Abstract

Rapid advancements in surveying technology have necessitated the development of more accurate and efficient tools. Leica Geosystems AG (Heerbrugg, Switzerland), a leading provider of measurement and surveying solutions, has initiated a study to enhance the capabilities of its GNSS INS-based surveying systems. This research focuses on integrating the Leica GS18 I GNSS receiver and the AP20 AutoPole with a Time of Flight (ToF) camera through sensor fusion. The primary objective is to leverage the unique strengths of each device to improve accuracy, efficiency, and usability in challenging surveying environments. Results indicate that the fused AP20 configuration achieves decimetre-level accuracy (2.7–4.4 cm on signalized points; 5.2–20.0 cm on natural features). In contrast, the GS18 I fused configuration shows significantly higher errors (17.5–26.6 cm on signalized points; 16.1–69.4 cm on natural features), suggesting suboptimal spatio-temporal fusion. These findings confirm that the fused AP20 configuration demonstrates superior accuracy in challenging GNSS conditions compared to the GS18 I setup with deviations within acceptable limits for most practical applications, while highlighting the need for further refinement of the GS18 I configuration.

1. Introduction

An “imaging rover” is a special portable device with position and vision sensors to record and process visual data about an environment. In the surveying context, it is typically an integrated product of a GNSS receiver (Global Navigation Satellite Systems) with an inertial measurement unit (IMU) and one or more cameras. The GNSS receiver provides accurate positioning information from satellites, and the IMU and cameras are incorporated to further enhance accuracy, especially in challenging GNSS areas. The camera can also be used to take images of the environment, which can then be used to measure hard-to-reach points in that area. As GNSS faces problems in urban or indoor environments, an inertial measurement unit (IMU) is also used to complement GNSS in the rover by providing high-frequency motion data in the event of signal dropouts. In addition, the IMU provides the orientation data required to estimate a complete six-degree-of-freedom (6DoF) pose, utilizing its integrated accelerometer and gyroscope components [1]. This combination of IMU with computer-aided integration algorithms and coupled with GNSS is referred to as a GNSS inertial navigation system (GNSS/INS) [2]. Research in mobile mapping and SLAM has demonstrated that integrating cameras or time-of-flight sensors with GNSS/INS units can significantly reduce drift and improve near-range accuracy in environments with partial satellite visibility [3,4,5,6]. Although most of these works focus on vehicle-mounted or robotic systems, the same principles apply to compact imaging rovers, where synchronized visual and inertial data can support short-range 3D reconstruction and improve robustness during GNSS interruptions. Hence, imaging rovers provide a robust positioning solution for diverse surveying and mapping environments, from Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) to ground surveying equipment [7]. For automotive and mobile mapping applications, this solution is versatile and is already being used in several studies [7,8,9] and devices already available in the market, such as Trimble MX7 [10], RIEGL VZ-400i [11], ViDoc [12]: an add-on to a smartphone that has LiDAR, 3D Image vector [13], Phantom 4 RTK [14], and others.

Although INS for mobile mapping applications is not new, this concept is developing significantly for ground-based surveying since 2017. The concept was first proposed by [15] and then by [16]. Following this, Leica Geosystems AG (Heerbrugg, Switzerland) introduced the GS18 I, a GNSS sensor together with a 1.2 MP camera built-in that enables visual positioning (allowing point measurement in captured images without pole straightening) [17]. Following Leica Geosystems AG, some other GNSS rovers offering visual positioning such as vRTK [18], INSIGHT V1 [19] and RS10 [20] also came to the market. Various performance studies have shown that the GS18 I performs consistently well in terms of survey-grade accuracy and reliability across a range of environments [21,22]. Currently, there are limited equivalent systems combining totalstation tracking with integrated inertial and imaging components. However, when using the GS18 I for image measurements, some conditions must be observed [22]. For example, the GS18 I must receive sufficient GNSS signals throughout the measurement. If the GNSS satellite tracking is lost, the acquisition will automatically stop. If visual positioning is required, it should be avoided in darkness or when the camera is facing the sun, as not enough detail can be detected from the captured images to correlate them. In addition, the object needs to have a non-repetitive texture to allow the Structure from Motion (SFM) algorithm [23] to function properly. SFM is a photogrammetric technique that reconstructs three-dimensional structures from two-dimensional image sequences, relying on distinct visual features to estimate camera motion and object geometry. Alongside, for best results, images are captured from 2–10 m away. Distances less than 2 m may cause blurring due to fixed focus, while distances over 10 m reduce accuracy due to low resolution of the camera. Images taken outside this range may yield less precise measurements or may prevent point placement altogether.

In addition to complementing GNSS solutions, Leica Geosystems AG has introduced the AP20 AutoPole, a tiltable pole to complement totalstation workflows in 2022 [24]. Totalstations excel in providing precise angle measurements, integrating angle and distance data in one device, and operating effectively where GNSS signals are unreliable or obstructed [25]. The AP20 automatically adjusts the inclination and height of the pole, eliminating the need to level the pole and separately record the height of the pole during surveying work. The AP20 also has integrated target identification (TargetID), which helps to ensure that the correct target is detected even if there are obstacles such as people or vehicles in the vicinity that could cause the totalstation to lose sight of the target. Currently, there are no direct equivalents from other manufacturers that offer the same combination of features specifically for totalstations. However, the survey equipment industry is rapidly evolving, and there is a need to further enhance the functioning and accuracy of these instruments.

For enhanced visual positioning and measurement accuracy, an idea could be to integrate a Time of Flight (ToF) camera in the GS18 I and AP20. ToF cameras provide precise depth measurements by calculating the time it takes for light to travel to an object and back [26]. This depth information enables real-time 3D point cloud generation. ToF cameras can also work well in low light or even complete darkness since they provide their own illumination. The accuracy of ToF cameras exceeds any other depth detection technology, with the exception of structured light cameras, and can provide an accuracy of 1 mm to 1 cm depending on the operating range of the camera [27]. They are significantly more compact, speedy and have lower power consumption than other depth sensing technologies [27]. Combining real-time 3D data from a ToF camera with GNSS and tilt measurements could therefore address the challenges associated with GNSS limitations while extending the measurement range and improving visibility in low-light/dark conditions. It might also increase the operator’s safety and the measurement accuracy, especially for single point measurements without line of sight, or increase efficiency by speeding up data collection by reducing time spent in the field. This improved ease of use could also provide a competitive advantage over other products on the market.

Therefore, the primary aim of this work is to investigate the use of a ToF camera using the Leica GS18 I and the AP20 as examples. In this regard, the Blaze 101 ToF camera from Basler AG was selected due to its performance data and potential suitability for outdoor surveying applications [28].

While prior research has explored GNSS-INS integration with passive cameras [7,8,9,15,16] and ToF cameras have been used in robotics [26], this study presents the first systematic evaluation of a ToF-camera-enabled Multi-Sensor-Pole (MSP) for terrestrial surveying in combination with both, a totalstation or a GNSS-receiver. The integration of GS18 I with the Blaze camera is termed as the “GS18 I-MSP”, while the integration of AP20 with the Blaze camera is called the “AP20-MSP” in the text. Ref. [29] did something similar to our GS18 I-MSP and were able to achieve around 5 cm error on distinct structures like walls. Unlike other existing imaging rovers that rely on Structure from Motion (SFM) with passive 2D cameras (e.g., GS18 I’s built-in camera [17]), the MSP leverages direct depth sensing, enabling operation in low-light and texture-less environments where SFM fails. Critically, we compare two fundamentally different hardware configurations: GNSS-INS-based (GS18 I-MSP) vs. totalstation-coupled (AP20-MSP), revealing a significant performance divergence (25 cm vs. 3 cm absolute errors) that informs optimal sensor selection for specific field conditions. This comparative analysis, coupled with hardware-synchronized triggering and open-source calibration protocols, constitutes the primary novelty beyond mere component integration.

The structure of this case study is as follows: Section 2 covers a brief overview of the equipment and technologies used in this study. Section 3 presents the methodology for the integration process and the testing procedures to evaluate the performance of the integrated system. Section 4 sets forth the results and findings of the accuracy and performance tests, including specific metrics and comparative data in various use case examples. Section 5 discusses about the challenges and solutions associated with this work. Finally, Section 5 summarizes the key outcomes of the case study and implications for future work.

2. Case Description: Materials and Technologies

In surveying, precision and efficiency are crucial. This case study explores a project that integrates a GNSS receiver (GS18 I by Leica Geosystems AG), an intelligent surveying pole (AP20 by Leica Geosystems AG), and a ToF camera (Blaze 101 by Basler AG (Ahrensburg, Germany)) to enhance GNSS-INS based surveying. The following sections detail the specific instruments and the technologies used in these devices to achieve the project objectives.

2.1. Leica GS18 I GNSS Receiver

The Leica GS18 I is an advanced GNSS receiver designed for precise geodata and surveying tasks. It supports multiple satellite systems such as GPS, GLONASS, Galileo and BeiDou with 555 channels and multi-frequency capabilities. The device can update positions at a rate of up to 20 Hz, ensuring real-time data collection. It incorporates high-precision Real Time Kinematic (RTK) [30] with 8 mm + 1 ppm horizontal and 15 mm + 1 ppm vertical accuracy. The receiver works with the Leica Captivate software (v 5.10) and offers various communication options such as Bluetooth, Wi-Fi, and USB as well as an optional UHF radio. It is equipped with a rugged, weatherproof design, an advanced GNSS antenna and a lithium-ion battery with up to 16 h of operation.

The GS18 I also incorporates an Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU) for tilt compensation, which does not require calibration and is immune to magnetic disturbances. This feature allows surveyors to measure hard-to-reach points without the need for precise levelling of the pole.

One of its standout features is the ability to perform visual positioning through its built-in camera via Structure from Motion (SfM) algorithms [23]. This allows for accurate point measurements from images, even in environments where direct GNSS measurements are challenging. The built-in camera is an Arducam AR0134, 1.2 MP sensor with a resolution of 1280 × 960 pixels (px) at a size of 3.75 µm and is equipped with a Bayer filter and a global shutter. The Field of View (FoV) of the camera is 80 degrees in horizontal and 60 degrees in vertical direction. The lens has a focal length of 3.1 mm, resulting in a ground scanning distance (GSD) of 12 mm at 10 m [17]. A quick depiction of GS18 I is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Leica GS18 I: (a) top view. (b) front view with the built-in camera. (c) side view showing the battery compartment and the services panel. (Source: [17]).

The orientation of GS18 I is measured at 200 Hz by its integrated INS [31]. This orientation is important in estimating the position and orientation (pose) of the built-in camera images in a global coordinate system. The INS also generates a synchronization pulse that triggers both the built-in camera and the external Blaze ToF camera, ensuring temporal alignment of image acquisition across both sensors in the GS18 I-MSP setup. The details of this trigger process will follow in Section 3.4.

