (2.0 mm)), and another UST with a center frequency of 10 MHz and a focus diameter of 0.5 mm (hereafter UST (0.5 mm)). The experiment using the UST (0.5 mm) was conducted under the same conditions as that using the UST (2.0 mm). The particle concentration was set to 5% VFP and 10% VFP, and the measurement performance was compared. Figure 14 shows the measurement results of the flow velocity at 5% VFP and 10% VFP. At 5% VFP, the UST (2.0 mm) underestimated the flow velocity by 36%, whereas the UST (0.5 mm) underestimated it by 6.9%. At VFP 10%, the UST (2.0 mm) underestimated the flow velocity by 65%, whereas the UST (0.5 mm) underestimated it by 24%. Narrowing the measurement area reduced the degree of underestimation. This can be attributed to the increased effect of the directionality of a UST and the reduced influence of spatial averaging. However, given the 32% underestimation at 10% VFP, measurement at 40% VFP close to whole blood, would be difficult even with the UST (0.5 mm). Therefore, verification with a UST having an even smaller measurement area is desired to measure particle phantoms close to whole blood in the low-frequency range.

Figure 14.

Comparison of the flow velocities measured with the two probes with different focal diameters for the different concentrations at (a) 5% VFP, (b) 10% VFP. One UST was with a focus diameter of 2.0 mm (UST (2.0 mm)), and the other with 0.5 mm (UST (0.5 mm)). The degree of the underestimate was consistently smaller for the UST (2.0 mm) compared to that for the UST (0.5 mm).

