Abstract

The calibration of levelling staff is a key prerequisite for achieving high-precision levelling. Traditionally, this process is carried out using laser interferometric systems, which provide the required accuracy but are demanding in terms of operation, maintenance, and measurement conditions. This paper focuses on verifying the applicability of the convergent photogrammetry method for levelling staff calibration with a target accuracy of 0.010 mm. An experimental prototype of a photogrammetric calibration system (without real scale) was developed and tested using three different lenses, two processing software packages (Photomodeler and Agisoft Metashape), and two different approaches to camera calibration (self-calibration and field calibration). The repeatability of measurements was evaluated based on mutual lengths between selected checkpoints and the accuracy of determining the 3D positions of these points. The results showed that the Nikon AF-S NIKKOR 35 mm f/1.8G ED lens achieved the best repeatability and met the target accuracy requirement, while Photomodeler yielded smaller standard deviations in the determination of control point positions compared to Agisoft Metashape. The findings indicate that convergent photogrammetry, when applied under optimal conditions, has the potential to achieve the accuracy required for high-precision measurements in metrology, and may even offer an alternative to laser interferometric calibration systems in certain applications.

1. Introduction

The calibration of geodetic instruments and measuring devices is one of the fundamental procedures for achieving precise geodetic measurements. The same applies to a levelling set—comprising a levelling instrument and a levelling staff—intended for accurate height difference measurements and subsequent determination of elevations. There are many calibration systems and techniques for levelling sets. The basic division is whether the entire levelling system is calibrated or only the levelling staff separately. Another classification of calibration systems is based on the position of the levelling staff—it can be placed in a horizontal or vertical orientation—and on the measurement methodology used. Most calibration systems involve laser interferometry as the scale standard, while some use linear encoders. A more detailed classification of calibration systems for levelling sets is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Division of the calibration systems for levelling sets [1].

As a rule of thumb, in any calibration the standard should achieve an accuracy at least one order of magnitude higher than that of the instrument being calibrated. In the case of coded levelling staff, this means determining the position of the graduation lines on the staff with an accuracy of at least 0.010 mm.

In this paper, we focus on the separate calibration of levelling staff. In levelling, the levelling staff serves as the scale standard, and therefore its metric quality has a direct influence on the resulting measurement accuracy. There are many calibration systems designed specifically for the separate calibration of levelling staffs; however, there is no standardized manual or serial production of such devices. As a result, they are mostly found in research institutions and universities, each as a unique type. Examples of such devices include calibration systems at Wrocław University [2], the University of Zagreb [1], the Slovak University of Technology in Bratislava [3], or the Czech Technical University in Prague [4]. Most of these systems use for calibration a length standard determined by laser interferometry. This method meets the high accuracy requirements for levelling staff calibration. In addition to laser interferometry, further auxiliary systems are included—such as reading the position of graduation lines (photogrammetry), mechanical displacement of the staff or displacement of a reflector prism, etc. In such systems, image processing only appears as secondary to laser interferometry. In recent years, attempts have also been made to create a calibration system for levelling staff based primarily on the photogrammetric method, involving close-range photogrammetry techniques. However, these attempts failed due to insufficient accuracy of the chosen photogrammetric method [5]. In the past few years, however, close-range photogrammetry methods have advanced significantly, and many measurements using photogrammetric techniques now achieve an accuracy level comparable to that required for levelling staff calibration.

Close-range photogrammetry is one of the most universal measurement techniques for reconstructing objects ranging in size from a few millimeters to hundreds of meters. Close-range photogrammetric methods are not scale defined, and the final reconstruction accuracy can be controlled by transforming the model into a reference system or by adding a scale. Well-known close-range photogrammetry methods include single-image (projective) photogrammetry, stereophotogrammetry, convergent photogrammetry, panoramic photogrammetry, and photogrammetric scanning [6]. The most accurate of these is convergent photogrammetry, which benefits particularly from image axes in a general (convergent) orientation, automated processing of digital images, and the simple generation of redundant measurements by adding more images. Under special conditions and with precise processing, convergent photogrammetry can achieve high relative object reconstruction accuracy up to 1:250,000 or even 1:500,000 [7,8]. Such high precision is enabling its application in precise civil engineering, industrial, and metrological fields, e.g., for structure deformation monitoring [9,10,11], inspection and quality control [12], crack and deviations detection [13], automatization, calibration of measuring systems [5], etc. The procedure for applying automated convergent photogrammetry includes stabilizing coded targets, stabilizing control points (resp. checkpoints) or scale bars on the object being imaged, followed by image acquisition and image processing—automated measurement of coded target centers and bundle block adjustment [14]. This determines the elements of interior and exterior orientation of the images, along with their accuracy characteristics, which is considered an evaluation of the precision of the photogrammetric model. The entire photogrammetric model is then transformed into a reference system based on control points or scaled using added scale bars. By comparing the coordinates of checkpoints, or the lengths of check scale bars from the photogrammetric model with known values in the reference system, the accuracy of the photogrammetric model is determined.