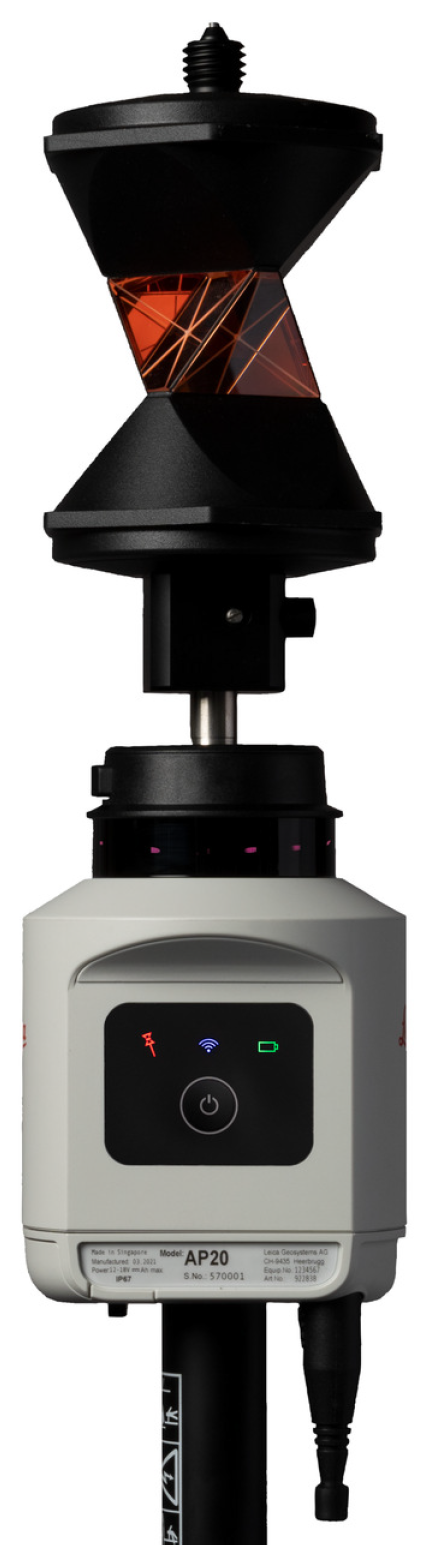

2.2. Leica AP20 AutoPole

The AP20 is a high-tech version of a surveying pole that provides a vertical reference point for measurements (Figure 2). A prism is attached to the top of the AP20, which reflects the laser beam emitted by a totalstation towards it. The totalstation uses reflected laser signals not only to measure the distance between the AP20 and itself, but also to detect and continuously track the prism using Leica’s ATRplus (automatic target recognition and tracking technology) as the surveyor moves the pole around the site. Unlike traditional survey poles, the AP20 automates several tasks that traditionally require manual input, thereby increasing efficiency and reducing errors. For instance, its tilt compensation allows surveyors to measure points at any angle up to 180° without needing to level the pole. This capability is especially useful for measuring hard-to-reach points, such as building corners or objects under obstacles [24]. The AP20 also includes automatic pole height measurement, eliminating the need for manual height adjustments. The device operates in a wide temperature range from −20 °C to +50 °C and is protected against dust and water with an IP66 rating. Technologically, the AP20 uses an Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU) for precise tilt measurements and Bluetooth/radio frequency for wireless connectivity [24].

Figure 2.

Leica AP20 AutoPole with Leica GRZ4 360° prism attached. (Source: [24]).

It is worthwhile to mention here that a special AP20 from Leica Geosystems AG was provided for this case study. In contrast to the standard AP20, this special AP20 could be powered over the integrated USB-C connector and read IMU and TPS data directly from the onboard ROS-Publisher over the USB 2 interface. ROS (Robot Operating System) is an open-source software framework that provides a set of tools, libraries, and conventions for developing complex robotic systems and facilitating communication between different software components [32]. More details are provided in Section 3.2. Similarly to the GS18 I, the built-in IMU of AP20 also generates a trigger pulse, which triggers the Blaze ToF camera in the AP20-MSP setup; see Section 3.4.

2.3. Basler Blaze 101 ToF Camera

The Basler Blaze 101 is a Time-of-Flight camera that provides high-precision depth sensing and 3D imaging [28]. It features a resolution of 640 × 480 pixels and can capture up to 30 frames per second, delivering detailed depth information with an accuracy of ±5 mm within a range of 0.3–5.5 m. The operating wavelength is 940 nm. Additionally, the camera has an effective measurement range of 0–10 m. However, due to the nature of ToF technology, there is an ambiguity issue where objects beyond 10 m may be detected as being closer (e.g., an object at 24 m might be detected as 4 m away). The Blaze 101 supports multiple output formats, including depth map, intensity image, and point cloud data. It comes with an SDK (Software Development Kit) for Windows and Linux, and provides interfaces such as Gigabit Ethernet and digital I/O. The camera’s compact size of 100 × 65 × 60 mm and its IP67 housing make it suitable for industrial environments. Additionally, it offers features like multi-camera operation and HDR mode for challenging lighting conditions (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Basler Blaze 101 Time of Flight camera with front and back views. (Source: [28]).

The Blaze 102 ToF camera is another variant of the ToF cameras from Basler AG [33]. This camera shares many similarities with the Blaze 101, including resolution, frame rate, interface, working range, and the ability to generate 2D and 3D data simultaneously. However, the key difference is that Blaze 102 operates at 850 nm, while the Blaze 101 uses 940 nm. The Blaze 101 offers superior immunity to ambient light compared to the Blaze 102 camera. For this case study, the behaviour of both cameras was tested by conducting various tests particularly focusing on accuracy, distance, and environmental factors. To check for interference, two Blaze 101 and 102 cameras were also used together. The details of these tests are not discussed here as they would go beyond the scope of this paper. However, it turned out that the Blaze 101 is not only more suitable for outdoor use in bright sunlight, but also performs comparably to Blaze 102 indoors or in cloudy conditions. Furthermore, using two Blaze 101 cameras instead of one slightly increased the FoV. However, saving data with two cameras required more computer processing power and storage. Therefore, for the rest of this study, only Blaze 101 was used for the MSP testing.

3. Methodology

This section first presents a functional measurement setup of the Multi-Sensor-Pole. Then the relevant steps to assemble the components used in the functional model are described. Later, details about data processing and analysis are explained.

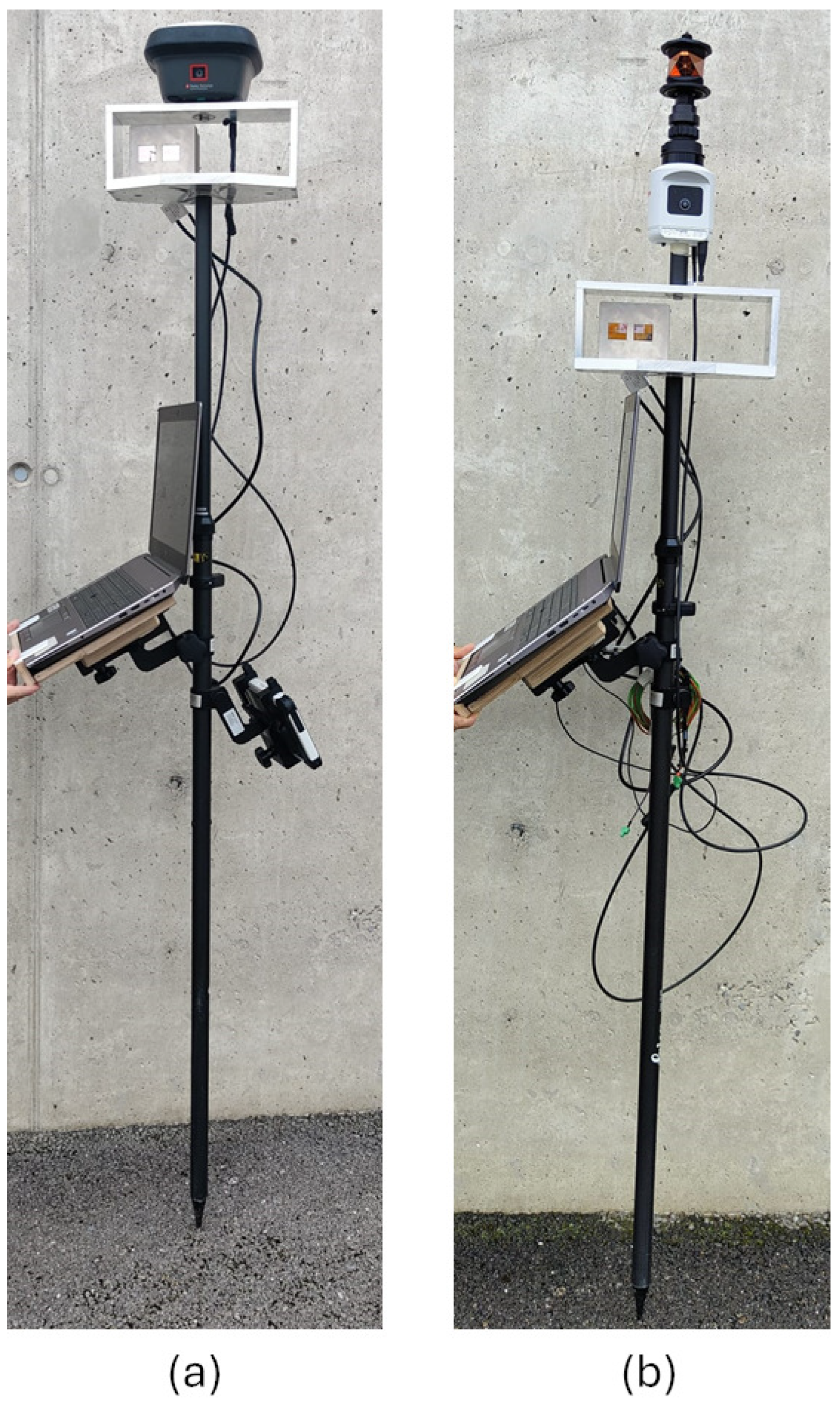

3.1. Functional Model

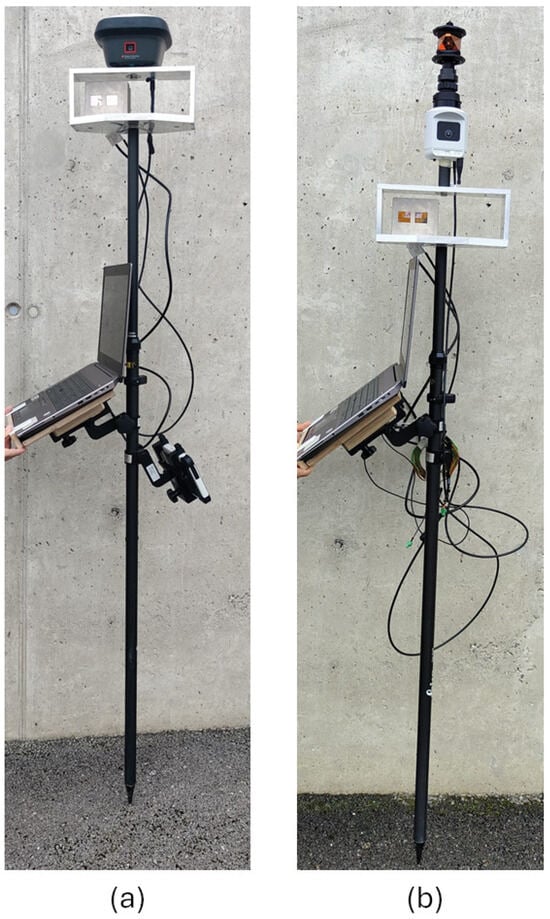

The functional setup of the Multi-Sensor-Pole is shown in Figure 4 where the two Blaze 101 cameras are mounted inside a steel bracket on a vertical pole. The pole provided stability and allowed the setup to be positioned at a desired height. The topmost device could be the GS18 I or AP20. A laptop and the CS30 control unit for the GS18 I are also attached to the pole below the steel bracket for real-time data acquisition, monitoring, and control of the sensors’ behaviour. The laptop is connected to the sensors via cables, which are explained in the next Section 3.2.

Figure 4.

The functional model of Multi-Sensor-Pole with GS18 I (a) and AP20 (b). Both models contain a Blaze 101 ToF camera and a custom mounting bracket for the laptop. The prism used is the Leica MRP122.