4.3. Measurements Based on the PW Method

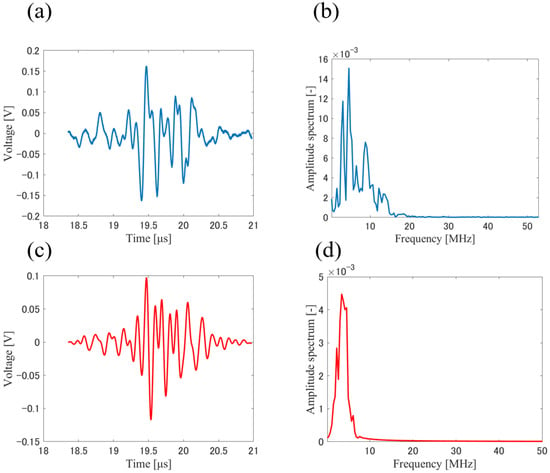

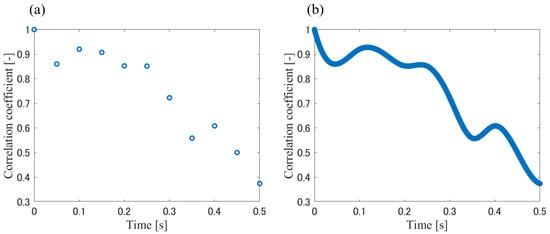

Figure 15a shows the waveform obtained by interpolating the signal with zero displacement 1000 times using spline interpolation. The frequency spectrum is shown in Figure 15b. The weighted average frequency was 9.7 MHz. A bandpass filter was applied by setting the transmission frequency range to ±2.5 MHz around the weighted average frequency. Figure 15c shows the bandpass filtered PA signals. The application of the filter made the PA signal closer to a single wavelength. Figure 15d presents the frequency spectrum of the filtered signal. The weighted average frequency of the bandpass filtered signal was 7.6 MHz, which was defined as the frequency of the PA wave . Figure 16a shows a plot with the horizontal axis representing the time interval when the pulsed laser irradiation was applied at 20 Hz, and the vertical axis representing the normalized convolution integral values for each displacement. Figure 16b shows the result of applying spline interpolation 1000 times to Figure 16a. The angle between the flow tube and probe is . The flow velocity v can be expressed using the PA wave frequency, Doppler frequency, and angle between the flow tube and the probe. Figure 15a shows the waveform extracted by averaging the signal with zero displacement ten times and interpolating it 1000 times using a spline interpolation. The frequency spectrum is shown in Figure 15b. The weighted average frequency was 9.7 MHz. A bandpass filter was applied by setting the transmitting frequency range to ±2.5 MHz around the weighted average frequency. Figure 15c shows the PA signal after the filtering. The application of the bandpass filter resulted in the PA signal approaching a single wavelength. Figure 15d presents the frequency spectrum after the filtering. The weighted average frequency after the filtering was 7.6 MHz, which was defined as the frequency of the PA wave . Figure 16a shows a plot with the horizontal axis representing the time interval when the pulsed laser irradiation was applied at 20 Hz, and the vertical axis representing the integral values of the normalized convolution for each displacement. Figure 16b shows the result of applying spline interpolation 1000 times to Figure 16a. Assuming that the particle moves 10 m during a single pulsed irradiation, the estimated velocity is 0.2 mm/s. If the particle moves 20 m and 30 m, the estimated velocities are 0.4 mm/s and 0.6 mm/s, respectively. These values are used as the theoretical flow velocities. From Figure 16, the times at which the CC value reached 0.5 or 0 were obtained. These times correspond to 1/8 or 1/4 of the wave period, and their eightfold or fourfold reciprocals were defined as the Doppler frequency. The angle between the flow tube and probe is . The flow velocity v can be expressed using the PA wave frequency, Doppler frequency, and angle between the flow tube and the probe as

Figure 15.

Typical time signals and their frequency spectra obtained in the experiment, (a) extracted time signal, (b) frequency spectrum of the time signal shown in (a), (c) bandpass filtered time signal shown in (a), (d) frequency spectrum of the bandpass filtered time signal shown in (c).

Figure 16.

Comparison of the normalized cross-correlation distributions, (a) before the interpolation, (b) after the interpolation.

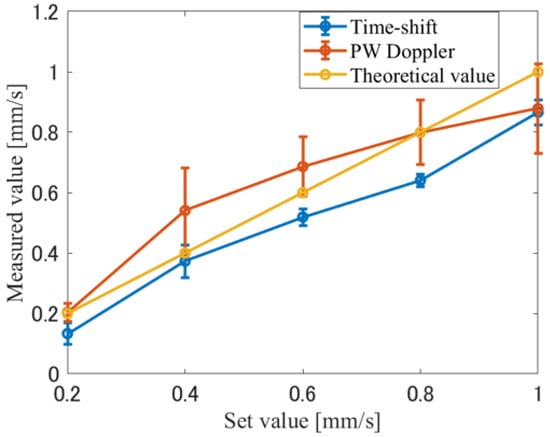

This corresponds to the result for a theoretical flow velocity of 0.2 mm/s. The measured results obtained using the time-shift method are compared with the theoretical values. The measurement results are shown in Figure 17. Each estimated flow velocity was measured ten times, and the average value was plotted. The standard deviations were shown as error bars. From the comparison in Figure 17, the time-shift method showed a bias from to compared to the theoretical flow velocity, while the PW Doppler method exhibited a bias ranging from to . Both the time-shift method and the PW Doppler method generally followed the theoretical values.

Figure 17.

Comparison of the measurement results of the time-shift and PW Doppler methods with the theoretical values. The results of both methods are consistent with the theoretical values. The time-shift method shows a bias from to , whereas the PW Doppler method shows a bias from to .