Our objective is to develop a calibration system for levelling staff based specifically on the method of convergent photogrammetry. As mentioned earlier, achieving high accuracy requires ensuring suitable conditions, the description of which will be the focus of this paper. We assume that the resulting calibration system should be able to calibrate levelling staffs faster, more easily, and more efficiently than laser interferometric calibration systems (whose disadvantages lie in their difficult operation, sensitivity to environmental conditions, demanding maintenance, and above all, high cost), while maintaining their high calibration accuracy.

2. Materials and Methods

The aim of this paper is to verify the accuracy of the convergent photogrammetry method. As mentioned earlier, the accuracy of convergent photogrammetry is not fixed, and its upper limit is constrained by several factors—the accuracy of scale determination, the quality of the images, and the quality of image processing. The target accuracy of the calibration system under development was determined to be 0.010 mm based on available sources [15] and by comparing the achievable accuracy of laser interferometric calibration systems. In this paper, we focus primarily on image quality and image processing quality. Image quality is controlled by ensuring appropriate technical parameters during image acquisition, which will be discussed in detail in the following chapters. The quality of processing is assessed by comparing several image series captured with identical exposure parameters and subsequently processed. At this stage, the scale is introduced into the photogrammetric system only as an approximate value to reality, and it is always entered as the same distance between two identical points within each image series. By comparing the processing results of individual image series, we obtain information on the repeatability of the measurement, and thus a characteristic of the image processing quality. Ensuring high-quality image acquisition and processing is a fundamental prerequisite for completing the photogrammetric system for metrological purposes.

2.1. Convergent Photogrammetry

Convergent photogrammetry uses multiple images of an object taken from different angles so that the camera axes converge on the observed object. This method of capturing enables the creation of a 3D model of the object with high reconstruction accuracy, as each point on the object’s surface is recorded from multiple perspectives. The main principle of convergent photogrammetry is the collinearity principle (perspective transformation), which states that a point on the object, the projection center, and the same point projected onto the image plane all lie on a single straight line. This principle is mathematically expressed using the collinearity equations [14]:

where , are the image coordinates; , are the coordinates of the principal point; is the principal distance; , , are the reference object coordinates; , , are the reference coordinates of the projection center; and – are the elements of the orthogonal rotation matrix. The collinearity equations describe the mutual relationship between the interior and exterior orientation parameters of the camera based on the measured image coordinates on the photos and the reference coordinates of the same point in space. If we have enough observations, we can enhance the collinearity equations by including the elements of radial and decentering lens distortion. There are several lens distortion models, and each photogrammetric software may use its own correction model. An example of a geometric lens distortion model is the Brown–Conrady model [16]. The resulting corrections are incorporated into the collinearity equations:

where , are the corrected image coordinates of the point after accounting for distortion effects; , are the corrections due to radial distortion; and , are the corrections due to decentering distortion.

Radial distortion arises due to the position of points away from the optical axis in the object space. It is radially symmetric around the principal point of the image and must be corrected:

where , , are the coefficients of the radial distortion and is the radial distance of point with image coordinates , .

Decentering (tangential) distortion is caused by imperfect alignment of the curvature centers of the lens elements with the optical axis. It is usually several times smaller than radial distortion, and its parameters are estimated during precise photogrammetric work:

where , are the parameters of decentering distortion. By estimating the parameters of radial and decentering distortion alongside focal length and the coordinates of principal point, we perform a calibration of the photogrammetric system. In special cases, it is worth considering extending the geometric distortion model of the lens to include affinity and sensor skew elements.