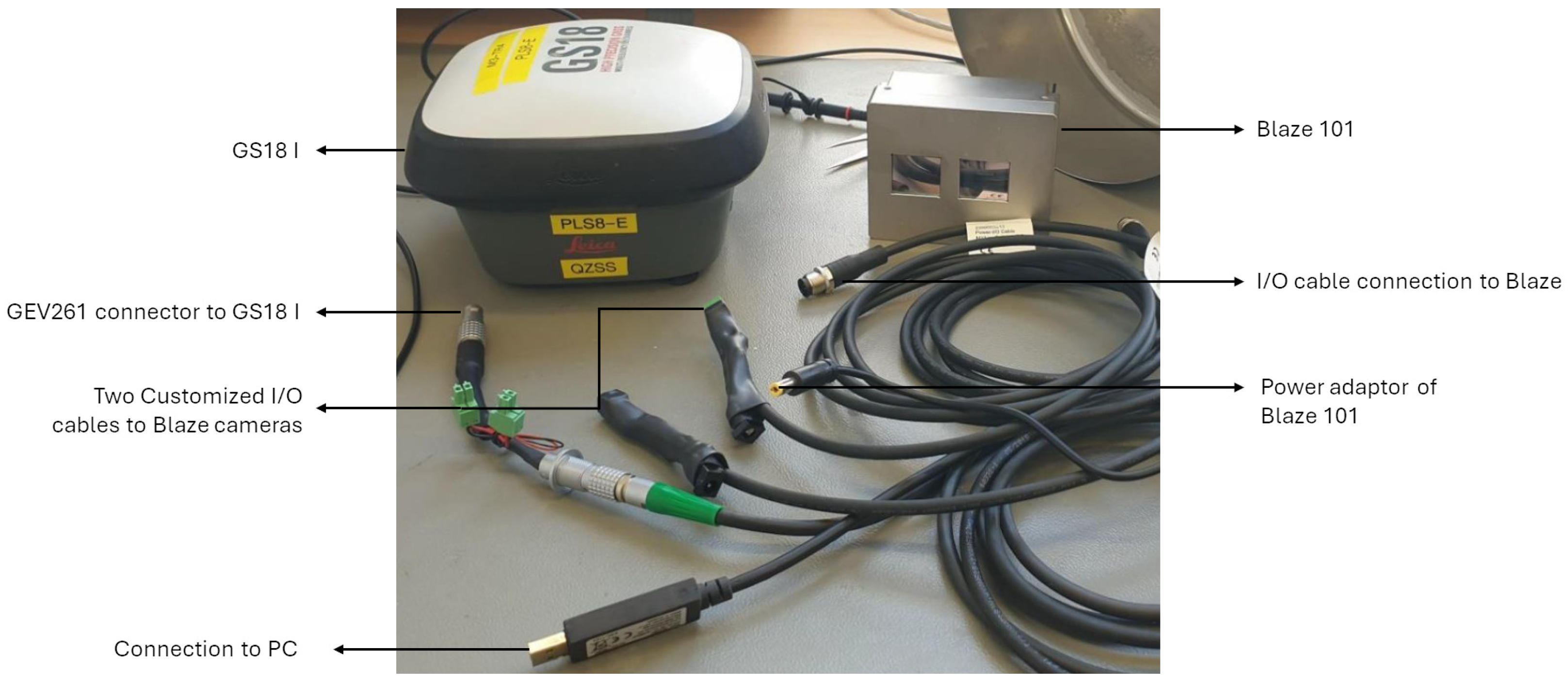

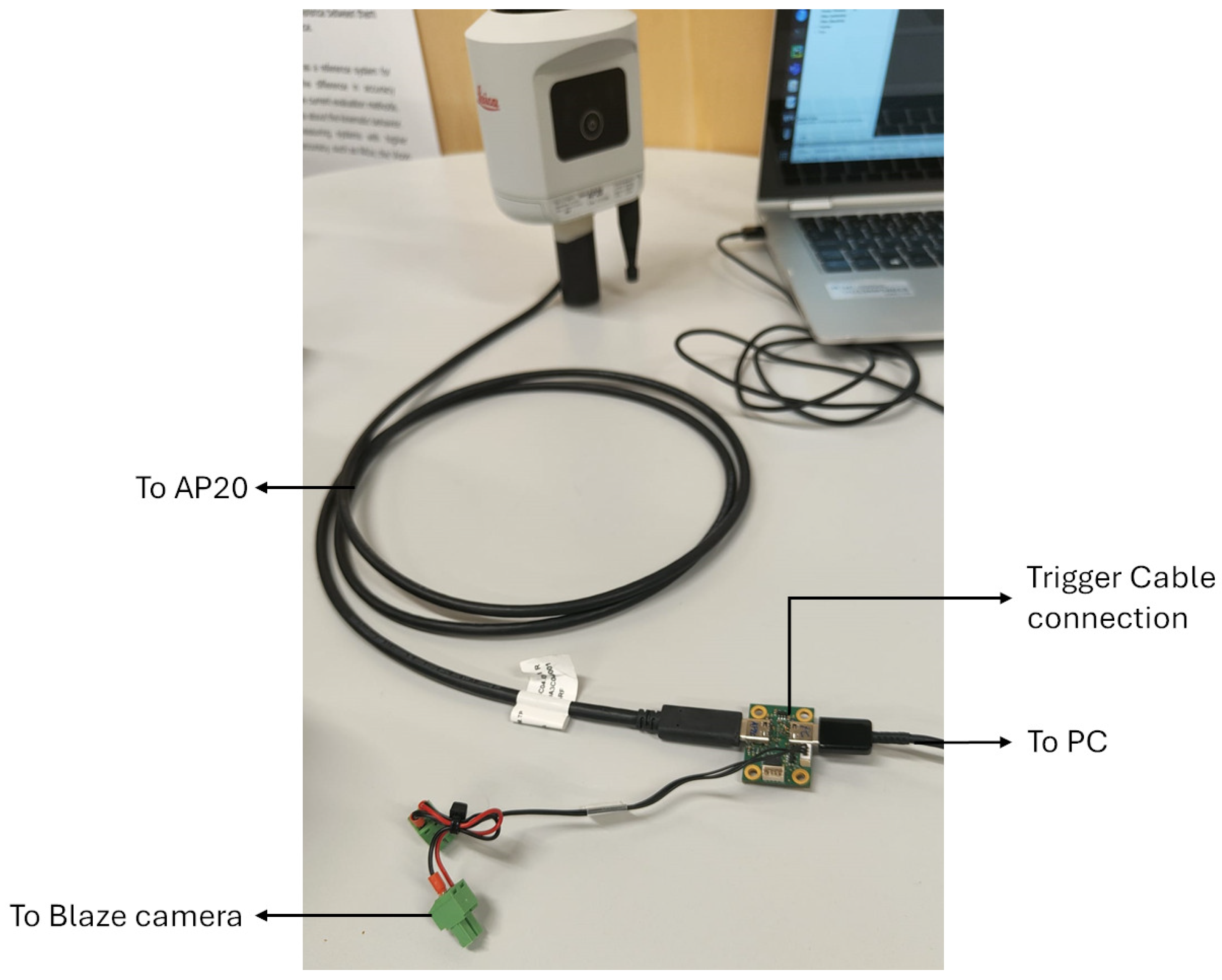

3.2. I/O Connections for Powering and Triggering

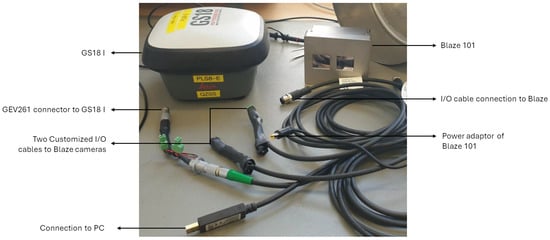

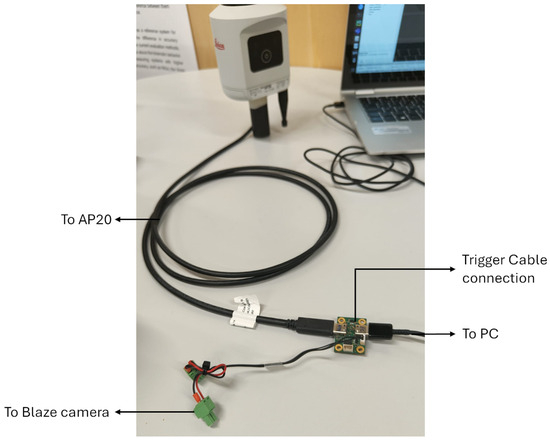

The GS18 I was powered by an internal battery (GEB333). The Blaze cameras came with a 24 V/60 W power supply and an adjustable M12, M, 8-Pin/Open I/O cable from Basler AG. This cable has an 8 pin open ended connector that can be customised for powering the cameras and to allow an external trigger operation. Accordingly, Leica Geosystems AG provided two custom-made cables for powering and triggering the Blaze camera via the GS18 I and AP20. An overview of these connections is given in Figure 5 for the connection with GS18 I and in Figure 6 for the connection with AP20.

Figure 5.

The customised I/O cables provided by Leica Geosystems AG to trigger Blaze cameras by the GS18 I.

Figure 6.

The AP20 can be powered over a USB-C connector besides providing the trigger to the Blaze camera through the customized I/O cable provided by Leica Geosystems AG.

A detailed description for the Blaze connector’s pin numbering and assignments can be found at [28]. For data collection, a separate GigE M12, M, 8-pin/RJ45 data cable was also purchased from Basler AG.

3.3. Frame Grabber and the Portable Computer

The pylon Camera Software Suite allows all the necessary tools for easy integration and set-up of the Blaze ToF cameras through a single interface. The software is available for Windows, ARM-based, and AMD-based Linux systems. The “Blaze Viewer” and “pylon IP Configurator” that come in the pylon Camera Software Suite allow for setting up the triggering and configuring parameters of Blaze cameras through software. The “Blaze Viewer” can then be used as a frame grabber from Blaze ToF sensors. However, for this case study, the data were collected and stored in ROS bags [34]. A laptop (HP ZBook 15 G5 Intel i7 8850H 2.60 GHz 32 GB RAM 500 GB Linux) was used for continuous image buffering and acquisition from the Blaze camera.

3.4. Trigger Operation

The Blaze camera supports external hardware triggering through pin 6 (Line0). The trigger input accepts digital pulses with a logic-low level near 0 V and a logic-high level up to 24 V. A rising edge on this line triggers the acquisition of a single frame in the currently active operating mode. The trigger is always a FrameTrigger, i.e., it triggers the acquisition of a single frame in the current operating mode.

Both GS18 I and AP20 were used as an external trigger source for the Blaze camera using specially designed trigger cables as shown in Figure 5 and Figure 6. The INS of the GS18 I can provide a trigger signal of ±5 V from Pin 8 of its Port P1, which is enough to meet the Blaze camera specification for trigger. The emission of the trigger pulse from the GS18 I to the Blaze cameras must be activated via the GeoCOM command. The GeoCOM command interface is a specially designed communication protocol used by Leica totalstations and GNSS receivers to enable interaction with non-Leica software packages and external devices [35]. These commands can be used to configure the GS18 I for starting and stopping the trigger and for the image acquisition rate by the Blaze. For the GS18 I-MSP, the frame rate was set to 10 Hz, to avoid rapid memory filling, as the GS18 I can currently only store image data on its SD card for one minute.

For sending the trigger pulse from the AP20, specially designed AP20 Firmware was used, which generated a hardware trigger signal synchronized with the AP20 onboard IMU to trigger the frames of the Blaze. For this setup, the frame rate was set to 20 Hz, as it was currently not possible to reduce the frame rate of the IMU of the AP20. For optimal performance, the totalstation was placed at a distance of at least 5 m from the AP20 prism to obtain best position data.

3.5. Calibration

Camera calibration is the process of determining and adjusting a camera’s internal (intrinsic) and external (extrinsic) parameters to ensure accurate and distortion-free image capture. Generally, intrinsic parameters involve estimating the focal length of the camera in width and height, the optical centre, and the distortion coefficients, which quantitatively indicate lens distortion. On the other hand, the extrinsic parameters represent the camera’s position in the 3D scene: the rotation and translation. Combining these parameters in a camera Projection matrix (P) provides the necessary calibration of the camera.

For MSP configurations, the extrinsic calibration process was achieved using the Kalibr Toolbox [36]. This tool supports the “Multiple camera calibration”, which was required for calibrating the GS18 I’s camera with the Blaze camera in the GS18 I-MSP, based on the algorithm defined in [37]. Similarly, Kalibr also has a “Camera IMU calibration” tool defined in [38], which was required to calibrate the Blaze ToF camera with the IMU of AP20 in the AP20-MSP.