5. Conclusions

We investigated the performance of the PA measurement of flow velocity at the different VFPs using an ultrasound transducer in the low-frequency range. The target VFPs were set to 1% VFP, 5% VFP, and 10% VFP dispersed in fluid flow in a silicone tube. The numerical analysis was performed on the directional and non-directional characteristics of a UST. In the experiment, the measurement of the flow velocities was conducted with the set velocities ranging from 20 mm/s to 90 mm/s. The two different methods were employed for the velocity measurements. The time-shift method is based on the CC of a pair of PA signals, whereas the PW Doppler method relies on the Doppler frequency shift of the PA signals. The following conclusions are drawn:

- The directivity characteristics of USTs was revealed with the numerical analysis. For a directional UST, the WAFS of the PA signal did not shift into the low-frequency direction if the inter-particle distance did not move toward lower frequencies. In other words, directivity USTs can discriminate individual particles in a heterogeneous target, regardless of the axial spatial resolution. On the other hand, for an omnidirectional UST, the WAFS of the PA signal shifted toward lower frequencies when the inter-particle distance was smaller than the lateral spatial resolution. This is considered to be due to spatial averaging and smoothing of variations between adjacent particles.

- From the results at 1% VFP, the time delay was 3 ns. The time delay was consistent in the order with the value of 1 ns predicted from the CRLB, indicating the lower bound of the jitter. The jitter includes factors such as electronic noise and uncorrelated physical processes.

- In the flow velocities measured at the different VFPs, the bias against the set velocity was 5.7% at 1% VFP, −36% at 5% VFP, and −65% at 10% VFP for the time-shift method. There was a tendency to underestimate the flow velocity with an increase in the VFP. The underestimation was not attributed to the penetration depth of the incident light based on the simulation of the attenuation of the irradiated light in the tube. The effect of light attenuation is minimal because the weight-averaged flow velocity exhibited linear variation with the VFP.

- On the effect of UST characteristics on the measurement, the inter-particle distance was smaller than the spatial resolution at 10% VFP, which resulted in the dominance of low-frequency components. With the increase of the VFP, the spatial averaging hindered the ability to distinguish individual particles, leading to an underestimation of the flow velocity for the time-shift method. Hence, an omnidirectionality of the UST was predominant in the high VFP conditions.

- In the measurement with a UST (2.0 mm), the bias relative to the set flow velocities was −36% at 5% VFP and −65% at 10% VFP for the time shift method. The reduction in the degree of underestimation was confirmed when using a focused UST (0.5 mm), as the stronger influence of the UST’s directionality led to a smaller measurement volume. Biases of −6.9% at 5% VFP and −24% at a 10% VFP were obtained.

- In the displacement measurement experiment, both the time-shift method and the PW Doppler method generally agreed with the theoretical values.

These conclusions revealed that PAF using a 10 MHz UST can be performed with a focal diameter of around 2 mm at up to 1% VFP. However, at concentrations of 5% VFP or higher, the measurement performance deteriorated rapidly because of the effect of the omnidirectionality of a UST. Nevertheless, in the displacement measurement using the PW Doppler method, the results generally followed the theoretical values. The concentration of the particle suspension remained lower than that of actual blood. Therefore, future work should involve flow velocity measurements at concentrations closer to that of blood to investigate the effect of higher particle concentrations on measurement accuracy in realistic environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.T. and K.S.; Methodology, H.T., T.K. and K.S.; Validation, H.T. and T.K.; Numerical analysis, T.K.; Experiments, H.T. and T.K.; Writing—Original draft, H.T. and K.S.; Writing—Review and editing, K.S.; Supervision, K.S.; Funding acquisition, K.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The redpresent study was entirely supported by the internal funding of the SIT.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of the present study are available upon reasonable request from the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declare no financial or personal interests related to the results of the present study.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AR | Acoustic resolution |