With a larger number of observations—measured coded targets or naturally defined points in the image—we obtain many possible collinearities equation sets and solve them simultaneously using bundle block adjustment with the least squares method. To achieve optimal results and robust determination of the interior and exterior orientation parameters of the camera, it is important that the point field contains enough points evenly distributed across the surveyed object [17,18]. In addition to camera calibration, achieving maximum accuracy in convergent photogrammetry requires ensuring several other technical components, such as a suitable sensor (camera) with a lens, coded targets with quality lighting, an appropriate imaging configuration (object distance, number of images, network geometry, intersection angle, suitability for camera calibration, coordinate system and scale definition, verification of orientation parameters), and measurement processing [8].

2.2. Measured Object

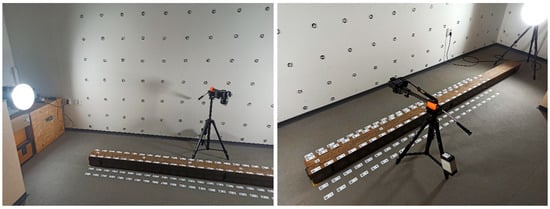

The imaged object is adapted to determine the dimensions of levelling staff. It is important to note that this is currently a prototype developed for the purpose of testing the accuracy of the convergent photogrammetry method. All properties of this prototype calibration system were iteratively tested under various settings to achieve optimal results. The object consists of a wooden base approximately 3.00 m in length (only 2.40 m was used for the prototype) and about 0.20 m in height. This wooden base simulates the object on which levelling staff would be placed. On each side of the object, there is sufficient space for attaching coded targets, installing lighting, and handling the camera tripod (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Showcase of the prototype photogrammetric calibration system.

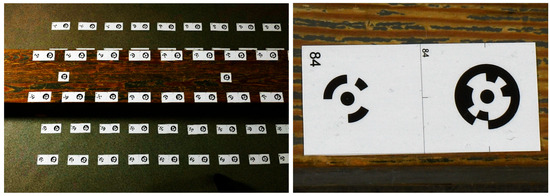

2.3. Coded Targets

Coded targets are essential for the automated measurement of tie points and for the subsequent calculation of the elements of interior and exterior camera orientation in specialized photogrammetric software [19,20]. Each software package may use a different type of coded targets and has its own algorithm for their detection and measurement. From a practical perspective, circular coded targets are most often chosen in close-range photogrammetry, and their measurement is typically performed using a centroid operator, an edge operator, or center measurement via the least squares method (template matching). These operators for measuring circular targets can achieve image coordinate determination accuracy in the image plane on the order of 0.01–0.05 pixels [14]. For processing our image set, we selected two software packages—one that uses RAD (ringed automatically detected) coded targets and another that uses 12-bit coded targets (resp. 8-bit, 16-bit, etc.). For this reason, the targets were placed on the imaged object in organized pairs, each consisting of both types of coded targets (Figure 2). The coded targets must not change their position, must be of high print quality, and their size is also important. Both selected programs use template-matching operators for point measurement, for which it is characteristic that the target size should not be smaller than 15 pixels [14]. For our project, the diameter of the circular targets was chosen as 4 mm which corresponds to 30–40 pixels in the images, depending on the object distance and focal length used. The coded targets were printed with high quality on a matte, non-glossy, and firm self-adhesive film. They were attached to the imaged object in a square grid of approximately 0.10 × 0.10 m. This ensured that each image contained enough coded targets evenly distributed across the entire image area, which is a key prerequisite for robust camera calibration.

Figure 2.

Organized pairs of coded targets (12-bit and RAD).

2.4. Illumination

Illumination directly affects the image processing and result generation, making it one of the most important components of photogrammetric imaging. Insufficient illumination can reduce the accuracy of coordinate measurements in the image plane, thereby decreasing the accuracy of the relative orientation of images [21]. Lack of light can be compensated by using a flash, camera-mounted lights, or external illumination. Proper illumination of the imaged object depends on the specific situation, taking into account the spectral properties of the light source, the spatial position of the light source, atmospheric conditions, the spectral properties of the surface material, the structure of the imaged surface, the position and orientation of the surface, the optical and radiometric properties of the camera, and the position and orientation of the camera [14]. In general, it is best if the imaged object is uniformly illuminated with constant light, without any shadows or reflections on the object. The space selected for the experiment is part of the Laboratory for Spatial Modelling of Objects and Phenomena, located inside the basement of the Faculty of Civil Engineering at STU Bratislava. For this reason, we decided to use two Fomei Easy Light 3 studio lights positioned on the sides of the photogrammetric system, set up to uniformly illuminate the entire imaged object without creating unwanted shadows or reflections (Figure 1).