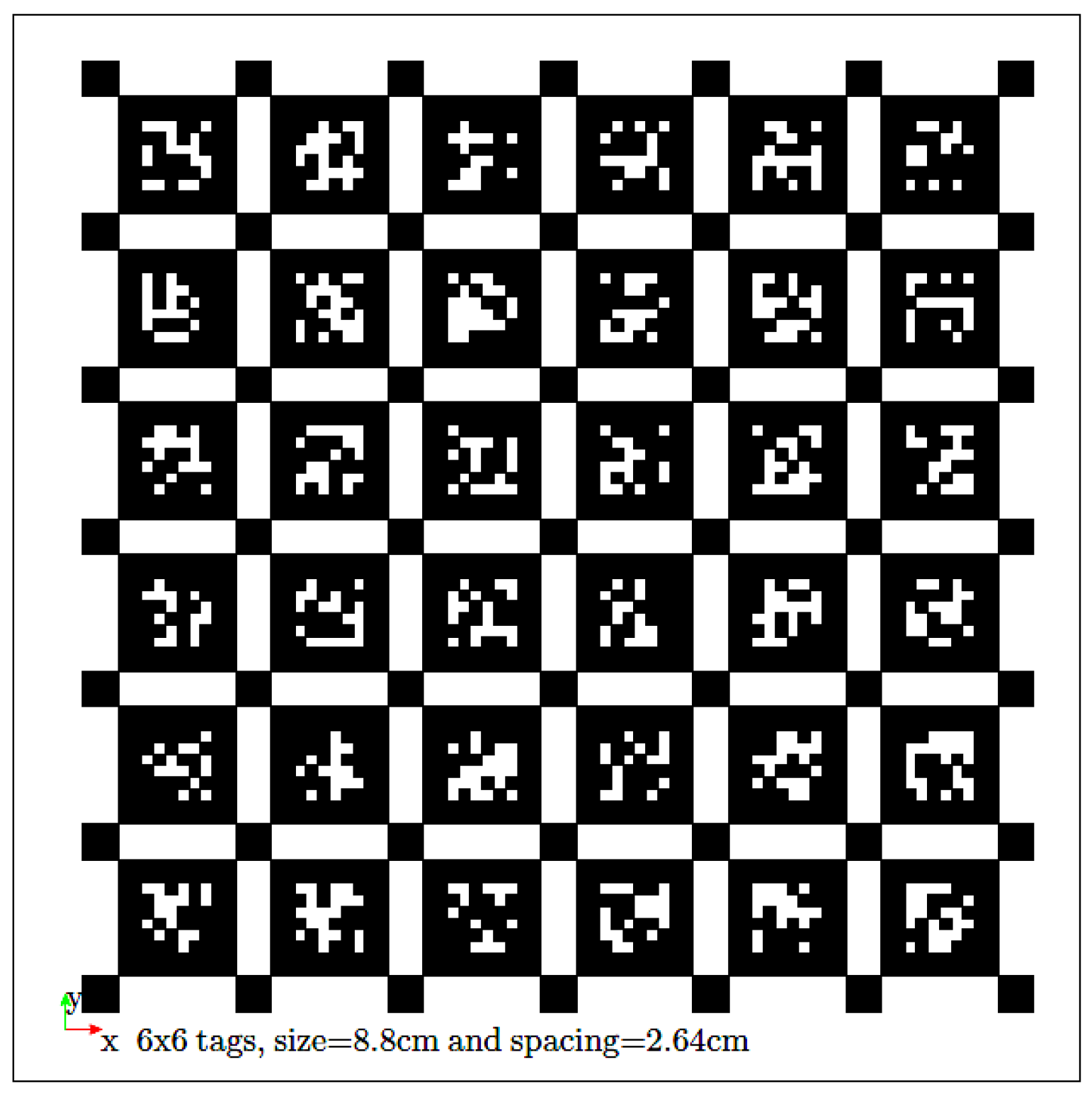

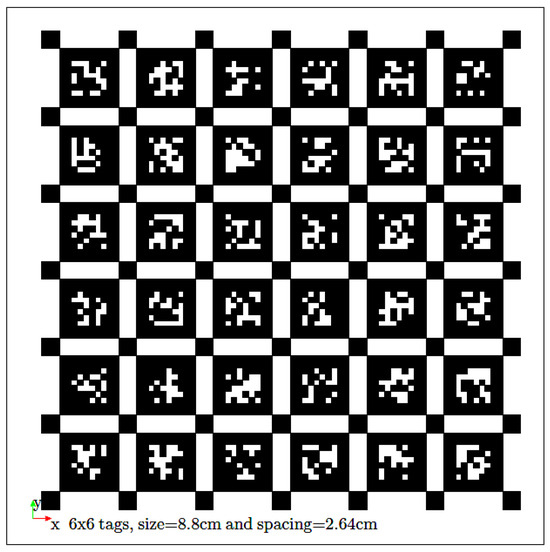

The MSP calibration process was carried out in accordance with the guidelines mentioned at the Kalibr website [36]. For using the “Multiple camera calibration” tool in Kalibr, the image data was provided as a ROS bag containing the image streams from the Blaze and the GS18 I. To capture the image data, the Aprilgrid Target provided by Kalibr (see Figure 7) was glued to a rigid board and moved around the GS18 I-MSP setup. For image synchronization, the Blaze camera was triggered by the GS18 I as explained in Section 3.4. The intensity images captured from the Blaze camera were captured in 8-bit .PNG format while the images from the GS18 I were in .JPG format. By using the“bagcreator” script provided in Kalibr, a ROS-version 1 bag was created on the sequence of acquired images. This bag was then used to run the Kalibr calibration commands, which in turn returned the camera Projection matrix with reference to the GS18 I and the Blaze separately. Table 1 summarizes the intrinsic, extrinsic, and temporal calibration parameters for both MSP configurations, obtained using the Kalibr toolbox.

Figure 7.

The Aprilgrid target (6 × 6) used for the calibration, size = 8.8 cm and spacing = 2.64 cm.

Table 1.

Calibration summary for AP20–MSP and GS18 I–MSP configurations (Kalibr output).

Similarly, for using the “Camera IMU calibration” tool, a ROS-version 1 bag was also recorded directly containing the IMU data from the AP20 and the intensity images from the Blaze. In this case, the calibration target (Figure 7) was fixed and the AP20-MSP setup was moved in front of the target to excite all IMU axes of the AP20. The output of running Kalibr commands on the recorded ROS bag gave the necessary transformation matrices (from IMU frame to the camera frame) and the time shift parameter indicating the temporal offset between the Blaze camera and the IMU of the AP20.

3.6. Data Collection and Storage

For the GS18 I-MSP, the image and pose data from the GS18 I were stored directly on the sd-card mounted inside it, while the images/point clouds from the Blaze were recorded in a ROS bag. To perform live measurements, live pose of the GS18 I can also be stored in ROS bag along with the Blaze.

For the AP20-MSP, data from the AP20 and the Blaze camera were captured and recorded in ROS bags. These ROS bags can replay the recorded data easily using the built-in ROS visualization tools like “rviz” and “rqt_bag” [34].

3.7. Test Areas and the Measurements Setup

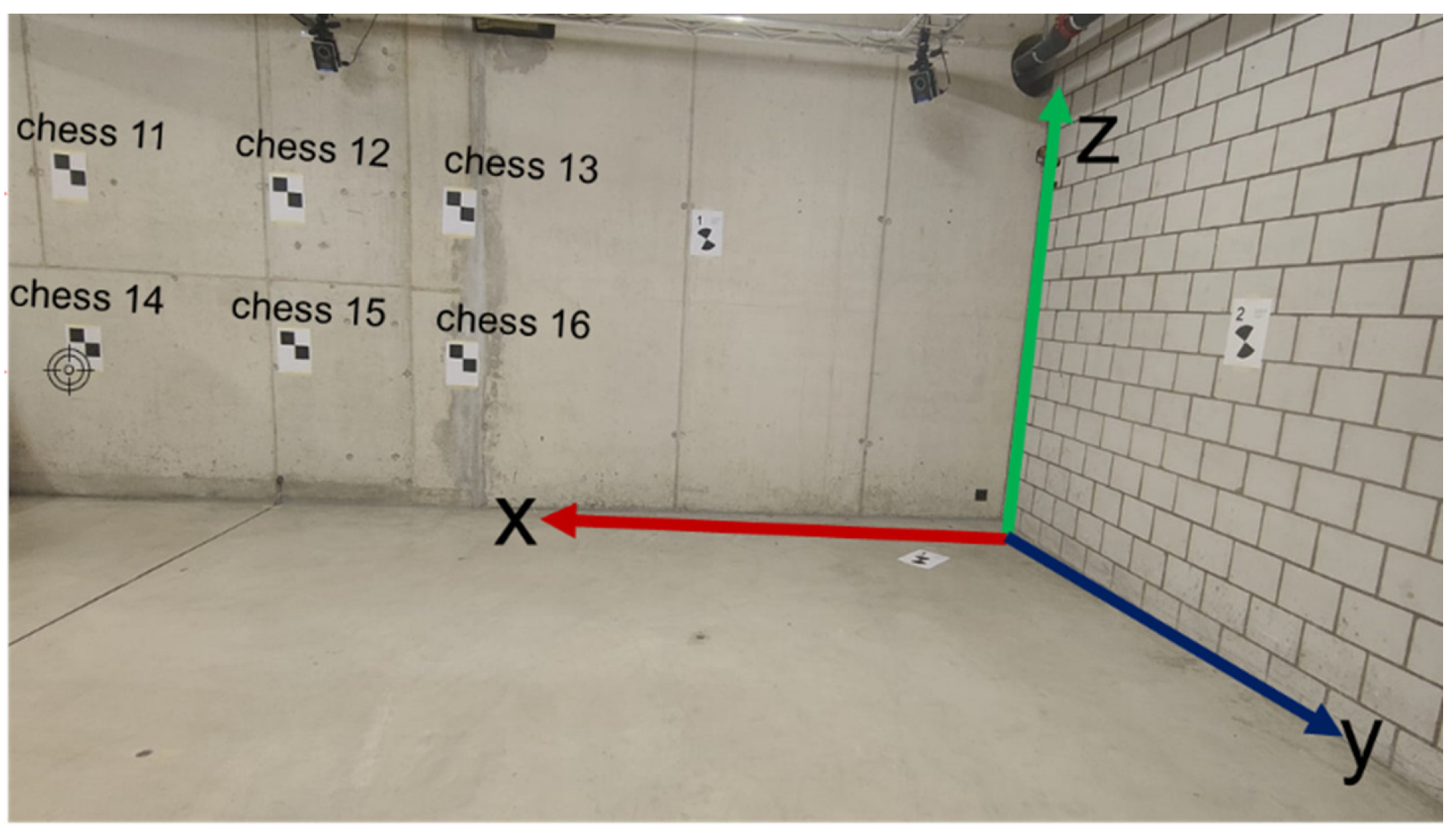

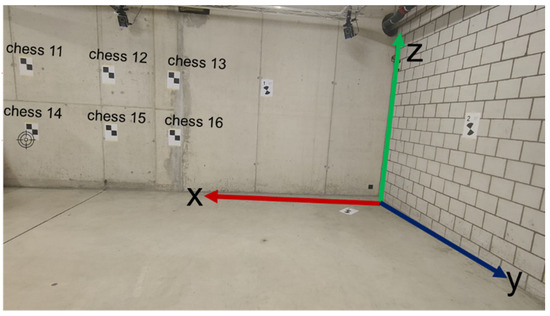

The AP20-MSP was tested both indoors and outdoors, while the GS18 I-MSP was only tested outdoors since the GS18 I loses satellite reception inside. For indoor live testing of AP20-MSP, the measurement laboratory of the Institute Geomatics, University of Applied Sciences and Arts Northwestern Switzerland was used; see Figure 8. The indoor experiments were designed to evaluate MSP performance in a GNSS-denied setting. Here, the AP20-MSP relied on fused pose estimates from the MS60 (position), AP20 IMU (orientation), and Blaze ToF camera (depth) for continuous 6-DoF tracking.