| CC | Cross-correlation |

| CRLB | Cramér-Rao lower bound |

| FFT | Fast Fourier transform |

| OR | Optical resolution |

| PAF | Photoacoustic flowmetry |

| PA | Photo-acoustic |

| PD | Photo detector |

| PW | Pulsed wave |

| SNR | Signal-to-noise ratio |

| UST | UltraSound transducer |

| VFP | Volume fraction of particles |

| WAFS | Weight-averaged frequency spectrum |

| YAG | Yttrium aluminum garnet |

References

- Singh, M.S.; Jiang, H. Estimating both direction and magnitude of flow velocity using photoacoustic microscopy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2014, 104, 253701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satomura, S. Ultrasonic Doppler method for the inspection of cardiac functions. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1957, 29, 1181–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabo, T.L. Diagnostic Ultrasound Imaging: Inside Out, 2nd ed.; Academic Press: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Micheels, J.; Alsbjorn, B.; Sorensen, B. Laser Doppler flowmetry. A new non-invasive measurement of microcirculation in intensive care? Resuscitation 1984, 12, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajan, V.; Varghese, B.; van Leeuwen, T.G.; Steenbergen, W. Review of methodological developments in laser Doppler flowmetry. Lasers Med. Sci. 2009, 24, 269–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manohar, S.; Razansky, D. Photoacoustics: A historical review. Adv. Opt. Photonics 2016, 8, 586–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.H. Photoacoustic Imaging and Spectroscopy; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Shiina, T. Novel Medical Imaging Technology by Integration of Optics and Ultrasound. J. Jpn. Soc. Laser Surg. Med. 2013, 33, 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Berg, P.J.; Daoudi, K.; Steenbergen, W. Review of photoacoustic flow imaging: Its current state and its promises. Photoacoustics 2015, 3, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunker, J.; Beards, P. Velocity measurements in whole blood using acoustic resolution photoacoustic Doppler. Biomed. Opt. Express 2016, 7, 2789–2806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer-Marschallinger, J.; Berer, T.; Grun, H.; Roitner, H.; Reitinger, B.; Burgholzer, P. Broadband high-frequency measurement of ultrasonic attenuation of tissues and liquids. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 2012, 59, 2631–2645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, M.; Motizuki, T. Ultrasound Diagnostic Equipment; Corona Publishing: redBunkyo, Tokyo, Japan, 2002; pp. 120–154. [Google Scholar]

- Godefroy, G.; Arnal, B.; Bossy, E. Full-visibility 3D imaging of oxygenation and blood flow by simultaneous multispectral photoacoustic fluctuation imaging (MS-PAFI) and ultrasound Doppler. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 2961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Olick-Gibson, J.; Khadria, A.; Wang, L.V. Photoacoustic vector tomography for deep haemodynamic imaging. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2024, 8, 701–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rietberg, M.T.; Gröhl, J.; Else, T.R.; Bohndiek, S.E.; Manohar, S.; Cox, B.T. Artifacts in photoacoustic imaging: Origins and mitigations. Photacoustics 2025, 45, 100745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujinami, K.; Shirai, K. Performance evaluation of cross-correlation based photoacoustic measurement of a single object with sinusoidal linear motion. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 13202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treeby, B.E.; Cox, B.T. k-Wave: MATLAB toolbox for the simulation and reconstruction of photoacoustic wave fields. J. Biomed. Opt. 2010, 15, 021314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kay, S.M. Fundamentals of Statistical Processing, Volume I: Estimation Theory; Prentice-Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, W.F.; Trahey, G.E. A fundamental limit on delay estimation using partially correlated speckle signals. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 1995, 42, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Long, J.; Li, X.; Zhou, X.; Chen, L.; Qiu, C.; Jin, Z. Preparation of agar polysaccharides and biological activities and relationships of agar-derived oligosaccharides and monosaccharides: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 295, 139552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenspan, M.; Tschiegg, C.E. Speed of Sound in Water by a Direct Method. J. Res. Natl. Bur. Stand. 1957, 59, 249–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, P.S.; Carhart, R.R. The absorption of sound in suspensions and emulsions. I. Water fog in air. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1953, 25, 553–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allegra, J.R.; Hawley, S.A. Attenuation of sound in suspensions and emulsions: Theory and experiments. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1972, 51, 1545–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krieger, I.M.; Dougherty, T.J. A mechanism for non-Newtonian flow in suspensions of rigid spheres. Trans. Soc. Rheol. 1959, 3, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayerhofer, T.G.; Pahlow, S.; Popp, J. The Bouguer-Beer-Lambert law: Shining light on the obscure. ChemPhysChem 2020, 21, 2029–2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).