2.5. Camera and Lens Selection, Imagery

An important factor when selecting the camera and lens is the required geometric resolution of the images. Geometric resolution in object space (GSD—ground sampling distance) is a function of the sensor (camera) used, the focal length of the lens, and the object distance from which the image was taken. By combining geometric resolution with the accuracy of measuring image coordinates, we obtain a simplified relation for the a priori accuracy of convergent photogrammetry under optimal conditions [6].

where is the accuracy of measuring image coordinates, is the object distance, is the focal length of the lens used, and is the pixel size on the sensor. For our experiment, we chose the Nikon D850 camera with a full-frame sensor format, with a pixel size of 4.36 µm and an image resolution of 8256 × 5504 pixels (Figure 3). We selected lenses to ensure a suitable compromise between geometric resolution, which increases with increasing focal length, and the field of view, which decreases with increasing focal length. Three available lenses were tested (Figure 3)—Nikon AF-S NIKKOR 35 mm f/1.8 G ED (Nikkor 35 mm G), Nikon AF NIKKOR 20 mm f/2.8 D (Nikkor 20 mm D), and Nikon AF-S NIKKOR 20 mm f/1.8 G ED (Nikkor 20 mm G); all lenses were manufactured by Nikon Corporation (Tokyo, Japan). According to the focal length of the lens used, the object distance was adjusted to ensure that the coded targets were evenly distributed across the image (approximately 1.0 m for the 35 mm lens and 0.6 m for the 20 mm lens). The theoretical GSD values for the defined object distances were calculated according to Equation (5), considering the height difference between the ground and the wooden base. The GSD measured at the top of the wooden base is reported as the minimum value, while the GSD measured on the ground represents the maximum value (Table 2). The lens aperture was always set to the highest possible value, ensuring the best depth of field for the images. The sensor ISO sensitivity was set to 100, considering the artificial lighting and tripod used. The exposure time was determined based on the described exposure parameters to ensure the image was sufficiently illuminated. The exposure parameters are described in more detail in Table 2.

Figure 3.

Lenses and camera used (from left: Nikkor 35 mm G, Nikkor 20 mm D, Nikkor 20 mm G, and Nikon D850).

Table 2.

Exposition parameters for used lenses.

The imaging was performed using a specially modified tripod for nadir photography, aiming to minimize the influence of unwanted camera movements during shooting (Figure 1). The imaging was performed in four passes above the object at the respective object distance, with additional images taken from multiple angles at both ends of the object. The baseline between neighboring images was approximately 0.10 m (increasing the density of intervals did not significantly affect the final accuracy), which determined the total number of images (92). A 2 s shutter delay was set to avoid mechanical vibrations caused by pressing the shutter button. Focusing was performed manually—the first image was focused, and no refocusing was performed between subsequent shots. By not refocusing between images, we ensured the most stable internal camera orientation parameters [18]. The images were recorded in .tiff format to avoid any data loss due to compression into other formats. For each tested lens, three such image sets were created and then processed in the selected processing software.

2.6. Image Processing

Image processing was carried out using two selected software programs—Agisoft Metashape 2.1.0 [22] and Photomodeler Premium 2020.1.1 [23]. The same sets of images from each series were input into both programs. The following subsections provide a description of the image processing for each software separately.

2.6.1. Photomodeler

Photomodeler is currently one of the leading software programs for image processing based on the convergent photogrammetry method. Photomodeler primarily works with RAD coded targets, which are specially designed for very precise subpixel measurement of the centers of coded targets. The image processing consisted of several steps [24]:

- Creating a project with automatic measurement of RAD coded targets, uploading images, and starting the automatic detection and measurement of RAD targets in the images (Edge Filter Sigma 2.0 pix; Edge Strength High Threshold 0.4; Edge Strength Low Threshold 0.2; Fit Error 0.1 pix);

- Determination of the exterior and interior orientation parameters of the camera based on bundle block adjustment using the least squares method;

- Exclusion of outlier measured points (Ignore a Border around the Image 8%) and optimization of the interior and exterior camera orientation parameters;

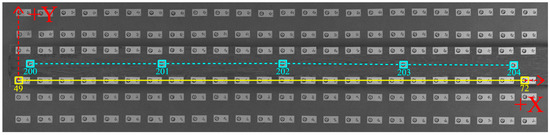

- Insertion of a constant scale between two selected RAD coded targets (numbers 49 and 72);

- Measurement of check lengths.