Figure 8.

The targets used in the Measurement Laboratory and the frame of reference used for the measurements.

For each run, the Blaze camera recorded depth and intensity frames at 20 Hz, while the AP20 logged IMU data at 200 Hz. The same extrinsic calibration described in Section 3.5 was applied. The relative distances between measured points were then computed directly in LV95 coordinates, without the need for GNSS referencing or frame transformation. Although the indoor test network is spatially smaller and contains fewer uniquely identifiable targets compared to the outdoor test field, it provides a controlled validation of drift behaviour, time synchronization, and short-range geometric consistency under full GNSS outage.

For outside testing, one of the houses situated at Arlesheim, Switzerland was used as shown in Figure 9. The front part of the house faces the road, while the rear part is shaded by tall trees in the backyard. The site was selected to represent real-world surveying conditions. It includes points that are easy to access and others that are either outside the direct line of sight of the totalstation, located in areas with low GNSS reception or multipath, and points which are visible but physically inaccessible to the surveyor. It was also essential to assess whether the spatial extent of the survey area could be expanded using the MSP configurations while maintaining sufficient GNSS signal quality and totalstation line of sight.

Figure 9.

The outdoor test area: the front side of the house (a) and the backside (b).

4. Results

In this section, two types of accuracy measures are reported. “Relative distances” refer to the Euclidean distances between pairs of surveyed points. This metric evaluates the internal geometric consistency of the measurements and is independent of the national or global reference frame. In contrast, “absolute distances” refer to the coordinate differences between MSP-derived point positions and the reference coordinates in LV95. This second metric reflects the absolute positioning accuracy of the system with respect to the Swiss reference frame.

Live single point measurement was tested using the AP20-MSP in a lab environment (Figure 8), with six checkerboard targets attached to the wall. The Leica MS60 MultiStation provided reference measurements. Despite reasonable accuracy and precision at shorter distances (150–350 cm), the experiment revealed a time-synchronization issue between the pose integration and point clouds. Since the pointcloud itself is not timestamped with the corresponding pose of the AP20 it is not possible to match the exact pose with the corresponding pointcloud in the live setup. This mismatch has greater influence at larger distances. This issue prevented reliable live single point measurements, particularly at longer distances in the live setup. The results showed an increase in absolute error from 8 cm at 1.5 m distance to 30 cm at 9.5 m, following a near-linear trend, whereas the relative error remained within 3 cm for all measurements. This synchronization issue did not affect the outdoor tests, as timestamps were precisely matched during post-processing.

For outdoor testing with both setups, three targets were fixed on tripods at three different locations around the house: one at the front, one in the middle and one at the back courtyard of the house (Figure 9). The whole area was scanned with the 3D laser scanner (RTC360) from Leica Geosystems AG. The RTC360 can capture up to 2 million points per second with a 3D accuracy of 2.9 mm at 20 m Distance. Therefore the scan obtained from the RTC360, shown in Figure 10, was used as a reference point cloud to compare the measurements later.

Figure 10.

The point cloud (3D scan) of the house taken by Leica RTC360.

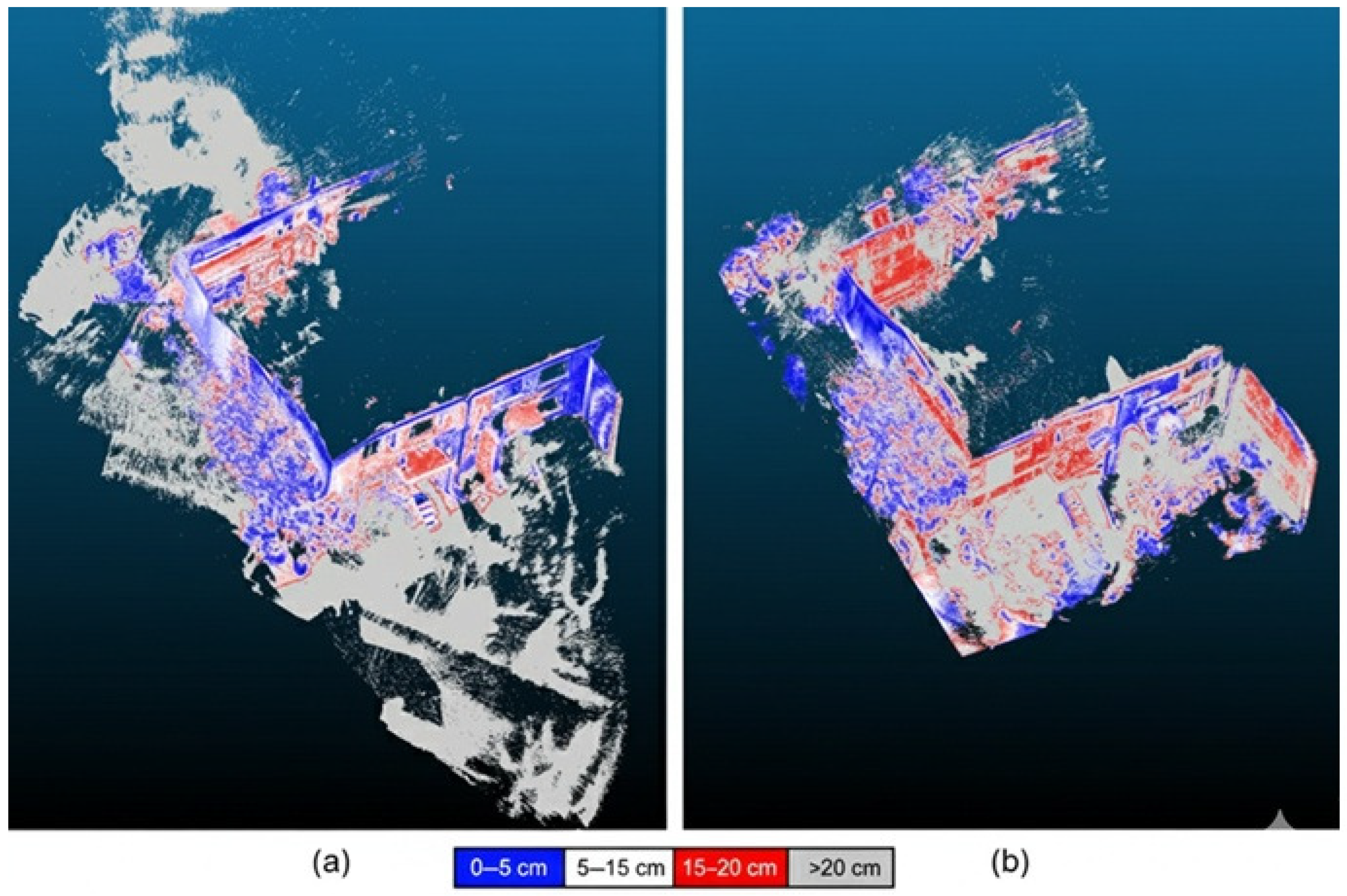

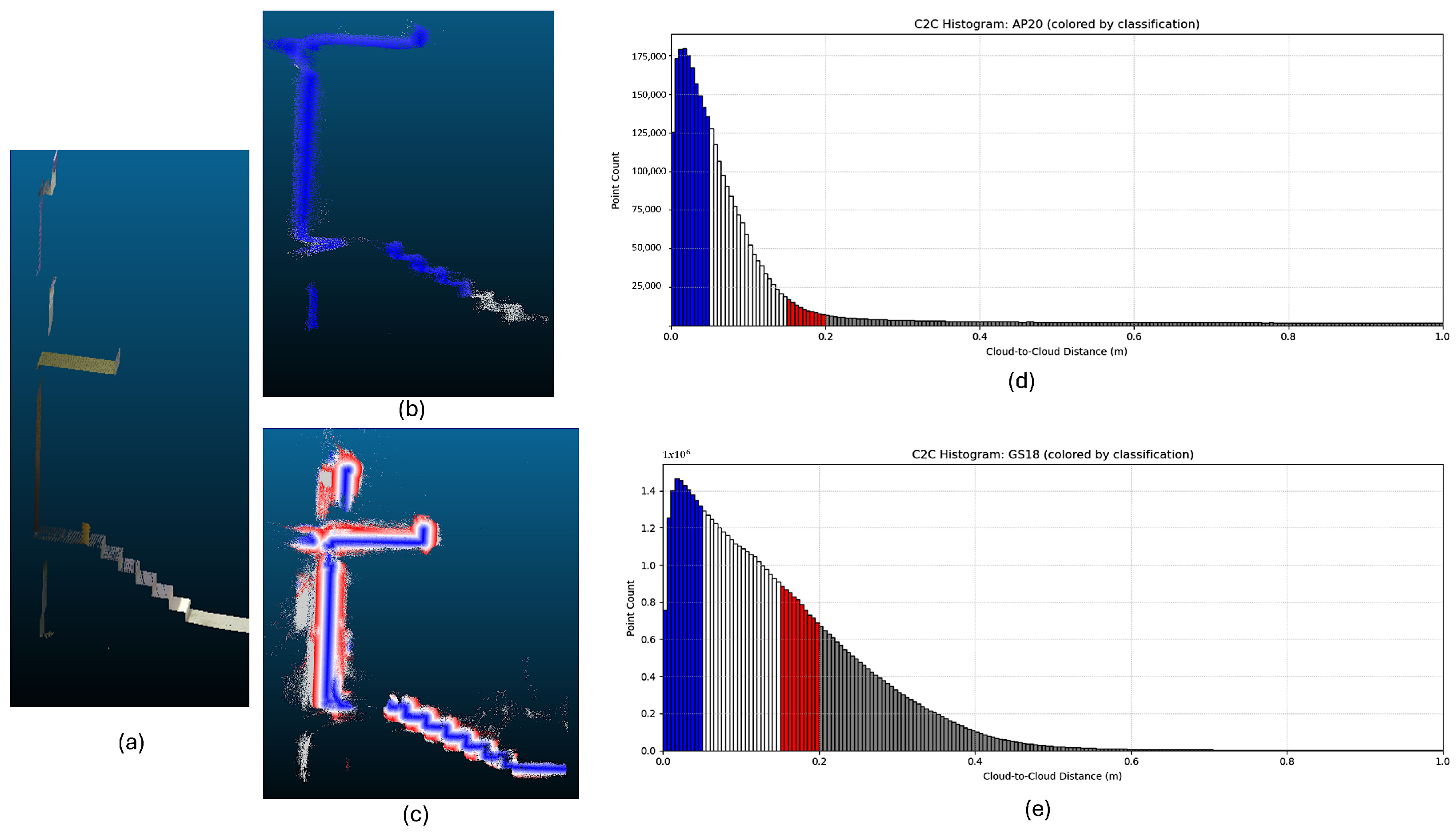

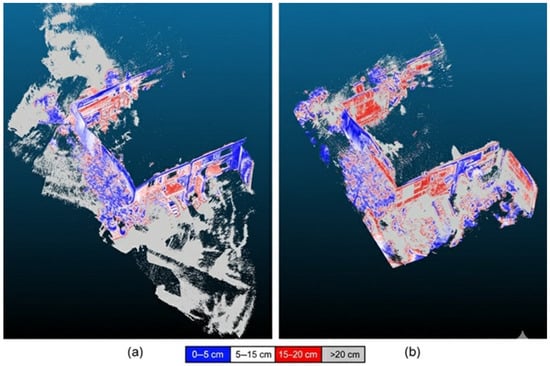

The corresponding synchronized point cloud taken by the AP20-MSP with a blue-white-red gradient scale is shown in Figure 11a and the point cloud taken from the GS18 I-MSP is shown in Figure 11b. The blue-white-red gradient when applied to a point cloud typically represents a visual encoding of distance or scalar field values when compared to another cloud. For example, in Figure 11, the blue points are in or near the reference RTC360 cloud (e.g., 0 cm). Points that are approximately 10 cm from the reference cloud are coloured white, while points coloured red are at or near 20 cm from the reference point. Then the points away from 20 cm are shown in grey. Note that the point cloud from the GS18 I-MSP is quite grey, which means that these points are more than 20 cm away from the reference cloud. The different patches blend worse than the ones from the AP20. This is probably a consequence of the varying accuracy of the poses this has greater influence the farther the points are from the MSP.

Figure 11.

The point cloud captured by the AP20-MSP (a) and with the GS18 I-MSP (b) with a gradient blue-white-red scale [0–20 cm] with reference to RTC360 cloud. The AP20-MSP shows tighter clustering (mostly blue), while GS18 I-MSP exhibits widespread grey points indicating >20 cm errors.

With each MSP, multiple sets of data were recorded around the house. Three sets of measurements were taken with the AP20-MSP while nine sets were taken with the GS18 I-MSP with the following reference points:

- Measured with Leica MS60: Points labelled as hp1, hp2, and hp3 were measured using the Leica MS60. The setup point of MS60 was calculated with a resection using three LFP3 points in the region and one HFP3 for height (LFP3 and HFP3 are official survey points in Switzerland that are managed by the municipality or a contractor of the municipality). The standard deviation for easting and northing was 1.2 cm.

- Natural Points: Seven natural features: b1 (building corner), b2 (balcony corner), b3 (railing corner), w1-3 (window corners), and e1 (entrance) were extracted from the RTC360 reference point cloud and geo-referenced using laser scanning targets mounted on tripods. Point b3 was identified in the RTC360 cloud and measured by the GS18 I-MSP, but it was not recoverable in the AP20-MSP point cloud, likely due to occlusion behind the railing and motion-induced dropout during acquisition. A height offset of 6.5 cm exists from the round prism to the laser scanning target. The geo-referencing process had a final RMS of 1.2 cm.

- Measured with GS18: Points labelled hp10, hp11, and hp12 were measured with the GS18 I on a different day due to technical difficulties, necessitating a second measurement campaign. To align this one with the other measurements, the laser-scanning targets were removed and the points were measured with the GS18 I. While the physical location of hp10–hp12 remained consistent across all measurements (both laser scanning and GS18), the necessary swap from large spherical laser targets to smaller total station reflectors introduced a known, measured vertical offset between the reference centers, which was later corrected. The 3D-Accuracy was below 5 cm for all measurements.

The accuracy expectations for the Multi-Sensor-Pole configurations vary based on the reference points and measurement methods. For the AP20-MSP, measurements taken with the MS60 are expected to have an accuracy combining the AP20’s inherent accuracy with a 1.2 cm standard deviation, with measurements closely matching the totalstation positions. The Reference Cloud 1 calculations for AP20 follow a similar pattern.

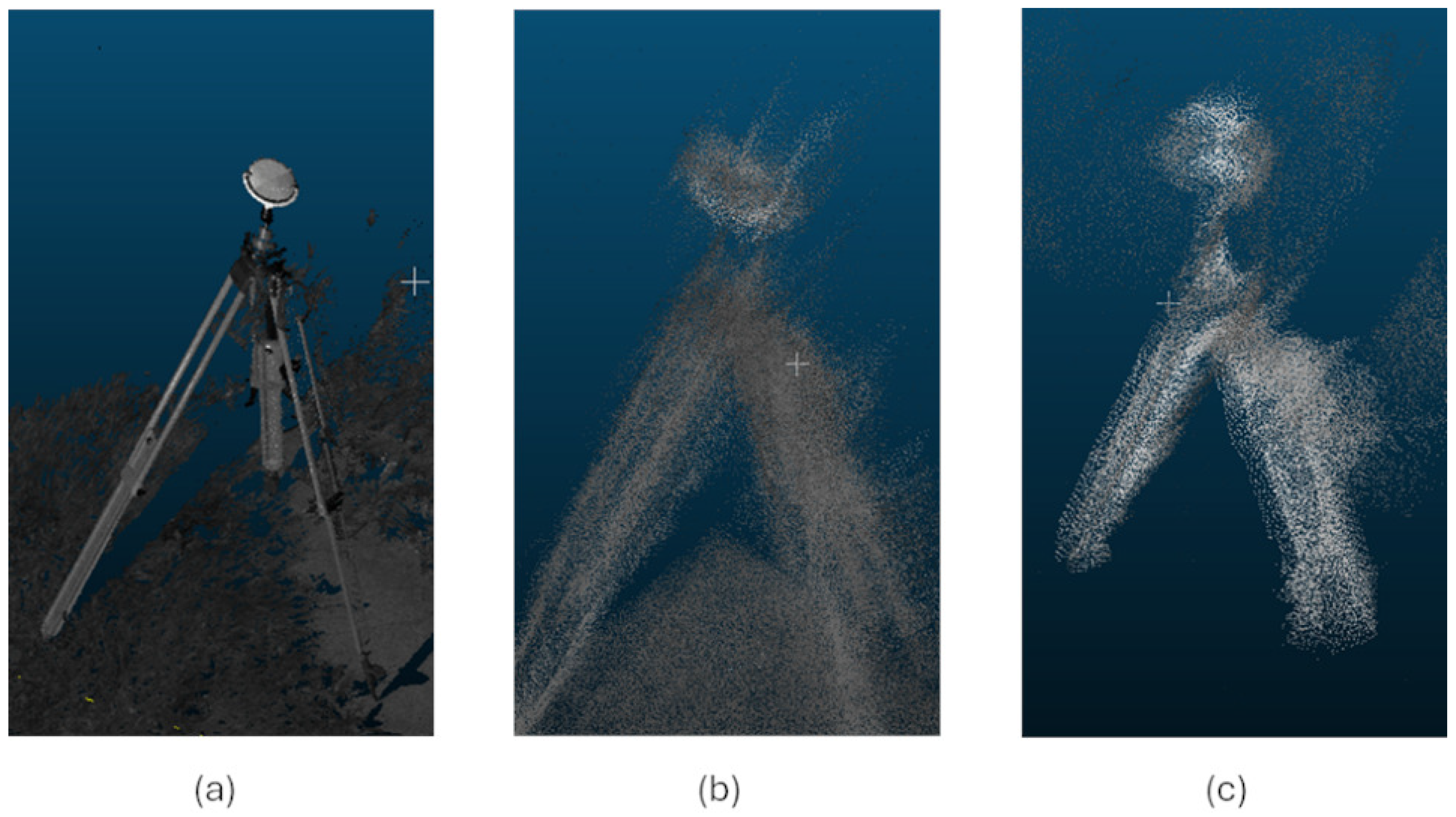

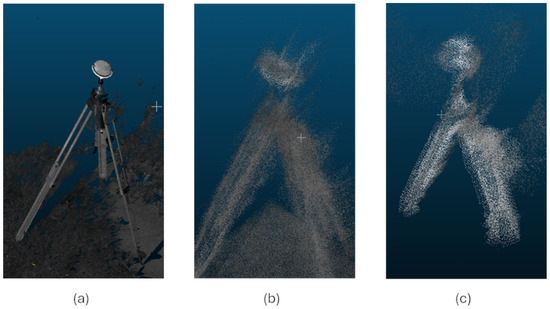

In fact, the measurements from the Blaze camera are noisier than those from the RTC360. It might also depend on how fast the Multi-Sensor-Pole was moving during the collection of the point clouds. However, synchronization with poses from GS18 I should be nearly perfect due to the matching of GS18 I images and intensity images from the Blaze camera. Likewise, the measurements of AP20 are nearly exactly a multiple of 10 of the Blaze Images (since the IMU rate of AP20 is 200 Hz and positioning updates were coming at 20 Hz measuring rate from the MS60). However, drag effects might have occurred when updating the 6-DOF pose. A comparison of a point cloud taken from RTC360, AP20-MSP, and GS18 I-MSP of a Laser scanning Target from the best sets is shown in Figure 12.

Figure 12.

Point cloud of a Laser scanning target taken by RTC360 (a), AP20-MSP (b), and GS18 I-MSP (c).

From the best datasets, some measurements were taken for comparison. The GeoCom command used in the GS18 I-MSP gave the measurement coordinates in the ECEF (Earth-Centred, Earth-Fixed) reference system. Then the transformation from the global GNSS reference frame to the Swiss national system was performed in three steps. First, by using the GeoCom command, the GS18 I outputs the rover position in the Earth-Centered Earth-Fixed (ECEF) frame. These coordinates are converted to the geodetic WGS84 system using the standard ellipsoidal parameters = 6,378,137.0 m and via the library of the Python (v 3.13.0) programming language. The resulting latitude, longitude, and ellipsoidal height are then projected into the Swiss projected coordinate system LV95 (EPSG:2056) using the official CH1903+ formulation. LV95 is the official Swiss coordinate reference frame for national surveying. The projection applies the grid shift model FINELTRA, ensuring consistency with Swiss federal geodetic standards. The FINELTRA transformation model is reliable to within 2 mm across the entire country. All point clouds and distance measurements are therefore referenced in LV95, which enables direct comparison against surveying-grade ground-truth points measured by the MS60 totalstation. Among these measurements, the relative and absolute distances from both MSP setups have been calculated and shown in Section 4.1 and Section 4.2. The relative distances are the distances calculated inside the point clouds, while the differences to the geo-referenced coordinates have been calculated as absolute distances.

4.1. Relative Euclidean Distances

The differences in relative distances within the point clouds for the AP20-MSP are minimal as shown in Table 2. Here, “relative” refers only to distances between points, not to the coordinate origin. For example, the distance between reference points hp1 and hp3 is only off by 1.21 cm, and the largest deviation observed is −17.3 cm (hp1–b1). The standard deviation for all the relative distances is 8.7 cm. This suggests that the AP20-MSP maintains good internal consistency and accuracy relative to the reference measurements. The relatively consistent and small errors across different point pairs also suggest good precision.

Table 2.

Relative Euclidean distances with the AP20-MSP taken inside the point clouds. The MS60 was setup at point hp2.

The GS18 I-MSP showed larger deviations in relative distances, with some differences exceeding 20 cm (see Table 3). The largest observed deviation was 62.0 cm for w2–w3. The standard deviation for all of them is 21.7 cm. This suggests that the internal consistency of the GS18 I-MSP measurements is less reliable compared to the AP20-MSP.

Table 3.

Relative Euclidean distances measured in the case of GS18 I-MSP.

4.2. Absolute Distances

For AP20-MSP, when comparing absolute distances, hp1 showed a 3D error of 2.69 cm and w3 had a more substantial error of 20 cm. However, the absolute errors for the AP20-MSP are within 3 cm for signalized points, such as hp1 and hp3, indicating that accuracy on the decimetre level is achievable (Table 4). Because the absolute errors we report in Table 4 and Table 5 are 17–33 cm, the contribution of the frame transformation is at least one order of magnitude smaller and can safely be neglected in the present discussion.

Table 4.

AP20-MSP absolute measurements compared to MS60 Reference Points.

Table 5.

Absolute measurement accuracy in the GS18 I-MSP.

With the GS18 I-MSP, the absolute distance errors were notably larger: b1 had a 3D error of 32.5 cm, while hp13, which is significantly better, still had a error of 17.5 cm (see Table 5).

While points b1–b2/b3, e and w1–w3 provide initial insight into natural-point (texture-based) measurement performance, their small number (n = 6 or 7) limits statistical generalizability. The observed degradation in GS18 I-MSP accuracy on these targets is therefore considered indicative of potential challenges in texture-poor or unstructured environments. Future work will expand validation across a broader set of natural features (e.g., walls, poles, vegetation) to quantify repeatability and bias.