We filtered out points with high residual values and processed the individual image sets in two variants based on the camera calibration approach [24]:

- Self-calibration, in which the interior camera parameters are estimated by bundle block adjustment and optimized separately for each image;

- Field calibration (full-field), where the interior camera parameters are also estimated by bundle block adjustment but are optimized into a single set of camera parameters that is applied to all images (referred to as full-field calibration in Photomodeler).

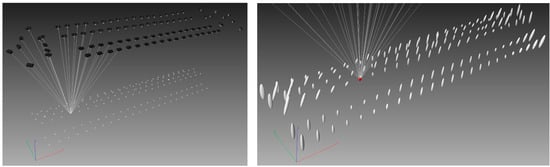

Photomodeler provides a summary of the bundle block adjustment, including information on the image coverage, the number of images per point, and the angles between rays. This summary is presented in Table 3, showing the average values from three image sets for the full-field version of the camera calibration. The results indicate that Nikkor 35 mm G exhibits smaller maximum and average point angles compared to 20 mm lenses, which is attributable to the longer object distance of the camera. In addition, camera stations, local coordinate system, rays, and detail with confidence intervals are shown in Figure 4.

Table 3.

Summary of bundle block adjustment results in Photomodeler.

Figure 4.

Camera stations, rays, and detail with confidence intervals from Photomodeler (for lens Nikkor 35 mm G, first set of imagery).

2.6.2. Agisoft Metashape

Agisoft Metashape software is primarily designed for digitizing objects based on photogrammetric scanning methods. Agisoft Metashape cannot detect RAD coded targets, so it was necessary to use the arranged pairs of targets described in Section 2.3. These facts had to be considered, and the entire image processing workflow was adapted accordingly to achieve the desired results [25]:

- Creating a project, loading images and automatic detection of 12-bit coded targets;

- Determination of the exterior and interior orientation parameters of the camera based on the SfM (Structure from Motion) algorithm, using bundle block adjustment with the least squares method, supplemented by automatically detected natural tie points (Precision: Highest; Key Points: 100,000; Tie Points: 0—all);

- Automatic detection and measurement of the centers of RAD targets as non-coded circular targets;

- Filtering outlier measured tie points and optimization of the interior and exterior camera orientation parameters (Image Count: 2; Reprojection Error: 0.05; Reprojection Uncertainty: 10.0; Projection Accuracy: 10.0);

- Insertion of a constant scale between two selected RAD coded targets (numbers 49 and 72);

- Measurement of check lengths.

Similarly to the processing in Photomodeler, the image sets were processed in Agisoft Metashape using multiple approaches based on the camera calibration method [25]:

- Self-calibration, where the sparse point cloud was filtered based on a reprojection error threshold, followed by optimization of the camera calibration results with the interior camera parameters estimated separately for each image;

- Field calibration (full-field calibration), in which the sparse point cloud was also filtered based on a reprojection error threshold, followed by optimization of the camera calibration results with a single set of interior camera parameters estimated for the entire image block.

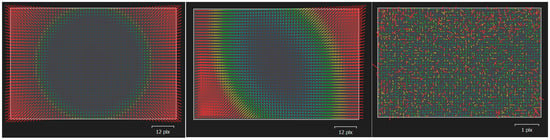

Agisoft Metashape software provides valuable visualization of the camera distortion computed during bundle block adjustment. Following visualization is represented in Figure 5, where the differences between radial, decentering, and residual distortion, as well as their magnitudes, can be observed.

Figure 5.

Distortion visualization from Agisoft Metashape for the Nikkor 35 mm G lens, first image set, using full-field calibration (from left: radial distortion, decentering, and residual distortion).

3. Results

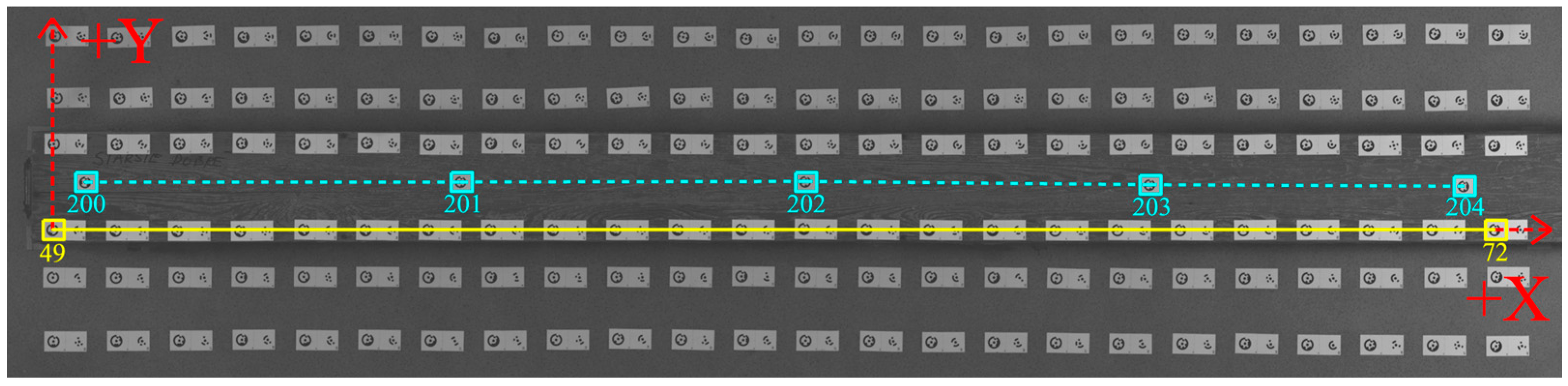

We compared the mutual lengths between five points (200 to 204) on the top of the wooden base (Figure 6). Since the same scale value was always applied to the same pair of points, we assume that differences between the image sets arise due to errors in image quality and their processing. From three image sets captured for each lens, we computed the mean value and standard deviation, as well as the maximum reprojection error and its RMS from the processing results. These values from both software programs are compiled into tables, sorted according to the lens and processing software used. We also distinguish between processing variants based on the camera calibration approach used. The first table contains measurements processed in Photomodeler (Table 4). Similarly, the second table compares check lengths in Agisoft Metashape (Table 5).

Figure 6.

Graphical representation of the inserted scale, checkpoints, check lengths, and local right-handed coordinate system.

Table 4.

Comparison of check lengths (Photomodeler).

Table 5.

Comparison of check lengths (Agisoft Metashape).

SD values, as well as the maximum and RMS residuals presented in the tables, indicate that the Nikkor 35 mm G lens achieved the best repeatability of image processing across both software packages and for both camera calibration approaches. This confirms that, among the tested lenses, it has the highest optical quality. In contrast, the Nikkor 20 mm D lens produced the poorest results, likely due to it being the oldest and most frequently used of the three lenses tested. The Nikkor 20 mm G lens produced results within the specified tolerance under full-field calibration, but its result under self-calibration were not sufficiently precise. The Nikkor 20 mm D lens performed even worse in self-calibration, which can be attributed to the instability of the interior orientation parameters of the 20 mm lenses. Overall, full-field calibration yielded more accurate results than self-calibration. When comparing the MEAN values between lenses, differences greater than 0.010 mm are evident—both between different lenses and within the same lenses processed by different software. Once again, these differences were the smallest for the Nikkor 35 mm G lens. This further highlights the importance of selecting a high-quality lens and appropriate processing software. The smallest deviations were observed in lengths located in the middle part of the object—lengths 201–202 and 202–203—where the camera network is expected to be most robust. In addition to the measured lengths between points, we also evaluated the accuracy of determining the 3D positions of points 200–204. The positional accuracy is characterized in both software programs by the standard deviations of point positions along the coordinate system axes. The local right-handed coordinate system orientation used is shown in Figure 6, with the Z-axis extending perpendicularly from the image plane towards the observer. Since the levelling staff represents a vertical (one-dimensional) standard, and the most critical aspect is determining the position of the coded tape segments along the vertical axis of the rod, we focus primarily on the standard deviation along the X-axis. The standard deviations, computed as average of three image sets of the same lens, are organized into tables. The first table contains standard deviations determined by Photomodeler (Table 6), and the second table contains standard deviations determined by Agisoft Metashape (Table 7).

Table 6.

Comparison of standard deviations of check points (Photomodeler).

Table 7.

Comparison of standard deviations of check points (Agisoft Metashape).