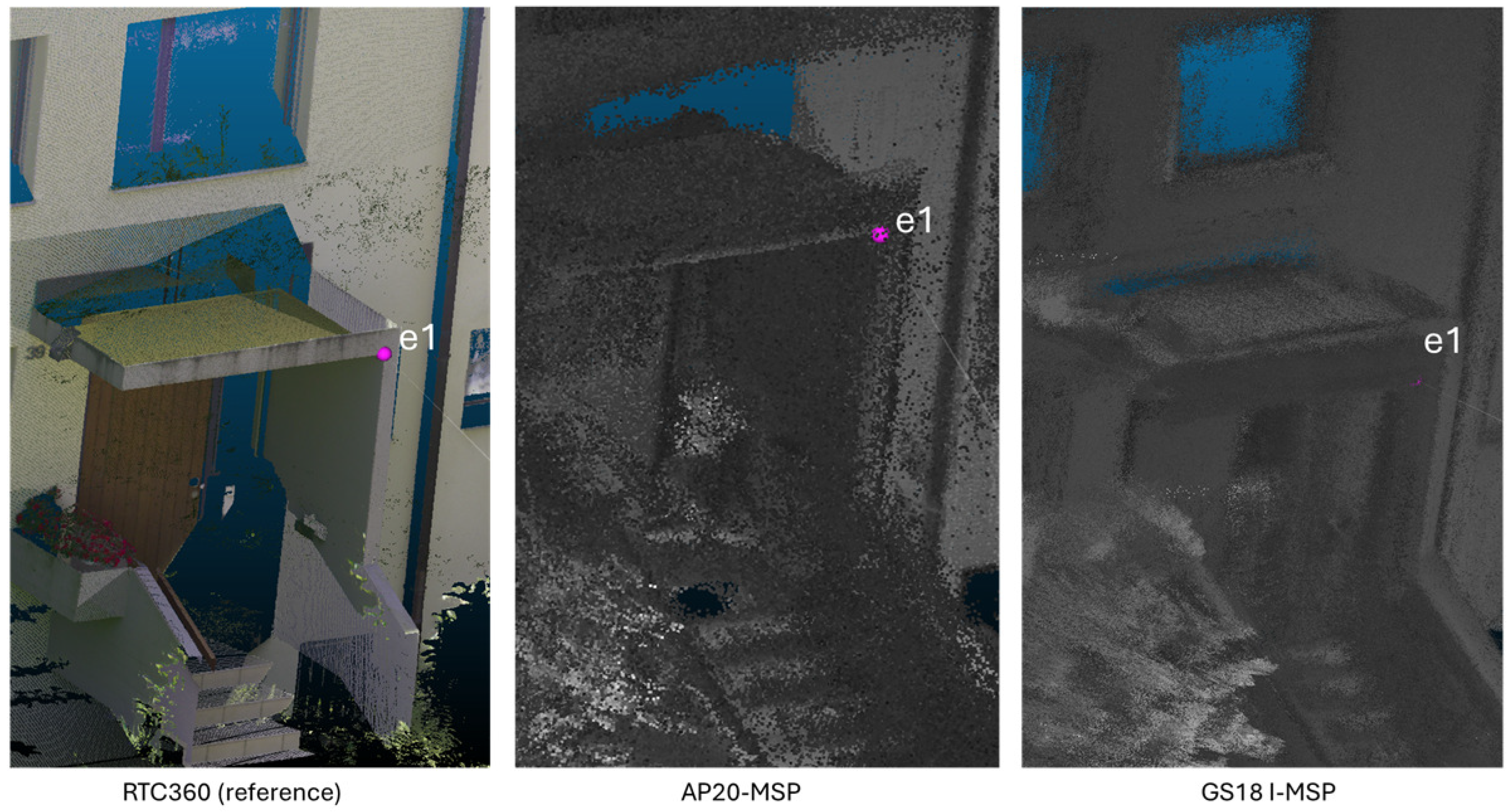

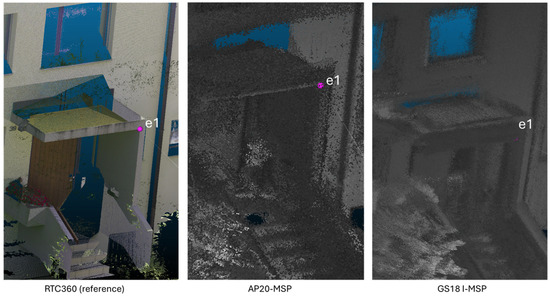

To illustrate the spatial manifestation of the observed absolute errors reported in Table 4 and Table 5, Figure 13 presents a close-up view of point e1 (front entrance) as reconstructed by the three systems. While e1 is selected for its large error magnitude (48.9 cm for GS18 I-MSP) and challenging geometry, similar patterns of misalignment are observed across all seven natural points tested (b1, b2, b3, w1, w2, e1, w3). In each case, the AP20-MSP point cloud aligns closely with the RTC360 reference. In contrast, the GS18 I-MSP point cloud exhibits increasing deviation, particularly along the vertical surfaces and under partial GNSS visibility. This confirms that the pose drift is a systemic issue rather than an isolated anomaly in the GS18 I-MSP.

Figure 13.

Point e1 (front entrance) as captured by RTC360 reference scan, AP20-MSP, and GS18 I-MSP. The pink dot indicates the true position of e1 derived from the RTC360 point cloud. The AP20-MSP point cloud shows tight clustering around the true location, with minimal deviation (<6 cm). The GS18 I-MSP point cloud exhibits significant geometric distortion and misalignment (>48 cm error), particularly along the vertical plane of the entrance structure.

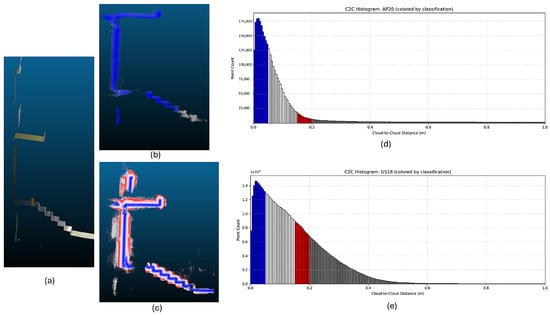

4.3. Quantitative Results

As seen in Figure 14, the cloud to cloud distance with a reference cloud was computed. If certain elements are looked at individually like the stairs in the front of the building, it is possible to see how much the points scatter. For the GS18 I-MSP the points scatter by up to 30 cm from the wall. If we look at the classes from Figure 14, 20% of points are within 5 cm 60% within 15 and 70% within 20 cm of the reference cloud. For the AP20-MSP 45% are within 5 cm, 70% within 10 cm and 80% within 20 cm.

Figure 14.

Point clouds of the stairs taken by RTC360 (a), AP20-MSP (b), and GS18 I-MSP (c). The histograms of the AP20-MSP pointcloud (d) and of the GS18 I-MSP pointcloud (e) are also shown. Histograms (d,e) are coloured by classification: blue = good alignment, red = moderate misalignment, gray = severe misalignment/outliers.

Although the Multi-Sensor-Pole used in this conceptual study is not yet a ready-to-use device, the results clearly demonstrate that integrating a ToF camera with GNSS and IMU technologies in the system can enhance surveying capabilities, allowing measurements in low-light or hard-to-reach areas without direct contact or line of sight. The experiment was carried out in a mixed open–semi-obstructed residential area. While this is not as complex as steep slopes or dense forest, it still provides several conditions relevant for multi-sensor fusion: direct GNSS availability at the front of the house, tree-induced GNSS degradation in the backyard, and limited line-of-sight for totalstation tracking. These variations allowed the MSP setups to be tested under changing visibility, lighting, and satellite geometry.

The results show that accuracy is most sensitive to how the sensor moves around corners, how much the line of sight is interrupted, and how quickly the pole is rotated between measurement patches. Because both MSP configurations rely on pose estimation during motion, any environment that forces frequent heading changes or rapid movement will amplify synchronization errors. In contrast, open areas with slow motion tend to produce more stable results. However, all this points can be improved with more sophisticated processing algorithms and filters.

The distribution of test points also plays a clear role. Points located behind obstacles or in weak GNSS regions show larger deviations, while points in open areas match the reference geometry more closely. This behaviour is consistent with how depth sensors and GNSS-INS systems respond to partial occlusion and pose uncertainty. Although additional test sites would strengthen the generality of the results, the patterns observed here reflect conditions typical of many practical surveying tasks.

The MSP could also improve stake-out operations by offering precise visual guidance, potentially with augmented reality features to overlay digital information, reducing errors and saving time—though such implementations were not tested here and would require dedicated usability studies. While not empirically validated in this study, the system’s ability to capture synchronized 3D and pose data opens avenues for applications in Building Information Modelling, infrastructure inspection, and topographic mapping. In summary, the key benefits of using a Multi-Sensor-Pole include:

- Improved low-light performance for night-time or indoor surveying.

- Enhanced accuracy, minimizing the need for multiple setups.

- Expand the application range of the existing systems.

- Simultaneous capture of positional and visual data for greater efficiency.

- Versatility across diverse surveying and mapping applications.

4.4. Optimization Strategies for the GS18 I-MSP

The lower accuracy observed in the GS18 I-MSP configuration indicates that several elements of the pipeline can be improved. For instance, currently the trigger from the GS18 I is activated via a GeoCom command. This command creates a small timing delay (10–20 ms of “jitter” because the software has to process the request before the hardware starts sending pulses. These small timing offsets between the GS18 I INS pulses and the Blaze frames lead to incorrect pose assignment during motion. A refined clock synchronization method, such as recording PPS-level timing could reduce this drift.

Besides, in the current setup, the calibration between the GS18 I camera, the Blaze ToF camera, and the GS18 I body frame is performed in separate steps. First, the intrinsic and extrinsic parameters of each camera are estimated, and then the transformations between the devices are solved. This step-by-step approach works when the sensors are static or moving slowly, but it introduces small alignment errors when the pole is in motion. These small errors later show up as inconsistencies in the reconstructed point cloud, especially in the GS18 I-MSP configuration where the pose relies heavily on INS propagation. A joint spatio-temporal optimization would estimate all calibration parameters together, which is the standard approach in multi-sensor robotics [39]. Instead of treating timing and geometry separately, this method fits the extrinsic transformations and the time offset between sensors in one combined optimization problem. This type of calibration approach is standard in advanced multi-sensor robotics setups and would directly benefit the GS18 I-MSP.

Similarly, the GS18 I relies heavily on continuous GNSS updates. During brief blockages, the INS carries the pose, which amplifies drift and affects the fused depth. Fused depth refers to the depth values generated after combining camera measurements with the INS prediction and the GNSS updates. When the pose estimate drifts, these depth values inherit the same error. To correct motion errors, one needs frame-to-frame changes. Integrating a short visual odometry step or a lightweight IMU prediction filter could help reduce this drift between GNSS fixes. This integration would use the Blaze intensity images, which are already time-synchronized through the hardware trigger. By tracking frame-to-frame feature motion (for example using ORB (Oriented FAST and Rotated BRIEF), which is a fast computer vision feature-tracking method or optical flow), the system can estimate short-term relative motion during intervals where the GNSS signal is weak or lost. This relative motion is then fused with the INS prediction to produce a corrected pose for each Blaze frame.

Note that this study was designed as a pilot evaluation of hardware-level ToF integration feasibility under real-world surveying conditions—not a full statistical validation. As such, several limitations must be acknowledged:

First, the outdoor test site, while representative of mixed GNSS visibility (open front vs. obstructed rear), covers only one building. While point cloud consistency across repeated GS18 I-MSP sessions (n = 9) and AP20-MSP sessions (n = 3) improves confidence in relative trends, broader environmental diversity (e.g., urban canyon, forest, indoor) remains untested.

Second, while the analysis of natural (non-signalized) points counts seven targets (b1, b2, b3, w1, w2, e1, w3), the sample size remains limited for robust generalization across diverse surface types and geometries (e.g., glass, metal, trees or curved walls). Absolute 3D errors range from 5.2 cm to 20.0 cm for AP20-MSP and 16.1 cm to 69.4 cm for GS18 I-MSP, with a mean of 10.7 cm and 33.9 cm, respectively. These results indicate a consistent performance gap particularly in occluded or GNSS-degraded zones (e.g., e1, w3), but should still be interpreted as indicative rather than definitive for population-level inference. Future work will validate these trends across a broader set of unstructured features.