By comparing the standard deviation values, we gain insight into the accuracy of determining the 3D positions within each processing software. Photomodeler yields significantly lower standard deviation values compared to Agisoft Metashape, which is understandable since Photomodeler focuses on convergent photogrammetry, whereas Agisoft Metashape primarily targets photogrammetric scanning. Also, measurement of coded targets centers is much more precise than measurement of naturally signalized tie points. In both software packages, the standard deviations for the lenses used confirm the superior quality of the Nikkor 35 mm G lens. Similarly to the measured lengths, the lowest standard deviations are found at points located in the center of the wooden base (points 201, 202, and 203). From this, it follows that to achieve consistent measurement uncertainty across the entire calibration system, the point field will need to be extended on each side so that the edge points of the levelling staff appear in the same number of images as the central points. In the last table, we compiled the differences between calibration parameters (focal length and principal point) divided by camera calibration approach, lens used, and number of image set (Table 8). For self-calibration, due to the large number of images (92), the table presents the ranges of selected interior orientation parameters.

Table 8.

Comparison of camera calibration parameters (focal length and principal point).

Differences in the estimated camera interior orientation parameters between the processing software packages for the Nikkor 35 mm G lens are up to 0.0100 mm; for the Nikkor 20 mm G and Nikkor 20 mm D lenses, this value is up to 0.0400 mm. These changes can cause deviations between the measured check lengths. The differences arise from the differing photogrammetric method used in each software, as was mentioned before. This effect occurs especially during self-calibration. Differences in camera calibration parameters between image series, whether under self-calibration or full-field calibration, are the smallest for Nikkor 35 mm G, both within individual image series and comparing both software packages. Conversely, the differences increase for the Nikkor 20 mm G and are largest for the Nikkor 20 mm D. These results confirm our expectation of the superior optical quality of the Nikkor 35 mm G and the instability of the interior orientation parameters of both 20 mm lenses used.

4. Conclusions

This article verified the applicability and accuracy of the convergent photogrammetry method for calibrating levelling staffs. The experimental photogrammetric calibration system was tested using three different lenses and two processing software packages—Photomodeler and Agisoft Metashape. Also, two different approaches to camera calibration were tested—self-calibration and full-field calibration. The results clearly showed that the Nikkor 35 mm G lens achieved the best measurement repeatability and the lowest RMS deviations, meeting the target accuracy of 0.010 mm. The Nikkor 20 mm G lens delivered acceptable but slightly worse results. The Nikkor 20 mm D lens showed the lowest quality of measurements and did not meet the accuracy requirement. All lenses performed better under full-field calibration compared to self-calibration. The Photomodeler software achieved smaller standard deviations in determining the 3D position of points compared to Agisoft Metashape, which aligns with its primary focus on convergent photogrammetry.

These findings confirm that convergent photogrammetry, under optimal conditions (appropriate lens selection, controlled lighting, stable coded targets, and a robust processing workflow), can achieve the required accuracy for calibrating levelling staffs. Further research will focus on developing a fully functional calibration device—optimizing and automating the measurement procedure. Based on the experiment results, we will need to expand the point field to achieve consistent positional accuracy of the graduation lines along the entire length of the levelling staff. Equally important is the integration of a real scale, which we plan to implement by combining the convergent photogrammetry method with precisely determined points of a microscale network using a laser tracker.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.F. and O.B.; methodology, M.F.; validation, O.B.; formal analysis, M.F. and O.B.; investigation, O.B.; resources, O.B.; data curation, O.B.; writing—original draft preparation, O.B.; writing—review and editing, M.F. and O.B.; visualization, O.B.; supervision, M.F.; funding acquisition, M.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This publication was created with the support of the Scientific Grant Agency of the Ministry of Education, Science, Research, and Sport of the Slovak Republic and the Slovak Academy of Sciences under the project VEGA-1/0618/23, the Slovak Research and Development Agency under the project APVV-23-0447 and the STU Foundation for the Development of Talents—Slavoj Family Scholarship.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study is available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| RAD | Ringed automatically detected |

| GSD | Ground sampling distance |

| SfM | Structure from Motion |

| RMS | Root mean square |

| SD | Standard deviation |

References

- Baričević, S.; Staroveški, T.; Barković, Đ.; Zrinjski, M. Measuring Uncertainty Analysis of the New Leveling Staff Calibration System. Sensors 2023, 23, 6358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuchmister, J.; Gołuch, P.; Ćmielewski, K.; Rzepka, J.; Budzyń, G. A Functional-Precision Analysis of the Vertical Comparator for the Calibration of Geodetic Levelling Systems. Measurement 2020, 163, 107951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajánek, P.; Kopáčik, A.; Kyrinovič, P.; Erdélyi, J.; Marčiš, M.; Fraštia, M. Metrology of Short-Length Measurers—Development of a Comparator for the Calibration of Measurers Based on Image Processing and Interferometric Measurements. Sensors 2024, 24, 1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vyskočil, Z.; Lukeš, Z. Horizontal Comparator for the System Calibration of Digital Levels – Realization at the Faculty of Civil Engineering, CTU Prague and in the Laboratory of the Department of Survey and Mapping Malaysia (JUPEM) in Kuala Lumpur. Geoinform. FCE CTU 2015, 14, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giniotis, V.; Petroškevičius, P.; Skeivalas, J. Application of Photogrammetric Method for Height Measurement Instrumentation. Mechanika 2008, 14, 69–73. [Google Scholar]

- Fraštia, M. Vybrané Aplikácie Fotogrametrie v Oblasti Merania Posunov; Slovenská Technická Univerzita: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Maas, H.; Hampel, A. Photogrammetric Techniques in Civil Engineering, Material Testing and Structure Monitoring. Photogramm. Eng. Remote Sens. 2006, 72, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luhmann, T. Close Range Photogrammetry for Industrial Applications. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2010, 65, 558–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiteman, T.; Lichti, D.D.; Chandler, I. Measurement of Deflections in Concrete Beams by Close-Range Digital Photogrammetry. J. Surv. Eng. 2002, 9–12. [Google Scholar]

- Pavelka, K.; Zahradník, D.; Sedina, J.; Pavelka, K. New Measurement Methods for Structure Deformation and Objects Exact Dimension Determination. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing Ltd.: Bristol, UK, 2021; Volume 906, p. 012060. [Google Scholar]

- Albert, J.; Maas, H.-G.; Schade, A.; Schwarz, W. Pilot Studies on Photogrammetric Bridge Deformation Measurement. Photogramm. Rec. 2002, 21, 24. [Google Scholar]

- Bösemann, W. Industrial Photogrammetry: Challenges and Opportunities. Photogramm. Rec. 2011, 8085, 188–197. [Google Scholar]

- Niemeier, W.; Riedel, B.; Fraser, C.; Neuss, H.; Stratmann, R.; Ziem, E. New Digital Crack Monitoring System for Measuring and Documentation of Width of Cracks in Concrete Structures. J. Civ. Struct. Health Monit 2008, 12, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Luhmann, T.; Robson, S.; Kyle, S.; Boehm, J. Close-Range Photogrammetry and 3D Imaging, 2nd ed.; Whittles Publishing: Dunbeath, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, T.; Fischer, W. Manufacturing of High Precision Leveling Rods. In The Importance of Heights, Proceedings of the Symposium, Gävle, Sweden, 15–17 March 1999; Lilje, M., Ed.; FIG: Gävle, Sweden, 1999; pp. 223–228. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, D.C. Decentering Distortion of Lenses. Photogramm. Eng. 1966, 32, 444–462. [Google Scholar]

- Luhmann, T.; Fraser, C.; Maas, H.G. Sensor Modelling and Camera Calibration for Close-Range Photogrammetry. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2016, 115, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, C.S. Automatic Camera Calibration in Close Range Photogrammetry. Photogramm. Rec. 2013, 79, 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, C.S. Innovations in Automation for Vision Metrology Systems. Photogramm. Rec. 1997, 15, 901–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shortis, M.R.; Seager, J.W. A Practical Target Recognition System for Close Range Photogrammetry. Photogramm. Rec. 2014, 29, 337–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobkowska, K.; Burdziakowski, P.; Szulwic, J.; Zielinska-Dabkowska, K.M. Seven Different Lighting Conditions in Photogrammetric Studies of a 3D Urban Mock-Up. Energies 2021, 14, 8002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agisoft. Metashape 2.1.0; Agisoft LLC: St. Petersburg, Russia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Photomodeler. Premium 2020.1.1; Photomodeler Inc.: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Photomodeler. User Manual; Photomodeler Inc.: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Agisoft. Metashape User Manual—Standard Edition, Version 2.1; Agisoft LLC: St. Petersburg, Russia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).