Third, indoor testing (Section 3.7) validated synchronization and short-range drift behaviour but did not include quantitative accuracy assessment on natural indoor surfaces. This gap needs to be addressed in future indoor validation campaigns.

Notwithstanding these limitations, the large and consistent performance gap between AP20-MSP and GS18 I-MSP on survey-grade signalized points (hp1, hp2, hp3, hp10–hp13; n = 6)—supported by sub-3 cm vs. >17 cm 3D errors—strongly suggests a fundamental difference in system-level integration robustness, warranting the optimization pathways discussed earlier in this Section.

5. Conclusions

This study presented a comparative evaluation of two Multi-Sensor-Pole (MSP) configurations—AP20-MSP (total station–IMU–ToF) and GS18 I-MSP (GNSS-INS–ToF) under identical hardware, calibration, and processing conditions. The AP20-MSP achieves absolute accuracy, with 2.7–2.9 cm 3D error on MS60-controlled signalized points (hp1, hp3) and 5.2–20.0 cm on six natural features (b1, b2, w1, w2, e1, w3), all validated against a ≤1.2 cm RMS RTC360 reference cloud. Its relative consistency is high, with inter-point distance deviations ranging from 1.2 cm to 15.2 cm, and ≤1.2 cm for baselines >20 m (e.g., hp1–hp3; Table 2). In contrast, the GS18 I-MSP configuration exhibits significant absolute bias, with 17.5–26.6 cm 3D error on its four GNSS-measured signalized points (hp10–hp13) and 16.1–69.4 cm on seven natural targets (b1–b3, w1–w3, e1). While relative consistency remains acceptable over short spans (e.g., ≤2.2 cm on hp11–hp13), errors exceed 21 cm over longer distances or near texture-poor surfaces (hp12–w1), and surge dramatically in semi-occluded zones (e1: 48.9 cm; w3: 69.4 cm). This suggests that pose drift is the dominant error source, likely due to spatio-temporal misalignment in the GNSS-INS–ToF fusion chain (Section 4.4).

Critically, absolute accuracy matters more than relative consistency for most surveying workflows (e.g., stakeout, cadastral updates, BIM alignment), where points must tie into national or project grids. The AP20-MSP meets this requirement; the GS18 I-MSP does not yet.

With regard to efficiency, the AP20-MSP proves to be more effective for various surveying use cases, particularly in challenging environments. It is well suited for applications that require precise measurements, such as construction surveys, topographic mapping, and infrastructure monitoring. The GS18 I-MSP, while functional for low-accuracy tasks, requires further optimization, particularly in hardware-level synchronization and joint spatio-temporal calibration, before deployment in survey-grade workflows.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.B. and D.E.G.; methodology, J.B. and A.Q.; software, A.Q.; validation, J.B.; formal analysis, J.B.; investigation, A.Q. and J.B.; data curation, A.Q. and J.B.; writing—original draft preparation, A.Q.; writing—review and editing, D.E.G.; supervision, D.E.G.; project administration, A.Q. and D.E.G.; funding acquisition, D.E.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Leica Geosystems AG (Heerbrugg, Switzerland).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Leica Geosystems AG. The funder provided hardware, engineering support, and had no influence on the data analysis, interpretation, or conclusions.

Data Availability Statement

A curated point cloud dataset in CloudCompare BIN format, containing the reference MS60 point cloud and the AP20-MSP and GS18 I-MSP point clouds (including cloud-to-cloud deviation scalar fields), is available at Figshare (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30676172).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. Leica Geosystems AG reviewed the final manuscript for technical accuracy (e.g., product specifications) prior to submission, as is customary in industry-academic collaborations. The decision to submit for publication was made solely by the academic authors.

References

- Angelino, C.V.; Baraniello, V.R.; Cicala, L. UAV position and attitude estimation using IMU, GNSS and camera. In Proceedings of the 2012 15th International Conference on Information Fusion, FUSION 2012, Singapore, 9–12 July 2012; pp. 735–742. [Google Scholar]

- Inertial Navigation System. Page Version ID: 1232418048. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Inertial_navigation_system&oldid=1232418048 (accessed on 18 July 2024).

- Boguspayev, N.; Akhmedov, D.; Raskaliyev, A.; Kim, A.; Sukhenko, A. A comprehensive review of GNSS/INS integration techniques for land and air vehicle applications. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 4819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsayed, H.; Shaker, A. From Stationary to Mobile: Unleashing the Full Potential of Terrestrial LiDAR through Sensor Integration. Can. J. Remote Sens. 2023, 49, 2285778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Li, H.; Zhang, T. Camera, LiDAR, and IMU Based Multi-Sensor Fusion SLAM: A Survey. Tsinghua Sci. Technol. 2024, 29, 415–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Nie, W.; Zong, W.; Xu, T.; Li, M.; Jiang, N.; Zhang, W. High-Precision Multi-Source Fusion Navigation Solutions for Complex and Dynamic Urban Environments. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, T.; Guo, N.; Backén, S.; Akos, D. Monocular Camera/IMU/GNSS Integration for Ground Vehicle Navigation in Challenging GNSS Environments. Sensors 2012, 12, 3162–3185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grejner-Brzezinska, D.A.; Toth, C.K.; Moore, T.; Raquet, J.F.; Miller, M.M.; Kealy, A. Multisensor Navigation Systems: A Remedy for GNSS Vulnerabilities? Proc. IEEE 2016, 104, 1339–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Zhang, H.; Gao, Z.; Niu, X.; El-sheimy, N. Tight Fusion of a Monocular Camera, MEMS-IMU, and Single-Frequency Multi-GNSS RTK for Precise Navigation in GNSS-Challenged Environments. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trimble Incorporation. Trimble MX7|Mobile Mapping Systems. Available online: https://geospatial.trimble.com/products/hardware/trimble-mx7 (accessed on 22 July 2024).

- RIEGL. RIEGL—Produktdetail. Available online: http://www.riegl.com/nc/products/terrestrial-scanning/produktdetail/product/scanner/48/ (accessed on 22 July 2024).

- vigram AG. viDoc: GNSS Multi-Measurement Tool. Available online: https://vidoc.com/en/vidoc/vidoc-functionality/ (accessed on 22 July 2024).

- Redcatch GmbH. RTK GNSS for Your Smartphone. Available online: https://www.redcatch.at/smartphonertk/#specs (accessed on 22 July 2024).

- DJI Enterprise. Phantom 4 RTK. Available online: https://enterprise.dji.com/phantom-4-rtk (accessed on 22 July 2024).

- Cera, V.; Campi, M. Evaluating the potential of imaging rover for automatic point cloud generation. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2017, XLII-2/W3, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiocchi, V.; Piccaro, C.; Allegra, M.; Giammarresi, V.; Vatore, F. Imaging rover technology: Characteristics, possibilities and possible improvements. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2018, 1110, 012008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leica Geosystems AG. GS18 I—Leica Geosystems Surveying. Available online: https://pure-surveying.com/smart-antennas/gs18-i/ (accessed on 18 July 2024).

- Hi-Target Surveying Instrument Co., Ltd. Land Survey—New Pocket-Sized vRTK Is the Perfect Combination of GNSS, Advanced IMU, and Dual Cameras. Available online: https://en.hi-target.com.cn/land-survey-new-pocket-sized-vrtk/ (accessed on 22 July 2024).

- SOUTH Mapping Technology Co., Ltd. INSIGHT V1. Available online: https://www.southinstrument.com/product/details/pro_tid/3/id/118.html (accessed on 22 July 2024).

- CHC Navigation. CHCNAV Unveils RS10: A Revolutionary Integrated Handheld SLAM Laser Scanner with GNSS RTK System. Available online: https://chcnav.com/about-us/news-detail/chcnav-unveils-rs10:-a-revolutionary-integrated-handheld-slam-laser-scanner-with-gnss-rtk-system (accessed on 22 July 2024).

- Casella, V.; Franzini, M.; Manzino, A. GNSS and photogrammetry by the same tool: A first evaluation of the leica gs18i receiver. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2021, XLIII-B2-2021, 709–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paunescu, C.; Potsiou, C.; Cioaca, A.; Apostolopoulos, K.; Nache, F. The Impact of Geodesy on Sustainable Development Goal 11. In Proceedings of the FIG Working Week 2021: Smart Surveyors for Land and Water Management, Virtual, 21–25 June 2021; Available online: https://www.fig.net/resources/proceedings/fig_proceedings/fig2021/papers/ts07.2/TS07.2_paunescu_potsiou_et_al_11137_abs.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Lobo, T. Understanding Structure from Motion Algorithms. Available online: https://medium.com/@loboateresa/understanding-structure-from-motion-algorithms-fc034875fd0c (accessed on 26 July 2024).

- Survey, G. The Next Evolution: Introducing the New Leica AP20 AutoPole! Available online: https://globalsurvey.co.nz/surveying-gis-news/the-next-evolution-introducing-the-new-leica-ap20-autopole/ (accessed on 26 July 2024).

- Faro, M. Advantages of Using Total Stations over GNSS in Surveying|LinkedIn. Available online: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/advantages-using-total-stations-over-gnss-surveying-mossgeospatial/ (accessed on 26 July 2024).

- Kumar, P. What Is a ToF Sensor? What Are the Key Components of a ToF Camera? Available online: https://www.e-consystems.com/blog/camera/technology/what-is-a-time-of-flight-sensor-what-are-the-key-components-of-a-time-of-flight-camera/ (accessed on 26 July 2024).

- FRAMOS. What Are Depth-Sensing Cameras and How Do They Work? Available online: https://www.framos.com/en/articles/what-are-depth-sensing-cameras-and-how-do-they-work (accessed on 26 July 2024).

- Basler AG. Basler ToF Camera Blaze-101. Available online: https://www.baslerweb.com/en/shop/blaze-101/ (accessed on 26 July 2024).

- Huai, J.; Shao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yilmaz, A. A Low-Cost Portable Lidar-based Mobile Mapping System on an Android Smartphone. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2506.15983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teunissen, P.J.G.; Khodabandeh, A. Review and principles of PPP-RTK methods. J. Geod. 2015, 89, 217–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Studemann, G.L. Higher Resolution Camera for an Imaging Rover and Low-Cost GNSS Setup for Water Equivalent of Snow Cover Determination. Master’s Thesis, FHNW, Muttenz, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- ROS/Tutorials/UnderstandingNodes—ROS Wiki. Available online: https://wiki.ros.org/ROS/Tutorials/UnderstandingNodes (accessed on 7 August 2024).

- Blaze-102|Basler AG. Available online: https://www.baslerweb.com/en/shop/blaze-102/ (accessed on 13 August 2024).

- Bags—ROS Wiki. Available online: https://wiki.ros.org/Bags (accessed on 7 August 2024).

- Leica Geosystems. TPS-1200 GeoCOM Reference Manual, Version 1.20; Leica Geosystems: Heerbrugg, Switzerland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- ethz-asl/kalibr. Available online: https://github.com/ethz-asl/kalibr (accessed on 7 August 2024).

- Maye, J.; Furgale, P.; Siegwart, R. Self-supervised calibration for robotic systems. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV), Gold Coast, QLD, Australia, 23–26 June 2013; pp. 473–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furgale, P.; Rehder, J.; Siegwart, R. Unified temporal and spatial calibration for multi-sensor systems. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Tokyo, Japan, 3–7 November 2013; pp. 1280–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehder, J.; Nikolic, J.; Schneider, T.; Hinzmann, T.; Siegwart, R. Extending kalibr: Calibrating the extrinsics of multiple IMUs and of individual axes. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Stockholm, Sweden, 16–21 May 2016; pp. 4304–4311. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).